Determining Patient’s Satisfaction with Medical Care

Author: Youssef Habbal

BS, MS, PhD candidate (International School of Management, Paris)

Lecturer: American University of Science and Technology, Beirut, Lebanon.

Email:

Address: Ras El Nabeh, Omar bin Khattab str, Kanafani Bldg,

20520011 Beirut, Lebanon

Abstract:

The need to achieve patient satisfaction should make medical service providers

realize the importance of healthcare marketing. Therefore, Hospitals, Clinics and

Medical services should actively determine the needs of health care customers and

tailor their services to meet those needs and to attract patients to use these services.

The purpose of this paper is to briefly review the literature about how the quality of

medical services is perceived and to propose a research model in order to determine

the degree of patient satisfaction with medical care.

Results showed that trust is the main antecedent of satisfaction in medical care and

that improving communication skills and developing better patient rapport skills for

dealing with adverse patient behavior are essential determinants of patient’s

satisfaction.

Introduction

Customer satisfaction is a person’s feeling of pleasure or disappointment resulting for

comparing product/service’s perceived performance or outcome in relation to his or her

expectations. As this definition makes clear, satisfaction is a function of perceived

performance and expectations. If the performance falls short of expectations, the

customer is dissatisfied. If the performance matches the expectations, the customer is

satisfied. If the performance exceeds expectations, the customer is highly satisfied or

delighted.

Recently, Providers of medical services have awakened to consumer challenges,

competition, quality, and the realities of marketing. With these changes, a related and

equally important issue has emerged, the client-provider relationship on the overall

medical service quality evaluation. Clients are increasingly frustrated with the

commercialization of medical service, proliferated bureaucratic health care system and

weakened client-provider relationship. (Astrachan, 1991; Bryant et al, 1998; Sinay,

2002).

To achieve patient satisfaction, medical service providers should realize the importance

of healthcare marketing. Therefore, Hospitals, clinics and medical service providers

should make effort to develop relationship marketing with their patients, determining

their needs, and tailoring their services to meet those needs.

Clients’ definition of medical services quality

To define quality of medical services one must first unravel a mystery; the meaning of

quality itself. The quality mystery -something real, capable of being perceived and

appreciated, but not subject to measurement- has been puzzling us since the Code of

Hammurabi was set down. Two sources were used to provide several general clues: the

works of Donabedian and Steffen.

Avedis Donabedian, the leading thinker in modern medical quality assurance, states that

“it is useful to begin with the obvious by saying that quality is a property that medical

service can have in varying degrees.” It follows that an assessment of quality is a

judgment whether a specified instance of medical service has this property, and if so, to

what extent (Donabedian, 1980). This first definition portrays a “metaphysical sense”

since it reflects the philosophic tradition of using “quality” in the same sense as

“property.” Thus, philosophers speak of primary qualities as those properties that depend

on person’s perceptions.

On the other hand, Grant Steffen defines quality as “the capacity of an object with its

properties to achieve a goal”. This definition shifts the focus of quality from the property

to the capacity to achieve a goal and thus makes the goal the factor that determines

quality. It follows, then, that quality can be measured only with reference to a goal. The

more completely the goal is achieved, the higher we will judge the quality. Accordingly,

quality of medical services is “the capacity of the elements of that service to achieve

legitimate medical and nonmedical goals” set by the patient with the assistance of the

physician. Medical goals are determined by the nature of the patient’s illness and

nonmedical goals are determined by the needs of the physician and the patient to

maintain autonomy. These goals are limited by what is legally permitted, ethically

acceptable, and medically possible (Steffen, 1988). This second definition of quality

portrays a “preference sense” since it implies preference and value. Thus, we prefer

things that satisfy our needs, fulfill our expectations, and achieve our goals over those

things that do not. Those things that we prefer have quality, some having more quality

than others do.

This preferential sense must be distinguished from the metaphysical sense proposed by

Donabedian. Quality in the metaphysical sense is identical with the properties of an

object and does not imply preference. In contrast, quality in the preferential sense is

identical not with the properties to achieve a goal, this goal being a state of affairs that is

preferred to other states.

It is very obvious that clients, individually and collectively, contribute in many ways to

the definition of medical service quality. One way is by influencing what is included in

the definition of “health” and “health services” (Donabedian, 1980). It is generally

believed that clients tend to have a broader view of theses things and, as a result, they

expect more from the medical services than the medical services are willing or able to

give. Clients contribute very heavily to the definition of medical service quality with their

values and expectations regarding the management of the interpersonal process. In this

context, clients are the primary definer of what quality means.

