THE LONG-TERM DECLINE IN

PRIME-AGE MALE LABOR FORCE

PARTICIPATION

June 2016

1

Contents

Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 2

Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 5

I. U.S. Prime-Age Male Labor Force Participation in Historical and International Context .......................... 7

II. Prime-Age Male Participation by Demographic ...................................................................................... 11

Age and Birth Cohort .............................................................................................................................. 11

Race and Ethnicity ................................................................................................................................... 12

Education ................................................................................................................................................ 13

Family, Immigration, and Other Factors ................................................................................................. 14

III. Assessing Explanations of the Decline in Prime-Age Male Participation Rates: Supply, Demand, and

Institutions .................................................................................................................................................. 16

Supply-Driven Explanations .................................................................................................................... 17

Alternative Sources of Income ............................................................................................................ 17

Spousal Income ................................................................................................................................... 18

Government Transfers Including Disability Insurance ........................................................................ 19

Alternative Use of Time ...................................................................................................................... 23

Poverty and the Well-being of Men Not Participating in the Workforce ........................................... 25

Demand-Driven Explanations ................................................................................................................. 26

Demand for Less-Skilled Labor ............................................................................................................ 27

Wages and Inequality .......................................................................................................................... 28

Institutional Explanations ....................................................................................................................... 30

U.S. Labor Market Institutions in International Context..................................................................... 30

Incarceration and Criminal Records .................................................................................................... 32

The Changing Pattern of Labor Markets: Rising Cyclicality and Declining Fluidity ............................. 34

IV. Policies that Can Boost Labor Force Participation for Prime-Age Men ................................................. 37

Supporting Aggregate Demand in the Economy..................................................................................... 37

Increasing “Connective Tissue” in the Labor Market .............................................................................. 38

Reforming Federal Tax Provisions ........................................................................................................... 39

Creating Flexibility for Workers in the Labor Market ............................................................................. 40

Other Steps: Raising Educational Attainment, Reforming the Criminal Justice System and Passing

Commonsense Immigration Reform ....................................................................................................... 41

Reducing Inequality ................................................................................................................................ 42

V. Conclusion ............................................................................................................................................... 43

References .................................................................................................................................................. 44

2

Executive Summary

For more than sixty years, the share of American men between the ages of 25 and 54, or “prime-

age men,” in the labor force has been declining. This fall in the prime-age male labor force

participation rate, from a peak of 98 percent in 1954 to 88 percent today, is particularly troubling

since workers at this age are at their most productive; because of this, the long-run decline has

outsized implications for individual well-being as well as for broader economic growth. A large

body of evidence has linked joblessness to worse economic prospects in the future, lower overall

well-being and happiness, and higher mortality, as well as negative consequences for families

and communities.

This report documents the trend of declining prime-age male labor force participation over the

last half century in both a historical and international context, examines a number of potential

explanations, and discusses the policies President Obama has proposed to address it.

Labor force participation among prime-age men peaked in 1954 and has fallen steadily since

the mid-1960s, a trend that has been sharper in the United States than in other advanced

economies.

• Participation among prime-age men peaked in 1954, declined only slightly until the mid-

1960s, and then began to decline in earnest in the decade between 1965 and 1975. Since

then, participation has fallen persistently, with sharper declines in recessionary periods that

were not fully reversed in the subsequent expansions.

• Since 1965, the prime-age male labor force participation rate has fallen by an average of 0.16

percentage point each year, totaling an 8.3 percentage-point decline as of May 2016.

• The United States has had the second largest decrease in prime-age male participation among

members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) since

1990; today, the United States has the third lowest labor force participation rate in this group.

The fall in participation for prime-age men has largely been concentrated among those with a

high school degree or less, and participation rates have declined more steeply for black men.

• Participation rates by educational attainment, previously quite similar, have diverged since

the 1960s. In 1964, 98 percent of prime-age men with a college degree or more participated

in the workforce, compared to 97 percent of men with a high school degree or less. In 2015,

the rate for college-educated men had fallen slightly to 94 percent while the rate for men

with a high school degree or less had plummeted to 83 percent.

• Lower rates of labor force participation have affected all races and ethnicities, although

participation has declined most steeply and remains lowest for prime-age black men.

• Participation at nearly every age has fallen for nearly every consecutive cohort of men,

meaning that falling participation among prime-age men is largely a function of lower

participation at all ages rather than shocks at a particular age or for a particular birth cohort.

3

Reductions in labor supply—in other words, prime-age men choosing not to work for a given

set of labor market conditions—explain relatively little of the long-run trend.

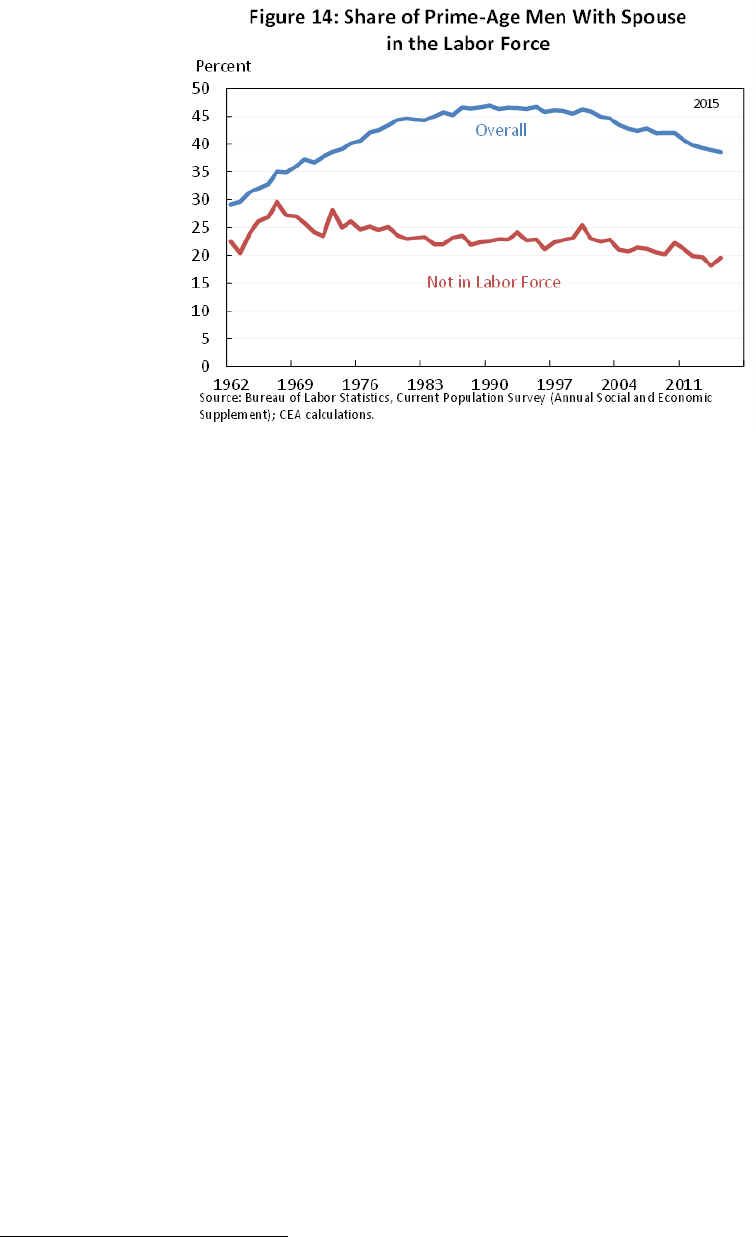

• Less than a quarter of prime-age men who are not in the workforce have a working spouse,

and that figure has actually decreased during the last 50 years.

