WASHINGTON NATURAL HERITAGE PROGRAM

Southwestern Washington

Prairies: using GIS to find

rare plant habitat in

historic prairies

Prepared for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife

Service Region 1, Section 6 funding

Prepared by

Florence Caplow and Janice Miller

December 2004

Natural Heritage

Report 2004-02

Southwestern Washington Prairies:

using GIS to find remnant prairies and

rare plant habitat

Prepared by

Florence Caplow

Janice Miller

Washington Natural Heritage Program

Department of Natural Resources

Olympia, Washington

December 2004

Prepared for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

through Endangered Species Act Section 6 funding

Grant Agreement E-2, Segment 35

Executive Summary

More than 99% of the grasslands of southwestern Washington (Clark, Lewis, and Cowlitz

Counties) have been converted to agriculture and other uses. Remnant grasslands of

southwestern Washington support, or did support, four federally listed species and two

federal Species of Concern: Nelson's checker-mallow (Sidalcea nelsoniana), Bradshaw's

lomatium (Lomatium bradshawii), Kincaid's lupine (Lupinus sulphureus ssp. kincaidii),

golden paintbrush (Castilleja levisecta), pale larkspur (Delphinium leucophaeum), and

thin-leaved peavine (Lathyrus holochlorus). These grassland areas (“prairies”) also

support 12 other species of plants that are considered rare in Washington State.

GIS analysis for inventory and possible re-introduction sites was done using available

GIS data layers: soils data derived from the Private Forest Land Grading system (PFLG),

USGS GNIS names containing "prairie" or "plain", the oak/grasslands layer developed by

Chris Chappell of WNHP, elevation (below 1500 feet), georeferenced General Land

Office (GLO) TIFF files of historical survey cadastral surveys, and digitized delineated

prairie areas from the cadastral survey maps.

The identified prairie areas were used as a basis for reconnaissance fieldwork in the

summer of 2004. We performed an initial reconnaissance in thirty-two separate prairie

areas in Lewis, Cowlitz, and Clark counties. Bicycle surveys were used in portions of the

area. Nine prairies supported no visible native prairie vegetation. Twenty-three prairies

had at least some remnant prairie species, generally along the roadsides. Ten populations

of five rare species were found in the course of the survey, including two new

populations of Kincaid’s lupine. Most of the populations were found on roadsides or

along fencerows.

In addition, the maps produced through GIS analysis were used to identify potential

habitat for rare grassland butterflies (results not included in this report), and will be used

in 2005 and 2006 as a basis for further rare plant inventory.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Chris Chappell, plant ecologist for the WNHP, participated in the project development,

visited the Lewis and Clark prairie, and provided a very helpful review of the report.

Nathan Reynolds of Washington State University demonstrated this particular GIS

methodology, which he has used in his research on historical prairies in Clark County.

Ann Potter and Robin Woodin, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, helped to

field-check maps and orient me to Lewis County. Rachael Holler and Rebecca Rothwell

volunteered in the field, and Peter Morrison of Pacific Biodiversity Institute, Phil Gaddis

of Clark County, and Keith Karoly of Reed College provided valuable leads. All of your

efforts are appreciated!

Table of Contents

1. INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................... 1

2. MAP DEVELOPMENT AND FIELD METHODS............................................... 2

2.1. DEVELOPMENT OF GIS MAPS............................................................................... 2

2.2. DRIVING RECONNAISSANCE ................................................................................. 4

2.3. SURVEY BY BICYCLE............................................................................................ 5

2.4. OTHER SURVEYS .................................................................................................. 5

3. RESULTS OF FIELDWORK ................................................................................. 5

3.1. IDENTIFICATION OF EXTANT PRAIRIE REMNANTS ................................................. 5

3.2. HISTORICAL PRAIRIES WITH REMNANT PRAIRIE SPECIES ...................................... 8

3.2.1. Lewis and Clark State Park, Lewis County ................................................ 8

3.2.2. Lacamas and Cowlitz Prairies, Lewis County............................................ 8

3.2.3. Drews Prairie, Lewis County...................................................................... 9

3.2.4. Lacamas Prairie, Clark County................................................................ 10

3.2.5. Boistfort Prairie, Lewis County................................................................ 11

3.2.6. Halfway Creek Meadows, Lewis County.................................................. 12

3.2.7. Jackson Prairie, Lewis County ................................................................. 12

3.3. RARE PLANTS FOUND IN 2004 SURVEYS............................................................. 13

3.3.1. Kincaid’s lupine........................................................................................ 13

3.3.2. Bolander’s peavine ................................................................................... 14

3.3.3. Thin-leaved peavine.................................................................................. 14

3.3.4. Checker-mallow........................................................................................ 15

3.3.5. Great polemonium .................................................................................... 15

4. APPLICATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS............................................... 15

4.1. APPLICATIONS ................................................................................................... 15

4.2. ADDITIONAL SURVEYS....................................................................................... 16

4.3. SIGNIFICANCE OF FINDINGS AND CONSERVATION RECOMMENDATIONS.............. 16

5. REFERENCES........................................................................................................ 17

i

List of Tables

Table 1. Potential rare plant species of prairies …………… 2

Table 2. Data sets used for GIS project …………………… 3

Table 3. Prairies of Southwestern Washington. …………… 6

Table 4. Rare plant populations found in 2004 ……………. 13

List of Figures

Figure 1. Study area ………………………………………… 2

Figure 2. A prairie area on a GLO Cadastral Survey Map …. 3

Figure 3. An example of a township field map …………….. 4

Figure 4. Prairie map of Lewis County *……...........…link to 1.7 mB pdf

Figure 5. Prairie map of Clark and Cowlitz counties *. link to 1.7 mB pdf

*

Figures 4 and 5 are also available as pdf documents on cd. If interested, contact WNHP.

ii

1. INTRODUCTION

“Prairies,” i.e., native grasslands on gentle topography and deep soils, are a little-known

component of the pre-settlement vegetation of western Washington and Oregon. These

grasslands were underlain by a variety of soil types, from the hydric soils in the wet

prairies of the Willamette Valley and Clark County to the very gravelly soils in the

southern Puget Sound area. They were historically maintained by frequent fires ignited

by Native Americans (Norton 1979). Native grasslands are imperiled ecosystems in

western Washington and have declined to less than 3% of the their pre-settlement extent

(Crawford and Hall 1997, Chappell et al. 2001).

