Office Of ReseaRch and educatiOn accOuntability

dRiveR educatiOn in tennessee

JasOn e. MuMpOweR

Comptroller of the Treasury

deceMbeR 2022

dana spOOnMORe

Legislative Research Analyst

Introduction

Safety and nancial benets of driver education

Driver education programs in Tennessee public schools

District funding for driver education

Other potential funding sources for driver education

Private driver education companies are popular alternatives to public school programs

Policy options

Appendix A: Tennessee graduated driver license program

Appendix B: State requirements for driver education

Appendix C: Litigation privilege taxes that are partly allocated to promoting driver education and

expanding highway safety

Appendix D: Full distribution of litigation privilege tax revenue

Appendix E: Driver education student count and allocation per district

Appendix F: Litigation privilege tax allocations for driver education | 2017-2022

Appendix G: Tennessee Title I schools serving students of driving age

Appendix H: Requirements for commercial driver training schools and instructor licenses

Endnotes

Contents

3

4

7

15

19

24

25

27

28

30

31

32

33

34

39

40

3

Introduction

In 2022, the 112th General Assembly passed Public Chapter 1090, requiring the Comptroller’s Oce of

Research and Education Accountability (OREA) to collaborate with multiple state agencies to perform a

comprehensive study on the availability and aordability of driver education in Tennessee, including:

• the number of Title I public high schools that oer driver education courses to students, and of that

number, the average cost to each Title I public high school to provide a driver education course to students;

• the aordability of driver education provided by private companies;

• the benets of students receiving driver education courses in high school, including safety benets and

any insurance savings;

• the eectiveness of driver education in reducing automobile accidents involving teen drivers and in

reducing teen motor vehicle fatalities;

• the possibility of using a dual enrollment grant to cover all or a portion of the cost of a driver education

class for students in Title I public high schools, if community colleges were to oer driver education; and

• sources of funding to provide driver education to students in Title I public high schools at low or no cost.

Driver education in public schools, once a rite of passage for novice drivers preparing for the open road, has

diminished in popularity over the past few years. In 2021-22, 60 school districts in Tennessee received state

funding for the 12,660 students enrolled in their driver education classes. is is a decline from the 2017-18

enrollment of 15,429 in 65 districts that oered driver education. e decline in oerings and enrollment

may be due to a number of factors, including a lack of funding, lack of certied instructors, and competition

from private driver education agencies. In spite of these factors, driver education is still oered in many

districts across Tennessee.

Exhibit 1: Driver education is offered in many Tennessee school districts

Source: Tennessee Department of Education.

Methodology

PC 1090 asked OREA to collaborate with the Tennessee Department of Education (TDOE), the Tennessee

Student Assistance Corporation (TSAC), the Tennessee Department of Labor and Workforce Development

(TDLWD), and the Tennessee Department of Human Services (TDHS). Additionally, OREA worked with

the Tennessee Department of Safety and Homeland Security (TDSHS) and Tennessee Highway Patrol (THP).

Districts shaded red

received funding for

driver education in

2021-22.

4

In July of 2022, OREA distributed a survey about driver education to all of the 141 Tennessee school district

superintendents. Over three-quarters of district superintendents or their representatives

A

(representing 109

districts) responded to the survey.

In September of 2022, OREA distributed a survey to the principals of all 2021-22 Title I schools serving

students of driving age (i.e., students in grades 10-12). Over a third of the principals (representing 62 schools)

completed the survey.

Safety and nancial benets of driver education

Many factors may keep teenagers from signing up for a driver education course, including busy schedules,

nancial concerns, or a general lack of interest. Understanding the potential benets of completing driver

education may encourage some teenagers and their parents to dedicate time and resources to driver education

either through the school system or a private agency.

Past studies vary in their conclusions about the effectiveness of

driver education on the safety of teen drivers

Driver education has been used to train new drivers for decades, giving them a chance to gain valuable on-

the-road experience under the direction of an instructor as well as instruction in the basic rules of the road in

a classroom setting. While parental training is also a traditional method of teaching teenagers how to drive, it

may not be as comprehensive as a full driver education course conducted by a certied instructor.

e eectiveness of driver education, however, has been debated for as long as it has existed, and there is a

shortage of thorough studies on the topic. Methodological aws in early studies resulted in a lack of reliable

data, and better-controlled studies yielded conicting conclusions. A small 1982 study found no signicant

eect of driver education on crash reduction,

1

and another study of data from the United Kingdom and New

Zealand showed an increase in crashes for teens who have completed a driver education course.

2

Teens who

take driver education often get their driver licenses earlier than those who do not, and earlier licensure is

linked with increased crash risk because of the increased opportunity to drive.

Graduated driver license (GDL) programs, such as the one implemented by Tennessee in 2001, are designed

to address the risks that often accompany young drivers. GDL programs are multi-tiered programs designed

to ease young novice drivers into full driving privileges as they become more mature and develop their driving

skills. A 2007 study concluded that GDL programs have reduced the occurrence of fatal trac crashes among

drivers age 15-17. See Appendix A for more information on the Tennessee GDL program.

More recent studies have linked driver education to fewer trac crashes. In 2015, researchers at the Nebraska

Prevention Center for Alcohol and Drug Abuse analyzed the driving data of 151,880 Nebraska teenagers

who received their Provisional Operator’s Permit between 2003 and 2010.

B

e study compared trac

records of crashes and violations between drivers who had completed a driver education course and those who

had completed 50 hours of supervised driving only. While acknowledging data limitations (e.g., the study

analyzed drivers in a small, rural state without indicators of the quality of driver education courses), researchers

concluded that teens who had completed driver education courses had fewer crashes, including those resulting

in injury or fatality, than those who had accrued 50 hours of supervised driving (submitted in a driving log

certied by a parent or guardian) without a classroom course. e study results suggest that driver education is a

“meaningfully eective approach to reducing trac crashes and especially injury or fatal crashes among teens.”

3

A

Superintendents were asked to either respond to the survey themselves or share the survey with the person in the district who knows the most about driver education.

B

e Provisional Operator’s Permit is a restricted driver license given to drivers who have had a learner’s permit for at least six months and have successfully

completed a driver safety course or completed 50 hours of supervised driving, certied by a parent or guardian. e permit is part of Nebraska’s graduated driver

license program. For information on Tennessee’s graduated driver license programs, see Appendix A.

5

In 2017, two studies examined whether driver education programs approved by the Oregon Department

of Education eectively reduced collisions and convictions among teen drivers. e rst study sampled a

relatively small number of teens via an online survey and found that driver education did not signicantly

aect driver safety. In a much larger second sample, however, driver education status was associated with a

lower incidence of collisions and convictions.

4

Even though the eectiveness of driver education is disputed,

many Americans believe that it is a vital step in a student

driver’s path to full licensure. In May 2019, Volvo Car USA

administered an online survey of 2,000 adults ages 18 and

over who possessed driver licenses. Ninety percent of survey

respondents believed that driver education should be a part

of public education today. Additionally, nearly half of those

participating in the survey expressed belief that a minimum of

50 behind-the-wheel practice hours, either as part of a driver

education course or completed with a parent or guardian,

should be required before taking a driving test.

5

Teen drivers are involved in an average of 21 percent of Tennessee trac crashes each year

e rst few years on the road for new drivers tend to be the most dangerous due to inexperience and

maturity levels. A 2012 study of teen road safety in North Carolina suggested that certain teen driver behavior

associated with crashes (e.g., lack of attention, failure to yield, overcorrection, exceeding the speed limit, etc.)

could be due in part to a lack of knowledge on how to handle a full range of driving situations.

