1

The State of Black

Students at

Community Colleges

September 21, 2022

Dr. Alex Camardelle, Brian Kennedy II, and Justin Nalley

2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Executive Summary

Introduction

What are Community Colleges?

Background

Black Student Enrollment in Community College

Pandemic Period Enrollment Trends

Select Black Student Characteristics

Outcomes

Graduation Rates

Certicates vs. Degrees

Rates of Transfer

Earnings

Black Student Debt at Community Colleges

Conclusion

About the Authors

Acknowledgments

References

3

4

5

6

9

15

19

21

22

3

EXECUTIVE SUMMAR Y

This research brief examines administrative data to describe the characteristics and select educational and

economic outcomes for Black students who attended community colleges. Given the role of community

colleges during economic downturns and the disproportionate enrollment of Black students, it is essential

to understand how community colleges can be tools for economic recovery in the context of COVID-19

when Black adults continue

to face high unemployment

rates.

1

From our analysis of

the limited data on Black

community college students,

we find that while Black

students are disproportionately

represented at community

colleges, the system does not

produce equitable outcomes.

Future research and policy concerning community colleges must address the barriers that prevent these

institutions from serving as an equitable education solution for Black communities. Other key findings in

this brief include the following:

•

Despite the historic lure to community colleges during previous recessions, Black student enrollment

has steadily declined over time and has worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic. From Fall 2019 to

Fall 2021, enrollment fell 18 percent for all Black students and 23.5 percent and 15 percent for Black

men and Black women, respectively.

•

Black community college students experience the lowest graduation rates when compared to their peers

of other races and ethnicities. The gap between Black and white graduation rates more than doubled from

four percentage points in 2007 to 11 percentage points in 2020, the latest year data is available.

•

Community colleges award Black students certificates at higher rates than other groups. In the 2019-

2020 year, fewer than half (47 percent) of the awards given to Black community college completers

were associate degrees, while the opposite is true for all other racial groups.

•

The typical Black community college graduate earns $20,000 less per year than their classmates.

White households with workers who hold a high school diploma earn $2,000 more than Black

community college graduates.

•

Over two-thirds (67 percent) of Black students borrowed money to pay for community college

compared to 51, 36, and 30 percent of white, Hispanic, and Asian students, respectively. Black

community college graduates owe 123 percent of the original amount they borrowed 12 years after

beginning their community college journey.

Executive Summary

From our analysis of the limited data on Black

community college students, we find that while

Black students are disproportionately represented

at community colleges, the system does not produce

equitable outcomes.

4

INTRODUCTION

Earning a credential beyond a high school diploma is imperative for access to good jobs. An estimated

two-thirds of all jobs in the economy require some education and training beyond high school.

2

Increasingly, Black students are completing their bachelor’s degrees as attainment has risen from 20 to

28 percent since 2011.

3

Some students also choose to delay or even forego a bachelor’s degree after high

school and instead pursue vocational or technical training at community colleges to gain credentials for

occupations that only require certifications or an associate degree.

WHAT ARE COMMUNITY COLLEGES?

Community colleges are an essential access point to higher education for Black students. While

community colleges pursue many competing missions, two of their most salient priorities include

preparing students for transfer to four-year degree programs and graduating them from terminal

programs that lead to

occupations that do not

require a bachelor’s degree.

Today, more than one-third

(36 percent) of all Black

undergraduate students

can be found in the nation’s

community colleges.

4

Historically, community

colleges helped counter

economic downturns because

they are accessible and

proximal to those most likely to

become unemployed.

5

During

the Great Recession, Black students enrolled in community colleges at higher rates than other racial

groups.

6

These higher community college enrollment rates were associated with higher unemployment

rates and fewer available jobs for Black workers.

7

But unlike the Great Recession period, Black student

enrollment has declined during the COVID-19 economic downturn, especially at community colleges.

Introduction

Community colleges, sometimes referred to

interchangeably as junior colleges, technical colleges,

and two-year colleges, are postsecondary institutions.

In two years or less, community colleges offer a variety

of credentials ranging from the GED and professional

certifications to associate degrees. Community

colleges also offer general education course credit

that students can use to transfer to major programs at

four-year colleges and universities.

5

Background

BACKGROUND

Community colleges were initially recognized as junior colleges in the United States. The original

purpose of the junior college, which researchers trace as far back as the mid-19th century, was

to prepare students who were not yet ready for university education.

8

A two-year education at

the junior college was understood as an extension of the high school, offering a combination of

college preparatory coursework, remedial courses, and technical/vocational education.

9

In the

1940s, junior colleges were rebranded as community colleges to recognize their access to local

communities and an expanded mission to prepare students for occupations that did not

necessarily require education beyond a two-year degree.

10

Despite being understood as more accessible and affordable than four-year colleges and

universities, community colleges have not been immune to the systemic racism that has erected

barriers for Black students in education. In the early and middle part of the 20th century, most

community colleges excluded Black students through de jure and de facto segregation, which

resulted in unequal access to well-funded and high-quality postsecondary education.

11

Those

community colleges that served higher shares of Black students typically suffered from state

underinvestment, a trend that continues today.

12

The community college demonstrates how equal and open access does not always facilitate

more equitable access to higher education and better careers. Today, community colleges, which

disproportionately enroll higher numbers of Black students, suffer from a $78 billion funding

shortfall compared to four-year institutions which enroll disproportionately higher shares of white

students.

13

Researchers have also criticized community colleges for their history of tracking

Black students away from four-year colleges and universities.

