Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics

Volume 14 Article 8

2021

An Examination of Secondary Ticket Market Pricing Trends and An Examination of Secondary Ticket Market Pricing Trends and

Determinants at the NCAA Football Bowl Subdivision Level Determinants at the NCAA Football Bowl Subdivision Level

Stephen L. Shapiro

University of South Carolina

Austin Schulte

University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill

Nels Popp

University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill

Brad Bates

University North Carolina – Chapel Hill

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/jiia

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Shapiro, Stephen L.; Schulte, Austin; Popp, Nels; and Bates, Brad (2021) "An Examination of Secondary

Ticket Market Pricing Trends and Determinants at the NCAA Football Bowl Subdivision Level,"

Journal of

Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics

: Vol. 14, Article 8.

Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/jiia/vol14/iss1/8

This Original Research is brought to you by the Hospitality, Retail and Sports Management, College of at Scholar

Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics by an authorized

editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected].

Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics, 2021, 14, 194-213 194

© 2021 College Sport Research Institute

Downloaded from http://csri-jiia.org ©2021 College Sport Research Institute. All rights reserved.

Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

An Examination of Secondary Ticket Market Pricing Trends and Determinants

at the NCAA Football Bowl Subdivision Level

__________________________________________________________

Stephen L. Shapiro

University of South Carolina

Austin Schulte

University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill

Nels Popp

University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill

Brad Bates

University North Carolina – Chapel Hill

________________________________________________________

Several factors influence the price college athletics administrators set for football tickets, but

nearly all pricing decisions are established prior to the season commencing. The secondary

ticket market allows college athletics administrators to observe real-time consumer valuation for

tickets. The purpose of the current study was two-fold: (a) to examine how secondary ticket

market prices fluctuate at different time periods leading up to game day and (b) to examine the

relationship between several key demand variables and “Get In” price (GIP) during those

different time periods. To conduct this study, individual game GIPs were collected from StubHub

for all Power 5 home contests (N = 434) for the 2019 football season at four different time

periods; (a) pre-season, (b) two weeks before game day, (c) one week before game day, and (d)

the day before game day. Four categories of explanatory variables--(a) time/environmental

factors, (b) game-related factors, (c) performance factors, and (d) home market factors--were

also collected. Four regression models were conducted, predicting between 38.9% and 70.5% of

the variance in GIP at each point in time. As game day grew closer, overall GIP diminished in a

linear fashion at each data collection. Several explanatory variables were significant in each

model and are interpreted in the discussion.

1

Shapiro et al.: An Examination of Secondary Ticket Market Pricing Trends and Dete

Published by Scholar Commons, 2021

Secondary Ticket Market Pricing

Downloaded from http://csri-jiia.org ©2021 College Sport Research Institute. All rights reserved.

Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

195

icket sales have long been a major source of revenue for collegiate athletics

departments. College football, in particular, generates significant revenue from ticket sales. The

top 25 college football programs generated annual revenues of over $2.7 Billion in 2018, and

27% ($729 million) of that revenue is a result of football ticket sales (Smith, 2019). Berkowitz

(2020) suggested the total football ticket revenue for all of Power 5 schools exceeded $1 billion

in 2019, while sport economist Patrick Rishe estimated Power 5 schools would have generated

an average of $18.6 million in football ticket sales in 2020 had the coronavirus pandemic not

struck (Schlabach & Lavigne, 2020). According to the NCAA Finances of Intercollegiate

Athletics Database, 17.5% of all revenue (generated and institutional support in FY 2019) came

from sport ticket sales at FBS Autonomy institutions (Power 5 universities), with the large

majority of those sales stemming from football (NCAA, 2020). Recently, ticket sales in

professional team sports have undergone a major overhaul with new technology enabling sport

marketers to learn better ways to maximize revenue. Charging the same price for every seat—

and against every opponent--is no longer the most efficient way to sell tickets. Variable and

dynamic ticket pricing strategies have led the way in promoting smarter, more efficient pricing

approaches to create additional revenue (Shapiro & Drayer, 2012). From a college football

perspective, it has never been more important for athletic departments to accurately price their

catalog of events to produce revenue.

Traditionally, the predominant method for establishing ticket prices to live sporting

events has been to raise prices incrementally over time by some arbitrary percentage or flat rate

(Howard & Crompton, 2004). However, more recent scholarship has highlighted the positive

impact of demand based pricing, including variable ticket pricing (Rascher, McEvoy, Nagel, &

Brown, 2007), dynamic ticket pricing (Shapiro & Drayer, 2012, 2014), and other forms of

discriminant pricing (Courty, 2003) that have been used in professional sport. These pricing

strategies are largely in response to the secondary ticket market, which highlights inefficiencies

in the primary market, particularly in high demand environments (Drayer, Shapiro, & Lee,

2013). According to Drayer et al., sport organizations typically underprice tickets due to the

desire to increase attendance, increase ancillary sales, and create a better atmosphere at the

stadium. Additionally, sport organizations want to avoid perceptions of price gouging for high

demand events. The resale market capitalizes on these factors to create arbitrage opportunities.

Thus, research on ticket pricing in the resale market has become more prevalent (Diehl, Maxcy,

& Drayer, 2015; Diehl, Drayer, & Maxcy, 2016; Shapiro & Drayer, 2014). The majority of the

strategic pricing research has been conducted within the context of professional sport. Our

understanding of ticket pricing within the realm of college sport, and the inefficiencies in a dual-

market environment such as college football, is limited.

Although some athletic departments are using demand-based pricing strategies for

college football, these strategies are not consistent across all programs, further highlighting the

need to investigate ticket prices across markets. College sport, and football in particular, presents

some unique challenges with regards to ticket pricing. These challenges include the vast number

of teams, competing in various divisions and conferences, each with differing policies and

guidelines. Additionally, the revenue disparity is dramatic. In 2017-2018, there was a disparity of

approximately $203.4 million between the Division I Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) program

that generated the most revenue (University of Texas: $219 million) and the program that

generated the least revenue (University of Louisiana-Monroe: $15.6 million) (Berkowitz, Wynn,

T

2

Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics, Vol. 14 [2021], Art. 8

https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/jiia/vol14/iss1/8

Shapiro, Schulte, Popp & Bates

Downloaded from http://csri-jiia.org ©2021 College Sport Research Institute. All rights reserved.

Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

196

& McManus, 2019). Finally, stadium capacity and demand for football tickets varies

considerably with the largest college football stadiums seating over 100,000 fans and regularly

selling out, while other programs have stadiums that hold fewer than 15,000 fans with no

sellouts.

A handful of studies have either examined managerial theory associated with pricing

strategy or secondary price markups in postseason play within college athletics (Morehead,

Shapiro, Madden, Reams, & McEvoy, 2017; Rishe, Mondello, & Boyle, 2014; Rishe, Reese, &

Boyle, 2015; Rishe, Sanders, Reese, & Mondello, 2016). Price disparities in the primary and

secondary market, and factors that influence resale price during the college football regular

season, however, have not been examined. Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to

compare Division I FBS college football ticket prices across markets and determine which

factors influence resale prices. Developing a model focused on ticket price disparities and resale

determinants in college football will extend our knowledge on sport pricing in general, while

advancing marketing and management theory within a diverse, non-profit, commercialized sport

environment.

The following research questions were developed to guide this investigation:

RQ 1: How does resale “get-in” ticket price change over time periods from the

Associated Press Poll release to the day before the game?

RQ 2: What variables predict Power 5 resale “get-in” price at various time periods

leading up to game day?

Literature Review

Pricing Theory in College Sport

Optimal pricing strategies are important for sport organizations to avoid pricing too low

and losing potential revenue, or pricing too high and either driving fans away or being perceived

as price gouging (Shapiro & Drayer, 2012). The secondary ticket market has dramatically shifted

pricing strategy in sport from a cost-based to demand-based focus (Drayer et al., 2013). Two

common theories that have guided the ticket pricing literature are price discrimination (Rosen &

Rosenfield, 1997) and revenue management (Kimes, 1989; Shapiro & Drayer, 2012).

