National

Insurance

contributions

explained

Institute for Fiscal Studies

1

ã The Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2021

National Insurance

contributions explained

National Insurance contributions (NICs) are the UK’s second-biggest tax, expected

to raise almost £150 billion in 2021–22 – about 20% of all tax revenue. They are

paid by employees and the self-employed on their earnings, and by employers on

the earnings of those they employ.

Up to a certain threshold, earnings are free of NICs. The main rates are payable on

earnings above that level, but the employee and self-employed rates – though not

the employer rate – are lower on earnings above a higher threshold (see chart and

table below).

National Insurance contribution rates, 2021–22

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

16%

£0 £10,000 £20,000 £30,000 £40,000 £50,000 £60,000 £70,000

Marginal rate of NICs

Annual earnings

Employer Employee Self-employed (Class 4)

2

ã The Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2021

National Insurance contribution rates, 2021–22

Threshold name

Weekly

earnings

threshold

Annual

equivalent

Employee

NICs rate

Employer

NICs rate

–

£0

£0

0%

0%

Secondary threshold

£170

£8,840

0%

13.8%

Primary threshold

£184

£9,568

12%

13.8%

Upper earnings limit

£967

£50,270

2%

13.8%

Threshold name

Weekly

equivalent

Annual

profits

threshold

Self-employed

Class 4 NICs

rate

Self-employed

Class 2 NICs

rate

–

£0

£0

0%

£0

Small profits threshold

£125

£6,515

0%

£3.05 per week

Lower profits limit

£184

£9,568

9%

£3.05 per week

Upper profits limit

£967

£50,270

2%

£3.05 per week

Note to chart and table: Rates in table apply above the stated thresholds. The chart and table

ignore the employment allowance. Employer NICs rates shown are the rates of secondary

Class 1 NICs (on ordinary earnings), Class 1A NICs (on those benefits in kind that are

subject only to employer NICs) and Class 1B NICs (on PAYE settlement agreements,

arrangements negotiated between employers and HMRC whereby employers agree to pay

tax on earnings or benefits in kind which would otherwise fall to be paid by their employees).

Class 3 NICs are voluntary and paid at a flat rate of £15.40 a week in 2021–22 in exchange

for certain benefit entitlements. In the chart, self-employed (Class 4) NICs line excludes

Class 2 contributions, which are shown in the table. The chart shows annual thresholds,

which for employee and employer NICs assume earnings are stable throughout the year.

Unlike income tax, NICs are not charged on income from other sources such as

savings, pensions or property. Payment of NICs qualifies individuals to receive

certain social security benefits (most notably the state pension). In practice,

however, the link between contributions paid and benefits received is vanishingly

weak and NICs essentially act as a second income tax.

3

ã The Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2021

What incomes are subject to NICs?

NICs are levied on the earnings of individuals aged 16 or over. Individuals over the

state pension age are not liable for employee or self-employed NICs, but employer

NICs are still due on their earnings.

The earnings that are taxable are earnings from employment and earnings (profits)

from self-employment (as a sole trader or member of a partnership – note that this

does not include profits from a company, though a company might employ its

owner and pay him/her a salary). In measuring earnings for NICs purposes:

§ Work-related

expenses can be deducted; the rules on what can be deducted are

much stricter for employees than for the self-employed.

§ The treatment of benefits in kind (payment to employees in the form of goods

or services rather than money, such as company cars or health insurance) varies.

Some are subject to NICs in full; others (generally those that cannot be sold or

traded) are subject to employer but not employee NICs.

NICs are not levied on other income, such as income from savings and investments,

rental income from property, private pensions, state pensions and other social

security benefits.

Unlike for income tax, private pension contributions made by an employee or self-

employed individual cannot be deducted from earnings for NICs purposes. This

makes sense, since (unlike income tax) NICs are not levied on the future pension

income they generate. However, pension contributions made by an employer on

their employee’s behalf are not included in earnings for NICs purposes. This means

that remuneration in the form of employer pension contributions escapes NICs

altogether: there are no NICs when the money is paid into the pension, and no NICs

when money is received from the pension either.

4

ã The Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2021

Employee and employer NICs rates,

thresholds and reliefs

NICs are formally divided into classes. NICs on employment income are Class 1

NICs; employees pay primary Class 1 NICs, while employers pay secondary Class

1 NICs.

The table below shows the current rates and thresholds of employee and employer

NICs. Class 1 NICs liabilities are assessed separately for each period for which an

employee is paid; the table shows the thresholds in weekly terms, as is

conventional, but they are adjusted pro rata for employees who are paid (say)

monthly.

