Report No. K-TRAN: KU-19-2 ▪ FINAL REPORT ▪ January 2021

Effectiveness of Entertaining, Non-

Traffic-Related Messages on Dynamic

Message Signs

Alexandra Kondyli, Ph.D.

Steven D. Schrock, Ph.D, P.E., F.ITE

Irtiza Rafid Khan

The University of Kansas

i

1 Report No.

K-TRAN: KU-19-2

2 Government Accession No.

3 Recipient Catalog No.

4 Title and Subtitle

Effectiveness of Entertaining, Non-Traffic-Related Messages on Dynamic

Message Signs

5 Report Date

January 2021

6 Performing Organization Code

7 Author(s)

Alexandra Kondyli, Ph.D.

Steven D. Schrock, Ph.D, P.E., F.ITE

Irtiza Rafid Khan

8 Performing Organization Report

No.

9 Performing Organization Name and Address

The University of Kansas

Department of Civil, Environmental & Architectural Engineering

1530 West 15th St

Lawrence, Kansas 66045-7609

10 Work Unit No. (TRAIS)

11 Contract or Grant No.

C2123

12 Sponsoring Agency Name and Address

Kansas Department of Transportation

Bureau of Research

2300 SW Van Buren

Topeka, Kansas 66611-1195

13 Type of Report and Period

Covered

Final Report

August 2018–January 2020

14 Sponsoring Agency Code

RE-0753-01

15 Supplementary Notes

For more information write to address in block 9.

16 Abstract

This research used a fixed-base driving simulator to determine the effects of dynamic message signs

(DMSs) on driver behavior. A DMS notifies drivers with safety, weather, incident, or traffic condition messages.

Recently, however, state Departments of Transportation (DOTs) display safety messages with entertaining

content. The Kansas DOT (KDOT) wanted to assess how these entertaining messages affect driving behavior.

Therefore, this research evaluated the effect of DMS content on driver behavior using a combination of surveys

and driver behavior data obtained from a fixed-base driving simulator.

Existing literature was reviewed to determine similar studies. Based on the literature, which included

results of DMS modeling in driving simulators and DMS effects on driver behavior, a research methodology was

developed. One hundred participants were recruited and screened using an online survey questionnaire that

included messages currently displayed on DMS; feedback on their perceived effectiveness was requested. The

second data collection was done via a driving simulator experiment. The simulator was prepared for the study, the

DMS was set, and events were designed to capture changes in driver behavior and awareness. A total of 60

participants with diverse demographics drove by several DMSs that displayed a variety of messages. Participants

completed a survey at the end of the experiment, and their responses were compared to responses of the online

survey. Behavioral data (speeds, accelerations, gazes, etc.) were then reduced, and statistical analyses were

performed, including hypothesis testing and analysis of variance, to evaluate to what extent the message content

affected driver behavior. The study identified potential messages that were found to effectively affect driver

behavior.

17 Key Words

Dynamic Message Signs, Driver Behavior, Questionn

aires,

Variable Message Signs, Digital Simulation

18 Distribution Statement

No restrictions. This document is available to the public

through the National Technical Information Service

www.ntis.gov.

19 Security Classification

(of this report)

Unclassified

20 Security Classification

(of this page)

Unclassified

21 No. of pages

66

22 Price

Form DOT F 1700.7 (8-72)

ii

This page intentionally left blank.

iii

Effectiveness of Entertaining, Non-Traffic-Related

Messages on Dynamic Message Signs

Final Report

Prepared by

Alexandra Kondyli, Ph.D.

Steven D. Schrock, Ph.D, P.E., F.ITE

Irtiza Rafid Khan

The University of Kansas

A Report on Research Sponsored by

THE KANSAS DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION

TOPEKA, KANSAS

and

THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS

LAWRENCE, KANSAS

January 2021

© Copyright 2021, Kansas Department of Transportation

iv

PREFACE

The Kansas Department of Transportation’s (KDOT) Kansas Transportation Research and New-

Developments (K-TRAN) Research Program funded this research project. It is an ongoing,

cooperative and comprehensive research program addressing transportation needs of the state of

Kansas utilizing academic and research resources from KDOT, Kansas State University and the

University of Kansas. Transportation professionals in KDOT and the universities jointly develop

the projects included in the research program.

NOTICE

The authors and the state of Kansas do not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade and

manufacturers names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the object of

this report.

This information is available in alternative accessible formats. To obtain an alternative format,

contact the Office of Public Affairs, Kansas Department of Transportation, 700 SW Harrison, 2

nd

Floor – West Wing, Topeka, Kansas 66603-3745 or phone (785) 296-3585 (Voice) (TDD).

DISCLAIMER

The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors who are responsible for the facts and

accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the views or the

policies of the state of Kansas. This report does not constitute a standard, specification or

regulation.

v

Abstract

This research used a fixed-base driving simulator to determine the effects of dynamic

message signs (DMSs) on driver behavior. A DMS notifies drivers with safety, weather, incident,

or traffic condition messages. Recently, however, state Departments of Transportation (DOTs)

display safety messages with entertaining content. The Kansas DOT (KDOT) wanted to assess

how these entertaining messages affect driving behavior. Therefore, this research evaluated the

effect of DMS content on driver behavior using a combination of surveys and driver behavior data

obtained from a fixed-base driving simulator.

Existing literature was reviewed to determine similar studies. Based on the literature, which

included results of DMS modeling in driving simulators and DMS effects on driver behavior, a

research methodology was developed. One hundred participants were recruited and screened using

an online survey questionnaire that included messages currently displayed on DMS; feedback on

their perceived effectiveness was requested. The second data collection was done via a driving

simulator experiment. The simulator was prepared for the study, the DMS was set, and events were

designed to capture changes in driver behavior and awareness. A total of 60 participants with

diverse demographics drove by several DMSs that displayed a variety of messages. Participants

completed a survey at the end of the experiment, and their responses were compared to responses

of the online survey. Behavioral data (speeds, accelerations, gazes, etc.) were then reduced, and

statistical analyses were performed, including hypothesis testing and analysis of variance, to

evaluate to what extent the message content affected driver behavior. The study identified potential

messages that were found to effectively affect driver behavior.

vi

Acknowledgments

The authors of this report thank KDOT project monitor Chris Bortz for his guidance and

suggestions.

vii

Table of Contents

Abstract ......................................................................................................................................v

Acknowledgments ..................................................................................................................... vi

Table of Contents ..................................................................................................................... vii

List of Tables ............................................................................................................................ ix

List of Figures ........................................................................................................................... xi

Chapter 1: Introduction ...............................................................................................................1

1.1 Background .......................................................................................................................1

1.2 Objectives ..........................................................................................................................1

Chapter 2: Review of Current Practice ........................................................................................2

2.1 Effect of DMS Messages on Driver Behavior.....................................................................2

2.2 Mechanics of Driving Simulators .......................................................................................5

Chapter 3: Methodology ..............................................................................................................8

3.1 Online and Simulator Surveys ............................................................................................9

3.2 Driving Simulator Experiment ......................................................................................... 10

3.2.1 Participation Recruitment .......................................................................................... 11

3.2.2 Designing Roadway Geometry .................................................................................. 11

3.2.3 Experiment Procedure ............................................................................................... 12

3.2.4 Pilot Testing .............................................................................................................. 15

3.2.5 Data Collection, Reduction, and Statistical Analysis .................................................. 15

Chapter 4: Survey Data Analysis ............................................................................................... 17

4.1 Driving Simulator Survey Data Analysis.......................................................................... 17

4.1.1 Awareness of DMS Messages ................................................................................... 17

4.1.2 Uses of DMS ............................................................................................................. 18

4.1.3 Display of Road Safety Messages .............................................................................. 18

4.1.4 Driver Perception of DMS Messages ......................................................................... 19

4.2 Online Survey Data Analysis ........................................................................................... 23

4.2.1 Awareness of DMS Messages ................................................................................... 23

4.2.2 Uses of DMS ............................................................................................................. 24

4.2.3 Display of Road Safety Messages .............................................................................. 24

viii

4.2.4 Driver Perception of DMS Messages ......................................................................... 26

4.3. Combined Analysis ......................................................................................................... 29

Chapter 5: Driver Behavior Data Analysis ................................................................................. 32

5.1 Speeding Messages .......................................................................................................... 32

