Modernizing

the Postal

Money Order

RARC Report

Report Number

RARC-WP-16-007

April 4, 2016

Cover

Executive Summary

Table of Contents

Observations

Appendices

Print

Executive

Summary

The Post Ofce Department introduced money orders during

the Civil War as a safe way for Union soldiers to send money

home to their families. A century-and-a-half later, postal money

orders remain essential to the lives of millions of Americans

who use them to make $21 billion worth of payments annually.

Money orders are essentially prepaid checks. But in the wake

of alternatives from other providers and broad shifts toward

electronic forms of payment, the number of postal money orders

sold has fallen by 60 percent from their peak in 2000. Meanwhile,

other providers of money orders appear to be faring better.

Between 2011 and 2013, the number of non-postal money orders

actually increased slightly, while postal money order volumes

declined by 11 percent.

To better meet the needs of those who purchase money orders

and the businesses that accept them as a form of payment —

saving them time and money — postal money orders could

be modernized. The Postal Service also would benet from

a rejuvenated money order business, which is strategically

important on many levels.

First, money orders are a key driver of foot trafc to post ofces,

with one in 10 retail revenue transactions nationally containing a

money order. Among the 1,000 locations with the highest money

order volume, a quarter of transactions include a money order.

In addition, money orders are one of the Postal Service’s more

protable products, with an average prot margin of 35 percent.

Highlights

Postal money orders were introduced in 1864

as a safe way for soldiers and others to send

payments over long distances.

Post ofces sold $21 billion worth of money

orders in scal year 2015, generating

$159 million in revenue.

Nationally, one in 10 postal retail revenue

transactions include a money order.

In the wake of alternatives from other providers

and broad shifts toward electronic forms of

payment, money order sales have plunged

60 percent from their peak in 2000.

About 1,200 high volume post ofces grew

money order sales by at least 10 percent in the

past 3 years, showing that improving sales is

achievable.

Selling money orders through digital channels

could have signicant benets for money order

customers.

The Postal Service could assign a strategic

manager to help modernize and stabilize this

important product.

Modernizing the Postal Money Order

Report Number RARC-WP-16-007

1

Executive Summary

Table of Contents

Observations

Appendices

Print

Because customers often mail them, money orders also

potentially generate tens of millions of dollars in annual postage

revenue for the Postal Service. Furthermore, there is a lag

between the time when a money order is purchased and when

it is redeemed. These funds give the Postal Service signicant

cash ow

exibility. As the postal money order business shrinks,

all of these benets decline with it.

There is good reason to think that the Postal Service could

improve upon its money order business. While overall sales

declines paint a stark picture, a closer examination reveals that

the top 25 percent of post ofces for money orders — which

account for 77 percent of all money order fees — had stable

sales over the past 3 years, with sales dipping just 1 percent.

Among these high volume locations, about 1,200 actually grew

their money order sales by at least 10 percent — demonstrating

that increasing money order sales is achievable. But to get

there, money orders could benet from a product manager

to share best practices and focus on strategic growth —

something the business now lacks.

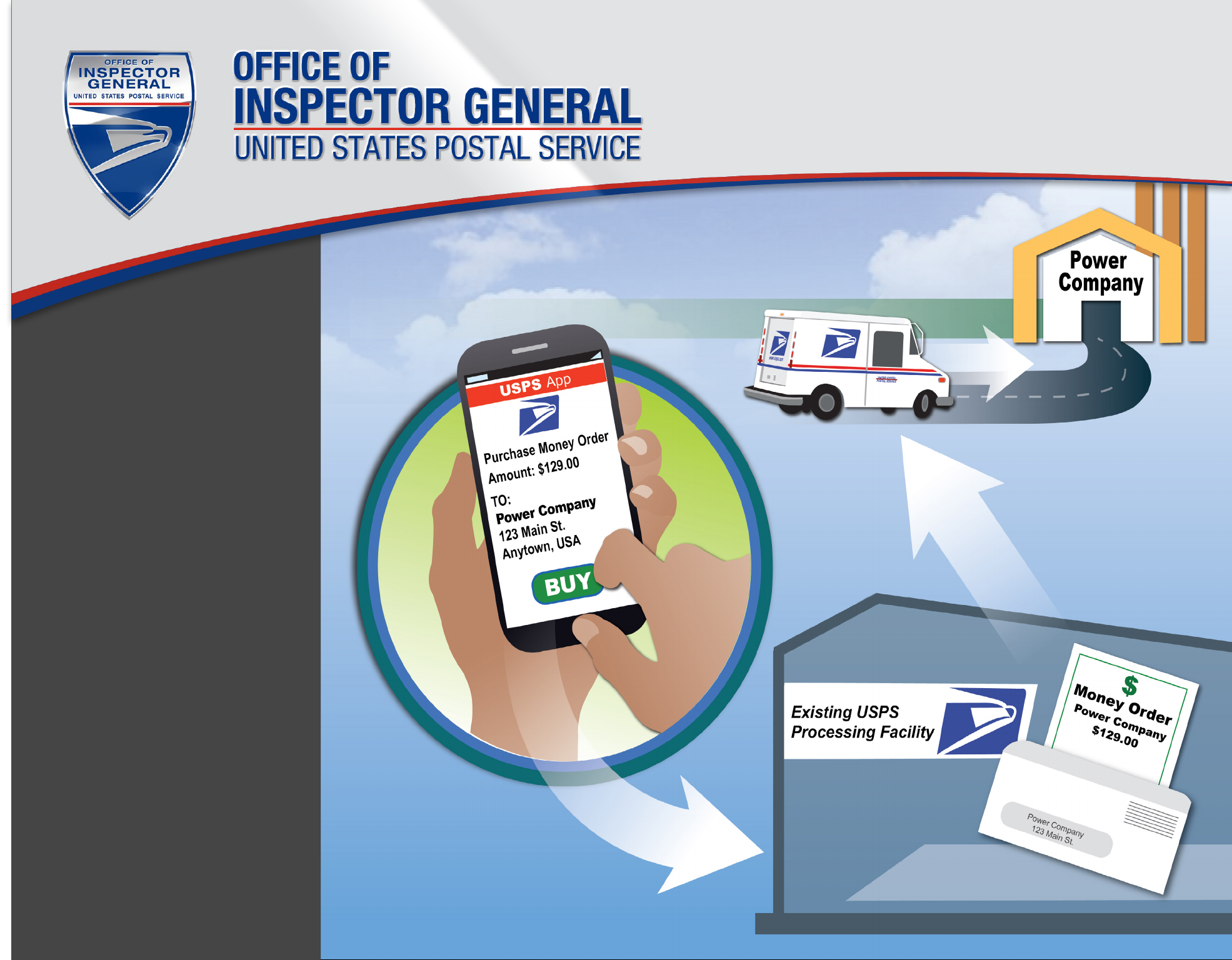

The U.S. Postal Service Ofce of Inspector General (OIG) has

identied some retail best practices that the Postal Service

could follow, particularly at high volume money order locations.

It also could begin selling paper money orders through digital

channels, such as usps.com and the USPS Mobile app. This

innovation, which would likely not require regulatory approval,

could save users a signicant amount of time. Additionally,

money orders sold through digital channels and printed at a

central facility could be more protable and generate more mail

volume than money orders sold at post ofces.

To truly bring the product into the digital age, the Postal Service

also could introduce a fully-electronic money order, as many

foreign posts have done. Customers could use such a product

to pay bills, make person-to-person payments, or make

ecommerce purchases. In addition, electronic money orders

could have signicant appeal for online merchants, reducing

their payment processing costs. While this innovation would

likely be allowable under current law, it would require Postal

Regulatory Commission approval.

While postal money order sales are in decline, there is an

opportunity to alter that trend. Postal money orders have some

unique advantages to customers such as security, availability,

and ease of redemption. The Postal Service could make

a number of strategic enhancements to build upon these

strengths. In addition, it could modernize both the way it sells

money orders and the money order product itself, which could

attract the next generation of customers. Given the pace of

current declines, time is of the essence. If the Postal Service

waits to take action to stabilize and modernize this important

product, fewer money order users and recipients will be left to

benet from those changes.

Modernizing the Postal Money Order

Report Number RARC-WP-16-007

2

Executive Summary

Table of Contents

Observations

Appendices

Print

Table of Contents

Executive Summary......................................................................................1

Observations ................................................................................................5

Introduction ..............................................................................................5

Money Orders Bring Many Benets .......................................................5

Money Orders Are a Key Driver of Retail Foot Trafc ........................6

Money Orders Have Anti-Fraud Security Features ...........................6

The Decline in Money Order Sales Has Been Uneven Across

the Network .............................................................................................7

There Are Other Providers of Money Orders ...........................................8

Many View Postal Money Orders as a Premium Product ...............10

Most Payments Are Going Electronic. Money Orders Could Too. ... 11

A Look at Money Order Users ...............................................................12

Heavy Users Comprise Three-Fourths of Postal Money

Order Purchases ..............................................................................12

Money Order Users Are Demographically Diverse ..........................13

Best Practices for Money Order Sales ..................................................15

A Stand-Out Post Ofce: Frederick Douglass Station ......................15

Suggestions for Improving Service and Enhancing Revenue ...............16

Assign a National Product Manager to Strategically Guide the

Money Order Business .....................................................................16

Consider Potential Modernizations for Money Orders .....................16

Optimize the Retail Experience at High Volume Money

Order Ofces ....................................................................................18

Communicate the Existence of Postal Money Orders as Well

as the Advantages of Postal Money Orders and

Any Product Changes ......................................................................19

Perhaps Pursue Money Order Discount Agreements With

Prepaid Card Companies .................................................................19

Ramp up Additional Alternative Financial Services Offerings ..........19

Conclusion .............................................................................................20

Modernizing the Postal Money Order

Report Number RARC-WP-16-007

3

Executive Summary

Table of Contents

Observations

Appendices

Print

Table of Contents

Management’s Comments ....................................................................20

Evaluation of Management’s Comments ...............................................20

Appendices .................................................................................................22

Appendix A: Statistical Methodology for Underperforming

Post Ofce Analysis ...............................................................................23

Appendix B: Estimating the Postal Service’s Share of

Money Orders Sold ..............................................................................25

Appendix C: A Closer Look at Money Order Users ...............................27

Appendix D: Financial Impact of Active Management and

Digital Channels for Paper Money Orders .............................................31

Appendix E: Management’s Comments ................................................37

Contact Information ....................................................................................39

Modernizing the Postal Money Order

Report Number RARC-WP-16-007

4

Executive Summary

Table of Contents

Observations

Appendices

Print

Observations

Introduction

Until the mid-19th century, sending money through the mail was a risky proposition. Each year, thieves stole as much as

$1 million in cash from the mail — some of it from Union soldiers ghting in the Civil War.

1

In 1864, the United States government

came up with a solution: postal money orders. For a nominal fee, Americans could purchase a money order from their local post

ofce and use it as a guaranteed payment they could send safely through the mail. The product caught on. By 1890, the total

value of postal money orders issued topped $110 million a year ($2.9 billion in today’s dollars).

2

More than a century later, millions

of American families still rely on postal money orders as a convenient, reliable way to pay their bills, purchasing about $21 billion in

face value per year.

3

Money orders also drive signicant foot trafc to post ofces, are frequently mailed, and are one of the

U.S. Postal Service’s more protable products.

But the money order business is in trouble. In the wake of alternatives from other

providers and broad shifts toward electronic forms of payment, the number of

postal money orders sold each year has plunged from 233 million in 2000 to

93 million in 2015 — a 60 percent drop. To put that into perspective, First-Class

Mail has fallen 39 percent over the same period. When it comes to the money

order business, the Postal Service appears to prioritize managing the day-to-day

operations over strategizing about how to improve or build upon it. This white

paper is an attempt to encourage and aid such strategic discussions, which we

believe could lead to signicant benets for the millions of Americans who use

money orders, many of them on a regular basis, and for the Postal Service itself.

Money Orders Bring Many Benets

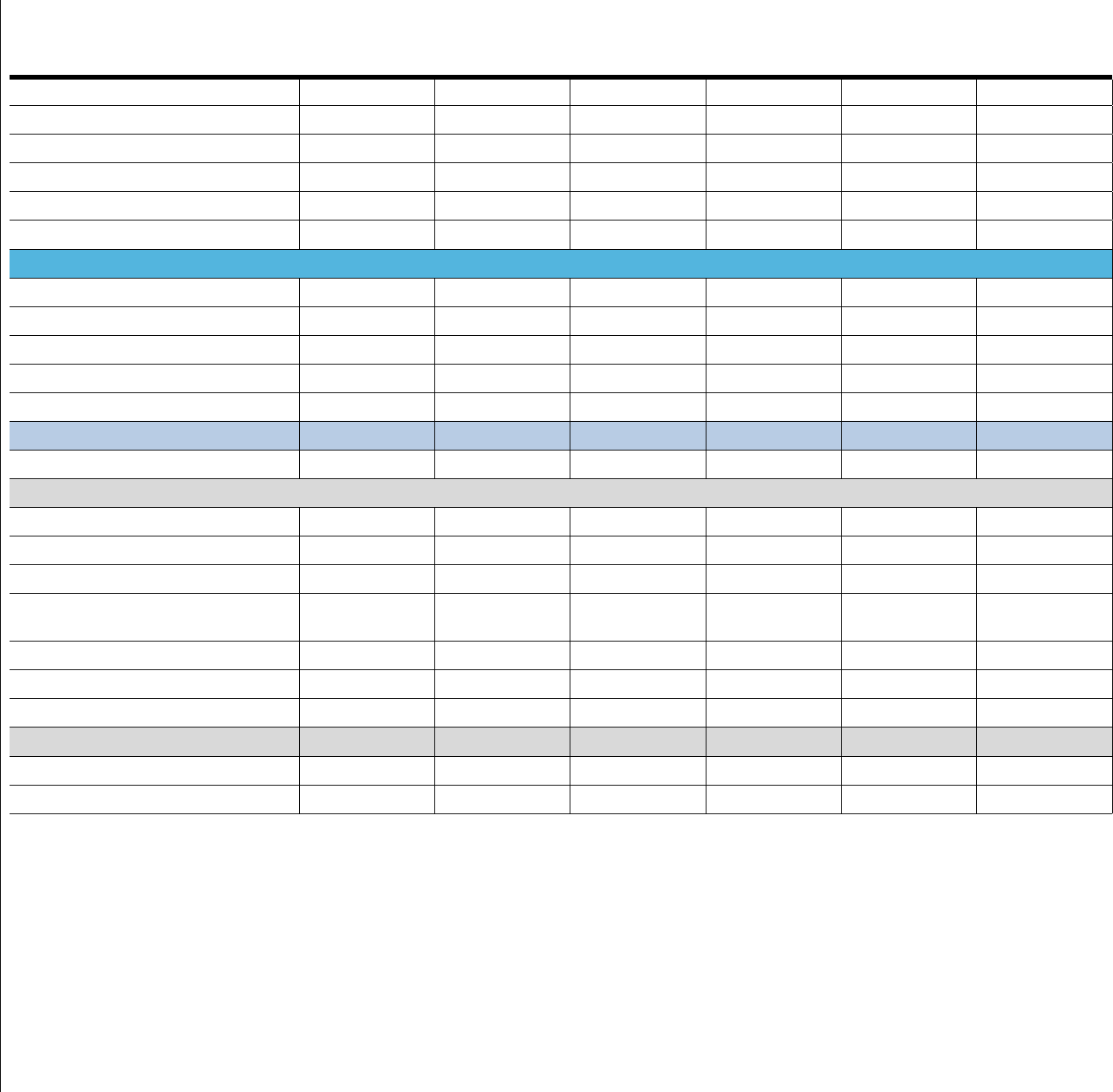

Money orders are among the Postal Service’s more protable products.

