Contracting Barriers

and Factors Affecting

Minority Business Enterprises

A REVIEW OF EXISTING DISPARITY STUDIES

PREPARED FOR

Minority Business Development Agency

Under Contract SB1352-15-SE-0425

PREPARED BY

Premier Quantitative Consulting, Inc.

Orlando, FL

DECEMBER 2016

Foreword

i

December 2016 | Minority Business Development Agency

Foreword

Winning contracts that buy your products, services, proprietary work processes, or intellectual

property is what every entrepreneur strives to accomplish when they go into business.

Contracts are the business barometer that measure the health of your business and determine

whether you grow, stagnate, or fail. For America to build a healthy and inclusive economy,

minority business enterprises (MBEs), must have full and fair access to the range of local, state

and federal contracting opportunities. Disparity studies conducted over the past 10 years at the

state and local levels tell a much different story.

This study, Barriers and Factors Affecting Minority Business Enterprises: A Review of Existing

Disparity Studies, was commissioned by the U.S. Department of Commerce, Minority Business

Development Agency to expose the patterns and trends uncovered in these disparity studies

and to quantify the impact of discrimination in America’s procurement systems. In doing so, it

reveals that MBEs typically obtain a lower number and dollar value of contracts in proportion to

the number of MBEs available. The report also reveals that the industry groups experiencing the

highest ratios of disparity include construction, professional services, architecture, engineering

services, and goods and supplies.

Beyond the civil injustices that have been protested across the country and the

disenfranchisement of minority communities, there are distinct underlying issues that primarily

center on economic disparity. Unemployment, low workforce readiness, lack of transportation

infrastructure, a shortage of affordable housing, and social issues have negatively impacted

minority communities nationwide. While MBEs are contributing to the economic vitality of

these communities by addressing social issues in new ways, they must have the opportunity

to develop capacity and entry points into the industries of tomorrow. Local governments

must change their economic development models that enable MBEs to grow and create jobs,

serve as positive role models to disadvantaged youth, and expose residents to innovation

and emerging industries to generate wealth creation. These business owners seek new

opportunities that will allow them to engage with the entire community in order to make a

broader impact.

Contracting Barriers and Factors Affecting Minority Business Enterprises: A Review of Existing Disparity Studies

ii

Minority Business Development Agency | December 2016

Civic participation is critical to MBEs as their dedication goes beyond economic success. If we

are to improve the government’s ability to advance community conditions capable of deterring

civil injustices and targeting of our law enforcement ofcers, then our federal response must be

guided by interagency collaboration, law enforcement understanding, public investment, and a

sense of urgency.

The ndings of this report raise questions about the current and future state of economic

development in the U.S., in particular as the population moves inexorably to ‘majority-minority’

status. It also points out implications for the Nation’s economic health should MBEs not have

the opportunity to fully participate in government contracting.

During the past 45 years, MBDA has provided MBEs with resources to support and advance

their success in growing the U.S. economy. Today, many MBEs have proven to be major catalysts

for economic growth, job creation, innovation, and entrepreneurship. Due to our unique

position, MBDA has distinct insight regarding current civil unrest issues that plague these

communities, which historically have beneted from the Agency’s funding and resources. This

long-term engagement has helped MBDA to identify promising business opportunities that

create jobs and generate wealth.

Since 2009, MBDA has helped minority-owned rms access more than $34.8 billion in contracts

and capital, which resulted in more than 153,000 jobs created and retained.*

We know that there is more to do. This report is presented for full consideration by corporate

CEOs and boards of directors, governors, state/local legislators, mayors, tribal leaders, law

enforcement/criminal justice and economic development leaders, procurement ofcers,

transportation and infrastructure ofcials, business owners, and pension fund managers and

investors, in the spirit of generating positive momentum toward the goal of shrinking, and

ultimately eliminating, disparities in contracting nationwide.

We encourage you to read the full report which covers the legal framework of disparity studies

and offers a primer for those embarking upon disparity studies at the state and local levels.

It also offers an in depth quantitative analysis of disparity ratios and a qualitative review of

anecdotal evidence. Our hope is that this report will give policy makers and MBE advocates the

information and data they need to make systemic changes.

Alejandra Y. Castillo Albert Shen

National Director National Deputy Director

Minority Business Development Agency Minority Business Development Agency

U.S. Department of Commerce U.S. Department of Commerce

*U.S. Department of Commerce, Minority Business Development Agency performance and CRM systems,

Retrieved December 12, 2016.

Executive Summary

iii

December 2016 | Minority Business Development Agency

Executive Summary

Analysis of public contracting data indicates that substantial disparities exist between minority

and non-minority business enterprises. Specically, the data show that minority business

enterprises (MBEs) typically secure a lower number and dollar amount of contracts in proportion

to the number of available MBEs in a relevant market. As a result, MBEs, agency ofcials,

policy makers, and advocates have a strong incentive to understand the factors that give rise

to observed contracting disparities. In order to advance the dialogue concerning contracting

disparities and inform the development of new and innovative solutions, the Minority Business

Development Agency (MBDA) requested a comprehensive review of existing data and studies

to address several key research questions:

• What factors create barriers and cause disparities in public contracting for MBEs?

• What information do existing studies provide stakeholders in assisting agencies address

observed disparities?

• What areas warrant further investigation and policy research with respect to contracting

disparities experienced by MBEs?

This research explored existing disparity studies conducted by a variety of economic consultants

that were commissioned by local and state governments nationwide. A disparity study is a

comprehensive effort that analyzes a wealth of data pertaining to the legal, legislative, and

contracting environment facing MBEs in a particular jurisdiction or when procuring contracts

from a specic federal, state or municipal agency. The ndings presented in this report are

drawn from a comprehensive review of 100 disparity studies, summaries, and reports that are

publicly-available and accessible via the internet. The selected set of disparity studies does

not represent the full universe of studies and includes a greater focus on recent studies with

information on contracting disparities affecting MBEs within the last ten years.

LEGAL PRECEDENT AND DISPARITY STUDY BASICS

The evolution and development of disparity studies arose from legal challenges to existing

afrmative action or race-conscious programs

1

enacted by government rules, legislation or

policies intended to alleviate perceived or actual discrimination against different racial, ethnic or

1

This report uses the terms “afrmative action programs,” “race-based programs,” and “race-conscious programs”

interchangeably, where the terms imply a government initiated program that specically includes racial or ethnic preferences in

alleviating discriminatory behavior.

