DOCUMENT RESUME

ED 420 116 EA 029 092

AUTHOR Spady, William G.

TITLE Paradigm Lost: Reclaiming America's Educational Future.

INSTITUTION American Association of School Administrators, Arlington,

VA.

ISBN

ISBN-0-87652-232-0

PUB DATE

1998-00-00

NOTE 168p.; Foreword by Paul D. Houston.

AVAILABLE FROM AASA Distribution Center, 1801 N. Moore St., Arlington, VA

22209 (Item No. 236-001; $24.95, nonmember; $19.95, member;

$4.50 postage and handling; quantity discounts).

PUB TYPE

Books (010) Reports Descriptive (141)

EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage.

DESCRIPTORS *Educational Attitudes; Educational Change; Educational

Innovation; *Educational Strategies; Elementary Secondary

Education; *Empowerment; Models

IDENTIFIERS Paradigmatic Responses

ABSTRACT

The ways in which a paradigm of empowerment can be adopted

in schools are explored in this book. The book is divided into two

sections--the importance of being a paradigm pioneer and the Future

Empowerment Paradigm--and focuses on four points: (1) The systemic inertia

that keeps schools tied to a familiar, comfortable, unproductive, and

self-reinforcing legacy of old practices and structures; (2) the history and

defining elements of the Future Empowerment Paradigm of educational reform

that was driven underground in the early 1990s; (3) the major losses

educators have suffered as individuals, as a profession, and as an

institution because of the lost paradigm; and (4) what local educational

leaders can do to establish the learning success and life performance

elements of the Future Empowerment Paradigm. The chapters focus on the power

of paradigms, the lost ideal of education, how to establish an empowering

learning community, how to design student empowerment outcomes, and how to

chart a course toward future empowerment. (Contains 34 references.) (RJM)

********************************************************************************

Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made

from the original document.

********************************************************************************

PARADIGM LOST

I

U S DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION

Office of Educational Research and Improvement

EDUCA

NAL RESOURCES INFORMATION

CENTER (ERIC)

his document has been reproduced as

received from the person or organization

originating it

Minor changes have been made to

improve reproduction quality

Points of view or opinions stated in this

document do not necessarily represent

official OERI position or policy

1

PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND

DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS

BEEN GRANTED BY

TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)

c

0-

0

ci.

cAS

1

III

I

0

.

1

cl

4.1

I

I

' I

I

I

I

I

I

PARADIGM LOST

Reclaiming America's Educational Future

WILLIAM C. SPAR

LEADERSHIP

FORFOR LEARNING

American Association of School Administrators

3

American Association of School Administrators

1801 N. Moore St.

Arlington, VA 22209

(703) 528-0800

http: / /www.aasa.org

Copyright(c) American Association of School Administrators

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy,

recording, or any information storage and retrieval system without permission in

writing from the American Association of School Administrators.

Executive Director, Paul D. Houston

Deputy Executive Director, E. Joseph Schneider

Editor, Ginger R. O'Neil, GRO Communications

Copy Editor, Liz Griffin

Designer, Vanessa Spady

Printed in the United States of America.

AASA Stock Number: 236-001

ISBN: 0-87652-232-0

Library of Congress Card Catalog Number: 97-74947

To order additional copies, call AASA's Order Fulfillment Department at

1-888-782-2272 (PUB-AASA)

or, in Maryland, call 1-301-617-7802.

4

DEDICATION

This book is dedicated to five close friends and colleagues who

shared my vision for America's schools, stood by me during my most

discouraging hours, inspired and challenged my thinking, and

provided deep and joyful connection in all aspects of my life.

Ronald Brandt

Arnold Burron

Charles Schwahn

Karolyn Snyder

Bruce Wenger

William Spady

PARADIGM LOST

Reclaiming America's Educational Future

Acknowledgments

vii

Foreword

ix

Prefaces

xi

Section I: The Importance of Being a Paradigm Pioneer

The Power of Paradigms 1

The Paradigm We Lost

11

What Went Wrong

33

Assessing Our Loss 55

Personal Consequences and Insights 75

Section II: The Future Empowerment Paradigm

Establishing the Bases of an Empowering Learning Community . . .97

Charting Your Course Toward Future Empowerment 113

Designing Empowering Student Outcomes 127

Aligning an Empowering Instructional System 143

Bibliography

155

About the Author

158

PARADIGM LOST

v

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The encouragement and direct assistance of many friends and col-

leagues led to the ultimate development and production of this book.

First, I want to deeply thank AASA's key administrators, Paul Houston

and Joe Schneider, for their understanding of the many dilemmas facing

public education today and for their courage and willingness to sponsor

this endeavor. Without their initial encouragement and continuing sup-

port, it is highly unlikely that I would have written Paradigm Lost. I

hope that its substance does justice to their confidence in me.

Second, I am deeply indebted to a host of friends and family members who

took the time to scrutinize the multiple drafts of this manuscript. Their

candid and perceptive views of its accuracy, readability, fluency, and rel-

evance helped me enormously. Chaim Adler, Ron Brandt, Arni Burron,

Karen and Larry Gallio, Kandace Laass, Chuck Schwahn, Sha Spady,

and Bruce Wenger get gold stars and deep gratitude for their extremely

helpful comments at all stages of this work. Without Arni's insights and

feedback from "The Right," and his enormous support and encourage-

ment during my darkest hours, this book wouldn't have happened.

Third, the extraordinary collaboration I have had with Chuck Schwahn

over the past dozen years has contributed immeasurably to my growth

and success as a professional. He has never wavered in his exceptional

devotion to quality, honesty, and professionalism, and he has been the

consummate contributor always managing an inspiring level of new

ideas, constructive criticism, insightful advice, and deep affection. His

influence on this work has been profound.

Finally, one could not hope to find a better editor than Ginger O'Neil.

Ginger offered the perfect balance between insightful critic, informed

expert, and enthusiastic supporter. Her warmth, openness to novel pos-

sibilities, and win-win orientation made writing and rewriting incredibly

easy. Thanks also to Vanessa Spady. She always brought her original

and highly professional touch to her Dad's most commonplace ideas

about the layout of diagrams and figures. Deepest thanks to both.

7

PARADIGM LOST

vii

FOREWORD

Much of Bill Spady's life's work has involved going out on a limb. While

that's a dangerous place to be, it's also where one finds the sweetest fruit.

In Paradigm Lost, Bill once again forges into new territory by attempting to

pull together the key pieces related to educational improvement for educa-

tors. The result is a book that every educator and board member should

read and take to heart. Paradigm Lost portrays a unique, rich, and pene-

trating picture of four key things:

The systemic inertia that keeps our schools tied to a familiar, comfort-

able, unproductive, and self-reinforcing legacy of old practices and

structures that resists all attempts at systemic change;

The history and defining elements of a powerful Future Empowerment

paradigm of educational reform that America was on the verge of

embracing until we let the forces of reaction drive it underground in

the early 1990s;

The major losses we have suffered as individuals, as a profession, and

as an institution because of the lost paradigm; and

What local educational leaders can strategically do to establish the

learning success and life performance elements of this badly needed

Future Empowerment paradigm in their communities.

This is more than a lament about the loss of outcome-based education by

the man who is universally regarded as the concept's leading advocate. Bill

Spady gives us an extremely comprehensive, insightful, and personal look

at the much larger picture of major educational reform over the past

quarter century; the key ideas and players that challenged our "Iceberg

Paradigm" of schooling and defined the push for greater learning success

in all of America's schools; the issues underlying the attacks we have

experienced for the past several years on virtually everything remotely

connected to learning outcomes for students; and a powerful and practical

set of future-focused strategic design and strategic alignment tools that

local districts can use to get their schools and communities on the road to

genuine future empowerment.

