PRIVATE HEALTH

INSURANCE

Limited Data Hinders

Understanding of

Short-Term Plans’

Role and Value during

the COVID-19

Pandemic

Report to Congressional Committees

May 2022

GAO-22-104683

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-22-104683, a report to

c

ongressional committees

May 2022

PRIVATE HEALTH INSURANCE

Limited Data

Hinders Understanding of Short-Term

Plans’ Role and Value

during the COVID-19 Pandemic

What GAO Found

One option that may be available to those who lose jobs with employer-

sponsored insurance (ESI) during the COVID-19 pandemic is short-term plans,

which can cover certain health expenses. These plans are generally not subject

to federal requirements for individual health insurance coverage established by

the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), such as restrictions on

basing premiums on pre-existing health conditions and the requirement to cover

10 essential health benefits. Federal requirements for short-term plans are

primarily limited to defining their duration—the length of time a consumer can be

covered by them. States have broad authority and discretion in regulating short-

term plans, and regulation of short-term plans varies across states. For example,

some states have prohibited their sale and some have imposed restrictions in

addition to federal requirements.

GAO found that limited and inconsistent data hinder understanding of the role

short-term plans played during the COVID-19 pandemic for those who lost ESI,

such as whether they were used by consumers as temporary coverage or as a

longer-term alternative to PPACA-compliant plans. Policy researchers and

representatives of national organizations that GAO interviewed said there was a

lack of comprehensive data and information on short-term plans, including data

on how many people enroll in them and for how long. In addition, data collected

on short-term plans varied across the six states that GAO reviewed.

• Two states did not have data on short-term plan enrollment.

• Three states reported fewer than 10,000 enrollees in short-term plans and

trends varied as to whether enrollment increased or decreased.

• One state did not have short-term plans offered from 2019 through 2021.

State officials in the five states with plan sales were not able to report on the role

of short-term plans for consumers, as none of them collected data on the

duration of short-term plan coverage.

Views vary widely about the value of short-term plans to consumers. Officials

from two of the six states GAO reviewed and other stakeholders interviewed said

that short-term plans meet an important need for certain consumers who lost ESI

during the COVID-19 pandemic. They said short-term plans provide additional

options for certain consumers such as those needing temporary insurance until

they become employed again, and those who cannot afford insurance premiums

for PPACA-compliant plans. In contrast, officials in two other states and some

other policy researchers said that short-term plans did not provide good value to

consumers. While most of those GAO interviewed said that short-term plans

often had lower premiums than PPACA-compliant plans, some also emphasized

that short-term plans (1) provided fewer benefits, (2) were not available to those

with pre-existing conditions, and (3) could result in higher total out-of-pocket

costs for some consumers compared to PPACA-compliant plans. In addition,

unlike PPACA-compliant plans, short-term plans are not subject to federal

requirements to provide consumers with key information about their benefits that

would facilitate comparison with other options.

View GAO-22-104683. For more information,

contact

John E. Dicken at (202) 512-7114 or

DickenJ

@gao.gov.

Why GAO Did This Study

Millions of Americans who lost their

jobs during the COVID

-19 pandemic

also lost their ESI.

Short-term plan

insurance was one option for

these

consumers. However, these plans can

be significantly

different from other

health coverage

options for those

losin

g ESI. Therefore, it is important to

understand the role

they play in the

market and for individual consumers.

GAO was responsible

under the

Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic

Security Act for

monitoring the federal

government's pandemic response.

In

th

is report, GAO describes what is

known about short

-term plans and the

role that they might play for individuals

who lost ESI during the pandemic

.

S

takeholder views of the value of

short

-term plans in meeting consumer

needs

are also discussed.

GAO conducted

a literature search and

review of studies on short

-term plans

and conducted interviews with national

organizations such as the National

Association of Insurance

Commissioners.

GAO

also interviewed

seven

policy researchers selected to

include diverse polic

y perspectives

and

stakeholders. This included

(1) officials

from

six state insurance departments

selected to represent

different levels

and type

s of regulation, and (2)

representatives from four organizations

that sell short

-term plans.

