Wayne State University Wayne State University

Wayne State University Theses

January 2022

The House Detroit Built: House Music In Techno City The House Detroit Built: House Music In Techno City

Keaton Jose Soto-Olson

Wayne State University

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_theses

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Soto-Olson, Keaton Jose, "The House Detroit Built: House Music In Techno City" (2022).

Wayne State

University Theses

. 875.

https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_theses/875

This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been

accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Theses by an authorized administrator of

DigitalCommons@WayneState.

THE HOUSE DETROIT BUILT: HOUSE MUSIC IN TECHNO CITY

by

KEATON SOTO-OLSON

THESIS

Submitted to the Graduate School

of Wayne State University,

Detroit, Michigan

in partial fulfillment of the requirements

for the Degree of

MASTER OF ARTS

MAJOR: MUSIC

ii

DEDICATION

This work is dedicated to the next generation of house heads, embrace the history of this music.

Dig deeper, listen with your heart, and move your body.

iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Experiencing house music in Detroit changed my life. Before I moved to Michigan and

began my graduate studies at Wayne State University, house music was largely unexplored

territory. I loved Daft Punk but hadn’t investigated the genre or its roots in any sort of depth, I

certainly would have never expected that it would become the topic of my thesis. Early on in my

time in Detroit I had a few transformative evenings on dancefloors around the city that lifted me

up high enough to see what I had been missing, and I had been missing a lot. There is an undeniable

spirit to this music, requiring only that we open ourselves up to it and that it’s played on a speaker

system capable of delivering the message. House music allows me and so many others the

opportunity to “Heal Yourself and Move.”

1

My experiences moving and healing on the dance floor

gave me the animus to pursue this research. I am forever indebted to the Detroit DJs, producers,

labels, record stores, magazines, promoters, clubbers, and clubs that created and cultivated this

music scene that I have come to love. Special thanks to Stacey “Hotwaxx” Hale for granting me

an interview and being so generous with her time and insights.

I owe a great debt of gratitude to the Wayne State Department of Music. This work would

not be possible without the support and opportunities provided by the department. Special thanks

are due to my program advisor Dr. Joshua S. Duchan for his guidance and encouragement through

my thesis project and graduate career. I’d also like to acknowledge the funding from the Music

Department, the Graduate Professional Scholarship, and the Lisa McKinney Endowed scholarship,

without the help I received this work would not have been possible.

1

This is one of my favorite tracks by Theo Parrish, a great example of hypnotic deep house.

iv

I would also like to thank my partner Kristen for introducing me to the Detroit electronic

music scene, for her continued love and support at home, and for her exemplary record digging!

To my family, parents Jose and Peggy, and brother Cooper, I am forever thankful and grateful for

you. A few sentences won’t encapsulate the depths of your contributions to my life and how much

your continued love and support sustains me. I hope to pay forward the encouragement, grace, and

love that I have received from you all to others.

With Love,

Keaton

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Dedication ....................................................................................................................................... ii

Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ iii

List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. vi

List of Figures ............................................................................................................................... vii

Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1

Literature Review...................................................................................................................... 3

Methodology ........................................................................................................................... 10

Chapter 2: Floor Plan .................................................................................................................... 13

“On And On” .......................................................................................................................... 19

Chapter 3: Foundation................................................................................................................... 23

Theoretical Notes .................................................................................................................... 23

Ken Collier: The Godfather .................................................................................................... 24

Stacey Hale: The Godmother .................................................................................................. 36

Analysis: Hale’s Beatport Performance .................................................................................. 44

Chapter 4: When Techno Was House ........................................................................................... 53

Analysis: Inner City’s “Do You Love What You Feel” ......................................................... 61

Chapter 5: Conclusion................................................................................................................... 66

Appendix: Stacey Hale Interview ................................................................................................. 70

Bibliography ............................................................................................................................... 110

Abstract ....................................................................................................................................... 113

Autobiographical Statement........................................................................................................ 114

vii

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 2.1 Outside view of The Warehouse, 206 S Jefferson St, Chicago, IL ..............................16

Figure 2.2. Club-goers reveling inside The Warehouse ................................................................18

Figure 2.3. Basic 2 house drum pattern, expressed in MIDI notation by author ...........................19

Figure 2.4. Author’s MIDI transcription of the eight-bar bass loop from “On and On.” ..............21

Figure 3.1. Dancer, “Skyscraper” in “The Circle,” at Club Heaven, 1991 ....................................31

Figure 3.2. Collier and Hale, photograph from personal collection of Stacey Hale ......................39

Figure 3.3. DRMC awards list, year unknown ..............................................................................43

Figure 3.4. Screen capture from Hale’s Beatport performance available on YouTube .................45

Figure 3.5. Basic layout for a 2-channel mixer ..............................................................................47

Figure 3.6. Pioneer CDJ-3000 .......................................................................................................48

Figure 4.1. Album cover for Techno! The New Dance Sound of Detroit ......................................54

Figure 4.2. Album artwork for The House Sound of Chicago .......................................................55

Figure 4.3. Liner notes on the label of “Happy Vocals” ................................................................58

Figure 4.4. Basic Techno style drum pattern in MIDI, by the author ............................................60

Figure 4.5. Deep house drum pattern .............................................................................................60

Figure 4.6. Label for Inner City’s “Do You Love What You Feel” ..............................................63

1

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

Detroit is Techno City. Birthed by the Detroit Four (Juan Atkins, Kevin Saunderson, Eddie

Fowlkes, and Derrick May) and carried on by subsequent waves of Detroit DJs, producers, and

labels, the techno sound has become a pillar of the city’s musical legacy.

1

Although this is certainly

warranted, it seems that techno’s shadow has slightly obscured the contributions of Detroit’s house

music scene. Certainly the electronic music associated with Detroit, for most, is Techno. But, as

soon as the first house tracks from Chicago made it to Detroit in the early 1980s, a foundation

developed. Detroit producers were making their own house records, Detroit DJs were playing

house music on the radio and in clubs, and a scene was developing.

Fast forward to 2021 and the house scene in Detroit has persisted. New venues like the

Spotlite, opened in 2019, cater specifically to house heads with a weekly party called “A Spotlite

on House” and bookings featuring older DJs like Hotwaxx Hale and John “Jammin” Collins,

alongside younger DJs in the city like DJ Holographic. Taking a cursory scan of the bookings for

local clubs for any given weekend reveals that although Detroit is “Techno City,” house music is

well represented. A night out in Detroit could start with house music and chardonnay at Motor

City Wine, and end with minimal techno and bottled water in an abandoned warehouse. Although

house and techno are identifiably different both sonically and aesthetically, they have coexisted

since their inception, and both remain integral to the clubbing ecosystem in the city. Certainly

some fans, DJs, and producers have their preferences, but the two styles are not, by any means,

mutually exclusive.

1

I have opted to use “The Detroit Four” as opposed to the more common “The Belleville Three”

to include Eddie Fowlkes as an integral part of the origin of techno.

2

The Movement Festival in 2020 was a great example of the strength of Detroit’s house and

techno scenes. Due to Covid-19, the festival was scaled down significantly. Instead of the Mega-

festival in Hart Plaza, seeing visitors from all over the world, Movement returned to its roots of

the original Detroit Electronic Music Festival (DEMF): it was free, all local, and glorious.

Re-named “Micro Movement” the festival featured only Detroit talent and took place at

several local clubs. It was incredible to bear witness to Detroit’s grit, revelry, and musical prowess

on display that weekend. Without the huge stage productions, international DJs, and travelling

crowds that typify the Movement weekend, all that was left was the city and its music, and that

was more than enough. For a city of its size, Detroit has continually produced an outsized amount

of stellar music in a variety of genres. Whether it’s punk, hip-hop, jazz, new wave, rock, Motown,

or house and techno, one can find a wealth of music of high caliber created in Detroit.

It is my hope that this work will shine a light onto important figures in Detroit house music

history, while also examining the overlap between house and techno production in Detroit, and

provide a baseline understanding of house music’s genesis in Chicago. Although this thesis is not

a definitive history of the genre in Detroit, it will serve as a useful starting point for those

unfamiliar with the Detroit house music, highlighting people and places that may be unknown to

many. Detroit house music has received recent recognition in larger publications like the New York

Times, Red Bull Music Academy, and Pitchfork, but these features are not a substitute for scholarly

3

research.

