International Institute of Business Analysis

Business Analysis

Body of Knowledge

A Guide to the

Version 1.6

International Institute of Business Analysis

Guide to the Business Analysis Body of Knowledge

Draft Material for Review and Feedback

Release 1.6 Draft

Table of Contents

A Guide to the Business Analysis Body of Knowledge, Release 1.6

©2006, International Institute of Business Analysis

http://www.theiiba.org/

i

Table of Contents

CHAPTER 1: PREFACE AND INTRODUCTION

TABLE OF CONTENTS............................................................................................................................................ I

PREFACE TO RELEASE 1.6.................................................................................................................................... 1

1.1 WHAT IS THE IIBA BOK........................................................................................................................... 5

1.2 PURPOSE OF THE GUIDE TO THE IIBA BOK ........................................................................................... 5

1.3 DEFINING THE BUSINESS ANALYSIS PROFESSION............................................................................... 6

1.4 CORE CONCEPTS OF BUSINESS ANALYSIS............................................................................................ 6

1.4.1 DEFINITION OF A REQUIREMENT ..............................................................................................................................................................7

1.4.2 EFFECTIVE REQUIREMENTS PRACTICES ....................................................................................................................................................7

1.5 THE BODY OF KNOWLEDGE IN SUMMARY ........................................................................................... 8

1.5.1 ENTERPRISE ANALYSIS................................................................................................................................................................................8

1.5.2 REQUIREMENTS PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT....................................................................................................................................9

1.5.3 REQUIREMENTS ELICITATION....................................................................................................................................................................9

1.5.4 REQUIREMENTS ANALYSIS AND DOCUMENTATION...........................................................................................................................10

1.5.5 REQUIREMENTS COMMUNICATION .......................................................................................................................................................10

1.5.6 SOLUTION ASSESSMENT AND VALIDATION........................................................................................................................................10

1.5.7 COMPLEMENTARY CHAPTERS ................................................................................................................................................................10

1.6 THE BODY OF KNOWLEDGE IN CONTEXT ........................................................................................... 11

