1

Committee on Energy and Commerce

Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations

Hearing on

“In the Dark: Lack of Transparency in the Live Event Ticketing Industry”

February 26, 2020

Ms. Amy Howe, President & Chief Operating Officer, Ticketmaster

The Honorable Diana DeGette (D-CO)

1. At the hearing, you testified that “all consumers have to opt-in for marketing purposes, that’s

regardless of what platform they’re buying on” and that Ticketmaster “cannot use any

information that is acquired from another platform for any marketing purposes.” However,

Ticketmaster’s privacy policy (effective January 1, 2020) (the “policy”) expressly notes that

Ticketmaster collects consumer information, including “from third parties,” and uses this

information “for marketing purposes.” The policy also details how consumers may “opt out

of receiving [Ticketmaster’s] marketing emails,” but is silent on any “opt-in” requirement.

a. Does Ticketmaster define any secondary ticketing websites as “third parties” under

the policy? If yes, please explain how the policy is consistent with your testimony

that Ticketmaster “cannot use any information that is acquired from another platform

for any marketing purposes.”

Secondary ticketing websites are considered third parties under our privacy policy. However, the

response I provided was in the context of the NFL “open ticketing” relationship, in which

Ticketmaster provides ticket validation services to other ticket marketplaces, including Stubhub

and SeatGeek, on behalf of the NFL. As I stated in my testimony, Ticketmaster receives

information about a buyer of NFL tickets from SeatGeek or StubHub, solely to validate and

fulfill their customer’s tickets. This is required under our agreement with the NFL, and

Ticketmaster does not use the information for any other purpose, including marketing unless a

consumer opts-in.

b. If “all consumers have to opt-in for marketing purposes,” why is Ticketmaster’s

policy silent on any “opt-in” requirement?

Ticketmaster’s privacy policy addresses consumers’ privacy rights on Ticketmaster’s website.

My response was in the context of our relationship with the NFL, and my statement referred to

Ticketmaster’s policy of not using consumers’ information from secondary ticketing websites for

marketing purposes without their opt-in consent.

2

c. The policy also states that “if you buy tickets from [Ticketmaster] we'll enroll you in

our newsletter.” Most consumers who purchase tickets through Ticketmaster “opt in”

to receive this newsletter? If not, please explain how the policy is consistent with

your testimony that “all consumers have to opt-in for marketing purposes…”

Consumers who buy tickets on Ticketmaster’s website have the option to opt-out of receiving the

newsletter. The opt-out screen is below. Again, my statement was made in the context of our

specific relationship with the NFL and the marketplaces it has licensed to sell validated NFL

tickets, including Stubhub and SeatGeek.

Where consumers have purchased tickets directly from Ticketmaster’s website, they can

unsubscribe from any marketing email, change marketing preferences in their Ticketmaster

account. Ticketmaster provides robust and meaningful customer privacy protections and is

compliant with both the California Consumer Privacy Act, as well as Europe’s Global Data

Protection Regulation. All of our consumers are able to email our dedicated global privacy team

or opt-out of receiving communications under mechanisms we created to comply with our global

privacy control framework, which provides all consumers, irrespective of location, optionality

and choice as to how their information is used.

3

2. The policy also states that Ticketmaster “will share [consumer] information with our business

partners,” who may “send[] you marketing communications.” It also states that Ticketmaster

“will share information with third parties who sell products or services to you,” such as third

parties who sell “merchandise.”

a. Must consumers first “opt-in” before Ticketmaster shares their data with

Ticketmaster’s “business partners” or other third parties who sell consumer products

or services? If not, please explain how the policy is consistent with your testimony

that “all consumers must opt-in for marketing purposes…”

Consumers have the ability to opt-out of the sharing of their information from the Ticketmaster

website with our business partners and third parties. As indicated in my answer to 1(c) above,

Ticketmaster takes privacy extremely seriously and has invested significantly to ensure we

operate under a global privacy control framework, which provides all consumers, irrespective of

location, optionality and choice as to how their information is used.

3. What types of competitive advantages do brokers have and how do they unfairly

disadvantage average consumers?