Contracting Barriers and Factors Affecting Minority Business Enterprises: A Review of Existing Disparity Studies

iv

Minority Business Development Agency | December 2016

gender groups in public contracting. In response to the legal precedent,

2

government agencies

have commissioned disparity studies to examine the extent to which minority contractors are

underutilized in public procurement in a particular industry and geography, such that the agency

can determine whether a legally-defensible race-conscious program is justied or needed to

provide remedial relief given discriminatory or exclusionary behavior.

Disparity studies typically include an overview of the legal precedent that inuences the

key methodologies, computations, and evidence necessary to justify or support existing or

proposed contracting programs, including those that are race-conscious. City of Richmond v.

J.A. Croson Co.

3

(Croson) and Adarand Constructors Inc. v. Peña

4

(Adarand) are two seminal

legal decisions that established the evidentiary tests necessary to evaluate local, state, and

federal race-conscious contracting programs. These cases introduced several key concepts and

standards, including:

• Ensuring that disparities in contracting are specic to the relevant geographic and

product markets;

• Disparities are evaluated considering only rms that are ready, willing and able to bid on

and perform contracts;

• The importance of evidence related to marketplace discrimination to support race-

conscious contracting programs; and

• The importance of anecdotal evidence in supporting programs offering remedial relief

of discrimination in public contracting.

There have been a number of additional challenges to existing race-conscious contracting

programs. While the constitutionality of programs has been upheld, the legal decisions have

often brought forth key issues related to disparity study methodologies and the evidence

needed to support an inference of discrimination related to an observed disparity ratio.

In addition to the legal review, disparity studies typically include an overview of the rules,

regulations, and ordinances that govern public contracting for a particular agency. This

includes the existence of race-conscious programs to alleviate contracting disparities. In order

to determine the extent to which disparities exist among MBEs and different racial and ethnic

groups, disparity studies compute numerical disparity ratios using agency procurement data,

information on winning bidders, and a comprehensive analysis of actual and potential bidders

to determine which rms are ready, willing, and able to bid on contracts. Consultants use

this information to determine utilization and availability, the two inputs of the disparity ratio

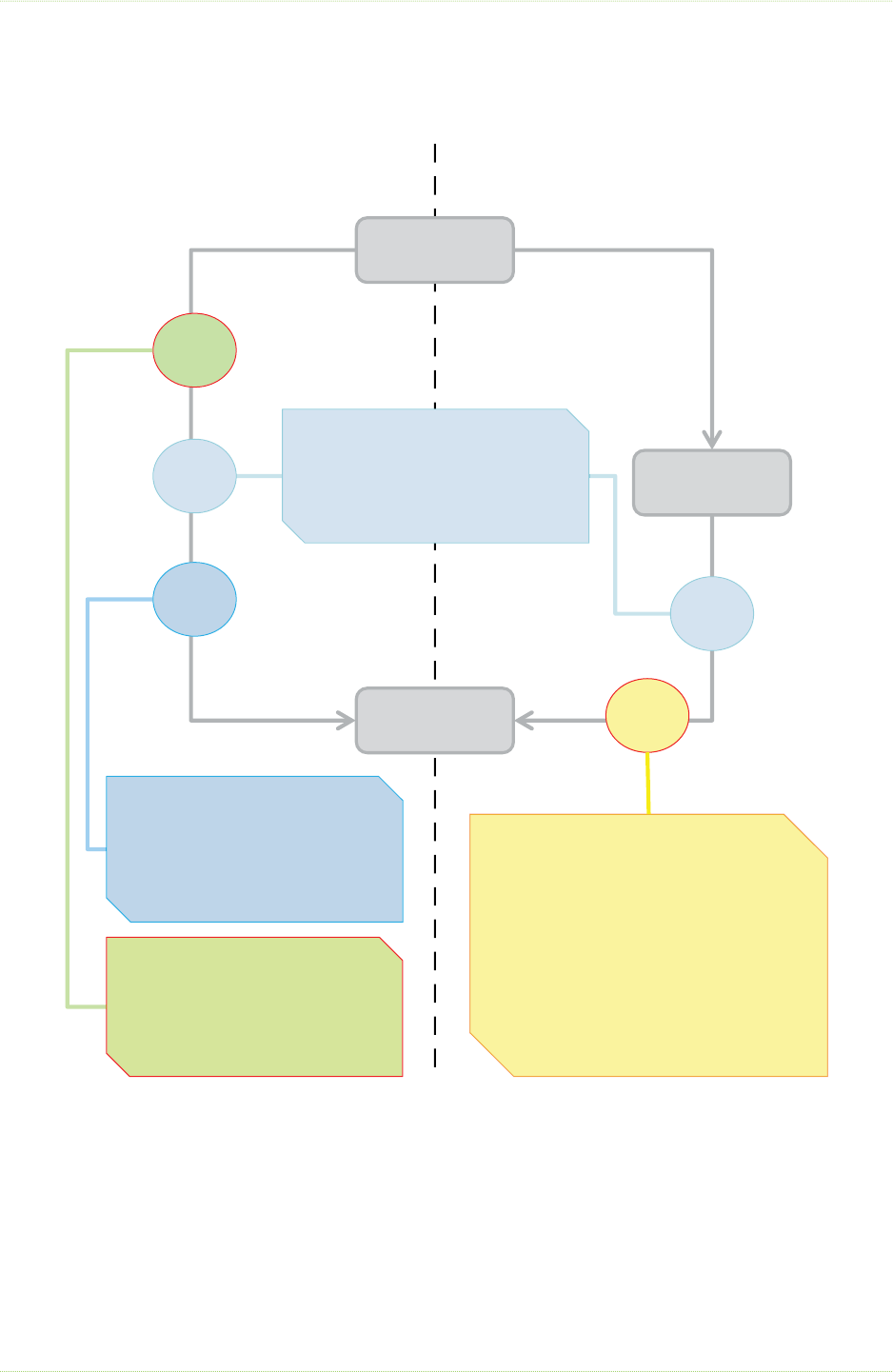

calculation. Figure ES-1 shows a simplied illustration of the disparity ratio calculation, where

2

City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co. (488 US 469 (1989)) and Adarand Constructors Inc. v. Peña (515 US 200 (1995)) are two

seminal legal decisions that established the evidentiary tests necessary to evaluate local, state, and federal race-conscious

contracting programs.

