I

PAY

FEBRUARY 2017

The High Cost of Jailing

Texans for Fines & Fees

OR

STAY

REPORT TEAM

TEXAS APPLESEED

Deborah Fowler Executive Director

Mary Mergler Director, Criminal Justice Project

Kelli Johnson Communications Director

Yamanda Wright Director of Research

Alexis McLauchlan Intern

TEXAS FAIR DEFENSE PROJECT

Rebecca Bernhardt Executive Director

Emily Gerrick Staff Attorney

Tricia Forbes Deputy Director

Susanne Pringle Legal Director

ABOUT TEXAS APPLESEED

Texas Appleseed’s mission is to promote

social and economic justice for all

Texans by leveraging the skills and

resources of volunteer lawyers and

other professionals to identify practical

solutions to difcult systemic problems.

Texas Appleseed

1609 Shoal Creek Blvd.

Suite 201

Austin, TX 78701

(512) 473-2800

www.texasappleseed.org

www.facebook.com/texasappleseed

@TexasAppleseed

ABOUT TEXAS FAIR DEFENSE PROJECT

The Texas Fair Defense Project’s

mission is to ght for a criminal

justice system that respects the rights

of low-income Texans. We envision

a new system of justice that is fair,

compassionate and respectful.

Texas Fair Defense Project

314 E. Highland Mall Blvd.

Suite 108

Austin, Texas 78752

(512) 637-5220

www.fairdefense.org

www.facebook.com/TexasFairDefenseProject

@FairDefense

First Edition ©2017, Texas Appleseed and Texas Fair Defense Project. All rights are reserved except as follows: Free copies

of this report may be made for personal use. Reproduction of more than ve copies for personal use and reproduction for

commercial use are prohibited without the written permission of the copyright owners. The work may be accessed for

reproduction pursuant to these restrictions at www.texasappleseed.org or www.fairdefense.org.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

01 INTRODUCTION 01

02 AN INESCAPABLE CYCLE OF DEBT & JAIL 04

03 COSTS OF THE CURRENT SYSTEM 29

04 RECOMMENDATIONS 36

01

Across Texas, local and state leaders are realizing that the use of jail time for

fine-only offenses is costly, counterproductive, a threat to public safety and a violation

of Texans’ fundamental legal rights.

For low-income Texans, a ticket for a minor offense like speeding, jaywalking, or having a broken

headlight can lead to devastating consequences for the individual, as well as that person’s family

and community. If someone is unable to pay a ticket right away, the cost compounds over time, often

resulting in more tickets, nes and fees. Failing to pay or to appear in court can lead to an arrest

warrant and jail time.

Current practices often result in the suspension of, and inability to renew, driver’s licenses, as well as

the inability to register vehicles. They also result in millions of arrest warrants being issued annually.

When people are picked up on a warrant for failure to pay tickets, nes and fees, they are often booked

into jail and made to pay off their debt with jail credit, usually at a rate of $50 to $100 a day.

1

These

practices are widespread – over 230,000 Texans are unable to renew expired licenses until their nes

and fees are paid off,

2

and about 1 in 8 ne-only misdemeanor cases are paid off in whole or in part

with jail credit.

3

Low-income Texans are being set up to fail by the way nes and fees are handled, and they are often

driven deeper into poverty. Suspending a person’s driver’s license makes it illegal to drive to work;

issuing an arrest warrant can make it nearly impossible for to nd employment; and sending that

person to jail can lead to the loss of a job and housing. The public’s safety is harmed when low-risk

people languish in jail. This system hurts Texas families and drains our public resources at great

expense to taxpayers.

In many cases, the current system also violates state and federal law. The United States Supreme Court

has held that incarcerating somebody because of unpaid nes or fees without a hearing to determine if

they are actually able to pay the nes and fees violates the Equal Protection and Due Process clauses of

the 14th Amendment.

4

Texas state statute also makes clear that a person cannot be jailed for unpaid

nes when the nonpayment was due to indigence.

5

1 Tex. Code of Crim. ProC. Ann. art. 45.048(2) (West 2015).

2 EmailfromPamelaHarden,Tex.Dep’t.ofPub.Safety,toSushmaSmith,ChiefofSta,OceofTex.SenatorJosé

Rodríguez,(Nov.9,2016)(onlewithauthors).

3 offiCe of CourT AdminisTrATion, AnnuAl sTATisTiCAl rePorT for The TexAs JudiCiAry: FY 2015 at Detail-45,48 (2016) (hereinafter

AnnualStatisticalReport)available at http://www.txcourts.gov/media/1308021/2015-ar-statistical-print.pdf.

4 See Tate v. Short, 401 U.S. 395 (1971); Bearden v. Georgia, 461 U.S. 660 (1982).

5 Tex. Code of Crim. ProC. Ann. art. 45.046(a) (West 2015).

01 Introduction

CONTINUED ON NEXT PAGE >

02

While some courts feel intense pressure to attempt to increase collection rates by threatening

people with incarceration, others have been successful without using jail time as a punishment

for failure to pay. Most notably, the San Antonio Municipal Court stopped ordering people to lay

out nes in jail in 2007. It found that court revenue did not decrease as a result, nor was there a

noticeable change in driver behavior in the city.

6

Many low-income Texans are never able to escape the cycle of debt caused by our municipal and

justice courts’ ticketing systems and will spend years accumulating nes that force them in and

out of jail. This report offers recommendations for ending the practice of jailing people for ne-

only offenses and creating a better system that holds people accountable while saving money,

increasing public safety and treating all Texans fairly.

What are fine-only offenses?

Texas’ 928 municipal courts and 807 justice courts (sometimes called Justice of the Peace or JP courts)

7

handle

more than 7 million new criminal cases each year.

8

The criminal cases in these courts are the lowest level of misdemeanors under Texas law, by statute punishable

by a ne alone and no jail sentence.

9

These include most trafc offenses, city ordinance violations, other Class C

misdemeanors, and criminal parking violations.

10

• Trafc offenses include moving violations such as speeding, running a red light, or failure to yield. They

also include other violations like driving with an invalid license or without a license, driving with defective

equipment, failure to maintain nancial responsibility (i.e., no insurance), or having an expired registration.

• Non-trafc Class C misdemeanors are violations of state law that are punishable by a ne up to $500, such

as public intoxication, theft of something valued less than $100, disorderly conduct, and parent contributing

to nonattendance (truancy).

6 JazmineUlloa,The Price They Pay, AusTin AmeriCAn-sTATesmAn(May20,2016)(“’Contrarytofears,therewerenospikesin

traccrimes,andthecitydidnotloserevenue,’[SanAntonioMunicipalCourtPresidingJudgeJohn]Bullsaid.”).

7 AnnuAl sTATisTiCAl rePorT, supra note 3, at vi.

8 Id. at Detail-45, 48.

9 Id. at vi.

10 ClassCmisdemeanorsaredenedasviolationspunishedbyaneofnomorethan$500,orasanyoensepunishable

byanealone.Certaintracoensesarene-onlymisdemeanors,andarepunishedbyaneofnogreaterthan$200.

Parkingviolationsareoftendierent,inthatmostparkingtickets(butnotall)arecivilratherthancriminalviolations,

similartoredlightcameraviolations.Tex. Gov’T Code Ann. § 29.003 (West 2015); See, e.g.,CollegeStation,Tex.,Trac

CodeSec.10-4C.2(b)(ii)(2016).

03

• City ordinance violations include all sorts of regulations on conduct within city limits, including animal-

related violations (e.g., leash laws); health and safety ordinances (e.g., no running water in a residence, food

safety regulations at a restaurant); and ordinances typically targeting the homeless population (e.g., no

camping in the city limits, no sitting or lying down, and no solicitation or panhandling).

For purposes of this report, we will use the term “ne-only offense” to include all criminal offenses punishable by

a ne alone over which the municipal and justice courts have jurisdiction.

The following chart demonstrates the breakdown of the types of criminal cases handled by Texas municipal and

justice courts.

11

More than three-fourths of these are trafc violations.

11 AnnuAl sTATisTiCAl rePorT, supranote3,atStatewide-11.

04

A. HOW DOES ONE TICKET LEAD TO MORE TICKETS, FINES AND FEES?

02 an inescapable

cycle of debt and jail

05

When low-income people receive a trafc ticket, the initial ne amount for that ticket is only a

portion of what they may ultimately owe. There are also court costs in addition to the ne that

courts automatically assess in every case, which typically range from $60 to $110.

12

Courts assess more fees for people who fail to pay their tickets immediately. For example, if

a person is placed on a payment plan, there will be a $25 payment plan fee for each ticket, in

addition to transaction fees that many courts charge each time a payment is made.

13

People are

also charged $30 when a hold is placed on their licenses and $20 when a hold is placed on their

registration due to unpaid nes.

14

To release those holds, people must pay the fees on each ticket

that led to a hold.

Failure to appear in court or pay a ticket often leads a court to issue an arrest warrant, which adds

a $50 warrant fee to the original ticket.

15

In addition, local governments sometimes contract with

private collection agencies or law rms to collect outstanding balances, and these agencies charge

another fee of up to 30 percent of the amount owed when collecting the debt.

16

For a person who fails to appear in court or cannot pay off their ticket when it is due, this means

that a single ticket with a ne amount of $100 can easily more than quadruple when court costs

and fees are attached.