6

Regardless

of the cause, state and national data show a correlation between a driver’s age and their likelihood of being

involved in an accident.

According to the Tennessee Highway Patrol (THP), an average of 186,721 trac crashes occurred in

Tennessee each year between 2010 and 2021. An average of 21 percent of those crashes involved a driver who

was under the age of 21.

C

ere has been a slight decrease in the percentage of crashes involving young teen

drivers, with incidents decreasing gradually from 24 percent in 2010 to 20 percent in 2021.

Exhibit 2: Since 2010, an average of 21 percent of trafc crashes in Tennessee per year

involved a driver under the age of 21

Note: Includes driver-operated vehicles only. Excludes parking lot and private property crashes as well as crashes with less than $400 damage.

Source: Tennessee Highway Patrol.

C

THP uses a category for drivers under 21 when aggregating trac crash data and a teen driver category for trac fatalities.

OREA did not identify any existing

studies of the eectiveness of driver

education programs in Tennessee. A

study of eectiveness would require

data on the number of teen drivers who

have completed a driver education

course. Driver license applications in

Tennessee do not ask applicants if

they have completed a driver education

course, and the state does not collect

this information in any other way.

23.96%

23.02%

22.63%

21.73%

21.52%

21.61%

21.42%

21.07%

20.13%

20.01%

20.06%

19.99%

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

21 & up 20 & under % of all crashes that involve ages 20 & under

6

While the percentage of youth-involved crashes has decreased over the past decade, the number of trac

fatalities involving teen drivers has increased in recent years, as well as the overall number of trac fatalities

in Tennessee. ere were 1,024 trac fatalities in the state in 2017, involving 86 teen drivers. In 2021, 1,327

trac fatalities occurred, with 147 involving teen drivers, increases of nearly 30 and 71 percent, respectively.

Eleven percent of all Tennessee trac fatalities involved teen drivers in 2021, compared to just over 8 percent

in 2017.

Exhibit 3: The overall number of trafc fatalities has risen almost every year since 2017, as

well as the number of fatalities involving teen drivers

Source: Tennessee Highway Patrol.

Many car insurance companies incentivize driver education by

offering discounts to teen drivers who complete a course

Many factors can aect the cost of car insurance, including the driver’s safety history, vehicle type, credit score,

and location. Because teen drivers are more likely to be in an accident due to their lack of experience, they are

the most expensive group of drivers to insure. e national average car insurance rate for all drivers is $1,553 per

year. As of June 2022, the average annual rate for 17-year-old drivers is $4,962 for females and $5,661 for males.

7

Tennessee does not statutorily require car insurance companies to oer discounts to help oset the cost

of insuring teen drivers, but many car insurance providers oer discounts to teens who complete a driver

education course. e discount varies by company and the multiple other factors that determine a driver’s rate.

For example, State Farm’s Driving Training Discount is for young drivers who have completed an acceptable

driver education course, which must be conducted by a licensed or certied instructor and include classroom

instruction in basic trac and safety rules, plus on-the-road driving experience. For unmarried individuals

who are 18 years or younger, the Driver Training Discount ranges from 3 to 10 percent on bodily injury and

property damage liability, medical payments, and comprehensive and collision coverage premiums.

86

84

124

130

147

8.40%

8.27%

10.92%

10.68%

11.08%

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

0

200

400

600

800

1,000

1,200

1,400

2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

No teen driver Traffic fatalities involving teen drivers % traffic fatalties involving teen drivers

7

Driver education programs in Tennessee

public schools

As of March 2020, 32 states required students 18 and younger to complete a driver education program

before obtaining a driver license (see Appendix B for the driver education requirements in other states).

Driver education programs are less prevalent than they once were in American public schools. According

to the American Driver and Trac Safety Education Association

(ADTSEA), 95 percent of students had access to public driver

education in the 1970s. At the time, most states had one to ve sta

members supervising driver education programs.

8

In 2019, ADTSEA

reported that 10 states included driver education in the state’s public

school curriculum, and most of those 10 states had one person

managing the state’s driver education program.

9

Tennessee does not require teenagers to complete a driver

education course before obtaining a license, and most driver

education programs aliated with the Tennessee public

school system are governed at the local level.

D

TDOE does

not employ a sta member who oversees these programs

and the State Board of Education does not authorize course

standards. OREA was unable to verify if education standards

have ever existed.

School-based driver education programs are available in many Tennessee school districts across the state, and

these programs vary in their implementation from district to district. On OREA’s July 2022 survey of Tennessee

school district superintendents, nearly half of respondents (47.7 percent or 51 superintendents) stated that their

districts have oered driver education in at least one of

the past ve school years and plan to oer it again in the

2022-23 school year. Around 37 percent of respondents

indicated that their districts do not oer the course. Four

districts have oered driver education in at least one of

the past ve years but do not plan to oer it in 2022-

23, while three districts plan to add the course after not

oering it for at least ve years.

D

ough Tennessee does not require a driver education course, the state does require 50 hours of behind-the-wheel practice with a parent, guardian, or driving

instructor before graduating from a learner’s permit to a driver license. See Appendix A for more information on Tennessee’s graduated driver license program.

We do not have the numbers that

we used to have taking the driver ed

course, but we are still very happy to

oer it to our students.

OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

I think it would be extremely benecial for

our students to be able to receive driver

education in our schools but at this point

we are using our resources to sta our

academic programs and do not have extra

for a driver education program.

OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

[We] used to oer driver ed many years ago; it

ceased when the teacher retired and the cost

of the vehicle changed. We are oering this

course [again] as we believe it will be highly

impactful for our students to be taught safe

driving by an educator licensed to do so.

OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

8

Exhibit 3: Driver education availability (n=108)

Source: OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

The overall number of districts offering driver education courses

has decreased slightly over the past few school years

Fifty-one districts oered driver education courses in the 2017-18 and the 2018-19 school years. at number

decreased to 48 for the next two school years and decreased again, to 46 districts, in 2021-22. Superintendents

cited a lack of qualied teachers, decline in student interest, and eects of the COVID-19 pandemic as

reasons for not oering the course in certain years. According to survey responses, the decision of whether to

oer driver education is usually made at the district level.