Earlier studies of native grasslands of southwestern Washington, in Clark, Cowlitz, and

Lewis counties, found fairly large areas of prairie soil, but no extant untilled grasslands

larger than five acres (Chappell et al. 2001). This suggests a greater than 99% loss of

native grasslands (prairies) in southwestern Washington. The soils of southwestern

Washington prairies range from wetland soil types to deep, well-drained soils, but

gravelly soils are uncommon. This contributed to their early conversion to agricultural

use.

There is, however, a strong correlation between historical prairies and historical or

current rare plant populations. Remnant grasslands of southwestern Washington support,

or historically supported, four federally listed species: Nelson's checker-mallow (Sidalcea

nelsoniana), Bradshaw's lomatium (Lomatium bradshawii), Kincaid's lupine (Lupinus

sulphureus ssp. kincaidii), and golden paintbrush (Castilleja levisecta), and two federal

Species of Concern: pale larkspur (Delphinium leucophaeum) and thin-leaved peavine

(Lathyrus holochlorus). These prairies also support or did support 12 other species of

plants that are considered rare in Washington State, most of which are state Threatened or

Endangered (Table 1).

In many cases, there are only one or two extant populations known for these very rare

species, and many of the populations are on private land, along roadsides, or are too small

to be viable. Several are disjunct by more than 100 miles from the nearest known

population, and so may preserve unique alleles or other genetic differences from the main

range of the species. Finding more populations, viable or not, can help bolster the

populations that we have.

This project was undertaken by the Washington Natural Heritage Program (WNHP), with

Section 6 funding from Region 1 of the USFWS. The intention of this project was to

develop a GIS based map of historical prairies for southwestern Washington, and then to

perform a reconnaissance to test the predictive power of the various map layers used in

the project. If the reconnaissance showed that the map layers were useful for predicting

either remnant prairie vegetation or rare plant populations, then the maps could be used

within WNHP and by other agencies to identify potential rare plant habitat, potential

restoration areas, potential rare butterfly habitat, and other uses.