Class 1 (employee and employer) National Insurance contribution rates,

2021–22

Threshold name

Weekly

earnings

threshold

Annual

equivalent

Employee

NICs rate

Employer

NICs rate

–

£0

£0

0%

0%

Secondary threshold

£170

£8,840

0%

13.8%

Primary threshold

£184

£9,568

12%

13.8%

Upper earnings limit

£967

£50,270

2%

13.8%

Note: Rates apply above the stated thresholds. The table ignores employment allowance.

Rates of secondary Class 1 NICs shown are also the rates of Class 1A and Class 1B NICs,

which apply respectively to those benefits in kind that are subject only to employer NICs and

to PAYE settlement agreements, arrangements negotiated between employers and HMRC

whereby employers agree to pay tax on earnings or benefits in kind which would otherwise

fall to be paid by their employees.

More about the NICs assessment period

NICs thresholds are usually expressed in weekly terms. But in fact the NICs due on a

particular employee’s earnings are assessed according to the period for which they are paid.

Someone paid monthly, for example, will be liable for employee NICs if their earnings for

5

ã The Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2021

the month are above £797, the monthly equivalent of the £184 threshold shown in the table.

Liability in each pay period is assessed separately, unlike income tax, which depends on the

individual’s income for the year as a whole.

In some ways, this makes NICs easier to administer: NICs can be calculated

straightforwardly for each salary payment, without the need to make adjustments if it turns

out that some months’ earnings are not typical of the year as a whole. But it unfairly creates

differences in overall tax payments between people with similar annual earnings, depending

on whether the earnings are received evenly through the year or vary from month to month.

Relative to people with the same annual earnings spread evenly, it penalises people with

low, volatile earnings (for example, someone must pay NICs if they earn more than the

threshold in a particular period, even if their average earnings across the year are below the

threshold) but favours people with high, volatile earnings (since earnings concentrated in a

particular period might fall in large part above the upper earnings limit (UEL) and be

subject to employee NICs of only 2%, even if their earnings are below the UEL on average).

People with more than one source of earnings

Where an individual has more than one job, or earnings from both employment and self-

employment, NICs are charged separately on each. However, the full 12% employee NICs

rate only applies up to a maximum of the (annualised) upper earnings limit across all jobs

(for the year as a whole). If an individual has two jobs each paying just under the UEL,

therefore, part of their earnings will be subject to the 2% rate that applies above the UEL

even though neither job pays above the UEL. Broadly speaking, each job has its own NICs-

free threshold but the UEL applies to an individual’s earnings across all jobs. Low earners

thus pay less NICs if their earnings are split across jobs, but high earners do not pay more

NICs if their earnings are split across jobs.

Employer NICs have, in effect, a tax-free threshold per employer as well as a tax-

free threshold per employee. The employment allowance reduces each employer’s

aggregate NICs liability by up to £4,000 a year, provided that their liability in the

previous year was less than £100,000 (and that a company director is not the sole

employee earning above the secondary threshold). This takes many small

6

ã The Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2021

employers out of paying employer NICs altogether, although much employer NICs

revenue comes from big employers which are not eligible for the employment

allowance.

Two groups of employees have their earnings taxed less heavily:

§ No employer NICs are payable on the earnings, up to the upper earnings limit

(UEL), of employees aged under 21 or apprentices aged under 25.

§ A special married women’s reduced rate of employee NICs, 5.85%, is available

on earnings between the primary threshold and the UEL (in exchange for lower

benefit entitlements), but since May 1977 this option has been available only to

married women paying it almost continuously since that date, which is now a

very small number.

Employee NICs are taken out of earnings, whereas employer NICs are paid on top

of earnings. The rates of the two are therefore not directly comparable, and when

looking at the overall level of NICs on employment, the headline rates should not

simply be added up and compared with the level of gross earnings (see the technical

note below). A more informative calculation is to look at total NICs paid as a

fraction of the total amount the employer pays out (i.e. their total labour cost –

earnings plus employer NICs). On this basis, the combined main NICs rate – the

marginal rate applying between the primary threshold and the UEL – is not 25.8%

(12% + 13.8%) but 22.7% ((12% + 13.8%) ÷ 113.8%).

Technical note: Combining employee and employer NICs rates

When considering the total NICs charged on a job, it is tempting simply to add up employee

and employer NICs and look at how the total relates to earnings. For example, between the

primary threshold and the UEL, the employee NICs rate is 12% and the employer NICs rate

is 13.8%, so it might seem natural to say the total NICs rate is 25.8%. However, that is not

very informative and can be misleading.

