INCLUSIVE

CLIMATE ACTION

PARTICIPATORY

APPROACHES IN

SOLID WASTE

MANAGEMENT FOR

BULK WASTE

GENERATORS IN

BENGALURU

A BASELINE ASSESSMENT REPORT

This assessment report received generous support in funding from Porticus as

part of the C40 Cities Global Green New Deal Pilot Implementation Initiative.

The principal authors of the report are:

Authors

Saahas NGO & Saahas Zero Waste

Divya Tiwari

Annie Philip

Shanti Tummala

Angel Vinod

Priyanka Kesavan

C40 Cities

Akshatha Venkatesha

Contributors from C40

We are grateful to C40 colleagues for their valuable inputs and feedback:

Shruti Narayan, Jazmin Burgess, Josephine Agbeko, Benjamin John,

Ricardo Cepeda-Màrquez, Connor Muesen

Design and typesetting: Mitchelle Collette Dsouza

Sincere gratitude is extended to all the participants

(as detailed in Annexure 1) for their valuable insights during the stakeholder

engagement process, which have greatly enriched this report.

Acknowledgements

List of figures

List of abbreviations

Executive summary

Introduction

Waste and climate change

Approach and methodology

4.1 Baseline assessment and stakeholder engagement

4.2 Mapping of BWGs

Applicable legal and policy framework for the BWG ecosystem

5.1. Overview

5.2. Who are BWGs

5.3. Duties of BWGs

5.4. BBMP SWM bye-laws: Welfare, occupational safety and training

Overview of Bommanahalli zone

BWGs in Bommanahalli and their climate impact

7.1. Mapping of BWGs

7.2. GHG emissions by BWGs

Identification of stakeholders, their vulnerabilities and spheres of influence

8.1. Stakeholder identification

8.2. Vulnerability and power analysis

Stakeholder engagement using participatory approaches

9.1. Overview

9.2. Objectives of stakeholder engagement

9.3. Participatory approaches adopted in stakeholder consultations

Key findings from stakeholder engagement

10.1. Policy and enforcement

10.2. Criticality of source segregation

10.3. Capacity building opportunities

10.4. Risks and vulnerabilities associated with social inclusion

10.5. Necessity of recognition and job security

10.6. Financial viability of in-situ biodegradable waste management

10.7. Ancillary support

Recommendations

11.1. Policy

11.2. Capacity building of BBMP zonal ocials

11.3. Monitoring

11.4. Inclusion

11.5. Capacity building of BWGs and other support

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

Table of contents

References

Annexure 1: Details of stakeholder engagement

Annexure 2: List of wards in Bommanahalli zone

Annexure 3: Roles and responsibilities of stakeholders in BWG ecosystem

5

6

7

9

12

15

15

16

17

17

18

19

19

21

22

22

25

27

27

30

34

34

34

35

37

38

39

40

43

45

45

46

48

49

49

50

51

52

53

55

57

58

5

Figure 1: System-based GHG inventory US (Domestic) emissions, 2006 12

Figure 2: Organization structure 21

Figure 3: Bommanahalli zonal map with ward spatial distribution 21

Figure 4: BWGs mapped in Hongasandra 23

Figure 5: BWGs mapped in HSR Layout 23

Figure 6: Ward-wise split of BWGs in 5 wards 24

Figure 7: Category-wise split of BWGs in 5 wards 24

Figure 8: Daily GHG emissions reduction due to processing of waste at city and zonal level 26

Figure 9: Estimated GHG emissions from transportation of waste 26

Figure 10: Categories of stakeholders in BWG ecosystem 27

Figure 11: Waste flow from BWGs 29

List of figures

6

AEE Assistant Executive Engineer

BBMP Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike

BWG Bulk Waste Generator

CAP Climate Action Plan

CBG Compressed Biogas

CPCB Central Pollution Control Board

GGND C40's Global Green New Deal

GHG Greenhouse Gas

HCF HSR Citizen’s Forum

HDPE High Density Polypropylene

ICA C40's Inclusive Climate Action

IEC Information, Education & Communication

IPCC International Panel on Climate Change

JC Joint Commissioner

JHI Junior Health Inspector

NGO Non-governmental Organisation

PET Polyethylene Terephthalate

RWA Resident Welfare Association

SE Superintendent Engineer

SWM Solid Waste Management

SWMRT Solid Waste Management Round Table

TPD Tons Per Day

List of abbreviations

7

Bengaluru, the capital of Karnataka, is

one of the fastest urbanising cities in

India and this rapid urbanisation has

resulted in various challenges in solid

waste management - lack of

infrastructure, limited capacities and

monitoring, inequitable working

conditions for the waste workers who

handle the city's waste. These challenges

also provide an unequivocal opportunity

to strengthen solid waste management

practices in a way that delivers both

social and climate benefits for the city

residents. Bengaluru joined the C40

Cities network in 2017 and the Bruhat

Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) -

which is the administrative authority for

the city - initiated the Climate Action and

Resilience Plan for Bengaluru (BCAP) in

2021 and is now in the advanced stages

of preparing its BCAP for adapting to

climate change impacts including

addressing concerns relating to waste

management. Bengaluru is the first city

in South West Asia to participate in

C40’s Global Green New Deal (GGND)

pilot implementation initiative led by

C40’s Inclusive Climate Action (ICA)

Programme.

1. Executive summary

For Bengaluru, under the GGND pilot, the C40

team in consultation with BBMP has identified

‘bulk waste management’ as an area with

potentially high impact with regard to driving

the inclusive climate action agenda. This is

primarily because of two reasons: firstly, bulk

waste management through its core idea of

on-site waste management contributes

significantly to climate action due to

decentralised management of biodegradable

waste and reduced transportation of waste to

processing facilities in the outskirts of the city.

Secondly, waste management in cities employs

a large workforce with many

vulnerable groups such

as waste collection

and processing sta and these groups are

more invisible when servicing bulk waste

generators (BWGs) compared to non-bulk

waste generators. BWGs are not serviced by

the BBMP but by private service providers,

hence they are more invisible and addressing

their inclusion becomes more challenging.

While BWGs contribute 35-40% of the city’s

waste and BBMP regulations mandate BWGs

to take responsibility for managing their

biodegradable waste, there are several gaps in

the capacity of the key stakeholders,

processes, implementation, enforcement and

monitoring of these regulations (CSE,2023).

8

This report presents an assessment of the gaps

and needs in bulk waste management with

respect to the policy, processes, capacities and

also the conditions and needs of the vulnerable

groups engaged in this system. It discusses

how collaborative and participatory eorts to

execute decentralised waste management

systems can accelerate prior work done in the

city with regard to BWGs, in an integrated and

inclusive manner while also addressing the

climate action needs.

Methodologically, the study adopted an

in-depth approach of analysing one zone in the

city, which involved identifying all types of

stakeholders in the BWG ecosystem of

Bommanahalli zone and thereafter, engaging

with them using dierent participatory tools. A

zonal focus helped reduce the impact of many

other extraneous factors such as the role of the

zonal administration, private service provider

services, overall hygiene and sanitation

conditions etc. A diverse set of stakeholders

including BBMP ocials such as Joint

Commissioner (JC), Superintendent Engineer

(SE), Assistant Executive Engineer (AEE) and

Junior Health Inspector (JHI), civil society

groups, service providers, waste collection

sta, contractors and waste processors were

identified.

During stakeholder engagement, participatory

tools such as semi-structured interviews, focus

group discussions and workshops

were especially eective for working with

vulnerable groups, understanding a situation

from the participants’ point of view and

developing action-oriented interventions

that are beneficial and acceptable to all

stakeholders. The participation of decision

makers, implementers (including those who

are vulnerable) and advocacy groups in the

dierent consultations allowed for

identifying challenges and opportunities for

BWG waste management practices to be

strengthened in a way that is inclusive and

equitable.