1

Table 1. Potential rare plant species of Lewis/Cowlitz/Clark County Prairies

Species common name Bloom time State/fed status

Aster curtus white-topped aster late S

Aster hallii Hall’s aster late T

Balsamorhiza deltoidea Puget balsamroot mid R1

Cardamine penduliflora Willamette Valley bittercress early T

Castilleja levisecta golden paintbrush mid E/T

Delphinium leucophaeum pale larkspur mid E/SC

Eryngium petiolatum Oregon coyote thistle late T

Lathryus holochlorus thin leaved peavine mid E/SC

Lathryus vestitus ssp. bolanderi Bolander’s pea mid E

Lomatium bradshawii Bradshaw’s lomatium early E/E

Lupinus suphureus ssp. kincaidii Kincaid’s lupine mid E/T

Polemonium carneum Great polemonium late T

Perideridia oregana Oregon yampah late R1

Scutellaria antirrhinoides Snap-dragon skullcap ? X

Sidalcea hirtipes hairy-stemmed checker-mallow mid E

Sidalcea malviflora var. virgata rose checker mallow mid E

Sidalcea nelsoniana Nelson’s checker-mallow mid E/E

2. MAP DEVELOPMENT AND FIELD METHODS

2.1. Development of GIS maps

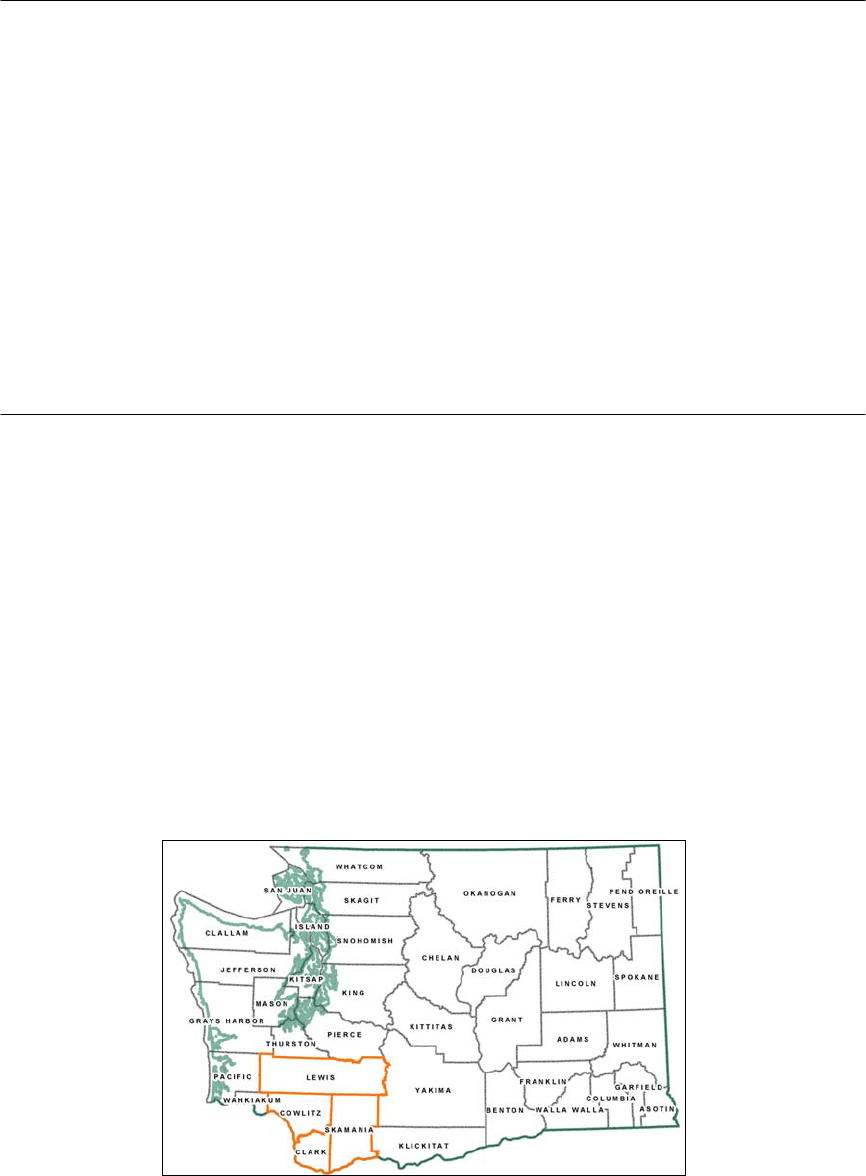

Lewis, Cowlitz, and Clark counties, and very small portions of Thurston County and

Skamania County were the boundaries of the study area (Figure 1). The study area was

further refined by selecting 1) appropriate soil types from DNR soils data, 2) elevations

less than 1500 feet and under from USGS 10-Meter DEM data, and 3) GNIS prairie

names. This resulted in 25 target townships.

Figure. 1. Study area (in orange)

2

The next step was to digitize prairie areas from GLO Cadastral Survey maps that were

drawn in the late 1800s. These are available online (

http://landprx.pdxproxy.blm.gov/).

An example of a prairie area on the GLO Cadastral Survey maps is shown in Figure 2.

The maps were georeferenced using DNR’s cadastral survey data and “georeference”

tools in ArcGIS ArcMap.

Figure 2. A prairie area on a GLO Cadastral Survey Map

For Clark County we utilized shapefiles

provided by Douglas Wilson, the

archaeologist for the Vancouver

National Historical Reserve. These are

digitized boundaries of prairies and open

wetlands from GLO Cadastral maps (see

above). The layers were digitized as

part of the Clark County archaeological

predictive model project (Ellis and

Wilson 1995; Updated by Wilson 2001)

which the County converted to

Washington State Plane South, NAD 83.

Table 2. Data sets used for GIS project to identify historical prairie areas

Historical prairie areas identified on:

Cadastral survey maps showing prairies or open wetlands

GNIS place names containing ‘prairie’ or ‘plain’

Prairie soil series

Doty

Mossyrock

Nisqually

Sifton

Spanaway

Winlock

1500 feet maximum elevation, using USGS DEM data

Existing vegetation layer:

Oak/Grasslands layer developed by Chris Chappell of WNHP

3

The prairie soils layer was assembled from those soil series reported in the county soil

surveys to have historically supported grassy vegetation (Fowler and Ness 1954, McGee

1972, Call 1974). These did not include wetland prairies which were not well

documented in the soil surveys.

The final maps for field use included prairie soils layers, GNIS prairie names, prairies

(and historical mapped open wetlands in Clark County) identified on GLO Cadastral

Survey maps, an oak/grassland layer developed by WNHP (Chappell et al. 1999), major

and minor highways and roads, active and abandoned railroads, Natural Heritage Element

Occurrence data, and Major Public Lands ownership. The most relevant layers for

predicting historical prairies are in Table 2.

The maps were printed in color at one township per 11” X 14” page. This was an ideal

size for fieldwork (Figure 3). Although some orthophotos were printed, they were not

particularly helpful in the identification of remnant prairie vegetation, since pastures

dominated by non-native grasses and remnant prairie could not be differentiated on the

orthophotos.

2.2. Driving reconnaissance

Figure 3. An example of a township field map

We took the GIS maps into the

field in 2004 and checked for

remnant prairie species, through

driving and examining roadside

vegetation and adjacent fields.

Two people were needed: one to

drive and one to scan the roadside

and fields. Binoculars and spotting

scope were also used. When

remnant vegetation was seen, we

stopped and examined the roadside

more carefully.

The reconnaissance was focused in

areas that were identified as

potential historical prairie, but

included other areas between as well. There were two reconnaissance periods: one in late

April through early May, and one in late May through early June.

The early season reconnaissance (late April and early May) was focused on camas

(Camassia spp.) as an indicator of remnant prairie vegetation. The bright blue color of

camas and its capacity to withstand considerable disturbance and grazing make it a good

4

indicator of the potential for other prairie species. This assumption was born out by the

2004 fieldwork.

The later season (mid May through mid June) reconnaissance was focused on the

possible rare species, most of which, with the exception of Cardamine penduliflora and

Lomatium bradshawii, bloom later in the season. Delphinium nuttallii was also a good

indicator for other prairie species during the later season reconnaissance, due to its bright

blue color, tolerance for disturbance, and relatively tall growth form.

We drove over 224 miles during the driving reconnaissance, most of which was focused

on Lewis County. Figures 9 and 10 show driving reconnaissance routes.

2.3. Survey by bicycle

In considering the logistical aspects of this project, we felt that a bicycle might be an

ideal tool for more detailed survey work. Many county roads have limited shoulders for

parking, and driving speeds are too fast to identify more than the most obvious species.

Bicyclists also draw little attention in rural areas, while idling vehicles can be cause for

concern.

Bicycle reconnaissance was very successful. Potentially significant prairie areas were

identified during the driving reconnaissance. We then transported bicycles to the area

and rode as a team of two along roads in the area. Approximately 10 miles were ridden

and surveyed in this way, and several rare plant populations were found through bicycle

surveys.