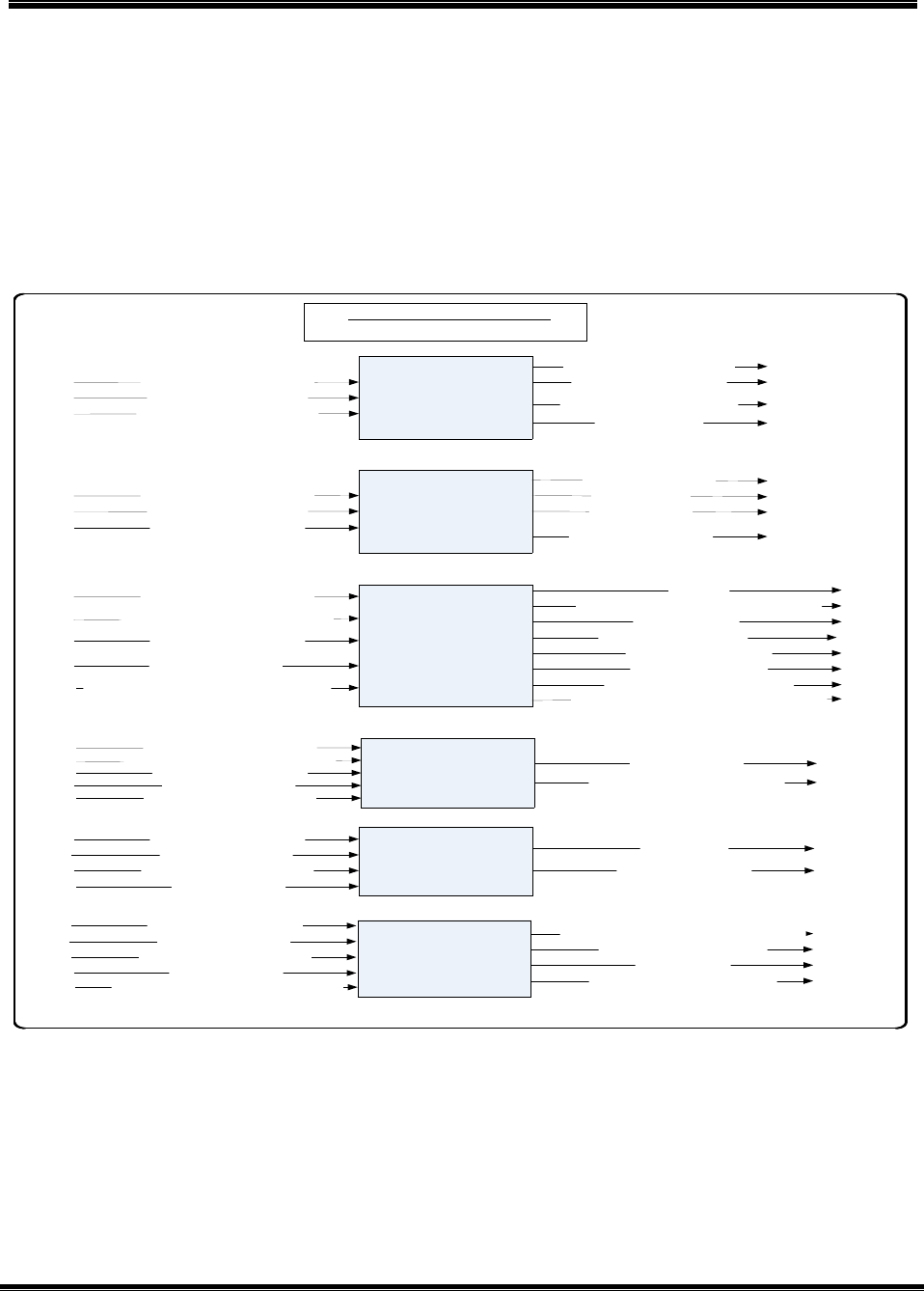

1.6.1 BODY OF KNOWLEDGE RELATIONSHIPS...............................................................................................................................................11

1.6.2 RELATIONSHIP TO THE SOLUTIONS LIFECYCLE..................................................................................................................................14

CHAPTER 2: ENTERPRISE ANALYSIS

2.1 INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................... 15

2.1.1 STRATEGIC PLANNING.............................................................................................................................................................................16

2.1.2 STRATEGIC GOAL SETTING.....................................................................................................................................................................17

2.1.3 THE BUSINESS ANALYST STRATEGIC ROLE .........................................................................................................................................18

2.1.4 THE BUSINESS ANALYST ENTERPRISE ANALYSIS ROLE......................................................................................................................19

2.1.5 ENTERPRISE ANALYSIS ACTIVITIES.........................................................................................................................................................19

2.1.6 RELATIONSHIP TO OTHER KNOWLEDGE AREAS .................................................................................................................................22

2.2 CREATING AND MAINTAINING THE BUSINESS ARCHITECTURE ........................................................ 22

2.2.1 PURPOSE....................................................................................................................................................................................................22

2.2.2 DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................................................................................................23

2.2.3 KNOWLEDGE.............................................................................................................................................................................................24

2.2.4 SKILLS ........................................................................................................................................................................................................25

2.2.5 PREDECESSORS.........................................................................................................................................................................................25

2.2.6 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .......................................................................................................................................................................25

2.2.7 STAKEHOLDERS ........................................................................................................................................................................................28

2.2.8 DELIVERABLES ..........................................................................................................................................................................................28

2.2.9 TECHNIQUES .............................................................................................................................................................................................28

2.3 CONDUCTING FEASIBILITY STUDIES................................................................................................... 32

2.3.1 PURPOSE....................................................................................................................................................................................................32

Table of Contents

A Guide to the Business Analysis Body of Knowledge, Release 1.6

©2006, International Institute of Business Analysis

http://www.theiiba.org/

ii

2.3.2 DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................................................................................................32

2.3.3 KNOWLEDGE.............................................................................................................................................................................................33

2.3.4 SKILLS ........................................................................................................................................................................................................33

2.3.5 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .......................................................................................................................................................................34

2.3.6 STAKEHOLDERS ........................................................................................................................................................................................37

2.3.7 DELIVERABLES ..........................................................................................................................................................................................37

2.3.8 TECHNIQUES .............................................................................................................................................................................................39

2.4 DETERMINING PROJECT SCOPE .......................................................................................................... 42

2.4.1 PURPOSE....................................................................................................................................................................................................42

2.4.2 DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................................................................................................43

2.4.3 KNOWLEDGE.............................................................................................................................................................................................43

2.4.4 SKILLS ........................................................................................................................................................................................................44

2.4.5 PREDECESSORS.........................................................................................................................................................................................45

2.4.6 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .......................................................................................................................................................................45

2.4.7 STAKEHOLDERS ........................................................................................................................................................................................46