Client satisfaction in medical services

Client satisfaction is of prime importance as a measure of the quality of medical services

because it gives information on the provider’s success at meeting those client values and

expectations, which are matters on which the client is the ultimate authority. The

measurement of satisfaction is, therefore, an important tool for research, administration,

and planning. The informal assessment of satisfaction has an even more important role in

the course of each practitioner-client interaction, since it can be used continuously by the

practitioner to monitor and guide that interaction and, at the end, to obtain a judgment on

how successful the interaction has been (Donabedian, 1980).

However, client satisfaction also has some limitations as a measure of quality. Clients

generally have only a very incomplete understanding of the science and technology of

care, so that their judgments concerning these aspects of care can be faulty. Moreover,

clients sometimes expect and demand things that it would be wrong for the practitioner to

provide because they are professionally or socially forbidden, or because they are not in

the client’s best interest. For example, if the patient (client) is dissatisfied because his

unreasonably high expectations of the efficacy of medical science have not been met, one

could argue that the practitioner has failed to educate the patient. And when the patient is

dissatisfied because a desired service has been denied, the grounds for that denial could

be of questionable validity, especially if is assumed that the primary responsibility of the

practitioner is to the individual client, and that the client is, ultimately, the beat judge of

his own interests, provided that he is mentally unimpaired and properly informed. These

limitations do not lower the validity of patient satisfaction as a measure of quality, but

they are the best representation of certain components of the definition of quality,

namely, those which pertain to client expectations and valuations (Donabedian, 1980).

The clients’ view of Medical Service Quality

People are seldom asked to say what they think the quality of medical service means.

What is good doctor, or clinic? What is a bad one? What does the respondent like and

dislike about his doctor, clinic, and so on? From these opinions about the attributes of

providers, inferences must be drawn about the ingredients of “goodness” in the care they

give. In order to make the task simpler, the respondent is often given a list of attributes

and asked to rank all these or select some. When this is done, the questioner’s view of the

boundaries and content of the concept of quality may be imposed on the respondent.

Moreover, the respondent’s answers are influenced by his interpretation of the language

in which the choices are presented.

Much of the literature on client views of the good doctor or clinic pertains to the relative

importance of the technical management of illness as compared to the management of the

relationship between the client and the practitioner. In the early 1950s, Rose Laub Coser

(1956) conducted “standardized interviews” with 51 patients at a hospital. When Coser

asked “what is your idea of a good doctor?” the answers given by the patients seemed to

classify them into two distinct groups. A little more than half of the patients saw the good

doctor as one who provided kindness, love, and security. He “talks nice, shows interest,

makes you feel good, so all-knowing and all-powerful that you can rest secure in his safe-

keeping.” On the other hand, the remaining patients focused on the doctor’s scientific and

professional competence. Also Coser asked “what makes a good patient?” and again a

little more than the half thought that a good patient should be to some degree

autonomous, whereas almost all the rest thought that the patient should be totally

submissive. In addition, those who defined goodness in technical-professional terms saw

the patient as rather autonomous and the others, who defined doctor’s goodness in term

of kindness, personal interest, and care, saw the patient as submissive.

Later on, Friedson (1961) interviewed patients about their reasons for liking and disliking

certain doctors, and for continuing to receive care from one but not from another.

Friedson concluded that “patients assume that all doctors possess a minimal competence”

and they are concerned only with degrees of competence. The patients defined quality in

terms of certain behaviors on the part of the physician, or attributes of his care, which

they felt denoted personal interest or competence. In addition, these two traits were,

themselves, interrelated, since they were necessary conditions to a highly individualized

application of medical knowledge to each patient condition, in a manner that took

account of the patient’s needs, expectations, and preferences.

The attributes of good care identified by Friedson were further studied in several

researches. Cartwright (1967) interviewed patients to define the appreciated qualities for

doctors. Majority of the responses showed the most appreciated qualities related to the

manner or personality of the doctor and the way they looked after the patient.

Another study by Sussman et al (1967) confirmed that the attributes of interpersonal and

communication skills were highly ranked by patients. Their results corresponded to the

findings of Cartwright in showing an emphasis on the management of the interpersonal

process, and to the findings of Coser in revealing two different orientations.