2.4. Other surveys

Although the 2004 fieldwork was focused on reconnaissance and experimentation with

road-based field methods, there were a few opportunities to work on foot on public lands

and private lands when there was some willingness from the landowner. Lewis and Clark

State Park, Matilda Jackson County Park, and two parcels west of Boistfort were

surveyed for rare species on foot. We found rare plant populations through walking

surveys as well, and hope to expand this method in 2005 and 2006, especially on private

lands with willing landowners.

3. RESULTS OF FIELDWORK

3.1. Identification of extant prairie remnants

Sixty-six areas of prairie soil and/or mapped historical prairie were identified through

GIS within the study area (Table 3 and Figures 9 and 10), totaling 46,531 acres.

5

Prairie

Township Range County Date Date #2

Bike

date Rare species Return? Comments

Adna Prairie 13N 3W Lewis 5/17 No All agriculture

Alpha Prairies 13N 1E Lewis 4/26 Moderate Some Thermopsis

Battle ground wetlands 4N 2E Clark

Bear Prairie 2N 5E Clark 5/5 High Thermopsis. Looks like a good place for Sidalcea

Beaver Creek Prairie 13N 4W Lewis 5/17 No Not much there

Berwick Creek Prairie 13N 2W Lewis 4/26 Moderate Prairie, oaks, snowberry

Boistfort Prairie 12N 4W Lewis 5/17 6/2

Kincaid's lupine,

thin leaved

peavine, pale

larkspur High Many rare species

Brush Prairie 3N 2E Clark

Bunker Creek Prairie 13N 3W Lewis 5/17 No All agriculture

Burnt Ridge Road Prairies 13N 1E Lewis

Calvin Road Prairie 13N 2E Lewis

Camp Bonneville 2N 3E Clark

Centralia Prairie 14N 2W Lewis

Ceres Hill Road Prairie 13N 4W Lewis 5/17 Moderate Lots of manroot

Chehalis Prairie 14N 2W Lewis

Chelatchie Prairie 5N 4E Clark

Cinebar Prairie 13N 2E Lewis

Claquato Prairie 13N 3W Lewis

Cowlitz Prairie 12N 1W Lewis 4/29 5/21 High Camas, also balsamroot and camas at east end

Cowlitz River Prairie 12N 1E Lewis 5/21 Bolander's peavine Moderate

Peavine and other dry forest species, no prairie species

seen…more by bike perhaps.

Curtis Prairie 13N 4W Lewis 5/17 High Not really looked at. Manroot and camas north of Curtis

Doty Prairie 13N 5W Lewis

Doty Prairie 13N 5W Lewis

Drews Prairie 11N 2W Lewis 5/18 6/3

Kincaid's lupine,

hairy stemmed

checkermallow

High if can

access land Camas, delphinium, oregon ash, wet prairie

Fern Hill Prairie 13N 2W Lewis 4/26 Low

Mostly converted, oak in cemetery, interesting field at

Labric (no camas)

Fern Prairie 2N 3E Clark 5/5 High Camas, delphinium

Fords Prairie 14N 2W Lewis 4/26 Low Some camas, native veg.

Frost Prairie 15N 1W Thurston 6/2 Bolander's peavine Moderate Dry forest species, some prairie species at north end

Gore Rd Prairies 12N 1E Lewis 5/21 No No prairie species seen

Grand Prairie 11N 2W Lewis 4/29 Low

Oaks, dry woodland species, checked twice, camas on

Ross rd.

Halfway Creek meadows 12N 4W Lewis 6/4

Nelson's

checkermallow,

hairy stemmed

checkermallow,

great polemonium High

Small meadows in otherwise forested habitat, but high

potential for more Nelson's checkermallow

Jackson Prairie 12N 1W Lewis 5/17 6/16 6/17 Bolander's peavine Low Camas, columbine. Well examined by bike.

Jorgensen Road Prairie 12N 1E Lewis 5/21 No No prairie species seen

Kennedy Rd. Prairie 12N 1E Lewis

King Corner wetlands 4N 2E Clark

Klaber Prairie 12N 4W Lewis 5/17 Low Plowed on one side of road, lots of manroot on other.

Kruger Prairie 13N 1W Lewis 4/26 Moderate

Native dry forest species, interesting spot at MP 6, also in

S20. Thermopsis montana

Table 3. Prairies of southwestern Washington

6

7

Prairie

Township Range County Date Date #2

Bike

date Rare species Return? Comments

Lacamas Prairie 2N 3E Clark 5/5 Many High Need to check roadsides and properties in vicinity - bike.

Lacamas Prairie 12N 1W Lewis 4/29 6/3

Kincaid's lupine,

hairy stemmed

checkermallow

(taxonomic issues)

High

Camas, lots of wet areas, lead on Frost Road for

Eryngium, oregon ash/oak on frost Rd, wet prairie

Layton Prairie 11N 1W Lewis 5/18 Low Tiny bit of lupine and camas - mostly hayfields

Lewis and Clark Prairie 12N 1W Lewis 4/29 6/16 Bolander's peavine Low

Camas, Danthonia californica, Fragaria, Lupinus

polyphyllus, other natives. Well searched by me and

Peter Morrison.

Lewisville wetlands 4N 2E Clark

Longview Prairie 8N 2W Cowlitz

Lucas Valley Prairie 13N 1W Lewis 4/26 Low Converted to ag to roadside

Middle Fork Road Prairie 13N 1E Lewis

Mill Plain 1N 2E Clark

Mossyrock Prairie 12N 2E Lewis

Mud Creek 3N 2E Clark

Napavine Prairie 12N 2W Lewis No Nothing left, ag, mowed.