I challenge those who think they've been there and done that with either

OBE, curriculum reform, or performance assessment to tackle the double

paradigm shift described in Chapter 2. At its core is Spady's unique insight

about the educentric perspective that we educators all share, a perspective

PARADIGM LOST

ix

that results in all of our attempts to reform and improve schools starting

with the way schools are (and how they've always been) the

essence of

educentrism instead of with a clear picture of the future

our students

face and must shape. As the saying goes, "If

you always do what you've

always done, you'll always get what you've always gotten." But if

we would

start with the future, Spady compellingly argues in Chapters 7, 8, and 9,

we'd never invent the kinds of learning systems

we have inherited from

past generations and seem determined to preserve.

Not surprisingly, then, Paradigm Lost is filled with powerful and practical

insights about the systemic nature of schools and the beliefs and

assump-

tions on which they operate; the conditions of

success that must be

enhanced to ensure greater learning success for

our students; the fears and

motivations of those who attack progressive reforms; the status of various

local, state, and national reform efforts today; and most of all insights

about what local leaders can do to establish true learning communities

based on future-focused thinking, planning, curriculum design, instruction,

assessment, and improvement strategies in their schools.

Paradigm Lost is a great gift to education leaders from

a man who has

risen above professional and personal loss and stigmatization in

recent

years to give us a masterful portrayal of an educational future we should be

proud as leaders to reclaim and even prouder to achieve.

Paul D. Houston

Executive Director

American Association of School Administrators

9

PARADIGM LOST

PREFACES

"This man has been described as a socialist, a communist, a globalist, a

one-worlder, a new-ager; as anti-Christian, anti-traditional values, anti-

family, unamerican, diabolical, duplicitous, subversive; and with a host of

other pejoratives."

With these words, I introduced my then-colleague-now-friend Bill Spady to

an audience of several hundred public school professionals who had come

to hear about a new, common ground movement upon which Bill and his

erstwhile adversary Bob Simonds, of Citizens for Excellence in Education

notoriety, had embarked.

Glancing down at Bill, I continued, "Did I leave anything out?"

"Yes," Bill replied, to the delight of the audience. "You forgot to mention

that I'm bald!"

But there was also much more that was left out of the description that day:

That the man who had been the unfair target of more pejoratives than any

other education reformer since John Dewey could more accurately have

been described as an honest, caring, open-minded professional. That he

was sincerely interested in achieving the best education possible for all of

the constituents of the public schools. That he was willing to defend his

ideas in fair and open debate with his critics. That his visionary perspec-

tives had been appropriatedhighjacked would be a more accurate

termby a cadre of social engineers who had contaminated and perverted

his sound ideas in pursuit of their own agendas and forced him to unfairly

"take the rap" for their misapplication of the principles of outcome-based

education. And that he had not tried to blame others for the widespread

attacks on OBE when he could accurately have done so.

What also could have been said was that Bill Spady's openness and willing-

ness to listen to people like meTraditionalist Christiansattested to his

personal and professional integrity and honestyqualities that will carry the

day in what may well turn out to have an even greater impact on the public

schools of America than his original work in systemic reformthe achieve-

ment of common ground among America's contending constituencies.

In many ways, this book is a "handbook" toward achieving that end.

Arnold Burron

Director, Center for Constructive Agreement

University of Northern Colorado

Greeley, Colorado

10

PARADIGM LOST

xI

A Superintendent's Take on Paradigm Lost

"The way we DO SCHOOLS used to make sense. It doesn't anymore.

But we're still doing it anyway.

"Our schools made sense when we didn't know that all students can

learn

. . .

but now we know better.

"Our schools made sense when we knew little about how the brain works

and how students learn

...

but now we know much more about both.

"Our schools made sense when sorting students for the job market could

still ensure the good life for all but it doesn't anymore.

"Our schools made sense in the Industrial Age but they don't in the

Information Age.

"The way we DO SCHOOLS used to make sense... it doesn't anymore."

I would welcome anyone to challenge Bill Spady to a debate on this point

of view. Anyone able to put aside tradition, political bias, and fear long

enough to be logical would have to agree that schools are implementing

only a fraction of what we know about students and learning, about teach-

ers and teaching, and about effective schools and effective organizations.

You just can't do for students what we know they need to function success-

fully in a highly competitive and rapidly changing world, while insisting

that schools and school districts retain the structures, policies, and prac-

tices of the Industrial Age. Period.

I first met and heard Bill Spady in the Black Hills of South Dakota in the

mid '70s. He explained a simple matrix for education that put time on one

axis and outcomes on the other. As he spoke, I came to realize that schools

were structurally set with time as the constant and student learning as the

variable. Bill argued, rather emotionally as I recall, for a reversal of that

priority, which would make student learning the constant and time the vari-

able. It hit me. I got it. I have not been the same since.

Since that time, Bill has gone on to describe and define an approach to

schooling The Future Empowerment Paradigm

that allows and

encourages our profession and professionals to implement the very best

that we know about students and learning, teachers and teaching, and

effective organizations. Our profession does not have another model or

approach that can make that claim. True, the Effective Schools movement

has been a bright light, but it tinkers with, rather than systematically

11

PARADIGM LOST xIII

changing, the system. It still gives in to structures, policies, and

processes

that restrict students, teachers, and schools. The same can be said about

Accelerated Schools, about the Coalition of Essential Schools, and about

numerous other reform movements and organizations. Transformational out-

come-based education (Oops, Oops... Can I say those words?) is the only

PARADIGM SHIFTER. And I strongly believe that it is the only paradigm

that will allow me to confidently call education a "profession."

We lost our profession in 1994. We educators, we educational leaders,

we

educational associations, we superintendents caved in. We let a relatively

small group of people who were ill-informed, dishonest, mean spirited,

and paranoid stop a movement in its tracks that held great promise for

empowering learners and bringing education into the Information Age.

It was a sad time for me and I have not yet recovered. I was forced to

admit that what I had called my profession was no more than a politically

directed bureaucracy, True professions (1) act on their client's needs,

(2) promote and use their own research to improve their services, and

(3) embrace accountability. At present, our system of schools does none of

the three The Future Empowerment Paradigm Bill describes in this

book totally nails them all.

Now you don't have to establish Bill's Future Empowerment Paradigm to

be professional, but you do have to focus on clients rather than politics,

you do have to follow your own research rather than be told how to teach

by groups of political paranoids, and you do have to be honest about and

take credit or blame for student learning.

I'm an eternal optimist. And when I read Paradigm Lost, I got "pumped"

again. Bill has spelled out a clear and somewhat complex approach

that we can take if we wish to regain our lost paradigm.

My advice to today's superintendents

those who believe that the

Future Empowerment Paradigm is critical and who believe education

must become a profession

is to make Paradigm Lost must reading for

principals, teachers, board members, and any community members who

could be of support. (I would especially target those YUPPIES who

know the Information Age through their businesses and professions, but

do not seem to believe that schools deserve the same paradigm transfor-

mations that have allowed their businesses to compete in today's global

market.) Superintendents are called upon to be the lead learners and to

create learning organizations. This is our chance to model the values

12

xiv

PARADIGM LOST

and principles of your district and our profession to colleagues, staff,

and the community.

I also encourage superintendents to create a true dialogue about the Future

Empowerment Paradigm throughout their entire systems. I would have

everyone come to know what the paradigth is, how it is aligned with what

we know about learning, and how it compares to present practices.

It won't be easy, but it will be satisfying, It won't be pleasant, but it will be

a professional response. It won't be quick, but it will add meaning to your

work days. Education is the most important work of the world and I believe

that the Future Empowerment Paradigm must start with the leader, the

CEO, the lead learner, the visionary leader... the superintendent.

Chuck Schwahn

Schwahn Leadership Associates

13

PARADIGM LOST

xv

THE IMPORTANCE

OF BEING

A PARADIGM PIONEER

14

CHAPTER

I

THE POWER OF PARADIGMS

Paradigms are fundamentally about how we view and perceive our

world and what we allow ourselves to see as true, possible, or desirable.

When shared and endorsed, they shape the thinking patterns, beliefs,

and cultures of family groups, friendship networks, formal organiza-

tions, professional associations, and even entire societies. These

patterns of thought help us understand, interpret, and

make sense of

what we later do and experience. Some people think of paradigms as

governing beliefs we use to determine true from false, relevant from

irrelevant, important from unimportant, and safe from dangerous.