Price discrimination, or charging different prices to different consumers, is a common

practice in industries where costs do not significantly change with the addition of customers.

Rosen and Rosenfield (1997) and Courty (2003) suggest price discrimination is effective in the

live entertainment ticket market, where filling some additional seats in a facility has negligible

costs, demand fluctuates throughout the sales period, and perceived value for tickets varies

considerably. The effectiveness of price discrimination in maximizing sport ticket revenue has

been demonstrated in the literature through variable ticket pricing (VTP) based on fixed factors

such as opponent, day and time of the game, or in-game promotions (Rascher et al., 2007).

Researchers have also suggested sport organizations may take financial advantage of price

discrimination by not releasing all event tickets simultaneously, but rather holding back some

tickets to be sold at higher price points since buyers who purchase closer to the event have been

shown to be willing to pay a premium (Courty, 2003; Popp, et al., 2020).

3

Shapiro et al.: An Examination of Secondary Ticket Market Pricing Trends and Dete

Published by Scholar Commons, 2021

Secondary Ticket Market Pricing

Downloaded from http://csri-jiia.org ©2021 College Sport Research Institute. All rights reserved.

Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

197

Revenue management (Kimes, 1989), allows for price discrimination in real-time. In

industries where demand fluctuates daily and the product is perishable, revenue management

provides the opportunity to adjust prices based on instant changes in demand (Kimes 1989;

Kimes, Lee, & Ngonzi, 2015). Shapiro & Drayer (2012), examined the effectiveness of revenue

management in sport by examining dynamic ticket pricing (DTP). Results showed DTP closed

the pricing disparity gap by as much as 60% between the primary and secondary market in Major

League Baseball (MLB). Sport organizations can use revenue management to capture additional

revenue by closing the gap between fixed primary and demand-based resale prices.

These theoretical frameworks are appropriate across the sport ticket spectrum, but the

college sport environment presents a unique context due to its non-profit nature and connection

to an academic institution. Price optimization may not be the only motive in this context.

Morehead et al. (2017) conducted an extensive conceptual examination of the college sport ticket

landscape. They suggested two theories, stakeholder theory and institutional theory, are

instrumental in explaining sources of influence in this environment. Freeman (1984) identified a

stakeholder as “any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the

organization’s objectives” (Freeman, 1984, p. 46). Hester, Bradley, and Adams (2012),

suggested “each component of a firm’s operation is influenced by stakeholders because they

fund, design, build, operate, maintain, and dispose of the systems for which they belong.”

College athletics departments have a vast array of stakeholders, which makes their diverse

influence much more challenging to integrate into pricing strategy. Morehead et al. suggest

athletic departments identify and segment constituents in order to more effectively inform

pricing strategy.

Institutional theory reflects pressures of political influence and cultural expectations

(Morehead et al., 2017). Organizations imitate the actions of others who have achieved success

and, through socialization via professional, educational, or networking connections, devise

pricing strategies. Stakeholder theory looks to those who have influence directly on the

organization, while institutional theory proposes sport teams utilize external influences to set

pricing. Administrators have to carefully balance maximizing revenue with an obligation to not

outprice their stakeholders and fans. Every pricing decision, although an internal decision, is

influenced by external factors. Additionally, these internal decisions, such as a required donation

in order to purchase season tickets, have an impact on pricing strategy. Overall, these theories

have served as a foundation for understanding pricing strategy and consumer response to price in

commercialized spectator sport.

Pricing in Sport

Early sport pricing research focused on the foundational factors influencing price in

professional sport. Reese and Mittelstaedt (2001) discovered the most important factors National

Football League (NFL) teams use to price tickets were team performance from the previous

season, revenue needs of the organization, public relations issues, price sensitivities of the

market, fan identification, and average league ticket price. Rishe and Mondello (2003) extended

the pricing determinants literature through an analysis of factors that impact season price

changes for teams over time. Findings showed differences in team performance, fan income,

population, and playing in the first year of a new stadium influenced ticket prices across teams.

Additionally, changes in win percentage from the previous season, reaching the conference

championship game, playing in the first year of a new stadium, and the size of the previous

4

Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics, Vol. 14 [2021], Art. 8

https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/jiia/vol14/iss1/8

Shapiro, Schulte, Popp & Bates

Downloaded from http://csri-jiia.org ©2021 College Sport Research Institute. All rights reserved.

Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

198

year’s price increase, impacted seasonal changes in average ticket prices. Rishe and Mondello

(2004) conducted a subsequent examination across the four major sports leagues in the U.S. The

findings were generally consistent with previous literature, as price was influenced past prices

and team performance, along with playing in a new facility and fan income. Additionally, by

extending this work beyond the NFL, the authors found population size played a role in all other

major professional sport leagues.

These seminal ticket price determinant studies were conducted prior to the wide

implementation of demand-based pricing strategies, such as VTP and DTP. Subsequently,

Rascher et al. (2007) examined VTP in MLB and found the strategy would have generated an

additional $590,000 in ticket revenue per year for each team. Differential pricing strategy is an

effective method for generating additional revenue, but the structure of this strategy could yield

different price determinants.

Additionally, with the emergence of StubHub and other resale ticket markets, teams have

been forced to change their strategies (Drayer et al., 2013). StubHub captures the capricious

nature of demand and is the most accurate representation of consumers’ willingness to pay for a

particular event. The prices can change drastically for a variety of reasons such as team success,

injuries, opponent success, weather, and coaching changes, amongst other factors.

Drayer and Shapiro (2009) provided an early assessment of factors affecting ticket resale

prices, which include factors that change over time and provide a better reflection of consumer

ticket value. Their study on NFL playoff ticket prices highlighted some factors consistent with

previous research in the primary market, including team performance, population, and income.

However, new variables not considered in primary market models were also found to be

significant, including total number of transactions, time, day of the game, playoff round, and face

value of the ticket. Many of these variables are unique to the secondary ticket market and

provide a better representation of consumer demand. For example, this study was one of the first

to suggest ticket price decreases as the game draws near.

Pricing research evolved as pricing strategy continued to shift to respond to the secondary

ticket market. Shapiro and Drayer (2012, 2014) examined the impact of DTP in MLB through an

examination of the San Francisco Giants inaugural implementation of the strategy. They found

DTP significantly reduced the pricing inefficiency gap between the primary and secondary

market, and confirmed the general trend of price decreases as an event draws near (Shapiro &

Drayer, 2012). Additionally, a concurrent examination of ticket price determinants in the primary

and secondary market showed team and individual performance, day of the game and time

played a significant role in both markets. However, ticket availability and number of days before

the game had a differing impact in the resale market, with largest fluctuations in price as the

game draws closer and constant ticket availability in the marketplace impacting resale price.

Ticket pricing strategy and determinants in a demand-based dual market environment has

been extended to the NFL (Diehl et al., 2015, 2016) and the Premier League (Kemper & Breuer,

2016), and has focused on topics such as DTP premiums (Paul & Weinbach, 2013) and price

dispersion (Watanabe, Soebbing, & Wicker, 2013). These studies have all shown the resale

market plays a significant role in how tickets are priced and what factors impact those prices in a

demand-based environment. However, as mentioned previosuly college athletics presents some

unique marketplace challenges that may influence pricing staregy and the relationship between

primary and secondary markets.

5

Shapiro et al.: An Examination of Secondary Ticket Market Pricing Trends and Dete

Published by Scholar Commons, 2021

Secondary Ticket Market Pricing

Downloaded from http://csri-jiia.org ©2021 College Sport Research Institute. All rights reserved.

Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

199

Pricing in College Sport

The research focused on ticket pricing in college sport is limited, but there are some

foundational studies providing direction within this context. Patrick Rishe and colleagues

conducted multiple studies examining resale markups for postseason Division I college football

and basketball games. Rishe (2014) examined NCAA Final Four tickets on the secondary market

and found tickets were priced in the inelastic portion of the demand curve. Additionally, specific

sessions (i.e., Semifinals instead of an all session pass) had significantly higher markups and seat

location was a significant factor in markup size. Rishe et al. (2014) extended this work and found

team quality and university proximity to the Final Four location increased ticket resale price

substantially.

Rishe et al. (2015) examined trends in secondary market ticket prices for college football

bowl games and the Bowl Championship Series Championship game. Results showed inelastic

pricing of tickets. Seat location and proximity to the game site increased markups as well. Rishe

et al., (2016) expanded the college football postseason investigation by examining 55 different

bowl games. They found consistent results regarding seat quality and university proximity to

bowl game site, but interestingly not all bowl games were priced in the inelastic range of

demand. This is most likely due to the large number of bowl games with a wide range of

competitiveness and quality of opponents. In another study examining factors affecting what

ticket buyers were willing to spend on the secondary market for tickets to attend a major college

basketball tournament (Popp et al., 2018), the time in advance of when tickets were purchased

and the number of regular season games attended both had a negative relationship with the

amount paid per ticket, while age and income level of the ticket buyer, as well as seat location

and number of prior tournaments attended all had a significant positive relationship with amount

paid. These studies provide a fundamental understanding of resale price behavior in college

sport. However, these studies were limited to postseason play and focused on a few price

determinants. More depth regarding team performance, ticket, time, and market-oriented factors

are needed to provide a comprehensive view of resale prices in FBS level college sport.

Method

Sampling Frame

The sample for the current study included all NCAA institutions with football teams in

the Power 5 FBS conferences including Notre Dame. During every week of the 2019 college

football season, approximately half of the teams hosted a home football game. Neutral site

games, such as the Chick-Fil-A Kickoff or Georgia-Florida rivalry in Jacksonville, Florida, were

not included as the games were not true home games, despite one team designated as the home

squad. The sample allowed for an adequate comparison of primary and secondary market prices

in an environment where resale is common.

Variables

The main variable of interest in this study was ticket price, reflected in both the primary

and secondary markets. The primary ticket price collected for this study was the lowest ticket

price offered to the public from the official athletic department website, sans any special

6

Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics, Vol. 14 [2021], Art. 8

https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/jiia/vol14/iss1/8

Shapiro, Schulte, Popp & Bates

Downloaded from http://csri-jiia.org ©2021 College Sport Research Institute. All rights reserved.

Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

200

promotions or deals. Universities sell single game tickets to the public, typically throughout the

summer before the season, once they have exhausted season-ticket sales. Single game tickets can

also become available (and sold) when an unsold portion of tickets allotted to the visiting team

are returned. This typically occurs close to game day.

The secondary market price consisted of the StubHub “get-in” price (GIP) for each

individual game, which was the lowest priced ticket on the resale platform at the time of data

collection. GIP was collected on StubHub at four different time periods: (a) during the pre-

season Associated Press (AP) Poll release, (b) two weeks prior to game day, (c) one week prior

to game day, and (d) one day prior to game day. Neither athletic department price nor StubHub

price included transaction or shipping fees.

In addition to ticket prices, a multitude of explanatory and control variables were

collected for the study. Based on prior literature, four categories of variables were included: (a)

time/environmental factors, (b) game-related factors, (c) performance factors, and (d) home

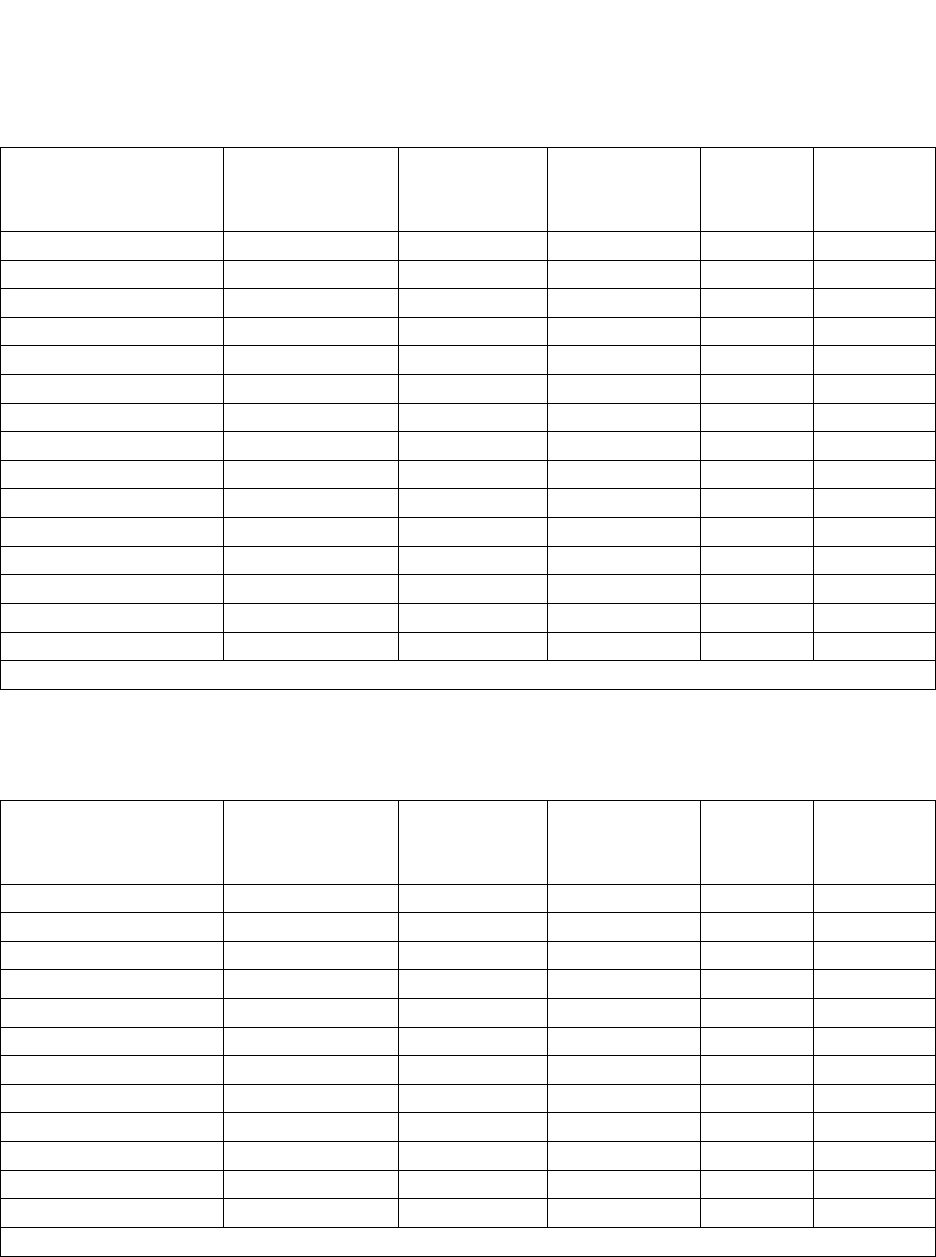

market factors. Table 1 provides a detailed overview of all variables in this study.

Time/environmental variables included: (a) time-related variables (i.e., month, day, and time of

game), (b) proximity of opponent, and (c) weather-related variables (temperature and

precipitation). Game-related factors included (a) whether the game was nationally televised, (b)

conference affiliation for both teams, (c) whether the game was a conference or division

matchup, and (d) betting related factors (betting line and total points). Performance factors

included (a) current and previous year winning percentage for both teams in a matchup, (b) poll

rankings for each team at the time of ticket price observation (using the Massey Rating

Composite Ranking), (c) whether either team in a given matchup went to a bowl game in the

previous year, and (d) recruiting rankings for each team in a matchup. Finally, home market

factors included (a) primary market ticket price, (b) venue capacity, and (c) institutional

enrollment for the home team.