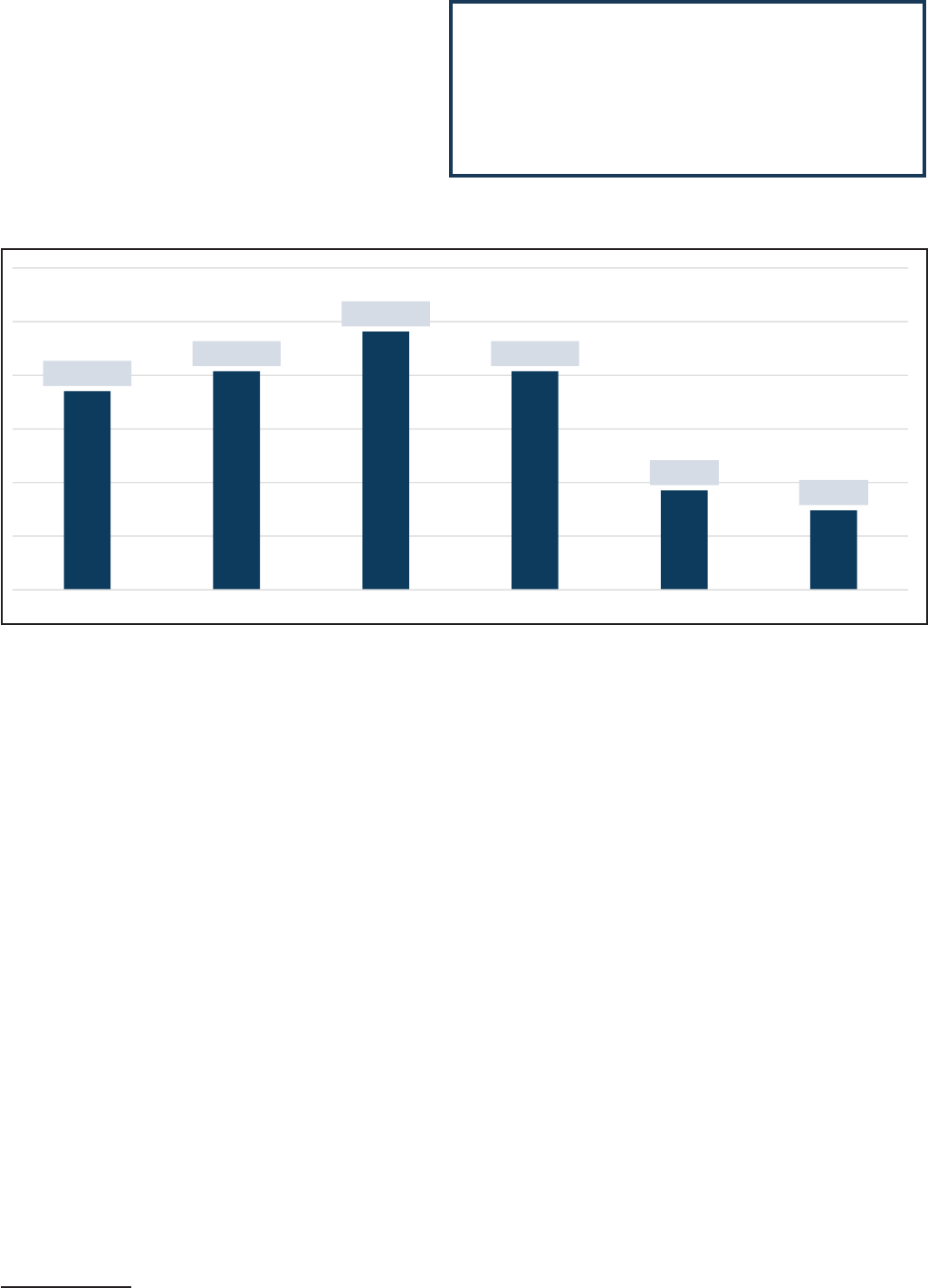

Exhibit 4: The number of districts offering driver education has decreased slightly since 2017-18

Source: OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

In most districts (77.6 percent of survey respondents), driver education courses are available to all students

who live in the district and are enrolled in the school where the course is oered. Other districts oer driver

education to all students in the district from one central location

such as a virtual academy, career and technical center, or a single high

school that hosts driver education for the entire district. Most survey

respondents (67.9 percent or 36 superintendents) indicated that a driver

education course is oered at a single high school in the district. (Several

respondents represented districts that have only one high school.)

51 51

48 48

46

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

2017-18 2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

We are a large district, but we

only oer the program at a single

location serving multiple schools.

OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

47.7%, 51

36.7%, 40

6.4%, 7

3.7%, 4

2.8%, 3 2.8%, 3

Offers driver ed Does not offer driver

ed

District does not

serve students of

driving age

Has offered driver ed

in at least one of the

past five years but

does not plan to offer

it in 2022-23

Unsure if driver ed is

offered

Has not offered

driver ed in any of

the past five years

but does plan to offer

it in 2022-23

9

Exhibit 5: Availability of driver education to students

Source: OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

Nearly two-thirds of survey respondents whose districts oer driver education (32 superintendents or 65.3

percent) indicated that their districts oer the course during the school year only. e districts of 26.5 percent

of respondents (13 superintendents) oer driver education in both the school year and the summer.

Exhibit 6: Most districts offer driver education during the school year only

Source: OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

Student participation in driver education varies by district

Because driver education is not a required course for high school

students in Tennessee, the limited number of students who complete

their district’s driver education course do so as an elective or summer

school option. e rate of student participation varies from district to

district. Almost a quarter of survey respondents (24.1 percent or 13

superintendents) estimated that 11-20 percent of eligible students in

their district (i.e., students who are 15-18 years old) participate in driver

education oered by schools in the district each year. e majority of respondents indicated that 10 percent

or fewer eligible students in their districts elect to participate in the course, with 18.5 percent estimating 0-5

percent participation and 20.4 percent estimating 6-10 percent participation. Two respondents, however,

commented that all or almost all students in their district complete a driver education course during their

77.6%, 38

10.2%, 5

6.1%, 3 6.1%, 3

Available to all students who

live in the district and are

enrolled in the school where the

course is offered

Available to all students who

live in the district and are

enrolled in any school in the

district

Available to all students,

regardless of enrollment or

district residency

Other

65%, 32

27%, 13

6%, 3

2%, 1

School year only

Both school year and summer

Not sure

Summer only

With [academic] requirements

and dual [enrollment] college

courses, most students opt not

to take [driver education].

OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

10

sophomore year. In one of these districts, driver

education is taught as a component of the required

wellness and physical education courses. In the

other district, students who choose College and

Career Readiness as their graduation pathway have

the option to take driver education to fulll a

required elective credit during their sophomore year.

Exhibit 6: Almost a quarter of survey respondents estimated that 11-20 percent of their

district’s students take driver education through the district

Source: OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

Most driver education courses in Tennessee provide 30 hours of

classroom instruction and six hours of behind-the-wheel training

Currently, there are few specic requirements for driver education courses specied in state law or rule.

10

TCA

49-1-204, last amended in 1985, directs TDOE to promote and expand driver education and training courses

throughout state public schools. e law species only that these courses include instruction dealing with

the eects of the consumption of alcoholic beverages on driving abilities. e law also mandates an annual

appropriation of state funds for the driver education program, in addition to earmarking funds to TDOE and

TDSHS from litigation privilege taxes for the purpose of expanding driver education and promoting highway

safety.

11

(See p. 16 for more information on litigation privilege taxes.)

TCA 55-19-101 authorizes TDSHS to issue licenses for commercial driver training schools and licenses for

instructors in the schools. Under this authority, TDSHS operates the Driver Training and Testing Program

(DTTP), through which it establishes the terms and conditions required of driving schools and certied

instructors. In order for instructors that are certied under DTTP to administer the Tennessee road skills test,

the DTTP student must complete 30 hours of classroom instruction utilizing the current Tennessee Driver

License Manual and six hours of behind-the-wheel training (two hours may be completed using a simulator).

E

Public schools and instructors that are certied under DTTP are regulatated by TDSHS for their driver

education courses.

E

Behind-the-wheel training involves a student driver practicing skills on the road with a supervised instructor in the passenger seat.

[Enrollment in my district’s driver education course is]

fully maxed out in our school year option (paired with

Personal Fitness) and our summer oering. We have

added an additional teacher this year who is certied

and will double our summer enrollment next year.

OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

10, 18.5%

11, 20.4%

13, 24.1%

11, 20.4%

5, 9.3%

4, 7.4%

0-5% 6-10% 11-20% 21-50% 51-75% Over 75%

11

Most courses in Tennessee oer a combination of classroom instruction and behind-the-wheel training as

part of their driver education curriculum. e majority of private driver education agencies in Tennessee oer

courses that include 30 hours of classroom instruction combined with six hours of behind-the-wheel training,

in addition to a variety of other combinations.

