DRAFTING FOR MULTIPLE EXECUTORS,

TRUSTEES, AND AGENTS

1

Presented and Written by:

MARK R. CALDWELL, Dallas

Caldwell, Bennett, Thomas, Toraason & Mead, PLLC

Co-author:

SARAH V. TORAASON, Dallas

Caldwell, Bennett, Thomas, Toraason & Mead, PLLC

State Bar of Texas

33

RD

ANNUAL

ESTATE PLANNING & PROBATE DRAFTING

October 26-27, 2022

Houston

CHAPTER 13

1

. This outline and any related presentation are for educational purposes only and are not intended to

establish an attorney-client relationship or provide legal advice. While some areas of the law are settled,

other remain unsettled. In certain areas, the authors have endeavored to identify differing positions or

arguments which may be taken or made with respect to specific unsettled legal issues.

Mark R. Caldwell

Shareholder

Mark R. Caldwell routinely represents executors, guardians, and beneficiaries in complex estate, trust, and

guardianship litigation. He has also represented fiduciaries in all phases of estate, trust, and guardianship

administration. Mark is passionate about holding those who exploit others accountable and defending those who have

been wrongfully accused of doing so. Mark enjoys the investigatory aspects of estate and trust litigation, including

reviewing and analyzing medical, financial, and suspicious property records and transactions. Mark is committed to

developing and maintaining strong, personal relationships with his clients. He endeavors to offer smart, pragmatic

and cost-effective legal advice. Mark believes that the strongest winning position is one that is simple, direct, and

understandable. While he strives to advocate strong, aggressive positions for clients, Mark also strives to resolve

disputes in an ethical, reasonable, and cost-effective manner.

Biography

Mark was born on June 29, 1979 at Beaufort Naval Hospital in Beaufort, South Carolina where his father flew F-4

Phantoms at the nearby Marine Corps air station (although his mother had the more difficult job of raising three

children). After having lived in South Carolina, North Carolina, Hawaii, and California, he returned to North Texas

and attended Eastfield Community College before transferring to Southern Methodist University, where he earned a

full academic scholarship. One year later, he attended the London School of Economics as a General Course Student.

Mark earned his law degree from New England School of Law in Boston, Massachusetts in 2005.

Mark is married and has three children. He enjoys spending time with his family, living an active life-style and

traveling.

Representative Experience

• Obtained favorable jury verdict for lack of testamentary capacity and undue influence in hotly contested will

contest and favorable jury verdict for lack of contractual capacity and breach of fiduciary duty in same

lawsuit regarding certain non-probate beneficiary designations.

• Recovered significant settlement in case involving fraud on the community and breach of fiduciary duty

through the use of a power of attorney.

• Obtained favorable jury verdict in a guardianship case involving an elderly ward.

• Successfully defeated claim that will was executed without testamentary capacity on summary judgment.

• Routinely obtains temporary injunctions and temporary guardianships to halt rogue agents from abusing their

powers of attorney.

• Obtained partial summary judgment against Trustee for breach of fiduciary duty involving the failure to

account.

• Represents guardians, executors, and administrators in all phases of guardianship and estate administration.

• Routinely serves as attorney ad litem and guardian ad litem in guardianship cases.

• Routinely serves as temporary guardian in contested guardianship cases and as temporary administrator and

administrator in decedents’ estates.

• Successfully obtained ancillary estate administration in California to collect and administer assets and claims

due and owing to Texas estate.

• Successfully transferred guardianships to and from California.

Public Speaking & Publications

• Co-Author/Panelist: Getting Back on Track – What to do When Best-Laid Estate Plans Get Derailed – 28

th

Annual Advanced Estate Planning Strategies Course (2022).

• Author/Speaker: Disclosure and the Fiduciary: How Much, How Far and to Whom? – 15

th

Annual

Fiduciary Litigation Seminar (2020).

• Author/Speaker: North Texas Probate Bench Bar: A Trustee’s Duty to Disclose: A Dangerous Trap or a

Useful Tool? (2020).

• Co-Author: You Settled it Right? Family Settlement Agreements in Probate, Trust and Guardianship

Disputes” – Texas Tech Estate Planning and Community Property Law Journal, 11 Est. Plan. & Community

Prop. L.J. 213 (Spring 2019).

• Co-Author/Speaker: State Bar of Texas: Changing IRA Beneficiary Designations After Death by Court

Order or Agreement – Intermediate Estate Planning and Probate (2019)

• Co-Author/Speaker: National College of Probate Judges: “A Road Increasingly Traveled: Multistate Probate

Issues” – (2019).

• Co-Author: “You Settled It, Right? Family Settlement Agreements in Probate, Trust and Guardianship

Disputes” – North Texas Probate Bench Bar (2019).

• Co-Author/Speaker: “Choosing Your Own Adventure and Navigating Self-Dealing Transactions Under the

New Power of Attorney Act” – 29th Annual Estate Planning & Probate Drafting (2018).

• Co-Author/Speaker: “A Road Increasingly Traveled: Multistate Probate Issues” – The Estate Planning, Trust

and Probate Law Section of the San Diego County Bar Association (2017).

• Co-Author: “Ensure Powers of Attorney Fulfill Intended Purposes” – Estate Planning, Thompson Reuters

Checkpoint, (January 2018).

• Co-Author: National College of Probate Judges: “Constitutional Considerations When Restricting Access to

the Proposed Ward in Contested Guardianship Proceedings” – Spring Journal (2017).

• Co-Author/Speaker: State Bar of Texas: State Bar of Texas: “Litigation Involving Powers of Attorney &

Bank Accounts” – Advanced Estate Planning & Probate (2017).

• Co-Author/Speaker: State Bar of Texas: “What’s New in Guardianship” – Advanced Guardianship Law

Course (2017).

• Co-Author/Speaker: State Bar of Texas: “The Shortest Route to Victory: Summary Judgment Practice in

Probate and Trust Litigation” – 40th Annual Advanced Estate Planning and Probate Course (2016).

• Co-Author/Speaker: Dallas County Bar Association, Probate, Trust and Estates Section: “Trends in

Litigating and Administering Guardianships” (2016).

• Author/Speaker: State Bar of Texas: “Injunctive Relief–The Lethal Preemptive Strike in Probate, Trust and

Guardianship Litigation” – 39th Annual Advanced Estate Planning and Probate Course (2015).

• Co-Author/Speaker: State Bar of Texas: “Elder Exploitation” – Advanced Guardianship Law (2015).

• Co-Author/Speaker: Travis County Bar Association: “Winning the Battle & the War: A Remedies–Centered

Approach to Litigation Involving Durable Powers of Attorney” (2015).

• Co-Author: “Properly Performing Annual Accounts in Guardianships and Management Trusts Where One or

Both Spouses are Incompetent” – Real Estate, Probate, & Trust Law Reporter, Volume 52, No. 4 (2014).

• Served as Moderator for the Guardianship and Ad litem Attorney Certification Course, sponsored by the

Dallas Bar Association Probate, Trusts & Estate Section, Dallas County Probate Courts and the Dallas

Volunteer Attorney Program to train lawyers in the representation of guardians of indigent wards, and the

role and responsibilities of the Attorney ad litem (2014).

• Co-Author: “Winning the Battle and the War; A Remedies—Centered Approach to Litigation Involving

Durable Powers of Attorney”– 64 Bay. L. Rev. 435 (Spring 2012).

• Author/Speaker: “An Introduction to Guardianships” – Texas Department of Assistive & Rehabilitative

Services (DARS), Dallas, Texas (Fall 2010; Spring 2011).

• Co-Author/Speaker: “Proof of Facts and Common Evidentiary Problems Encountered in Contested Probate

Proceedings,” at the Seventh Probate Litigation Seminar, sponsored by the Tarrant County Probate Bar

Association (September 2010).

• Author, A Good Deed Repaid: “Awarding Attorney’s Fees in Contested Guardianship Proceedings” – 51 S.

Tex. L. Rev. 439 (Winter 2009).

