Bangladesh

MODERATE ADVANCEMENT

1

2015 FINDINGS ON THE WORST FORMS OF CHILD LABOR

In 2015, Bangladesh made a moderate advancement in its efforts

to eliminate the worst forms of child labor. e Government

published the results of the 2013 National Child Labor Survey

and approved the Domestic Workers Protection and Welfare

Policy which will set the minimum age for domestic work at 14

years. e National Child Labor Welfare Council as well as two

Divisional Child Labor Welfare Councils met for the first time

to discuss child labor elimination activities. However, children

in Bangladesh are engaged in the worst forms of child labor,

including in the production of bricks and forced child labor in

the production of dried fish. e legal framework does not protect

children working in informal economic sectors, including small

farms and street work, where child labor is most prevalent. e

law does not specify the activities and number of hours per week

of light work that are permitted for children that are 12 and 13

years of age. e Government lacks the capacity to enforce child

labor laws as the number of labor inspectors is insufficient for the

size of Bangladesh’s workforce and fines are inadequate to deter

child labor law violations.

I.

PREVALENCE AND SECTORAL DISTRIBUTION OF CHILD LABOR

Children in Bangladesh are engaged in the worst forms of child labor, including in the production of bricks and forced child labor

in the production of dried fish.(1-3) e Government published its 2013 National Child Labor Survey during the reporting period.

e survey data show that 1,698,894 children ages 5 to 17 are engaged in legally prohibited child labor, while 1,751,475 children

are engaged in permitted forms of work.(4) Table 1 provides key indicators on children’s work and education in Bangladesh.

Table 1. Statistics on Children’s Work and Education

Children Age Percent

Working (% and population) 5-14 yrs. 4.3 (1,326,411)

Attending School (%) 5-14 yrs. 81.2

Combining Work and School (%) 7-14 yrs. 6.8

Primary Completion Rate (%) 73.5

Source for primary completion rate: Data from 2011, published by UNESCO Institute f

or Statistics, 2015.(5)

Source for all other data: Understanding Children’s Work Project’s analysis of statistics

from Child Labor Survey, 2013.(6) Data on working children, school attendance, and

children combining work and school are not comparable with data published in the

previous version of this report because of dierences between surveys used to collect

the data.

Based on a review of available information, Table 2 provides an overview of children’s work by sector and activity.

Table 2. Overview of Children’s Work by Sector and Activity

Sector/Industry Activity

Agriculture Farming, including harvesting and processing crops,* raising poultry, grazing cattle,* gathering honey,* and

harvesting tea leaves* (4, 7-11)

Fishing* and drying sh (4, 7, 8)

Harvesting and processing shrimp (10, 12, 13)

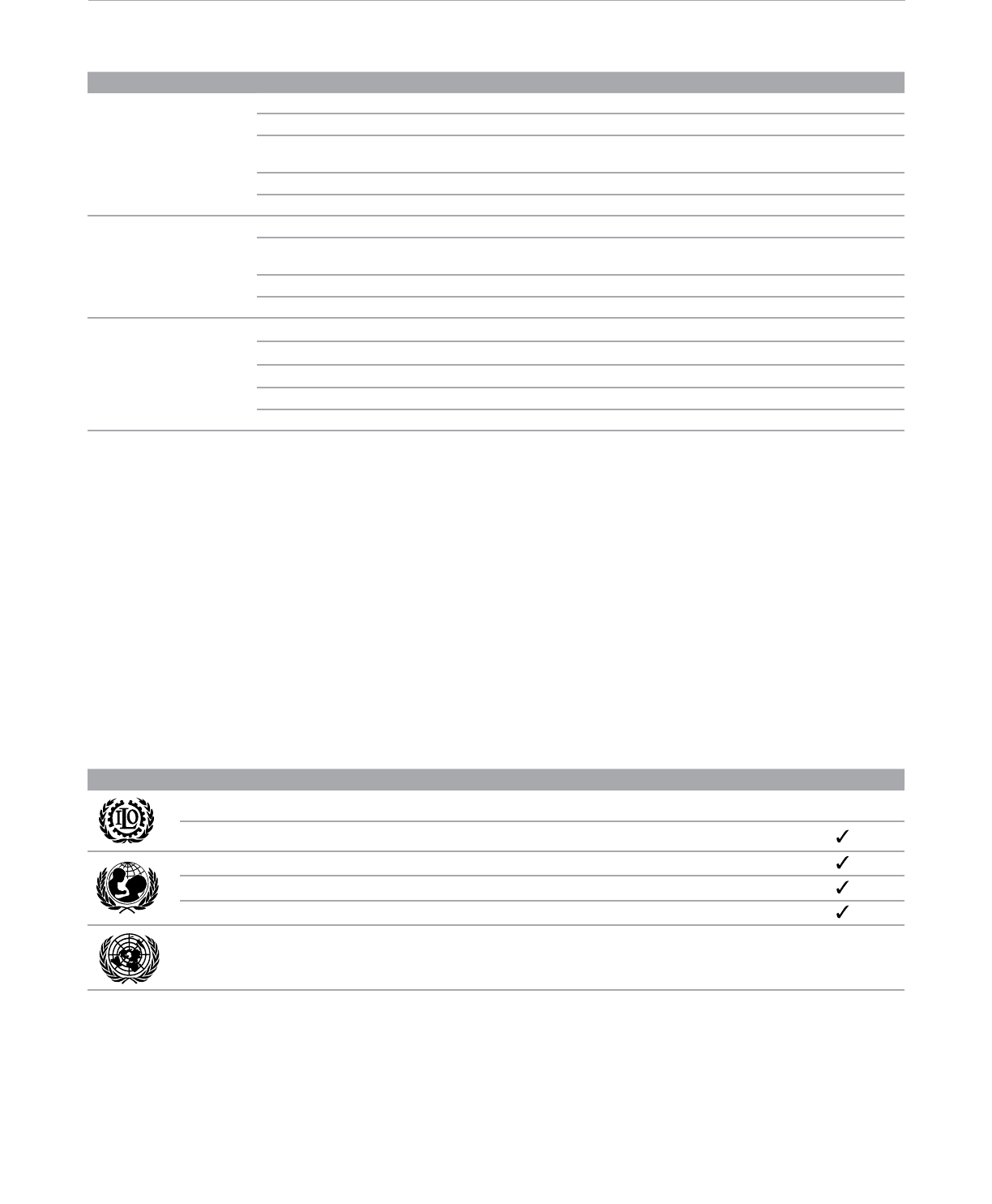

Figure 1. Working Children by Sector, Ages 5-14

Agriculture

39.7%

Services

30.9%

Industry

29.4%

Bangladesh

MODERATE ADVANCEMENT

2

BUREAU OF INTERNATIONAL LABOR AFFAIRS

2015 FINDINGS ON THE WORST FORMS OF CHILD LABOR

Table 2. Overview of Children’s Work by Sector and Activity

Sector/Industry Activity

Industry Quarrying and mining, including salt† (4, 8, 14)