14

This troubling trend has been

recognized in the uneven rates of transfer from two-year to four-year programs among Black

students compared to white students.

15

Community colleges still enroll Black students at higher rates than white students despite their

complex history of segregation and tracking. Understanding how Black students fare is critical

given the disproportionate representation of Black students in two-year schools, the many

competing goals of community colleges, and new economic challenges emerging from the

COVID-19 pandemic. The following section explores the characteristics of Black students who

attend community colleges.

vs.

COMMUNITY COLLEGES

funding shortfall

FOUR-YEAR COLLEGES

$

78B

Disproportionately enroll higher

numbers of white students

Disproportionately enroll higher

numbers of Black students

Source: Adapted from “The $78 billion Community College Funding Shortfall,” Center for American Progress, 2020.

6

BLACK STUDENT ENROLLMENT IN

COMMUNITY COLLEGE

Typically in moments of economic uncertainty, individuals turn to colleges and universities to

obtain additional training to gain more credentials and become more employable in the labor

market.

16

Between 2006 and 2011, spanning before and after the Great Recession,

postsecondary school enrollment increased by 2.8 million students, with two-year colleges

accounting for half of that increase.

17

However, in the years following the Great Recession,

community college enrollment declined between 2010 and 2020. Black student enrollment

declined by a staggering 44 percent, from 1.2 million in 2010 to 670,000 in 2020.

18

Further, the

share of Black students in community college fell from 16 to 14 percent during the same period.

Black Student Enrollment in Community College

Asian American Native American or HawaiianLatinoWhiteAfrican American

0.9

%

6.8

%

26.8

%

47.7

%

13.8

%

0.7

%

7.7

%

23.3

%

50.0

%

13.1

%

1.0

%

6.3

%

24.4

%

50.4

%

14.7

%

0.8

%

6.8

%

17.4

%

57.6

%

14.1

%

1.1

%

6.1

%

18.2

%

57.0

%

15.8

%

1.0

%

6.3

%

13.5

%

62.6

%

15.0

%

2010 2015 2020

Figure 1: The share of Black students enrolled in community college fell over the last decade

Postsecondary and community college enrollment by race, 2010-2020

Source: Joint Center analysis of data provided by the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, Spring 2010 through Spring 2021.

Public and for-prot institutions are included.

Postsecondary

Enrollment

Postsecondary

Enrollment

Postsecondary

Enrollment

Community College

Enrollment

Community College

Enrollment

Community College

Enrollment

7

PANDEMIC PERIOD ENROLLMENT TRENDS

Although recessionary events have caused enrollment spikes at community colleges in the past,

19

the

current pandemic recession shows a different trend. The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the

trend of rapidly declining Black student enrollment. The National Student Clearinghouse Research

Center’s Stay Informed series tracked college enrollment trends in near real-time during the COVID-19

era. Preliminary data for fall 2021 shows a decline of 15 percent in community college enrollment from

pre-pandemic levels in 2019 compared to just four percent at public four-year institutions.

20

In the same

period, Black student enrollment at community colleges decreased by 18 percent, with enrollment falling

for Black men by 24 percent and Black women by 15 percent.

21

A mix of factors may be contributing to these declines. For instance, young Black adults’ concerns about the

cost of attendance at community college affect their enrollment despite community colleges being relatively

more affordable than four-year schools.

22

Moreover, these drops signal that Black adults — particularly

Black men — may face barriers such as food, housing, and employment insecurity that prevent them from

pursuing educational opportunities that could aid in economic recovery.

