DATA AND COMPUTER COMMUNICATIONS, EIGHTH EDITION

A comprehensive survey that has become the standard in the field, covering

(1) data communications, including transmission, media, signal encoding, link

control, and multiplexing; (2) communication networks, including circuit- and

packet-switched, frame relay, ATM, and LANs; (3) the TCP/IP protocol suite,

including IPv6, TCP, MIME, and HTTP, as well as a detailed treatment of

network security. Received the 2007 Text and Academic Authors Association

(TAA) award for the best Computer Science and Engineering Textbook of the

year. ISBN 0-13-243310-9

COMPUTER ORGANIZATION AND ARCHITECTURE,

EIGHTH EDITION

A unified view of this broad field. Covers fundamentals such as CPU, control

unit, microprogramming, instruction set, I/O, and memory. Also covers

advanced topics such as RISC, superscalar, and parallel organization. Fourth

and fifth editions received the TAA award for the best Computer Science and

Engineering Textbook of the year. ISBN 978-0-13-607373-4

OPERATING SYSTEMS, SIXTH EDITION

A state-of-the art survey of operating system principles. Covers fundamental

technology as well as contemporary design issues, such as threads,

microkernels, SMPs, real-time systems, multiprocessor scheduling, embedded

OSs, distributed systems, clusters, security, and object-oriented design.

Received the 2009 Text and Academic Authors Association (TAA) award

for the best Computer Science and Engineering Textbook of the year.

ISBN 978-0-13-600632-9

BUSINESS DATA COMMUNICATIONS, SIXTH EDITION

A comprehensive presentation of data communications and

telecommunications from a business perspective. Covers voice, data, image,

and video communications and applications technology and includes a number

of case studies. ISBN 978-0-13-606741-2

COMPUTER NETWORKS WITH INTERNET PROTOCOLS

AND TECHNOLOGY

An up-to-date survey of developments in the area of Internet-based protocols

and algorithms. Using a top-down approach, this book covers applications,

transport layer, Internet QoS, Internet routing, data link layer and computer

networks, security, and network management. ISBN 0-13141098-9

THE WILLIAM STALLINGS BOOKS ON COMPUTER

NETWORK SECURITY ESSENTIALS, FOURTH EDITION

A tutorial and survey on network security technology. The book covers

important network security tools and applications, including S/MIME, IP

Security, Kerberos, SSL/TLS, SET, and X509v3. In addition, methods for

countering hackers and viruses are explored.

COMPUTER SECURITY (with Lawrie Brown)

A comprehensive treatment of computer security technology, including

algorithms, protocols, and applications. Covers cryptography, authentication,

access control, database security, intrusion detection and prevention, malicious

software, denial of service, firewalls, software security, physical security, human

factors, auditing, legal and ethical aspects, and trusted systems. Received the

2008 Text and Academic Authors Association (TAA) award for the best

Computer Science and Engineering Textbook of the year. ISBN 0-13-600424-5

WIRELESS COMMUNICATIONS AND NETWORKS, Second Edition

A comprehensive, state-of-the art survey. Covers fundamental wireless

communications topics, including antennas and propagation, signal encoding

techniques, spread spectrum, and error correction techniques. Examines

satellite, cellular, wireless local loop networks and wireless LANs, including

Bluetooth and 802.11. Covers Mobile IP and WAP. ISBN 0-13-191835-4

HIGH-SPEED NETWORKS AND INTERNETS, SECOND EDITION

A state-of-the art survey of high-speed networks. Topics covered include TCP

congestion control, ATM traffic management, Internet traffic management,

differentiated and integrated services, Internet routing protocols and multicast

routing protocols, resource reservation and RSVP, and lossless and lossy

compression. Examines important topic of self-similar data traffic.

ISBN 0-13-03221-0

AND DATA COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGY

CRYPTOGRAPHY AND

NETWORK SECURITY

PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICE

FIFTH EDITION

William Stallings

Prentice Hall

Boston Columbus Indianapolis New York San Francisco

Upper Saddle River Amsterdam Cape Town Dubai London Madrid

Milan Munich Paris Montreal Toronto Delhi Mexico City Sao Paulo

Sydney Hong Kong Seoul Singapore Taipei Tokyo

Vice President and Editorial Director, ECS:

Marcia Horton

Executive Editor: Tracy Dunkelberger

Associate Editor: Melinda Haggerty

Editorial Assistant: Allison Michael

Senior Managing Editor: Scott Disanno

Production Editor: Rose Kernan

Senior Operations Supervisor: Alan Fischer

Operations Specialist: Lisa McDowell

Cover Design: Black Horse Designs

Art Director: Kristine Carney

Director, Image Resource Center: Melinda

Patelli

Manager, Rights and Permissions: Zina Arabia

Senior Marketing Manager: Erin Davis

Manager,Visual Research: Beth Brenzel

Manager, Cover Visual Research & Permissions:

Karen Sanatar

Composition: Integra

Printer/Binder: Edwards Brothers

Credits and acknowledgments borrowed from other sources and reproduced, with permission, in this textbook

appear on appropriate page within text.

If you purchased this book within the United States or Canada you should be aware that it has been

wrongfully imported without the approval of the Publisher or the Author.

Copyright © 2011, 2006 Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Prentice Hall. All rights reserved.

Manufactured in the United States of America.This publication is protected by Copyright, and permission

should be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction, storage in a retrieval system, or

transmission in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or likewise.To

obtain permission(s) to use material from this work, please submit a written request to Pearson Education, Inc.,

Permissions Department, 1 Lake Street, Upper Saddle River, NY 07458

Many of the designations by manufacturers and seller to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks.

Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trademark claim, the

designations have been printed in initial caps or all caps.

10987654321

ISBN 10: 0-13-609704-9

ISBN 13: 978-0-13-609704-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data On File