F,12

According to the OREA survey of superintendents, most driver education courses oered by Tennessee school

districts (42.9 percent) include 30 hours of classroom instruction. Twenty percent of districts provide over

40 hours of classroom instruction. More classroom instruction may occur in districts where driver education

courses are taught during the school year over the course of a full semester as opposed to more condensed

summer courses.

Exhibit 7: Most school-based driver education courses consist of 30 hours of classroom

instruction

Source: OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

Most districts (43 percent) include six hours of behind-the-wheel training in their driver education courses.

Some districts (according to 22.4 percent of respondents) include over 10 hours of behind-the-wheel training

in their driver education courses.

Exhibit 8: Most school-based driver education courses consist of six hours of behind-the-

wheel training

Source: OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

F

TDSHS has jurisdiction over any entity that charges a fee for driver training. TDSHS Rules, Chapter 1340-03-07-.02(3) states that a driver education course shall

include classroom or online driver safety training of no less than four hours, which has been determined to meet or exceed the standards of the AAA, National Safety

Council, or other such nationally recognized curriculum approved by TDSHS. e American Driver and Trac Safety Education Association (ADTSEA) increased

the requirements for its driver education curriculum in 2017 to include 45 hours of classroom instruction and 10 hours of behind-the-wheel training, along with

12 hours of observation time. ADTSEA denes observation time as instructional time during which teen drivers observe a behind-the-wheel lesson and receive

perceptual practice in how to manage time and space for risk-reduction outcomes.

2.0%, 1

4.1%, 2

10.2%, 5

42.9%, 21

4.1%, 2

20.4%, 10

8.2%, 4

8.2%, 4

0 hours: behind-the-wheel training only

1-10 hours

11-29 hours

30 hours

31-40 hours

Over 40 hours

Unknown

Other

4.1%, 2

4.1%, 2

42.9%, 21

10.2%, 5

22.4%, 11

12.2%, 6

4.1%, 2

0 hours: classroom instruction only

1-5 hours

6 hours

7-10 hours

Over 10 hours

Unknown

Other

12

In nearly three-quarters of districts with driver education (73.5 percent or 36 survey respondents), the

course is taught by a district employee who also has additional responsibilities, such as teaching other classes,

coaching sports, or working in an administrative role. Eight superintendents (16.3 percent of respondents)

indicated that their districts employ teachers who are responsible for driver education only. In most districts,

driver education teachers use a curriculum provided by the district.

Exhibit 9: Driver education is usually taught by employees with other responsibilities

Source: OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

Most district superintendents think that their driver education

programs are effective

e majority of superintendent survey respondents (nearly

40 percent) felt that their district’s driver education program

is very eective at reducing trac accidents and fatalities

involving teen drivers, based on their observations. Another

31 percent rated their programs as extremely eective at doing

so. Superintendents referenced positive feedback from parents,

the ability of instructors to prepare students for the road, and a

perceived decrease in accidents among students as reasons for their positive ratings.

Exhibit 10: Most survey respondents rated their district’s driver education programs as

extremely or very effective

Source: OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

We have seen a decrease in accidents by

our students, and we hope to continue this

trend by educating students to be safe,

attentive, defensive drivers.

OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

31.3%, 15

39.6%, 19

25.0%, 12

2.1%, 1

2.1%, 1

Extremely effective

Very effective

Moderately effective

Slightly effective

Not at all effective

73.5%, 36

16.3%, 8

10.2%, 5

School/district employee with

other responsibilities (e.g.,

teacher, coach, administrative

assistant, etc.)

School/district employee

responsible only for driver

education

Other

73.5%, 36

16.3%, 8

10.2%, 5

School/district employee with

other responsibilities (e.g.,

teacher, coach, administrative

assistant, etc.)

School/district employee

responsible only for driver

education

Other

73.5%, 36

16.3%, 8

10.2%, 5

School/district employee with

other responsibilities (e.g.,

teacher, coach, administrative

assistant, etc.)

School/district employee

responsible only for driver

education

Other

13

While most survey respondents felt condent in their

program’s eectiveness, not all students may have access to

driver education due to certain barriers. Almost 37 percent

of respondents cited a lack of funding and 33 percent cited

a lack of eligible or willing instructors as barriers in their

districts. Others cited barriers such as a lack of interest from

students and/or parents, a lack of eective curriculum options, or a lack of a reliable vehicle.

Exhibit 11: Superintendents cited a lack of funding and lack of instructors as their main

barriers to providing adequate driver education

Source: OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

Most districts that do not offer driver education cite a lack of

funding as the main impediment

Nearly 40 percent of survey respondents (43 superintendents)

stated on the OREA survey that their districts have not oered

driver education in any of the past ve school years. ree of

those districts indicated that their districts do plan to oer the

course during the 2022-23 school year. Over 79 percent of the

districts that did not oer driver education at the time of the

survey have oered it at some point in the past, but it was longer than ve years ago.

Exhibit 12: Most districts that do not currently offer driver education have offered it in the past

Source: OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

Additional vehicles are needed along with

another instructor to serve the number of

requests from students for this course.

OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

If the state wants to fully fund a position

for [driver education], we will be more than

happy to add it.

OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

36.7%, 11

33.3%, 10

13.3%, 4

10.0%, 3

6.7%, 2

Lack of funding to help make courses more affordable for

students and districts

Lack of eligible and/or willing instructors

Other (e.g., lack of reliable vehicle)

Lack of interest from students and/or parents

Lack of effective curriculum options

79.1%, 34

11.6%, 5

9.3%, 4

Schools in my district do not currently

offer driver education but have in the

past (longer than five years ago).

Schools in my district have never

offered driver education.

Schools in my district do not currently

offer driver education and I am not

sure if driver education has ever been

offered in my district.

79.1%, 34

11.6%, 5

9.3%, 4

Schools in my district do not currently

offer driver education but have in the

past (longer than five years ago).

Schools in my district have never

offered driver education.

Schools in my district do not currently

offer driver education and I am not

sure if driver education has ever been

offered in my district.

79.1%, 34

11.6%, 5

9.3%, 4

Schools in my district do not currently

offer driver education but have in the

past (longer than five years ago).

Schools in my district have never

offered driver education.

Schools in my district do not currently

offer driver education and I am not

sure if driver education has ever been

offered in my district.

14

Funding concerns was the most common reason cited by survey

respondents (29 of 43 superintendents) for why their districts

do not oer driver education (e.g., costs of paying an instructor,

insurance, vehicle maintenance, etc.). Some said that they

have chosen to prioritize their funding for areas they view as of

greater importance, particularly those related to academics and

graduation requirements.

Fourteen survey respondents cited a lack of certied sta as the

reason driver education courses are not oered by their districts. Two

respondents commented that their districts stopped oering the course

after the teacher in their district certied to teach driver education

retired and there was no one else available. Some commented that it

is dicult to nd teachers certied to teach it, and one mentioned

that the certication process is costly and extensive. SBE policy 5.502

requires driver education teachers to hold a valid Tennessee educator license and complete at least 10 semester

hours of driver and trac safety education that includes basic and advanced driver and trac safety education

and rst aid and emergency medical service.

Other reasons mentioned by survey respondents included a lack

of student interest, issues with insurance liability on districts and

schools, logistical problems (e.g., scheduling, no one to monitor

students in the classroom while others are doing on-the-road

training, etc.), academic priorities (e.g., no room in schedule for

driver education due to other required courses), and the availability

of courses from external private agencies.