Others describe them as systems of screens and filters we use to block

out or disregard that which we don't readily recognize or agree

with.

Clearly, paradigms are powerful. But there is more, and it's even more

important. Paradigms also determine how we behave; our paradigms

shape our habits of behavior and decision making. What we do and the

alternatives we allow ourselves to consider and choose are governed

that is, are limited and constrained

by what we allow ourselves to

"see" as possible or desirable. When we make decisions and act in

ways consistent with those familiar and

comfortable patterns of thinking,

we confirm their validity and usefulness

for us, which further reinforces

their influence on our way of viewing and dealing with the world.

Paradigm Paralysis

Joel Barker, who has written extensively on the power of paradigms and

the problems of paradigm paralysis, uses the example of the wristwatch

in his 1990 videotape "Discovering the Future" to explain the need to

thoughtfully reevaluate paradigms. Until the 1980s, the Swiss were the

recognized masters of making clocks and watches and controlled the

world market. Their paradigm: A watch is a tiny clock, requiring the

same components as a clock springs, gears,

and hands

but all in

miniature. Because of this viewpoint, the Swiss rejected using the quartz

crystal technology that their own researchers pioneered because they

PARADIGM LOST

1

saw no connection between it and timepieces. But Texas Instruments

did, and so did the Japanesewith enthusiasm! The

rest is history.

As a result of this paradigm paralysis, the Swiss watch

industry

almost collapsed. Today,

as Barker points out, the Swiss are selling

beautiful jewelry that also keeps time, and the Japanese

are selling

nearly all of the world's watches.

Systemic Paradigm Shifts

What this Swiss watch example illustrates, and Thomas

Kuhn's

(1970) pioneering work asserts, is that paradigms apply

to and affect

not only our individual patterns of thought and action, but entire

sys-

tems of thinking and behavior in organizations, industries, fields of

endeavor, countries, and cultures. Changes in the thinking

and

actions of single individuals

usually those recognized as innovators,

pioneers, or even revolutionaries

can, if sound and compelling

enough, eventually shift the operating paradigms of

organizations,

institutions, and entire societies. Shifts of this potential magnitude

and impact are called "systemic" because they affect the

fundamen-

tal functioning of major social and organizational

entities. Such shifts

in education are reliant

upon school leaders willing to thoughtfully

examine the paradigm of schooling.

Systemic paradigm shifts change the

way major systems work, the

goals they pursue, and the structures they

create, including the:

Knowledge base on which the system depends,

Techniques and technologies used,

Roles and responsibilities people

assume,

Status and influence people acquire,

Expectations and standards that shape individual and

group performance,

Outcomes and results the system achieves,

Nature and patterns of human interaction and relationships,

and

Ultimate meaning and value attached to everything.

16

2

PARADIGM LOST

Systemic paradigm shifts are inherently transformational that is,

they change the fundamental nature of everything known and done

previously. By comparison, everything else we do amounts to techni-

cal tinkering a term I explain in Chapter 4.

For example, we all recognize the writing of the Magna Carta, the

invention of the printing press and telescope, circumnavigation of

the globe, the discovery of electricity, the invention of the automo-

bile, and the development of radio, television, and satellite

communications as a few of the truly transformational developments

that have radically changed humanity's "vision of the possible" and

way of living. In retrospect, we are comfortable with

these particular

transformations and recognize that they have changed the nature of

human understanding and the course and character of human histo-

ry. But for the people who directly experienced

them, these

transformations represented a huge threat to their investment in the

prevailing paradigm. For, as Barker notes in his video, "When the

paradigm shifts, everything goes back to zero."

"Going back to zero" means that those people or organizations with

all the "points," successes, and advantages lose them and must rede-

fine themselves and compete anew. This displacement of the familiar

by the new engenders uncertainty, fear, mistrust, reaction, and, at

times, strident appeals for sticking to the tried and true. Those with

the most to lose try the hardest to make the old work, elaborating

rhetorically on its inherent merits, and placing deliberate obstacles

in the way of the new

often causing short-term setbacks in what

appears to be an inevitable pathway to change.

This natural pattern of resistance and reaction to paradigm change is

exactly what has happened recently in the United States when fun-

damental educational changes have been introduced. What seemed

to be an impending systemic paradigm shift in thinking, policy, and

practice toward educational change in the early '90s lies largely lost

today under an avalanche of political reaction and reforms that tin-

ker rather than transform. Whether that paradigm is rediscovered or

remains a casualty of societal fear and reaction rests in your hands

today's educational leaders

and in the hands of the constituents

you influence and serve.

17

PARADIGM LOST

3

The Paradigm We Share

The paradigm that is now lost evolved during the 30

years following

WWII in direct response to the paradigm of schooling that

middle-

aged Americans all share. Almost all of today's U.S. education

leaders attended school in the United States in

or shortly after the

1940s. This was the Golden Era of what is

now recognized as the

Industrial Age, and our schools embodied

many of the key elements

that define that era: They were highly structured with time-regulated,

assembly-line movement of students through

programs, hierarchical

relationships, and so on. Knowing what

we did then, this all made

sense, but it doesn't anymore because the Industrial Age is over.

I can state with confidence that, for almost all of today's education

leaders, the schools we attended

were buildings with many enclosed

rectangular rooms, each with four walls and

one doorway. Usually one

of those walls contained a bank of windows that

gave us a glimpse of

the world outside, and the difference between

our elementary school

and our high school was mainly

one of size, not structure.

Elementary School

When we were very young, everything about school

was very new,

very big, and often very confusing. We thought the rooms to which

we were assigned for 9 months belonged to a given teacher because

it had her name on the door. The students who

were assigned to that

room with us were almost all our own age. Our group was called

a

"class," and both our room and

our class were called "grades" the

specific levels into which our work

was divided. Most of what we and

"our" teacher did during the day happened in that particular

room,

and many of our books had

a number on them that matched the

grade we were in.

One very new thing was called "report cards." Our teachers

gave them

to us to take home every few months. These complicated-looking

pieces of paper had all kinds of long words like "deportment"

on

them and little spaces for teachers to make marks

or write in letters

and numbers. At first we had

no idea what this card and all its

marks and spaces meant, but

we soon observed that our teachers and

parents took them very seriously.

18

4

PARADIGM LOST

After a while, we learned more about the marks our teacher was

putting on the report card. Some of them were "good" and some of

them were "bad" just like we learned about the marks she had

been putting on our papers in red pencil.. We also learned that one of

the best ways to stay out of trouble was to avoid getting bad marks

put on anything, but especially on our report cards. To get good

marks we had to promptly do what our teacher asked, not get into

trouble with other kids, and not make mistakes on our papers.

Because most of us educated adults liked school as kids, got along

with our classmates, and learned fairly quickly, we usually got good

marks on our report cards.

One thing we did every day in those early years at school was to

have reading. Almost right away our teacher put us in three different

groups the Robins, Blue Birds, and Parakeets. Those of us in the

Robin group read faster and better than many of our classmates.

Nine years later we Robins ended up in the same classes in high

school, which our teachers called "college prep." The kids in the

Parakeet group had trouble reading so we rarely had them in our

classes in high school. Their classes were called "remedial," and

most of them didn't go to college like we did.

The most serious thing we did in school was to take special tests,

which were printed nicely in big pamphlets. Our teachers told us not

to worry about these tests, but they themselves seemed concerned.

When we took them we all had to begin at the same time, remain

absolutely silent, and finish when we were told, rather than when we

were done.

Just as summer came along we got the most important mark of the year

on our report cards. It told our parents whether we would be promoted

or retained. At first we had no idea what these fancy words meant, but,

as before, we soon learned that "retained" meant that you were

"dumb" and couldn't learn what was going to be in next year's books.

Only a few of the kids we knew were ever retained. The rest of us got

to go on to a new room, a new teacher, and new books in September.