Fine (e.g., failure to maintain a single lane) $ 100.00

Court Costs $ 103.00

Check Return Fee $ 30.00

Payment Plan Fee $ 25.00

License Renewal Suspension Fee $ 30.00

Capias Pro Fine Warrant Fee $ 50.00

Scofaw Registration Renewal Fee $ 20.00

Collection Fee (30%) X 1.30

TOTAL $ 465.40

12 Filing Fees and Court Costs, Tex. JudiCiAl BrAnCh, http://www.txcourts.gov/publications-training/publications/ling-fees-

courts-costs/(lastvisitedSept.9,2016).

13 Tex. loC. Gov’T Code Ann. § 133.103(2) (West 2015).

14 Tex. TrAnsP. Code Ann. § 706.006 (West 2015); § 502.010(f).

15 Tex. Gov’T Code Ann.§102.021(3)(B).

16 Tex. Code Crim. ProC. Ann. art. 103.0031(3)(b).

06

In addition to extra fees, lower income people tend to receive more tickets due to their poverty and

inability to pay. Most jurisdictions put holds on delinquent persons’ licenses and car registrations

until they can clear their tickets. Also, nearly 1.4 million Texans have license suspensions

resulting from unpaid Driver Responsibility Program surcharges, many if not most of which stem

from low-level trafc offenses.

17

When people with license holds or suspensions lose their ability

to register their vehicle, the car becomes a moving target for more stops and tickets. Once these

drivers are pulled over, they will most likely receive at least three tickets for that one stop: one

for not having a valid license, one for expired registration, and one for driving without insurance

(since it is very difcult to get insurance if you do not have a valid license).

This vicious cycle of more frequent stops resulting in multiple tickets may be amplied if the

driver misses a court date. If someone fails to appear in court, many jurisdictions enter a Failure to

Appear charge (an additional Class C offense) for each existing ticket, turning three tickets from a

single stop into six tickets. This is especially likely to happen when people already have warrants

for prior unpaid tickets and are afraid that they will be arrested if they appear in court for the new

tickets.

When the number of tickets someone has multiplies, so do the associated fees. A person who

needs a payment plan for six tickets will owe an additional $150 in payment plan fees instead of

$25, and if that same person misses a payment, there will be a $50 warrant fee per ticket, totaling

an extra $300. Each unpaid ticket will also put an additional hold on the person’s license and

registration, with a $30 fee per license hold ($180 total) and a $20 fee per registration hold ($120

total). It is easy to see how debt accumulates quickly from just one trafc stop, trapping people in a

cycle of debt they cannot escape.

B. HOW DO FINE-ONLY OFFENSES LEAD TO ARREST WARRANTS?

Fine-only offenses can lead to arrest warrants in two situations: rst, when a person fails to show

up for a court date; and second, when a person fails to satisfy nes or fees.

1) FAILURE TO APPEAR WARRANTS

The rst kind of warrant that can lead to arrest for nes and fees is a warrant for Failure to Appear.

Most often, people are charged with a ne-only offense when they receive a ticket written by a

law enforcement ofcer. The ticket instructs them to pay the ne and court costs, or alternatively,

to appear in court on or by a certain date. Only people who cannot pay immediately or want to

contest the ticket must show up in court.

17 Email from Pamela Harden, supra note 2.

07

There are several compelling reasons low-income Texans do not show up for their court dates:

• Lack of transportation: Many people lack adequate transportation to get to court. They

may also have received the ticket while traveling and cannot afford to travel back to that

jurisdiction to appear in court.

• Employment: Low-income Texans often work in jobs that lack the exibility to allow

them to take time off during the workday to appear at the court at a specic time for their

hearing.

• Lack of understanding of the court system: People who lose their original ticket also

lose the instructions for when and where to appear. They often lack the understanding

to navigate a complicated court system. With no central statewide database to look up

trafc tickets, people may not be able to determine which local court to call to nd out

when and where to appear.

• Fear of arrest: People with warrants for old unpaid tickets are understandably afraid to

appear in court because they might be arrested on the spot, knowing a jail stay would

cause them to lose their job or ability to care for their children. Even many of those

without warrants may fear coming to court for an initial appearance, believing that their

inability to pay the ticket will lead to their being jailed.

18

“Almost everyone I see in jail tells me that they are in the jail due to fear of coming to court.

They fear an approaching police officer at the door ready to arrest them because they

either do not have the money to pay a fine or they failed to appear on a charge.”

– Hon. Ed Spillane, Presiding Judge, College Station Municipal Court and Past President,

Texas Municipal Courts Association

19

The failure to appear in court is a separate crime,

20

so it often leads to another ne-only charge

for which a person will owe additional nes and court costs. When charging an individual with a

Failure to Appear offense, the court typically issues a warrant for the person’s arrest.

18 Basedondozensofinterviewsbyauthorswithindividualswhofailedtoappearforcourtinne-onlycases.

19 Hon.EdSpillane,Op-Ed.,Courts as a Safe Haven: A Positive ‘Ferguson Eect,’ AusTin AmeriCAn-sTATesmAn (Sep. 16, 2016).

20 Tex. PenAl Code Ann. § 38.10 (West 2015).

08

In 2015, Texas municipal courts issued about 1.74 million warrants in ne-only misdemeanor

cases, most commonly for failure to appear in court.

21

Texas justice courts issued approximately

411,000 such warrants.

22

This does not include capias pro ne warrants issued specically for

failure to pay nes.

People who are the subject of a Failure to Appear warrant are at risk of being arrested in some

courts if they voluntarily appear in court to take care of their tickets. Other courts may not arrest

people who come in, but they may still refuse to clear the warrant or set a hearing with a judge

until the person pays some sum of money.

23

This means that people are not even able to see a

judge to negotiate alternative sentences since they cannot afford the amount of money required

to clear the warrant.

2) CAPIAS PRO FINE WARRANTS

The second type of warrant that leads to arrest and jail time in these cases is called a capias pro

ne warrant (commonly called capias warrants) – a specic type of warrant issued for people who

have not paid a ne by its due date.

24

Most people do make their initial court date, but when people

plead guilty or are found guilty, a judge is not required to ask if they can afford the ne and court

costs being imposed.

25

Low-income people often leave court owing amounts they can never pay,

and not knowing what their options are if they cannot pay. Alternatively, the judge may tell them

to talk to the court staff if they cannot pay immediately, only to have the court staff put them on a

payment plan they still cannot afford.

26

When a person fails to pay nes, in full or according to payment plan terms, or if a person fails

to complete community service in the time ordered, the court typically orders a capias pro ne

warrant. In 2015, Texas municipal courts issued approximately 688,000 capias pro ne warrants

in ne-only misdemeanor cases. The justice courts issued approximately 66,000 capias pro

ne warrants.

27

Both capias and Failure to Appear warrants show up on background checks. Anyone with such a

warrant who gets stopped by law enforcement can be immediately taken to jail and booked while

waiting to see a judge. Given the millions of warrants that are issued by municipal and justice

courts annually, hundreds of thousands of Texans are living with an active warrant for their arrest

and are subject to being booked in jail at any time for ne-only offenses.

21 AnnuAl sTATisTiCAl rePorT, supra note 3, at Detail-48, 45.

22 Id.

23 See, e.g., Municipal Court and Trac Ticket Information, CiTy of PAsAdenA, TexAs,http://www.ci.pasadena.tx.us/default.

aspx?name=courts(lastvisitedSept.8,2016)(outliningtherequirementthatpersonsagainstwhomwarrantshave

beenissuedand“wishingtopleadnotguiltywillberequiredtopostabondtosecureatrialdate.”).

24 Tex. Code Crim. ProC. Ann. art. 45.045.

25 Id. at art. 45.041.

26 Basedonauthors’interviewsandcourtobservations.

27 AnnuAl sTATisTiCAl rePorT, supra note 3, at Detail-48, 45.

09

Warrants Issued by Municipal and Justice Courts

in Fine-Only Misdemeanor Cases, 2015

Fine-Only

Misdemeanor

Warrants

Capias Pro Fine

Warrants in Fine-Only

Cases

Total Warrants in

Fine-Only Cases

Municipal Courts 1,738,385 688,328 2,426,713

Justice Courts 411,273 65,718 476,991

Total 2,149,658 754,046 2,903,704

Texas municipal and justice courts issued more than 2.9 million warrants in ne-only cases

in 2015. By contrast, the total number of warrants issued for Class A and B misdemeanors and

felonies during the same time period was approximately 129,000. This means more than 95 percent

of all arrest warrants issued in the state last year were for ne-only misdemeanor offenses.

One reason for the huge number of capias warrants is the underutilization of alternative

sentences. If a court determines that a defendant is unable to pay, it is required by law to consider

alternatives to immediate full payment, such as:

• Deferral of full payment.

• A payment plan.

• Community service.

• Full or partial waivers of nes and costs.

28

Unfortunately, despite the legal requirements, many courts do not offer these alternatives.