Page i GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

Letter 1

Background 5

Data Limitations Hinder Understanding of the Role Short-Term

Plans Played during the COVID-19 Pandemic 9

Views Varied Widely about the Value of Short-Term Plans to

Consumers and as Compared to Individual Health Insurance

Coverage 15

Additional Data Would Enhance Understanding of the Role of

Short-Term Plans and Help States Oversee Insurer Market

Conduct 27

Agency Comments 28

Appendix I Publications on Short-Term Plans 32

Appendix II GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 38

Tables

Table 1: Short-Term Plan Enrollment in Selected States, 2019 and

2020 13

Table 2: Regulation of Contract Period and Renewal for Short-

Term Plans Sold in Selected States, 2020-2021 14

Table 3: Examples of Data and Information about Short-Term

Plans Suggested for Collection from Insurers by

Stakeholders and Policy Researchers 27

Figure

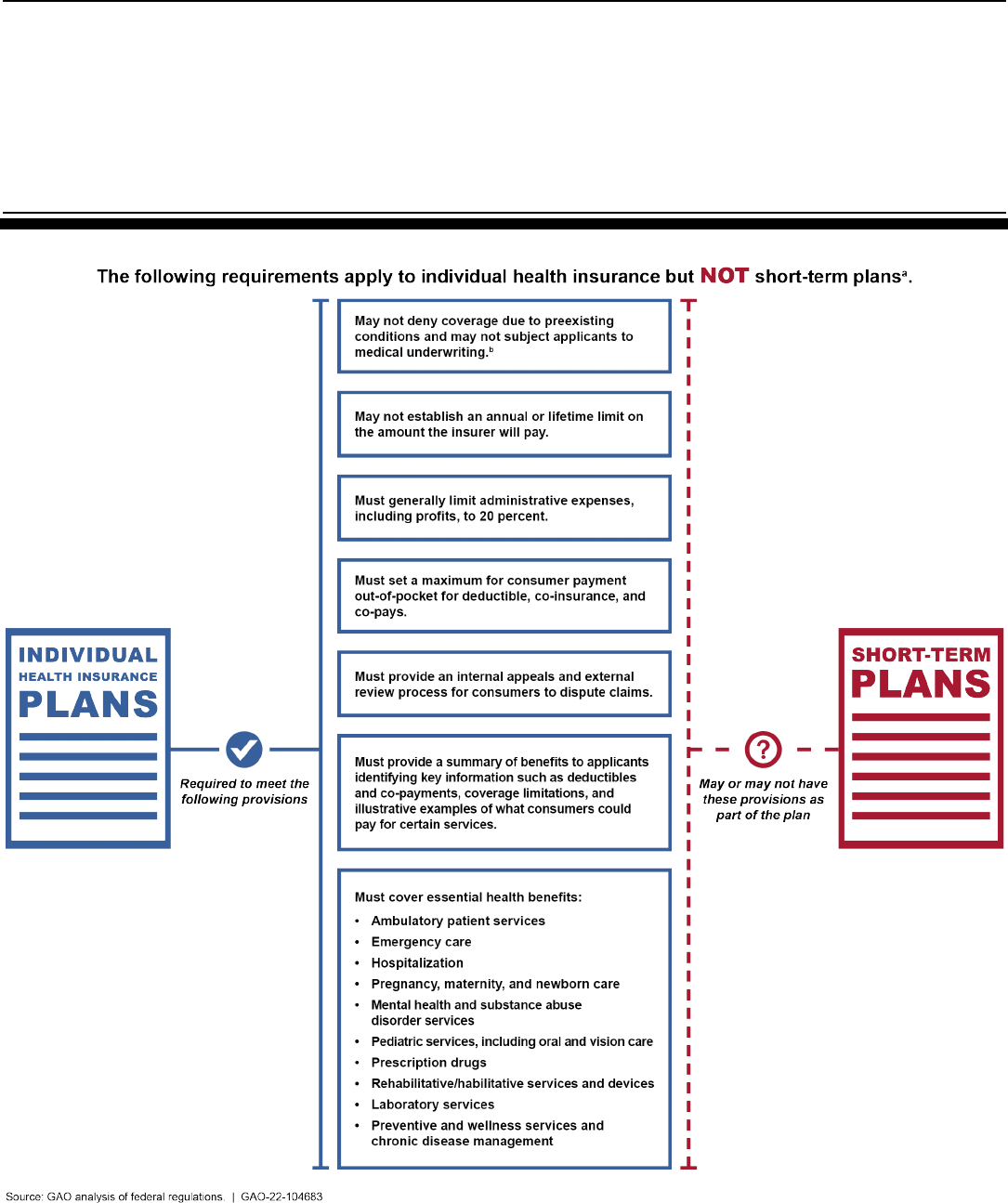

Figure 1: Selected Requirements in PPACA That Apply to

Individual Health Insurance Coverage but Not to Short-

Term Plans 6

Contents

Page ii GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

Abbreviations

ESI Employer-sponsored insurance

NAIC National Association of Insurance Commissioners

PPACA Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

May 31, 2022

Congressional Committees

It is estimated that millions of Americans experienced a disruption in

health insurance coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic due to loss of

jobs that provided employer-sponsored insurance (ESI).

1

Those who lost

ESI had several options for obtaining an alternative source of health care

coverage, including short-term, limited-duration insurance, referred to

hereafter as short-term plans.

2

A short-term plan is health insurance

traditionally designed to fill temporary gaps in coverage that may occur

when an individual is transitioning from one source of long-term,

comprehensive coverage to another.

3

States are the primary regulators of private health insurance, which is

also subject to certain federal standards and minimum requirements.

Federal requirements for short-term plans are primarily limited to defining

their duration—the length of time a consumer can be covered by a short-

term plan and the ability of the consumer to renew the plan—and in 2018

1

In prior work, we reported on estimates of employer-sponsored insurance that suggested

that more than 3.1 million non-elderly adults lost their insurance during the COVID-19

pandemic; some losing this insurance were able to obtain an alternative source of

coverage. GAO, COVID-19: Additional Actions Needed to Improve Accountability and

Program Effectiveness of Federal Response, GAO-22-105051 (Washington, DC, Oct. 27,

2021), 72.

2

Under current regulations, short-term, limited-duration insurance is generally defined as

health insurance that expires less than 12 months after the effective date of the coverage

and, taking into account renewals or extensions, has a duration of no longer than 36

months in total. See 45 C.F.R. § 144.103 (2021). For purposes of this report, we refer to

this insurance as short-term plans.

As GAO has reported elsewhere, other health coverage options subject to federal

regulation include: coverage through a federal or state health insurance exchange

established under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA); Medicaid, a

joint federal-state health financing program for certain low-income and medically needy

individuals; and benefits under the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act

(COBRA) of 1985, which provides certain individuals who lose their employer-sponsored

health coverage with temporary access to continue their coverage for limited periods of

time under certain circumstances. GAO-22-105051.

3

Coverage is long-term if it can be annually renewed without limitation, and it is

comprehensive if it covers a broad array of health care services. Examples of renewable,

comprehensive coverage are ESI, Medicare, and Medicaid, which are renewable each

year for eligible individuals, and cover a broad array of health care services.

Letter

Page 2 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

the limit was extended from less than 3 months of coverage to up to 3

years of coverage.

4

Short-term plans are excluded from the definition of

individual health insurance coverage under federal law and thus are not

subject to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act’s (PPACA)

requirements for health insurance coverage provided by plans in the

individual market (hereafter referred to as PPACA-compliant plans).

5

For

example, unlike PPACA-compliant plans, short-term plans are not

prohibited by federal law from varying premiums based on the individual

consumer’s health status or gender.

Because short-term plans can be significantly different than PPACA-

compliant plans, and because they can be purchased for longer periods

of coverage than previously allowed, it is important to understand the role

they play for consumers in the health insurance market—such as whether

the plans are purchased to fill a temporary need or as longer-term

coverage—as well as the extent to which these plans reduce or defray

consumers’ medical costs during periods of economic downturn—such as

during the COVID-19 pandemic. Understanding the role these short-term

plans play and the extent to which this provides value to consumers is

also important because consumers who buy short-term plans are not

included in PPACA individual market risk pools—the population that buys

individual health insurance coverage in each state—which influences the

4

Federal requirements for the maximum duration of short-term plans have varied over

time, with the latest change increasing the duration from 3 months to up to 1 year with the

option to renew for up to a total of 3 years.

5

See 42 U.S.C. § 300gg-91(b)(5); 45 C.F.R. § 144.103 (2021) (definition of individual

health insurance coverage). See also Pub. L. No. 111-148, 124 Stat. 119 (2010), as

amended by the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111-

152, 124 Stat. 1029 (2010) (hereafter “PPACA”).

For example, PPACA established new requirements for individual health insurance

coverage regarding what benefits must be covered, what costs consumers may be

responsible for, and what information insurers may use to determine the monthly

premiums they charge, but these requirements do not apply to short-term plans. See Pub.

L. No. 111-148, §§ 1001, 1201, 124 Stat. 119, 131, 161, 885 (codified as amended at 42

U.S.C. §§ 300gg-6, 300gg-13, 300gg-18).

In this report we use the phrase “PPACA-compliant plans” to mean plans that must meet

federal requirements for individual health insurance coverage. We did not evaluate the

legal compliance of any plans for purposes of this report. PPACA-compliant plans may be

sold through federal or state PPACA exchanges that allow consumers to access possible

federal subsidies, or they may be sold by insurers directly to individuals outside of the

exchanges. Consumers may purchase PPACA-compliant plans during annual open

enrollment periods or at any time if they have a qualifying life event, such as having or

adopting a child or loss of insurance coverage.

Page 3 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

cost of premiums set by insurers and the amount of federal subsidies

available under PPACA.

6

For example, if relatively healthy individuals

choose short-term plans instead of PPACA-compliant plans, this could

result in higher premiums for PPACA-compliant plans and higher federal

subsidies.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act includes a

provision for GAO to conduct monitoring of, among other things, the effect

of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health, economy, and public and

private institutions of the United States.

7

In this report, we describe:

1. what is known about short-term plans, including the role they might

play for individuals who lost ESI during the COVID-19 pandemic;

2. how stakeholders and policy researchers view the value of short-term

plans in meeting consumer needs, including in comparison to PPACA-

compliant plans; and

3. what data about short-term plans would be useful for understanding

their role and value, according to stakeholders and policy researchers.

To address all of these objectives, we examined information from a

variety of sources, including a review of federal and state regulations, a

literature search and review of studies on short-term plans, and interviews

with selected national organizations, stakeholders and policy researchers.

We reviewed studies on short-term plans published from 2016 through

2021 to learn about (1) what has been reported on the role of short-term

plans in the insurance market generally, as well as related to people who

lost ESI during the COVID-19 pandemic from March 2020 through 2021,

and (2) views of the value of short-term plans compared to individual

health insurance coverage. (App. I provides more detail on our approach

6

Individuals purchasing coverage through the exchanges may be eligible, depending on

their incomes, to receive financial assistance to offset the costs of their coverage through

two types of subsidies. Premium tax credits reduce an eligible individual’s premium costs.