Producing garments, textiles, jute textiles, leather,† footwear,† and imitation jewelry*† (8, 10, 15-19)

Manufacturing bricks,† glass,† hand-rolled cigarettes (bidis),† matches,† soap,† steel furniture,† aluminum

products,*† plastic products,*† and melamine products* (1, 3, 4, 8, 10, 18, 20, 21)

Ship breaking† (10, 22, 23)

Carpentry,* welding,*† and construction*† (4, 7, 10, 24)

Services Domestic work (25-27)

Working in transportation, pulling rickshaws,* and street work, including garbage picking, recycling,*†

vending, begging, and portering (4, 7, 10, 14, 28)

Working in hotels,* restaurants,* bakeries,*† and retail shops* (4, 10, 14, 18, 24)

Repairing automobiles*† (10, 14, 24)

Categorical Worst Forms of

Child Labor‡

Forced labor in the drying of sh and the production of bricks* (2, 11, 29-31)

Forced begging* (31, 32)

Use in illicit activities, including drug dealing* (11)

Commercial sexual exploitation,* sometimes as a result of human tracking* (10, 31, 33, 34)

Forced domestic work (11, 31, 35)

* Evidence of this activity is limited and/or the extent of the problem is unknown.

† Determined by national law or regulation as hazardous and, as such, relevant to Article 3(d) of ILO C. 182.

‡ Child labor understood as the worst forms of child labor per se under Article 3(a)–(c) of ILO C. 182.

Some Bangladeshi children are trafficked internally, and others are trafficked to India and Pakistan for commercial sexual

exploitation.(31) Some children in Bangladesh work under forced labor conditions in the dried fish sector and in the production

of bricks to help pay off family debts to local moneylenders.(29, 31) Children are forced to beg on the streets, including some who

have been kidnapped by gangs.(32)

According to the National Education Policy, education is free and compulsory in Bangladesh through eighth grade, but several

factors contribute to children not completing primary school, such as high student-teacher ratios and short school days of only 2 to

3 hours. e associated costs of education, including books and uniforms, also prevent many children from attending school.(4, 36)

II.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR THE WORST FORMS OF CHILD LABOR

Bangladesh has ratified most key international conventions concerning child labor (Table 3).

Table 3. Ratification of International Conventions on Child Labor

Convention Ratication

ILO C. 138, Minimum Age

ILO C. 182, Worst Forms of Child Labor

UN CRC

UN CRC Optional Protocol on Armed Conict

UN CRC Optional Protocol on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography

Palermo Protocol on Tracking in Persons

e Government has established laws and regulations related to child labor, including its worst forms (Table 4).

(cont)

Bangladesh

MODERATE ADVANCEMENT

3

2015 FINDINGS ON THE WORST FORMS OF CHILD LABOR

Table 4. Laws and Regulations Related to Child Labor

Standard Yes/No Age Related Legislation

Minimum Age for Work Yes 14 Section 34 of the Bangladesh Labor Act (37)

Minimum Age for Hazardous Work Yes 18 Sections 39–42 of the Bangladesh Labor Act (37)

Prohibition of Hazardous Occupations or

Activities for Children

Yes Sections 39–42 of the Bangladesh Labor Act; Statutory Regulatory

Order Number 65 (37, 38)

Prohibition of Forced Labor Yes Sections 370 and 374 of the Penal Code; Sections 3, 6, and 9 of the

Prevention and Suppression of Human Tracking Act (39, 40)

Prohibition of Child Tracking Yes Sections 3 and 6 of the Prevention and Suppression of Human

Tracking Act; Section 6 of the Suppression of Violence Against

Women and Children Act (40, 41)

Prohibition of Commercial Sexual

Exploitation of Children

Yes Sections 372 and 373 of the Penal Code; Sections 78 and 80 of

the Children’s Act; Section 3 of the Prevention and Suppression of

Human Tracking Act; Section 8 of the Pornography Control Act

(39, 40, 42, 43)

Prohibition of Using Children in Illicit

Activities

No Section 79 of the Children’s Act (42)

Minimum Age for Compulsory Military

Service

N/A*

Minimum Age for Voluntary Military

Service

Yes 16, 17 Air Force and Army regulation titles unknown (44, 45)

Compulsory Education Age Yes 11 Section 2 of the Primary Education (Compulsory) Act (46)

Free Public Education Yes Article 17 of the Constitution (47)

* No conscription (48)

e Bangladesh Labor Act excludes the informal economic sectors in which child labor is most prevalent, including domestic work,

street work, and work on small agricultural farms with less than five employees.(37, 43, 49)

Although the labor law stipulates that children over 12 years of age may engage in light work that does not endanger their health

or interfere with their education, the law does not specify the activities or the number of hours per week that light work is

permitted.(37)

e use of children in pornographic performances is not criminally prohibited.(40, 43) e use of children in the production of

drugs is not criminally prohibited.(42)

e 2010 National Education Policy raised the age of compulsory education from grade 5 (age 10) to grade 8 (age 14); however,

until the legal framework is amended to reflect the new compulsory education age, the policy is not enforceable.(50, 51)

III.

ENFORCEMENT OF LAWS ON THE WORST FORMS OF CHILD LABOR

e Government has established institutional mechanisms for the enforcement of laws and regulations on child labor, including its

worst forms (Table 5).