While the city maintains a ward wise database

of the BWGs, it is severely underestimated, and

no state or national inventory can provide the

number of total BWGs, the quantum of waste

generated by them and the amount of waste

processed onsite. Therefore, each city must

prepare an inventory of the existing BWGs

after scientifically mapping, identifying and

quantifying the waste generated and treated

(Sengupta, 2023). Hence, a detailed mapping

exercise of BWGs was done in 5 wards of

Bommanahalli Zone. This also helped in

assessing the climate action potential of the

interventions in the BWG ecosystem due to

onsite processing of biodegradable waste.

The findings from the study show that there is

a need for various stakeholders to work in

confluence to enforce existing policy

regulations while also bridging gaps in terms

of stakeholder capacities, implementation and

monitoring systems for BWGs and other

stakeholders in the ecosystem. While

significant work has been done in the

Bommanahalli zone in the past with respect to

source segregation, there is a need to build

capacities of the bulk waste generator

ecosystem in ways that expands the number of

BWGs who carry out onsite management of

biodegradable waste and are compliant to

regulations. This will reduce the load on the

city’s waste collection and processing systems

while also mitigating GHG emissions.

The findings also show that there is limited

support provided to ensure occupational

safety, fair wages, job security, ergonomic

safety equipment and access to welfare

measures across dierent groups of workers,

the most vulnerable being migrant workers.

Participants in the stakeholder consultations

identified challenges in implementing

decentralised waste management and barriers

to ensuring optimal enforcement and

monitoring systems for BWGs, while also

providing possible solutions and opportunities

for improving policy, implementation and

capacity building as part of the GGND pilot

implementation in Bengaluru.

9

2. Introduction

Rapid population growth and urbanisation

have resulted in low-income countries

struggling to cater to rising solid waste

management needs, with over 90% of waste

often disposed of in unregulated dumps or

openly burned (World Bank, 2022). In cities

across India, poorly managed waste serves as

a breeding ground for disease vectors,

contributes to global climate change through

methane generation and creates inequitable

and unsafe working conditions for sanitation

workers. It is estimated that Bengaluru

generates nearly 5,000 tons of solid waste

per day (KSPCB, 2021).

While a portion of the city’s waste is dealt

with by sanitation workers (pourakarmikas in

Kannada) on the city’s payroll, contractual

waste collection sta and informal workers

collect, sort and manage a large portion of

the waste that is generated daily, including

waste from bulk waste generators. These

workers are stratified by degrees of

vulnerability - those employed by the city

are supported by certain

regulatory

mechanisms and unions whereas informal

migrant workers employed by labour

contractors are at the lowest rung of the

pyramid, with low wages, no regulatory

support and a lack of job security (Raghavan,

2023). These working and economic

conditions result in increased vulnerabilities to

climate change; workers do not have access

to proper housing or health care that will

allow them to cope with extreme heat, floods

and other adverse eects of climate change

(Michael et al., 2017). Ironically, they play a

pivotal role in reducing emissions and

improving the city’s response to climate

change by diverting large quantums of BWG

waste from landfills.

As part of its extensive work to improve solid

waste management in Bengaluru, the BBMP

issued a notification in 2012 that provided a

clear definition of Bulk Waste Generator

(BWG)

1

while mandating them to take

responsibility for managing their

waste

Globally, annual

waste generation

is expected to

increase by 73%

from 2020 levels

to 3.88 billion

tonnes in 2050.

10

on-site or collaborate with approved service

providers for o-site waste management. This

initiative stood as a pioneering example, being

the first of its kind in the Indian waste sector.

Since this notification, Bengaluru has had an

enabling ecosystem with many citizen groups

and organisations providing critical support to

bulk waste generators in implementing source

segregation, providing community

composting solutions and other technical

expertise for decentralised waste

management. However, over a decade later,

there has been little progress in the eective

implementation of this notification even

though it has also been adopted in the

national regulatory framework of the SWM

Rules, 2016.

In the above context, C40 Cities partnered

with Saahas NGO to undertake a pilot study in

solid waste management on BWGs in the

Bommanahalli zone, to understand the

on-ground challenges and potential

opportunities to strengthen capacities and

support systems for improved solid waste

management by BWGs. The baseline

assessment was conducted using

participatory approaches adapted to suit

stakeholder consultations on SWM, with

extensive engagement of all the dierent

stakeholder groups that operate in the SWM

ecosystem in Bengaluru. In particular, there

was a

focus on engaging

with groups who are

marginalised, vulnerable

and excluded from

consultative or

decision-making

processes. The insights

compiled from all these

stakeholder engagements

The overarching objective of the GGND

pilot initiative is for cities to contribute

as world leaders to the transition to

net-zero and resilient economies by

ensuring that local climate policies and

initiatives are designed inclusively and

have equitable impacts.

The GGND pilot initiative has been

tailored to match the unique needs and

contexts of each city. In Bengaluru, this

means supporting targeted

engagement by the city to advance

inclusive climate action that will deliver

on the priorities of the CAP through

improved service delivery, planning,

governance and overcoming

socio-economic barriers through

upskilling and capacity building of

frontline workers (Junior Health

Inspectors and waste workers) and

zonal city ocials involved in

managing solid waste management by

BWGs.

1

Under the 2012 notice, “bulk waste generator” was defined as any commercial entity generating more than 10 KGs of waste per day or a

residential apartment complex with more than 50 units. Since then, BWG classification for residential category has been increased from 50 units

and above or 10 KGs of waste per day to 100 units. In case of commercial/institutional categories, it has been increased to 100 KGs of waste per

day and/or located in an area above 5000 sq mts.

have resulted in an

assessment that sheds

light on the challenges

that the city faces in

managing the waste

produced by BWGs,

highlights existing best

practices, and identifies

opportunities to improve

equity and capacity

building - all of which can

inform future action.

11

Objectives of the baseline assessment

To understand the current best practices, challenges and opportunities across the whole BWG

system, stakeholder consultations were carried out in one municipal zone of the city -

Bommanahalli, with the following objectives:

2

3

1

4

5

Develop a comprehensive

stakeholder map for the

BWG ecosystem and

conduct stakeholder

analysis with a focus on

assessing the

vulnerability, power and

influence of each group.

Identify gaps/barriers in

the existing processes

and understand

opportunities in the

BWG ecosystem using

participatory

approaches.

Provide recommendations to strengthen the inclusion

of waste sector workers in BWG ecosystem.

Conduct a detailed

BWG mapping exercise

in selected parts of the

Bommanahalli zone to

estimate the climate

action impact potential

of BWG interventions.

Identify specific training

needs of the municipal

sta and other key

stakeholders.

12

3. Waste and climate change

Globally, the waste sector typically accounts

for 3 to 4 percent of total Green House Gas

(GHG) emissions. However, this emission source

only considers direct emissions primarily from

landfill methane emissions and incinerators. In

contrast, a life-cycle perspective of materials

management-related GHG

sources encompasses

emissions from acquisition, production,

transportation, consumption and end-of-life

treatment which add up to almost 50% of the

total emission (EPA).

As per the United States Environmental

Protection Agency, half the global GHG

emissions stem from the extraction and

processing of materials, fuels, and food.

Mismanaged waste is also impacting current

ecosystems to sequester carbon. Plastic waste

equivalent to one garbage truck is dumped in

the ocean every minute across the world. This

plastic breaks down into microplastics and

contributes to climate change both through

direct GHG emissions

Figure 1: System-based GHG inventory US (Domestic) emissions, 2006

Provision of

goods

29%

Provision of

food

13%

Appliances

and devices

8%

Building HVAC and

Kughting Lighting

25%

Other

passenger

transport

9%

Local passenger

transport

15%

Infrastructure

1%

Materials Management

and indirectly by aecting ocean organisms.