• The data suggest that public assistance can explain very little of the decline in labor force

participation rates for prime-age men:

o Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) receipt has increased by 2 percentage points

since 1967 compared to a 7.5 percentage-point decline in prime-age male labor force

participation rates over that period. Moreover, not all of this increase in SSDI causally

lowers participation. CEA analysis finds that increasing SSDI receipt can explain at

most 0.5 percentage point of the decline over this period, under a counterfactual

scenario that likely provides an upper-bound estimate.

o Other government programs, such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

(TANF) and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) have become

increasingly hard to access for those out of work and especially those without

children.

• Nearly 36 percent of prime-age men not in the labor force lived in poverty in 2014—casting

doubt on the hypothesis that nonparticipation represents a choice enabled by other personal

means or income sources.

In contrast, reductions in the demand for labor, especially for lower-skilled men, appear to be

an important component of the decline in prime-age male labor force participation.

• Participation has fallen particularly steeply for less-educated men at the same time as their

wages have dropped relative to more-educated men, consistent with a decline in demand.

o In recent decades, less-educated Americans have suffered a reduction in their wages

relative to other groups. From 1975 until 2014, relative wages for those with a high

school degree fell from over 80 percent of the amount earned by workers with at least

a college degree to less than 60 percent.

• CEA analysis using State-level wage data suggests that when the returns to work for those at

the bottom of the wage distribution are particularly low, more prime-age men choose not to

participate in the labor force:

o The correlation is strongest at the bottom of the wage distribution: at the 10

th

percentile, a $1,000 increase in annual wages, or a roughly $0.50 increase in hourly

wages for a full-time, full-year worker, is associated with a 0.13 percentage-point

increase in the State participation rate for prime-age men.

• This reduction in demand, as reflected in lower wages, could reflect the broader evolution of

technology, automation, and globalization in the U.S. economy.

4

Institutional factors also appear to be important—and may help explain some of the

differences in the U.S. experience both over time and compared to other countries.

• Conventional economic theory posits that more “flexible” labor markets—where it is easier

to hire and fire workers—facilitate matches between employers and individuals who want to

work. Yet despite having among the most flexible labor markets in the OECD—with low levels

of labor market regulation and employment protections, a low minimum cost of labor, and

low rates of collective bargaining coverage—the United States has one of the lowest prime-

age male labor force participation rates of OECD member countries.

• U.S. labor markets are much less “supportive” than those in other OECD countries. The United

States spends 0.1 percent of GDP on so-called “active labor market policies” such as job-

search assistance and job training that help keep unemployed workers connected to the labor

force, much less than the OECD average of 0.6 percent of GDP, and less than nearly every

other OECD country. The contrast in participation rates reveals a flaw in the standard view

about the tradeoffs between flexibility and supportive labor policies.

• Another unique feature of the U.S. experience has been the rapid rise in incarceration,

especially affecting low-skilled men.

o By one estimate, between 6 and 7 percent of the prime-age male population in 2008

was incarcerated at some point in their lives.

o These men are substantially more likely to experience joblessness after they are

released from prison and in many States are legally barred from a significant number

of jobs.

A number of policies proposed by the Administration would help to boost prime-age male labor

force participation. These include:

• Supporting aggregate demand in the economy by creating new job opportunities for less-

educated prime-age men, including increased investment in public infrastructure.

• Increasing the “connective tissue” in labor markets via reforming community college and

training systems to help place people into in-demand jobs; providing better search assistance

as part of the Unemployment Insurance system; giving workers more flexibility to use

Unemployment Insurance to integrate into a new job; and insuring workers against earnings

losses.

• Reforming the U.S. tax system to make participation in the workforce easier by reducing the

effective tax penalty on secondary earners and expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit for

individuals without qualifying children.

• Creating greater flexibility for workers by expanding access to paid family leave and paid sick

days and by increasing assistance for child care and early-learning programs.

• Systemic reforms, including investing in education and reforming the criminal justice and

immigration systems.

• Increasing wages for workers by raising the minimum wage, supporting collective bargaining,

and ensuring that workers have a strong voice in the labor market.

5

Introduction

The share of men between the ages of 25 and 54 either working or actively seeking work, also

known as the prime-age male labor force participation rate, has been falling for more than 60

years and today stands at 88 percent.

1

When individuals are in their prime working years, they

are at their most productive; as a result, their labor force participation has outsized implications

for broader economic growth, as well as for individuals’ earnings prospects and well-being. These

prime years are when salaries peak, allowing these men and their families to consume goods and

services, invest in their children, and save for their retirement. This decline is one part of a more

recent, broader set of trends in labor force participation that include more recent declines for

prime-age women, increased participation at older ages, and the aging of the Baby Boom

cohort—all of which are examined in an earlier report by the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA

2014a).

Some of the decline in labor force participation among prime-age men may reflect the

improvement in their options outside the labor force. For example, some of these men may be

happier staying home as caregivers, going to school, or retiring early. As this report discusses,

however, much of the long-run decline in prime-age male labor force participation may reflect a

concerning trend of reduced labor market opportunities. This includes both difficulty re-entering

the labor market following recessions and a perceived or real lack of demand for the skill sets of

certain prime-age men. Men who do not participate in the labor force for these more problematic

reasons may experience a number of negative consequences that affect not only themselves, but

also their families and communities.

While no definitive studies link nonparticipation with broader outcomes, to the extent that

nonparticipating individuals have become so discouraged about the prospects of finding work

that they do not participate, it is reasonable to expect that many of the documented effects of

unemployment beyond the simple loss of income extend to nonparticipation. Unemployment

has been found to increase mortality, largely from increased likelihood of suicide and alcohol-

related deaths (Eliason and Storrie 2009; Gerdtham and Johannesson 2003). Job loss is connected

to higher rates of smoking initiation for non-smokers and increased body weight (Marcus 2014;

Black, Devereux, and Salvanes 2015). Unemployment is also associated with lower overall well-

being and reported happiness (Winkelmann and Winkelmann 1995; Knabe and Ratzel 2011;

Lucas et al. 2001) that can last even after reemployment (Lucas et al. 2004). Lack of employment

has been shown to have scarring impacts on entire communities, as these phenomena have been

linked to rising crime rates (Raphael and Winter-Ebmer 2001; Gould et al. 2002; Lin 2008). For

parents, job loss is associated with negative consequences for children, including lower school

performance in the short term and earnings losses and increased reliance on Unemployment

Insurance and social assistance in the long term (Rege, Telle and Votruba 2011; Oreopoulos, Page

and Stevens 2008).

1

In this report the “labor force participation rate” and other labor market variables are all for men between the ages

of 25 and 54 unless explicitly specified otherwise.

6

It is also important to note that the decision to participate in the labor force is not a static one.