29

In

addition, courts that do offer payment plans or community service often make those options

inaccessible to many people, and very few courts waive a signicant amount of nes and costs

(as described below). Courts also make it difcult or impossible for people without proper

28 Tex. Code Crim. ProC. Ann. art. 45.0491; Tate v. Short, 401 U.S. 395 (1971).

29 See, e.g., Payment Plans, CArrollTon muniCiPAl CourT,http://www.cityofcarrollton.com/departments/departments-g-p/

municipal-court/payment-plans(lastvisitedSept.13,2016)(“CarrolltonMunicipalCourtdoesnotprovidepayment

plansforpayingjudgments(nes).Judgmentsmustbepaidonorbeforetheduedate.Non-paymentorinsucient

paymentwillresultinawarrantbeingissuedforyourarrest.”);Payment Plan Application, Wood CounTy,http://www.

mywoodcounty.com/users/0012/docs/Payment%20Plan.pdf(lastvisitedSept.13,2016)(“YouwillhaveONEMONTH

fromthedateoftheapplicationtopaytheremainderdueonyourne.TherewillbeNOEXTENSIONOFTIME

GRANTED.Don’taskforone.”)(emphasisinoriginal).

10

identication or adequate information about their income and expenses to qualify.

30

Many courts

also condition entering a payment plan on a large down payment.

31

For example, the Dallas

Municipal Court requires a 30 percent down payment up front, while the Burleson Municipal

Court requires a payment of “$125 or 20 percent, whichever is greater, for the initial payment at the

time of the request.”

32

The monthly payments ordered with payment plans may not be affordable either. In addition

to the various fees already covered, some courts require minimum payments of $100 or more a

month.

33

The Kyle Municipal Court and Dallas Municipal Court both require complete payment of

the assessed amount within three months, even on a payment plan.

34

Wood County offers only 30

days for payment and warns individuals not to call the court to ask for more time.

35

Courts vastly underutilize community service as an alternative to payment as well. For example,

the El Paso Municipal Court did not start offering community service options to adults until

after an exposé on the court’s illegal practices was published by BuzzFeed News.

36

Likewise, the

Amarillo Municipal Court only offers community service to juveniles.

37

Many other sizable cities

– including Richardson, Allen, Longview, Duncanville and Sherman – self-reported to the Ofce of

Court Administration that community service credit was not used to satisfy nes in a single case

30 See, e.g., Time Payment Plans, CiTy of Burleson, TexAs,https://burlesontx.com/555/Time-Payment-Plans(last

visitedSept.13,2016)(allowingonlystate-issueddriver’slicensesandidenticationcards);JudgeWayneL.Mack,

MontgomeryCountyJusticeCourtIndigencyApplication,available at http://www.mctx.org/courts/justices_of_the_

peace/justice_of_the_peace_pct_1/docs/Online_Payment_Plan_Docs.pdf(lastvisitedSept.13,2016)(allowingstate-

issueddriver’slicensesandidenticationcards,schoolidenticationcards,andbirthcerticates);Extension to Pay

Fine, CiTy of Keene, available at https://keenetx.com/departments/municipal-court(lastvisitedSept.13,2016)(allowing

onlystate-issueddriver’slicensesandidenticationcards).

31 See, e.g., Time Payment Plans, supra note 30 (notingthatpeopleapplyingforpaymentplansmust“[p]ay$125or20%,

whicheverisgreater,fortheinitialpaymentatthetimeofrequest”);FAQ for Extensions and Payment Plans, Wise CounTy,

http://www.co.wise.tx.us/jp1/payment_options.htm(lastvisitedSept.13,2016)(requiringa“signicantpayment”before

entering into a payment plan; Payment Plan Application, Wood CounTy, supranote29(dictatingthatdefendantsmust

payallcourtcostsattimeofapplication);Extension to Pay Fine, PlAno muniCiPAl CourT,https://www.plano.gov/367/

Extension-to-Pay-Fine (last visited Sept. 13, 2016) (screenshotonle,requiring$100downforeachticket).

32 Time Payment Plans, supra note 31; Court and Detention Services, CiTy of dAllAs, http://dallascityhall.com/

departments/courtdetentionservices/pages/payment-plan.aspx(lastvisitedSept.8,2016).

33 Payment Information, GrAnd PrAirie muniCiPAl CourT,http://www.gptx.org/city-government/city-departments/municipal-

court/payment-information(lastvisitedSept.13,2016)(listingminimummonthlypaymentamountsthatincreaseas

thetotalamountowedincreases);Payment Options, CiTy of irvinG,http://cityorving.org/329/Payment-Options(last

visitedSept.13,2016)(requiringaminimummonthlypaymentof$100).

34 Payment Plan, CiTy of dAllAs,http://dallascityhall.com/departments/courtdetentionservices/pages/payment-plan.aspx

(lastvisitedSept.14,2016)(allowingamaximumof90daystomakeallpayments);Fines/Court Costs, CiTy of Kyle,

http://www.cityofkyle.com/municipalcourt/nes-court-costs(lastvisitedSept.14,2016)(allowingamaximumofthree

monthstomakeallpayments).

35 Plea and Personal Data Form for Adavit of Indigency and/or Application for Payment of Courts Costs, Fines &

Fees, Wood CounTy JusTiCe of The PeACe CourT ComPliAnCe And ColleCTions, available athttp://www.mywoodcounty.com/

users/0012/docs/Payment%20Plan.pdf.

36 Kendall Taggart & Alex Campbell, Their Crime: Being Poor. Their Sentence: Jail., Buzzfeed(Oct.7,2015),available at

https://www.buzzfeed.com/kendalltaggart/in-texas-its-a-crime-to-be-poor?.

37 SecondAmendedClassActionComplaintat7,McKee v. Amarillo,No.2:16-cv-00009-J,page7(N.D.Tex.Apr.4,2016).

11

in 2015.

38

In fact, approximately 2 out of 5 Texas municipal courts reported zero cases resolved

through community service in 2015.

39

Another quarter of all municipal courts reported 10 or fewer

total cases resolved through community service during the entire year.

40

Statewide, community

service was only used to resolve nes and costs in 1.3 percent of all municipal and justice court

criminal cases in which nes or costs are typically assessed.

41

Courts that do offer community service options rarely publicize that on their websites or notices,

and the community service that is offered can be too onerous to complete.

42

People who are offered

community service are required by statute to be given at least $6.25 per hour credit, though in

some places $12.50 per hour credit is typical. Because of the low credit rate and high amounts

owed, people are often ordered to perform hundreds of hours of community service to resolve their

nes and costs. For many single parents and homeless people who accumulate tickets, performing

these hours can be a near-impossible task.

43

Courts’ nal option – waiver or reduction of nes due to indigency – is rarely used. Fines were

waived and reduced in less than 1 percent of all cases statewide in 2015. About 3 in 5 municipal

courts (i.e., 594 courts) reported zero waivers in 2015, meaning they did not elect to waive or reduce

nes or costs for indigency a single time over the course of a year.

38 AnnualStatisticalDetailReports,MunicipalCourts,AdditionalActivitybyCity,OceofCourtAdministration,FY2015,

available athttp://www.txcourts.gov/statistics/annual-statistical-reports/2015/.

39 Id.

40 Id.

41 Id. See also offiCe of CourT AdminisTrATion, AnnuAl sTATisTiCAl deTAil rePorTs, JusTiCe CourTs, AddiTionAl ACTiviTy By CounTy, fy

2015, available athttp://www.txcourts.gov/statistics/annual-statistical-reports/2015/.

42 See, e.g., Citation Disposition Options, CiTy of lAredo muniCiPAl CourT,http://www.cityoaredo.com/Municipal_Court/

Citation_Disposition.htm(lastvisitedSept.14,2016).Also,theCityofAustinregularlyoerscommunityservice.

However,whenitissuesawarrantforfailuretopay,thewarrantdoesnotmentioncommunityserviceasanoption.

Instead,itsimplystatesthatthepersonmustpaywhatisowedtoclearthewarrantandlistsdierentwaystheticket

canbepaid.

43 Complaint at 9, Harris v. City of Austin,No.A-15-CA-956-SS,2016U.S.Dist.LEXIS33694(W.D.Tex.2016).

CONTINUED ON NEXT PAGE >

12

Enforcement Programs

When someone has not paid a ticket, courts often try to enforce payment through one of the following programs.

DPS FAILURE TO APPEAR/FAILURE TO PAY PROGRAM

One common enforcement mechanism that municipal and justice courts utilize prohibits people from renewing

their driver’s licenses until nes are paid in full. Under the statutory “Failure to Appear/Failure to Pay” Program

administered by the Department of Public Safety (DPS), if a person misses a court date or a scheduled payment,

the court may suspend license renewal indenitely until all nes and costs are paid.

44

Once people are referred

to the Failure to Appear/Pay Program, they must resolve the total amount owed before the hold is lifted, meaning

that their license remains suspended even if they begin to successfully make payments according to a payment

plan. Over 230,000 Texans are currently unable to drive legally under the program and will not be able to renew

their licenses until they satisfy their tickets.

45

DRIVER RESPONSIBILITY PROGRAM

In addition to the Failure to Appear/Pay Program, the Texas Legislature created the Driver Responsibility Program

(DRP) in 2003 in an effort to generate additional revenue for the state from certain trafc offenses.

46

This program

allows DPS to charge additional surcharges to individuals for certain trafc offenses, independent of nes and

fees imposed by the court. When drivers fail to pay the surcharges, their licenses are automatically suspended.

47

Surcharges can be assessed in two ways: through a points system and through a convictions system.

48

Under the

DRP points-based system, drivers receive two points for a trafc violation and three points for a trafc violation

involving a crash. Once a driver receives six points (i.e., usually two or three tickets) in a three-year period, DPS

will assess a $100 surcharge annually for three years and an additional $25 for each additional point.

49

Under the

conviction-based system, surcharges apply automatically upon conviction of certain offenses. Some of these

offenses involve driving while intoxicated, but by far the most common offenses under this system are actually

driving with an invalid license, driving without a license and driving without insurance.