4

As I stated in my written testimony, two concepts that create an imbalance within the ticketing

industry are: (1) supply and demand, and (2) pricing. First, for many of the highest-profile

events, the demand from consumers for tickets far exceeds the number of seats available to

purchase. Second, the performing artists often set the prices of these in demand tickets well

below true market value in order to build or maintain goodwill by allowing fans of all income

levels to access tickets.

This creates a lucrative opportunity for players in the ticketing ecosystem to take advantage of a

supply/demand imbalance that mixes with below market prices intended for real fans. This

“arbitrage” opportunity is not small. In 2019, we estimate the secondary concert market to

exceed $10 billion, almost all of which is paid by fans to the benefit of middle men and resale

marketplaces like Stubhub, Vivid Seats, and Ticket Network, not the Event Organizer, artist or

team who paid to produce the event. We believe the vast majority of concert resale activity on

these sites is sold by professional brokers, not individual fans.

This economic incentive results in significant investment in tools by bad actors to capitalize on

this arbitrage opportunity. The most egregious of these tools involves the use of bots, which

programmatically attack the primary market ticket systems with billions of real-time requests to

select and purchase tickets. For some of the highest demand events, this activity is akin to using

a computer to purchase millions of lottery tickets with different numbers while a consumer can

only buy a single ticket. Bots are also used to reserve and hold, not purchase, thousands of

tickets at a time, thereby creating artificial demand by shutting actual consumers out from buying

tickets at face value while driving up prices of comparable tickets on the secondary market.

Bots are able to (i) detect and reserve ticket inventory, often in a matter of seconds; (ii) control

multiple accounts to exploit published ticket limits; (iii) create accounts with false information to

hide the identity of a purchaser; and (iv) harvest data about pricing and consumer demand in

order to aid decision making that drives up the price on the secondary market.

Ticketmaster has made deep and substantial investments in fighting these tactics with a

combination of proprietary tools and technologies as well as implementation of leading third-

party tools such as Distil and IP-based blocking technology. We have also added an additional

layer of security by requiring all newly created accounts on Ticketmaster to employ Two-Factor

Authentication, which makes it more difficult to create single-use accounts in bulk.

The reality of the situation is that, in spite of the passage of the BOTS Act (of which

Ticketmaster was a staunch supporter), the number of bots Ticketmaster has blocked from our

site has continued to grow exponentially, tripling in the time since the BOTS Act was enacted.

According to a 2019 report by Distil, a leading bot-mitigation software provider, 40% of activity

on ticketing sites is computer automated, and up to 67% of bad bot traffic occurs in the United

States.

1

Even worse, Distil reports that bot attacks on primary market platforms like

Ticketmaster is almost double that of attacks on secondary market platforms, further illustrating

the challenge consumers have buying tickets in the first instance at the price set by the Event

1

See Daniel Sanchez, “Nearly 40% of Ticketing Traffic Comes from Bad Bots, Study Finds” (Digital Music News,

Feb. 28, 2019), available at https://www.digitalmusicnews.com/2019/02/28/bots-ticketing-traffic/.

5

Organizer. When blocked from buying face value tickets in the first instance, consumers are

often forced to purchase tickets at inflated prices on the secondary market sites if they want to

attend an event.

Brokers can also disadvantage consumers by selling tickets they do not possess. Speculative

ticketing is essentially a mass-arbitrage scheme employed by some brokers to sell tickets they do

not possess, and, as such, do not have a legal right to sell. Speculative tickets are frequently

offered on secondary marketplaces without disclosure of their speculative nature, often before

tickets have even been placed on sale to the general public by the Event Organizer. These

marketplaces do very little to stop speculative listings placed on their websites. In many cases,

consumers purchase speculative tickets on the secondary market at inflated prices when face

value tickets are still available on the primary market.

The Honorable Brett Guthrie (R-KY)

1. As you know, the Better Online Ticket Sales Act (BOTS Act) was signed into law in 2016.

Neither the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) nor the states have taken any enforcement

action under the BOTS Act. Your testimony notes that “[w]e need enhanced enforcement of

the BOTS Act of 2016.” Can you explain why you think enhanced enforcement is

necessary?

6

a. Would there be a benefit to the consumer if the FTC and states started to take

enforcement actions under this statute? Why or why not?