3

488 US 469 (1989).

4

515 US 200 (1995).

Executive Summary

v

December 2016 | Minority Business Development Agency

the numerator represents the utilization of MBEs and the denominator shows the availability

of MBEs.

5

FIGURE ES-1

DISPARITY RATIO COMPUTATION EXAMPLE

As a general rule of thumb, a disparity ratio of less than 0.80 (or 80 if expressed on a scale that

multiplies the disparity index by 100) indicates a substantial disparity.

6

Utilization and availability

are also specic to well dened geographic and product markets (i.e., the “relevant markets”).

Market denition is an economic concept that looks to substitutability and is intended to

determine who is competing for public contracts along geographic and product lines. Robust

and defensible disparity studies have an explicit denition of both geographic and product

markets, as these are required in order to determine who is competing for contracts and the

extent to which disparities exist among these market denitions.

DISPARITIES EXIST

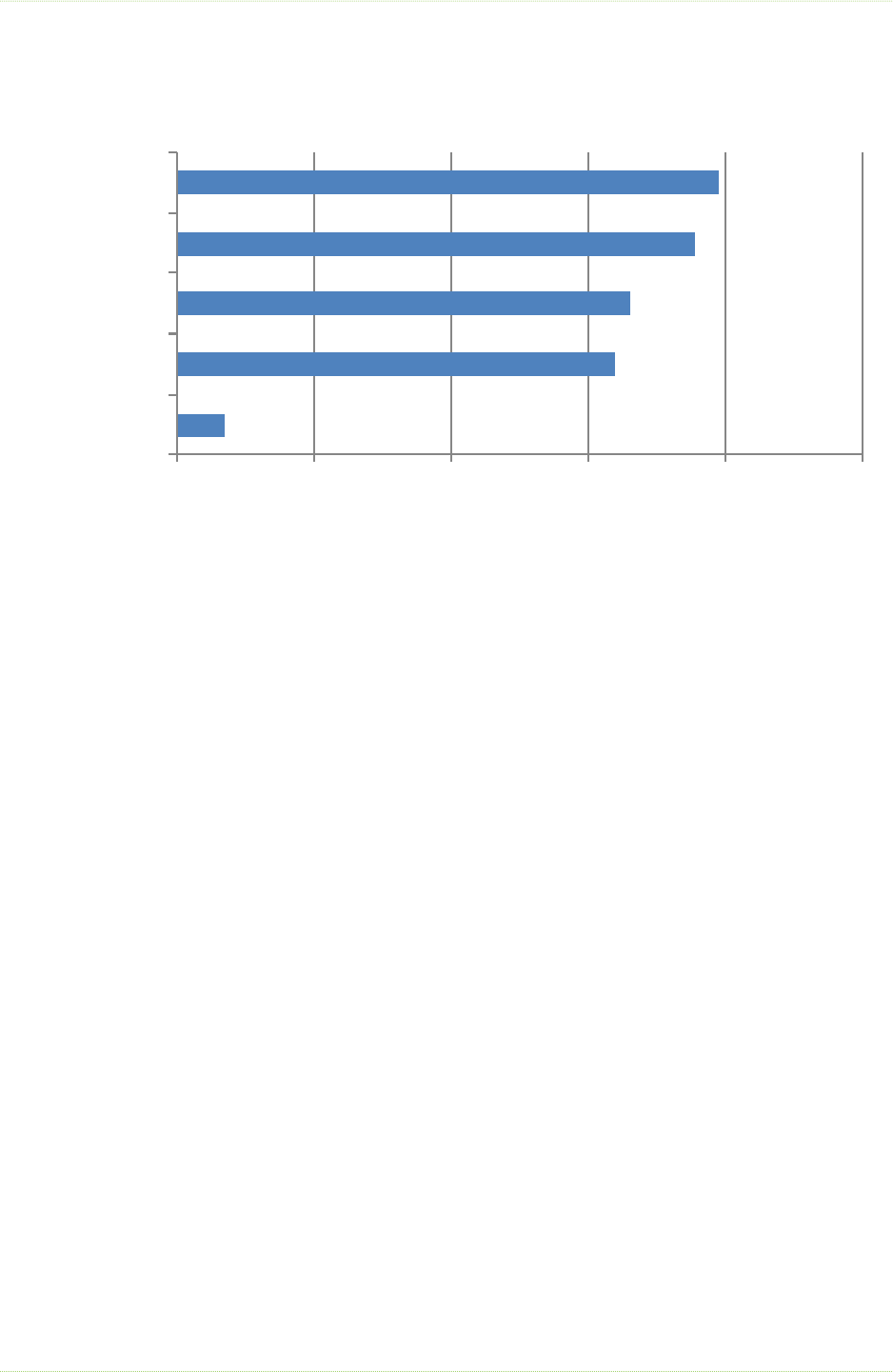

The review of selected disparity studies provided 2,385 distinct high-level disparity ratios

presented in executive summaries, major ndings, and conclusions sections. These ratios

include observations for MBEs in the aggregate, as well as for the African American, Hispanic

5

This simplied example assumes uniform contract and rm sizes, such that the disparity ratio would be equivalent whether one

considers utilization based on the number of contracts or dollars awarded per contract.

6

Given the lack of standardization in evaluating the levels of underutilization, many studies employ the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission’s (EEOC) “80 percent rule” in Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures. In the context of

employment discrimination, an employment disparity ratio below 80 indicates a “substantial disparity” in employment.

Award = $100

Award = $300

MBE Utilization =

25%

UTILIZATION CALCULATION

MBE Availability

AVAILABILITY CALCULATION

MBEs

Non-MBEs

MBEs

Non-MBEs

Contracting Barriers and Factors Affecting Minority Business Enterprises: A Review of Existing Disparity Studies

vi

Minority Business Development Agency | December 2016

American and Asian American categories.