To Antigone never

dull never boring

the smartest

person I know

This page intentionally left blank

CONTENTS

Notation xiii

Preface xv

About the Author xxiii

Chapter 0 Reader’s Guide 1

0.1 Outline of This Book 2

0.2 A Roadmap for Readers and Instructors 2

0.3 Internet and Web Resources 4

0.4 Standards 5

Chapter 1 Overview 7

1.1 Computer Security Concepts 9

1.2 The OSI Security Architecture 14

1.3 Security Attacks 15

1.4 Security Services 19

1.5 Security Mechanisms 23

1.6 A Model for Network Security 25

1.7 Recommended Reading and Web Sites 27

1.8 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems 29

PART ONE SYMMETRIC CIPHERS 31

Chapter 2 Classical Encryption Techniques 31

2.1 Symmetric Cipher Model 33

2.2 Substitution Techniques 38

2.3 Transposition Techniques 53

2.4 Rotor Machines 55

2.5 Steganography 57

2.6 Recommended Reading and Web Sites 59

2.7 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems 60

Chapter 3 Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard 66

3.1 Block Cipher Principles 68

3.2 The Data Encryption Standard (DES) 77

3.3 A DES Example 85

3.4 The Strength of DES 88

3.5 Differential and Linear Cryptanalysis 89

3.6 Block Cipher Design Principles 92

3.7 Recommended Reading and Web Site 96

3.8 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems 97

Chapter 4 Basic Concepts in Number Theory and Finite Fields 101

4.1 Divisibility and the Division Algorithm 103

4.2 The Euclidean Algorithm 105

v

vi CONTENTS

4.3 Modular Arithmetic 108

4.4 Groups, Rings, and Fields 116

4.5 Finite Fields of the Form GF(p) 120

4.6 Polynomial Arithmetic 122

4.7 Finite Fields of the Form GF(2

n

) 129

4.8 Recommended Reading and Web Sites 141

4.9 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems 141

Appendix 4A The Meaning of mod 144

Chapter 5 Advanced Encryption Standard 47

5.1 The Origins AES 148

5.2 AES Structure 150

5.3 AES Round Functions 155

5.4 AES Key Expansion 166

5.5 An AES Example 169

5.6 AES Implementation 174

5.7 Recommended Reading and Web Sites 178

5.8 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems 179

Appendix 5A Polynomials with Coefficients in GF(2

8

) 180

Appendix 5B Simplified AES 183

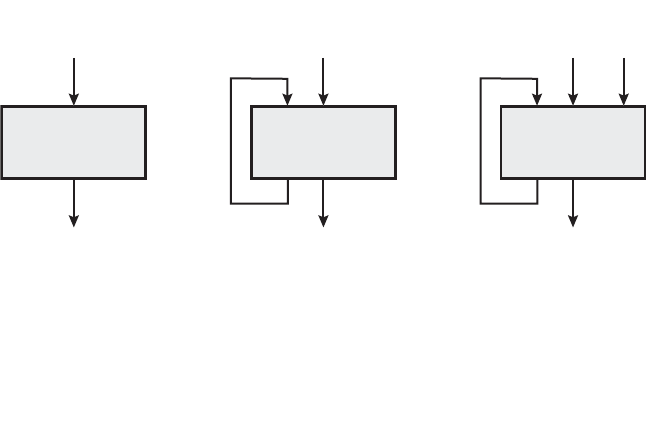

Chapter 6 Block Cipher Operation 192

6.1 Multiple Encryption and Triple DES 193

6.2 Electronic Codebook Mode 198

6.3 Cipher Block Chaining Mode 201

6.4 Cipher Feedback Mode 203

6.5 Output Feedback Mode 205

6.6 Counter Mode 206

6.7 XTS Mode for Block-Oriented Storage Devices 210

6.8 Recommended Web Site 214

6.9 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems 214

Chapter 7 Pseudorandom Number Generation and Stream Ciphers 218

7.1 Principles of Pseudorandom Number Generation 219

7.2 Pseudorandom Number Generators 226

7.3 Pseudorandom Number Generation Using a Block Cipher 229

7.4 Stream Ciphers 232

7.5 RC4 234

7.6 True Random Numbers 237

7.7 Recommended Reading 238

7.8 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems 239

PART TWO ASYMMETRIC CIPHERS 243

Chapter 8 More Number Theory 243

8.1 Prime Numbers 245

8.2 Fermat’s and Euler’s Theorems 248

8.3 Testing for Primality 251

8.4 The Chinese Remainder Theorem 254

CONTENTS vii

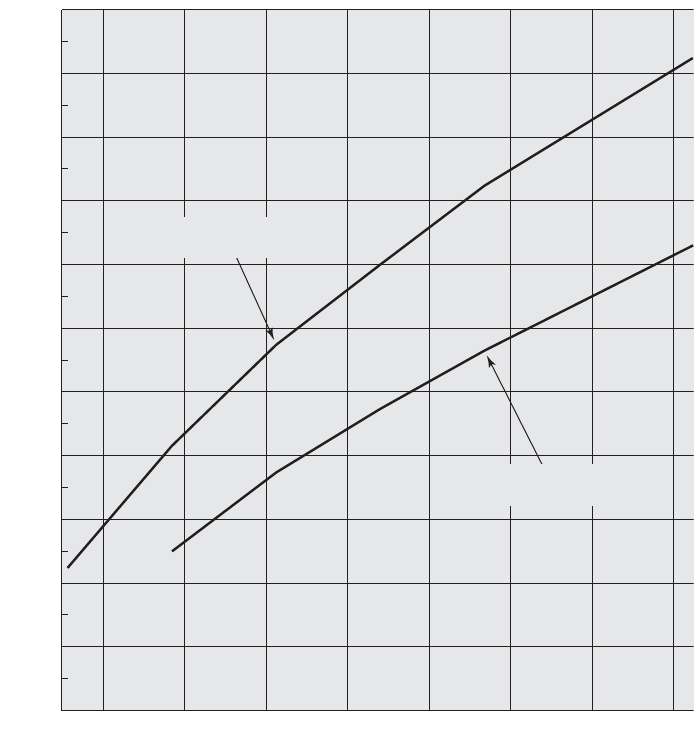

8.5 Discrete Logarithms 257

8.6 Recommended Reading and Web Sites 262

8.7 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems 263

Chapter 9 Public-Key Cryptography and RSA 266

9.1 Principles of Public-Key Cryptosystems 269

9.2 The RSA Algorithm 277

9.3 Recommended Reading and Web Sites 291

9.4 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems 291

Appendix 9A Proof of the RSA Algorithm 296

Appendix 9B The Complexity of Algorithms 297

Chapter 10 Other Public-Key Cryptosystems 300

10.1 Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange 301

10.2 ElGamal Cryptosystem 305

10.3 Elliptic Curve Arithmetic 308

10.4 Elliptic Curve Cryptography 317

10.5 Pseudorandom Number Generation Based on an Asymmetric Cipher 321

10.6 Recommended Reading and Web Sites 323

10.7 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems 324

PART THREE CRYPTOGRAPHIC DATA INTEGRITY ALGORITHMS 327

Chapter 11 Cryptographic Hash Functions 327

11.1 Applications of Cryptographic Hash Functions 329

11.2 Two Simple Hash Functions 333

11.3 Requirements and Security 335

11.4 Hash Functions Based on Cipher Block Chaining 341

11.5 Secure Hash Algorithm (SHA) 342

11.6 SHA-3 352

11.7 Recommended Reading and Web Sites 353

11.8 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems 353

Appendix 11A Mathematical Basis of Birthday Attack 356

Chapter 12 Message Authentication Codes 362

12.1 Message Authentication Requirements 364

12.2 Message Authentication Functions 365

12.3 Message Authentication Codes 372

12.4 Security of MACs 374

12.5 MACs Based on Hash Functions: HMAC 375

12.6 MACs Based on Block Ciphers: DAA and CMAC 380

12.7 Authenticated Encryption: CCM and GCM 383

12.8 Pseudorandom Number Generation Using Hash Functions and MACs 389

12.9 Recommended Reading 392

12.10 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems 393

Chapter 13 Digital Signatures 395

13.1 Digital Signatures 396

13.2 ElGamal Digital Signature Scheme 400

viii CONTENTS

13.3 Schnorr Digital Signature Scheme 402

13.4 Digital Signature Standard (DSS) 403

13.5 Recommended Reading and Web Sites 406

13.6 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems 407

PART FOUR MUTUAL TRUST 410

Chapter 14 Key Management and Distribution 410

14.1 Symmetric Key Distribution Using Symmetric Encryption 412

14.2 Symmetric Key Distribution Using Asymmetric Encryption 421

14.3 Distribution of Public Keys 423

14.4 X.509 Certificates 428

14.5 Public Key Infrastructure 436

14.6 Recommended Reading and Web Sites 438

14.7 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems 439

Chapter 15 User Authentication Protocols 444

15.1 Remote User Authentication Principles 445

15.2 Remote User Authentication Using Symmetric Encryption 448

15.3 Kerberos 452

15.4 Remote User Authentication Using Asymmetric Encryption 470

15.5 Federated Identity Management 472

15.6 Recommended Reading and Web Sites 478

15.7 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems 479

Appendix 15A Kerberos Encryption Techniques 481

PART FIVE NETWORK AND INTERNET SECURITY 485

Chapter 16 Transport-Level Security 485

16.1 Web Security Issues 486

16.2 Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) 489

16.3 Transport Layer Security (TLS) 502

16.4 HTTPS 506

16.5 Secure Shell (SSH) 508

16.6 Recommended Reading and Web Sites 519

16.7 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems 519

Chapter 17 Wireless Network Security 521

17.1 IEEE 802.11 Wireless LAN Overview 523

17.2 IEEE 802.11i Wireless LAN Security 529

17.3 Wireless Application Protocol Overview 543

17.4 Wireless Transport Layer Security 550

17.5 WAP End-to-End Security 560

17.6 Recommended Reading and Web Sites 563

17.7 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems 563

Chapter 18 Electronic Mail Security 567

18.1 Pretty Good Privacy (PGP) 568

18.2 S/MIME 587

CONTENTS ix

18.3 DomainKeys Identified Mail (DKIM) 603

18.4 Recommended Web Sites 610

18.5 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems 611