2

While Detroit techno has its seminal historical account in Dan Sicko’s Techno Rebels,

Detroit House lays in wait for recognition on that scale.

3

Literature Review

Detroit house music may not have a definitive historical text at this moment, and Detroit

techno and Chicago house have been far more well-trodden by journalists and historians alike. As

mentioned above, Dan Sicko’s Techno Rebels still stands as the preeminent account of the creation

of techno in Detroit. Sicko’s access to the progenitors of the genre, and analysis of the ways that

techno was exported and marketed across the United States and Europe, are real strengths of the

text. Sicko’s analysis of the impact of techno on the rave scene in England from 1989-1991 is

especially compelling. During this time frame, techno was very much an obscure, niche genre

without much media coverage or major label interest, but both acid house and techno gained

footing all around England and eventually other countries in Europe. London may be the major

metropolis in England, but Sicko finds that the more important connection point for Detroit artists

was really Sheffield. He writes: “The parrallels between Detroit and Sheffield are numerous: The

struggles with an industrial base and near-fatal dependency on it, great musical traditions (Detroit’s

Motown and Sheffield’s synth-pop), limited options for youth, and so on.”

4

Sicko displays an

ability throughout Techno Rebels to acknowledge the major touchstones (Belleville Three, Virgin

2

See Rubin “Detroit House Music Takes a Swaggering Step out of the Darkness,”

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/21/arts/music/detroit-house-panorama-festival-theo-

parrish.html; Hoffman “From the Autobahn to I-94: The origins of Detroit Techno and Chicago

House,” https://pitchfork.com/features/article/6204-from-the-autobahn-to-i-94/; and Arnold

“When Techno Was House,” https://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2017/08/chicago-house-

detroit-techno-feature

3

Dan Sicko, Techno Rebels: Renegades of Electronic Funk, (Detroit: Wayne State University

Press, 2010).

4

Sicko, Techno Rebels, 76.

4

UK’s Techno compilation), while being highly attuned to the nuances and deeper history of the

genre.

In Bill Brewster and Frank Broughton’s Last Night a DJ Saved My Life, a broad scope is

taken in charting the history of the DJ and the cultural impact of DJing and club culture.

5

Not

limited to electronic music, the authors start from the beginnings of the radio disc jockey with the

first radio broadcast in 1906 ,when Reginald Fessenden transmitted music and speech from Boston

to United Fruit Company ships in the Atlantic. From there, Brewster and Broughton provide a

history of the club, with a similar broad historical perspective. The rest of the book takes a genre-

specific approach, tackling Northern Soul, Reggae, and Disco before continuing through the

various electronic music styles of the ‘80s, and ‘90s. The genre-centered approach to the history

of DJ music and culture means that there isn’t a focus on any specific region, although there is

attention to the locales in which each genre was invented and flourished.

House and techno both have their respective chapters that distill down the major historical

landmarks in each genre’s development. One comes away from Brewster and Broughton’s work

with knowledge of the major clubs, tracks, and DJs in Chicago and Detroit. Special attention is

paid to Acid House, the subgenre that fueled the raves during the “Second Summer of Love” in

England during the summer of 1988. As for techno, Brewster and Broughton start from the musical

impetuses of radio DJ The Electrifying Mojo, Cybotron, and Kraftwerk before charting techno’s

rise from high school parties to its exportation and explosion in Germany. The breadth of the work

is impressive, but the flipside to such a broad scope is that the text does not go in-depth on any one

city or scene and does not acknowledge Detroit’s contribution to house music, instead focusing on

5

Bill Brewster and Frank Broughton, Last Night a DJ Saved My Life: The History of the Disc

Jockey (New York: Grove Press, 1999).

5

Chicago’s and New York’s contributions to the genre. Additionally, the benefit of a region or city-

specific approach allows for a more comprehensive history of the genre to be told, a la Sicko’s

Techno Rebels.

In contrast, Simon Reynold’s Energy Flash takes a narrower focus in terms of historical

time-period and genre.

6

Energy Flash is expressly concerned with the development of electronic

dance music and rave culture from the mid-‘80s onward. The book’s name comes from a classic

Joey Beltram track, “Energy Flash,” which makes unveiled references to MDMA throughout. For

example, the only lyrics in the song are a low pitched voice repeating the word “ecstasy.”

Certainly, ecstasy was a revelation for many clubbers, but for many of the creators of Detroit

techno specifically, drugs and alcohol were not a part of the scene. Seminal Detroit club The Music

Institute was alcohol free, and from the accounts of Jeff Mills, Detroit was not a particularly druggy

scene to begin with.

7

Sicko affirms that many in Detroit felt that their music had been co-opted by

druggier scenes abroad: “Drugs were almost completely absent in Detroit’s techno scene, small as

it was, and the artists were undoubtedly a bit shocked to find their music fused with any kind of

drug-related experience.”

8

There is no doubt that drugs like ecstasy, LSD, and cocaine played a

role in the development of the party/club scene surrounding house and techno, but it is equally

important to remember that they played a less prominent role in the creation of the music in Detroit.

Despite the druggy overtones, Reynolds gives Detroit its due in terms of musical impact,

at least as far as techno is concerned. The book starts with the development of Detroit techno and

6

Simon Reynolds, Energy Flash: A Journey Through Rave Music and Dance Culture (Berkley:

Soft Skull Press, 2012).

7

See the Red Bull Music Academy interview with Jeff Mills:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-K0tVVnXfn4

8

Sicko, 79.

6

has another chapter, entitled “The Future Sound of Detroit,” dedicated to some of the second wave

of Detroit techno producers and labels in the early ‘90s. Reynolds is also able to provide analysis

of the aesthetic differences between sub-genres, acknowledging their distinct sounds while giving

a historical sense of the progression of genres from impetus to novel innovations. Additionally,

Reynolds acknowledges the connection between Detroit and Chicago early on in house music’s

development.

Another important strength of Reynolds’s work is noting the spiritual aspect of the rave

experience. However, I think Reynolds misses the importance of a broader point by analyzing the

“spiritual revolution” of the rave movement by placing so much emphasis on the drug Ecstasy,

rather than people’s ecstatic experiences through music, drug induced or otherwise. Indeed,

feelings of spiritual connection, love, and euphoria are effects of taking MDMA, effects that are

often heightened by the rave environment, but it is wholly possible to experience these feelings at

a rave or dance club without any chemical enhancement. The true beauty of the dance floor and

rave culture is the music and the connection it makes with people, these bonds far outlast the six

hours of an ecstasy high.

Do You Remember House?: Chicago’s Queer of Color Undergrounds, by Micah Salkind,

provides a wealth of information about the beginnings and early development of the house music

scene in Chicago.

9

Salkind’s approach is interdisciplinary, covering the DJs, radio stations and

producers that made the music, the dancers who filled the floors of clubs like the Warehouse, the

fashion trends that emerged, and the physical spaces (studios, juice bars, clubs, and record stores)

that sustained the scene. Relying primarily on oral history interviews, with plenty of basis in

9

Micah Salkind, Do You Remember House?: Chicago’s Queer of Color Undergrounds (New

York: Oxford University Press, 2019).

7

ethnomusicology and gender theory, Salkind constructs a historical account of house music in

Chicago that is cohesive and comprehensive without being fixated on the drug scenes. Salkind sets

the scene of the Disco Demolition at Comiskey Park in Chicago and the broader cultural narratives

of homophobia surrounding disco at the time. The two main clubs in Chicago house history, The

Warehouse and The Music Box, receive a thorough examination with thorough analysis of Frankie

Knuckles and Ron Hardy.

The second half of Salkind’s book deals with contemporary issues related to Chicago house

music and queer spaces. Of particular highlight is the final chapter, “Dancing in Brave Spaces.”

Salkind constructs an autoethnographic account of learning to dance in the Chicago house styles,

balanced with oral histories of social dancers in Chicago’s queer of color undergrounds. Salkind’s

work is a worthy a template for how to write a multifaceted music history text that focuses on a

specific city, and Do You Remember House? is a worthy example for what a truly extensive history

of Detroit House music could look like.

Detroit electronic music has been represented in scholarly work as well. Carla Vecchiola

(University of Michigan-Dearborn) has contributed several pieces that stand out and were of great

help to my work. In her article, “Submerge in Detroit: Techno’s Creative Response to Urban

Crisis,” Vecchiola subverts the narrative of Detroit as “urban failure” by examining the success

and resilience of Submerge Records.