Plankton sequesters 30-50 percent of carbon

dioxide emissions from anthropogenic

activities, but after it ingests microplastics,

plankton’s ability to remove carbon dioxide

from the atmosphere decreases (Bauman,

2019).

Direct waste management

related emissions are

primarily attributed to

waste dumping, burning,

incineration and

transportation.

Typically in

low-income countries, about 90% of the waste

ends up in open dumps or is burned in the

open (Kaza et al, 2018). Burning of waste in

the open leads to the production of some

very harmful climate

pollutants such as black

carbon and is responsible for

half of the visible

smog in cities like New Delhi.

The 20 year GWP (Global Warming Potential)

of black carbon is up to 5,000 times greater

than that of carbon dioxide

(Tsydenova &

Patil, 2021)

. Biodegradable waste, buried

under piles of waste generates methane and

carbon dioxide as it decomposes in anaerobic

conditions.

India has more than

3,100 landfills and large

dumpsites and it creates

more methane from

landfill sites than any

other country

, according to GHGSat,

which monitors methane via satellites.

Ghazipur is one of the biggest ones in Delhi,

which on a single day in March, was spewing

out more than two metric tons of methane gas

every hour which if sustained for a year, would

have the same climate impact as an annual

emissions from 350,000 cars in the United

States

(Sud et al, 2022).

Transportation of waste is another big

contributor to GHG emissions, which is

dependent on the type of vehicles deployed

and the distance travelled. With the NIMBY

(Not in My Backyard) phenomenon taking hold

and the lack of space within cities, waste is

being transported long distances for

processing and disposal. It is not uncommon in

a city like Bengaluru that waste could be

transported almost 80 km away from the point

of generation for processing and/or disposal.

The vehicles deployed for primary and

secondary collection are most likely

13

5

0

%

i

n

l

a

n

d

fi

l

l

/

d

u

m

p

e

d

/

b

u

r

n

t

As per

Annual Report

2020-21 on

Implementation of

SWM Rules,

2016 by CPCB

5

0

%

w

a

s

t

e

p

r

o

c

e

s

s

e

d

14

heavy-duty diesel ones that are often poorly

maintained and therefore generate significant

GHG emissions.

Furthermore, cities in many developing nations

faced with mounting waste management

challenges are opting for waste incineration as

the main solution to manage waste. It is often

incorrectly promoted as a green, renewable

source of energy. The energy equation in

incineration is not very attractive when fed

with mixed waste of low caloric value, which is

the case in India, where the fraction of

biodegradable waste is higher compared to

developed countries.

Further, the source segregation rates are also

better in many developed nations thus

providing higher calorific waste for

incineration. The GHG emissions from waste

incineration are 580g CO2eq/kWh (Zero

Waste Europe, 2019) compared to 52 grams of

CO2eq/kWh (UNECE, 2021) emissions from

rooftop solar electricity. GHG emissions of all

other renewable energy sources are also much

lower than that from waste incineration plants.

Hence, countries like India

that are in the process of

developing their waste

management

infrastructure must choose

more sustainable solutions

instead of getting tied

down wixth capital and

emission intensive waste

incineration.

The lock-in impact of such capital-intensive

projects has been detrimental in many

developed nations because it creates a

constant demand for high calorific value waste

while starving the recycling industry of

recyclables. Decentralised, in-situ waste

management by BWGs can be a low hanging

fruit in this journey of sustainable waste

management practices.

15

4. Approach and methodology

4.1. Baseline assessment and stakeholder engagement

Desk based research

The first step of the baseline assessment was desk-based research on

relevant regulations, various participatory approaches, documentation and

case studies on solid waste management interventions. This research served

as a foundation to map out potential stakeholders, their roles and their level

of engagement in the waste management ecosystem in Bommanahalli zone.

Through secondary research, we enlisted key government ocials,

community-based organisations, waste management entities, dierent types

of BWGs and other organisations that play a role in waste management by

BWGs in Bommanahalli zone. The involvement and participation of all these

diverse stakeholders are key to evolving an inclusive approach to address the

current gaps in the solid waste management of BWGs.

1

STEP

2

STEP

Stakeholder identification and mapping

A comprehensive and multi-dimensional stakeholder map for waste

management in Bommanahalli zone was developed by combining the

insights gained from secondary research and interviews. These interviews

further helped understand the process, especially the community-led

initiatives with respect to BWGs in this zone. It also helped enlist some

additional stakeholders who were not prominently featured in existing

literature, especially informal and vulnerable stakeholders. These informal

and vulnerable stakeholders are also socially and economically

disadvantaged and hence have a higher exposure to the impacts of climate

change

(Michael et al., 2017)

. To understand dierent dimensions of

vulnerability, a framework was developed that classified these groups based

on socio-economic conditions, nature of employment, demographic,

environmental and health conditions, among others. Using these parameters,

the stakeholders were assessed for vulnerability under the stakeholder map.

Development and execution of stakeholder engagement plan

After the identification of the stakeholders, a stakeholder engagement plan

was developed using dierent participatory approaches for 10 (out of 12)

stakeholder groups. These are a combination of decision-makers, direct

actors (including those who are vulnerable) and advocacy groups. In the

course of this project, community participatory appraisal tools and certain

participatory urban planning tools were reviewed and adapted for the study.

3

STEP

16

Keeping these factors in mind, the stakeholder consultations and use of dierent

participatory approaches were designed and adapted to suit each stakeholder group

and to accommodate diverse sub-groups within these groups. For example, focus

group discussions (FGD) were deployed to engage vulnerable groups who may be

reluctant to communicate openly in a workshop format. For stakeholders with diverse

interests and schedules such as service providers and waste processors,

semi-structured interviews were employed as they speak more freely in one-on-one

conversations. The multifaceted participatory approaches ensured the inclusion of each

stakeholder group in these

consultations, with special attention to reaching out to less empowered groups, to

document their concerns and suggestions. Gender diversity was also integrated as a

cross-cutting theme in the entire process to listen to the voices of the women as a

large number of them participate in BWG waste management.

In all, 5 stakeholder workshops and more than 25 semi-structured interviews were

carried out with over 120 participants. Details such as dates, engagement formats and

participants for these workshops and interviews are available in Annexure 1. By

creating safe spaces for stakeholders to openly share their experiences, opinions and

thoughts, more inclusive and equitable conversations were facilitated. Intentionally

listening and prioritising the experiences of those identified as most vulnerable in the

solid waste management value chain helped develop insights into their specific needs

and challenges. The consultations were further enriched by leveraging the resources of

various agencies and stakeholders working with BWGs for solid waste management.

4.2. Mapping of BWGs

Typically, BWG databases available with the

city administrators tend to be outdated and/or

incomplete. Given that this data is critical for

SWM planning, implementation of government

schemes such as Swachh Bharat Mission

(Urban) and Swachh Sarvekshan and

understanding the climate impact of the waste

generated by BWGs, the project included

mapping of BWGs in five wards in

Bommanahalli zone.

For geospatial mapping of BWGs, ward maps

were obtained from the BBMP and thereafter,

the field team along with the waste collection

sta, mapped BWGs during the collection

process using an online tool. The data from the

field survey was reviewed, corrected,

harmonised and fed into Google Maps to

create BWG maps. In addition, the waste

collected from the BWGs was weighed in some

cases and estimated in others (using the

number and capacity of the bins). This led to

the creation of a database of BWGs which

included name, location, category of BWG and

quantum of solid waste generated per day.

This database was thereafter used in

interactions with BBMP representatives (as a

part of stakeholder engagement) who found

these to be very useful in their planning and

budgeting of SWM activities. The waste data

was also used to calculate the GHG-related

climate impact due to onsite management of

waste by BWGs.

17

5.1. Overview

The legal and policy framework for solid waste

management in India has undergone significant

evolution in recent years, with a focus on

improving sanitation, cleanliness and waste

management.