When workers are not employed, this has implications for their future employment prospects as

well. One of the best predictors of future unemployment is past history of unemployment

(Arulampalam et al. 2001; Arulampalam et al. 2000). Absence from the labor force may mean

that critical skills atrophy or are never acquired, making work in later years less likely and less

productive, ultimately lowering the trajectory of lifetime wages and earnings. Lack of labor force

attachment may also sever or inhibit ties to the networks of firms and fellow workers that ease

employment transitions and make higher-wage jobs easier to find.

The stark increase in nonparticipation among prime-age men and the potential consequences for

these men and their families makes understanding the drivers of this development important to

both economists and policymakers. Understanding prime-age male participation trends can also

potentially shed light on the recent decline in participation among prime-age women given the

converging roles of women and men in and outside of the workplace. After first reviewing trends

in prime-age male labor force participation over time and relative to other industrialized nations,

this report considers three categories of explanations for the decline in labor force participation

among prime-age men.

We first examine whether improved options for prime-age men outside the labor force, namely

alternative sources of income and alternative uses of time, could be motivating these men to

leave the labor force. These supply-driven explanations cannot fully or consistently explain the

growth in nonparticipation over time. We then consider whether falling demand for the labor

services of the prime-age men leaving the labor force could explain their nonparticipation,

drawing on both a significant body of existing research as well as new CEA analysis. Because

falling prime-age male participation rates have been accompanied by declining wages among

less-educated men, who are most likely to not participate, the available evidence appears more

consistent with the decline in demand for the labor services of low-skilled men rather than

supply-side explanations being the net driver. Finally, we also consider institutional reasons for

the decline in prime-age male labor force participation, drawing on international comparisons to

understand the role of policy choices that lead to higher nonparticipation rather than higher

unemployment and how the changing structure of the labor market stymies labor force

participation.

Although further research is needed to more precisely understand the full set of explanations

and their comparative importance, there are policy measures that can help address declining

labor force participation among prime-age men both by boosting demand for their labor

services—particularly those with less education—as well as enhancing their skill sets and better

connecting them to work opportunities. We close by describing how some of the Administration’s

policies would affect the participation of prime-age men in the workforce.

7

I. U.S. Prime-Age Male Labor Force Participation in Historical and

International Context

The share of men between the ages of 25 and 54 either working or actively seeking work has

been falling for more than 60 years. The decline in participation has been roughly constant over

much of this time horizon. As Figure 1 shows, participation among prime-age men peaked in

1954, declined only slightly until the mid-1960s, but then began to decline in earnest in the

decade between 1965 and 1975, when the share in the labor force fell from 96.7 percent to 94.2

percent. Since then, participation has fallen persistently, with sharper declines in recessionary

periods, such as the early 1990s, that were not fully reversed in the subsequent expansion

periods. Since 1965, the prime-age male labor force participation rate has fallen by an average

of 0.16 percentage point each year, totaling an 8.3 percentage-point decline as of May 2016.

During the Great Recession, the rate of labor force participation among prime-age men fell

steeply, falling from 91.5 percent in January 2007 to 87.9 percent at its trough in October 2013.

Since October 2013, prime-age male participation has stabilized, remaining between 88.0 and

89.0 percent (inclusive) but like prior recessions, participation did not fully recover to pre-

recessionary rates.

In addition, a large majority of the men who reported they are not in the labor force in a given

month also reported that they did not work at all in the previous year. Moreover, this intensity

of nonparticipation has increased over time, which indicates a decline in labor force attachment.

In 2015, 83 percent of prime-age men in the Current Population Survey who were not

participating in the labor force in the reference week had not worked at all in the previous year,

up from 73 percent in 1988, the first year for which data on this question are available (see Figure

2).

2

2

Where CPS Annual Social and Economic Supplement data are used in this report, the data are presented as far back

as possible given the variables used in the analysis.

8

Juhn, Murphy, and Topel (2002) emphasize the large increase in male nonemployment from

individuals out of work all 12 months of the year, especially for less-educated males. New work

by Coglianese (2016) also shows a rise in 12-month nonemployment, in addition to an equally

large rise in part-year nonemployment.

Not only has labor force participation among prime-age men declined over the past six decades,

since 1990, the United States has had the second-largest decrease in prime-age male

participation among member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD). Of the OECD, the United States now ranks 3

rd

lowest out of 34, as shown

in Figure 3—above only Italy and Israel—in terms of prime-age male labor force participation,

compared to 10

th

lowest out of 24 in 1990.

9

The decline in U.S. labor force participation relative to much of the OECD, however, is only part

of the story, and on its own overstates the problem of nonemployment in the U.S. economy.

Labor force nonparticipation is just one of two ways in which individuals can be non-employed;

they can also be unemployed, which means they are currently seeking employment. More

broadly, depending on the incentives created by unemployment support programs, training

systems and other initiatives, workers may choose to remain attached to the labor force but

unemployed, or working part time, rather than leaving the labor force. Although the United

States has particularly low prime-age male labor force participation, the United States has also

historically had a lower unemployment rate – the share of the labor force that is unemployed—

relative to other OECD economies (see Figure 4). Moreover, our current unemployment rate is

relatively similar to its past values—while in many other OECD countries it is elevated, in many

cases because they are less far along in their cyclical recoveries from the Great Recession and

Euro Zone crisis.

But lower rates of unemployment among prime-age men only partially offset relatively higher

nonparticipation rates in the United States, leaving the U.S. prime-age male nonemployment

rate—the share of prime-age males that are not employed, a potentially more comparable

measure across countries—below the median of OECD member countries (see Figure 5).

Moreover, the U.S. nonemployment rate has also declined, meaning that a smaller share of

prime-age men are contributing directly to output today than in years before. Also, because many

other OECD economies experienced slower recoveries than the United States, their

nonemployment rates are potentially temporarily higher than they would otherwise be, leaving

the United States higher ranked in the distribution on a structural basis. Finally, given that the

unemployed report searching for work, a greater share of nonemployed who are

nonparticipating rather than unemployed may predict lower reemployment rates in the future.

10

11

II. Prime-Age Male Participation by Demographic

Although prime-age male labor force participation has fallen among all demographic groups, it

has fallen noticeably more for those who belong to younger birth cohorts and those who are

black, less educated, nonparents, native-born, living in the South, and veterans. However, as

described below, the changing demographics of prime-age men do not explain the long-run

decline in participation; in fact, trends such as rising educational attainment should have, all else

equal, actually led to increases in participation.

Age and Birth Cohort

Participation changes over the lifecycle: as men of the same birth cohort age, participation rises

into the early 30s, where it tends to peak and then declines steadily through age 54, as shown in

Figure 6. Labor force participation rates at nearly every age has fallen for nearly every cohort of

men, although the pattern of participation has changed somewhat with less of a falloff in

participation rates in their 30s for men born more recently. These patterns suggest that falling

participation among prime-age men is largely a function of lower labor force participation at all

ages among later cohorts rather than shocks to participation concentrated at some ages for

particular cohorts. Importantly, this means that no particular generation or moment in time was

solely or even primarily responsible for the overall decline.