Table 5. Agencies Responsible for Child Labor Law Enforcement

Organization/Agency Role

Department of Inspection for Factories

and Establishments, Ministry of Labor

and Employment

Enforce labor laws, including those relating to child labor and hazardous child labor.(52)

Bangladesh Police Enforce Penal Code provisions protecting children from forced labor and commercial sexual

exploitation.(49, 53)

Bangladesh Labor Court Prosecute labor law cases, including child labor law violations. Impose nes or sanctions against

employers that violate labor laws.(54)

TIP Monitoring Cell of Bangladesh Police Investigate cases of human tracking, forced labor, and commercial sexual exploitation,

including those involving children. Enforce anti-tracking provisions of the Prevention and

Suppression of Human Tracking Act.(55)

Bangladesh

MODERATE ADVANCEMENT

4

BUREAU OF INTERNATIONAL LABOR AFFAIRS

2015 FINDINGS ON THE WORST FORMS OF CHILD LABOR

Table 5. Agencies Responsible for Child Labor Law Enforcement

Organization/Agency Role

Child Protection Networks Respond to a broad spectrum of violations against children, including child labor. Comprises

ocials from various agencies with mandates to protect children, prosecute violations, monitor

interventions, and develop referral mechanisms at the district and subdistrict levels between

law enforcement and social welfare services.(7)

Labor Law Enforcement

In 2015, labor law enforcement agencies in Bangladesh took actions to combat child labor, including its worst forms (Table 6).

Table 6.Labor Law Enforcement Efforts Related to Child Labor

Overview of Labor Law Enforcement 2014 2015

Labor Inspectorate Funding $2.9 million (52) $4.1 million (11)

Number of Labor Inspectors 194 (43) 284 (11)

Inspectorate Authorized to Assess Penalties No (54) No (54)

Training for Labor Inspectors

n

Initial Training for New Employees

n

Training on New Laws Related to Child Labor

n

Refresher Courses Provided

Unknown

N/A

No (43)

Yes (11)

N/A

Yes (11)

Number of Labor Inspections

n

Number Conducted at Worksite

n

Number Conducted by Desk Reviews

25,525 (43)

25,525 (43)

Unknown

31,836 (43)

31,836 (43)

Unknown

Number of Child Labor Violations Found

6 (54) 40 (43)

Number of Child Labor Violations for Which Penalties Were Imposed

n

Number of Penalties Imposed That Were Collected

Unknown (54)

Unknown (54)

Unknown (54)

Unknown (54)

Routine Inspections Conducted

n

Routine Inspections Targeted

Yes (56)

Yes (56)

Yes (11)

Yes (11)

Unannounced Inspections Permitted Yes (56) Yes (11)

Unannounced Inspections Conducted Yes (56) Yes (11)

Complaint Mechanism Exists Yes (52) Yes (52)

Reciprocal Referral Mechanism Exists Between Labor Authorities and Social Services No (52) No (52)

In 2015, the Department of Inspection for Factories and Establishments (DIFE) provided training to labor inspectors on building

and fire safety, occupational safety and health, and labor laws, which included child labor laws.(11)

Although DIFE hired 90 additional labor inspectors during 2015, the number of labor inspectors is still insufficient for the size of

Bangladesh’s workforce.(11) According to the ILO standard of 1 inspector for every 40,000 workers in less developed economies,

Bangladesh should employ about 2,000 inspectors to adequately enforce labor laws throughout the country.(57-59) Reports

indicate that inspections rarely occur at unregistered factories and establishments, places where children are more likely to be

employed.(12, 60)

e penalty of a $62 fine for a child labor law violation is an insufficient deterrent.(7, 56) According to the Ministry of Labor and

Employment, information on penalties imposed and fines collected resides with the labor courts; however, research did not reveal

information about penalties.(54)

Criminal Law Enforcement

In 2015, criminal law enforcement agencies in Bangladesh took actions to combat the worst forms of child labor (Table 7).

(cont)

Bangladesh

MODERATE ADVANCEMENT

5

2015 FINDINGS ON THE WORST FORMS OF CHILD LABOR

Table 7.Criminal Law Enforcement Efforts Related to the Worst Forms of Child Labor

Overview of Criminal Law Enforcement 2014 2015

Training for Investigators

n

Initial Training for New Employees

n

Training on New Laws Related to the Worst Forms of Child Labor

n

Refresher Courses Provided

Unknown

N/A

Yes (61)

Unknown

N/A

Yes (62)

Number of Investigations Unknown Unknown

Number of Violations Found Unknown 178 (63)

Number of ProsecutionsInitiated Unknown Unknown

Number of Convictions Unknown Unknown

Reciprocal Referral Mechanism Exists Between Criminal Authorities and Social Services Yes (52, 61, 64) Yes (52)

In 2015, the Ministry of Home Affairs, in coordination with IOM, UNICEF, and UNODC, conducted anti-human-trafficking

training for law enforcement officials.(62)

e TIP Monitoring Cell of the Bangladesh Police

reportedly has insufficient funds and staff to adequately address cases of

child trafficking, forced child labor, and commercial sexual exploitation of children.(61)

e Bangladesh Police report that from February to December 2015 there were 982 cases of human trafficking and 1 conviction for

crimes involving human trafficking. Disaggregated data for investigations and convictions involving child victims are not provided.

(63) e police also report that 110 children were recovered from human trafficking during the same time period.(63)

IV.

COORDINATION OF GOVERNMENT EFFORTS ON THE WORST FORMS OF CHILD LABOR

e Government has established mechanisms to coordinate its efforts to address child labor, including its worst forms (Table 8).

Table 8. Mechanisms to Coordinate Government Efforts on Child Labor

Coordinating Body Role & Description

National Child Labor Welfare

Council

Coordinate eorts undertaken by various government agencies to eliminate child labor and assess

the implementation of the National Child Labor Elimination Policy provide advice. Chaired by the

Ministry of Labor and Employment, comprises ocials representing relevant government ministries,

international organizations, child advocacy groups, and employer and worker organizations.(65) The

Council held its rst meeting in May 2015.(66)

Counter-Tracking National

Coordination Committee, Ministry

of Home Aairs (MHA)

Coordinate government ministries involved in countering international and domestic human

tracking, including child tracking.(55) Integrate the work of government agencies and

international and local NGOs on human tracking through bimonthly coordination meetings. Oversee

district counter-tracking committees, which oversee counter-tracking committees for subdistricts

and for smaller administrative units.(55, 64, 67)

Rescue, Recovery, Repatriation,

and Integration Task Force, MHA

Coordinate Bangladesh and India’s eorts to rescue, recover, repatriate, and reintegrate victims of

human tracking, particularly children. Liaise with various ministries, government departments,

NGOs, and international organizations that assist tracked children.(64, 68)

In 2015, Divisional Child Labor Welfare Councils in Chittagong and Rangpur met for the first time to discuss child labor

elimination activities.(11)

V.