They brought in $159 million in revenue and $54 million in prot (known as

“contribution” in postal terms) during scal year (FY) 2015.

4

Over the past 3

years, it has been the fth most protable among postal products that generate

at least $100 million in revenue, as shown in Figure 1. Money orders also are

often sent through the mail, potentially generating tens of millions in additional

postage revenue.

5

The $600 million to $700 million outstanding balance of money orders that have been purchased, but not yet

redeemed, also gives the Postal Service signicant cash ow exibility — particularly during these times of tight budgets.

6

The

Postal Service invests those funds, generating $2 million in interest income, known as “oat,” in FY 2015.

7

1 National Postal Museum, Development and Operation of the Domestic Money Order System, by Terence M. Hines and Thomas Velk, 2011, http://postalmuseum.si.edu/

Symposium2011/papers/Hines_velk_2011_stamps.pdf, pp. 2-4.

2 Ibid.

3 There were $21 billion in face value money orders sold in scal year (FY) 2015.

4 Revenue gure comes from Postal Service’s Market Dominant Billing Determinants, Special Services, http://www.prc.gov/dockets/document/94395. Cost information

comes from the Postal Service Public Cost and Revenue Analysis report, http://www.prc.gov/dockets/document/94410. Prot, or “contribution,” is the difference between

revenue and costs for a given product. A portion of the revenue from money orders comes from “escheatment,” which is the face value of money orders that have gone

unredeemed for 2 years — a policy that is explained here: U.S. Postal Service Ofce of Inspector General, Controls to Detect Money Order Fraud, Report No.

DP-AR-13-002, February 7, 2013, https://www.uspsoig.gov/sites/default/les/document-library-les/2015/dp-ar-13-002.pdf, p. 9.

5 The Postal Service’s Household Diary study names money orders as one of the most common First Class Mail pieces, but does not give gures. In OIG interviews with

50 postal money order users, 68 percent said they mail some or all of the money orders they buy. U.S. Postal Service, The Household Diary Study: Mail Use & Attitudes

in FY 2014, August 20, 2015, http://www.prc.gov/docs/93/93171/2014%20USPS%20HDS%20Annual%20Report_Final_V3.pdf, p. 5.

6 This averaged $666 million in FY 2015. U.S. Postal Service, “USPS-FY15-28 - FY 2015 Special Cost Studies Workpapers - Special Services (Public Portion),” Postal

Regulatory Commission Docket No. ACR2015, December 29, 2015, http://www.prc.gov/dockets/document/94343.

7 Ibid.

The Post Ofce Department

introduced money orders in

1864 as a safe way to send

payments over long distances.

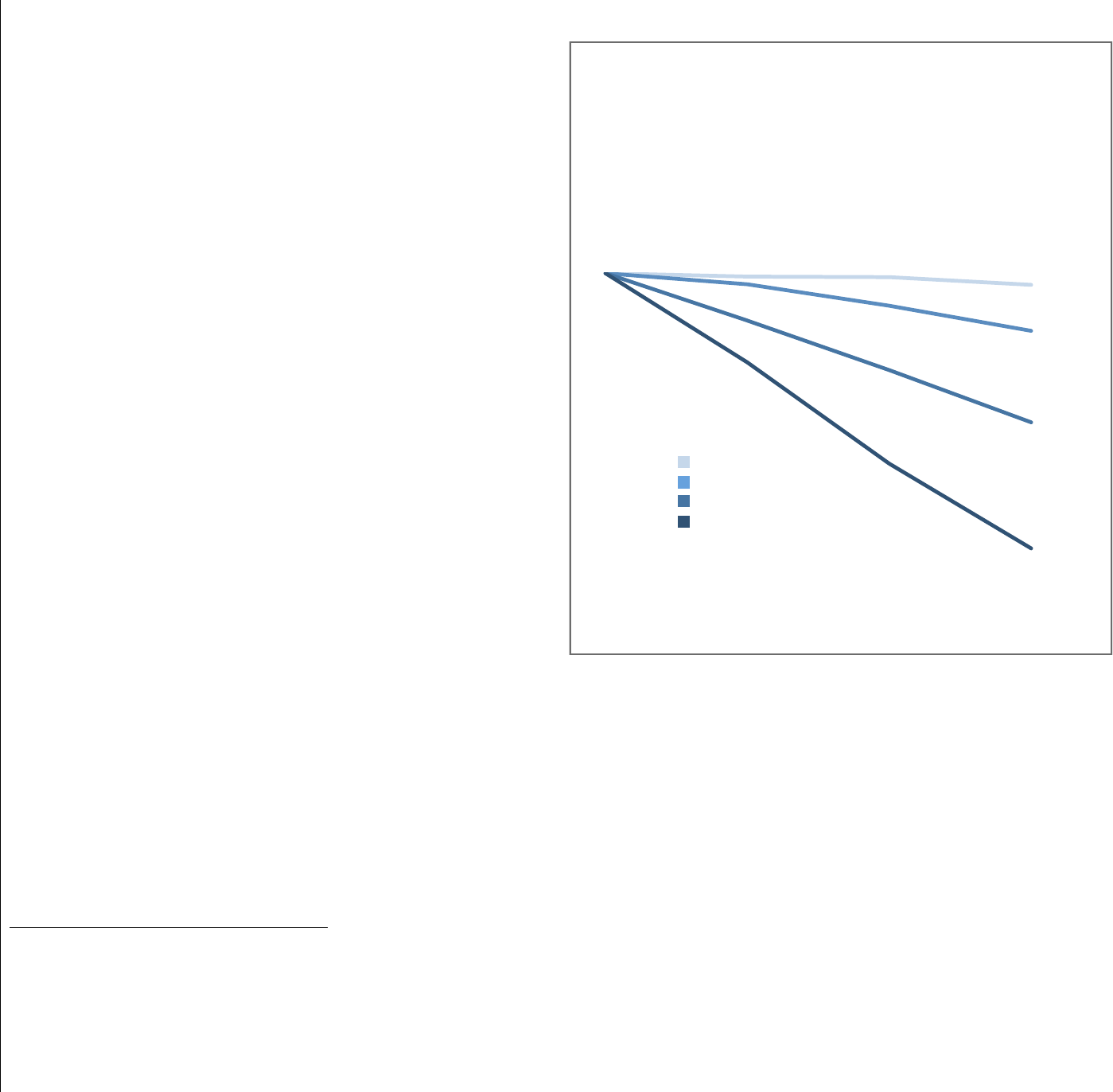

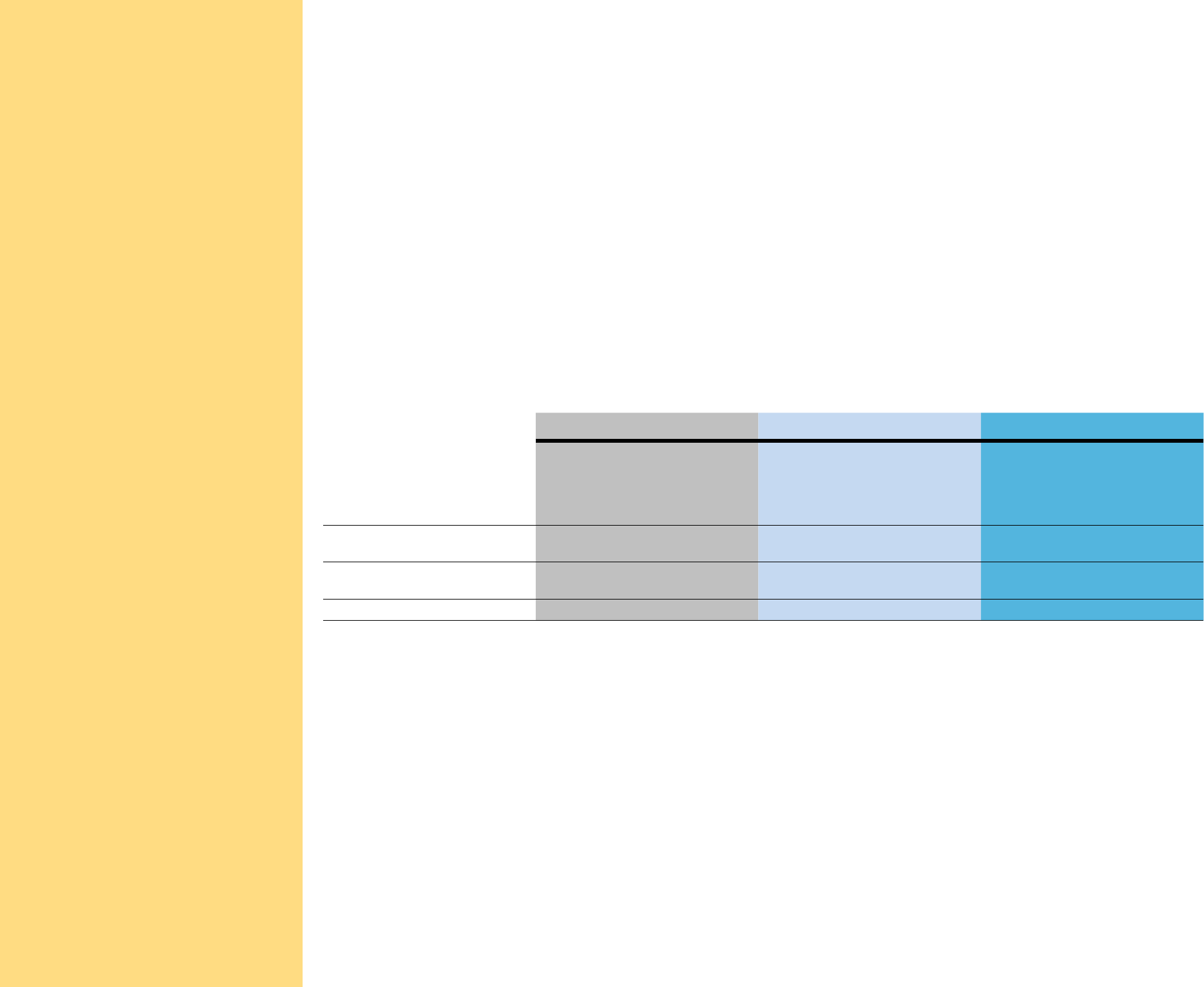

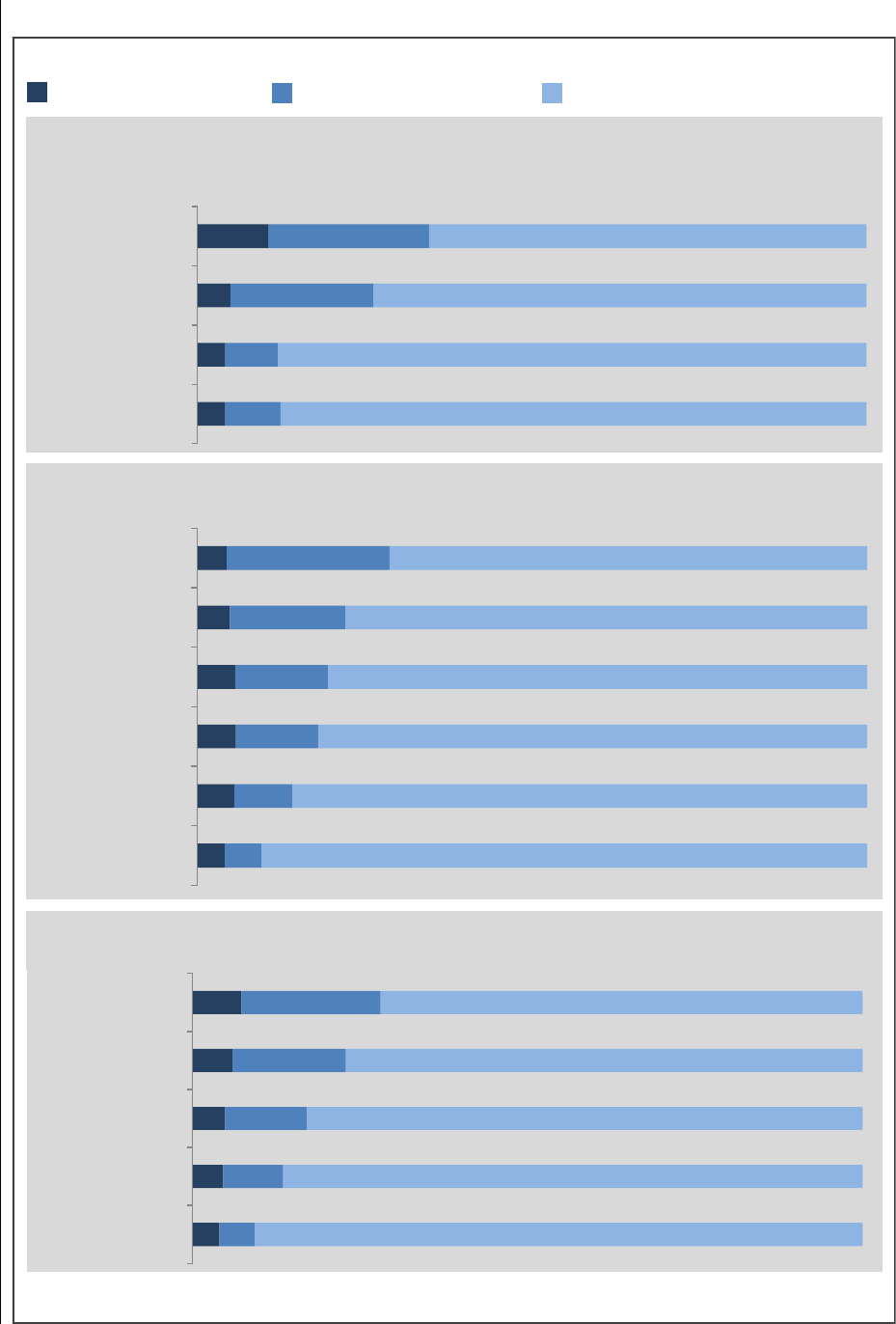

Figure 1: Money Order Protability

MONEY ORDERS EARN STRONG PROFITS

Among products with at least $100 million in revenue,

money orders are among the more profitable. If

postage from mailed money orders and the “float”

earned by investing the funds from outstanding money

orders were included, profits would be even higher.

†

Cost coverage is revenue as a percentage of attributable costs.

*Average excludes 2013, which was unavailable.

Source: U.S. Postal Service Cost and Revenue Analysis reports.

Average cost coverage in fiscal years 2013-2015

†

204%

165%

162%

157%

132%

131%

130%

123%

106%

76%

First-Class Mail

Priority Mail Express

Competitive International*

Standard Mail

Money Orders

Certified Mail

Ground

Priority Mail

First Class Packages

Package Services

Periodicals

220%

Modernizing the Postal Money Order

Report Number RARC-WP-16-007

5

Executive Summary

Table of Contents

Observations

Appendices

Print

Money Orders Are a Key Driver of Retail Foot Trafc

Money orders also are one of the biggest drivers of foot trafc to post ofces, where 10 percent of all revenue transactions in

FY 2015 included a money order.

8

Among the 1,000 locations with the highest money order volume, a quarter of transactions

included a money order. In some high volume ofces, money orders were present in more than half of all transactions. On top

of that, money order customers often buy additional items when they come to the post ofce. Nearly half of all money order

transactions in 2015 — 28 million in total — also included other postal products.

9

In addition, money order retail sales have been

relatively more stable than that of other retail products. Overall post ofce walk-in revenue declined 40 percent faster during the

past 3 years than money order fee revenue.

