The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S.

Department of Justice and prepared the following final report:

Document Title: Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending

Misconduct Among New York City Police

Officers

Author(s): James J. Fyfe ; Robert Kane

Document No.: 215795

Date Received: September 2006

Award Number: 96-IJ-CX-0053

This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice.

To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally-

funded grant final report available electronically in addition to

traditional paper copies.

Opinions or points of view expressed are those

of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect

the official position or policies of the U.S.

Department of Justice.

Bad Cops:

A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct

Among

New York City Police Officers

James J. Fyfe

John Jay College of Criminal Justice

and

New York City Police Department

Robert Kane

American University

Final Version

Submitted to the United States Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice

February 2005

This project was supported by Grant No. 1996-IJ-CX-0053 awarded by the National

Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of

views in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the

official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

i

Abstract

This is a study of New York City police officers whose careers ended in

dismissal, termination, or forced resignations or retirements for reasons of misconduct.

The research compares the personal and career histories of all 1,543 officers who were

involuntarily separated from the New York City Police Department (NYPD) for cause

during 1975-96 with a randomly selected sample of their Police Academy classmates

who have served honorably.

The study uses confidential NYPD files as its major data sources. It employs

bivariate techniques to test 37 hypotheses and sub-hypotheses suggested by the literature,

two expert advisory committees, and several focus groups of NYPD personnel. In

addition, the research employed appropriate multivariate techniques (Principal

Component Analysis; Logistic Regression Analysis) which, with some exceptions,

generally supported bivariate findings.

Key findings of the research include:

- Traditional definitions of police misconduct, especially Apolice

corruption,@ are imprecise. In the past, police scholars have classified

acts of police misconduct as Apolice corruption,@ Apolice brutality,@ and

Adrug-related misconduct.@ We found, however, that these classifications

are not mutually exclusive, and that determining whether profit-motivated

criminality by police officers involved job-related police corruption

frequently is impossible.

- Pre-employment history matters. Officers whose life histories include

records of arrest, traffic violations, and failure in other jobs are more

likely than other officers to be involuntarily separated from the NYPD.

- Education and training matter. Officers who hold associate or higher

degrees are less likely than those who do not to be involuntarily separated.

Those who do well in the Police Academy=s recruit training program are

less likely than marginal recruits to be separated as unsatisfactory

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

ii

probationers. Subsequently, they also are less likely to be involuntarily

separated for cause after successful completion of their probationary

periods.

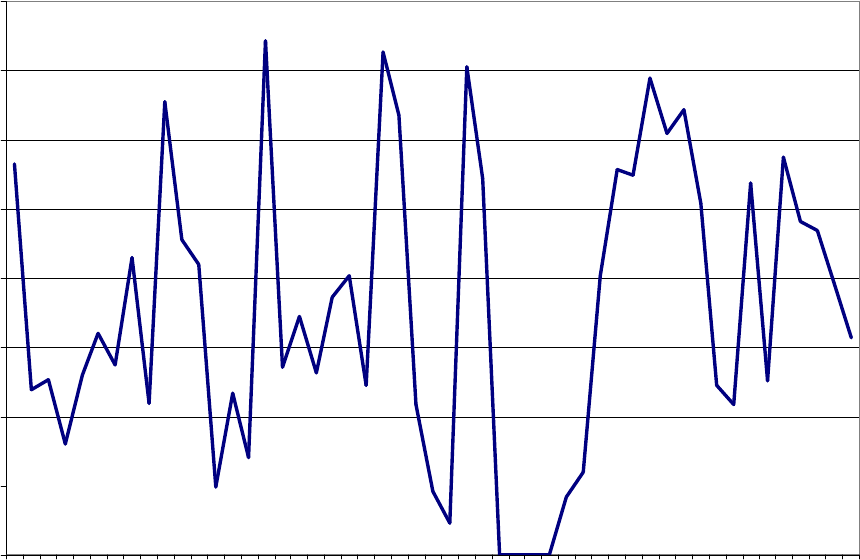

- Diversity matters. As the NYPD has become more diverse, it has become

better behaved. We found a very strong inverse correlation (r=-.71; r

2

.50)

between the percentage of white male NYPD officers and the

department=s annual rate of involuntary separations.

- Race still matters, but apparently only for black officers: As the

representation of Hispanic and Asian officers in the NYPD has increased,

their involuntary separation rates have decreased and become virtually

indistinguishable from those of white officers. Black officers=

representation in the NYPD remained relatively flat during the years

studied. Black officers= involuntary separation rates have also decreased,

but remain higher than those for other racial groups.

The study concludes with recommendations for policy formulation and further

research.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

iii

New York City Police Department Staff

Beverly L Anderson

George Ayala, Jr.