Community and Bar Association Involvement

• State Bar of Texas; Real Estate, Probate and Trust Law Section, Guardianship Committee; Member (2015-

2018)

• Dallas Bar Association; Probate and Trust Section Member; Trial Skills Section Member

• Dallas Bar Association; Probate and Trust Section; Council Member (2015-2016)

• Dallas Association of Young Lawyers; Elder Law Section Member

• Member, St. Thomas More Society

• Dallas Bar Mentor Program; Participated as Mentee; Mentor, Edward V. Smith III

• Board of Directors and Vice President, City of Sachse Economic Development Corporation (2010-2014)

• Member, Charter Review Commission, City of Sachse, Texas (2012-2013)

Certifications, Awards and Recognition

• Board Certified Estate Planning and Probate Law – Texas Board of Legal Specialization

• Named Texas Super Lawyer by Texas Super Lawyers, a Thompson Reuters Service (2020-2022)

• Named Rising Star by Texas Super Lawyers, a Thompson Reuters service (2014-2019)

• Selected Rising Stars Top 100 Up & Coming Attorneys in Texas, a Thompson Reuters service (2018-2019)

• Named Best Lawyers in Dallas, by D. Magazine (2018-2021)

Education

• General Course, The London School of Economics, London, England (2001-2002)

• B.A., magna cum laude, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas (2002)

• J.D., New England Law | Boston, Boston, Massachusetts (2005)

Sarah V. Toraason

Shareholder

An experienced litigation attorney, Sarah Toraason has ten years’ experience representing clients in complex

commercial disputes involving securities, contract, business tort, insurance coverage, ERISA, and intellectual

property claims in state and federal courts as well as arbitration. Sarah now applies her extensive business litigation

background to representing clients in estate, trust, and guardianship disputes. She strives to be a strong advocate for

her clients and approaches every matter with the goal of producing a successful and efficient resolution of their case.

Sarah graduated from the University of Richmond with a B.A. in Music and Leadership Studies and received her

M.B.A. and M.A. from the University of Cincinnati. She earned her J.D. from William & Mary School of Law. After

graduating from law school, Sarah served as a law clerk to the Honorable Henry Coke Morgan, Jr., of the United

States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. She then clerked for the Honorable Fortunato P. Benavides

of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in Austin, Texas.

Prior to entering the legal profession, Sarah studied music and worked in arts administration for the Honolulu

Symphony in Honolulu.

Sarah is admitted to practice in California (2003) and Texas (2004).

Representative Experience

• Obtained favorable jury verdict for lack of testamentary capacity and undue influence in hotly contested will

contest and favorable jury verdict for lack of contractual capacity and breach of fiduciary duty in same lawsuit

regarding certain non-probate beneficiary designations.

• Successfully defended former CFO of a national home-building company in a securities fraud class action in the

Southern District of Florida and on appeal to the Eleventh Circuit.

• Obtained denial of class certification on behalf of Fortune 500 media company and certain officers and directors

in a securities class action in the Northern District of Texas and on appeal to the Fifth Circuit.

• Represented for-profit educational institution in the Southern District of Texas and on appeal to the Fifth Circuit

in a suit seeking to enforce a confidentiality provision in an arbitration agreement. The Fifth Circuit upheld

award of preliminary and permanent injunction based on the confidentiality clause.

• Won dismissal of claims challenging design and administration of ERISA-governed severance plan and secured

award of costs in favor of defendants. Defended judgment on appeal to the Fifth Circuit.

• Defended CEO of oil and natural gas company in a series of ten shareholder and derivative suits filed in state and

federal court seeking to challenge potential acquisition of the company

• Defended oil and gas company in a hydraulic fracking case.

• Represented Fortune 500 company in a significant trademark suit.

• Represented large pharmaceutical manufacturer in putative nationwide antitrust class actions brought by direct

and indirect purchaser plaintiffs in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania.

• Obtained dismissal of claims brought against insurance company and former claims adjuster in Texas state court.

Publications & Public Speaking

• Co-presenter: “Jury Selection in Probate Disputes: Avoiding the Minefield and Winning the Case,” Clear Law

Institute National Webinar (September 2019).

• Co-author/Co-presenter: “A Road Increasingly Traveled: Multistate Probate Issues,” National College of Probate

Judges Spring Journal and Spring Conference (2019).

• Co-author: “Not Your Typical Voir Dire: Selecting a Jury in a Will Contest Case,” Dallas Bar Association,

Headnotes (December 2018 edition).

• Co-author/Co-presenter: “A Road Increasingly Traveled: Multistate Probate Issues,” Estate Planning, Trust and

Probate Law Section of the San Diego County Bar Association (June 7, 2018).

• Co-author: “Constitutional Considerations When Restricting Access to the Proposed Ward in Contested

Guardianship Proceedings,” National College of Probate Judges Spring Journal (2017).

• Co-author/Co-presenter: “Planning to Avoid Power of Attorney Litigation,” Texas Trust School (July 2017).

• Co-author/Co-presenter: “The Quick and Dirty E-Discovery Lowdown: An Introduction To What Should Be

Keeping You Up at Night,” Texas Bar CLE (June 2010).

• Co-author: “Student Liability Lawsuits: Suggested Best Practices to Avoid Class and Mass Actions and

Minimize Potential Exposure” (August 2010).

Education

• B.A., magna cum laude, University of Richmond, Richmond, Virginia (1996)

• M.B.A., University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio (1998)

• M.A., University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio (1998)

• J.D., Order of the Coif, William & Mary School of Law, Williamsburg, Virginia (2002)

Community and Bar Association Involvement

• Dallas Bar Association; Probate, Trust & Estates Section Member

• State Bar of Texas

• The William ‘Mac’ Taylor Inn of Court, Barrister

• Attorneys Serving the Community

• Assistant chancellor, Episcopal Diocese of Dallas

Drafting for Multiple Executors, Trustees, and Agents Chapter 13

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................... 1

II. CO-TRUSTEES ...................................................................................................................................................... 2

A. Section Overview ............................................................................................................................................ 2

1. Key Points ............................................................................................................................................... 2

2. Key Questions to Consider ...................................................................................................................... 2

B. Sources of Authority in Analyzing Co-Trustee Issues .................................................................................... 2

C. Co-Trustee Fiduciary Duties ........................................................................................................................... 3

1. When a Co-Trustee’s Fiduciary Duties Begin ......................................................................................... 3

2. Each Co-Trustee Owes Fiduciary Duties ................................................................................................. 3

3. Duty to Participate ................................................................................................................................... 6

4. Duty to Disclose By and Among Co-Trustees ........................................................................................ 6

D. Decision Making by Co-Trustees .................................................................................................................... 7

E. Co-Trustees Liability for Acts of Other Co-Trustee ....................................................................................... 8

1. Improper Delegation ................................................................................................................................ 8

2. Failure to Exercise Reasonable Care ....................................................................................................... 9

3. Failure to Redress Breach of Trust .......................................................................................................... 9

4. Joint and Several Liability ....................................................................................................................... 9

F. Co-Trustee Succession .................................................................................................................................... 9

III. CO-EXECUTORS/ADMINISTRATORS ............................................................................................................ 10

A. Section Overview .......................................................................................................................................... 10

1. Key Points ............................................................................................................................................. 10

2. Key Questions to Consider ....................................................................................................................

10

B. Sources of Authority in Analyzing Co-Executor/Administrator Issues ........................................................ 10

C. Co-Executor/Administrator Fiduciary Duties ............................................................................................... 12

1. When a Co-Executor/Administrator’s Duties Begin ............................................................................. 12

2. Each Co-Executor/Administrator Owes Fiduciary Duties ..................................................................... 12

3. Duty to Participate ................................................................................................................................. 14

4. Duty to Disclose by and Among Co-Executors/Administrators ............................................................ 15

D. Decision Making by Co-Executors/Administrators ...................................................................................... 15

E. Co-Executor/Administrator Liability For Acts of Other Co-Executor/Administrator .................................. 17

1. Failure to Exercise Reasonable Care ..................................................................................................... 17

2. Failure to Redress Breach of Duty......................................................................................................... 17

F. Co-Executor/Administrator Succession ........................................................................................................ 17

IV. CO-AGENTS ........................................................................................................................................................ 18

A. Section Overview .......................................................................................................................................... 18

1. Key Points ............................................................................................................................................. 18

2. Key Questions to Consider .................................................................................................................... 18

B. Sources of Authority in Analyzing Co-Agent Issues .................................................................................... 18

C. Co-Agent Fiduciary Duties............................................................................................................................ 18

1. When a Co-Agent’s Fiduciary Duties Begin ......................................................................................... 20

2. Duty to Participate ................................................................................................................................. 21

D. Decision Making by Co-Agents .................................................................................................................... 22

E. Co-Agent Liability for Acts of Other Agent ................................................................................................. 23

F. Co-Agent Succession ....................................................................................................................................