10

All of this suggests that money orders could be strategically important to the success

of the Postal Service’s retail network.

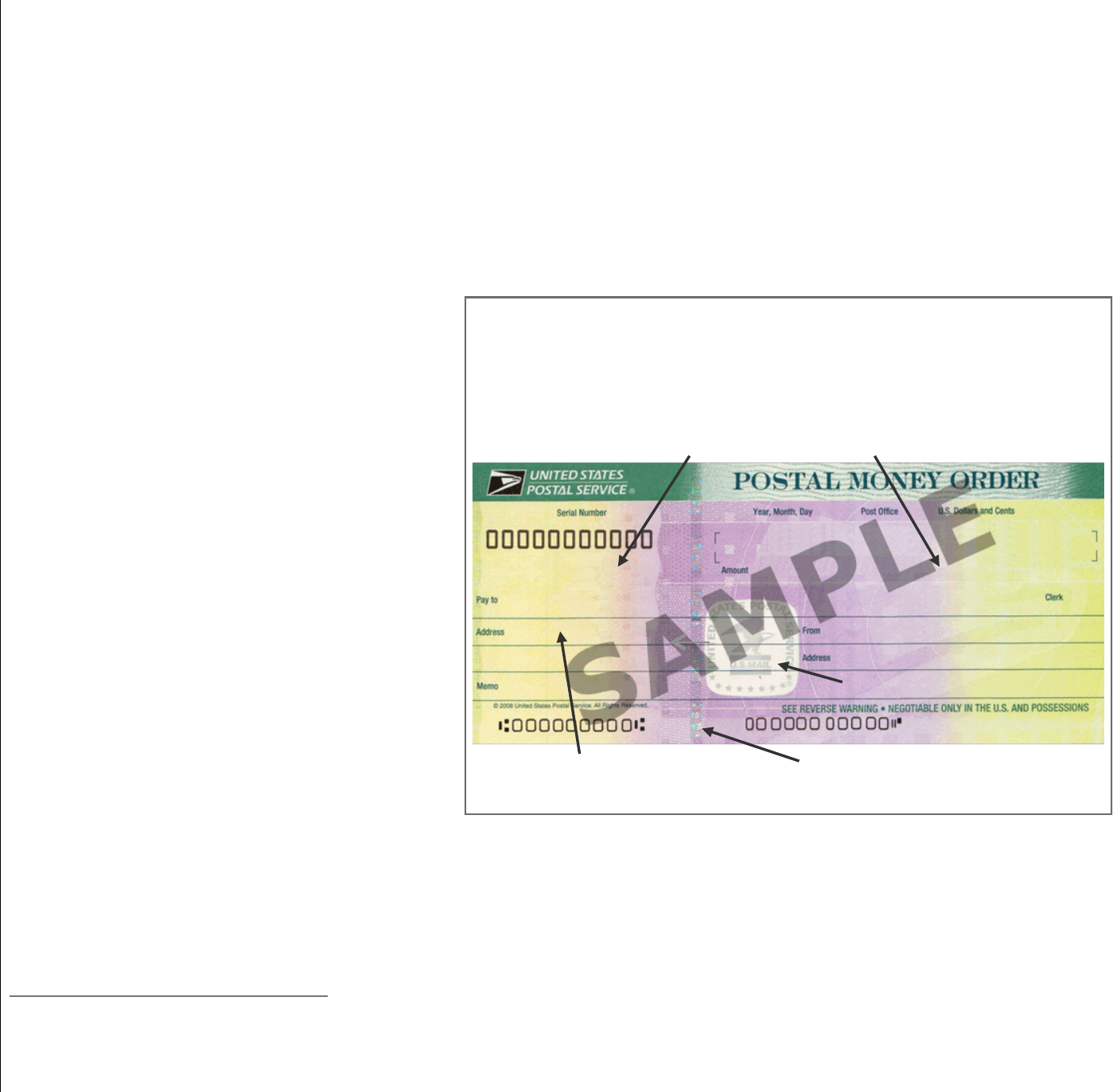

Money Orders Have Anti-Fraud Security

Features

Postal money orders are prepaid and come with

strong security features that make them difcult

to counterfeit, as shown in Figure 2. The color

gradient, watermark, and holographic strip all

work to minimize fraud. Another advantage for

the Postal Service in this arena is its two law

enforcement arms: the Postal Inspection Service,

which investigates external crimes, and the Ofce

of Inspector General (OIG), which investigates

misdeeds by postal employees. Internal fraud

tends to happen at small post ofces that lack

automated point-of-sale terminals. Among cases

the OIG has closed over the past 5 years, these

scams resulted in an average of about

$1 million per year in theft, though the

Postal Service recovers the vast majority of that

money.

11

The losses due to fraud are minuscule

relative to the billions of dollars that ow through

postal money orders every year. This is a sign of

the effectiveness of fraud mitigation strategies and

of a well-functioning product.

8 OIG analysis of 2015 data from the Postal Service Retail Data Mart. This is for the approximately 18,000 post ofces that have POS or RSS-type point-of-sale terminals,

which account for 94 percent of all post ofce walk-in revenue. Other locations use non-computerized terminals that do not collect transaction-level data.

9 Ibid. Many customers buy multiple money orders per transaction.

10 OIG analysis of data from the Postal Service Accounting Data Mart.

11 Based on interview of OIG nancial fraud investigators.

Nationally, one in 10 retail

revenue transactions include

money orders, which are a key

driver of foot trafc to

post ofces.

Figure 2: Postal Money Orders’ Security Features

POSTAL MONEY ORDERS’ SECURITY FEATURES

Postal money orders are printed on textured, currency-like paper and

packed with security features that make them difficult to counterfeit.

COLOR GRADIENTS

BEN FRANKLIN

WATERMARK

U.S. MAIL EAGLE EMBLEM

HOLOGRAPHIC

STRIP

Modernizing the Postal Money Order

Report Number RARC-WP-16-007

6

Executive Summary

Table of Contents

Observations

Appendices

Print

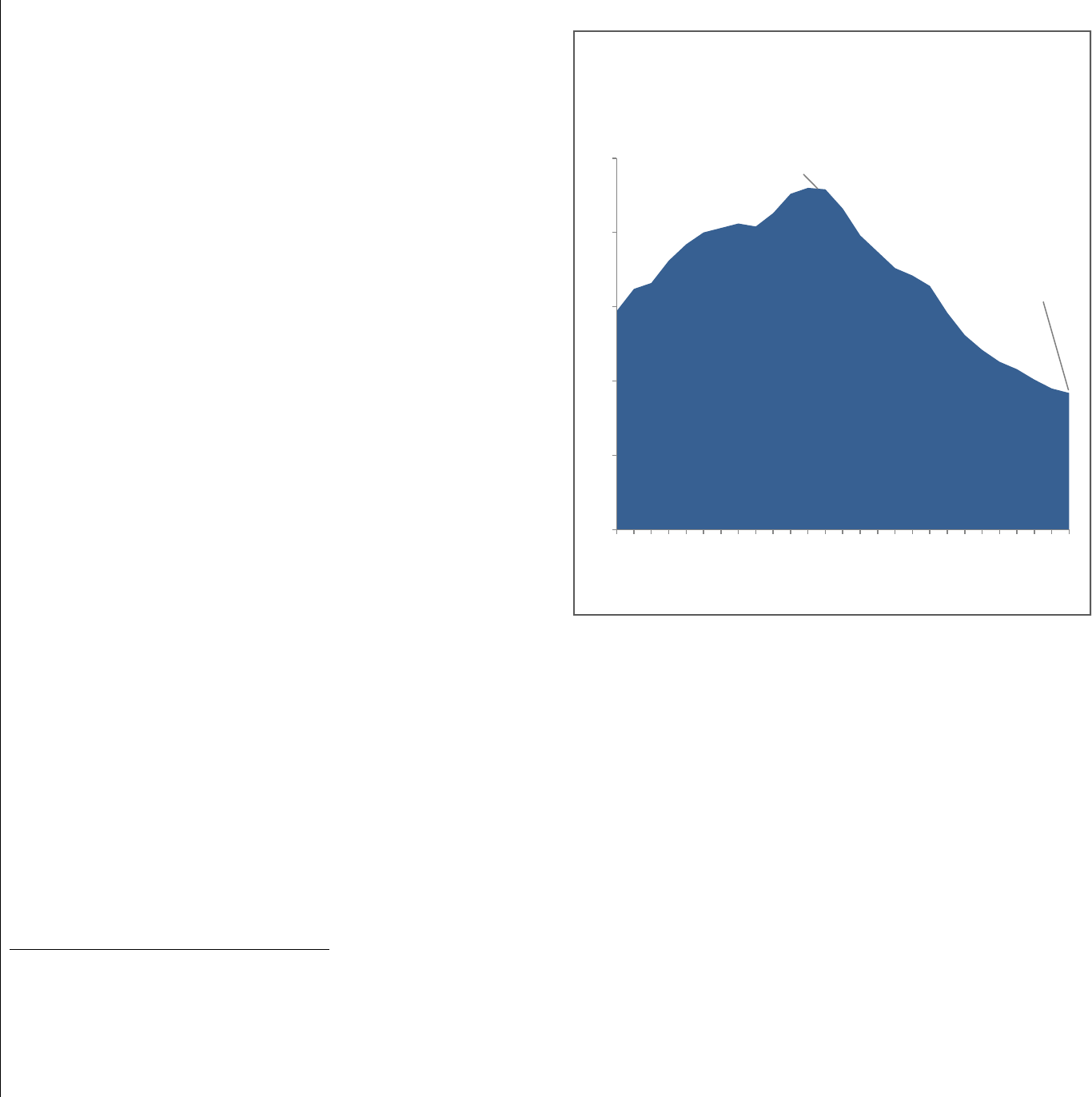

The Decline in Money Order Sales Has Been

Uneven Across the Network

As Figure 3 illustrates, overall postal money order use

has plunged over the past decade and a half. Much of this

reects the broad shift away from checks and money orders

toward electronic forms of payment, particularly for bills and

ecommerce.

12

Money order revenue has fallen at about half the

rate as the number of money orders sold, thanks to growth in

the average size of money orders purchased and modest

price increases.

13

While the overall decline paints a dismal picture, a closer

examination reveals a more nuanced portrait. Dividing post

ofces into quartiles based on money order fee revenue shows

that the top quartile — which accounts for 77 percent of all

money order fees — saw stable sales between 2012 and 2015

with money order fee revenue falling just 1 percent.

14

Among

these high volume locations, about 1,200 post ofces actually

grew their money order sales by at least 10 percent. At the

same time, post ofces in the two lowest quartiles — which

accounted for just 6 percent of money order fees — saw sales

dive by 17 percent and 32 percent respectively over the same

period, as is illustrated in Figure 4.

In an effort to pin down the reasons for the stark differences in

the trajectory of money order sales, the OIG examined three external factors that help predict money order sales at a given post

ofce: population, economic conditions, and the general level of education in the surrounding area.

15

The OIG also controlled for

two internal factors: post ofce walk-in revenue and whether the location was a part of the Post Ofce Structure Plan, or POSt

Plan, an initiative to cut costs by signicantly scaling back hours at about 13,000 rural post ofces.

16

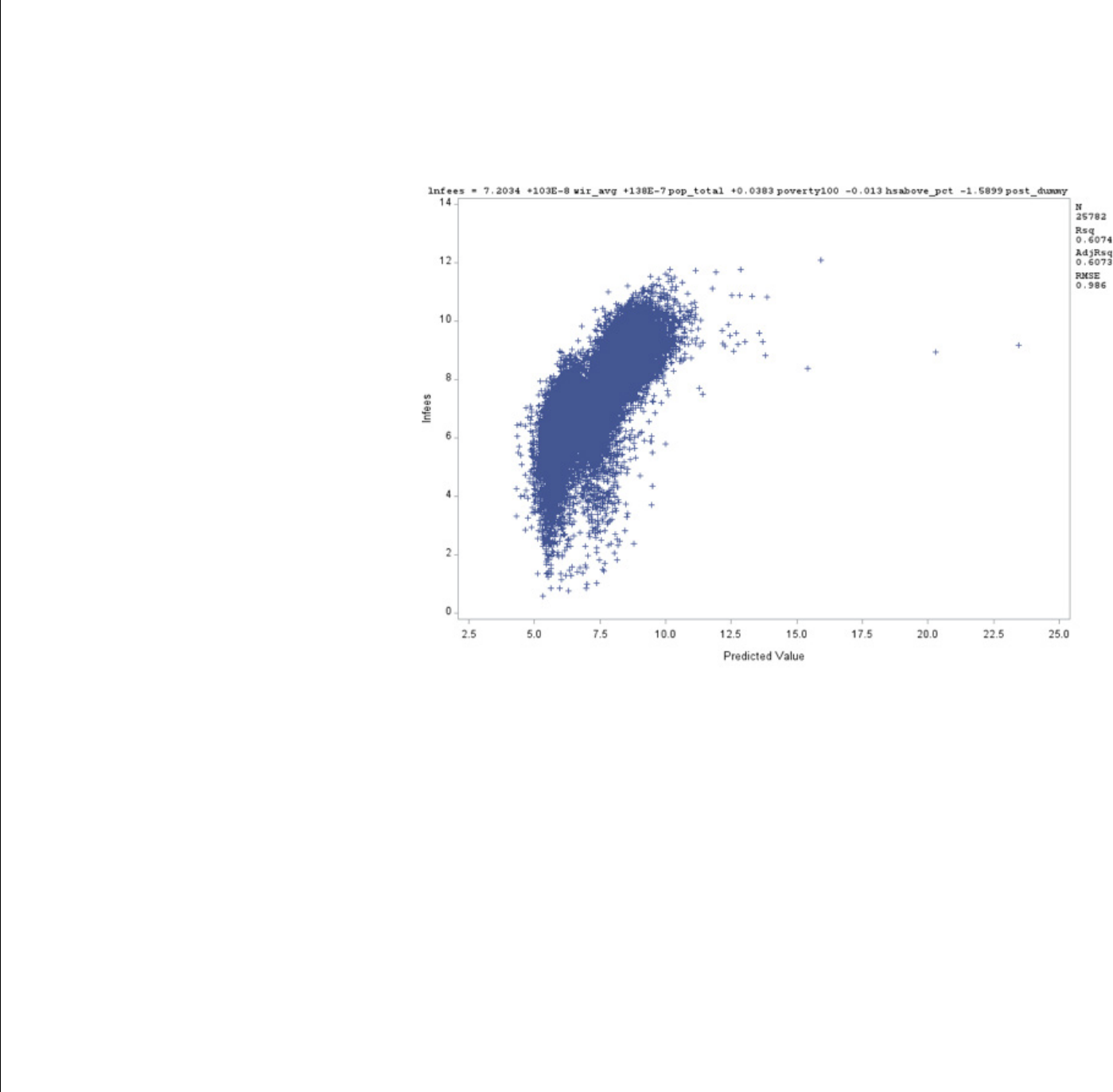

The OIG created a multiple linear regression model to examine the effects of each of these factors on money order revenue, while

controlling for the other factors. The model showed that post ofces in ZIP Codes with higher population, more poverty, and lower

education levels sold more money orders. The full methodology and ndings are in Appendix A.

This model is useful because it allowed the OIG to identify high volume post ofces with favorable conditions for money

order sales, but that do not appear to be selling as many money orders as they could. If the Postal Service aims to increase

12 Federal Reserve System, 2013 Federal Reserve Payments Study: Recent and Long-Term Payment Trends in the United States: 2003-2012, p. 7.