Newaukum Prairie 13N 1W Lewis 4/26 High Cursory

Onalaska Prairie 13N 1E Lewis

Oppelt Road Prairie 13N 1E Lewis 4/26 Moderate Some Thermopsis

Orchards Prairie 2N 2E Clark

Pe Ell Prairie 13N 5W Lewis

Pe Ell Prairie 13N 5W Lewis

Pleasant Valley Road Prairie 13N 3W Lewis 5/17 No All agriculture

Salkum Prairie 12N 1E Lewis 5/21 No No prairie species seen

Salmon Creek 3N 1E Clark

Salzer Valley Road Prairie 14N 2W Lewis

Silver Lake Prairies 10N 1W Cowlitz No Forest

Stearns Creek Prairie 13N 3W Lewis

Stillman Prairie 12N 4W Lewis

Toutle Prairie 10N 1W Cowlitz

Twin Oaks Prairie 13N 3W Lewis

Waunch Prairie 15N 2W Lewis

Yacolt Prairie 4N 3E Clark

Some portion of thirty-two of these areas (48%) were visited in the course of the

reconnaissance, and of those, twenty-three had some remnant prairie species. Nine were

entirely converted to cropland or may have been mis-mapped. Nine supported at least

one, and often several, rare plant species. No large areas of prairie vegetation were

found, with the exception of several acres within Lewis and Clark State Park (described

below).

The mapping and reconnaissance were quite successful in differentiating completely

converted prairie areas from those that still supported some remnant vegetation and had

some potential for rare species. In some cases the entire former prairie area could be seen

from the road, and in other cases there may still be remnant prairie vegetation on private

land that was not visible from the road.

Table 3. Prairies of southwestern Washington

The maps were also quite accurate in predicting the presence of remnant prairie

vegetation. In many cases, the mapped boundary corresponded to the edge of the camas

or larkspur populations. The Lewis and Clark State Park area was the only prairie area

seen in the course of the reconnaissance that was not predicted from the maps.

Most surprising was the incidence of rare species even in remnant prairie areas that had

been nearly entirely converted to agricultural uses. Nearly all of the rare plant

populations found in the course of the survey were found along fencerows, and in most

cases the vegetation on either side of the fence was dominated by non-native species.

Some rare plants were seen in fields that were completely dominated by non-native

species. No rare plants were found outside the boundaries of mapped historical prairies

and/or historical prairie soils, despite reconnaissance work in these areas.

3.2. Historical prairies with remnant prairie species

3.2.1. Lewis and Clark State Park, Lewis County

The remnant prairie in the open, southwestern portion of the state park (which

was not mapped as prairie on either GLO maps or soils maps) supported

Danthonia californica, Fragaria virginiana, Potentilla gracilis, Solidago

canadensis, Ranunculus flammula, Lupinus polyphyllus, Camassia quamash,

Plagiobothrys figuratus, and Eriophyllum lanatum, all of which are associated

with wet and/or dry prairie. There are large ditches in several areas, and plowed

strips that do not support native vegetation. Most of the area appears to have been

plowed and/or ditched and its surface is unnaturally uneven as a result, with linear

strips of higher and lower ground. It seems likely that this portion of the state park

was once wet or at least mesic prairie, but the area has been extensively altered

and invaded by non-native grasses and forbs, including Holcus lanatus and

presumably non-native Festuca rubra. It may have once been contiguous with

the very large Lacamas Prairie.

The entire area is about 50 acres, but the total area with some native vegetation at

this point is probably less than 3 acres. Nonetheless, this is the largest known

area of public land in Lewis County that supports a suite of native prairie species,

and it would be an excellent area for restoration. No rare species were found,

although other, drier forest-edge areas in the park support Lathyrus vestitus spp.

bolanderi.

3.2.2. Lacamas and Cowlitz Prairies, Lewis County

The Lacamas and Cowlitz Prairies are north of the Cowlitz River, near the

present-day town of Toledo. Portions of Lacamas Prairie are on the floodplain of

Lacamas Creek. The areas of prairie soil and GLO prairie comprise more than

5,000 acres, but the mosaic of wet prairie, dry prairie, Oregon ash wetland, and

8

oak woodland may have been much larger, and may have been as large as 10,000

acres.

Both prairies are named on USGS maps. At one time there may have been two

prairie areas separated by a more forested area, but at this point it would be

difficult to identify boundaries between the two prairies. The area is nearly

entirely privately owned, with the exception of the Toledo Girls Softball Field

(owned by the Toledo School District). Access is limited in many areas.

There are large areas of Camassia quamash var. maxima scattered throughout the

former Lacamas and Cowlitz Prairies, most notably on the low flood plains, and

generally in pastures that are otherwise nearly dominated by non-native grasses.

Other prairie species that were seen on the Lacamas and Cowlitz Prairies included

Lupinus polyphyllus, Plagiobothrys figuratus, Iris tenax, Eriophyllum lanatum,

and Balsamorhiza spp.. Although most of the area has been converted to

agriculture, other, less disturbed portions of the wet prairie are rapidly becoming

dominated by shrubs and Oregon ash.

A population of Kincaid’s lupine, Lupinus sulphureus ssp. kincaidii, and a

population of a Sidalcea that may be S. hirtipes (see discussion in Section 3.3.4)

were found on Lacamas Prairie. There are also older occurrences of S. hirtipes

from Lacamas Prairie. A number of other native wet prairie species from a parcel

on Lacamas Prairie on Frost Road: Downingia spp., Helenium autumnale,

Sisyrhinchium spp., and the rare Eryngium petiolatum (S. Erickson, pers. comm..

2004).

These former prairies should be the focus of more survey and inventory in future

years. It seems likely that further work will reveal other rare plant populations,

and perhaps larger remnants of wet or dry prairie and/or Oregon ash wetlands.

3.2.3. Drews Prairie, Lewis County

Drews Prairie is mostly west of Lacamas Creek and is bisected by Coon Creek,

which runs parallel to Lacamas Creek before joining it to the south. A number of

tributaries to Coon Creek also flowed through the prairie, and the topography,

hydrology, and current vegetation suggest that at least the central and northern

portions of Drews Prairie would have been wet prairie. Drews Prairie is now

bisected by Interstate 5, and there is remnant prairie vegetation on both sides of

the freeway.