23

V. OTHER LEGAL THEORIES REGARDING LIABILITY FOR CO-FIDUCIARY’S ACTS & OMISSIONS .. 23

A. Knowing Participation in Breach of Fiduciary Duty ..................................................................................... 23

B. Civil Conspiracy ............................................................................................................................................ 24

VI. BEST DRAFTING PRACTICES ......................................................................................................................... 24

A. Appointment, Resignation, Removal, and Replacement ............................................................................... 24

1. Trustees .................................................................................................................................................. 24

2. Executors/Administrators ...................................................................................................................... 25

Drafting for Multiple Executors, Trustees, and Agents Chapter 13

ii

3. Agents .................................................................................................................................................... 25

B. Decision-Making ........................................................................................................................................... 25

1. Co-Trustees ............................................................................................................................................ 25

2. Co-Executors/Administrators ................................................................................................................ 26

3. Co-Agents .............................................................................................................................................. 26

C. Compensation ................................................................................................................................................ 26

D. Arbitration ..................................................................................................................................................... 26

VII. ALTERNATIVES TO CO-FIDUCIARIES .......................................................................................................... 26

Drafting for Multiple Executors, Trustees, and Agents Chapter 13

1

DRAFTING FOR MULTIPLE

EXECUTORS, TRUSTEES, AND

AGENTS

I. INTRODUCTION

Selecting a fiduciary is one of the most important

decisions to make during the estate planning process.

In fact, this decision “probably has the most frequent

and dramatic impact on family harmony.”

1

Many

people are inherently predisposed to appoint a family

member in these roles because they grossly

underestimate the risk to family harmony and grossly

overestimate the benefits of naming a family member

as a fiduciary.

2

The same tendency applies when

naming co-fiduciaries. A client underestimates the risk

of naming more than one fiduciary and grossly

overestimates the benefits of appointing two or more

people to this role.

This happens for a variety of reasons. Clients

commonly desire to appoint more than one family

member as a fiduciary to avoid feelings of jealously or

resentment. When two people have different skills or

talents, clients believe that by naming both people as

co-fiduciaries, they are getting the best of both worlds.

Similarly, many clients believe that naming co-

fiduciaries imposes a “check and balance” system onto

the administration of their trust, estate, or property.

Appointing co-fiduciaries, however, often creates more

problems than it solves. Appointing co-fiduciaries,

particularly, when a parent requires their children to do

a job as a group, has been referred to as “[t]he number

one opportunity for an estate plan to go wrong.”

3

As

one practitioner notes, naming children as co-

fiduciaries is like putting them in a rowboat:

Imagine loading the children into a rowboat

on a big lake and requiring them to agree on

one destination when their rowboat can go in

only one direction, no matter how many

passengers it holds . . . It is very difficult for

children with different financial profiles,

different values, or different residential states

to be on the same track at all times with each

other, not to mention their respective

spouses. Plans that require children to agree

among themselves when their parents are

both gone are simply fraught with danger.

4

1

Timothy P. O’Sullivan, Family Harmony: An All Too

Frequent Casualty of the Estate Planning Process, 8 Marq.

Elder’s Advisor 253, 257–58 (2007)

2

Id.

3

Robert G. Edge, Children in A Rowboat and Other

Potential Mistakes in Estate Planning, Part I, Prob. & Prop.

6, 7 (2003).

4

Id. at 7-8.

Naming co-fiduciaries carries at least three downsides.

First, serving as a co-fiduciary is a complex job

which is difficult to navigate. When someone is named

as a trustee, executor or agent, he or she is becoming a

fiduciary and taking on numerous and significant legal

duties. Rarely does a fiduciary fully understand all of

his or her fiduciary duties. But when someone

becomes a co-fiduciary, he or she is taking on all the

normal fiduciary duties, plus additional duties — thus,

they are a “fiduciary plus.” It is difficult for each co-

fiduciary to understand his or her duties and/or

potential liability. The governing instruments, statutes,

and common law applicable to such relationships —

particularly, with respect to a co-fiduciary’s duties and

liabilities — vary greatly in their development and

specificity. Determining a co-fiduciary’s particular

duty or liability can be extremely difficult even for the

most seasoned lawyer, let alone a lay person. Rarely

are estate planning clients properly educated on the

duties and liabilities of co-fiduciaries while

contemplating whether to appoint more than one

fiduciary.

Second, each co-fiduciary should ideally work

together; however, each co-fiduciary may attempt to

“row the boat” at different speeds and in a different

direction — or take the oar out of the other co-

fiduciary’s hand altogether. For example, with respect

to decision-making, co-trustees are generally required

to act unanimously, unlike co-executors/administrators

and co-agents, who may generally act independently.

If anything, appointing co-fiduciaries lays the

groundwork for a disordered, inconsistent and

inefficient trust, estate, or property administration.

Appointing co-fiduciaries also increases the risks of

deadlock. Rarely do co-fiduciaries engage in the level

of communication and cooperation necessary to

administer an estate in an efficient and coordinated

manner. Securing the acceptance of an alternative co-

fiduciary to fill a vacancy can be challenging.

Third, adding more than fiduciary typically

increases the cost of administration. Initially, co-

fiduciaries must coordinate their activities amongst

themselves, which usually means it takes longer to

make decisions and to act. There is also inherent

duplication. Staying informed often requires them to

keep and maintain independent records. Due to the

potential for conflicts and disagreements among co-

fiduciaries, each co-fiduciary may need his or her own

legal counsel, adding more costs. Resolving

disagreements/deadlocks and/or remedying the conduct

of a rogue co-fiduciary usually requires court action,

further increasing costs.

For these reasons, many estate planners strongly

recommend against naming co-fiduciaries and many

Drafting for Multiple Executors, Trustees, and Agents Chapter 13

2

institutional/professional fiduciaries will not serve in

such a role.

This article attempts to arm the estate planner with

the information necessary to help a client who is

considering appointing co-fiduciaries to make an

informed decision. This article focuses of the most

common types of co-fiduciaries: co-trustees, co-

executors/administrators, and co-agents. Any attempt

to properly identify the advantages and disadvantages

of naming co-fiduciaries must start with understanding

the relevant law applicable to each role. First, we

identify and discuss the three main sources of authority

which govern co-fiduciary’s duties, powers, and

liabilities: the governing instrument, the applicable

statutes, and the common law. Next, we discuss when

each respective co-fiduciary’s duties begin and identify

the basic fiduciary duties for each type of fiduciary and

the additional duties applicable to a co-fiduciary for

that type of role. We then outline the basic rules

governing decision making for each type of co-

fiduciary as well as the potential liability each

particular co-fiduciary faces for acts of other co-

fiduciary. After laying out the default rules for each

co-fiduciary, we identify the best drafting practices

when appointing co-fiduciaries, particularly how to

address particular issues which are a frequent source of

tension and dispute. Finally, we conclude our

discussion by identifying the advantages and

disadvantages of appointing co-fiduciaries.

II. CO-TRUSTEES

A. Section Overview

1. Key Points

• Attempting to determine a co-trustee’s precise

duty in any given context is complicated due to

the interplay between the terms of the Trust, the

Texas Trust Code, and the common law. The

actual trust instrument should always be carefully

considered – especially to the extent it may

modify the general rules applicable to co-trustees.

• Co-trustees are required to participate in the

administration of the trust unless the co-trustee is

unavailable (absence, illness, suspension,

disqualification or other temporary incapacity) or

has properly delegated the performance of his or

her function.

• Absent contrary terms in the Trust, co-trustees

should act jointly.

• A co-trustee generally cannot commit the entire

administration of the trust to another co-trustee.

• A co-trustee faces potential liability if a duty was

improperly delegated, if the co-trustee failed to

exercise reasonable care to prevent a co-trustee

from committing a serious breach of trust, and/or

if the co-trustee failed to exercise reasonable care

to redress a serious breach of trust.

• Co-trustees are jointly and severally liable if they

unite in a breach of trust.

2. Key Questions to Consider

• Does the settlor understand and appreciate the

level of communication and coordination

generally required for the co-trustees to act jointly

and the increased the costs of administering the

Trust?

• Are the co-trustees capable, from a practical

standpoint, of consistently cooperating?