The problems with simply adding up employee and employer NICs rates arise because

employee NICs are taken out of earnings while employer NICs are paid on top of earnings.

Continuing the above example, for £100 of earnings, the £12 employee NICs reduce the

amount the employee receives to £88 while the £13.80 employer NICs increase the amount

the employer pays to £113.80. In other words, the tax base for NICs – gross earnings –

includes employee NICs but does not include employer NICs.

7

ã The Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2021

Because of this, looking at how total NICs liability relates to earnings without

disaggregating employer and employee NICs is not very informative: it doesn’t tell us what

proportion of what the employer pays is ultimately received by the employee. Saying that,

for example, total NICs are £50 when earnings are £100 could mean very different things

depending on the balance of employer and employee NICs. If it were all employee NICs,

the employee would receive half of what the employer paid out; if it were all employer

NICs, the employee would receive two-thirds of what the employer paid out.

Worse, looking at total NICs relative to earnings is potentially misleading. Simply adding

up the employee and employer NICs rates can be a false guide to the overall burden of the

tax: a system with a 25% overall NICs rate on that measure might actually be higher-tax

than a system with a 30% overall NICs rate, if the 25% comes entirely from employee NICs

(£25 NICs for each £100 paid by the employer) while the 30% comes entirely from

employer NICs (£30 NICs for each £130 paid by the employer – only £23 for each £100

paid out).

A more sensible measure of the combined NICs rate is total (employee and employer) NICs

paid as a proportion of the total (NICs-inclusive) cost to the employer. Between the primary

threshold and the UEL, for example, the 12% employee NICs rate and 13.8% employer

NICs rate mean that NICs are £25.80 (£12 employee NICs + £13.80 employer NICs) for

each £113.80 the employer pays out (£100 earnings + £13.80 employer NICs), so the

combined marginal NICs rate on the employer’s payment is 22.7% (£25.80 ÷ £113.80). This

rate (and the equivalents for different levels of labour cost) are shown in the chart below.