Several key policies and

regulations have played a

pivotal role in shaping this

framework, including the

Swachh Bharat Mission

(Urban), Swachh

Sarvekshan, and Solid

Waste Management Rules,

2016.

The

Swachh Bharat Mission (Urban)

is a

flagship program launched by the

Government of India in 2014 with the primary

goal of making urban areas in India clean and

open-defecation-free. This mission

emphasizes the construction of toilets, solid

waste management infrastructure, and

behaviour change campaigns to promote

cleanliness and proper waste disposal.

Swachh Sarvekshan

is an annual nationwide

cleanliness survey and competition conducted

by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Aairs

in India. It aims to gauge the progress of cities

in maintaining cleanliness, adopting best

waste management practices, and fostering

behavioural change among citizens It also

ranks cities and towns based on various

parameters, including waste management

practices, sanitation infrastructure, and citizen

feedback.

For example, the indicators under Swachh

Sarvekshan 2023 for scoring and points in the

competition include:

• Benefits extended to all sanitary workers

include provision of personal protective

equipment, training on waste

management, linkages to government

schemes and recognition of workers at

ward level.

• Capacity building of all sta, from Sanitary

Inspector and above which includes

completion of 4 courses through

e-Learning platform of Swachh Bharat

Mission (U).

• Skill development training of sanitation

workers through e-Learning platform of

Swachh Bharat Mission (U).

• Bulk waste generators doing onsite

processing of wet waste or getting the

wet waste collected and processed by

private players authorised by the

municipality.

5. Applicable legal and policy framework

for the BWG ecosystem

In this context, cities that want to

perform well at Swachh Sarvekshan

2023 and its later editions would seek

to provide benefits to their sanitary

and waste workers, carry out capacity

building and training sessions and

encourage onsite management of wet

waste by bulk waste generators. This

can be leveraged to ensure

participation and cooperation of

BBMP representatives in carrying out

skill development and empowerment

training for dierent stakeholders in

the BWG waste value chain.

18

The regulatory framework for solid waste management and BWGs in India is at national, state and

municipality levels.

Solid Waste Management Rules 2016 (“SWM Rules 2016”) which are

framed under the Environment Protection Act, 1986

No specific law. Brief provisions with respect to management

of waste and sanitation in Karnataka Municipal Corporations Act,

1976 and Karnataka Municipalities Act, 1964

Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike Solid Waste

Management (BBMP-SWM) Bye-laws, 2019

(“BBMP SWM Bye-laws”)

National

State

Municipality

5.2. Who are BWGs

Residential BWGs

• Apartments • Multi-dwelling units • Gated communities housing greater than

100 Units

Commercial BWGs

• All commercial entities which generate on an average more than 100 kgs of waste

per day and/or are located in an area above 5000 sq mts.

Institutional BWGs

A •

Any government, religious, educational, corporate, industrial, academic, research

institution, campus, buildings occupied by the government departments or

undertakings.

•

Public sector undertakings or hospitals, nursing homes, markets, and milk sales.

• O

utlets dealing with timber and horticulture like yards, nursery, gardens, all of which

generates on an average more than 100 kgs of waste per day and/or located in an area

above 5000 sq mts.

and/or

B •

Any entity which carries out public outdoor events (trade fairs, public events,

entertainment events/shows, rallies, sporting events), irrespective of any quantity

of waste generated and area occupied.

Under the BBMP SWM Bye-laws, BWGs are divided into residential, commercial and institutional

and they are defined as:

19

5.3. Duties of BWGs

Under the BBMP SWM Bye-laws, BWGs are required to segregate solid waste at source of

generation into the following categories:

Source segregation

CONSTRUCTION

& DEMOLITION

BIODEGRADABLE

including garden and

horticulture waste

NON

BIODEGRADABLE

including bulky waste

and E-waste

DOMESTIC

HAZARDOUS

+

including sanitary

waste

Onsite management of

biodegradable waste

(

Processed through composting or

bio-methanation within the premises itself,

to the extent of space available)

Osite management of

biodegradable waste

(If space within the premises is not

available)

Authorised waste processor for collection, processing and disposal

of segregated solid waste (including non-biodegradable waste,

domestic hazardous wasteand sanitary waste) on mutually

agreed terms including fees for such services.

5.4. BBMP SWM bye-laws: Welfare, occupational safety and training

Under the BBMP SWM Bye-laws, BBMP is required to comply with the following:

1. Issue identity cards to pourakarmikas and other eligible waste workers.

2. With regard to pourakarmikas and other eligible waste workers, compliance with all labour and

welfare regulations, including wages, working hours, holidays, and statutory benefits like

provident fund, employee's state insurance, and maternity benefits.

Welfare and Occupational Safety

20

3. Provide regular medical check-ups for pourakarmikas

2

and other eligible waste workers to

monitor occupational diseases.

4. Ensure the provision of following protective equipment and facilities to pourakarmikas,

door-to-door waste collection sta, waste processing facility sta and and other eligible

workers:

Uniforms Protective

footwear

Reflective

jackets

Raincoats Hand

gloves

Masks

Other

appropriate

gears

Two pairs, once a year Once every two months

2

Street sweepers who collect street sweeping wastes and carry out cleaning of public places.

Under BBMP SWM Bye-laws, BBMP has the duty to provide the following:

1. Periodic training through reputable institutes or government agencies to educate

pourakarmikas and its other workers involved in handling and management of solid waste on

various topics relating to waste management.

2. Information to the public about composting, bio-gas generation, reuse and recycling and

decentralised processing of waste at a community level by conducting training classes,

seminars, workshops and Compost Santhes (markets or events promoting composting).

Training

21

6. Overview of Bommanahalli zone

Bommanahalli Zone is one of the zones located

in the south of the city and it is further divided

into 2 distinct divisions: Bommanahalli and

Bengaluru South. Each of these divisions

comprises 8 wards (which are proposed to be

further split into 27 wards in the future) and the

details of these wards are annexed as

Annexure 2.

With respect to management of solid waste,

the ocials at BBMP are split between the

head/central oce and at zonal levels. The

organisation structure below highlights the

ocials that are critical for the supervision and

monitoring of solid waste management

activities and processes at the head and zonal

oces.

In addition, there is also involvement of the

Health Department through Senior Health

Inspectors who are also responsible for

monitoring waste generators such as

restaurants and hotels from a hygiene

perspective.

Figure 3: Bommanahalli zonal map with ward spatial distribution

Uttarahalli

(184)

Vasanthpura

(197)

Yelchenahalli

(185)

Jaraganahalli

(186)

Puttenahalli

(187)

Konankunte

(195)

Anjanapura

(196)

Gottigere

(194)

Begur

(192)

Arakere

(193)

Bilekhalli

(188)

Bommanahalli

(175)

HSR Layout

(174)

Hongasandra

(189)

Mangammanapalya

(190)

Singasandra

(191)

Special Commissioner

Joint Commissioner

Superintendent Engineer

Assistant

Superintendent Engineer

SWM Junior Health

Inspector

Head/

Central

Oce

Zone

Level

Division

Level

Ward

Level

Figure 2: Organization structure

Map not to scale

22

7. BWGs in Bommanahalli and their

climate impact

It is estimated that almost

30-40% of solid waste in a city like Bengaluru

is generated by BWGs.