• Are the co-trustees more likely to agree than

disagree?

• Are the co-trustees capable and willing to

consistently share information with each other?

• Will the co-trustees consistently and properly

document delegation?

• Will each co-trustee consistently exercise

reasonable care to prevent the other co-trustee

from committing a serious breach of trust?

• Will each co-trustee consistently exercise

reasonable care to compel a co-trustee to redress a

serious breach of trust?

• Is there really a need to appoint more than one co-

trustee? (Probably not).

B. Sources of Authority in Analyzing Co-Trustee

Issues

The nature and extent of any co-trustee’s duties,

powers, and liabilities are derived from three main

sources of authority: (1) the terms of the trust;

5

(2) the

Texas Trust Code;

6

and (3) the common law.

7

Texas

Trust Code Section 113.051 states that a trustee shall

administer a trust in good faith, according to its terms,

and the Texas Trust Code.

8

In the absence of any

contrary terms in the trust instrument or contrary

provisions of the Texas Trust Code, in administering

the trust, a trustee shall perform all of the duties

imposed on trustees by the common law.

9

Additionally, Texas Trust Code Section 111.0035(a)

states that, to the extent the terms of the trust do not

provide otherwise, the Texas Trust Code governs: the

duties and powers of a trustee; the relations among

trustees; and the rights and interests of a beneficiary.

10

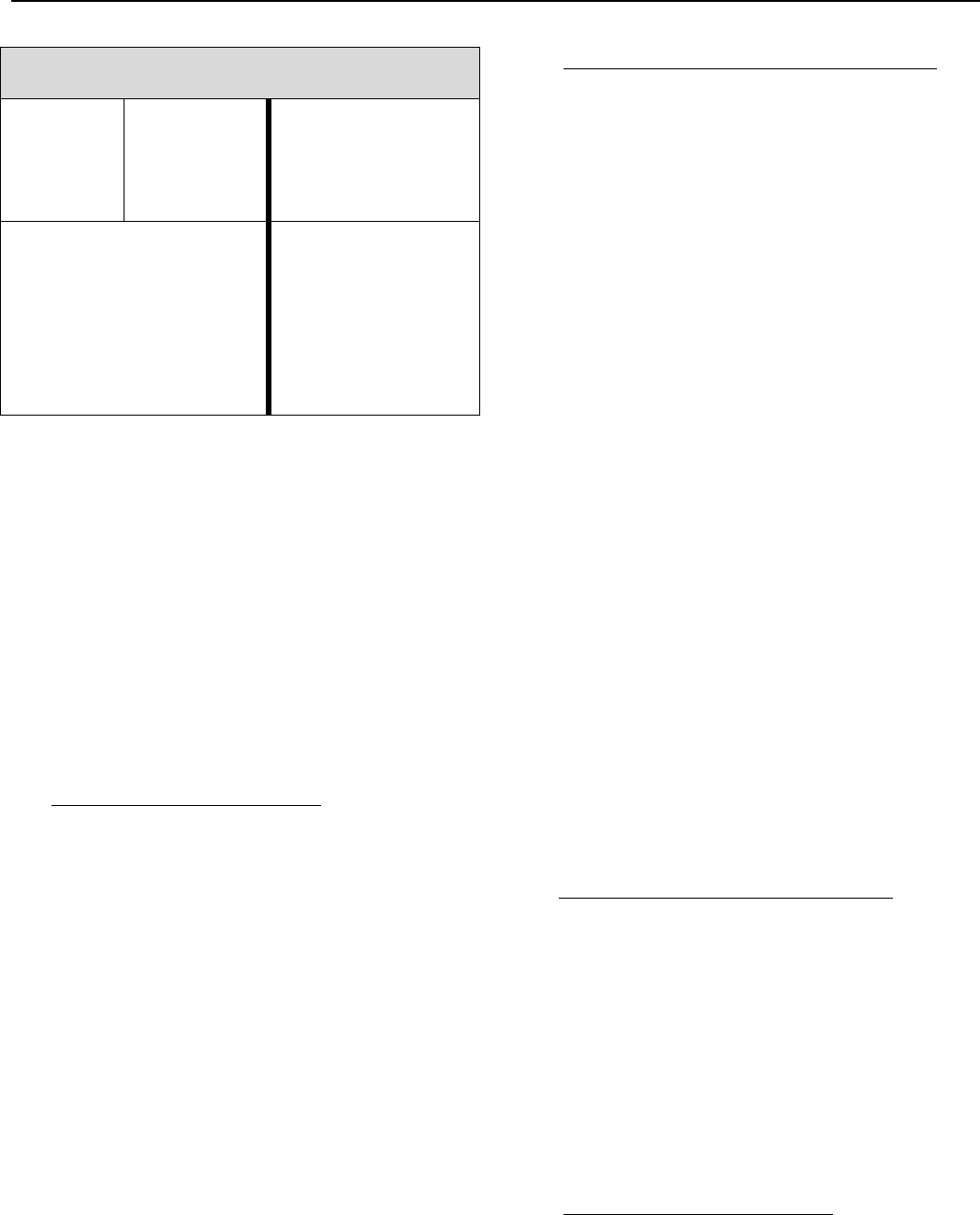

These statutory mandates look something like this:

5

TEX. TRUST CODE § 113.051.

6

Id.

7

Id.; see also Katherine C. Akinc, Inside the Mind of a

Trustee; The Importance of Understanding a Trustee’s

Perspective, The 43

rd

Annual Advanced Estate Planning &

Probate Course, 3 (2019).

8

TEX. TRUST CODE § 113.051.

9

Id.

10

TEX. TRUST CODE § 111.0035(a).

Drafting for Multiple Executors, Trustees, and Agents Chapter 13

3

Good Faith

11

Absent

Contrary

Terms

12

Absent

Contrary

TTC

Provisions

13

Trust Terms Do Not

Provide Otherwise

= Common Law

14

= TTC governs: (a)

duties and powers

of trustee; (b)

relations among

trustees; and (c) the

rights and interests

of a beneficiary

15

Thus, the starting point for determining any trustee’s

duties are the terms of the applicable trust instrument.

The Trust will be construed to ascertain the intent of

the settlor.

16

The settlor’s intent must be ascertained

from the language used within the four corners of the

instrument.

17

Texas Trust Code Section 111.004(15)

actually defines a trust’s “terms” as “the manifest

intent of the settlor.” A trustee’s “duties arise from the

wording of the trust instrument.”

18

With rare

exceptions, the “terms of a trust prevail over any

provision of” the Texas Trust Code.

19

11

TEX. TRUST CODE § 113.051.

12

Id.

13

Id.

14

Id.

15

TEX. TRUST CODE § 111.0035(a).

16

Eckels v. Davis, 111 S.W.3d 687, 694 (Tex. App.—Fort

Worth 2003, pet. denied); Nowlin v. Frost Nat’l Bank, 908

S.W.2d 283, 286 (Tex. App.—Houston [1st Dist.] 1995, no

writ).

17

Id. citing Shriner’s Hosp. for Crippled Children of Tex. v.

Stahl, 610 S.W.2d 147, 151 (Tex. 1980) (applying this

concept to construe a will).

18

Tolar v. Tolar, 2015 WL 2393993, at *4 (Tex. App.—

Tyler May 20, 2015, no pet.) (terms of the trust did not

require trustee to correct flaws in the initial conveyance of

trust property; trustee owed no duty to contribute her own

property to the trust).

19

TEX. TRUST CODE § 111.0035(a) and (b); see also TEX.

TRUST CODE §§ 114.007(c) (a settlor, by the terms of the

trust, may relieve the trustee from any duty or restriction

imposed by the Texas Trust Code or by common law or may

permit the trustee to do or not to do an action that would

otherwise violate a duty or restriction imposed by the Texas

Trust Code or by common law); T

EX. TRUST CODE §

113.029(a)(a trustee must act “in accordance with the terms

and purposes of the trust”).

C. Co-Trustee Fiduciary Duties

1. When a Co-Trustee’s Fiduciary Duties Begin

It is very common for two or more co-trustees to

not start their roles at the exact same time. Thus, each

person appointed as a co-trustee must know when his

or her duties begin. Generally, a person named as

trustee who does not accept the trust incurs no liability

with respect to the trust.

20

However, “the signature of

the person named as trustee on the writing evidencing

the trust or on a separate written acceptance is

conclusive evidence that the person accepted the

trust.”