Quality assessment

1- Quality as a comparison between Expectations and Performance

Lewis and Booms (1978) claimed that service quality involves a comparison of

expectations with performance. In line with this, Gronross (1982) developed a model in

which he contends that clients compare the service they expect with perceptions of the

service they receive in evaluating service quality. He postulated that two types of service

quality exist: technical quality, which involves what the client is actually receiving from

the service, and functional quality, which involves the manner in which the service is

delivered. Furthermore, Tarantino (2004) stressed on the fact that patients’ satisfaction is

truly measured based on two factors, their expectations of the service and their

perceptions of the actual service they received.

Parasuraman et al (1988) defined service quality as “a global judgment, or attitude,

relating to the superiority of the service.” They link the concept of service quality to the

concepts of perceptions and expectations as follows: “Service quality is viewed as the

degree and direction of discrepancy between clients’ perceptions and expectations”

(Parasuraman et al, 1985). They developed an instrument known as SERVQUAL for

measuring customers’ perceptions of service quality ( Parasuraman et al 1988 & 1991).

Additionally they developed a model of service quality based on the magnitude and

directions of five “gaps,” which include client expectations-experiences discrepancies in

addition to differences in service design, communications, management, and delivery

(Zeithaml et al, 1988). The five gaps are:

- Gap 1: Difference between client’s expectations and management’s perceptions

of these expectations.

- Gap 2: Difference between management’s perceptions of clients’ expectations

and service quality specifications.

- Gap 3: Difference between service quality expectations and service quality

delivery.

- Gap 4: Difference between service quality and the influence of external

communications on clients’ expectations.

- Gap 5: Difference between clients’ expectations and clients’ perceptions of

service delivery, which is caused by the combined influences of Gaps 1 to 4.

Later on, Parasuraman et al (1994), published a model in which consumers have a “zone

of tolerance” bounded by adequate and desired service levels. If a service encounter does

not meet their minimal performance criteria, then they become dissatisfied and develop a

negative image of the service.

2- Quality Evaluations in Medical Services

According to Donabedian (1988), the measurement of effective medical service system is

described in terms of “Structure, processes, and outcomes.”

- Structure denotes the attributes of the settings in which care occurs. This includes the

attributes of material resources, human resources, and organizational structure.

- Process denotes what is actually done in giving and receiving care. It includes the

patients’ activities in seeking care and carrying it out as well as the physician’s activities

in making a diagnosis and recommendation or implementing treatment.

- Outcome denotes the effects of care on the health status of patients and population.

Improvement in the patient’s knowledge and salutary changes in the patient’s behavior

are included under a broad definition of health status, and so is the degree of the patient’s

satisfaction with care.

Research Model Development:

In medical care literature, perceptions are defined as patients’ beliefs concerning the

medical services received or experienced. Expectations are defined as desires or wants of

the patients or in other word what they feel an ideal standard of performance the

physician should offer rather than would offer. These expectations may be based, in part

or total, on past relevant experiences, including those gathered vicariously. For example,

one may form expectations about a visit to a physician from one’s own experience or by

observing or being informed about someone else’s experience.

In computing medical service-quality gaps, a modified version of the SERVQUAL is

more appropriate due to the unique characteristics of physicians and physician-client

relationship. For example, physicians typically have advanced degrees, meet credential

requirements, and often hold equity positions in their organizations.

The interactive nature of medical services indicates a need to examine the perceptions of

both parties involved in the service encounter. Overall, physicians’ perceptions most

directly affect the design and delivery of the services offered, whereas clients perceptions

more directly determine evaluation of the service delivered. Hence, both parties are very

important and must be considered if a more thorough understanding of service quality is

to be gained.

Potential gaps that relate to expected and experienced service and represent both sides of

the service exchange should have a significant impact on the service evaluation. In

general, these gaps include:

- An intra-client gap between client expectations and client experiences and,

- Client-physician gaps between client expectations and physician perceptions of

those expectations, as well as between client experiences and physician

perceptions of those experiences.

