July 2020

SDN/20/05

I M F S T A F F D I S C

U S S I O N N O T

E

Dominant Currencies and

External Adjustment

Gustavo Adler, Camila Casas, Luis Cubeddu,

Gita Gopinath, Nan Li, Sergii Meleshchuk,

Carolina Osorio Buitron, Damien Puy, and

Yannick Timmer

DISCLAIMER: Staff Discussion Notes (SDNs) showcase policy-related analysis and research being

developed by IMF staff members and are published to elicit comments and to encourage debate.

The views expressed in Staff Discussion Notes are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily

represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.

DOMINANT CURRENCIES AND EXTERNAL ADJUSTMENT

2 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Dominant Currencies and External Adjustment

Research Department

1

Prepared by Gustavo Adler, Camila Casas, Luis Cubeddu, Gita Gopinath,

Nan Li, Sergii Meleshchuk, Carolina Osorio Buitron, Damien Puy, and Yannick Timmer

Authorized for distribution by Gita Gopinath

DISCLAIMER: Staff Discussion Notes (SDNs) showcase policy-related analysis and research

being developed by IMF staff members and are published to elicit comments and to encourage

debate. The views expressed in Staff Discussion Notes are those of the author(s) and do not

necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.

JEL Classification Numbers: E58, F31, F32.

Keywords:

trade pricing, trade invoicing, exchange rate, external

adjustment

Authors’ E-mail Addresses:

gadler@imf.org; ggopinath@imf.org;

cosoriobuitron@imf.org

1

This note benefited from invaluable feedback and input from Adolfo Barajas, Tam Bayoumi, Emine Boz, Federico

Diez, Sebnem Kalemli-Ozcan, Francois de Soyres, Antonio Spilimbergo, Leonardo Villar, and various participants at the

2019 IMF Workshop on “Tariffs, Currencies and External Rebalancing” (Washington, DC). Our colleagues, Fadhila

Alfaraj, Bas Bakker, Jennifer Beckman, Houda Berrada, Helge Berger, Eugenio Cerutti, Alfredo Cuevas, Mai Dao, Fei

Han, Olamide Harrison, Michelle Hassine, Venkat Josyula, Huidan Lin, Meera Louis, Charlotte Lundgren, Begona

Nunes, Mahvash Qureshi, Natalie Ramirez, Christoph Rosenberg, Edgardo Ruggiero, Carlos Sanchez-Munoz, Alasdair

Scott, Silvia Sgherri, Niamh Sheridan, Nico Valckx, and Yuanyan Sophia Zhang contributed with insightful comments.

Jair Rodriguez, Kyun Suk Chang, and Zijiao Wang provided excellent research support.

DOMINANT CURRENCIES AND EXTERNAL ADJUSTMENT

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 3

CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY __________________________________________________________________________ 5