7

In addition, studies computed disparity ratios

based on industry, with the majority reporting disparity ratios for major industry groups such

as construction, professional services, architecture and engineering services, and goods and

supplies. However, there is no standard disparity ratio reporting method and a review of the

disparity studies found wide variation in how disparity authors computed and reported disparity

ratios. Some studies included a single disparity ratio covering multiple years, while others

reported ratios for every calendar year or scal year for the time period under investigation.

Furthermore, some studies only reported disparity ratios on prime contracts, while other studies

distinguished between prime contracts and subcontracts.

As a result, the disparity ratios are not an “apples to apples” comparison when examining

results from one report compared to another. The studies were conducted by different authors,

for different agencies, using different product and geographic market denitions and for

different time periods. In addition, there are methodological differences in computing disparity

ratios among consultants. Nevertheless, the comprehensive nature of the review established a

distinct pattern of substantial contracting disparities for MBEs in the aggregate and for different

racial and ethnic groups across different industries. 78.2 percent of all disparity ratios drawn

from the set of disparity studies were less than 0.8, with a median value of 0.19. Considering

that less than 0.8 is a substantial disparity, these results indicate that contracting disparities for

MBEs are pervasive.

Furthermore, many studies tested whether these disparity ratios were statistically signicant,

where disparity study authors used statistical approaches to test whether the disparity could

have arisen due to chance, or some other factor such as discrimination. For those disparity

studies that explicitly indicated whether a disparity ratio was statistically signicant or not,

approximately 65 percent of all disparity ratio observations were classied as statistically

signicant by the study authors. However, this may be a conservative estimate since some

disparity study consultants only reported signicance at a highly aggregated level. Lastly,

99 percent of statistically signicant disparities identied by study authors were less than 0.8,

lending strong support for discriminatory behavior in contracting.

Despite the detail regarding underrepresentation presented in disparity calculations, the

existence of a disparity does not on its own support a conclusion of discrimination. Rather, the

numerical disparity ratios necessitate additional inquiries to explain why MBEs face signicant

7

This does not represent the totality of disparity ratios reported in the 100 studies. In certain cases, disparity study consultants

also included Native Americans and Subcontinent Asian Americans, but these instances were relatively few or often contained

inadequate data to compute a disparity ratio. In addition, most studies reported disparity ratios for women-owned businesses,

although differences existed with respect to approaches separating out Caucasian-owned WBEs versus non-Caucasian owned

WBEs. Furthermore, some studies reported an aggregate M/WBE disparity ratio, as opposed to just an MBE disparity ratio.

The results presented in this report include the combined M/WBE ratios, but do not include WBE-only disparity ratios. Lastly,

many studies provided hundreds of different additional disparity ratios based on smaller geographic regions, combining across

industries, looking at different funding sources, or looking at different time periods. In order to minimize double counting, the

research ndings in this study do not include the subset of disparity ratios based on the multiple iterations that some disparity

study consultants performed. The primary purpose of the disparity ratio review was to demonstrate that these studies identied

contracting disparities, sufcient to assess causal factors.

Executive Summary

vii

December 2016 | Minority Business Development Agency

contracting disparities compared to non-MBEs. In order to determine whether disparities are

the result of discrimination, disparity study consultants use both quantitative and qualitative

analyses to examine the root causes of disparities in public contracting. Most studies in the

research set included an analysis of marketplace discrimination, using regression analysis to

investigate disparities in business formation, business earnings, and loan denials between MBEs

and non-MBEs in the private sector. These analyses demonstrate the presence of discriminatory

behavior in private markets by showing race as a statistically signicant predictor of disparities in

business owner earnings, business formation and access to capital. As a result, these analyses

allow disparity studies to address whether or not public agencies were susceptible to or

engaging in passive discrimination in public contracting.

USING ANECDOTAL EVIDENCE TO EXPLORE CONTRACTING BARRIERS

AND CAUSES

Anecdotal evidence does not establish the predicate for race-conscious programs, but instead,

aids policymakers in evaluating whether a contracting program is needed and narrowly tailored

to address demonstrated discriminatory behavior. Anecdotal evidence provides rst-hand

accounts of barriers in public contracting and instances where discrimination is a factor in MBE

underrepresentation. Critics of the validity of anecdotal evidence argue that the accounts may

not be sufciently veried and that instead of detailing actual accounts of discrimination, the

evidence may only present perceptions of discrimination. Yet, legal proceedings have varied on

the level of verication needed to support the importance and relevance of anecdotal evidence.

In order to address these concerns, the most robust disparity studies will draw on multiple

techniques to obtain anecdotal accounts from individuals that have had actual, veriable

experiences in working with a procurement agency. It is through a wide number of reliable

sources that disparity studies can include instances of discrimination which are representative of

the experiences of multiple minority business owners.

The disparity studies reviewed for this study provided specic, veriable instances of

discrimination which were recorded, cataloged, and analyzed using content analysis. The most

robust studies identied barriers, discussed the harm that the improper conduct inicted on

the businesses in question, and examined the extent to which discriminatory exclusion and