5.1.1 “Slow Down” Message .............................................................................................. 32

5.2 Car-Following Event ........................................................................................................ 36

5.3 Move-Over Law .............................................................................................................. 39

5.4 Anti-Texting Messages .................................................................................................... 40

5.5 Summary of Results ......................................................................................................... 42

Chapter 6: Conclusions and Recommendations ......................................................................... 44

6.1 Summary ......................................................................................................................... 44

6.2 Conclusions ..................................................................................................................... 44

6.3 Recommendations and Future Research ........................................................................... 45

References ................................................................................................................................ 47

Appendix A: Survey Questionnaire ........................................................................................... 49

ix

List of Tables

Table 3.1: Profile of Survey Respondents .................................................................................9

Table 3.2: Participant Database .............................................................................................. 12

Table 3.3: Messages Shown in the Driving Simulator ............................................................. 13

Table 4.1: Driver Responses for Displayed DMS Messages (Driving Simulator Survey) ........ 18

Table 4.2: Driver Reactions to Displayed Messages ............................................................... 19

Table 4.3: Message Codes on DMS ........................................................................................ 20

Table 4.4: Driver Perceptions of DMS Messages M1–M14 (Simulator Survey)...................... 20

Table 4.5: Message Codes Not Shown on DMS ..................................................................... 21

Table 4.6: Driver Perceptions of DMS Messages M15–M27 (Simulator Survey).................... 22

Table 4.7: Driver Responses to Displayed DMS Messages (Online Survey) ........................... 25

Table 4.8: Driver Reactions to Displayed Messages ............................................................... 25

Table 4.9: Driver Perceptions of DMS Messages M1–M14 (Online Survey) .......................... 26

Table 4.10: Driver Perceptions of DMS Messages M15–M27 (Online Survey) ........................ 28

Table 4.11: Driver Perceptions (Combined) of Messages Displayed on DMS in Simulator....... 31

Table 5.1: Descriptive Statistics for Avg Speed (Slow Down) ................................................ 33

Table 5.2: Significance in 2-Tailed T-Test for Avg Speed (Slow Down) ................................ 33

Table 5.3: T-Test Results for Avg Speed “Slow Down” Message by Gender Group ............... 34

Table 5.4: T-Test Results for Avg Speed “Slow Down” Message by Age Group .................... 34

Table 5.5: Descriptive Statistics for Avg Speed (Speeding Kills) ............................................ 35

Table 5.6: Significance in 2-Tailed T-Test for Avg Speed (Speeding Kills) ............................ 35

Table 5.7: T-Test Results for Avg Speed “Speeding Kills” Message by Gender Group .......... 36

Table 5.8: T-Test Results for Avg Speed “Speeding Kills” Message by Age Group ............... 36

Table 5.9: Descriptive Statistics for Avg Gap (Give Space, Don’t Tailgate) ........................... 37

Table 5.10: Significance in 2-Tailed T-Test for Avg Gap (Give Space, Don’t Tailgate)............ 37

Table 5.11: Descriptive Statistics for Maximum Speed (Give Space, Don’t Tailgate) ............... 38

Table 5.12: Significance in 2-Tailed T-Test for Maximum Speed (Give Space, Don’t

Tailgate) ................................................................................................................ 39

Table 5.13: Descriptive Statistics for Move-Over Law ............................................................. 40

Table 5.14: Significance in 2-Tailed T-Test for Move-Over Law ............................................. 40

x

Table 5.15: Anti-Texting DMS Messages................................................................................. 41

Table 5.16: Descriptive Statistics for Anti-Texting Messages ................................................... 41

Table 5.17: Significance in 2-Tailed T-Tests for Anti-Texting Messages .................................. 42

Table 5.18: Significance in 2-Tailed T-Test for DMS Messages ............................................... 43

xi

List of Figures

Figure 3.1: Study Tasks ............................................................................................................8

Figure 3.2: Layout of KU Driving Simulator .......................................................................... 10

Figure 3.3: KU Driving Simulator in Action ........................................................................... 11

Figure 3.4: Final Scenario in NADS-ISAT ............................................................................. 14

Figure 3.5: Final Scenario with DMS in NADS-MiniSim ....................................................... 15

Figure 4.1: Exposure to DMS Messages (Driving Simulator Survey)...................................... 17

Figure 4.2: Driver Perceptions of DMS Messages M1–M14 (Simulator Survey) .................... 21

Figure 4.3: Driver Perceptions of DMS Messages M15–M27 (Simulator Survey) .................. 23

Figure 4.4: Exposure to DMS Messages (Online Survey) ....................................................... 24

Figure 4.5: Driver Perceptions of DMS Messages M1–M14 (Online Survey) ......................... 27

Figure 4.6: Driver Perceptions of DMS Messages M15–M27 (Online Survey) ....................... 28

Figure 4.7: Driver Perceptions of DMS Messages M1–M14 (Combined Results) ................... 29

Figure 4.8: Driver Perceptions of DMS Messages M15–M27 (Combined Results) ................. 30

Figure 5.1: Average Speeds and Standard Deviations for the “Slow Down” Message ............. 33

Figure 5.2: Average Speeds and Standard Deviations for the “Speeding Kills” Message ........ 35

Figure 5.3: Average Gap for the “Give Space, Don’t Tailgate” Message ................................ 37

Figure 5.4: Maximum Speeds and Standard Deviations for the “Give Space, Don’t

Tailgate” Message ................................................................................................ 38

Figure 5.5: Move-Over Events Observed for the “Move Over for Law Enforcement”

Message ............................................................................................................... 39

1

Chapter 1: Introduction

1.1 Background

Many transportation agencies throughout the United States use dynamic message signs

(DMSs) to display traffic-related information such as travel times, lane closures, traffic updates,

roadwork warnings, traffic crashes, and inclement weather information to motorists. Several state

Departments of Transportation (DOTs) have recently implemented behavioral traffic safety

messages to attract motorists’ attention, raise awareness, and change driver behavior. These often-

entertaining messages focus on seat belt use, distracted driving, and aggressive driving, as well as

reinforce driving rules. For example, Massachusetts exploited the regional dialect to display “Use

yah blinkah” and “Make yah ma proud, wear yah seatbelt.” Utah displayed “That seat belt looks

good on you,” and one of Tennessee’s popular messages is “Texting and driving, oh cell no.” Iowa

and Missouri DOTs are displaying messages such as “Exit to text it,” or “Get your head out of

your apps.” To raise safety awareness, some DOTs hold contests in which the public is asked to

contribute entertaining messages. Although these messages have gained public approval, no study

has evaluated how effective these messages are in raising public awareness, changing behavior,

and promoting safety.

1.2 Objectives

The objectives of this project were to investigate whether entertaining non-traffic-related

messages influence driver behavior and to specifically identify which messages are most effective.

2

Chapter 2: Review of Current Practice

A thorough literature review was conducted to identify existing research related to DMS

messaging. Several publications, theses, and books were obtained using resources from the

University of Kansas Library and online library databases such as Google Scholar, Transportation

Research International Documentation (TRID), ScienceDirect, DBPIA, JSTOR, and IEEE Xplore

Digital Library.

2.1 Effect of DMS Messages on Driver Behavior

The number of state transportation agencies posting safety messages on DMS has increased

over the last few years. Several studies have proven that these safety messages potentially change

driver behavior, including small samples of traffic data analysis that show speed changes when

drivers approach an active DMS. Although the overall findings from these reports support the use

of DMS to disseminate highway safety messages, more research is needed to validate perceptions

noted in the surveys, and more field studies are necessary to confirm long-term impacts of DMS

use to convey safety messages about driver behavior and traffic safety.

On February 9, 2006, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) issued a policy

memorandum that allows driver-safety-focused messages to be displayed on a DMS. The

memorandum recommended that messages should be kept current and related to a specific

campaign, and the period that a specific message is displayed for a safety campaign should be

limited to a few weeks. More recently, DMSs have been used in public campaigns to raise

awareness of safe driving behavior and promote roadway safety. Messages are typically focused

on five common, dangerous behaviors: drowsiness, distractions, aggression, alcohol or drug

impairment, and unrestrained driving. More recently, the displayed messages also included the

state-specific number of traffic fatalities year-to-date.