The mapped GLO prairie was approximately 900 acres, but the USGS map

suggests that the prairie may have continued to the south beyond its mapped

boundary. Portions of Drews Prairie are farmed, but Drews Prairie has more non-

farmed grassland and shrubland than most of the historical prairies. There is also

9

a large Oregon ash wetland at the north end of the former prairie, that probably

developed after fire suppression. Drews Prairie is entirely private, and access is

limited. The northern portion of the Drews Prairie is for sale, and development

seems likely.

A number of wet and dry prairie (but primarily dry prairie) species were seen on

Drews Prairie: Camassia quamash var. maxima, Delphinium nuttallii (relatively

large numbers in fencerows on both sides of the freeway), Eriophyllum lanatum,

Aquilegia formosa, and Lupinus bicolor. Two rare species occur in very low

numbers on Drews Prairie: one plant of Kincaid’s lupine (Lupinus sulphureus ssp.

kincaidii) and approximately 5 plants of a Sidalcea that may be S. hirtipes.

Drews Prairie still supports significant undeveloped areas of former prairie,

remnant prairie species, and possibly other, larger populations of rare species. No

additional road surveys are necessary (given the limited access), but it is an area

that could benefit from further inventory away from road edges on private land

and possible acquisition for conservation.

3.2.4. Lacamas Prairie, Clark County

Lacamas Prairie in Clark County lay within and east of the present-day town of

Orchards, within the floodplain of Lacamas Creek. The GLO maps show a large

area of prairie comprising nearly 3,400 acres, west of Proebstel. However, based

on current vegetation, we know that the prairie continued to the east along the

floodplain at least as far as the northwest end of present-day Lacamas Lake,

where the floodplain began to narrow. This would increase the size of the

historical prairie to at least 4,600 acres. Based on current vegetation, at least the

southern portion of the prairie was wet prairie.

Lacamas Prairie is currently considered the only example of an intact remnant wet

prairie in Washington. It is the only prairie in the study area that supports an

element occurrence of a wet prairie community type: 11 acres of the tufted

hairgrass-California oatgrass community.

Lacamas Prairie also supports three rare prairie species: Bradshaw’s lomatium

(Lomatium bradshawii), hairy-stemmed checkermallow (Sidalcea hirtipes), and

Oregon coyote-thistle (Eryngium petiolatum).

The southern portion of Lacamas Prairie has been extensively inventoried in the

last decade, and was not a focus in this study. However, other areas on Lacamas

Prairie could be more carefully examined for rare species or other prairie

remnants.

10

3.2.5. Boistfort Prairie, Lewis County

Boistfort Prairie in Lewis County was in the Boistfort Valley, to the west of the

South Fork of the Chehalis River. There is a description of Boistfort Prairie from

1859 by J.G. Cooper (Anderson 1994). It was described as being 2 ½ miles long

by 1 mile wide, and “one of the most beautiful of the little prairies we meet”. The

GLO maps and prairie soil polygons suggest that the prairie may have been

approximately 1,200 acres of deep, generally well drained soil, with scattered wet

swales.

Nearly all of the Boistfort Valley is now farmed, and was converted to

agricultural use from the 1850s to the 1880s. Cathy Maxwell, a local botanist, has

been exploring the Boistfort Valley since the late 1980s, and made many of the

significant finds in the valley.

The most significant feature of the Boistfort Valley is a conical mound about 50

feet high that was used as a pioneer cemetery from the 1850’s, and was never

plowed. This mound, a few roadsides, and one pasture, are the only accessible

areas that still support some remnant prairie vegetation.

The Boistfort Cemetery mound supports a remarkable diversity of native prairie

species in a matrix of exotic grasses, including tall oatgrass. The native species

include Festuca roehmeri, Apocynum androsaemifolium, Aster subspicatus,

Brodiaea coronaria, Camassia leichtlinii, Eriophyllum lanatum, Ranunculus

occidentalis, Lupinus bicolor, Viola adunca, and Ligusticum apiifolium. A small

swale to the south of the mound also supports a few native wet prairie species,

including Plagiobothrys figuratus and Mimulus guttatus.

Remnants within Boistfort Prairie support known populations of the following

rare species: Kincaid’s lupine (Lupinus sulphureus ssp. kincaidii), pale larkspur

(Delphinium leucophaeum), and thin-leaved peavine (Lathyrus holochlorus). An

additional population of thin-leaved peavine was found during 2004 bicycle

surveys of the valley.

A butterfly survey in 2004 found the following unusual species at the Boistfort

Cemetery: Arctic skipper, which is uncommon in lowland southwestern

Washington, and Ranchman’s tiger moth, which is declining and almost entirely

restricted to wetland prairie environments (Ross 2004).

It is unlikely that further survey work along roads in the Boistfort Prairie area will

identify other rare plant populations, although there may be rare plant populations

on private land in the valley. A multi-agency group is working on developing a

conservation plan for the Boistfort Prairie, in an effort led by the Washington

Natural Heritage Program.

11

3.2.6. Halfway Creek Meadows, Lewis County

The Halfway Creek meadows are on several private parcels along the Pe-Ell-

McDonald Road, west of the Boistfort Valley. None of these areas were

identified through GLO maps or prairie soils polygons, but must have been

historically open, since they support one known population of the federally listed

Nelson’s checkermallow (Sidalcea nelsoniana) and one population found in 2004

of a Sidalcea that may be S. hirtipes. These meadows were probably always

small openings associated with creek bottoms or burned areas. We suspect that

there could be additional populations of both species on other properties.