Kettly Barthelemy

Claudia Bellavia

Diane A. Biondo

Betty Braxton-Omaro

Yolanda Caraballo

Karen A. Carter

Jean W. Chen

Patricia A. Clements

Mildred E. Collins

Marilyn N. Coston

Carol A. Ficarella

Patricia Ann Francis

Awilda Fraguada

Barbara Freeman

Robert T. Gasperetti

Dawn L. Gonzales

Clara Hemmingway

Bettie Hickson

Chandra Jairam

Gene R. Johnson

Gerard J. Joyce

Troy Kirschner

Robert F. Larke

Kristine T. Lawless

Terril V. Lesane

Gloria Lynch

John Marsico

Catherine Montaruli

Michelle Moultrie

Gerald L. Neidick

Audrey Phillips

Sharece S. Phillips

Lillian M. Santamaria

Vilma L. Santiago

Todd E. Singleton

Ernest S. Takacs

John Totaro

Dorothy Wallace

Wendy E. Watson

Trita B. Williams

Police Advisory Committee

Walter P. Connery Michael Julian

Attorney at Law Madison Square Garden

Centerport NY Corporation

Henry DeGeneste Jerome H. Skolnick

Prudential-Bache New York University

School of Law

Methodological Advisory Committee

Michael Maxfield Joan McCord

Rutgers University Temple University

School of Criminal Justice Department of Criminal Justice

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

iv

Table of Contents

Page

I. Introduction 1

II. Defining and Identifying Police Misconduct 8

III. Prior Research on Police Misconduct 21

IV. The Research Setting 53

V. The NYPD, 1975-1996 78

VI. Research Methods 97

VII. Research Questions 112

VIII. Hypothesis Testing 127

IX. Multivariate Analysis 272

X. Discussion 288

Sources 295

Cases Cited 309

Appendix I

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

v

List of Tables

Page

VIII-1 Principal Component Analysis of New York City

Crime Rates 142

VIII-2: Initial Hierarchical Poisson Model Estimates of

Within- and Between-Precinct Police Misconduct in

New York City 144

VIII-3 Hierarchical Poisson Estimates of the Influence of

Homicide, per Capita Income, and Percent Minority

Population on Within- Precinct Police Misconduct in

New York City (No Control Variables Included) 147

VIII-4 Hierarchical Poisson Estimates of the Influence of

Index Crime, per Capita Income, and Percent Minority

Population on Within- Precinct Police Misconduct in

New York City (Control Variables Included) 148

IX-1 Comparisons Between Study and Comparison Officers

Along Predictor Variables of Interest 273

IX-2 Principal Component Analysis of Criminal History

Variables 277

IX-3 Principal Component Analysis of Work History

Variables 278

IX-4 Principal Component Analysis of Social Condition

Variables 279

IX-5 Logistic Regression Estimates and Odds Ratios

Predicting Police Misconduct 282

List of Figures

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

vi

Figure Title Page

II-1 NYPD Misconduct Codes 9

IV-1 NYPD Organization Chart 58

IV-2 Characteristics of NYPD Precincts 62

IV-3 Integrity Test Failures, 1999-2001 70

IV-4 EDIT Program Operations, 1999-2001 72

V-1 Police Officer Appointments to the NYPD, 1946-1996 88

V-2 Precinct Officers and Supervisors, 1975-1996 89

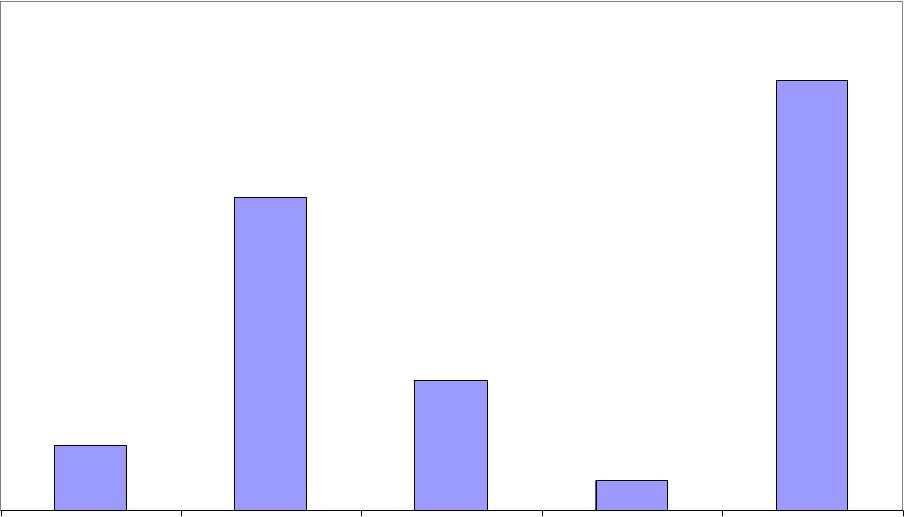

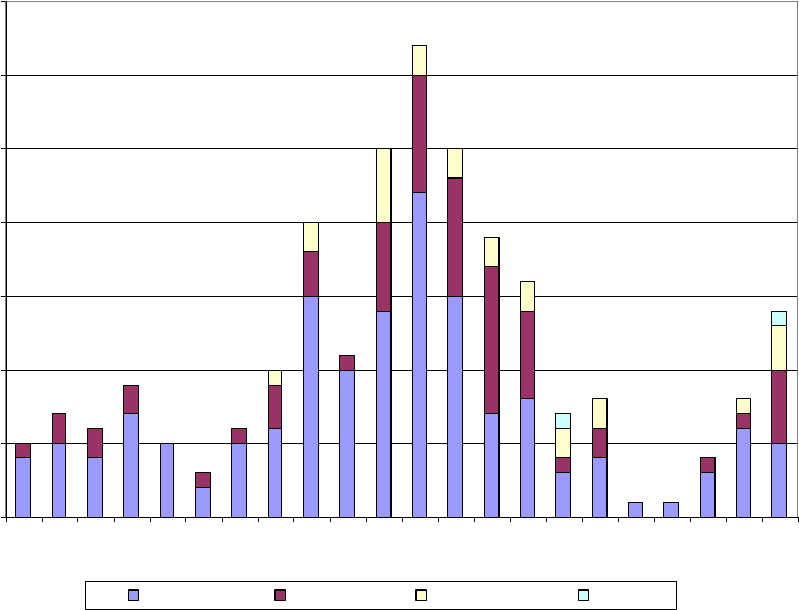

VIII-1 Primary Charges against Study Officers 128

VIII-2 All Specifications against Study Officers 130

VIII-3 Profit-Motivated Charges Against Study Officers 121

VIII-4 On-Duty Abuse Charges Against Study Officers by Year 151

VIII-5 Mean Annual Rate per 1,000 Officers of Separations

for On-Duty Abuse, by Mayor 153

VIII-6 Mean Annual Fatal Shooting Rates per 1,000 Officers

in Ten Largest U.S. Cities, 1990-2000 155

VIII-7 Mean Annual Civil Rights Complaint Rates per 1,000

Officers in Ten Largest U.S. Cities, 1985-1990 157

VIII-8 Officers Hired 1965-1995 and Class Separation Rates

During 1975-1995 162

VIII-9 Years in Service Prior to Separation, Study Officers

Appointed 1979-1996 164

List of Figures (continued)

Figure Title Page

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

vii

VIII-10 1979-95 Classes' Cumulative Percent Involuntary

Separations, Career Years 1-18 166

VIII-11 Annual Class Size (in Thousands) and Cumulative

Involuntary Percent Separations, 1979-1995 Classes 168

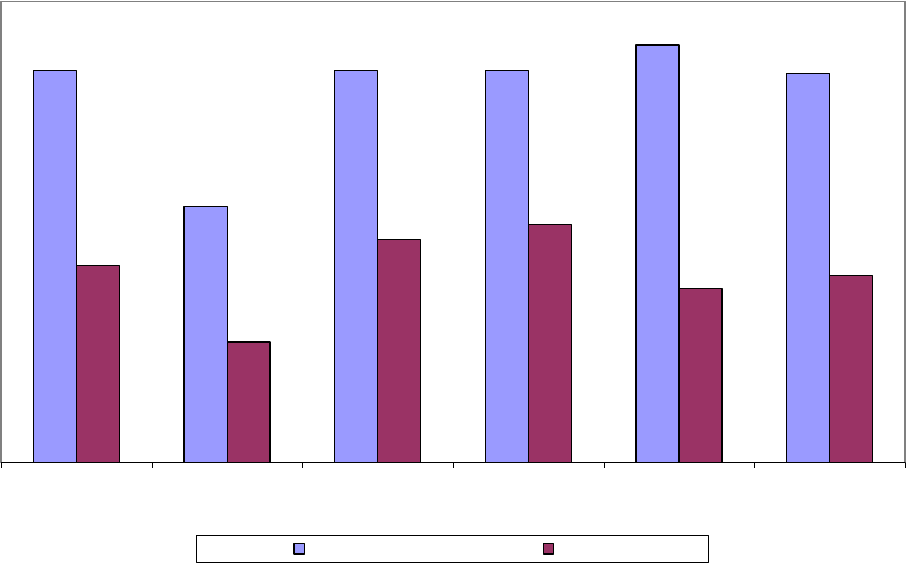

VIII-12 Annual Percentages of Non-White Officers and

Involuntary Separation Rates per 1,000 Officers,

1986-96 170

VIII-13 Anual Involuntary Separation Rates by Race, 1986-96 173

VIII-14 Annual Involuntary Separation Rates by Gender, 1986-96 176

VIII-15 Probationary Termination Rates by Gender, 1987-95 178

VIII-16 Rates of Separation for Profit-Motivated Offenses per

1000 Officers by Gender, 1986-96 180

VIII-17 Ten Most Frequent Primary Charges against Officers

Separated for Profit-Motivated Misconduct, 1975-96 182

VIII-18 Separations for Profit-Motivated Offense by Gender,

1975-96 183

VIII-19 Rates of Separations on Charges Including On-Duty

Abuse per 1,000 Officers by Gender, 1986-96 187

VIII-20 Rate of Separations for Drug Test Failures or Refusals

per 1,000 Officers by Gender, 1986-96 189

VIII-21 Rates of Separation for Off-Duty Violent and Public

Order Offenses per 1,000 Officers by Gender, 1986-96 191

VIII-22 Rates of Separation for Administrative Rule Violations

per 1,000 Officers by Gender, 1986-96 192

VIII-23 Probationary Separation Rates per 100 Probationary

Officers by Race, 1987-95 196

List of Figures (continued)

Figure Title Page

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

viii

VIII-24 Race of Control Officers and Officers Separated for

Profit-Motivated Offenses, 1975-96 198

VIII-25 Separations for Bribery and Profit-Motivated Offenses,

1975-96 201

VIII-26 Rates of Separation for Profit-Motivated Offenses

per 1,000 Officers by Race, 1990-96 202

VIII-27 Percentage of Officers in Supervisory Ranks by

Race, 1990-96 205

VIII-28 Mean Annual Separation Rates for Profit-Motivated

Misconduct by Rank and Race, 1990-96 207

VIII-29 Commands of Officers Separated for Profit-Motivated

Misconduct and Matching Control Officers by Race,

1975-96 208

VIII-30 Separations for On-Duty Abuse by Race, 1975-96 212

VIII-31 Rates of Separation per 1,000 Officers in Which

Primary Charge was On-Duty Abuse,1986-96, by Race 215

VIII-32 Separations for Non-Line of Duty Offenses by Race,

1975-96 216

VIII-33 Separation Rates per 1,000 Officers for Non-Line of

Duty Offenses by Race, 1986-96 217

VIII-34 Separation Rates per 1,000 Officers for Drug Test

Failures or Refusals by Race, 1986-96 219

VIII-35 Separations For Administrative Rules Violations

by Race, 1975-96 221

VIII-36 Separation Rates per 1,000 Officers for Administrative

Rules Violations by Race, 1986-96 223

List of Figures (continued)

Figure Title Page

VIII-37 Mean Annual Separation Rates per 1,000

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

ix

Police Officers/Detectives for Administrative Rules

Violations by Race, 1990-96 225

VIII-38 Commands of Officers Separated for Administrative

Rule-Breaking and Matched Control Officers by Race,

1975-96 227

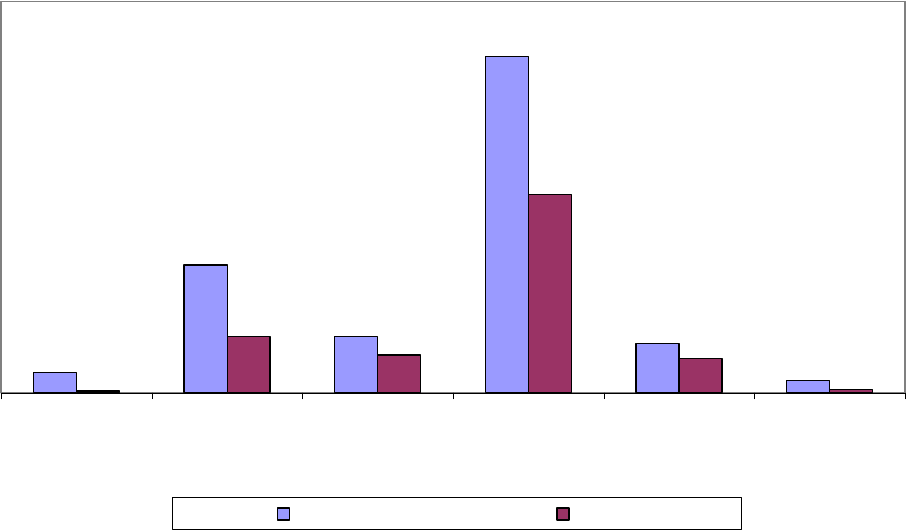

VIII-39 Separation Rate per 10,000 Officers and

Percentage White Male Officers, 1986-96 232

VIII-40 Separated and Control Officers' Age at Appointment,

1975-96 235

VIII-41 Separated and Control Officers' Age at Appointment,

Profit-Motivated Offenses, 1975-96 236

VIII-42 Separated and Control Officers' Age at Appointment,

On-Duty Abuse, 1975-96 237

VIII-43 Separated and Control Officers' Age at Appointment,

Drug Sales, 1975-96 239

VIII-44 Separated and Control Officers' Age at Appointment,

Non-Line of Duty Offenses, 1975-96 240

VIII-45 Separated and Control Officers' Age at Appointment,

Drug Test Failures and Refusals, 1975-96 241

VIII-46 Separated and Control Officers' Age at Appointment,

Administrative Rules Violations, 1975-96 242

VIII-47 Separated and Control Officers' Prior Employment

and Pre-Entry Experiences, 1975-96 244

VIII-48 Separated and Control Officers' Military Experience,

1975-96 245

List of Figures (continued)