The age composition of the entire population 16 and older has had a large impact on the overall

participation rate. For example, the majority of the decline in the overall participation rate since

2007 is explained by the higher fraction of workers over 55 years old, who are less likely to

participate than younger workers. But changing age demographics do not explain the changes in

the participation rate for prime-age men themselves in recent decades, as shown in the “shift-

share” analysis in Figure 7. The “share” region shown in orange is what would have happened to

participation rates if people at every age had the same participation rates but the age structure

1933-1942

1943-1952

1953-1962

1963-1972

82

84

86

88

90

92

94

96

98

100

25 27 29 31 33 35 37 39 41 43 45 47 49 51 53

Figure 6: Prime-Age Male Labor Force Participation

Over the Lifecycle by Birth Cohort

Percent

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey (Annual Social and Economic

Supplement); CEA calculations.

Age

1973-1982

1983-1992

12

changed. As the first Baby Boomers moved into their 30s and 40s in the 1970s and 1980s this

should have provided a modest boost to the participation rate of prime-age men, while the

corresponding aging of the group should have resulted in a modest decline in their participation

rate. These changes, however, are dwarfed by the “shift” region shown in blue that shows what

happened to changes in participation rates for given age groups—in this case showing the

relatively steady decline. By construction, these two regions sum to the actual changes in the

participation rate, shown in the solid black line.

Race and Ethnicity

Black prime-age men have historically participated at lower rates than white or Hispanic men,

and this gap has grown, as shown in Figure 8. Although in the past Hispanic prime-age men

participated at lower rates than white prime-age men, this gap has reversed in recent years. The

convergence occurred as Hispanic prime-age men’s labor force participation has been roughly

stable over the past 20 years, while participation among prime-age white men has declined.

-0.4

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

1972 1977 1982 1987 1992 1997 2002 2007 2012

Due to Changes in Participation Within Age Groups

Due to Changes in the Age Distribution

Overall Change

Figure 7: Decomposition of Ten-Year Changes

in Prime-Age Male Labor Force Participation Rate by Age

Percentage

Points per Year

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey (Annual Social and Economic

Supplement): CEA calculations.

2014

13

Education

In 1964 participation rates were similar for different education levels—with 98 percent of prime-

age men with a college education participating in the workforce as compared to 97 percent of

prime-age men with a high school degree or less, as shown in Figure 9. In 2015, every education

group had lower participation rates than in previous decades, but the decline was modest for

more-educated workers. In contrast, those with a high school degree or less saw their

participation rates fall to 83 percent, a 14 percentage point reduction from 1964.

This increasingly steep education gradient for participation compounds the puzzle of the long-

term decline in the participation rate. Over this same period, the percentage of prime-age men

with a high school degree or less fell from 76 percent to 41 percent while the percentage of

High School or Less

Some College

Bachelor's or More

80

82

84

86

88

90

92

94

96

98

100

1964 1974 1984 1994 2004 2014

Figure 9: Prime-Age Male Labor Force Participation

by Educational Attainment

Percent

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey (Annual Social and Economic

Supplement); CEA calculations.

2015

14

prime-age men with a college degree rose from 14 percent to 33 percent. If participation rates

had stayed constant for each education group, the analysis in Figure 10 estimates that the

increase in educational attainment would have resulted in a 2.5 percentage-point increase in the

labor force participation rate over this period, instead of the 9.0 percentage-point decrease

actually seen. The shift-share analysis in Figure 10 below generalizes this point. The “share”

region in orange shows the change in labor force participation rates predicted from the increased

educational attainment of prime-age men—assuming each education group had an unchanged

participation rate. The “shift” region in blue shows changes in labor force participation within

each education group. The solid black line tracks the actual labor force participation rate over

time and by construction is the sum of the “share” and “shift” terms. As shown in the figure rising

educational attainment, especially in the 1970s and 1980s, should have raised labor force

participation rates—but declines in participation for each education group outweighed this and

lowered them instead.

Family, Immigration, and Other Factors

Participation rates have fallen for both parents and nonparents alike, but prime-age males

without children saw a larger decline of 9.4 percentage points since 1968 compared to 4.9

percentage points among prime-age males with children. This suggests that men dropping out of

the labor force to be stay-at-home fathers is likely not an important factor in the overall decline;

moreover, only around a quarter of prime-age men who are not in the labor force are parents

(down from around 40 percent in 1968).

Foreign-born prime-age men continue to participate at higher rates than the native-born. Their

participation rate has actually risen slightly over the last two decades by 1.4 percentage point

since 1994, while the native-born prime-age male participation fell by 4.4 percentage points,

suggesting that increasing immigration is not a viable explanation for the decline.

-0.4

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

1974 1979 1984 1989 1994 1999 2004 2009

2014

Due to Changes in Participation Within Education Groups

Due to Changes in Educational Attainment

Overall Change

Figure 10: Decomposition

of Ten-Year Changes

in Prime-Age Male Labor Force Participation Rate

by Educational Attainment

Percentage Points per Year

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey (Annual Social and Economic

Supplement): CEA calculations.

2014

15

Among all groups, participation rates are generally higher in the West and Midwest regions and

lowest in the South. Finally, although veteran participation has fallen by more than for the overall

prime-age male population, the share of nonparticipating prime-age men who are veterans has

declined, suggesting that this is not a key factor in the overall decline.

One factor we cannot assess in the data is trends in unreported or under-the-table work.

Presumably some of the men classified by the Current Population Survey as out of the workforce

are still earning money but not reporting it to surveyors. There is little way to tell the extent of

this or if it has risen over time. Some research finds that the share of the economy comprised by

the shadow economy has likely stayed constant or shrunk over time, suggesting that there has

not been an increasing role of unreported income from the shadow economy for prime-age men

(Schneider 2012). Moreover, a range of other data sources, including the time use surveys

discussed below, corroborate that there has been an overall real and large increase in the

percentage of prime-age men out of the workforce—something that could not be explained away

reported measures of under-the-table work.

16

III. Assessing Explanations of the Decline in Prime-Age Male

Participation Rates: Supply, Demand, and Institutions

The steady decline in labor force participation among prime-age men since the 1950s has been

larger than in most other OECD countries. This decline is not explained by the changing age

structure of the population and is especially puzzling in light of the increased educational

attainment of the population. The question then is what does explain the magnitude and timing

of the decrease and why it is larger than what other countries have experienced. This report

evaluates three different classes of explanations: supply driven (or an inward shift of the labor

supply curve), demand driven (or an inward shift of the labor demand curve), and institutional.

Figure 11 below details how inward shifts of the supply and demand curve affect both equilibrium

wages and employment. In the diagram on the left, the inward shift of the supply curve moves

the equilibrium up the demand curve, leading to a reduction in employment (and consequently

participation if all else remains constant), but an increase in wages. In contrast, in the diagram

on the right, the demand curve shifts inward and the equilibrium moves down the supply curve,

resulting in less employment and lower wages. Institutional factors will determine how shifts of

either curve are realized in terms of speed and ultimate impact.

Drawing on this framework and considering different forces that could shift the supply or demand

curves, we find that reductions in supply, or men choosing not to work for a given set of labor

market conditions, explains relatively little of the trend, while reductions in demand, especially

for less skilled workers, may be an important part of the story—and also explain the decline in

relative wages for this group. Finally, institutional factors appear to be important—and may help

explain some of the differences in the U.S. experience both over time and compared to other

countries.