10

For Vecchiola, Submerge is an example of “grassroots

urban revitalization.” Grassroots is a key word here as much of the urban renewal endeavors in

many cities, Detroit included, have been spearheaded by outside interests, gentrifying areas and

reaping the spoils. Vecchiola finds that Submerge was a response to the difficulties that Mike

10

Carla Vecchiola, “Submerge in Detroit: Techno’s Creative Response to Urban Crisis,” Journal

of American Studies 45, no. 1 (2011): 95–111.

8

Banks and Jeff Mills faced in working with other record distribution and manufacturing

companies. Vecchiola also points out that Submerge helped many smaller labels in Detroit, some

of which were struggling with the business side of producing music. Submerge also served as a

template and inspiration for independent labels and distributors in Europe, Japan, and Australia.

Submerge is legendary in Detroit, after starting in a basement in 1992 the company has

become a staple of the electronic music community in Detroit. Today the company distributes

Detroit records domestically and internationally, operates a physical record store, and houses

Exhibit 3000, a historical exhibit dedicated to the city’s techno tradition. Although musical

analysis is not the focus of her work, Vecchiola points out some general musical differences

between house and techno, and that both genres are made in Detroit and Chicago. These two

revelations were key in the construction of my chapter, “When Techno was House.”

Perhaps the most central text that has influenced my analysis of electronic music

performances, Mark Butler’s Playing With Something That Runs focuses on DJ, laptop, and other

types of electronic music performance.

11

Butler takes an analytical and ethnographic approach,

using interviews with musicians and DJs as well as analysis of their techniques, aesthetics, and

performances. His work fights against the trope that DJs and laptop musicians are just “checking

their e-mails” on stage. Butler offers several useful concepts that inform my analysis of Stacey

Hale’s DJ performance.

Part of the problem with viewing electronic performances is that it is often unclear what

performers are doing. Audiences cannot see the laptop screens or MIDI controllers that are in use,

so it would not be clear that a DJ was improvising on the fly rather than executing a preplanned

11

Mark J. Butler, Playing With Something That Runs: Technology, Improvisation, and

Composition in DJ and Laptop Performance (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

9

playlist. Improvisation is a central interest of Butler’s; though most often associated with styles

like jazz, improvisation plays an important role in just about every style of electronic music. The

degree to which performances are improvised can vary depending on the context of the

performance and the gear being used, but most performances are some mixture between the two.

Butler’s work is important and valuable because it emphasizes the interaction between people and

technology, without giving primacy to either.

In Discographies: Dance, Music, Culture and the Politics of Sound, Jeremy Gilbert and

Ewan Pearson’s goal is to “respond, from the point of view of ‘cultural studies’ and ‘critical

theory,’ to some of the effects which dance culture has generated over the last twenty years” (for

reference this text was published in 1999 so the attendant time range would be 1979-1999).

12

Much

of the text has a philosophical bent, for example Plato, Barthes, Kant, and Derrida are all tied into

discussion about the metaphorical role of the voice in music. Techno and house get attention

directly in chapter three, “The Metaphysics of Music,” in which the authors describe how house,

techno, and selected sub-genres make unique aesthetic choices that upset the typical priorities of

music in the west. Additionally, Pearson and Gilbert muse on the different ways in which the

musics push the listener to “jouissance,” a term adopted from Roland Barthes’s meaning, more or

less, ecstacy. The musics may not all sound the same but they seem to share a common,

“metaphysical” destination.

12

Jeremy Gilbert Ewan Pearson, Discographies: Dance, Music, Culture and the Politics of

Sound (London: Taylor & Francis, 1999).

10

Methodology

In addition to the sources listed above, I have taken several different methodological

approaches in my work here. First, I had the honor of interviewing Stacey “Hotwaxx” Hale, who

was incredibly gracious with her knowledge and her time. Throughout my work, primary source

interviews play a large role, especially in the discussion of Hale and Ken Collier. My interview

style was informed by ethnographic interview methods and strategies outlined by Barbara Sherman

Heyl in the Handbook of Ethnography and Amanda Coffey in Doing Ethnography, both of which

were integral to the way I framed my questions and conducted the interview.

13

In addition, I

consulted print interviews from a variety of dance music and LGBTQ-centered publications, and

a panel discussion hosted by the Michigan Electronic Music Collective (MEMCO) at the

University of Michigan, which featured Ms. Hale. I also analyze a live performance of Hale’s

(available on YouTube) and have created a listening/watching guide for the performance.

For my research on Ken Collier, several sources proved useful. The archive of the Detroit

Sound Conservancy featured an interview and DJ set of Collier’s. I also used SoundCloud to find

a DJ set of Collier’s from the ‘90s and utilized the user comments to investigate how his work

continues to resonate. Although there is not an abundance of video from Club Heaven, there are a

few that I have referenced and cited that will help the reader develop a picture of what a night out

at Heaven might have been like.

13

Amanda Coffey, “In the field : Observation, conversation and documentation,” in Doing

Ethnography (London: Sage, 2020), 43–58; Barbara Sherman Heyl, “Ethnographic

Interviewing,” in Handbook of Ethnography (London: Sage, 2001), 369–83.

11

Another important part of this thesis is the analysis of house and techno records. I use

harmonic analysis and also examine the timbral choices the producers make (with synths, drum

sounds, etc.) in order to explore the ways in which house and techno from Detroit distinguish

themselves in practice. My analysis is supplemented by consulting Hale and interviews with Mike

“Mad Mike” Banks, where they offer their conceptions of what distinguishe techno and house, as

well as the timeline of the divergence of these two genres.

I have chosen to refrain from using Western notation throughout this study. This choice

reflects the fact that Western notation does not lend itself to describing what happens during a DJ

set. DJing, after all, is not a music-making activity that requires reading music; there isn’t a music

stand or sheet music to be found during most DJ performances, unless the DJ is accompanied by

live musicians, something Hale explores in her group, Nyumba Muziki, where she DJs alongside

string players and other instrumentalists. These types of performances are outliers, however. Most

club nights consist of a DJ, their equipment, a soundsystem, and the audience. When discussing

music production, I have opted to follow Rick Snoman’s strategy in the Dance Music Manual, and

use the MIDI piano roll in lieu of standard Western notation.

14

While Western notation is able to

depict much of what happens in the course of a house track (e.g., drum patterns, chords, melody),

the MIDI piano roll is the lingua franca of modern electronic music producers and is able to convey

much of the same information as Western notation (e.g., pitch, rhythm, harmony, volume). Readers

who are familiar with Western notation but unfamiliar with reading MIDI should be able to catch

on quickly to reading “the grid” of the MIDI piano roll. Additionally, my choice to notate house

14

Rick Snoman, Dance Music Manual: Tools, Toys, and Techniques, 4

th

ed. (New York:

Routledge, 2019).

12

drum patterns in MIDI follows the University of Indiana’s use of MIDI to depict drum patterns in

popular music.

15

Some writers opt to use Electronic Dance Music (EDM) as a catch-all term for electronic

styles, including house and techno. While on its face the term “EDM” is accurate enough—after

all, house and techno are electronic music styles made primarily for the dance floor—I find it is

important to discuss house and techno as specific entities. House and techno have their own distinct

(but related) histories and sounds. Using “EDM” to describe techno and house music obscures

their unique influences and histories. Additionally, the term “EDM” has come to describe various

sub-genres of electronic music, some of which bear little-to-no resemblence to house music and

pull from a completely different field of influences. To add to the ambiguity of the term, “EDM”

is often used as an analouge for “popular music” of the electronic variety, sometimes sounding

like a poppier (Hale calls it “mayonaise”) version of house and/or techno, but could just as easily

be referring to dubstep, trap, or drum’n’bass. In certain instances there may be utility in using

EDM, and the metamorphasis of the term to encompass a variety of musical styles is certainly

worthy of examination, but in the case of my work I have opted to avoid the term.

15

Indiana University Center for Electronic and Computer Music, “Drum Patterns in Popular

Music,” https://cecm.indiana.edu/361/drumpatterns.html.

13

CHAPTER 2: FLOOR PLAN

The Genesis of House in Chicago

“I view house music as disco’s revenge” -Frankie Knuckles

1

Although my work is centered around Detroit, the story of house music begins in Chicago.