2.4.8 DELIVERABLES ..........................................................................................................................................................................................46

2.4.9 TECHNIQUES .............................................................................................................................................................................................47

2.5 PREPARING THE BUSINESS CASE ........................................................................................................ 48

2.5.1 PURPOSE....................................................................................................................................................................................................48

2.5.2 DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................................................................................................48

2.5.3 KNOWLEDGE.............................................................................................................................................................................................48

2.5.4 SKILLS ........................................................................................................................................................................................................49

2.5.5 PREDECESSORS.........................................................................................................................................................................................49

2.5.6 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .......................................................................................................................................................................49

2.5.7 STAKEHOLDERS ........................................................................................................................................................................................51

2.5.8 DELIVERABLES ..........................................................................................................................................................................................51

2.5.9 TECHNIQUES .............................................................................................................................................................................................53

2.6 CONDUCTING THE INITIAL RISK ASSESSMENT...................................................................................54

2.6.1 PURPOSE....................................................................................................................................................................................................54

2.6.2 DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................................................................................................54

2.6.3 KNOWLEDGE.............................................................................................................................................................................................54

2.6.4 SKILLS ........................................................................................................................................................................................................54

2.6.5 PREDECESSORS.........................................................................................................................................................................................55

2.6.6 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .......................................................................................................................................................................55

2.6.7 STAKEHOLDERS ........................................................................................................................................................................................56

2.6.8 DELIVERABLES ..........................................................................................................................................................................................56

2.6.9 TECHNIQUES .............................................................................................................................................................................................56

2.7 PREPARING THE DECISION PACKAGE ................................................................................................. 57

2.7.1 PURPOSE....................................................................................................................................................................................................57

2.7.2 DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................................................................................................57

2.7.3 KNOWLEDGE.............................................................................................................................................................................................57

2.7.4 SKILLS ........................................................................................................................................................................................................57

2.7.5 PREDECESSORS.........................................................................................................................................................................................57

2.7.6 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .......................................................................................................................................................................57

2.7.7 STAKEHOLDERS ........................................................................................................................................................................................58

2.7.8 DELIVERABLES ..........................................................................................................................................................................................58

2.7.9 TECHNIQUES .............................................................................................................................................................................................58

2.8 SELECTING AND PRIORITIZING PROJECTS.......................................................................................... 58

Table of Contents

A Guide to the Business Analysis Body of Knowledge, Release 1.6

©2006, International Institute of Business Analysis

http://www.theiiba.org/

iii

2.9 LAUNCHING NEW PROJECTS ............................................................................................................... 59

2.10 MANAGING PROJECTS FOR VALUE ..................................................................................................... 59

2.11 TRACKING PROJECT BENEFITS ............................................................................................................ 60

2.12 REFERENCES .........................................................................................................................................60

CHAPTER 3: REQUIREMENTS PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT

3.1 INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................... 63

3.1.1 KNOWLEDGE AREA DEFINITION............................................................................................................................................................63

3.1.2 RATIONALE FOR INCLUSION ..................................................................................................................................................................63

3.1.3 KNOWLEDGE AREA TASKS......................................................................................................................................................................64

3.1.4 RELATIONSHIP TO OTHER KNOWLEDGE AREAS..................................................................................................................................64

3.2 UNDERSTAND TEAM ROLES FOR THE PROJECT ................................................................................. 64

3.2.1 TASK: IDENTIFY AND DOCUMENT TEAM ROLES FOR THE PROJECT ..............................................................................................65

3.2.2 TASK: IDENTIFY AND DOCUMENT TEAM ROLE RESPONSIBILITIES .................................................................................................68

3.2.3 TASK: IDENTIFY STAKEHOLDERS ............................................................................................................................................................72

3.2.4 TECHNIQUE: CONSULT REFERENCE MATERIALS..................................................................................................................................73

3.2.5 TECHNIQUE: QUESTIONNAIRE TO IDENTIFIED STAKEHOLDERS........................................................................................................75

3.2.6 TASK: DESCRIBE THE STAKEHOLDERS ..................................................................................................................................................76

3.2.7 TECHNIQUE: INTERVIEW STAKEHOLDERS TO SOLICIT DESCRIPTION ...............................................................................................78

3.2.8 TASK: CATEGORIZE THE STAKEHOLDERS.............................................................................................................................................81

3.3 DEFINE BUSINESS ANALYST WORK DIVISION STRATEGY ................................................................. 82

3.3.1 TASK: DIVIDE WORK AMONGST A BUSINESS ANALYST TEAM..........................................................................................................82