17

Supply-Driven Explanations

As shown in Figure 12, the share of nonparticipating prime-age men reporting they want a job

has fallen over time, from a peak of 28 percent in 1985 to 16 percent in 2015. This suggests that

at least a portion of the increase in nonparticipation stems from men deciding that they do not

want to work, at least in the jobs available to them. This, however, could reflect a shift in the

supply curve or a movement along the supply curve, depending on the underlying causes.

This section examines a number of factors that may be affecting the decisions of prime-age men

to participate in the workforce. We first examine whether increases in the income available to

prime-age men outside of work may have led them to leave the labor force—showing that prime-

age men who are not in the labor force are increasingly less likely to have a working spouse, that

disability insurance has risen much less than participation rates have declined, and that other

forms of public assistance have fallen. The section then examines whether prime-age men leave

the labor force to spend their time in other productive ways, such as household production or

education, finding that this does not appear to explain the change.

Alternative Sources of Income

The rise of nonparticipation raises the question of how prime-age men not participating in the

labor force support themselves. Figure 13 compares income sources for all prime-age men and

those not in the labor force over time. For prime-age men overall, the bulk of their household

annual income comes from their wages and salaries. Naturally, wage income plays a minor role

for prime-age men not currently in the labor force, though it is not zero, as some have

18

participated in the labor force at some point in the previous calendar year.

3

For the households

of men not in the labor force, other household members’ and spouses’ income are the key

sources of income, comprising more income than their wage income, government income, and

other income

4

combined.

5

Previous research by Stewart (2006) confirms that other household

members (especially family members) and unearned income from other sources are particularly

important in keeping nonworking prime-age men afloat.

Spousal Income

One possible explanation for the decline in prime-age male labor force participation would be if,

as women’s labor force participation rose over the last 50 years, and as women worked more

hours at higher wages, their incomes could potentially make nonparticipation more affordable

for their husbands. However, the data do not support this hypothesis: fewer than a quarter of

prime-age men who are not in the workforce have a working spouse, and that figure has actually

decreased during the last 50 years, notwithstanding the large overall increase in the number of

women who work, as shown in Figure 14. Part of the reason is an increase in what economists

call “assortative mating:” men and women who are successfully employed are increasingly

coupling up with others who are successfully employed, rather than with partners who are not.

3

Individuals are designated not in the labor force if they did not work in the previous week. However, income

questions refer to the previous calendar year. As a result, individuals coded as not participating in the labor force

may have income for the previous year if they had been participating in the labor force at that time.

4

Other income includes income from interest, dividends, rent, alimony, retirement, educational assistance, child

support, and more.

5

It is also important to note that the CPS undercounts benefits. However, there is no indication that underreporting

has changed over time or that it differs by participating status.

19

One might be concerned that falling marriage rates mean that prime-age men not in the labor

force increasingly depend on the labor force participation of a significant other to whom they are

not married, and that the earlier analysis may have missed this. However, even when the analysis

is expanded to include all other household members, the picture is much the same: the share of

nonparticipating prime-age men with a household member in the labor force has fallen over

time, even as it has risen for prime-age men overall. Other researchers have similarly concluded

that reliance on spousal income does not seem to be an explanatory factor in the decline of

prime-age male labor force participation (Juhn and Potter 2006).

Government Transfers Including Disability Insurance

In the early 1970s, cash welfare income was the largest source of government income, on

average, for households with prime-age men not participating in the workforce, but starting in

the mid-1970s cash welfare as a share of government income plummeted and Social Security

6

(including Social Security Disability Insurance, or SSDI) became the top income source. Figure 15

details the breakdown of government income for prime-age men and their spouses in 2014.

Today, Social Security is the largest single source of government income, with 24 percent

receiving benefits versus 3 percent among prime-age men overall. Supplemental Security Income

(SSI), a need-based program that provides support to blind, elderly, and disabled individuals

without a work history, is the second-largest government income source for the households of

nonparticipating prime-age men today, with 15 percent of nonparticipating prime-age men

receiving these benefits.

6

Social Security income includes all benefits from Social Security, including those for retired workers, survivors, and

disabled workers.

20

Disability insurance is another candidate for a supply-side explanation of the decline in prime-

age male labor force participation rates. SSDI receipt rates have been rising among prime-age

men for the last 50 years. Today, 3.3 percent of prime-age men receive SSDI payments. A number

of research papers find that increases in the number of people receiving SSDI led to lower labor

force participation among the general population, especially among veterans (Autor and Duggan

2003; Autor et al. 2015), and to lower earnings (Gelber, Moore, and Strand 2016).

However, from 1967 until 2014, the percentage of prime-age men receiving disability insurance

rose from 1 percent to 3 percent, not nearly enough to explain the 7.5 percentage-point decline

in the labor force participation rate over that period. Moreover, even the 2 percentage-point

increase in SSDI receipt among prime-age men should not be interpreted as the causal impact of

disability insurance on labor force participation for three reasons. First, 0.1 percentage point of

this increase simply reflects the changing age structure of prime-age men who are older than in

the past, which is associated with more SSDI receipt. More importantly, much of the increase in

SSDI may be a consequence of the fact that an increasing number of men do not have jobs and

thus may apply for SSDI when they might not have applied in the past. Finally, many of the men

receiving SSDI would not have participated in the workforce regardless because of their

disabilities.

Figure 16 assesses how much the increase in SSDI

7

receipt could contribute to labor force

participation declines among prime-age men under two counterfactual scenarios, finding that

SSDI increases may have caused 0.3 to 0.5 percentage point of the 7.5 percentage-point decline

in the prime-age male labor force participation rate over this period. The purple line measures

the share of prime-age men receiving Federal Social Security (including SSDI) benefits each year.

The blue line tracks the actual fall of participation among prime-age men since 1968. The green

7

The Current Population Survey does not distinguish between types of Social Security income. We use Social Security

income as a proxy for SSDI.

21

line tracks the participation rate that would have resulted if all SSDI recipients (who participated

at a rate of 15 percent in 2014) participated at the same rate as the average among individuals

who self-identify as disabled but who do not receive SSDI (33 percent in 2014), adjusting for

changes in the age distribution. This counterfactual likely overstates the participations rates of

this population in the absence of SSDI, since it implies that work ability is equal for SSDI recipients

and disabled individuals not receiving SSDI. Of course, some individuals who are disabled but are

not receiving SSDI may not be participating as they plan to apply for SSDI. Nonetheless, if SSDI

recipients are less able to work on average than the disabled, the true counterfactual would be

even lower than the green line.

The assumption underlying the green line—that SSDI recipients would participate at the same

rates as disabled workers not receiving SSDI—has only a minor impact on the participation rate.

Under this assumption, the participation rate among prime-age men would have fallen by 7.2

percentage points between 1967 and 2014 instead of the actual decline of 7.5 percentage

points—a difference of just 0.3 percentage point. In other words, other forces besides the rise in

SSDI receipt are needed to explain the decline of prime-age male labor force participation.