Appendix 18A Radix-64 Conversion 612

Chapter 19 IP Security 615

19.1 IP Security Overview 616

19.2 IP Security Policy 622

19.3 Encapsulating Security Payload 627

19.4 Combining Security Associations 634

19.5 Internet Key Exchange 638

19.6 Cryptographic Suites 647

19.7 Recommended Reading and Web Sites 648

19.8 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems 649

APPENDICES 651

Appendix A Projects for Teaching Cryptography and Network Security 651

A.1 Sage Computer Algebra Projects 652

A.2 Hacking Project 653

A.3 Block Cipher Projects 653

A.4 Laboratory Exercises 654

A.5 Research Projects 654

A.6 Programming Projects 655

A.7 Practical Security Assessments 655

A.8 Writing Assignments 655

A.9 Reading/Report Assignments 656

Appendix B Sage Examples 657

B.1 Chapter 2: Classical Encryption Techniques 659

B.2 Chapter 3: Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard 662

B.3 Chapter 4: Basic Concepts in Number Theory and Finite Fields 666

B.4 Chapter 5:Advanced Encryption Standard 673

B.5 Chapter 6: Pseudorandom Number Generation and Stream Ciphers 678

B.6 Chapter 8: Number Theory 680

B.6 Chapter 9: Public-Key Cryptography and RSA 685

B.7 Chapter 10: Other Public-Key Cryptosystems 688

B.8 Chapter 11: Cryptographic Hash Functions 693

B.9 Chapter 13: Digital Signatures 695

References 699

Index 711

ONLINE CHAPTERS

PART SIX SYSTEM SECURITY

Chapter 20 Intruders

20.1 Intruders

20.2 Intrusion Detection

x CONTENTS

20.3 Password Management

20.4 Recommended Reading and Web Sites

20.5 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems

Appendix 20A The Base-Rate Fallacy

Chapter 21 Malicious Software

21.1 Types of Malicious Software

21.2 Viruses

21.3 Virus Countermeasures

21.4 Wo r m s

21.5 Distributed Denial of Service Attacks

21.6 Recommended Reading and Web Sites

21.7 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems

Chapter 22 Firewalls

22.1 The Need for Firewalls

22.2 Firewall Characteristics

22.3 Types of Firewalls

22.4 Firewall Basing

22.5 Firewall Location and Configurations

22.6 Recommended Reading and Web Sites

22.7 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems

PART SEVEN LEGAL AND ETHICAL ISSUES

Chapter 23 Legal and Ethical Issues

23.1 Cybercrime and Computer Crime

23.2 Intellectual Property

23.3 Privacy

23.4 Ethical Issues

23.5 Recommended Reading and Web Sites

23.6 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems

ONLINE APPENDICES

WilliamStallings.com/Crypto/Crypto5e.html

Appendix C Sage Problems

C.1 Getting Started with Sage

C.2 Programming with Sage

C.3 Chapter 2: Classical Encryption Techniques

C.4 Chapter 3: Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard

C.5 Chapter 4: Basic Concepts in Number Theory and Finite Fields

C.6 Chapter 5:Advanced Encryption Standard

C.7 Chapter 7: Pseudorandom Number Generation and Stream Ciphers

C.8 Chapter 8: Number Theory

C.9 Chapter 9: Public-Key Cryptography and RSA

C.10 Chapter 10: Other Public-Key Cryptosystems

C.11 Chapter 11: Cryptographic Hash Functions

C.12 Chapter 13: Digital Signatures

CONTENTS xi

Appendix D Standards and Standards-Setting Organizations

D.1 The Importance of Standards

D.2 Internet Standards and the Internet Society

D.3 National Institute of Standards and Technology

Appendix E Basic Concepts from Linear Algebra

E.1 Operations on Vectors and Matrices

E.2 Linear Algebra Operations over Z

n

Appendix F Measures of Security and Secrecy

F. 1 Perfect Secrecy

F. 2 Information and Entropy

F. 3 Entropy and Secrecy

Appendix G Simplified DES

G.1 Overview

G.2 S-DES Key Generation

G.3 S-DES Encryption

G.4 Analysis of Simplified DES

G.5 Relationship to DES

Appendix H Evaluation Criteria for AES

H.1 The Origins of AES

H.2 AES Evaluation

Appendix I More on Simplified AES

I.1 Arithmetic in GF(2

4

)

I.2 The Mix Column Function

Appendix J Knapsack Public-Key Algorithm

J.1 The Knapsack Problem

J.2 The Knapsack Cryptosystem

J.3 Example

Appendix K Proof of the Digital Signature Algorithm

Appendix L TCP/IP and OSI

L.1 Protocols and Protocol Architectures

L.2 The TCP/IP Protocol Architecture

L.3 The Role of an Internet Protocol

L.4 IPv4

L.5 IPv6

L.6 The OSI Protocol Architecture

Appendix M Java Cryptographic APIs

M.1 Introduction

M.2 JCA and JCE Architecture

M.3 JCA Classes

M.4 JCE Classes

M.5 Conclusion and References

xii CONTENTS

M.6 Using the Cryptographic Application

M.7 JCA/JCE Cryptography Example

Appendix N The Whirlpool Hash Function

N.1 Whirlpool Hash Structure

N.2 Block Cipher W

N.3 Performance of Whirlpool

Appendix O Data Compression Using ZIP

O.1 Compression Algorithm

O.2 Decompression Algorithm

Appendix P PGP Random Number Generation

P. 1 True Random Numbers

P. 2 Pseudorandom Numbers

Appendix Q International Reference Alphabet

Glossary

NOTATION

Symbol Expression Meaning

D, K D1K, Y2

Symmetric decryption of ciphertext using secret key KY

D, PR

a

D1PR

a

, Y2 Asymmetric decryption of ciphertext using A’s private key PR

a

Y

D, PU

a

D1PU

a

, Y2 Asymmetric decryption of ciphertext using A’s public key PU

a

Y

E, K E1K, X2

Symmetric encryption of plaintext using secret key KX

E, PR

a

E( , )XPR

a

Asymmetric encryption of plaintext using A’s private key PR

a

X

E, PU

a

E( , )XPU

a

Asymmetric encryption of plaintext using A’s public key PU

a

X

K

Secret key

PR

a

Private key of user A

PU

a

Public key of user A

MAC,

K

MAC(K, X)

Message authentication code of message using secret key

KX

GF(p)

The finite field of order , where is prime. The field is defined as

the set together with the arithmetic operations modulo .pZ

p

pp

GF(2

n

)

The finite field of order 2

n

Z

n

Set of nonnegative integers less than n

gcd

gcd( )i, j

Greatest common divisor; the largest positive integer that divides

both and with no remainder on division.ji

mod mod ma Remainder after division of by ma

mod, K

(mod )ma K b mod mod mm = ba

mod, [

(mod )ma [ b mod mod mm Z ba

dlog

dlog

a, p

(b) Discrete logarithm of the number for the base (mod )pab

w

f(n)

The number of positive integers less than and relatively prime to .

This is Euler’s totient function.

nn

©

a

n

i = 1

a

i

a

1

+ a

2

+

Á

+ a

n

ß

q

n

i = 1

a

i

a

1

* a

2

*

Á

* a

n

Even the natives have difficulty mastering this peculiar vocabulary.

—The Golden Bough, Sir James George Frazer

xiii

xiv NOTATION

| i | j

i divides , which means that there is no remainder when is divided

by i

jj

|, | | a |

Absolute value of a

|| x || y

concatenated with yx

L x L y

is approximately equal to yx

䊝

x

䊝

y

Exclusive-OR of and for single-bit variables;

Bitwise exclusive-OR of and for multiple-bit variablesyx

yx

:,;:x;

The largest integer less than or equal to x

僆

x 僆 S

The element is contained in the set S.x

·

Á , a

k

2

A

·

(a

1

, a

2

,

The integer A corresponds to the sequence of integers

(, )a

2

, Á , a

k

a

1

xv

PREFACE

“The tie, if I might suggest it, sir, a shade more tightly knotted. One aims at the

perfect butterfly effect. If you will permit me —”

“What does it matter, Jeeves, at a time like this? Do you realize that

Mr. Little’s domestic happiness is hanging in the scale?”

“There is no time, sir, at which ties do not matter.”