Bots continue to plague the online ticketing process. Despite passage of the BOTS Act,

unscrupulous actors continue to use bots, depriving real fans of the opportunity to purchase

tickets at the prices set by Event Organizers. In 2019 alone, Ticketmaster blocked nearly 3

billion purchase attempts by bots each month. It is absolutely clear that the prevalence of the use

of bots, even four years after enactment of the BOTS Act, demonstrates the need for more

aggressive enforcement of the law.

In addition to the tens of millions of dollars Ticketmaster has spent fighting bots, we have also

supported legislation at the state and federal levels to ban bots and pursued private legal action

against bot users. Although we have taken such legal action, and we have successfully assisted in

the passage of state level bans on bots, there has been no meaningful deterrence against their

usage. Unfortunately, the economic incentive to utilize bots (further evidenced by the $10B

resale market), still outweighs the risk of an enforcement action. We stand willing and able to

help the Federal Trade Commission, state Attorneys General and other law enforcement agencies

in any attempt to help protect consumers from these bad actors, and to provide the deterrence

necessary to stop what is currently the single biggest impediment to consumers’ fair access to

tickets.

2. Does your company and/or affiliated websites utilize ‘all-in’ pricing and/or an ‘all-in’ pricing

toggle feature? Why or why not?

a. If so, what percentage of your websites and/or affiliated websites utilize ‘all-in’

pricing?

Ticketmaster utilizes “all-in” pricing in almost every country and jurisdiction in which we

operate and are legally required to do so, including Canada, the European Union, Australia, and

New Zealand. Unfortunately, the reality is that, for any single marketplace to avoid being

disproportionately harmed by using all-in pricing, all members of the live event ticketing

industry must be legally required to list all prices and fees up-front. In the absence of this

requirement, consumers cannot make meaningful (apples-to-apples) price comparisons between

marketplaces.

We believe that consumers should be able to see the total cost of their tickets, including all fees,

at the beginning of the purchase process, not only at the end. Requiring all live event ticketing

marketplaces to move to “all-in” pricing (that is, to include all required fees in the price from the

first purchase page), and robust enforcement of that requirement, would prevent price

manipulation, promote transparency, and protect consumers.

As the Government Accountability Office (GAO) concluded “[s]ellers that do not provide

enough or full information on prices through hidden fees could have a competitive advantage

because they would be perceived as offering lower prices over their competitors who do provide

7

full information showing the price.”

2

As a result, Ticketmaster supports legislation that would

require all-in pricing in the United States, and there seemed to be consensus among the witnesses

at the hearing for such a requirement.

3. Your testimony notes that “[s]ome marketplaces also take advantage of the industry practice

of disclosing the fees later in the purchase process to manipulate the list price of the ticket,

making the ticket price appear less expensive upfront.” Please explain what you mean by

that and how that is different than how Ticketmaster discloses its fees to consumers who

purchase tickets on its website.

a. In your opinion, how prevalent is this practice throughout the industry?

Not disclosing fees at the beginning of the purchase process enables a marketplace to manipulate

the list price of a ticket to make such prices appear less expensive upfront, a practice commonly

used in the industry and known as “marking down” tickets. This practice involves reducing a

ticket’s up-front list price, only to add the amount of the reduction into the mandatory fees

charged later in the transaction.

Ticketmaster provided multiple examples of this deceptive practice to the Committee in our

written submission on December 23, 2019.

In one such instance, a resale ticket was offered by a seller for $75. Ticketmaster advertised the

ticket to consumers for $75, and, after 17% in fees, charged a total price of $87.75. A competitor

“marked down” the exact same ticket by 10%, advertising the ticket to consumers for $68, but

then added 36% in fees for a total ticket price of $92.77. Thus, on the competitor’s website, the

ticket was initially presented as less expensive than what was offered on Ticketmaster, when, in

fact, the ticket ended up being 6.5% more expensive after the addition of fees. Based on our

observations, this practice appears to be growing on other resale platforms, comprising a

majority of their ticket listings.

To be clear, Ticketmaster does not engage in the practice of marking down resale tickets and

transferring the difference to fees. Extensive examples of this type of deceptive and egregious

practice meant to trick consumers into paying a higher all-in price were attached to our written

testimony as Exhibit 1, and a recent example from May 12, 2020 appears below.