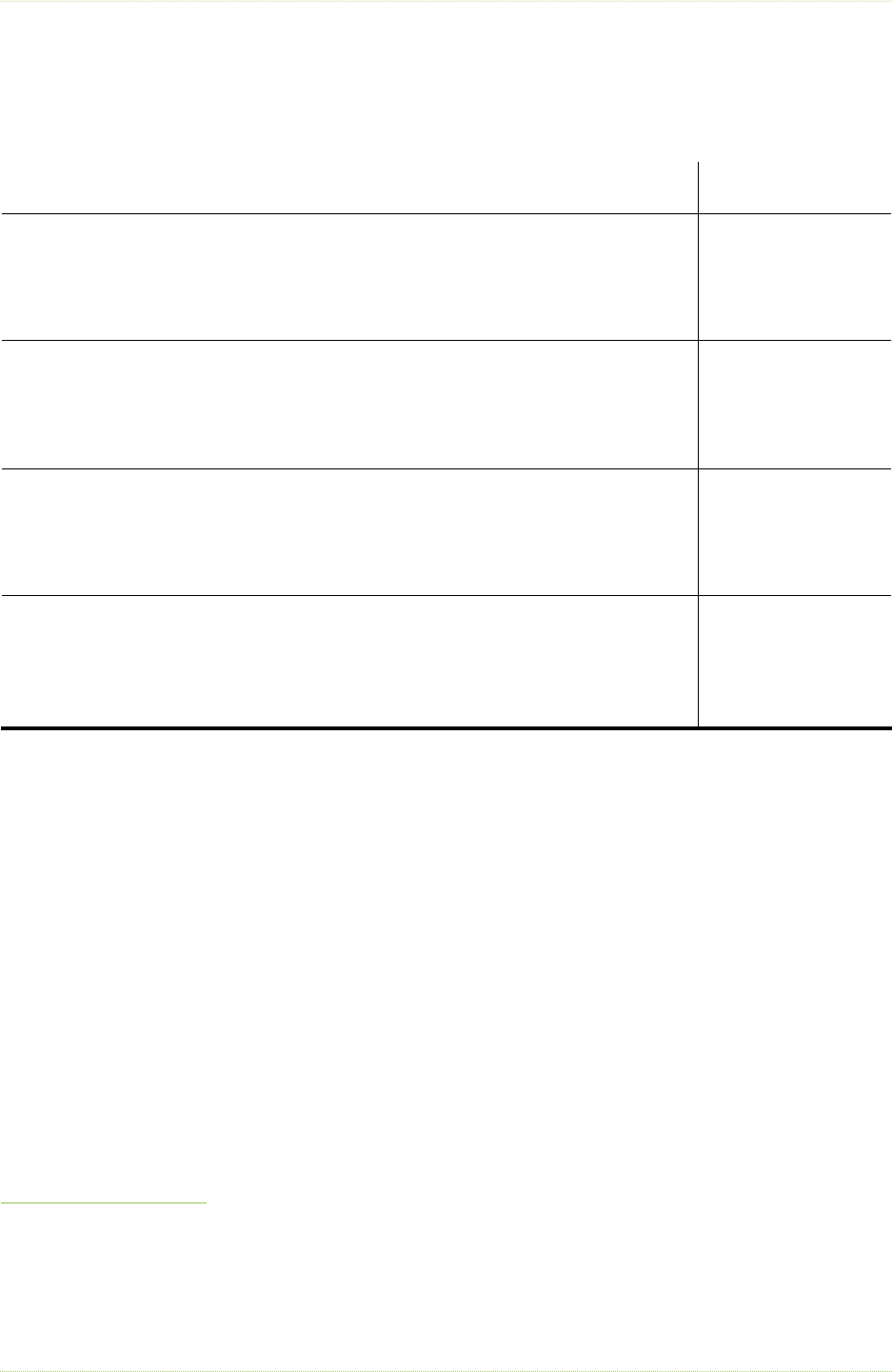

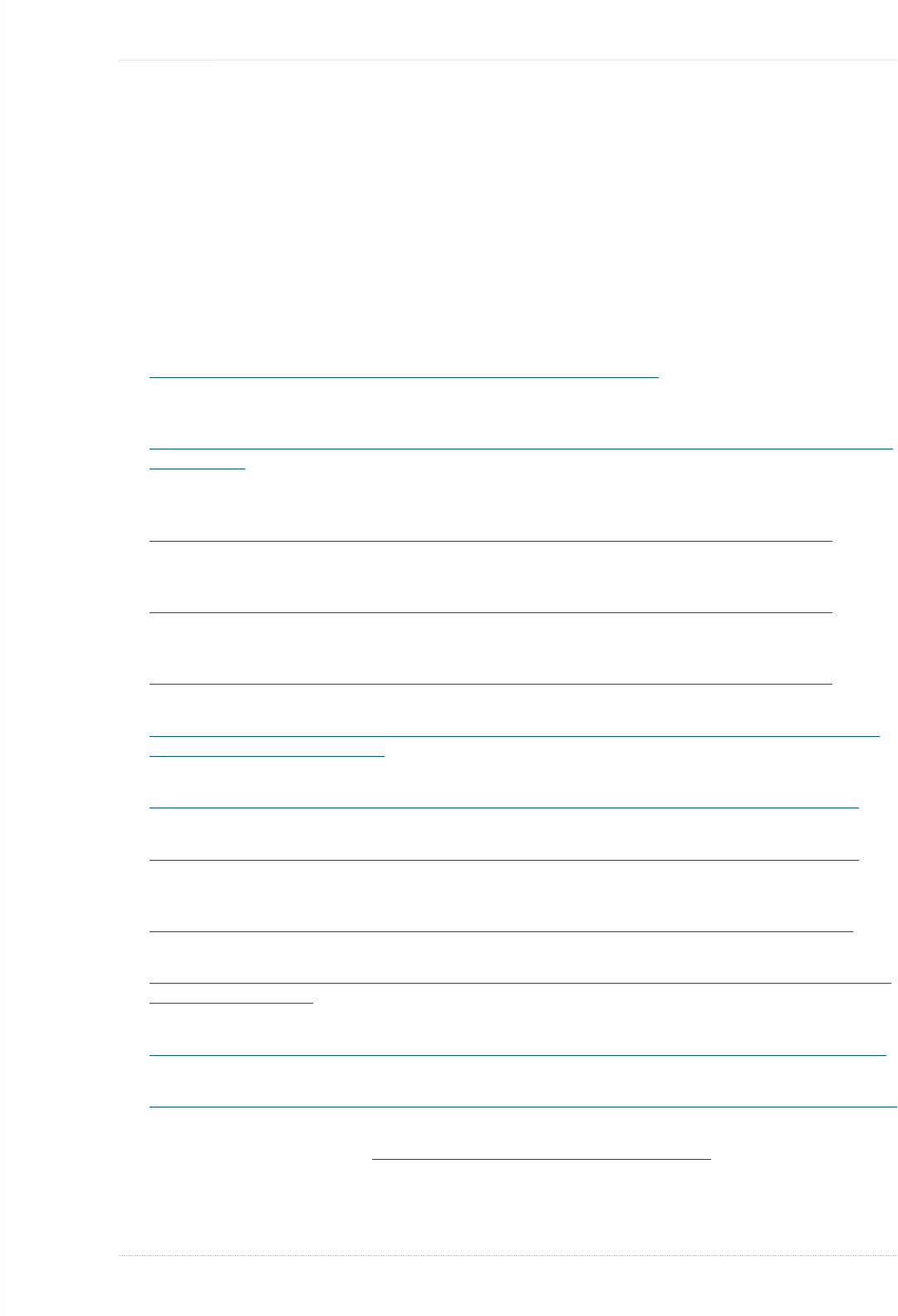

impaired contracting opportunities are systemic rather than isolated or sporadic. Figure ES-2

summarizes the most frequently cited barriers in the disparity studies.