INTRODUCTION _________________________________________________________________________________ 6

DOMINANT CURRENCY PRICING _______________________________________________________________ 6

A. Key Concepts __________________________________________________________________________________ 6

B. Evidence from Manufacturing Trade ___________________________________________________________ 8

C. Evidence from Services Trade _________________________________________________________________ 14

DOMINANT CURRENCY FINANCING __________________________________________________________ 18

A. Key Concepts _________________________________________________________________________________ 18

B. Macro Evidence _______________________________________________________________________________ 19

C. Micro-level Evidence __________________________________________________________________________ 22

KEY TAKEAWAYS AND FUTURE WORK ________________________________________________________ 24

BOXES

1. Factors Behind Firms' Pricing Currency Choices ________________________________________________ 8

2. Data on Trade Invoicing Currencies ____________________________________________________________ 9

3. Constructing Foreign Currency Debt Exposure Measures for NonFinancial Firms ______________ 21

FIGURES

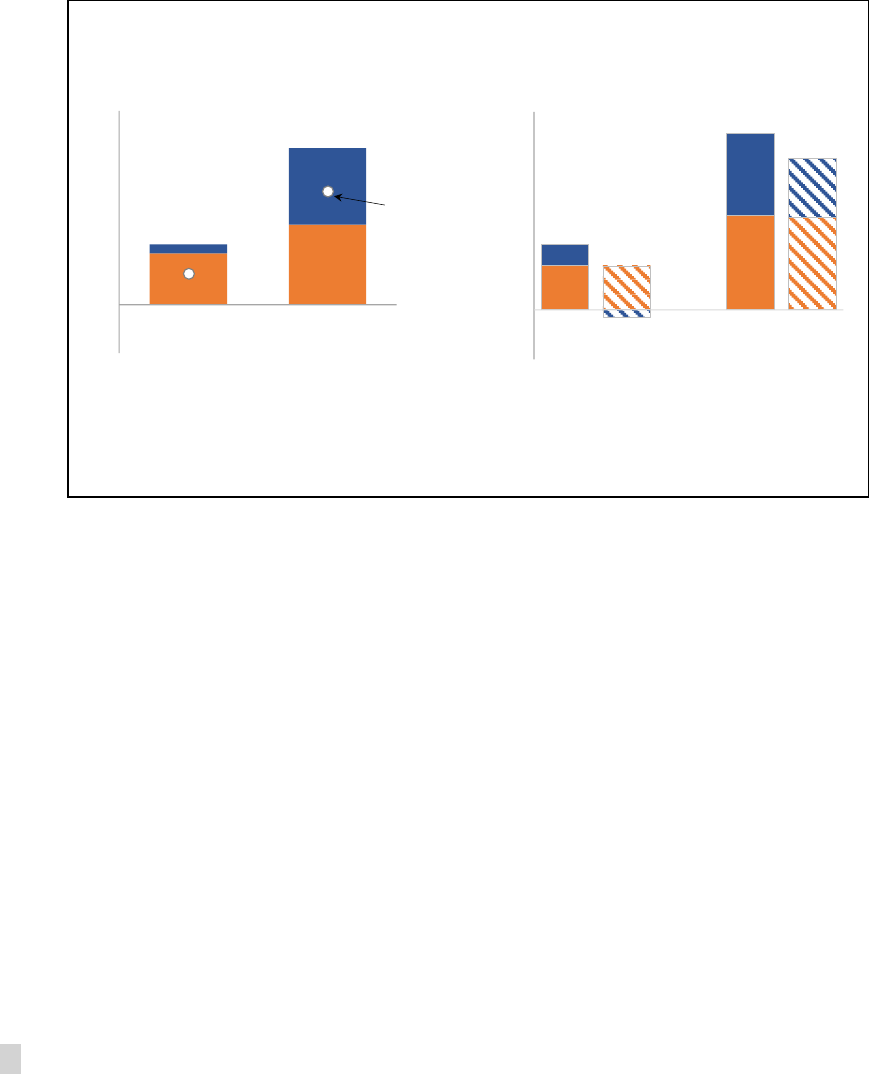

1. Trade with the United States and US Dollar Invoicing __________________________________________ 9

2. Export Invoicing Currencies ___________________________________________________________________ 10

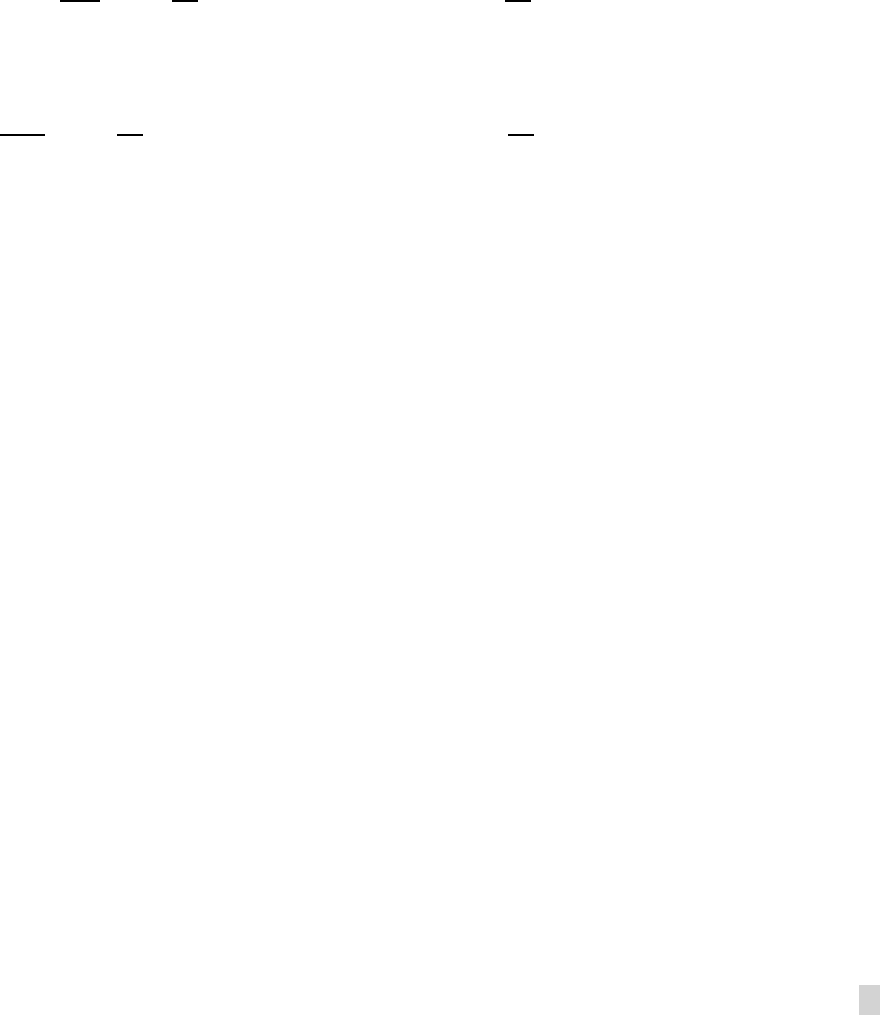

3. Empirical Framework __________________________________________________________________________ 11

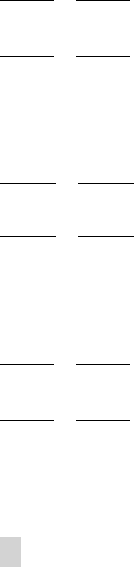

4. Exchange Rate Pass-through from Bilateral and US Dollar Exchange Rate _____________________ 12

5. Trade Volume Responses to Bilateral and US Dollar Exchange Rates _________________________ 13

6. Contribution of Trade Volumes to External Rebalancing ______________________________________ 14

7. Global Trade in Goods and Services ___________________________________________________________ 15

8. Services Trade Value Elasticities to Bilateral and US Dollar Exchange Rates ____________________ 17

9. Tourism Volume Elasticities to Bilateral and US Dollar Exchange Rates ________________________ 18

10. Foreign Currency Borrowing in the NonFinancial Corporate Sector __________________________ 20

11. Foreign Currency Exposures in the NonFinancial Corporate Sector, by Instrument ___________ 20

12. Short-term Trade Volume Elasticities _________________________________________________________ 22

13. Effect of Foreign Currency Leverage on Firms' Trade Flows and Borrowing __________________ 23

14. Financial Channel of Exchange Rate: Evidence from Colombia _______________________________ 23

DOMINANT CURRENCIES AND EXTERNAL ADJUSTMENT

4 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

TABLES

1. Expected Effects of a Depreciation on Trade Volumes _________________________________________ 18

APPENDICES

1. Dominant Currency Pricing ____________________________________________________________________ 26

2. Measuring FX Debt Exposure in the Non-Financial Corporate Sector __________________________ 36

3. The Financial Channel of Exchange Rates—Macro Empirical Specification and Data___________ 37

APPENDIX TABLES

A1.1. Currency of Invoicing—Baseline Specification ______________________________________________ 31

A1.2. Currency of Invoicing—Unweighted Regression ___________________________________________ 32

A1.3. Currency of Invoicing—Direct Evidence ____________________________________________________ 35

A3.1. Baseline (unweighted) ______________________________________________________________________ 42

A3.2. Weighted Regressions _____________________________________________________________________ 42

A3.3. Estimates by USD invoicing share __________________________________________________________ 43

References ______________________________________________________________________________________ 44

DOMINANT CURRENCIES AND EXTERNAL ADJUSTMENT

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 5

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The extensive use of the US dollar when firms set prices for international trade (dubbed dominant currency pricing)

and in their funding (dominant currency financing) has come to the forefront of policy debate, raising questions

about how exchange rates work and the benefits of exchange rate flexibility. This Staff Discussion Note documents

these features of international trade and finance and explores their implications for how exchange rates can help

external rebalancing and buffer macroeconomic shocks.

Dominant currency pricing: Unlike under the traditional model, in which trade prices are set in the exporter’s

currency, the US dollar plays a dominant role in trade pricing, especially in emerging market and developing

economies. This alters how trade flows respond to a country’s exchange rate movements, especially in the short

term, dampening the reaction of export volumes. It implies also that a generalized strengthening of the US dollar

entails short-term contractionary effects on trade among countries other than US, with accompanying negative

impact on economic activity. Dominant currency pricing appears to be common both in goods and in services trade,

although it is less prevalent in the latter—especially in some sectors, like tourism. Thus, cross-country differences in

services versus manufacturing specialization may account for varying responses to exchange rates. The traditional

exchange rate effects through both export and import volumes gradually reemerge over time as prices become

more flexible, especially in larger economies, where US dollar pricing is less prevalent.

Dominant currency financing: Firms, especially in emerging market economies, often rely on US dollar funding.

Consequently, exchange rate fluctuations can impact trade flows through their effect on firms’ balance sheets,

although these effects depend on both the prevailing pricing and financing currencies. Where the US dollar is used

for both pricing and financing, exporting firms are naturally ”hedged,” and the financial channel is immaterial.

Revenues and liabilities of importing firms, however, are not matched, and exchange rate fluctuations bring about

balance sheet effects that reinforce the adjustment through import volumes.

Overall, where dominant currency pricing and financing are widespread, the short-term response of trade volumes

to exchange rates is likely to be more muted and to be manifested mostly through imports. Thus, the analysis

indicates that buffering the domestic economy from macroeconomic shocks or rebalancing external positions will

generally require larger exchange rate movements and may justify supportive macroeconomic policies when large

exchange rate fluctuations carry adverse side effects—although the design of specific policies is beyond the scope of

this note. Exchange rate flexibility remains a key mechanism to facilitate durable, medium-term external adjustment.

Pricing and financing currencies jointly determine the strength of exchange rate effects, and these features seem to

vary across countries and time. Thus, a granular picture of both is of the essence to gain a deeper understanding of

the determinants and implications of currency choices, as well as to assess the merits of exchange rate flexibility.

Tackling data gaps on pricing and financing currencies is paramount to make progress on this front.

For the ongoing COVID crisis, the dominance of the US dollar implies that the observed weakening of emerging and

developing countries’ currencies is unlikely to provide material boost to their economies in the short term as the

response of goods exports will be muted while some sectors that would normally respond more to exchange

rates—like tourism—are likely to be impaired by COVID-related containment measures and consumer behavior

changes. Moreover, the generalized strengthening of the US dollar may magnify the short-term fall in global trade

and economic activity as both higher domestic prices of traded goods and services and negative balance sheet

effects on importing firms contribute to lower demand for imports throughout the emerging and developing world.

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 6

INTRODUCTION

1. There is ongoing debate about the role of exchange rates in facilitating external

rebalancing and buffering macroeconomic shocks as countries become more integrated in trade

and finance. Some specific features of international trade and their role in shaping the effect of exchange

rate movements have received renewed attention. The currency of trade pricing and, in particular, the role

of third-country currencies (that is, currencies of countries not involved in the bilateral trade transactions)

is one area of interest. This phenomenon, dubbed dominant currency pricing, entails a departure from the

traditional Mundell-Fleming framework (in which prices are thought to be “sticky” in the exporter’s

currency) and can have material consequences for how trade volumes respond to exchange rate

movements. Questions have also arisen about the impact of exchange rates on trade flows when

importing and exporting firms finance their operations in currencies other than their domestic currency

(dominant currency financing), because movements in exchange rates result in balance sheet effects, with

implications for their activities and trade flows. Building on previous research and new empirical work, this

Staff Discussion Note explores how these two features of international trade and finance shape the way

exchange rates work to facilitate external rebalancing. Although dominant currency pricing and dominant

currency financing are closely linked—and can be driven by the same underlying factors—for expositional

purposes, they are discussed separately below. Similarly, the analysis takes these features as given, leaving

aside the determinants—which are discussed as an area for future work.

