NOTE FROM THE EDITORS

This handbook is a free resource for

people in prison who wish to file a federal

lawsuit addressing poor conditions in

prison or abuse by prison staff.

It also contains limited general information about the United States

legal system. This handbook is available for free to anyone: prisoners,

families, friends, activists, lawyers and others.

We hope that you find this handbook helpful, and that it provides

some aid in protecting your rights behind bars. Know that those of us

on the outside are humbled and inspired by the incredible work so

many of you do to protect your rights and dignity while inside. As you

work your way through a legal system that is often frustrating and

unfair, know that you are not alone in your struggles for justice.

Good luck!

Rachel Meeropol

Ian Head

Chinyere Ezie

The Jailhouse Lawyers Handbook, 6

th

Edition.

Revised in 2021. Published by:

The Center for Constitutional Rights

666 Broadway, 7

th

Floor

New York, NY 10012

The National Lawyers Guild,

National Office

P.O. Box 1266

New York, NY 10009-8941

Available on the internet at: http://jailhouselaw.org

Cover art by Kevin "Rashid" Johnson

Layout and design by Emily Ballas

We would like to thank:

All of the jailhouse lawyers who have

sent comments, recommendations, and

corrections for the handbook, all those

who have requested and used the

handbook, and who have passed their

copy on to others inside prison walls.

Special thanks to Mumia Abu-Jamal

for his continued support of the JLH.

The original writers and editors of the

handbook (formerly the NLG Jailhouse

Lawyers Manual), Brian Glick, the Prison

Law Collective, the Jailhouse Manual

Collective, and Angus Love. Special

thanks to Carey Shenkman for his work

on the 2021 revision and to Paul Redd,

John Boston, and Alexander Reinert

for their review of this edition.

Thanks to Claire Dailey and

Lisa Drapkin, for administrating the

mailing program at CCR and NLG.

The dozens of volunteers who have

come to the Center for Constitutional

Rights and National Lawyers Guild

offices every week since 2006 to

mail handbooks to people inside

prison, especially Merry Neisner,

Torie Atkinson, Dena Weiss,

Miriam Edwin, Magaly Pena,

Damian Van Denburgh, Nora Chanko,

Perri Fagin, Clare Spitzer, and

Daniel McGowan. Additional thanks

to all those who contributed to the new

State Appendix, along with Alice S. and

Daniel L. who contributed to Appendix J.

Jeff Fogel and Steven Rosenfeld

for their work defending the handbook

in Virginia.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER:

This handbook was written by

Center for Constitutional Rights

staff. The information included in the

handbook is not intended as legal advice

or representation, and you should not

rely upon it as such. We cannot guarantee

the accuracy of this information nor

can we guarantee that all the law and

rules inside are current, as the law

changes frequently.