Understanding the genre’s origin story will provide context for later discussions about house music

in Detroit. The two cities and the electronic music they are known for, house and techno, are

inextricable from each other, so a cursory history of house music’s genesis in Chicago is a

necessary starting point.

Looking back to the quote that precedes this chapter, one might ask “Why did Frankie

Knuckles view house as disco’s revenge?” Well, on July 12, 1979, Chicago radio DJ Steve Dahl,

a transplant from Detroit, carried out the so-called “Disco Demolition Derby” in the middle of a

double-header baseball game between the Chicago White Sox and the Detroit Tigers at Chicago’s

Comiskey Park. As part of the promotion efforts, fans were offered discount tickets to the games

if they brought a disco record to be sacrificed. Despite the stated target of disco, patrons brought

soul and R&B records as well. To Vince Johnson, an usher during the game who would eventually

become a producer of house music, it seemed that any black genre was eligible for incineration.

As Dahl took to center field, dressed in army fatigues and riding in a camouflaged Jeep, the

militaristic overtones were clear. After the detonation of more than 100,000 records, hundreds of

intoxicated—seemingly all white—fans rushed the field to revel in the ashes of black music. The

1

Bill Brewster and Frank Broughton, Last Night a DJ Saved My Life: The History of the Disc

Jockey (New York: Grove Press, 1999), 312.

14

situation was out of control and the field was ruled unfit for play, causing the second game to be

forfeited to the Tigers.

2

The underlying racism and homophobia that fueled such an aggressive and public display,

reminiscent of the Nazi book burnings in the 1940s, was thinly veiled beneath a supposedly “race-

neutral” critique of disco music and culture. Although Dahl claims he was not motivated by racism

and homophobia, we must consider that disco is a genre incubated within the primarily gay and

black club scenes in New York and other major cities. The “disco culture” Dahl sought to destroy

was invariably of color and gay, and the pile of records in center field served as an effigy for those

communities.

3

Disco’s popularity in the late ‘70s threatened the white Chicago rock scene culturally and

economically. Disco records topped the charts and rock radio stations, including WDAI in

Chicago, had started programming all disco formats. Disco was rapidly growing and the rockers

felt the squeeze, opting to ignore the music industry practices and machinations that promoted

commercial disco while taking aim at the sound and culture of the music. Micah Salkind writes

that “as disco skyrocketed in popularity, critics and promoters alike noticed that whitened, hetero-

masculine rock music and culture could be gainfully promoted as its antithesis.”

4

For most, the

message of the Disco Demolition was clear: the incursions of disco into white popular culture

would not be tolerated. The cultural fallout of the event resulted in a severe waning of major label

and radio support of disco.

5

It seemed, at least for the moment, that disco was dead.

2

Simon Reynolds, Energy Flash: A Journey Through Rave Music and Dance Culture (Berkley:

Soft Skull Press, 2012), 15; Micah Salkind, Do You Remember House? (New York: Oxford

University Press, 2019), 25-33.

3

Salkind, 26.

4

Salkind, 25.

5

Salkind, 32.

15

House music emerged from the underground against this backdrop of “discophobic”

displays from rock radio DJs and broader cultural hostility. In early 1977, Knuckles was recruited

to DJ for a new club opening in Chicago called The Warehouse, which would become the

namesake of house music despite only being open for a few years.

6

In March of that year, Knuckles

left New York, where he had been DJing alongside Larry Levan at a gay bath house called the

Continental Baths and at a more traditional club named SoHo, to play the opening two nights at

The Warehouse.

7

Levan was originally contacted for the gig but was unavailable, focused on his

new club in New York and planning the concept for what would become the Paradise Garage club,

so he recommended Knuckles for the job.

8

Both nights at The Warehouse were a success and Knuckles ended up with a permanent

gig, sweetened by financial interest in the club. Within a few years, both Knuckles and the club

were famous in Chicago and the name “house music” was being used as short hand for “music

played at The Warehouse.” Despite the 600-person capacity of the club, on a good night one could

see as many as 2,000 packed into the famously dark, repurposed factory space. The patrons were

almost all black and the majority were gay (both sexes). The scene of a majority black gay club

with a black gay DJ at the helm led some in the wider Chicago club community to brand the

Warehouse and Knuckles as “fag music,” continuing, and arguably making more overt, the strains

of anti-gay rhetoric leveled toward disco.

9

6

Reynolds, 16-17.

7

Brewster and Broughton, 314.

8

Brewster and Broughton, 314.

9

Brewster and Broughton, 313-317.

16

Figure 2.1 Outside view of The Warehouse, 206 S Jefferson St, Chicago, IL.

10

Nights at The Warehouse were marathon sessions. Patrons would arrive around midnight

on a Saturday and, fueled by the music’s energy (as well as stimulants and hallucinogens), the

party wouldn’t stop until midday on Sunday.

11

At first, Knuckles was spinning disco and R&B

records from labels like SalSoul and Philadelphia International, but, by 1981, the post-Demolition

decline in disco and dance music output, especially from the major labels, created a shortage of

new material.

12

Knuckles recounts that “by ‘81, when they had declared that disco is dead, all the

record labels were getting rid of their dance departments, or their disco departments, so there was

no more up tempo dance records, everything was downtempo. That’s when I realized that I had to

10

Photographer unknown, accessed April 6, 2021 from https://www.musicorigins.org/item/the-

warehouse-the-place-where-house-music-got-its-name/.

11

Reynolds, 17.

12

Brewster and Broughton, 316.

17

start changing things to keep feeding my dancefloor. Or else we would have had to end up closing

the club.”

13

Thus, house music was born of necessity and required both ingenuity and experience to

execute. With the help of Erasmo Riviera, a friend who was studying audio engineering, Knuckles

began experimenting with a reel-to-reel tape machine to make new edits of older music. With a

keen and creative ear for what would work on the dance floor, Knuckles extended intros and

breaks, re-arranged song sections, and added additional sounds that breathed new life into records

that many perceived to be dead. He became proficient in his re-editing technique and in the early

‘80s he was playing his new edits at clubs and parties alongside post-disco records from New York

and obscure Italo-disco imports from Italy and other European countries. In addition to tape

techniques, Knuckles employed DJing techniques he had picked up in New York, using cutting,

mixing, segues, and sound effects to weave an eclectic sonic tapestry and create one-of-a-kind

moments on the dance floor. Although cultivated earlier in New York, these techniques were new

to Chicago audiences.

14

13

Brewster and Broughton, 318.

14

Broughton and Brewster, 317; Reynolds, 17.