21

Moreover, the Texas Trust Code states that,

“a person named as trustee who exercises power or

performs duties under the trust is presumed to have

accepted the trust, except that a person named as

trustee may engage in the following conduct without

accepting the trust:

(1) acting to preserve the trust property if, within

a reasonable time after acting, the person

gives notice of the rejection of the trust to:

(A) the settlor; or

(B) if the settlor is deceased or

incapacitated, all beneficiaries then

entitled to receive trust distributions

from the trust; and

(2) inspecting or investigating trust property for

any purpose, including determining the

potential liability of the trust under

environmental or other law.

22

A person named as trustee who does not accept the

trust incurs no liability with respect to the trust.

23

2. Each Co-Trustee Owes Fiduciary Duties

It is well-established under Texas law that a

fiduciary relationship exists between a trustee and the

trust beneficiary.

24

The Texas Trust Code defines the

term “trustee” as “the person holding the property in

trust, including an original, additional, or successor

trustee, whether or not the person is appointed or

confirmed by a court.”

25

Consequently, co-trustees

each occupy the same fiduciary relationship as to the

trust’s beneficiaries — each owes fiduciary duties. A

trustee owes, as a matter of law and fact, all of those

20

TEX. TRUST CODE § 112.009(b).

21

TEX. TRUST CODE § 112.009(a).

22

TEX. TRUST CODE § 112.009(a).

23

TEX. TRUST CODE § 112.009(b).

24

Herschbach v. City of Corpus Christi, 883 S.W.2d 720,

735 (Tex. App.—Corpus Christi 1994, writ denied).

25

TEX. TRUST CODE § 111.004(18) (emphasis added).

Drafting for Multiple Executors, Trustees, and Agents Chapter 13

4

common law fiduciary duties and statutory duties

26

imposed through such relationship, including: the duty

to administer the trust in good faith, according to its

terms, and the Texas Trust Code;

27

the duty of

loyalty;

28

the duty of full disclosure of all material

facts that might affect the beneficiaries' rights,

29

(which

is not lessened by strained relations between the

parties);

30

the duty to account generally;

31

the duty to

26

Ali v. Smith, 554 S.W.3d 755, 762 (Tex. App.—Houston

[14th Dist.] 2018, no pet.)(“The fiduciary duty that an

executor or administrator owes to the estate is derived from

the statutes and common law.”); T

EX. EST. CODE § 351.001

(“The rights, powers, and duties of executors and

administrators are governed by common law principles to

the extent that those principles do not conflict with the

statutes of this state.”).

27

TEX. TRUST CODE § 113.051.

28

Slay v. Burnett Trust, 143 Tex. 621, 640, 187 S.W.2d 377,

388 (1945)(“The trustee’s duty of loyalty [prohibits] him

from using the advantage of his position to gain any benefit

for himself at the expense of his cestui que trust and from

placing himself in any position where his self-interest will or

may conflict with his obligations as trustee.”);

TEX. TRUST

CODE § 114.001 (“The trustee is accountable to a

beneficiary for the trust property and for any profit made by

the trustee through or arising out of the administration of the

trust, even though the profit does not result from a breach of

trust.”);

TEX. TRUST CODE § 117.007 (“A trustee shall

invest and manage the trust assets solely in the interest of the

beneficiaries.”); Nathan v. Hudson, 376 S.W.2d 856, 860

(Tex. Civ. App.—Dallas 1964, writ ref’d n.r.e) (“equity

demands of a fiduciary the highest duty of loyalty”); AUSTIN

WAKEMAN SCOTT & WILLIAM FRANKLIN FRATCHER, The

Law of Trusts Section 170 (4th ed. 1987) (the duty of loyalty

to a trust’s beneficiaries is considered the “most fundamental

duty owed by the trustee to the beneficiaries of the trust ...”);

R

ESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF TRUSTS § 78 (2007).

29

Huie v. DeShazo, 922 S.W.2d 920 (Tex. 1996) (a trustee

owes his or her beneficiaries “a fiduciary duty of full

disclosure of all material facts known to them that might

affect [the beneficiaries’] rights.”); See also T

EX. TRUST

CODE § 113.151(a) (requiring trustee to account to

beneficiaries for all trust transactions).

30

Lesikar v. Rappeport, 33 S.W.3d 282, 296 (Tex. App.—

Texarkana 2000, pet. denied) (citing Montgomery v.

Kennedy, 669 S.W.2d 309, 313 (Tex. 1984).

31

See TEX. TRUST CODE §§ 113.151 and 113.152;

R

ESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF TRUSTS § 83 (2007) (“A trustee

has a duty to maintain clear, complete, and accurate books

and records regarding the trust property and the

administration of the trust, and, at reasonable intervals on

request, to provide beneficiaries with reports or

accountings.”); Corpus Christi Bank & Tr. v. Roberts, 587

S.W.2d 173, 181 (Tex. Civ. App.—Corpus Christi 1979),

aff’d, 597 S.W.2d 752 (Tex. 1980) (“A trustee is charged

with the duty of maintaining an accurate account of all of the

transactions relating to the trust property. He is chargeable

with all assets coming into his hands, the disposition for

which he cannot account.”); Republic Nat. Bank & Tr. Co. v.

Bruce, 130 Tex. 136, 140, 105 S.W.2d 882, 885 (Comm’n

maintain records;

32

the fundamental duty to use the

skill and prudence which an ordinary capable and

careful person will use in the conduct of his own

affairs;

33

the duty of care;

34

the duty to exercise

discretion reasonably;

35

the duty of impartiality;

36

the

App. 1937) (“The relation of a trustee to the trust estate is

personal and one of confidence. He handles another’s

property. The law ought and does demand of him a strict

accounting to the letter and spirit of his contract. It tolerates

no deviation therefrom which amounts to a breach of his

agreement.”) (internal citations omitted).

32

Beaty v. Bales, 677 S.W.2d 750, 754 (Tex. App.—San

Antonio 1984, writ ref’d n.r.e.) (a trustee is required to keep

full, accurate, and orderly records concerning the status of

the trust estate and of all acts performed thereunder);

B

OGERT’s, THE LAW OF TRUSTS AND TRUSTEES § 961 (At a

minimum, “the trustee’s records must be [in such a form] as

to allow it to furnish the beneficiaries (and the court, if

required or otherwise called upon to do so), all information

about its administration of the trust that the beneficiaries

need to protect their interests (or the court needs to

determine whether the trustee has properly administered the

trust.)”).

33

InterFirst Bank Dallas, N.A. v. Risser, 739 S.W.2d 882,

888 (Tex. App.—Texarkana 1987, no writ), disapproved of

on other grounds by Tex. Commerce Bank, N.A. v. Grizzle,

96 S.W.3d 240 (Tex. 2002); R

ESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF

TRUSTS § 77 (2007).

34

See Jewett v. Capital Nat. Bank of Austin, 618 S.W.2d

109, 112 (Tex. Civ. App.—Waco 1981, writ ref’d n.r.e.) (“a

trustee can exercise his fiduciary duty in such a negligent

manner that his lack of diligence will result in a breach of

his fiduciary duty.”); Ertel v. O’Brien, 852 S.W.2d 17, 21

(Tex. App.—Waco 1993, writ denied) (“a trustee commits

breach of trust not only where he violates a duty in bad faith,

or intentionally although in good faith, or negligently but

also where he violates a duty because of a mistake.”);

Republic Nat. Bank & Tr. Co. v. Bruce, 130 Tex. 136, 140,

105 S.W.2d 882, 885 (Comm’n App. 1937) (“Every

violation by a trustee of a duty which equity lays on him,

whether willful or forgetful, is a breach of trust, for which he

is liable”) (internal citations omitted); Lipsitz v. First Nat.

Bank, 288 S.W. 609, 612 (Tex. Civ. App.—Eastland 1926),

aff’d, 293 S.W. 563 (Tex. Comm’n App. 1927), modified,

296 S.W. 490 (Tex. Comm’n App. 1927) (“Equity holds a

trustee liable for every violation of a duty laid upon him,

though such violation arises through oversight or

forgetfulness.”) (internal citations omitted).