Another approach to quantify the potential role of SSDI in participation declines is to use

economic literature to identify the causal impact of SSDI receipt on labor force participation

decisions and use that to estimate the aggregate effect of changing SSDI on labor force

participation. The red line assumes that SSDI reduces labor force participation rates by 26

percentage points (French and Song 2014) to better predict how many SSDI recipients not in the

labor force would participate in the absence of SSDI benefits. One limitation of this estimate is

that the study examined the impact of SSDI on participation overall, not prime-age men

specifically. This counterfactual implies that fewer SSDI recipients would rejoin the labor force if

they did not receive SSDI, particularly prior to the mid-1990s, than the green line suggests. In

fact, this research-based prediction suggests the participation rate would have fallen by only 0.5

percentage point less between 1967 and 2014, leaving 7.0 percentages points of the actual 7.5

percentage-point decline over this period unexplained. So while SSDI receipt’s impact on prime-

age male labor force participation is negative, under reasonable assumptions it is small and

cannot explain more than a portion of the overall decline in participation.

22

The increase in disability insurance therefore explains, at most, a small fraction of the decline in

the labor force participation rate for prime-age men. At the same time, other government

programs have become increasingly hard to access. To the extent that access to benefits would

reduce incentives to participate, this would suggest increasing participation over this time period.

However, the opposite has been happening. Figure 17 shows the percentage of prime-age men

who receive government transfers other than Social Security, with the main transfers being TANF

(Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, formerly known as Aid to Families with Dependent

Children) and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, previously known as food

stamps). While it is higher than prime-age men over all, it has been declining over this time

period.

23

The decline in benefits has been particularly large for people without a job, as many State

governments established stricter eligibility standards for Unemployment Insurance, and the

Federal and State governments have cut spending on traditional cash welfare payments.

Meanwhile, few nonworking, able-bodied adult men without children are now eligible to receive

nutritional assistance. Changes in government aid thus cannot explain the drop in prime-age male

labor force participation.

Alternative Use of Time

One hypothesis described earlier is that men are choosing to stay home and participate more in

household work and childcare. Academic research has documented that, in the 1980s when

women’s labor force participation increased dramatically, household work remained highly

unevenly allocated between men and women (Blau 1998). However, time use data show that

fathers are more likely to share the household task burden than in the past, with total time spent

on child care and housework rising from 6.9 hours per week in 1965 to 16.4 hours per week in

2013 (CEA 2014b).

To understand how men out of labor force spend their time and whether they are staying home

to help with home production, we make use of data from the American Time Use Survey. Table

1 reports the average number of minutes per day spent on various activities in 2014 by all prime-

age men as well as by prime-age men not in the labor force. Based on this time use data, there

is little evidence that men are staying home to care for children or to do house work. As the table

shows, prime-age men not in the labor force spend about the same amount of time as all prime-

age men caring for household members. Nonparticipating prime-age men also do not spend

meaningfully more time caring for non-household members, an activity on which all groups

spend an average of less than 10 minutes per day. Prime-age men not in the labor force do spend

more time, approximately 26 additional minutes per day, engaged in household activities and

services than prime-age men overall.

8

These findings confirm previous research describing the

time use of nonworking men (Stewart 2008).

One might expect differing patterns for married and non-married men, as married men are better

able to specialize in household production while their spouse works. However, nonparticipating

prime-age men spent time fairly similarly across most time use categories regardless of whether

they were married or single. This includes household activities, on which unmarried men spent

108 minutes per day while married men spent 112 on average. When we examine men with

children, we find that, although nonparticipating prime-age men with children spend more time

caring for household members (73 minutes) than prime-age men with children overall (58

minutes), the difference amounts to less than an additional half-hour per day. Further, prime-

8

Household activities are activities done to maintain a household, including housecleaning, cooking, yard care, pet

care, vehicle maintenance and repair, and home repair and renovation. Household management activities—such as

paperwork, mail, and email—are also included in this category. Household services refer to obtaining and purchasing

household services provided by someone else. Household services include yard and house cleaning, cooking, pet

care, tailoring and laundering services, and vehicle and home repairs, maintenance, and construction. Watching

someone else perform paid household activities (cooking, cleaning, repairing, etc.) would be coded here.

24

age men out of the labor force with children only spent 11 additional minutes on non-child care

household activities compared to non-parents. Taken together with existing literature on the

subject, time use patterns suggest that substitution of husband’s time for wife’s time within the

household does not appear to be the key to understanding recent trends in labor force

participation among prime-age men (Juhn and Potter 2006; Blau 1998).

Table 1: Time Use Breakdown in 2014 for Prime-Age Men Overall

and Nonparticipating Prime-Age Men

Time Use Category

Time Spent (Minutes Per Day)

Prime-Age Men

Prime-

Age Men,

Not in the Labor Force

Caring for Household Members

29

28

Caring for Non-Household Members

7

8

Education

8

25

Household Activities and Services

84

111

Socializing, Relaxing, Leisure

251

472

Watching Television

154

335

Work

316

7

Other (Including Sleep)

736

773

Note: Columns do not sum to 1,440 minutes per day because some individuals do not report all minutes of each day.

Source: American Time Use Survey; CEA calculations.

The data also suggest that men are not choosing to leave the labor force to invest in their skills

and better their future labor market opportunities. Prime-age men not in the labor force spent

only 17 minutes more per day on educational activities than prime-age men overall, with the

unmarried and childless accounting for much of the difference.

9

Interestingly, this varies by

educational attainment, with nonparticipating men with at least some college education

spending about 30 percent more time, or nearly an additional 45 minutes per day, on education

activities than less-educated men.

The largest difference in how men in and out of the labor force spend their time is in time spent

on leisure activities—socializing, relaxing and leisure, with nonparticipating men spending almost

twice as much time on these activities than those prime-age men overall, and more than twice

as much time watching television. Together, these patterns suggest that men are, on average,

not dropping out of the labor force to specialize in home production or to invest in skills to

improve their future labor market opportunities.

9

Education includes attending classes as well as research, homework, administrative tasks and extracurricular

activities except sports.

25

Poverty and the Well-being of Men Not Participating in the Workforce

Given the evidence above, it does not appear that the men who are no longer participating in the

workforce are choosing to do so because of better opportunities outside the labor force.

Moreover, detachment from the labor force dramatically increases the likelihood that a prime-

age man lives in poverty, in large part because those out of the labor force typically do not earn

wage income. Prime-age men generally experience low poverty rates relative to much of the

population: in 2014, 11 percent of all prime-age men lived in poverty compared to 15 percent of

the population as a whole, although the rate for prime-age men has nearly doubled since the

1970s (see Figure 18). In contrast, nearly 36 percent of prime-age men not in the labor force lived

below the poverty line in 2014, up from 28 percent in 1968.

As shown in Figure 19, the household incomes of nonparticipating prime-age men are notably

more likely to fall below 50 percent of the Federal poverty line—more than four times as likely

as prime-age men overall. More than 60 percent of nonparticipating prime-age men have

incomes that are less than 200 percent or less of the Federal poverty line.

26

Demand-Driven Explanations

In addition to the arguments outlined above, the most significant weakness of labor supply

explanations is that they are inconsistent with the trend in relative wages over the last several

decades. If less-educated men were simply choosing to work less, for example because of an

exogenous increase in the generosity of disability insurance, this should raise the relative wages

of the less-educated men who choose to continue participating in the workforce. Yet, in recent

decades the opposite has happened: less-educated Americans have actually suffered a reduction

in their wages relative to other groups. As shown in Figure 20, from 1975 until 2014, those with

a high school degree watched their relative wages fall from over 80 percent of the amount earned

by full-time, full-year workers with at least a college degree to less than 60 percent.