(CPHEEO, 2017)

Solid waste

generated

5000 TPD

Solid waste

(35% BWGs)

1750 TPD

200 kgs of

solid waste

per day

per BWG

Approximately

8,750 BWGs

=

Estimated for Bengaluru

7.1. Mapping of BWGs

As a part of this project, BWGs in 5 wards in Bommanahalli zone which included HSR Layout (Ward

174), Bommanahalli (Ward 175), Hongasandra (Ward 189), Mangammanapalya (Ward 190) and

Singasandra (Ward 191) were mapped. The BWGs were categorised into:

Apartment complexes

Residential

BWGs

Hotels, restaurants with and without seating, supermarkets,

tea shops/bakery/juice shops, marriage halls, oce buildings,

religious places & technology parks

Commercial

BWGs

Schools, colleges, government and private institutions

Institutional

BWGs

23

Figure 5: WGs mapped in HSR Layout

Figure 4: BWGs mapped in Hongasandra

24

The mapping exercise identified a total of 183 BWGs in five wards and it was estimated that they

generate approximately 42 TPD of solid waste. The graphs below illustrate the ward-wise and

category-wise bifurcation of BWGs across the five wards. By applying the extrapolation

methodology after removing outliers to encompass a broader scope of 16 wards, it can be

reasonably inferred that the entirety of the Bommanahalli zone comprises of over 447 BWGs,

thereby contributing to an approximate solid waste generation of 100 TPD.

Figure 7: Category-wise split of BWGs in 5 wards

Figure 6: Ward-wise split of BWGs in 5 wards

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

Residential

BWGs

Commercial

BWGs

Institutional

BWGs

No. of BWGs

103

79

1

0

20

40

60

80

100

HSR Layout Singasandra Mangammanapalya Bommanahalli Hongasandra

88

46

22

15

12

No. of BWGs

25

7.2. GHG emissions by BWGs

Overall GHG emissions per ton of waste

managed at a city level are dependent on

multiple factors, most importantly the waste

composition. To get an estimate on the likely

contribution of the BWGs, data was taken

from a recent study done for the city of Ho

Chi Minn in Vietnam, using the IPCC

guidelines

(Verma RL, Borongan G., 2022)

.

The following section details the impact of

BWGs segregating their waste and managing

it within their premises as required by the

regulations.

(i) Impact of segregation and

biomethanation

Segregation would significantly improve the

recycling potential of non-biodegradable

waste. India has a large informal sector that

sorts and channelises non-biodegradable

waste for resource recovery. Further, waste

generated from residential BWGs or

commercial BWGs such as oces and/or

technology parks has a higher proportion of

cardboard, white paper and high-value plastic

waste such as PET and HDPE which has a

better value proposition and recycling rates.

Hence, the segregation of waste by BWGs is

especially important to ensure improved

resource recovery.

As per the US EPA

estimate, every ton of waste

recycled results in 2.89 tons of

CO2e reduction.

Apart from the recycling of

non-biodegradable waste, the segregated

biodegradable waste from BWGs can be

composted or sent to biogas plants. Waste

generated by restaurants, hotels and other

food joints is especially suitable for

anaerobic digestion in biogas plants.

As per the study done in China, the

GHG reduction of about 1 ton

CO2e (Zhang et al., 2020) was

estimated for 1 ton of food waste

diverted from landfills and

processed through anaerobic

digestion.

While reduction in GHG emissions due to

anaerobic digestion of biodegradable waste is

significant, it is challenging to operate

decentralised plants that have a capacity of

100 kg to 5 TPD in a financially and

operationally viable manner. Therefore, from a

GHG perspective, it is best to transport

biodegradable waste from BWGs to large

biogas plants where the gas can be deployed

26

Figure 8: Daily GHG emissions reduction due to processing of waste at city and zonal level

0

500

1000

1500

2000

Tons of CO2e

Due to

recycling

3

Due to anaerobic

digestion in

biogas plant

4

Due to processing of

biodegradable and

non-biodegradable wastes

1000

58

875

50

1875

108

3

Assuming, 20% of the waste generated by BWGs is the recyclable non-biodegradable waste.

4

Assuming 50% of the total waste generated by the BWGs is biodegradable, this translates into 875 TPD of biodegradable waste being

generated in Bengaluru and 50 TPD of biodegradable waste being generated in Bommanahalli Zone.

5

Beschkov, 2021 (Source: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/79776).

6

1 ltr of diesel generates 2.68 kg of CO2e. (Source: https://connectedfleet.michelin.com/blog/calculate-co2-emissions/) and the typical fuel

eciency is 3 km per ltr hence 0.893 kg of Co2e per km.

7

Assuming the waste needs to be transported 40 km one way. To haul 875 tons of waste, about 88 such trips would be deployed and they

would cover 7040 Km per day. This would translate into about 6 tons of CO2e of savings per day.

8

Assuming the waste needs to be transported 50 km one way. To haul 50 tons of waste, about 5 such trips would be deployed and they would

cover 500 Km per day. This would translate into about 0.4 tons of CO2e of savings per day.

as a replacement for fuel in the form of CBG

(used for cooking or transportation) instead of

the gas being used for electricity generation

which is not attractive from energy generation

(only 35% eciency

5

) or GHG perspective

(EPA, 2016)

. India’s energy neutrality is tied

with expanding solar and shifting to electric or

gas based transportation

(Jain, 2023)

. The

CNG infrastructure is getting ramped up with

plans to finally replace CNG with CBG. This

further tilts the scale in favour of CBG instead

of direct power generation from biogas.

(ii) Impact due to reduction in

transportation

The impact of on-site waste management in

terms of GHG emissions is also seen through

reduction in transportation. A typical

heavy-duty diesel compactor (most

compactors deployed have a 10-ton loading

capacity for transporting biodegradable

waste) generates about 0.893 kg CO2e per

kilometre

6

.