Some enrollees who qualify for premium tax credits may also be eligible to receive cost-

sharing reductions, which lower enrollees’ deductibles, coinsurance, and co-payments,

based on their income and the type of plan they select. The American Rescue Plan Act of

2021 expanded eligibility for subsidies to individuals with higher incomes and increased

subsidies for lower-income individuals for 2021 and 2022. . Pub L. No. 117-2, § 9661, 135

Stat. 4, 182 (codified as amended at 26 U.S.C. § 36B).

Premiums are set by insurers to cover the expected health care costs of the state’s

individual market and thus may vary based on whether the population is sicker or

healthier.

7

Pub. L. No. 116-136, § 19010(b), 134 Stat. 281, 580.

Page 4 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

to identify relevant literature.) We focused our research on short-term

plans sold by insurers to individuals. We did not review products sold as

group insurance.

8

Through our literature search we identified national associations that had

collected or analyzed information about short-term plans, and we

interviewed representatives from these organizations, including the

National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) and the

America’s Health Insurance Plans. We also interviewed officials from the

Congressional Budget Office, which has collected and analyzed

information about short-term plans.

In addition, we interviewed policy researchers as well as officials with

selected stakeholder organizations involved in the sale or oversight of

short term plans—including insurers that sell short-term plans and state

insurance departments.

• Through our literature search, we identified policy researchers who

had analyzed information on short-term plans from calendar years

2016 through 2021, and we interviewed seven of these individuals

selected to achieve variation across the group with respect to

organizational affiliation and policy perspective.

• We interviewed officials from six state insurance departments

selected to achieve variation in geographic region and the extent to

which the states regulate short-term plans.

9

• Finally, we interviewed four sellers of short-term plans, including three

insurers and one broker, selected to achieve variation in volume of

short-term plan sales, whether the company operated in one state or

multiple states, and to include one or more insurers that sold in our

selected states.

10

8

The private health insurance market includes individual and group coverage. The

individual market is where individuals and families buy health insurance on their own.

Health plans sold in the group market are offered through plan sponsors such as

employers.

9

The states selected for this study include Alabama, Colorado, Florida, Idaho, Michigan,

and Pennsylvania.

10

A broker is an individual who receives commissions from the sale and service of

insurance policies. These individuals work on behalf of the customer and are not restricted

to selling policies for a specific company but commissions are paid by the company with

which the sale was made.

Page 5 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

We conducted this performance audit from December 2020 to May 2022

in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Short-term plans were traditionally designed to fill temporary gaps that

may occur when an individual is transitioning from one coverage to

another; for example, when someone has left a job and is seeking other

employment. However, although sold by insurers directly to individuals,

short-term plans are exempted from the definition of individual health

insurance coverage under federal law and therefore are not required to

comply with PPACA’s requirements for individual health insurance

coverage.

11

For example, PPACA prohibits insurers that sell individual

health insurance coverage from denying coverage or charging higher

premiums because of a pre-existing condition—a condition that the

consumer had prior to applying for coverage, such as diabetes or heart

disease—and it requires such insurers to cover 10 essential health

benefits. (See fig. 1 for individual health insurance requirements under

federal regulation, including the 10 essential health benefits.) Unlike

PPACA-compliant plans, however, federal rules prohibiting the varying of

premiums based on a consumer’s health status or gender—a process

called medical underwriting—do not apply to short-term plans. Moreover,

these plans also are not subject to federal rules prohibiting denial of

coverage for pre-existing conditions, rules limiting the amount of

expenses the consumer must pay, or prohibitions on annual or lifetime

limits on how much money the insurer will pay.

12

11

See 42 U.S.C. § 300gg-91(b)(5); 45 C.F.R. § 144.103 (2021). Similarly, PPACA

requirements for group health plans and for insurance offered through an employer to a

group of its employees do not apply to short-term plans, which are sold to individuals.

12

For example, health status could include such things as physical and mental illnesses,

medical history, genetic information, and disability. While federal rules allow short-term

plans to vary premiums based on the individual consumer’s health status, gender, and

other factors, PPACA-compliant plans can only vary premiums based on four

characteristics associated with the consumer: geographic area within a state, tobacco use,

individual versus family plan, and age—plans may not charge an older adult more than

three times the premium that they charge a younger adult. See 42 U.S.C. § 300gg(a)(1).

Background

Short-Term Plans

Page 6 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

Figure 1: Selected Requirements in PPACA That Apply to Individual Health Insurance Coverage but Not to Short-Term Plans

a

For purposes of this report, we refer to short-term limited duration insurance as short-term plans.

Such plans are excluded from the federal definition of individual health insurance coverage and thus

are not subject to Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) requirements for such

Page 7 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

coverage. See 42 U.S.C. § 300gg-91(b)(5). See also Pub. L. No. 111-148, 124 Stat. 119 (2010), as

amended by the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111-152, 124

Stat. 1029 (2010).

b

Medical underwriting is a process whereby premiums may vary based on a consumer’s health status

or gender.

Although short-term plans do not have to meet these federal

requirements, some may use certain terminology and marketing

approaches that are similar to PPACA-compliant plans. For example,

short-term plans may set an annual deductible—a dollar amount for which

the consumer is responsible before the insurer makes any payments—as

well as an annual limit on the consumer’s out-of-pocket expenses for

covered services; they may establish co-payments for certain types of

services, such as $35 for each physician visit; and they may set co-

insurance rates, such as 30 percent of inpatient medical expenses.

13

They may also list the types of services that are covered. Short-term

plans may be marketed through certain brokers and on-line websites that

sell both short-term plans and PPACA-compliant plans.

In contrast to the body of federal regulations applicable to PPACA-

compliant plans, federal regulation of short-term plans is primarily

concerned with the plan’s duration of coverage and the ability of the

consumer to renew the plan. In addition, federal regulations require short-

term plans to prominently display certain information in the contract and in

any application materials including that, among other things, the coverage

is not required to comply with certain federal requirements.

14

Federal

regulations concerning short-term plan coverage duration and

renewability have changed over time, as noted below.

• Effective in June 1997, short-term plan contracts were restricted to a

maximum duration of 12 months of coverage.

15

13

Co-payments are fixed amounts that the consumer pays for a covered health service—

usually when they receive the service—and the amount can vary by the type of covered

health service. Co-insurance also requires the consumer to share in the cost of a covered

health service, but the share is calculated as a percentage of the allowed amount, which is

the maximum an insurance plan will pay for a covered service.

14

See 45 C.F.R. § 144.103 (2021).

15

62 Fed. Reg. 16,894, 16,942, 16,958 (April 8, 1997). See also 69 Fed. Reg. 78,720,

78,783 (Dec. 30, 2004).

Federal Regulation of

Short-Term Plans

Page 8 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

• Effective in January 2017, the Obama administration shortened the

maximum duration of a short-term plan contract to up to 3 months of

coverage.

16

• Effective in October 2018, the Trump administration increased the

maximum duration of a short-term plan contract to up to 12 months

and also provided that the plan could be renewed for a total of up to

36 months of coverage.

17

While states cannot allow short-term plans to have a duration longer than

federal limits, states have broad authority and discretion to regulate

health insurance, including short-term plans sold to individuals. A state

may regulate various aspects of the health insurance sold within the

state, including plan design, insurer compliance with consumer

protections, and information insurers must report to the states in which

they operate.