35

State v. Rubion, 158 Tex. 43, 51, 308 S.W.2d 4, 9 (1957)

(“The discretion with which a trustee of a support trust is

clothed in determining how much of the trust property shall

be made available for the support of the beneficiary and

when it shall be used is not an unbridled discretion . . . He

may not act arbitrarily in the matter, however pure may be

his motives . . . His discretion must be reasonably exercised

to accomplish the purposes of the trust according to the

settlor’s intention and his exercise thereof is subject to

judicial review and control”).

36

See Perfect Union Lodge v. Interfirst Bank of San Antonio,

713 S.W.2d 391 (Tex.App.—San Antonio 1986), affirmed,

748 S.W.2d 218 (Tex. 1988)(where will created a

Drafting for Multiple Executors, Trustees, and Agents Chapter 13

5

duty to collect, preserve and protect the assets of the

trust;

37

the duty to exercise reasonable care, skill and

caution in selecting agents, establishing the scope and

terms of any delegation of authority, and periodically

reviewing the agent’s actions;

38

the duty, upon the

event of trust termination, to expeditiously make

terminating distributions to the beneficiaries entitled to

receive them;

39

the duty not to misapply fiduciary

funds and property and not to self-deal

40

or commingle

assets,

41

liabilities, or accounts (including those of

testamentary trust with one lifetime beneficiary and a

different remainder beneficiary, trustee must deal impartially

with the two beneficiaries); Brown v. Scherck, 393 S.W.2d

172 (Tex. Civ. App.—Corpus Christi 1965, no

writ)(testamentary trustees owe duty to protect the interests

of the minor contingent beneficiaries, as well as administer

the lifetime beneficiaries’ interests). See also R

ESTATEMENT

(2D) OF TRUSTS §§ 183 (if there are two or more

beneficiaries of a trust, the trustee must deal impartially with

them); 232 (if a trust is created for beneficiaries in

succession, the trustee has a duty to act with due regard to

their respective interests).

37

Hoenig v. Texas Commerce Bank, N.A., 939 S.W.2d 656

(Tex. App.—San Antonio 1996, reh’g overruled and Rule

130(d) motion) (trustee who failed to discover the existence

of trust property, to include it in the trust inventory, to make

the beneficiaries aware of it and to collect rent for its use,

breached its fiduciary duty); Tucker v. Dougherty Roofing

Co., 137 S.W.2d 884, 887 (Tex. Civ. App.—Dallas 1940,

writ dism’d judgm’t cor.) (“The trustee, however, has the

power, as well as the duty, to make expenditures or incur

indebtedness for whatever repairs and changes are

reasonably necessary to the preservation of the property for

the purposes for which it was placed in trust.”) (internal

citations omitted); R

ESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF TRUSTS §

175 (1959); R

ESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF TRUSTS § 176.

38

TEX. TRUST CODE § 117.011.

39

TEX. TRUST CODE § 112.052.

40

Slay v. Burnett Tr., 143 Tex. 621, 640, 187 S.W.2d 377,

388 (1945) (“It is a well-settled rule that a trustee can make

no profit out of his trust. The rule in such cases springs from

his duty to protect the interests of the estate, and not to

permit his personal interest to in any wise conflict with his

duty in that respect. The intention is to provide against any

possible selfish interest exercising an influence which can

interfere with the faithful discharge of the duty which is

owing in a fiduciary capacity.”) (quoting Magruder v.

Drury, 235 U.S. 106, 35 S.Ct. 77, 82, 59 L.Ed. 151, 156

(1914).

41

RESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF TRUSTS § 84 (2007) (“a trustee

has a duty not to commingle property of the trust with the

trustee’s own property.”); see also Moody v. Pitts, 708

S.W.2d 930, 937 (Tex. App.—Corpus Christi 1986, no writ)

(“If a trustee commingles trust funds with the trustee’s own,

the entire commingled fund is subject to the trust . . . [w]hen

a trustee has commingled funds and has expended funds, the

money expended is presumed to be the trustee’s own.”)

(internal citations omitted); Eaton v. Husted, 163 S.W.2d

439, 444 (Tex. Civ. App.—Texarkana 1942), aff’d, 141 Tex.

349, 172 S.W.2d 493 (1943) (“If a man mixes trust funds

himself or herself) and the duty not to seek or obtain,

for himself or herself, any secret, undisclosed benefits,

properties, assets, fees, commissions, payments,

discounts, profits, gains, advantages, dividends,

distributions, revenues, or other ownership interest;

and the duty not to engage in oppressive/hostile

conduct.

42

Moreover, “[a] trustee commits breach of trust not

only where he violates a duty in bad faith, or

intentionally although in good faith, or negligently[,]

but also where he violates a duty because of a

mistake.”

43

Subject to clear and specific limitations, a settlor

is free to draft and execute any trust terms the settlor

desires.

44

Frequently, settlors seek to establish limits

on the liability of his or her chosen trustee so that the

trustee may be unburdened by certain claims of

disgruntled, or even contingent, beneficiaries.

However, the Texas Trust Code prohibits the complete

and absolute exoneration and exculpation of a

fiduciary, and in doing so imposes a “floor” of

fiduciary conduct that even the settlor himself can

neither excuse nor exculpate. Any term of a trust

relieving the trustee of liability is unenforceable to the

extent that such term relieves the liability of a trustee

for a breach trust committed: (a) in bad faith; (b)

intentionally; or (c) with reckless indifference to the

interest of a beneficiary.

45

Each manner of breach of

trust requires a heightened mental attitude by the

trustee. Thus, for every trust in Texas, a trustee will be

liable for, at the very least, breaches of trust the trustee

committed in bad faith, intentionally, or with reckless

with his own * * * the whole will be treated as trust

property, except so far as he may be able to distinguish what

is his own.”) (internal citations omitted).

42

See e.g., TEX. TRUST CODE § 113.082(a)(4)’s “other cause

for removal” and the case thereunder which interprets same

to include ill-will or hostility between a trustee and the

beneficiary or other close family members of that

beneficiary. Akin v. Dahl, 661 S.W.2d 911 (Tex. 1983),

cert. denied, 466 U.S. 938 (1984); Barrientos v. Nava, 94

S.W.3d 270 (Tex. App.—Houston [14

th

Dist.] 2002, no pet.)

(hostility toward beneficiaries’ close family member

justified removal and appointment of another person as the

successor trustee).

43

Ertel v. O’Brien, 852 S.W.2d 17, 21 (Tex. App.—Waco

1993, writ denied).

44

See e.g. TEX. TRUST CODE §§ 111.0035, 112.031

(prohibiting the creation of a trust for an illegal purpose),

114.007 (prohibiting the complete exculpation of a trustee),

1110.035(b)(3) (prohibiting the modification of certain

limitations periods), 1110.035(b)(4) (prohibiting the

modification of the duty to respond to a demand for

accounting or act in accordance with the trust purpose(s)),

and other express limitations on the settlor’s creativity and

ability to deviate from specific provisions of the Texas Trust

Code.

45

TEX. TRUST CODE § 114.007(a).

Drafting for Multiple Executors, Trustees, and Agents Chapter 13

6

indifference to the interest(s) of a beneficiary. Any

trust provision relieving the trustee of liability is

strictly construed.

46

A trustee is relieved of liability

only to the extent that the trust instrument clearly

provides that she shall be excused.

47

Finally, a term in

a trust instrument relieving the trustee of liability for a

breach of trust is ineffective to the extent that the term

is inserted in the trust instrument as a result of an abuse

by the trustee of a fiduciary duty to or confidential

relationship with the settlor.

48

3. Duty to Participate

Many lay persons believe one co-trustee will

“naturally” do most of the work and the other co-

trustee can sit on the sidelines unless and until

“something happens.” The estate planner should dispel

this myth. Both co-trustees are required to participate

and, as discussed below, a co-trustee who wishes to

take a secondary rule must follow specific rules to

properly delegate his or her duties.

A co-trustee has a statutory duty to participate in

the performance of a trustee’s function.

49

The

Restatement (Third) of Trusts § 81 states: “If a trust

has more than one trustee, except as otherwise

provided by the terms of the trust, each trustee has a

duty and the right to participate in the administration of

the trust.”

50

Additionally, “except as otherwise

provided by the terms of the trust, each co-trustee has a

duty, and also the right, of active, prudent participation

in the performance of all aspects of the trust's

administration. Implicit in this requirement of prudent

participation is a duty of reasonable cooperation among

the trustees.”