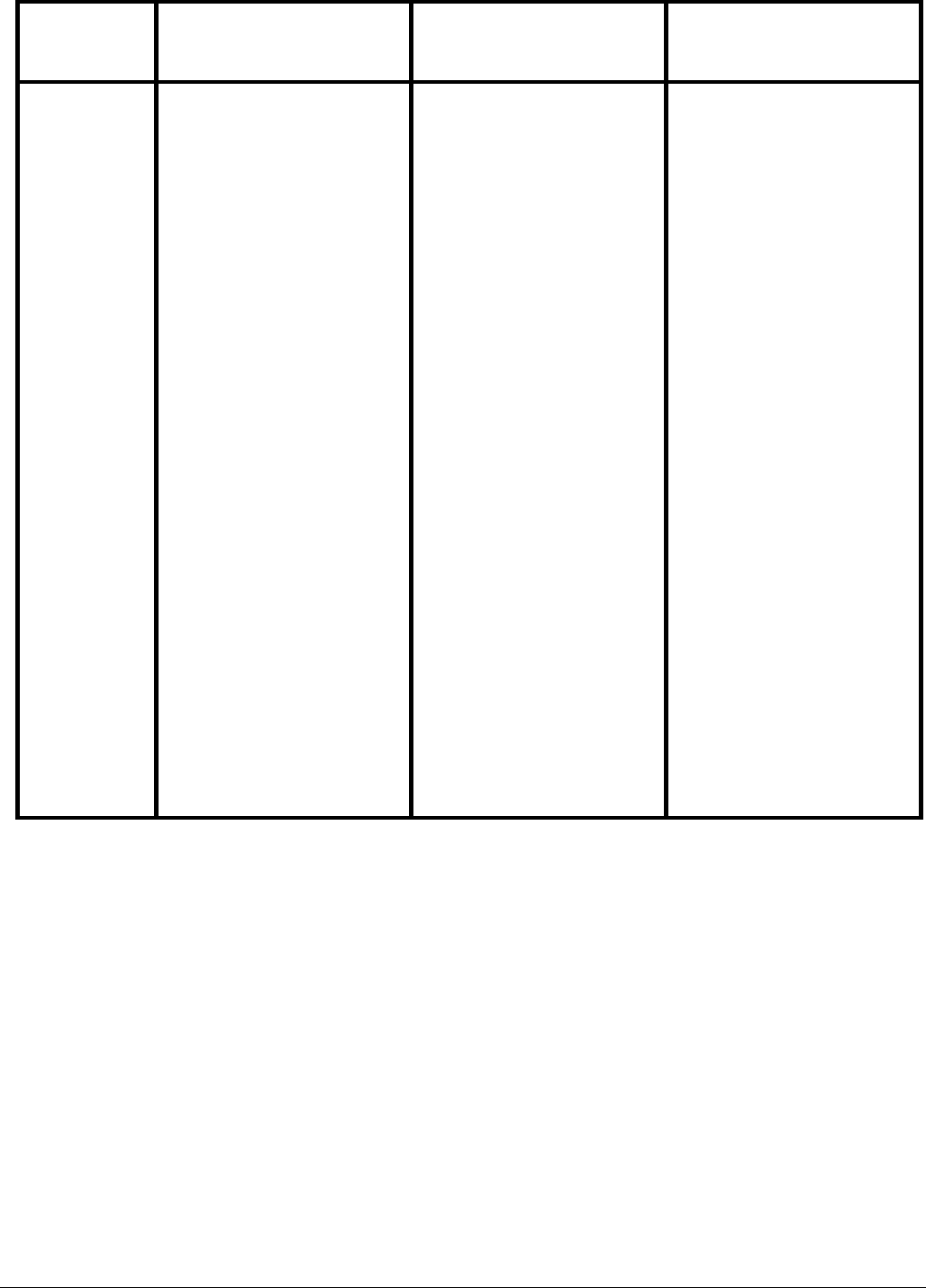

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE: How to Use the JLH 1

A. What Is This Handbook? ......................................................................................................................................... 1

The Importance of “Section 1983” ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 1

B. How to Use This Handbook .................................................................................................................................... 1

C. Who Can Use This Handbook ................................................................................................................................ 2

1. Prisoners in Every State Can Use This Handbook ............................................................................................................................................................. 2

2. Prisoners in Federal Prison Can Use This Handbook ........................................................................................................................................................ 2

3. Prisoners in City or County Jails Can Use This Handbook .............................................................................................................................................. 3

4. Prisoners in Private Prisons Can Use This Handbook ....................................................................................................................................................... 3

D. Why to Try and Get a Lawyer ................................................................................................................................ 3

E. A Short History of Section 1983 and the Struggle for Prisoners’ Rights ..................................................... 4

F. The Uses and Limits of Legal Action ..................................................................................................................... 5

CHAPTER TWO: Overview of Types of Lawsuits and the Prison Litigation Reform Act 7

A. Section 1983 Lawsuits ............................................................................................................................................. 7

1. Violations of Your Federal Rights .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 7

2. “Under Color of State Law” ..................................................................................................................................................................................................... 8

B. State Court Cases ...................................................................................................................................................... 9

C. Federal Torts Claims Act (FTCA) ........................................................................................................................... 9

1. Who You Can Sue ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 9

2. Administrative Exhaustion .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 10

3. Types of Torts ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 10

a. Negligence ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 11

b. Intentional Torts - Assault and Battery ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 11

c. False Imprisonment ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 11

d. Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 11

4. Damages in FTCA Suits ......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 11

5. The Discretionary Function Exception .............................................................................................................................................................................. 12

D. Bivens Actions and Federal Injunctions ............................................................................................................. 12

1. Who is acting under color of federal law? ........................................................................................................................................................................ 12

2. Unconstitutional Acts by Federal Officials Subject to Bivens Claims ......................................................................................................................... 13

3. Federal Injunctions ................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 13

E. Brief Summary of the Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA) .......................................................................... 14

1. Injunctive Relief ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 14

2. Exhaustion of Administrative Remedies ........................................................................................................................................................................... 14

3. Mental or Emotional Injury ................................................................................................................................................................................................... 14

4. Attorney’s Fees ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 14

5. Screening, Dismissal, and Waiver of Reply ....................................................................................................................................................................... 14

6. Filing Fees and the Three Strikes Provision ..................................................................................................................................................................... 14

CHAPTER THREE: Your Rights In Prison 15

A. Your First Amendment Right to Freedom of Speech and Association ...................................................... 15

1. Access to Reading Materials ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 16

2. Free Expression of Political Beliefs .................................................................................................................................................................................... 18

3. Limits on Censorship of Mail ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 19

a. Outgoing Mail ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 19

b. Incoming Mail ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 20

c. Legal Mail ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 20

4. Access to the Telephone ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... 20

5. Access to the Internet ........................................................................................................................................................................................................... 21

6. Your Right to Receive Visits from Family and Friends and to Maintain Relationships in Prison. ........................................................................ 21

a. Access to Visits ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 22

b. Caring for Your Child in Prison .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 23

B. Your Right to Practice Your Religion .................................................................................................................. 23

1. Free Exercise Clause .............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 23

2. Establishment Clause ............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 24

3. Fourteenth Amendment Protection of Religion .............................................................................................................................................................. 25

4. Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) and Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA) ......................................... 25

5. Common Issues Related to Religious Accommodations ............................................................................................................................................... 25

C. Your Right to be Free from Discrimination ....................................................................................................... 26

1. Freedom from Racial Discrimination .................................................................................................................................................................................. 27

2. Freedom from Sex and Gender Discrimination ............................................................................................................................................................... 28

a. The “Similarly Situated” Requirement ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 28

b. Proving Discriminatory Intent ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 28

3. Freedom from Other Forms of Discrimination ................................................................................................................................................................ 29

D. Your Procedural Due Process Rights Regarding Punishment,

Administrative Transfers, and Segregation ............................................................................................................ 29

1. Due Process Rights of People in Prison ............................................................................................................................................................................ 30