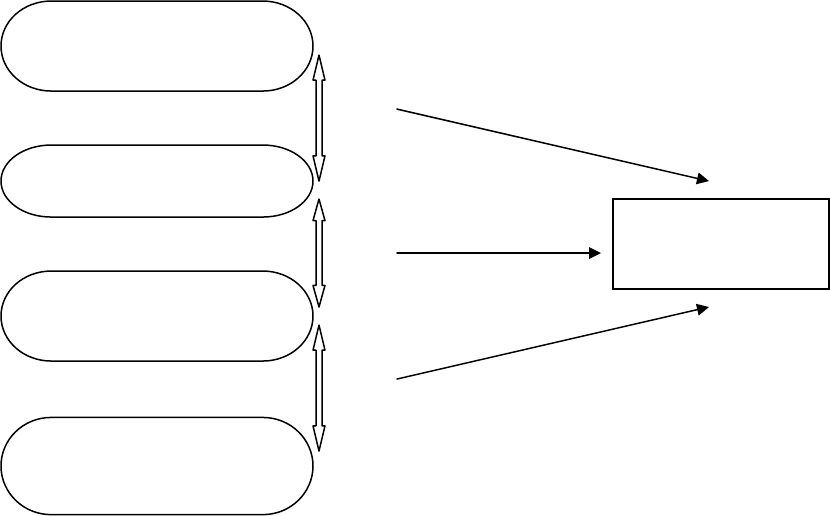

The gaps proposed are: See Figure 1.

Gap1: Client expectations-client experiences

Gap2: Client expectations-physician perceptions of client expectations

Gap3: Client experiences-physician perceptions of client experiences

Gap 2

Gap 1

Gap 3

Physician Perceptions of

Client Ex

p

ectations

Client Expectation

Client Experiences

Outcome

Evaluation

Physician Perceptions of

Client Experiences

(Fig.1)

Implicit in these gaps are the following hypotheses to be tested:

H1: the level of positive client evaluation of the clinical service is inversely related to

gap1

H2: the level of positive client evaluation of the clinical service is inversely related to

gap2

H3: the level of positive client evaluation of the clinical service is related positively to

gap3

Gap1 hypothesized to be related to positive client evaluation because it measures the

difference between client expectations and experiences, a standard approach to determine

satisfaction and assessing an encounter.

Gap2 and Gap3 are hypothesized to be related to positive client evaluation because they

reflect differences between client’s expectations/experiences and the physician’s

perceptions of them. The physician would design, develop, and deliver the service

offering on the basis of his/her perceptions of client expectations. Likewise,

modifications to the service offering would be affected by the physician’s perceptions of

client experiences. Whether these experiences exceed, match, or are below expectations

can have a profound effect on future client-physician relationships. For example, if a

physician exceeds the client’s expectations, a true person-to-person bonding relationship

often is initiated or furthered, which in turn builds client loyalty and may also encourage

referrals. Therefore, one can argue that gaps in either of these gaps areas can directly

influence positive client evaluation.

In addition, examining the relationships between medical service quality, patient

satisfaction, and patient intention to return for the same medical service provider in case a

need arises should be considered. The following three additional hypotheses are to be

tested:

H4: client satisfaction is an antecedent of medical service quality.

H5: client satisfaction has a significant impact on patient’s behavioral intention.

H6: Medical service quality has a significant impact on patient’s behavioral intention.

Proposed conceptual model of Medical Service Quality:

(Fig.2)

Process Outcome Impact

Patient

Satisfaction

Expectation

PpP

Perceived

Interpersonal

Management

Medical

Services

Quality

Continuity

Of Care

Research Design:

To address the model developed based on the literature review, a survey technique was

followed. The key determinants of patient satisfactions were determined via focus groups

and questionnaires.

The questionnaire were be based on past researches in the medical area (Ware et al, 1975;

Donabedian, 1980; Brown and Swartz, 1989; Rubin et al, 1990; Badrick, 1996; James,

2002; Tam, 2004; Gummerus et al, 2004; Tarantino, 2004; and Willging, 2004)

The questions developed were tested through focus group techniques. In this case, three

groups of 10 participants each (6 regular patients, 2 medical staff, 2 physicians) convened

in a round table discussion in the presence of a moderator (the researcher who has

reviewed the literature extensively). The meeting was for two hours and the purpose was

to discuss the elements of the questionnaire proposed by the moderator who has listed the

questions based on the literature. The moderator did not interfere but stimulated the

discussion and then summed up the results of the three meetings into one single

questionnaire.

In addition, care was taken to include statements that correspond to the ten critical

dimensions of service quality proposed by Zeithaml et al (1990). Those critical

dimensions or evaluation criteria that patients use in assessing service quality are:

1) Courtesy: Politeness, respect, consideration, and friendliness of physicians and

medical staff.

2) Access: Approachability and ease of contact.

3) Communication: Keeping patients informed in the language they can understand

and listening to them.

4) Understanding: Making the effort to know patients and their obligations.

5) Empathy: Caring, individualized attention provided to patients.

6) Reliability: Ability to perform the promised service dependably and accurately.