• Plan design. States vary in the extent to which they impose additional

restrictions on short-term plans beyond the federal requirements, for

example by:

• restricting the maximum contract duration of a single plan to 3 or 6

months, limiting the number of times a consumer can renew the

plan, or prohibiting renewal entirely;

• requiring short-term plans to offer certain benefits;

• prohibiting short-term plans from being medically underwritten,

meaning that insurers cannot vary premiums based on a

consumer’s health status;

• prohibiting the sale of short-term plans during the state’s PPACA

open enrollment period but permitting their sale outside of that

timeframe; or

• prohibiting short-term plan sales in the state.

• Consumer protections. States may have health insurance consumer

protections in place, typically known as “market conduct regulations.”

These regulations may require that consumers (1) are charged fair

and reasonable prices for short-term plans, (2) are dealing with plans

that comply with appropriate laws and regulations, and (3) are

16

81 Fed. Reg. 75,316, 75,326 (Oct. 31, 2016).

17

83 Fed. Reg. 38,212, 38,243 (Aug. 3, 2018).

State Regulation of Short-

Term Plans

Page 9 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

protected against insurers that fail to operate in ways that are legal

and fair to consumers.

• Insurer reporting. State departments of insurance may require

insurance companies licensed in the state to report a variety of

information, and this may include information about short-term plans.

States participate as members of the National Association of

Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) which collects certain data from

insurers on behalf of state members; for example, information about

different insurance products sold by the insurer and data on the

amount of premiums earned and the number of policies sold in a

state.

18

Policy researchers and representatives of national organizations we

interviewed told us that there was a lack of comprehensive data and

information on short-term plans generally, including during the COVID-19

pandemic in 2020 and 2021. This included data on enrollment in short-

term plans and the duration of policies sold—e.g., whether they were for

several months or a year and how often they were renewed. These data

would provide information about the role of short-term plans for

consumers in terms of how much consumers relied on them, and whether

they used them for temporary needs or as longer-term coverage.

• For example, one policy researcher said that most states’ insurance

departments did not collect data, and, when they did, they did not

18

NAIC is the standard-setting and regulatory support organization created and governed

by the chief insurance regulators from the 50 states, the District of Columbia and five U.S.

territories. Through the NAIC, state insurance regulators establish standards and best

practices, collect data from insurers, conduct peer review, and coordinate their regulatory

oversight. For example, NAIC collects data from insurers on behalf of states through its

Market Conduct Annual Statement.

Data Limitations

Hinder Understanding

of the Role Short-

Term Plans Played

during the COVID-19

Pandemic

Policy Researchers and

National Organizations

Cited a General Lack of

Data on Short-Term Plans

Page 10 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

collect it in comparable ways. This researcher also indicated that most

states did not review premium rates for short-term plans.

19

• Another policy researcher said that there is a lack of data sources for

short-term plans that are publicly available, and that this lack of data

limits the scope of what can be known about these plans.

• A third policy researcher said that claims about the role of short-term

plans cannot be proven or disproven without systematic data

collection.

Officials with the NAIC and the Congressional Budget Office told us that

there is a lack of accurate data and information on short-term plans,

including, but not limited to, enrollment data.

• Officials with NAIC, which collects data from insurers on behalf of

state departments of insurance, told us that data reported to them by

insurers on short-term plan enrollment and premiums in NAIC’s

annual Accident and Health Policy Experience Reports were not

complete or accurate, in part because insurers varied in how they

reported data and categorized both short-term plans and other

unregulated products in their reports. To address this issue, NAIC

issued a separate request to insurers in 2020 that sought to gather

enrollment information from insurers about short-term plans, but,

according to NAIC officials, some insurers did not respond and other

insurers did not provide complete information.

20

• Officials with the Congressional Budget Office, which studies trends in

the types of health insurance consumers have, told us that there is no

comprehensive tracking of short-term plans. In 2020, the Office

reported on the lack of data on short-term plans and cited the need for

19

Christina Lechner Goe, National Association of Insurance Commissioners, Non-ACA-

Compliant Plans and the Risk of Market Segmentation, Consideration for State Insurance

Regulators (National Association of Insurance Commissioners, March 2018).

20

Officials with NAIC told us that the association plans to implement a more

comprehensive and regular approach to data collection through a new Short-term Limited

Duration Insurance Market Conduct Annual Statement in 2022 to address state concerns

about the lack of information about short-term plans and other similar products. This

comprehensive data request was developed through a working group involving

representatives from state insurance departments and other stakeholders. It will include

data about short-term plans and association health plans—plans offered by business and

professional associations to their members—and will gather information about plan

duration, insurer denials of claims, and consumer complaints. However, as with certain

other NAIC products, most of the data will be made available only to member state

insurance departments.

Page 11 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

(1) enrollment data by state and year and (2) claims data for those

enrolled.

21

This report indicated that these data would provide a better

understanding of the effect of federal regulations for short-term plan

duration on consumer selection of these plans. In addition, according

to the report, these data could also provide information about what

types of health care spending enrollees incur and how payments to

providers compare to other individual insurance products. Officials

with the Congressional Budget Office said that they were aware of the

challenges faced by NAIC in collecting these data on behalf of state

regulators.

One policy researcher we interviewed noted that, in contrast to data

available on short-term plans, a wide range of data on PPACA-compliant

plan options is collected by the federal government and the states to

support oversight and policy-making. The Centers for Medicare &

Medicaid Services collects data through the federal and state exchanges,

including data on enrollment in different types of plans, premiums, and

demographic and income characteristics of consumers. NAIC collects

information about PPACA-compliant plans from insurers on behalf of

states through its Health Market Conduct Annual Statement, which

includes data for each state and insurer on the number of plan policies

sold and other information such as consumer cost-sharing, consumer

grievances and appeals, and insurers’ denials of claims. This information

can be used for a variety of purposes, such as monitoring consumer

preferences, tracking the cost of coverage to consumers—including both

premiums and out-of-pocket expenses—and developing policies to

improve access and affordability.

Just as comprehensive data on short-term plans is not collected

nationwide, the states we reviewed varied in the extent that they collected

data on short-term plans. None of the six states collected data on the

duration of short-term plans and the extent to which they are renewed.

22

• States that do not collect data. Two states—Pennsylvania and

Alabama—do not regularly collect data on short-term plans, including

data on the number of individuals enrolled in them. Specifically,

21

Congressional Budget Office, Letter from Director Phillip Swagel to Senator Tammy

Baldwin Re: CBO’s Estimates of Enrollment in Short-Term, Limited Duration Insurance

(Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office, Sept. 25, 2020).

22

We interviewed officials within the departments of insurance in Alabama, Colorado,

Florida, Idaho, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. At the time of our interviews with these

states, 2021 data was not available.

Data Collection and

Enrollment Trends Varied

in Selected States, Making

It Difficult to Understand

the Role of Short-Term

Plans

Page 12 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

officials from Pennsylvania said they were not able to track short-term

plan enrollment very well in part because insurers often combined

these plans together with other products, such as fixed indemnity

products, but did not break down enrollment separately for each

product.

23

Officials in Alabama reported that they did not collect data

on short-term plans on a regular basis, saying this would involve

establishing new reporting requirements, and that their staff size was

relatively small and did not have the capacity to regularly monitor new

reporting.

• States that collect data. In the three states in our review that collected

enrollment data from insurers on short-term plans—Florida, Idaho,

and Michigan—the extent of data collected varied based on what

officials told us. According to officials, Michigan only collects

information on enrollment and premiums. Florida officials said that in

addition to enrollment and premium information, they collected data

on short-term plans including claims submitted and medical loss ratios

to the extent that insurers provided that information in rate filings.