Table 1

List of Variables, Sources, and Justification

Variable Name

Variable Definition

Source

Citation/Justification

DEPENDENT VARIABLES – RESALE TICKET PRICES (GIP)

STUBINITIAL

StubHub prices of the

game when the AP Poll

is first released

StubHub

(Popp et al., 2018); (Shapiro & Drayer,

2012); (Drayer & Shapiro, 2009); (Kemper

& Breuer, 2016)

STUBTWO

StubHub prices of the

game on two weeks prior

to game day.

StubHub

(Popp et al., 2018); (Shapiro & Drayer,

2012); (Drayer & Shapiro, 2009); (Kemper

& Breuer, 2016)

STUBWK

StubHub prices of the

game on Monday of

game week.

StubHub

(Popp et al., 2018); (Shapiro & Drayer,

2012); (Drayer & Shapiro, 2009); (Kemper

& Breuer, 2016)

STUBDAY

StubHub prices of the

game one day prior to the

game date.

StubHub

(Popp et al., 2018); (Shapiro & Drayer,

2012); (Drayer & Shapiro, 2009); (Kemper

& Breuer, 2016)

TIME/ENVIRONMENTAL VARIABLES

MONTH

Categorical variable

indicating the month of

the game.

Team Websites

(Paul, Humphreys, & Weinbach, 2012);

(Shapiro & Drayer, 2012)

7

Shapiro et al.: An Examination of Secondary Ticket Market Pricing Trends and Dete

Published by Scholar Commons, 2021

Secondary Ticket Market Pricing

Downloaded from http://csri-jiia.org ©2021 College Sport Research Institute. All rights reserved.

Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

201

DAY

Day of the game

Team Websites

(Drayer & Shapiro, 2009); (Shapiro &

Drayer, 2012); (Falls & Natke, 2016); (Paul

et al., 2012)

WEEK

Week of the season

ESPN.com

Organization

TIME

Time of kick off

Team Websites

(Shapiro & Drayer, 2012); (Falls & Natke,

2016)

PROXMITY

Distance away team had

to travel to the venue in

miles

Google Maps

(Popp et al., 2018); (Falls & Natke, 2016)

TEMPWK

High temperature

(Fahrenheit) on game day

measured on Monday

before game.

Weather.com

(Falls & Natke, 2016); (Shapiro & Drayer,

2012)

TEMPACTUAL

High temperature

(Fahrenheit) on game day

measured one day prior

game.

Weather.com

(Falls & Natke, 2016); (Shapiro & Drayer,

2012)

PRECIPWK

Chance of precipitation

on game day measured

on Monday before game.

Weather.com

(Falls & Natke, 2016); (Shapiro & Drayer,

2012)

PRECIPACTUAL

Chance of precipitation

on game day measured

one day prior to game

day.

Weather.com

(Falls & Natke, 2016); (Shapiro & Drayer,

2012)

GAME RELATED VARIABLES

HOMECONF

Categorical variable

indicating the conference

of home team.

NCAA Conferences

(Falls & Natke, 2016); (Price & Sen, 2003);

(Paul et al., 2012)

AWAYCONF

Categorical variable

indicating the conference

of the visiting team.

NCAA Conferences

(Falls & Natke, 2016); (Price & Sen, 2003);

(Paul et al., 2012)

CONF

Conference Matchup

NCAA Conferences

(Falls & Natke, 2016); (Price & Sen, 2003);

(Paul et al., 2012)

DIVISION

Division Matchup

NCAA Conferences

(Falls & Natke, 2016); (Price & Sen, 2003);

(Paul et al., 2012)

TV

National television

broadcast status

ESPN.com

(Price & Sen, 2003); (Howard & Crompton,

2004); (Shapiro, Drayer, & Dwyer, 2016)

LINE

The betting line between

the two teams

ESPN.com

(Paul et al., 2012)

TOTAL

Total number of points

predicted between the

two teams.

ESPN.com

(Paul et al., 2012)

PERFORMANCE RELATED VARIABLES

HOMERANK

Rank of the home team at

a given time period.

Masseyratings.com

(Paul et al., 2012)

Fans prefer to see best teams from biggest

conferences

AWAYRANK

Rank of the away team

at a given time period.

Masseyratings.com

(Paul et al., 2012)

Fans prefer to see best teams from biggest

conferences

8

Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics, Vol. 14 [2021], Art. 8

https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/jiia/vol14/iss1/8

Shapiro, Schulte, Popp & Bates

Downloaded from http://csri-jiia.org ©2021 College Sport Research Institute. All rights reserved.

Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

202

Data Collection

Data were collected from a variety of credible sources. Pricing data were collected from

individual team websites and StubHub. Team performance, conference, scheduling, television

broadcasting, and betting line data were collected from ESPN.com. Weather data were collected

from Weather.com. Enrollment data were collected from individual university websites.

Proximity data were collected from Google Maps. Team rank data were collected from the

Associated Press polls and the Massey Rating Composite Rankings (see Table 1).

Athletic department ticket prices were collected as schools released and sold tickets

online through their websites. All schools in the dataset posted prices for at least their first two

home games prior to the season commencing and most released ticket prices for all home games

at that time. However, a small number of schools released single game ticket prices for games

later in the season, typically two to four weeks prior to those games taking place. Data collection

HOMEPREVWINP

Home team win

percentage from year

before

ESPN.com

(Paul et al., 2012); (Shapiro & Drayer,

2012); (Drayer & Shapiro, 2009)

AWAYPREVWINP

Away team win

percentage from the year

before

ESPN.com

(Paul et al., 2012); (Shapiro & Drayer,

2012); (Drayer & Shapiro, 2009)

HOMECURWINP

Home team win

percentage measured

Monday of game day

week.

ESPN.com

(Paul et al., 2012); (Shapiro & Drayer,

2012); (Drayer & Shapiro, 2009)

AWAYCURWINP

Away team win

percentage measured

Monday of game day

week.

ESPN.com

(Paul et al., 2012); (Shapiro & Drayer,

2012); (Drayer & Shapiro, 2009)

HOMEBOWL

Did the home team make

a bowl game last year?

ESPN.com

(Falls & Natke, 2014); (Price & Sen, 2003)

AWAYBOWL

Did the away team make

a bowl game last year?

ESPN.com

(Falls & Natke, 2014); (Price & Sen, 2003)

RECRUITHOME

Recruiting class ranking

of the home team going

into the 2019 season

247Sports.com

(Paul et al., 2012)

RECRUITAWAY

Recruiting class ranking

of the away team going

into the 2019 season

247Sports.com

(Paul et al., 2012)

HOME MARKET VARIABLES

TIXPRICE

Cheapest price offered to

the public for the

particular game.

Team Websites

(Zhang, Lam, & Connaughton, 2003); (Falls

& Natke, 2016); (Price & Sen, 2003)

VENUECAPACITY

The seating capacity of

the home stadium

Team Websites

(Price & Sen, 2003)

ENROLLMENT

Total undergraduate

student body enrollment

of the home team at the

main campus

University Websites

(Price & Sen, 2003); (Paul et al., 2012)

9

Shapiro et al.: An Examination of Secondary Ticket Market Pricing Trends and Dete

Published by Scholar Commons, 2021

Secondary Ticket Market Pricing

Downloaded from http://csri-jiia.org ©2021 College Sport Research Institute. All rights reserved.

Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

203

for ticket price on resale markets occurred at four time periods; when the initial AP poll was

released, two weeks prior to game day, the Monday of game week, and one day before game

day. All viable factors (i.e., team performance, rankings, betting lines) were collected at the same

time as resale price.