50

Surcharges for these low-

level offenses range from $100 to $250 annually.

51

44 Tex. TrAnsP. Code Ann. § 521.201(7)(8).

45 Email from Pamela Harden, supra note 2.

46 Tex. TrAnsP. Code Ann. § 708.

47 Id. at § 708.152.

48 Id. at § 708.053.

49 Id. at § 708.054.

50 Email from Pamela Harden, supra note 2. See alsoEmailfromPamelaHarden,Tex.Dep’t.ofPub.Safety,toJessica

Schleifer,LegislativeDirector,OceofTex.SenatorRodneyEllis(July21,2015).

51 Tex. TrAnsP. Code Ann. §§ 708.104, 708.103.

13

Unlike the Failure to Appear/Pay Program, the DRP does have an indigency program that grants relief to drivers at

or below 125 percent of the poverty guidelines.

52

But the application process is difcult to navigate and not widely

advertised, so most people do not know about it. Because nearly 1.4 million people have lost their licenses under

the DRP,

53

the DRP has come under scrutiny in recent years.

54

However, funds collected from the program are

directed toward trauma centers, making it politically challenging to amend or discontinue it.

SCOFFLAW PROGRAM

Counties and municipalities can also choose to participate in the “Scofaw Program.” This program, outlined in

the Transportation Code, allows a municipal or justice court to deny people the ability to apply for or renew motor

vehicle registrations with the county if they miss a court date or a scheduled payment.

55

As of September 2015,

there were 370,197 holds on vehicle registrations due to the Scofaw Program. Like the Failure to Appear/Pay

Program, the holds generally will not be lifted until all nes and costs are paid in full.

These enforcement mechanisms are particularly harmful for people who still need to drive. Without valid

registration, their vehicles are moving targets for police ofcers, and they are more likely to get pulled over,

perpetuating the cycle of debt.

C. WHAT ARE THE CONSEQUENCES OF LIVING WITH A WARRANT?

Individuals living with warrants are often fearful of going to court. They may also be reluctant to

call the police during an emergency or report a more serious crime out of fear of being arrested.

In addition, many employers will not hire somebody with an active warrant, even if it is for a

minor ticket such as a moving violation. One Houston mother the authors spoke with was making

$9 per hour at a call center, but had the opportunity to obtain a job at a big-box retailer earning

$14 per hour – a raise that would have helped her family tremendously. The potential employer

only required that she clear the ne-only arrest warrant related to nonpayment of nes for a

Parent Contributing to Nonattendance ticket that appeared during a background check. She could

not afford to clear the warrant, so she lost the better employment opportunity. As a result, she also

lost her housing, forcing her and her children to move in with a family member.

52 Tex. TrAnsP. Code Ann. § 708.158.

53 Email from Pamela Harden, supra note 2.

54 See, e.g.,EvaHershaw,Lawmakers Call for End to Controversial Driver Responsibility Program, Tex. TriBune (Apr. 30,

2015).

55 Tex. TrAnsP. Code Ann. §§ 502.010, 502.011, 702.003; sCofflAW CenTrAlized ColleCTions,https://texasscoaw.com/(last

visited Sept. 8, 2016).

14

Furthermore, people with arrest warrants who do not have identication cards, which are

necessary for many job applications, cannot go to the DPS to apply for one because of the

imminent risk of being arrested. These problems are exacerbated by the fact that people with

active warrants in ne-only cases are more likely to lose their jobs. They cannot drive to work

without running the risk of being arrested, and most low-income Texans do not live within a

reasonable public transit commute distance from local employers.

56

During warrant roundups,

jurisdictions publicize efforts to arrest people with warrants in ne-only cases. This includes

arresting individuals at their place of employment.

57

D. HOW DO TICKETS LEAD TO JAIL?

Every year, thousands of Texans are jailed because they are unable to pay ne-only misdemeanor

tickets. How is it that crimes that are only punishable by a ne lead to jail time?

When people are arrested on a warrant for a ne-only offense, they are typically booked into the

local county or city jail. After booking, the law requires that they be brought before a judge. In

Texas’ biggest cities, the amount of time waiting to see a judge can be as short as a few hours; in

some rural parts of the state, the wait may be as long as two days.

58

Upon seeing a judge, a number of things may happen. A judge can discuss the reasons for

nonpayment and release an individual, generally after revising their payment plan terms or

ordering that they complete an alternative sentence, like community service. However, some

judges will ask people how much money they have on them; if it is a signicant amount, they

will tell the person to pay that amount as a “bond” and appear at a later court date.

Judges may also order people to stay in jail as a way to pay their remaining nes and costs, often

referred to “laying out” or “sitting out” nes. People who are sentenced, or “committed,” to jail to

lay out nes and costs must be given credit towards the amount owed at a rate of $50 per night,

though judges in some courts routinely grant more dollar credit than this. By law, judges must

56 Texasgenerallylacksanadequatepublictransportationinfrastructure,eveninitsdenselypopulatedurbanareas.In

majorcitieslikeHouston,AustinandSanAntonio,fewerthan35percentofresidentslivewithina90-minutepublic

transportationrideofmostjobs.Asaresult,manylow-incomeTexanswholosetheirlicensesforfailingtopaytheir

nesorfeesmustcontinuetodriveinordertowork.See Adie Tomer, Where the Jobs Are: Employer Access to Labor

by Transit, The BrooKinGs insTiTuTe 9 (2012), available athttps://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/11-

transit-labor-tomer-full-paper.pdf.Inruralareas,publictransportationisevenlessavailable.

57 E.g., Warrant Roundup, The CiTy of Greenville, Tx, http://www.ci.greenville.tx.us/581/Warrant-Round-Up(lastvisitedSept.

8, 2016).

58 Tex. Code. Crim. ProC. Ann.art.45.045.Inthecaseofacapiaswarrant,thepersonmustbebroughtbeforeajudgewho

issuedthewarrantorajudgeinthesamecourtbytherstbusinessdayfollowingdefendant’sarrest,thoughsome

courtsconatethiswithatypicalmagistrationpursuanttoTex.CodeofCrim.Proc.Ann.art.15.17.Lengthofwaiting

timecitedisalsobasedontheauthors’interviewswithindividualswhowerejailedforne-onlyoenses.

15

determine that nonpayment was willful, meaning it was not due to inability to pay, before

committing people to more jail time. But in reality, this determination rarely happens.

59

Sometimes, by either local policy or mistake, people do not see a judge at all after they are arrested.

Instead, they are simply detained on the capias warrant until the nes and costs are paid off with

jail credit. In these cases, the capias warrant functions as a commitment order, even though the

law does not allow this.

60

Whether people are sentenced by a judge to lay out their nes or booked on a capias warrant

without ever seeing a judge, they often do not know how long they will be held in jail and must

rely on correctional ofcers to look up their release date on the jail’s computer system. This

even occurs when people are arrested on both ne-only offense warrants and on higher-level

misdemeanor charges. Defendants usually receive court-appointed defense attorneys for those

higher-level charges. But the defense attorneys often do not understand that their clients are

also being held on ne-only misdemeanor tickets. After a few days in jail, defense attorneys may

advise their clients to take a plea deal for time-served on the higher offense, assuring them that

they can get out that same day. Individuals will then call a friend or family member to come pick

them up, only to be told by a correctional ofcer hours later that they will in fact be held for days,

weeks, or months longer on their Class C nes.

61

1) HOW MANY PEOPLE GO TO JAIL FOR FINE-ONLY OFFENSES?

Based on data courts report annually to the Texas Ofce of Court Administration, nes in over

677,000 cases were satised through jail credit in 2015: 547,244 municipal court cases and 129,938

justice court cases.

62

This means that 1 in 8 municipal and justice court cases in which nes or

costs are typically assessed were resolved through jail credit. In comparison, less than 1 in 100 of

these cases are resolved through full or partial waiver of nes or costs.

63

However, jail credit numbers only tell part of the story of jailing practices for municipal and justice

courts.

64

We were able to collect data from a geographically diverse sample of seven populous

59 Theauthorshaverepresentedandinterviewedmanydefendantsjailedforne-onlyoensesacrossthestate,allof

whomwerejailedwithoutanabilitytopayhearing.

60 OneoftheauthorshasinterviewedpeopledetainedfordayswithoutseeingajudgeforticketsoutofBastropMunicipal

Court,JeersonCountyJusticeCourtandBeaumontMunicipalCourt.Oneofthosepeopletoldtheauthorthathehad

alreadyturnedhimselfinthepreviousmonthtositouthistickets;becausehedidnotseeajudgewhenhewasarrested

thesecondtime,hecouldnotexplainthathehadalreadysatisedhisticketdebtsinthepreviousmonth.

61 Basedonauthors’interviewsandcourtobservations.

62 AnnuAl sTATisTiCAl rePorT, supra note 3, at Detail 45, 48.

63 Id.

64 Id. First,numbersrepresentthenumberofcasesresolvedthroughjailcredit,notthenumberofindividualswhosatised

nesthroughjailcredit.Additionally,whenindividualsarearrested,theyarebookedinjailbasedonalloutstanding

oenses.Soanindividualwhoisarrestedforamoreseriousoense(likeaClassAorBmisdemeanor,orevenafelony)

maygetjailcreditforanyexistingne-onlywarrantswhileinjailforthemoreseriouscharges.Finally,thejailcredit

numbersdonotdistinguishbetweencasesinwhichpeopleweregivenjailcreditforthetimetheywaitedtoseeajudge,

andthosewhowereactuallysentencedbyajudgetojailfornotpayingtheirnes.