The older we got the more important "points" became. We learned

that everything we did was worth 100 points: homework, quizzes,

papers, tests, projects. It didn't take long for most of us to learn that

I9

PARADIGM LOST

5

our goal was to get as many points as we could because points had

clearly replaced those various marks

on our earlier report cards as

the indicator of how good and smart

we were.

About this time we also observed that

our books had gotten thicker

and contained fewer pictures. This, we

were told, showed that we

were getting smarter and doing more grown-up work. That was nice

to hear, but it didn't compensate for the fact that our favorite thing

recess had disappeared from our daily schedule, though it did get

replaced by something called "gym."

In addition, it appeared that the smarter

we became the shorter our

report cards got. After the first several grades, the card no longer had

spaces on it for things like "gets along well with others." It just had

spaces for words that matched the names of our books

things like

arithmetic and social studies, our subjects. To make it

worse for

those of us who liked getting a good mark in the "gets along"

space,

the spaces next to each subject were pretty small. At first

we weren't

sure if that meant there wasn't much to learn in that subject, or there

wasn't much to report, or both.. But it only took

a couple of report

cards to reveal that those small spaces

were just large enough for our

"grade" a letter or number our teacher devised after averaging all

of the different things we had been doing during that "grading peri-

od." Yes, everything we did and everything that the teacher wanted

our parents to know about us in school somehow got squeezed into

those tiny spaces next to the names of the subjects.

Knowing what we did then, this all made

sense, but it doesn't any-

more because the Industrial Age is over.

Nonetheless, we were told all of this was getting

us ready for high

school

a place where everyone was grown up and the work was

much harder than anything we could imagine.

High School

High school had several familiar things from the later

years of ele-

mentary school, but it was a world unto itself. At first, everything

about it seemed new, big, and confusing. Bells

were always ringing,

the hallways were mobbed, and you

were just supposed to know:

6

PARADIGM LOST

20.

What all the bells meant; what a "schedule" was; what "elec-

tives" were; what "tracks" were; what your seven different

teachers' names were; what the administrators' names were;

what counselors were and what their names were; where the

cafeteria was and how long you had to eat; where lockers were;

what pep rallies were; the school song; what "varsity" meant;

what "semesters" were; what terms like "freshman" and "sopho-

more" meant; what "GPA" meant

namely, life or death; what

"the curve" was; what "Carnegie units" were; what "college-

prep" meant; what class rank meant; what SATs and ACTs

were; what "recommendations" were; that all grading was in

permanent ink (so that all mistakes counted against you forever);

and how to spell physics and Shakespeare.

And that was just for starters in this strange and unique institution.

But to dispel our confusion, we were continually told that all of this was

getting us ready for college

a place where everyone was very grown

up and the work was much harder than anything we could imagine.

Today's education leaders not only shared many of these educational

experiences, we internalized and mastered their meaning and impor-

tance and negotiated our way through this maze successfully. For we

"succeeded" in this paradigm

and ranked high enough among our

peers to be accepted to college. Once there we again succeeded in a

similar system with a similar way of doing business for at least

another four years and received a degree. And beyond that, those of

us who are educators found the experience of being in and around

schools so congenial that we then devoted our career lives to it. For

as my colleague Kit Marshall often observes: Educators have been in

school since they were five.

And to that I can only add: It's so familiar we've made it our comfort zone.

The Systemic Character

of the Paradigm We Share

Comfort zone or not, the more time I have spent with educators dur-

ing the past 20 years, the more I have become aware of the highly

personal and particularistic rather than organizational view they held

21

PARADIGM LOST

7

of their schools, their work, their problems, and their achievements.

How things operate, what people do, or what problems they face

are

attributed either to the intentions, capabilities, and behaviors of

par-

ticular individuals, or to the unique characteristics of particular

situations. If only this person had done this rather than that, or

because this person did such and such, or because this particular

thing happened to be placed in that particular location,

we now are

faced with this (usually negative) situation; the unstated assumption

being that everything would be running smoothly if it weren't for this

certain behavior or circumstance.

As someone with a strong organizational perspective about schools,

I always feel uncomfortable about addressing issues this

way

especially after reading Tom Peters' and Robert Waterman's (1982)

classic In Search of Excellence; becoming thoroughly enamored of

Joel Barker's work on the nature and power of paradigms; studying the

work of W. Edwards Deming; and having my paradigm perspectives

blown by Robert Theobold's (1987) extremely perceptive book The

Rapids of Change. These non-educational sources compelled

me to

look even more deeply than I had at two key things about education:

(1) the future it and its students face, and (2) the fundamental character

of how education was constituted and how it operates

as a system.

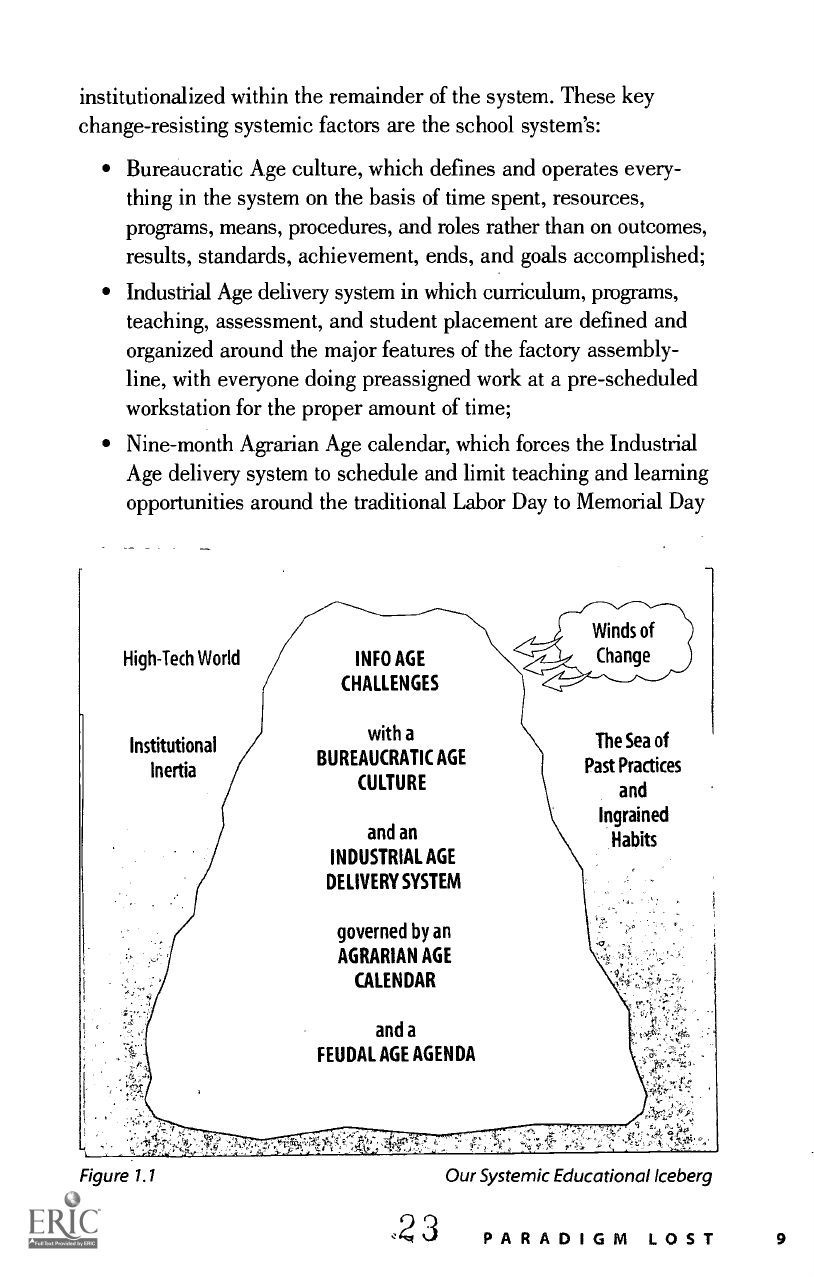

The result of this deep analysis was literally a picture

that of an

iceberg drifting in a (familiar, comfortable, unquestioned) sea of

ingrained habits, past practices, and institutional inertia barely influ-

enced by the winds of change and Information Age realities blowing

on the top of its surface. The rest of the iceberg remains sheltered

from and largely uninfluenced by these future conditions and reali-

ties. Its direction and momentum come almost entirely from the sea

in which it drifts. That iceberg, represented in Figure 1.1 (on p.9) is

the conceptual bedrock of the remainder of this book.