GOVERNMENT POLICIES ON THE WORST FORMS OF CHILD LABOR

e Government of Bangladesh has established policies related to child labor, including its worst forms (Table 9).

Table 9. Policies Related to Child Labor

Policy Description

National Child Labor Elimination

Policy (NCLEP) (2010–2015)

Guides law making and policy making to eliminate the worst forms of child labor through

interventions that will remove children from the worst forms of child labor and provide them with

viable work alternatives.(69, 70)

Child Labor National Plan of Action

(NPA) (2012–2016)

Identies strategies for implementing and mainstreaming the NCLEP, including developing

institutional capacity, increasing access to education and health services, raising social awareness,

strengthening law enforcement, and creating prevention and reintegration programs.(71)

Bangladesh

MODERATE ADVANCEMENT

6

BUREAU OF INTERNATIONAL LABOR AFFAIRS

2015 FINDINGS ON THE WORST FORMS OF CHILD LABOR

Table 9. Policies Related to Child Labor

Policy Description

Sixth Five-Year Plan (2011–2015) Includes the elimination of child labor as a Government priority and identies the NCLEP and its

NPA as the Government’s central strategy to eliminate child labor.(72)

National Plan of Action to Combat

Human Tracking (2015–2017)†

Establishes goals to meet international standards and best practices for anti-human-tracking

initiatives, including prevention of human tracking; protection of survivors and victims of human

tracking; legal justice for survivors and victims of human tracking; development of advocacy

networks; and establishment of an eective monitoring, evaluation, and reporting mechanism.(55)

National Labor Policy Includes provisions on the prohibition of child labor in the informal and formal employment sectors

in urban and rural areas. States that the Government will take necessary actions to ensure that

children do not engage in hazardous labor and aims to create opportunities for children to access

primary education.(73)

National Education Policy* Species the Government’s education policy, including pre-primary, primary, secondary, vocational

and technical, higher, and non-formal education policies. Increases the compulsory age for free

education to grade 8 (age 14).(51)

National Plan of Action for Education

for All (2003–2015)

Includes provisions that target child laborers for non-formal basic education programs.(74)

National Skills Development Policy Outlines a skills development program for legally working-age children as a means of contributing

to a workplace free from child labor.(75)

National Policy for Children Aims to mitigate child labor by implementing steps set out in the NCLEP strategies for eliminating

child labor.(76)

* Child labor elimination and prevention strategies do not appear to have been integrated into this policy.

† Policy was approved during the reporting period.

In 2015, the Government approved the Domestic Workers Protection and Welfare Policy, which will come into effect in 2016.

(11, 77) e policy sets the minimum age for domestic work at 14 years; however, children between ages 12 and 13 can work as

domestic workers with parental permission.(11) e policy, however, is not legally enforceable.(43)

During the year, the Government also approved the Seventh Five-Year Plan, which lays out actions to be taken by the Government

to reduce child labor and eliminate the worst forms of child labor.(78)

In 2014, the Government drafted the National Corporate Social Responsibility Policy for Children that will provide guidance to

businesses in the formal and non-formal sector on how to respect and protect the rights of children.(36, 79)

VI.

SOCIAL PROGRAMS TO ADDRESS CHILD LABOR

In 2015, the Government of Bangladesh funded and participated in programs that include the goal of eliminating or preventing

child labor, including its worst forms (Table 10).

Table 10. Social Programs to Address Child Labor

Program Description

Eradication of

Hazardous Child Labor,

Phase III†

Three-year Government program that targets 50,000 children between ages 10 and 14 for withdrawal from

hazardous labor through non-formal education and skills development training.(69, 80)

Services for Children at

Risk Project†

Ministry of Social Welfare (MSW) 5-year program that provides integrated child protection services to children

engaged in child labor, including its worst forms.(52) The program has provided services to 2,692 children,

including non-formal education, skills development education, and livelihood training.(35)

Urban Social Protection

Initiative to Reach

the Unreachable and

Invisible and Ending

Child Labor

UNICEF, MSW, and the Ministry of Women and Children’s Aairs (MWCA) 5-year project that provides conditional

cash transfers and employment training, outreach and referral services, and social protection services for

500,000 children and 30,000 adolescents.(10, 81)

Reaching Out-of-School

Children II (2012–2017)

$130 million World Bank-funded, 6-year program that provides out-of-school children with non-formal

education, school stipends, free books, and school uniforms. Students attend learning centers called Ananda

Schools until they are ready to join mainstream secondary schools.(82) As of June 2015, the program has

provided education to 546,000 poor children in 20,162 learning centers.(83)

(cont)

Bangladesh

MODERATE ADVANCEMENT

7

2015 FINDINGS ON THE WORST FORMS OF CHILD LABOR

Table 10. Social Programs to Address Child Labor

Program Description

Child Sensitive Social

Protection Project

(2012–2016)

UNICEF-funded MSW program to reduce abuse, violence, and exploitation of children and youth by improving

access to social protection services.(52) Provides conditional cash transfers of $26 each month for 18 months

for underprivileged children to prevent them from working in child labor.(35) Services also include a stipend

program for out-of-school adolescents.(84)

Enabling Environment

for Child Rights

MWCA program, supported by UNICEF, that rehabilitates street children engaged in risky work. Supports 16,000

children in 20 districts through cash transfers.(36, 85) In 2015, the project launched a pilot initiative to provide

500 additional children in the Dhaka slums with assistance through mobile phone cash transfer.(85)