Data Analysis

To answer research question one, descriptive statistics were used to assess pricing trends

over the four periods before game day. Real-time price changes on the resale market were

compared to each teams’ fixed single game ticket prices during these four time periods. To

answer research question two, descriptive statistics and a correlation matrix were examined

initially to assess normality of the data and variable relationships. Four fixed-effects ordinary

least squares (OLS) multiple regression models were developed to empirically examine the

factors influencing secondary market price at each time period. The fixed effects models were

used to account for the data being in panel form. The data were observed across four time-

periods, creating a cross-sectional time series. Multiple regression assumptions and

multicollinearity were examined, after which a reduced final regression model was created. A

significance level of .05 was established a priori in analyzing the regression model and related

variable correlations.

Results

A total of 434 unique games were included in the analysis. Over the course of 14 weeks,

four prices per game were recorded for a total of (N = 1,736) price observations. Single game

tickets were never made available for 15 games in the sample, most of which featured one or two

of the most popular teams in the country such as Clemson, Alabama, Ohio State, and Notre

Dame. Removing those games left a total of 419 games hosted by a Power 5 football team in

which single game tickets were available for purchase directly from the university athletics

department.

Overall, the mean athletics department price for a single football game ticket was $50.42,

with a minimum of $10 (Duke vs. North Carolina A&T, Louisville vs. Eastern Kentucky, and

Mississippi State vs. Kansas State) and maximum of $175 (Oklahoma State vs. Oklahoma). To

answer RQ1, these prices were compared to resale GIP on Stubhub over the four data collection

periods. For the first data collection period--the AP Poll release in August--StubHub GIP had a

mean of $38.45. In comparison to primary market prices, the resale price was $11.97 lower on

the secondary market. When examining the top ten biggest discrepancies between the primary

and secondary market during this time period, seven games had resale prices lower than the

primary ticket price. The majority of games had resale prices slightly below their primary market

price, and in terms of substantial spikes, there appears to be more games drastically overpriced

than underpriced during this time period.

At two weeks prior to game day, the trend continued, as athletic department ticket prices

exceeded the GIP on StubHub. The mean StubHub GIP was $37.35, $13.07 lower than the

average primary market price and $1.10 lower (9.2%) than when the price was captured before

the season started. On the Monday prior to game day, the mean StubHub GIP decreased to

$36.04, $14.37 above the mean primary ticket price. Finally, on the day before game day, the

10

Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics, Vol. 14 [2021], Art. 8

https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/jiia/vol14/iss1/8

Shapiro, Schulte, Popp & Bates

Downloaded from http://csri-jiia.org ©2021 College Sport Research Institute. All rights reserved.

Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

204

average StubHub GIP price dropped to $31.99, resulting in a difference of $18.43 below the

average primary market price.

Capturing StubHub data over different time periods allowed for a trend comparison

between primarily fixed primary market prices and fluctuating resale prices. It is important to

note that, on average, athletic department prices are higher than the secondary market at every

single time period. Additionally, the discrepancy increased through each time period as game

day drew nearer, with a 9.2% increase in price discrepancy from the initial AP Poll until two

weeks out, a 10% increase in price discrepancy from two weeks out to one week out, and a

substantial 28.3% increase in price discrepancy from one week out until one day out. The

difference between the prices is a direct result of the average StubHub GIP dropping at each time

period.

To address RQ2, four multiple regression models (one at each time period) were

developed to assess factors influencing resale GIP through Stubhub. Initially, models included a

total of 29 explanatory variables. However, due to multicollinearity and an effort to create the

most parsimonious model, while explaining as much unique variance in ticket prices as possible,

explanatory variables were considerably reduced in each final model. Data reduction techniques

included elimination of variables with variance inflation factors (VIF) above 10 or tolerance

levels below .1 and elimination of non-significant variables that were not deemed essential to the

model. Additionally, variance explained and F-statistics were assessed to identify the best fitting

models.

The first model (AP poll release) included a total of 14 independent variables. The

regression model was found to be significant F(27, 418) = 34.69, p < .001, explaining 70.5% of

the variance in resale ticket price for the time period. Significant variables included primary

market ticket price, road team factors (away team conference affiliation, recruit ranking of the

away team, away previous year win percentage, and whether or not the away team made a bowl

game the prior year), month the game took place, and whether the game was nationally televised

Variables included in the model (and their significance) and beta coefficients are reported in

Table 2. An examination of the unstandardized beta coefficients revealed a notable relationship;

for every $1 increase in primary market ticket price, resale price rose 82 cents. Thus, a positive

relationship exists between primary and secondary market price, but as primary market price

increases, the gap between the primary and secondary market price increases as well.

Additionally, it appears as if opponents play a considerable role in resale price during the initial

time period.

The second regression model, examining resale prices two weeks prior to game day,

included 13 determinants. This model was also significant F(26, 418) = 26.51, p < .001,

explaining 63.7% of the variance in resale prices at this time period. Some of the significant

explanatory variables in this model were also significant in the initial model, including athletics

department ticket price, month the game took place, and away team conference affiliation (see

Table 3). New significant variables in this model included proximity of the road team, away

team poll rankings, and home team previous season winning percentage. Unstandardized beta

coefficients revealed for every $1 increase in primary market ticket price, resale price rose 74

cents, extending the gap between primary and secondary market price compared to the initial

model. Additionally, resale prices dropped approximately $.60 for each additional 100 miles

between the campuses of the competing teams. Home team performance played a bigger role in

the second model as game day drew closer, but away team factors still played a more prevalent

role in the first two models.

11

Shapiro et al.: An Examination of Secondary Ticket Market Pricing Trends and Dete

Published by Scholar Commons, 2021

Secondary Ticket Market Pricing

Downloaded from http://csri-jiia.org ©2021 College Sport Research Institute. All rights reserved.

Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

205

Table 2

Significant Variables at AP Poll Release

Variable

Unstandardized

B

Coefficients

Std. Error

Standardized

Coefficients

Beta

t

Sig.

TIXPRICE

.817

.050

.632

16.24

<.001

PROXIMITY

-.004

.003

-.049

-1.59

.800

RECRUITAWAY

.109

.040

.205

2.72

.007

LINE

.188

.119

.092

1.57

.116

HOMEPREVWINP

12.55

9.83

.070

1.28

.202

AWAYPREVWINP

17.57

8.58

.099

2.05

.041

HOMECURWINP

6.52

4.56

.053

1.43

.153

AWAYCURWINP

-1.11

4.69

-.009

-.238

.812

MONTH1

-2.76

4.17

-.022

-.661

.509

MONTH3

-5.12

2.98

-.062

-1.72

.087

MONTH4

-8.39

2.92

-.109

-2.87

.004

HOMECONF1

-2.851

4.320

-.033

-.660

.510

HOMECONF3

4.284

5.412

.046

.792

.429

HOMECONF4

-7.309

4.761

-.085

-1.535

.126

HOMECONF5

2.042

5.325

.020

.383

.702

HOMECONF6

14.038

9.393

.046

1.495

.136

AWAYCONF1

-7.138

5.984

-.066

-1.193

.234

AWAYCONF2

-7.256

5.609

-.073

-1.294

.197

AWAYCONF3

-14.557

6.236

-.136

-2.335

.020

AWAYCONF5

-19.385

6.155

-.175

-3.150

.002

AWAYCONF6

-.394

7.231

-.002

-.055

.957

AWAYCONF7

-4.821

5.677

-.050

-.849

.396

AWAYCONF8

.924

8.549

.008

.108

.914

HOMEBOWL

4.782

3.546

.060

1.348

.178

AWAYBOWL

7.306

3.370

.101

2.168

.031

Notes: R

2

= .705

The third regression model, examining ticket prices a week prior to game day, included

14 variables and was significant F(15, 418) = 31.08, p <.001, explaining 53.6% of the variance

in GIP. Significant variables such as ticket price, proximity, and whether a game was nationally

televised were consistent compared to previous models. However, multiple significant variables

in this model did not appear in previous models, including poll ranking for the home team,

betting line, whether the game was a divisional matchup, venue capacity, and enrollment.