13 Money orders over $500 come with a higher fee, and their sales volume has declined much more slowly than that of smaller money orders. With large money orders

making up a higher proportion of money order sales, the average revenue per money order has increased.

14 The Postal Service does not retain this level of data for more than 3 years, and pre- 2012 data were no longer available at the time of the OIG’s analysis.

15 The OIG also tested the proximity to the nearest Walmart, which has emerged as a powerful player in the money order space. But this proved to be a statistically

insignicant factor in predicting the money order sales of a given post ofce.

16 On Average, POSt Plan locations saw money order fee revenue decline about seven times faster than non-POSt Plan ofces between 2012 and 2015. A brief explanation

of POSt Plan can be found at http://about.usps.com/publications/annual-reports/2012/path-our-nancial-plan.html.

About 1,200 high volume post

ofces grew their money order

sales by at least 10 percent

from 2012 to 2015.

Figure 3: Money Order Use Declining

USPS MONEY ORDER USE IN DECLINE

Postal money order use has plunged 60 percent since its peak in

2000 in the wake of alternatives from other providers and broad

shifts toward electronic forms of payment.

Source: Federal Reserve, which processes postal money order payments.

Note: The number of money orders processed is lower than the number sold.

0

50

100

150

200

250

1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015

Number of postal money orders

processed each year (millions)

Peak of 230 million in 2000

92 million in 2015

Modernizing the Postal Money Order

Report Number RARC-WP-16-007

7

Executive Summary

Table of Contents

Observations

Appendices

Print

money order sales, implementing best practices at these

underperforming ofces could be the low-hanging fruit, where

the opportunity for improvement is the greatest. In addition to

enhancing the customer experience, these changes also could

pay off nancially. If the Postal Service stabilized and grew

sales at just the 1,000 lowest performing locations for money

orders, it could generate $9 million in additional revenue over

5 years, compared to what projected revenues would be if

current trends continued.

17

There Are Other Providers of

Money Orders

The Postal Service sold money orders at about

31,800 postal retail locations in 2015, but there are a number

of providers of money orders beyond just the Postal Service.

While many commercial banks offer money orders, the two

largest providers are Western Union and MoneyGram, which

offer products through a massive network of some 100,000

private U.S. and Canadian retailers who act as agents.

18

Many pharmacies, convenience stores, supermarkets, big box

retailers, liquor stores, check cashers, and payday lenders are

agents for Western Union or MoneyGram, typically selling a

variety of products, including money transfers and bill pay.

The overall size of the money order market is difcult to pin

down precisely. In 2014, MoneyGram reported $54 million

in money order revenue, down 2 percent from the previous

year.

19

Western Union lumps money orders in with “other” revenue, which also includes foreign exchange and prepaid services. Its

“other” revenue was $118 million in 2014.

20

For both Western Union and MoneyGram, money orders comprise less than 4 percent

of their overall revenue.

21

17 This is a cumulative 5-year estimate. It includes money order fees and projected escheatment income. The OIG identied more than 4,000 potentially underperforming

money order post ofces.

18 Western Union has some 50,000 U.S. agents and MoneyGram has 56,000 in the United States and Canada. Securities and Exchange Commission, The Western Union

Co. Form 10-k Annual Report, February 20, 2015, http://edgar.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1365135/000136513515000008/wu-12312014x10k.htm,

p. 6 and Securities and Exchange Commission, MoneyGram International, Inc. Form 10-k Annual Report, March 3, 2015, http://edgar.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/

data/1273931/000127393115000032/mgi2014123110-k.htm, p. 7.

19 Securities and Exchange Commission, MoneyGram International, Inc. Form 10-k Annual Report, p. F-47.

20 Securities and Exchange Commission, The Western Union Co. Form 10-k Annual Report, pp. 57, 70, and 146.

21 Ibid., p. 146 and Securities and Exchange Commission, MoneyGram International, Inc. Form 10-k Annual Report, p. F-47.

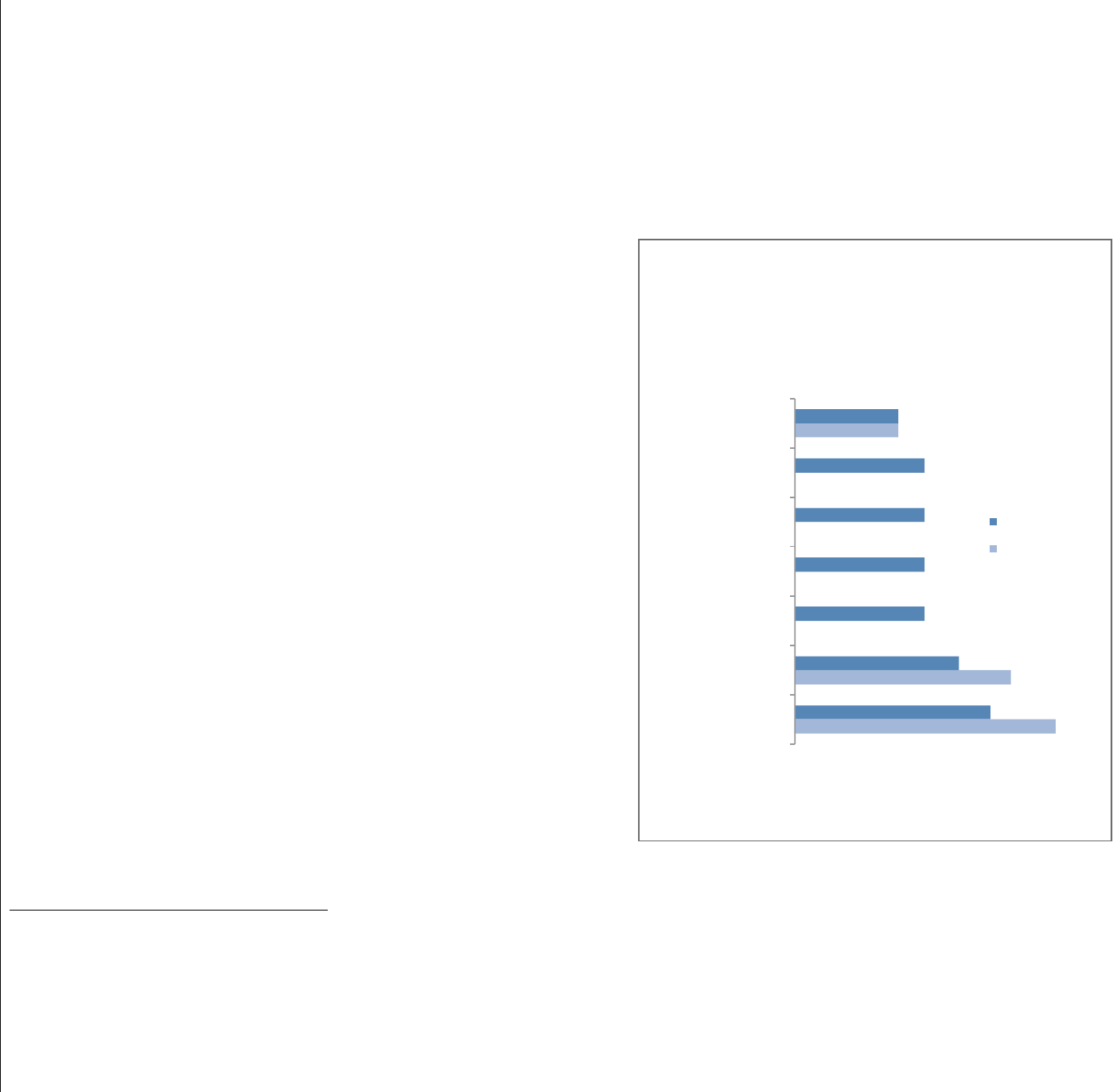

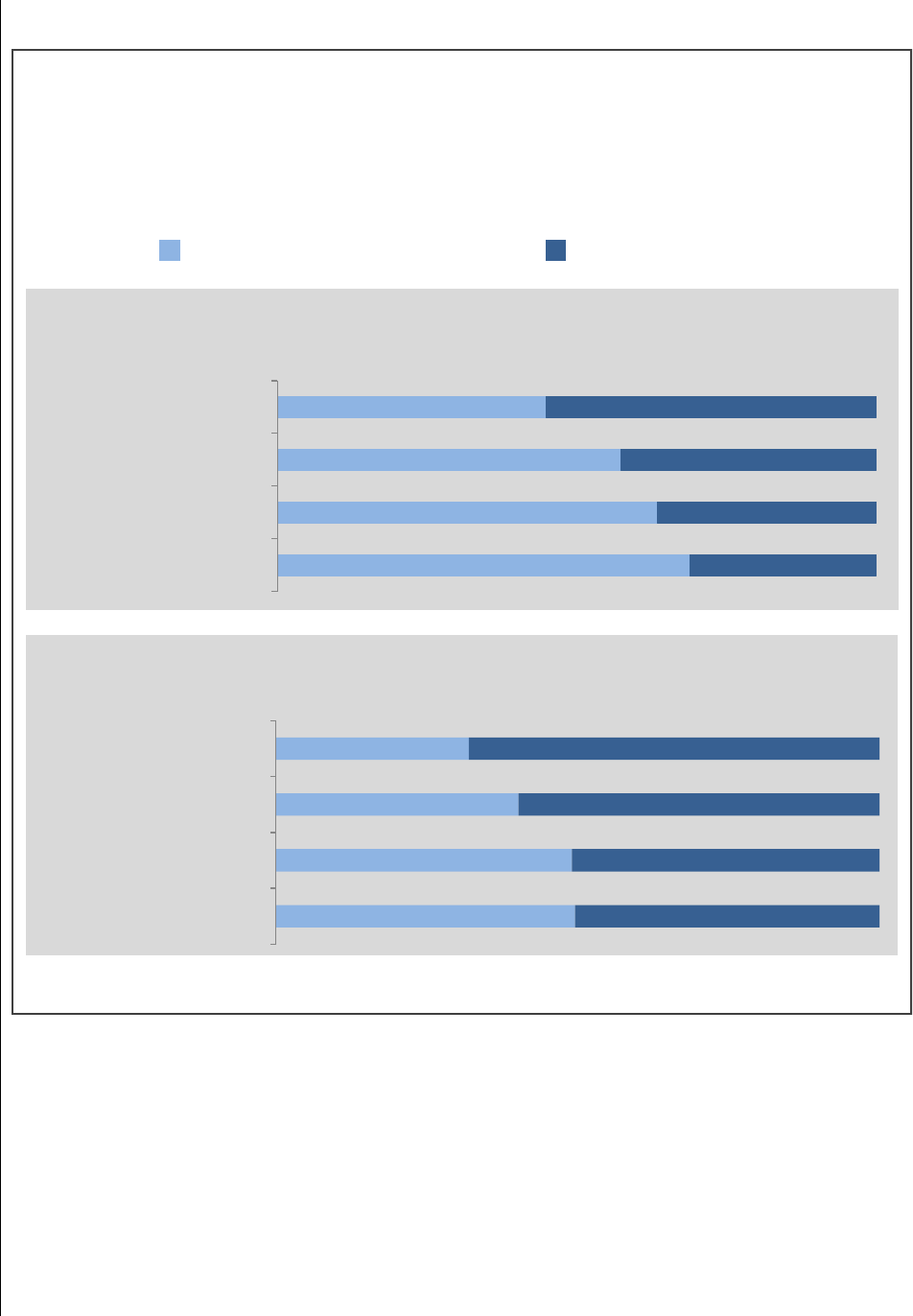

Figure 4: High Volume Ofces Have Stable Sales

HIGHER VOLUME POST OFFICES HAVE

MORE STABLE MONEY ORDER SALES

While post offices that sell few money orders have seen a

32-percent dive in money order sales since 2012, high

volume locations — which account for three quarters of all

money order fee revenue — have been relatively flat.

Source: OIG analysis of data from the Postal Service Accounting Data Mart.

Post office percentile for

money order sales

75

th

-100

th

50

th

-75

th

25

th

-50

th

0

th

-25

th

2012

2013

2014 2015

Percent change in average money order fees since 2012

-35%

-30%

-25%

-20%

-15%

-10%

-5%

0%

-1%

-7%

-32%

-17%

Modernizing the Postal Money Order

Report Number RARC-WP-16-007

8

Executive Summary

Table of Contents

Observations

Appendices

Print

Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC) survey data from 2013 estimate that 21 million households had purchased a non-bank

money order in the previous year.

22

Of those households, 30 percent said they usually buy their money orders at the post ofce.

However, among the 10 million households that had used money orders in the last 30 days — those most likely to be heavy users

— only 23 percent used postal money orders. This suggests that postal money orders have a higher usage rate among infrequent

users. In 2011, the FDIC did the same study.

23

Between 2011 and 2013, the OIG estimates that the overall number of money

orders sold fell 3 percent — though the Postal Service accounted for all of that decline. Our analysis suggests that the number of

non-postal money orders sold actually increased slightly between 2011 and 2013. Details of that analysis are in Appendix B.

While the Postal Service does not appear to sell as many money orders

as Western Union and MoneyGram, it generates at least as much

money order revenue as both of them combined.

24

Much of that has

to do with pricing. The Postal Service charges a $1.25 fee for money

orders of up to $500 and $1.65 for larger money orders up to $1,000.

25

Western Union and MoneyGram agents have some latitude in setting

money order prices, which vary widely. Based on inquiries at agents

around Washington, DC, and in rural Virginia, a money order could

cost as little as 75 cents or as much as $2.49. For example, Kash

King, a local check cashing establishment in the Washington, DC,

area, brands itself as “Home of the 75 Cent Money Orders.”

26

Many

providers beat the Postal Service on price, as Figure 5 illustrates. A

2011 Urban Institute study conducted on behalf of the Postal Regulatory

Commission notes that some private sector agents seem to use money

orders for “promotional value” —- intentionally pricing them below cost

and sometimes even issuing them for free — presumably in order to

attract customers to other more protable products.

27

Several other providers employ a tiered pricing system. For instance,

payday lender ACE Cash Express charges 89 cents for money orders

up to $99, 99 cents for amounts from $100 to $249, $1.49 for amounts

from $250 to $499, $1.99 for amounts from $500 to $999, and $2.49

for $1,000 money orders.

28

In this case, the Postal Service charges a

higher price for money orders of less than $250, but a lower price for

larger money orders.

22 Based on OIG analysis of FDIC data. FDIC, 2013 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, 2014, https://www.fdic.gov/householdsurvey/. Raw

data was obtained here: https://www.economicinclusion.gov/downloads/index.html.

23 Ibid.

24 Neither Western Union or MoneyGram report sales volume of money orders. This statement is based on estimates using the number of households that use non-postal

money orders.

25 U.S. Postal Service, Sending Money Orders, https://www.usps.com/shop/money-orders.htm.

26 Kash King website: http://www.kashking.com/.

27 Urban Institute, Transportation and Price Leadership Role of the Postal Service, August 16, 2011, http://www.prc.gov/sites/default/les/archived/Price_Leader_Report.pdf,

p. 17.

28 Based on calls made to three ACE Cash Express locations in the Washington, DC, area in November 2015.

Figure 5: Money Order Pricing

MONEY ORDER PRICES VARY WIDELY

For money orders of up to $500, the U.S. Postal

Service is up to 58 percent more expensive than other

national retailers.

*Do not offer money orders of more than $500

†Tiered pricing for very small money orders goes as low as 89 cents

Source: OIG research on a sample of locations in the Washington,

DC, area and rural Virginia. Pricing may vary by region and franchise.