2

Government Accountability Office, Event Ticket Sales, at 42 (April 2018), available at

https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/691247.pdf (“GAO Report”).

8

4. Does your company or any of its affiliated websites sell dynamically priced tickets?

a. What percentage of overall sales does dynamically priced tickets represent?

Ticketmaster provides a number of tools which enable our Event Organizers to dynamically

price tickets.

Dynamic pricing is a commonly used practice across many industries with perishable

inventory. It allows event organizers to price to market, which can result in ticket prices either

decreasing or increasing. When demand exceeds supply, dynamically pricing the ticket (up)

allows the Event Organizer and artist to capture the true market value of the ticket, money that

would otherwise go to brokers. In situations where supply exceeds demand, particularly in the

last-minute window, dynamically pricing tickets (down) allows the Event Organizer and artists

to sell tickets that they wouldn’t otherwise sell, thereby allowing more fans to purchase tickets to

an event at more affordable prices.

For most high-demand concerts, the percentage of seats being dynamically priced (up to market)

is approximately 5% of the total. Nevertheless, some concert promoters and artists are finding

dynamic pricing to be a much more effective way to increase total gross sales from a show,

while, in some cases, decreasing the average ticket price paid by fans for the rest of the

house. This is accomplished by selling some of the best seats in the house for much more than

they previously would have, which enables them to decrease the price of some of the seats

further away from the stage. What’s important to note, however, is that these market prices are

the same prices fans would have paid for these best seats, they are simply paying the artist (the

SeatGeek applies markdown, pairs with 31% buyer fee; listing

appears 9% cheaper than TM but all-in is more expensive

2

RESALE MARKETPLACE PRICING PRACTICES

Listing Page: ~9% markdown

assuming same seller price as TM

Service fees of 31%

Listing Page: No markdowns

Service fees of 15%

Order processing fee of $2.95

$2,412.20

Seller Price Checkout PriceDisplayed Price

$2095 $2095

0%

+15%

No Markdown, 15% Checkout Fees

$2,095

$2,481.40

Checkout PriceSeller Price Displayed Price

$1900

-9%

+31%

~9% Markdown, 31% Checkout Fees

• Screenshots taken on 5/9/20 at the same time to avoid confusing pricing adjustments by seller with marketplace markdowns

• Each marketplace had only one listing of five tickets in that section and row, so no chance comparison is between different listings

9

IP owner) rather than a middleman. Over time, as artists continue to make the majority of their

income from touring, and as live events become increasingly expensive to produce, we anticipate

more concerts will use dynamic pricing to recapture economics that were previously lost to

secondary resellers.

The practice of dynamic pricing is more prevalent in the sports industry, where teams use a

variety of tools and practices, including selling tickets to professional sellers to increase

distribution. In the case of sports, mid-week games against weaker opponents may be

dynamically priced lower, whereas weekend games against playoff contenders may yield higher

prices.

b. Are tickets that are held back at the on-sale by the artist, promoter, venue, etc. later

posted for sale as dynamically priced tickets rather than face value?

In the vast majority of cases, the number of seats truly “held back” by an artist is extremely

small, currently averaging approximately 5% or less of the total seats being made available for

sale to consumers. These seats allow the Event Organizer or artist to allocate tickets for

marketing and promotion, sponsors, VIPs, and to family, friends, sponsors, and crew and even to

address production issues that impact seats.

It is possible that, for any given event, these tickets could be opened for sale to the public and

priced dynamically. That decision would be made by the Event Organizer, and would be affected

by a number of variables, including the quality of the seats, the demand for the event, the time to

the event, and the available supply of similar tickets. Since demand for tickets is typically

highest at the on-sale, Event Organizers are not rewarded for holding back tickets that would

otherwise sell at market clearing prices during the highest demand sales window. Tickets that are

released late in the sales cycle are typically priced at face value to ensure they are sold by show

time.

In any and all cases, as a platform, it is our strong belief that pricing and inventory management

decisions should be the sole right of the Event Organizer, the rights holder who has developed

their intellectual property, paid rent to the facility, and paid for all the staffing and production

required to perform. These decisions should not be made by ticketing platforms or anyone else

who does not own the IP nor has taken any risk to create the event in the first place.

c. Does your company or any of its affiliated websites make disclosures to consumers

when a ticket is dynamically priced, and what that means? If so, what does that look

like?