Additionally, this was the first model where weather was considered as a determining factor. The

temperature and precipitation forecasts a week out from game day were both found to be

significant as well.

There were some notable findings regarding the new significant variables. A divisional

matchup increases resale GIP by $5.46, all else equal. The home team moving up one spot in the

polls increases ticket prices by approximately 16%. Additionally, for every ten-percentage

12

Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics, Vol. 14 [2021], Art. 8

https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/jiia/vol14/iss1/8

Shapiro, Schulte, Popp & Bates

Downloaded from http://csri-jiia.org ©2021 College Sport Research Institute. All rights reserved.

Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

206

increase in precipitation, the ticket price increase by $12.33, conflicting with the assumption that

an increased chance of rain would naturally lower prices and lower fan interest in a game (see

Table 4).

Table 3

Significant Variables Two Weeks Prior to Game day

Variable

Unstandardized

B

Coefficients

Std. Error

Standardized

Coefficients

Beta

t

Sig.

TIXPRICE

.741

.054

.572

13.634

<.001

PROXIMITY

-.006

.003

-.068

-1.997

.046

AWAYRANK

-.129

.051

-.147

-2.538

.012

HOMEPREVWINP

23.683

10.220

.132

2.317

.021

AWAYPREVWINP

15.964

9.233

.089

1.729

.085

HOMECURRWINP

8.790

4.792

.071

1.834

.067

MONTH1

.620

4.491

.005

.138

.890

MONTH3

-4.001

3.297

-.049

-1.214

.226

MONTH4

-9.210

3.166

-.120

-2.909

.004

TV1

9.138

4.053

.100

2.254

.025

TV2

1.269

2.813

.017

.451

.652

HOMECONF1

-5.969

4.813

-.069

-1.240

.216

HOMECONF3

1.658

5.983

.018

.277

.782

HOMECONF4

-10.355

5.301

-.120

-1.954

.051

HOMECONF5

-.088

5.879

-.001

-.015

.988

HOMECONF6

2.137

10.397

.007

.206

.837

AWAYCONF1

-9.440

6.525

-.086

-1.447

.149

AWAYCONF1

.741

.054

.572

13.634

<.001

AWAYCONF2

-.006

.003

-.068

-1.997

.046

AWAYCONF3

-.129

.051

-.147

-2.538

.012

AWAYCONF5

23.683

10.220

.132

2.317

.021

AWAYCONF6

15.964

9.233

.089

1.729

.085

AWAYCONF7

8.790

4.792

.071

1.834

.067

AWAYCONF8

.620

4.491

.005

.138

.890

DIVISION

-4.001

3.297

-.049

-1.214

.226

HOMEBOWL

-9.210

3.166

-.120

-2.909

.004

AWAYBOWL

9.138

4.053

.100

2.254

.025

Notes: R

2

= .637

13

Shapiro et al.: An Examination of Secondary Ticket Market Pricing Trends and Dete

Published by Scholar Commons, 2021

Secondary Ticket Market Pricing

Downloaded from http://csri-jiia.org ©2021 College Sport Research Institute. All rights reserved.

Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

207

Table 4

Significant Variables One Week Prior to Game day

Variable

Unstandardized

B

Coefficients

Std. Error

Standardized

Coefficients

Beta

t

Sig.

TIXPRICE

.656

.060

.516

10.941

<.001

PROXIMITY

-.009

.003

-.109

-3.091

.002

HOMERANK

-.156

.072

-.142

-2.168

.031

AWAYRANK

-.081

.065

-.094

-1.243

.215

LINE

.343

.169

.170

2.026

.043

HOMEPREVWINP

18.065

12.011

.102

1.504

.133

HOMECURWINP

9.030

6.388

.074

1.413

.158

TV1

9.294

4.219

.104

2.203

.028

TV2

-2.530

2.976

-.034

-.850

.396

DIVISION

5.456

2.755

.077

1.980

.048

HOMEBOWL

7.469

4.408

.096

1.694

.091

VENUECAPACITY

.000

.000

-.131

-2.585

.010

ENROLLMENT

.000

.000

.113

2.783

.006

TEMPWK

.179

.080

.086

2.245

.025

PRECIPWK

12.331

5.974

.073

2.064

.040

Notes: R

2

= .536

Table 5

Significant Variables One Day Prior to Game day

Variable

Unstandardized

B

Coefficients

Std. Error

Standardized

Coefficients

Beta

t

Sig.

TIXPRICE

.497

.065

.419

7.608

<.001

PROXIMITY

-.008

.003

-.107

-2.644

.009

RECRUITAWAY

.070

.026

.142

2.675

.008

HOMECURWINP

14.844

4.823

.130

3.078

.002

AWAYCURWINP

13.289

5.257

.111

2.528

.012

MONTH1

14.214

5.007

.122

2.839

.005

MONTH3

-3.288

3.764

-.044

-.874

.383

MONTH4

-1.329

3.604

-.019

-.369

.712

TV1

7.652

4.361

.092

1.755

.080

TV2

-2.742

3.127

-.039

-.877

.381

VENUECAPACITY

.000

.000

-.096

-2.179

.030

PRECIPACTUAL

-12.356

4.569

-.108

-2.704

.007

Notes: R

2

= .389

The fourth and final regression model, examining resale GIP the day before game day,

was found to be significant F(12, 418) = 21.57, p <.001, explaining 38.9% of the variance in

14

Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics, Vol. 14 [2021], Art. 8

https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/jiia/vol14/iss1/8

Shapiro, Schulte, Popp & Bates

Downloaded from http://csri-jiia.org ©2021 College Sport Research Institute. All rights reserved.

Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

208

resale prices at this time period. Nine factors were found to be significant in this model. All nine

of these variables were significant at one point or another in previous models. The final model

includes ticket price and proximity, which have been relatively consistent throughout the

regression models, both home and away performance variables, month, whether the game was

nationally televised, venue capacity, and weather (see Table 5). Resale GIP dropped by $12.32

for every ten-percentage increase in precipitation chance, much more in line with expectations

that college football fans would pay less to watch games in unfavorable conditions. Also, for

every dollar increase in primary market price, resale GIP only increases by $.50, which is the

largest gap between primary and secondary market prices in all the models. Finally, the

percentage of variance explained continued to drop for each model as game day drew near,

indicating more uncertainty in pricing on days closer to game day. This appears to be counter to

anecdotal expectations.

Discussion

The goal of the current study was to examine how secondary market GIP fluctuates

(particularly compared to single game ticket pricing assigned by college athletics departments)

for Power 5 FBS football home games over the course of four time periods and to determine

what factors have a relationship to resale GIP at various points in time leading up to a football

game. Nearly all college athletics departments assign single game football ticket prices prior to a

season commencing, with only a handful delaying the release of late-season single game ticket

prices until weeks before the actual game is played. Tracking GIP pricing on the secondary ticket

market enables researchers and administrators to evaluate secondary market ticket pricing trends

and determine what factors may influence market price fluctuations over time.

Echoing the findings of prior studies of secondary marketing ticket pricing in MLB

(Drayer & Shapiro, 2009; Shapiro & Drayer, 2012, 2014), the NHL (Dwyer, Drayer, & Shapiro,

2013) and for college football bowl games (Rishe et al., 2016), the current analysis determined

that mean GIP for Power 5 college football games diminishes in a linear fashion as time moves

closer to game kickoff. The current study is the first in the literature to document such a trend

within college sport ticket pricing. For the entire sample, mean GIP prior to the start of the

season was $38.45, while the mean GIP one day prior to game day was $31.99, a reduction of

16.8%. By comparison, the mean ticket price assigned to the most inexpensive single game

tickets sold by athletics departments was $50.42.