2. The note is organized as follows: The next section documents the extent of dominant currency

pricing and its implications for how trade flows respond to exchange rate movements, exploring both

manufacturing and services trade. A discussion of the implications of dominant currency financing follows,

including in connection with dominant currency pricing, and provides empirical evidence based on macro-

and firm-level data. The concluding section discusses the key takeaways, implications (including for the

ongoing global COVID-19 crisis), and areas for future work. Details on the new empirical analysis can be

found in the technical appendices and referenced working papers.

DOMINANT CURRENCY PRICING

A. Key Concepts

3. Exchange rates can play an important role in external adjustment. Fluctuations in exchange

rates can induce changes in the relative prices of foreign and domestic goods, thus leading to changes in

demand and supply and, hence, in export and import quantities. This is a key mechanism to close a

country’s external current account imbalances. Exchange rates can also play an essential role in buffering

macroeconomic shocks. For example, when domestic demand is weak, depreciation of the domestic

currency can help stimulate the local economy by boosting exports and inducing import substitution.

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 7

4. How trade flows respond to exchange rate movements, however, depends on whether

trade prices are sticky and, if so, on the currency in which prices are set (see Box 1).

2,3

• When prices are sticky in the currency of the producer (producer currency pricing), as understood

under the Mundell-Fleming framework, depreciation of a country’s currency (via-à-vis all other

currencies) increases the price of imports in the home currency in the short term and, thus, reduces

domestic demand for foreign goods (imports).

4

The depreciation also reduces the price of exports in

the destination currency in the destination markets and, thus, leads to an increase in foreign demand

for domestic goods (exports). That is, exchange rates induce expenditure switching—a switch between

foreign and domestic goods—and the associated external rebalancing through both exports and

imports. Expenditure switching through exports and imports also implies that the exchange rate plays

a buffering role against macroeconomic shocks. A depreciation as a result of a negative

macroeconomic shock, for example, helps stimulate the domestic economy by boosting exports and

inducing import substitution.

• When prices are set in a third country’s currency, regardless of the origin or destination of trade flows

(“dominant currency pricing,” as proposed by Gopinath and others, 2020), depreciation leads to an

increase in import prices in the short term, as under producer currency pricing, inducing the same

import compression. However, prices faced by trading partners do not move because their exchange

rates vis-à-vis the dominant currency have not changed. Thus, foreign demand remains unchanged,

and so do exports. Although a country’s currency depreciation leads to a decrease in imports from all

countries, the response of export volumes is muted under dominant currency pricing. A dominant

currency in trade pricing implies a weaker exchange rate mechanism of external rebalancing through

trade volumes in the short term. It also means the buffering role of exchange rates is weaker, since

exports provide less countercyclical support to the economy.

2

If prices are fully flexible, the invoicing currency has no bearing on trade outcomes, as firms can adjust prices in any

currency and achieve their desired quantities, prices, and markup over costs (profit margin). Thus, invoicing and

pricing aspects are relevant only under price stickiness. In the case of commodities, prices are determined mainly in

global markets and given to individual firms. Thus, commodity trade is not subject to the mechanisms explored in this

note. See also Gopinath (2015), Gopinath and Rigobon (2008), Gopinath, Itskhoki and Rigobon (2010), and Boz,

Gopinath, and Plagborg-Møller (2018).

3

The currency of invoicing does not necessarily correspond to the currency in which prices are denominated.

However, in practice, prices are generally denominated in the currency of invoicing (see Friberg and Wilander 2008).

Thus, the terms currency of “pricing” and of “invoicing” are used interchangeably in this discussion.

4

See Betts and Devereux (2000) and Devereux and Engel (2003) for discussion of the “local currency pricing” case.

DOMINANT CURRENCIES AND EXTERNAL ADJUSTMENT

8 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Box 1. Factors Behind Firms’ Pricing Currency Choices

Firms can choose to invoice their foreign sales in their own currency, the currency of the destination market, or a

third “dominant” currency,

1

and several related factors play a role in their choice:

2

• Strategic complementarities in pricing: In many cases, it is optimal for a firm to keep the price of its products as

close as possible to those of its competitors. By pricing in the same currency as its competitors a firm can avoid

unwanted fluctuations in the price of its goods relative to those of its competitors. In international markets,

this may mean choosing a currency other than the producer’s or the consumer’s. This is especially relevant for

countries whose market share is particularly sensitive to changes in their price relative to competitors’ prices.

• Returns to scale: Firms facing decreasing returns to scale (as a result of the fixed nature of capital or other

sources of capacity constraint) have less incentive to change their prices in US dollars. For example, a

depreciation of their home currency would typically increase firms’ markups (profit margins), potentially

allowing these firms to lower US dollar prices to gain market share. However, if they face capacity constraints,

increasing production may not be feasible and, thus, firms would have no incentive to adjust their prices.

• Imported intermediate inputs: Exporters seek to match the currency of their revenues and production costs. If a

firm uses imported inputs in production, pricing sales of goods and services in the same currency as

production inputs achieves this match (see Gopinath and others, 2020).

3

_____________

1

See also Goldberg and Tille (2008), Goldberg and Hellerstein (2008), Gopinath (2015), and Mukhin (2018) for a fuller

discussion.

2

Some authors refer to these as “vehicle” currencies.

3

Adler, Meleshchuk and Osorio Buitron (2019) show that US dollar pricing is linked to the use of imported intermediate

goods (and participation in global value chains) but also that additional factors come into play.

B. Evidence from Manufacturing Trade

5. The US dollar dominates in trade invoicing, especially across emerging market economies.

While data on trade invoicing currencies are scant and scattered (see Box 2), available information

indicates that the US dollar plays a dominant role. A significant share of bilateral trade between countries

other than the United States is invoiced in US dollars (Figure 1). This pattern is particularly marked in

emerging market and developing economies, although it is also relevant for some advanced economies

(for example, Australia, Japan, Korea). The euro is used widely, but primarily in trade that includes euro

area economies on one or both sides of the transaction.

5

Similarly, partial data indicate that invoicing in

other major currencies (for example, British pounds, yen, Swiss francs) is significant, although mainly in

cross-border transactions involving the economies that issue those currencies.

5

See also Boz, Gopinath, and Plagborg-Møller (2018).

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 9

Figure 1. Trade with the United States and US Dollar Invoicing

Sources: Boz and others (2020).

Box 2. Data on Trade Invoicing Currencies

Granular information on trade invoicing currencies is key to understand the mechanisms of external adjustment

and, thus, to design optimal policies. However, publicly available data are scant. Many countries do not collect such

data, and others collect them but do not make them publicly available. When available, data are usually compiled

at aggregate level, with limited breakdown by trading partner or by products, or at the transaction or the firm level.

In an effort to fill this gap, a joint project by the International Monetary Fund and the European Central Bank has

gathered data from national authorities to assemble and publish a panel dataset of trade invoicing currencies (see

associated working paper by Boz et al., 2020). The data set provides the shares of exports and imports invoiced in

US dollars, euros, home currency and other currencies separately at the annual frequency over the period 1990-

2019 for over 100 countries. The dataset encompasses about 75 percent of global trade and a diverse set of

economies, representing all continents and both advanced and emerging market and developing economies.

Although the publication of this dataset is an important step, greater efforts from national authorities are needed

to broaden the coverage and, especially, increase the granularity of the data (e.g., regarding invoicing currencies in

bilateral trade, or invoicing currencies by sector/products).

6. Although the prevalence of US dollar invoicing varies across countries, it has been fairly

stable over time (Figure 2). Invoicing data show that the US dollar has played a clearly dominant role in

invoicing of both exports and imports in Asian and Latin American emerging market and developing

economies, with very stable shares in total invoicing over the past two decades. With somewhat lower

shares, the prevalence of the US dollar in some advanced economies (for example, Australia, Japan and

New Zealand) has also been quite stable. The exceptions to this pattern are mainly in countries that trade

heavily with the euro area such as non-euro European and Northern African countries or some countries

in Sub-Saharan Africa who use the euro as a vehicle currency (West African Economic and Monetary

Union) and where there was a visible increase in the use of this currency following its inception.