Figure Title Page

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

x

VIII-49 Percentage of Study and Control Officers with

Military Experience, by Study Officer SeparationYear 249

VIII-50 Percentage of Study and Control Officers with Military

Experience, by Year Officers Appointed to NYPD 251

VIII-51 Year in Which Study and Control Veterans Entered

the Military 252

VIII-52 Military Experiences of Study and Control Officers 254

VIII-53 Separated and Control Officers' Educational Levels

at Entry to the NYPD 258

VIII-54 Percentage of Study and Control Officers with Five+

Years Service in Supervisory or Command Ranks, by

Educational Level at Entry into NYPD 260

VIII-55 Study and Control Officers' Academic and Physical Scores

in Police Academy (Excludes Separated Probationers) 262

VIII-56 Study and Control Officers' Sick, Late, and Disciplinary

Records in Police Academy (Excludes Separated

Probationers) 264

VIII-57 Frequency of Study and Control Officers' Sick and Late

Reports, and Disciplinary Records in Police Academy

(Excludes Separated Probationers) 265

VIII-58 Study and Control Officers' Mean Scores on Police

Academy Instructional Staff Ratings (Excludes Separated

Probationers) 267

VIII-59 Annual Rates of Complaints against Study and Control

Officers Prior to Study Officers=s Separation 270

X-1 Percent Change in Representation in NYPD Ranks 291

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xi

Appendices

Appendix Title

I Handbook for Data Collection Staff

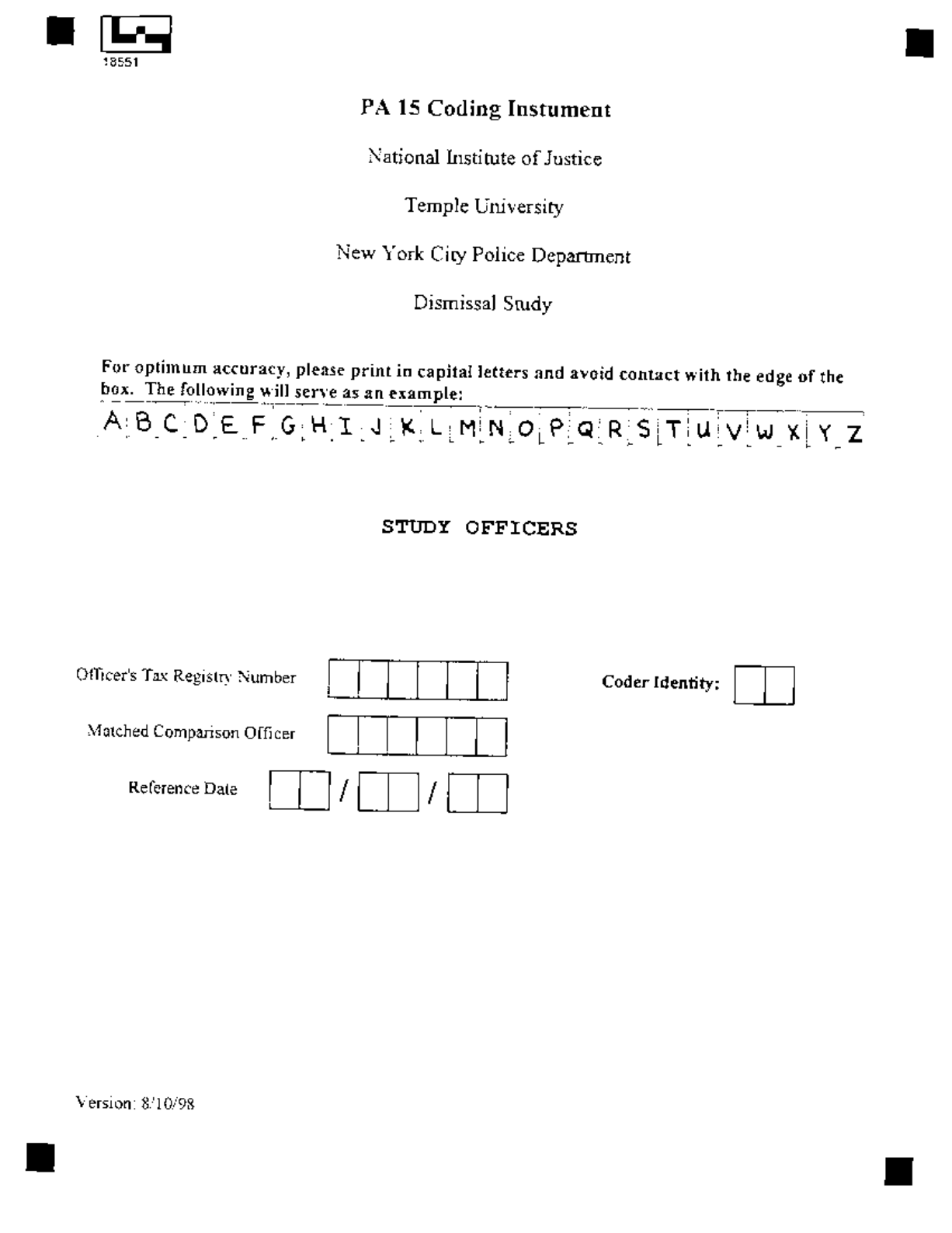

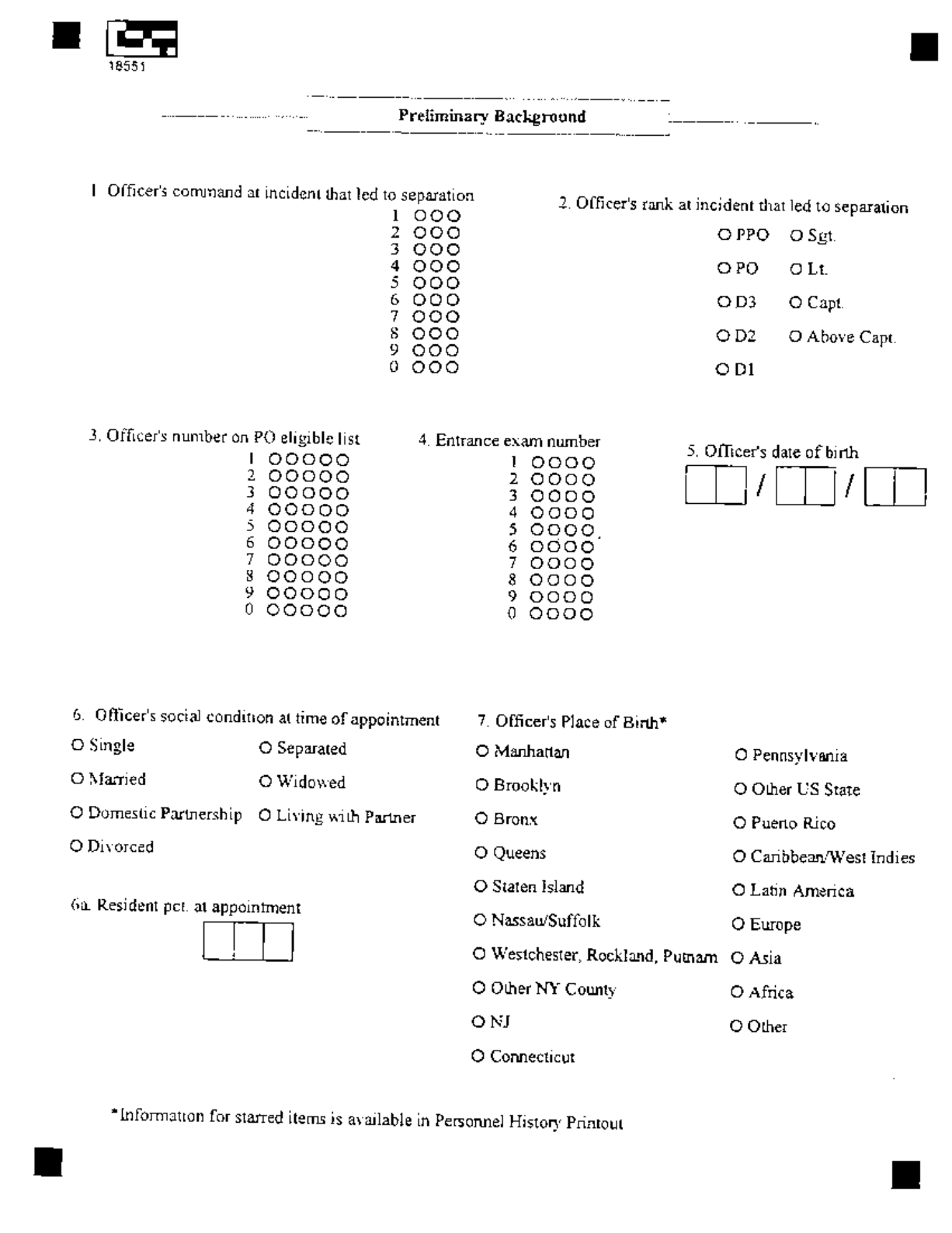

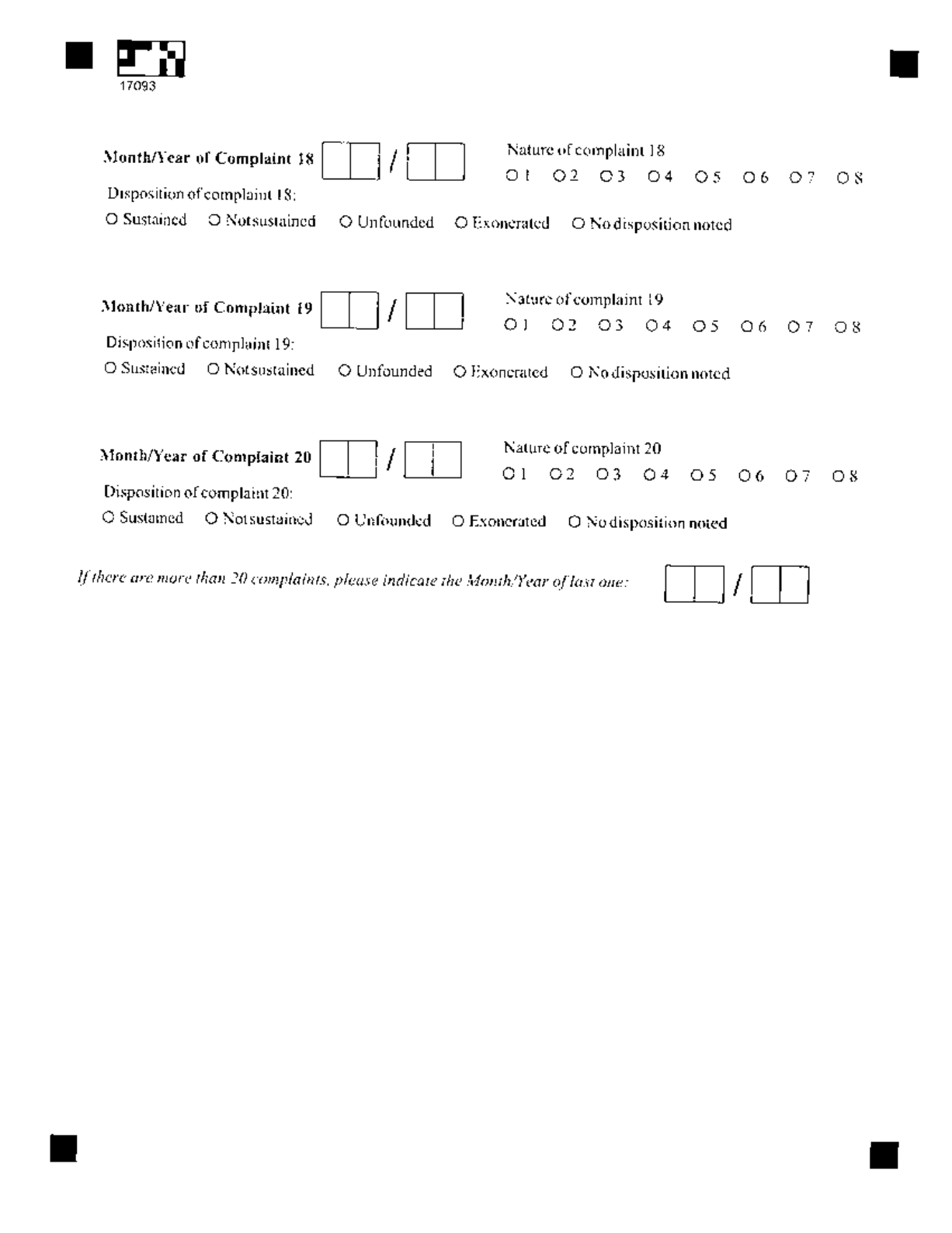

I-A Study Officer Data Collection Instrument

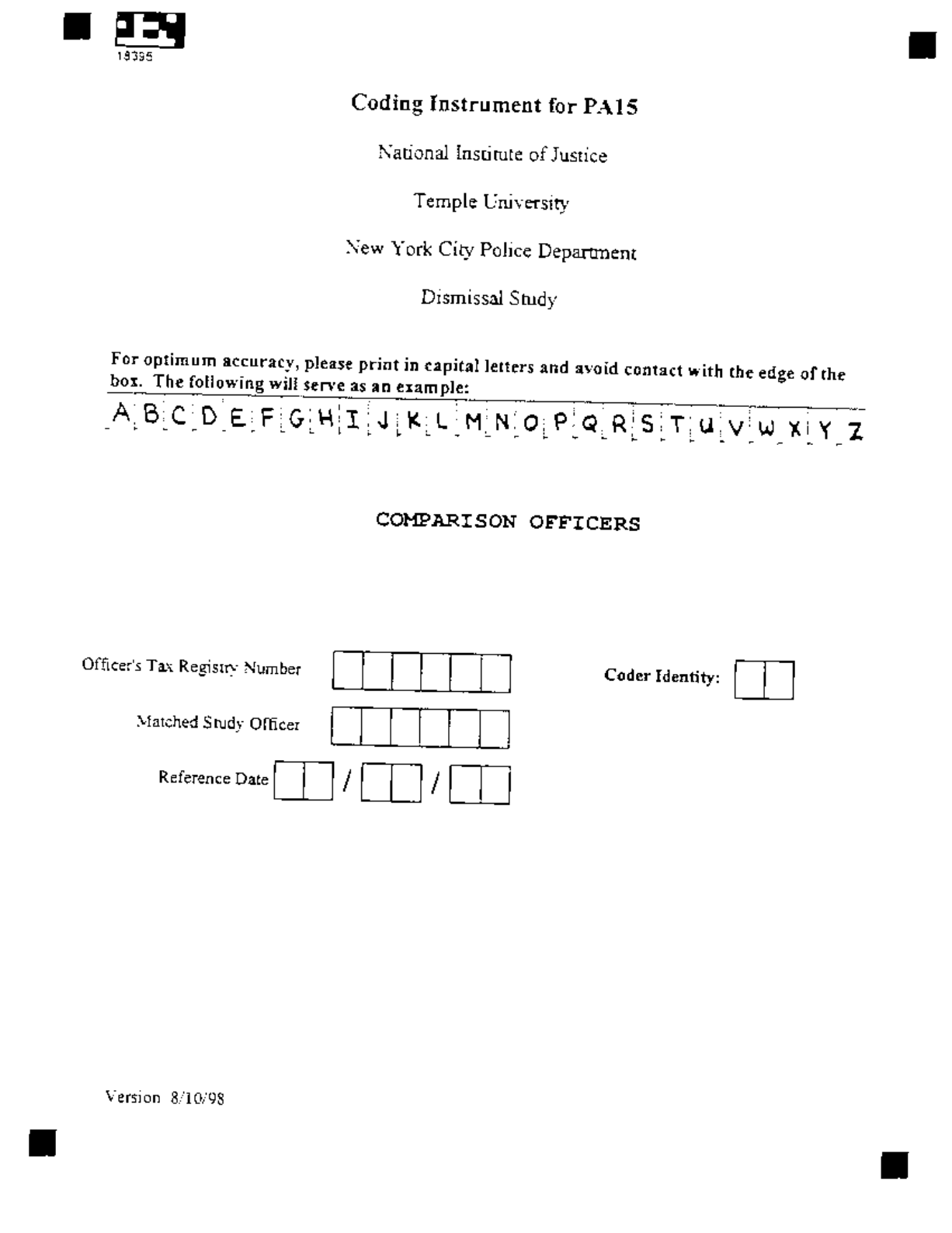

I-B Comparison Officer Data Collection Instrument

I-C Staff Coder Identification Numbers

I-D Command Codes

I-E Military Ranks

I-F Offense Classifications

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This is a study of the differences between New York City police officers whose careers

ended in involuntary separations for cause and their colleagues who have served honorably. The

study addresses many issues and reaches many conclusions. Key findings include:

- Traditional definitions of police misconduct, especially Apolice corruption,@ are

imprecise. In the past, police scholars have classified acts of police misconduct

as Apolice corruption,@ Apolice brutality,@ and Adrug-related misconduct.@ We

found, however, that these classifications are not mutually exclusive, and that

determining whether profit-motivated criminality by police officers involved job-

related police corruption frequently is impossible.

- Involuntary separations are rare. Separations for cause from the New York City