Bengaluru City Bommanahalli Zone

6 tons of CO2e

8

0.4 tons

of CO2e

7

Figure 9: Estimated GHG emissions from transportation

of waste

27

8. Identification of stakeholders, their

vulnerabilities and spheres of influence

8.1. Stakeholder identification

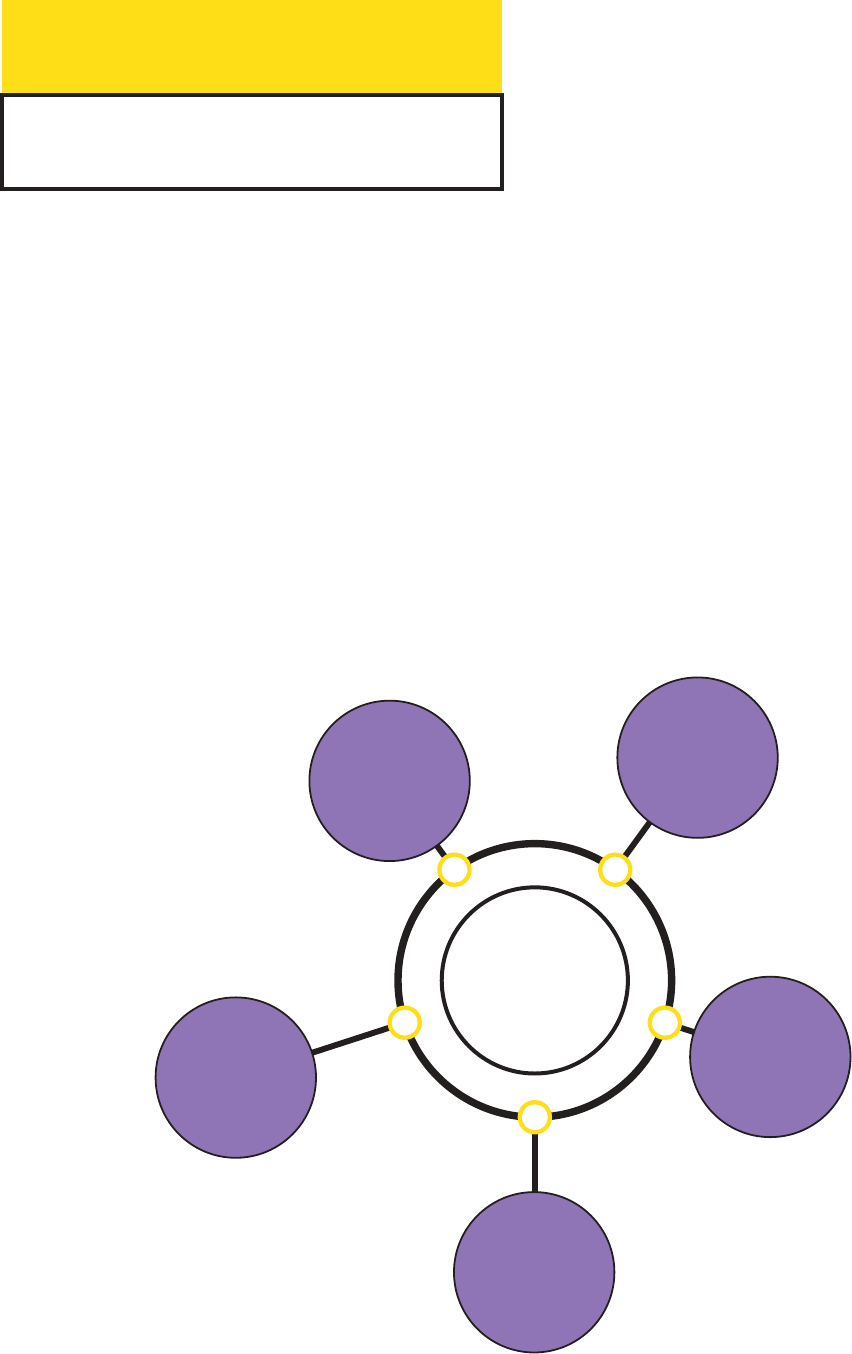

The landscape for the key stakeholders in BWG

ecosystem in Bommanahalli Zone, Bengaluru

can be grouped under four categories: Waste

Generators, Waste Collectors and Processors,

Regulators and Others, where some of these

groups have further levels/layers, such as in the

case of Waste Processors and BBMP. The

details of the stakeholders in the BWG

ecosystem in Bommanahalli zone are mapped

in Figure 10 below and their roles and

responsibilities are set out in Annexure 3.

• Residential

• Commercial

• Institutional

• BAF - Bangalore Apartment

Federations

• Civil Society Organisations

• BBMP - JHI

• BBMP - Senior

ocials

• Elected

Representatives

• Ward Contractor

• Service Provider/authorised

waste processor - O site

• Service Provider - In Situ

• Piggeries

• Product Sellers

Waste collection

and processing

sta

Figure 10: Categories of stakeholders in BWG ecosystem

Waste

Generators

Other

Interest

Groups

Regulators

Waste Collectors

and Processors

28

Residential

Residents Welfare Association (RWA) and/or Apartment

Owners/resident’s Association.

Commercial

Owners which could be individuals, proprietorships, partnerships,

companies etc.

Institutional

Depending on the type of institution such as educational, government,

religious etc., it could be the managing committee of such institution.

Under the BBMP SWM Bye-laws, BWGs are classified into “Residential”, Commercial”, and

“Institutional”. The key decision makers at these BWGs are the following:

(i) Waste Generators

These decision-makers decide on how the waste generated in their premises is managed i.e.,

on-site, o-site by service providers or through BBMP ward contractors. As evident from various

types of generators within BWGs, it is not a monolith group and their concerns, aspirations,

engagement and understanding of waste management vary significantly.

These are private entities that are implementers which collect and process the waste generated by

the BWGs, some of them are authorised while others are not. There are a variety of waste collectors

and processors as some only collect (such as Ward Contractor), some process waste on-site

through composting and/or biomethanation and finally, there are o-site processing and disposal

entities (both formal such as authorised waste processors and informal such as piggeries). Within

this group, there is a second level of stakeholders i.e., the group that handles the waste first hand

which are the following:

(ii) Waste Collectors and Processors

Primary waste collectors deployed by ward contractors and o-site vendors.

Housekeeping sta and waste workers who collect and process waste on-site.

Waste workers who process waste o-site.

This group of stakeholders are decision makers and enforcers who are responsible for formulating

the rules and policies on waste management and thereafter, enforcing these. In the BWG system,

this primarily consists of the municipality i.e., BBMP and the elected representatives such as the

mayor, ward councillors, members of the legislative assembly etc.

BBMP has also been split into two groups with a second level consisting of Junior Health

Inspectors (JHIs) as they are the frontline sta for monitoring SWM systems and enforcing related

regulations.

(iii) Regulators

This is an umbrella group covering advocacy groups such as civil society and community-based

organisations such as the HSR Citizen's Forum (HCF) and Solid Waste Management Round Table

(SWMRT) have carried out significant work in increasing awareness and building capacities of waste

generators and BBMP sta for source segregation and onsite management of biodegradable waste.

(iv) Other Interest Groups

29

The involvement of various stakeholders in waste collection and the flow of biodegradable waste

from generation to disposal is visually depicted in the figure below:

Residential

BWGs

Commercial

BWGs

Institutional

BWGs

Piggeries

Ward

contractors

On-site

processing

composting/

biogas

Authorised

service

providers/waste

processors

Unauthorised

vendors

PiggeriesDumping

BBMP processing

facilities/landfill

O-site processing

facilities

Figure 11: Waste flow from BWGs

30

8.2. Vulnerability and power analysis

The stakeholders in the BWG ecosystem

range from powerful decision makers such as

elected representatives, senior administrative

ocers to certain marginalised groups who

have been historically and presently excluded

from the decision-making processes.

Therefore, it was considered important to do

an assessment of the levels of vulnerability

and the power to influence among the

stakeholders. These assessments allowed for a

clear understanding of the dierence in equity

of power amongst these stakeholders and

their possible engagement in the study.

At the start of the study, 6 indicators were

considered to assess the vulnerability of the

stakeholders. However, as the project

evolved, the criteria for vulnerability of all

stakeholders was expanded to 15 indicators

to ensure inclusivity and equity within the

BWG ecosystem

(Srivastava, 2020;

Mohapatra, 2012; Michael et al., 2017)

.

A stakeholder has been rated as ‘High’ on vulnerability if the group satisfies 10 or more criteria

out of the 15 listed above. A stakeholder has been rated as “Medium” if the group satisfies 5-7

criteria out of the 15. A stakeholder has been rated as “Low” if the group satisfies 3 or fewer

criteria out of the 15. Each stakeholder was also assessed to gauge the power they have over

influencing change in the BWG ecosystem. This access to power determines their ability to

resolve existing issues with regard to BWGs.

Socio-

economic

indicators

• Income and poverty levels: Low income or living below the poverty line

• Education levels: Low educational attainment or lack of access to education

• Employment status: Contractual or impermanent nature of employment

• Housing conditions: Poor housing conditions

• Environmental degradation: Exposure to pollution

• Risk of occupational health concerns: High risk of Occupational Health

concerns

• Access to healthcare: Inability to/limited access to governmental and

private healthcare facilities and services

Environmental

and health

indicators

• Age: The very young and the elderly are more vulnerable

• Gender: Women are typically more vulnerable than men

• Migration status: Vulnerability is higher among migrant labour

Demographic

indicators

• Access to legal rights: Limited access to legal protections and rights

• Recognition: Lack of registration or recognition with regulatory authorities

• Protection from harassment: Absence or inadequacy of safety nets to

protect from work-related harassment

Institutional

and

governance

indicators

• Savings and assets: Lack of savings or assets to cope with economic shocks

• Access to financial information: Limited financial literacy and access to

banking services

Economic and

financial

indicators

31

Vulnerability Power to influence Low Medium High

Residential BWG represented by RWA

Generate biggest quantum of waste

among BWGs and have the power

to implement onsite biodegradable

waste processing facilities with no

outside influence.

• Inadequate safety nets for SWM

related harassment in some cases

Commercial / Institutional BWG represented by owners

Generate significant quantum of

waste among BWGs, have the

monetary resources and power to

implement onsite biodegradable

waste processing facilities with no

outside influence.