A recent study by Mitran, Cummins, and Smithers (2018) reviewed the literature and

documented the existing practice of placing safety campaign messages on DMSs to determine if

they effectively influence driver behavior and provide safety benefits to the public. The authors

reviewed reports from states that currently utilize safety message campaigns and display these

messages on DMSs. The findings were based on surveys that were administered to the general

3

public and solicited their input on the effectiveness of specific messages. Although the report is

not detailed and specific data on the sample sizes or detailed survey questionnaires are missing,

the authors claimed that, overall, the use of DMSs for safety campaigns effectively changed driver

behavior. In addition, the results suggested that drivers most often read and process DMS messages

with informative, text-only content with assertive, cautionary language. However, once installed,

the researchers warned, DMSs should be treated as one of many communication channels, meaning

DMSs are likely to be underutilized if they are used only for safety campaigns.

Simulation studies have also been used to evaluate the effect of DMS messages in a

controlled environment. Vaughn, Abdel-Aty, Kitamura, and Jovanis (1992) performed a study

using a PC-based simulation program to investigate how route choice decisions are affected by

Advanced Traveler Information Systems displayed on DMSs. Results showed that males are more

likely to follow advice provided by the system, and drivers are more willing to obey the system

for a route change if the route includes a freeway. Similarly, a study by Adler and Kalsher (1994)

used a simulator program called FASTCARS to investigate the effects of traffic advisory and route

guidance information on en-route behavior and travel performance. Information on simulated

traffic speeds and route guidance was provided, and driver travel speeds were collected. Their

findings showed that providing subjects with guidance information resulted in decreased travel

times because drivers did not have to utilize trial-and-error practices.

Benson (1996) evaluated motorist attitudes regarding the content of DMS messages,

revealing that respondents preferred DMS messages that are simple, reliable, and useful. Messages

with exact locations of crashes and time-tagging traffic information received high levels of

response. Using theoretical calculations and motorists’ experiences, the results showed that a DMS

should not use more than two message screens. Other researchers have discovered that a single

message screen is preferable and that incorrect information can have negative consequences on

DMS effectiveness (Miller, Smith, Newman, & Demetsky, 1995).

DMSs have been incorporated into many metropolitan cities worldwide in the hope that

the information provided by these signs will alter driver behavior in a positive manner (Emmerink,

Nijkamp, Rietveld, & Van Ommeren, 1996). In 2001, results of a European study on the

comprehension of pictograms for DMSs demonstrated the difficulty of finding images that could

4

be readily understood (Luoma & Rämä, 2001). Another study investigated the effectiveness of

safety campaign messages, such as “Watch Your Speed,” that were randomly displayed on DMSs

throughout the United Kingdom’s motorway network (Jamson & Merat, 2007). The study focused

on the effects of individual messages and how their presence influences driver behavior towards

more critical tactical incident messages (TIMs) that warn of imminent hazards. The study used the

University of Leeds Driving Simulator, which recorded eye gazes via a Seeing Machines faceLAB

v4 eye tracker within the simulator to determine if drivers read the message. Research results

suggested that, although DMSs with safety campaign messages did not significantly affect driver

behavior, they still produced safety benefits. When used sporadically, they improved driver

alertness and acted as favorable reminders of safe driving practices. Evidence in this study also

suggested that responses to TIMs are timelier if drivers are accustomed to reading such messages

on DMSs; if not, drivers tend to ignore them.

Tay and de Barros (2008) studied driver perceptions of DMS safety messages. Focus group

discussions with transportation engineers and road safety experts were conducted, and qualitative

analysis was followed by a questionnaire survey of two samples of drivers to examine opinions of

DMS displays and self-reported reactions to several safety messages related to speeding. In

addition to standard demographic and driving information, the survey gathered data on the

respondents’ exposure to various types of messages displayed on a DMS, and the respondents were

asked to identify all the types of messages they recalled seeing on the DMS.

The first sample, which totaled 94 participants, primarily consisted of students in

transportation engineering courses at the University of Calgary, with friends and colleagues of the

research team comprising a small proportion of participants. The second sample consisted of 163

drivers who stopped at the Gasoline Alley, a popular stopover point on Highway 2 between Calgary

and Edmonton, cities in Alberta, Canada. Reports were prepared based on driver attention and

reactions to messages displayed on DMSs along the highway. Most drivers (85.8%) responded that

they looked at the displayed messages, and 69.9% reported that they thought about the displayed

messages. These encouraging results show that drivers are aware of the messages and contemplate

them, indicating that DMS is an effective communication device. Coupled with earlier findings

that most drivers support the display of other non-traffic-related information, the conclusion was

5

made that displaying non-traffic-related information does not negatively impact the effectiveness

of displayed traffic-related information.

Most participants added that the current messages are very “soft” and thus not likely to

grab the attention of drivers. They suggested that “hard-hitting” messages are harder to ignore.

Several participants also suggested that messages should be more current and specific, such as “xx

people were killed this year” or “xx% of the drivers today are speeding.” A few participants also

suggested relevant messages such as “your speed is xxx km/h - slow down” or “you are following

too closely.” Most participants felt that direct, immediate warnings more effectively grab drivers’

attention than general “soft-soft” messages. The study also found that most drivers looked at the

displayed messages and could recall many of the previous messages.

Tay and de Barros (2010) also examined the effectiveness of anti-speeding messages on

driver attitudes and traffic speed on an inter-city highway. “Speeding will catch up to you” and

“Don’t save time, save lives” messages were used to measure driver behavior. A questionnaire

survey, developed, and administrated to 97 drivers, gathered information on driver exposure to and

recollection of the various types of information displayed on DMSs; driver attitudes towards the

messages were recorded using a standard 5-point Likert scale. The authors also performed an on-

road test, based on a simple quasi-experimental design methodology, that provided valid

interference on the effect of a particular message by measuring and comparing traffic speeds when

drivers were exposed to the message and when they were not exposed to the message. This study

showed that the messages had a relatively small, albeit beneficial effect on driver behavior and on-

road traffic speed.

2.2 Mechanics of Driving Simulators

Driving simulators virtually represent the dynamics of a vehicle and surrounding

environment without physically jeopardizing test subjects (Capustiac & Napoca, 2011). The goal

of the driving simulator is to immerse drivers into a virtual environment generated by computer

rendering. While driving in a particular scenario, the virtually generated environment moves with

respect to the vehicle, creating a perception of motion. Several vehicle manufacturers and

educational institutions use driving simulators to research driver behavior, body position, human-

6

vehicle interactions, roadway geometrics, and driver assistance systems. Because they pose no

physical threat to individuals, simulators can efficiently determine driving risks.

Driving simulators are generally categorized in terms of cost and number of degrees of

freedom (DOFs), or the direction in which motion is free to occur. For example, a simulator with

three DOFs can demonstrate motion in three planes: x-axis, y-axis, and z-axis. As the number of

DOFs increases, the driving experience becomes more realistic, but the cost of the driving

simulator also increases. Simulators are typically classified as low level, mid-level, or high-level;

low-level simulators are usually fixed-based (FB) simulators (Slob, 2008).

Driving simulators have existed since the early 1950s when vehicle manufacturers started

designing simulators to test designs. In the early 1970s, Volkswagen built their first driving

simulator with a 3-DOF (yaw, roll, and pitch) motion system (Slob, 2008). Mazda was the next

vehicle manufacturer to develop a 4-DOF (yaw, roll, pitch, and surge) system in 1985. Around the

same period, Daimler-Benz introduced a 6-DOF system with a 180-degree view in a hydraulic

hexapod (Slob, 2008). Ford Motor Company introduced their 6-DOF simulator, Virttex, in 1994.

In addition to yaw, roll, and pitch, Ford’s simulator could also sway, heave, and surge. Renault

implemented a similar system in 2004 (Slob, 2008). Kookmin University in South Korea

developed a 6-DOF system in a single-seat simulator, and in 2001, the system was replaced with

a full-car chassis and a 2-DOF motion platform. The Kookmin University Simulator can also

generate effects such as rumble strips and speed bumps (Lee, Sung, Lee, Kim, & Cho, 2007).

Highly sophisticated simulators (high-level simulators), such as the Toyota Driving

Simulator at the Higashi-Fuji Technical Center in Susono, Japan, and the National Advanced

Driving Simulator (NADS) at the University of Iowa in the United States, provide realistic,

immersive driving experiences. Both Toyota and NADS simulators have 13 DOFs with a fully

enclosed hexapod and a 360

o

horizontal view (Slob, 2008).