2. Transfers and Segregation .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 31

E. Your Right to Privacy and to be Free from Unreasonable Searches and Seizures .................................. 32

1. Your Fourth Amendment Rights related to Searches .................................................................................................................................................... 32

2. Your Fourteenth Amendment Right to Medical Privacy ............................................................................................................................................... 33

F. Your Right to be Free from Cruel and Unusual Punishment ......................................................................... 33

1. Your Right to Be Free from Physical Brutality and Sexual Assault by Prison Staff ................................................................................................ 34

a. Use of Excessive Force and Physical Brutality by Prison Officials .................................................................................................................................................................................... 34

b. Sexual Assault and Abuse by Prison Officials ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 35

c. Sexual Harassment and Verbal Abuse by Guards ................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 35

d. “Consensual” Sex between Prisoners and Guards ................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 36

e. Challenging Prison Supervisors and Prison Policies ............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 36

2. Your Right to Be Free from Physical and Sexual Assault by Other Incarcerated People ...................................................................................... 37

a. Failure to Protect from Prisoner Sexual Assault .................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 37

b. Failure to Protect from Prisoner Physical Abuse .................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 37

3. Your Right to Decent Conditions in Prison ...................................................................................................................................................................... 37

4. Your Right to Medical Care .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 40

a. Serious Medical Need .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 40

b. Deliberate Indifference ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 41

c. Causation ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 41

d. The COVID-19 Pandemic ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 42

G. Your Right to Use the Courts ............................................................................................................................... 42

1. The Right to Talk and Meet with Lawyers and Legal Workers .................................................................................................................................... 43

2. The Right to Access to a Law Library ................................................................................................................................................................................. 43

3. Getting Help from a Jailhouse Lawyer and Providing Help to Other Prisoners ...................................................................................................... 44

4. Dealing with Retaliation ........................................................................................................................................................................................................ 45

H.

Issues of Importance to Women in Prison ....................................................................................................... 46

1. Medical Care ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 46

a. Proper Care for Women in Prison ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 46

b. Medical Needs of Pregnant Women ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 46

2. Your Right to an Abortion in Prison ................................................................................................................................................................................... 47

a. Fourteenth Amendment Claims ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 48

b. Eighth Amendment Claims ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 48

2. Discrimination Towards Women in Prison ....................................................................................................................................................................... 49

3. Observations and Searches by Male Guards ................................................................................................................................................................... 49

I.

Issues of Importance to LGBTQ+ People and People Living with HIV/AIDS ............................................ 50

1. Your Right to Be Protected from Discrimination ............................................................................................................................................................ 51

a. Discrimination Generally ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 51

b. Job/Program Discrimination ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 53

c. Marriage and Visitation for LGBTQ+ People in Prison ........................................................................................................................................................................................................ 53

2. Your Right to be Free from Sexual and Physical Violence ............................................................................................................................................ 54

a. Abuse by Prison Officials ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 54

b. Abuse from Other Incarcerated People .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 54

b. Sexual Harassment and Verbal Abuse ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 55

c. Access to Protective Custody .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 56

d. Cross-Gender Strip Searches ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 56

e. Shower Privacy .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 57

3. Your Right to Facility Placements ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 57

a. Placement in male or female facilities ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 57

b. Placement in involuntary segregation ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 58

c. HIV/AIDS Segregation ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 59

4. Your Right to Health Care .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 60

a. Your Right to Mental and Medical Health Care Generally .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 60

5. Your Right to Gender-Affirming Medical Care and Free Gender Expression .......................................................................................................... 60

a. Challenging Gender Dysphoria Treatment Denials Generally ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 60

b. Gaining Access to Hormone Therapy ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 62

c. Clothing, Grooming, and Social Transition .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 62

d. Gaining Access to Gender-Confirmation Surgery ................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 63

e. Changing Your Name and Gender Marker ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 64

6. Your Other Rights in Custody .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 65

a. Your Right to Confidentiality ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 65

b. Access to LGBTQ+-Related Reading Material ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 66

J.

Issues of Importance to Pretrial Detainees ....................................................................................................... 66

K. Issues of Importance to Non-Citizens and Immigration Detainees ............................................................ 68

L. Protection of Prisoners Under International Law ............................................................................................ 70

1. Sources of International Legal Protection ........................................................................................................................................................................ 70

2. Filing a Complaint to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture ................................................................................................................ 71

3. Sending a Petition to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) ................................................................................................ 72

CHAPTER FOUR: Who to Sue and What to Ask for 73

A. What to Ask for in Your Lawsuit ......................................................................................................................... 73

B. Injunctions ................................................................................................................................................................. 73

1. Preliminary Injunctions and Permanent Injunctions ....................................................................................................................................................... 74

2. Exhaustion and Injunctions .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 75

3. Temporary Restraining Orders ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 75

C. Money Damages ...................................................................................................................................................... 75

1. The Three Types of Money Damages ................................................................................................................................................................................ 75

2. Damages Under the PLRA .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 76

3. Deciding How Much Money to Ask For ........................................................................................................................................................................... 77

D. Who You Can Sue ................................................................................................................................................... 77

1. Who to Sue for an Injunction .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 78

2. Who to Sue for Money Damages: The Problem of “Qualified Immunity” ............................................................................................................... 78

3. What Happens to Your Money Damages ......................................................................................................................................................................... 79

E. Settlements ............................................................................................................................................................... 80

F. Class Actions ............................................................................................................................................................. 80

CHAPTER FIVE: How to Start Your Lawsuit 82

A. When to File Your Lawsuit ................................................................................................................................... 82