$0.79

$0.99

$0.99

$0.99

$0.99

$1.25

$1.49

$0.79

$1.65

$1.99

Walmart

(MoneyGram)

Advance America

(MoneyGram)*

CVS (MoneyGram)*

Rite Aid (Western

Union)*

Safeway (Western

Union)*

U.S. Postal Service

Ace Cash Express

(MoneyGram)†

Less than $500

$500 to $1,000

Retailer (money

order vendor)

U.S. Postal

Service

Money order size

Price

Up to $500

$501

Modernizing the Postal Money Order

Report Number RARC-WP-16-007

9

Executive Summary

Table of Contents

Observations

Appendices

Print

If the Postal Service sought to increase the number of pricing tiers for money orders, there is a precedent: from 1966 to 1985,

there were three pricing levels for postal money orders.

29

Additionally, other posts, including An Post in Ireland and the Post Ofce

in the United Kingdom, have a four-tiered pricing system.

30

In both cases, small value postal money orders are comparatively

cheaper in Ireland (87 cents) and Great Britain (73 cents) than in the United States.

31

Although the price of a postal money order has changed nine times since 1988, those price hikes have actually not even kept

pace with ination, causing the real price to decline 17 percent over that period.

32

Unlike private providers, the Postal Service faces

signicant regulatory hurdles for all price changes to money orders.

33

Many View Postal Money Orders as a Premium Product

Postal money orders have several real and/or perceived advantages over other money orders. For one, they can be cashed for

free at any post ofce, provided funds are available.

34

None of the 14 pharmacies, convenience stores, supermarkets, or big box

stores contacted by the OIG would cash even the money orders they sell themselves. Some recipients of payments and banks

treat postal money orders like cash, while they treat private label money orders like checks that must rst clear before funds are

available.

35

Thus, postal money orders serve the needs of businesses looking for secure and reliable payment options.

The Postal Service also is one of the few national providers that sells money orders over $500 in face value.

36

The size is

important, as many payments, particularly rent/mortgage, often are greater than $500. The post ofce also is one of the relatively

few places that allow customers to pay for a money order with a debit card.

37

This can be especially helpful to the growing number

of Americans who receive their pay via a prepaid card, such as the 5 million federal benets recipients who use the Treasury

Department’s Direct Express prepaid debit card.

38

They collectively spent $297 million at the Postal Service in 2014 — more than

they spent at any other merchant save for one, which was an undisclosed large national retailer.

39

The perceived superiority of postal money orders shows up in message board discussions when ecommerce buyers and sellers

debate the merits of different payment options. “I only accept USPS money orders. You cash them at the post ofce and they can

tell right away before you ship the item if it is good. I have never had a problem with them,” wrote an Etsy seller.

40

“USPS money

orders are the safest you can get. Take it to the Post Ofce, get CASH, hand the package to the clerk. Unlike depositing a money

order in your bank account, once the [post ofce] hands you cash, you are good to go,” wrote an eBay seller.

41

Though anecdotal,

these opinions from real users help illustrate why many prefer postal money orders to others.

29 Based on a money order fee history provided by the Postal Service.

30 An Post, Money Transfers, http://www.anpost.ie/AnPost/MainContent/Personal+Customers/Money+Matters/Money+Transfer/ and Post Ofce, Postal Orders,

http://www.postofce.co.uk/postal-orders.

31 Yahoo Currency Converter, January 15, 2016, http://nance.yahoo.com/currency-converter/#from=USD;to=EUR;amt=1.

32 OIG analysis of Postal Service and Bureau of Labor Statistics data: http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpid1512.pdf, p. 74.

33 Money orders are classied as a “market dominant” product.

34 U.S. Postal Service, Domestic Mail Manual: S020 Money Orders and Other Services, http://pe.usps.com/Archive/HTML/DMMArchive0810/S020.htm.

35 For example, the Federal Bureau of Prisons puts a 15-day hold on payments to inmates made with non-postal money orders, but makes the funds from postal money

orders available immediately, https://www.bop.gov/inmates/communications.jsp.

36 Of the locations contacted in this study, only Walmart and ACE Cash Express offered high dollar money orders.

37 Of the locations contacted in this study, all but two restricted payment for money orders to cash only.

38 Bureau of the Fiscal Service, Direct Express Debit MasterCard Card Program: 94 percent Customer Satisfaction Rating for Sixth Consecutive year, March 2015,

http://www.scal.treasury.gov/fsservices/indiv/pmt/dirExpss/dirExpss_blog.htm and Pew Charitable Trusts, Why Americans Use Prepaid Cards, February 2014,

http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/uploadedles/pcs_assets/2014/prepaidcardssurveyreportpdf.pdf, pp. 1–3.

39 Based on a June 19, 2015 conversation with the director who oversees Direct Express. The program advises users to use their Direct Express card to purchase postal

money orders to pay rent, https://scal.treasury.gov/godirect/social-security-federal-benets-direct-deposit/directexpress/index.html.

40 Etsy, Should I Accept a USPS Money Order?, https://www.etsy.com/teams/7718/questions/discuss/12470627/.

41 eBay, Should I Accept a USPS Money Order as Payment for an Item?, http://community.eBay.com/t5/Archive-Miscellaneous/Should-I-accept-USPS-money-order-as-

payment-for-an-item/td-p/18359545.

Small businesses use postal

money orders as a reliable,

inexpensive way to

receive payment.

Modernizing the Postal Money Order

Report Number RARC-WP-16-007

10

Executive Summary

Table of Contents

Observations

Appendices

Print

One of the Postal Service’s biggest shortcomings in the money order space is its thin menu of additional alternative nancial

services compared to other providers. Most Western Union and MoneyGram agents, including pharmacies and convenience

stores, also offer money transfers, bill pay, and prepaid cards. Many agents, including Walmart and standalone nancial providers

like ACE Cash Express, also offer check cashing and/or small dollar loans. FDIC data show that money order users who use

multiple alternative nancial services are signicantly less likely to buy their money orders from the Postal Service. For example,

57 percent of households that use check cashing also use money

orders, but only 20 percent of those that use both services buy their

money orders from the Postal Service — presumably in large part

because post ofces do not offer payroll check cashing.

42

While the

Postal Service offers some money transfers, prepaid gift cards, and

limited cashing of Treasury checks, the existence of these services

is not well known and sales are miniscule. If post ofces were more

of a one-stop-shop for affordable alternative nancial services, this

convenience could save customers valuable time and money.

Most Payments Are Going Electronic. Money Orders Could Too.

Americans are choosing to pay more of their bills electronically,

which can be more convenient and inexpensive for some. This

includes direct payments made through billers’ websites and bank-

based bill pay services. If the Postal Service introduced an electronic

money order, as many foreign posts have done, it may be in a better

position to serve the needs of individuals and businesses looking for

modernized payment options.

For instance, Australia Post lets customers purchase money orders

through its website, as shown in Figure 6. Customers can opt to have

a paper money order printed and mailed or have a voucher emailed

to the recipient. Vouchers can be redeemed for cash at the nearest

post ofce.

43

Several other foreign posts also offer payment services

through web or mobile portals, including Israel Post, Swiss Post, and

Poste Italiane.

44

Online money orders are generally not available in

the United States. At least one company, Payko, made a short-lived

entrance to this market.

45

However, it did not have the reach, trust,

or built-in customer base of the Postal Service, which may have a

strong market opportunity to offer such a product.

42 OIG analysis of 2013 FDIC data.

43 Australia Post, Domestic Money Transfer (Money Orders & Vouchers), http://auspost.com.au/money-insurance/domestic-money-transfer.html.

44 Israel Post, Postal Check (Money Orders) in Israel, http://www.israelpost.co.il/postshirut.nsf/misparide/102?OpenDocument and PostFinance (the nancial services unit

of Swiss Post), Domestic Payments, https://www.postnance.ch/en/priv/prod/pay/national.html and Poste Italiane, Payments, http://www.poste.it/bancoposta/pagamenti/

pagamenti.shtml.

45 Justin Pritchard, “Why You Can’t Find Money Orders Online,” About.com, November 26, 2014, http://banking.about.com/od/MoneyOrders/a/Why-You-Can-T-Find-Money-

Orders-Online.htm and Alia Hoyt, “Can You Get a Money Order Online?” HowStuffWorks.com, October 10, 2011, http://money.howstuffworks.com/personal-nance/

online-banking/money-order-online.htm.

Figure 6: Australia Post’s Online Money Order

The Postal Service offers fewer

alternative nancial services

compared to other money

order providers.

Source: Screenshot from http://auspost.com.au/money-

insurance/domestic-money-transfer.html.

FOREIGN POSTS OFFER

ELECTRONIC MONEY ORDERS

Some posts abroad, including Australia Post, offer

electronic money orders. The U.S. Postal Service

could introduce a similar product.

Modernizing the Postal Money Order

Report Number RARC-WP-16-007

11

Executive Summary

Table of Contents

Observations

Appendices

Print

In an effort to bundle money orders with core mail products, several international posts promote the ability to deliver money orders

to recipients through the mail. While the typical time for delivery is 3 to 5 business days, Correos, the Spanish postal operator, also

offers the option to send a money order via express service. For a fee of 15 euros (about $17) plus 1.25 percent of the face value,

Correos will deliver the money order the same day in certain large cities and overnight anywhere else in the country.

46

Meanwhile,

India Post offers a slightly different method of delivery for money orders as an option for consumers. With its Instant Money Order,

it allows customers to purchase a money order at any post ofce, but instead of a physical money order, the customer receives a

unique code that can be transmitted to the recipient via phone, email, or text message and then used to obtain cash at select India

Post retail locations.

47

A Look at Money Order Users

People from all walks of life use money orders, and they

use them in different ways and for different reasons. The

U.S. Census Bureau conducts a biennial survey for the

FDIC on the nancial lives of Americans who are partially

or completely left out of the mainstream nancial system —

including those who use money orders.

48

The OIG analyzed

the raw survey data to glean signicant insights into this

population.

49

The OIG also conducted interviews with

50 money order users at post ofces in the

Washington, DC, area.

50

Heavy Users Comprise Three-Fourths of Postal Money

Order Purchases

An estimated 6.4 million households bought postal money

orders in 2013, buying an average of 16 money orders

per year, but that is not the complete picture.

51

The OIG

estimates that 35 percent of users accounted for three

quarters of sales, buying an average of three postal money

orders per month.

52

Users interviewed by the OIG said

they use money orders to pay monthly bills, with the most

popular being rent/mortgage payments (78 percent), utilities/

unspecied bills (58 percent), and insurance payments

(10 percent).

46 Correos, Giro Nacional Money Remittance, http://www.correos.es/ss/Satellite/site/servicio-1349171446591-envio_dinero_servicios_nancieros/detalle_servicio-

sidioma=en_GB and Yahoo Currency Converter, January 15, 2016, http://nance.yahoo.com/currency-converter/#from=USD;to=EUR;amt=1.

47 India Post, Instant Money Order (iMO), http://www.indiapost.gov.in/IMOS.aspx.

48 FDIC, 2013 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, p. 4.

49 This was a very large sample survey, making it highly statistically valid.

50 This was a non-scientic survey conducted July 2, 2015 at two Washington, DC, area post ofces. It may not represent all money order users.

51 The Postal Service sold 102.3 million money orders in FY 2013. U.S. Postal Service, “USPS-FY13-4 - FY 2013 Market Dominant Billing Determinants,” Postal Regulatory

Commission Docket No. ACR2013, December 27, 2013, http://www.prc.gov/dockets/document/88662.

52 This assumes that households that had purchased a money order in the past year, but not in the past 30 days, bought an average of six money orders per year.

Households that purchased a money order in the past 30 days bought an average of 35 per year. For the full methodology behind this estimate, see Appendix B.