Contracting Barriers and Factors Affecting Minority Business Enterprises: A Review of Existing Disparity Studies

viii

Minority Business Development Agency | December 2016

FIGURE ES-2

MOST FREQUENTLY CITED CONTRACTING BARRIERS FACING MBES

Discrimination inuenced multiple contracting barriers, both from the marketplace, as well as

driven by either a contracting agency or non-MBE prime in the context of subcontracting. The

barriers identied varied from outright prejudicial treatment and instances of exclusion based

on racism, to marketplace barriers erected by systemic discrimination in both the private and

public market (e.g., access to capital). Disparity studies with substantial anecdotal evidence

supporting the presence of discriminatory barriers provide justication for the use of race-

conscious programs in those jurisdictions. In addition, there are multiple non-discriminatory

barriers, such as large project sizes, timely payment, and bid requirements that present

challenges to potential bidders regardless of the race or ethnicity of the owners. However, the

anecdotal evidence indicates that certain systemic discriminatory barriers can inuence the

perception of exclusionary practices with respect to some non-discriminatory barriers.

Arguably the most difcult barrier to address with respect to discrimination is the exclusionary

networks that MBEs encountered in public contracting. On one hand, network exclusion can

arise due to normal business operating procedures, often dictated by the desire to work with

companies that have prior experience, demonstrated work product, and a solid reputation. Yet,

in other instances, discriminatory attitudes of agency personnel and non-MBE primes facilitated

excluding MBEs from informal networks that inuence learning about and obtaining public

contracting opportunities.

Agency

Non-MBE

Prime

MBE

MBE as

Prime

MBE as

Subcontractor

Prime Level

Discriminatory

Barriers

•

Timely bid

notification

•

Explicit

discrimination

(stereotypes,

higher and double

standards)

•

MBE/DBE stigma

Subcontractor Level

Discriminatory

Barriers

•

Timely bid notification

•

Bid shopping

•

Held bid

•

Lack of good faith

effort

•

Only using an MBE if

required

•

Explicit discrimination

(stereotypes, higher

and double

standards)

•

MBE/DBE stigma

Prime Level

Non-Discriminatory

Barriers

•

Large project sizes

•

Bonding/insurance

•

Bid requirements

•

Timely payment

Pervasive Barriers**

•

Access to capital

•

Network access

•

Marketplace

discrimination

**Access

to Capital and Network Access barriers can arise due to both discriminatory and non-discriminatory reasons and also

influence

non-discriminatory barriers such as bonding and insurance

Executive Summary

ix

December 2016 | Minority Business Development Agency

The review of existing disparity studies yielded several common themes and insights beyond

the characterization of contracting barriers and evidence of discrimination. These included:

• The “needle has not moved” with respect to overcoming disparities. Every study

identied signicant contracting disparities and many supported these ndings with

additional quantitative and anecdotal evidence that supported the need for both race-

neutral and race-conscious remedial efforts. Yet, over time disparities were prevalent

even within the same jurisdiction.

• Disparity studies often reported the same race-neutral remedies (e.g., unbundling large

contracts, improving payment processes, improving data collection) and race-conscious

remedies (e.g., improved goal setting and monitoring) to address contracting disparities,

yet what is missing is the extent to which agencies have actually implemented and

measured the success or failure of these recommendations.

• Race-conscious programs typically helped MBEs when enacted; however the legal

history has illustrated that these programs need to comply with the strict scrutiny

standard and be narrowly tailored.

In addition to common observations, the disparity studies and anecdotal evidence highlighted

common problems and issues with contracting disparities experienced by MBEs. These include:

• Enforcement and accountability of race-conscious programs by contracting agencies.

There is a perception that prime contractors do not engage in good faith efforts to

comply with race-conscious programs and agencies do not monitor or enforce these

efforts.

8

• Resource constraints are a major issue facing contracting agencies. Many suggestions

for program improvements, both race-neutral and race-conscious, require a substantial

monetary investment (both human capital and infrastructure) at the public agency level.

Based on the political and economic environment, some of these recommendations are

prohibitive given lack of resources.

• There is often insufcient analysis and evidence of subcontracting activity at the agency

level. Given that subcontracting is an important and critical component of increasing

MBE participation in public contracting, greater oversight and accountability of

subcontracting behavior coupled with better and more reliable data collection should

be a priority

The disparity study review indicated that both discriminatory and non-discriminatory actions

lead to contracting disparities for MBEs. Additional research is needed to understand what

steps public agencies have taken to address these disparities. Specically, whether agencies

have been effective at implementing the common policy prescriptions most disparity studies

include and to what extent these policies have either succeeded or failed. Beyond this, there

are a number of areas to explore and research with respect to lessening barriers faced by

8

Numerous disparity studies included anecdotal accounts which touted the belief that without a race-conscious program in place,

prime contractors would never use an MBE.

Contracting Barriers and Factors Affecting Minority Business Enterprises: A Review of Existing Disparity Studies

x

Minority Business Development Agency | December 2016

MBEs in public contracting. MBEs, advocacy groups and policy makers should explore new

and innovative ways to increase engagement, oversight, enforceability and accountability

within the public contracting process. This requires leveraging data sharing and transparency,

exploring race-neutral means and the efcacy of these means, and also evaluating what race-

conscious methods have been not only defensible, but successful, in alleviating the effects of

discrimination.