1. Exports to the US and Invoiced in US Dollars

(percent, 2009-19 average)

0

20

40

60

80

100

0 20

40 60 80 100

Exports Invoiced in US Dollars

Exports to the United States

Emerging Market and

Developing Economies

Euro Area Economies

Other Advanced Economies

45

degree

line

2. Imports from the US and Invoiced in US Dollars

(percent, 2009-19 average)

0

20

40

60

80

100

0 20 40 60 80 100

Imports Invoiced in US Dollars

Imports from the United States

DOMINANT CURRENCIES AND EXTERNAL ADJUSTMENT

10 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Correspondingly, the role of the US dollar appears to have remained largely unscathed since the inception

of the euro.

6

Figure 2. Export Invoicing Currencies

(US dollar, euro, and home currency, percent of total exports)

Source: Boz and others (2020) and IMF staff calculations.

Note: Each panel depicts the cross-country average invoicing shares of total exports. For the Euro Area, exports

include intra-EA exports. See Boz et al. 2020 for details on how invoicing shares are calculated. Discrete changes in

shares for Sub-Saharan Africa and Pacific regions reflect changes in country coverage over time.

7. The implications of dominant currency pricing can be explored by studying the response of

bilateral trade flows to various exchange rates. Using a novel data set of prices and quantities of

bilateral manufacturing trade,

7

and building on Boz and others (2020), the role of the US dollar is studied

by estimating exchange rate pass-through (that is, how export and import prices in domestic currency

respond to exchange rate movements) and volume elasticities (how trade volumes react to exchange

6

See Gopinath and others (2020) and Boz, Cerutti and Pugacheva (forthcoming).

7

The sample comprises 37 advanced and emerging market economies during 1990–2014. See further details in

Appendix 1.

0

20

40

60

80

100

1999 2004 2009 2014 2019

Euro Area

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

1999 2004 2009 2014 2019

Non-Euro Europe

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

1999 2004 2009 2014 2019

Japan

Home EUR

USD

0

20

40

60

80

100

1999 2004 2009 2014 2019

Latin America

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

1999 2004 2009 2014 2019

North Africa

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

1999 2004 2009

2014

2019

Sub-Saharan Africa

0

20

40

60

80

100

1999 2004 2009 2014 2019

Central Asia

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

1999 2004 2009 2014 2019

East and Southeast Asia

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

1999 2004 2009 2014 2019

Pacific

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 11

rates) vis-à-vis the US dollar and the bilateral exchange rate, both for contemporaneous and medium-

term effects. The time dimension of the effects is of the essence as the stickiness of trade prices—and,

thus, the relevance of pricing currencies—is likely to decrease over time.

Figure 3. Empirical Framework

Source: IMF staff.

Note: See Appendix 1 for further details on the methodology. ERPT = exchange rate pass-through.

8. The high pass-through from the US dollar exchange rate to domestic currency prices points

to the dominance of US dollar pricing. Trade-weighted regressions (that give more weight to

observations from larger economies) point to estimates of pass-through from the US dollar exchange rate

that are positive and statistically significant even after controlling for bilateral exchange rate movements

(Figure 4, panels 1 & 2). This indicates that the US dollar is used in the pricing of bilateral trade between

country pairs that do not include the United States.

8

This pattern is visible both for export and import

prices. Moreover, the evidence of US dollar dominance is more pronounced in the unweighted

regressions (which give equal weight to smaller economies), pointing to greater prevalence of US dollar

invoicing in emerging market and developing economies (Figure 4, panels 3 & 4). As US dollar prices start

to adjust over the medium term, the role of the US dollar diminishes, while the role of the bilateral

exchange rate increases for large economies. For smaller economies, US dollar dominance seems to have

longer-lived effects

.

9

8

Moreover, the short-term pass-through from the US dollar exchange rate is higher than from the bilateral exchange

rate, indicating that the share of bilateral trade priced in US dollars is larger than those of trade priced in the currency

of the producer or the destination country.

9

Using available information on invoicing currencies for a subsample of countries and years allows more direct

exploration of the role of the US dollar by comparing pass-through estimates for cases of low and high US dollar

invoicing. Results corroborate that the high pass-through from the US dollar exchange rate relates to the degree of

US dollar invoicing. See Appendix 1.

Bilateral Trade

Prices / Volumes

Bilateral Exchange Rate

Exchange Rate vis-à-vis US Dollar

Controls for Bilateral and Global Demand/Supply shocks

Short-term (same year of shock) and medium

-term (3 years after) effects

Trade balance

Trade openness

ERPT and Volume elasticities

DOMINANT CURRENCIES AND EXTERNAL ADJUSTMENT

12 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Figure 4. Exchange Rate Pass-through from Bilateral and US Dollar Exchange Rate

Sources: Boz, Cerutti and Pugacheva (forthcoming); Gopinath and others (2020); IMF (2019); and IMF staff

estimations.

Note: The upper panels depict trade-weighted regressions, while the lower panels depict unweighted

regressions.

9. Dominant currency pricing also shapes the response of trade volumes to exchange rate

movements. Estimates of volume elasticities indicate that movements in the bilateral exchange rate

produce the traditional response of trade volumes (Figure 5, panels 1 & 2). That is, a bilateral depreciation

vis-à-vis the currency of the trading partner leads to a boost in export volumes to and a fall in import

volumes from such trading partner. This is not the case for a depreciation vis-à-vis the US dollar, which

highlights the key implication from US dollar pricing. Specifically, a depreciation vis-à-vis the US dollar

only—that is, with unchanged bilateral exchange rates vis-à-vis other currencies—is associated with a

contraction in both exports to and imports from trading partners (other than the United States). This is

because, when trade is invoiced largely in US dollars and the US dollar appreciates (that is, all other

currencies depreciate), all countries other than the United States face a higher domestic currency price for

their imports, causing lower demand for them and correspondingly less trade with other economies.

Consistent with the pattern for prices, these effects on volumes are more pronounced in the unweighted

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

Bilateral

US$ Bilateral US$

Short term Medium term

1. Export Prices

US dollar

dominance

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

Bilateral US$ Bilateral US$

Short term Medium term

2. Import Prices

A. Weighted regressions (more representative of larger economies)

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

Bilateral US$ Bilateral US$

Short term Medium term

3. Export Prices

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

Bilateral US$ Bilateral US$

Short term Medium term

4. Import Prices

B. Unweighted regressions (more representative of smaller economies)

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 13

regressions, especially over the medium term—again highlighting the higher prevalence of US dollar

invoicing and the associated effect on volume responses in smaller economies (Figure 5,

panels 3 & 4). As US dollar prices gradually adjust over the medium term, the relevance of the US dollar in

driving trade volumes diminishes in the case of larger economies, while the effects are more persistent in

smaller economies.

Figure 5. Trade Volume Responses to Bilateral and US Dollar Exchange Rates 1/

(Percent)

Sources: Boz, Cerutti and Pugacheva (forthcoming); Gopinath and others (2020); IMF (2019); and IMF staff

estimations.

Note: The upper panels depict trade-weighted regressions, while the lower panels depict unweighted

regressions.

10. Thus, dominant currency pricing weakens the mechanism of external rebalancing through

trade volumes and limits the buffering role of exchange rates. In the short term, a depreciation of a

country’s currency vis-à-vis all others—the relevant thought experiment to assess the role of exchange

rates in external rebalancing—entails a contraction in import volumes, reflecting the standard expenditure

switching mechanism through imports. Export volumes, however, show a muted response as trading

-0.6

-0.4

-0.2

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

Bilateral US$ Bilateral US$

Short term Medium term

1. Export Volumes

-0.8

-0.6

-0.4

-0.2

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

Bilateral US$ Bilateral US$

Short term Medium term

2. Import Volumes

A. Weighted regressions (more representative of larger economies)

B. Unweighted regressions (more representative of smaller economies)

-0.6

-0.4

-0.2

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

Bilateral US$ Bilateral US$

Short term Medium term

3. Export Volumes

-0.6

-0.4

-0.2

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

Bilateral US$ Bilateral US$

Short term Medium term

4. Import Volumes

DOMINANT CURRENCIES AND EXTERNAL ADJUSTMENT

14 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

partners continue to face the same US dollar price and, thus, do not change the quantities demanded

from the depreciating country. That is, in the short term, external rebalancing takes place primarily

through imports (Figure 6, panel 1). The muted response of export volumes to exchange rates also implies

that the short-term buffering effects of exchange rate

flexibility are limited. Over the medium term, the

expenditure switching mechanism through exports gradually reemerges, increasing the overall response

of the trade balance to exchange rate movements. Evidence using available currency invoicing data

corroborates the impact of dominant currency pricing on the external adjustment process (Figure 6,

panel 2).