• Inadequate safety nets for SWM

related harassment in some cases

BBMP - JHI

JHIs are the front-end team for

enforcement of BWG regulations at

the ground level. Therefore, they are

the regulator that interacts with

BWGs continuously and can

influence their waste management

processes.

• Insucient Training

• Contractual nature of employment

• Limited access to legal protections

• Inadequate safety nets for work

related harassment

• Low income

• Limited access to legal protection

due to contractual nature of

employement

BBMP - Others

As the lack of enforcement has

emerged as a key issue based on

the analysis, senior ocials at

BBMP have been rated as the most

important stakeholder to influence

the BWG ecosystem

• Inadequate safety nets for work

related harassment in some cases

Service provider/authorised waste processor - O Site & onsite

With an enabling ecosystem, they

can oer waste handling and

processing services to BWGs. Their

influence is limited to professional

and holistic waste management

services to willing BWGs.

• Contractual nature of engagement

• Lack of registration given that the

empanelment system is in abeyance

• Exposure to mixed waste

32

Piggeries

One of the biggest disposal

destinations for biodegradable

waste generated by BWGs which

are completely unregistered,

unmonitored and regulated. Given

their vulnerability and invisibility,

they do not wield any power to

bring about systemic change.

• Lack of registration

• Low income

• Poor education

• Operating in the outskirts of the city

and challenging working hours

• Exposure to mixed waste

• Limited access to healthcare facilities

• Migrant labour

• Inadequate safety nets for work

related harassment

• Limited access to legal protections

• Limited financial literacy and access

to financial services

Ward contractor

To an extent, the ward contractor is

the channel through which the

regulations with respect to BWGs

are flouted because the

door-to-door system caters to

BWGs as well in some cases.

• Contractual nature of engagement

• Lack of registration to service BWGs

• Exposure to mixed waste

Waste collectors and o-site processing sta - ward contractor and

service providers/authorised waste processors

Waste collection sta implement

waste segregation and primary

collection.

Waste processing sta work on the

recovery of resources from waste.

They have no power to change

processes or systems in the BWGs

waste value chain

• Low income

• Poor education

• Contractual nature of employment

• Poor quality of housing

• Exposure to mixed waste

• Limited access to healthcare facilities

• Migrant labour

• Lack of registration

• Inadequate safety nets for work

related harassment

• Limited access to legal protections

• Lack of savings or assets

• Limited financial literacy and access

to financial services

Elected representatives

Significant on-ground change with

respect to SWM requires political

will and therefore, political buy-in is

crucial for enforcement of BWG

regulations.

• None

33

Waste management sta – onsite and housekeeping sta at BWGs

Housekeeping sta play an

important role in waste collection

and source segregation. On-site

waste management sta process

the waste. While they have an

important role in proper

segregation and ecient waste

processing, they do not have the

power to bring systemic change in

the BWG ecosystem.

• Low income

• Attainment of low education

• Contractual nature of employment

• Poor quality of housing

• Exposure to mixed waste (in some

cases)

• Primarily, women

• Limited access to healthcare facilities

• Limited access to legal protections

• Lack of savings or assets

• Limited financial literacy and access

to financial services

Figure 12: Vulnerability assessment and power analysis of stakeholders

Civil society & community-based organisations

They play a very important role in

behaviour change and capacity

building of BWGs

• Lack of recognition

• Lack of financial assets

As a result of these assessments, it is evident

that stakeholder groups who are the front-end

team that conducts waste management

operations at the BWG level such as waste

collection sta and housekeeping sta are the

most vulnerable. They also have very limited

power to influence systemic change in the

BWG ecosystem. On the contrary,

decision-makers and implementation agencies

who manage and govern the BWG ecosystem

such as elected representatives, and senior

personnel at BBMP and BWGs are not vulnerable.

The power to influence change also largely

rests with these least vulnerable groups of

decision-makers at BBMP, elected representatives

and BWGs. While the inputs of these groups

are consistently taken into account by virtue of

the power they enjoy, the inputs of the most

marginalised groups are not. Private service

providers exist as businesses in the BWG

ecosystem and are not very vulnerable;

however, they do not enjoy much power to

influence systemic change given that they

remain subject to SWM regulations and

policies of the regulators. In the absence of an

enabling environment such as enforcement of

BBMP SWM Bye-laws and regular monitoring

by the BBMP, it is challenging for the private

service providers to oer their services to

BWGs on a sustainable basis.

The vulnerability and power analysis assessment

not only served as a vital framework for

understanding the dynamics of the BWG

ecosystem but also informed the approach to

engage with these stakeholders. These

assessments amplify the need for participatory

approaches that create avenues for all

stakeholders to provide inputs, especially those

that are most invisible and unheard. While

these stakeholder groups may not be

very

influential in resolving a majority of issues

relating to waste management by BWGs, the

engagement was planned with them as a part

of the project due to their vulnerability. This

ensured insights for developing tailored strategies

and support mechanisms to address the unique

needs and challenges faced by each group.

34

9. Stakeholder engagement using

participatory approaches

9.1. Overview

In the context of solid waste management in

India, there is limited literature or

documentation available on deploying

participatory approaches to engage

stakeholders. Solid waste management is a

critical issue and traditional top-down

approaches have often proven ineective. As a

result, participatory approaches have emerged

as a promising methodology that actively

involves varied groups of stakeholders in the

decision-making processes.

The overall objectives of the stakeholder

engagement were the following:

• Documenting the current situation of waste

management by BWGs.

• Identifying current problems and

challenges.

• Identifying steps to improve the current

situation.

• Defining roles and responsibilities of the

dierent stakeholders in the improved

situation.

9.2. Objectives of stakeholder

engagement

Stakeholder workshop with BWG collection sta

35

9.3. Participatory approaches adopted in stakeholder consultations

A brief description of the key consultations is provided below:

The stakeholder consultation workshop was

initiated through a participatory tool called Life

Histories, which allowed participants to share

personal accounts of their experiences working

as JHIs and ease into the workshop. This was

followed by using Stratified Resource Mapping,

where they identified roles and responsibilities

relevant to themselves, BWGs and other

stakeholders.

For each of the stratified responsibilities

assigned to themselves, JHIs then formed

groups and worked on formulating a Constraint

Analysis where they identified and described

problems/constraints related to each of the

responsibilities in detail. Once resources and

constraints were identified, the JHIs formulated

a Solutions Matrix where they detailed the

possible ways and tools to mitigate the

identified constraints.

(i) Stakeholder consultation workshop with Junior Health Inspectors (JHIs)

“We started monitoring BWGs

recently and are therefore not

completely clear about the rules

relating to BWGs and our related

responsibilities. Having clarity

about the regulations and our

responsibilities would go a long

way in improving the confidence

with which we can approach the

BWGs and the eectiveness of our

monitoring”

- JHI, Bommanahalli

Stakeholder workshop with JHIs

36

The workshop for these two stakeholder

groups was carried out as Focus Group

Discussions (FGD) given the vulnerability of the

group and possible reluctance to communicate

openly in a workshop format. Each FGD was

guided by context setting and a list of

questions that allowed participants to provide

an in-depth understanding of the challenges

they face, the interventions required to address

them and their inputs on the prioritization of

certain interventions over others.

(ii) Stakeholder consultation workshop with waste collection sta and

housekeeping sta for BWGs

“We know that our work is critical to

the city, however, there is a lack of

recognition of it by the government

and the public. At the very least, we

should be given identity cards and

one day o in a week for our

well-being.”

- BWG collection sta

For residential & commercial BWGs as well as

BBMP ocials, given the diverse interests and

schedules of these stakeholders,

semi-structured interviews were conducted to

thoroughly document their inputs, as and when

participants were available within the duration

of this project. For service providers and civil

society groups, it was noted that these were

not homogenous groups and very divergent

work was being undertaken by individual

stakeholders in these two groups. As a result, it

was decided that semi-structured interviews

would be the most appropriate tool to capture

their distinct inputs on the BWG ecosystem.