Police Department (through dismissals, terminations, and forced resignations and

retirements) are infrequent events. Only two percent of the officers employed by

the NYPD during the 22 years (1975-96) we studied were involuntarily separated

from the department.

- Pre-employment history matters. Officers whose life histories include records of

arrest, traffic violations, and failure in other jobs are more likely than other

officers to be involuntarily separated from the NYPD.

- Education and training matter. Officers who hold associate or higher degrees are

less likely than those who do not to be involuntarily separated. Those who do

well in the Police Academy=s recruit training program are less likely than

marginal recruits to be separated as unsatisfactory probationers. Subsequently,

they also are less likely to be involuntarily separated for cause after successful

completion of their probationary periods.

- Diversity matters. As the NYPD has become more diverse, it has become better

behaved. We found a very strong inverse correlation (r=-.71; r

2

.50) between the

percentage of white male NYPD officers and the department=s annual rate of

involuntary separations.

- Race still matters, but apparently only for black officers: As the representation

of Hispanic and Asian officers in the NYPD has increased, their involuntary

separation rates have decreased and become virtually indistinguishable from those

of white officers. Black officers= representation in the NYPD remained

relatively flat during the years studied. Black officers= involuntary separation

rates have also decreased, but remain higher than those for other racial groups.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xiii

The study reaches these conclusions after examining the life and career histories of all

1,543 officers who were dismissed or forced to leave the NYPD for reasons of misconduct

during 1975-1996 (excluding, e.g., those who failed their recruit training program) and compares

them to a stratified sample of their Police Academy classmates who were selected randomly on

the basis of their NYPD employee, or tax registry, numbers. During this period, the NYPD

averaged well over 30,000 uniformed officers, and its personnel strength ranged between 21,500

in the late 1970s to 38,000 at the end of the study. In all, the NYPD employed about 78,000

different individuals as police officers during the years we studied. On June 30,1975, the

department employed more than 32,000 officers. Between then and the end of 1996, it hired (or

absorbed from the former Housing and Transit Authority police agencies more than 45,000

additional officers. Thus, our population of 1,543 officers separated for cause represents about

two percent of all officers employed by the NYPD during 1975-96.