1. Statute of Limitations ............................................................................................................................................................................................................ 82

2. Exhaustion of Administrative Remedies ........................................................................................................................................................................... 83

B. Where to File Your Lawsuit .................................................................................................................................. 84

C. How to Start Your Lawsuit ................................................................................................................................... 84

1. Summons and Complaint ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 85

2. In Forma Pauperis Papers ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... 90

3. Request for Appointment of Counsel ................................................................................................................................................................................ 93

D. How to Serve Your Legal Papers ........................................................................................................................ 95

E. Getting Immediate Help from the Court ............................................................................................................ 95

F. Signing Your Papers ................................................................................................................................................ 98

CHAPTER SIX: What Happens After You File Your Suit 99

A. Short Summary of a Lawsuit ................................................................................................................................. 99

B. Dismissal by the Court and Waiver of Reply ................................................................................................. 100

C. How to Respond to a Motion to Dismiss Your Complaint ......................................................................... 101

D. The Problem of Mootness ................................................................................................................................ 102

E. Discovery ................................................................................................................................................................ 103

1. Discovery Tools ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 103

2. What You Can See and Ask About ................................................................................................................................................................................... 106

3. Privilege .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 106

4. Some Basic Steps .................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 106

5. Some Practical Considerations .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 107

6. Procedure ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 107

7. Their Discovery of Your Information and Material ...................................................................................................................................................... 108

F. Summary Judgment .............................................................................................................................................. 108

1. The Legal Standard ............................................................................................................................................................................................................... 109

2. Summary Judgment Procedure ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 110

3. Summary Judgment in Your Favor ................................................................................................................................................................................... 110

G. What to Do If Your Complaint Is Dismissed or the Court Grants

Defendants Summary Judgment ........................................................................................................................... 111

1. Motion to Alter or Amend the Judgment ....................................................................................................................................................................... 111

2. How to Appeal the Decision of the District Court ....................................................................................................................................................... 111

CHAPTER SEVEN: The Legal System and Legal Research 112

A. The Importance of Precedent ........................................................................................................................... 112

1. The Federal Court System .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 112

2. How Judges Interpret Laws on the Basis of Precedent .............................................................................................................................................. 112

3. Statutes ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 114

4. Other Grounds for Court Decisions ................................................................................................................................................................................. 114

B. Legal Citations – How to Find Court Decisions and Other Legal Material ............................................ 114

1. Court Decisions ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 114

2. Legislation and Court Rules ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 117

3. Books and Articles ................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 117

4. Research Aids ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 117

C.

Legal Writing

...........................................................................................................................................................

118

APPENDICES 120

A. Glossary of Terms ................................................................................................................................................ 120

B. Sample Complaint ................................................................................................................................................ 125

C. FTCA Form ............................................................................................................................................................. 128

D. Other Legal Forms ............................................................................................................................................... 130

E. (State Supplement Appendix) State Grievanc Procedures, PREA Rules, & LGBTQ+ Policies

Applicable in Certain States ................................................................................................................................... 133

F. Excerpts from the PLRA ...................................................................................................................................... 147

G. Model Questionnaire for United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture ............................................ 150

H. Universal Declaraton of Human Rights .......................................................................................................... 151

I. Sources of Legal Support ..................................................................................................................................... 154

J. Sources of Publicity .............................................................................................................................................. 156

K. Prisoners' Rights Books and Newsletters ...................................................................................................... 157

L. Free Book Programs ............................................................................................................................................. 158

M. District Court Addresses ................................................................................................................................... 159

N. Constitutional Amendments (First through Fifteenth) ............................................................................... 175

A

1 | CHAPTER 1 – HOW TO USE THE JLH

CHAPTER ONE:

How to Use the JLH

A.

What Is This Handbook?

This Handbook explains how a person in prison or

detention can start a lawsuit in federal court to fight

against mistreatment and bad conditions. As a result of the

fact that most prisoners are in state prisons, we focus on

those. However, people in federal prisons and city or

county jails will be able to use the Handbook too.

We, the authors of the Handbook, do not assume that a

lawsuit is the only way to challenge abuse in prison or that

it is always the best way. We believe that a lawsuit can

sometimes be one useful weapon in the struggle to change

prisons and the society that makes prisons the way they

are.

The Handbook discusses only some of the legal problems

which prisoners face—conditions inside prison and the way

you are treated by prison staff. The Handbook does not

deal with how you got to prison or how you can get out of

prison. It does not explain how to conduct a legal defense

against criminal charges or a defense against disciplinary

measures for something you supposedly did in prison.

Chapter One: Table of Contents

Section A ....................................... What Is This Handbook?

Section B ................................. How to Use This Handbook

Section C ............................. Who Can Use This Handbook

Section D ............................. Why to Try and Get a Lawyer

Section E ............................. Short History of Section 1983

and the Struggle for Prisoner’s Rights

Section F .................. The Uses and Limits of Legal Action

The Importance of “Section 1983”

A prisoner can file several different kinds of cases about

conditions and treatment in prison. This Handbook is

mostly about only one kind of legal action: a lawsuit in

federal court based on federal law. For prisoners in state

prison, this type of lawsuit is known as a “Section 1983”

suit. It takes its name from Section 1983 of Title 42 of the

United States Code. The U.S. Congress passed Section 1983

to allow people to sue in federal court when a state or

local official violates their federal rights. If you are in state

prison, you can bring a Section 1983 suit to challenge

certain types of poor treatment. Chapter Three of this

Handbook explains in detail which kinds of problems you

can sue for using Section 1983.