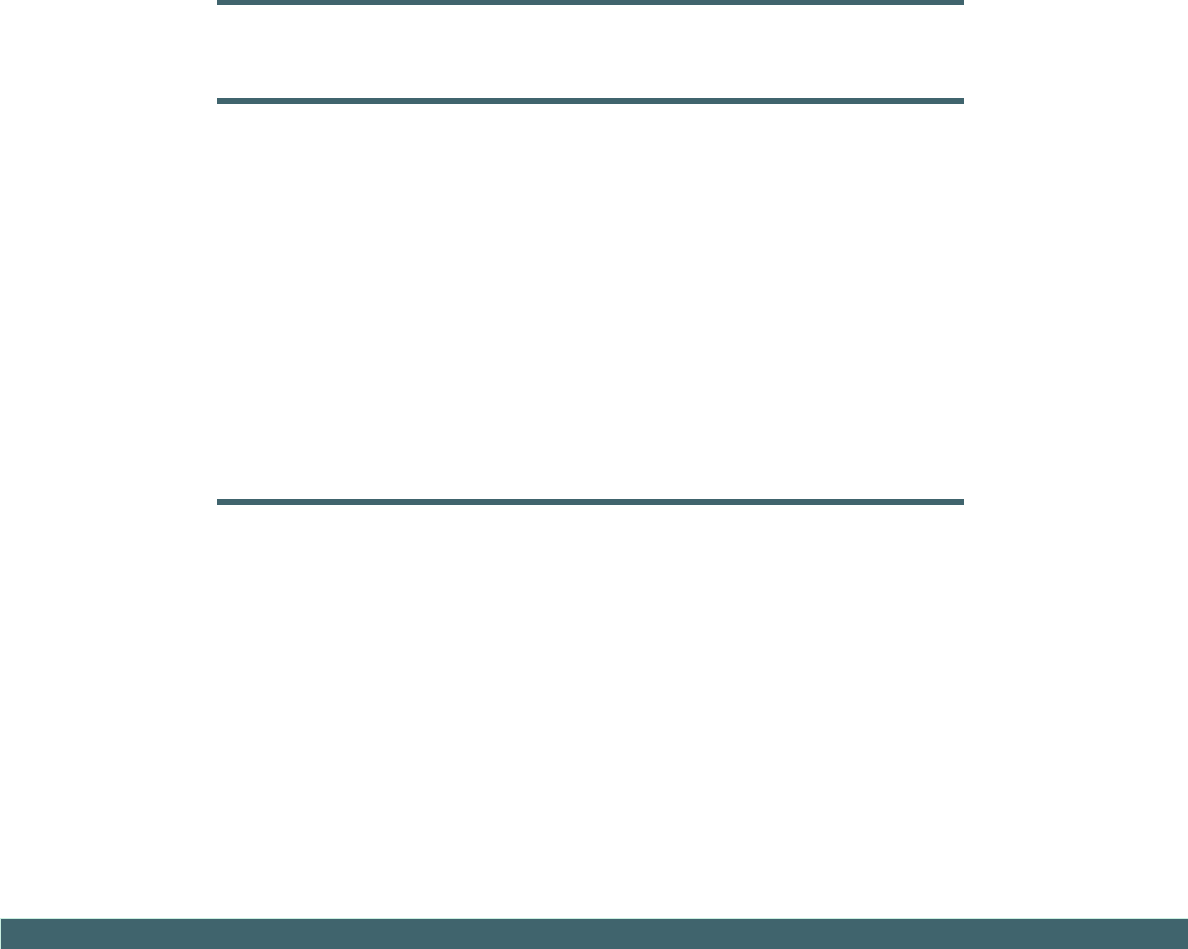

The chart below shows the combined rates of employee and employer NICs. The

marginal NICs rate is the proportion of each additional £1 of labour cost paid by

the employer that is taken in NICs. The average NICs rate is the proportion of the

total labour cost paid by the employer that is taken in NICs. The chart highlights

that, while NICs are progressive across most of the earnings distribution – the

average tax rate is higher for those earning more – it is not progressive at the top.

The average rate peaks at 18.9% at the UEL, the point at which the marginal rate of

employee NICs falls from 12% to 2% and the overall marginal NICs rate falls from

22.7% to 13.9%.

8

ã The Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2021

Marginal and average combined rates of employee and employer National

Insurance contributions, 2021–22

Note: Labour cost is gross earnings + employer NICs; marginal NICs rate is employer +

employee NICs as a percentage of that labour cost. The chart ignores employment

allowance.

Source: Authors’ calculations using tax rates from IFS Fiscal Facts.

Self-employed NICs rates, thresholds and

reliefs

The self-employed pay two classes of NICs:

§ Class 2 NICs are paid at a low, flat rate – currently £3.05 per week – by anyone

whose self-employment income (profits) exceeds the small profits threshold of

£6,515 per year.

§ Class 4 NICs are the main element of self-employed NICs, paid in relation to

annual profits above the lower profits limit of £9,568 per year.

Current NICs rates for the self-employed are shown in the table below.

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

£0 £200 £400 £600 £800 £1,000 £1,200 £1,400

Weekly labour cost

Marginal rate Average rate

9

ã The Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2021

Self-employed National Insurance contribution rates, 2021–22

Threshold name

Annual profits

threshold

Class 2 NICs rate

Class 4 NICs rate

–

£0

£0

0%

Small profits threshold

£6,515

£3.05 per week

0%

Lower profits limit

£9,568

£3.05 per week

9%

Upper profits limit

£50,270

£3.05 per week

2%

Note: Rates apply above the stated thresholds.

The main rate of self-employed NICs is lower than the main employee rate – 9%

rather than 12% – and, more importantly in terms of the overall tax burden, there is

no equivalent of employer NICs levied on the profits of the self-employed. The

total NICs levied on self-employment income are therefore much lower than those

on employment income, as shown in the chart below. The government estimates

that having lower NICs for the self-employed cost it £5.9 billion in 2019–20. There

is no good justification for the preferential NICs treatment of self-employment.

1

1

See S. Adam and H. Miller (2021), ‘Taxing work and investment across legal forms: pathways to

well-designed taxes’, IFS Report R184, https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/15272.

10

ã The Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2021

National Insurance contributions on employment vs self-employment, 2021–

22

Note: Horizontal axis shows labour cost (gross earnings + employer NICs) for employment

and gross profits (earnings) for self-employment; marginal NICs rate is expressed as a

percentage of that labour cost / profit. Self-employed NICs lines include Class 2 contributions

in the average rate, but exclude them in the marginal rate. Employee + employer lines

assume earnings are stable throughout the year and ignore the employment allowance.

Source: Authors’ calculations using tax rates from IFS Fiscal Facts.

National Insurance contributions and

benefits

National Insurance originated as a system of contributions in exchange for

entitlement to specific (‘contributory’) social security benefits. However, the link

between contributions and benefits has weakened over time, to the point where

there is now barely any connection at all between the amount of NICs paid and the

amount of benefits received. Throughout the many reforms to both contributions

and benefits that have taken place over the years, minimal attention has been paid to

closeness of the link between the two.