7) Tangibles: Appearance of physical facilities, equipment, staff, and

communication material.

8) Responsiveness: Willingness to help patients and provide prompt service.

9) Competence: Possession of the required skills and knowledge to perform the

service.

10) Assurance: Knowledge and courtesy of physicians and their ability to convey trust

and confidence.

These evaluation criteria are a function of the expectations patient bring to the service

situation, and experiences patient received during the encounter. Expectations reflects

what the patient hopes to receive, while experience reflects what the patient perceive is

getting. See Appendix 1.

Data Analysis

Descriptive Profile:

A total of 800 questionnaires were distributed to a convenient selection of patients (750)

and physicians (50). A total of 700 completed and useable questionnaires (654 patients

and 46 physician), 87.50% were used for the analysis. The remaining 100 questionnaires

were not used for the analysis because they were more than 15% incomplete.

Patients’ Perceived Expectation and Experience in Relation to Medical Service

Quality:

Underpinned by the disconfirmation paradigm, the patients’ expectations or satisfaction

in relation to the Medical Service attributes were measured by asking the respondents to

rate: 1-Expectations / 2-Experiences.The statements in the questionnaire are rated on a 5-

point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree = 1” to “Strongly Agree = 5”

Reliability was measured by the Cronbach's alpha. First results showed a weak reliability

for the 42 items present in the questionnaire. However, narrowing down the items to 21

intercorrelated variables, resulted in a strengthened reliability of 0.779 Cronbach’s alpha:

Hypothesis testing

H1: the level of positive client evaluation of the clinical service is inversely related to

gap1 (client Expectation-client experience).

Several variables were taken and cross-tabulated in order to get the Chi-square test. The

combination of variables and their results shows the cross-tabulation to have a

significance level of almost 0 which indicates that these variables are highly interrelated;

however they are positively related thus we reject H1.

H2: the level of positive client evaluation of the clinical service is inversely related to

gap2 (client expectations-physician perceptions of client expectations).

The Pearson’s chi-square test shows that there is a strong relationship between the

variables; however, if we look at the cross-tabulation and examine the raw percentages of

the variables we can conclude that they are inversely related, and thus we accept H2.

H3: the level of positive client evaluation of the clinical service is related positively to

gap 3 (Client experiences-physician perceptions of client experiences)

The data analysis through cross-tabulation shows that the level of positive client

evaluation of the clinical service is highly related to gap 3, and this relationship is

positively related since the clients’ expectation increase as the expectation evaluation

increase. Therefore, we accept H3.

H4: client satisfaction is an antecedent of medical service quality

The chi-square test shows that client satisfaction is highly dependent on medical service

quality (level of significance is 0.00), thus, we accept H4.

H5: client satisfaction has a significant impact on patient’s behavioral intention.

Once again we have used the chi- square test to test the null hypothesis (H5), and we can

see that client satisfaction has a highly significant impact patient’s behavioral intentions,

since the correlation indicator is very high (0.0<0.05). Therefore, we accept H5.

H6: Medical service quality has a significant impact on patient’s behavioral intention.

After doing the cross tabulation to test H6, we concluded that medical service quality is

highly correlated to patient’s behavioral intention (level of significance is almost 0.00).

Thus, we accept the null hypothesis H6.

Factor Analysis

The variance explained by the initial solution, extracted components, and rotated

components is displayed. This first section of the table shows the Initial Eigenvalues.

The Total column gives the eigenvalue, or amount of variance in the original variables

accounted for by each component. Table 1.

Initial Eigenvalues Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings

Factor

Total % of Variance Cumulative % Total % of Variance Cumulative % Total % of Variance Cumulative %

1

5.157 24.559 24.559 4.805 22.879 22.879 3.936 18.743 18.743

2

2.510 11.951 36.510 2.219 10.569 33.448 2.732 13.010 31.753

3

1.544 7.353 43.863 1.010 4.811 38.259 .928 4.420 36.173

4

1.386 6.598 50.461 .915 4.359 42.618 .882 4.201 40.374

5

1.231 5.861 56.322 .711 3.387 46.005 .857 4.082 44.456

6

1.173 5.583 61.906 .635 3.022 49.027 .697 3.319 47.775

7

1.018 4.848 66.754 .511 2.432 51.459 .675 3.212 50.988

8

1.002 4.774 71.528 .394 1.877 53.336 .493 2.348 53.336

9

.856 4.075 75.602

10

.777 3.702 79.304

11

.717 3.415 82.719

12

.583 2.777 85.496

13

.532 2.532 88.028

14

.510 2.431 90.458

15

.444 2.114 92.572

16

.422 2.008 94.580

17

.375 1.786 96.366

18

.268 1.275 97.641

19

.216 1.026 98.668

20

.184 .875 99.543

21

.096 .457 100.000

Extraction Method: Principal Axis Factoring.