B.

How to Use This Handbook

The Handbook is organized into six chapters and several

appendices:

> This is Chapter One, which gives you an introduction to

the Handbook. Sections C through E of this chapter

indicate the limits of this Handbook and explain how to

try to get a lawyer. Sections F and G give a short history

of Section 1983 and discuss its use and limits in political

struggles in and outside prison.

> Chapter Two discusses the different types of lawsuits

available to prisoners and summarizes an important

federal law that limits prisoners’ access to the courts,

called the Prison Litigation Reform Act.

> Chapter Three summarizes many of your constitutional

rights in prison.

> Chapter Four explains how to structure your lawsuit,

including what kind of relief you can sue for, and who to

sue.

> Chapter Five gives the basic instructions for starting a

federal lawsuit and seeking immediate help from the

court—what legal papers to file, when, where, and how.

It also provides templates and examples of important

legal documents.

> Chapter Six discusses the first things that will happen

after you start your suit. It helps you respond to a

“motion to dismiss” your suit or a “motion for summary

judgment” against you. It also tells you what to do if

prison officials win these motions. It explains how to use

“pretrial discovery” to get information and materials

from prison officials.

> Chapter Seven gives some basic information about the

U.S. legal system. It also explains how to find laws and

court decisions in a law library and how to refer to them

in legal papers.

2 | CHAPTER 1 – HOW TO USE THE JLH

> The Appendices are additional parts of the Handbook

that provide extra information. The appendices to the

Handbook provide materials for you to use when you

prepare your suit and after you file it. Appendix A

contains a glossary of legal terms. Appendix B is a

sample complaint in a prison case. Appendices C and D

contain forms for basic legal papers. You will also find

helpful forms and sample papers within Chapters Four

and Five. Appendix E contains information about

administrative grievance procedures, PREA Rules, and

LGBTQ+ policies applicable in certain states. Appendix

F has a few of the important sections of the Prison

Litigation Reform Act, and Appendix G includes the

Model Questionnaire for United Nations Special

Rapporteur on Torture, and Appendix H contains the

Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Appendix I lists

possible sources of further legal support. Appendix J

contains some tips from working journalists on how to

approach media outlets if you want to publicize your

case or your story. Appendix K lists other legal

materials you can read to keep up to date and learn

details which are not included in this manual. Appendix

L lists free book programs for prisoners, and Appendix

M includes a list of addresses of federal district courts

for your reference. Appendix N gives the text of the

first fifteen amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

We strongly recommend that you read the whole

handbook before you start trying to file your case.

C.

Who Can Use This Handbook

Most of the prisoners in the country are in state prison, but

prisoners in other sorts of prisons or detention centers can

use this book too.

1. Prisoners in Every State Can Use This

Handbook

Section 1983 provides a way for state prisoners to assert

their rights under the United States Constitution. Every

state prisoner in the country, no matter what state or

territory they are in, has the same rights. However,

different courts interpret these rights differently. For

example, a federal court in New York may come to one

conclusion about an issue, while a federal court in

Tennessee may reach a totally different conclusion about

the same issue.

First Steps:

1. Know Your Rights! Ask yourself: have my federal

rights been violated? If you have experienced one of

the following, the answer may be yes:

> Guard or prisoner brutality or harassment

> Unsafe cell or prison conditions

> Censorship, or extremely limited mail, phone, or

visitation privileges

> Inadequate medical care

> Interference with practicing your religion

> Inadequate food

> Racial, sexual, or ethnic discrimination

> Placement in isolation without a hearing

2. Exhaust the Prison Grievance System! Use all the

steps in the prison complaint or grievance system and

write up your concerns in detail. Appeal it all the way

and save your paperwork. You MUST do this before

filing a suit.

3. Try to Get Help! Consider trying to hire a lawyer or

talking to a jailhouse lawyer and be sure to request a

pro se Section 1983 packet from your prison law library

or the district court.

States also have their own laws, and their own

constitutions. State courts, rather than federal courts, have

the last word on what the state constitution means. This

means that in some cases, you might have more success in

state court than in federal court. You can read more about

this possibility in the next chapter.

Unfortunately, we don’t have the time or the space to tell

you about the differences in the law from state to state.

So, while using this Handbook, you should also try to check

state law using the resources listed in Appendix K. You can

also check the books available in your prison and contact

the National Lawyers Guild or any other lawyers, law

students or political groups you know of that support

prisoners’ struggles.

2. Prisoners in Federal Prison Can Use This

Handbook

If you are in federal prison, this Handbook will also be

helpful. Federal prisoners have basically the same federal

rights as state prisoners. Where things are different for

people in federal prison, we have tried to make a note of it

for you.

The major difference is that federal prisoners cannot use

Section 1983 to sue about bad conditions and

mistreatment in federal prison. Instead, you have a couple

of options. For some violations of your constitutional

rights, you can use a case called Bivens v. Six Unknown

3 | CHAPTER 1 – HOW TO USE THE JLH

Named Agents of Federal Bureau of Narcotics, 403 U.S. 388

(1971). The Bivens case allows people in prison to sue over

some Eighth Amendment violations and maybe other

constitutional violations as well. When you bring a lawsuit

using Bivens, it is called a “Bivens action.”