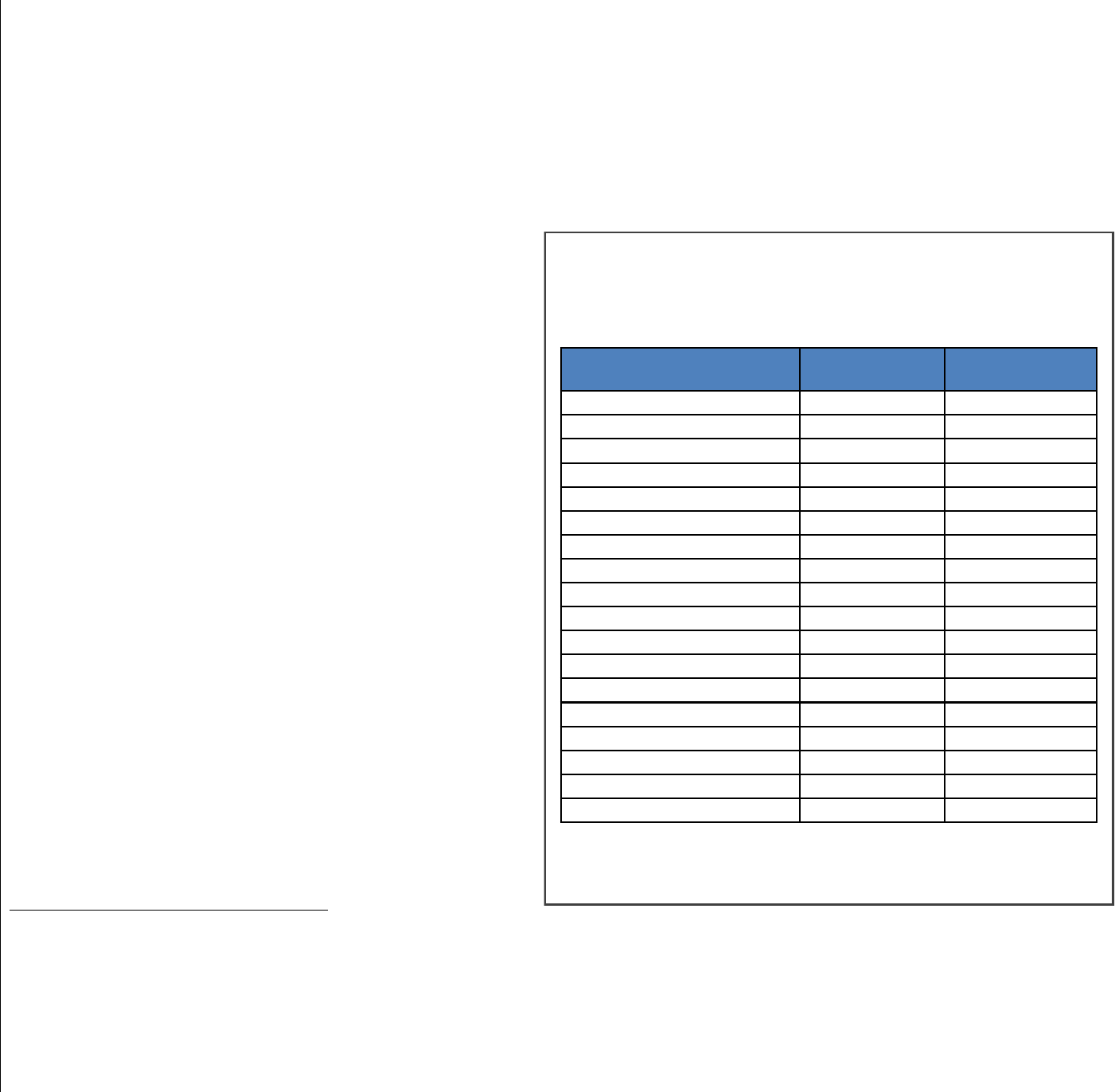

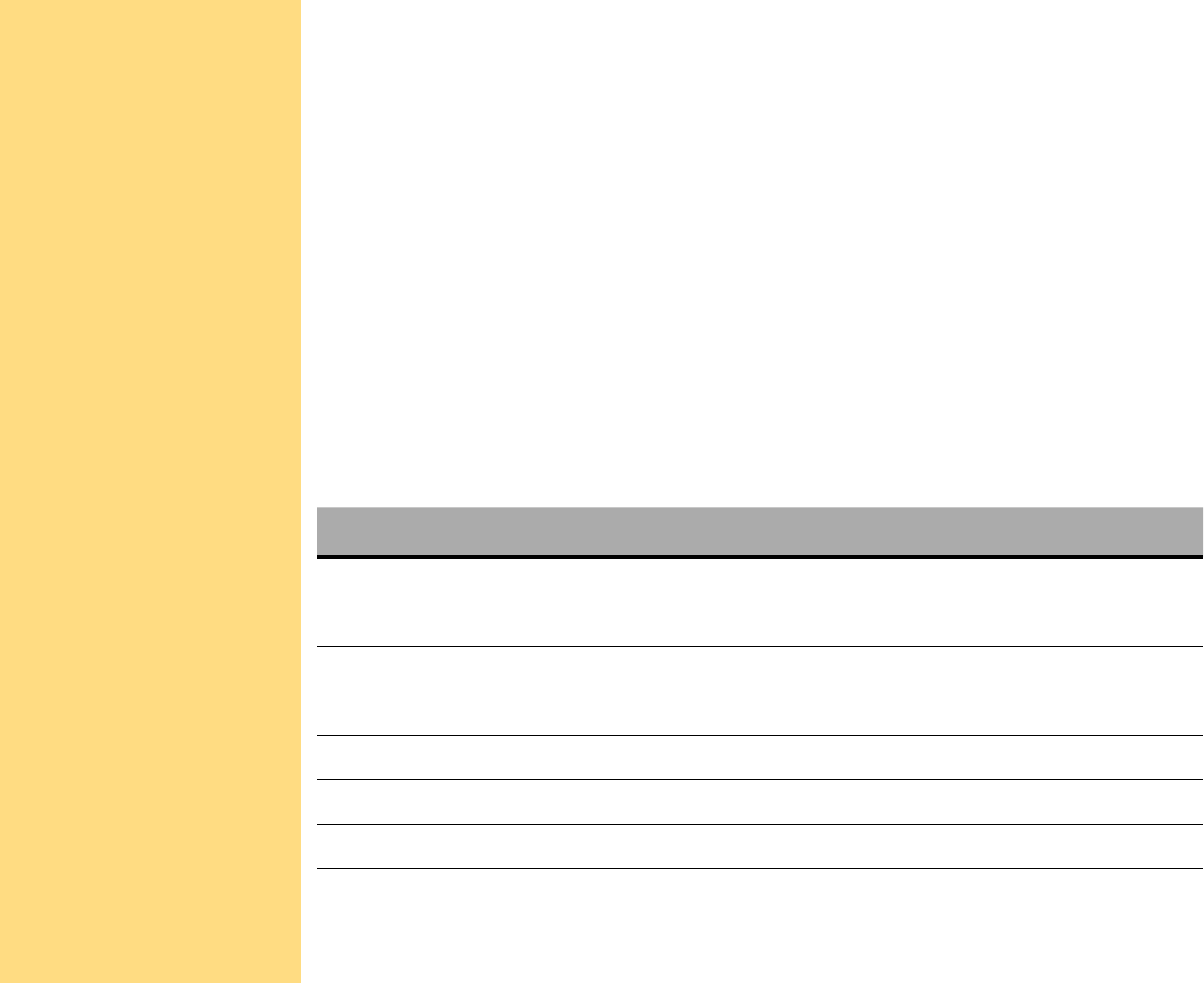

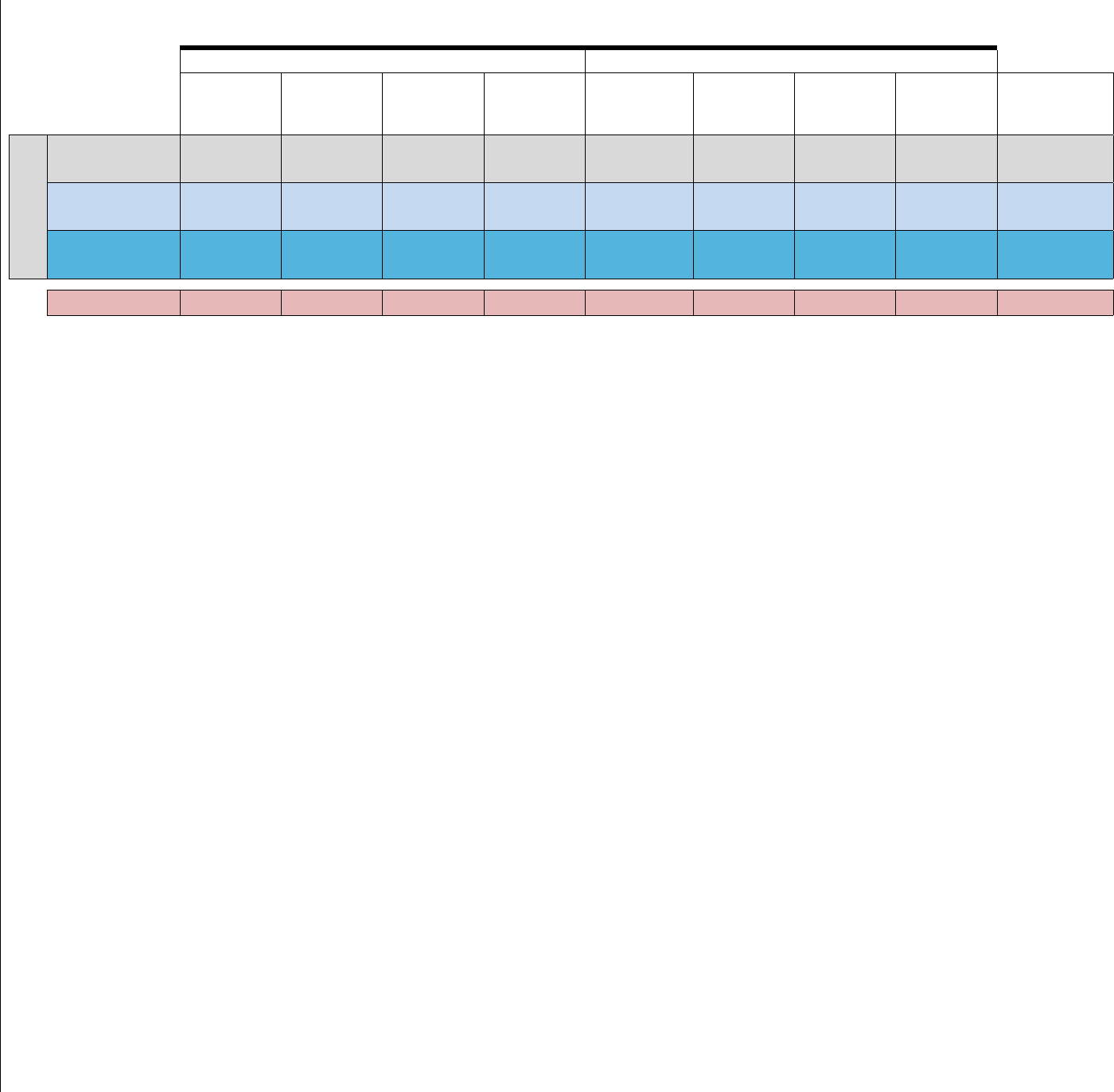

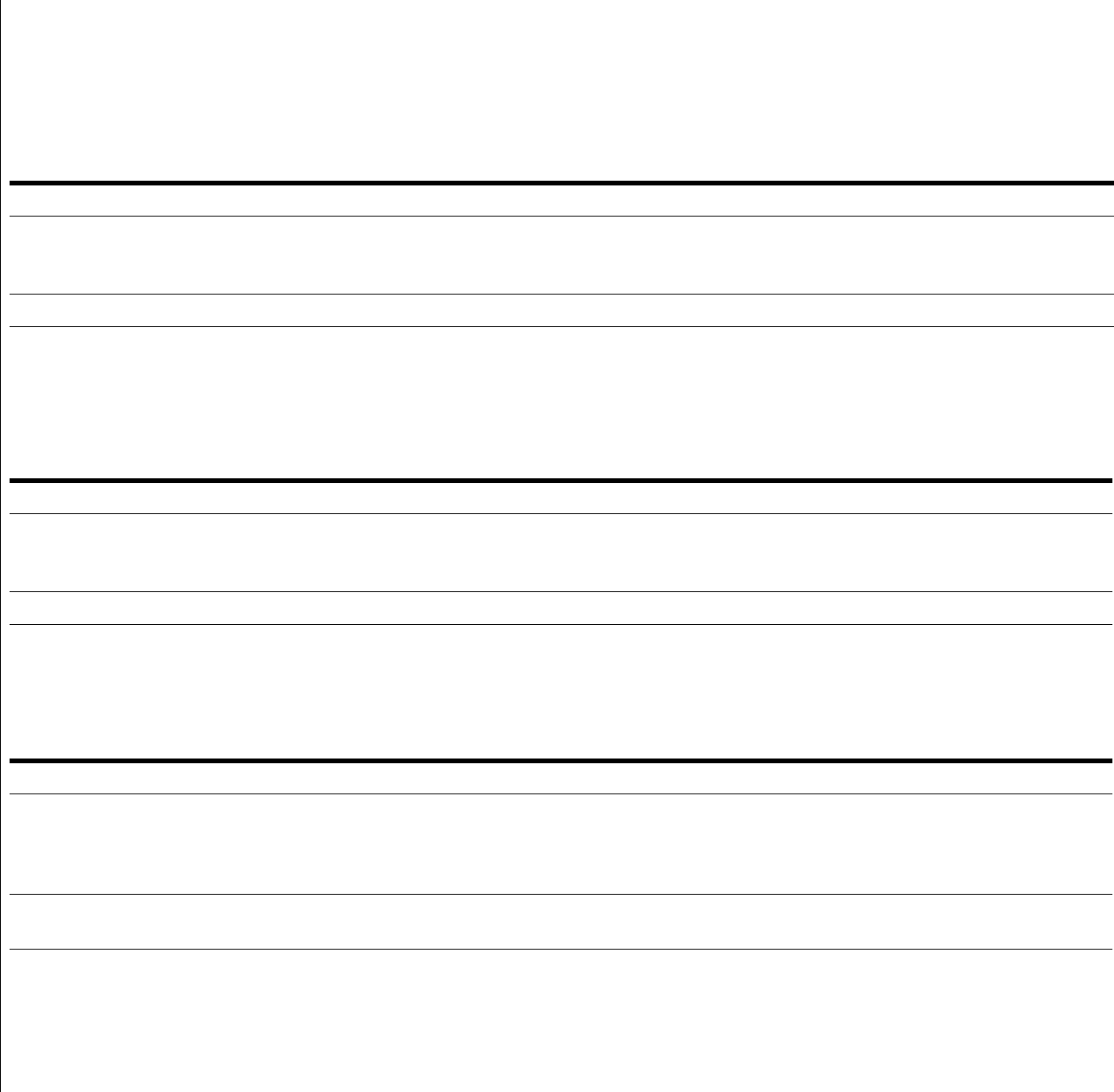

Figure 7: Postal vs Non-Postal Money Order Users

POSTAL VS NON-POSTAL MONEY ORDER USERS

Among households that purchased a money order in the past

12 months, those that bought them at post offices have some key

differences from those that purchased non-postal money orders.

*In the past 12 months

Source: OIG analysis of 2013 FDIC data on households that had used money

orders in the previous 12 months

.

Used postal

money orders*

Used non-postal

money orders*

Number of households 6,351,489 14,539,122

Have a bank account 86% 76%

Use check cashing* 15% 25%

Use international remittances* 8% 11%

Use pawn loans* 5% 11%

Use payday loans* 3% 7%

Use prepaid cards* 14% 20%

Use refund anticipation loans* 3% 6%

Use auto title loans* 2% 3%

Are under age 35 20% 35%

Are over age 54 38% 24%

Have a college degree 27% 17%

Are unemployed 6% 8%

Have $50,000+ income 39% 28%

Have a smartphone 57% 61%

Own their home 56% 38%

Are immigrants 15% 17%

Modernizing the Postal Money Order

Report Number RARC-WP-16-007

12

Executive Summary

Table of Contents

Observations

Appendices

Print

Users also tend to buy more of their money orders at the end of the week, when many get paid, and at the beginning of the month

when rent is due. Sales spike signicantly during those times.

53

Money Order Users Are Demographically Diverse

Households that use money orders are diverse by age, household income, and race/ethnicity — though they do stand out in some

key ways.

Age

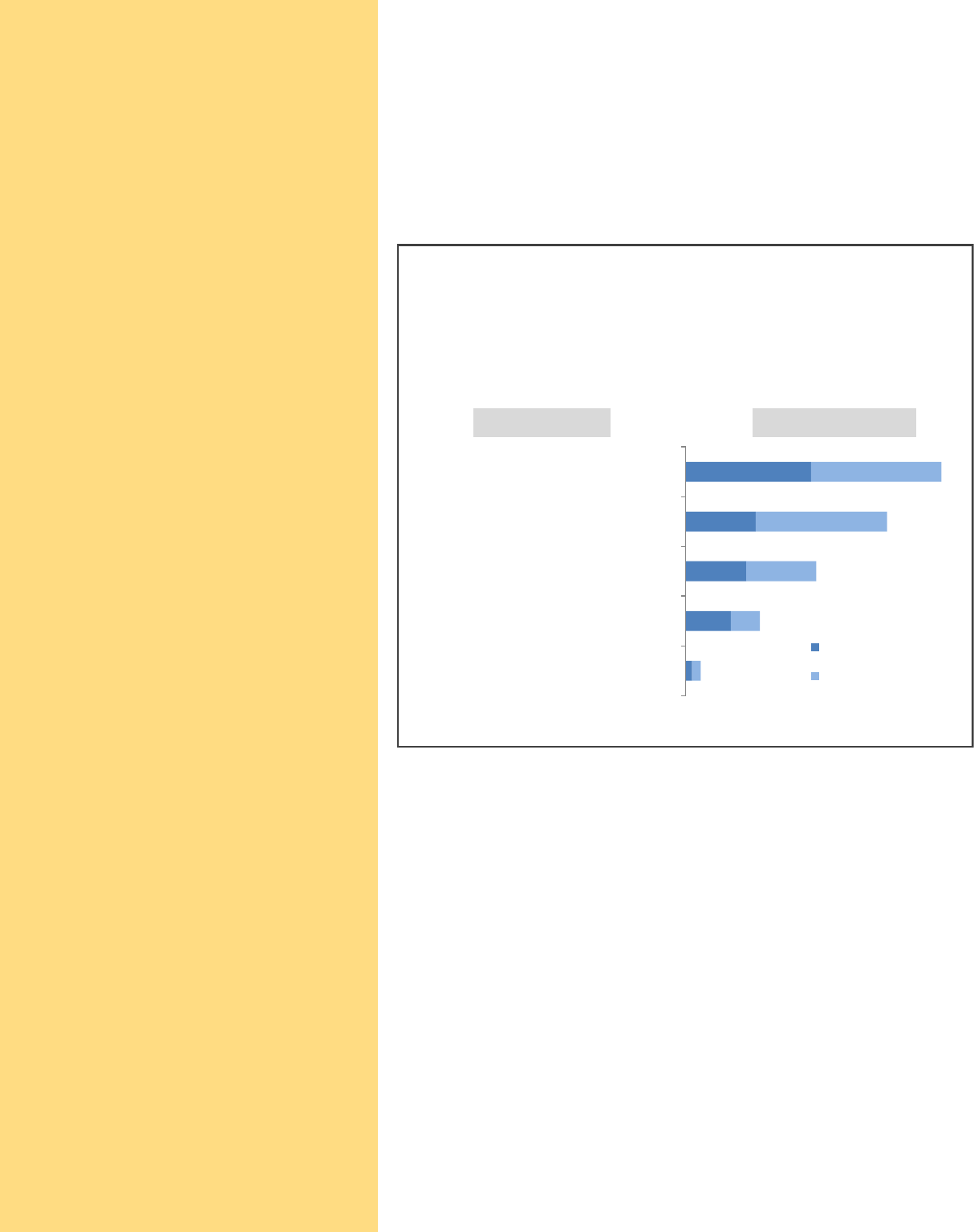

It is not surprising that younger households pay a much

greater portion of their bills electronically than older

generations, but it is surprising that young folks are

also signicantly more likely to use money orders than

older households.