Compared to high-level simulators, low-level simulators are not fully capable of delivering

realistic immersion into a virtual driving environment. In addition, low-level simulators are more

prone to effects such as simulator sickness, which occurs because the simulator lacks motion cues.

Humans perceive motion through skin pressure and balance organs in the ear (Capustiac &

Napoca, 2011). When the human body is subject to a simulator, however, the eyes register visual

7

cues, but the ears and skin do not register any movement (motion cues), leading to a lack of motion

perception. The most common symptoms of simulator sickness are nausea, headaches, vomiting,

and sweating. Therefore, Kemeny and Panerai (2003) recommended a minimum horizontal field

of view (FOV) of 120° for drivers to accurately perceive speed with respect to moving images in

a driving simulator.

8

Chapter 3: Methodology

This research used surveys and driving simulator experiments to evaluate the effectiveness

of non-traffic-related messages for changing driver behavior and promoting safety. Participants

recruited for the driving simulator at the University of Kansas (KU) were given a screening

questionnaire that gathered information regarding their demographics and driving behavior.

Simulator scenarios were created, including selecting and setting up DMS messages, and,

following completion of the draft scenario, pilot testing was carried out to detect any discrepancies

missed by the designer. Figure 3.1 highlights the main tasks performed in this study.

Figure 3.1: Study Tasks

Two additional surveys were developed to gauge drivers’ preferences regarding the DMS

and perceived effectiveness of specific messages. The first survey was given online, and the second

survey was administered after the driving simulator study was completed. Data were analyzed

9

using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) software (IBM, 2011), and data analysis

included paired t-tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA).

3.1 Online and Simulator Surveys

This study utilized two surveys to examine driver perceptions of DMS use and self-reported

reactions to the displayed messages. One survey was given to 120 participants online via social

media. The other survey was administered to 60 drivers after they finished simulated driving. Both

surveys included the same questions (Appendix A).

Table 3.1 shows the profile of respondents from the online and driving simulator surveys.

As shown in the table, 65 (54.2%) of the 120 respondents in the online survey were male and 55

(45.8%) were female. In addition, results showed that drivers aged 18–49 years were

overrepresented, and the sample consisted of a higher proportion of drivers with more than 10

years of driving experience. Of the 60 respondents in the driving simulator survey, 31 (51.70%)

were male and 29 (48.3%) were female. Again, drivers aged 18–50 years were overrepresented in

the total sample, which also consisted of a higher proportion of drivers with more than 10 years of

driving experience.

Table 3.1: Profile of Survey Respondents

Online Survey Driving Simulator Survey

Gender

Male

54.2% 51.7%

Female

45.8%

48.3%

Age (yrs)

18–25

43.3

41.7

26–49

39.2 41.7

50+ 19.2 16.7

Driving Experience (yrs)

1–5

33.3 36.7

6–10

16.7

16.7

>10

50.0 46.7

10

3.2 Driving Simulator Experiment

The KU driving simulator is a fixed-based simulator in an Acura MDX chassis (half cab).

As shown in Figure 3.2 and Figure 3.3, the simulator provides a 170° horizontal FOV, with three

forward screens and one rear screen. The rear screen renders the view of both sideview mirrors

and the rearview mirror, providing an immersive driving experience. The simulation run and

respective data were recorded on the MiniSim (NADS, 2015) computer, while the video of each

participant’s drive was captured on a video-capture computer. Eye-tracking equipment was used

to collect eye-tracking data from the participants, and the eye-tracking and simulation data were

synchronized.

Figure 3.2: Layout of KU Driving Simulator

11

Figure 3.3: KU Driving Simulator in Action

3.2.1 Participation Recruitment

Outlets such as advertisements at KU, the Lawrence Public Library, the Department of

Motor Vehicles (DMV), churches, and social media platforms (Facebook and LinkedIn) were used

to distribute the survey to the general public in Kansas. In addition, requests for participation were

sent to people who had previously participated in human factors-related research. A web-based

prescreening questionnaire collected demographics and information pertaining to current driving

habits from perspective participants. The driving simulator study and related material were

approved by the University of Kansas Human Research Protection Program (HRPP). A total of

201 participants showed interest in participating in the driving simulator study, and 60 participants

were invited to participate. The selected participants’ database is shown in Table 3.2.

3.2.2 Designing Roadway Geometry

This study utilized the tile mosaic tool (TMT) to generate roadway alignments and render

the virtual environment (NADS, 2016). The program used square tiles with dimensions of 660 ft

by 660 ft, consisting of virtual environment features such as pavement, shoulder, vegetation,

markings, and geometry. The square tiles could be combined to form a continuous roadway layout;

a four-lane divided highway with a grass median, 70 mph speed limit, and several DMSs were

created for this study. The virtual driving scenario consisted of a typical freeway with straight and

curved segments. The total length of the freeway, including two interchanges, was approximately

60 miles.

12

Table 3.2: Participant Database

No.

ID

Age

Gender

No.

ID

Age

Gender

1

V001

28

M

31

V039

32

M

2

V002

19

F

32

V040

21

M

3

V003

29

M

33

V042

20

F

4

V004

18

M

34

V043

54

M

5

V005

26

F

35

V044

42

F

6

V007

22

M

36

V045

18

M

7

V008

19

F

37

V046

21

M

8

V011

28

M

38

V047

62

M

9

V012

24

F

39

V048

56

F

10

V016

20

M

40

V049

46

M

11

V017

28

M

41

V051

37

F

12

V018

42

F

42

V052

77

M

13

V019

21

M

43

V053

21

F

14

V020

38

F

44

V054

31

F

15

V021

46

M

45

V055

20

F

16

V022

26

F

46

V056

21

M

17

V023

23

M

47

V057

64

F

18

V024

21

M

48

V058

21

M

19

V025

34

F

49

V059

24

F

20

V027

39

F

50

V060

25

M

21

V028

24

F

51

V061

18

F

22

V029

21

F

52

V062

26

M

23

V030

50

F

53

V063

55

F

24

V031

18

M

54

V064

21

F

25

V033

37

M

55

V065

34

F

26

V034

60

M

56

V066

34

F

27

V035

28

M

57

V067

18

M

28

V036

28

M

58

V068

31

F

29

V037

30

M

59

V069

50

F

30

V038

50

F

60

V070

29

M

3.2.3 Experiment Procedure

The research team used NADS-ISAT and NADS-MiniSim software programs to create

simulated scenarios of roadways with DMSs that displayed specific non-traffic-related content.

KDOT determined the exact content of the displayed messages in order to test messages that were

thought to specifically influence driver behavior. Each DMS was spaced approximately 3 miles

apart, and drivers drove past approximately 20 DMSs throughout the simulation. The entire

duration of the experiment was approximately 60 min.

13

In the first part of the roadway network, drivers underwent a 5-minute practice session that

resembled experimental motorway conditions. No DMS was present during the practice drive so

participants could acclimate to the driving simulator and the driving process. Screening for

simulation sickness was also carried out, and participants with severe symptoms were excluded

from the study. In the second part of the network, DMSs were introduced into the simulated

network, and driver data such as speed control, lane changing, and gap acceptance were collected

to investigate the impact of message content on driving behavior. The four general DMS message

categories were texting and driving, move-over law, car-following event, and anti-speeding

messages. A total of 14 messages were selected, and most were repeated at least twice to determine

if message repetition changed driver behavior. Since some of the selected messages were related

to texting while driving, participants were provided with the Messenger app that was installed on

a cellphone and placed inside the car. Messages were sent to them from a laptop, and participants

were advised to attempt to reply to the text messages if they felt comfortable while driving the

simulator. The displayed messages are shown in Table 3.3.

Table 3.3: Messages Shown in the Driving Simulator

Type of

Message

Message

Texting

Steering Wheel: Not A Hands-Free Device

Pay Attention and Just Drive

Drive Like Your Life Depends on It

Get Your Head out of Your Apps

One Text or Call Could Wreck It All

Even Texting Drivers Hate Texting Drivers

No Text Is Worth A Life

What’s More Important, Your Text or Your Life?

Don’t Let Texting Blind You

Texting & Driving—It Can Wait

Tailgating

Give Space, Don’t Tailgate

Move-Over Law

Move Over for Law Enforcement and Maintenance Workers

Speeding

Speeding Kills

Slow Down

In each driving scenario, participants had to drive from the starting point to the end point.