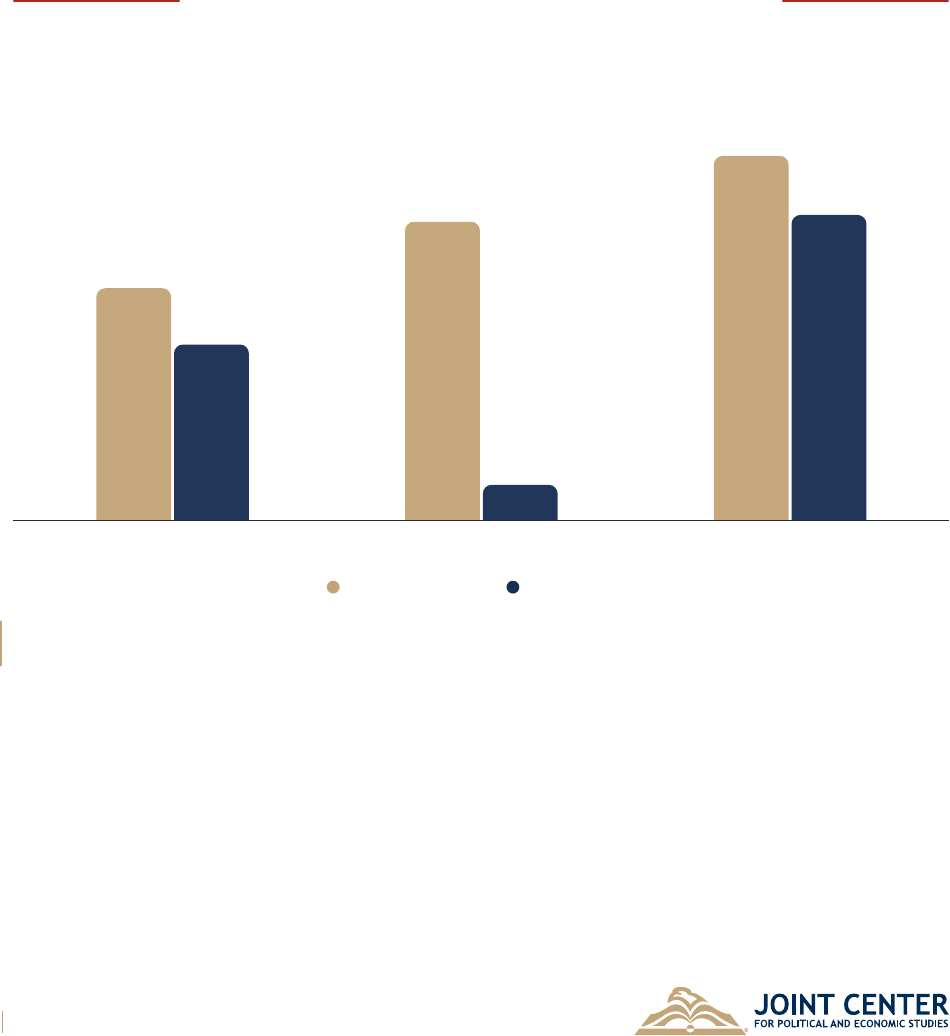

Black Student Enrollment in Community College

Figure 2: Black men face the greatest declines in community college enrollment

Community college enrollment changes by race and gender, 2019-2021

African American White Latina/o Asian

-24

%

-15

%

-21

%

-17

%

-20

%

-13

%

-20

%

-16

%

WomenMen

Source: Joint Center analysis of data provided by the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, Fall 2021.

8

SELECT BLACK STUDENT CHARACTERISTICS

Black community college students experience financial hardship at a greater rate than other racial

groups. According to the 2016 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study, the median income for

Black community college student households was $24,044 compared to $39,385 for white students.

23

Of community college students, 36 percent of Black students are in poverty, followed by 28 percent of

Latina/o students, and 18 percent of white students.

24

Community colleges provide greater course scheduling flexibility and lower tuition costs, leading to a large

share of parents in college attending two-year institutions.

25;6

Student parents make up 20 percent of the

overall college population, but are overrepresented at the community college level, where 42 percent of all

student parents are enrolled.

27

Black students are more likely to be parents when compared to other racial

groups. About 40 percent of Black women and 21 percent of Black men in college are parents.

28

Thirty-five

percent of Black students in community colleges are parents.

29

Community college students are often employed while in school. Among Black community college students,

78 percent report having a job at some point during the school year.

30

The employment levels of Black

students are comparable to other racial groups, as 79 percent of community college students hold a job at

some point during the school year.

31

Black Student Enrollment in Community College

$

24,044

$

39,385

Median household

income for Black community

college students

Median household

income for white community

college students

OUTCOMES

Although many see community colleges as an accessible entry point into higher education and a tool

for achieving educational equity, Black students face drastically different outcomes than their non-

Black classmates. From completion rates to earning potential, community colleges largely fail to deliver

equitable results for Black community college students.

GRADUATION RATES

Although the number of Black credential and degree recipients has increased over the past two decades,

Black students in two-year institutions typically experience the lowest graduation rates across race

and ethnicity. In 2019-2020, the last year for which racially disaggregated graduation rates are available,

only 28 percent of Black community college students graduated within three years (150 percent

normal completion) compared to 44, 39, and 34 percent of Asian, white, and Latina/o students,

respectively (Figure 3).

32

44

%

37

%

36

%

28

%

34

%

39

%

31

%

American Indian or

Alaska native

Asian Native Hawaiian

or other Pacific

Islander

Black or African

American

Hispanic or

Latina/o

White Two or more races

Figure 3: Black students have the lowest graduation rates at community colleges

Graduation rates within 150% of normal completion time, by race, 2019-2020

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), Graduation Rates

component 2020 provisional data.

Outcomes

9

10

CERTIFICATES VS. DEGREES

Although community colleges offer a variety of pathways to a career, they are most recognized for awarding

associate degrees and certificates. Associate degrees can lead to increased earnings, but these returns

are dependent on the field of study and occupation.

33;4

While all postsecondary credentials may provide

valuable returns on investment for students, certificates fall near the bottom of the list of credentials that

boost earning power.

35

Joint Center analysis finds a troubling indicator with this evidence in mind: Community colleges award

Black students certificates at higher rates than other groups. In the 2019-2020 school year, fewer than

half of the awards given to Black community college completers were associate degrees, while the

opposite is true for all other racial groups.

36

More research is needed to understand the different benefits

of certifications and associate degrees for Black students.

Outcomes

Figure 4: Black students are more likely to be awarded certificates than degrees

Degrees and certificates by award type and race, 2019-2020

47

%

53

%

59

%

46

%

53

%

47

%

60

%

40

%

African American White Hispanic Asian

Share of certificatesShare of associate degrees

Source: Joint Center analysis of data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, 2019-2020.

11

RATES OF TRANSFER

In addition to offering associate degrees and certifications, community colleges continue to provide

transfer education to help students transition to four-year degree programs.

37

These four-year degree

programs may lead to higher paying jobs, but research has long shown disparities between Black transfer

rates and the transfer rates of other groups to four-year degree programs.

38

Prior to the COVID-19

pandemic, Black community college students were the least likely to transfer to four-year colleges and

universities compared to their peers.

39

Figure 5: Prior to COVID-19, Black community college students were

the least likely to transfer to four-year degree programs

Transfer rates from public two-year colleges to public four-year college by race, 2011-2017

28

%

48

%

48

%

37

%

African American White Asian Hispanic

Source: Shapiro, Doug, Afet Dundar, Faye Huie, Phoebe K. Wakhungu, Ayesha Bhimdiwala, Angel Nathan, and Youngsik Hwang. “Transfer and mobility:

A national viw of student movement in postsecondary institutions, Fall 2011 cohort” (2018).