3.2.7. Jackson Prairie, Lewis County

Jackson Prairie is just north of the present-day Lewis and Clark State Park. It was

settled in 1845 by one of the earliest settlers in Washington, and was known as

Highland Prairie at that time (perhaps to distinguish it from the lower and wetter

Lacamas Prairie nearby). GLO maps and prairie soils suggest that the prairie was

about 1,000 acres. Most of the Jackson Prairie area is now dry second-growth

coniferous forest, pasture, or hayfields

A number of prairie species persist on roadside or in pastures in Jackson Prairie,

including Camassia spp., Aquilegia formosa, Delphinium nuttallii, Lilium

columbianum, Fragaria virginiana, and Eriophyllum lanatum.

One rare species was found on Jackson Prairie: Bolander’s peavine (Lathyrus

vestitus ssp. bolanderi). Several clusters of this rhizomatous species were found

along roadsides in otherwise forested habitats.

The roadsides of Jackson Prairie and Matilda Jackson County Park have been

surveyed by bicycle and on foot. There may be small prairie remnants or other

populations of rare species on private land on Jackson Prairie.

12

3.3. Rare plants found in 2004 surveys

Ten populations of five rare plant species were found on historical prairies during the

2004 reconnaissance surveys (Table 2). Each is described in detail below.

Table 4. Rare plant populations found in 2004

Scientific name Common name

Federal

status

Washington

status

New populations found

Lupinus sulphureus

ssp. kincaidii Kincaid’s lupine Endangered Endangered

Drews Prairie (1). Lacamas Prairie

(1)

Lathyrus vestitus

ssp. bolanderi Bolander’s peavine N/A Endangered

Cowlitz River Prairie (1), Lewis

and Clark State Park, (1), Jackson

Prairie (1).

Lathyrus holochlorus Thin-leaved peavine

Species of

Concern

Endangered

Boistfort Prairie (1)

Sidalcea sp. Checker-mallow N/A N/A

Drews Prairie (1),Lacamas

Prairie (1), Halfway Creek

Meadows (1)

Polemonium carneum Great polemonium N/A Threatened

Halfway Creek Meadows (1)

3.3.1. Kincaid’s lupine

Kincaid’s lupine (Lupinus sulphureus ssp. kincaidii) is

federally endangered and Washington State Endangered. Its

range is primarily in the Willamette Valley of Oregon, and in

Oregon it is the host plant for Fender’s Blue butterfly, a

federally endangered species. Prior to this work it was known

by the WNHP from one site on Boistfort Prairie, more than

100 miles north of its primary range.

Two small populations were found in Lewis County historical

prairies in 2004: one on Drew’s Prairie and one on the Lacamas Prairie. Only

one plant was seen on Drew’s Prairie, but a population of more than 40 plants

was found in a fencerow on Lacamas Prairie. Both populations are extremely

vulnerable to management activities, particularly herbicide use to maintain the

fenceline. We hope to find more plants in the vicinity of this population in

2005. These additional populations may provide seed and greater genetic

diversity for a potential reintroduction project for Kincaid’s lupine in

southwestern Washington.

13

3.3.2. Bolander’s peavine

Bolander’s peavine (Lathyrus vestitus ssp. bolanderi) is a

Washington State Endangered species. Its historical range was from

King County south to central California (Broich 1987). Prior to

2004 it was only known from Washington from one extant site in

Thurston County and several historical collection sites that no longer

support populations. Its habitat is dry, open to wooded sites, and the

Thurston County population was known from an historical prairie.

The Thurston County population was relocated and three other

populations were found in or near historical prairie areas during the

2004 surveys: one on the Cowlitz River Prairie, one on Jackson

Prairie, and one within Lewis and Clark State Park. In all cases, populations were

found along roadsides or other edges (river bluffs, forest edges) of otherwise dry,

wooded habitats, and plants did not continue into more heavily forested habitats.

The number of plants is difficult to ascertain, since the species is rhizomatous, but

all populations had hundreds of stems and the populations seemed robust.

However, 90% of the populations were along roadsides, and therefore vulnerable

to roadside management activities. There may be more populations in

southwestern Washington in similar habitats.

3.3.3. Thin-leaved peavine

Thin-leaved peavine (Lathyrus holochlorus) is

a Washington State Endangered species and a

federal Species of Concern. It is endemic to

the Willamette Valley and southwestern

Washington, and is also considered to be

declining in Oregon. The species grows

mostly along roadsides or fencerows, in

grasslands, in partially cleared land, or

climbing in low scrubby vegetation. The “roadside or fencerow” description may

reflect the destruction of its more characteristic prairie edge habitat. Prior to this

work it was known by the WNHP from one site on Boistfort Prairie, more than

100 miles north of its primary range.

One small population was found on Boistfort Prairie in a roadside fencerow,

approximately one mile north of the known population. The land on the other

side of the fencerow was plowed. This population is vulnerable to roadside

maintenance and fencerow maintenance, and is probably too small to be viable.

Seed should be collected from it for seed-banking. Other populations may be

found in Lewis County.

14

3.3.4. Checker-mallow

Until the 2004 surveys, 9 small populations of what was

believed to be hairy-stemmed checker-mallow (Sidalcea

hirtipes) were known from Washington. Most were known

from Lewis County historical prairies.

None of the previously known populations were relocated in

2004, but three new populations were found in Lewis County

during the 2004 reconnaissance: one on Drews Prairie, one on

Lacamas Prairie, and one in the Halfway Creek Meadows.

Collections were sent to Steve Gisler of the Institute for Applied

Ecology. He felt that they did not have the characteristics of S. hirtipes, but could

not assign them with assurance to any other taxon. Given their close proximity to

known populations of what has been considered S. hirtipes by the WNHP, it casts

some doubt on the identification of the other Washington populations. However,

all of the species of Sidalcea that occur in the prairies of the Willamette Valley

and western Washington have some degree of rarity, so we assume that this

entity is also rare. We plan to make more collections in 2005, and to send them to

the author of Sidalcea for the Flora of North America.