Exhibit 13: Superintendents cited a number of reasons for not offering driver education in

their districts

Source: OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

When asked if their districts had plans to oer driver education in

the future, over half of survey respondents (24 of 43 superintendents)

answered that their districts might oer it. e remaining respondents

indicated their districts do not plan to oer driver education in the

future. Ten superintendents commented that they would consider

adding the course if adequate funding were made available.

The already mandated requirements

for coursework in high school are

priority areas. Recurring cost is also

a consideration.

OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

We lost our teacher for driver

education and couldn’t get a

certied teacher, so we had to

stop the program.

OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

[Reasons for not oering driver

education include] cost of vehicles,

cost of insurance, [and the]

complexity of the structure of class.

OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

We pursued a lot of options, but the

challenges we met did not seem to

be worth the process [of oering a

driver education program].

OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

15

Exhibit 14: Over half of districts that do not currently offer driver education indicated that

they may do so in the future

Source: OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

District funding for driver education

Several factors feed into how much a driver education course

may cost a district to oer, including the costs of paying an

instructor, insurance, vehicle maintenance, and more. OREA

asked superintendents to estimate the total costs to their district

per year for driver education courses. irty-eight survey

respondents provided a broad range of estimates from $0 to

$453,807 in annual costs. Eleven superintendents were unsure

about costs.

Survey respondents were also asked to estimate the cost of driver education for their district per student.

irty-three superintendents estimated that it costs their districts anywhere from $0 to $2,000 per student to

provide driver education. Sixteen superintendents were not sure how much driver education costs per student.

Because the range of estimates provided on the superintendent survey was so broad, it is possible that the

respondents were unclear about how much driver education costs their districts.

Most districts with driver education offer courses to students free

of charge

Over three-quarters of survey respondents from districts that oer

driver education (38 of 49 superintendents) reported that their

districts oer the course free of charge to all students. In these cases,

any costs associated with the course are likely covered by the district

through its state or local funding. Five respondents’ districts charge

students $1-100, and two districts charge students $201-300.

ree respondents stated that driver education is oered as a free

elective during the regular school year, but students are charged a fee (ranging from $50-$150) for summer

courses to help oset the cost of teachers. One superintendent shared that while the district charges a fee for

driver education, no one is required to pay, which is the policy for all student fees in the district.

G

G

State Board of Education Rule 0520-01-02-.16 (a) prohibits requiring students to pay fees “as a condition of attending a public school or using its equipment while

receiving educational training.”

44.2%, 19

55.8%, 24

No – my district does not plan to offer

driver education in the future.

Maybe – my district might offer driver

education in the future.

We only subsidize the program through

local revenue. Students have an

opportunity to participate in the program

during the school year free of charge.

OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

The course is oered as an elective

within the available courses at the

high school. There are no fees

associated with this class and the

instructor is a licensed teacher with

the driver education endorsement.

OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

44.2%, 19

55.8%, 24

No – my district does not plan to offer

driver education in the future.

Maybe – my district might offer driver

education in the future.

16

According to State Board of Education Rules, Chapter 0520-01-

02-.16, districts may adopt a policy requesting, but not requiring,

certain school fees of students for activities that occur during

regular school days or in the summer.

13

Based on this rule, districts

cannot require students to pay a fee for driver education. In two

districts, an optional fee is assessed ($5 in one district and $20 in

another), but since few students pay the fee, the course is free to

the majority of students.

Exhibit 15: Most districts with driver education offer courses to students free of charge (n=49)

Source: OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

A portion of litigation privilege tax revenue is earmarked for

driver education

Driver education is not specically mentioned in Tennessee’s current BEP funding formula or the recently

passed TISA plan, but districts may choose to allocate K-12 funding formula resources toward driver

education. Additionally, a portion of litigation privilege tax revenue is earmarked for driver education.

Tennessee imposes privilege taxes on litigation instituted in all criminal and civil cases in the state, with the

amount dependent on the court and type of case.

14

See Appendix C for details on what courts and cases are

subject to litigation privilege taxes.

Tennessee state law allocates a percentage of litigation privilege tax revenue to 14 dierent funds, grants,

and programs.

H

e dedication of a portion of such revenues toward driver education was rst established in

1981 with the passage of Public Chapter 488. At that time, 11.31 percent of litigation privilege tax revenues

were allocated to driver education, with 75 percent of the amount allocated to TDOE and the remaining

25 percent allocated to TDSHS.

15

e General Assembly reduced the percentage of litigation privilege tax

revenues earmarked for driver education through subsequent amendments to the law before the current

percentage allocation was set in 2005.

16

Current law mandates that 4.4430 percent of litigation privilege tax revenue be credited to a separate reserve

account to be split between TDOE (75 percent) and TDSHS (25 percent) to promote and expand driver

education through Tennessee public schools and to promote safety on the highways.

17

Additionally, 2.7747

H

See Appendix D for a breakdown of all litigation privilege tax allocations.

During the school year, the fees are

minimal; however, when driver ed is

taken during the summer, a fee of

$150 is assessed.

OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

77.6%, 38

10.2%, 5

0.0%, 0

4.1%, 2

2.0%, 1

0.0%, 0

6.1%, 3

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

$0 - Driver

education is

offered free to

all students

$1-100 $101-200 $201-300 $301-400 Over $400 The cost varies

by school

17

percent of the litigation privilege tax proceeds are credited to a separate general fund reserved for use only by

TDOE to promote and expand driver education.

18

In FY 2022, TDOE received an average of $87,511.34 per month through litigation privilege taxes for

an annual total of $1,050,136.10. TDSHS received an average of $15,916.82 per month for a total of

$191,001.84.

Exhibit 16: Distribution of litigation privilege tax proceeds designated to promote and

expand driver education and/or to promote highway safety | FY 2022

Source: Tennessee Department of Revenue.

e law does not specify how these funds must be used to promote and expand driver education and promote

highway safety. TDSHS uses its allocated funds to promote safety education in schools and promote highway

safety by purchasing promotional materials and paying for salaries and benets of employees that assist in

these areas.

TDOE distributes litigation privilege tax revenue to districts that oer driver education to use at their

discretion. To determine how funds will be dispersed, TDOE divides the total amount of revenue the

department receives ($1,050,136.10 in FY 2022) by the total number of students enrolled in driver education

courses across the state, as reported by districts through the department’s Education Information System

(EIS). e resulting amount is used to distribute funding to districts based on the number of students enrolled

in the districts’ driver education courses.

For example, the per-student allocation for all students enrolled in driver education in Tennessee during the

2021-22 school year was $86.89. Four students were enrolled in Union County driver education in 2021-22,

so the district received a total of $347.56 from the state. In Rutherford County that year, 3,141 students were

enrolled in driver education, resulting in $272,921.49 for the district. See Appendix E for a complete list of

districts receiving funding from litigation privilege taxes for driver education.