Primary Education

Stipend Project,

PhaseIII†

Ministry of Primary and Mass Education-implemented program that provides stipends to the children of poor

families throughout Bangladesh in an eort to reduce child labor and mitigate the cost of education.(11)

Support Urban Slum

Children to Access

Inclusive Non-Formal

Education

EU-funded program implemented by Save the Children to provide non-formal education to children in the

urban slums of Dhaka and Chittagong and to mainstream students into the formal education system.(11)

Country Level

Engagement and

Assistance to Reduce

(CLEAR) Child Labor

Project

USDOL-funded, capacity-building project implemented by the ILO in at least 10 countries to build local and

national capacity of the Government to address child labor. Aims to improve legislation addressing child labor

issues, including by bringing local or national laws into compliance with international standards; improve

monitoring and enforcement of laws and policies related to child labor; develop, validate, adopt, and implement

a National Action Plan on the elimination of child labor; and enhance the implementation of national and local

policies and programs aimed at the reduction and prevention of child labor in Bangladesh.(66)

Expanding the Evidence

Base and Reinforcing

Policy Research

for Scaling-up and

Accelerating Action

Against Child Labor

USDOL-funded research project implemented by the ILO in 7 countries, including Bangladesh, to accelerate

country level actions to address child labor by collecting new data, analyzing existing data, building capacity

of governments to conduct research in this area, and supporting governments, social partners and other

stakeholders to identify areas of policy intervention against child labor.(86) The Government’s Bangladesh

Bureau of Statistics, in consultation with the ILO, drafted and published the National Child Labor Survey.(86)

Shelter Project† MSW-administered support services for vulnerable people who have experienced violence, including human

tracking. Includes nine multipurpose shelters and eight crisis centers that provide services to women and

children.(31, 52)

Child Help Line 1098 MSW-implemented and UNICEF-supported 24-hour emergency telephone line. Connects children at risk to

social protection services.(87)

National Helpline

Center†

National Helpline Center for Violence Against Women and Children-operated 24/7, toll-free hotline. Provides

support and guidance to children involved in violent and hazardous situations.(52)

Vulnerable Group

Development Program†

MWCA program that provides vulnerable families with food assistance and training in alternative income-

generating opportunities.(70, 88, 89)

† Program is funded by the Government of Bangladesh.

VII.

SUGGESTED GOVERNMENT ACTIONS TO ELIMINATE THE WORST FORMS OF CHILD LABOR

Based on the reporting above, suggested actions are identified that would advance the elimination of child labor, including its worst

forms, in Bangladesh (Table 11).

Table 11. Suggested Government Actions to Eliminate Child Labor, Including its Worst Forms

Area Suggested Action Year(s) Suggested

Legal Framework Ratify the Palermo Protocol on Tracking in Persons. 2013 – 2015

Ensure that the law’s minimum age protections apply to children working in the informal

sector, including in domestic work, on the streets, and in small-scale agriculture.

2009 – 2014

Ensure that the law species the activities and the number of hours per week that children

between ages 12 and 13 are permitted to perform light work.

2015

Ensure that the law criminally prohibits the use of children in illicit activities, particularly in

the production of drugs.

2015

Legal Framework Ensure that the law criminally prohibits all oenses related to the sexual exploitation of

children for pornographic performances.

2015

Ensure that the legal framework reects the policy that education is compulsory through

grade eight and is consistent with the minimum age for work.

2012 – 2015

(cont)

Bangladesh

MODERATE ADVANCEMENT

8

BUREAU OF INTERNATIONAL LABOR AFFAIRS

2015 FINDINGS ON THE WORST FORMS OF CHILD LABOR

Table 11. Suggested Government Actions to Eliminate Child Labor, Including its Worst Forms

Area Suggested Action Year(s) Suggested

Enforcement Ensure eective enforcement of citations and penalties for labor law violations, including

authorizing the inspectorate to assess penalties for child labor law violations.

2014 – 2015

Publish information on the number of penalties that were issued for child labor

lawviolations.

2012 – 2015

Create referral mechanisms among relevant agencies to facilitate the provision of legal and

social services to child laborers, including in the worst forms of child labor.

2013 – 2015

Hire a sucient number of labor inspectors for the size of Bangladesh’s workforce. 2009 – 2015

Ensure that labor inspections are conducted at unregistered factories and small businesses

with sucient frequency.

2013 – 2015

Publish information on the enforcement of laws on the worst forms of child labor, including

the number of investigators, the number of investigations, the number of prosecutions, the

number of convictions, and penalties implemented.

2012 – 2015

Provide police with sucient resources to enforce violations involving human tracking,

forced labor, and the commercial sexual exploitation of children.

2014 – 2015

Policies Integrate child labor elimination and prevention strategies into the National

EducationPolicy.

2014 – 2015

Social Programs Implement programs that seek to address the prohibitive fees associated with education. 2013 – 2015

REFERENCES

1. Gayle, D. “Inside the Perilous Brick-Making Factories in Bangladesh: Millions

of Workers Face Harsh Conditions as ey Toil to Keep Pace with the Country’s

Breakneck Construction Boom.” e Daily Mail, London, August 17, 2013.

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2396250/Bangladesh-brick-factories--

Millions-workers-face-harsh-conditions.html.

2. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Working Children in Dry Fish Industry in

Bangladesh. Dhaka; December 2011.

3. Bangladesh Institute of Labour Studies. Health Hazards of Child Labour in Brick

Kilns of Bangladesh; 2014.

4. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Child Labor Survey Bangladesh 2013.

Dhaka, Government of Bangladesh; October 2015. http://www.bbs.gov.bd/

WebTestApplication/userfiles/Image/LatestReports/ChildLabourSurvey2013.pdf.

5. UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Gross intake ratio to the last grade of primary.

Total. [accessed December 16, 2015]; http://data.uis.unesco.org/. Data provided

is the gross intake ratio to the last grade of primary school. is measure is a proxy

measure for primary completion. is ratio is the total number of new entrants in

the last grade of primary education, regardless of age, expressed as a percentage of

the population at the theoretical entrance age to the last grade of primary. A high

ratio indicates a high degree of current primary education completion. Because

the calculation includes all new entrants to last grade (regardless of age), the ratio

can exceed 100 percent, due to over-aged and under-aged children who enter

primary school late/early and/or repeat grades. For more information, please see

the “Children’s Work and Education Statistics: Sources and Definitions” section of

this report.