Only eight factors in the initial solution have eigenvalues greater than 1.

Together, they account for almost 71% of the variability in the original variables. This

suggests that three latent influences are associated with medical service satisfaction, but

there remains room for a lot of unexplained variation.

However in the cumulative variability the factors are reduced to three only since they

only have the eigenvalues greater than one.

The cumulative variability explained by these three factors in the extracted solution is

about 38%, a difference of 6% from the initial solution.

The scree plot helps us to determine the optimal number of components. The eigenvalue

of each component in the initial solution is plotted. (Fig.3)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21

Factor Number

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Eigenvalue

Scree Plot

Factor Matrix. Table 2.

VARIABLES 1 2 3

MyDrIsCarefulToExplainWh

atIAmExpectedToDo

.763

MyDrExaminesMeCarefully

BeforeDecidingWhatIsWron

g

.604

IHaveCompleteTrustInMyDr

.447

MyDrTakesRealInterestInM

e

.714

IHaveMyDrSFullAttentionW

heISeeHim

.766

MyDrAlwaysTreatsMeWith

Respect

.634

TheStaff@MyDrOfficeVery

FlexibleInDealingWIndividu

NeedsAndDesires

.686

MyDrSOfficeStaffAlwaysAct

sInProfessionalManner

.671

MyDrExplainsALittleAboutM

yMedicalProblems

.653

MyDrIsBetterTrainedThanT

heAverageDr

.431 .520

ComparedToOtherDrsMyDr

MakesFewerMistakes

.450 .777

MyDrKeepsUpOnTheLatest

MedicalDiscoveries

.452 .789

MyDrGivesMeChoicesWhe

nDecidingMyMedicalCare

.712 .412

CRONBACH’S ALPHA

.781 .795

CUMMULATIVE PER

CENT OF VARIANCE

24.6 36.5 43.86

A principle components analysis with varimax rotation was conducted to obtain the

dimensions of medical service quality satisfaction. The Kaiser test for eigenvalues greater

than one suggests a three-factor solution which explains 38% of the variance. A factor

loading of 0.4 was used as a cut off point to eliminate variables with low correlation from

each factor and a reliability test was applied to examine the internal consistency of each

factor separately. The results show that the value of the cronbach coefficient alpha of the

first two variables were 0.781 & 0.911 respectively, indicating that there is good internal

consistency among items within each of the two medical service quality satisfaction

dimensions. However, factor 3 has no coefficient alpha since it compromises only one

variable.

Factor one is composed of the Dr.’s real interest in the patient, the Dr’s full attention to

the patient while sitting with him, and the Dr.’s offers of different choices when Medical

care is concerned. Factor two Compromises the Dr’s continuous follow up on the latest

medical technologies, and comparing to other Drs., the Patient’s Dr. is viewed to commit

fewer mistake than other Drs. While the third factor consists of the Dr.’s carefulness to

explain to the patient what is he expected to do. Table 3.

Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3

My Dr. takes real interest in

me

Compared To Other Drs My Dr

Makes Fewer Mistakes

My Dr Is Careful To Explain What

I Am Expected To Do

I have my Dr’s full

attention when I see him/her

My Dr Keeps Up On The Latest

Medical Discoveries

The Staff at my Dr’s Office are

Very Flexible In Dealing with my

Individual Needs And Desires

My Dr’s Office Staff Always Acts

In Professional Manner

My Dr Explains A Little About My

Medical Problems

My Dr Gives Me Choices When

Deciding My Medical Care

Conclusions and Implications for future research:

The employment of a modified SERVQUAL instrument had accomplished an “objective”

assessment of medical service quality. Much is learned regarding the patient-physician

relationship and encounter; (1) Physicians are spending enough time with their patients

during the encounter, (2) physicians are answering the patients’ questions honestly,

completely, and understandably, and (3) physicians are treating patients with respect and

are being friendly with them.