3.3.2 TECHNIQUE: BUSINESS ANALYST WORK DIVISION STRATEGY.........................................................................................................83

3.3.3 TECHNIQUE: CO-ORDINATION OF INFORMATION WITHIN THE TEAM ............................................................................................87

3.3.4 TECHNIQUE: KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER ..................................................................................................................................................90

3.4 DEFINE REQUIREMENTS RISK APPROACH .......................................................................................... 92

3.4.1 TASK: IDENTIFY REQUIREMENTS RISKS..................................................................................................................................................94

3.4.2 TASK: DEFINE REQUIREMENTS RISK MANAGEMENT APPROACH .....................................................................................................95

3.4.3 TECHNIQUE: REQUIREMENTS RISK PLANNING.....................................................................................................................................96

3.4.4 TECHNIQUE: REQUIREMENTS RISK MONITORING...............................................................................................................................98

3.4.5 TECHNIQUE: REQUIREMENTS RISK CONTROL .....................................................................................................................................99

3.5 DETERMINE PLANNING CONSIDERATIONS ......................................................................................100

3.5.1 TASK: IDENTIFY KEY PLANNING IMPACT AREAS ............................................................................................................................... 101

3.5.2 TASK: CONSIDER THE SDLC METHODOLOGY................................................................................................................................ 102

3.5.3 TASK: CONSIDER THE PROJECT LIFE CYCLE METHODOLOGY...................................................................................................... 104

3.5.4 TASK: CONSIDER PROJECT RISK, EXPECTATIONS, AND STANDARDS........................................................................................... 105

3.5.5 TASK: RE-PLANNING............................................................................................................................................................................. 108

3.5.6 TASK: CONSIDER KEY STAKEHOLDER NEEDS AND LOCATION .....................................................................................................109

3.5.7 TASK: CONSIDER THE PROJECT TYPE ................................................................................................................................................ 110

3.6 SELECT REQUIREMENTS ACTIVITIES .................................................................................................111

3.6.1 TASK: DETERMINE REQUIREMENTS ELICITATION STAKEHOLDERS AND ACTIVITIES .................................................................. 112

3.6.2 TASK: DETERMINE REQUIREMENTS ANALYSIS AND DOCUMENTATION ACTIVITIES .................................................................. 115

3.6.3 TASK: DETERMINE REQUIREMENTS COMMUNICATION ACTIVITIES .............................................................................................. 116

3.6.4 TASK: DETERMINE REQUIREMENTS IMPLEMENTATION ACTIVITIES ............................................................................................... 118

3.7 ESTIMATE REQUIREMENTS ACTIVITIES ............................................................................................119

Table of Contents

A Guide to the Business Analysis Body of Knowledge, Release 1.6

©2006, International Institute of Business Analysis

http://www.theiiba.org/

iv

3.7.1 TASK: IDENTIFY MILESTONES IN THE REQUIREMENTS ACTIVITIES DEVELOPMENT AND DELIVERY ............................................. 119

3.7.2 TASK: DEFINE UNITS OF WORK.......................................................................................................................................................... 120

3.7.3 TASK: ESTIMATE EFFORT PER UNIT OF WORK..................................................................................................................................121

3.7.4 TASK: ESTIMATE DURATION PER UNIT OF WORK.............................................................................................................................. 122

3.7.5 TECHNIQUE: USE DOCUMENTATION FROM PAST REQUIREMENTS ACTIVITIES TO ESTIMATE DURATION ................................ 123

3.7.6 TASK: IDENTIFY ASSUMPTIONS ........................................................................................................................................................... 125

3.7.7 TASK: IDENTIFY RISKS ........................................................................................................................................................................... 126

3.7.8 TASK: MODIFY THE REQUIREMENTS PLAN ....................................................................................................................................... 127

3.8 MANAGE REQUIREMENTS SCOPE .....................................................................................................129

3.8.1 TASK: ESTABLISH REQUIREMENTS BASELINE.................................................................................................................................... 129

3.8.2 TASK: STRUCTURE REQUIREMENTS FOR TRACEABILITY .................................................................................................................. 130

3.8.3 TASK: IDENTIFY IMPACTS TO EXTERNAL SYSTEMS AND/OR OTHER AREAS OF THE PROJECT ................................................. 135