Yes, we disclose in our “Pricing and Availability FAQs” and our “What ae Official Platinum

Seats?” FAQs that prices are subject to change and may be priced dynamically. Screen shots are

included below.

10

11

5. Your testimony notes that you believe “that not only would mandatory inventory disclosure

not help fans get fair access to tickets, but it would likely create more challenges for fans.

Why do you believe this type of disclosure would likely create more challenges for fans?

12

a. What do you believe would be more helpful to fans?

Although some in the industry have attempted to argue that the biggest threat to fair access for

consumers is not knowing how many tickets are made available for sale, this argument is non-

sensical. As we stated, lack of access to primary tickets is created by high-demand and/or bots,

not because tickets are being held back by Event Organizers.

Despite arguments to the contrary, Event Organizers do not have a financial incentive to hold

back tickets because Event Organizers generate the most revenue during the primary on-sale. As

a result, mandating inventory disclosure would not increase the availability of tickets for real

fans. Even the recent GAO Report noted it was “[u]nclear how useful [inventory disclosure]

information is for consumers.”

3

Ironically, our standard practice of showing all available inventory has already proven

to make it even harder in some cases for consumers to access tickets as it makes it much easier

for unethical brokers and bot users to determine the demand profile of an event. In doing so,

these entities are able to more effectively target supply and manipulate the market by using

Ticketmaster’s pricing data to set higher prices on the secondary market.

A particularly egregious practice that relies on the misuse of an event’s inventory availability is

commonly known as “mirroring.” In this scheme, brokers search primary marketplaces using

computer automation to determine what tickets are available. With this information, these bad

actors falsely represent all available primary seats as valid resale listings, but at prices often well

above face value. Only after an unwitting consumer purchases one of the speculative ticket

listings does a seller buy the tickets in the primary market to fulfill the order.

3

Id. at 36.

13

In other cases, certain brokers use products such as TicketFlipping (a subscription-based service

for professional resellers available at www.ticketflipping.com) to actively scrape primary and

secondary ticketing marketplaces and notify sellers how many tickets are still available for an

event, what types of tickets are available, and at what prices. The very fact that professional

resellers are willing to pay for this information suggests that this information is extremely

valuable, and that it can be used to manipulate ticket prices on the secondary market. Put simply,

inventory disclosure does not provide fans with better access to seats; it provides unscrupulous

STUBHUB MIRRORING PRIMARY INVENTORY

NO TICKETS HAVE BEEN SOLD IN REAR MEZZANINE RIGHT SIDE

4

STUBHUB MIRRORING PRIMARY INVENTORY

24 SEATS DISPLAYED IN REAR MEZZANINE RIGHT SIDE

5

14

actors with a roadmap regarding how many seats are available and how they can leverage

inventory information to charge higher prices to fans on the secondary market.

6. Your testimony notes that beginning in 2018, Ticketmaster started including links on its site

to third party primary ticketing sites for many concerts and theater events where

Ticketmaster is not the official ticket marketplace. Why did Ticketmaster start doing this and

what percentage of events does this apply to?

As I mentioned in my testimony, these links permit a fan browsing Ticketmaster’s concert and

theatre ticket inventory to compare prices for secondary tickets listed for sale on Ticketmaster’s

resale platform with primary tickets listed for sale even by competitors. We believe fans should

know if they are buying primary or resale tickets and from whom they are buying tickets. It’s

why we differentiate those tickets on our main pages and why we are clear and link out to third

party websites when we are not the primary provider. We are not aware of ANY other

marketplace that does either of these things. Ticketmaster encourages other resale ticketing

platforms to implement similar procedures to offer fans links to official box offices alongside

their resale inventory. The implementation and frequency of this practice has varied over time.

7. Approximately what percentage of events that your company sells tickets for have tickets

that are non-transferrable

a. Your testimony notes that the vast majority of artists have historically chosen not to

restrict transfer and you think that trend is likely to continue. Why is that?

Ticketmaster confidential. Do not distribute.