The theoretical underpinnings of price discrimination (Courty, 2003; Rosen &

Rosenfield, 1997) and revenue management (Kimes, 1989) suggest ticket price setting should

become more dynamic and reflect buyers’ perceived value in order for firms (athletics

departments) to maximize revenue. However, past research by Morehead et al. (2017) suggests

college athletics administrators are guided by motives other than simply revenue maximization,

with stakeholder perception and the influence of competitors playing a key role in strategic

decision making. The lack of congruency between secondary ticket market prices and initial

ticket pricing established by college athletics departments suggest stakeholder and institutional

theories are more likely to explain pricing decisions than price discrimination and revenue

management.

For athletic departments wishing to maximize event attendance to appeal to key

stakeholders and generate more ancillary game day revenues such as concessions or parking

rather than focus on maximizing ticket revenue (Fort, 2004; Morehead et al., 2017), lower priced

15

Shapiro et al.: An Examination of Secondary Ticket Market Pricing Trends and Dete

Published by Scholar Commons, 2021

Secondary Ticket Market Pricing

Downloaded from http://csri-jiia.org ©2021 College Sport Research Institute. All rights reserved.

Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

209

ticket inventory available on the secondary market may have benefits. Theoretically, a wider

variety of fans may find ticket prices to be attractive on the secondary market, but the department

itself is not forced to devalue its own product by trying to match secondary ticket market prices.

However, for administrators wanting to maximize revenue, declining secondary market GIP is

problematic as it conditions ticket buyers to wait as long as possible in order to obtain the

greatest discount on tickets, and to look for those discounts solely on the secondary market. As a

result, departments may need to combat the availability of more affordable tickets on the

secondary market by tactics such as: (a) increasing the value of tickets purchased on the primary

market (i.e. providing concession discounts, access to specific seating sections, early venue

entry, etc.); (b) dynamically pricing tickets on the primary market; (c) staggering the timing of

when tickets go on sale; or (d) develop internal resale platforms and incentivizing season ticket

holders to utilize the platform, which would allow the department to capture resale fees and

consumer data.

When examining factors which seem to have a relationship with secondary market ticket

price, a few trends emerged from the regression models. First, as game day drew nearer, the

combination of the variables examined in the models explained less of the variance. Few prior

ticket pricing studies have examined the impact of so many traditional demand variables on

dynamic ticket price at multiple times leading up to a game. It was expected the further out from

kickoff--and thus the greater uncertainty regarding team performance and weather conditions--

the more difficult it would be to determine which factors would impact price variability. In

actuality, the opposite was true. Each subsequent model in the study explained less of the

variance in GIP, indicating unaccounted for explanatory variables (such as number of tickets

available or intrinsic motivations) may be more influential on secondary market ticket price,

closer to game day.

A second pattern emerging from the models was the influence of proximity between the

opponents on GIP. In the initial pre-season model, the distance between opponents was not

significant, while several factors related to the visiting team’s quality, such as the team’s

previous season record, whether the team travelled to a bowl game the previous season, and the

team’s recruiting ranking, were significant. This might suggest secondary market ticket prices

reflect sellers initially placing a high value on the quality of the opponent rather than where the

opponent was located. In subsequent models, the importance of the visiting team’s quality

diminished, but opponents from closer distances were significantly related to higher ticket prices.

This could be an indication ticket sellers will post higher prices when they believe more

opposing team fans are likely to travel to the game. It could also be a signal that games played

between opponents from closer geographic proximities are more likely seen as “rivalry” games,

thus commanding higher ticket prices on the secondary market. In an examination of the

secondary ticket market for NCAA March Madness games, Rishe et al. (2014) found prices also

increased as the distance between the tournament host site and the home campus of the teams

competing decreased, although other studies have suggested the further individuals travel, the

more willing they are to pay higher ticket prices to sporting events including college football

bowl games (Rishe et al., 2015).

Another intriguing finding from the current analysis was the impact of weather on ticket

pricing. Predicted temperature for the day of the game had no relationship with GIP. Perhaps

ticket sellers and buyers both readily acknowledge the college football season spans a time

period in which temperatures can be extremely hot in August and extremely cold in November.

The relationship between likelihood of precipitation detected in the models, however, paints a

16

Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics, Vol. 14 [2021], Art. 8

https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/jiia/vol14/iss1/8

Shapiro, Schulte, Popp & Bates

Downloaded from http://csri-jiia.org ©2021 College Sport Research Institute. All rights reserved.

Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

210

different picture. The higher the predicted likelihood of precipitation for a game a week before it

was played resulted in higher GIP. A day before the game, however, a more logical relationship

was revealed, as higher likelihood of precipitation had a negative relationship with GIP, a result

similar to those found in prior college football attendance studies (Falls & Natke, 2016; Price &

Sen, 2003). Perhaps when season ticket holders who frequently attend games look at the

extended forecast, they are more likely to make a decision to sell their tickets for that game, but

believe other buyers will be willing to pay premium prices. As game day draws nearer and

precipitation is still likely, perhaps ticket sellers realize it will be challenging to sell their tickets

and they decide to drop the price in hopes of recouping some money rather than “eating” the

tickets. As Ge, Humphreys, and Zhou (2020) note in their study of Major League Baseball

attendance, the impact of precipitation is an important and significant variable to consider among

dynamically priced tickets for sporting events.

Finally, the results highlight some interesting trends regarding the relationship between

the primary market price and resale GIP. Findings showed a widening gap between these prices

as a game draws near. This findings is consistent with Shapiro and Drayer (2012), who suggest

fixed primary market prices create arbitrage opportunities through pricing inefficiencies. Resale

ticket prices have the ability to fluctuate based on game, time, market, and environmental related

factors highlighted in this study, where primary market prices are static.

Interestingly, the results from the current study showed primary market prices were

higher than resale GIP at all time periods, which is contrary to what Shapiro and Drayer (2012)

found in Major League Baseball. This contradiction was not surprising, as Morehead et al.

(2017), suggested multiple factors make college sport ticket pricing different from professional

sport, including a wider array of stakeholders, organizational structure differences, and cultural

differences. Ultimately, college athletics departments must consider the inefficiencies created by

fixed pricing, highlighted through a growing resale market for college football tickets.

Limitations

The four models generated did possess some limitations. First, the ticket price recorded

from both the athletics department price and StubHub price are the cheapest available without

capturing any fees. Potentially, the overcharge by athletics departments mentioned in the results

could be smaller when fees are taken into account. However, for the purposes of the study, the

fees were not collected in order to conduct an “apples to apples” comparison. Additionally, some

of the time periods are inconsistent over time. Using AP Poll as a baseline to see where prices

start based on the first rankings makes sense, but the next measure did not take place until two

weeks prior to game day. With fourteen weeks in the regular season, ticket prices for games later

in the season are recorded in August but may not be revisited until October or November. One

final limitation stems from the way game day was recorded as a dichotomous variable of

Saturday or any other day of the week. Future datasets which include more seasons or non-Power

5 conferences may want to operationalize day of week as a categorical variable.

Moving forward, our models and dataset lay a strong foundation and a noteworthy

amount of information to continue into future studies. The models could be used in conjunction

with future datasets to evaluate relationships between predictor variables and ticket pricing,

perhaps to observe what prices seem to be overvalued or undervalued. Ultimately, such analysis

could lead to more effective ticket price setting. In fact, one limitation of the current study is that

data collection was limited to a single season. A multi-year study would allow for the

17

Shapiro et al.: An Examination of Secondary Ticket Market Pricing Trends and Dete

Published by Scholar Commons, 2021

Secondary Ticket Market Pricing

Downloaded from http://csri-jiia.org ©2021 College Sport Research Institute. All rights reserved.

Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

211

observation of longitudinal trends and could enable researchers to utilize the current regression

models to predict the overpricing or underpricing of future game tickets. The data can also be

used to supplement other research in the college football literature, perhaps not related to ticket

price itself. Overall, the study lays a framework for additional future research into college

football prices on the primary and secondary market while also still capturing significance and

comparison over four distinct time periods.