—Very Good, Jeeves! P. G.Wodehouse

In this age of universal electronic connectivity, of viruses and hackers, of electronic eaves-

dropping and electronic fraud, there is indeed no time at which security does not matter.Two

trends have come together to make the topic of this book of vital interest. First, the explosive

growth in computer systems and their interconnections via networks has increased the

dependence of both organizations and individuals on the information stored and communi-

cated using these systems. This, in turn, has led to a heightened awareness of the need to

protect data and resources from disclosure, to guarantee the authenticity of data and

messages, and to protect systems from network-based attacks. Second, the disciplines of

cryptography and network security have matured, leading to the development of practical,

readily available applications to enforce network security.

OBJECTIVES

It is the purpose of this book to provide a practical survey of both the principles and practice

of cryptography and network security. In the first part of the book, the basic issues to be

addressed by a network security capability are explored by providing a tutorial and survey of

cryptography and network security technology. The latter part of the book deals with the

practice of network security: practical applications that have been implemented and are in

use to provide network security.

The subject, and therefore this book, draws on a variety of disciplines. In particular, it is

impossible to appreciate the significance of some of the techniques discussed in this book

without a basic understanding of number theory and some results from probability theory.

Nevertheless, an attempt has been made to make the book self-contained.The book presents

not only the basic mathematical results that are needed but provides the reader with an

intuitive understanding of those results. Such background material is introduced as needed.

This approach helps to motivate the material that is introduced, and the author considers

this preferable to simply presenting all of the mathematical material in a lump at the begin-

ning of the book.

INTENDED AUDIENCE

The book is intended for both academic and a professional audiences. As a textbook, it is

intended as a one-semester undergraduate course in cryptography and network security for

computer science, computer engineering, and electrical engineering majors. It covers the

xvi PREFACE

material in IAS2 Security Mechanisms, a core area in the Information Technology body of

knowledge; NET4 Security, another core area in the Information Technology body of knowl-

edge; and IT311, Cryptography, an advanced course; these subject areas are part of the

ACM/IEEE Computer Society Computing Curricula 2005.

The book also serves as a basic reference volume and is suitable for self-study.

PLAN OF THE BOOK

The book is divided into seven parts (see Chapter 0 for an overview):

• Symmetric Ciphers

• Asymmetric Ciphers

• Cryptographic Data Integrity Algorithms

• Mutual Trust

• Network and Internet Security

• System Security

• Legal and Ethical Issues

The book includes a number of pedagogic features, including the use of the computer

algebra system Sage and numerous figures and tables to clarify the discussions. Each chapter

includes a list of key words, review questions, homework problems, suggestions for further

reading, and recommended Web sites. The book also includes an extensive glossary, a list

of frequently used acronyms, and a bibliography. In addition, a test bank is available to

instructors.

ONLINE DOCUMENTS FOR STUDENTS

For this new edition, a tremendous amount of original supporting material has been made

available online, in the following categories.

• Online chapters: To limit the size and cost of the book, four chapters of the book

are provided in PDF format. This includes three chapters on computer security and

one on legal and ethical issues. The chapters are listed in this book’s table of

contents.

• Online appendices: There are numerous interesting topics that support material

found in the text but whose inclusion is not warranted in the printed text. A total of

fifteen online appendices cover these topics for the interested student. The appen-

dices are listed in this book’s table of contents.

• Homework problems and solutions: To aid the student in understanding the material,

a separate set of homework problems with solutions are available. These enable the

students to test their understanding of the text.

• Key papers: Twenty-four papers from the professional literature, many hard to find,

are provided for further reading.

• Supporting documents: A variety of other useful documents are referenced in the text

and provided online.

• Sage code: The Sage code from the examples in Appendix B in case the student wants

to play around with the examples.

PREFACE xvii

Purchasing this textbook now grants the reader six months of access to this online

material. See the access card bound into the front of this book for details.

INSTRUCTIONAL SUPPORT MATERIALS

To support instructors, the following materials are provided:

• Solutions Manual: Solutions to end-of-chapter Review Questions and Problems.

• Projects Manual: Suggested project assignments for all of the project categories listed

below.

• PowerPoint Slides: A set of slides covering all chapters, suitable for use in lecturing.

• PDF Files: Reproductions of all figures and tables from the book.

• Test Bank: A chapter-by-chapter set of questions.

All of these support materials are available at the Instructor Resource Center

(IRC) for this textbook, which can be reached via personhighered.com/stallings or by

clicking on the button labeled “Book Info and More Instructor Resources” at this book’s

Web Site WilliamStallings.com/Crypto/Crypto5e.html. To gain access to the IRC,

please contact your local Prentice Hall sales representative via pearsonhighered.com/

educator/replocator/requestSalesRep.page or call Prentice Hall Faculty Services at

1-800-526-0485.

INTERNET SERVICES FOR INSTRUCTORS AND STUDENTS

There is a Web site for this book that provides support for students and instructors. The site

includes links to other relevant sites, transparency masters of figures and tables in the book

in PDF (Adobe Acrobat) format, and PowerPoint slides. The Web page is at

WilliamStallings.com/Crypto/Crypto5e.html. For more information, see Chapter 0.

New to this edition is a set of homework problems with solutions available at this Web

site. Students can enhance their understanding of the material by working out the solutions

to these problems and then checking their answers.

An Internet mailing list has been set up so that instructors using this book can

exchange information, suggestions, and questions with each other and with the author. As

soon as typos or other errors are discovered, an errata list for this book will be available at

WilliamStallings.com. In addition, the Computer Science Student Resource site at

WilliamStallings.com/StudentSupport.html provides documents, information, and useful

links for computer science students and professionals.

PROJECTS AND OTHER STUDENT EXERCISES

For many instructors, an important component of a cryptography or security course is a pro-

ject or set of projects by which the student gets hands-on experience to reinforce concepts

from the text. This book provides an unparalleled degree of support, including a projects

component in the course. The IRC not only includes guidance on how to assign and structure

xviii PREFACE

the projects, but it also includes a set of project assignments that covers a broad range of

topics from the text.

• Sage Projects: Described in the next section.

• Hacking Project: This exercise is designed to illuminate the key issues in intrusion

detection and prevention.

• Block Cipher Projects: This is a lab that explores the operation of the AES encryption

algorithm by tracing its execution, computing one round by hand, and then exploring

the various block cipher modes of use. The lab also covers DES. In both cases, an

online Java applet is used (or can be downloaded) to execute AES or DES.

• Lab Exercises: A series of projects that involve programming and experimenting with

concepts from the book.

• Research Projects: A series of research assignments that instruct the student to

research a particular topic on the Internet and write a report.

• Programming Projects: A series of programming projects that cover a broad range of

topics and that can be implemented in any suitable language on any platform.

• Practical Security Assessments: A set of exercises to examine current infrastructure

and practices of an existing organization.

• Writing Assignments: A set of suggested writing assignments organized by chapter.

• Reading/Report Assignments: A list of papers in the literature — one for each

chapter — that can be assigned for the student to read and then write a short report.

See Appendix A for details.

THE SAGE COMPUTER ALGEBRA SYSTEM

One of the most important new features for this edition is the use of Sage for cryptographic

examples and homework assignments. Sage is an open-source, multiplatform, freeware pack-

age that implements a very powerful, flexible, and easily learned mathematics and computer

algebra system. Unlike competing systems (such as Mathematica, Maple, and MATLAB),

there are no licensing agreements or fees involved. Thus, Sage can be made available on

computers and networks at school, and students can individually download the software to

their own personal computers for use at home. Another advantage of using Sage is that

students learn a powerful, flexible tool that can be used for virtually any mathematical

application, not just cryptography.

The use of Sage can make a significant difference to the teaching of the mathematics

of cryptographic algorithms. This book provides a large number of examples of the use of

Sage covering many cryptographic concepts in Appendix B.

Appendix C lists exercises in each of these topic areas to enable the student to gain

hands-on experience with cryptographic algorithms. This appendix is available to instruc-

tors at the IRC for this book. Appendix C includes a section on how to download and get

started with Sage, a section on programming with Sage, and includes exercises that can be

assigned to students in the following categories:

• Chapter 2 — Classical Encryption: Affine ciphers and the Hill cipher.

• Chapter 3 — Block Ciphers And The Data Encryption Standard: Exercises based on

SDES.