More recent data shows that transfer rate gaps may be worsening for Black students during the pandemic.

While the share of all students transferring from community college to public four-year colleges fell by

11.6 percent, Black student transfers making that same transition fell more sharply by 14.2 percent.

40

EARNINGS

One of the primary reasons students and workers seek higher education is to increase their earning

potential, but Black workers do not equitably benefit. In 2020, Black households with workers who

graduated from a community college earned nearly $16,000 per year more than Black households

without associate degrees.

41

Yet, deep racial disparities in household income persist, regardless of

educational attainment. That same year, white families with workers who held a high school diploma

earned $2,000 more than Black community college graduates.

42

Outcomes

12

Outcomes

After obtaining an associate degree, Black workers face significantly lower earnings than their

counterparts. In 2020, the median income for U.S. households with associate degree holders was

$68,769. A typical white household with an associate degree holder earned $73,948 per year, while a

typical Black household with an associate degree holder earned just $48,724 (Figure 6).

43

Further, 29.3

percent of Black households with associate degrees earned less than $30,000 per year (the equivalent

of two full-time workers earning minimum wage), compared to 18.7 percent of all households with

associate degrees (Figure 7).

44

Figure 6: Black workers face significantly lower earnings than their counterparts

after obtaining an associate degree

Median household income by race for associate degree holders, 2021

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Suvey, 2021 Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC).

African American

Hispanic

All

White

Asian

$48,724

$68,048

$68,769

$73,948

$82,044

Figure 7: Black community college graduates are more likely than their

peers to to earn poverty wages

Household income of associate degree holders by race, 2021

31.0

%

26.1

%

18.7

%

24.3

%

16.8

%

24.3

%

29.3

%

29.4

%

33.9

%

26.3

%

17.0

%

22.8

%

37.6

%

25.4

%

12.7

%

23.8

%

29.1

%

27.7

%

17.5

%

26.8

%

More than $100,000$60,000-$99,999$30,000-$59,999Less than $30,000

All Black Asian alone HispanicWhite

Source: Joint Center’s analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Suvey,

2021 Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC).

Note: A “poverty wage” is a wage that would leave a full-time, year-round worker below the federal poverty guideline.

In 2022, the poverty threshold for a family of four is $27,750.

13

Outcomes

BLACK STUDENT DEBT AT COMMUNITY COLLEGES

The contrast between the earning potential of Black students pursuing degrees and certifications

at community colleges with the amount of debt required to attend those institutions is concerning.

Community colleges are a more affordable alternative to four-year institutions, especially for students

from low-income backgrounds.

45

About two-thirds of community college students graduate with zero

debt.

46

In 2021, the average cost of attending an in-district community college was $3,730 per year.

47

Over the past 20 years, community college tuition has increased by only 46 percent, compared to a 76

percent increase in tuition costs at public four-year institutions during that same period.

48

Despite the relative affordability of community colleges, deep racial disparities in student loan debt

persist. Black students are more likely to borrow for school, owe more in student loans, and are twice

as likely to default on student loans than white borrowers.

49

According to the U.S. Department of

Education, Black associate degree recipients are more likely than other racial and ethnic groups to

take out loans to attend two-year institutions. In 2016, over two-thirds (67 percent) of Black students

borrowed money to pay for community college compared to 51, 36, and 30 percent of white, Hispanic,

and Asian students, respectively (Figure 8).

50

On average, Black students borrowed $22,303, more than

any other racial/ethnic group.

Percent who borrowed

The average amount

borrowed per borrower

Percent of borrowers who

are independent borrowers

All racial and ethnic groups 48% $18,501 64%

American Indian or Alaska Native 67% $18,225 76%

Asian 30% $17,459 60%

Black or African American 67% $22,303 77%

Hispanic or Latina/o 36% $15,778 56%

Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander 47%

*

46%

White 51% $17,794 64%

More than one race 51% $21,795 65%

Figure 8: Total borrowing: Associate degree recipients, by race and ethnicity: 2015–16

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Postsecondary Student Aid Study, 2016.

*Estimate suppressed. Reporting standards not met.

In addition to taking on larger amounts of student debt, Black and Indigenous students are more likely

to be the sole carriers of their student loan debt, meaning they were less likely than any other group to

receive support with their loans from parents or other family members. In 2016, 77 percent of Black

borrowers were the independent holders of their community college loans (Figure 8). Those same

students, on average, took out $14,986 in loans compared to $9,063, $5,719, and $5,170 for white,

Hispanic, and Asian students, respectively.

51

14

Outcomes

Black students in public institutions borrow at starkly different rates and levels than Black students in

for-profit institutions. Just over 57 percent of Black students who receive associate degrees at public

two-year institutions took out loans, averaging $10,652 borrowed per student.

52

Yet 92.9 percent of Black

students who receive associate degrees from for-profit two-year institutions took out student loans,

averaging $28,075 borrowed per student.

53

Black students also face racial disparities in their ability to repay their loans. The typical Black associate

degree recipient owes 123 percent of the original amount they borrowed 12 years after beginning their

degree, compared to 69 and 91 percent for white and Hispanic students, respectively (Figure 9).

After

the same period, the typical Black certificate recipient still owes 103 percent of the original amount

borrowed compared to 68 percent for all recipients.