27

Demand for Less-Skilled Labor

A number of studies have identified declining labor market opportunities for low-skilled workers

and related stagnant real wage growth as the most likely explanation for the decline of prime-

age male labor force participation, at least for the period in the mid-to-late 1970s and 1980s

(Juhn, et al. 1991; Juhn and Potter 2006). More recently, economists have suggested that a

relative decline in labor demand for occupations that are middle-skilled or middle-paying may

have begun contributing to the decline in participation in the 1990s (Aaronson et al. 2014). As

demand for these middle-skilled workers has fallen, they may have displaced lower-skilled

workers from their lower-skilled jobs (Beaudry, Green, and Sand 2016), leading some lower-

skilled workers to leave the labor force. Aaronson et al. (2014) find that, since 1985, participation

rates for less-educated adults fell further in States with greater declines in middle-skilled

employment shares.

Economists do not have a singular answer for why demand for lower-skilled and middle-skilled

labor is falling. Possible causes include technological advances and globalization, including import

competition and offshoring (Acemoglu and Autor 2011; Autor and Doran 2013). Some

economists point to “skill-biased technological change:” advances that benefit workers with

certain skill sets more than others (Autor, Levy, and Murnane 2003; Autor, Katz, and Krueger

1998). These forces have, among other things, eliminated large numbers of American

manufacturing jobs over a number of decades as shown in Figure 21, leaving many people—

mostly men—unable to find new ones. In addition, men’s falling educational attainment levels

relative to women may have reduced their competitiveness for jobs and led them to opt out of

the labor force (Autor and Wasserman 2013).

In addition to reducing wages, abrupt demand shifts for less-skilled workers create

inconsistencies between workers’ expectations of the types of jobs they have traditionally had

access to (and that were closely associated with their identity) and the realities of the jobs

currently available to less-educated workers—for example, the decline in available jobs in

28

manufacturing. This mismatch between what workers seek and what the job market offers may

lead them to leave the labor force through a separate channel from real wage declines (Babcock

et al. 2012). Foote and Ryan (2015) support this, showing that these middle-skill workers who

become unemployed rarely reenter employment in either low- or high-skill jobs. Relatedly, the

authors find that the drop in the labor force participation rate for men over the past several

decades may be explained by a decline in job opportunities for middle-skill workers and their

reluctance to take jobs in other industries and skill classes.

Wages and Inequality

A demand shock will result in a combination of firms paying lower wages to their workers, some

of whom are unwilling to work at these lower wages and drop out of the labor force. This

relationship broadly matches the time series pattern of the national data. CEA analysis also finds

that the trends in the labor force participation rate for prime-age men are associated with other

economic trends such as wages and inequality, although this analysis should not necessarily be

interpreted as causal—in fact, interpreting this as a demand shift is consistent with both

inequality and participation being affected by a common shock, like technological change or

globalization.

These relationships are detailed in Table 2. The left-hand columns of the table report the

association between a $1,000 increase in annual wages at different percentiles of the wage

distribution in a State and its prime-age male labor force participation rate, controlling for time-

invariant State differences as well as national time trends. The correlation is notably strongest at

the bottom of the wage distribution: at the 10

th

percentile, a $1,000 increase in annual wages, or

a roughly $0.50 increase in hourly wages for a full-time, full-year worker, is associated with a 0.17

percentage-point increase in the State labor force participation rate for prime-age men.

Higher up in the wage distribution, the correlation between wages and participation becomes

weaker, with a $1,000 increase in annual wages at the median corresponding to just 0.05

percentage point higher participation rates.

10

10

This analysis shows a similar pattern of results using natural logs on both sides of the regression. We report

coefficients from levels regressions for expository ease.

29

Table 2: Impact of Prime-Age Male Wages and Inequality on Prime-Age Male Labor Force

Participation at the State Level: 1977-2015

Wage Measure (Thousands of $)

Coefficient

(Standard Error)

Inequality

Measure

Coefficient

(Standard Error)

10

th

percentile

0.169**

90/10 ratio

-0.292**

(0.043)

(0.082)

25

th

percentile

0.104*

50/10 ratio

-0.723**

(0.045)

(0.156)

Median

0.046

90/50 ratio

-0.447

(0.031)

(0.704)

75

th

percentile

0.019

75/25 ratio

-0.884

(0.020)

(0.620)

90

th

percentile

0.006

(0.012)

Robust standard errors in parentheses, clustered by State

** p<0.01, * p<0.05

Each row is a separate specification. All specifications include fixed effects for State and year and are weighted by population. The dependent variable is the labor

force participation rate of prime-age men. These measures do not include wages that are less than or equal to zero.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey (Annual Social and Economic Supplement); CEA calculations.

When the returns to work for those at the bottom of the wage distribution are particularly low,

more prime-age men choose not to participate in the labor force. As noted above, these

correlations do not necessarily support a causal relationship. These patterns may reflect how

local business cycles unwind or how shifts in labor demand are realized in terms of both

employment and wages. Nonetheless they show that labor force participation is more strongly

correlated with wage strength at the bottom of the distribution.

In addition, average State-level participation decisions are negatively correlated with measures

of wage inequality, suggesting that where wages at the bottom of the distribution are low relative

to wages higher up in the distribution, fewer men participate. In the right-hand columns of Table

2, we examine how the distance between the wage percentiles reported in the left-hand columns

impacts prime-age male labor force participation decisions. These regressions also suggest that

inequality between the very bottom and very top of the distribution matters as well.

Inequality higher up in the wage distribution matters somewhat less than inequality at the

bottom of the distribution. The robustness of this pattern makes clear that when wages at the

bottom end of the earnings distribution lag further behind middle and high percentiles, prime-

age men are more likely to opt out of the labor force.

The share of State jobs in some industries is also correlated with labor force participation rates

among prime-age men. Specifically, when the share of State employment attributable to

construction, mining and to a lesser extent manufacturing are higher, more prime-age men

participate in the labor force. Again, these correlations do not imply causality, but these

30

statistically meaningful correlations show that employment concentration in some industries is

more associated with prime-age male participation than others. Construction in particular may

play an important role; a recent paper shows that the housing boom during the early- to mid-

2000s and its resulting construction jobs may have masked the employment effect of

manufacturing declines for less-educated workers (Charles, Hurst and Notowidigdo 2013).

Institutional Explanations

All advanced economies have faced similar changes in technology and globalization, but the

United States has seen a larger decline in prime-age male labor force participation rates than just

about any other advanced economy along with a larger increase in inequality. This suggests that

these changes cannot be explained by supply and demand factors alone but also depend on

institutional differences between different countries and how they have processed their common

demand shock. Moreover, it appears the pattern of labor force participation in the United States

has become increasingly cyclical, further suggesting that institutional changes in the United

States matter. Although the precise institutions and policies are not yet well understood, cross-

country and time series comparisons provide some suggestive clues.