24

Officials in Idaho told us that, In addition to enrollment and premium

information, the state collects information on the number of new

policies issued, the number of policies ended, claims billed, and

rescissions (policies cancelled retroactively by insurers).

• A state with no sales of short-term plans. Colorado limits short-term

plans to up to 6 months’ duration. According to officials, short-term

plans were not sold in Colorado from 2019 through 2021.

Among the three states in our review that do collect data, enrollment

trends from 2019 to 2020—the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic—

were inconsistent. These data show that Michigan and Florida

experienced a decrease in enrollment in short-term plans, while Idaho

experienced an increase. (See table 1.) Officials in each of these states

reported that short-term plans generally accounted for a relatively small

part of their individual insurance markets. Officials in Michigan said they

did not have an explanation for why enrollment declined in 2020, and that

there were no regulatory changes that occurred during this time period

that would explain the change. Officials in Idaho explained that the

enrollment increase in 2020 may have been related to the state’s

23

Fixed indemnity products pay the consumer a fixed dollar amount per a certain time

period, regardless of what services are provided; for example, a fixed dollar payment per

day that someone is hospitalized.

24

Medical loss ratios indicate the total amount the insurer paid for claims compared to the

total amount collected in premiums.

Page 13 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

establishment in 2019 of a new form of short-term plan—called an

“enhanced” short-term plan— that provided additional protections to

consumers compared to the traditional short-term plan available in the

state.

25

Table 1: Short-Term Plan Enrollment in Selected States, 2019 and 2020

State

Short-term plan

enrollment in 2019

Short-term plan

enrollment in 2020

a

Florida

5,923

5,841

Idaho

b

5,748

6,877

Michigan

8,847

7,778

Source: GAO interviews with selected states’ departments of insurance. | GAO-22-104683

Note: Enrollment includes all lives covered by the policies sold (e.g., spouses and children, if also

covered).

a

COVID-19 was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization in March, 2020.

b

Idaho’s market includes two kinds of short-term plans—traditional and enhanced. Legislation

enacted in 2019 in Idaho established enhanced short-term plans, which must meet certain

requirements beyond traditional short-term plans; for example, meeting the state’s benchmark for

essential health benefits. According to officials, Idaho enrollment data for 2019 may include some

enrollment in enhanced short-term plans, which began to be sold in December 2019. Idaho

enrollment for 2020 included 3,298 in traditional short-term plans and 3,579 in enhanced short-term

plans.

State officials were not able to report on the role of short-term plans for

consumers—such as whether they are purchased to fill a temporary need

or as longer-term coverage—as none of the five states we examined in

which short-term plans were sold compiled data on the duration of short-

term plan coverage. Therefore, officials could not report whether

consumers purchased them as temporary coverage between having other

types of coverage, or for longer periods of time as an alternative to

individual or employer-based insurance. Officials in two of our selected

states believed that most consumers purchased them primarily as

temporary coverage, officials in two other states felt that some consumers

purchased them as temporary coverage while other consumers

25

Idaho’s market includes two kinds of short-term plans—traditional and enhanced.

Legislation enacted in Idaho in 2019 established enhanced short-term plans, which must

meet certain requirements beyond traditional short-term plans. Enhanced short-term plans

must meet the state’s benchmark for essential health benefits, must provide coverage for

longer than 6 months, and cannot vary premiums based on gender. Insurers offering

enhanced short-term plans in Idaho can consider medical history, including pre-existing

conditions, only if sold outside the PPACA open enrollment period. Insurers offering

enhanced short-term plans must set their premiums based on data for the same risk

pool—the population that buys individual health insurance in the state—as PPACA-

compliant plans.

Page 14 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

purchased them more as permanent coverage, and officials in the fifth

state did not know. Four of the six states in which we interviewed

officials—Alabama, Florida, Pennsylvania and Idaho (for enhanced short-

term plans)—allowed initial short-term plan contracts for up to 1 year with

renewals that could allow for a total duration of coverage of up to 36

months. (See table 2 for requirements regarding limits on the length of

coverage and renewability of short-term plans in the six states we

examined.)

Table 2: Regulation of Contract Period and Renewal for Short-Term Plans Sold in Selected States, 2020-2021

State Plan contract period

Contract renewal and total coverage duration

allowed

Alabama

Less than 12 months

May be renewed or extended for a total duration not

to exceed 36 months

Colorado

a

Up to 6 months

Not renewable

Florida

Less than 12 months

May be renewed or extended for a total duration not

to exceed 36 months

Idaho: traditional short-term plans

b

Up to 6 months

Not renewable

Idaho: Enhanced short-term plans

b

Longer than 6 months, up to 12

months

May be renewed or extended for a total duration not

to exceed 36 months

Michigan

Up to 185 days

c

Consumers are limited to 185 days of coverage in a

365 day period

Pennsylvania

Less than 12 months

May be renewed or extended for a total duration not

to exceed 36 months

Source: GAO interviews with state departments of insurance and review of state regulations. | GAO-22-104683

a

No insurers offered short-term plans in 2020 or 2021 in Colorado.

b

Idaho’s market included two kinds of short-term plans—traditional and enhanced. Legislation

enacted in Idaho in 2019 established enhanced short-term plans, which must meet certain

requirements beyond traditional short-term plans; for example, meeting the state’s benchmark for

essential health benefits.

c

Exceptions apply.

Page 15 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

Concerns about Association Health Plans and Health Care Sharing Ministries

In addition to short-term plans, certain other products, including those commonly

referred to as association health plans, are not subject to certain health insurance

coverage requirements established under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care

Act (PPACA). For example, under a 2018 Department of Labor regulation, association

health plans are not subject to the PPACA requirement to cover the 10 essential health

benefits. Historically, these sales were made by associations that had a primary

purpose other than selling insurance, but several individuals we spoke to expressed

concerns about short-term plans sold by associations, including in some cases by

associations created primarily for the purpose of selling association health plans.

Officials in several of the states we studied said they were concerned about the growth

of these plans.

• Florida officials said that enrollment in these plans had grown significantly since

2017, as fewer individuals were able to afford plans subject to PPACA

requirements. They said that a filing to the state by one large out-of-state insurer of

short-term plans indicated that it may have from 15,000 to 18,000 policies that

were similar to short-term plans sold through associations.

• Pennsylvania officials said that, among associations selling health coverage in the

state, one claimed to have 40,000 lives covered in Pennsylvania, while others had

as few as 2,500.

In addition, products sold by certain faith-based organizations, commonly referred to as

health care sharing ministries, may not comply with federal requirements of individual

health insurance coverage. Officials in Colorado and Idaho noted their concerns about

the recent growth of consumer purchases of coverage through health care sharing

ministries that share resources for medical needs among members who make a

periodic payment.

• Idaho officials estimated that there were 25,000 consumers in health care sharing

ministries in 2019 and 2020, compared to 102,000 and 82,000 consumers,

respectively, who purchased individual coverage on the PPACA exchanges in

those years.

• Colorado officials said that there was an increase in enrollment in health care

sharing ministries after insurers stopped selling short-term plans in the state, but

officials said they did not have specific data on their enrollment.

Source: GAO interviews with selected states’ departments of insurance. | GAO-22-104683

Our interviews with stakeholders and policy researchers, and our

literature search, found widely varying views of the overall value of short-

term plans to consumers, including for those who lost ESI during the

COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, we found disagreement about how

short-term plans compared to PPACA-compliant plans with respect to

cost, benefit coverage, and consumer information. Given that there are no

comprehensive data available on short-term plans, stakeholders based

their views on their observations of the insurance market and some

limited data; policy researchers based theirs on information collected in

specific research studies.