PREFACE xix

• Chapter 4 — Basic Concepts In Number Theory And Finite Fields: Euclidean and

extended Euclidean algorithms, polynomial arithmetic, and GF(24).

• Chapter 5 — Advanced Encryption Standard: Exercise based on SAES.

• Chapter 6 — Pseudorandom Number Generation And Stream Ciphers: Blum Blum

Shub, linear congruential generator, and ANSI X9.17 PRNG.

• Chapter 8 — Number Theory: Euler’s Totient function, Miller Rabin, factoring, modular

exponentiation, discrete logarithm, and Chinese remainder theorem.

• Chapter 9 — Public-Key Cryptography And RSA: RSA encrypt/decrypt and signing.

• Chapter 10 — Other Public-Key Cryptosystems: Diffie-Hellman, elliptic curve

• Chapter 11 — Cryptographic Hash Functions: Number-theoretic hash function.

• Chapter 13 — Digital Signatures: DSA.

WHAT’S NEW IN THE FIFTH EDITION

The changes for this new edition of Cryptography and Network Security are more substantial

and comprehensive than those for any previous revision.

In the three years since the fourth edition of this book was published, the field has seen

continued innovations and improvements. In this new edition, I try to capture these changes

while maintaining a broad and comprehensive coverage of the entire field. To begin this

process of revision, the fourth edition was extensively reviewed by a number of professors

who teach the subject. In addition, a number of professionals working in the field reviewed

individual chapters. The result is that, in many places, the narrative has been clarified and

tightened, and illustrations have been improved. Also, a large number of new “field-tested”

problems have been added.

One obvious change to the book is a revision in the organization, which makes for a

clearer presentation of related topics. There is a new Part Three, which pulls together all of

the material on cryptographic algorithms for data integrity, including cryptographic hash

functions, message authentication codes, and digital signatures.The material on key manage-

ment and exchange, previously distributed in several places in the book, is now organized in

a single chapter, as is the material on user authentication.

Beyond these refinements to improve pedagogy and user friendliness, there have been

major substantive changes throughout the book. Highlights include:

• Euclidean and extended Euclidean algorithms (revised): These algorithms are impor-

tant for numerous cryptographic functions and algorithms. The material on the

Euclidean and extended Euclidean algorithms for integers and for polynomials has

been completely rewritten to provide a clearer and more systematic treatment.

• Advanced Encryption Standard (revised): AES has emerged as the dominant symmetric

encryption algorithm, used in a wide variety of applications. Accordingly, this edition has

dramatically expanded the resources for learning about and understanding this impor-

tant standard.The chapter on AES has been revised and expanded, with additional illus-

trations and a detailed example, to clarify the presentation. Examples and assignments

using Sage have been added.And the book now includes an AES cryptography lab,

which enables the student to gain hands-on experience with AES cipher internals and

modes of use. The lab makes use of an AES calculator applet, available at this book’s

Web site, that can encrypt or decrypt test data values using the AES block cipher.

xx PREFACE

• Block Cipher Modes of Operation (revised): The material in Chapter 6 on modes of

operation has been expanded and the illustrations redrawn for greater clarity.

• Pseudorandom number generation and pseudorandom functions (revised): The treat-

ment of this important topic has been expanded, with the addition of new material on

the use of symmetric encryption algorithms and cryptographic hash functions to con-

struct pseudorandom functions.

• ElGamal encryption and digital signature (new): New sections have been added on

this popular public-key algorithm.

• Cryptographic hash functions and message authentication codes (revised): The mater-

ial on hash functions and MAC has been revised and reorganized to provide a clearer

and more systematic treatment.

• SHA-3 (new): Although the SHA-3 algorithm has yet to be selected, it is important

for the student to have a grasp of the design criteria for this forthcoming cryptograph-

ic hash standard.

• Authenticated encryption (new): The book covers the important new algorithms,

CCM and GCM, which simultaneously provide confidentiality and data integrity.

• Key management and distribution (revised): In the fourth edition, these topics were

scattered across three chapters. In the fifth edition, the material is revised and consoli-

dated into a single chapter to provide a unified, systematic treatment.

• Remote user authentication (revised): In the fourth edition, this topic was covered in

parts of two chapters. In the fifth edition the material is revised and consolidated into

a single chapter to provide a unified, systematic treatment.

• Federated identity (new): A new section covers this common identity management

scheme across multiple enterprises and numerous applications and supporting many

thousands, even millions, of users.

• HTTPS (new): A new section covers this protocol for providing secure communica-

tion between Web browser and Web server.

• Secure shell (new): SSH, one of the most pervasive applications of encryption tech-

nology, is covered in a new section.

• DomainKeys Identified Mail (new): A new section covers DKIM, which has become

the standard means of authenticating e-mail to counter spam.

• Wireless network security (new): A new chapter covers this important area of net-

work security. The chapter deals with the IEEE 802.11 (WiFi) security standard for

wireless local area networks; and the Wireless Application Protocol (WAP) security

standard for communication between a mobile Web browser and a Web server.

• IPsec (revised): The chapter on IPsec has been almost completely rewritten. It now

covers IPsecv3 and IKEv2. In addition, the presentation has been revised to improve

clarity and breadth.

• Legal and ethical issues (new): A new online chapter covers these important

topics.

• Online appendices (new): Fifteen online appendices provide additional breadth and

depth for the interested student on a variety of topics.

• Sage examples and problems (new): As mentioned, this new edition makes use of the

open-source, freeware Sage computer algebra application to enable students to have

hands-on experience with a variety of cryptographic algorithms.

PREFACE xxi

With each new edition it is a struggle to maintain a reasonable page count while adding

new material. In part, this objective is realized by eliminating obsolete material and tighten-

ing the narrative. For this edition, chapters and appendices that are of less general interest

have been moved online as individual PDF files. This has allowed an expansion of material

without the corresponding increase in size and price.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This new edition has benefited from review by a number of people who gave generously of

their time and expertise. The following people reviewed all or a large part of the manuscript:

Marius Zimand (Towson State University), Shambhu Upadhyaya (University of Buffalo),

Nan Zhang (George Washington University), Dongwan Shin (New Mexico Tech), Michael

Kain (Drexel University), William Bard (University of Texas), David Arnold (Baylor Uni-

versity), Edward Allen (Wake Forest University), Michael Goodrich (UC-Irvine), Xunhua

Wang (James Madison University), Xianyang Li (Illinois Institute of Technology), and Paul

Jenkins (Brigham Young University).

Thanks also to the many people who provided detailed technical reviews of one or

more chapters: Martin Bealby, Martin Hlavac (Department of Algebra, Charles University

in Prague, Czech Republic), Martin Rublik (BSP Consulting and University of Economics in

Bratislava), Rafael Lara (President of Venezuela’s Association for Information Security and

Cryptography Research), Amitabh Saxena, and Michael Spratte (Hewlett-Packard Com-

pany). I would especially like to thank Nikhil Bhargava (IIT Delhi) for providing detailed

reviews of various chapters of the book.

Joan Daemen kindly reviewed the chapter on AES. Vincent Rijmen reviewed the

material on Whirlpool. Edward F. Schaefer reviewed the material on simplified AES.

Nikhil Bhargava (IIT Delhi) developed the set of online homework problems and

solutions. Dan Shumow of Microsoft and the University of Washington developed all of the

Sage examples and assignments in Appendices B and C. Professor Sreekanth Malladi of

Dakota State University developed the hacking exercises. Lawrie Brown of the Australian

Defence Force Academy provided the AES/DES block cipher projects and the security

assessment assignments.

Sanjay Rao and Ruben Torres of Purdue University developed the laboratory exercis-

es that appear in the IRC.The following people contributed project assignments that appear

in the instructor’s supplement: Henning Schulzrinne (Columbia University); Cetin Kaya Koc

(Oregon State University); and David Balenson (Trusted Information Systems and George

Washington University). Kim McLaughlin developed the test bank.

Finally, I would like to thank the many people responsible for the publication of the

book, all of whom did their usual excellent job.This includes my editor Tracy Dunkelberger,

her assistant Melinda Hagerty, and production manager Rose Kernan. Also, Jake Warde of

Warde Publishers managed the reviews.