Federal prisoners can also use a federal law called the

Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA) to sue the United States

directly for your mistreatment. Both Bivens and FTCA suits

are explained in more detail in Chapter Two. The bottom

line is that federal and state prisoners have mostly the

same rights, but they will need to use slightly different

procedures when filing a case.

3. Prisoners in City or County Jails Can Use

This Handbook

People serving sentences in jail have the same rights under

Section 1983 and the U.S. Constitution as people in prison.

Usually these are city jails, but they can be run by any kind

of municipality. A “municipality” is a city, town, county, or

other kind of local government.

People in jail waiting for trial are called “pretrial detainees,”

and sometimes have more protection under the

Constitution than convicted prisoners. Chapter Three,

Section J discusses some of the ways in which pretrial

detainees are treated differently than convicted prisoners.

However, you can still use most of the cases and

procedures in this Handbook to bring your Section 1983

claim. Where things are different for people in jails, we

have tried to make note of it for you.

4. Prisoners in Private Prisons Can Use This

Handbook

As you know, most prisons are run by the state or the

federal government, which means that the guards who

work there are state or federal employees. A private

prison, on the other hand, is operated by a for-profit

corporation, which employs private individuals as guards.

If you are one of the hundreds of thousands of prisoners

currently incarcerated in a private prison, most of the

information in this Handbook also applies to you. The

ability of state prisoners in private prisons to sue under

Section 1983 is discussed in Chapter Two, Section A. In

some cases it is actually easier to sue private prison guards

because they cannot claim “qualified immunity.” You will

learn about “qualified immunity” in Chapter 4, Section D.

How Do I Use This Handbook?

This is the Jailhouse Lawyers Handbook. Sometimes it

will be referred to as the “JLH” or the “Handbook.” It is

divided into seven chapters, which are also divided into

different sections. Each section has a letter, like “A” or

“B.” Some sections are divided into parts, which each

have a number, like “1” or “2.”

Sometimes we will tell you to look at a chapter and a

section to find more information. This might sound

confusing at first but when you are looking for specific

things, it will make using this Handbook much easier.

We have tried to make this Handbook as easy to read

as possible. But there may be words that you find

confusing. At the end of the Handbook, in Appendix A,

we have listed many of these words and their meanings

in the Glossary. If you are having trouble understanding

any parts of this Handbook, you may want to seek out

the Jailhouse Lawyers in your prison. Jailhouse Lawyers

are prisoners who have educated themselves on the

legal system, and one of them may be able to help you

with your suit.

In many places in this Handbook, we refer to a past

legal suit to prove a specific point. It will appear in

italics, and with numbers after it, like this:

Smith v. City of New York, 311 U.S. 288 (1994)

This is called a “citation.” It means that a court decided

the case of Smith v. City of New York in a way that is

helpful or relevant to a point we are trying to make.

Look at the places where we use citations as examples

to help with your own legal research and writing.

Chapter Seven explains how to find and use cases and

the meaning of citations.

D.

Why to Try and Get a Lawyer

Unfortunately, not that many lawyers represent prisoners,

so you may have trouble finding one. You have a right to

sue without a lawyer. This is called suing “pro se,” which

means “in one’s own behalf.” Filing a lawsuit pro se is very

difficult. Thousands of lawsuits are filed by prisoners every

year, and most of these suits are lost before they even go

to trial. We do not want to discourage you from turning to

the court system, but encourage you to do everything you

can to try to get a lawyer to help you, before you decide to

file pro se.

4 | CHAPTER 1 – HOW TO USE THE JLH

Why So Much Latin?

"Pro Se" is one of several Latin phrases you will see in

this Handbook. The use of Latin in the law is

unfortunate, because it makes it hard for people who

aren't trained as lawyers to understand a lot of

important legal procedures. We have avoided Latin

phrases whenever possible. When we have included

them, it is because you will see these phrases in the

papers filed by lawyers for the other side, and you may

want to use them yourself. Whenever we use Latin

phrases, we have put them in italics, like pro se. Check

the glossary at Appendix A for any words, Latin or

otherwise, that you don't understand.

A lawyer is also very helpful after your suit has been filed.

They can interview witnesses and discuss the case with

the judge in court while you are confined in prison. A

lawyer also has access to a better library and more

familiarity with legal forms and procedures. And despite all

the legal research and time you spend on your case, many

judges are more likely to take a lawyer seriously than

someone filing pro se.

If you feel, after reading Chapter Three, that you have a

basis for a lawsuit, try to find a good lawyer to represent

you. You can look in the phone book to find a lawyer or to

get the address for the “bar association” in your state. A

bar association is a group that many lawyers belong to.

You can ask the bar association to give you the names of

some lawyers who take prison cases. Some prisoners’

rights organizations can sometimes help you find a lawyer.

You probably will not be able to pay the several thousand

dollars or more which you would need to hire a lawyer. But

there are other ways you might be able to get a lawyer to

take your case.

> If you have a good chance of winning a substantial

amount of money (explained in Chapter Four, Section C), a

lawyer might take your case on a “contingency fee” basis.

This means you agree to pay the lawyer a portion of your

money damages if you win (usually between 30-40%), but

the lawyer gets nothing if you lose. This kind of

arrangement is used in many suits involving car accidents

and other personal injury cases outside of prison. In prison,

it may be appropriate if you have been severely injured by

guard brutality or due to unsafe prison conditions.