3.8.4 TASK: IDENTIFY SCOPE CHANGE RESULTING FROM REQUIREMENT CHANGE (CHANGE MANAGEMENT) ............................. 136

3.8.5 TASK: MAINTAIN SCOPE APPROVAL ................................................................................................................................................. 138

3.9 MEASURE AND REPORT ON REQUIREMENTS ACTIVITY...................................................................138

3.9.1 TASK: DETERMINE THE PROJECT METRICS ..................................................................................................................................... 141

3.9.2 TASK: DETERMINE THE PRODUCT METRICS.................................................................................................................................... 142

3.9.3 TASK: COLLECT PROJECT METRICS................................................................................................................................................. 144

3.9.4 TASK: COLLECT PRODUCT METRICS ............................................................................................................................................... 145

3.9.5 TASK: REPORTING PRODUCT METRICS ............................................................................................................................................ 146

3.9.6 TASK: REPORTING PROJECT METRICS.............................................................................................................................................. 147

3.10 MANAGE REQUIREMENTS CHANGE ..................................................................................................150

3.10.1 PLAN REQUIREMENTS CHANGE.................................................................................................................................................... 150

3.10.2 UNDERSTAND THE CHANGES TO REQUIREMENTS ......................................................................................................................150

3.10.3 3.11.3 DOCUMENT THE CHANGES TO REQUIREMENTS ........................................................................................................... 150

3.10.4 ANALYZE CHANGE REQUESTS ....................................................................................................................................................... 151

3.11 REFERENCES .......................................................................................................................................152

CHAPTER 4: REQUIREMENTS ELICITATION.....................................................................................................153

4.1 INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................................153

4.1.1 RELATIONSHIPS TO OTHER KNOWLEDGE AREAS ............................................................................................................................ 153

4.2 TASK: ELICIT REQUIREMENTS............................................................................................................155

4.2.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................155

4.2.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 155

4.2.3 KNOWLEDGE..........................................................................................................................................................................................155

4.2.4 SKILLS ..................................................................................................................................................................................................... 155

4.2.5 PREDECESSORS...................................................................................................................................................................................... 155

4.2.6 PROCESS................................................................................................................................................................................................. 156

4.2.7 STAKEHOLDERS ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 157

4.2.8 DELIVERABLES ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 157

4.3 TECHNIQUE: BRAINSTORMING .........................................................................................................157

4.3.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................157

4.3.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 157

4.3.3 INTENDED AUDIENCE ............................................................................................................................................................................ 158

4.3.4 PROCESS................................................................................................................................................................................................. 158

4.3.5 USAGE CONSIDERATIONS....................................................................................................................................................................159

Table of Contents

A Guide to the Business Analysis Body of Knowledge, Release 1.6

©2006, International Institute of Business Analysis

http://www.theiiba.org/

v

4.4 TECHNIQUE: DOCUMENT ANALYSIS .................................................................................................159

4.4.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................159

4.4.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 159

4.4.3 INTENDED AUDIENCE ............................................................................................................................................................................ 159

4.4.4 PROCESS................................................................................................................................................................................................. 160

4.4.5 USAGE CONSIDERATIONS....................................................................................................................................................................160

4.5 TECHNIQUE: FOCUS GROUP ..............................................................................................................160

4.5.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................160

4.5.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 161

4.5.3 INTENDED AUDIENCE ............................................................................................................................................................................ 161

4.5.4 PROCESS................................................................................................................................................................................................. 161

4.5.5 USAGE CONSIDERATIONS....................................................................................................................................................................162

4.6 TECHNIQUE: INTERFACE ANALYSIS .................................................................................................. 163

4.6.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................163

4.6.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 163

4.6.3 INTENDED AUDIENCE ............................................................................................................................................................................ 164

4.6.4 PROCESS................................................................................................................................................................................................. 164

4.6.5 USAGE CONSIDERATIONS....................................................................................................................................................................164

4.7 TECHNIQUE: INTERVIEW....................................................................................................................165

4.7.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................165

4.7.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 165

4.7.3 INTENDED AUDIENCE ............................................................................................................................................................................ 166

4.7.4 PROCESS................................................................................................................................................................................................. 166

4.7.5 USAGE CONSIDERATIONS....................................................................................................................................................................168

4.8 TECHNIQUE: OBSERVATION ..............................................................................................................169

4.8.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................169

4.8.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 169

4.8.3 INTENDED AUDIENCE ............................................................................................................................................................................ 170

4.8.4 PROCESS................................................................................................................................................................................................. 170