The data for our study and control officers consist of information compiled in NYPD

personnel folders and disciplinary records. These include each officer=s original application, the

PA-15, a very detailed life history that is prepared by police officer candidates themselves, and

that is then subjected to extensive pre-employment investigation by the NYPD=s Applicant

Processing Division. As officers= careers proceed, notable events are recorded in their

personnel folder, including their recruit school performance; disciplinary histories; recognition

of outstanding performance and commendatory letters from both NYPD officials and the public;

vehicle accidents; injuries and sickness; changes in their social status, address, and educational

achievement; transfers; promotions; temporary assignments; and supervisors= performance

evaluations. We had access to the Central Personnel Index, an automated data base that

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xiv

supplements the personnel file, and that summarizes noteworthy career events (commendations;

complaints; line of duty injuries; sick leave absences; designation as chronically; vehicle

accidents; internal investigations and their dispositions. We checked the Personnel Orders

Section=s records, which contain the official history of each officer=s assignments and

addresses; and also had access to the Police Academy=s records of officers= performance in

recruit training.

The study was intended to describe the circumstances that led to involuntary separations

from the NYPD and to identify differences between the involuntary separated officers (the

Astudy officers@) and an equal, randomly selected number of officers who had entered the

NYPD in the same Police Academy classes as the study officers (the Acontrol officers@). We

chose this method as the best available way to determine whether characteristics and experiences

of involuntarily separated officers were different from those of their colleagues. To do this, we

generated and tested a lengthy series of hypotheses and conducted multivariate analyses

designed to identify factors that distinguished between the study and control officers.

This process led to a discovery about traditional definitions of police misconduct. We

found that it was impossible to define a typology of police misconduct that included Apolice

corruption@ as a classification that could clearly be distinguished from other categories of

wrongdoing. To be sure, many of the officers we studied were corrupt, but the conduct for

which they were separated from the NYPD included a wide variety of money-making

misconduct that had connections of varying strength to their employment as police officers.

When officers accept bribes to refrain from enforcing the law, they unambiguously engage in

what most of us would regard as police corruption. But it is less clear whether officers who

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xv

perform robberies or burglaries, shoplift, sell drugs, or engage in welfare or insurance fraud

during their off-duty time are engaging in a variety of police corruption. Thus, we created a

category of wrongdoing called profit-motivated misconduct, and recommend that future scholars

and administrators rethink the notion of Apolice corruption.@ Often, in these changing times,

police corruption is not as easy to define as we formerly may have been believed.

Those who have read early drafts of this report have generally expressed surprise at the

small number of officers separated for charges that included brutality and other abusive conduct.

Over 22 years, 119 officers were separated on charges that included some form of on-duty

abuse. Only 37 of these officers B 1.7 per year B were separated in matters in which the primary,

or only charge, against them was on-duty abuse. We believe that there are two explanations for

this. First, despite some spectacular and widely publicized acts of brutality, the NYPD has long

been one of the most restrained police agencies in the country. NYPD officers are less likely

than officers in virtually all big police departments to fire their weapons at citizens, and the data

we reviewed showed that they were less likely than most to be subjects of civil rights complaints

to the U.S. Justice Department.

This, we believe, is because the NYPD historically has held its officers to an extremely

high degree of accountability. Its reviews of police shootings, use of force, and citizens=

complaints are extensive and objective. In the course of our work, we also found that the NYPD

engaged in a wide variety of pro-active strategies designed to deter and detect wrongdoing.

Like many other agencies, the NYPD runs an early warning system, and regularly reviews and

monitors officers who seem to experience their work differently than do their colleagues.

Officers whose histories are marked by repeated complaints, vehicle accidents, line of duty

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xvi

injuries, sick leave, and arrests for such contempt of cop offenses as resisting arrest and

obstructing governmental administration are routinely assigned to close supervision, retraining in

a special and individually tailored program, and monitoring by the department=s administration.

But the NYPD does other things that are not so common. The NYPD=s Internal Affairs

Bureau encourages officers to call anonymously to report apparent wrongdoing by their

colleagues. IAB uses this and other information to conduct hundreds of Integrity Tests B stings

B on personnel who are suspected of wrongdoing. Some of these tests replicate the

circumstances in which it has been alleged that officers have mistreated people by, for example,

presenting a suspect officer with a staged, on-street, opportunity to mistreat a person of color or

member of some protected class; by giving an officer an opportunity to improperly pocket cash.

Integrity tests also are conducted to determine whether ranking officers properly accept and

process complaints about the officers who work for them. On occasion, the tests are very

elaborate, involving lengthy operations designed to arrest criminals (gamblers; drug dealers) who

are believed to be in corrupt relationships with officers for the purpose of turning them in order

to gain evidence to prosecute crooked officers. These proactive investigative steps are unusual B

perhaps even unique to the NYPD B and are worthy of study by both scholars and police

administrators. They should also be taken into account in attempts to generalize our findings to

other settings.

The second reason that the number of separations for brutality is lower than what one

might expect is the difficulty of proving these cases. Unless evidence of excessive force is

unambiguous B as in the taped beating of Rodney King and the injuries sustained by Abner

Louima when police sodomized him with a stick B it is very difficult to show that the force used

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xvii

by a police officer was more than was reasonably necessary to subdue a resisting person. For

this reason, the proactive work of the NYPD B its early warning system and its system of tests

in which suspect officers are presented with opportunities to be abusive B are such an important

part of its work.

We also found that the NYPD=s program of drug testing its officers is more extensive

than most. Every year, on previously unannounced days, a random sample of 20 percent of the

members of every NYPD unit appears at work and is directed to proceed immediately to the

Medical Unit in order to undergo a Dole Test. Test failure or refusal to take such a test results

in immediate suspension and, almost invariably leads to dismissal. This program, combined

with an extensive for cause testing program, in which personnel may be ordered to undergo

testing on the suspicion that they are abusing controlled substances, may result in a higher

percentage of drug-related terminations than is true of most agencies.

We tested most of our hypotheses by comparing the percentage of study officers who

shared a trait or experience with the comparable percentage among the control officers. Our

results on each were as follows:

HYPOTHESIS RESULTS

H1: More involuntary separations are attributable to CONFIRMED

profit-motivated corruption than to brutality and other

non-profit abuses of citizens.

H2: MODIFIED TO: Variations in community structure CONFIRMED

(i.e., per capita income, percentage minority population)

and public crime (homicide, FBI index crimes)

will predict variations in police misconduct within police

precincts over time.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xviii

H3: The rate of involuntarily separations for brutality REJECTED: KOCH

and other non-profit abuse of citizens was greater during ADMINISTRATION

the administration of David Dinkins than during either the HAD HIGHEST

Koch or Giuliani administrations. RATES

H4: Rates of involuntary separation for reasons other REJECTED: KOCH

than brutality and non-profit abuse were greater during ADMINISTRATION

the administration of Rudolph Giuliani than during either HAD HIGHEST

the Koch or Dinkins administrations. RATES

H5: Rates of involuntary separation for corruption, REJECTED

1

brutality, and other forms of misconduct are positively

associated with the size of Police Academy recruit training

cohorts.

H5a: The rate at which new officers are REJECTED

involuntarily separated as unsatisfactory

probationers is inversely correlated with the

size of Police Academy recruit training cohorts.

H6: Rates of involuntary separation for UNTESTABLE:

corruption, brutality, and other forms of misconduct INSUFFICIENT

are inversely associated with the rigor and intensity DATA

of recruit training, as measured by:

H6a: numbers of hours of training; UNTESTABLE

H6b: rates of involuntary separation for UNTESTABLE

academic and physical failure, and for

disciplinary reasons.

H7: Rates of involuntary separation for corruption, CONFIRMED

brutality, and other police misconduct are inversely

associated over time with the percentage of non-white

officers in the department.

H8: Rates of involuntary separation for corruption, UNTESTABLE:

brutality, and other police misconduct are positively INSUFFICIENT

1

Our test of this hypothesis was less rigorous than we would have liked.

Because measurement issues made it impossible to include in the analysis all the study

officers, we limited analysis to officers who were both hired and fired during 1979-1995.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xix

associated over time with the percentage of officers DATA

who reside outside New York City.

H9: Female officers' involuntary separation rate is REJECTED

positively associated over time with the percentage of

females in the department.

H10: The rate of involuntary separations of CONFIRMED

probationers is greater among female officers than

among males.

H11: The rate of involuntary separations for CONFIRMED AS TO

corruption is greater among male officers than among BRIBERY; REJECTED

female officers. ASTOALLPROFIT-

MOTIVATED

MISCONDUCT

H12: The rate of involuntary separations for brutality CONFIRMED

and other non-profit abuses is greater among male officers

than among female officers.

H13: The rate of involuntary separations for drug test CONFIRMED

failures and refusals is greater among female officers than

among male officers.

H14: The rate of involuntary separations for non-line of REJECTED: FEMALE

duty criminal conduct (e.g., off-duty thefts and fraud; drug RATE HIGHER

crimes) is greater among male officers than among female

officers.

H15: The rate of involuntary separations for CONFIRMED

administrative rule breaking is greater among female

officers than among male officers.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xx

H16: The rate of involuntary separations of CONFIRMED AS TO

probationers is greater among non-white officers than BLACKS; REJECTED

among white officers. AS TO HISPANICS

AND OTHERS

2

H17: The rate of involuntary separations for corruption CONFIRMED AS TO

is greater among non-white officers than among white BLACKS; REJECTED

officers. ASTOHISPANICS

AND OTHERS

2

With the exception of separations for brutality (where we confirmed H19, that

white officers= rate would be highest), the pattern in all our analyses involving officers=

race was consistent. Over time, the separation rates of Hispanic officers have decreased

so that they have become near indistinguishable from the rates for Whites. Because of

their very low representation in the NYPD, the rates for AOthers@ (mostly Asian officers)

were statistically meaningless in the early years covered by our study. As the

representation of Asians in the NYPD has grown, their separation rates have recently

been much like those for Whites and Hispanics. The rates for Black officers, which

started out much higher than those of other groups, also have decreased, but remain

considerably higher than those for the other three major racial groups.