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

£0 £10,000 £20,000 £30,000 £40,000 £50,000 £60,000 £70,000

Annual labour cost / profits from self-employment

Marginal rate: employee + employer Average rate: employee + employer

Marginal rate: self-employed (Class 4) Average rate: self-employed

11

ã The Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2021

By far the biggest contributory benefit is the state pension. But it is now quite hard

to live in the UK and not earn entitlement to a full state pension. The contributory

system does serve to withhold certain benefit entitlements from some small groups.

But its main practical function nowadays is to ensure that foreigners cannot retire to

the UK and claim a full state pension. There may be a case for a genuine social

insurance system, but it is not what we currently have.

More about the link between contributions and benefits

There are still a number of contributory benefits:

§ state pension;

§ ‘new-style’ jobseeker’s allowance (but not income-based jobseeker’s allowance or its

equivalent in universal credit);

§ ‘new-style’ employment and support allowance (but not income-based employment and

support allowance or its equivalent in universal credit);

§ bereavement support payment;

§ maternity allowance.

(Some other historical benefits are still being paid for which entitlement depends on past

contributions, but new contributions no longer generate new entitlements to them.)

Statutory maternity/paternity/adoption/shared-parental pay is not strictly a contributory

benefit, but entitlement requires the claimant to have been employed and earning above the

National Insurance lower earnings limit (see below) for a period before claiming, much like

the way in which entitlement to contributory benefits is accrued.

We do not describe these benefits here, or the complicated rules that relate contributions to

entitlements. The important fact is that in practice there is very little link between the

amount of contributions someone pays and the benefits they receive, for several reasons:

§ Contributions rise with earnings; benefits do not.

§ Some people receive entitlements without paying NICs. Employees are treated as

having paid NICs if they earn at least the lower earnings limit (LEL, £120 per week in

2021–22), even if they earn less than the primary threshold (£184 per week) and

therefore do not actually pay NICs. Furthermore, people receive National Insurance

‘credits’ towards their benefit entitlements in a whole range of circumstances when they

12

ã The Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2021

are not in paid work at all, including if they are unemployed, sick or disabled, or caring

for a child under 12 or someone with a disability.

§ Others see no benefit from paying additional contributions. In some cases, NICs paid in

a given year can be insufficient to generate additional entitlements; in others, once

someone has earned a full entitlement, paying more NICs does not confer any

additional benefit. For example, an individual must pay contributions (or be credited

with contributions, as explained above) for 10 years to qualify for any state pension at

all, and for 35 years to qualify for a full state pension; someone contributing for less

than 10 years therefore gets nothing in return for their contributions, while someone

who already has 35 years of contributions/credits gets nothing more for continuing to

contribute.

§ People who are not entitled to full contributory benefits can often claim as much, or

almost as much, in means-tested benefits instead. The incremental value of receiving

contributory benefits is often very small.

The self-employed accrue entitlement to contributory benefits via their Class 2 (not Class 4)

contributions. Unlike employees, they do not accrue entitlement to new-style jobseeker’s

allowance or to statutory maternity/paternity/adoption/shared-parental pay. But the value of

these reduced entitlements is small: nowhere near enough to justify the much lower NICs

levied on self-employment income than on employment income.

Self-employed people who earn less than the small profits threshold, and therefore do not

have to pay Class 2 NICs, can choose to pay them voluntarily in order to build up benefit

entitlements.

Class 3 contributions are an entirely voluntary form of NICs, again paid (at a flat rate of

£15.40 a week in 2021–22) to build up entitlements to certain contributory benefits. They

can be paid in a variety of circumstances, but in practice very few people do so, typically

UK citizens living (but not working) abroad in order to maintain their entitlement to benefits

when they return.

The National Insurance Fund

NICs are often thought of as being ring-fenced to pay for the contributory benefits described

above, or to pay for the National Health Service. The reality is different.

13

ã The Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2021

Some NICs revenue (about 19% in recent years) is allocated directly to the NHS. That is

topped up from general taxation to whatever the government wishes to spend on the NHS in

total: how much of that total notionally comes from NICs revenue is irrelevant. The

remaining NICs revenue is paid into the National Insurance Fund. Notionally, the NI Fund

is financially separate from other parts of government and is used to fund contributory

benefits. In reality, however, this separation is illusory. In years when the fund is not

sufficient to finance benefits, it is topped up from general taxation revenues; and in years

when the fund builds up a surplus, it is used to reduce the national debt: essentially, the

government lending money to itself. This makes the separation of the NI Fund from the

main government account more or less meaningless. The government decides how much to

raise in NICs, and how much to spend on the NHS and on contributory benefits; the

amounts need not be related to each other, and generally aren’t.