From a systemic perspective, the paradigm of schooling

so familiar

to all of us is the accumulation of the cultural and historical para-

digms on which it was constructed. At its tip are the educators'

attempts to respond to the constantly evolving and increasing chal-

lenges of today's Information Age. But their best individual efforts

are being constantly resisted by the inertia of the past that is deeply

8

PARADIGM LOST

22

institutionalized within the remainder of the system. These key

change-resisting systemic factors are the school system's:

Bureaucratic Age culture, which defines and operates every-

thing in the system on the basis of time spent, resources,

programs, means, procedures, and roles rather than on outcomes,

results, standards, achievement, ends, and goals accomplished;

Industrial Age delivery system in which curriculum, programs,

teaching, assessment, and student placement are defined and

organized around the major features of the factory assembly-

line, with everyone doing preassigned work at a pre-scheduled

workstation for the proper amount of time;

Nine-month Agrarian Age calendar, which forces the Industrial

Age delivery system to schedule and limit teaching and learning

opportunities around the traditional Labor Day to Memorial Day

High-Tech World

Institutional

Inertia

INFO AGE--

CHALLENGES

with a

BUREAUCRATIC AGE

CULTURE

and an

INDUSTRIAL AGE

DELIVERY SYSTEM

governed by an

AGRARIAN AGE

CALENDAR

and a

FEUDAL AGE AGENDA

The Sea of

Past Practices

and

Ingrained

Habits

Figure 1.1

.23

Our Systemic Educational Iceberg

PARADIGM LOST

9

calendar so that even today's students have the summer off to

harvest crops (and forget lots of last year's work); and

Its insidious Feudal Age agenda of sorting and selecting the

most able and deserving students from the others so that high-

level educational opportunities are not "wasted" on others.

Together, this set of systemic factors has defined and shaped the

schools we all attended, and their inertia is deeply institutionalized

throughout our society in state laws, regulations, policies, school

accreditation and student graduation requirements, established

precedents, organizational structures, universally accepted practices,

and the paradigm perspectives of five generations of Americans who

believe that this is what school is, period.

A challenge was mounted during the past two decades to the sub-

stance, effectiveness, legitimacy, and necessity of this enormously

educentric paradigm

a paradigm defined by what the system is

and (always) has been rather than by what it should and could be if

student learning and future success in the Information Age

were its

true purpose and priority. That serious, research-based attempt to

fundamentally shift this Educentric Iceberg paradigm to

one of

future-focused learner empowerment was beaten back in 1993 and

1994. What that now-lost paradigm is, how it was lost, what that loss

has cost us, and how it can be regained is the focus of this book. So

please read on with an open paradigm perspective about

an insti-

tution that is totally familiar to us all: American education.

24

10

PARADIGM LOST

CHAPTER 2

THE PARADIGM WE LOST

The Emergence of Paradigm Dissonance

The challenge to our familiar paradigm of schooling surfaced in the

'60s, but most of us didn't notice. The research and theory from that

decade called into question the most fundamental premises and fea-

tures of our prevailing education system and offered possibilities

about its purposes, processes, structures, and culture that had the

potential for literally turning existing patterns of thinking and

practice (the Educentric Iceberg) upside down.

At that time, some 30 years ago, educational researchers such as

James Coleman, John Carroll, Benjamin Bloom, and my long-time

friend James Block provided penetrating insights into the counter,

productive ways schools and classrooms were defined, organized,

and operated. They pointed out that at the time:

The prevailing paradigm of educational thinking and practice

ignores fundamental factors about learners and learning and

actually causes low levels of motivation and achievement

among embarrassingly large numbers of students.

Much higher levels of motivation, learning, and success are

possible for virtually all students.

If the paradigm didn't shift, a whole generation of Americans

would unnecessarily gain far less from their education than they

otherwise could.

Well, that generation has come and gone. We now face a period of even

greater paradigm dissonance than those researchers' ideas initially

generated. The Bureaucratic, Industrial, Agrarian, and Feudal Ages

are over. Yet we remain immersed in their paradigms of learning and

schooling. For, despite the brilliance, simplicity, and appeal of these

researchers' insights, the efforts of numerous reformers and educa-

tors across the country to use and build on them, and the obvious

25

PARADIGM LOST

11

need for improving student achievement in today's Information Age,

our schools continue to experience an assault against most of the

ideas and practices these basic insights spawned.

In many areas of the United States, this assault fostered a climate of

intimidation. State and local superintendents were fired, curriculum

leaders were harassed, board members were challenged and dis-

placed, and principals and teachers were openly told that certain

ideas, terms, and practices were simply not acceptable to some of

their constituents don't use them!

Why did this occur? Because the ideas in question

the core of our

Lost Paradigm

run against the grain of deeply entrenched aspects

of our educational system, our culture, and the beliefs of influential

segments of our society, including us. We're all a bit afraid to melt

the Iceberg, even though many of us recognize that it's outdated and

no longer effective.

How Our Lost Paradigm Took Form

A coherent alternative to our Educentric Iceberg paradigm came

together in fits and starts between the 1960s and the 1990s. Key

con-

ceptual breakthroughs, research data, and innovations in practice

all eventually formed a compelling picture of what learning communi-

ties (as distinct from schools) could be and become. These new

learning communities are grounded in the challenges of Information

Age careers, living, and responsibilities.

My Initial Paradigm Shocks

The Educentric Iceberg paradigm was all I knew or thought possible

when I finished my Ph.D. in 1967; like almost everyone else, I accept-

ed its basic features and underlying systemic characteristics as givens.

But then the first of many "paradigm shocks," or redefining

insights, occurred for me. As a new faculty member at Harvard's

Graduate School of Education with three degrees from the

University of Chicago under my belt, I had already published two

articles in major research journals and thought I had my future

research career well defined.

12

PARADIGM LOST

26

What a surprise I got during my first month there! Along with

hundreds of others, I attended a major conference organized by the

dean, Theodore Sizer, on the pros and cons of the biggest block-

buster to have hit American education up to that point: the Equality

of Educational Opportunity study (EEO 1966), also known widely as

"The Coleman Report."

The report's primary finding was that student characteristics and fam-

ily and neighborhood socioeconomic status factors (SES), not school

variables, accounted for almost all measured differences in student

achievement in America's schools. The blazing headlines surrounding

the study were: "Schools Don't Make a Difference." And those words

got people's attention! Whether the claim was correct or not, this

often-quoted headline left me and millions of others stunned.

Of course schools make a difference, I thought. Look at me. I'm the

son of a garbage collector and hog rancher in Oregon. How do you

think I got here, on a spaceship? Sure, I had some mediocre teachers

in high school, but what about all the great ones? Don't they count?

What does this all mean?

What the data meant, I soon learned, contradicted all of the conven-

tional wisdom about the factors that affected student learning.

Namely, in statistical terms, when you considered the nation as a

whole and all factors simultaneously, virtually none of the factors

that educators had been using for decades as the basis of evaluating

and accrediting school quality was actually correlated with student

learning once student characteristics and family SES factors were

taken into account.

Teachers' degrees and salaries, school and class sizes, the number of

books in the library, the number of microscopes in the lab, and a host of

other variables weren't the things helping students learn. Schools were,

and still are to a large degree, modeling and evaluating themselves

on factors with no direct bearing on the overall achievement of their

students. The keys to school effectiveness lay elsewhere.

Coleman himself spoke to our group. What he told us was the

most shocking and incomprehensible thing I had ever encountered

in education:

PARADIGM LOST

13

Educational opportunity can no longer be defined as stu-

dent access to variables that don't directly affect their

learning and achievement. Opportunity must be measured

in terms of the achievements of students, not how much time

they spend in particular programs or courses. We will have

equality of opportunity when we have equality of learning

outcomes across schools.