Table of Contents

xi

December 2016 | Minority Business Development Agency

Table of Contents

Foreword ................................................................................................................................................ i

Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ iii

Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................ xi

List of Figures ..................................................................................................................................... xii

List of Tables ...................................................................................................................................... xiii

Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................... xv

1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................1

2. Legal Review .................................................................................................................................5

Seminal Cases – Croson and Adarand ..............................................................................6

Concrete Works of Colorado .............................................................................................8

Western States Paving ........................................................................................................8

Rothe and DynaLantic ........................................................................................................9

3. Disparity Study Basics ...............................................................................................................11

General Overview of Disparity Studies ........................................................................... 12

Critical and Often Contentious Issues ............................................................................21

Importance of Anecdotal Information ............................................................................28

4. Disparities and Marketplace Discrimination Exist ................................................................31

Description of the Set of Disparity Studies ....................................................................31

Observed Disparities in Minority Contracting ...............................................................34

Subcontracting Analysis ................................................................................................... 38

Quantitative Data on Marketplace Discrimination ........................................................40

5. Anecdotal Analysis and Summary ...........................................................................................47

Importance of Anecdotal Evidence in Supporting Race-Based Programs ..................47

Disparity Study Review Findings on Collection Methods .............................................48

Characterizing Barriers Identied in Existing Disparity Studies ....................................52

Networking Barriers ..........................................................................................................55

Process-Based Barriers ..................................................................................................... 57

Discriminatory Attitudes and Perceptions ...................................................................... 63

Barriers Affecting Firm Financial Performance and Ability to Compete ......................67

6. Reserach Findings ......................................................................................................................69

There is a Need for Innovative Policies ...........................................................................71

Appendix A – List of Disparity Studies (Chronological) .............................................................. 75

Appendix B – Glossary ......................................................................................................................83

Contracting Barriers and Factors Affecting Minority Business Enterprises: A Review of Existing Disparity Studies

xii

Minority Business Development Agency | December 2016

List of Figures

Figure ES-1. Disparity Ratio Computation Example .......................................................................... v

Figure ES-2. Most Frequently Cited Contracting Barriers Facing MBEs ...................................... viii

Figure 2-1. Timeline of Key Legal Cases by Decision Date ..............................................................6

Figure 2-2. Key Holdings in Croson and Adarand .............................................................................7

Figure 2-3. Key Holdings in the Rothe and DynaLantic Cases .......................................................10

Figure 3-1. Legal Review and Requirements for Disparity Studies ................................................12

Figure 3-2. Key Components of Procurement Data Analysis .........................................................13

Figure 3-3. Utilization Example using Contract Awards ..................................................................15

Figure 3-4. Methodologies for Calculating Availability and Disparity Indices .............................. 16

Figure 3-5. Disparity Computation Example .................................................................................... 17

Figure 3-6. Discrimination Assessment Analysis Summary .............................................................19

Figure 3-7. Evaluation and Recommendation Foci ..........................................................................21

Figure 3-8. Capacity Sensitivity Example ..........................................................................................24

Figure 4-1. Disparity Ratio Distribution for Minority-Owned Businesses.......................................35

Figure 4-2. Disparity Ratio Observations by Industry and Minority Category ...............................36

Figure 4-3. Regression Analysis Process and Results Example .......................................................43

Figure 5-1. Distribution of Anecdotal Data Collection Mechanisms ..............................................49

Figure 5-2. Barriers Faced by MBEs in Public Contracting .............................................................53

Figure 5-3. Frequency of Barriers Identied by M/WBEs ................................................................55

Figure 5-4. Example of Bid Shopping ...............................................................................................62

List of Figures/List of Tables

xiii

December 2016 | Minority Business Development Agency

List of Tables

Table 4-1 Disparity Ratio Observations by Minority Category and Industry ................................. 37

Table 4-2 Median Disparity Ratios by Minority Category and Industry ......................................... 38

Table 4-3 Subcontracting Subset Analysis ........................................................................................ 40

Table 5-1 Summary of Anecdotal Evidence Collection Methods ................................................... 50

Acknowledgements

xv

December 2016 | Minority Business Development Agency

Acknowledgements

This research report would not have been possible without the support, guidance and direction

provided by Minority Business Development Agency (MBDA) personnel and stakeholders. As

the scope and direction of the research project shifted to focus on key issues facing minority

business enterprises in public contracting, the MBDA team was helpful in identifying the key

issues it sought to explore and understand as a result of this research effort. The research team

wishes to acknowledge the insight, guidance and direction provided by Bridget Gonzales,

Antavia Grimsley, Josephine Arnold, Efrain Gonzalez, Jr., Albert Shen, and Justin Tanner. In

addition, the research team is grateful to David Beede and Dr. Rob Rubinovitz, from the Ofce

of the Chief Economist at the United States Department of Commerce, for their contributions.

Lastly, the research team would like to thank our peer reviewers, who provided valuable

commentary that helped focus our research ndings as we strived to assist MBDA, stakeholders,

and elected ofcials address key issues in public contracting.

Chapter 1: Introduction

1

December 2016 | Minority Business Development Agency

CHAPTER 1:

Introduction

Analysis of public contracting data indicates that disparities exist in contracting activity between

minority and non-minority business enterprises. Specically, the data show that minority

business enterprises (MBEs) typically secure a lower number and dollar amount of contracts in

proportion to the number of MBEs that are available in the marketplace to bid on and perform

contract work. In response, the Federal Government, state agencies, and local municipalities

have enacted a number of afrmative action, or race-conscious,

9

programs designed to

overcome both the perception and reality of discrimination against MBEs. The proliferation of

these programs led to an increase in the number of legal challenges to them. As a result, the

various legal challenges and court decisions provide a foundation for “disparity studies” that

assess and provide the basis for race-conscious programs.

Government agencies at the federal, state, and local level typically commission disparity

studies to examine the extent to which minority and women contractors are underutilized in

public procurement. Well-conducted disparity studies not only present information on actual

contracting disparities experienced by MBEs in a particular industry and geographic region,

but also facilitate an investigation into the extent to which discrimination is a prevalent issue

in the marketplace. In fact, the need for disparity studies often arises out of legal challenges

to existing programs, and the results of such studies can have broad application to a number

of other agency programs. Thus even if an agency is not experiencing litigation, it will be well

informed to ensure its existing or potential program complies with legal precedent.

Given evidence of disparities in existing studies, MBEs, agency ofcials, policy makers,

and advocates have a strong incentive to understand the factors that give rise to observed

contracting disparities. In order to advance the dialogue concerning contracting disparities and

inform the development of new and innovative solutions, the Minority Business Development

Agency (MBDA) requested a comprehensive review of existing data and studies to address

several key research questions:

• What factors create barriers and cause disparities in public contracting for MBEs?

• What information do existing studies provide stakeholders in assisting agencies address

observed disparities?