NICs and income tax

The UK has two taxes on income – income tax and National Insurance

contributions.

NICs are paid over to HMRC along with income tax by employers and the self-

employed.

The chart below shows the combined marginal rate schedule for someone whose

income is stable and comes entirely from earnings.

14

ã The Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2021

Combined marginal rates of income tax and National Insurance

contributions outside Scotland, 2021–22

Combined marginal rates of income tax and National Insurance

contributions in Scotland, 2021–22

Note: Horizontal axis shows labour cost (gross earnings + employer NICs) for employment

and gross profits (earnings) for self-employment; marginal rates are expressed as a

percentage of that labour cost / profit. Self-employment lines exclude Class 2 NICs, which

are a flat-rate £3.05 per week for anyone with annual self-employment earnings of £6,515 or

more. The charts assume all income is from earnings. Employment lines assume earnings

are stable throughout the year and ignore the employment allowance.

Source: Authors’ calculations using tax rates from IFS Fiscal Facts.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

£0 £50,000 £100,000 £150,000 £200,000

Marginal income tax + NICs rate

Annual labour cost / profits from self-employment

Employment Self-employment

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

£0 £50,000 £100,000 £150,000 £200,000

Marginal income tax + NICs rate

Annual labour cost / profits from self-employment

Employment Self-employment

15

ã The Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2021

A striking feature is the number of thresholds at which the overall marginal tax rate

rises or falls. This is partly because of oddities in the income tax schedule, notably

the withdrawal of the personal allowance once income exceeds £100,000. But it

also reflects a lack of alignment between income tax and NICs. At present, the

upper earnings limit and the upper profits limit (UPL) are aligned with the higher-

rate threshold (except in Scotland). But income tax, employee (and self-employed)

NICs and employer NICs all start to be paid at different levels of income.

The schedule in Scotland looks even more complicated than that in the rest of the

UK. This is because (a) Scotland has an unnecessarily complicated five-band

income tax schedule (with separate 19%, 20% and 21% rates) and (b) Scotland has

devolved power over income tax but not NICs, so when it chooses an income tax

higher-rate threshold which is lower than in the rest of the UK it cannot align it with

the UEL and UPL. This means that (for someone with stable earnings) there is a

band of earnings between the Scottish higher-rate threshold of £43,662 and the UK

UEL/UPL of £50,270 where Scottish residents pay both higher-rate income tax and

the main rate of NICs.

Aligning thresholds within the current system matters less than it might seem for

simplification, however. Since income tax and NICs are assessed over different

periods (annual for income tax, pay period for Class 1 NICs) and on different

measures of income, it is quite possible for someone to be above the income tax

higher-rate threshold but below the UEL, or vice versa, anywhere in the UK.

Given the similarity of the two taxes, it would be simpler – both more transparent

and less administratively burdensome – if they were merged into a single tax. Most

of the remaining differences between the two taxes could be retained if that were

considered desirable (for example, a combined tax could be charged at a lower rate

on items that are currently subject to one tax but not the other); but integration

would underline the illogicality of most of the current differences between the two

taxes and provide an opportunity to remove them. Calls for such integration have

been widespread for many years, but successive governments have rejected them.

What we have seen instead is gradual moves towards greater alignment between the

two taxes, making them ever more similar.

16

ã The Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2021

Progress towards further alignment has slowed. In 2016, the Office of Tax

Simplification produced two reports

2

proposing (relatively modest) NICs reforms to

bring them closer to income tax; but the government rejected the main suggestions

(for involving too much upheaval) and U-turned on its initial acceptance of two

others, ultimately making only very minor technical adjustments.

The apprenticeship levy

The apprenticeship levy – a new tax introduced in 2017 – is not part of NICs, but it

acts very much like additional employer NICs.

The levy is applied to employers with a total annual wage bill of more than

£3 million. The levy is 0.5% of the total wage bill, with an allowance of up to

£15,000 to set against the tax. In other words, it is a 0.5% levy on wages in excess

of £3 million.

This is in effect a 0.5% supplement to employer NICs for large employers. The

measure of earnings taxed is the same as for employer NICs, and the £15,000

allowance is analogous to the £4,000 employment allowance in NICs.

Despite its name, the levy has very little meaningful connection with

apprenticeships (much like NICs have little link with benefits), determining only (in

England) whether the government funds 100% (for levy-paying employers) or 95%

(for non-levy-paying employers) of apprenticeship training costs up to certain

limits.

Only about 2% of employers have a wage bill high enough for them to pay the levy,

but they employ a majority of all employees. The tax is forecast to raise £2.9 billion

in 2021–22.