The distance from the starting point to the first DMS location was approximately 1,500 m, which

allowed drivers to accelerate to typical driving speeds. In addition, to make the driving scenarios

14

more realistic, several vehicles were modeled as ambient traffic. Because the research team

hypothesized that drivers would change their behavior once they read the message signs,

statistically significant differences in driver speed, acceleration, and gaps were investigated before

and after drivers looked at (and read) the message signs. Upon completion, participants were asked

to answer questions regarding the usefulness and perceived effectiveness of the DMS content.

Figure 3.4 and Figure 3.5 show final scenarios from the NADS-ISAT and NADS-MiniSim

software programs, respectively.

Figure 3.4: Final Scenario in NADS-ISAT

15

Figure 3.5: Final Scenario with DMS in NADS-MiniSim

3.2.4 Pilot Testing

Following the initial scenario design, three test participants with no prior exposure to the

simulator were invited to drive the scenarios. Based on their feedback, modifications were made

to the events within the scenario, such as changing traffic speed, adjusting distances between

vehicles, and fixing unnoticed graphics bugs in the simulated environment.

3.2.5 Data Collection, Reduction, and Statistical Analysis

The scenarios were run using the NADS MiniSim software, which directly linked to

hardware inputs such as steering wheel, accelerator pedal, brake pedal, and gear selector (NADS,

2015). All data collection outputs were stored in a data acquisition file, accessible through

MATLAB (The MathWorks, Inc., 1996). A MATLAB plugin, the data acquisition viewer, provided

by NADS, was used to select required data variables from each scenario. Filtered and sorted data

included variables such as vehicle speed, lateral position, distance to lead vehicle, deceleration

rate, and video data. After extracting the required variables, data were exported to Microsoft Excel

for further sorting into individual events. Each event was uniquely numbered in ISAT between 1

and 20, allowing easy identification during sorting. The data variables were then organized by

participant ID and age group.

16

The surveys and driving simulator data were used to assess whether drivers believed that

the message content had affected their behavior and whether the message content had affected their

driving behavior and improved safety awareness. Statistical tests were used for assessment. For

statistical analysis, the null hypothesis was that there was no significant difference between driver

behavior and awareness of individuals driving before and after seeing the DMS message, as

verified by a 2-tailed paired sample t-test at a confidence level of 95%. ANOVA was also

conducted to identify significant differences in data variables between age groups or genders.

17

Chapter 4: Survey Data Analysis

4.1 Driving Simulator Survey Data Analysis

4.1.1 Awareness of DMS Messages

Upon completion of the driving simulator experiments, participants were asked to complete

a survey pertaining to the perceived effectiveness of DMS messages. In addition to standard

demographics and driving information, the survey gathered data on the respondents’ exposure to

various types of DMS messages. Participants were asked to indicate all the types of messages they

recalled seeing on a DMS. As shown in Figure 4.1, most respondents remembered seeing safety-

related messages; in fact, the positive response rate was 89%, followed by construction-related

information (42%), crash information (40%), travel-time information (36%), and weather-related

messages (21%). These results may reflect the relative amount of exposure or number of times

these messages were displayed. Overall, most drivers recalled seeing the DMS messages, which

indicates that DMS is an effective communication device.

Figure 4.1: Exposure to DMS Messages (Driving Simulator Survey)

18

4.1.2 Uses of DMS

A standard 5-point Likert scale was used to elicit drivers’ opinions on the various displayed

messages. As shown in Table 4.1, most respondents appreciated the display of information

regarding weather, real-time traffic, reminders not to tailgate, general safety messages, and

reminders of driver courteousness. Their opinions on anti-speeding messages, however, were

somewhat neutral.

Table 4.1: Driver Responses for Displayed DMS Messages (Driving Simulator Survey)

Driver Responses to DMS

SD

(%)

D

(%)

N

(%)

A

(%)

SA

(%)

Mean

(1–5)

It is a good idea to remind drivers….

not to follow too closely on the road. 0.00 1.67 28.33 50.00 20.00 3.88

to be courteous on the road. 1.67 8.33 26.67 50.00 13.33 3.65

of hazardous weather conditions. 0.00 0.00 3.33 30.00 66.67 4.63

It is a good idea to display….

general safety messages on highway

message boards.

1.67 6.67 25.00 41.67 25.00 3.82

anti-speeding messages on highway

message boards.

1.67 10.00 36.67 35.00 16.67 3.55

drunk-driving messages on highway

message boards.

5.00 5.00 18.33 50.00 21.67 3.78

anti-texting-and-driving messages on

highway message boards.

1.67 5.00 15.00 41.67 36.67 4.07

seat belt-use messages on highway

message boards.

0.00 6.67 20.00 43.33 30.00 3.97

weather-warning messages. 1.67 3.33 5.00 40.00 50.00 4.33

Note: Mean calculated using strongly disagree (SD) = 1, disagree (D) = 2, neutral (N) = 3, agree (A) = 4, and

strongly agree (SA) = 5

4.1.3 Display of Road Safety Messages

In order to evaluate the effectiveness of the DMS for changing driver behavior, drivers

initially were asked about the attention they paid to the messages. Second, in order to gauge

behavioral change, examples of more specific types of messages were presented to survey

respondents to determine changes in driving behavior. Table 4.2 reports the results of drivers’

attention and reactions to the messages. Most drivers (88.3%) reported that they looked at the

displayed messages, and 85% reported that they thought about the displayed messages. Moreover,

since a majority of the respondents agreed that road safety messages should be displayed but were

19

not overly enthusiastic about anti-speeding messages, displaying other safety messages may be

more effective than displaying anti-speeding messages.

Table 4.2: Driver Reactions to Displayed Messages

Respond to the Following Statements:

SD

(%)

D

(%)

N

(%)

A

(%)

SA

(%)

Mean

(1–5)

I look at the information on highway message

boards when it is displayed.

0.00 3.33 8.33 51.67 36.67 4.22

I think about the information displayed on highway

message boards.

0.00 0.00 15.00 50.00 35.00 4.20

Behavioral Effects of Road Safety Messages

Remind me to check my following distance 3.33 13.33 33.33 40.00 10.00 3.40

Reduce my likelihood of speeding 3.33 13.33 31.67 36.67 15.00 3.47

Remind me not to text while driving 3.33 6.67 20.00 50.00 20.00 3.77

Remind me not to drive after consuming alcohol 10.00 3.33 18.33 40.00 28.33 3.73

Remind me to pay more attention while driving 3.33 3.33 16.67 55.00 21.67 3.88

Remind me to always use the seat belt while

driving

3.33 8.33 13.33 50.00 25.00 3.85

Remind me to move over for law enforcement or

maintenance workers

3.33 3.33 11.67 46.67 35.00 4.07

Note: Mean calculated using strongly disagree (SD) = 1, disagree (D) = 2, neutral (N) = 3, agree (A) = 4, and

strongly agree (SA) = 5

4.1.4 Driver Perception of DMS Messages

4.1.4.1 Messages Shown in Simulator (M1-M14)

Upon completion of the experiment, participants were surveyed regarding their thoughts

about the 14 messages shown on the DMS during the simulator experiment. The message codes

are shown in Table 4.3.

To confirm these survey responses, drivers’ opinions were elicited using a standard 5-point

Likert scale. As shown in Table 4.4 and Figure 4.2, most participants (90%) thought that the

message “Move Over for Law Enforcement and Maintenance Workers” was most effective,

followed by “Give Space, Don’t Tailgate” (81.67%) and “No Text Is Worth A Life” (80%).

20

Table 4.3: Message Codes on DMS

Code Messages

M1 Steering Wheel: Not A Hands-Free Device

M2 Pay Attention and Just Drive

M3 Give Space, Don’t Tailgate

M4 Move Over for Law Enforcement and Maintenance Workers

M5 Speeding Kills

M6 Slow Down

M7 Drive Like Your Life Depends on It

M8 Get Your Head out of Your Apps

M9 One Text or Call Could Wreck It All

M10 Even Texting Drivers Hate Texting Drivers

M11 No Text Is Worth A Life

M12 What’s More Important, Your Text or Your Life?