54

Figure 9: After 12 years, the typical Black borrower owes 123% of

their original loan amout

Ratio of the amount still owed to amount borrowed 12 years after first beginning postsecondary

education by award level and race and ethnicity, 2021

59

%

103

%

69

%

123

%

103

%

91

%

12

%

*

White Hispanic or Latina/o Black or African American

CertificatesAssociate degree

Source: U.S. Department of Education, Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study, BPS:04/09, and 2015 Federal Student Aid Supplement

Note: Data for Asian recipients is not available for certicate recipients, so they were not included in this chart.

*Interpret with caution. Ratio of standard error to estimate is >50%.

15

CONCLUSION

The community college serves as a gateway to higher education for Black students in America. But access

to opportunity does not necessarily mean equity in enrollment, graduation, transfer, debt, and earnings

outcomes. Investments in

community colleges should

consider the inequitable

outcomes for Black students

described in this research

brief. Additionally, college

administrators, advocates,

and policymakers should do

the following:

Conclusion

The community college serves as a gateway to

higher education for Black students in America. But

access to opportunity does not necessarily mean

equity in enrollment, graduation, transfer, debt, and

earnings outcomes.

Improve access to basic needs

support for Black students

More than one in three Black community college students are in poverty, and widespread

inequality in community colleges deepened throughout the pandemic for Black students

facing basic needs insecurity. An alarming 70 percent of Black students experienced food

or housing insecurity or homelessness during the COVID-19 pandemic.

55

Basic needs insecurity is also closely associated with enrollment declines.

56

While

COVID-19 emergency funds authorized by Congress pushed community colleges to

introduce more support for meeting students’ basic needs, barriers to accessing those

supports remain. For example, 68 percent of Black male students at community colleges

experience basic needs insecurity. Still, only 31 percent of those with need accessed on-

campus resources meant to connect students with aid because too few knew they were

available or do not know how to apply.

57

Policymakers and college leaders should invest in expanding outreach and marketing efforts

to ensure students are aware of available resources. They should also invest in on-campus

infrastructure to improve basic needs security, such as food pantries and on-campus resource

hubs and caseworkers who help students easily apply for food, housing and child care

assistance, and more.

Policymakers and college leaders should invest in expanding outreach

and marketing efforts to ensure students are aware of available resources.

They should also invest in on-campus infrastructure to improve basic

needs security, such as food pantries and on-campus resource hubs and

caseworkers who help students easily apply for food, housing and child care

assistance, and more.

16

Conclusion

Improve access to

campus-based child care

Though many Black student parents enroll in community college, the lack of support

for parents makes it more challenging to complete a credential. Black (27 percent) and

Indigenous (28 percent) student parents are the most likely to have earned some college

credit but not completed a degree.

58

Even though most student parents work, single

parents have higher unmet financial needs than their peers and hold more student

debt.

59

Congress first authorized Child Care Access Means Parents in School (CCAMPIS)

funding in 1998 in an amendment to the Higher Education Act of 1965.

60

The program’s

goal is to support institutions in the design and implementation of campus-based child

care options for low-income student parents. Currently, fewer than half of community

colleges offer campus-based care.

61

CCAMPIS funding should be increased to expand campus-based childcare at all

community colleges. Additionally, college leaders should make student parents a priority

for basic needs programs and help students access child care subsidies and other family

support services.

CCAMPIS funding should be increased to expand campus-based child

care at all community colleges. Additionally, college leaders should make

student parents a priority for basic needs programs and help students

access child-care subsidies and other family-support services.

17

Strengthen transfer

pathways

Black students experience barriers to transfer success.

62

States and postsecondary

systems should enact policies that guarantee students will receive credit for any courses

taken for their general education core or the associate degree if they have completed one.

Public colleges and universities should also consider students who transfer with an

associate degree from a community college in the same state as having fulfilled the

destination school’s general education requirements. Historically Black Colleges and

Universities (HBCUs) should also strengthen their relationships with community colleges.

Evidence shows that Black students transferring from community colleges to HBCUs

are more likely to graduate with a bachelor’s degree compared to Black students who

transfer to predominantly white institutions.

63

Conclusion

Public colleges and universities should also consider students

who transfer with an associate degree from a community college

in the same state as having fulfilled the destination school’s

general education requirements. Historically Black Colleges and

Universities (HBCUs) should also strengthen their relationships

with community colleges.

18

Conclusion

Evaluate community college

outcomes by race and ethnicity

Make two-year community

college tuition-free

By analyzing data to reveal inequities among student groups, it may be possible to

uncover barriers to racial equity in higher education. To maximize community college

outcomes and advance racial equity, college leaders should regularly disaggregate data by

race and use multiple approaches to collect and analyze data by race.

64

Further, federal

law should require annual reporting and disclosure of community college outcome data

by race and allocate resources to those colleges that will boost the credential and career

outcomes of Black students.

One of the most common arguments against making two-year college tuition-free is

that these colleges are already primarily free after accounting for various types of

student aid. There are also concerns that making community college tuition-free would

affect enrollment at HBCUs, but HBCU leaders support the proposal when paired with

additional aid for HBCU students.

65

As our analysis shows, Black students still shoulder

the most debt at community colleges. The average in-state net price at a community

college in 2018 accounted for 20 percent or more of the median household income for

Black households in 14 states.

66

The Biden administration campaigned to make two years

of college tuition-free and should work with Congress to make good on that promise.

To maximize community college outcomes and advance racial equity,

college leaders should regularly disaggregate data by race and use

multiple approaches to collect and analyze data by race.