H18: The discrepancy between white and non-white REJECTED AS TO

officers' rates of involuntary separation for corruption is RANK; UNTESTABLE

accounted for by differential patterns of assignment and rank. AS TO ASSIGNMENT

H19: The rate of involuntary separations for brutality and REJECTED; WHITE

other non-profit abuses is greater among white officers than RATES LOWER THAN

among non-white officers. OR EQUAL TO BLACK

AND HISPANIC RATES

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xxi

H20: The rate of involuntary separations for non-line of CONFIRMED, WITH

duty criminal conduct (e.g., off-duty thefts and fraud; drug BLACK RATES

crimes) is greater among non-white officers than among HIGHER THAN ALL

white officers. OTHERS

H21: The rate of involuntary separations for drug test CONFIRMED AS TO

failures and refusals is greater among non-white officers BLACKS; REJECTED

than among white officers. AS TO HISPANICS AND

OTHERS

H22: The rate of involuntary separations for CONFIRMED , WITH

administrative rule breaking is greater among non-white BLACK RATES FAR

officers than among white officers. HIGHER THAN ALL

OTHERS

H24: The rate of involuntary separations of CONFIRMED

probationers is greater among officers who were less than

22 years old when appointed than among officers who were

22 or more years old when appointed.

H25: The rate of involuntary separations for corruption REJECTED

is greater among officers who were less than 22 years old

when appointed is greater than among officers who were

22 or more years old when appointed.

H26: The rate of involuntary separations for brutality REJECTED

and other non-profit abuses is greater among officers who

were less than 22 years old when appointed than among

officers who were 22 or more years old when appointed.

H27: The rate of involuntary separations for non-line of REJECTED

duty criminal conduct (e.g., off-duty thefts and fraud; drug

crimes) is greater among officers who were less than 22

years old when appointed than among officers who were 22

or more years old when appointed.

H28: The rate of involuntary separations for drug test REJECTED

failures and refusals is greater among officers who were

less than 22 years old when appointed than among officers

who were 22 or more years old when appointed.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xxii

H29: The rate of involuntary separations for administrative REJECTED

3

rule breaking is greater among officers who were less than

22 years old when appointed than among officers who were

22 or more years old when appointed.

H30: Rates of involuntary separation for all types of police

misconduct are higher for the following categories of

officers than for other officers:

H30a: officers who were dismissed by previous CONFIRMED

employers.

H30b: officers whose prior employers gave police CONFIRMED

investigators derogatory information about them.

3

Readers may wonder how we confirmed H24, that officers hired at ages 20-21

were more likely than others to be separated, when the data did not confirm any of the

offense-specific hypotheses (H25-H29) to the same effect. The answer is that we found a

consistent pattern in which younger recruits were somewhat more likely than others to

end their careers in separations for profit-motivated offenses; on-duty abuse; non-line of

duty offenses; and administrative rule violations. Although these were not statistically

significant, they did make a difference in the aggregate.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xxiii

H31: Officers with military records that include no REJECTED; MILITARY

discipline are less likely than officers without military VETERANS MORE

experience or with military disciplinary histories to be LIKELY THAN

nvoluntarily separated. NON-VETERANS TO BE

DISCIPLINED

4

H32: Rates of involuntary separation for all types of police CONFIRMED

misconduct are inversely associated with officers' years of

education at entry into the NYPD.

H33: Officers= years of education at entry into the NYPD CONFIRMED

is positively associated with movement into supervisory

and management ranks.

H34: Officers= educational attainment after entry into the UNTESTABLE:

NYPD is positively associated with movement into supervisory INSUFFICIENT

and management ranks. DATA

4

. There was considerable within variation in separation rates among military

veterans. Former Marines were more likely that veterans of other services to be

separated. So were veterans who served more than a four-year military enlistment; those

who were disciplined in the military; those who joined the military immediately after the

1974 abolition of the draft; and those who had not advanced above the ranks of corporal

or seaman. Navy and Air Force veterans and former military officers had very low

separation rates. In any event, much of the association between military service and

separation washed out during our multivariate analysis, suggesting that it was

confounded by other variables (e.g., age at appointment; race; level of education,

employment history).

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xxiv

H35: Rates of involuntary separation for all types of police CONFIRMED

5

misconduct are inversely associated with officers' Police

Academy academic averages.

H36: Rates of involuntary separation for all types of

misconduct are positively associated with the following

variables (all standardized by rates per year of service):

H36a: prior citizens' complaints: UNTESTABLE:

INSUFFICIENT

DATA

H36b: prior supervisory disciplinary actions; UNTESTABLE:

INSUFFICIENT

DATA

6

H36c: prior Abelow standards@ evaluations on UNTESTABLE:

performance evaluations; INSUFFICIENT

DATA

H36d: prior line of duty civil suits; UNTESTABLE:

INSUFFICIENT

DATA

5

For purposes of this analysis, we excluded officers who were separated while on

probation. We did this on grounds that, while it was not misconduct, their poor Academy

performance might have played a role in their separations. Thus, this analysis included

only officers who were already tenured and who were separated as the result of decisions

made by officials who would not take into account their recruit school performance.

Study officers also performed more poorly than control officers on Police Academy

physical examinations. During their recruit training, they also were more often sick;

injured, late, disciplined, and held back from graduating with their classes than were

study officers. They received fewer Aexcellent@ performance ratings; more Apoor@

performance ratings, and were deemed to have performed more poorly than study officers

in Law, Police Science, Social Science, and Physical Training. Despite all this, they

received higher Aoverall@evaluations (mean=2.80 on a 0-5 scale) than did study officers

(mean=2.58). Clearly, there is a need to bring the Police Academy=s subjective ratings

of recruits into line with objective measures of recruits= performance.

6

Because the origin of complaints is not always clear (e.g., did it originate with a

citizen or with a police official?), we were unable to test H36a and H36b as stated. We

were able to test and confirm the hypothesis that study officers were more likely than

control officers to have histories of prior complaints.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xxv

H36e: prior line of duty injuries; UNTESTABLE:

INSUFFICIENT

DATA

H36f: prior line of duty vehicle accidents; UNTESTABLE:

INSUFFICIENT

DATA

H36g: prior designations as chronically sick. UNTESTABLE:

INSUFFICIENT

DATA

H37: Rates of involuntary separation for brutality UNTESTABLE:

and other abuses are positively associated with INSUFFICIENT

rates of departmental commendations. DATA

We also employed Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to extract three dimensions of

officers= histories:

- Criminal History, including violent and property crime arrests, juvenile

delinquency findings, misdemeanor arrests and convictions, public order arrests,

moving and parking violations, and driver=s license suspensions.

- Work History, including numbers of jobs, workman compensation claims, 30

day (or longer) periods of unemployment, jobs from which fired, work-related

disciplinary actions, and derogatory comments by prior employers.

- Social Condition, including officers= social circumstances at the time of their

appointment, including marital status (coded as a series of binary variables);

number of children; and whether officer was actively enrolled in school at time of

appointment.

The PCA identified subsets of these three dimensions comprised of closely related

variables. These were then entered into a Logistic Regression Analysis designed to find the

factors that most significantly distinguished between study and control officers. While

controlling for all other covariates, the strongest risk factors for termination were whether an

officer was black (the derived odds ratio showed that black officers were 3.27 times more likely

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xxvi

than whites to be involuntarily separated; had an average of one or more complaints per year of

service (3.03 times as likely as officers with fewer complaints to be separated); and worked in

inspector precincts at the time of the incident leading to separation (2.48 times more likely than

officers assigned to staff units to be dismissed).

Other significant risk factors for police misconduct included Latino (B=.69), being

assigned to DI precincts (B=.81), captain precincts (B=.71), police academy/field training units

(B=.61), having criminal histories (B=.20), public order offense histories (B=.58), prior

employment disciplinary problems (B=.32), and prior employee reliability problems (B=.15). In

sum, minority-group officers had higher probabilities than white officers of incurring an

organizational response to known misconduct; officers assigned to posts that placed them in

regular contact with the public under relatively unsupervised conditions (i.e., precincts), or to

posts at times in their careers when they did not enjoy civil service protection (i.e., police

academy/training units) were at greater risk of being separated for misconduct; officers who

were officially recognized disciplinary problems during both their pre-police and NYPD

occupational tenures were at greater risk than others of being dismissed for police misconduct;

g

and officers who had an officially sanctioned history of deviance had higher odds than others of

being dismissed for misconduct. These multivariate findings largely support our bivariate results

(see Table IX-1).

The logistic regression model also found that length of service; holding an Associate or

Bachelor=s degree at appointment, and increased age at appointment weighed against

g

To assure that we did not confound prior departmental complaint history and the

events that may have led to officers= separation in this analysis, we treated officers who

had received complaints during careers that lasted less than one year as missing cases.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xxvii

involuntary separation. In addition, officers whose fathers had served as NYPD officers were

significantly less likely (albeit, not substantially) than other officers to be dismissed for

misconduct, and officers who achieved a supervisory rank were less likely than line officers to

be dismissed for misconduct. These findings suggest that overall, academically well prepared

officers, those who were ambitious, and those with parental links to the NYPD were less likely

than other officers to either engage in, or be sanctioned for, occupational misconduct.