Views Varied Widely

about the Value of

Short-Term Plans to

Consumers and as

Compared to

Individual Health

Insurance Coverage

Page 16 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

Some interviewees said that short-term plans provide an important option

for consumers, in some cases to meet short-term needs and in other

cases for longer-term coverage.

• Some interviewees identified examples of consumers who they said

could benefit from short-term plans, including those who lost ESI

during the pandemic and were in need of coverage until they became

re-employed, consumers whose employment varies by season, and

consumers whose income is too high to be eligible for Medicaid but

too low to afford a PPACA-compliant plan.

26

Officials with the

Alabama Department of Insurance said that, in times of economic

downturns, it is critical to offer individuals as many options as possible

to allow them to guard against health-related risk. Officials with one

insurer said that short-term plans can help consumers who need

coverage until the next open enrollment period. One broker we spoke

to said that he had previously purchased a short-term plan to cover

himself until the PPACA open enrollment period.

• Some interviewees noted that short-term plans can be beneficial as

longer-term coverage, since current federal regulations allow short-

term plans to last for up to 1 year with the possibility of renewing for

up to 3 years. One insurer we spoke with said that their company

works with many consumers who seek to buy short-term plans and

renew them regularly to maintain coverage over time. Officials with

the Alabama Department of Insurance said that short-term plans

provide additional pricing levels for consumers who do not have

access to PPACA subsidies. Officials in Idaho said that PPACA-

compliant plans had become unaffordable for many residents, and

that short-term plans provided an option to them. One policy

researcher reported that his family was enrolled in a short-term plan,

noting that he is self-employed and does not have an offer of health

coverage through an employer.

In contrast, other interviewees said that short-term plans do not provide

good value to consumers. They said that short-term plans can be

financially risky for consumers and should be prohibited by the federal

government or more strongly regulated by states or the federal

government; for example, by limiting a plan’s total duration to less than 1

year with no renewability.

26

Medicaid is a federal-state program that finances health care for low-income and

medically needy individuals. Individuals who lose health coverage due to job loss may be

eligible to enroll in individual health insurance coverage and may be eligible for subsidies

for exchange coverage.

Some Stakeholders and

Policy Researchers Said

Short-Term Plans Serve

an Important Purpose,

While Others Expressed

Strong Reservations about

Their Value

Page 17 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

• Several policy researchers said that, ideally, short-term plans should

be prohibited, but, if they are not, they should be limited to 3 months

or less in duration, they should not be renewable, and they should be

required to comply with at least some PPACA consumer protections.

One policy researcher told us that, while short-term plans may serve a

legitimate purpose for some consumers, they should nevertheless not

be renewable and only allowed for short-term needs.

• The commissioner of Pennsylvania’s Insurance Department testified

to Congress regarding the problems with short-term plans their state

experienced, including numerous consumer complaints related to

denials of claims by insurers.

27

The commissioner recommended

limiting the duration of these plans to less than 1 year and not

allowing them to be renewed. The Department has issued periodic

notices to consumers alerting them about possible issues with short-

term plans.

• Officials with Colorado’s Department of Insurance said that, when

short-term plans were sold in the state, there were consumer

complaints about them, and consumers did not understand the plans’

pre-existing condition exclusions.

Stakeholders, policy researchers, and research studies also disagreed

about the extent to which short-term plans provide value compared to

PPACA-compliant plans, specifically with respect to cost, benefit

coverage, and consumer information. In addition, some state officials,

policy researchers and research studies identified strong concerns with

the marketing of short-term plans.

Most of the individuals we spoke to, and some research studies reported,

that short-term plans can have lower premiums than PPACA-compliant

plans. However, while some individuals said this indicated the positive

value of short-term plans to consumers, others said that it does not reflect

the full cost to the consumer, and that, in order to compare short-term

plans to other options such as PPACA-compliant plans, additional

information needs to be considered.

27

Strengthening Our Health Care System: Legislation to Reverse ACA Sabotage and

Ensure Pre-Existing Conditions Protections: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Health

of the Committee on Energy and Commerce, 116

th

Cong. (2019) (statement of Jessica K.

Altman, Commissioner, Pennsylvania Insurance Department).

Views Differed on the

Value of Short-Term Plans

to Consumers with

Respect to Cost, Benefit

Coverage, and

Information, Compared to

PPACA-Compliant Plans

Cost of Coverage

Page 18 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

Individuals we spoke to and some studies indicate that short-term plan

premiums can be lower than premiums for PPACA-compliant plans. An

insurer we spoke with described an example of a 6-month short-term plan

for a 19-year-old individual with no pre-existing conditions that had a

monthly premium of $39. By comparison, the Centers for Medicare &

Medicaid Services reported that monthly premiums for a PPACA-

compliant plan for a 27-year old (the only individual premium rate

described) in 2020 ranged from $278 to $426, not including any subsidies

for which certain individuals might be eligible.

28

One study illustrated the

difference in premium amount by comparing the premiums for a popular

short-term plan and a popular low-cost PPACA-compliant plan in the

individual health insurance market in Atlanta, Georgia, in 2019, for a 27-

year old female nonsmoker. The monthly premium for the short-term plan

was $77 per month and $293 for the PPACA-compliant plan, not including

any subsidy.

29

Another study compared premiums for the lowest cost

bronze tier exchange plan to the lowest short-term plan premium posted

online in 10 urban areas, and found that the lowest cost short-term plan

premiums could be as much as 91 percent cheaper.

30

A third study

28

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Center for Consumer Information and

Insurance Oversight, Plan Year 2021 Qualified Health Plan Choice and Premiums in

HealthCare.gov States, (Nov. 23, 2020). Premium data reflects the average lowest cost

plan across different tiers of plans, with tiers defined by their actuarial value, or the

percentage of total average costs for covered benefits that a plan will cover. These data

do not include adjustments for premium tax credits that some low income individuals are

eligible for through the PPACA exchanges. Eighty-six percent of exchange enrollees

received premium tax credits on average each month in 2020. Center for Medicare &

Medicaid Services, Effectuated Enrollment: Early 2021 Snapshot and Full Year 2020

Average. (June 5, 2021).

29

Dane Hansen and Gabriela Dieguez, The Impact of Short-Term Limited-Duration Policy

Expansion on Patients and the ACA Individual Market (Seattle, WA; Milliman Research

Report, February 2020). The researchers chose a “bronze” tier plan for comparison to the

short-term plan, because it has among the lowest cost premiums among PPACA-

compliant plans. In general, as actuarial value—the percentage of total average costs for

covered benefits that a plan will cover—increases, consumer cost-sharing decreases. The

actuarial values of the metal tiers are: bronze (60 percent), silver (70 percent), gold (80

percent), and platinum (90 percent).

30

Monthly premiums for the PPACA plans did not reflect discounts for premium tax credits.

Monthly premiums for short-term plans reflected prices posted online, were not

guaranteed, and could be adjusted after medical underwriting. Karen Pollitz, Michelle

Long, Ashley Semanskee, and Rabah Kamal, Understanding Short-Term Limited Duration

Health Insurance (San Francisco, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation, April 2018).

Page 19 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

estimated that short-term plans premiums could be as much as 54

percent lower than PPACA-compliant exchange plans.