The Biden administration campaigned to make two years of

college tuition-free and should work with Congress to make good

on that promise.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr. Alex Camardelle is the director of the Workforce Policy Program

at the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, where he leads

a program that centers Black workers in policy debates concerning

the future of work, workforce development, and access to good jobs.

Prior to joining the Joint Center, Dr. Camardelle served as the senior

policy analyst for economic mobility at the Georgia Budget and Policy

Institute, where his research and advocacy supported policy reforms

shaping workforce development, worker justice, and access to core

safety net programs for individuals and families with low incomes. He

also worked at the Annie E. Casey Foundation, where he was responsible

for strengthening economic opportunity through research, grantmaking,

and partnerships. Dr. Camardelle holds a B.A. in political science from

the University of Alabama, and a master’s of public administration in

policy analysis and evaluation and a Ph.D. in educational policy studies,

both from Georgia State University. His scholarship focuses on race,

workforce development, and political economy.

Brian Kennedy II is a senior policy analyst for the Workforce Policy

Program at the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies. Prior to

joining the Joint Center, Kennedy served as a policy advisor in the U.S.

Department of the Treasury’s Office of Recovery Programs where he

supported the administration of American Rescue Plan funds to states

and local governments. Previously, Kennedy worked as a consultant with

Frontline Solutions, a Black-owned and led consulting firm supporting

non-profits and philanthropic organizations. Kennedy has also worked

as a senior policy analyst with the North Carolina Budget and Tax Center,

focusing on living wages and social safety net programs. Kennedy earned

bachelor’s degrees in history and political science from North Carolina

Central University and a master’s degree in public policy from the

Heller School at Brandeis University. Kennedy is also the co-host of “At

The Intersection,” a Durham-based podcast about policy, culture, and

identity.

19

About the Authors

About the Authors

20

Justin Nalley is a senior policy analyst for the Workforce Policy

Program at the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies.

Nalley brings his experience advocating for access to equitable

resources for Black communities to produce timely policy research

and data analysis, which centers Black workers in workforce

development, post-secondary access, and access to quality jobs.

Before joining the Joint Center, Nalley served as the senior public

policy analyst for the American Civil Liberties Union of Maryland.

In this role, Nalley researched, lobbied, and conducted state fiscal

analysis to shape policy for Black youth and families in public

education, juvenile justice reform, and voting rights. Nalley was also

instrumental in the formation and recognition of the first union at

the ACLU of Maryland and held the role of shop steward, leading

contract negotiations. He also worked at Baltimore City Public

Schools as an analyst, ensuring the large urban district received

accurate state revenue to support their students. Nalley is a member

of the National Forum for Black Public Administrators and the

Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management. Nalley

attended the University of Maryland Eastern Shore before earning

his Bachelor of Business Administration from Temple University and

Master of Public Administration from West Chester University.

21

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This report was made possible by the support of Lumina Foundation.

The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of

the authors. We thank Dr. Marshall Anthony for his expert input on this

paper including an external review of early versions of the issue brief.

Thanks also to our colleagues Jessica Fulton and Spencer Overton for their

review, as well as Chandra Hayslett, Victoria Johnson, and Kendall Easley

who edited the issue brief, alongside Rivan Stinson. This issue brief was

designed by Vlad Archin.

The Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, founded in 1970, is

a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization based in Washington, DC. The Joint

Center provides compelling and actionable policy solutions to eradicate

persistent and evolving barriers to the full freedom of Black people in

America. We are the trusted forum for leading experts and scholars

to participate in major public policy debates and promote ideas that

advance Black communities. We use evidence-based research, analysis,

convenings, and strategic communications to support Black communities

and a network of allies.

Opinions expressed in Joint Center publications are those of the

authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, officers, or

governors of the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies or of the

organizations that support the Joint Center and its research.

Media Contact

press@jointcenter.org | 202.789.3500 EXT 105

© Copyright 2022

All rights reserved.

Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies

633 Pennsylvania Ave., NW

Washington, DC 20004

info@jointcenter.org | jointcenter.org

@JointCenter

22

REFERENCES

1. Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics data, April 2022.

2. Anthony P Carnevale, Nicole Smith, and Jeff Strohl, “Recovery: Job Growth and Education Requirements through

2020,” (2013).

3. U.S. Census Bureau, 2003–2021 Annual Social and Economic Supplement to the Current Population Survey.

4. U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System

(IPEDS), Spring 2021, Fall Enrollment component.

5. Tolani Britton, “College or Bust… or Both: The Effects of the Great Recession on College Enrollment for Black and Latinx Young

Adults,” Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness (2022).

6. Lisa Barrow and Jonathan Davis, “The Upside of Down: Postsecondary Enrollment in the Great Recession,” Economic

Perspectives 36, no. 4 (2012).

7. Britton, “College or Bust… or Both: The Effects of the Great Recession on College Enrollment for Black and Latinx Young

Adults.” Britton finds that unemployment increased the likelihood of college enrollment by 5.8 percentage points for Black

students and 6.6 percentage points for Latinx students after the Great Recession began. For both Black and Latinx young adults,

there was an increased likelihood of enrollment in two-year colleges in particular.

8. J. M. Beach, Gateway to Opportunity? : A History of the Community College in the United States, vol. 1st ed (Sterling, Va: Stylus

Publishing, 2010), Book. “The junior college idea can be traced to university campuses in 1835 at Monticello College, and in

1858 at Susquehanna University. Some scholars have pointed to Lewis Institute in Chicago, formed in 1896 as the first private

junior college. The first public institution to be named a junior college in the United States was Joliet Junior College in Illinois

in 1901.”; “The college preparatory high school in conjunction with the junior college would take over the first year or two of

undergraduate general studies. This institution [junior college] would prepare students to enter a university, which would be

strictly for specialized professional study and disciplinary research.”