M13 Don’t Let Texting Blind You

M14 Texting & Driving—It Can Wait

Table 4.4: Driver Perceptions of DMS Messages M1–M14 (Simulator Survey)

Messages

NAE

(%)

NSE

(%)

N (%)

SE

(%)

VE

(%)

Mean

(1–5)

Steering Wheel: Not a Hands-Free Device 1.67 13.33 28.33 23.33 33.33 3.73

Pay Attention and Just Drive 5 8.33 30 33.33 23.33 3.62

Give Space, Don’t Tailgate 1.67 5 11.67 46.67 35 4.08

Move Over for Law Enforcement and

Maintenance Workers

1.67 1.67 6.67 31.67 58.33 4.43

Speeding Kills 0 13.33 21.67 35 30 3.82

Slow Down 3.33 3.33 23.33 35 35 3.95

Drive Like Your Life Depends on It 0 16.67 33.33 23.33 26.67 3.60

Get Your Head out of Your Apps 8.33 11.67 23.33 21.67 35 3.63

One Text or Call Could Wreck It All 0 13.33 26.67 31.67 28.33 3.75

Even Texting Drivers Hate Texting Drivers 8.33 16.67 25 20 30 3.47

No Text Is Worth A Life 1.67 3.33 15 48.33 31.67 4.05

What’s More Important, Your Text or Your

Life?

5 13.33 21.67 35 25 3.62

Don’t Let Texting Blind You 6.67 16.67 38.33 20 18.33 3.27

Texting & Driving—It Can Wait 0 18.33 33.33 30 18.33 3.48

Note: Mean calculated using not-at-all effective (NAE) = 1, not-so effective (NSE) = 2, neutral (N) = 3,

somewhat effective (SE) = 4, and very effective (VE) = 5

21

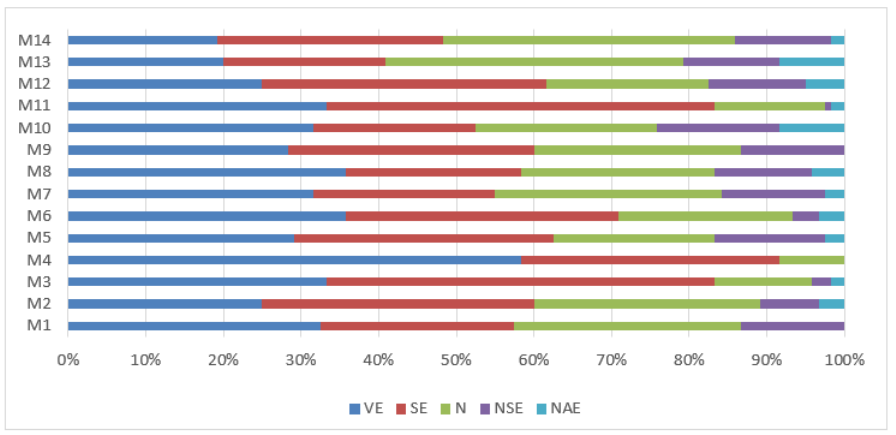

Note: VE: very effective, SE: somewhat effective, N: neutral, NSE: not so effective, NAE: not at all effective

Figure 4.2: Driver Perceptions of DMS Messages M1–M14 (Simulator Survey)

4.1.4.2 Other Messages

Participants were also asked about the effectiveness of 13 messages that were not shown

in the simulator study. The message codes (M15–M27) are shown in Table 4.5.

Table 4.5: Message Codes Not Shown on DMS

Code

Messages

M15 Click It or Ticket

M16 Click It, Don’t Risk It

M17 Buckle Up, Every Trip, Every Time

M18 Head Up Phone Down

M19

A Steering Wheel Is Not A Hands-Free Device

M20

Slow Down, Ride Like Your Life Depends on It

M21 Speeding Kills—Arrive Alive

M22 Tomorrow Is the Reward for Safe Driving

M23 Don’t Text and Drive, It Can Wait

M24 Just Drive

M25 You Drink. You Drive. You Lose.

M26 Drunk Driving—Don’t Let Cheers Turn into Tears

M27 Drive High Get a DUI

22

As with the first messages, drivers’ opinions about the messages were elicited using a

standard 5-point Likert scale. As shown in Table 4.6 and Figure 4.3, most participants (80%)

thought that the message “Speeding Kills—Arrive Alive” was most effective, followed by “Click

it or Ticket” (78.33%) and “You Drink. You Drive. You Lose.” (71.67%).

Table 4.6: Driver Perceptions of DMS Messages M15–M27 (Simulator Survey)

Messages

NAE

(%)

NSE

(%)

N

(%)

SE

(%)

VE

(%)

Mean

(1–5)

Click It or Ticket 3.33 5 13.33 36.67 41.67 4.08

Click It, Don’t Risk It 6.67 11.67 28.33 41.67 11.67 3.40

Buckle Up, Every Trip, Every Time 6.67 13.33 25 28.33 26.67 3.55

Head Up Phone Down 0 6.67 25 43.33 25 3.87

A Steering Wheel Is Not A Hands-Free

Device

1.67 16.67 26.67 33.33 21.67 3.57

Slow Down, Ride Like Your Life Depends

on It

6.67 8.33 25 38.33 21.67 3.60

Speeding Kills—Arrive Alive 1.67 3.33 15 48.33 31.67 4.05

Tomorrow Is the Reward for Safe Driving 6.67 15 18.33 40 20 3.52

Don’t Text and Drive, It Can Wait 3.33 18.33 21.67 38.33 18.33 3.50

Just Drive 16.67 11.67 30 25 16.67 3.13

You Drink. You Drive. You Lose. 1.67 6.67 20 41.67 30 3.92

Drunk Driving—Don’t Let Cheers Turn

into Tears

5 8.33 23.33 36.67 26.67 3.72

Drive High Get A DUI 6.67 5 25 40 23.33 3.68

Note: Mean calculated using not-at-all effective (NAE) = 1, not-so effective (NSE) = 2, neutral (N) = 3,

somewhat effective (SE) = 4, and very effective (VE) = 5

23

Note: VE: very effective, SE: somewhat effective, N: neutral, NSE: not-so effective, NAE: not-at-all effective

Figure 4.3: Driver Perceptions of DMS Messages M15–M27 (Simulator Survey)

4.2 Online Survey Data Analysis

4.2.1 Awareness of DMS Messages

The online survey gathered data on the respondents’ exposure to various messages

displayed on DMSs. As shown in Figure 4.4, most respondents (85%) reported that they had seen

safety-related messages displayed on DMSs. Subsequently, 45% of respondents reported seeing

crash-related information, 40% reported seeing construction messages, 33% had seen travel-time

information, and only 25% remembered seeing weather-related messages. Since traffic incidents

and adverse weather reports are relatively infrequent, it is not surprising that more drivers recalled

seeing safety messages. Therefore, in terms of awareness and recall, most drivers recalled seeing

DMS messages.

24

Figure 4.4: Exposure to DMS Messages (Online Survey)

4.2.2 Uses of DMS

As shown in Table 4.7, most survey respondents recognized the benefits of displaying

information regarding weather, real-time traffic, reminders not to tailgate, general safety messages,

and reminders of driver courteousness. Similar to the results obtained after the simulation study,

respondents’ opinions on the display of anti-speeding messages, however, were somewhat neutral.

These results show that most drivers support the use of DMS for the display of other types of

messages besides traffic information.

4.2.3 Display of Road Safety Messages

Table 4.8 reports the results of drivers’ attention and reactions to road safety messages on

DMSs. Most drivers (89%) indicated that they look at displayed messages, and 85% reported that

they think about the displayed messages. These results reveal that a DMS is an effective

communication device and that displaying non-traffic-related information does not negatively

impact the effectiveness of traffic-related information. Since most respondents appreciated the

display of road safety messages but were not overly enthusiastic about anti-speeding messages,

displaying other safety messages may be more effective than displaying anti-speeding messages.

25

Table 4.7: Driver Responses to Displayed DMS Messages (Online Survey)

Driver Responses to DMS

SD

(%)

D

(%)

N

(%)

A

(%)

SA

(%)

Mean

(1–5)

It is a good idea to remind drivers….

not to follow too closely on the road.

1.67

1.67

25.83

50.00

20.83

3.87

to be courteous on the road.

1.67

7.50

25.00

50.83

15.00

3.70

of hazardous weather conditions.