3.3.5. Great polemonium

Great polemonium (Polemonium carneum) is a Washington

State Threatened species. Its range is from western

Washington to central California. In Washington it is known

entirely from coastal or southwestern counties. Its habitat is

prairies and woodlands from low to moderate elevation.

One population of great polemonium was found on private

land in the Halfway Creek Meadows, along the edge of a

meadow and second growth forest.

4. APPLICATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

4.1. Applications

The 2004 reconnaissance showed that the GLO maps, combined with prairie soils maps,

can be a powerful tool for identifying rare prairie plant populations. There is a suite of

rare animals also associated with prairies, and these maps may be helpful in identifying

remnant populations of prairie-dependent butterflies and other animals. The Boistfort

15

Prairie remnant supported two uncommon Lepidoptera species, despite its small size

(Ross 2004).

The GLO maps and soil layers can also be used by agencies and conservation districts

working with private landowners. By identifying areas that may have once supported

prairie vegetation, and/or being aware of the possibility of prairie remnants within

historical prairie areas on private land, conservation districts may be able to help

landowners conserve or restore prairie vegetation on their land.

Although no large prairie remnants were found during the 2004 reconnaissance, it is

possible that there may be significant prairie remnants in southwestern Washington. If

found, these areas would be a high priority for conservation and/or acquisition. The

reconnaissance showed that the combination of GLO maps and prairie soils layers are

good predictors of remnant prairie vegetation.

4.2. Additional surveys

The prairie maps generated through this project will be used for USFWS funded rare

plant surveys in 2005 and 2006, and may also be used by WDFW for rare butterfly

surveys.

4.3. Significance of findings and conservation recommendations

Prior to 2004, several rare prairie species (Kincaid’s lupine, Bolander’s peavine, thin-

leaved peavine) were only known from one extant population in Washington. Although

the populations that were found during the reconnaissance were small, they are

significant by what they suggest about the former range of these species. We now know,

for instance, that Kincaid’s lupine probably occurred on at least three prairies, rather than

on one, isolated prairie far from other populations.

None of the populations found during the reconnaissance are, when considered

separately, highly viable populations. All of them are small, occur in a fragmented,

degraded landscape, and are vulnerable to management and road maintenance activities.

However, the seed from these populations could be critical for future reintroduction of

these rare species to one or more viable, more intensively managed and protected sites.

Conservation recommendations from this project include:

Collect seed for seed banking from all roadside rare plant populations. Given the

low viability of the populations, seed collection could be at a higher level than is

generally recommended.

Contact and work with landowners where rare plants occur on or near private

property.

16

Contact and work with State Parks and the Toledo School District to explore

restoration and maintenance of prairie remnants.

Share maps, this report, and rare plant fact sheets with conservation district and

WDFW biologists, who may be working on private land in southwestern

Washington.

Continue surveys for remnant prairies and rare plant populations in historical

prairie areas.

Contact and work with county road crews to prevent spraying in the vicinity of

rare plant populations.

Consider conservation possibilities at Drews Prairie, Lacamas Prairie, Boistfort

Prairie.

5. REFERENCES

Anderson, A.R., ed. 1994

. Plant Life of Washington Territory: Northern Pacific

Railroad Survey, Botanical Report 1853-1861 (with map). Papers by James G.

Cooper and Nelsa M. Buckingham. Washington Native Plant Society, Occasional

Papers Vol. 5, Seattle, Washington.

Broich, S.L. 1987. Revision of the Lathyrus vestitus-lactiflorus complex (Fabaceae).

Systematic Botany 12: 139-153.

Call, W. A. 1974. Soil survey of Cowlitz area, Washington. U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service.

Chappell, C. B., M. S. Mohn Gee, B. Stephens, R. Crawford, and S. Farone. 2001.

Distribution and decline of native grasslands and oak woodlands in the Puget

Lowland and Willamette Valley ecoregions, Washington. Pages 124-139 in

Reichard, S. H., P.W. Dunwiddie, J. G. Gamon, A.R. Kruckeberg, and D.L.

Salstrom, eds. Conservation of Washington's Rare Plants and Ecosystems.

Washington Native Plant Society, Seattle, Wash. 223 pp.

Chappell, C. B., M.S. Gee, and B. Stephens. 1999. A geographic information systems

map of existing grasslands and oak woodlands in the Puget Lowland and

Willamette Valley ecoregions, Washington. Washington Natural Heritage

Program, Dept. of Natural Resources, Olympia, Wash.

Crawford, R.C. and H. Hall. 1997. Changes in the south Puget Sound prairie landscapes.

Pages 11-15 in Dunn, P. and K. Ewing, editors. 1997. Ecology and Conservation

of the South Puget Sound Prairie Landscape. The Nature Conservancy of

Washington, Seattle, Washington.

Ellis, David V., and Douglas C. Wilson. 1995 Protecting Clark County's archaeological

heritage: a database and predictive model. Archaeological Investigations

17

Northwest, Inc., Report No. 85. Prepared for Heritage Trust of Clark County,

Vancouver, Washington.

Fowler, R. H., and A. O. Ness. 1954. Soil survey of Lewis County, Washington. U.S.

Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service.

McGee, D. A. 1972. Soil survey of Clark County, Washington. U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service.

Norton, H.H. 1979. The association between anthroppgenic prairies and important food

plants in western Washington. Northwest Anthropological Research Notes

13:199-219.

Ross, D. 2004. Butterfly surveys for Taylor’s checkerspot (Euphydryas editha taylori)

and Fender’s/Puget blue (Icaricia icarioides ssp.) at Boistfort Prairie, Lewis

County, Washington. Report submitted to the Washington Natural Heritage

Program, Olympia, Washington.

Wilson, Douglas C. 2001 Assessment and update of Clark County, Washington’s

archeological predictive model and database. Report prepared for Clark County

Community Development. Archaeology Consulting Report No. 14, Portland,

Oregon.

18