54

This suggests that, for the relatively

few bills younger Americans pay in paper form, many

may prefer to pay them with money orders rather than

personal checks.

Young folks’ heavy utilization of money orders bodes

well for the future of the product. Unfortunately for the

Postal Service, households led by younger people are

signicantly less likely to buy their money orders at the

post ofce, as is illustrated in Figure 8. There may be

several reasons for this. Younger people might have

less familiarity with the Postal Service, as they use the

mail less frequently than older generations.

55

Also,

the Postal Service does not offer any online or digital

component to its money orders, and younger folks tend to

lean more on technology than older Americans.

Household Income

The lower a family’s income, the more likely it is to have

purchased a money order in the past year. It is especially more likely to have bought one in the past 30 days, yet higher income

families are still signicant customers. Nearly one-third of those who used a money order in the past year had household income

of at least $50,000. Among those who use money orders, higher income households are more likely to buy their money orders at

the post ofce than lower income families. This, again, may be because lower income households are more likely to use multiple

alternative nancial services, and may nd it more convenient to buy their money orders from providers that offer a broader range

of nancial products. See Appendix C for more detailed statistics on money order users and how those who buy their money

orders at the post ofce differ from those who buy money

orders elsewhere.

53 OIG analysis of data from the Postal Retail Data Mart.

54 U.S. Postal Service, The Household Diary Study: Mail Use & Attitudes in FY 2014, p. 36.

55 Ibid., pp. 31, 39, and 44.

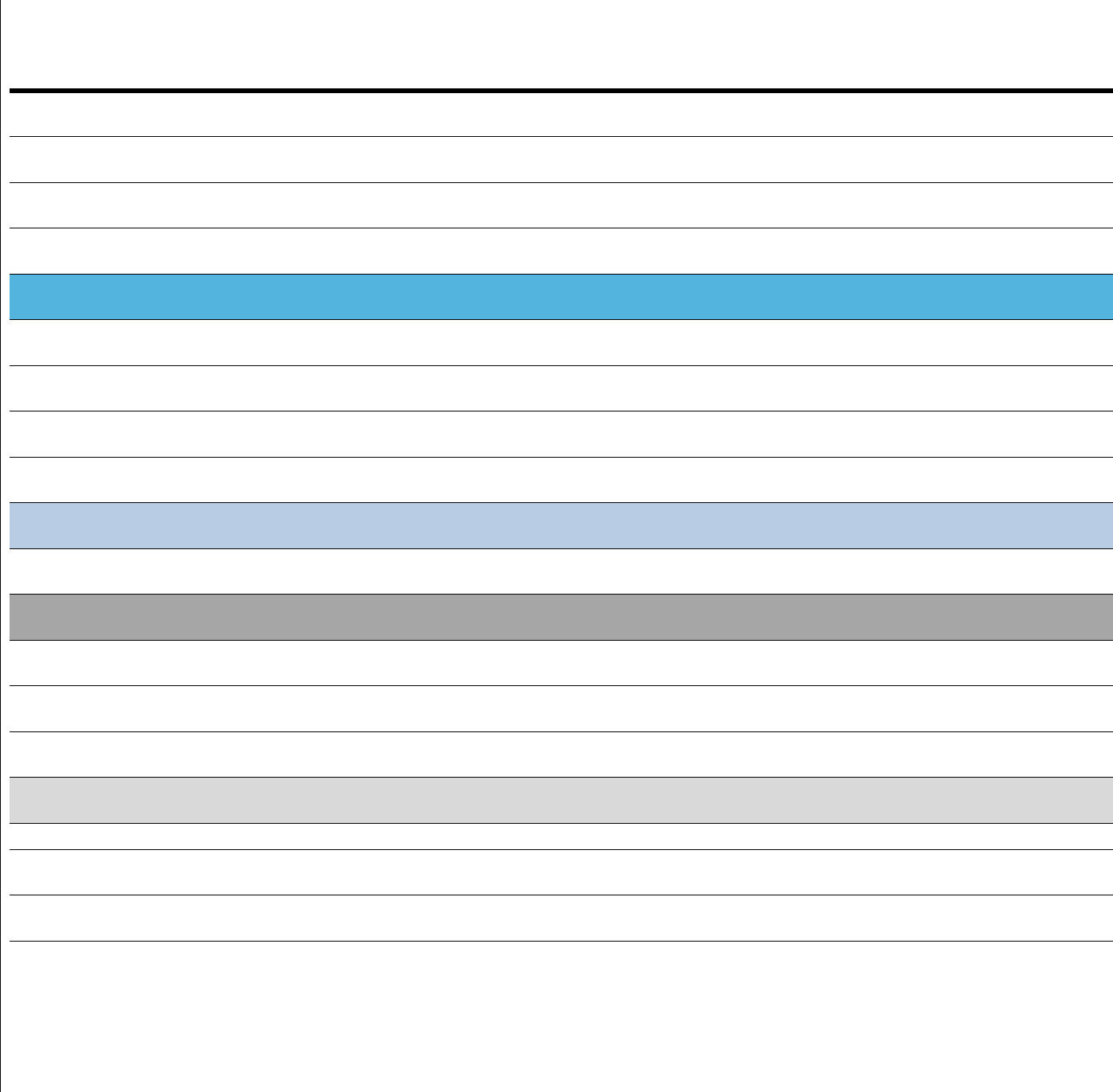

Figure 8: More Young Americans Use Money Orders

Lower income households

are more likely to use multiple

alternative nancial services and

may seek to buy their money

orders from providers with a

broader range of

nancial services.

YOUNGER PEOPLE USE MONEY ORDERS, BUT ARE

LESS LIKELY TO BUY THEM AT POST OFFICES

The younger a household, the more likely it is to use money

orders. Unfortunately, households led by younger people are also

less likely to buy their money orders from the Postal Service.

Source: OIG analysis of 2013 FDIC data on households that had purchased

a money order in the previous 12 months.

Portion that purchased a

money order in past year

Portion of money order users

who buy at post office

29%

22%

20%

18%

15%

10%

15%

22%

29%

32%

37%

42%

15 to 24

65+

25 to 34

35 to 44

45 to 54

55 to 64

Age

Modernizing the Postal Money Order

Report Number RARC-WP-16-007

13

Executive Summary

Table of Contents

Observations

Appendices

Print

Most Money Order Users Could Write Checks Instead. Why Don’t They?

Eighty-six percent of postal money order users have a bank account, and 82 percent have a checking account.

56

Why would they

bother going to the post ofce and paying $1.25 to $1.65 for a money order when they could spend a fraction of the time and

money by writing a check from the comfort of their own homes? There is no hard data on this, but based on conversations with

money order users and research on other alternative nancial services, we have some educated guesses.

■

Money orders do not lead to overdrafts: For those with low balances on their bank accounts, there is legitimate anxiety

about overdraft fees, which typically cost about $35 for each offense.

57

And they can quickly compound, with the average

overdraft costing consumers a total of $69 in fees — enough to throw a wrench in a family’s budget.

58

By comparison, a

$1.25 money order fee is very affordable.

■

Many families prefer to use all cash budgets: A popular (and effective) budgeting technique is to pay for everything in cash,

which makes it more difcult to overspend.

59

Many families on all cash budgets use money orders to pay bills — which would

help explain why customers purchased 71 percent of the postal money orders sold in 2015 with cash.

60

■

Personal checks are much less secure than money orders: When you write someone a personal check, you are giving

them all the information they need to withdraw money fraudulently from your account.

61

For payments made to entities you do

not necessarily trust, money orders are a much safer alternative.

■

Money order payments are guaranteed: While checks can bounce, money orders cannot. Their payments are guaranteed,

and they never expire.

62

For important bills, many money order users are willing to pay for that peace of mind.

■

Some billers ask to be paid with postal money orders: In interviews with money order users, 22 percent said the entity they

were paying asked to be paid with a postal money order. This includes some landlords, online sellers and

government entities.

63

56 OIG analysis of 2013 FDIC data.

57 The Pew Charitable Trusts, Overdrawn: Persistent Confusion and Concern About Bank Overdraft Practices, June 2014, http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/

assets/2014/06/26/safe_checking_overdraft_survey_report.pdf, p. 1.

58 Ibid.

59 Kim Tracy Prince, American Family Budget: Going All-Cash, All the Time, Mint Life, January 10, 2014, https://blog.mint.com/goals/american-family-budget-going-all-cash-

all-the-time-0114/ and Lampo Licensing, Dave Ramsey’s Envelope System, September 5, 2009, https://www.daveramsey.com/blog/dave-ramseys-envelope-system/.

60 OIG analysis of data from the Postal Service’s Retail Data Mart, which includes only POS and RSS locations.

61 Bob Sullivan, “Easy check fraud technique draws scrutiny,” NBC News, May 24, 2005, http://www.nbcnews.com/id/7914159/ns/technology_and_science-security/t/easy-

check-fraud-technique-draws-scrutiny/#.VovxMlWrRpg.

62 While postal money orders never expire, privately issued money orders may expire or decrease in value if not cashed within a certain period of time. U.S. Postal Service,

“Money Orders: What Are They?” https://www.usps.com/shop/money-orders.htm and Western Union, “Money Order Expiration,” https://thewesternunion.custhelp.com/

app/answers/detail/a_id/58/~/money-order-expiration.

63 The Landlord Protection Agency, “Tenant wants to pay rent with a money order,” May 10, 2012, https://www.thelpa.com/lpa/forum-thread/255154/Tenant-wants-to-pay-

rent-with-money-order.html; GunsAmerica, “GunsAmerica endorses USPS as exclusive form of non-credit card payment,” October 11, 2011, https://www.gunsamerica.

com/blog/gunsamerica-endorses-usps-as-exclusive-form-of-non-credit-card-payment/; Game Dude, “How to place an order with Game Dude,” www.gamedude.com/

mailorder.html; and Consulate General of Brazil in Atlanta, “Payment Options,” http://atlanta.itamaraty.gov.br/en-us/payment_options.xml.

Eight-two percent of postal

money order users have a

checking account.

Seventy-one percent of postal

money orders are purchased

with cash.

Modernizing the Postal Money Order

Report Number RARC-WP-16-007

14

Executive Summary

Table of Contents

Observations

Appendices

Print

Best Practices for Money Order Sales

As mentioned earlier, about 1,200 high volume post ofces have seen a 10 percent or greater jump in money order sales since

2012.

64

These high performing locations collectively grew their money order fee revenue by 20 percent. Their overall walk-in

revenue was essentially at, suggesting that money orders — which were present in 15 percent of the revenue transactions at

these locations — were a particular area of strength. On the ipside, about 500 high volume post ofces have seen a 20 percent or

greater decline in money order sales over the past 3 years. While location and external conditions explain some of the differences

between the low and high performers, sales execution may also be a signicant factor.

The best practices of high performers may

hold some lessons for other post ofces that may not be living up to their full potential for money order sales and customer service.

Here is a look at one of those top performers.

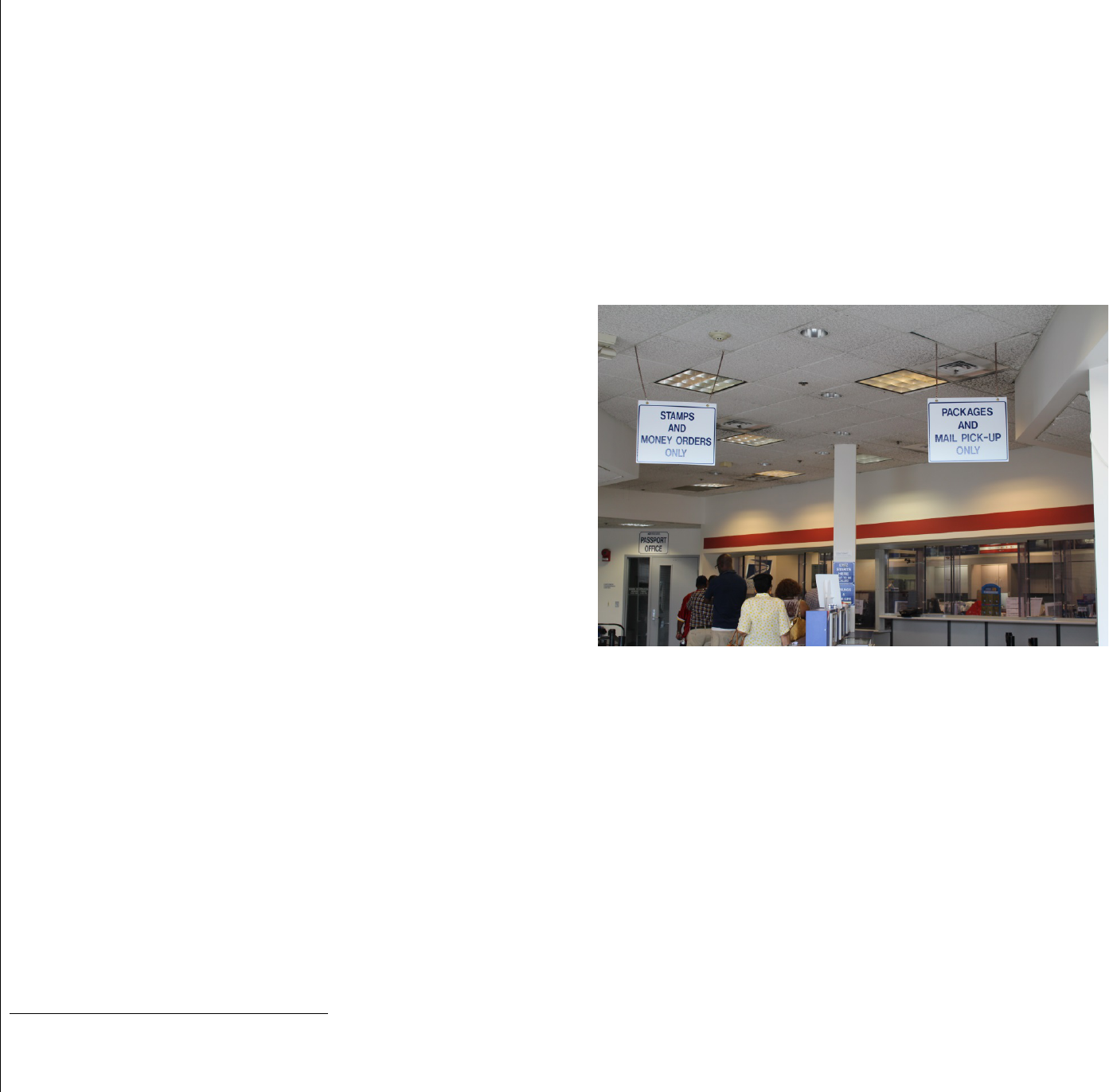

A Stand-Out Post Ofce: Frederick Douglass Station

Frederick Douglass Station in Southeast Washington is the top

seller of money orders in the Capital District, which includes the

District of Columbia and parts of Maryland.