4.8.5 USAGE CONSIDERATIONS....................................................................................................................................................................171

4.9 TECHNIQUE: PROTOTYPING ..............................................................................................................171

4.9.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................171

4.9.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 171

4.9.3 INTENDED AUDIENCE ............................................................................................................................................................................ 172

4.9.4 PROCESS................................................................................................................................................................................................. 172

4.9.5 USAGE CONSIDERATIONS....................................................................................................................................................................172

4.10 TECHNIQUE: REQUIREMENTS WORKSHOP .......................................................................................173

4.10.1 PURPOSE...........................................................................................................................................................................................173

4.10.2 DESCRIPTION................................................................................................................................................................................... 173

4.10.3 INTENDED AUDIENCE...................................................................................................................................................................... 174

4.10.4 PROCESS........................................................................................................................................................................................... 174

4.10.5 USAGE CONSIDERATIONS ............................................................................................................................................................. 175

4.11 TECHNIQUE: REVERSE ENGINEERING ...............................................................................................176

4.11.1 PURPOSE...........................................................................................................................................................................................176

4.11.2 DESCRIPTION................................................................................................................................................................................... 176

Table of Contents

A Guide to the Business Analysis Body of Knowledge, Release 1.6

©2006, International Institute of Business Analysis

http://www.theiiba.org/

vi

4.11.3 INTENDED AUDIENCE...................................................................................................................................................................... 177

4.11.4 PROCESS........................................................................................................................................................................................... 177

4.11.5 USAGE CONSIDERATIONS ............................................................................................................................................................. 177

4.12 TECHNIQUE: SURVEY/QUESTIONNAIRE............................................................................................178

4.12.1 PURPOSE...........................................................................................................................................................................................178

4.12.2 DESCRIPTION................................................................................................................................................................................... 178

4.12.3 INTENDED AUDIENCE...................................................................................................................................................................... 178

4.12.4 PROCESS........................................................................................................................................................................................... 179

4.12.5 USAGE CONSIDERATIONS ............................................................................................................................................................. 181

4.13 BIBLIOGRAPHY...................................................................................................................................182

4.14 CONTRIBUTORS.................................................................................................................................. 182

4.14.1 AUTHORS ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 182

CHAPTER 5: REQUIREMENTS ANALYSIS AND DOCUMENTATION.................................................................183

5.1 INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................................183

5.1.1 KNOWLEDGE AREA DEFINITION AND SCOPE .................................................................................................................................. 183

5.1.2 INPUTS..................................................................................................................................................................................................... 183

5.1.3 TASKS ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 184

5.1.4 OUTPUTS ................................................................................................................................................................................................184

5.1.5 ANALYSIS TECHNIQUES AND SOLUTION DEVELOPMENT METHODOLOGIES ............................................................................ 185

5.1.6 SIGNIFICANT CHANGES FROM VERSION 1.4.................................................................................................................................... 186

5.2 TASK: STRUCTURE REQUIREMENTS PACKAGES ...............................................................................187

5.2.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................187

5.2.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 187

5.2.3 PREDECESSORS...................................................................................................................................................................................... 187

5.2.4 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................... 188

5.2.5 STAKEHOLDERS ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 191

5.2.6 DELIVERABLES ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 191

5.3 TASK: CREATE BUSINESS DOMAIN MODEL ......................................................................................191

5.3.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................191

5.3.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 192

5.3.3 PREDECESSORS...................................................................................................................................................................................... 192

5.3.4 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................... 192

5.3.5 STAKEHOLDERS ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 193

5.3.6 DELIVERABLES ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 193

5.4 TASK: ANALYZE USER REQUIREMENTS ............................................................................................193

5.5 TASK: ANALYZE FUNCTIONAL REQUIREMENTS ...............................................................................193

5.5.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................193

5.5.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 193

5.5.3 PREDECESSORS...................................................................................................................................................................................... 193

5.5.4 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................... 193

5.5.5 STAKEHOLDERS ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 197

5.5.6 DELIVERABLES ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 198

5.6 TASK: ANALYZE QUALITY OF SERVICE REQUIREMENTS ..................................................................198

5.6.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................198

Table of Contents

A Guide to the Business Analysis Body of Knowledge, Release 1.6

©2006, International Institute of Business Analysis

http://www.theiiba.org/

vii

5.6.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 198

5.6.3 PREDECESSORS...................................................................................................................................................................................... 198

5.6.4 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................... 198