U.S. Labor Market Institutions in International Context

The United States has the types of flexible labor markets that traditional economic prescriptions

recommend for a well-functioning labor market. The United States has the lowest level of labor

market regulation, the fewest employment protections, the third-lowest minimum cost of labor,

and among the lowest rates of collective bargaining coverage among OECD countries, according

to the OECD’s Going For Growth Indicators, as shown in Table 3. In the United States,

governments and institutions (such as labor unions) place relatively few barriers in the way of

employers who want to change who they employ and what they pay.

Table 3: Labor Market Flexibility

OECD Measures of Labor Market Flexibility

U.S. Percentile Rank

(100 = Most Flexible)

Barriers to Entrepreneurship

62

Labor Taxation

71

Coverage of Collective Bargaining Agreements

90

Minimum Cost of Labor

92

Scope of State Intervention

94

Employment Protection for Regular Employment

100

Overall Labor Market Regulation

100

Source: OECD 2015; CEA calculations.

31

While the factors above provide reasons why we might expect labor force participation in the

United States to be higher, other features of the U.S. labor market push in the opposite direction.

U.S. labor markets are much less “supportive” than in other OECD countries (see Table 4). The

United States spends 0.1 percent of GDP on so-called “active labor market policies” such as job-

search assistance and job training, much less than the OECD average of 0.6 percent of GDP, and

less than every other OECD country except Chile and Mexico. These policies provide better

incentives for individuals in other countries to stay attached to the labor force by providing more

support during unemployment (when individuals must also search for work) and making re-

employment more likely through skill-building. The United States also provides fewer subsidies

for child care, has a higher tax wedge on secondary earners, and is the only advanced economy

not to provide paid leave.

Table 4: Labor Market Support

OECD Measures of Institutional Labor Market

Support

U.S. Percentile Rank

(100 = Most Flexible)

Nationwide Paid Leave Policy

0

Expenditure on Active Labor Market Policies

3

Net Childcare Costs, Lone Parent

6

Implicit Tax on Returning to Work, Lone Parent

9

Unemployment Benefits (1 Year)

11

Unemployment Benefits (5 Years)

11

Number of Weeks Lost Due to Sick Leave

11

Net Childcare Costs, Couples

13

Implicit Tax on Returning to Work, Second Earner

13

Tax Wedge: Single Earner vs. Second-Earner Couples

25

Public Expenditure for Childcare

29

Source: OECD 2015; CEA calculations.

One traditional defense of American-style labor market arrangements is that though they may

result in more inequality, the labor market will function better as a result. But the U.S.

participation rate is among the lowest in the OECD and even the employment-population ratio is

towards the low end, especially after adjusting for cyclical downturns in other countries.

This simple comparison does not, by itself, establish the cause of the difference between the

long-standing structural performance of the U.S. labor market for prime-age workers and the

performance in other countries. But it does suggest that a successful labor market requires, at

the very least, more than just flexibility but also policies or institutions that help connect workers

with jobs or facilitate their taking jobs through subsidized childcare or flexible workplaces.

In some cases the lack of institutional arrangements to help worker’s bargaining power may even

impede labor force participation. One theory of labor markets is that because matching to jobs

32

is costly, each job match generates a surplus that is divided between employers and employees.

To the degree that the minimum wage or labor unions raise the wage, that will change the

division of the surplus—which would potentially result in an increased supply of labor (Card and

Krueger 1994). In addition, in some OECD economies institutional arrangements may help

prevent wages from falling all the way to the market-clearing level, potentially leading to more

unemployment in some cases but also making attachment to the labor force more attractive. In

the United States, on the other hand, flexible policies may cause the market-clearing wage for

some prime-age men—particularly the low-skilled, who participate in the labor force at the

lowest rates—to be too low to incentivize participation. For these workers in particular, policies

ensuring a sufficient minimum wage or job training that helps to find higher-paying job may be

especially effective in increasing participation rates.

Many advanced economies have other labor market concerns, especially with younger workers,

older workers, and women’s underrepresentation in management positions. But the difference

in prime-age male labor force participation between the United States and OECD countries with

less flexible labor markets suggests that the American labor market has room to improve when

it comes to creating conditions for meaningful employment. Although the United States differs

from other OECD countries across a variety of measures, such as demographics and industrial

composition, the contrast in participation rates also reveals a flaw in the standard economic view

about the tradeoffs between flexibility and supportive labor policies.

Incarceration and Criminal Records

One important change in the United States over time and a major difference from other OECD

countries is the rise of mass incarceration and the associated rise in the fraction of the population

that was formerly incarcerated. Those who emerge from the criminal justice system suffer

stigma, hiring restrictions, and potentially reduced ability to work as a result, reducing the

demand for their labor. Incarceration policies affect participation rates directly by removing

workers from the labor force for a period of time but also long-term as the stigma of incarceration

can reduce demand for the labor services of the formerly incarcerated even years after their

reentry into society. The rise of mass incarceration has likely contributed to the larger decline in

prime-age male labor force participation rates in the United States relative to other countries.

33

The number of men behind bars in the United States has increased substantially, growing from

564 per 100,000 in the population in 1990 to 890 per 100,000 in 2014, as shown in Figure 22. The

United States also has the highest share of its population in prison, other than the Seychelles,

and is nearly five times the OECD average, as shown in Figure 23. Moreover, the United States

has seen a more rapid increase in incarceration rates than other countries.

The direct effect of increased incarceration is to actually increase the reported participation rate

because the official statistics cover only the non-institutionalized population and omit prisoners,

people in long-term care, and active duty members of the Armed Services. In 2014, there were

almost 1.1 million prime-age men in Federal or State prison, in addition to prime-age men in local

prisons. Making the extreme assumption that if these men were not in prison they would have

all been out of the labor force, then adding them to the prime-age male population (the

denominator of the labor force participation rate) would result in a participation rate for prime-

34

age men of 86.7 percent, which is 1.5 percentage point lower than the reported 88.2 percent

rate (Bureau of Justice Statistics; Bureau of Labor Statistics; CEA calculations). Of course many of

these 1.1 million men would actually participate in the labor force if they were not in prison.

Because incarcerated men tend to have notably lower educational-levels than the overall

population, limited earnings before their incarceration, have experienced extended time out of

the labor force, and may face stigma and low labor demand upon their reentry, it is likely that

these men would participate at lower rates than prime-age men as a whole if they were not

incarcerated. Therefore, the actual effect of incarceration on the participation rate would likely

be somewhere between zero and an upper-bound of -1.5 percentage point.

The indirect effect of increased incarceration rates is to reduce the participation rate, as these

men tend to face substantially lower demand for their labor after they are released from prison

and join the ranks of the formerly incarcerated. In many States, the formerly incarcerated are

legally barred from a significant number of jobs by occupational licensing rules or other

restrictions on the hiring of those who have been incarcerated. According to the American Bar

Association, there are over 1,000 mandatory license exclusions for individuals with records of

misdemeanors and nearly 3,000 exclusions for felony records (American Bar Association 2016).

In addition, evidence shows that, even in the absence of legal restrictions, employers are less

likely to hire someone with a criminal record (Holzer 2007).

The Current Population Survey and other official data do not track the share of the population

that were formerly incarcerated but given the large increase in incarceration rates, this has likely

risen substantially as well. Recent estimates suggest that between 6.4 and 7.2 percent of the

prime-age male population in 2008 were ex-offenders (Schmitt and Warner 2010; CEA