0.00

0.00

3.33

28.33

68.33

4.65

It is a good idea to display….

general safety messages on highway message

boards.

1.67 5.83 23.33 43.33 25.83 3.86

anti-speeding messages on highway message

boards.

2.50 10.00 39.17 33.33 15.00 3.48

drunk-driving messages on highway message

boards.

5.00 5.00 16.67 50.00 23.33 3.82

anti-texting and driving messages on highway

message boards.

0.83 4.17 14.17 42.50 38.33 4.13

seat belt-use messages on highway message

boards.

0.83 3.33 20.83 45.83 29.17 3.99

weather-warning messages.

1.67

4.17

5.00

40.00

49.17

4.31

Note: Mean calculated using strongly disagree (SD) = 1, disagree (D) = 2, neutral (N) = 3, agree (A) = 4, and

strongly agree (SA) = 5

Table 4.8: Driver Reactions to Displayed Messages

Respond to the Following Statements:

SD

(%)

D

(%)

N

(%)

A

(%)

SA

(%)

Mean

(1–5)

I look at the information on highway message

boards when it is displayed.

0.83 2.50 7.50 51.67 37.50 4.23

I think about the information displayed on

highway message boards.

0.83 1.67 12.50 51.67 33.33 4.15

Behavioral Effects of Road Safety Messages

Remind me to check my following distance

4.17

12.50

32.50

41.67

9.17

3.39

Reduce my likelihood of speeding

2.50

14.17

30.83

35.83

16.67

3.50

Remind me not to text while driving

2.50

5.00

19.17

52.50

20.83

3.84

Remind me not to drive after consuming alcohol

6.67

3.33

19.17

41.67

29.17

3.83

Remind me to pay more attention while driving

3.33

2.50

15.83

57.50

20.83

3.90

Remind me to always use the seat belt while

driving

4.17 6.67 11.67 53.33 24.17 3.87

Remind me to move over for law enforcement or

maintenance workers

4.17 4.17 12.50 45.83 33.33 4.00

Note: Mean calculated using strongly disagree (SD) = 1, disagree (D) = 2, neutral (N) = 3, agree (A) = 4, and

strongly agree (SA) = 5

26

4.2.4 Driver Perception of DMS Messages

4.2.4.1 Messages Shown in Simulator (M1–M14)

The 14 DMS messages coded M1–M14 (Table 4.3) were also used in the online survey. To

confirm survey responses, drivers’ opinions on various displayed messages were elicited using a

standard 5-point Likert scale. As shown in Table 4.9 and Figure 4.5, most participants (91.67%)

thought that “Move Over for Law Enforcement and Maintenance Workers” was the most effective

message, followed by “No Text Is Worth A Life” (83.33%) and “Give Space, Don’t Tailgate”

(83.3%).

Table 4.9: Driver Perceptions of DMS Messages M1–M14 (Online Survey)

Messages

NAE

(%)

NSE

(%)

N

(%)

SE

(%)

VE

(%)

Mean

(1–5)

Steering Wheel: Not A Hands-Free Device 0 13.33 29.17 25 32.5 3.77

Pay Attention and Just Drive 3.33 7.5 29.17 35 25 3.71

Give Space, Don’t Tailgate 1.67 2.5 12.5 50 33.33 4.11

Move Over for Law Enforcement and

Maintenance Workers

0 0 8.33 33.33 58.33 4.50

Speeding Kills 2.5 14.17 20.83 33.33 29.17 3.73

Slow Down 3.33 3.33 22.5 35 35.83 3.97

Drive Like Your Life Depends on It 2.5 13.33 29.17 23.33 31.67 3.68

Get Your Head out of Your Apps 4.17 12.5 25 22.5 35.83 3.73

One Text or Call Could Wreck It All 0 13.33 26.67 31.67 28.33 3.75

Even Texting Drivers Hate Texting Drivers

8.33 15.83 23.33 20.83 31.67 3.52

No Text Is Worth A Life 1.67 0.83 14.17 50 33.33 4.12

What’s More Important, Your Text or Your

Life?

5 12.5 20.83 36.67 25 3.64

Don’t Let Texting Blind You

8.33 12.5 38.33 20.83 20 3.32

Texting & Driving—It Can Wait

1.67 12.5 37.5 29.17 19.17 3.52

Note: Mean calculated using not-at-all effective (NAE) = 1, not-so effective (NSE) = 2, neutral (N) = 3,

somewhat effective (SE) = 4, and very effective (VE) = 5

27

Note: VE: very effective, SE: somewhat effective, N: neutral, NSE: not-so effective, NAE: not-at-all effective

Figure 4.5: Driver Perceptions of DMS Messages M1–M14 (Online Survey)

4.2.4.2 Other Messages

The online survey also included questions regarding the effectiveness of 13 messages

coded M15–M27 (Table 4.5). Drivers’ opinions on the various displayed messages were also

elicited using the standard 5-point Likert scale. As shown in Table 4.10 and Figure 4.6, most

participants (84.17%) thought that “Speeding Kills—Arrive Alive” was the most effective

message, followed by “Click It or Ticket” (78.33%) and “You Drink. You Drive. You Lose.”

(75.83%).

Most survey participants recommended displaying suggestions for safer driving behavior

and other road safety messages, including warnings about driver fatigue, drunk driving, tailgating,

and speeding. Most participants also affirmed the effectiveness of displaying non-traffic-related

information.

28

Table 4.10: Driver Perceptions of DMS Messages M15–M27 (Online Survey)

Messages

NAE

(%)

NSE

(%)

N

(%)

SE

(%)

VE

(%)

Mean

(1–5)

Click It or Ticket 5 4.17 12.5 36.67 41.67 4.06

Click It, Don’t Risk It 3.33 12.5 29.17 42.5 12.5 3.48

Buckle Up, Every Trip, Every Time 8.33 14.17 23.33 29.17 25 3.48

Head Up Phone Down 0 2.5 26.67 45.83 25 3.93

A Steering Wheel Is Not A Hands-Free

Device

3.33 15.83 25 35 20.83 3.54

Slow Down, Ride Like Your Life

Depends on It

5.83 7.5 23.33 35.83 27.5 3.72

Speeding Kills—Arrive Alive 0.83 2.5 12.5 50 34.17 4.14

Tomorrow Is the Reward for Safe Driving 7.5 14.17 17.5 41.67 19.17 3.51

Don’t Text and Drive, It Can Wait 5 18.33 20.83 39.17 16.67 3.44

Just Drive 14.17 12.5 26.67 26.67 20 3.26

You Drink. You Drive. You Lose. 0.83 2.5 20.83 42.5 33.33 4.05

Drunk Driving—Don’t Let Cheers Turn

into Tears

5 6.67 25 37.5 25.83 3.72

Drive High Get A DUI 5 5 25.83 37.5 26.67 3.76

Note: Mean calculated using not-at-all effective (NAE) = 1, not-so effective (NSE) = 2, neutral (N) = 3,

somewhat effective (SE) = 4, and very effective (VE) = 5

Note: VE: very effective, SE: somewhat effective, N: neutral, NSE: not-so effective, NAE: not-at-all effective

Figure 4.6: Driver Perceptions of DMS Messages M15–M27 (Online Survey)

29

4.3. Combined Analysis

Based on preliminary analysis, the results obtained from the two DMS display surveys

were very similar even though they were administered to different sample populations. Therefore,

the two samples were combined to report aggregated results. Figure 4.7 displays the combined

results of the two surveys for questions M1–M14. Visual assessment of Figure 4.7 and Figure 4.8

reveals that the participants responded similarly across the two surveys; therefore, the difference

between the two surveys was minimal, and the conclusion was made that the simulator drivers and

online survey participants had comparable perceptions regarding the messages.

Note: VE: very effective, SE: somewhat effective, N: neutral, NSE: not-so effective, NAE: not-at-all effective

Figure 4.7: Driver Perceptions of DMS Messages M1–M14 (Combined Results)

30

Figure 4.8: Driver Perceptions of DMS Messages M15–M27 (Combined Results)

After combining the two survey results (Table 4.11), most survey participants (91.11%)

thought that “Move Over for Law Enforcement and Maintenance Workers” was the most effective

message, followed by “Give Space, Don’t Tailgate” (82.78%), “Speeding Kills—Arrive Alive”

(82.77%), and “No Text Is Worth A Life” (82%).