51

The duty to participate in administration of the

trust contemplates proper delegation and some level of

cooperation, but it does not require an equal level of

effort or activity:

52

46

Neuhaus v. Richards, 846 S.W.2d 70 (Tex. App.—Corpus

Christi 1992, writ granted) (vacated pursuant to settlement

on other grounds, Richards v. Neuhaus 871 S.W.2d 182

(Tex. 1994)).

47

Id. at 75; Jewett v. Capital National Bank of Austin, 618

S.W.2d 109, 112 (Tex. Civ. App.—Waco 1981, writ ref’d

n.r.e.).

48

TEX. TRUST CODE § 114.007(b).

49

TEX. TRUST CODE § 113.085.

50

RESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF TRUSTS § 81 (2007).

51

RESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF TRUSTS § 81 (2007), cmt. c; see

also Ball v. Mills, 376 So.2d 1174, 1182 (Fla. App. 1979)

(“co-trustees owe to each other, as well as to the

beneficiaries of the trust, the duty and obligation to so

conduct themselves as to foster a spirit of mutual trust,

confidence, and cooperation to the extent possible. At the

same time, the trustees should maintain an attitude of

vigilant concern for the proper administration or protection

of the trust business and affairs.”).

52

RESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF TRUSTS, § 81 (2007), cmt. c.

. . . the duty of participation by each of the

co-trustees does not prevent them from

deciding (short of constituting delegation) to

allow one or more of the co-trustees to carry

more of the burden in regard to various

matters, for example, by initiating, analyzing,

reporting, and making recommendations for

reasonably informed action by all of the

trustees.

53

A co-trustee's duty to participate in administering the

trust “does, however, normally prevent the trustees

from “dividing” the trusteeship or its functions in a

manner that is not authorized by the terms of the

trust.”

54

Under the Texas Trust Code, a co-trustee’s duty to

participate in the performance of a trustee’s function

applies unless (1): the co-trustee is unavailable to

perform the function because of absence, illness,

suspension under this code or other law,

disqualification, if any, under this code,

disqualification under other law, or other temporary

incapacity;

55

or (2) the co-trustee properly and

permissibly delegated the performance of its function

to another trustee.

56

The delegation must be made in accordance with

the terms of the trust or applicable law, be

communicated to all other co-trustees, and be filed in

the records of the trust.

57

Delegation is not allowed if

the settlor specifically directs that the function be

performed jointly.

58

Additionally, unless a co-trustee's

delegation is irrevocable, the co-trustee making the

delegation may revoke the delegation.

59

4. Duty to Disclose By and Among Co-Trustees

As a corollary to the duty of a co-trustee to

participate actively in the administration of the trust

and the duty to redress any breach of trust, one

authoritative treatise in the area of trust law has stated

that “a co-trustee, particularly one empowered to

exercise greater control or having greater knowledge of

trust affairs, [has a duty] to inform each co-trustee of

53

Id.

54

Id.

55

TEX. TRUST CODE § 113.085(c)(1).

56

See TEX. TRUST CODE § 113.085 (c); see also

R

ESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF TRUSTS § 81 (2007)(“If a trust

has more than one trustee, except as otherwise provided by

the terms of the trust, each trustee has a duty and the right to

participate in the administration of the trust. Each trustee

also has a duty to use reasonable care to prevent a co-trustee

from committing a breach of trust and, if a breach of trust

occurs, to obtain redress.”)

57

TEX. TRUST CODE § 113.085(c).

58

TEX. TRUST CODE § 113.085(e).

59

Id.

Drafting for Multiple Executors, Trustees, and Agents Chapter 13

7

all material facts that have come to his attention and

that are relevant to the administration of the trust.”

60

These duties exist and arise independently of whether

the other co-trustee’s decision-making vote matters:

Even though a majority of the trustees may

be authorized, by statute or by the trust

instrument, to act for all trustees, the duty to

inform arises from the basic duties of every

trustee to comply with the trust terms, to see

that the trust is properly executed, and to

redress any breach of trust. Thus each trustee

is entitled to access to trust records, to notice

of trustees' meetings, and to participate in all

decisions affecting administration of the

trust.

61

Another trust authority, L

ORING AND ROUNDS: A

TRUSTEE’S HANDBOOK, offers the following

hypothetical to illustrate a co-trustee’s duty to stay

informed:

When co-trustee 1 is uncertain as to whether

co-trustee 2 is reliable, co-trustee 1 should

request from co-trustee 2 all the information

that co-trustee 1 would need to make that

determination. Co-trustee 2 would have a

correlative duty of full disclosure. If the

requested information is not forthcoming,

e.g., co-trustee 2 unreasonably refuses to

hand over vouchers that would support

certain expenses that co-trustee 2 has paid

from the trust estate, then co-trustee 1 would

be well advised to retain independent counsel

to assist with the investigation. If counsel is

unable to extract the information, then the

matter of co-trustee 2’s reliability will have

to be put before the court. Regardless of the

outcome of the litigation, co-trustee 2 clearly

has breached the duty to keep co-trustee 1

fully informed. Accordingly, the court at a

minimum can be expected to hold co-trustee

2 personally liable for co-trustee 1’s

reasonable attorney’s fees.

62

D. Decision Making by Co-Trustees

At common-law, co-trustees had to act

unanimously: “The traditional rule, in the case of

private trusts, was that if there were two or more

trustees, all had to concur in the exercise of their

60

BOGERT’S THE LAW OF TRUSTS AND TRUSTEES § 584,

Duty of co-trustee to be active.

61

Id.

62

Charles E. Rounds, Jr. et. al, LORING AND ROUNDS: A

TRUSTEE’S HANDBOOK, § 7.2.4 (2021 ed.).

powers.”

63

Absent contrary terms in the governing

Trust instrument,

64

the Texas Trust Code provides that

co-trustees “may act” by majority decision.

65

This

language suggests that, unlike coexecutors, co-trustees

cannot generally act independently unless the

instrument provides otherwise.

66

In other words, co-

trustees must act as a group.

67

Disagreements between co-trustees can rise to

such a level that prevents any action and the co-trustees

are essentially deadlocked. As one practitioner has

recently noted, the Texas Trust Code does not provide

an easy solution to deadlocked co-trustees” and “does

not explain what happens when there is a deadlock

between an even number of co-trustees.”

68

THE

RESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF TRUSTS states the answer in

such a situation is the for the co-trustees to seek court

instructions: “if a situation arises in which prudence

requires that the trustees reach a decision and they are

unwilling or unable to do so, the trustees have a duty to

apply to an appropriate court for instructions.”

69

The Texas Declaratory Judgments Act provides

that: “A person interested as or through … a trustee …

63

3 SCOTT AND ASHER ON TRUSTS, WHEN POWERS

EXERCISABLE BY SEVERAL TRUSTEES, § 18.3; see also

R

ESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF TRUSTS, cmt. a (“[I]f there are

three or more trustees their powers may be exercised by a

majority.”).

64

See Berry v. Berry, 646 S.W.3d 516, 530 (Tex. 2022)

(“The Trust Agreement could have altered this rule, but it

does not. Instead, Section 5.2 of the Trust Agreement states

that the Code shall apply “as fully as though its provisions

were written into this instrument.” The result is that the

trustees “act by majority decision.” Tex. Prop. Code §

113.085(a).”)

65

TEX. TRUST CODE § 113.085(a); see also RESTATEMENT

(THIRD) OF TRUSTS § 81 (2007), cmt. a (“[I]f there are three

or more trustees their powers may be exercised by a

majority.”).

66

Compare TEX. TRUST CODE § 113.085 with TEX. EST.

CODE § 307.002; see also Shellberg v. Shellberg, 459

S.W.2d 465, 470 (Civ. App.—Fort Worth 1970, ref. n.r.e.)

(“The trust instrument conveyed the property to two trustees

and provided that their powers were joint; the management,

control and operation of the trust was to be by the joint

action of the two trustees.”).

67

BOGERT’S THE LAW OF TRUSTS AND TRUSTEES § 554

(“The powers of trustees of a private trust, whether they are

imperative or discretionary, personal or attached to the

office, are held jointly, in the absence of statute or contrary

direction in the trust instrument. The trustees are regarded as

a unit. They are joint tenants of realty in the usual case. They

hold their powers as a group so that their authority can be

exercised only by the action of all the trustees. ‘When the

administration of a trust is vested in co-trustees, they all

form but one collective trustee.’”).