16

counties and to identify individuals booked in jail in those counties for ne-only offenses alone.

65

The results are an undercount of the individuals detained in these counties on ne-only offenses,

because they do not include those held on ne-only offenses who also had more serious charges.

Still, it is a helpful snapshot of the population of people detained on ne-only offenses in Texas.

People Booked into TExas Jails for Fine-Only Misdemeanors, 2014

66

County Population

Total Fine-Only Jail

Bookings

Fine-Only Bookings Per

1000 Citizens

El Paso 833,487 5,756 6.9

Hidalgo 831,073 922 1.1

Jefferson 252,235 5,399 21.4

Lubbock 293,974 365* 1.2

McLennan 243,441 2,924 12.0

Travis 1,151,145 7,170 6.2

Williamson 489,250 1,716 3.5

Total 4,094,605 24,252 5.9

* LUBBOCK COUNTY’S TOTAL JAIL BOOKINGS ONLY ACCOUNT FOR THOSE INDIVIDUALS WHO WERE

CATEGORIZED AS “LAYING OUT MUNICIPAL FINE” (I.E., SENTENCED TO JAIL BY THE MUNICIPAL COURT), SO NOT

ALL INDIVIDUALS WHO WERE BOOKED ON A FINE-ONLY WARRANT OR WARRANTLESS CLASS C ARREST ARE

NECESSARILY INCLUDED IN THIS NUMBER.

For 2014, the most recent year for which we have complete data, there were 24,252 individuals

booked into county jail in seven of Texas’ largest counties for ne-only offenses alone. These

counties represented 4.1 million people, about 15 percent of the total state population. Bookings

for ne-only offenses alone constituted anywhere from 2 percent to 50 percent of all jail bookings,

differing dramatically based on the jurisdiction.

65 Thesevencountieswereselectedbecauseoftheirpopulationaswellastheirabilitytoprovidehigh-quality,electronic

datafromwhichtheauthorscouldreadilyidentifythoseindividualsbookedintojailforne-onlyoenses.

66 AllofthedataanalysiscompletedforthisreportisonTexasAppleseed’swebsite,available atwww.texasappleseed.

org/pay-or-stay.

17

Municipal Jails

The county-level jail booking data does not include people held in city jails. In many counties, city police

departments operate jails that are completely separate from the county jail. These city jails house people booked

only on ne-only warrants from the city’s municipal court, as well as people charged with more serious offenses

who are awaiting transport to the county jail. Because city jails have no statewide oversight, it is difcult to

identify all of them.

We were, however, able to identify a number of city jails in Texas’ largest counties and request their booking

records for 2012 through mid-2015. For example, in 2013, there were 26,313 individuals held in the City of

Houston Jail and another 2,045 held in the McAllen City Jail for ne-only offenses alone. The existence of the

McAllen City Jail, located in Hidalgo County, to house people for ne-only offenses also helps to explain why

Hidalgo County’s jail bookings are lower than counties of similar size in the data we analyzed.

Other city jails to which we sent open records requests did not provide electronic data. For those jails, we have

estimates based on a manual count of individuals booked in a single month.

67

Jail

July Snapshot of

Fine-Only Bookings

Annual Estimate of

Fine-Only Bookings

Arlington City Jail 316 3,792 (2015)

Harlingen City Jail 59 708 (2014)

Euless City Jail 222 2,664 (2014)

North Richland Hills City Jail 86 1,032 (2014)

Total 683 8,196

These numbers suggest that in a single year, roughly 8,000 additional people were booked in these four city jails

for ne-only offenses, along with the roughly 28,000 booked in the Houston and McAllen city jails. Ultimately,

there are tens of thousands of people who are booked in city jails for ne-only offenses and not accounted for

in the county jail data.

67 Forthesecityjails,theauthorsreviewedthepaperorelectronicrecordsforJuly2014or2015(dependingonwhich

yearcitylawenforcementwasabletoprovide)andidentiedthoseindividualsduringthemonthofJulywhowere

bookedonne-onlyoensesalone.Inseveralcountyjails,Julywasthemonthwhenanaveragenumberofoenders

werebooked,whichiswhywechosethatmonth.TheauthorsthenmultipliedtheJulycountby12foraroughestimate

ofthenumberofpeoplethatparticularcityjailwasbookingonne-onlyoensesaloneannually.

18

2) HOW LONG DO PEOPLE STAY IN JAIL?

How long people stay in jail depends on the jurisdiction, as well as whether they are booked

and released after seeing a judge or sentenced by a judge to lay out their nes. The data show

that a majority of people who were booked in these seven county jails on a ne-only offense

were released within a day or less, meaning they were likely released after seeing a judge.

68

Nonetheless, there are thousands of people in these counties who remained in jail for much

longer than a day. In 2014, the most recent year for which we have complete data, there were

3,974 ne-only jail bookings lasting longer than two days across these seven counties alone.

Bookings Into Jail for Fine-only

Offenses lasting > 2 days, 2014

Number of Individuals

In Jail > 2 Days

Percent of Fine-Only Jail

Bookings >2 Days

El Paso 845 13.4%

Hidalgo 447 24.9%

Jefferson 1,759 25.8%

Lubbock 39 10.5%

McLennan 239 6.3%

Travis 221 2.3%

Williamson 424 23.5%

Total 3,974 11.4%

In addition, hundreds of people stayed for much lengthier periods of time for ne-only offenses.

For example, in 2014, there were 638 jail bookings in these seven counties lasting more than 10

continuous days in jail for ne-only offenses.

68 Seeadditionaldataavailableatwww.texasappleseed.org/pay-or-stay.

CONTINUED ON NEXT PAGE >

0

20

40

60

80

100

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

19

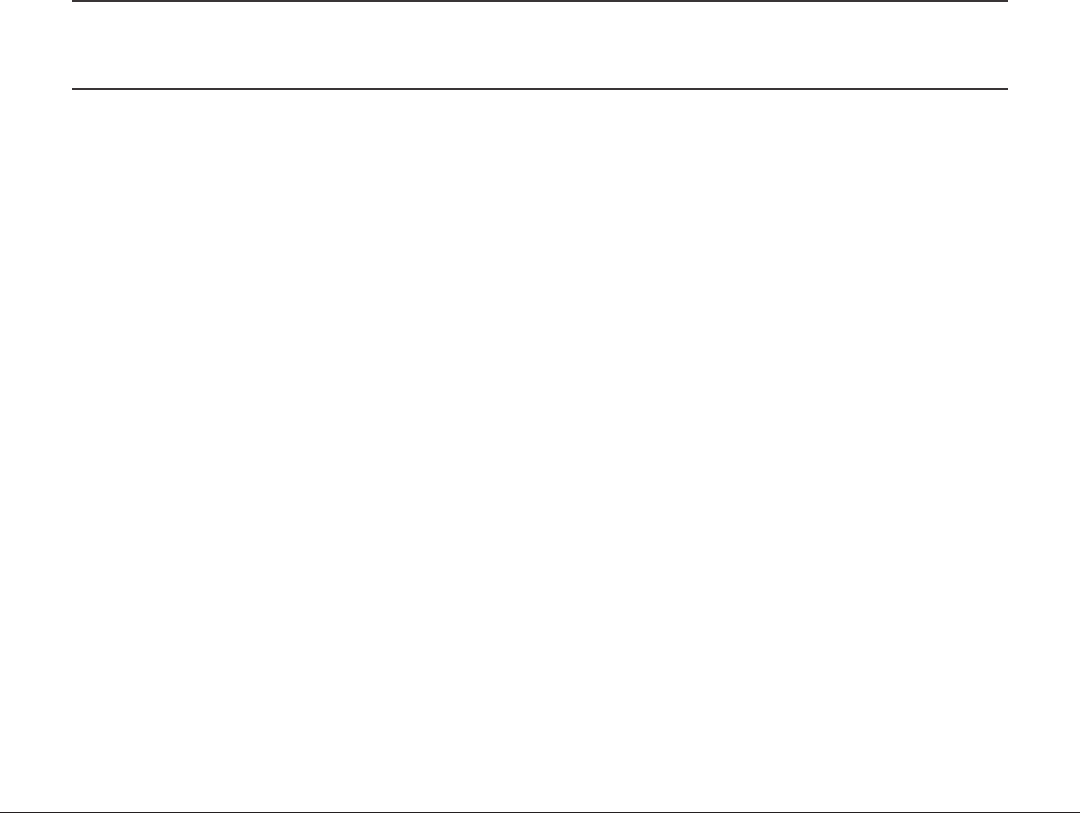

3) WHO GOES TO JAIL FOR FAILING TO PAY TICKETS?

It is often vulnerable people – including single parents with few economic resources, homeless

people, and people with unstable housing – who go to jail for ne-only offenses. In addition, a

disproportionate number of African Americans and a signicant number of women, juveniles and

elderly individuals are jailed for ne-only offenses.

African Americans are notably overrepresented in the ne-only jail bookings compared to their

representation in the general population. The following chart shows the percentage of people of

various races booked in 2014 in ve counties that provided data on the race of individuals booked

for ne-only offenses, followed in parentheses by the percentage of that race represented in the

county’s general population.