18

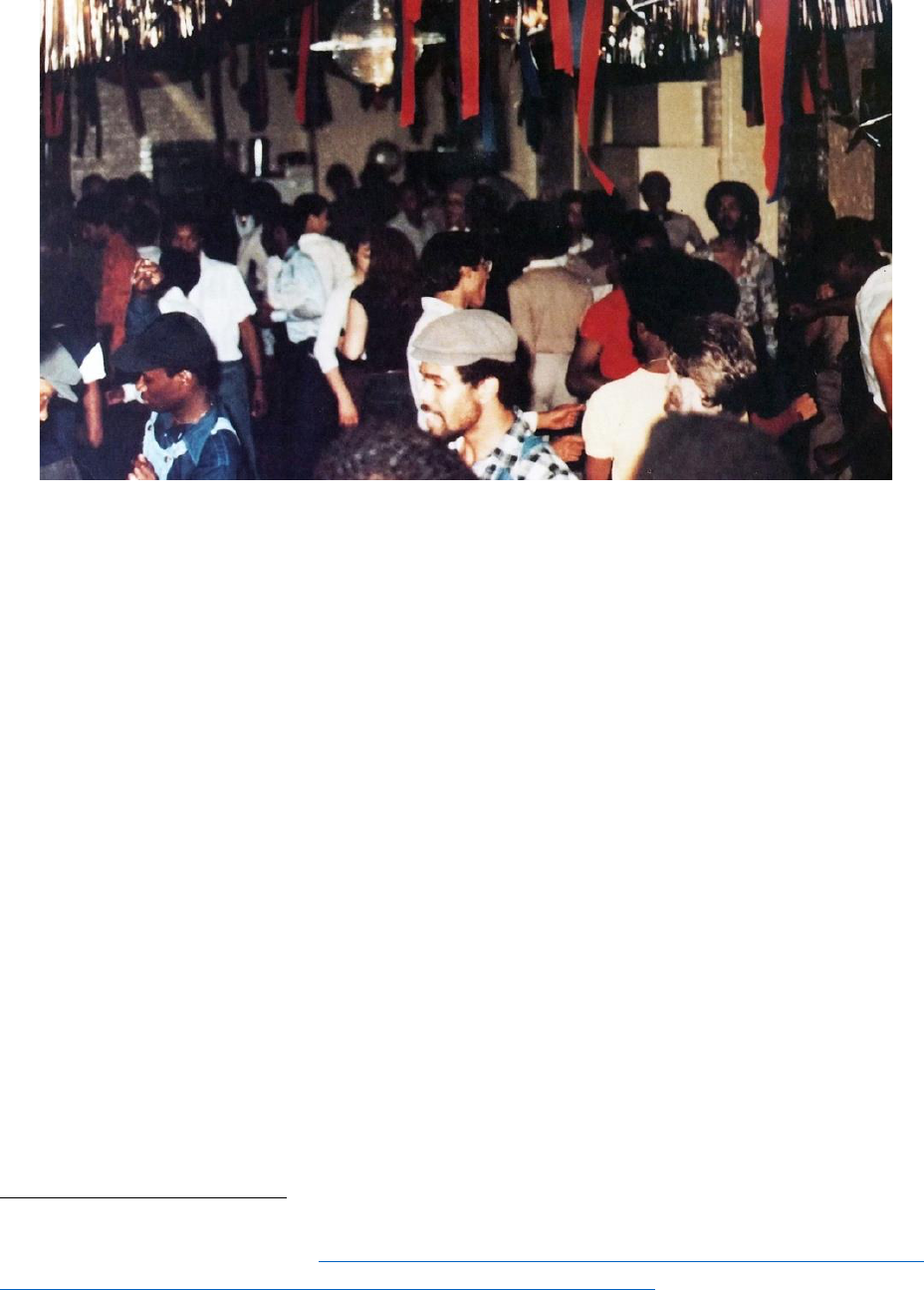

Figure 2.2. Club-goers reveling inside The Warehouse.

15

As the tape edits morphed into increasingly complex remixes that supplemented familiar

songs with completely new basslines, synth textures, and drum patterns, DJ technique was also

undergoing a metamorphosis. The blossoming Chicago party scene offered regular events

occurring at several clubs in the city. The competition to innovate in the DJ booth led to more

complex techniques, like Ron Hardy’s dramatic EQing (cutting and reintroducing frequencies to

emphasize certain moments in a song), signature sound effects such as Knuckles’s steam

locomotive, and the incorporation of live drum machines into the DJ setups of Knuckles and Farley

“Jackmaster” Funk. The novel sounds emanating from clubs like The Warehouse, The Loft, The

Music Box, and The Playground inspired others to produce music of their own that emulated the

mixes and re-mixes that they were hearing. In just a few years, the stylistic indicators of classic

Chicago house music would codify into a recognizable genre that would see continued innovation

15

Frankie Knuckles Foundation: https://www.wbez.org/stories/what-was-it-like-to-dance-at-the-

warehouse-club-in-chicago/5abf2722-abac-47ea-804e-1ff1ea154c00.

19

by producers from Detroit, New York, and Europe.

16

These indicators included a rhythm track

(likely made with a Roland 909 drum machine) consisting of a pounding four-on-the-floor kick

drum (a.k.a. Farley’s Foot, influenced by disco kick drum patterns), drum machine claps on beats

two and four, sizzling syncopated hi-hats emphasizing the “and” of every beat, synthisizer chords,

powerful synth bass, and “diva” vocals—all typically delivered at around 120 beats per minute.

17

Figure 2.3. Basic 2 house drum pattern, expressed in MIDI notation by author.

“On and On”

“On and On,” by Jesse Saunders and Vince Lawrence, is widely recognized as the first

house track released on vinyl. Written in 1983 and released a year later via Saunders’ newly minted

Jes Say label, the records were pressed at Precision Printing Plant, Chicago’s only record pressing

plant at the time.

The plant had been recently purchased by Larry Sherman, who would go on to

found the Trax record label in reaction to the demand for house music.

18

Trax would become an

important label in Chicago house music, releasing numerous landmark records, but its reputation

16

Reynolds, 17-18; Broughton and Brewster, 321-327.

17

This list is my own. For a great explanation of the elements of classic Chicago house and

several popular subgenres see “The ingredients of a classic house track,” Vox, youtube video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FrqIA0PpAv8&t=499s.

18

Reynolds, 17-18; Broughton and Brewster, 321-327.

20

was tarnished by shady deals, poor quality pressings, and mistreatment of artists, many of whom

were foundational to the development of house as a genre.

19

“On and On” sparked many upcoming Chicago producers, but the reason is not exactly

flattering. Revolving around a sample of “Space Invaders,” by the Australian group Player One (a

song based on the music for the arcade game, Space Invaders) and a basic rhythm track, “On and

On” was a hit despite its rough mix and unpolished production technique.

20

The volume levels of

the vocals vary, the transitions are choppy, and the overall mix sounds more like a demo than a

fleshed-out production. But in spite of its flaws, it remains a milestone track. Chicago house

producer Marshall Jefferson (responsible for the dance floor anthem “Move Your Body”) explains,

“That’s what inspired everybody about Jesse. They saw somebody make it big but not be great.

When Jesse did his stuff, everybody said, ‘Fuck, I could do better than that!’”

21

Despite Jefferson’s dig at “On and On,” it remains a touchstone for many DJs and

producers. The Godmother of House music, Detroit’s Stacey “Hotwaxx” Hale, cites the influence

and popularity of “On and On.”

22

The use of a recognizable sample, one that young people would

likely know from the video game, provided a relatability and familiarity to the house music style

that was developing. The ascending bass line that anchors the song is an extremely catchy

earworm, which imitated disco bass lines using octave jumps throughout—a motif that can be

heard in the chorus of Abba’s “Gimmie, Gimmie, Gimmie” and The Jackson 5’s “Blame It On the

19

Marcus K. Dowling, “Inside Trax Records: Why Chicago’s House Originators are Fighting for

Reparations,” MixMag, October 19, 2020. https://mixmag.net/feature/trax-records-chicago-

house-originators-payment-larry-sherman/.

20

Brewster and Broughton, 327; https://www.whosampled.com/sample/153639/Jesse-Saunders-

On-and-On-Player-(1)-Space-Invaders/.

21

Brewster and Broughton, 327.

22

Author’s interview with Stacey Hale, see Appendix.

21

Boogie,” two popular disco tracks from the late ‘70s. Instead of saving the most exciting part of

the bass line for the chorus, Saunders’s use of the repeating octave bass throughout the song

signaled a departure from pop/disco conventions.

Figure 2.4. Author’s MIDI transcription of the eight-bar bass loop from “On and On.”

While “On And On” opened the door for subsequent waves of house producers, it was

Jamie Principle’s work that set the high-water mark for production. Born Byron Walton,

Principle’s background in drums and sound engineering resulted in crisp, well-crafted productions

that often pulled from a different field of influences than disco-indebted tracks of the era, such as

Marshall Jefferson’s “Move Your Body” (1986), Chip E’s “Like This” (1986), or Farley

Jackmaster Funk’s “Love Can’t Turn Around” (1986).

23

Principle’s musical guideposts of Prince,

David Bowie, the Human League, and Depeche Mode informed classics such as “Your Love”

(1985) and “Waiting On My Angel” (1986). The lush synth sounds that Principle chose are similar

to Depeche Mode and Human Leaugue’s sound selections, Principle’s drum programming evokes

Prince’s work with the Linn drum machine, and the vocals are reminiscent of Bowie’s “White

Duke” era of soul. Principle’s tracks had been circulating on cassette tape years before being

23

Brewster and Broughton, 327.

22

pressed to vinyl, before the creation of “On and On,” and by the time “Your Love” and “Waiting

On My Angel” made it to wax they already had a reputation among Chicago DJs.

24

Following Saunders’s and Principle’s landmark tracks, house music production exploded

in Chicago, resulting in a trail of hits including Lil’ Louis’s “French Kiss” (1989), JM Silk’s

“Music Is The Key” (1985), and the first house record to reach number one on the UK charts,

Steve Hurley’s “Jack Your Body” (1986). Almost immediately, Detroiters were in on the action

as the music traveled via radio from stations like WBMX and WGCI, and through trips Detroit

DJs and producers took to Chicago clubs and record stores. Thus, although the floorplan for house

music was drawn in Chicago, a strong foundation would be built in Detroit.