5.6.5 STAKEHOLDERS ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 201

5.6.6 DELIVERABLES ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 201

5.7 TASK: DETERMINE ASSUMPTIONS AND CONSTRAINTS ..................................................................201

5.7.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................201

5.7.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 201

5.7.3 PREDECESSORS...................................................................................................................................................................................... 202

5.7.4 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................... 202

5.7.5 STAKEHOLDERS ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 202

5.7.6 DELIVERABLES ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 203

5.8 TASK: DETERMINE REQUIREMENTS ATTRIBUTES ............................................................................203

5.8.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................203

5.8.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 203

5.8.3 PREDECESSORS...................................................................................................................................................................................... 203

5.8.4 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................... 203

5.8.5 STAKEHOLDERS ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 205

5.8.6 DELIVERABLES ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 205

5.9 TASK: DOCUMENT REQUIREMENTS ..................................................................................................205

5.9.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................205

5.9.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 205

5.9.3 PREDECESSORS...................................................................................................................................................................................... 205

5.9.4 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................... 205

5.9.5 STAKEHOLDERS ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 207

5.9.6 DELIVERABLES ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 207

5.10 TASK: VALIDATE REQUIREMENTS .....................................................................................................207

5.10.1 PURPOSE...........................................................................................................................................................................................207

5.10.2 DESCRIPTION................................................................................................................................................................................... 207

5.11 TASK: VERIFY REQUIREMENTS ..........................................................................................................207

5.11.1 PURPOSE...........................................................................................................................................................................................207

5.11.2 DESCRIPTION................................................................................................................................................................................... 207

5.11.3 PREDECESSORS................................................................................................................................................................................ 208

5.11.4 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS.............................................................................................................................................................. 208

5.11.5 STAKEHOLDERS ............................................................................................................................................................................... 211

5.11.6 DELIVERABLES .................................................................................................................................................................................211

5.12 TECHNIQUE: DATA AND BEHAVIOR MODELS...................................................................................211

5.12.1 BUSINESS RULES.............................................................................................................................................................................. 211

5.12.2 CLASS MODEL ................................................................................................................................................................................ 214

5.12.3 CRUD MATRIX ............................................................................................................................................................................... 215

5.12.4 DATA DICTIONARY ........................................................................................................................................................................ 217

5.12.5 DATA TRANSFORMATION AND MAPPING .................................................................................................................................. 220

5.12.6 ENTITY RELATIONSHIP DIAGRAMS............................................................................................................................................... 223

5.12.7 METADATA DEFINITION ................................................................................................................................................................ 227

5.13 TECHNIQUE: PROCESS/FLOW MODELS.............................................................................................228

Table of Contents

A Guide to the Business Analysis Body of Knowledge, Release 1.6

©2006, International Institute of Business Analysis

http://www.theiiba.org/

viii

5.13.1 ACTIVITY DIAGRAM ........................................................................................................................................................................ 228

5.13.2 DATA FLOW DIAGRAM.................................................................................................................................................................231

5.13.3 EVENT IDENTIFICATION .................................................................................................................................................................. 234

5.13.4 FLOWCHART.................................................................................................................................................................................... 235

5.13.5 SEQUENCE DIAGRAM.....................................................................................................................................................................239

5.13.6 STATE MACHINE DIAGRAM ..........................................................................................................................................................241

5.13.7 WORKFLOW MODELS.................................................................................................................................................................... 242

5.14 TECHNIQUE: USAGE MODELS............................................................................................................244

5.14.1 PROTOTYPING.................................................................................................................................................................................. 244

5.14.2 STORYBOARDS/SCREEN FLOWS .................................................................................................................................................. 247

5.14.3 USE CASE DESCRIPTION ...............................................................................................................................................................250

5.14.4 USE CASE DIAGRAM ...................................................................................................................................................................... 253

5.14.5 USER INTERFACE DESIGNS ............................................................................................................................................................257

5.14.6 USER PROFILES................................................................................................................................................................................ 259

5.14.7 USER STORIES.................................................................................................................................................................................. 261

5.15 ISSUE AND TASK LIST.........................................................................................................................264

5.16 REFERENCES .......................................................................................................................................265

CHAPTER 6: REQUIREMENTS COMMUNICATION

6.1 INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................................269

6.1.1 KNOWLEDGE AREA DEFINITION ..........................................................................................................................................................269

6.1.2 RATIONALE FOR INCLUSION ...............................................................................................................................................................269