Findings of this study indicate that high quality medical service can be delivered by

hospitals or clinics only when those latter foster a customer oriented marketing culture

characterized by emphasis on medical service quality orientation and interpersonal

relationship. This can be assured through the following dimensions:

- Systematic, regular measurement and monitoring of nurses and Drs’ performance

- Clear focus on patients needs

- A strong linkage between the clinic staffs’ behavior and the clinic’s image

- The desire to meeting the clinic’s expectations on medical quality service

- Emphasis on communication skills

- Staffs’ attention to details in their work

- Recognition of employees invaluable assets of the firm

- Frequent interaction between Drs and front line staffs

This research gives importance to the medical service quality and its impact on patients’

satisfaction. Still, it has several implications and limitations.

- Additional research is needed on evaluating medical service quality as this study

was conducted on medical care provided by physicians and should not be

construed as representing the entire medical services.

- The focus of this research is the dyadic interaction between a single physician and

a single client, yet often the client’s time is spent interacting with support staff

and/or multiple physicians.

- SERVQUAL is designed to measure interpersonal quality only. However,

interpersonal quality cannot be sustained without accurate diagnoses and

procedures. Such technical quality should be the focus of future research.

References

Astrachan, A., (1991), “Is medicine still a profession?”, Medicine, Vol.35 pp. 43-49.

Badrick, T., (1996), “TQM and its implementation in Health Care Organizations”,

Clinical, Biomedical Revs, Vol.17, N0.5, pp.341-345

Brown, S.W., Swartz, T., (1989) “ A Gap Analysis of Professional Service Quality”,

Journal of Marketing, Vol.53, N0.4 pp.92-98.

Bryant, C., Kent, E., Lindenberger, J., Schreiher, J., (1998), “Increasing consumer

satisfaction”, Marketing Health Services, Vol.18, N0.4 pp.4-17.

Cartwright, A., “Patients and their Doctors: A Study of General Practice”, New York,

Atherton Press, 1967.

Coser, R., (1956), “A Home Away from Home”, Social Problems, Vol.4, pp.3-17.

Creswell, J., (2005), Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating

Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 2

nd

edition, Pearson Education.

Donabedian, A., (1980), The definition of Quality and Approaches to its Assessment,

vol.1: Explorations in Quality Assessment and Monitoring. Ann Arbor, Michigan, Health

Administration Press.

Donabedian, A. et al, (1988), “The Quality of Care: How can it be Assessed?”, JAMA,

Vol.260, N0.12, pp.1743-48.

Friedson, E., Patients’ Views of Medical Practice, New York, Sage Publication, 1961.

Gay, L., Mills, G., Airasian, P., 2006, Educational Research: Competencies for analysis

and applications, 8

th

edition, Pearson Education.

Gronroos, C., Strategic Management and Marketing in the Service Sector, Helsingfors,

Swedish School of Economics and Business Administration, 1982.

Gummerus, J., et al, (2004), “Customer Loyalty to content-based Web sites: the case of

an online health-care service”, Journal of Services Marketing, Vol.18, N0.3, pp.175-186.

Hair, JF., et al, (2007), Multivariate Data Analysis, Sixth edition, Pearson Education.

James, B.C., (2002), Physician and Quality improvement in Hospitals: How do you

involve Physicians in TQM?, The Journal of Quality and Participation, Vol.25, pp. 56-

63

Lewis, R., et al, “The Marketing Aspects on Services Marketing”, Quoted in Parsuraman

et al (1985), “A Conceptual Model of Service Quality and its Implications for further

Research”, Journal of Marketing, Vol.49 pp.41-50.

Malhotra, N.K., (2004), Marketing Research, Fourth edition, Pearson Education.

Parsuraman, A., et al, (1985), “A Conceptual Model of Service Quality and its

Implications for further Research”, Journal of Marketing, Vol.49 pp.41-50.

Parasuraman , A., Ziethaml,V. and Berry, L., (1988), “SERVQUAL: a multiple-item

scale for measuring consumer perceptions of SQ”, Journal of Retailing, Vol.64, N0. 1

pp.12-40

Parasuraman , A., Ziethaml,V. and Berry, L., (1994), Moving forward in service quality

research: Measuring different customer-expectations levels, comparing alternative scales

and examining the performance-behavioral intentions link. Cambridge, Massachusetts:

Marketing science institute, Report Number 94-114.

Rubin, R. et al, (1990), “Patient Judgments of Hospital Quality”, Medical Care, Vol. 28,

N0.9 pp. S51-S56

Steffen, G., (1988), “Quality of Medical Care: A Definition”, JAMA, Vol.260, N0.1 pp.

56-61.