6. UCW. Analysis of Child Economic Activity and School Attendance Statistics from

National Household or Child Labor Surveys. Original data from LFS Survey, 2005-

06. Analysis received December 18, 2015. Reliable statistical data on the worst

forms of child labor are especially difficult to collect given the often hidden or

illegal nature of the worst forms. As a result, statistics on children’s work in general

are reported in this chart, which may or may not include the worst forms of child

labor. For more information on sources used, the definition of working children

and other indicators used in this report, please see the “Children’s Work and

Education Statistics: Sources and Definitions” section of this report.

7. U.S. Department of State. “Bangladesh,” in Country Reports on Human Rights

Practices- 2014. Washington, DC; June 25, 2015; http://www.state.gov/

documents/organization/236846.pdf.

8. U.S. Embassy- Dhaka. reporting, January 23, 2014.

9. UNICEF. Assessment of the Situation of Children and Women in the Tea Gardens of

Bangladesh. New York; 2011.

10. U.S. Embassy- Dhaka. reporting, February 13, 2013.

11. U.S. Embassy- Dhaka. reporting, February 23, 2016.

12. Environmental Justice Foundation. Impossibly Cheap: Abuse and Injustice in

Bangladesh’s Shrimp Industry. London; 2014. http://ejfoundation.org/sites/default/

files/public/Impossibly_Cheap_Web.pdf.

13. Solidarity Center. e Plight of Shrimp-Processing Workers of Southwestern

Bangladesh; 2012. http://www.solidaritycenter.org/Files/pubs_bangladesh_

shrimpreport2012.pdf.

14. International Trade Union Confederation. Internationally Recognized Core Labour

Standards in Bangladesh. Geneva; September 24 and 26, 2012. http://www.ituc-

csi.org/IMG/pdf/bangladesh-final.pdf.

15. Hunter, I. “Crammed into squalid factories to produce clothes.” dailymail.com

[online] November 30 2015 [cited December 4, 2015]; http://www.dailymail.

co.uk/news/article-3339578/Crammed-squalid-factories-produce-clothes-West-

just-20p-day-children-forced-work-horrific-unregulated-workshops-Bangladesh.

html.

16. Human Rights Watch. Toxic Tanneries: e Health Repercussions of Bangladesh’s

Hazaribagh Leather. New York; October 2012. http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/

files/reports/bangladesh1012webwcover.pdf.

17. UCANEWS. “e Extremely Unhealthy Life of the Bangladesh Tannery Worker.”

ucanews.com [online] March 5, 2014 [cited March 7, 2014]; http://www.

ucanews.com/news/the-extremely-unhealthy-life-of-the-bangladesh-tannery-

worker/70421.

18. U.S. Embassy- Dhaka. reporting, December 10, 2015.

19. Sarah Labowitz, and Dorothee Baumann-Pauly. Beyond the Tip of the Iceberg:

Bangladesh’s Forgotten Apparel Workers. New York, NYU Stern Center for

Business and Human Rights; December 2015. https://www.dropbox.com/

sh/1dgl5tfeouvk0va/AADXiOywX4qW3AXpVEkbLhJWa?dl=0.

20. “Child Labour in Bidi Factories.” e Financial Express, Dhaka, 2012. http://

www.thefinancialexpress-bd.com/old/index.php?ref=MjBfMTJfMTRfMTJfMV8

5MV8xNTMxMTg%3D.

21. Anupom Roy, Debra Efroymson, Lori Jones, Saifuddin Ahmed, Islam Arafat,

Rashmi Sarker, et al. “Gainfully Employed? An Inquiry into Bidi-dependent

Livelihoods in Bangladesh.” Tobacco Control, no. 21:313-317 (2012); http://

tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/21/3/313.full.pdf+html.

22. Alam, S. “Unsafe Ship Breaking: Sitakunda Yard, a Ticking Time-Bomb.”

e Financial Express, Dhaka, February 5, 2011; Saturday Feature. http://

recyclingships.blogspot.com/2011/02/unsafe-ship-breaking-sitakunda-yard.html.

23. Federation for Human Rights. “Bangladesh Shipbreaking Still Dirty and

Dangerous with at Least 20 Deaths in 2013.” fidh.org [online] December 13,

2013 [cited March 7, 2014]; http://www.fidh.org/en/asia/bangladesh/14395-

bangladesh-shipbreaking-still-dirty-and-dangerous-with-at-least-20-deaths.

(cont)

Bangladesh

MODERATE ADVANCEMENT

9

2015 FINDINGS ON THE WORST FORMS OF CHILD LABOR

24. Hossain, MA. “Socio-Economic Problems of Child Labor in Rajshahi City

Corporation of Bangladesh: A Reality and Challenges.” Research on Humanities

and Social Sciences, 2(no. 4):55-65 (2012); http://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.

php/RHSS/article/download/1796/1749.

25. Md. Shuburna Chodhuary, Akramul Islam, and Jesmin Akter. Exploring the

Causes and Process of Becoming Child Domestic Worker Dhaka, BRAC; January

2013. Report No. Working Paper No. 35. http://research.brac.net/workingpapers/

Working_Paper_35.pdf.

26. Emadul Islam, Kahled Mahmud, and Naziza Rahman. “Situation of Child

Domestic Workers in Bangladesh.” Global Journal of Management and Business

Research, 13(no. 7)(2013); https://globaljournals.org/GJMBR_Volume13/4-

Situation-of-Child-Domestic-Workers-in-Bangladesh.pdf.

27. ILO Committee of Experts. Individual Observation concerning Worst Forms

of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182) Bangladesh (ratification:2000)

Published: 2010; accessed December 3, 2013; http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/

en/f?p=1000:11003:0::NO:::.

28. Khan, TZ. “Battery recycling ruining children’s lives.” Dhaka Tribune, Dhaka,

January 18, 2014. http://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/2014/jan/18/

battery-recycling-ruining-childrens-lives.