24

Brewster and Broughton, 327.

23

CHAPTER 3: FOUNDATION

House Comes to Detroit

Theoretical Notes

Mark Butler conceptualizes DJ equipment as a series of “mediated interfaces,” a useful

approach for understanding what it is that Hale and other DJs are doing beyond simply playing

records. Interface, for Butler, denotes any equipment used to perform live, which, depending on

the performer, could involve analog turntables, digital turntables, drum machines, synthesizers,

mixers, laptop computers, and various MIDI controllers.

1

Interfaces are described as “sites of

possibilities, rather than as pieces of hardware that generate outcomes determined by their physical

properties,” driving home the idea that human mediation is an essential feature of electronic music

performance. Mediation, therefore, is understood as the dynamic relationship between the

performer and the recorded sound.

2

Furthermore, Butler identifies two “axes of mediation,”

between the performer and the sound he or she creates and between the performer and the audience.

In the example of Stacey Hale’s a live-streamed performance where there is no in-person audience

(examined later in this chapter), the primary focus is on the first axis of mediation, the relationship

between the performer and the sound being created.

Hans and Theo Bakker look at the DJ performance through a semiotic lens, arguing that

DJing is an example of “the pervasive human ability to engage in symbolic communication and

in meaning-making (i.e. semiosis).”

3

Hale’s command of her equipment, knowledge of the

1

Mark J. Butler, Playing with Something That Runs: Technology, Improvisation, and

Composition in DJ and Laptop Performance (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 70.

2

Butler, 72.

3

Hans Bakker and Theo Bakker, “The Club DJ: A Semiotic and Interactionist Analysis,”

Symbolic Interaction 29, no. 1 (Winter, 2006): 71-82.

24

different venues and DJs, and use of evocative and powerful vocal samples makes her performance

an enlightening case study that illuminates the intricacies of a DJ performance and bolsters the

work of Butler, and Hans and Theo Bakker.

Ken Collier: The Godfather

“Ken was our Larry Levan, our Frankie Knuckles, our Tee Scott,

and Ron Hardy, all rolled into one.” -Stacey “Hotwaxx” Hale, Godmother of House Music

4

There are few figures in the history of Detroit music that have been as loved, lauded, and

revered as Ken Collier. Before his untimely death in 1996 due to a diabetic condition, undiagnosed

for most of his life, Collier had cemented a legacy in the city of Detroit spanning nearly twenty-

five years.

5

More than half of his life was dedicated giving Detroit some of the most awe-inspiring

DJ mixes, cultivating seminal clubs and spaces for the gay community, and mentoring of two

generations of influential Detroit DJs and producers including (but not limited to): Stacey Hale,

Delano Smith, John Collins, Alan Oldham, Al Ester, Juan Atkins, Eddie Fowlkes, Kevin

Saunderson, Kelli Hand, and Mike Huckaby.

6

Throughout his life, he remained steadfastly

dedicated to his community in Detroit, but Collier’s profile was starting to rise internationally just

before his death, with a rousing set at the Tresor club in Berlin in 1995 and a forthcoming booking

at that city’s Mayday festival.

7

4

Marke B., “Ken Collier: The Pivotal Figure of Detroit DJ Culture,” Red Bull Music Academy,

May 24, 2018, https://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2018/05/ken-collier.

5

Carleton S. Gholz, “The search for Heaven,” Detroit Metro Times, July 14, 2004,

https://www.metrotimes.com/detroit/the-search-for-heaven/Content?oid=2179150.

6

Marke B., ”Ken Collier: The Pivotal Figure of Detroit DJ Culture.”

7

Sicko, 31; M. Terrence Samson, “Legendary House: Detroit's Own Ken Collier Talks About

His Life in Music,” Kick!, April, 1995, http://detroitsound.org/artifact/ken-collier/.

25

In the years since his death, the narrative of techno and “The Belleville Three” have

overshadowed Collier and other pioneering progressive/house Detroit DJs. Only passing mention

of Collier is made in Brewster and Broughton’s Last Night a DJ Saved My Life and Reynolds’s

Energy Flash. When Collier is mentioned, he is situated within larger discussions surrounding

early techno, framing Collier as a supporter of the nascent genre and as an influential Detroit figure

but ultimately placing the focus upon on those he mentored. Observers more attuned to Detroit’s

DJ history—like Techno Rebels author Dan Sicko, Detroit Sound Conservancy founder Carleton

Gholz, and veteran DJs in the Detroit scene like Alan Oldham, John Collins, and Stacey Hale—

have pointed to Collier’s direct influence on techno and house music in Detroit and his legacy as

a mentor in more depth.

8

Hopefully, this chapter will bolster efforts to recognize Collier as a central

figure of the history of electronic music and DJ culture in Detroit and acknowledge his impact

beyond the early days of techno.

It is true that Collier mentored the young Detroit techno scene’s DJs and producers, taking

trips to Chicago to see Frankie Knuckles, and it is true that he was one of the first to play early

techno tracks. At Todd’s, a bowling-alley-turned-dance-club owned by an interracial gay couple

and one of many clubs where Collier held residencies, Collier broke (played for the first time)

songs like Model 500’s (aka Juan Atkins) “No UFO’s” and Derrick May and Michael James’s

“Strings of Life.”

9

Collier certainly deserves to be mentioned in the origin story of techno, but that

shouldn’t obscure the fact that house music was at the core of his taste as a DJ. In a 1995 interview

8

Gholz, “The search for Heaven,” and Sicko, 31; see list of interviews in appendix for more

commentary from Detroit DJs.

9

Reggie Dokes, “A New Year with Eddie Fowlkes,” God Said Give ‘Em Drum Machines:

Behind the Scenes, Podcast Audio, January 1, 2021. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/a-

new-year-with-eddie-fowlkes/id1534159844?i=1000504077417. Eddie Fowlkes recounts one of

these trips at the 10 minute mark.

26

with KICK! Magazine, a black LGBT publication, Collier points to Knuckles and The Warehouse

as a primary influence, as well as Larry Levan and Tee Scott, two DJs important to the house music

scene in New York. As for his tastes in house music, Collier says “I like strong, vocal, underground

sounds. Not—there aren’t really many male, good singers, most of them just do a lot of screaming.

There are a few…But there are a lot of females, strong female house artists always. If she’s

screaming the right note, then the message usually gets in.”

10

Collier was born on January 9

th

, 1949, to parents who had migrated separately from the

south to Detroit as teenagers. The household was steeped in the legacy of two important Detroit

musical traditions: the Black Bottom neighborhood, known for its thriving jazz scene through the

1930s and 1950s; and Berry Gordy’s Motown records, which became one of the most important

record labels of all time. Another big musical influence in the house was gospel. According to

Ken’s brother Greg, who also became a great DJ in his own right, their mother was a “traditional

Christian” who didn’t care for secular-sounding gospel music. While Ken sang in choir, he also

soaked up the gospel music that straddled the line between secular and sacred.

11

This early

influence of gospel shows in Ken’s perception of music’s purpose: for Collier, “in music there

should always be a message…it should leave you with something.” The titles of some of his

favorite house tracks at the time of the KICK! interview, “Testify,” “Rejoice,” and “Rise to the

Top,” clearly incorporated gospel messages and sounds.

12

Collier’s start as a professional DJ came in 1973 with an organization called True Disco,

which included two other foundational DJs on Detroit’s gay (and primarily black) club circuit,

10

Samson, “Legendary House.”

11

Marke B., “Ken Collier.”

12

Samson, “Legendary House.”

27

Morris Mitchell and Renaldo White. However, Greg Collier remembers Ken playing records as

far back as 1969 and there is documentation of Ken playing at house parties like Zana’s Place, put

on by Zana Smith, in the years preceding his time with the True Disco crew.

13

In the early ‘70s,

DJ technique was quite different from what we see in the DJ booth today. The technology was

limited, the now-standard setup of two turntables and a mixer wouldn’t be utilized to mix records

together and play without breaks until the middle of the decade. In the earlier years, DJing involved

simply playing one record after another with breaks in between, with the DJ talking over the

microphone to introduce the next record and recap which one just finished.

14

Collier was the first Detroit DJ, and one of the first nationwide, to present a continuous

mix of music. Greg Collier recounts Ken using the mixing technique early on in Chicago: “Even

when we started doing it in Chicago, everybody played one record, then they played another

record, there was no mixing and continuous music. When we started doing that, it just opened up

a whole different door.”