9. Ibid. “Some junior colleges were built out of secondary schools, some were built out of universities, some were built out of

normal schools, and some were independent mostly private organizations, and of these, some were nonacademic technical

institutes. From the beginning, junior colleges combined an erratic mixture of curricula: college-level transfer, college

preparatory, remedial, and technical/vocational.”

10. Claire Krendl Gilbert and Donald E Heller, “Access, Equity, and Community Colleges: The Truman Commission and Federal

Higher Education Policy from 1947 to 2011,” The Journal of Higher Education 84, no. 3 (2013). The Truman Commission felt

that the term “junior” did not actually express the purpose these schools were serving — implying instead that students would

be moving on to four-year colleges. But one of the principal tasks in which the two-year colleges were engaging was terminal

vocational education. Furthermore, the commission wanted two-year colleges to be fully integrated into the life of their

communities, which made the term “community college” more appropriate than “junior college.”

11. J. M. Beach, Gateway to Opportunity? : A History of the Community College in the United States, 1st ed. (Sterling, Va: Stylus

Publishing, 2010), “Despite new policy initiatives and judicial reform, both de facto and de jure segregation remained in effect in

much of the country until the late 1960s and early 1970s. The 17 southern states that had de jure segregation until the 1950s did

not quickly end these legal statutes, and even when they did, de facto segregation was left in place. In a 1962 study of southern

and bordering states’ private and public community colleges, only 19 out of 245 schools (8 percent) specifically served Blacks, all

of them public and most of them in Florida. The remaining six institutions were in three other states. This left 13 of 17 southern

states (76.5 percent) without a Black-serving community college. And those few institutions that did serve African Americans

offered a distinctly unequal curriculum. As far as the sparse records indicate, only five formerly segregated junior colleges had

integrated by 1960.”

References

23

12. The Institute for College Access and Success, “Inequitable Funding, Inequitable Results: Racial Disparities at Public

Colleges,” (Washington, DC, 2019). “Public Associate Colleges (community colleges) receive the lowest revenue per student but

serve a much higher share of underrepresented students of color (38%)”; “… in one year, the United States spends $5 billion less

educating students of color at public colleges than their white peers.”

13. Victoria Yuen, “The $78 Billion Community College Funding Shortfall,” Center for American Progress (2020).

14. Peter Riley Bahr, “Cooling out in the Community College: What Is the Effect of Academic Advising on Students’ Chances of

Success?,” Research in Higher Education 49, no. 8 (2008).

15. Judith R Blau, “Two-Year College Transfer Rates of Black American Students,” Community College Journal of Research &

Practice 23, no. 5 (1999).

16. Schmidt, Erik, “Postsecondary Enrollment Before, During, and Since the Great Recession,” P20- 580, Current Population

Reports, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, 2018.

17. Ibid.

18. Joint Center analysis of U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Higher Education

General Information Survey (HEGIS), “Fall Enrollment in Colleges and Universities” surveys, 1976 and 1980; Integrated

Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), “Fall Enrollment Survey” and IPEDS Spring 2001 through Spring 2021, Fall

Enrollment component.

19. Barrow and Davis, “The Upside of Down: Postsecondary Enrollment in the Great Recession.”

20. The National Student Clearinghouse Research Center Stay Informed “Fall 2021 Enrollment.” (Washington, DC: Last

modified October 2021).

21. Ibid.

22. Motunrayo Olaniyan, Pei Hu, and Vanessa Coca, “College Enrollment During the Pandemic: Insights into Enrollment

Decisions among Black Florida College Applicants.” (Philadelphia, PA: Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice, 2022).

“[Black College] Applicants who expected to take out loans or use their savings to pay for college were 6 percentage points less

likely to enroll in the fall semester compared to those who did not need to take out loans or use their savings.”

23. Joint Center analysis of U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, National Postsecondary

Student Aid Study: 2016 Undergraduates. Data retrieved based on Adjusted Gross Income (AGI).

24. Ibid.

25. Huerta, Adrian H., Cecilia Rios-Aguilar, and Daisy Ramirez. “‘I Had to Figure It Out’: A Case Study of How Community

College Student Parents of Color Navigate College and Careers.” Community College Review 50, no. 2 (2022): 193-218.

26. Schumacher, Rachel. “Prepping Colleges for Parents: Strategies for Supporting Student Parent Success in Postsecondary

Education. Working Paper.” Institute for Women’s Policy Research (2013).

27. Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR) “Parents in College by the Numbers.” (2018).

28. Ibid.

29. Joint Center analysis of U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, National Postsecondary

Student Aid Study: 2016 Undergraduates.

30. Ibid.

31. Ibid.

32. U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System

(IPEDS), Graduation Rates component 2020 provisional data.

33. Thomas Bailey and Clive R Belfield, “Community College Occupational Degrees: Are They Worth It,” Preparing today’s

students for tomorrow’s jobs in metropolitan America (2012).

References

24

34. Clive Belfield and Thomas Bailey, “The Labor Market Returns to Sub-Baccalaureate College: A Review. A Capsee Working

Paper,” Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment (2017) “Based on large-scale studies from six states, the

average student who completes an associate degree at a community college will earn $5,400 more each working year than a

student who drops out of community college”

35. Clive Belfield and Thomas Bailey, “The Labor Market Returns to Sub-Baccalaureate College: A Review. A Capsee Working

Paper,” Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment (2017).