References

Berkowitz, S. (2020, April 14). Major public college football programs could lose billions in

revenue if no season is played. USA Today. Retrieved from

https://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/ncaaf/2020/04/14/college-football-major-

programs-could-see-billions-revenue-go-away/2989466001/

Berkowitz, S., Wynn, M., & McManus, C. (2019). NCAA Finances. USA Today. Retrieved from

https://sports.usatoday.com/ncaa/finances/

Courty, P. (2003). Ticket pricing under demand uncertainty. The Journal of Law and

Economics, 46(2), 627-652.

Diehl, M., Drayer, J., & Maxcy, J. G. (2016). On the demand for live sports contests: Insights

from the secondary market for National Football League games. Journal of Sport

Management, 30(1), 82-94.

Diehl, M., Maxcy, J. G., & Drayer, J. (2015). Price elasticity of demand in the secondary market:

Evidence from the National Football League. Journal of Sport Economics, 16(6), 557-

575.

Drayer, J., & Shapiro, S. L. (2009). Value determination in the secondary ticket market: A

quantitative analysis of the NFL playoffs. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 18(1), 5-13.

Drayer, J., Shapiro, S. L., & Lee, S. (2012). Dynamic ticket pricing in sport: An agenda for

research and practice. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 21(3), 184-194.

Dwyer, B., Drayer, J., Shapiro, S. L. (2013). Proceed to checkout? The impact of time in advaced

ticket purchase decisions. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 22(3), 166-180.

Falls, G. A., & Natke, P. A. (2016). College football attendance: A panel study of the Football

Championship Subdivision. Managerial and Decision Economics, 37(8), 530–540.

Fort, R. (2004). Inelastic sports pricing. Managerial and Decision Economics, 25(2), 87–94.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Boston: Cambridge

University Press.

Ge, Q., Humphreys, B. R., & Zhou, K. (2020). Are fair weather fans affected by weather?

Rainfall, habit formation, and live game attendance. Journal of Sports Economics, 21(3),

304-322.

Hester, P. T., Bradley, J. M., & Adams, K. M. (2012). Stakeholders in systems problems.

International Journal of System of Systems Engineering, 3(3/4), 225–232.

Howard, D. R., & Crompton, J. L. (2004). Tactics used by sports organizations in the United

States to increase ticket sales. Managing Leisure, 9(2), 87–95.

Kemper, C., & Breuer, C. (2016). Dynamic ticket pricing and the impact of time – an analysis of

price paths of the English soccer club Derby County. European Sport Management

Quarterly, 16(2), 233–253.

18

Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics, Vol. 14 [2021], Art. 8

https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/jiia/vol14/iss1/8

Shapiro, Schulte, Popp & Bates

Downloaded from http://csri-jiia.org ©2021 College Sport Research Institute. All rights reserved.

Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

212

Kimes, S. E. (1989). The basics of yield management. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant

Administration Quarterly, 30(3), 14–19.

Kimes, S. E., Lee, P. T. Y., & Ngonzi, E. N. (2015). Restaurant Revenue Management :

Applying Yield Management to the Restaurant Industry.

Morehead, C. A., Shapiro, S. L., Madden, T. M., Reams, L., & McEvoy, C. D. (2017). Athletic

ticket pricing in the collegiate environment: An agenda for research. Journal of

Intercollegiate Sport, 10(1), 83–102.

NCAA. (2020). NCAA Financial Database. Retrieved from

http://www.ncaa.org/about/resources/research/ncaa-finances-database

Paul, R., Humphreys, B. R., & Weinbach, A. (2012). Uncertainty of outcome and attendance in

college football: Evidence from four conferences. The Economic and Labour Relations

Review, 23(2), 69–82.

Paul, R. J., & Weinbach, A. P. (2013). Determinants of dynamic pricing premiums in Major

League Baseball. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 22(3), 152-165.

Popp, N., Shapiro, S. L., Walsh, P., Mcevoy, C. D., Simmons, J., & Howell, S. (2018). Factors

impacting ticket price paid by consumers on the secondary market for a major sporting

event. Journal of Applied Sport Management, 10(1), 23-33.

Popp, N., Simmons, J., Shapiro, S. T., Greenwell, T. C., & McEvoy, C. D. (2020). An analysis of

attributes impacting consumer online sport ticket purchases in a dual-market

environment. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 29(3), 177-188.

Price, D. I., & Sen, K. C. (2003). The demand for game day attendance in college football: An

analysis of the 1997 Division 1‐A season. Managerial and Decision Economics, 24(1),

35–46.

Rascher, D.A., McEvoy, C.D., Nagel, M.S., & Brown, M.T. (2007). Variable ticket pricing in

Major League Baseball. Journal of Sport Management, 21(3), 407-437.

Reese, J. T., & Mittelstaedt, R. D. (2001). An exploratory study of the criteria used to establish

NFL ticket prices. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 10, 223–230.

Rishe, P. (2014). Pricing insanity at March Madness: Exploring the causes of secondary price

markups at the 2013 Final Four. International Journal of Sport & Society, 4(2), 67-78.

Rishe, P. J., & Mondello, M. J. (2003). Ticket price determination in the National Football

League: A quantitative approach. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 12(2), 72–79.

Rishe, P. J., & Mondello, M. J. (2004). Ticket price determination in professional sports: An

empirical analysis of the NBA, NFL, NHL, and Major League Baseball. Sport Marketing

Quarterly, 13(2), 104-112.

Rishe, P.J., Mondello, M., & Boyle, B. (2014). How event significance, team quality, and school

proximity affect secondary market behavior at March Madness. Sport Marketing

Quarterly, 23(4), 212-224.

Rishe, P., Reese, J., & Boyle, B. (2015). Secondary market behavior during college football's

postseason: Evidence from the 2014 Rose Bowl and BCS Championship

Game. International Journal of Sport Finance, 10, 267-283.

Rishe, P., Sanders, D., Reese, J., & Mondello, M. (2016). A heterogeneous analysis of secondary

market transactions for college football bowl games. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 25, 115-

127.

Rosen, S., & Rosenfield, A. M. (1997). Ticket pricing. The Journal of Law and

Economics, 40(2), 351-376.

19

Shapiro et al.: An Examination of Secondary Ticket Market Pricing Trends and Dete

Published by Scholar Commons, 2021

Secondary Ticket Market Pricing

Downloaded from http://csri-jiia.org ©2021 College Sport Research Institute. All rights reserved.

Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

213

Schlabach, M., & Lavigne, P. (2020, May 21). Financial toll of coronavirus could cost college

football at least $4 billion. ESPN.com Retrieved from: https://www.espn.com/college-

sports/story/_/id/29198526/college-football-return-key-athletic-departments-deal-

financial-wreckage-due-coronavirus-pandemic

Shapiro, S. L., & Drayer, J. (2012). A new age of demand-based pricing: An examination of

dynamic ticket pricing and secondary market prices in Major League Baseball. Journal of

Sport Management, 26, 532–546.

Shapiro, S. L., & Drayer, J. (2014). An examination of dynamic ticket pricing and secondary

market price determinants in Major League Baseball. Sport Management Review, 17,

145-159.

Smith, C. (2019, September 12). College football's most valuable teams: Reigning champion

Clemson Tigers claw into top 25. Forbes. Retrieved from

https://www.forbes.com/sites/chrissmith/2019/09/12/college-football-most-valuable-

clemson-texas-am/#4258fdf7a2e7

Watanabe, N. M., Soebbing, B. P., & Wicker, P. (2013). Examining the impact of the StubHub

agreement on price dispersion in Major League Baseball. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 22,

129-137.

20

Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics, Vol. 14 [2021], Art. 8

https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/jiia/vol14/iss1/8