> If you don’t expect to win money from your suit, a

lawyer who represents you in some types of cases can get

paid by the government if you win your case. These fees

are authorized by the United States Code, Title 42, Section

1988. However, the Prison Litigation Reform Act of 1996

(called the “PLRA” and discussed in Chapter Two, Section

E) added new rules that restrict the court’s ability to award

fees to your lawyer. These new provisions may make it

harder to find a lawyer who is willing to represent you.

> If you can’t find a lawyer to represent you from the start,

you can file the suit yourself and ask the court to “appoint”

a lawyer for you. This means the court will recruit a lawyer

to take your case. Unlike in a criminal case, you have no

absolute right to a free attorney in a civil case about prison

abuse. This means that a judge is not required by law to

make a lawyer take your Section 1983 case, but they can

do so if they choose to and are able to find a willing

lawyer. You will learn how to ask the judge to get you a

lawyer in Chapter Five, Section C, Part 3 of this Handbook.

> A judge can appoint a lawyer as soon as you file your

suit. But it is much more likely that they will only appoint a

lawyer for you if you successfully get your case moving

forward and convince the judge that you have a chance of

winning. This means that the judge may wait until after

they rule on the prison officials’ motions to dismiss your

complaint or motion for summary judgment. Chapters Five

and Six of this Handbook will help you prepare your basic

legal papers and respond to a motion to dismiss or a

motion for summary judgment.

Even if you have a lawyer from the start, this Handbook is

still useful to help you understand what they are doing.

Be sure your lawyer explains the choices you have at each

stage of the case. Remember that they are working for

you. This means that they should answer your letters and

return your phone calls within a reasonable amount of

time. Don’t be afraid to ask your lawyer questions. If you

don’t understand what is happening in your case, ask your

lawyer to explain it to you. Don’t ever let your lawyer force

decisions on you or do things you don’t want.

E.

A Short History of Section 1983

and the Struggle for Prisoners’

Rights

As you read in Sections A and C, most prisoners who

decide to challenge abuse or mistreatment in prison will do

so through a federal law, 42 U.S.C. § 1983, usually just

known as “Section 1983.” Section 1983 is a way for any

individual (not just a prisoner) to challenge something done

by a state employee or local government employee. The

part of the law you need to understand reads as follows:

Every person who, under color of any statute,

ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any

State or Territory or the District of Columbia,

subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen

of the United States or other person within the

jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any

rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the

Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the

party injured in an action at law, suit in equity,

or other proper proceeding for redress …

5 | CHAPTER 1 – HOW TO USE THE JLH

Section A of Chapter Two will explain what this means in

detail, but we will give you some background information

here. Section 1983 was passed by the United States

Congress over 150 years ago. Section 1983 was originally

known as Section 1 of the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871.

Section 1983 does not mention race, and it can be used by

people of any color, but it was originally passed specifically

to help Black people enforce the new constitutional rights

they won after the Civil War—specifically, the 13th, 14th

and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. Those

amendments made slavery illegal, established the right to

“due process of law” and equal protection of the laws, and

guaranteed every male citizen the right to vote. Although

these amendments became law, white racist judges in the

state courts refused to enforce these laws, especially when

Black people had their rights violated by other state or

local government officials. The U.S. Congress passed

Section 1983 to allow people to sue in federal court when

a state or local official violated their federal rights.

Soon after Section 1983 became law, however, Northern

big businessmen joined forces with Southern plantation

owners to take back the limited freedom that Black people

had won. Federal judges found excuses to undermine

Section 1983 along with most of the other civil rights bills

passed by Congress. Although the purpose of Section

1983 was to bypass the racist state courts, federal judges

ruled that most lawsuits had to go back to those same

state courts. Their rulings remained law until Black people

began to regain their political strength through the civil

rights movement of the 1960s.

In the 1960s, a series of very good Supreme Court cases

reversed this trend and transformed Section 1983 into an

extremely valuable tool for state prisoners. People in

prison soon began to file more and more federal suits

challenging prison abuses. A few favorable decisions were

won, dealing mainly with freedom of religion, guard

brutality, and a prisoner’s right to take legal action without

interference from prison staff. But many judges still

continued to believe that the courts should let prison

officials make the rules, no matter what those officials did.

This way of thinking is called the “hands-off doctrine,”

because judges keep their “hands off” prison administration.

The next big breakthrough for prisoners did not come until

the early 1970s. Black people only began to win legal

rights when they organized together politically, and labor

unions only achieved legal recognition after they won

important strikes. In the same way, prisoners did not begin

to win many important court decisions until the prison

movement grew strong.

Powerful, racially united strikes and rebellions shook

Folsom Prison, San Quentin, Attica, and other prisons

throughout the country during the early 1970s. These

rebellions brought the terrible conditions of prisons into

the public eye and had some positive effects on the way

federal courts dealt with prisoners. Prisoners won

important federal court rulings on living conditions, access

to the media, and procedures and methods of discipline.

Unfortunately, the federal courts did not stay receptive to

prisoners’ struggles for long. In 1996, Congress passed and

President Clinton signed into law the Prison Litigation

Reform Act (PLRA). The PLRA is very anti-prisoner and

works to limit prisoners’ access to the federal courts. Why

would Congress pass such a bad law? Many people say

Congress believed a story that was told to them by states

tired of spending money to defend themselves against

prisoner lawsuits. In this story, prisoners file mountains of

unimportant lawsuits because they have time on their

hands and enjoy harassing the government. The obvious

truth—that prisoners file a lot of lawsuits because they are

subjected to a lot of unjust treatment—was ignored.