6.1.3 KNOWLEDGE AREA TASKS.................................................................................................................................................................... 269

6.1.4 RELATIONSHIP TO OTHER KNOWLEDGE AREAS................................................................................................................................ 270

6.2 TASK: CREATE A REQUIREMENTS COMMUNICATION PLAN ............................................................271

6.2.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................271

6.2.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 271

6.2.3 PREDECESSORS...................................................................................................................................................................................... 271

6.2.4 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................... 271

6.2.5 STAKEHOLDERS ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 273

6.2.6 DELIVERABLES ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 273

6.3 TASK: MANAGE REQUIREMENTS CONFLICTS ................................................................................... 273

6.3.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................273

6.3.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 273

6.3.3 PREDECESSORS...................................................................................................................................................................................... 274

6.3.4 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................... 274

6.3.5 STAKEHOLDERS ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 274

6.3.6 DELIVERABLES ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 274

6.4 TASK: DETERMINE APPROPRIATE REQUIREMENTS FORMAT .......................................................... 274

6.4.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................274

6.4.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 274

6.4.3 PREDECESSORS...................................................................................................................................................................................... 275

6.4.4 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................... 276

6.4.5 STAKEHOLDERS ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 280

6.4.6 DELIVERABLES ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 281

6.5 TASK: CREATE A REQUIREMENTS PACKAGE.....................................................................................281

Table of Contents

A Guide to the Business Analysis Body of Knowledge, Release 1.6

©2006, International Institute of Business Analysis

http://www.theiiba.org/

ix

6.5.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................281

6.5.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 281

6.5.3 PREDECESSORS...................................................................................................................................................................................... 281

6.5.4 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................... 282

6.5.5 STAKEHOLDERS ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 285

6.5.6 DELIVERABLES ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 286

6.6 TASK: CONDUCT A REQUIREMENTS PRESENTATION.......................................................................286

6.6.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................286

6.6.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 286

6.6.3 PREDECESSORS...................................................................................................................................................................................... 287

6.6.4 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................... 287

6.6.5 STAKEHOLDERS ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 288

6.6.6 DELIVERABLES ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 288

6.7 TASK: CONDUCT A FORMAL REQUIREMENTS REVIEW.....................................................................289

6.7.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................289

6.7.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 290

6.7.3 PREDECESSORS...................................................................................................................................................................................... 290

6.7.4 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................... 291

6.7.5 STAKEHOLDERS ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 294

6.7.6 DELIVERABLES ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 295

6.8 TASK: OBTAIN REQUIREMENTS SIGNOFF .........................................................................................295

6.8.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................295

6.8.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 295

6.8.3 PREDECESSORS...................................................................................................................................................................................... 295

6.8.4 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................... 295

6.8.5 STAKEHOLDERS ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 296

6.8.6 DELIVERABLES ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 296

6.9 REFERENCES .......................................................................................................................................296

CHAPTER 7: SOLUTION ASSESSMENT AND VALIDATION..............................................................................297

7.1 INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................................297

7.1.1 KNOWLEDGE AREA DEFINITION......................................................................................................................................................... 297

7.1.2 RATIONALE FOR INCLUSION ............................................................................................................................................................... 297

7.1.3 KNOWLEDGE AREA TASKS...................................................................................................................................................................298

7.1.4 RELATIONSHIP TO OTHER KNOWLEDGE AREAS............................................................................................................................... 298

7.2 DEVELOP ALTERNATE SOLUTIONS ...................................................................................................299

7.2.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................299

7.2.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 307

7.2.3 PREDECESSORS...................................................................................................................................................................................... 307

7.2.4 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................... 307

7.2.5 STAKEHOLDERS ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 307

7.2.6 DELIVERABLES ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 307

7.3 EVALUATE TECHNOLOGY OPTIONS..................................................................................................307

7.3.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................307

7.3.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 307

7.3.3 PREDECESSORS...................................................................................................................................................................................... 307

Table of Contents

A Guide to the Business Analysis Body of Knowledge, Release 1.6

©2006, International Institute of Business Analysis

http://www.theiiba.org/

x

7.3.4 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................... 308

7.3.5 STAKEHOLDERS ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 308

7.3.6 DELIVERABLES ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 308

7.4 FACILITATE THE SELECTION OF A SOLUTION...................................................................................308

7.4.1 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................................................................................308

7.4.2 DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 309

7.4.3 PREDECESSORS...................................................................................................................................................................................... 309

7.4.4 PROCESS AND ELEMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................... 309