With all this assistance, little remains for which I can take full credit. However, I am

proud to say that, with no help whatsoever, I selected all of the quotations.

This page intentionally left blank

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

William Stallings has made a unique contribution to understanding the broad sweep of tech-

nical developments in computer security, computer networking and computer architecture.

He has authored 17 titles, and counting revised editions, a total of 42 books on various

aspects of these subjects. His writings have appeared in numerous ACM and IEEE publica-

tions, including the Proceedings of the IEEE and ACM Computing Reviews.

He has 11 times received the award for the best Computer Science textbook of the

year from the Text and Academic Authors Association.

In over 30 years in the field, he has been a technical contributor, technical manager,

and an executive with several high-technology firms. He has designed and implemented both

TCP/IP-based and OSI-based protocol suites on a variety of computers and operating

systems, ranging from microcomputers to mainframes. As a consultant, he has advised

government agencies, computer and software vendors, and major users on the design, selec-

tion, and use of networking software and products.

He created and maintains the Computer Science Student Resource Site at WilliamStalI-

ings.com/StudentSupport.html.This site provides documents and links on a variety of subjects

of general interest to computer science students (and professionals). He is a member of the

editorial board of Cryptologia, a scholarly journal devoted to all aspects of cryptology.

Dr. Stallings holds a PhD from M.I.T. in Computer Science and a B.S. from Notre

Dame in electrical engineering.

xxiii

This page intentionally left blank

2 CHAPTER 0 / READER’S GUIDE

The art of war teaches us to rely not on the likelihood of the enemy’s not coming, but

on our own readiness to receive him; not on the chance of his not attacking, but rather

on the fact that we have made our position unassailable.

—The Art of War, Sun Tzu

This book, with its accompanying Web site, covers a lot of material. Here we give the

reader an overview.

0.1 OUTLINE OF THIS BOOK

Following an introductory chapter, Chapter 1, the book is organized into seven parts:

Part One: Symmetric Ciphers: Provides a survey of symmetric encryption, including clas-

sical and modern algorithms. The emphasis is on the two most important algo-

rithms, the Data Encryption Standard (DES) and the Advanced Encryption

Standard (AES). This part also covers the most important stream encryption

algorithm, RC4, and the important topic of pseudorandom number generation.

Part Two: Asymmetric Ciphers: Provides a survey of public-key algorithms,

including RSA (Rivest-Shamir-Adelman) and elliptic curve.

Part Three: Cryptographic Data Integrity Algorithms: Begins with a survey of crypto-

graphic hash functions. This part then covers two approaches to data

integrity that rely on cryptographic hash functions: message authentica-

tion codes and digital signatures.

Part Four: Mutual Trust: Covers key management and key distribution topics and

then covers user authentication techniques.

Part Five: Network Security and Internet Security: Examines the use of cryptographic

algorithms and security protocols to provide security over networks and the

Internet. Topics covered include transport-level security, wireless network

security, e-mail security, and IP security.

Part Six: System Security: Deals with security facilities designed to protect a

computer system from security threats, including intruders, viruses, and

worms. This part also looks at firewall technology.

Part Seven: Legal and Ethical Issues: Deals with the legal and ethical issues related

to computer and network security.

A number of online appendices at this book’s Web site cover additional topics

relevant to the book.

0.2 A ROADMAP FOR READERS AND INSTRUCTORS

Subject Matter

The material in this book is organized into four broad categories:

• Cryptographic algorithms: This is the study of techniques for ensuring the

secrecy and/or authenticity of information. The three main areas of study in

0.2 / A ROADMAP FOR READERS AND INSTRUCTORS 3

this category are: (1) symmetric encryption, (2) asymmetric encryption, and

(3) cryptographic hash functions, with the related topics of message authenti-

cation codes and digital signatures.

• Mutual trust: This is the study of techniques and algorithms for providing

mutual trust in two main areas. First, key management and distribution deals

with establishing trust in the encryption keys used between two communicating

entities. Second, user authentication deals with establishing trust in the identity

of a communicating partner.

• Network security: This area covers the use of cryptographic algorithms in

network protocols and network applications.

• Computer security: In this book, we use this term to refer to the security of

computers against intruders (e.g., hackers) and malicious software (e.g.,

viruses). Typically, the computer to be secured is attached to a network, and

the bulk of the threats arise from the network.

The first two parts of the book deal with two distinct cryptographic approaches:

symmetric cryptographic algorithms and public-key, or asymmetric, cryptographic

algorithms. Symmetric algorithms make use of a single key shared by two parties.

Public-key algorithms make use of two keys: a private key known only to one party

and a public key available to other parties.

Topic Ordering

This book covers a lot of material. For the instructor or reader who wishes a shorter

treatment, there are a number of opportunities.

To thoroughly cover the material in the first three parts, the chapters should be

read in sequence. With the exception of the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES),

none of the material in Part One requires any special mathematical background. To

understand AES, it is necessary to have some understanding of finite fields. In turn,

an understanding of finite fields requires a basic background in prime numbers and

modular arithmetic.Accordingly, Chapter 4 covers all of these mathematical prelim-

inaries just prior to their use in Chapter 5 on AES. Thus, if Chapter 5 is skipped, it is

safe to skip Chapter 4 as well.

Chapter 2 introduces some concepts that are useful in later chapters of Part

One. However, for the reader whose sole interest is contemporary cryptography,

this chapter can be quickly skimmed. The two most important symmetric crypto-

graphic algorithms are DES and AES, which are covered in Chapters 3 and 5,

respectively.

Chapter 6 covers specific techniques for using what are known as block sym-

metric ciphers. Chapter 7 covers stream ciphers and random number generation.

These two chapters may be skipped on an initial reading, but this material is refer-

enced in later parts of the book.

For Part Two, the only additional mathematical background that is needed is in

the area of number theory, which is covered in Chapter 8.The reader who has skipped

Chapters 4 and 5 should first review the material on Sections 4.1 through 4.3.

The two most widely used general-purpose public-key algorithms are RSA

and elliptic curve, with RSA enjoying wider acceptance.The reader may wish to skip

the material on elliptic curve cryptography in Chapter 10, at least on a first reading.

4 CHAPTER 0 / READER’S GUIDE

In Part Three, the topics in Sections 12.6 and 12.7 are of lesser importance.

Parts Four, Five, and Six are relatively independent of each other and can be

read in any order.These three parts assume a basic understanding of the material in

Parts One, Two, and Three. The four chapters of Part Five, on network and Internet

security, are relatively independent of one another and can be read in any order.

0.3 INTERNET AND WEB RESOURCES

There are a number of resources available on the Internet and the Web to support

this book and to help readers keep up with developments in this field.

Web Sites for This Book

There is a Web page for this book at WilliamStallings.com/Crypto/Crypto5e.html.

The site includes the following:

• Useful Web sites: There are links to other relevant Web sites, organized by

chapter, including the sites listed throughout this book.

• Errata sheet: An errata list for this book will be maintained and updated as

needed. Please e-mail any errors that you spot to me. Errata sheets for my

other books are at WilliamStallings.com.

• Figures: All of the figures in this book are provided in PDF (Adobe Acrobat)

format.

• Tables: All of the tables in this book are provided in PDF format.

• Slides: A set of PowerPoint slides are provided, organized by chapter.

• Cryptography and network security courses: There are links to home pages for

courses based on this book; these pages may be useful to other instructors in

providing ideas about how to structure their course.

I also maintain the Computer Science Student Resource Site, at William

Stallings.com/StudentSupport.html. The purpose of this site is to provide docu-

ments, information, and links for computer science students and professionals. Links

and documents are organized into six categories:

• Math: Includes a basic math refresher, a queuing analysis primer, a number

system primer, and links to numerous math sites

• How-to: Advice and guidance for solving homework problems, writing techni-

cal reports, and preparing technical presentations

• Research resources: Links to important collections of papers, technical

reports, and bibliographies

• Miscellaneous: A variety of other useful documents and links.

• Computer science careers: Useful links and documents for those considering a

career in computer science.

• Humor and other diversions: You have to take your mind off your work once

in a while.