31

Table 4.11: Driver Perceptions (Combined) of Messages Displayed on DMS in Simulator

Code Messages

NAE

(%)

NSE

(%)

N

(%)

SE

(%)

VE

(%)

Mean

(1–5)

M1

Steering Wheel: Not A Hands-

Free Device

0.56 13.33 28.89 24.44 32.78 3.76

M2

Pay Attention and Just Drive

3.89

7.78

29.44

34.44

24.44

3.68

M3 Give Space, Don’t Tailgate 1.67 3.33 12.22 48.89 33.89 4.10

M4

Move Over for Law Enforcement

and Maintenance Workers

0.56 0.56 7.78 32.78 58.33 4.48

M5 Speeding Kills 1.67 13.89 21.11 33.89 29.44 3.76

M6

Slow Down

3.33

3.33

22.78

35.00

35.56

3.96

M7

Drive Like Your Life Depends on It

1.67

14.44

30.56

23.33

30.00

3.66

M8 Get Your Head out of Your Apps 5.56 12.22 24.44 22.22 35.56 3.70

M9

One Text or Call Could Wreck It

All

0.00 13.33 26.67 31.67 28.33 3.75

M10

Even Texting Drivers Hate Texting

Driver

8.33 16.11 23.89 20.56 31.11 3.50

M11

No Text Is Worth A Life

1.67

1.67

14.44

49.44

32.78

4.10

M12

What’s More Important, Your Text

or Your Life?

5.00 12.78 21.11 36.11 25.00 3.63

M13

Don’t Let Texting Blind You

7.78

13.89

38.33

20.56

19.44

3.30

M14 Texting & Driving—It Can Wait 1.11 14.44 36.11 29.44 18.89 3.51

M15 Click It or Ticket 4.44 4.44 12.78 36.67 41.67 4.07

M16

Click It, Don’t Risk It

4.44

12.22

28.89

42.22

12.22

3.46

M17

Buckle Up, Every Trip, Every

Time

7.78 13.89 23.89 28.89 25.56 3.51

M18

Head Up Phone Down

0.00

3.89

26.11

45.00

25.00

3.91

M19

A Steering Wheel Is Not a Hands-

Free Device

2.78 16.11 25.56 34.44 21.11 3.55

M20

Slow Down, Ride Like Your Life

Depends on It

6.11 7.78 23.89 36.67 25.56 3.68

M21

Speeding Kills—Arrive Alive

1.11

2.78

13.33

49.44

33.33

4.11

M22

Tomorrow Is the Reward for Safe

Driving

7.22 14.44 17.78 41.11 19.44 3.51

M23

Don’t Text and Drive, It Can Wait

4.44

18.33

21.11

38.89

17.22

3.46

M24

Just Drive

15.00

12.22

27.78

26.11

18.89

3.22

M25 You Drink. You Drive. You Lose. 1.11 3.89 20.56 42.22 32.22 4.01

M26

Drunk Driving—Don’t Let Cheers

Turn into Tears

5.00 7.22 24.44 37.22 26.11 3.72

M27 Drive High Get A DUI 5.56 5.00 25.56 38.33 25.56 3.73

Note: Mean calculated using not-at-all effective (NAE) = 1, not-so effective (NSE) = 2, neutral (N) = 3,

somewhat effective (SE) = 4, and very effective (VE) = 5

32

Chapter 5: Driver Behavior Data Analysis

Data collected via the driving simulator were used to identify changes in driver behavior

due to DMS messages. The statistical analysis involved 2-tailed paired t-tests. A 95% confidence

interval was assumed for the t-tests.

5.1 Speeding Messages

Two DMS speeding messages were used in the simulator scenario to assess whether driver

behavior changed after drivers saw and read these messages. Average speeds before the displayed

message and average speeds after the message was displayed were extracted from the simulator.

In addition, to ensure that drivers read the DMS message, the exact point that drivers initially

looked at the DMS was obtained using eye-tracking equipment.

5.1.1 “Slow Down” Message

The average speed for each driver was calculated by averaging the point speed recorded at

a frequency of 60 Hz. The average speed was calculated during two separate events. The “before”

event included driving along the roadway for approximately 1.5 miles upstream of the DMS and

before participants identified and read the DMS message. The “after” event included looking at

and reading the message on the DMS and driving along the roadway for approximately 1.5 miles.

Drivers’ eye gazes were recorded using the eye-tracking device. Figure 5.1 shows the average

speeds per gender for three age groups during the two events when the message “Slow Down”

(M6) was shown in the DMS.

33

Figure 5.1: Average Speeds and Standard Deviations for the “Slow Down” Message

Table 5.1 provides descriptive statistics of average speed measurements for the “Slow

Down” message. A comparison of the means among the 60 participants in the paired t-test resulted

in a p-value of 0.0001 (Table 5.2). The obtained p-value indicated a significant difference between

the means of the two phases of the drive. Therefore, the “Slow Down” DMS message significantly

affected driving speeds.

Table 5.1: Descriptive Statistics for Avg Speed (Slow Down)

Avg Speed Mean N Std. Deviation Std. Error Mean

Before 72.9305 60 5.36635 .69279

After 69.5352 60 5.98157 .77222

Table 5.2: Significance in 2-Tailed T-Test for Avg Speed (Slow Down)

Mean

Speed

Difference

Std.

Dev

Std.

Error

Mean

95% CI of the

Difference

t df p-value

Lower Upper

3.39533 4.29701 0.55474 2.28530 4.50537 6.121 59 0.0001

34

In addition, a paired t-test was conducted to evaluate if the message affected certain age

groups or genders. Based on results shown in Table 5.3, a p-value of 0.0002 and 0.0041 (less than

0.025) was obtained for males and females, respectively, indicating that the speed of both male

and female drivers significantly changed after reading the message.

Table 5.3: T-Test Results for Avg Speed “Slow Down” Message by Gender Group

Gender

Mean

Speed

Difference

Std.

Dev

Std.

Error

Mean

95% CI of the

Difference

t df p-value

Lower Upper

Male 4.47774 4.49217 0.80682 2.83000 6.12548 5.550 30 0.0002

Female 2.23828 3.82128 0.70959 0.78474 3.69181 3.154 28 0.0041

Average speed changes were also evaluated for three age groups (18–25, 26–50, and over

50 years old). As shown in the statistical results in Table 5.4, the DMS message significantly

affected driving speeds of the 18–25 and 26–50 age groups (p-values = 0.0003 and 0.0011,

respectively) but did not impact the older age group (over 50 years old), where the p-value was

greater than 0.025.

Table 5.4: T-Test Results for Avg Speed “Slow Down” Message by Age Group

Age

Group

Mean

Speed

Difference

Std.

Dev

Std.

Error

Mean

95% CI of the

Difference

t df p-value

Lower Upper

18–25 4.48320 5.07487 1.01497 2.38840 6.57800 4.417 24 0.0003

26–50 2.73680 3.75747 0.75149 1.18579 4.28781 3.642 24 0.0011

50+ 2.32200 2.99066 0.94573 0.18261 4.46139 2.455 9 0.0363

5.1.2 “Speeding Kills” Message

Figure 5.2 shows the average speeds before and after study participants read the DMS

message “Speeding Kills” (M5).

35

Figure 5.2: Average Speeds and Standard Deviations for the “Speeding Kills” Message

Table 5.5 lists the descriptive statistics of the average speeds before and after the “Speeding

Kills” message was displayed. A comparison of the means among the 60 participants in the paired

t-test resulted in a p-value of 0.0003 (Table 5.6). The obtained p-value indicated a significant

difference between the means of the two phases of the driving test.

Table 5.5: Descriptive Statistics for Avg Speed (Speeding Kills)

Avg Speed Mean N Std. Deviation Std. Error Mean

Before 71.3872 60 5.25022 0.67780

After 67.4317 60 5.74255 0.74136

Table 5.6: Significance in 2-Tailed T-Test for Avg Speed (Speeding Kills)

Mean

Speed

Difference

Std.

Dev

Std.

Error

Mean

95% CI of the

Difference

t df p-value

Lower Upper

3.24750 3.89572 0.50294 2.24113 4.25387 6.457 59 0.0003

36

Based on the paired t-test, a p-value less than 0.025, shown in Table 5.7, was obtained for

male and female participants, respectively, which indicates a significant difference between the

means.