69

Fine-only Jail Bookings By Race, 2014

69 Notethatracewasnotrecordedforeveryoenderineachcounty.Thefollowingpercentagesarebasedonindividuals

forwhomracewasreported.Twoofthesevencountiesprovidednodataontheraceofindividualsbooked.

CONTINUED ON NEXT PAGE >

0

5

10

15

20

25

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

0

10

20

30

40

50

20

0

5

10

15

20

25

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

21

In the six of seven counties that provided data on gender, the people booked for ne-only charges

were more likely to be male than female, yet each county still jailed a signicant percentage of

women for these charges. This is consistent with national data showing a large increase in the

jailing of women in recent years for non-violent offenses.

70

Fine-only Jail Bookings By Gender, 2014

Male Female

El Paso 75.8% 24.2%

Hidalgo 85.7% 14.3%

Jefferson 72.5% 27.5%

Lubbock 60.0% 40.0%

Travis 78.1% 21.9%

Williamson 72.7% 27.3%

70 ElizabethSwavola,KristineRiley&RamSubramanian,Overlooked: Women and Jails in an Era of Reform, verA insTiTuTe

of JusTiCe, 6 (2016), available at https://storage.googleapis.com/vera-web-assets/downloads/Publications/overlooked-

women-and-jails-report/legacy_downloads/overlooked-women-in-jails-report-web.pdf.

0

5

10

15

20

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

22

Ashley Willis, AUSTIN

Willis was a 26-year-old single mother of a 6-year-old girl and a 4-month-old boy. Even though she worked full time,

she and her children lived below the poverty line and received food stamps.

In July of 2015, she was arrested for unpaid tickets while washing her car at the park. She had been making

sporadic payments on her tickets when she could. Even though she had not been able to complete the community

service she had been given, she was not aware she had warrants. She was frantic with worry about leaving her

children, but the arresting ofcers told her she would probably be released within 24 hours. They let her make

calls to set up temporary child care arrangements and tell her boss she would be missing a day of work.

They then took her to the Travis County Jail, where she saw a magistrate judge. Though she begged the judge to

release her on a payment plan so she could care for her children, he jailed her for 21 days for failing to complete

community service. Willis explained that her only option had been making payments when she could, because

caring for her children prevented her from doing community service.

Willis was then transferred to another Travis County facility in Del Valle. She was not given an opportunity to

make any calls, so she was unable to tell her boss she would be gone longer than expected or tell her landlord

she would be late with rent. She could not even nd out where her children were. Luckily, the Texas Fair Defense

Project was able to secure her release after only a week. If she had been kept the full 21 days, she would have lost

her job, her housing and possibly even her children.

Approximately two-thirds of jail bookings for ne-only offenses in the six counties that provided

age or date of birth data are individuals ranging in age from 18 to 35. Still, a wide range of ages is

represented. More than 200 individuals booked in adult county jails on ne-only offenses in these

seven counties in 2014 were 17 years old. This is particularly concerning given what the research

says about the dangers of 17-year-olds being held in adult jails, in terms of physical assault, sexual

assault and suicide risk.

71

These 17-year-olds are supposed to be housed separately from older

inmates, pursuant to the federal Prison Rape Elimination Act, but some Texas jails have failed to

comply with this law.

72

Additionally, almost 5 percent of individuals booked for ne-only offenses

(i.e., 1,146 individuals) were over age 55. This elderly population is also particularly vulnerable to

victimization by other inmates and more prone to suicide in jail.

73

71 See MicheleDeitch,et.al,Seventeen, Going on Eighteen: An Operational Fiscal Analysis of a Proposal to Raise the Age

of Juvenile Jurisdiction in Texas, Am. J. Crim. l., Vol. 40:1 at 13-14 (2012), available at http://ajclonline.org/wp-content/

uploads/2013/03/40-1-Deitch.pdf.

72 See St.JohnBarned-Smith,Stuck in Limbo: Feds Say Jails Need Separate Housing for Youngest Inmates, housTon

ChroniCle(Jul.1,2016).

73 SeeRobynnKuhlmann&RickRuddell,Elderly Jail Inmates: Problems, Prevalence, and Public Health, CAl. J. of heAlTh

PromoTion, Vol. 3:2 at 56-57 (2005) available at http://cjhp.fullerton.edu/Volume3_2005/Issue2/49-60-kuhlmann.pdf.

23

2014 Fine-Only Jail Bookings – By Age

<18 18-25 26-35 36-45 46-55 56-64 65+

El Paso 53 2,320 1,865 877 444 173 35

Percent of

bookings

0.9% 40.3% 32.4% 15.2% 7.7% 3.0% 0.6%

Jefferson 91 1,556 1,933 887 645 294 35

Percent of

bookings

1.7% 28.6% 35.5% 16.3% 11.9% 5.4% 0.6%

Lubbock 1 140 105 61 39 18 1

Percent of

bookings

0.3% 38.4% 28.8% 16.7% 10.7% 4.9% 0.3%

McLennan 12 968 997 555 309 90 17

Percent of

bookings

0.4% 32.8% 33.8% 18.8% 10.5% 3.1% 0.6%

Travis 17 2,269 2,270 1,257 971 372 56

Percent of

bookings

0.2% 31.6% 31.7% 17.5% 13.5% 5.2% 0.8%

Williamson 30 682 557 293 152 44 10

Percent of

bookings

1.7% 36.8% 32.4% 17.1% 8.8% 2.6% 0.6%

Total 204 7,885 7,727 3,930 2,560 991 154

Percent Total 0.9% 33.6% 32.9% 16.8% 10.9% 4.2% 0.7%

By reviewing the offenses that most often lead to jail booking, we nd further evidence that

low-income Texans are those most often jailed for ne-only offenses. In Hidalgo, Jefferson,

Lubbock, McLennan and Williamson Counties, over 25 percent of arrests for ne-only offenses

involved poverty-related trafc offenses, like driving on a suspended license or having an expired

inspection sticker. As discussed previously, lower income drivers commonly accumulate such

tickets after their inability to pay nes for a prior ticket causes them to receive holds on their

licenses and registrations. In Jefferson, McLennan, Lubbock and Williamson Counties, another

large percentage of people were arrested for missing their court date on a previous ne-only ticket.

The fact that these crimes are driving jail bookings is compelling evidence that people are being

booked in jail who are unable to pay nes.

CONTINUED ON NEXT PAGE >

24

Furthermore, those booked in jail for ne-only offenses are not usually chronic scofaws who

have accumulated large numbers of tickets. On average, people who were arrested and booked into

jail in the six counties that provided data did not have more than two ne-only charges pending

against them when they were booked.

Charges Represented IN Class C Jail Bookings, 2014

CONTINUED ON NEXT PAGE >

25

26

27

E. WHAT ARE THE CONSEQUENCES OF JAIL TIME?

Even when people are jailed for only a day or two, their lives can be completely upended. Arrest

and booking often occur unexpectedly because of a trafc stop, so people are not able to tell their

employers that they need to take time off. As a result, many lose their jobs while in jail, seriously

hindering their ability to earn a living. People’s cars are often impounded when they are arrested

during a trafc stop, requiring them to pay several hundred dollars to get their cars back; those

who cannot pay may lose their transportation. People in jail at the beginning of the month may

miss rent payments and face eviction by the time they are released. And the impact on children

can be profound when their primary caretaker is taken away for even a brief period. In some cases,

children of single parents may end up in foster care.

Jail stays also present health and safety concerns for people who are incarcerated. People

jailed for ne-only offenses may be housed alongside people who were arrested for more serious,

violent offenses; cases of violence against fellow inmates in jails are well documented.

74

Further,

even short jail stays can cause existing physical health conditions to worsen, particularly when

people do not have access to previously prescribed medications, and can exacerbate mental

health issues. All of these consequences point to the fact that jail should be reserved for those

individuals who pose a threat to public safety — not those whose only offense is failing to pay

a ne.

Lionel S. Edwards, GALVESTON

Lionel S. Edwards was arrested on Feb. 6, 2008, on warrants for three unpaid trafc tickets. He owed a total of

$1,209. During the booking process at the Galveston County Jail, he was found asleep on a cell oor. Jail staff

noted that Edwards seemed to have had a seizure. Their response was to provide him a mattress “to avoid any

injury should there be a recurrence of the seizure.” In the next hour and a half, an ofcer saw Edwards pacing,

moaning and moving from the mattress to the oor. Eventually, the ofcer noticed that he was not moving, and

asked an EMT to go into his cell to check on him. When the EMT got to the cell, Edwards had no pulse and was

not breathing. Jail staff called 911, but efforts to revive him were unsuccessful. Edwards was 23 years old.

75

74 JamesPinkerton&AnitaHassan,Inmate dies after Harris County jailhouse beating, housTon ChroniCle (Apr. 13, 2016).

75 TexasJusticeInitiative,JailCustodyDeathDataSet,available athttp://texasjusticeinitiative.org/jail-custody/(last

visitedJan.9,2017).

28

Daniel McDonald, Beaumont

Daniel McDonald (name altered for privacy) is a 23-year-old plumber from Beaumont who lived with his girlfriend

and their two daughters, a 4-year-old and a 3-month-old. McDonald had received several trafc tickets, including

many for driving without a license, which he could not obtain due to nancial holds. When McDonald went to court

to take care of his tickets, the judge refused to give him community service even though McDonald lived below the

poverty line. Instead, the judge put him on a payment plan for $50 a month.