0.4 / STANDARDS 5

Other Web Sites

There are numerous Web sites that provide information related to the topics of this

book. In subsequent chapters, pointers to specific Web sites can be found in the

Recommended Reading and Web Sites section. Because the addresses for Web sites

tend to change frequently, the book does not provide URLs. For all of the Web sites

listed in the book, the appropriate link can be found at this book’s Web site. Other

links not mentioned in this book will be added to the Web site over time.

Newsgroups and Forums

A number of USENET newsgroups are devoted to some aspect of cryptography or

network security. As with virtually all USENET groups, there is a high noise-to-signal

ratio, but it is worth experimenting to see if any meet your needs. The most relevant

are as follows:

• sci.crypt.research: The best group to follow. This is a moderated newsgroup

that deals with research topics; postings must have some relationship to the

technical aspects of cryptology.

• sci.crypt: A general discussion of cryptology and related topics.

• sci.crypt.random-numbers: A discussion of cryptographic-strength random

number generators.

• alt.security: A general discussion of security topics.

• comp.security.misc: A general discussion of computer security topics.

• comp.security.firewalls: A discussion of firewall products and technology.

• comp.security.announce: News and announcements from CERT.

• comp.risks: A discussion of risks to the public from computers and users.

• comp.virus: A moderated discussion of computer viruses.

In addition, there are a number of forums dealing with cryptography available

on the Internet. Among the most worthwhile are

• Security and Cryptography forum: Sponsored by DevShed. Discusses issues

related to coding, server applications, network protection, data protection,

firewalls, ciphers, and the like.

• Cryptography forum: On Topix. Fairly good focus on technical issues.

• Security forums: On WindowsSecurity.com. Broad range of forums, including

cryptographic theory, cryptographic software, firewalls, and malware.

Links to these forums are provided at this book’s Web site.

0.4 STANDARDS

Many of the security techniques and applications described in this book have

been specified as standards. Additionally, standards have been developed to

cover management practices and the overall architecture of security mechanisms

6 CHAPTER 0 / READER’S GUIDE

and services. Throughout this book, we describe the most important standards in

use or being developed for various aspects of cryptography and network security.

Various organizations have been involved in the development or promotion of

these standards. The most important (in the current context) of these organiza-

tions are as follows:

• National Institute of Standards and Technology: NIST is a U.S. federal agency

that deals with measurement science, standards, and technology related to U.S.

government use and to the promotion of U.S. private-sector innovation.

Despite its national scope, NIST Federal Information Processing Standards

(FIPS) and Special Publications (SP) have a worldwide impact.

• Internet Society: ISOC is a professional membership society with worldwide

organizational and individual membership. It provides leadership in address-

ing issues that confront the future of the Internet and is the organization

home for the groups responsible for Internet infrastructure standards,

including the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) and the Internet

Architecture Board (IAB). These organizations develop Internet standards

and related specifications, all of which are published as Requests for

Comments (RFCs).

• ITU-T: The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) is an international

organization within the United Nations System in which governments and the

private sector coordinate global telecom networks and services The ITU

Telecommunication Standardization Sector (ITU-T) is one of the three sectors

of the ITU. ITU-T’s mission is the production of standards covering all fields of

telecommunications. ITU-T standards are referred to as Recommendations.

• ISO: The International Organization for Standardization (ISO)

1

is a world-

wide federation of national standards bodies from more than 140 countries,

one from each country. ISO is a nongovernmental organization that pro-

motes the development of standardization and related activities with a view

to facilitating the international exchange of goods and services and to devel-

oping cooperation in the spheres of intellectual, scientific, technological, and

economic activity. ISO’s work results in international agreements that are

published as International Standards.

A more detailed discussion of these organizations is contained in Appendix D.

1

ISO is not an acronym (in which case it would be IOS), but it is a word derived from the Greek, meaning

equal.

OVERVIEW

1.1 Computer Security Concepts

A Definition of Computer Security

Examples

The Challenges of Computer Security

1.2 The OSI Security Architecture

1.3 Security Attacks

Passive Attacks

Active Attacks

1.4 Security Services

Authentication

Access Control

Data Confidentiality

Data Integrity

Nonrepudiation

Availability Service

1.5 Security Mechanisms

1.6 A Model for Network Security

1.7 Recommended Reading and Web Sites

1.8 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems

CHAPTER

7

8 CHAPTER 1 / OVERVIEW

KEY POINTS

◆ The Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) security architecture provides

a systematic framework for defining security attacks, mechanisms, and

services.

◆ Security attacks are classified as either passive attacks, which include

unauthorized reading of a message of file and traffic analysis or active

attacks, such as modification of messages or files, and denial of service.

◆ A security mechanism is any process (or a device incorporating such a

process) that is designed to detect, prevent, or recover from a security attack.

Examples of mechanisms are encryption algorithms, digital signatures, and

authentication protocols.

◆ Security services include authentication, access control, data confidentiality,

data integrity, nonrepudiation, and availability.

This book focuses on two broad areas: cryptographic algorithms and protocols, which

have a broad range of applications; and network and Internet security, which rely

heavily on cryptographic techniques.

Cryptographic algorithms and protocols can be grouped into four main areas:

• Symmetric encryption: Used to conceal the contents of blocks or streams of

data of any size, including messages, files, encryption keys, and passwords.

• Asymmetric encryption: Used to conceal small blocks of data, such as encryption

keys and hash function values, which are used in digital signatures.

• Data integrity algorithms: Used to protect blocks of data, such as messages,

from alteration.

• Authentication protocols: These are schemes based on the use of cryptographic

algorithms designed to authenticate the identity of entities.

The field of network and Internet security consists of measures to deter, prevent,

detect, and correct security violations that involve the transmission of informa-

tion. That is a broad statement that covers a host of possibilities. To give you a

feel for the areas covered in this book, consider the following examples of

security violations:

1. User A transmits a file to user B. The file contains sensitive information

(e.g., payroll records) that is to be protected from disclosure. User C, who is

The combination of space, time, and strength that must be considered as the

basic elements of this theory of defense makes this a fairly complicated matter.

Consequently, it is not easy to find a fixed point of departure.

—On War, Carl Von Clausewitz

1.1 / COMPUTER SECURITY CONCEPTS 9

not authorized to read the file, is able to monitor the transmission and capture

a copy of the file during its transmission.

2. A network manager, D, transmits a message to a computer, E, under its man-

agement. The message instructs computer E to update an authorization file to

include the identities of a number of new users who are to be given access to

that computer. User F intercepts the message, alters its contents to add or

delete entries, and then forwards the message to computer E, which accepts

the message as coming from manager D and updates its authorization file

accordingly.

3. Rather than intercept a message, user F constructs its own message with the

desired entries and transmits that message to computer E as if it had come

from manager D. Computer E accepts the message as coming from manager D

and updates its authorization file accordingly.

4. An employee is fired without warning. The personnel manager sends a

message to a server system to invalidate the employee’s account. When the

invalidation is accomplished, the server is to post a notice to the employee’s

file as confirmation of the action. The employee is able to intercept the

message and delay it long enough to make a final access to the server to

retrieve sensitive information. The message is then forwarded, the action

taken, and the confirmation posted. The employee’s action may go

unnoticed for some considerable time.

5. A message is sent from a customer to a stockbroker with instructions for

various transactions. Subsequently, the investments lose value and the

customer denies sending the message.

Although this list by no means exhausts the possible types of network security

violations, it illustrates the range of concerns of network security.

1.1 COMPUTER SECURITY CONCEPTS

A Definition of Computer Security

The NIST Computer Security Handbook [NIST95] defines the term computer security

as follows:

COMPUTER SECURITY

The protection afforded to an automated information system in order to attain the

applicable objectives of preserving the integrity, availability, and confidentiality of

information system resources (includes hardware, software, firmware, information/

data, and telecommunications).

10 CHAPTER 1 / OVERVIEW

This definition introduces three key objectives that are at the heart of

computer security:

• Confidentiality: This term covers two related concepts:

Data

1

confidentiality: Assures that private or confidential information is

not made available or disclosed to unauthorized individuals.

Privacy: Assures that individuals control or influence what information

related to them may be collected and stored and by whom and to whom

that information may be disclosed.

• Integrity: This term covers two related concepts:

Data integrity: Assures that information and programs are changed only in

a specified and authorized manner.