The logistic regression model also identified factors statistically not associated with

occupational deviance. Among these was military service. Our bivariate findings showed that

military service was significantly related to police misconduct. The multivariate findings did not

support this earlier result, however, suggesting that the bivariate relationship may have been

confounded by other factors that were not controlled. It is possible, for example, that while

considering the effects of age at appointment, level of education, and employment history,

military service may be an unimportant independent factor in the prediction of police

misconduct. In addition, officer sex, prior police service, and background investigator

recommendation were non-significant in the prediction of misconduct. It should be noted that

although the mayor at time of officer=s separation was included in the model as a control for the

effects of social and political climates in New York City, it was a non-significant predictor of

police misconduct.

Contrary to what we had expected and hypothesized, our bivariate analyses showed that,

except for cases involving on-duty abuse, female officers generally had higher separation rates

than their male colleagues. Like military service, however, gender washed out of our

multivariate analyses, suggesting that the bivariate relationships we found had been affected by

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xxviii

other factors. Here, we also suspect that low absolute frequencies may have distorted the results

of our bivariate analyses to some degree.

In all, therefore, our work confirms the conventional wisdom regarding the police: young

officers who entered the police service with minimal educations, and records of prior

delinquency, criminality, and poor prior employment; who did not advance in the NYPD; who

worked in busy patrol assignments; and who accumulated histories of complaints were more

likely than others to have ended their careers in involuntary separation. Conversely, well-

educated officers with clean histories, perhaps including a family history in the NYPD, and who

worked their way to advanced rank were least likely to be involuntarily separated from the

agency.

Overriding all this is the race issue. We found that, despite the many years in which

African-American officers they have been a major presence in the department, and despite their

many contributions to it and to New York City, where discipline is concerned, they remain an

outgroup in the NYPD. They are far more likely than other officers to be involuntarily separated

and, we found in earlier work (Fyfe, et al., 1998), to be subjects of less severe discipline, as well.

It is hard to determine the extent to which this may be the result of discrimination, but our

analyses suggest that the disparity among black officers has resulted largely from separated

officers= involvement in situations (e.g., criminal or drug related behavior) in which

administrators= paths of action are clearly defined and leave little or no room for arbitrariness.

This finding is consistent with other work, both in an out of policing, that has found

strong associations between race and deviance, and official responses to the latter. We

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xxix

recommend further study of this issue, and suggest research that examines the status of African-

American police officers in the NYPD and elsewhere.

We also reached far more heartening findings regarding gender, race, and officers=

misconduct:

- the greater the percentage of women in the department, the less likely women are

to be fired;

- the greater the percentage of men in the department, the more likely men are to be

fired;

- the greater the percentage of whites in the department, the more likely whites are

to be fired;

- the greater the percentage of Hispanics, Asians, and other non-white groups in the

department, the less likely they are to be fired.

Taken together, these findings produce what is for us a very important conclusion: as the

NYPD has become more diverse by gender and race, it has become significantly better

behaved.

h

h

Probably because the percentage of black officers in the NYPD has remained

relatively flat over the years studied, the relationship between it and black separation rate

is non-significant. The percentage of black officers in the NYPD ranged between 10.7%

in 1986 (n=2,799) to 11.6% in 1994 (4,293), then increased to 13.9% by 1996 (5,155).

This comparative jump over the last two years resulted largely from the merger of the

more diverse New York City Transit and Housing police departments into the NYPD.

During 1986-96, NYPD=s percentage Hispanic increased from 9.5% (2,505) to 16.7%

(6,205); percentage Asian/Other went from 0.6% (154) To 1.3% (478). Percentage

female increased from 9.5% (2,504) to 15% (5,684). Percentage white decreased from

79.2% (20,816) to 68.1% (25,240).

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xxx

There may be many reasons for this finding. It has long been claimed that domination of

policing by a single racial group has produced a solidarity that includes such unhealthy aspects

as a willingness among officers to tolerate misconduct by their colleagues. To the extent that

this may have existed in the NYPD, it may be breaking down as the NYPD has become more

diverse. Alternatively, some believe that, as the numbers and, presumably, the influence of

minority officers on the organization increase, their vulnerability to disciplinary arbitrariness has

decreased. The decreases in career ending misconduct may have to do with the Internal Affairs

Bureau=s greatly increased vigor, or with the increasing rigor of drug testing over the years

studied. The department also grew significantly so that, independent of their gender and race,

the newcomers may have wrought great changes in its culture.

These are subjects for future research, but our data seem to provide the best evidence to

date that diversity produces a healthier brand of policing. Thus, this finding gives researchers

what they want B an avenue for further study. More important, we think, it also gives

administrators reason to believe that their efforts to enhance diversity in the ranks have a highly

desirable product: an organization in which the percentage of officers of all genders and races

who disgrace themselves and their agency is significantly decreased. This finding may have

great significance not only for police administrators, but for all those who charged with running

organizations, in and out of the public sector.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xxxi

Acknowledgments

The debts owed for this study are enormous. We are extremely grateful to former

National Institute of Justice Director Jeremy Travis, who funded our work and who, more

importantly, encouraged us and understood the difficulties we encountered while doing

it. Fyfe, especially, wants Travis to know how grateful we are, and how delighted he is

that Travis has just been named to be his boss when Fyfe returns to John Jay College,

where Travis has become president. Jeremy=s encouragement and patience have been

continued by NIJ=s current director, Sarah Hart, and we are very grateful to her, as well.

Dr. Sally Hillsman, the former Director of NIJ=s Office of Research and Evaluation,

championed this research from the time of its inception and through a major mid-course

shift in direction. Bryan Vila, the Chief of NIJ=s Crime Control and Prevention

Research Division, deserves thanks for his encouragement. Dr. Steven Edwards, our

original Project Monitor, was a model of support and encouragement. Steve was always

there when we needed him, making suggestions, but never pressing us. Maggie Heisler,

who succeeded Steve in these duties, followed his working style, for which we are

greatly indebted to her, as well. Paul McCauley of Indiana University of Pennsylvania

planted the seed that grew into this study. Robert Tillman of St. Johns University

supervised data collection, which was an enormous task done very well. Peter Jones of

Temple cleaned the data and made them suitable for analysis. We could not have done

the work without him.

We also are grateful to Michael Farrell, NYPD=s Deputy Commissioner for

Policy and Planning when we started this project and its Deputy Commissioner for

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xxxii

Strategic Initiatives when we finished it, and to Chief of Internal Affairs Charles

Campisi, Chief of Housing Joanne Jaffe, former Deputy Commissioner for Trials Rae

Koshetz, and Deputy Chief Diana Pizzuti who reviewed drafts of our work, assuring that

it was accurate. Mike Farrell also was our point of entree to the NYPD. Mike and his

support for the work were keys to the virtually unlimited access we subsequently were

granted. His staff, especially Deputy Inspector Joseph Lovelock, Sergeant Vincent

Henry, and Carol Frazier, helped us to get the work off the ground, and we owe them

thanks. Assistant Commissioner Philip McGuire, an old friend who has been helping

Fyfe with research in the NYPD since the days of his doctoral dissertation, was a great

resource to us. There is a vast amount of information stashed here and there in the

hundreds of NYPD units. Invariably, Phil knows precisely where it is, what it means,

and how to get it. For more than a quarter-century, Phil Has been a tremendous asset to

the department, to the City, and to scholars. He is always eager to assist, to make

suggestions that facilitate research and assure its quality, and has played a central role in

scholarly and administrative analyses of the NYPD and its problems.

Mike Farrell enthusiastically endorsed our proposal, and passed it on to then-

Police Commissioner William Bratton, who agreed immediately that it was long overdue,

and who made sure that the New York City Police Department opened its doors to us.

His successor, Howard Safir, made the study a priority, and assured that we had

unlimited access to all the records, people, and resources we needed to do our work.

Raymond Kelly, the incumbent police commissioner, has continued this pattern.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xxxiii

On a day-to-day level, we worked most closely with two people and their NYPD

units. Howard Safir called First Deputy Police Commissioner George Grasso a yes

lawyer, an attorney who finds ways to get things done when others might simply say no.

Commissioner Grasso and his staff certainly did that for us, and without them, this

project would not have been what we hoped. We are particularly indebted to him, to

Inspector Patrick Conry, to former Sergeant (now Firefighter) Michael Ansbro, and to

retired Detective John Totaro.

Most of our work was quartered in the Employee Management Division of the

Personnel Bureau. EMD=s Director, Arnold Wechsler, was a terrific asset. He helped

us organize the immense data collection and coding processes involved in our study,

helped us to identify and recruit project staff, resolved differences among the people who

worked with and for us, and navigated us through what would otherwise have been

nightmarish logistics. He, retired Deputy Inspector Francis Smith, and retired

Administrative Manager Elaine Glass acted as liaison between us and former Chief of

Personnel Michael Markman who, before dying too young, also helped us greatly. We

are grateful to them all.

We consulted with NYPD=s former Deputy Commissioner for Training James

O=Keefe and with his staff, especially Lt. Paul Kennedy of the Academy=s Research

Unit. Both were very helpful in pointing us to data related to our study officers=

performance in training which, as our research subsequently showed, certainly was

worthy of close analysis.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xxxiv

The people who got this work done, who located, pulled, and pored through the

thousands of files we studied are the project=s New York City Police Department staff,

and are identified at the front of this report. We thank them one and all for their hard

work and good humor under pressure. We are especially grateful for their many

suggestions, which helped to both facilitate data collection and to increase the quality of

the information we compiled.

During the course of this project, we also worked with three focus groups, who

must necessarily remain anonymous. One was a group of patrol officers, selected from

across the city. A second was a group of police patrol sergeants, and the third were

patrol precinct commanders at the captains and deputy inspector ranks. We tapped their

expertise and perceptions to determine what they saw as the characteristics, pre-

employment and in-service experiences, and general conditions associated with police

disciplinary problems. Their insights were invaluable, and helped us to focus our

research and to develop and refine the data collection instruments and techniques we

employed.