65

Money orders were

present in 41 percent of the transactions at the post ofce in

FY 2015, when it sold more than 40,000 of them with a face value

of more than $11 million. Its money order fee revenue was up 23

percent from 2012, directly accounting for 11 percent of walk-in

revenue — though that gure is understated.

66

There are many nearby options for purchasing money orders.

The bustling shopping center where it operates has three bank

branches and a grocery store that sells money orders and

performs money transfers. The check cashing chain store two

blocks away also sells money orders. Despite many alternatives,

money order purchasers continue to ock to this location. Here

are some of the practices that contribute to its success.

■

A dedicated money order line: The post ofce has a separate line for customers buying money orders or stamps, which helps

improve customer ow and efciency of operations, ensuring that those in line for packages or mail pickup do not have to wait

behind money order customers. If there is no one in the packages line, the clerk at that window will serve the next money order

customer. When lines get really long, such as near the beginning of the month, there is a third retail window that staff will open

up to help keep the wait time down.

■

A specialized clerk: The money order line is generally staffed by a clerk with extensive experience selling money orders,

which is helpful in multiple ways. First, they know how to process the money orders quickly and efciently.

They also know their

customers, many of whom are regulars who come in month after month. These skills are well within the grasp of clerks at high

trafc money order locations.

64 High volume post ofces are those in the top 25 percent of all post ofces for money order fees.

65 Based on OIG analysis of money order data from the Accounting Data Mart.

66 The OIG estimates that every $1 in money order fees at Frederick Douglass Station led to an additional 53 cents in indirect revenue, which includes escheatment,

stamped envelope sales, and postage from mailed money orders.

Figure 9: Money Orders Line at Frederick

Douglass Station

Money orders are present in 41 percent of the transactions at Frederick Douglass

Station (above), a post ofce in Washington, DC.

The best practices of top

performing post ofces for

money order sales could hold

important lessons for other

post ofces.

Modernizing the Postal Money Order

Report Number RARC-WP-16-007

15

Executive Summary

Table of Contents

Observations

Appendices

Print

■

Customers have a good place to ll out their money orders: Many customers ll out their money orders at the post ofce,

so that they can mail them on the spot. To accommodate clientele who may prefer to sit, post ofce staff put in a table and

chairs, which are very popular with money order customers.

■

Sharing information on suspicious activity: When people try to buy or cash money orders in a way that seems suspicious,

staff le suspicious activity reports with the appropriate regulator. Postal staff also share information with colleagues at

other nearby post ofces where criminals may try the same scheme. Clerks also may alert the Postal Inspection Service,

which investigates money order fraud by postal customers. Specialized clerks can be particularly good at spotting potential

fraudsters.

Suggestions for Improving Service and Enhancing Revenue

Given the attractiveness of the money order business and the value it brings to the American people, the Postal Service could

take a series of initiatives to improve service and better meet the modern needs of those who purchase money orders and the

businesses that accept them as payment.

Assign a National Product Manager to Strategically Guide the Money Order Business

The Postal Service has not tasked anyone with strategic management of money orders.

67

Such a person, who should have deep

knowledge of the payments industry, could study the changing payments needs of people and businesses, ensuring that postal

money orders meet those needs. They also could work to understand and improve the product’s position in the marketplace and

implement the suggestions in this white paper. Given that postal money orders generate $21 billion a year in payments volume

and are present in 10 percent of all retail revenue transactions at post ofces, they seem to warrant a dedicated product manager

with expertise in the payments space.

Consider Potential Modernizations for Money Orders

Sell Paper Money Orders Online and through a Mobile App

Usps.com gets some 1.5 billion visits per year.

68

On the site, one can do everything from ordering stamps to printing postage

through Click-N-Ship, which customers used to print more than 50 million package labels in 2015, generating more than a half

a billion dollars in revenue.

69

Additionally, customers downloaded the USPS Mobile app 1.7 million times and made 77 million

visits to the mobile website m.usps.com.

70

All told, 46 percent of the Postal Service’s retail revenue comes from alternative access

channels like usps.com and USPS Mobile.

71

But to buy a postal money order, customers generally must do so in person at a

post ofce.

72

Among the 50 money order users interviewed for this white paper, nearly half said they would be likely to use an

app or online tool that allowed them to purchase a money order and have it delivered to a biller. It also could attract more young

Americans, many of whom are heavy users of non-postal money orders.

67 Based on conversations with Postal Service ofcials.

68 U.S. Postal Service, “Size and scope,” https://about.usps.com/who-we-are/postal-facts/size-scope.htm.

69 Ibid.

70 U.S. Postal Service, “The Post Ofce Is Always Open – USPS.com and USPS Mobile,” https://about.usps.com/who-we-are/postal-facts/always-open.htm.

71 U.S. Postal Service, “Size and scope.”

72 Money orders also can be purchased from rural mail carriers, who accept payment and have the customer ll out a form. The customer can provide a self-addressed

stamped envelope to receive the money order, or the carrier can deliver it on their next visit. U.S. Postal Service, S020 Money Orders and Other Services, Postal

Explorer, December 9, 2004, http://pe.usps.com/text/dmm/S020.htm.

Nearly half of the 50 postal

money order users interviewed

by the OIG said they would use

an online or mobile app to buy

money orders.

Modernizing the Postal Money Order

Report Number RARC-WP-16-007

16

Executive Summary

Table of Contents

Observations

Appendices

Print

Here is how such a service might work. Customers use a mobile app or usps.com to buy a money order, indicating the amount, the

recipient, and the recipient’s street address. Customers would pay for the money order and the postage with a debit/prepaid card

or by entering their checking account information. The money order could then be created at a central fulllment center and mailed

to the recipient.

73

The clerk’s time at the window comprises about two-thirds of the current costs associated with money orders.

74

Printing money

orders at central facilities could introduce signicant efciencies, making the product even more protable for the Postal Service

and generating more mail volume, given that all money orders purchased through this channel would be mailed. In addition, the

online channel would reduce opportunities for fraud or money laundering.

75

This process also could greatly strengthen the Postal Service’s relationship with money order users. Under the current model,

money orders are anonymous, one-off transactions that do not offer the Postal Service an opportunity to have an enduring

connection with the customer. The online/mobile channel could allow the Postal Service to communicate with its money order

users about their experience and make customer-centric improvements to the product and sales process.

76

The OIG estimates that adding the digital sales channel for paper money orders, along with active strategic management and

marketing, could lead to annual money order revenue of $238 million after 5 years — 59 percent higher than it would otherwise

be if current trends continue. The Postal Service would gain $232 million in cumulative additional revenue and $151 million

in contribution over that 5-year period. These estimates include the value of postage from mailed money orders. For the full

accounting and assumptions behind these gures, see Appendix D. Additionally, the Postal Service would likely not need the

Postal Regulatory Commission’s approval to begin selling paper money orders through digital channels.

Introduce Electronic Money Orders

In addition to allowing customers to purchase paper money orders online, the Postal Service also could offer fully-electronic

money orders — as many foreign posts have done. There would be capital costs to set up new systems for this innovation, though

the Postal Service could reduce those costs by partnering with a third party. And while it would require the approval of the Postal

Regulatory Commission, electronic money orders could truly bring this product into the digital age, allowing the Postal Service to

meet the modern payment needs of its customers.

One potential way to do this would be for the Postal Service to facilitate direct payments to large billers, such as utility, insurance,

credit card, and mortgage companies. Customers could select from a menu of participating billers, while seeing how quickly their

payment would arrive. The Postal Service could partner with a third party to get a directory of large billers and their payment

information, and the Federal Reserve could process the payments.

77

If the customer wants to pay a biller that is not on the list, the

Postal Service could cut a paper money order and mail it.

73 The Kansas City Stamp Fulllment Center or a similar facility could do this. Eventually, the Postal Service could move to place money order fulllment centers in selected

locations throughout the country and create each money order at the facility that is closest to the recipient. As a result, these payments could reach recipients days

quicker than a money order that was mailed from a single central facility — a signicant bonus for purchasers and recipients of money orders.

74 U.S. Postal Service, “USPS-FY15-2 - FY 2015 Public Cost Segments and Components,” Postal Regulatory Commission Docket No. ACR2015, December 29, 2015,

http://www.prc.gov/dockets/document/94340.

75 Most internal money order fraud happens at small post ofces where the clerk manually registers money order sales. The automation of digital channel sales would make

employee fraud much more difcult to perpetrate. In addition, having an electronic record of the purchaser and recipient could be a signicant deterrent for

money laundering.

76 Money order customers could opt-in to such communications and data collection as part of the online/mobile money order process.

77 The Federal Reserve, which processes paper postal money orders, facilitates electronic money transfers through the ACH system for the private sector. For the Fed to

process such payments for the Postal Service, the two organizations would need to modify their agreement, according to Federal Reserve ofcials interviewed by

the OIG.

Compared to money orders

purchased at post ofces,

paper money orders purchased

through digital channels could

be more protable and would

generate more mail volume.

Electronic money orders could

help small online merchants save

money on processing fees.

Modernizing the Postal Money Order

Report Number RARC-WP-16-007

17

Executive Summary

Table of Contents

Observations

Appendices

Print

Another approach would be to have the electronic money order purchaser provide the recipient’s email address. The

Postal Service could notify the recipient of the payment, giving them the option to have the funds transferred to their checking

account or prepaid card, or to take their emailed voucher into a post ofce for cash. This could be particularly attractive for small

online merchants who sell on sites such as eBay and Etsy. By receiving an electronic postal money order as payment, sellers

could avoid the processing fees they must pay for other types of payments, which are often 2.9 percent of the sale price, plus a

fee.

78

Sellers also could pick up their cash at a post ofce at the same time that they mail the merchandise to the buyer. Online

sellers already do this with paper money orders, though an electronic version would allow them to receive their payment much

more quickly.

79

Make Electronic Payments to Corrections Facilities

The Federal Bureau of Prisons, which tightly controls the channels through which millions of inmates and others can accept

payments, accepts paper money orders and electronic payments sent through MoneyGram and Western Union.

80

These electronic

transfers are priced three-to-eight times higher than paper money orders, creating a signicant opportunity for the Postal Service

to offer a more affordable electronic payment option for these citizens.

81

There also is a particularly strong public policy argument

to be made for the Postal Service to expand its payments services with respect to government entities, such as corrections

facilities.

Optimize the Retail Experience at High Volume Money Order Ofces

The retail experience is especially important at high volume money order locations, which account for three-fourths of all money

order fee revenue.

82

At these locations, money orders are present in an average of 14 percent of revenue transactions. Money

order transactions can impact wait time for all customers. High volume money order post ofces could minimize this by creating

a dedicated money order line staffed consistently by a clerk with the expertise needed to process money orders more efciently.

Post ofces with sufcient lobby space also could install a small table with a couple of chairs that customers can use to ll out their

money orders. Postal staff also could ensure that they consistently stock all counters and spaces with pens. Ultimately, a minimal

investment could have a huge impact on the customer experience and efciency.

While it makes sense to focus efforts for improvement on underperforming high volume ofces, stabilizing money order sales at

those locations alone may not be enough to stop the bleeding. Consider this: while the bottom half of post ofces for money order

sales comprised just 6 percent of money order fee revenue in 2015, their plunge in sales was so great that it accounted for more

than a quarter of the overall decline in money order sales since 2012. As such, it may be important to implement some nationwide,

common sense changes that could also help stabilize sales at smaller post ofces.

78 PayPal Help Center, “What are the fees for PayPal accounts?,” https://www.paypal.com/us/webapps/helpcenter/helphub/article/?solutionId=FAQ690.

79 eBay, Should I Accept a USPS Money Order as Payment for an Item?.

80 U.S. Department of Justice, Correctional Populations in the United States, 2014, January 21, 2016, http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpus14.pdf, p. 1. JPay also is a

signicant player in corrections payments, though it works through a partnership with MoneyGram, as is explained here:

http://jpay.com/MoneyGram.aspx.

81 Payments of $1 to $300 made online to the Federal Bureau of Prisons cost $3.95 to $9.95 at Western Union and $5.95 to $9.95 at MoneyGram, according to their online

calculators: https://www.westernunion.com/us/en/inmatehome.html and https://secure.moneygram.com/payBills/payment-options.

82 This includes the approximately 8,000 post ofces in the top 25 percent for money order sales.

Small investments at post ofces

could have a big impact on the

customer experience.

Modernizing the Postal Money Order

Report Number RARC-WP-16-007

18

Executive Summary

Table of Contents

Observations

Appendices

Print

Communicate the Existence of Postal Money Orders as Well as the Advantages of Postal Money Orders and Any

Product Changes

The Postal Service appears to do little, if any, marketing of money orders. Targeted, effective communication could be essential

to the success of money orders and any innovations. If, for example, the Postal Service begins selling money orders through

a mobile app or offering electronic money orders, it could get the word out to existing money order users by passing out cards

explaining the new offerings with every money order sale. Clerks also could be trained to tell all money order customers that they

can now buy money orders from their phones and have them automatically delivered to the biller. In addition, the Postal Service

could notify all My USPS customers and users of the USPS Mobile app of the services. It also could install posters and sales

brochures in post ofces and banner ads on usps.com that explain the advantages of the services, and that tout the benets of

paying with a money order rather than a check or debit card in this age of rampant identity theft. With more than 2 billion annual

visits to post ofces and usps.com, a tremendous number of current and potential money order users could see this information.

83

The Postal Service also could strive to increase billers’ awareness of the advantages of accepting postal money orders as

payment. Many of these communications efforts could be accomplished at minimal cost to the Postal Service.

Perhaps Pursue Money Order Discount Agreements With Prepaid Card Companies

Use of general-purpose reloadable prepaid cards grew by more than 50 percent between 2012 and 2014, with some 23 million

adults regularly using them.

84

Many of these cards effectively serve as a replacement for a checking account, but without checks.

When prepaid users need to make a paper-based payment, many turn to money orders. The Postal Service could negotiate

discount agreements on money orders with prepaid card companies that encourage their customers to use postal money orders —

similar to the postage discounts regularly negotiated with high-volume shippers.

85

These agreements may require approval by the

Postal Service Board of Governors and the Postal Regulatory Commission. The prepaid provider would benet by being able to

offer their customers a new service and by ensuring that their customers use their prepaid card to purchase money orders; prepaid

users would benet by paying less for their money orders; and the Postal Service would benet by becoming the paper-based

payment provider of choice for many users of prepaid cards.

Ramp up Additional Alternative Financial Services Offerings

One of the Postal Service’s shortcomings in the money order space is a lack of compelling complementary products. If the

Postal Service overhauled and expanded its current menu of additional alternative nancial services, including money transfers,

prepaid gift cards, and limited check cashing, it could signicantly benet the many money order users who also use additional

alternative nancial services.

83 U.S. Postal Service, “Size and scope.”

84 The Pew Charitable Trusts, Banking on Prepaid: Survey of Motivations and Views of Prepaid Card Users, June 2015, http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2015/06/

bankingonprepaidreport.pdf, p. 2.

85 There are complex rules surrounding these sorts of agreements, and the Postal Service would need to ensure that the increased volume from prepaid customers makes

up for the cost of the discount.

Effective communication about

the value of any money order

innovations will be essential to

their success.

Modernizing the Postal Money Order