System integrity: Assures that a system performs its intended function in an

unimpaired manner, free from deliberate or inadvertent unauthorized

manipulation of the system.

• Availability: Assures that systems work promptly and service is not denied to

authorized users.

These three concepts form what is often referred to as the CIA triad

(Figure 1.1). The three concepts embody the fundamental security objectives for

both data and for information and computing services. For example, the NIST

standard FIPS 199 (Standards for Security Categorization of Federal Information

Confidentiality

Data

and

services

Integrity

Availability

Figure 1.1 The Security Requirements

Triad

1

RFC 2828 defines information as “facts and ideas, which can be represented (encoded) as various

forms of data,” and data as “information in a specific physical representation, usually a sequence

of symbols that have meaning; especially a representation of information that can be processed or

produced by a computer.” Security literature typically does not make much of a distinction, nor does

this book.

1.1 / COMPUTER SECURITY CONCEPTS 11

and Information Systems) lists confidentiality, integrity, and availability as the three

security objectives for information and for information systems. FIPS 199 provides a

useful characterization of these three objectives in terms of requirements and the

definition of a loss of security in each category:

• Confidentiality: Preserving authorized restrictions on information access

and disclosure, including means for protecting personal privacy and propri-

etary information. A loss of confidentiality is the unauthorized disclosure of

information.

• Integrity: Guarding against improper information modification or destruc-

tion, including ensuring information nonrepudiation and authenticity.

A loss of integrity is the unauthorized modification or destruction of

information.

• Availability: Ensuring timely and reliable access to and use of information.

A loss of availability is the disruption of access to or use of information or an

information system.

Although the use of the CIA triad to define security objectives is well established,

some in the security field feel that additional concepts are needed to present a complete

picture. Two of the most commonly mentioned are as follows:

• Authenticity: The property of being genuine and being able to be verified and

trusted; confidence in the validity of a transmission, a message, or message

originator. This means verifying that users are who they say they are and that

each input arriving at the system came from a trusted source.

• Accountability: The security goal that generates the requirement for actions

of an entity to be traced uniquely to that entity. This supports nonrepudia-

tion, deterrence, fault isolation, intrusion detection and prevention, and

after-action recovery and legal action. Because truly secure systems are not

yet an achievable goal, we must be able to trace a security breach to

a responsible party. Systems must keep records of their activities to permit

later forensic analysis to trace security breaches or to aid in transaction

disputes.

Examples

We now provide some examples of applications that illustrate the requirements just

enumerated.

2

For these examples, we use three levels of impact on organizations or

individuals should there be a breach of security (i.e., a loss of confidentiality,

integrity, or availability). These levels are defined in FIPS PUB 199:

• Low: The loss could be expected to have a limited adverse effect on organiza-

tional operations, organizational assets, or individuals. A limited adverse effect

means that, for example, the loss of confidentiality, integrity, or availability

2

These examples are taken from a security policy document published by the Information Technology

Security and Privacy Office at Purdue University.

12 CHAPTER 1 / OVERVIEW

might (i) cause a degradation in mission capability to an extent and duration

that the organization is able to perform its primary functions, but the effec-

tiveness of the functions is noticeably reduced; (ii) result in minor damage to

organizational assets; (iii) result in minor financial loss; or (iv) result in minor

harm to individuals.

• Moderate: The loss could be expected to have a serious adverse effect on

organizational operations, organizational assets, or individuals. A serious

adverse effect means that, for example, the loss might (i) cause a significant

degradation in mission capability to an extent and duration that the organi-

zation is able to perform its primary functions, but the effectiveness of

the functions is significantly reduced; (ii) result in significant damage to

organizational assets; (iii) result in significant financial loss; or (iv) result in

significant harm to individuals that does not involve loss of life or serious,

life-threatening injuries.

• High: The loss could be expected to have a severe or catastrophic adverse

effect on organizational operations, organizational assets, or individuals.

A severe or catastrophic adverse effect means that, for example, the loss

might (i) cause a severe degradation in or loss of mission capability to an

extent and duration that the organization is not able to perform one or

more of its primary functions; (ii) result in major damage to organizational

assets; (iii) result in major financial loss; or (iv) result in severe or cata-

strophic harm to individuals involving loss of life or serious, life-threatening

injuries.

C

ONFIDENTIALITY Student grade information is an asset whose confidentiality

is considered to be highly important by students. In the United States, the release

of such information is regulated by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy

Act (FERPA). Grade information should only be available to students, their

parents, and employees that require the information to do their job. Student

enrollment information may have a moderate confidentiality rating. While still

covered by FERPA, this information is seen by more people on a daily basis, is

less likely to be targeted than grade information, and results in less damage if

disclosed. Directory information, such as lists of students or faculty or

departmental lists, may be assigned a low confidentiality rating or indeed no

rating. This information is typically freely available to the public and published

on a school’s Web site.

INTEGRITY Several aspects of integrity are illustrated by the example of a hospital

patient’s allergy information stored in a database. The doctor should be able to trust

that the information is correct and current. Now suppose that an employee (e.g., a

nurse) who is authorized to view and update this information deliberately falsifies

the data to cause harm to the hospital. The database needs to be restored to a

trusted basis quickly, and it should be possible to trace the error back to the person

responsible. Patient allergy information is an example of an asset with a high

requirement for integrity. Inaccurate information could result in serious harm or

death to a patient and expose the hospital to massive liability.

1.1 / COMPUTER SECURITY CONCEPTS 13

An example of an asset that may be assigned a moderate level of integrity

requirement is a Web site that offers a forum to registered users to discuss some

specific topic. Either a registered user or a hacker could falsify some entries or

deface the Web site. If the forum exists only for the enjoyment of the users, brings in

little or no advertising revenue, and is not used for something important such as

research, then potential damage is not severe. The Web master may experience

some data, financial, and time loss.

An example of a low integrity requirement is an anonymous online poll. Many

Web sites, such as news organizations, offer these polls to their users with very few

safeguards. However, the inaccuracy and unscientific nature of such polls is well

understood.

A

VAILABILITY The more critical a component or service, the higher is the level of

availability required. Consider a system that provides authentication services for

critical systems, applications, and devices. An interruption of service results in the

inability for customers to access computing resources and staff to access

the resources they need to perform critical tasks. The loss of the service

translates into a large financial loss in lost employee productivity and potential

customer loss.

An example of an asset that would typically be rated as having a moderate

availability requirement is a public Web site for a university; the Web site provides

information for current and prospective students and donors. Such a site is not a

critical component of the university’s information system, but its unavailability will

cause some embarrassment.

An online telephone directory lookup application would be classified as a

low availability requirement.Although the temporary loss of the application may be

an annoyance, there are other ways to access the information, such as a hardcopy

directory or the operator.

The Challenges of Computer Security

Computer and network security is both fascinating and complex. Some of the reasons

follow:

1. Security is not as simple as it might first appear to the novice. The require-

ments seem to be straightforward; indeed, most of the major requirements

for security services can be given self-explanatory, one-word labels: confi-

dentiality, authentication, nonrepudiation, or integrity. But the mechanisms

used to meet those requirements can be quite complex, and understanding

them may involve rather subtle reasoning.

2. In developing a particular security mechanism or algorithm, one must always

consider potential attacks on those security features. In many cases, successful

attacks are designed by looking at the problem in a completely different way,

therefore exploiting an unexpected weakness in the mechanism.

3. Because of point 2, the procedures used to provide particular services are often

counterintuitive. Typically, a security mechanism is complex, and it is not obvious

from the statement of a particular requirement that such elaborate measures are

14 CHAPTER 1 / OVERVIEW

needed. It is only when the various aspects of the threat are considered that

elaborate security mechanisms make sense.

4. Having designed various security mechanisms, it is necessary to decide where

to use them. This is true both in terms of physical placement (e.g., at what

points in a network are certain security mechanisms needed) and in a logical

sense [e.g., at what layer or layers of an architecture such as TCP/IP

(Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol) should mechanisms be

placed].

5. Security mechanisms typically involve more than a particular algorithm or

protocol. They also require that participants be in possession of some secret

information (e.g., an encryption key), which raises questions about the