2

OTS (2016), The closer alignment of income tax and national insurance and OTS (2016), Closer

alignment of income tax and national insurance: a further review, both available from

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ots-publishes-further-report-on-the-closer-alignment-

of-it-and-nics.

17

ã The Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2021

Who pays NICs?

The majority of NICs revenue – an estimated 58% in 2021–22 – comes from

employer contributions. Employee contributions provide a further 39%.

Contributions made by the self-employed (comprising both Class 2 and Class 4

contributions) are a relatively small source of revenue, accounting for less than

2.5% of contributions. That reflects a combination of the much smaller numbers of

self-employed people, their lower average earnings and the lower NICs charged on

their earnings.

Forecast revenue from National Insurance contributions in Great Britain by

source, 2021–22

Note: The chart excludes Northern Ireland. Self-employed contributions include Class 2 and

Class 4 NICs; employer contributions include secondary Class 1, Class 1A and Class 1B

NICs.

Source: Government Actuary’s Department (2021), ‘Report to Parliament on the 2021 re-

rating and up-rating orders’, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/report-to-

parliament-on-the-2021-re-rating-and-up-rating-orders.

Employee

NICs

£55.7bn,

39.2%

Employer

NICs

£82.7bn,

58.2%

Self-employed

NICs

£3.5bn, 2.4%

Voluntary Class 3

NICs

£0.1bn, 0.1%

18

ã The Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2021

A key question is the economic incidence of NICs: who ultimately bears the

burden, in the sense of having their living standards reduced by the tax.

The economic incidence of a tax must always ultimately be on real people. When a

tax is paid by businesses, as with employer NICs, it could be felt by the firm’s

owners/shareholders (via reduced profits from the business) or could be passed on

to the firm’s workers (via lower wages), customers (via higher prices) or suppliers

(via lower input prices). In practice, it will almost always be a combination of these.

Simple economic theory suggests that the incidence of employer NICs and

employee NICs should be the same, at least in the long run. It is likely that the long-

run incidence of both employer and employee NICs is predominantly on

employees, but the empirical evidence is not clear-cut.

More about the incidence of NICs

Employers care about the total cost of employing someone (including tax); employees care

about their take-home (after-tax) income. Neither cares how much of the wedge in between

is labelled as an ‘employer’ versus an ‘employee’ tax. So if employee NICs are increased

and employer NICs reduced, or vice versa, the laws of supply and demand for labour should

ensure that gross earnings adjust to keep labour cost and net earnings unchanged. Such an

adjustment may take time, however, and evidence

3

from past NICs reforms in the UK

suggests it does not happen within a year or so of any reform.

Even if the incidence of employee and employer NICs is the same, that does not necessarily

imply that the burden of employer NICs is fully passed on to the worker. The reverse is also

possible: that at least part of the burden of employee NICs (and indeed income tax) is

passed on to the employer’s owners or customers rather than being felt by the employee in

lower net earnings, if gross wages are higher than they would be in the absence of employee

NICs. Similarly, the burden of self-employed NICs (and the benefits of being taxed more

lightly than employment) might partly be felt by the business’s customers and suppliers, not

just the self-employed people themselves.

3

See S. Adam, D. Phillips and B. Roantree (2019), ‘35 years of reforms: a panel analysis of the

incidence of, and employee and employer responses to, social security contributions in the UK’,

Journal of Public Economics, 171, 29–50, https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/13131.

19

ã The Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2021

Conventional wisdom among economists is that the incidence of employer and employee

NICs will be the same in the long run, and is likely to be predominantly on employees.

However, the empirical evidence on how far – and how quickly – earnings adjust so that

employer and employee taxes really do have the same effects in practice, and on how far

their burden falls on employees versus others, is mixed and hotly debated.