15

Even before Knuckles migrated from New York to work at The

Warehouse, Collier had showed Chicago crowds the potential of this groundbreaking mixing

technique.

Collier perfected his technique of mixing two records together to cut out breaks between

the music while he was the resident DJ of the Chessmate, an after-hours gay club located near

Palmer Park, one of Detroit’s gay neighborhoods, and subsequently at Detroit’s Studio 54.

16

From

13

Marke B., “Ken Collier.”

14

Stacey Hale interview, see Appendix.

15

Carleton Gholz, “Greg Collier: #RecordDet Interview,” Detroit Sound Conservancy, Audio,

October 26, 2015. http://detroitsound.org/artifact/greg-collier/.

16

Not to be confused with the club of the same name that existed in New York.

28

there, Collier DJed at several important clubs in the city. There was Todd’s, the Downstairs Pub

(run by Zana Smith of Zana’s Place), the Rich and Famous, and Bookie’s.

But the club Collier is most often associated with is Club Heaven. Located at 7 Mile Road

and Woodward Avenue, it was a quintessential after-hours establishment (not open before 2 AM)

and featured Collier as a longstanding resident DJ. The club served a primarily black and gay

audience, although crowds were mixed, sometimes featuring famous celebrities of the day

(including a young Madonna). The legacy of the club is multi-faceted. From its opening in 1984

until its closure a decade later, Heaven served an important function within the gay community in

Detroit, a community in the throes of the AIDS epidemic.

Damon Percy, head of Detroit Sound Conservancy’s campaign to restore the club’s sound

system, remembers the importance of Club Heaven to the community. “The club was legendary.

It was a safe space where we could be free and be who we wanted to be…At that time during the

early ‘90s it was still not as open as it is now…we were taking that step to be free.”

17

Inside Heaven

it was a sanctuary of self-expression, but getting to and leaving from the club could be risky. Percy

recalls: “This was East 7 Mile and Woodward. You could still get beat down. We had to fight a

lot, too. When you came out in the sunlight, people going to church would see you. Straight people

were sometimes waiting to jump you.”

18

For its patrons, the risk was unquestionably worth it. Part of the reason was Club Heaven’s

sound system, a state-of-the-art setup unrivaled by anything else in Detroit at the time. Mike Fotias,

president of Audio Rescue (a company that now provides sound for the Detroit Jazz Festival and

17

Amanda LeClaire, “When Heaven was a Dancefloor in Detroit,” WDET Culture Shift, July 10,

2018. https://wdet.org/posts/2018/07/10/87001-when-heaven-was-a-dance-floor-in-detroit/.

18

Marke B., “Ken Collier.”

29

the dance music festival Movement), explains that, at the time, “you couldn’t just order a complete

system like now. Heaven’s sound was built up brilliantly, level by level, from different elements

that you really had to seek out. That’s why the effect was so memorable.”

19

The powerful and well-

designed sound system was at the core of the experience; other clubs utilized systems geared

toward rock acts while Heaven’s system was designed specifically for the music that DJs at the

club were playing. This process of building up a custom sound system for a dance club and the

music that was played there was similar to what Alex Rosner and David Mancuso had created at

The Loft in New York City during the mid-‘70s. The precise and powerful speaker system set Club

Heaven apart from other nightlife experiences in the city. The club represents another example of

new genres and new spaces spurring technological innovation and adaptation.

20

The state-of-the-art system and vibrant community coalesced in another defining feature

of the Club Heaven experience, “The Circle.” The Circle was, in part, exactly what it sounds like.

A crowd would form a ring on the dance floor and dancers would take turns in the middle, dancing

in early kicking style, a dynamic move associated with vouging-style dance developed in the black

gay community in the early ‘80s and popularized by Madonna with her 1990 hit “Vogue.”

21

In a

video from a night at Club Heaven in 1991, available on Youtube, The Circle can be seen in action

and Collier can be heard DJing and MCing the proceedings of the dance contest, making sure that

security gives the circle enough space, polling the crowd about performances, and announcing the

19

Marke B., “Ken Collier.”

20

Leticia Trandafir, “Moments in Music: 8 Sound Systems that Changed the World,” LANDR,

July 16, 2016. https://blog.landr.com/8-best-club-sound-systems-time/.

21

Madonna attended a few nights at Club Heaven, along with other celebrities like Dennis

Rodman and Bobby Brown. Heaven was renowned as a destination dance club, even for the

celebrity elite; Marke B., “Ken Collier.”

30

contestants.

22

Dancers take turns for rounds of about twenty to thirty seconds, and several of the

contestants are clearly adept “kickers,” displaying athleticism, flexibility, and keen sense of

rhythm as the kicks accentuate the hand claps on beats two and four of the music. The contestant

called “Skyscraper” is particularly dynamic, with his long legs and tall, wiry frame the nickname

is fitting, and his long limbs make his kicks all the more dramatic (see figure 3.1). From the DJ

booth, Collier would communicate to the crowd by playing certain records that would indicate it

was time to circle up and let dancers show off.

23

This musical signaling shows the syncretic

relationship between DJ and dancefloor that developed at the club. Collier was the maestro, and

the crowd his orchestra.

22

DJ Tony Peoples, “Club Heaven 1991 in Detroit 7 mile and Woodward Ken Collier Part 2 of

2,” youtube video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FEvYBVw0Qpc&t=45s.

23

Marke B., “Ken Collier.”

31

Figure 3.1. Dancer, “Skyscraper” in “The Circle,” at Club Heaven, 1991.

24

It seems that for Collier, this feel for the crowd was innate, or at least it felt that way to

him. On the role of the DJ, Collier said: “DJs are the performers, entertainers, and you have all

these folks that you have to keep dancing all night long. So, you have to become a mind reader,

you have to look out to your audience, see what they’re doing…You have to have the ability to

know what to do. I’ve always had that.”

25

Emphasizing Collier’s years of experience and his

impact as a DJ, Dan Sicko writes: “Collier played through decades of parties and clubs, using his

knack for knowing exactly what to play to transform simple nights out into religious

experiences.”

26

The musical and spiritual alchemy that Collier was able to engineer from the DJ

booth shows that the moniker of “The Godfather” was hardly hyperbole.

According to Collier himself, and confirmed by Stacey “Hotwaxx” Hale, Collier was given

the “Godfather” moniker by none other than The Electrifying Mojo.

27

Mojo was a trailblazing

radio DJ, appearing on several Detroit stations through the 1970s and ‘80s, and his “Midnight Funk

Association” segment became a signature. Membership to the association even came with

membership cards. Described by Juan Atkins as “an underground cult hero,” Mojo’s shows were

adventurous both musically and programmatically.

He also opened his platform to younger DJs

(both Collier and Hale made mixes that Mojo would play on his shows in the early ‘80s), granting

them, and the new music they were breaking, a serious endorsement. Having Mojo play one of

24

Photo by DJ Tony Peoples, video available at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FEvYBVw0Qpc.

25

Samson, “Legendary House.”

26

Sicko, 31.

27

Marke B., “Ken Collier.”; Sampson, “Legendary House.”

32

your tracks or mixes was the ultimate Detroit seal of approval. Having Mojo give Collier the

moniker of “The Godfather” was even weightier.

28

The title of “The Godfather” works on two levels. First, Collier was extremely

accomplished and skilled in his own right, widely regarded as the city’s foremost DJ during his

career. Derrick May recounts being blown off the decks by Collier during a party called the Pink

Poodle, at the Downstairs Pub in 1981: “We’re playing 7-inch singles on decks with the rubber

mats still on them, not one person is dancing. Ken Collier arrives, puts a real slip mat on, cues up

a record, pulls back and boom. In ten seconds, the floor was full.”

29

Secondly, Collier’s legacy of

mentorship is vast and deep. Famously gracious to younger DJs, Collier would often let up-and-

coming DJs hone their craft during his sets. His brother Greg recalls: “That’s the type of DJ Ken

was. He opened up his heart and his turntables and would let everybody come in there and play at

his clubs when he played. He gave everybody an opportunity. And I think that’s something that he

should always be remembered as.”

30

The sheer number of careers that he helped flourish is

impressive—even more impressive is that many of his mentees went on to make history

themselves, including the Godmother of House, Stacey “Hotwaxx” Hale, the subject of the next

section of this chapter.