29. Jensen, KB. “Child Slavery and the Fish Processing Industry in Bangladesh.” Focus

on Georgraphy, 56(no. 2)(2013);

30. Manik, M. “Child Labour at Brick Crushing Factory in Bangladesh.” January

7, 2014. http://www.demotix.com/news/3625453/child-labour-brick-crushing-

factory-bangladesh/all-media.

31. U.S. Department of State. “Bangladesh,” in Trafficking in Persons Report-

2015. Washington, DC; July 27, 2015; http://www.state.gov/documents/

organization/243558.pdf.

32. Saad Hammadi, and Jason Burke. “Bangladesh Arrest Uncovers Evidence of Child

Forced into Begging.” e Guardian, London, January 9, January 9, 2011; World.

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/jan/09/bangladesh-arrest-forced-

begging.

33. Integrated Regional Information Networks. “More Data Needed on Abandoned

Children, Trafficking.” IRINnews.org [online] September 6, 2012 [cited

December 13, 2013]; www.irinnews.org/printreport.aspx?reportid=96250.

34. Sharfuddin Khan, and Md Azad. Snatched Childhood: A Study Report on the

Situation of Child Prostitutes in Bangladesh. Dhaka, Bangladesh Shishu Adhikar

Forum; February 2013. http://bsafchild.net/pdf/CP.pdf.

35. ILO Committee of Experts. Individual Observation concerning Worst Forms of

Labour Convention, adopted 2014 (No. 182) Bangladesh (ratification: 2001)

Published: 2015; accessed November 5, 2015; http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/

en/f?p=1000:13100:0::NO:13100:P13100_COMMENT_ID:3184768.

36. U.S. Embassy- Dhaka official. E-mail communication to USDOL official. April

13, 2015.

37. Government of Bangladesh. Labour Law Statutory Regulatory Order Number 65,

enacted June 2, 2006.

38. Ministry of Labor and Employment-Child Labor Unit, Government of

Bangladesh. List of Worst Forms of Works for Children. Dhaka; 2013.

39. Government of Bangladesh. Penal Code, Act No. XLV, enacted 1860.

40. Government of Bangladesh. e Prevention and Suppression of Human Trafficking

Act, enacted 2012.

41. Government of Bangladesh. e Suppression of Violence Against Women and

Children, enacted 2000.

42. Government of Bangladesh. Children’s Act, No. 24, enacted June 20, 2013.

43. U.S. Embassy- Dhaka official. E-mail communication to USDOL official.

February 25, 2016.

44. Bangladesh Army. Join Bangladesh Army, Army Headquarters, AG’s Branch,

Personnel Administration Directorate, [online] [cited November 4, 2014]; http://

www.joinbangladesharmy.mil.bd/career-jobs.

45. Bangladesh Air Force. How to Apply: BAF Airman, Bangladesh Air Force, [online]

[cited November 11, 2014]; http://www.baf.mil.bd/recruitment/howtoairman.

html.

46. Government of Bangladesh. Primary Education (Compulsory) Act, 1990, enacted

1990.

47. Government of Bangladesh. Constitution, enacted March 26, 1971.

48. Government Bangladesh. e Army Act, 1952, enacted 1952. http://bdlaws.

minlaw.gov.bd/print_sections_all.php?id=248.

49. Save the Children. A Study on Child Rights Governance in Bangladesh Dhaka;

2012. http://www.scribd.com/doc/118626953/A-Study-on-Child-Rights-

Governance-Situation-in-Bangladesh.

50. U.S. Embassy- Dhaka official. E-mail communication to USDOL official.

February 13, 2013.

51. Government of Bangladesh. National Education Policy. Dhaka; 2010.

52. Government of Bangladesh. U.S. Department of Labor Request for Information on

Child Labor and Forced Labor. Washington, DC; April 30, 2015.

53. U.S. Embassy- Dhaka official. E-mail communication to USDOL official. March

23, 2014.

54. Department of Inspection for Factories and Establishments, Government

of Bangladesh. Response to Questions from U.S. Government; February 24,

2015

55. Ministry of Home Affairs. National Plan of Action for Combating Human

Trafficking 2015-2017. Dhaka, Government of Bangladesh,; January 2015.

[source on file].

56. USAID. Bangladesh Labor Assessment; April 2014. [source on file].

57. Central Intelligence Agency. e World Factbook, CIA, [online] [cited March 25,

2016]; https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2095.

html#131. Data provided is the most recent estimate of the country’s total labor

force. is number is used to calculate a “sufficient number” of labor inspectors

based on the country’s level of development as determined by the UN.

58. ILO. Strategies and Practice for Labour Inspection. Geneva, Committee on

Employment and Social Policy; November 2006. http://www.ilo.org/public/

english/standards/relm/gb/docs/gb297/pdf/esp-3.pdf. Article 10 of ILO

Convention No. 81 calls for a “sufficient number” of inspectors to do the work

required. As each country assigns different priorities of enforcement to its

inspectors, there is no official definition for a “sufficient” number of inspectors.

Amongst the factors that need to be taken into account are the number and

size of establishments and the total size of the workforce. No single measure

is sufficient but in many countries the available data sources are weak. e

number of inspectors per worker is currently the only internationally comparable

indicator available. In its policy and technical advisory services, the ILO has

taken as reasonable benchmarks that the number of labor inspectors in relation to

workers should approach: 1/10,000 in industrial market economies; 1/15,000 in

industrializing economies; 1/20,000 in transition economies; and 1/40,000 in less

developed countries.

59. UN. World Economic Situation and Prospects 2012 Statistical Annex. New

York; 2012. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/wesp/wesp_

current/2012country_class.pdf. For analytical purposes, the Development Policy

and Analysis Division (DPAD) of the Department of Economic and Social

Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat (UN/DESA) classifies all countries of

the world into one of three broad categories: developed economies, economies

in transition, and developing countries. e composition of these groupings

is intended to reflect basic economic country conditions. Several countries (in

particular the economies in transition) have characteristics that could place them

in more than one category; however, for purposes of analysis, the groupings

have been made mutually exclusive. e list of the least developed countries

is decided upon by the United Nations Economic and Social Council and,

ultimately, by the General Assembly, on the basis of recommendations made by

the Committee for Development Policy. e basic criteria for inclusion require

that certain thresholds be met with regard to per capita GNI, a human assets

index and an economic vulnerability index. For the purposes of the Findings on

the Worst Forms of Child Labor Report, “developed economies” equate to the

ILO’s classification of “industrial market economies; “economies in transition” to

“transition economies,” “developing countries” to “industrializing economies, and

“the least developed countries” equates to “less developed countries.” For countries

that appear on both “developing countries” and “least developed countries” lists,

they will be considered “least developed countries” for the purpose of calculating a

“sufficient number” of labor inspectors.