4

Clicking on “see tickets” links to venue box office link out

15

For calendar years 2016, 2017 and 2018, the percentage of tickets sold via Ticketmaster with

transfer limitations was 1.8%, 0.8% and 0.2%, respectively. In all cases, we believe it is in the

Event Organizer’s sole discretion to determine how tickets are distributed and the rules by which

they can be transferred. As stated above, the Event Organizer owns the IP and has taken all costs

and risk for the event as a such, if the tickets are non-transferable, we see no reason they should

not be able to do so.

To be clear, however, the primary use case for limiting the transferability of tickets is to ensure

tickets will be more affordable for consumers. By making tickets non-transferable, Event

Organizers and artists can ensure that the person who purchases the ticket is a true fan who plans

on attending the event, not someone who is buying for the sole purpose of reselling that ticket,

likely at an inflated price. As reference to this point, the GAO Report noted that restricting

Event Organizers from limiting the transferability of tickets reduces the “opportunity for

consumers to access tickets at lower-face value price.”

4

As one example, on January 13, 2020, Pearl Jam announced that tickets for its Gigaton tour

would be non-transferable. The band made this decision to provide consumers access to their

tickets at below-market prices, thereby preventing consumers from paying inflated prices on the

resale market. The limitation on transferability of these tickets has been fully disclosed to

consumers, with extensive communication to fans throughout the announcement and the sales

process on Ticketmaster.

For fans who are ultimately unable to attend the concert, Ticketmaster has developed a first-of-

its-kind, Fan-to-Fan Face Value Ticket Exchange (“Exchange”), where fans can sell their tickets

for the amount they originally paid (including face value of $98, a $5 charitable amount and

service charge), to other fans. To eliminate consumer confusion, Ticketmaster also notified

major secondary marketplaces and resellers that tickets for this tour are not available for resale.

This technology has accomplished exactly what Pearl Jam was seeking to do. For the ten Pearl

Jam shows in states that permit artists to restrict transfer, approximately 18,000 tickets per show

were sold at face value, with fewer than 10 resale tickets per show listed on secondary markets.

However, in Colorado and New York, the two states that prohibit any limitations on

transferability of a ticket, thousands of tickets are available on secondary marketplaces for prices

as high as $7075 per ticket, more than a 7000% increase over intended face value.

We are very proud to have partnered with Pearl Jam on a product that enabled the band to

provide fair and easy access to their very best fans, while still giving consumers flexibility in the

event they cannot attend. While a decision about transferability is an individual choice that each

artist will make, we reiterate that, in our experience, the vast majority of artists have historically

chosen not to restrict transfer as any restriction or limitation could impede sales. So to the

contrary, the use cases we often see that involve a request for non-transferability are limited to

the most highly in demand shows where demand far exceeds supply and where the artist/content

owner wants to ensure their true fans get access to tickets at well below market prices.

4

Id.

16

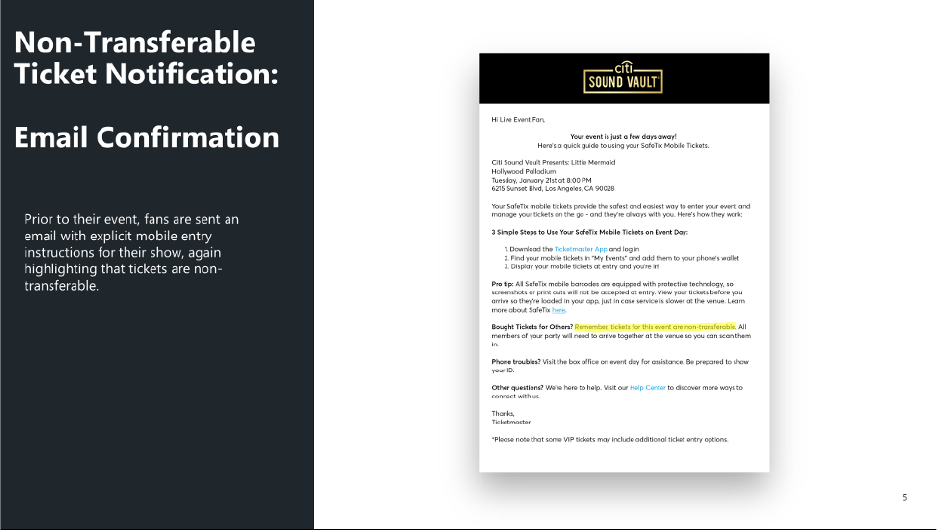

8. In the event that your company sells tickets that are deemed non-transferable, what efforts

are taken to ensure that consumers and secondary marketplaces are aware that the tickets are

non-transferrable to avoid confusion and frustration down the road?

a. If you make attempts to notify the secondary market that an event has non-

transferrable tickets, what response do you typically receive? Do you generally still

see the secondary marketplaces posting those tickets?