Delano Smith is another example of a DJ that Collier mentored who would go on to make

distinct contribution to Detroit’s electronic music legacy. Smith started DJing before the inception

of techno in Detroit; in 1981 he was holding a residency at Club Luomo at only eighteen years old.

Although Smith was, and is, a central figure to the scene, he is not included in the mainstream

28

Ashley Zlatopolsky, “Theater of the Mind: The Legacy of the Electrifying Mojo,” Red Bull

Music Academy, May 12, 2015; Marke B., “Ken Collier.”

29

Brewster and Broughton, 350.

30

Gholz, “#RecordDET Interview: Greg Collier.”

33

histories of the origins of techno in Detroit despite Atkins and others citing Smith as an

inspiration.

31

His omission from popular accounts of techno history could be, at least in part, due

to his five-year hiatus from music in the mid-‘80s, just as techno was starting to come into its own

(he started to notice the saturation of new DJs in the scene was affecting his ability to find paying

gigs). Once Smith returned to DJing in the early ‘90s, he more than made up for lost time as he

honed his craft and added music production to his skillset. In 2002, Smith was featured on a

landmark compilation with tracks from noted Detroit colleagues like Norm Talley, Eddie Fowlkes,

Rick Wilhite, and Theo Parrish titled “Detroit Beatdown (Volume One).” This compilation, and

Smith’s track, “Metropolis,” would show that Detroit producers had range beyond fast and hard

techno tracks. Slow, melodic, and brooding, the “Detroit Beatdown” sound was another novel

iteration of techno and house pioneered by Detroiters.

32

For Smith, seeing Collier perform was the impetus to learn the fundamental DJ techniques

of mixing and beatmatching. During Smith’s residency at Club Luomo, Collier would take the

decks to close the night, which meant an opportunity for a young Smith to observe Collier up close.

This experience was formative and since Smith encountered Collier on the “straight” scene, their

relationship is a reminder that Collier’s influence extended beyond the gay club scene. Smith

learned by observation and osmosis, but Collier also provided some direct technical advice. Smith

recounts: “He taught me things that have stayed with me throughout my career. He told me to pitch

31

Here, “mainstream histories” refers to Brewster and Broughton’s Last Night a DJ Saved My

Life and Simon Reynolds’s Energy Flash. These are the two of the most popular texts that

address house and techno, among other electronic music genres.

32

Adam Grundey, “Meet Underground Detroit Legend Delano Smith,” Red Bull Music, October

10, 2016. https://www.redbull.com/mea-en/meet-detroit-underground-legend-delano-smith.

34

down the record gradually when I was mixing and he taught me to keep the volume way down in

my headphones, just enough in my cue ear to match the mix with the floor.”

33

Much of Collier’s work behind the decks remains on tape in personal collections like that

of DJ and archivist Cynthia “DJ Cent” Travis, not yet fully digitized and available to the public.

There are a few publicly available Ken Collier DJ mixes on YouTube, SoundCloud, and in the

archive of the Detroit Sound Conservancy. Listening to the sets that are available reveals Collier’s

penchant for powerful, soul-stirring, and often euphoric vocal house, nearly all of which features

female vocals. Smooth mixing and blending technique accentuates stellar track selection. Many

listeners left comments on a recording of Collier at Heaven in the early ‘90s that is on SoundCloud.

User “fungamesandplay” asked for a track identification for the one of the songs in the mix, an

indicator that Collier’s taste still resonates with modern audiences. For others, like Duane Folmar,

listening to the set transported him back to attending nights at Club Heaven. He commented at

around nine minutes in that “The kicking circle would be in full effect right now!” DJ Eddie Flud

emphasized Collier’s mixing ability: “No where else did you get exposed to the genius of Ken's

Mixing capablities. No Where else where the tunes were A-one at all times! Yes Many Many

Memories! Heaven! where you hear it no better!”

34

Though only the audio is available, one can imagine the fervor that Collier was able to

work up in the club. A set played by Collier at Club Heaven from the early ‘90s provides a

snapshot. Midway through the set, Collier can be heard interrupting the music to call security to

the dance floor (a common occurrence when the crowd would incur on the space for The Circle)

33

Marke B., “Ken Collier.”

34

“Ken Collier- Club Heaven, Detroit (early 90’s) Pt. 1,” Deific Records, audio,

https://soundcloud.com/deificrecords/ken-collier-club-heaven-pt1.

35

before diving right back into the mix.

35

The set displays Collier’s ability to weave together various

house sub-genres and present an array of emotional themes. There are moments of gospel choir

breakdowns, classic house directives to “wave your hands” and “move your body,” melancholic

and yearning deep house, and a downright raunchy sequence at the end of the set featuring “Short

Dick Man,” by 20 Fingers, and “Who’s Dick is This,” by Princess Di.

Taken as a whole, the set is a potent blend of the sacred and profane. Salkind notes this sort

of blend in the work of Knuckles, stating that the “sonic juxtaposition of the sacred (gospel,

spirituals) and the profane (r&b, funk, and disco) became central to the ways that house people

were worshipping under Knuckles’s musical supervision.”

36

Collier displayed this ability as well,

and, as in the example above, explored both ends of the spectrum within a set. For Collier, his

experiences at church held an influence in the way he presented music, saying that “I’ve always

been involved with the church for many many many years. Maybe that’s why it lets me feel, let’s

me feel what I feel with certain records. The way they’ve been delivered that the gospel is right

there in me all the time. I’ve always had it, probably always will have it, till I die.”

37

Knuckles put

the comparison of house music and church as such: “For me, it’s defintely like church. Because

when you’ve got three thousand people in front of you, that’s three thousand different

personalities. And when those three thousand personalities become one personality, it’s the most

amazing thing. It’s like that in church... when things start peaking, that whole room becomes

one.”

38

35

“Ken Collier- Club Heaven, Detroit (early 90’s) Pt. 1,” Soundcloud recording, Deific Records,

https://soundcloud.com/deificrecords/ken-collier-club-heaven-pt1.

36

Salkind, 62.

37

Ken Collier “Kick Interview.”

38

Brewster and Broughton, 312.

36

There are ongoing efforts, by the Detroit Sound Conservancy and others, to preserve

Collier’s legacy and that of Club Heaven. After Collier’s death, friends founded the Ken Collier

Memorial Foundation in 1997 and would organize events, fundraise for diabetes-related causes,

and put on concerts. The organization lasted for almost a decade, disbanding in 2004 under unclear

circumstances.

39

Collier is one of the most consequential figures in Detroit DJ culture, the history of

electronic music, and the history of gay clubs in the city of Detroit. As the sands of time continue

to fall, it is imperative that observers continue to acknowledge the contributions and cultural

importance of figures like Collier. It is unconscionable that a man with so much importance to the

history of Detroit music is treated by some texts as a mere footnote to techno, when so many of

those who were actually there to know him (including those who pioneered techno) have recounted

the deep historical, musical, and cultural impact of “The Godfather” before, during, and after

techno’s inception.

Stacey Hale: The Godmother

“I didn’t do it to be the first woman doing it, I did it because it was inside of me.”

-Stacey “Hotwaxx” Hale

40

Being first may not have been Stacey Hale’s motivation for learning the craft of DJing, but

nonetheless she was, in fact, the first woman to play house music on the radio in Detroit. However,

her legacy in the city goes well beyond breaking barriers on the airwaves. Hale has made an impact

in just about every facet of the city’s house music scene and remains one of its premier DJs,

39

Gholz, “The search for Heaven.”

40

Harley Brown, “Stacey “Hotwaxx” Hale: The Godmother of House Music,” Red Bull Music

Academy, May 23, 2018. https://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2018/05/stacey-hale-interview

37

decades after she got her start. Hale once asked Ken Collier if there was a female DJ of his stature

on the scene. He answered, “Oh, no Miss Stacey, not yet.”

41

Hale replied that it would be her. Now

recognized as the “Godmother” of House music, history has proven her prophetic.

From DJing at Detroit’s storied clubs and radio stations, to mixing and producing records,

to reporting on Detroit music for Billboard, to creating educational programs for young women

and organizing the landmark Detroit Regional Music Conference in the 1990s, Hale’s

contributions are far-reaching, impactful, and enduring. I was lucky (and persistent) enough to

interview Ms. Hale in 2020 and much of this chapter draws upon that interview (the full transcript