60. ICF International Inc. Child Labor in the Informal Garment Production in

Bangladesh. Washington, DC; August 2012.

61. U.S. Embassy- Dhaka. reporting, February 17, 2015.

Bangladesh

MODERATE ADVANCEMENT

10

BUREAU OF INTERNATIONAL LABOR AFFAIRS

2015 FINDINGS ON THE WORST FORMS OF CHILD LABOR

62. U.S. Embassy- Dhaka. reporting, February 1, 2016.

63. Bangladesh Police Force, Government of Bangladesh. Monthly Status of Human

Trafficking Cases; accessed February 12, 2016; http://www.police.gov.bd/Human-

Trafficking-Monthly.php?id=324.

64. U.S. Embassy- Dhaka. reporting, March 3, 2014.

65. Ministry of Labor and Employment. Circular: National Child Labor Welfare

Committee. Dhaka, Government of Bangladesh; February 12, 2014.

66. ILO-IPEC. Country Level Engagement and Assistance to Reduce (CLEAR) Child

Labor Project. Technical Progress Report. Geneva; October 2015.

67. U.S. Department of State. “Bangladesh,” in Trafficking in Persons Report- 2013.

Washington, DC; June 19, 2013;

68. Government of Bangladesh. RRRI Task Force Cell, [online] [cited November 7,

2014]; http://antitraffickingcell.gov.bd/.

69. ILO. 2012 Annual Review Under the Follow-up to the ILO 1998 Declaration

Compilation of Baseline Tables. Annual Review. Geneva; 2012. http://www.ilo.

org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_norm/@declaration/documents/publication/

wcms_091263.pdf.

70. Government of Bangladesh. Written Communication. Submitted in response

to U.S. Department of Labor Federal Register Notice (November 26, 2012)

“Request for Information on Efforts by Certain Countries to Eliminate the Worst

Forms of Child Labor”. Washington, DC; January 2013.

71. Government of Bangladesh. National Plan of Action for Implementing the National

Child Labour Elimination Policy (2012-2016). Dhaka; 2013.

72. Government of Bangladesh. Sixth Five Year Plan (FY2011-FY2015). Dhaka; 2011.

73. Ministry of Labor and Employment, Government of Bangladesh. National Labor

Policy. Dhaka; 2012.

74. Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Ministry of Primary

and Mass Education. National Plan of Action for Education for All 2003-2015

Components. Dhaka; 2003. http://www.mopme.gov.bd/index.php?option=com_co

ntent&task=view&id=456&Itemid=475.

75. Ministry of Education. National Skills Development Policy. Dhaka, Government

of Bangladesh,; 2011. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-

bangkok/---ilo-dhaka/documents/publication/wcms_113958.pdf.

76. Ministry of Women and Children’s Affairs, Government of Bangladesh. National

Children Policy. Dhaka; February 2011. http://www.mowca.gov.bd/wp-content/

uploads/National-Child-Policy-2011.pdf.

77. International Domestic Workers Federation. Cabinet Adopts Domestic Workers

Protection and Welfare Policy. Press Release; December 21, 2015. http://idwfed.

org/en/updates/bangladesh-cabinet-clears-draft-policy-to-protect-domestic-

workers-rights.

78. Ministry of Planning. Seventh Five Year Plan (2016-2020). Dhaka, Government

of Bangladesh; October 13, 2015. http://southernvoice-postmdg.org/wp-content/

uploads/2015/10/Bangladesh-Planning-Commission-Seventh-Five-Year-Plan-

FY2016-%E2%80%93-FY2020-Final-Draft-October-2015.pdf.

79. Global Business Coalition for Education. Supporting the Right to Education in

Bangladesh, [online] [cited May 14, 2015]; http://gbc-education.org/supporting-

the-right-to-education-in-bangladesh/.

80. Ministry of Labour and Employment, Government of Bangladesh. Selection of

NGOs for Survey, Non-Formal Education, and Skills Development Training. Dhaka;

2011.

81. UNICEF. Urban Social Protection Initiative to Reach the Unreachable and Invisible

and Ending Child LaborBangladesh Country Office; September 2013. http://www.

unicef.org/bangladesh/Cash_Transfer_web.pdf.

82. World Bank. Second Chance Education for Children in Bangladesh. Press Release;

January 27, 2014. http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2014/01/27/

second-chance-education-for-children-in-bangladesh.

83. World Bank. Reaching Out of School Children II. Technical Progress Report; June

17, 2015. http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/

WDSP/SAR/2015/06/17/090224b082f468fc/1_0/Rendered/PDF/

Bangladesh000B0Report000Sequence005.pdf.

84. Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies, Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics,

UNICEF Bangladesh. Ending Child Labour in Bangladesh. Dhaka; December

2014. http://www.unicef.org/bangladesh/Child_Labour.pdf.

85. UNICEF. Underprivileged Children to Receive Cash Assistance through Mobile. Press

Release. Dhaka; May 6, 2015. http://www.unicef.org/bangladesh/media_9298.

htm.

86. ILO-IPEC. Global SIMPOC. Technical Progress Report. Geneva; November 30,

2105.

87. UNICEF. ‘Child Help Line-1098’ extended to support more vulnerable children.

Press Release. Dhaka; October 12, 2015. http://www.unicef.org/bangladesh/

media_9607.htm.

88. Ministry of Women and Children Affairs, Government of Bangladesh. Medium

Term Expenditure. Dhaka; 2011. www.mof.gov.bd/en/budget/11_12/mtbf/en/30_

Women.pdf.

89. Vulnerable Group Development Program, HEED Bangladesh, [online] August

27, 2011 [cited April 4, 2014]; http://www.heed-bangladesh.com/index.

php?option=com_content&view=article&id=74&Itemid=104.