TDOE TDSHS

Collection month 67-4-606(a)(14)

100% of the 2.7747% of privilege

tax proceeds credited to separate

general fund reserve to be used

only by TDOE to promote and

expand driver education

67-4-606(a)(2)(A)

75% of the 4.4430% of privilege tax

proceeds designated to promote

and expand driver education and

highway safety

67-4-606(a)(2)(B)

25% of the 4.4430% of privilege tax

proceeds designated to promote

and expand driver education and

highway safety

July 2021 $43,936.56 $52,765.20 $17,588.40

August 2021 $39,710.77 $47,690.27 $15,896.76

September 2021 $41,951.34 $50,381.07 $16,793.69

October 2021 $39,018.59 $46,859.01 $15,619.67

November 2021 $39,335.81 $47,239.98 $15,746.66

December 2021 $40,378.45 $48,492.12 $16,164.04

January 2022 $33,572.28 $40,318.32 $13,439.44

February 2022 $35,154.09 $42,217.98 $14,072.66

March 2022 $39,096.61 $46,952.71 $15,650.90

April 2022 $48,530.61 $58,282.38 $19,427.46

May 2022 $35,261.80 $42,347.32 $14,115.77

June 2022 $41,183.68 $49,459.15 $16,486.38

$477,130.59 $573,005.51

FY 2022 total $1,050,136.10 $191,001.84

18

Exhibit 17: Ten districts with highest number of students participating in driver education |

2021-22

Source: Tennessee Department of Education.

Districts that do not oer driver education do not receive such revenues. Most of the survey respondents

whose districts do not oer driver education indicated that they do not receive dedicated state funding for

it.

I

Because the driver education funds allocated through litigation privilege taxes are dependent on student

enrollment, these districts would not receive funding without oering the course.

Two respondents to the superintendent survey indicated that their districts oer driver education, but they

were not on the list of districts receiving funding from litigation privilege taxes. According to TDOE, if a

district uses an incorrect course code for driver education in the EIS (e.g., using the course code for study

hall instead), their students would not be counted for funding. It is not clear if this error applies to these two

survey respondents.

Because these funds are dependent on litigation privilege tax revenue (which changes from year to year) and

are allocated on a per student basis among all districts oering driver education, district allocations uctuate.

J

An increase in the number of students enrolled in driver education in a year when litigation privilege tax

revenues remained the same or decreased would lower the amount of funding received by districts.

Districts also use other funding sources to offset the cost of

driver education

In districts where the allocations received from litigation privilege

taxes do not fully fund the driver education program, other funding

sources must be utilized. As with other programs, districts may

allocate local funding such as local tax revenue or city or county

allocations to cover any additional costs of driver education. In some

cases, the cost of driver education may be supplemented in other

ways, such as charging fees to students or acquiring a donated vehicle

through a local dealership.

Additional funding may also be available to students or districts in the form of private grants. For example, the

Hagerty Drivers Foundation, launched by the Hagerty Insurance Agency and Drivers Club in 2021, provides

programs and nancial support in car culture, education, and innovation. e foundation’s License to the

Future program oers grants of up to $500 to young drivers to cover the cost of driver education. e grant is

I

Seven superintendents indicated that they were unsure if their districts received state funding earmarked for driver education. None of the seven districts appeared

on the list of districts that received a portion of the litigation privilege tax revenue.

J

See Appendix F for the estimated annual litigation privilege tax revenue for each year since 2017, as projected in Tennessee state budget documents.

District Student count Allocation

Rutherford County 3,141 $272,921.49

Knox County 858 $74,551.62

Sevier County 571 $49,614.19

Washington County 438 $38,057.82

Bradley County 370 $32,149.30

Cocke County 317 $27,544.13

Greene County 281 $24,416.09

Bristol City 279 $24,242.31

Bedford County 277 $24,068.53

Dyer County 266 $23,112.74

Our district receives a car for

temporary use during the driver

education course. The vehicle is

donated by a local dealership.

The district supplies the gasoline

and oil change.

OREA survey of superintendents, July 2022.

19

open to students ages 14-18 who apply through an online form in which they submit either a 300-word essay

or a one-minute video answering the question, “Why are you excited to drive?” e program provided 175

grants in 2020 and approximately 200 grants in 2021 to students across the United States and Canada.

Other potential funding sources for driver education

Title I

One alternative source of funding that has been proposed by lawmakers to help cover or oset the cost

of driver education is Title I funds. Title I was originally passed as part of the Elementary and Secondary

Education Act of 1965, last reauthorized as the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) of 2015. e program

provides nancial assistance to districts for children from low-income households to help ensure that all

children meet challenging state academic standards and receive fair, equitable, high-quality education. Title

I allocations are determined by combining four formulas to allocate funds to districts with more signicant

numbers and higher concentrations of students in poverty.

All school districts in Tennessee receive Title I funding. In FY 2021, the state’s school districts were allocated

$304 million from Title I. School districts have some discretion in how their Title I funds are distributed,

operating either as targeted assistance or schoolwide programs. Targeted assistance schools identify students

who are at risk of not meeting the state’s content and performance standards and provide individualized

instructional programs to the identied students to assist them in meeting the state’s standards. In a Title I

Targeted Assistance Program, funds may be spent on allowable Title I activities for participating, targeted Title

I students, their teachers, and families. Activities and interventions must be aligned with the program plan for

providing services to eligible students based on educational needs.

Schools in which children from low-income families make up at least 40 percent of enrollment are eligible to

use Title I funds to operate schoolwide programs that serve all children in the school to raise the achievement

of the lowest-achieving students. In a Title I Schoolwide Program, funds may be spent on allowable Title I

activities for any student, teacher, and family of students enrolled in the school. Activities and interventions

must be aligned with the schoolwide plan, strategies, and interventions based on a comprehensive needs

assessment.

Driver education availability and participation in Tennessee Title I schools

As of July 2022, there were 183 designated Title I schools serving students of driving age (i.e., students in

grades 10-12) in 67 Tennessee school districts.

K

TDOE does not collect data on which schools oer driver

education, only districts, so an accurate number of Title I schools that oer driver education is unavailable.

On the OREA survey of superintendents, 26.5 percent of respondents stated that driver education is oered

in Title I schools in their districts.

On OREA’s survey of Title I school principals, 41 percent

of respondents (representing 25 schools) indicated that their

schools have oered driver education in at least one of the past

ve school years and are oering it in the 2022-23 school year.

L

All but one of those principals stated that their school oers

the course during the school year only, not in the summer. Just

over half of respondents (55.7 percent or 34 schools) shared that

their schools have not oered driver education in any of the past

ve school years and they are not oering it in 2022-23.

K

See Appendix G for a list of all Title I schools in Tennessee that serve students of driving age (i.e., students in grades 10-12).

L

OREA distributed the survey to principals of Title I schools that serve students of driving age (i.e., grades 10-12).

Although we have a driver education

program in our school, the school

system does not oer it. We partner

with a local program and allow them to

use our facility to hold classes.

OREA survey of Title I principals, September 2022.

20

Exhibit 18: Over half of the Title I schools represented by respondents on the OREA survey

do not offer driver education

Source: OREA survey of Title I principals, September 2022.

e number of Title I schools that oer driver education has remained steady since 2017-18, when 23 of

the survey respondents said their schools oered the program. Twenty-ve Title I schools are oering driver

education during the 2022-23 school year. Two principals shared that their schools did not oer the course

during one or both of the 2019-20 or 2020-21 school years due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Exhibit 19: Driver education availability has remained steady in Title I schools since 2017-18

Source: OREA survey of Title I principals, September 2022.

Nearly one-third of the principals whose schools oer driver education indicated that 11-20 percent of their

eligible students (i.e., students age 15-18) participate. Almost a quarter of respondents (six principals or 24

percent) stated that 21-50 percent of their students participate

in driver education. Two principals shared that driver education

is a requirement at their schools, so their participation rate is

high. Several respondents stated that their participation rate

would likely be higher, but availability is limited due to lack of

sta or schedule conicts.