McDonald managed to keep up with the payment plan for only three months before he fell behind. Capias

warrants were issued, and on Aug. 12, 2015, Williams was arrested. He was booked into the Jefferson County Jail

but did not see a judge. Nobody told him how long he would be in jail. His 4-year-old daughter’s very rst day of

school was on Aug. 24, and he had promised he would walk her to class. Williams was not released until Aug. 27.

His home was robbed while he was in jail, and he blamed himself for being gone.

MARK CONWAY, Waco

Mark Conway (name altered for privacy) started getting tickets when he was around 15 years old despite the

fact that he did not yet have a license, because he often drove his father around to prevent him from drinking and

driving. Conway is now 41. But because of his unpaid tickets for driving without a license, he is still unable to get

a driver’s license.

Conway received ve trafc tickets from Waco over a decade ago and has been to jail more than 20 times for

those tickets. He still owes thousands of dollars due to all the nes and fees that have compounded over time.

One ticket for driving without a license was set at $200 in 2003. It has since ballooned to over $700.

In September 2016, Conway found himself sitting in a holding cell for 36 hours before a judge informed him via

video that he would remain in jail for another month because of the unpaid tickets. The judge did not give Conway

a chance to speak. As a result, he could not tell the judge that he had gone to court to take care of his tickets

several times, only to be turned away because he could not make the required down payment of $200 per ticket

to get on a payment plan. Conway alsohad not been offered a chance to perform community service. At the time

of his arrest, his monthly income was less than $400, and he was still making back payments on child support for

his daughter, who has passed away.

Conway served 11 days in jail before attorneys from TFDP found him and secured his release. He lost his job

while he was in jail and is still looking for work.

29

A. Public Safety Implications

There is no public safety value in putting people in jail because they cannot afford to pay their

tickets. They are low-risk defendants whose underlying crime was intended to be punished by

only a ne.

In fact, jail time for low-risk individuals may actually increase the likelihood that they commit

future crimes. A study funded by the Houston-based Laura & John Arnold Foundation examined

outcomes of individuals held for short periods before trial in Kentucky jails. The study found

that low-risk defendants who were held at least two to three days were almost 40 percent more

likely to commit a new crime before trial than low-risk defendants held no more than twenty-four

hours.

76

The longer low-risk defendants were held, the more likely they were to reoffend.

77

One

possible explanation for this effect is the negative inuence of being housed in close quarters

with higher-risk offenders. Another explanation is the stress and alienation of losing housing,

employment and community ties through prolonged detention. Whatever the reason, research

demonstrates that jailing people for nothing more than failing to pay nes and fees actually harms

public safety.

78

Additionally, in most places, when a police ofcer makes an arrest, the ofcer must transport the

individual to the jail, wait while the individual is booked, and then travel back to the ofcer’s patrol

area — a process that can take several hours. Every hour that it takes for a police ofcer to stop,

arrest and book a person due to warrants for unpaid nes is time that ofcer is not devoting to

more serious public safety concerns. While trafc law enforcement is vitally important to public

safety, debt collection is not.

76 ChristopherT.Lowenkamp,Ph.D. et al., The Hidden Cost of Pretrial Detention,LJAF3(2013),available at http://www.

arnoldfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/LJAF_Report_hidden-costs_FNL.pdf.

77 Id.

78 Id.

03 costs of the

current system

30

B. Fiscal Implications

1) REVENUE FROM FINES AND FEES

Texas’ busiest criminal courts play a complicated role in the system, having been delegated two

inconsistent jobs. While they are tasked with keeping our streets safe, they also collect revenue

for state and local governments. The tension in the system does not go unnoticed by judges,

local administrators and law enforcement. People in these positions are often frustrated by the

expectation that they act as debt collectors.

Municipal and justice courts raise almost a billion dollars a year from the collection of nes and

court costs in ne-only cases. Data from the Ofce of Court Administration shows that Texas

municipal courts collected $696.5 million in nes and court costs in FY 2015. Of that, they remitted

$236 million to the state government.

79

Justice courts raise less revenue than municipal courts,

but they still raised $302.6 million in nes and court costs, remitting $96.8 million to the state.

80

Texas law prohibits any local government from requiring or suggesting to a justice or municipal

court judge that the judge is expected to collect a certain amount of money in a specic time

frame.

81

Nonetheless, many judges do feel pressure, whether direct or indirect, to raise revenue.

A presiding judge from a large Texas city who wished to remain anonymous indicated that she

faces this pressure. One city council member repeatedly threatened to replace her if she did not

meet projected revenue goals. In a widely reported story, a municipal court judge in the small town

of Calvert resigned over similar pressure. He publicly objected to the constant pressure from city

ofcials to collect on speeding tickets, calling the city’s municipal court a “cash cow.”

82

A recent

presentation by the Dallas assistant city manager to the Dallas City Council expressed concerns

about the Dallas Municipal Court’s “low collection rates.” The presentation highlighted Dallas’

“low revenue per case average” as compared to other similarly sized and neighboring cities.

83

Likewise, a report to the Fort Worth City Council by city auditors expressed concern that the city

was not “maximizing revenue potential” through its municipal court.

84

These presentations were

void of any discussion about the impact of court nes and costs on people who are unable to pay

and the goal of equal justice for all residents. They send a clear message that some city ofcials

care most about the bottom line.

79 AnnuAl sTATisTiCAl rePorT, supra note 3, at Detail-48.

80 Id. at Detail-45.

81 Tex. TrAnsP. Code Ann. § 720.002.

82 ByronHarris,Judge Says He Quit Over Speeding Ticket Quota, WfAA(June3,2015,2:28AM),available at http://

legacy.wfaa.com/story/news/local/investigates/2015/06/02/former-judge-says-he-quit-because-of-speeding-ticket-

quota/28367771/.

83 MemorandumfromtheCityofDallasonTheDallasMunicipalCourtSystem:AnOverview59(July27,2012),available

at http://www3.dallascityhall.com/council_Briengs/Briengs0812/DallasMunicipalCourtSystemOverview_080112.pdf.

84 City of Fort Worth Department of Internal Audit,: Municipal Court Cash Collections and Non-Cash Ticket Dispositions

Audit (2014), available at http://fortworthtexas.gov/uploadedFiles/Internal_Audit/141219-municipalcourtaudit.pdf.

31

Additional pressure to generate revenue comes from state government. The State of Texas

received $333 million in court costs stemming from ne-only offenses in 2015. Though in

theory these costs go to reimburse the government for the cost of prosecuting the tickets, “court

administrators speculate that 1 in every 3 dollars gets diverted towards projects that have nothing

to do with the court system.”

85

Nearly every legislative session, state representatives add or try to

add additional court costs to fund various programs.

When the goal of raising revenue becomes a court’s priority, justice suffers. Courts that prioritize

generating revenue have little incentive to order community service or other alternatives that

provide no money to the government, and may avoid waiving or reducing nes and costs in

appropriate cases. On the other hand, they do have an incentive to impose additional fees on

defendants and to encourage the ling of additional charges when defendants fail to appear so

that more nes are collected. Courts may also see the threat of jail as a useful tool to encourage

payment.

2) COSTS TO TAXPAYERS

Any nancial benet of current practices must be weighed against the costs those practices

impose, both on governments and individuals. Right now, the collection of nes places a hefty

burden on local police departments and sheriffs’ departments to use their resources to locate,

arrest and jail those who do not – and in many cases cannot – pay nes. This shift of law

enforcement resources away from more serious crimes can have a negative effect on public safety,

while taxpayers foot the bill for unnecessary jail stays.

Additionally, the proliferation of arrest warrants and tens of thousands of jail stays leads to a loss

of employment and employment opportunities, which both stunts the economy and drives more

people to rely on public benets to survive.

85 EricDexheimer,Hard-up Defendants Pay as State Siphons Court Fees for Unrelated Uses, AusTin-Am. sTATesmAn (Mar. 3,

2012).