We also assembled two advisory committees to work with us. The first were

people who possess great substantive knowledge of police and New York City and,

without compensation, they devoted considerable amounts of their very valuable time

and resources to help us focus and refine the study. They include former NYPD

Department Advocate Walter Connery, who also headed the Immigration and

Naturalization Service=s anti-corruption efforts; Henry DeGeneste of Prudential-Bache,

formerly Chief of the Port of New York and New Jersey Authority Police and a member

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xxxv

of the Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies; former NYPD

Chief of Personnel Michael Julian of the Madison Square Garden Corporation; and

Professor Jerome Skolnick of New York University Law School, an internationally

renowned scholar of the police. Richard Koehler of John Jay College of Criminal

Justice, another former NYPD Chief of Personnel and ex-New York City Corrections

Commissioner, also served with us briefly, but had to leave the advisory committee

because of a conflict of interest. All five are good friends, whose combined expertise on

the matters we studied is without equal. We owe them all big time.

Our methodological advisory committee included Professor Michael Maxfield of

Rutgers University=s School of Criminal Justice. Mike is the co-author of

Maxfield/Babbie (1997), the standard criminal justice research text, and needs no

introduction to anyone who has studied human behavior over the last generation.

Professor Joan McCord was Fyfe=s colleague at Temple, and has built an international

reputation conducting longitudinal studies of deviant behavior. Both Mike and Joan

carefully reviewed the first draft of this report and made comments and suggestions that

have improved it immensely. Joan=s death earlier this year after a very brief illness, was

particularly painful. We with her loss, we lost a great friend and colleague, and the world

of social science lost a major contributor.

We owe special debts to two people. Dr. Carl Silver, professor emeritus at Drexel

University and Joan McCord=s husband, was with us from the beginning of this project.

His expertise in research design is reflected in the proposal for this project and, we are

both well aware, was a major factor in convincing NIJ=s reviewers, staff, and director

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

xxxvi

that this was a feasible and worthwhile endeavor. We hoped to work with Carl until this

study was completed and beyond, although we all knew that Carl was battling an

inevitably terminal illness long before this project got off the ground. Carl=s valor in his

long fight against death was an inspiration to us all and to Joan, as was his unremitting

intellectual vigor and enthusiasm for this, the last major research endeavor of his life.

We hope that our product is worthy of Carl.

Much of the data we studied were stored in Brooklyn in the Old Records facilities

of the Central Records Division. CRD=s Director Linda Scotti was of great assistance in

arranging for access to that facility. We are indebted to Linda, and were extremely

saddened by her premature death. We have all suffered a great loss, and we extend our

condolences to Linda=s family.

This study needs one last preface. Although the subjects of our research include

policing=s worst, we want to make plain that we do not view the bad cops we studied as

in any way representative of the NYPD or of American policing in general. Far more

representative, we believe, are the actions of New York cops on September 11, 2001. On

that terrible day and on every day since, George Grasso observed, New York cops

showed everybody that they were the kind of people those of us who have worked with

them always knew them to be.

Thus, we dedicate this study of bad cops and their good cop colleagues to Joan

McCord, Carl Silver, Linda Scotti, Mike Markman, and to the thousands upon thousands

of good cops who make the NYPD the world=s best police agency.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

1

I. INTRODUCTION

This is a study of police officers whose careers have ended in disgrace. Such bad

cops are a concern, most obviously because the most visible of them so severely hurt the

people they are paid to protect. Regardless of whatever commendable actions they may

have performed during their police careers, the Los Angeles officers who beat Rodney

King and the New York officers who beat and sodomized Abner Louima caused terrible

damage to both of these individuals. They changed the lives of their victims forever, and

will themselves forever be regarded as both symbols and causes of the gap of rage and

distrust that has too often characterized relationships between our police and our

communities of color.

FINANCIAL COSTS OF FAILED POLICE CAREERS

In addition to the damage they sometimes inflict on others and on the relationship

between the police and the community, there are other reasons to study police officers

whose careers end in disgrace. New police officers represent a significant commitment

on the part of the governmental entities that employ them. Typically, new officers enter

their departments only after long and elaborate screening processes designed to select the

best possible candidates in the fairest possible ways. Over the last generation, this

process has been the subject of litigation and legislation designed to enhance its validity

and to remove from it all traces of discrimination and arbitrariness. Thus, bad cops are

worth studying because they may tell us something about whether these ideals have been

achieved and whether the processes used to select officers do, in fact, predict satisfactory

police performance.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Fyfe and Kane --

2

Further, the process of finding, selecting, training, and certifying new officers is

very costly. In most places, it involves the administration of a written examination, as

well as psychological, medical, physical performance and agility tests, and a background

and character investigation. Once this first set of steps is completed, new officers are

placed on the agency payroll, but they still are not working cops, who make a direct and

immediate contribution to the public welfare. Instead, they are likely to spend six months

or more in formal classroom training, followed by several additional months in a field

training experience in which they work under the tutelage of senior officers who grade

their performance in actual street situation. Thus, from the moment individuals apply to

become police officers until the completion of recruit training, they cost their employers

the expense of the screening process; the cost of either running and staffing an agency

training facility or contributing to the cost of sharing in a regional or state police

academy; and, usually, at least a year=s pay and benefits. During this period, new

officers= employers get little return on their investment, save perhaps the rookies=

occasional turn directing traffic or working at parades and other special events.

Once new officers= formal entry level training is completed, they may, as in New

York City, the jurisdiction we studied, continue on probationary status for as much as an

additional year.

1

During this period, they are expected to learn policing by doing it, and

to demonstrate that they are worthy of jumping from probation to tenure. Those who do

1

The NYPD=s probationary period for new officers is two years. New sergeants,

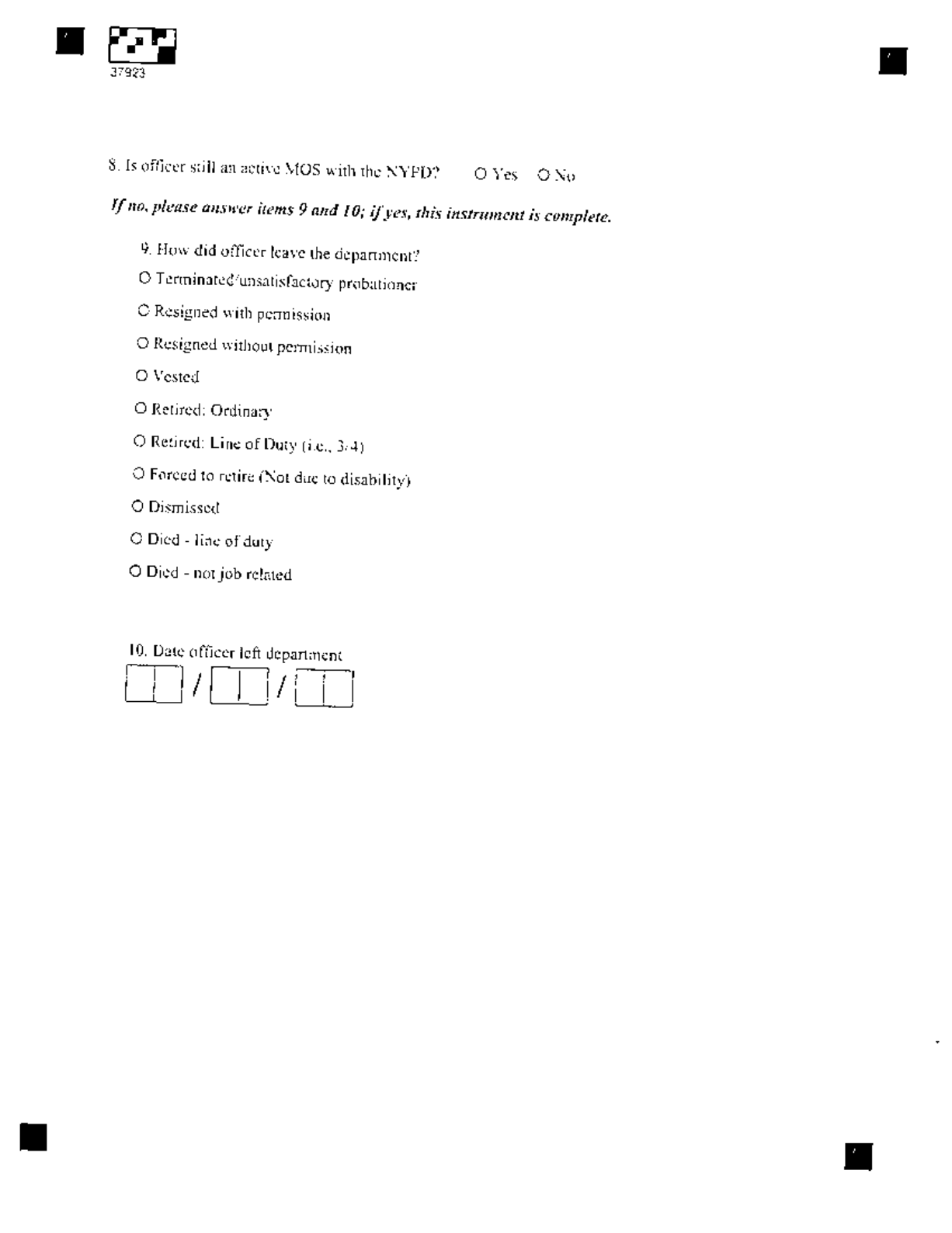

lieutenants, and captains hold their ranks on a probationary basis for one year.