The PLRA makes filing a complaint much more costly,

time-consuming, and risky to prisoners. Many prisoners’

rights organizations have tried to get parts of the PLRA

struck down as unconstitutional, but so far this effort has

been unsuccessful. You will find specific information about

the individual parts of the PLRA in later chapters of this

Handbook. Some of the most important sections of the

PLRA are included in Appendix F at the end of this book.

History has taught us that convincing the courts to issue

new rulings to improve day-to-day life in prisons and

change oppressive laws like the PLRA requires not only

litigation, but also the creation and maintenance of a

prisoners' rights movement both inside and outside of the

prison walls.

F.

The Uses and Limits of Legal

Action

Only a strong prison movement can win and enforce

significant legal victories. But the prison movement can

also use court action to help build its political strength. A

well-publicized lawsuit can educate people outside about

the conditions in prison. The struggle to enforce a court

order can play an important part in political organizing

inside and outside prison. Good court rulings backed up by

a strong movement can convince prison staff to hold back

so that conditions inside are a little less brutal, and

prisoners have a little more freedom to read, write, and

talk.

Still, the value of any lawsuit is limited. It may take several

years from starting the suit to win a final decision that you

can enforce. There may be complex trial procedures,

appeals, and delays in complying with a court order. Prison

officials may be allowed to follow only the technical words

of a court decision while continuing their illegal behavior

another way. Judges may ignore law which obviously is in

your favor because they are afraid of appearing “soft on

criminals,” or because they think prisoners threaten their

own position in society. Even the most liberal, well-

meaning judges will only try to change the way prison

officials exercise their power. No judge will seriously

6 | CHAPTER 1 – HOW TO USE THE JLH

address the staff’s basic control over your life while in

prison.

To make fundamental changes in prison, you can’t rely

on lawsuits alone. It is important to connect your suit to

the larger struggle. Write press releases that explain your

suit and what it shows about prison and about the reality

of America. Send the releases to newspapers, radio and

TV stations, and legislators. Keep in touch throughout the

suit with outside groups that support prisoners’ struggles.

Look at Appendix J for tips we collected from journalists

on how to approach media and groups that may be able

to help you.

You may also want to discuss your suit with other

prisoners and involve them in it even if they can’t

participate officially. Remember that a lawsuit is

most valuable as one weapon in the ongoing struggle

to change prisons and the society which makes prisons

the way they are.

Of course, all this is easy for us to say, because we are not

inside. All too often, jailhouse lawyers and activists face

retaliation from guards due to their organizing and

lawsuits. Chapter Three, Section G, Part 4 explains some

legal options if you face retaliation. However, while the law

may be able to stop abuse from happening in the future,

and it can compensate you for your injuries, the law cannot

guarantee that you will not be harmed. Only you know the

risks that you are willing to take.

Finally, you should know that those of us who fight this

struggle from the outside are filled with awe and respect

at the courage of those of you who fight it, in so many

different ways, on the inside.

“Jailhouse lawyers aren’t

simply, or even mainly,

jailhouse lawyers. They are

sons, daughters, uncles,

nieces, parents, sometimes

teachers, grandparents, and

occasionally writers. In short, they are part of a

wider, broader, deeper social fabric.”

– Mumia Abu-Jamal

Award-winning journalist, author, and jailhouse lawyer,

from his 2009 book “Jailhouse Lawyers.”

7 | CHAPTER 2 – OVERVIEW OF THE TYPES OF LAWSUITS AND THE PRISON LITIGATION REFORM ACT

CHAPTER TWO:

Overview of Types of Lawsuits and the Prison Litigation Reform Act

This chapter describes the different types of lawsuits you

can bring to challenge conditions or treatment in prison or

detention, including Section 1983 actions, state law

actions, the Federal Tort Claims Act and Bivens actions. We

also discuss international law and explain the impact of the

Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA).

Chapter Two: Table of Contents

Section A .......................................... Section 1983 Lawsuits

Section B ................................................... State Court Cases

Section C ......................................... Federal Tort Claims Act

Section D .......................................................... Bivens Actions

Section E ............................................. Brief Summary of the

Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA)

A.

Section 1983 Lawsuits

Section 1983 lawsuits provide a way for people in state

prisons or local jails to get relief from unconstitutional

treatment or conditions. The main way to understand what

kind of lawsuit you can bring under Section 1983 is to look

at the words of that law:

“Every person who, under color of any statute,

ordinance, regulation, custom or usage, of any

State or Territory, or the District of Columbia,

subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen

of the United States or other person within the

jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any

rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the

Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the

party injured in an action at law, suit in equity,

or other proper proceeding for redress…”

Some of the words are perfectly clear. Others have

meanings that you might not expect, based on years of

interpretation by judges. In this section we will explore

what the words themselves and judges’ opinions from past

lawsuits tell us about what kind of suit is allowed under

Section 1983.

Although Section 1983 was designed especially to help

Black people, anyone can use it, regardless of race. The law

refers to “any citizen of the United States or any other

person within the jurisdiction thereof.” This means that

you can file a Section 1983 action even if you are not a

United States citizen. Martinez v. City of Los Angeles, 141

F.3d 1373 (9th Cir. 1998). All you need is to have been

“within the jurisdiction” when your rights were violated.

“Within the jurisdiction” just means you were physically

present in the United States.

Not every harm you suffer or every violation of your rights

is covered by Section 1983. There are two requirements.

First, Section 1983 applies to the “deprivation of any