As discussed above, we believe it is in the Event Organizer’s sole discretion to determine how

tickets are distributed and the rules by which they can be transferred. If an artist wants to make

tickets more affordable for his/her fans by designating their tickets non-transferable, we see no

reason they should not be able to do so. However, we also believe that any limitations should be

clearly disclosed prior to purchase so consumers have the information needed to make an

informed purchasing decision.

On the Ticketmaster marketplace, consumers are informed of the non-transferable nature of

tickets on the first page of the transaction process, again before checkout, and in confirmation

and event-reminder emails. In addition, if an Event Organizer designates an entire event as non-

transferable, we notify other marketplaces via email before the event’s primary on-sale. We

typically receive an acknowledgement of the non-transferability of an event, and such other

marketplaces generally do not subsequently post tickets for that event.

17

9. Your testimony notes that Ticketmaster “conducts a thorough process to police the site and

remove suspect listings. Can you describe this process?

a. Approximately how many suspect listings does Ticketmaster find on its site annually?

Ticketmaster has a stringent policy against posting tickets the seller does not actually possess and

a thorough process by which we police our site and remove suspect listings. In order to enforce

Ticketmaster’s ban on speculative tickets, we’ve implemented a multi-phased approach

described below, which resulted in Ticketmaster removing approximately 160,000 tickets in

2019:

• The Ticketmaster system precludes sellers from posting tickets for sale that do not have a

barcode when Ticketmaster is the primary ticketer. This means that there can be no

speculative listings in the Ticketmaster marketplace for events where Ticketmaster is the

primary ticketer.

• In addition, we actively monitor for and input into the Ticketmaster system the public on-

sale date for all events on our marketplace, including those where we are not the primary

ticketing company. If a posting is attempted on an event before it has gone on sale to the

general public, the system will deny the posting. In addition, Ticketmaster employs a full-

time employee, dedicated solely to monitoring our site for speculative and other

suspicious listing

18

• If a speculative listing is found, the listing is removed. The person who posted the ticket

is automatically notified and asked for proof of ownership for the ticket. If the person

can provide proof of ownership, the tickets are reinstated.

• All incidents are logged, and an email file is sent to Ticketmaster’s Legal department on a

weekly basis, specifying the number of speculative tickets removed.

10. Your testimony notes that although you believe a ban on speculative tickets would best

protect consumers, if speculative ticketing continues to be permitted, federal legislation

should include requirements for clear and conspicuous disclosure at the beginning of the

ticket purchase process.” In your opinion, what requirements are needed?

We believe that an outright ban on speculative tickets is best for consumers. It is deceptive

marketing to list a ticket, or any item, for sale when a seller has no legal right to the ticket and no

guarantee they will have the ticket in the future. Fans who buy speculative tickets often do not

realize they have only purchased the right to buy tickets if the seller is able to acquire them and

may have their “tickets” canceled if the seller cannot deliver or, they may end up with different

seats than those the fans believed they had secured.

If speculative ticketing continues to be allowed, requiring clear and conspicuous disclosures can

help protect unwitting consumers. These disclosures should include information that (1) the

seller does not yet have the tickets in hand and will attempt to purchase the tickets for the

consumer, (2) the seller does not have a contract to obtain the offered ticket at a certain price

from the person in possession of the ticket (or the person who has a contractual right to obtain

the ticket), and (3) there is a risk the tickets may be replaced with another ticket, or may not be

delivered at all.

These disclosures should be coupled with a mandatory refund if tickets are not fulfilled, and an

option for the consumer to choose a refund if replacement tickets are not to the consumer’s

liking.