31

However, although short-term plan premiums may sometimes be lower

than those for PPACA-compliant plans, some interviewees and research

studies reported that, to compare the value of the two types of coverage,

additional information needs to be considered, and that it is misleading to

suggest that short-term plan coverage is similar to comprehensive

coverage under a PPACA-compliant plan.

• For example, the cost of PPACA coverage is reduced for individuals

who—based on their income—qualify for partial or complete premium

subsidies or reduced cost-sharing. According to one study, over 20

million individuals were estimated to be eligible for PPACA subsidies

in 2020.

32

According to the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services,

the average monthly premium for those receiving advance premium

tax credits through the PPACA exchanges in 2020 was $89.

33

• Most of the individuals we spoke to reported that some short-term

plans do not cover services for pre-existing health conditions, which

PPACA-compliant plans must cover. Some of those we spoke to told

us that some people would not be eligible to purchase a low cost

short-term plan due to pre-existing conditions or would be charged

higher premiums based on their health history. One research study

estimated that, in 2018, 27 percent of non-elderly adults in the United

States—about 54 million people—had a pre-existing condition that

would be declined for coverage under medically underwritten health

insurance.

34

31

Larry Levitt, Rachel Fehr, Gary Claxton, Cynthia Cox, and Karen Pollitz, Why do Short-

Term Health Insurance Plans Have Lower Premiums than Plans that Comply with the

ACA? (San Francisco, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation, October 2018).

32

Kaiser Family Foundation, Marketplace Enrollees Receiving Financial Assistance as a

Share of the Subsidy-Eligible Population (San Francisco, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation,

2022).

33

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Health Insurance Marketplaces 2021 Open

Enrollment Report, retrieved on 3/4/2022 from: https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-

data-systems/marketplace-products/2021-marketplace-open-enrollment-period-public-

use-files.

34

Gary Claxton, Cynthia Cox, Larry Levitt, and Karen Pollitz, Pre-existing Condition

Prevalence for Individuals and Families (San Francisco, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation,

October 2019), accessed March 4, 2022, https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/pre-

existing-condition-prevalence-for-individuals-and-families/#.

Page 20 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

• As another example, short-term plans can establish a higher limit for

what consumers must annually cover out-of-pocket, beyond premium

payments, than PPACA-compliant plans are allowed to do. These out-

of-pocket costs include deductibles, co-payments, and co-insurance.

One research study estimated the costs that consumers would pay for

premiums and out-of-pocket expenses if they were newly diagnosed

with one of several conditions—for example, diabetes, a heart attack,

or lung cancer—and found that the total cost to those covered by

short-term plans and diagnosed with one of these conditions was

significantly greater than their costs would have been under a

PPACA-compliant plan. The study estimated, for example, that a

consumer who had a heart attack would face a cost of $32,100 under

the short-term plan in the 6 months following diagnosis, compared to

$7,900 under a PPACA-compliant plan in the same time period.

35

Policy researchers and the research literature disagreed in their

characterization of the extent to which short term plans offer a

comprehensive array of health benefits compared to PPACA-compliant

plans.

One policy researcher we spoke to said that, in assessing short-term

plans’ coverage of benefits, it is most important that consumers have at

least one short-term plan option in their area that covers a broad array of

benefits. They discussed their research that found that short-term plans

covering all of PPACA’s essential health benefits—except maternity

benefits—are widely available.

36

This study looked at the number of short-

term plans that two online websites listed in the major urban area in each

state, and whether these plans included coverage for certain benefits:

prescription drugs, mental health, substance abuse and maternity care. It

found that in most states there were at least some short-term plans that

provided coverage for three of these services, specifically, prescription

drugs, mental health and substance abuse.

35

Dane Hansen and Gabriela Dieguez, The Impact of Short-Term Limited-Duration Policy

Expansion.

36

Chris Pope, Renewable Term Health Insurance: Better Coverage than Obamacare (New

York, NY: Manhattan Institute, May 2019).

Pollitz, Long, Semanskee, and Kamal, Understanding Short-Term Limited Duration

Insurance.

Benefits

Page 21 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

In contrast, other research studies and stakeholder interviews

emphasized that short-term plans often do not cover these benefits. For

example, one study looked at the same state-level data as in the study

noted above but calculated the percent, rather than the number, of short-

term plans that did not cover these benefits. The study concluded that 71

percent of short-term plans did not cover prescription drugs, 62 percent

did not cover substance abuse treatment, and 43 percent did not cover

mental health services.

37

The study further noted that, even when a plan

did cover one of these services, there were almost always limitations or

exclusions in the short-term plan that would not be permitted under

PPACA-compliant plans, such as a limit on the payment amount for

mental health services. Therefore, according to the study, it would be

misleading to suggest the short-term plan coverage is similar to

comprehensive coverage under a PPACA-compliant plan. One insurer we

spoke with said that their short-term plans cover fewer benefits than

PPACA-compliant plans. They said that their plans cover some essential

health benefits but not others, such as preventive care, so a consumer’s

visit to a physician would only be covered if the consumer was sick. In

addition, rather than providing prescription drug coverage, the short-term

plan provided a drug discount card.

38

Stakeholders, policy researchers, and research studies also disagreed

about the degree to which consumers seeking coverage may face

challenges in obtaining and understanding information about short-term

plans, particularly compared to PPACA-compliant plans.

Some of the interviewees we spoke to reported that insurers provided

consumers with information about short-term plan policies that consumers

needed.

37

Pollitz, Long, Semanskee, and Kamal, Understanding Short-Term Limited Duration

Insurance. Another study looked at 96 short-term plans offered via an online source in the

Atlanta, Georgia, market in 2019 and found that 67 percent did not include prescription

drug benefits, and 58 percent did not include mental health and substance abuse disorder

benefits. See Hansen and Dieguez, The Impact of Short-Term Limited-Duration Policy

Expansion. A third study reviewed 12 short-term plans being sold in three states, and

reported that 11 excluded nearly all coverage of prescription drugs, with some providing

limited coverage of inpatient prescriptions. Emily Curran, Kevin Lucia, JoAnn Volk, and

Dania Palanker. In the Age of COVID-19, Short-Term Plans Fall Short for Consumers

(New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund, May 12, 2020).

38

Drug discount cards or coupons provide the consumer with a discount when purchasing

a prescription drug from a pharmacy; they are not considered insurance.

Consumer Information

Page 22 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

• The broker we spoke to, whose company markets short-term plans

directly to consumers online, said that consumers are given clear

disclosures that these plans are not PPACA-compliant, and that pre-

existing conditions are not covered.

• Similarly, officials with one insurer said they did not believe there were

risks to consumers buying its short-term plans, because the terms of

these plans were clearly laid out in their promotional materials.

• Officials with another insurer noted that they assumed that consumers

were satisfied with their short-term plans because they had fewer

consumer complaints for their short-term plans than for their Medicaid

and Medicare products.

• Officials from Alabama said their guidance requires insurers to clearly

state the terms of the short-term plan policy to avoid any

misinterpretations, their department has issued news briefings to the

general public about short-term plans, and they have a chart on their

website that provides a full synopsis of what short-term plans are

relative to PPACA-compliant plans.

In contrast, some policy researchers and stakeholders reported that

consumers may have less information about short-term plans than for

PPACA-compliant plans or may not understand certain aspects of short-

term plans. One researcher said that, because short-term plans are not

subject to PPACA requirements, they are difficult to compare to each

other, and that, while some insurers provide straightforward policy

descriptions, others’ policies are confusing, ambiguous, and include lots

of exceptions. Insurers offering short-term plans are not required to

provide consumers with a summary of benefits and coverage that

complies with PPACA guidelines for format and content, although they

may choose to do so. (See text box.) In one secret shopper study of sales

representatives selling non-PPACA-compliant products, including short-

term plans, most of the sales representatives refused to provide plan

documentation in advance to the consumer—even when asked for it

directly—and would only provide it after the consumer made an initial

payment.