Figure 6. Contribution of Trade Volumes to External Rebalancing 1/

(Response to 10 percent depreciation vis-à-vis all other currencies, percent of GDP)

Sources: Boz, Cerutti and Pugacheva (forthcoming); Boz and others (2020); Gopinath and others (2020); IMF (2019); and IMF

staff estimations.

1/ Estimated effect of a 10 percent depreciation vis-à-vis all other currencies for a country with a median degree of trade

openness. “Short term” and “medium term” refer to the impact in the same year as the shock and the cumulative impact three

years later, respectively.

11. Another implication of US dollar invoicing is that an appreciation (depreciation) of the US

dollar vis-à-vis all other currencies entails a contractionary (expansionary) effect on global trade

and economic activity.

This is because, when trade is invoiced in US dollars and the US dollar

appreciates (that is, all other currencies depreciate vis-à-vis the US dollar), all countries other than the

United States face a higher domestic currency price for their imports, causing lower demand for them and

correspondingly less trade with other economies. This has a contractionary effect on global economic

activity.

C. Evidence from Services Trade

The dominance of the US dollar is a significant factor in manufacturing trade. Is it equally important in

services trade? With growing services trade and increased country specialization, pricing of services trade

plays an ever more important role in the mechanics of exchange rates.

12. Services trade is growing fast and is leading to specialization (Figure 7). While goods still

account for the bulk of cross-border trade, services trade has expanded three times faster over the past

-0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

Short term Medium term

Export volumes

Import volumes

Total effect on

trade balance

(includes prices)

-0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

1 2 3 4 5

Low

USD inv.

High

Short term Medium term

Exports

Imports

Low

High

1. Average

2. By degree of USD invoicing

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 15

decade and now accounts for a 25 percent of global trade in gross terms and 40 percent in value-added

terms. The global rise of services trade has brought with it greater specialization in services exports by

advanced economies, while emerging market and developing economies are increasingly specialized in

manufacturing exports. This is why understanding the impact of exchange rates on services trade is

increasingly crucial for a full picture of the process of external adjustment. Moreover, traded services

include a diverse set of activities, such as transportation, tourism, financial services, communication

services, royalty and license fees, and artistic exchange—with potentially very different characteristics that

affect pricing decisions.

Figure 7. Global Trade in Goods and Services

Sources: World Bank, World Development Indicators; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: Panel 1 shows the value of global exports in goods and services, normalized by the level in 1985. Panel 2 shows the time

series of the ratio of the GDP-weighted average of manufacturing exports to services exports for advanced economies and for

emerging market and developing economies, respectively.

13. Various factors that distinguish services from manufacturing can lead to different pricing:

• Use of domestic inputs: In contrast to manufacturing, where production often requires imported

intermediate inputs (priced in foreign currency), services generally employ a high share of domestic

labor and a low share of imported intermediate inputs.

10

This higher intensity of domestic inputs

means lower sensitivity of production costs to exchange rate movements and, hence, greater

incentives to price in the currency of the service producer (that is, producer currency pricing).

• Barriers to entry and market power: Services are characterized by greater natural and policy barriers to

entry (for example, regulatory requirements in telecommunications, insurance, professional services)

and network externalities (for example, telecommunications, financial services, transportation).

11

These

10

World Input-Output data indicate that the average share of intermediate inputs in gross manufacturing output was

26.7 percent in 2016, compared with 8.7 percent for services. Similarly, the average share of labor input was 27.9

percent for manufacturing, compared with 57.5 percent for services. See also Bernad and others (2009), Kugler and

Verhoogen (2009), and Manova and Zhang (2009).

11

See Francois and Hoekman (2010) and Hoekman and Shephed (2019).

(continued)

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015

Index, 1985=1

Services Exports

Goods Exports

1. Global Exports 2. Merchandise-to-Services Export Ratios

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015

Advanced Economies

Emerging Markets and Developing

Economies

DOMINANT CURRENCIES AND EXTERNAL ADJUSTMENT

16 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

factors tend to contribute greater market power and the associated incentives to price in local

currency to ensure stable market shares that maximize profits.

12

• Proximity Burden: In general, services cannot be stored, so their exchange often requires proximity

between the supplier and the consumer (“proximity burden”). Firms’ strategic currency choice, thus,

depends on the pricing of their competitors at the location of service delivery. When service exporters

compete with local providers in the customer’s location, they tend to price in local currency. When

trade takes place at the exporter’s location and the exporter competes mainly with domestic providers

(for example, tourism), the proximity burden leads to pricing in the producer currency.

14. Evidence points to an important role of the US dollar in services as well, although arguably

with lower prevalence than in manufacturing.

Data limitations significantly constrain analysis of

exchange rate effects through services trade since there are no bilateral price and quantity data for most

services sectors. Data on invoicing currencies for services are also virtually nonexistent. However, using a

newly available Trade in Services Database

13

on values of bilateral trade services and employing a similar

estimation strategy as for manufacturing indicates that both the bilateral and US dollar exchange rates

affect bilateral trade flows (Figure 8). This points to significant shares of service trade being invoiced in the

exporter’s currency as well as in US dollars. The relative magnitude of these elasticities suggests a lower

prevalence of dominant currency pricing (relative to producer currency pricing) in services than in

manufacturing, although this can be interpreted only as suggestive evidence.

14,15

The effect of the

bilateral exchange rate, however, strengthens over the medium term, whereas the effect of the US dollar

exchange rate declines. Similar patterns are visible for regressions that give greater weight to larger

economies.

12

See Amiti, Itskhoki, and Konings (2014, 2018).

13

See Francois and Pindyuk (2013) for methodological detail of the data construction. The data set reconciles and

consolidates data from multiple sources, including the WTO-UNCTAD-ITC services trade database (the primary

source), Eurostat, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and IMF data. It covers 11 one-

digit-level services industries in more than 200 countries for over 4,000 country pairs during 1995–2017.

14

Without data on prices, inferring the pricing currency requires making assumptions about the price sensitivity of

demand. If the latter does not depend on the pricing currency, or vice versa, estimated value elasticities offer

information about the underlying prevalence of producer versus US dollar pricing. The validity of the assumption is,

however, unclear since one of the factors affecting firms’ invoicing currency decisions may be the price elasticity of

demand.

15

Compared with manufacturing goods, services prices also appear to be more rigid, possibly reflecting less volatile

consumer demand for them (Bils and Klenow 2004; Klenow and Malin 2010).

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 17

Figure 8. Services Trade Value Elasticities to Bilateral and US Dollar Exchange Rates

Source: Li and Meleshchuk (forthcoming).

Note. SR (MR) denotes short and medium run, corresponding to the effect in the same year of the shock

and the cumulative effect three years later, respectively. 95 percent confidence bands are reported.

15. The prevalence of US dollar pricing seems to vary significantly across service sectors, with a

significantly weaker role in some sectors, such as tourism. There is evidence of significant differences

across sectors. In the short term, the US dollar exchange rate seems to be more important than bilateral

exchange rates in sectors such as transportation, travel, telecommunications, computer services, and

information technology. In contrast, the US dollar exchange rate does not play a significant role in

financial services and other business services. This variation may reflect the underlying differences in

industry-specific characteristics, including how frequently prices are adjusted, their reliance on imported

intermediate inputs, and their market concentration. Data on quantities for tourism flows shed further

light, showing evidence of both producer currency pricing and dominant currency pricing in the short

term—although with significantly lower prevalence of dominant currency pricing than in manufacturing

(Figure 9).

16

In the medium term, quantities become insensitive to US dollar exchange rates, while the

effect of bilateral exchange rates becomes stronger. Overall, the data indicate that certain service sectors,

tourism in particular, respond more to bilateral exchange rate movements than to US dollar exchange rate

fluctuation, especially relative to the patterns observed in manufacturing. This implies that exchange rates

may have important differential short-term effects across industries and, thus, that supportive policies

may need to take this into account. In addition, the evidence implies that greater specialization in

manufacturing or services across countries and over time can play a role in driving differences in trade

flows’ sensitivity to exchange rate movements.