41.0%, 25

55.7%, 34

1.6%, 1 1.6%, 1

Offers driver ed Does not offer driver ed Has offered driver ed in at least

one of the past five years but

not in 2022-23

Has not offered driver ed in any

of the past five years but does

offer it in 2022-23

23

25

24

23

25 25

2017-18 2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22 2022-23

We are a small school whose primary

mission is to graduate students on time,

and they may not be able to t [driver

education] into their schedules.

OREA survey of Title I principals, September 2022.

21

Exhibit 20: Most Title I principals estimated an 11-20 percent participation rate for driver

education at their schools

Source: OREA survey of Title I principals, September 2022.

Six principals whose Title I schools oer driver

education shared that they have encountered some

barriers to providing adequate driver education to

students. Four of these respondents cited a lack of

eligible and/or willing instructors as a barrier, with

one echoing the thoughts of a superintendent who

described the certication process for driver education

as costly and extensive.

Possibility of using Title I funds for driver education

According to TDOE, a school may use Title I “to support any reasonable activity designed to improve its

educational program as long as it is consistent with the school’s needs and plan.” A school’s planning team

prioritizes identied needs and determines where funds are best utilized. A TDOE representative stated that if

driver education is identied as a priority need, it is allowable to le that expense under Title I. e department

does not recommend, however, referring to an automobile used for driver education as education materials,

instead recommending budgeting the expense in the same way it does for other regular instructional equipment.

On the OREA survey of superintendents, nearly 94 percent of respondents (46 superintendents) whose

districts oer driver education said that their districts

do not currently use Title I funds to cover or oset the

cost of the course. e remaining three respondents

were not sure if their district used these funds. On

the survey of Title I principals, nearly 57 percent of

respondents whose schools oer driver education (13

principals) stated that their schools do not use federal

Title I funds to cover or oset the cost of driver education for their students. e remaining respondents (43.5

percent or 10 principals) were unsure if their schools did.

12.5%, 3 12.5%, 3

33.3%, 8

25.0%, 6

8.3%, 2 8.3%, 2

0.0%, 0

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0-5% 6-10% 11-20% 21-50% 51-75% 76-99% 100% (Driver

education is

required for all

students)

The teacher who teaches driver education

is also the P.E. teacher. We cannot provide

adequate sections of driver education due to the

teacher also teaching other classes. The solution

would be for the [state] to fund a position for

driver education.

OREA survey of Title I principals, September 2022.

Our schools are providing every other service

(counseling, enrichment, remediation, care

closets, food pantries, etc.). [Driver education]

is a liability that should be addressed in the

community, not the school.

OREA survey of Title I principals, September 2022.

22

Several respondents on the Title I principals survey were unsure of the cost of driver education for their

school, likely because the funding is allocated from multiple funding sources at the district level. Eighteen

principals said that they paid for the program using funding allocated by the district that is earmarked

specically for driver education. Another four said that they use local donations or resources such as cars

donated by a local dealership or oil changes performed by a CTE class.

Regardless of what funding is being used, the Title I principals survey echoed the responses on the survey of

superintendents regarding the cost of driver

education to their students. Most Title I school

principals whose schools oer driver education

(87 percent or 20 respondents) shared on the

survey that their schools do not charge students

to take the course. ree principals indicated

that their school charges a $1-100 fee for the

course, which two said was $5 at their schools.

M

Title I schools without driver education

irty-four Title I school principals shared on the survey that their school does not currently oer driver

education and has not oered it in any of the past ve school years. Of those respondents, 14 of their schools

(41.2 percent) have oered the course in the past, but longer than ve years ago. Eleven principals (32.4

percent) stated that their schools have never oered driver education.

Similar to responses on the survey of district superintendents,

most principals whose Title I schools do not oer driver

education cited a lack of funding as a reason for not oering

the course. Twelve respondents stated that they do not have

enough eligible and/or willing instructors to sta the program,

and ve said that their district as a whole does not oer driver

education.

Exhibit 21: Lack of funding was the top reason cited by Title I principals for not offering

driver education at their schools

Source: OREA survey of Title I principals, September 2022.

M

No respondents indicated that their schools charge higher fees. Respondents could have also selected $101-200, $201-300, $301-400, $401-500, and over $500

from the list of answer choices. No respondents indicated that their schools charge over $100.

Driver education is needed at our school. We are in a

very low socio-economic area and some of the parents

do not provide training for their kids. In order for these

kids to become a success in life, they need to know how

to drive and we are glad to provide the training for them.

OREA survey of Title I principals, September 2022.

We would love to oer driver education

and other services like this. Funding is an

issue, but if we can overcome this hurdle

we would oer it in a heartbeat.

OREA survey of Title I principals, September 2022.

,

23

Most principals whose schools do not currently oer driver education (20 respondents or 58.8 percent)

indicated that their schools do not plan to oer driver education in the future. Almost a third of respondents

(11 principals) stated that their schools might oer the course someday.

Exhibit 22: Most Title I schools that do not currently offer driver education do not plan to

offer it in the future

Source: OREA survey of Title I principals, September 2022.

Nearly three-quarters of survey respondents (73.5 percent

or 25 principals) whose Title I schools do not oer driver

education stated that the course is not oered anywhere in

their districts. Six principals were not sure if it was oered

anywhere in the district, and three indicated that other schools

in their districts oer driver education but only to students

enrolled in those schools.

Exhibit 23: Most Title I schools that do not offer driver education are in districts that do not

offer the course

Source: OREA survey of Title I principals, September 2022.

8.8%, 3

58.8%, 20

32.4%, 11

Yes – my school has plans to

offer driver education in the

future.

No – my school does not plan to

offer driver education in the

future.

Maybe – my school might offer

driver education in the future.

We would not use any of our current sta

or resources [for driver education]. If the

state wanted to fund the equipment and

stang, we’d be willing to oer it.

OREA survey of Title I principals, September 2022.

73.5%, 25

17.6%, 6

8.8%, 3

No driver education is offered

anywhere in my district.

I’m not sure if driver education is

offered anywhere in my district.

Other schools in my district offer

driver education but only to

students enrolled in those

schools.

73.5%, 25

17.6%, 6

8.8%, 3

No driver education is offered

anywhere in my district.

I’m not sure if driver education is

offered anywhere in my district.

Other schools in my district offer

driver education but only to

students enrolled in those

schools.

8.8%, 3

58.8%, 20

32.4%, 11

Yes – my school has plans to

offer driver education in the

future.

No – my school does not plan to

offer driver education in the

future.

Maybe – my school might offer

driver education in the future.

73.5%, 25

17.6%, 6

8.8%, 3

No driver education is offered

anywhere in my district.

I’m not sure if driver education is

offered anywhere in my district.

Other schools in my district offer

driver education but only to

students enrolled in those

schools.

73.5%, 25

17.6%, 6

8.8%, 3

No driver education is offered

anywhere in my district.

I’m not sure if driver education is

offered anywhere in my district.

Other schools in my district offer

driver education but only to

students enrolled in those

schools.

24

Dual enrollment grants

OREA was also asked to explore the possibility of using dual enrollment grants to cover the cost of driver

education courses if oered by postsecondary institutions. Dual enrollment courses are postsecondary courses

open to high school students who may enroll and earn college-level credits while still in high school. Dual

enrollment courses are either oered at a college or university or taught by a member of a college faculty at

a high school or online. Upon completion of a dual enrollment course, students can earn college credits that

can be used toward a postsecondary credential. High school credit is awarded based on local policy. However,

districts must accept dual enrollment courses aligned with high school graduation requirements according to

SBE’s high school policy.

e dual enrollment grant is one of the Tennessee Education Lottery Scholarships, and the grant provides

funding for dual enrollment tuition and fees. Students receive funding for one dual enrollment course per

semester, with funding for an additional course per semester if they meet the minimum HOPE Scholarship

academic requirements at the time of dual enrollment.