4

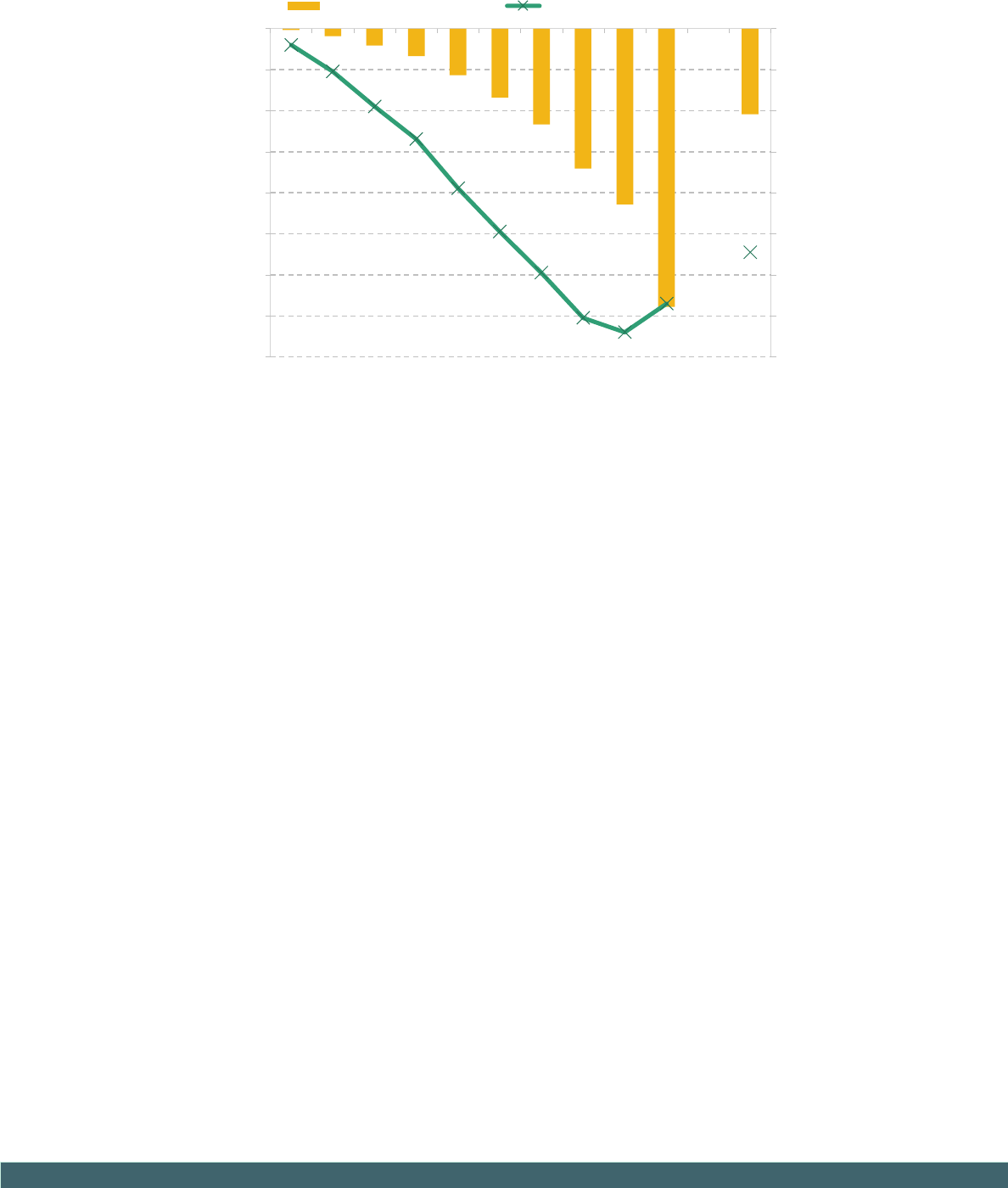

The chart below shows the distributional impact of NICs under the simple

assumption that all NICs – employee, employer and self-employed – are fully

incident on the worker whose earnings are taxed.

It shows the impact on overall household incomes, taking into account, for

example: the extent to which high earners tend to live together; that the impact of

NICs on many low-income households is cushioned as their reduced net earnings

result in higher entitlements to means-tested benefits; and that if (as we assume)

employers pay lower wages as a result of having to pay employer NICs, those lower

wages reduce the amount of income tax employees must pay.

On average, NICs reduce household incomes in the UK by about £4,200, equivalent

to over a tenth of their average income. The chart shows that higher-income

households pay much more, not only in cash terms but as a percentage of their

income – except that NICs reduce the incomes of the highest-income tenth of

households by a smaller proportion than the 8

th

or 9

th

decile groups, because of the

fall in marginal NICs rates above the UEL and UPL.

4

Ibid.

20

ã The Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2021

The distributional impact of National Insurance contributions

Note: The chart assumes all NICs are incident on the worker whose earnings are taxed.

Households are divided into 10 equal-sized groups based on their net income adjusted for

household size using the Modified OECD equivalence scale.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the IFS tax and benefit microsimulation model, TAXBEN,

run on uprated data from the 2018–19 Family Resources Survey.

-16%

-14%

-12%

-10%

-8%

-6%

-4%

-2%

0%

-£16,000

-£14,000

-£12,000

-£10,000

-£8,000

-£6,000

-£4,000

-£2,000

£0

Poorest 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Richest All

Income decile group

£ per year (left axis) % of net income (right axis)