16

When the currency of a tourism destination country (exporter) appreciates 10 percent vis-à-vis that of the origin

country, tourism arrivals at the destination are found to fall 2.7 percent in the short term and more than 4 percent in

the medium term. Hotel nights spent also fall by a similar magnitude. Depreciation of the tourists’ (importer’s)

currency against the US dollar also discourages outbound tourism, although by only half the magnitude in the short

term.

-0.4

-0.2

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

Bilateral US$ Bilateral US$ Bilateral US$ Bilateral US$

Short term Medium term Short term Medium term

Unweighted Weighted

DOMINANT CURRENCIES AND EXTERNAL ADJUSTMENT

18 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Figure 9. Tourism Volume Elasticities to Bilateral and US Dollar Exchange Rates

1

Source: Li and Meleshchuk (forthcoming).

1

Based on Eurostat tourism data for 33 reporting countries and 43 partner countries during 1991–2017. Short run

(SR) and medium run (MR) refer to same year as the shock and the cumulative effect over three years, respectively.

95 percent confidence bands are reported.

DOMINANT CURRENCY FINANCING

The US dollar is also widely used in corporate financing. Consequently, exchange rates can also affect trade

flows through balance sheet effects (financial channel), and the effects depend jointly on the pricing and

financing currencies.

A. Key Concepts

16. The US dollar is commonly used in cross-border corporate financing, notably in emerging

market economies. As documented by Bräuning and Ivashina (2017), the US dollar is overwhelmingly the

currency of choice in syndicated cross-border loans and is often used in other forms of cross-border

financing. As discussed by Gopinath and Stein (2018), this phenomenon is associated with the

preponderance of the US dollar in trade invoicing, which leads to large demand for US dollar safe assets

and therefore makes US dollar funding systematically cheaper than funding in other currencies. Other

arguments for US dollar financing include firms’ desire to reduce the mismatch between the currencies of

their revenues and those of their financing.

17,18

17

See Akinci and Queralto (2019) and Gabaix and Maggiori (2015).

18

Availability of hedging for exchange rate risk may also be a factor behind the choice of financing and pricing

currencies.

(continued)

-0.8

-0.6

-0.4

-0.2

0.0

0.2

Bilateral US$ Bilateral US$ Bilateral US$ Bilateral US$

Short term Medium term

Short term Medium term

Arrivals of nonresidents at hotels Hotel nights spent by nonresidents

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 19

17. Dominant currency financing can shape the mechanism of exchange rates, depending on its

match (or mismatch) with the currency of trade pricing. That is, the response of trade flows to

exchange rate movements depends on the combination of pricing and financing currencies (Table 1):

19

• Producer currency pricing: If trade is priced in the currency of the producer/exporter, a depreciation

increases export volumes and reduces import volumes. This is the standard trade channel (expenditure

switching effect). So, if firms rely on local currency financing, there is no currency mismatch between

financing and revenues and, thus, the financial channel through exports is muted. In contrast,

borrowing in foreign currency entails a currency mismatch between financing and revenues, and a

depreciation tightens the financing conditions faced by exporters and importers alike, dampening the

response of export volumes and amplifying the response of import volumes, relative to the case of

local currency borrowing.

• Dominant currency pricing: In this context, exporting firms’ net revenues in US dollars are stable, while

importing firms that sell locally and therefore price in the local currency have revenues that are

volatile in US dollars. For exporters, there is no mismatch between pricing and financing currencies,

and a depreciation has a similar impact on revenues and financial costs—this is the so-called natural

hedge. Hence, the financial channel through export volumes is muted. In contrast, importers who

borrow in US dollars have a mismatch between their pricing and financing currencies, and a

depreciation can lead to tighter financial conditions and to a decline in import volumes, relative to the

case of local currency borrowing.

20

Table 1. Expected Effects of a Depreciation on Trade Volumes

Source: IMF staff.

Note: Expected effects of a depreciation of the domestic currency via-à-vis all other currencies under both PCP

and DCP are reported. DCP = dominant currency pricing; FX = foreign currency; PCP = producer currency pricing.

Thus, the financial channel reinforces expenditure switching through imports regardless of the

prevailing pricing currencies;

the effects on export volumes are, however, ambiguous under

producer currency pricing and significantly weaker

under dominant currency pricing.

B. Macro Evidence

18. While data on corporate balance sheets are limited, the available information points to

rising foreign currency liabilities, especially in emerging market economies (see Box 3). Foreign

19

Bruno and Shin (2020) explore related aspects, although they focus on the impact of global shifts of the US dollar

(vis-à-vis other currencies) through the supply of credit to emerging market firms. They focus, in particular, on the

effect through global banks’ balance sheets (as they tend to rely on US dollar funding).

20

Similar effects under dominant currency pricing and foreign currency borrowing are reported by Akinci and

Queralto (2019).

expenditure switching

(trade channel)

additional FX debt

effect

(financial channel)

expenditure switching

(trade channel)

additional FX debt

effect

(financial channel)

PCP

+ - - -

DCP

≈ 0 ≈ 0 - -

Export volumes

Import volumes

DOMINANT CURRENCIES AND EXTERNAL ADJUSTMENT

20 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

currency debt in nonfinancial firms has risen rapidly since the early 2000s, especially in emerging market

economies and following the global financial crisis—partly reflecting the low-interest-rate environment in

advanced economies (Figure 10, left panel)—although average ratios to total debt have been relatively

stable, pointing to an overall increase in indebtedness (Figure 10, right panel). Reliance on foreign

currency financing remains significantly higher in emerging market economies than in advanced

economies, even though there is significant variation within both groups (Figure 11).

Figure 10. Foreign Currency Borrowing in the Nonfinancial Corporate Sector

(US dollars and percent of total credit)

Sources: Bank for International Settlements; IMF, International Financial Statistics; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: AEs = advanced economies; EMs = emerging market economies; FC = foreign currency; NFC = nonfinancial corporate sector;

Figure 11. Foreign Currency Exposures in the Nonfinancial Corporate Sector, by Instrument, 2019

(Percent of total credit)

Sources: Bank for International Settlements; IMF, International Financial Statistics; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: In economies that host large multinational companies foreign currency exposures reflect in part the global nature of their activities.

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

2003q1 2005q1 2007q1 2009q1 2011q1

2013q1

2015q1 2017q1 2019q1

Average Foreign Currency Exposure

(Share of FC debt in Nonfinancial Corporate Debt)

Average AEs EMs

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

6000

2003q1 2005q1

2007q1 2009q1 2011q1 2013q1 2015q1 2017q1

2019q1

Total Foreign Currency Debt in the Corporate Sector

(Million US Dollars)

AEs

EMs

EM share (right scale)

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

CHN

IND

KOR

ISR

BRA

THA

MYS

PHL

POL

ZAF

HUN

RUS

CZE

CHL

TUR

IDN

ARG

MEX

Emerging Market Economies

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

PRT

ITA

ESP

BEL

USA

JPN

AUT

FRA

DEU

FIN

GRC

NOR

AUS

DNK

CAN

SWE

IRL

NLD

Advanced Economies

Debt securities Loans

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 21

Box 3. Constructing Foreign Currency Debt Exposure Measures for Nonfinancial Firms

Data on the currency composition of nonfinancial corporate sector debt are scant. Although credit registries

provide direct information about the structure of borrowing at the firm level, these registries are generally available

only for a few countries and years. Macro-level data sets based on external debt statistics (for example Bénétrix,

Lane, and Shambaugh 2015), on the other hand, focus on the currency composition of external liabilities, do not

isolate the corporate sector, and abstract from local foreign currency borrowing. Two new indicators of corporate

foreign currency exposure are constructed to overcome these limitations:

1

• An indicator that follows the top-down approach of Kalemli-Ozcan, Liu and Shim (2018) and relies on the BIS

Global Liquidity Indicators database: The latter reports nonfinancial foreign currency debt held by both local

and foreign lenders on firms, government, and households. To arrive at an indicator for the nonfinancial

corporate sector, the latter measure is purged of (1) international debt securities issued by the central

government and (2) residual foreign currency loans (both cross border and local) owed by the government

and household sectors using information available in BIS Locational Banking Statistics and IMF Monetary and

Financial Statistics.