32

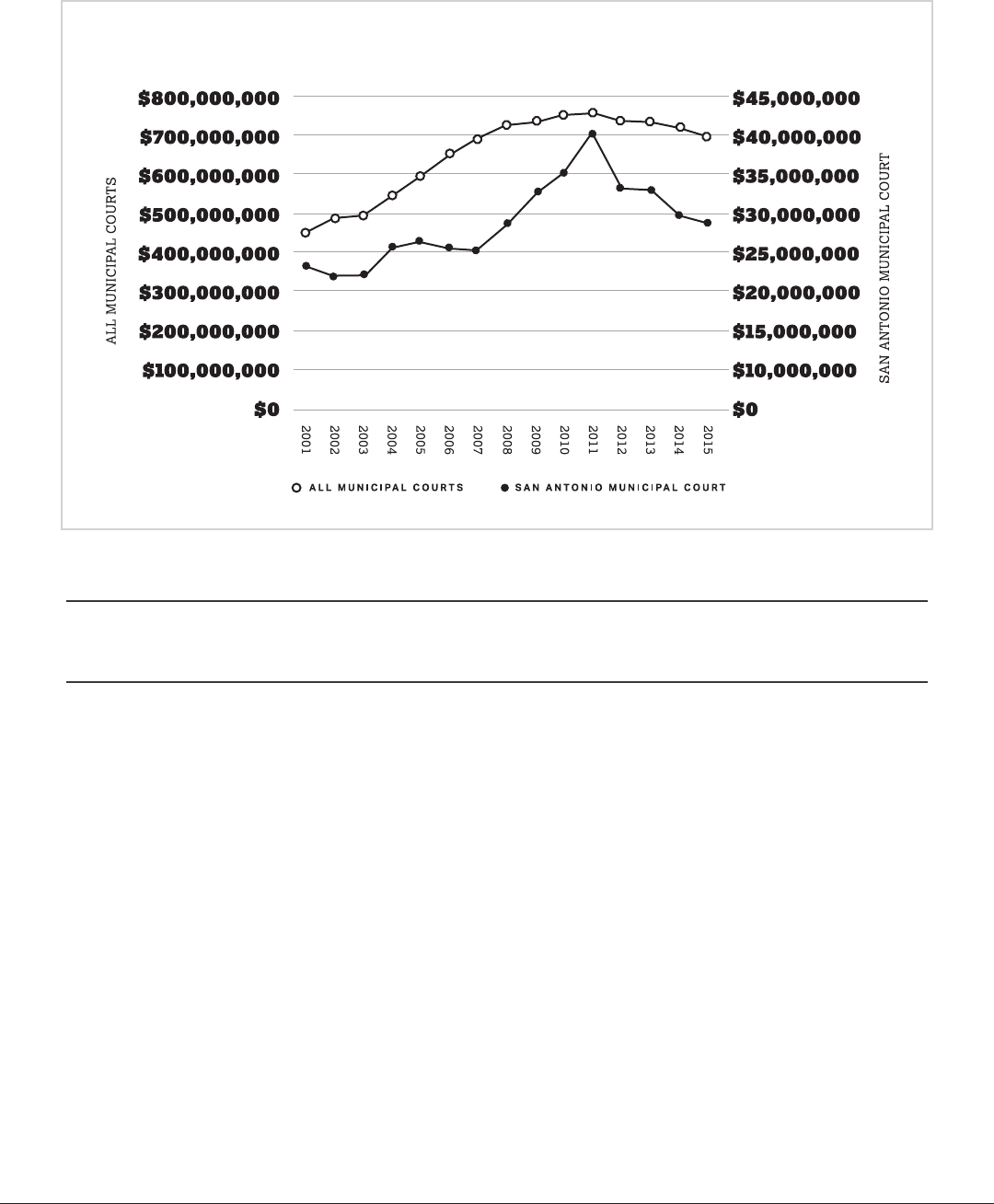

C. A Better, More Cost-Effective Way

The City of San Antonio’s decade-long experiment with ending jail commitments for nonpayment

demonstrates that jail commitments are not necessary to collect revenue. In 2007, Bexar County

faced a major overcrowding problem in its jail. San Antonio’s Presiding Municipal Court Judge

John Bull, along with county and city ofcials, decided that the San Antonio Municipal Court

would stop sentencing people to sit out their unpaid nes in jail for ne-only offenses in order

to address the overcrowding problem.

86

Almost a decade later, the San Antonio Municipal Court

continues to follow this policy.

87

Not only has San Antonio’s approach saved money through the avoided jail stays, it has not

reduced the court’s revenue – a strong indicator of compliance with its judgments. Rather,

as shown in the chart on the next page, the city’s greatest increase in revenue occurred in the

years immediately following the decision to end jail commitments. Four years after ending jail

commitments, San Antonio Municipal Court revenue was up 74 percent. This increase partly

tracks a statewide trend of increasing revenue and increasing amounts collected per case due to

escalating court costs. But statewide revenue did not increase nearly as much during the period;

it went up only 10 percent in that time. Asked about the increase, Judge Bull hypothesized that

taking away jail as a sentencing option encouraged judges to work more closely with defendants

to develop individualized sentences that they were able to complete.

“Before 2007, jail had been an easy, even if counterproductive, alternative for judges who

were dealing with defendants who struggled to pay their fines. When jail was no longer

an option, more judges began making a concerted effort to use the alternative sentences

available to them to resolve cases – alternatives like payment plans, partial payment

and community service. And at least partly as a result of this, revenue shot up.”

88

— Hon. John Bull, Presiding Judge, San Antonio Municipal Court

86 Ulloa, supra note 6.

87 SeeMunicipalCourtBriengontheU.S.DepartmentofJustice’sLettertoCourts,PresentedbyHon.JohnBull,

PresidingJudge,totheCriminalJustice,PublicSafetyandServicesCommitteeoftheSanAntonioCityCouncil,File

No. 16-2898 (May 4, 2016), available at https://sanantonio.legistar.com/Calendar.aspx.

88 InterviewwithHonorableJohnBull,PresidingJudge,SanAntonioMunicipalCourt,Jul.1,2016.

33

TOTAL REVENUE COLLECTED, 2001–2015

D. Legal Costs & Implications

Although the U.S. Supreme Court held over 40 years ago that jailing a person for inability to pay

a misdemeanor ne is unconstitutional, courts throughout Texas continue to jail people who are

unable to pay the nes and accumulated fees. So long as Texas courts continue to violate the clear,

long-standing constitutional rights of defendants, the local governments, local ofcials and judges

will continue to face the threat of litigation and all the costs associated with it.

In 1970, the Supreme Court held in Williams v. Illinois that an individual’s prison sentence could

not be extended as payment for the ne that is owed.

89

The court reasoned that incarcerating

people who cannot afford to pay nes and fees “exposes only indigent defendants to the risk of

imprisonment beyond the statutory maximum,” amounting to “an impermissible discrimination”

against poor people.

90

One year later, in Tate v. Short,

91

the Court heard a case in which an indigent man owed money to

the Houston Municipal Court for trafc tickets. Unable to pay the tickets, Preston Tate had been

conned to a municipal prison farm and made to work off his trafc nes at a rate of $5 a day.

89 Williams v. Ill., 399 U.S. 235, 239 (1970).

90 Williams, 399 U.S. at 242.

91 Tate v. Short, 401 U.S. 395 (1971).

34

Relying on its reasoning in Williams, the court held that Tate’s “imprisonment for nonpayment

constitutes precisely the same unconstitutional discrimination since, like Williams, [Tate] was

subjected to imprisonment solely because of his indigency.”

92

The court made it clear that indigent

people must be offered alternatives to payment in full or imprisonment, such as payment plans,

community service, and the reduction of nes and fees.

93

In 1983, the Court held in Bearden v. Georgia that courts could not revoke probation or parole solely

because a person could not afford to pay nes and costs.

94

The court claried that due process

required that the court inquire into a person’s reasons for not paying the ne or fee before any

imprisonment.

95

While Tate was pending at the U.S. Supreme Court, the Texas Legislature made changes to state

law so that when the case was remanded back to state court, Texas statute would comply with

the requirements of the U.S. Constitution.

96

The Texas Code of Criminal Procedure now allows

municipal and justice courts to jail people who fail to pay nes and costs, but only after the judge

holds a hearing and makes a written determination that either:

• The person is not indigent and failed to make a good faith effort to discharge the nes

and costs.

• The person is indigent, failed to complete community service, and was able to perform

the ordered community service without undue hardship.

97

Despite the clear Supreme Court precedent and unequivocal state law requirement that a written

determination be made, some courts are not following the law. For example, the authors reviewed

the case les of 50 individuals who had been committed to jail by the Houston Municipal Court

and did not nd a single written determination that any individual was able to pay their nes prior

to jail commitment. At least half of these individuals had addresses listed as “homeless” in court

records — compelling evidence that they should have been found unable to pay their nes had an

ability to pay hearing actually been conducted. Similarly, reporters from BuzzFeed reviewed 100

case les from the El Paso Municipal Court and did not nd a written determination in any of

92 Id. at 397-98.

93 Id. at 399-400.

94 Bearden v. Georgia, 461 U.S. 660, 661 (1982).

95 Id. at 668. See also LetterfromVanitaGupta,PrincipalDeputyAssistantAtt’yGen.,CivilRightsDivision&LisaFoster,

Director,OceforAccesstoJustice,U.S.Dept.ofJustice,Mar.14,2016,available at https://www.justice.gov/crt/

le/832461/download(explainingthat“tocomplywith[Bearden’s]constitutionalguarantee,stateandlocalcourtsmust

inquireastoaperson’sabilitytopaypriortoimposingincarcerationfornonpayment”)[hereinafter“DOJDearColleague

Letter”].

96 Tex. Code of Crim. ProC.art.45.046,asamendedbyActs1971,62ndLeg.,p.2991,ch.987,Sec.7,e.June15,1971.

97 Tex. Code Crim. ProC. Ann. art. 45.046(a).

35

them.

98

In fact, in their review of les in 20 Texas municipal and justice courts, the reporters found

that nine courts lacked documentation of ability to pay hearings.

99

Texas courts’ current practice of jailing people for failure to pay nes in ne-only cases

violates another constitutional right as well – the right to counsel pursuant to the Sixth and

14th Amendments of the U.S. Constitution. Although municipal and justice courts in Texas do

jail people for failure to pay nes and costs, these courts do not provide defendants with the

opportunity to request appointment of defense counsel in ne-only cases. In fact, the authors of

this report know of no court in Texas that provides appointed counsel to individuals in ne-only

cases. Yet, in Argersinger v. Hamlin, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that indigent defendants cannot

be imprisoned for any criminal offense unless they have been provided with the opportunity

to have counsel appointed at the trial stage of their case.

100

If Texas courts are going to jail

individuals, the Constitution requires that counsel be appointed to defendants who cannot afford