68

David F. Johnson, The More the Merrier? Issues Arising

from Co-Trustees Administering Trusts, 45

th

Annual

Advanced Estate Planning & Probate (2021), 20.

69

RESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF TRUSTS § 81 (2007), cmt. c.

Drafting for Multiple Executors, Trustees, and Agents Chapter 13

8

may have a declaration of rights or legal relations in

respect to the trust or estate: … (2) to direct the

executors, administrators, or trustees to do or abstain

from doing any particular act in their fiduciary

capacity; (3) to determine any question arising in the

administration of the trust or estate, including

questions of construction of wills and other

writings...”

70

Additionally, the Texas Trust Code states

that a court has jurisdiction “over all proceedings by or

against a trustee and all proceedings concerning trusts,

including proceedings to: (1) construe a trust

instrument; (2) determine the law applicable to a trust

instrument; … (4) determine the powers,

responsibilities, duties, and liability of a trustee; … (6)

make determinations of fact affecting the

administration, distribution, or duration of a trust; (7)

determine a question arising in the administration or

distribution of a trust; (8) relieve a trustee from any or

all of the duties, limitations, and restrictions otherwise

existing under the terms of the trust instrument or of

this subtitle…”

71

Consequently, co-trustees are authorized to seek

court instruction where they are deadlocked on an

important decision. “This remedy, however, has its

drawbacks in that it is expensive and also there is

necessary delay involved in filing suit, joining in

proper or necessary parties, presenting the issue to the

court, and obtaining a final ruling.”

72

Co-trustees should carefully consider their

positions when deadlock appears likely or has already

occurred. A co-trustee who takes a position that is

especially unreasonable or refuses to participate or

reasonably cooperate, risks removal.

73

The Texas

Trust Code provides that: (a) A trustee may be

removed in accordance with the terms of the trust

instrument, or, on the petition of an interested person

and after hearing, a court may, in its discretion, remove

a trustee and deny part or all of the trustee’s

compensation if: (1) the trustee materially violated or

attempted to violate the terms of the trust and the

violation or attempted violation results in a material

financial loss to the trust; (2) the trustee becomes

incapacitated or insolvent; (3) the trustee fails to make

an accounting that is required by law or by the terms of

the trust; or (4) the court finds other cause for

removal.

74

70

TEX. CIV. PRAC. & REM. CODE § 37.005.

71

TEX. TRUST CODE § 115.001.

72

David F. Johnson, The More the Merrier? Issues Arising

from Co-Trustees Administering Trusts, 45

th

Annual

Advanced Estate Planning & Probate (2021), 21.

73

David F. Johnson, The More the Merrier? Issues Arising

from Co-Trustees Administering Trusts, 45

th

Annual

Advanced Estate Planning & Probate (2021), 21.

74

TEX. TRUST CODE § 113.082.

A receivership is another option to break a

deadlock. The Texas Trust Code authorizes

establishing a receivership to remedy a breach of trust

that has occurred or may occur: “(a) To remedy a

breach of trust that has occurred or might occur, the

court may: … (5) appoint a receiver to take possession

of the trust property and administer the trust.”

75

Alternatively, co-trustees may seek declaratory relief

as to the validity of a decision by the majority of the

co-trustees under the decision-making process set forth

in the trust instrument.

76

E. Co-Trustees Liability for Acts of Other Co-

Trustee

In addition to facing liability for his or her own

conduct, a co-trustee can be liable for the

acts/omissions of the other co-trustee(s). In deciding to

appoint co-trustees, rarely does a settlor understand

that he or she is asking a family member to take on

fiduciary duties plus additional duties. Whether and to

what extent a duty has been properly delegated is a

highly technical analysis. Similarly, it may be hard to

determine in certain factual circumstances whether a

co-trustee has properly complied with his or her duty

of care to prevent another co-trustee from committing a

serious breach of trust or to redress a breach of trust

which has already occurred. These risks and

uncertainties should be addressed with a settlor any

time appointing co-trustees is being contemplated.

1. Improper Delegation

As noted, a trustee cannot properly commit the

entire administration of the trust to an agent or other

person, except as permitted to do so by the terms of the

trust.

77

Analyzing whether any delegation was

appropriate requires a careful review of the terms of

the trust, since “the terms of the trust may permit a

trustee to delegate to agents or other persons (e.g., a

co-trustee) the administration of the trust or the

performance of acts that could not otherwise properly

be delegated.”

78

Although the administration of a trust

may not typically be delegated in full, a trustee may

delegate fiduciary authority for a variety of purposes to

properly selected, instructed, and supervised or

monitored agents.

79

75

TEX. TRUST CODE § 114.008.

76

Duncan v. O’Shea, 2020 WL 4773058, at *1 (Tex. App. –

Amarillo Aug. 17, 2020, no pet.) (holding trial court

properly granted co-trustee’s requires for a declaration that a

majority of the co-trustees had the power to sell real

property of the trust over objection of dissenting co-trustee

according to the terms of the trust and applicable law).

77

RESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF TRUSTS § 80, cmt. c (2007).

78

RESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF TRUSTS § 80, cmt. h (2007).

79

RESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF TRUSTS § 80 (2007).

Drafting for Multiple Executors, Trustees, and Agents Chapter 13

9

The Texas Trust Code allows a trustee to delegate

to a co-trustee the performance of a trustee's function

unless the settlor specifically directs that the function

be performed jointly.

80

The delegation must be made in

accordance with the terms of the trust or applicable

law, be communicated to all other co-trustees, and be

filed in the records of the trust.

81

The trustee may also have a duty to monitor. For

example, the Texas Trust Code permits a trustee to

delegate the investment and management functions that

a prudent trustee of comparable skills could properly

delegate under the circumstances.

82

However, in that

instance, the trustee shall exercise reasonable care,

skill, and caution in, among things, “periodically

reviewing the agent's actions in order to monitor the

agent's performance and compliance with the terms of

the delegation.”

83

2. Failure to Exercise Reasonable Care

Texas Trust Code § 114.006 addresses the liability

of co-trustees for the acts of other co-trustees. Texas

Trust Code § 114.006(b) imposes an affirmative duty

on each trustee to exercise reasonable care to prevent a

co-trustee from committing a serious breach of trust.

84

S

COTT & ASHER ON TRUSTS, discusses the duty to

supervise a co-trustee’s conduct:

All trustees are under a duty to participate in

the administration of the trust and to use

reasonable care to prevent co-trustees from

committing breaches of trust. Even in the

absence of improper delegation, a trustee

who, by failing to exercise reasonable care in

supervising the conduct of a co-trustee,

allows the co-trustee to commit a breach of

trust is liable. Thus, a trustee who permits a

co-trustee to have sole custody of the trust

property may be liable if the later

misappropriates it. So also, if a trustee has

reason to suspect that a co-trustee is

committing or attempting to commit a breach

of trust and does not take reasonable steps to

prevent the co-trustee from so doing, and the

trustee commits a breach of trust, both are

liable.

85

Under the Texas Trust Code, a trustee who does not

join in an action of a co-trustee is not liable for the co-

trustee's action, unless the trustee failed to exercise

80

TEX. TRUST CODE § 113.085(e).

81

TEX. TRUST CODE § 113.085(c).

82

TEX. TRUST CODE § 117.011(a).

83

TEX. TRUST CODE § 117.011(a)(3).

84

TEX. TRUST CODE § 114.006(b).

85

4 SCOTT AND ASHER ON TRUSTS, When Powers

Exercisable by Several Trustees,

§ 24.29.

reasonable care.

86

The same rule essentially applies to

a dissenting and reluctant co-trustee: a dissenting

trustee who joins in an action at the direction of the

majority of the trustees and who has notified any co-

trustee of the dissent in writing at or before the time of

the action is not liable for the action, unless such

dissenting co-trustee failed to exercise reasonable

care.

87

These rules incentivize co-trustees to not only

stay informed about the administration of the trust, but

also to voice their objections at or before the time the

act to which they disagree is taken.

3. Failure to Redress Breach of Trust

Texas Trust Code § 114.006(b) imposes an

affirmative duty on each trustee to exercise reasonable

care to compel a co-trustee to redress a serious breach

of trust.

88

Even a dissenting co-trustee must exercise

reasonable care: a dissenting trustee who joins in an

action at the direction of the majority of the trustees

and who has notified any co-trustee of the dissent in

writing at or before the time of the action is not liable