• A second indicator that follows a bottom-up approach by adding (1) foreign currency corporate debt

securities (from BIS International Debt Statistics); (2) cross-border foreign currency loans to nonfinancial firms

(from BIS Locational Banking Statistics) and (3) local foreign currency loans to nonfinancial firms (from IMF

Monetary and Financial Statistics).

The computed indicators—covering 36 major advanced and emerging market economies during 2001–19—are

used for the analysis of this section.

____________

1

See Appendix 2 for further details.

19. The macro evidence suggests that dominant currency financing amplifies the short-term

effects of exchange rates through imports. The framework presented in the section on dominant

currency financing is augmented to evaluate the effect on trade flows of a country’s currency depreciation

(vis-à-vis all other currencies) depending on the level of aggregate foreign currency borrowing.

21

As

expected, the analysis points to greater contraction in imports in response to a depreciation in importing

countries that rely more on foreign currency financing (Figure 12, panel 1). Meanwhile, the degree of

foreign currency financing in exporting countries does not appear to materially alter the effect of

exchange rates (not shown).

20. The muted effect through exports of foreign currency financing reflects the “natural

hedge” under dominant currency pricing. This is visible when comparing the estimated export volume

responses for different levels of foreign currency financing and different degrees of dominant currency

pricing (Figure 12, panel 2):

22

• When US dollar invoicing is low (producer currency pricing case) a depreciation increases exports

through the standard trade channel (because it boosts competitiveness (stand-alone effect), whereas

the effect through the financial channel is negative because the depreciation increases the burden of

US dollar debt.

21

See Appendix 3 for further details.

22

See further evidence of exporters’ natural hedge by Aguiar (2005), Du and Schreger (2016), Kalemli-Ozcan and

others (2016), and Kalemli-Ozcan (2019).

DOMINANT CURRENCIES AND EXTERNAL ADJUSTMENT

22 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

• When US dollar invoicing is high (dominant currency pricing case), by contrast, both the trade and

financial channels through exports are muted. While the depreciation improves the exporters’

competitiveness (trade

channel) and balance sheets (financial channel), export prices in US dollars

remain unchanged, as do export volumes.

Figure 12. Short-Term Trade Volume Elasticities

(Response to a 1 percent depreciation vis-à-vis all other currencies)

Source: IMF staff estimates.

Note: The bars in the left panel represent the full effect of a depreciation for different shares of foreign currency debt. All reported

estimates are significant at the 1 percent level. The right panel reports the response of export volumes for a country with a median

share of US dollar debt. Bars indicate 90 percent confidence bands. See Appendix 3 for further details on the methodology. DCP =

dominant currency pricing; FX = foreign currency; PCP = producer currency pricing.

C. Micro-Level Evidence

21. Evidence from firm-level data confirms the implications of dominant currency financing for

the mechanics of exchange rates. Available micro-level data from Colombian companies and the sharp

depreciation of the Colombian peso in 2014 provide a natural experiment to carefully identify the financial

channel of exchange rates.

23

Casas, Meleshchuk, and Timmer (2020) trace whether importing, exporting,

and the borrowing behavior of firms following the depreciation depend on the extent of pre-shock

leverage in foreign currency. The evidence shows that firms with higher foreign currency leverage

experienced significantly larger contractions in imports (Figure 13, panel 1), while there is no visible effect

of foreign currency leverage on exports. Given the high prevalence of US dollar invoicing in Colombia, the

limited impact of foreign currency leverage on exports confirms that, under dominant currency pricing,

exporters who borrow in US dollars are largely hedged. In addition, firms with higher foreign currency

leverage reduced their borrowing in foreign currency significantly more (Figure 13, panel 2)—although

they were also able to partially offset the latter with higher local currency funding—indicating the impact

23

Casas, Meleshchuk, and Timmer (2020) compile a rich data set of nearly 22,000 firms over the period 2012–17,

combining (1) firm-level data on international trade transactions from the Colombian statistical agency; (2) balance

sheet firm-level data from the Orbis global database; and (3) information on commercial loans issued by Colombian

banks from the credit registry of the Superintendencia Financiera.

-0.6

-0.4

-0.2

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

Stand-

alone

FX debt Combined Stand-

alone

FX debt Combined

0% USD invoicing (PCP) 100% USD invoicing (DCP)

-0.5

-0.4

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

10th

(6.3%)

25th

(8.7%)

50th

(13.3%)

75th

(19.3%)

90th

(24.4%)

1. Short

-term import volume elasticity, by FX debt share

(response to a depreciation against all currencies)

2. Short-term export volume elasticity, by USD invocing share

(response to a depreciation against all currencies)

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 23

of balance sheet effects on the availability of financing. The evidence shows that, overall, although

exporting firms are naturally hedged, foreign currency financing exacerbates the effect of exchange rates

through imports. Moreover, the later amplification effect can be macroeconomically sizable, as illustrated

by a counterfactual exercise comparing what the import contraction would have been under hypothetical

higher and lower levels of foreign currency financing (Figure 14).

Figure 13. Effect of Foreign Currency Leverage on Firms’ Trade Flows and Borrowing

(Differential effect of one standard deviation higher foreign currency leverage)

Sources: Casas, Meleshchuk, and Timmer (2020); and IMF staff calculations.

Note: Bars depict how one standard deviation (3.2%) higher foreign currency leverage before the shock alters the impact of the

more than 50 percent depreciation of the Colombian peso vis-à-vis the US dollar on several variables during the 15 quarters

following the shock. Variables in the left panel are imports (column 1), exports (column 2), imports of firms that are not exporters

(column 3), and imports of exporting firms (column 4). Variables in the right panel are borrowing in foreign currency (column 1)

and borrowing in local currency (column 2). Column 3 depicts the implied effect on total borrowing for an average firm with non-

zero foreign currency loans before depreciation (left axis). FC = foreign currency; LC = local currency.

*** indicates statistical significance at the 99 percent level.

Figure 14. Financial Channel of Exchange Rate: Evidence from Colombia

(Import performance for various levels of foreign currency financing)

Sources: Casas, Meleshchuk, and Timmer (2020); and IMF staff calculations.

Note: The solid line depicts actual imports. The long-dashed (short-dashed) lines depict counterfactual below 0 (7) percent foreign

currency leverage. FC = foreign currency.

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.0

2012q1

2013q1

2014q1

2015q1

2016q1 2017q1

Index, 2014Q3=1

Hypothetical, no FC leverage

Hypothetical, high FC leverage

Actual

-30%

-20%

-10%

0%

10%

Imports

Exports

Imports (non-

exporters)

Imports

(exporters)

***

***

-6%

-4%

-2%

0%

2%

-60%

-40%

-20%

0%

20%

FC borrowing LC borrowing

Total borrowing

(right axis)

***

***

1. Trade Flows

2. Firm Borrowing

DOMINANT CURRENCIES AND EXTERNAL ADJUSTMENT

24 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

KEY TAKEAWAYS AND FUTURE WORK

22. The widespread use of the US dollar in trade invoicing shapes how trade flows respond to

exchange rates, leading to tepid export volume responses in the short term. This mechanism is

particularly pronounced in emerging market economies, where US dollar invoicing is more widespread.

US dollar invoicing is pervasive in manufacturing trade and also prevalent, although seemingly less so, in

services trade. Over time, the traditional exchange rate mechanism through both export and import

volumes reemerges, especially in larger economies, where US dollar pricing is less prevalent. The

dominance of the US dollar in trade invoicing also implies that a generalized shift in the value of the US

dollar vis-à-vis other currencies entails contractionary or expansionary effects on global trade and

economic activity.

23. The financing currency of firms engaged in international trade can also shape the process

of external adjustment through balance sheet effects. New analysis indicates that exposure to US

dollar borrowing has a limited impact on activities of exporting firms—which are naturally hedged in the

context of US dollar invoicing. Meanwhile, reliance on foreign currency financing amplifies the contraction

of imports in response to weakening of the domestic currency, arguably with negative effects on the

domestic economy.