What? Schooling and opportunity based on outcomes and not on

access? Was Coleman suggesting that his data called for a totally

shifted paradigm of education?

Yes. Coleman's study results clearly showed that schools could no

longer be measured in terms of time, means, and resources

the

Bureaucratic Culture elements of the Iceberg paradigm. Schools had

to be measured in terms of their outcomes, ends, and results. Like

almost everyone around me, I found his fundamental point too alien

to grasp. Paradigm dissonance had struck.

But a year later I did get it, thanks to my high school buddy and fellow

educator James Block. Block had started at the University of Chicago

as an undergraduate in 1963, where I was pursuing my graduate stud-

ies in education and sociology. In early 1967 I introduced Block to

Benjamin Bloom, chair of Chicago's graduate program in Measurement,

Evaluation, and Statistical Analysis. Block became Bloom's top gradu-

ate assistant just at the time that Bloom was developing and testing the

concept he called "Learning for Mastery." Thanks to Block's exception-

al energy, ability, and commitment, within a few years the concept

was known worldwide as a simple but powerful instructional/reform

model called Mastery Learning (see Block, 1971, 1974, and 1988).

A conversation I had with Block in 1968 flooded my mind with new

insights. Block explained how a paper published by John Carroll in

1963 had captured Bloom's attention because it gave a profound but

ever-so-simple slant to the notions of student aptitude and capacity

for successful learning. Carroll's paper was called "A Model of

School Learning," but, in retrospect, he could have called it "The

Emperor's New School" because it exposed some obvious things

about schools that people just hadn't seen or acknowledged. Three

of its key notions became my next Paradigm Shocks:

14 PARADIGM LOST

28

One paradigm shock was Carroll's argument that aptitude is the rate

at which learners acquire new skill or knowledge, not their ability to

do so. Schools operate as if aptitude and ability are the same thing.

Hence, they inappropriately limit access to higher level curriculum

based on a false notion of differences in student "aptitude."

Another paradigm shock was a corollary to the first: Therefore,

potentially all learners can learn to do clearly defined things equally

well, but the time required to learn to do them will vary because learn-

er's aptitudes vary. So how long it takes to learn something well should

not be confused with acquiring the ability to eventually do it well.

Yet another paradigm shock was that school learning is organized

around fixed, predetermined, one-shot amounts of time

the

Industrial Age delivery system of the Iceberg paradigm that do not

match the learning rates of many students. This structure typically

allows enough time for faster learners, but less time than slower

learners need. Therefore, slower learners might be "failing" because

they aren't given enough time, not because they lack the ability or

motivation to learn what is expected.

Wow! Now those were things I could relate to because I knew from

years of playing the trumpet that how long it took to learn a piece

was unrelated to how well one could eventually learn to perform it.

That's why I practiced diligently and why an orchestra practices as

well. And as I thought about many other examples from my school-

ing and life, Carroll's three paradigm-breaking insights seemed

profound. The simple issue he found about the current model of

schooling was: Time is the constant, and learning is the variable.

But what, wondered Block and I, if we made learning the constant,

and time the variable (just like in real life)?

By the time Block and I had this conversation, Bloom (1968) had

already come up with the answer, namely: You'd have far more students

reaching "mastery" levels on what they learned than you do today.

Bloom had translated Carroll's insights into a fundamental paradigm

shift in instructional practice that he felt could apply to the typical

classroom. The essence of his argument was, instead of giving stu-

dents a typical one-shot block of time and chance to learn something

29

PARADIGM LOST

15

and ending up with highly variable learning results (which immedi-

ately get graded and permanently recorded), why not:

Clearly define at the outset the (high success) learning result

you want;

Make all students eligible for attaining that result; and

Offer students at least a second chance (i.e., a little more time

with additional assistance or "correctives") to achieve it?

In other words, Bloom's initial notion of effective instruction required

educators to reverse the characteristics of conventional practice.

Here, with the benefit of hindsight and some vocabulary changes,

is the essence of his proposed paradigm shift:

From

To

Iceberg Paradigm

Mastery Paradigm

Fixed Time

Flexible Time

Single Opportunity

Multiple Opportunities

Curriculum Focus

Learning Focus

Vague Standards

Criterion Standards

Variable Expectations

Mastery Expectations

Bell-Curve Results

Skewed-Curve Results

With these key factors in mind, Block and others had begun to test

the relative effectiveness of Bloom's strategy, using carefully planned

units of instruction with clearly defined learning goals in regular/

typical classroom settings. Using the Mastery Learning strategy,

teachers had been able to increase the percentage of students

reaching previously defined A-level performance standards on given

units of curriculum by three and four times. In addition, students

were retaining what they learned better than before and were doing

better in subsequent work in that subject, even though their teachers

had gone back to "conventional" teaching.

In other words, when learning expectations were made clear and stu-

dents were given time and support to succeed, the students seemed

to be developing strategies about how to learn that they were then

transferring to other work. Thus, it seemed that a strategy like

Mastery Learning could dramatically increase the percentage of U.S.

16

PARADIGM LOST

30

students doing excellent work, and help students retain and use their

learning at higher levels. Block's conclusion was that persistent, low

levels of achievement were reversible with a different paradigm of

expectations and classroom instruction.

Block was so excited by the results that he declared Mastery

Learning to be the wave of the future in American education. But as

a sociologist, I saw that huge organizational obstacles stood in the

way. With high schools clearly in mind, I pointed out that Mastery

Learning would never "take" for several reasons.

The fixed-time, one-chance nature and structure of our

Carnegie Unit/semester-based credentialing system with its

wide distribution of learning results and assigned grades (the

Feudal Age agenda of the Iceberg Paradigm) is opposite the

clearly defined performance standards and flexible time

required by Mastery Learning and the needs of the individual

learner. When faced with this contradiction, teachers will

experience dissonance, be compelled to operate according to

this deeply institutionalized structure, and compromise the

essence of the Mastery Learning model.

Moreover, Mastery Learning assumes that teachers want all stu-

dents to be successful learners and will, therefore, establish

clear performance goals, criteria, and expectations accordingly.

But this is counteracted by the built-in selection agenda of

schoolsthe devices of tracking, contest learning, comparative

standards, bell-curve grading, and class ranking that are used by

schools and teachers to actually magnify differences in student

learning and performance. This sort-and-select agenda directly

undermines the all-can-learn-well premise of Carroll and Bloom.

I left my conversation with Block with an entirely different perspec-

tive of schooling and the factors that encouraged and inhibited

student learning and motivation.

As I thought about these factors over the next several years, what

Coleman had said made more and more sense. And after many more

conversations with Block and with Henry Levin of Stanford

University; John Champlin, then superintendent of the Johnson City

31

PARADIGM LOST

17

Central Schools in New York; and Wilbur Brookover, the unacknowl-

edged pioneer of Effective Schools research at Michigan State

University; I finally drew three major conclusions about our familiar

Iceberg paradigm of education and the challenge of creating the con-

ditions of authentic learning success for all students. They were:

Seeking to achieve authentic learning success for all students is

a matter of deep personal and organizational purpose and inten-

tion that flies in the face of conventional thinking and practice

(the Iceberg paradigm), and shapes how we view everything

about our system of education. It requires an unwavering focus

on learning, outcomes, performance, results, and the future

not on courses, curriculum, programs, and semesters (the

Bureaucratic Age component of the Iceberg).

Education, despite its rhetoric to the contrary, is a completely

time-based institution. Virtually all of its major features are for-

mally/legally defined by and structured around predetermined

blocks of clock and calendar time (the Industrial Age compo-

nents of the Iceberg). These uniform blocks of time define and

seriously limit the conditions of opportunity, access, and eligi-

bility that most affect students' chances of learning success.

A criterion-defined system is the only achievement system that

maximizes clarity about student learning and performance and

gives individual students full credit for what they ultimately

accomplish. In this system, the actual substance of what is

learned and demonstrated is directly stated in expected outcomes,

assessment measures, reporting devices, and credentialing sys-

tems. Grades, scores, percentages, and other labels only obscure

and distort the actual substance of what students accomplish.