TDOE is unaware of any dual enrollment driver education programs being oered at Tennessee postsecondary

institutions, and TBR is unaware of any institutions oering driver education courses. If a postsecondary

institution were to begin oering driver education courses eligible for dual enrollment grants, then students

could choose driver education within their limit of 10 dual enrollment courses. Students would also have to

meet certain academic requirements to use dual enrollment grant funding for a driver education course.

In the fall semester of 2021, the most common dual enrollment courses included English, communication,

math, history, and other general education or non-general education academic courses, all of which align with

postsecondary degree requirements. Driver education courses do not align with any postsecondary degree

requirement, and representatives from TDOE do not believe dual enrollment grants can currently be applied

toward the cost of a driver education course, should one be oered through a postsecondary institution in the

future. A representative from TBR stated that if an institution were to oer driver education, it would be possible

to pay for it with dual enrollment grants, but community colleges are unlikely to oer driver education courses

because the course does not currently meet the requirements of any postsecondary degree program.

According to the OREA survey of superintendents, there have been no known instances to date of a school

district working with a local college or university for driver education. ree respondents indicated that they

have plans to consider such a partnership in the future.

Private driver education companies are popular

alternatives to public school programs

TDSHS operates the Driver Training and Testing Program (DTTP), through which it establishes the terms

and conditions required to operate as a licensed driver training enterprise or driver testing program and/

or a driving instructor’s certication.

N

As of May 2022, there were 18 approved driver training and testing

programs operating in 10 Tennessee counties. ese programs

provide classroom instruction and behind-the-wheel training for

students of all ages, but they predominantly serve teenage drivers

preparing to test for their driver license. State law

19

species

requirements for the operation of commercial driver training

schools and licenses for instructors in these schools.

O

See Appendix

H for more information on these requirements.

N

For more information on the DTTP, see p.10.

O

According to TCA 55-19-109, commercial driver training schools do not include any person giving driving lessons free of charge, employers maintaining driver

training courses for their employees only, or to schools or classes conducted by colleges, universities, or high schools for regularly enrolled full-time students as part of

the normal program of those institutions.

Students in this area receive driver

education with private companies. We

do not have the stang at this time to

be able to support this initiative.

OREA survey of Title I principals, September 2022.

25

e average minimum fee for these programs (typically including 30 hours of classroom instructional time

and six hours of behind-the-wheel training) is $462.67.

Exhibit 24: TDSHS-approved driver training and testing programs

Notes: *Students from other counties may attend these programs. ^Additional fees may apply.

Source: Tennessee Department of Safety and Homeland Security.

Most respondents to the OREA superintendent survey stated that their districts have never partnered with a

private driver education company and do not plan to in the future. e district of one respondent has worked

with a private company in the past but does not currently work with one.

Policy options

The General Assembly may wish to consider asking TDSHS to add

a question to rst-time driver license applications asking if the

applicant had completed a voluntary driver education program.

OREA did not identify any existing studies of the eectiveness of driver education programs in Tennessee.

A study of eectiveness would require data on the number of teen drivers who have completed a driver

education course. Driver license applications do not ask applicants if they have completed a driver education

course, and the state does not collect this information in any other way. If the department added a question

to applications to gather this information, it would enable the state to track the percentage of teen drivers

who are participating in these programs and give a better idea of the correlation between driver education and

improved driver safety.

School name County Student fees*

A.B. Driving School Shelby $650

Behind the Wheel Driving Academy Hamilton $420-620

Brentwood Driving Training Wilson & Davidson $525

Caswell Group Driving School Shelby $525-625

Drive 4 Life Academy, Inc. Knox $455-2,000

Drive-Rite Driving School Knox $374

Expert Driving School Davidson $500

Go Driving Academy Montgomery $300-450

Haman’s New Drivers Hamilton $439-639

Maxwell Motorsport & Driving School Shelby $625-825

Pitner Driving School Shelby $595-725

Ready 2 Drive LLC Sumner & Wilson $495-695

Safe Driving, Inc. Anderson $375

Spanky’s Driving Academy Wilson $550

Teen Driver Academy Madison $450

The Driving Center Anderson $375

Upper Cumberland Human Resource Agency Putnam $300

Workforce Essentials, Inc. Montgomery $375

26

The General Assembly may wish to consider increasing the

percentage of litigation privilege tax revenue that goes toward

driver education in order to increase access and improve

affordability for all students and school districts.

Tennessee state law allocates a percentage of litigation privilege tax revenue to 14 dierent funds, grants, and

programs.

P

Current law

20

mandates that 4.4430 percent of revenue collected from litigation privilege tax

revenue be credited to a reserve account to be split between TDOE (75 percent) and TDSHS (25 percent)

to promote and expand driver education through Tennessee public schools and to promote safety on the

highways.

Q

Prior to 2005, the percentage of litigation privilege tax revenues earmarked for such purposes was higher. In

1981, when a portion of the revenues was rst earmarked for such purposes, the General Assembly set the

percentage at 11.31 percent. e General Assembly reduced the percentage through subsequent amendments

to the law before the current percentage allocation was set in 2005.

21

If the percentage were increased, more funding would become available for school districts to use for driver

education. However, assuming no change to the litigation privilege tax, increasing the percentage directed

to TDOE for driver education would mean a reduction in funding available for the other funds, grants, and

programs that receive a portion of litigation privilege tax revenues.

TDOE may wish to gather more information regarding driver

education, including availability and cost of courses at individual

high schools.

TDOE collects the number of students enrolled in driver education in each district so that it can distribute

funds from litigation privilege taxes as required by law.

R

e department does not collect information

regarding the cost of driver education for students or the district nor does it track the individual high schools

that oer it. Increased data collection would provide a greater ability to track the availability and aordability

to all students, including those enrolled in Title I schools.

TDOE may wish to consider giving districts the chance to review

driver education numbers before distributing funds.

On the OREA survey of superintendents, two respondents indicated that their districts oer driver education,

but the districts were not on the list of those that received funding from the state’s allocation of litigation

privilege tax revenue. TDOE pulls the number of students enrolled in driver education in each district by the

course code specic to driver education in EIS, the department’s student system of record. If a district uses a

dierent code (e.g., study hall), students are not recorded as enrolled in driver education and thus the district

does not receive funding. TDOE might consider sending a list of driver education student counts to the

districts for their review prior to allocating funding each year. Districts would have the opportunity to make

corrections and receive any funding that might otherwise be missed.

P

See Appendix D for a full breakdown of litigation privilege tax allocations.

Q

Additionally, state law at TCA 67-4-606(a)(14) mandates that 2.7747 percent of revenue collected from litigation privilege tax proceeds is reserved in the general

fund for use only by TDOE to promote and expand driver education.

R

See p. 16 for more information on litigation privilege taxes.

27

Appendix A: Tennessee graduated driver

license program

Since 2001, the state has implemented the graduated driver license (GDL) program, a multi-tiered program

designed to ease young novice drivers into full driving privileges as they become more mature and develop

their driving skills. GDL programs rst became popular across the United States in the 1990s. Under

Tennessee’s GDL program, drivers must be at least 15 years old and pass a written examination on basic

driving laws in order to receive a learner permit. ose with a learner permit may drive with a licensed driver