39

Officials with the Michigan Department of Insurance said that

consumers may not understand that short-term plans provide limited

coverage, or that there are differences compared to PPACA-compliant

plans. Officials with the Pennsylvania Department of Insurance reported

many cases of consumers purchasing short-term plans without a full

39

Center on Health Insurance Reforms, Dania Palanker and JoAnn Volk, Misleading

Marketing of Non-ACA Health Plans Continued During COVID-19 Special Enrollment

Period (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Health Policy Institute, October 2021).

Page 23 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

understanding of the product’s limitations. In some of these cases,

officials said, consumers faced significant costs to pay for care that the

short-term plan would not pay for. Legislation was proposed in the

Pennsylvania House of Representatives in February 2021 to establish

requirements for insurers to disclose complete and accurate information

to consumers, among other things, but it had not been passed as of

February 2022.

Source: GAO analysis of federal regulations and requirements. | GAO 22 104683

Several individuals we interviewed told us that there are certain concepts

important to understanding short-term plans that can be challenging for

consumers to understand, such as “post-claims underwriting” and “pre-

existing condition.”

40

One researcher said that they had never seen post-

claims underwriting explained to consumers in short-term plan marketing

materials. Others said that the definition of pre-existing condition may not

40

Post-claims underwriting is a process whereby an insurer conducts an in-depth review of

a consumers’ medical records after the consumer has received the service, and after the

insurer has received an insurance claim, in order to ensure that the claim is for a benefit

that is covered and not, for example, for a pre-existing condition. Post-claims underwriting

may be used to deny claims to enrollees of short-term plans or rescind a short-term plan

policy, except where prohibited by state law.

Information Available to Consumers about PPACA-Compliant Plans

Plans compliant with the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) must

meet certain federal requirements related to providing consumers with information

about plan characteristics and provisions. Specifically, issuers of PPACA-compliant

plans must provide a summary of benefits and coverage to applicants and enrollees.

This summary must provide a list of benefits and deductibles, co-payments, and co-

insurance rates, among other things. All plans must present this summary in the same

format to make it easy for consumers to compare plans. They must also provide

examples of what the plan will cover in common medical situations and must tell

consumers what is not covered under the specific plan.

In addition to a summary of benefits and coverage for individual plans, PPACA health

insurance exchange websites may offer side-by-side comparisons of multiple plans and

their key features such as premiums and deductibles. PPACA-compliant plans sold on

these federal and state websites may be grouped into categories based on plans’

relative “actuarial value,” which is the percentage of total average costs for covered

benefits that a plan will cover, which can help consumers assess the relative similarities

and differences among different plan options, and what the consumer’s expected costs

will be. For example, if a plan has an actuarial value of 70 percent, consumers, on

average, would be responsible for 30 percent of the costs of all covered benefits.

However, an individual consumer could be responsible for a higher or lower percentage

of the total costs of covered services for the year, depending on actual health care

needs and the terms of the insurance policy. They would also be protected by a

maximum out-of-pocket threshold for the year.

Page 24 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

be obvious or clear to many consumers; for example, a consumer may

not know that a reference to “chest cold” in their medical record may

suggest or be considered a pre-existing condition, and that therefore any

future treatment for a chest cold or other respiratory illness might not be

covered. Officials with an insurer agreed that it can be challenging to

educate consumers about the exclusion of pre-existing conditions. A joint

report by 30 national organizations that represent patients with serious

health conditions profiled examples of consumers who purchased short-

term plans and subsequently were faced with high costs because the

insurer found that their illness was a pre-existing condition.

41

A report by

the House Energy and Commerce Committee Democratic Staff profiled

cases of consumers who had purchased short-term plans and whose

claims were subsequently denied because the insurer found that the

medical services were for a pre-existing condition.

42

Finally, short-term plans are not subject to PPACA’s requirements for

maximum lifetime out-of-pocket costs limits for consumers, although

states could set such a maximum. Such a limit provides protection to

consumers who have, for example, long-term illnesses that result in

significant medical costs. According to one researcher, when looking at

short-term plans a consumer may only notice the total maximum dollar

amount that the insurer will cover under the plan and think that it will be

enough to meet their needs. However, they may not be aware of detailed

provisions within different parts of the policy that limit how much the

insurer would pay to cover a specific service, or that exclude coverage for

the service, for example outpatient chemotherapy, which can be

expensive.

Interviews with some state officials and policy researchers, and our

review of research studies, indicated strong concerns about the marketing

of short-term plans, including concerns about misleading and fraudulent

sales practices as well as about the financial incentives for insurers and

brokers selling short-term plans versus PPACA-compliant plans.

41

Partnership to Protect Coverage, Under-Covered: How “Insurance-Like Products Are

Leaving Patients Exposed. 2021 (Accessed March 21, 2022,

https://nami.org/About-NAMI/NAMI-News/2021/New-Report-Under-Covered-How-Insuran

ce-Like-Products-are-Leaving-Patients-Exposed).

42

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce, Democratic Staff,

Shortchanged: How the Trump Administration’s Expansion of Junk Short-Term Health

Insurance Plans is Putting Americans at Risk (June 2020).

Marketing

Page 25 GAO-22-104683 Private Health Insurance

• Officials with three of the state insurance departments we spoke with

expressed such concerns. For example, officials in Pennsylvania said

that some insurers and brokers told consumers that short-term plans

would cover the same benefits as a PPACA-compliant plan, when in

fact they did not. Officials in Florida said that the biggest risk of short-

term plans relates to brokers misrepresenting what the plans cover

during the sales process.

• Several policy researchers reported that their work had identified

marketing practices that directed consumers to short-term plans when

they might have been eligible for a subsidized PPACA-compliant plan.

For example, one study that looked at the results of web-based

searches for health insurance in eight states found that, regardless of

search terms used, companies selling short-term plans generally

dominated the results returned.

43

Another study, which surveyed

consumers about their experience in shopping for coverage, found

that 22 percent of consumers who were helped by a broker or

commercial health plan representative said they were offered an

alternative to a PPACA-compliant plan, such as short-term plans with

lower premiums but that excluded pre-existing conditions and other

benefits required of PPACA-compliant plans.

44

Another study,

conducted following the federal increase of PPACA premium

subsidies, found that most sales representatives contacted were more

likely to refer consumers to products that were not PPACA-compliant,

such as short-term plans, and most representatives did not suggest

PPACA-compliant coverage.

45

43

Sabrina Corlette, Kevin Lucia, Dania Palanker and Olivia Hoppe, The Marketing of

Short-Term Plans: An Assessment of Industry Practices and State Regulatory Responses

(Washington, DC: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Urban Institute, January 2019).

44

Karen Pollitz, Jennifer Tolbert, Liz Hamel, and Audrey Kearney, Consumer Assistance in

Health Insurance: Evidence of Impact and Unmet Need (San Francisco, CA: Kaiser

Family Foundation, Aug. 7, 2020).

45

Dania Palanker and JoAnn Volk, Misleading Marketing of Non-ACA Health Plans

Continued During COVID-19 Special Enrollment Period (Washington, DC: Georgetown

University Health Policy Institute, October 2021).

Initially, tax credits were available to consumers with income below 400 percent of the

federal poverty level if the applicable premiums were greater than a specified percent of

their income. The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, signed into law in March 2021,