(iii) Semi-structured interviews with residential and commercial BWGs, BBMP

ocials, service providers and civil society groups

“Our work is dignified because the

residents segregate their waste

properly and the RWA members

support us whenever there is a

problem in the waste management

system.”

- Housekeeping sta at a BWG

Stakeholder workshop with housekeeping sta at Salarpuria Serenity

37

10. Key findings from stakeholder

engagement

Stakeholder group outcomes/findings

BBMP

• Mapping of BWGs at scale

• Training and capacity building needs

• Need for reporting and monitoring formats

• Necessity of enforcing existing provisions

• Replicating existing best practices

• Enhancing collaboration between departments

• Limited knowledge of impact of SWM on climate change

JHIs

• Importance of defining roles & powers wrt BWGs

• Training and capacity building needs

• Improved administrative & political support

• Requirement for IEC campaign design & implementation

• Relevance of recognition & job security

• Limited knowledge of impact of SWM on climate change

Waste Collection

Sta

• Provision of identity cards, uniforms & safety equipment

• Demand for improved working conditions

• Enhancing access to quality healthcare & housing

• Relevance of recognition & job security

BWGs

• Importance of awareness & IEC

• Training and capacity building needs

• Development of market for compost

• Improved financial viability of in-situ biodegradable waste management

• Need for incentives and rebates

Civil Society

Groups

• Necessity of regular funding support

• Increased administrative & political support

• Enhanced collaboration with BBMP

• Training and capacity building needs

• Necessity of monitoring mechanisms

Service

Providers

This section provides the findings from the stakeholder consultation workshops and

semi-structured interviews conducted in the course of this study. The stakeholder engagement

sought to understand the diverse inputs of various stakeholders on the challenges they face, the

opportunities they foresee and the solutions that need to be devised or implemented to improve

the systems governing BWGs in Bommanahalli zone, Bengaluru.

38

10.1. Policy and enforcement

All stakeholders detailed the gaps in enforcement of policy and stressed on the need for robust

institutional mechanisms, specifically in the following areas:

There is a need for enforcing existing

provisions relating to management of waste by

BWGs under the SWM Rules, 2016 and the

BBMP SWM Bye-laws. Additionally, a range of

responsibilities can only be fulfilled by the

BBMP such as creating databases of BWG,

establishing roles and powers of JHIs with

regard to BWGs, instituting an eective

empanelment process for service providers and

for in-situ vendors and authorised waste

processors, ensuring the BBMP door-to-door

collection and processing systems does not

cater to BWGs, providing incentives/rebates

for BWGs carrying out in-situ waste

management, establishing internal reporting

systems for BWGs and service

providers/authorized waste processors and

ensuring on ground implementation such as no

dumping and burning of waste in the open.

(i) Enforcement of existing provisions

(ii) Need for collaboration

In addition, regular dialogue with political leaders could be maintained to share updates on solid

waste management systems and to seek their intervention in case of issues or bottlenecks that can

be resolved by them.

There are several areas of SWM where

collaboration between stakeholders could

prove eective. Some examples include:

• Increased coordination between dierent

departments like Bengaluru’s electricity

supply entity (BESCOM) for sharing

databases of waste generators and

mapping of BWGs,

• Karnataka State Pollution Control Board

(KSPCB) which provides permits and

conducts monitoring on dierent aspects

of urban infrastructure and waste,

• Collaboration with market associations

could increase enforcement of the

single-use plastic (SUP) ban,

• Collaboration with education institutions

could increase citizen involvement and

awareness,

• Collaboration with experts and NGOs could

increase capacity building and training

opportunities,

• Involvement of police could be considered

for enforcement of penalties for

non-compliance.

39

10.2. Criticality of source segregation

For any successful implementation of in-situ

biodegradable waste management and dignity

of work for any workers handling solid waste, a

crucial first step that was identified is

segregation of waste at source. When waste is

received with consistently high segregation

levels, stakeholders report an increased ability

to smoothly operate in-situ biodegradable

waste management, increased resource

recovery of non-biodegradable waste and

increased access to dignified and safer working

conditions. The level of segregation also

impacts the eciency of the waste processing

systems because contaminated waste creates

the need for additional infrastructure, human

resources and time that goes into sorting and

salvaging dierent waste types, in a waste

collection and processing system that is

already overloaded.

Certain stakeholder groups like commercial

BWGs were flagged for consistently providing

mixed waste and workplace injuries associated

with handling mixed waste that consists of

hazardous waste types (like broken glass,

metal, needles, etc.) were also reported. In

cases of contamination, the issue is often

plugged by providing awareness, printed

instruction sheets, refusing to collect mixed

waste, penalties, and strict enforcement of the

city’s legislation on solid waste management

among others.

40

Leading the way for in-situ composting

Salarpuria Serenity, a residential BWG with 200 apartments, is a model for in-situ composting

and worker welfare in Bommanahalli Zone after years of consistent resident interventions. A

group of residents at Salarpuria Serenity had a long-standing interest in waste management

and they fine-tuned their in-situ composting practices from 2016 to 2023. In 2016, in-situ

composting began with 2 composters(“Aaga” Composters from the brand Daily Dump), now

expanded to 24 which manages approximately 150 kgs of biodegradable waste generated

daily. They took several steps to ensure sustainable in-situ composting and these include

discontinuation of trash chutes to discourage dumping of mixed waste. New tenants receive

printed waste management instructions, and resident volunteers conduct awareness

campaigns and communication. Strict waste segregation into three categories is enforced,

and sta can reject mixed waste collection. A chain of command, involving RWA members

and building manager, addresses issues relating to source segregation and other complaints.

The aesthetic appeal of this composting unit, outdoor location and regular cleaning have

ensured a lack of smell, visibility and more know-how among the residents regarding the

composting process underway. The housekeeping sta also receive waste management

training, health checkups, protective gear, uniforms, and bonuses. Very importantly, the RWA

members ensure that a general sense of respect and gratitude is extended to the sta by all

residents. The limited space requirement, resident participation and worker welfare make this

an ideal replicable model for in-situ composting in residential BWGs.

10.3. Capacity building opportunities

In several stakeholder workshops, clear gaps in training and capacity building were identified and

opportunities to bridge these gaps were formulated by the participants.

(ii) Junior Health Inspectors (JHIs) in

the BBMP started monitoring BWGs

approximately 18 months back and their roles

and responsibilities concerning BWGs have not

been documented in writing. In addition, there

is limited knowledge of the BBMP SWM

Bye-laws, which along with a lack of clearly

defined roles and responsibilities results in an

inability to confidently enforce regulations.

Additionally, a lack of technical expertise in

in-situ biodegradable waste management

limits their ability to eectively monitor in-situ

biodegradable processing systems, provide

support and issue fines for defaulters among

others.

JHIs also highlighted that eective Information,

(i) In most residential BWGs, in-situ

interventions hinge on personal interest and

there is a need for building capacities, creating

awareness and building institutional processes

that ensure installation and continuity in

operating in-situ composting or biogas units,

irrespective of availability of persons with

personal interest in the matter. For residents

who have a personal interest in operationalising

in-situ biodegradable waste management,

there is a need for building their capacities in

terms of technical expertise, ability to

troubleshoot, and ability to engage with other

residents on matters related to SWM, among

others to ensure that they can continue to

champion in-situ biodegradable waste

management in their respective buildings.

41

sensitisation and training of BWGs, sharing

references of experts and vendors for in-situ

biodegradable waste management, ensuring

that collection and transportation is only done

by an authorized service provider, conducting

monitoring visits, documenting

non-compliance and understanding the

reasons for it, collecting data, issuing notices,

and fines can be done in a more conducive

environment.

Education & Communication (IEC) materials

could result in positive reinforcement of

SWM-related obligations and activities, as