36. Joint Center analysis of data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, 2019-2020.

37. Kevin J. Dougherty and Barbara K. Townsend, “Community College Missions: A Theoretical and Historical Perspective,”

New Directions for Community Colleges 2006, no. 136 (2006).

38. Blau, “Two-Year College Transfer Rates of Black American Students.”; Robert Wassmer, Colleen Moore, and Nancy

Shulock, “Effect of Racial/Ethnic Composition on Transfer Rates in Community Colleges: Implications for Policy and Practice,”

Research in Higher Education 45, no. 6 (2004). “Community colleges with higher percentages of either Latino or African

American students have lower 6-year transfer rates.”

39. Doug Shapiro et al., “Transfer and Mobility: A National View of Student Movement in Postsecondary Institutions, Fall 2011

Cohort,” (2018). “For students who started at a two-year institution, results revealed that Asian (48.1 percent) and White (47.7

percent) students were much more likely to transfer to a four-year institution than Black (28.4 percent) and Hispanic (37.2 percent)

students. Overall, these findings reveal that Asian and White students are more likely to supplement their four-year coursework at a

two-year institution as well as continue their education at a four-year institution than Black and Hispanic students.”

40. Joint Center analysis of data provided by the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, May 2022. Since 2020,

upward transfer rates have fallen for all groups: -15.5 percent for white, -8.3 percent for Asian, -14.2 percent for Black, and -7.4%

percent for Hispanic.

41. U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 2021 Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC).

42. Ibid.

43. U.S Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 2021 Annual Social and Economic Supplement.

44. Joint Center analysis of U.S Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 2021 Annual Social and Economic Supplement.

45. Marshall Anthony Jr., Andrew H. Nichols, and J. Oliver Schak. “How Affordable Are Public Colleges in Your State for Low-

Income Students?” Washington: The Education Trust (2019).

46. Adam Looney, David Wessel, and Kadija Yilla, “Who Owes All That Student Debt? and Who’d Benefit If It Were Forgiven?,”

(Brookings, July 12, 2021).

47. Melanie Hanson, “Average Cost of Community College,” EducationData.org, December 27, 2021.

48. Ibid.

49. Ben Miller, “New federal data show a student loan crisis for African American borrowers.” Center for American Progress,

October 16 (2017)

50. U.S. Department of Education, National Postsecondary Student Aid Study, 2016.

51. Ibid.

52. U.S. Department of Education, National Postsecondary Student Aid Study, 2016.

53. Ibid.

54. U.S. Department of Education, Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study, BPS:04/09, and 2015 Federal

References

25

Student Aid Supplement.

55. Sara Goldrick-Rab, “Students Are Humans First: Advancing Basic Needs Security in the Wake of the Covid-19 Pandemic,”

COVID-19 Research (2021).

56. Ibid.

57. Sara Goldrick-Rab et al., “Supporting the Whole Community College Student: The Impact of Nudging for Basic Needs

Security,” Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice. (2021). “Black male students are the least likely to access campus

supports conditional on need. At two-year colleges, 68% of Black males experience basic needs insecurity, but only 31% of those

with need utilize campus supports, meaning the gap between need and use of supports is 37 percentage points. By comparison,

the gap for Latinx male students at two-year colleges is 31 percentage points, and for White males at two-year colleges, it is 26

percentage points.”

58. Catherine Hensly, Chaunté White, and Lindsey Reichlin Cruse, “Re-Engaging Student Parents to Achieve Attainment and

Equity Goals: A Case for Investment in More Accessible Postsecondary Pathways,” Institute for Women’s Policy Research (2021).

59. Melanie Kruvelis, Lindsey Reichlin Cruse, and Barbara Gault, “Single Mothers in College: Growing Enrollment, Financial

Challenges, and the Benefits of Attainment. Briefing Paper# C460,” Institute for Women’s Policy Research (2017).

60. Muriel Baskerville, Campus Childcare and the Influence of the Child Care Access Means Parents in School (Ccampis) Grant on

Student-Parent Success at Community Colleges (Morgan State University, 2013).

61. Barbara Gault et al., “Campus Child Care Declining Even as Growing Numbers of Parents Attend College,” Institute for

Women’s Policy Research (2014). “In 2015, 44 percent of community colleges offered on-campus childcare, compared to 53

percent in 2003.”

62. EA Meza, DD Bragg, and G Blume, “Including Racial Equity as an Outcome Measure in Transfer Research (Transfer

Partnerships Series, Data Note 2),” Seattle, WA: Community College Research Initiatives, University of Washington (2018).

63. Paul D. Umbach et al., “Transfer Student Success: Exploring Community College, University, and Individual Predictors,”

Community College Journal of Research and Practice 43, no. 9 (2019). “Transfer students with an associate degree who enroll

at the four-year institution are approximately 1.2 times as likely to graduate with a bachelor’s degree than those without an

associate degree … transfer students at HBCUs are 11 to 12 percentage points more likely than those at majority white institutions

to obtain a baccalaureate degree.”

64. Alex Camardelle et al., “Improving Training Evaluation Data to Brighten the Future of Black Workers,” (2022).; According

to email correspondence, “the Thurgood Marshall College Fund supports free community college as long as it isn’t decoupled

from additional student aid for HBCUs, which is what President Biden has suggested.”

65. Liann Herd, “Will Free Community College Hurt HBCU Enrollment?,” Diverse Issues in Higher Education, (2021).

66. Victoria Jackson and Matt Saenz, “States Can Choose Better Path for Higher Education Funding in Covid-19 Recession,”

Education Research, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (2021).

References