Sussman, M. et al, (1967), The Walking Patient: A Study of Outpatient Care. Cleveland,

The Press of the Case Western Reserve University.

Synay, T., (2002), “Access to Quality Health Services: Determinants of Access”, Journal

of Health Care Finance, Vol. 28, N0.4 pp.58-68.

Tam, J.L., (2004), “Customer Satisfaction, Service Quality and Perceived Value: An

integrated Model”, Journal of Marketing Management, Iss. 7,8 September, pg.897.

Tarantino, D., (2004), “How should we measure patient satisfaction?” Physician

executive, Vol.30, N0. 4 pg. 60-61.

Ware, J. et al, (1975), “ Consumer Perceptions of Health Care Services: Implications foe

Academic Medicine”, Journal of Medical Education, Vol.50, N0.9, pp. 839-848.

Willging, P., (2004), “Customer Satisfaction Surveys are more than just Paper”, Nursing

Home, Vol. 53, N0.8 pg.20.

Zeithaml, V. et al, “Communication and Control Processes in the delivery of Service

Quality”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 52, N0.4, pp. 35-48.

Ziethaml, V. et al, Delivering Service Quality: Balancing Customer Perceptions and

Expectations, New York, The Free Press, 1990.

Appendix 1: Questionnaire used in the research:

1-Expectations

The following set of statements deal with the opinion of a patient to medical services.

The patient will show the extent to which he thinks Clinics or Hospitals offering medical

services should possess the features described in each statement.

There is no right or wrong answer; the interest is in the number that best shows the

expectations about organizations offering medical services.

(1) Strongly disagree

(2) Disagree

(3) Neither agree nor disagree

(4) Agree

(5) Strongly agree

□ Appointments should be made easily and quickly.

□ I expect the medical service’s fees to be reasonable for the professional service

rendered.

□ I expect my doctor to keep up on the latest medical technologies.

□ I expect my doctor (or nurse) to be sincerely interested in me as a person.

□ I expect my doctor to examine me carefully before deciding what is wrong.

□ I expect my doctor to explain tests and procedures to me.

□ I would like to have more health-related information available in the reception area.

□ I would like to have brochures available from my doctor explaining my medical

problem and treatment.

□ I expect the doctor’s office to be open at times that are convenient to my schedule.

□ I expect the doctor to be available in an emergency.

□ Where my medical care is concerned, my doctor should make all decisions.

2-Experiences

The following statements relate to the feelings about the medical services delivered

(mainly related to the Physician). The patient will show the extent to which he believes

medical services have the feature described by the statement.

There is no right or wrong answer; the interest is in the number that best shows the

perception about medical services.

(1) Strongly disagree

(2) Disagree

(3) Neither agree nor disagree

(4) Agree

(5) Strongly agree

□ My doctor hears what I have to say.

□ My doctor gives me enough information about my health.

□ My doctor gives me brochures explaining my medical problem and treatment.

□ My doctor is careful to explain what I am expected to do.

□ My doctor is extremely attentive to details.

□ My doctor spends enough time with me.

□ My doctor examines me carefully before deciding what is wrong.

□ I have complete trust in my doctor.

□ My doctor takes real interest in me.

□ I have my doctor’s full attention when I see him/her.

□ My doctor always treats me with respect.

□ My doctor thoroughly explains to me the reasons for the tests and procedures that are

done on me.

□ My doctor’s staff is friendly and courteous.

□ The staff at my doctor’s office is very flexible in dealing with my individual needs

and desires.

□ My doctor’s office staff always acts in a professional manner.

□ My doctor’s staff is more interested in serving the doctor than meeting my needs.

□ My doctor prescribes many drugs and pills.

□ My doctor orders too many tests.

□ My doctor takes unnecessary risks in treating me.

□ My doctor’s main interest is in making as much money as he/she can.

□ My doctor and staff talk as if I am not even there.

□ My doctor does not admit when he or she does not know what is wrong with me.

□ There are some things about the medical care I receive from my doctor that could be

better.

□ My doctor explains a little about my medical problems.

□ My doctor is better trained than the average doctor.

□ Compared to other doctors, my doctor makes fewer mistakes.

□ My doctor keeps up on the latest medical discoveries.

□ My doctor gives me choices when deciding my medical care.

□ My doctor is present during his/her clinic hours.

□ I am kept waiting a long time when I am at my doctor’s office.

□ My doctor’s office is conveniently located for me.

□ My doctor is on staff at a hospital which is convenient for me.