Developing a Common Reform Agenda

of Learning Success

These three conclusions as well as the preceding paradigm shocks

they are based upon became the pillars of my first 15 years' effort to

explain and implement what I call a learning success paradigm of

education. Without ever giving it a name, and without ever formally

18

PARADIGM LOST

:-32

joining forces, Bloom, Block, Ernest Boyer, Brookover, Champlin,

Coleman, John Good lad, Madeline Hunter, Henry Levin, Larry

Lezotte, Bernice McCarthy, Theodore Sizer, myself, and a host of

other school reformers of the '70s and '80s would, I believe, agree to

being unified under this learning success banner.

At its core, the learning success paradigm is learner centered, suc-

cess-oriented, outcome-based, inclusive, expansive, brain-compatible,

systemic, and holistic. And, as it has developed over the past 30

years, it has evolved into being about:

The processes and conditions that promote successful learning,

High expectations for learners,

The dignity of the individual,

Cultivating human potential,

How people learn,

The forms that successful learning take, and

Accurate and substantive assessment and reporting.

Without question, this paradigm rests on a huge base of research

findings and implications; an unassailable foundation of theory,

logic, and common sense; and a wealth of practical examples in all

areas of human endeavor. But one of its strongest features is the

common philosophy of purposes and beliefs that its contributors and

advocates share. Here are examples of some key beliefs and purpose

statements underlying these diverse reform efforts:

All students can learn and succeed, but not on the same day in

the same way.

Successful learning fosters more successful learning, just as

failure promotes more failure.

Schools control some of the conditions that directly influence

student learning, opportunities, and success.

What and whether students learn successfully is more impor-

tant than exactly when or how they learn.

3 3

PARADIGM LOST

19

Challenge, not fear, promotes successful learning

and performance.

The purpose of schools is to equip all students with the

knowledge, skills, and qualities needed for future success.

The distribution of learning results for minority students in

a

school should be no different than for majority students.

Students learn more successfully when they have a clear picture

of what is expected of them and enough time to accomplish it.

It is better to focus on in-depth learning of real significance

than to superficially learn about things of little consequence.

Despite the thrust of this optimistic and empowering philosophy and

the enormous energy devoted to implementing it, this collective

cadre of reformers have barely made a dent in what

appears to be the

most deeply entrenched and anti-empowerment feature of schools:

their selection agenda. Despite all the effort, schools have been

unable to move from what Bloom and Block both call "identifying

and selecting talent" to "fostering and developing" it

the essence

of the learning success approach.

Challenging the Selection Agenda

of Schools

At the heart of the selection agenda of schooling lies the bell

curve

its meaning, role, purpose, and application in both the

instructional and credentialing systems of schools. Decades of

grading practice and "malpractice" in America's high schools and

universities have convinced generations of students and adults that

"the curve" is not only natural, "normal," and to be expected in

instructional situations, it is actually the standard on which grading

and program design should be based. This view has provided the key

rationale for generations of curriculum tracking and for the A through

F distributions of grades.

However, thanks to Bloom's incisive analysis (1976), virtually this

entire cadre of reformers has been able to argue that the bell

curve is

artificially contrived, counterproductive, and unjustified in the face

20

PARADIGM LOST

of far more positive alternatives. The curve, Bloom argued, was

called "normal" because it portrayed the "naturally occurring" pat-

tern of data that resulted when conditions and influencing factors

operated randomly that is, by chance. Chance is the key condition

on which the fundamentals of probability theory and statistics are

based and on which the likelihood of obtaining a normal curve

depends. But, Bloom showed:

Instruction is not a naturally occurring/random phenome-

non! It is a deliberate intervention in what otherwise might

resemble the chance learning processes of students.

Therefore, instruction that is intentional, well planned, and

effective should produce a sharply skewed curve with most of

the students doing very well

not a "normal" one.

That's what "making a difference" and "being effective" mean

intervening effectively in what might otherwise be the random

distribution of results if students attempted to learn on their own.

Therefore, the last thing teachers who want their students to lern

successfully should expect or accept is a bell curve of results.

This mind-blowing, Paradigm-shattering insight served as the techni-

cal and motivational bedrock for all of the major learning success

reform efforts that followed: Mastery Learning, Mastery Teaching,

Effective SchoOls, Outcome-Based Education, Essential Schools,

Accelerated Schools, Success for All Schools, and countless other

variations on these approaches. Their common mantra: Overcoming

the deadly bell curve of expectations and results requires focused,

deliberate, and insightful effort and intervention.

These reformers also realized that the curve and the selection agenda

gave teachers and administrators an open door of non-accountability

concerning student achievement. The prevailing argument was:

"Students with backgrounds or abilities like these will 'naturally'

perform accordingly." But the reformers realized that as long as the

public regarded the curve as legitimate and inevitable, educators

could argue without impunity that if students didn't have the ability or

motivation to take advantage of the opportunities they were providing,

there was nothing they could do to change things. In other words,

35.

PARADIGM LOST

21

Educators saw their job as providing opportunities

for students to learn

the rest (and the result) was

up to the students.

This passive view of educators' roles and responsibilities could

not

be justified in view of Bloom's reasoning and research.

The Key Elements in the

Learning Success Paradigm

Over 15 years elapsed between the time of Coleman's pioneering

research on the Equality of Educational Opportunity and the

emer-

gence of school reform as a growing industry in the early '80s. During

this time the paradigm shocks had begun to create

a consistent

From

Iceberg Paradigm

To

Learning Success Paradigm

Aptitude as Ability

Talent Selection Mission

Bell-Curve Expectations

Calendar Defined

Learner Accountability

Teaching as Coverage

Provides Opportunity

Content-Compatible Methods

Single Modality Instruction

Structured Pacing

Fixed-Time Opportunity

Works Alone

Interpersonal Competition

Comparative Evaluation

Variable Grades

Grading in Ink

Cumulative Achievement

Permanent Records

Time-Based Credit

Calendar Closure

Aptitude as Learning Rate

Talent Development Mission

High-Success Expectations

Outcome Defined

Shared Accountability

Teaching as Intervention

Learns Successfully

Brain-Compatible Methods

Multiple Modality Instruction

Continuous Challenge

Expanded Opportunity

Collaborates

High-Challenge Standards

Criterion Evaluation

Criterion Standards

Assessing in Pencil

Culminating Achievement

Alterable Transcripts

Performance-Based Credit

Outcome Closure

Figure 2.1

The Key Elements in the Learning Success Paradigm

22

PARADIGM LOST

36

picture of the major changes in thinking and practice schools were

going to have to make if learning success was going to become a way

of doing business. Reformers were calling for a shift from the then-

unnamed Iceberg paradigm to the learning success paradigm. The

key elements on which the various reforms focused are described in

Figure 2.1 on page 22.

Clearly, the many shifts listed in Figure 2.1 reflect the issues identi-

fied earlier by Coleman, Carroll, Bloom, and myself as critical to

changing the conditions in which educators and students find them-

selves. A major paradigm shift from Iceberg to learning success was

needed if America's schools were to begin realizing the learning

potential inherent in the students they served. Moreover, by the early

'80s there were isolated examples of these shifts making a large dif-

ference in the achievement levels of students on conventional basic

skills measures.

That is why I and others reacted with such mixed emotions to the

flood of studies and reports issued in 1983 and 1984 by organiza-

tions, task forces, and reformers, including the universally read

A Nation At Risk report of the U.S. Department of Education (1983).

On the one hand, this huge volume of reports drew enormous atten-

tion to the need for serious educational change. But, on the other, most

of what was recommended was framed in the context of the

Educentric Iceberg paradigm

things that represented a completely

conventional perspective of schooling, such as longer days, longer

years, more required courses, thicker books, and harder tests.

The good news, however, was that contained here and there within

these books and reports were some genuinely innovative ideas and

recommendations that reflected many of these Learning Success

paradigm elements (see Spady and Marx 1984). Unfortunately, around

that time, I began to believe that all of this reform work, including my

own, was still missing the boat. Two years later I knew I was right.