24. While beyond the scope of this note, the design of optimal policies needs to take into

account the prevalence of dominant currencies for the behavior of exchange rates. With a weaker

short-term response of trade volumes to exchange rates, rebalancing external accounts or buffering the

domestic economy from macroeconomic shocks will generally require larger exchange rate movements,

and, when the latter carry adverse side effects—for example, through balance sheets or inflation—other

supportive policies may be needed. These considerations are particularly important for emerging market

and developing economies, where dominant currency pricing and financing are more common.

25. The dominance of the US dollar in trade and finance is likely to amplify the impact of the

COVID crisis. The dominance of the US dollar implies that the observed weakening of emerging and

developing countries’ currencies is unlikely to provide material boost to their economies in the short term

as the response of goods exports will be muted while some sectors that would normally respond more to

exchange rates—like tourism—are likely to be impaired by COVID-related containment measures and

consumer behavior changes. Moreover, the generalized strengthening of the US dollar may magnify the

short-term fall in global trade and economic activity as both higher domestic prices of traded goods and

services and negative balance sheet effects on importing firms contribute to lower demand for imports

throughout the emerging and developing world.

26. Tackling data gaps on invoicing and financing currencies at the firm and aggregate levels is

paramount. A key insight from the analysis is that the structure of invoicing currencies may be as

important as the composition of trading partners when it comes to measuring competitiveness in the

short term, which suggests that current indicators of competitiveness may need to be revamped or

complemented by invoicing-currency-based measures. In addition, the analysis considered the pricing

and financing currency choices as given. These decisions and their effects, however, are not independent

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 25

of one another. Thus, granular data to map pricing and financing currencies at the firm (or sector) level

are of the essence to understand the underlying market frictions that give rise to these features of

international trade and their interactions, evaluate their implications for exchange rate flexibility, and

design appropriate macroeconomic policies. Greater efforts in data collection are key to further progress

in this regard.

DOMINANT CURRENCIES AND EXTERNAL ADJUSTMENT

26 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Appendix 1. Dominant Currency Pricing

24

When prices are sticky, the invoicing currency of cross-border transactions has significant implications for

external adjustment (that is, how trade prices and volumes react to exchange rate movements). To

illustrate this, consider a simple representation of trade flows—

—which denotes the value of trade

from country to country , measured in country ’s currency (superscript). Trade flows can be expressed

in terms of prices and quantities:

=

.

Trade prices in the exporter’s currency

(

)

can be further decomposed into the exporter’s marginal

cost in its domestic currency

(

)

and the markup

:

=

.

Under sticky prices, quantities can be assumed to be a function of prices in the currency of the destination

country (the importer)—that is, traded volumes are demand-determined—as well as some demand shock

(

):

,

.

In this setup, the effects of exchange rate changes on bilateral trade flows from to are driven (directly)

by the exchange rate pass-through to prices in the exporter’s currency (

) and (indirectly) by the pass-

through to prices in the importer’s currency (

), with the latter affecting traded quantities.

The Mundell-Fleming Framework, Producer Currency Pricing, and Local Currency Pricing

Under the Mundell-Fleming framework, the most relevant exchange rate for trade between countries

and would be their bilateral exchange rate (

). This is because the Mundell-Fleming framework does

not allow for the following:

- Product market frictions, whereby exporters may charge different markups across destination

markets (for example, due to strategic market complementarities). Hence, exporters’ markups

do not respond to exchange rate changes.

- Exporters’ use of imported intermediate inputs or decreasing marginal returns to labor: This

means that exporters’ marginal costs

(

)

do not respond to exchange rate fluctuations either.

If exporters’ markups and marginal costs do not respond to exchange rate fluctuations, the exchange rate

pass-through to prices in the exporters’ currency is zero, while the pass-through to prices in the

importers’ currency is 1. These predictions are consistent with the producer currency pricing (PCP)

paradigm, which assumes that international trade is invoiced in the currency of the exporter and that

prices in that currency are rigid. Furthermore, nominal depreciation increases the price of imports relative

to exports, thus improving competitiveness.

24

Prepared by Gustavo Adler, Sergii Meleshchuk, and Carolina Osorio Buitron. This technical appendix draws from

Chapter 2 of the 2019 External Sector Report

.

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 27

An alternative international pricing framework developed by Betts and Devereux (2000) and Devereux and

Engel (2003)—in response to evidence against the law of one price that holds under PCP—assumes that

prices are set and are rigid in the currency of the importer—so-called local currency pricing (LCP). In this

case, bilateral exchange rate movements should lead to a complete pass-through to prices in the

exporter’s currency

(

)

and zero pass-through to prices in the importer’s currency

. Hence, a

nominal depreciation increases the prices of exports relative to imports, leading to a deterioration in

competitiveness.

The Dominant Currency Pricing Framework

Recent empirical work raises questions about the validity of both PCP and LCP, showing that trade tends

to be invoiced in a small number of “dominant currencies,” with the US dollar playing a prominent role

(Goldberg and Tille 2008; Gopinath 2015), and that trade prices tend to be rigid in such currencies

(Gopinath and Rigobon 2008; Fitzgerald and Haller 2012). More recently, Casas and others (2017) and Boz,

Gopinath, and Plagborg-Møller (2018) show that, when prices are set in a third (dominant) currency ($),

trade flows between countries and are also affected by exchange rates vis-à-vis the dominant

currency (

$

and

$

). They find that the exchange rate pass-through from the dominant currency to both

export and import prices is high, while the pass-through of the bilateral (nondominant) exchange rate is

small, thus providing evidence against both PCP and LCP.

25

The authors also develop a model to explain

these phenomena: the dominant currency pricing (DCP) framework.

Building on the approach proposed by Boz, Gopinath, and Plagborg-Møller (2018) and Gopinath and

others (2020), the dominant role of the US dollar is explored by analyzing, at the country-pair level, the

relationship of traded prices and quantities to the exchange rate vis-à-vis the trading partner (

) and the

US dollar (

$

).

The framework is extended to examine the implications of DCP for the exchange rate elasticity of the

trade balance. To this end, trade prices and volumes are estimated from the perspective of both the

exporter and the importer. On the export (import) side, the focus is on the effects of a depreciation of the

exporter’s (importer’s) currency on trade volumes and prices in the exporter’s (importer’s) currency. All

these elements are necessary to compute the trade balance effect of a depreciation, for which a country-

level perspective that accounts for the exporting and importing behavior of each economy is necessary.

Specifically, while the empirical estimation focuses on trade flows between country pairs (

), the

exchange rate effect on, say, country a’s trade balance with any trading partner b is given by

=

. Summing across all trade partners yields an expression for a’s overall trade balance

response:

=

.

25

These empirical exercises can be regarded as (indirect) tests for the presence of frictions that generate exchange

rate sensitivity in markups (such as strategic pricing complementarities faced by exporters in destination markets) or

marginal costs (such as the use of imported inputs by exporting firms).

(continued)

DOMINANT CURRENCIES AND EXTERNAL ADJUSTMENT

28 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

This expression can be used to assess the impact of different exchange rate movements once the relevant

price and volume elasticities vis-à-vis the bilateral and US dollar exchange rates are estimated. Finally, the

country-level price and quantity elasticities are combined with measures of trade openness (/ and

/) to derive the response of the trade balance, as a share of output, which takes the following form:

26

=

+

.

+

$

+

$

.

$

[

…

]

,

( )

in which X/Y and M/Y denote export- and import-to-GDP ratios, respectively, and the last term on the

right side indicates a similar expression for imports to the one written in full for exports.

This general expression can be used for two thought experiments of interest:

• External adjustment: The relevant thought experiment from the perspective of correcting a country’s

external imbalance is a movement of its exchange rate vis-à-vis all other currencies. In the example

above, this would imply a shift in ’s currency vis-à-vis all other currencies, including the US dollar

(that is,

=

$

= for all ). The exchange rate between and any other country would

vary (in the same proportion), while exchange rates between any other two currencies would remain

unchanged.

• Global US dollar shifts: If prices are set in US dollars, movements in the value of this currency vis-à-vis

others would have implications for bilateral trade not only between the United States and the rest of

the world, but also among third countries. These effects can be gauged by studying the responses of

bilateral trade flows to movements in the exchange rate vis-à-vis the US dollar, while other bilateral

exchange rates remain unchanged (that is,

$

= ;

= 0 for all $).

Empirical Estimation

Building on the empirical framework of Gopinath and others (2020), the following set of equations are