Beyond the Learning Success Paradigm

After enormous soul searching and prolonged dialogues with col-

leagues, I finally realized around 1986 that we reformers had been

7

PARADIGM LOST

23

deeply committed to improving student learning outcomes and

suc-

cess, but none of us had clearly defined what either an outcome was

or success meant. We had simply accepted anything that anyone was

teaching or using as an indicator of student learning

as "achieve-

ment," "outcomes," or "success." Neither

we nor implementers of

our ideas in the field had an agreed-upon standard on which to

ground, target, and judge our efforts.

Major turmoil, frustrations, and disagreements

arose when I

broached this issue with other reformers and practitioners, and they

continue to this day in debates about state and national standards.

I believed that we reformers were asking

our constituents to "focus

on outcomes" without having defined what outcomes were, either

conceptually or substantively. Consequently, everything that moved

was being called an outcome: scores on standardized reading and

mathematics tests, teacher-assigned grades,

scores on district subject

matter exams, percentages of students taking and passing honors or

other college-prep courses, Advanced Placement test results, SAT

and ACT scores, dropout rates, college attendance rates, and

so on.

On the one hand, visible improvements

over time in these easily

understood indicators of learning success convinced

a lot of educators,

parents, and policymakers that our particular reforms were working,

and they became motivated to try what

we were suggesting. On the

other hand, however, no one could tell them what

an outcome really

was, or which outcomes were, in theory or practice, more important

than others for students to learn and demonstrate.

But after an enormous amount of analysis, discussion; debate, and

testing of ideas and their implications, an answer finally emerged.

And, like most of the paradigm shocks and insights noted earlier, it

had the potential to turn everything on its head

only more so.

What I realized was:

An outcome is a result

something students can demon-

strate after an instructional event is over. It's not an

accumulation or average of all the things that happen dur-

ing the event

it's the actual culminating demonstration

of what was learned in those previous experiences and activ-

ities. Therefore, its significance is reflected in what matters

and happens to the student after the event, not during it.

24

PARADIGM LOST

38

This initial insight quickly opened the door to several others, all of

which had major implications regarding the paradigm shifts just

described, namely:

Actual demonstrations. An outcome is an actual demonstration of

something what students can actually do with what they

knownot the score, label, grade, or percentage that someone

attaches to the demonstration, but the substance and actions of

the demonstration itself.

Observable competence. A demonstration of competence must be

defined by observable demonstration verbs like "describe" and

"explain" not by commonly used non-demonstration verbs

like "know " and "understand." If you change the demonstra-

tion verb you change the outcome /demonstration} even if the

content remains the same.

Significant outcomes. Significant outcomes are demonstrations of ,

competence that matter to the learner and other major stake-

holders after the learning event is over. These outcomes last

beyond the duration of the event, and matter in the future

after graduation.

Context matters. All demonstration of learning and competence

occur somewhere

in a defined setting or physical context

(e.g., before an audience, out of dOors, before the City Council).

These context factors directly affect the content, form, complex-

ity, and competencies that the demonstration requires.

Complexity varies. Demonstrations of competence can range in

complexity and form from the simple, structured "discrete con-

tent skills" of most school curriculum, assignments, and tests to

the highly complex, open-ended life-role performances required

of adults in the real world (see Figure 2.2 on page 26).

To describe the magnitude of the shock waves that these definitions

and insights generated among U.S. practitioners and policymakers

who took them seriously would be difficult. It required them to be

clear about both the substance and complexities of the learning they

were trying to foster and to transcend their ambiguous world of

points, scores, and grades (see Spady 1994, Chapters 2 and 3).

39

PARADIGM LOST

25

In simple terms, the key messages to those concerned with the

Learning Success paradigm were:

Outcomes must drive curriculum, not the other

way around.

Outcomes are performances, not scores or grades, and they

embody student competence, not just content.

Educators need real words to define the substance of the perfor-

mance they are seeking, including powerful and specific

demonstration verbs.

Students need to execute those verbs, and teachers

are obligat-

ed to teach them howoften over a period of

years.

Outcomes happen at or after the end of major instructional

experiences, and they matter after the experience is over.

Outcomes are complex and significant performance abilities,

not day-to-day tasks, assignments, and tests.

Need for

Significance

Transfer:

& Complexity

Real Life

High

High

Complex Role

Performances

Complex, Unstructured

Task Performances

Higher-Order Skills

Structured Task Performances

Low

Discrete Content Skills

Low

Figure 2.2

The Demonstration Mountain of Learning Outcomes

26

PARADIGM LOST

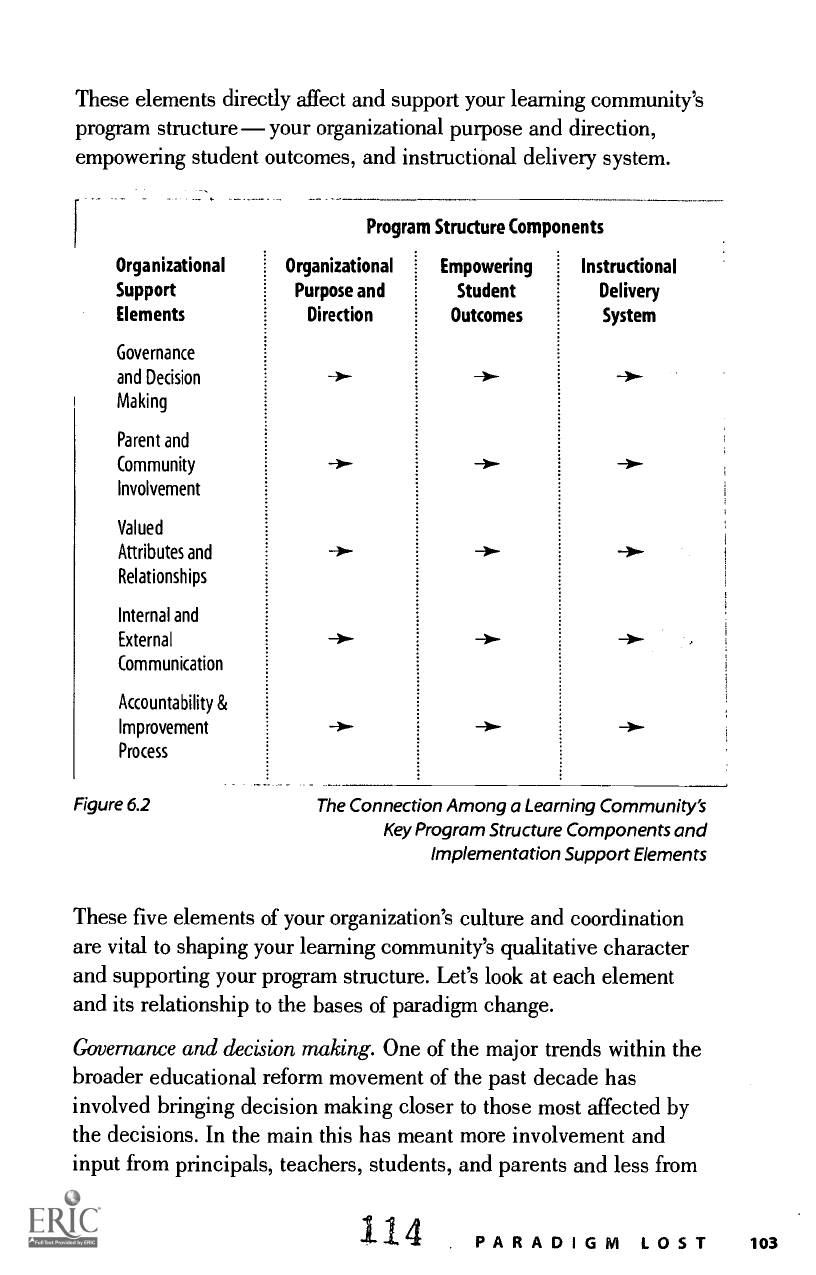

40