9

This report uses the terms “afrmative action programs,” “race-based programs,” and “race-conscious programs”

interchangeably, where the terms imply a government initiated program that specically includes racial or ethnic preferences in

alleviating discriminatory behavior against affected racial or ethnic minority business enterprises in public contracting.

Contracting Barriers and Factors Affecting Minority Business Enterprises: A Review of Existing Disparity Studies

2

Minority Business Development Agency | December 2016

• What areas warrant further investigation and policy research with respect to contracting

disparities experienced by MBEs?

To address these questions, a comprehensive review of publicly-available disparity studies,

summaries, and reports was conducted. The review of existing disparity studies includes a high-

level inventory of observed disparity ratios coupled with a qualitative review of the anecdotal

evidence presented in each disparity study that provides insight into causal factors for observed

numerical disparities.

Anecdotal evidence offers human experience and context for quantitative evidence such

as disparity calculations and regression analyses. Anecdotal evidence has also proven to

be one of the most important elements in evaluating potential discriminatory behavior and

barriers to minority-owned rms in public contracting. As a result, many disparity studies use

qualitative data to help address the fundamental questions of “why do disparities exist in public

contracting?” and perhaps more importantly, “why do disparities continue to exist in public

contracting despite the presence of many race-based contracting programs?” The collection

and analysis of this qualitative data provides a basis for challenging the status quo of pervasive

contracting disparities by helping advance the discussion with a focus on their key drivers.

This report begins with an overview of several legal challenges to race-conscious remedial

contracting programs. The legal precedent and case law informs the analyses contained in

disparity studies, such that accumulated evidence is either sufcient to justify remedial race-

based action, or alternatively, evaluate other means to address any identied contracting

disparities. Chapter 3 details the basics of disparity studies, guided in part by the legal

challenges and ndings discussed in Chapter 2. While not every disparity study adheres to

the same format or level of detail, each study generally covers a number of critical elements,

including analysis of applicable laws, regulations and ordinances, a description of contracting

data and sources, utilization and availability analyses, computing disparity ratios, exploring

third-party data sources on discrimination, collection and reporting of anecdotal evidence, and

when appropriate, evaluation of existing race-based contracting programs.

Chapter 4 presents a summary of disparity ratios drawn from the selected set of disparity

studies, summaries, and reports, which indicate widespread disparities in public contracting for

the jurisdictions and time periods covered by each study. Identication of potential disparity

studies entailed a thorough and comprehensive search of publicly-available studies posted

on agency, consultant, or other websites. A special focus was on disparity studies published

in the last ten years, to provide more recent insight into the public contracting landscape for

MBEs. As such, it is important to recognize that the selected set of disparity studies, summaries

and reports do not represent the universe of all disparity studies and are not intended to serve

as a nationally representative, statistically signicant sample of all disparity studies conducted.

Rather, the set of disparity studies, summaries and reports represent studies that are publicly-

available and accessible via the internet and this report did not exclude any identied studies,

Chapter 1: Introduction

3

December 2016 | Minority Business Development Agency

summaries or reports. Chapter 4 also summarizes general ndings from quantitative analyses

disparity study authors conducted with respect to analyzing marketplace discrimination.

Chapter 5 details the use of anecdotal evidence in disparity studies to help provide insight into

the different barriers MBEs face in public contracting. The chapter includes an overview of the

major barriers identied by disparity studies, with a particular focus on whether these barriers

are largely the result of discrimination or other factors. Chapter 6 provides conclusions and

recommendations for future research and discussion. The conclusion also includes potential

action items for addressing contracting disparities experienced by MBEs in public contracting.

Lastly, Appendix A includes a list of the publicly-available disparity studies, summaries and

reports identied and reviewed as part of this research project, while Appendix B contains a

glossary of terms that are commonly used in disparity studies.

Chapter 2: Legal Review

5

December 2016 | Minority Business Development Agency

CHAPTER 2:

Legal Review

Legal challenges to race-conscious contracting programs provide insight and guidance on

evaluating the evidence needed to identify and characterize discriminatory behavior in public

contracting. This chapter reviews the general legal framework of disparity studies, focusing on a

review of several key legal challenges to federal, state, or local contracting programs regarding

minority-owned businesses. The purpose of this chapter is not to advocate, condone or

recommend any legal conclusions drawn from the case law. Rather, the intent of this chapter is

to provide information on how legal precedent inuences the analysis of contracting disparities

affecting minority business enterprises at the federal, state, or local level.

10

This includes

investigating how legal precedent and court proceedings:

• Determine the evidentiary tests for assessing existing race-based contracting programs

for disadvantaged, minority, women, or small business enterprises;

• Dene parameters for evaluating potential disparities in contracting;

• Stress the importance of anecdotal evidence to investigate causes of disparities.

Figure 2-1 is a timeline of several key legal decisions that provide insight into these issues.

Although a full legal history includes numerous additional cases, these ten decisions capture

elements of legal challenges and disparity analyses that have broad applicability to assessing

potential discrimination and use of race-conscious programs in public contracting across

multiple industries and jurisdictions.

10

Most disparity studies include a comprehensive legal overview as part of the report, often with a longer and more in-depth

discussion attached as an Appendix to the main report. For a general legal review, see Connecticut Disparity Study: Phase 1, The

Connecticut Academy of Science and Engineering, August 2013. For a substantially more in-depth and contemporaneous review of

legal precedent see 2015-16 State of Indiana Disparity Study, BBC Research & Consulting, March 2016.

Contracting Barriers and Factors Affecting Minority Business Enterprises: A Review of Existing Disparity Studies

6

Minority Business Development Agency | December 2016

FIGURE 2-1

TIMELINE OF KEY LEGAL CASES BY DECISION DATE

SEMINAL CASES – CROSON AND ADARAND

City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co.

11

(Croson) and Adarand Constructors Inc. v. Peña

12

(Adarand) are two seminal legal decisions that established the evidentiary tests necessary to

evaluate local, state, and federal race-conscious contracting programs. Figure 2-2 presents an

overview of key legal holdings in each case. Included in this summary is Adarand VII,

13

which

was the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals decision following remand of the case.

11

488 US 469 (1989).

12

515 US 200 (1995).

13

Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Slater, 228 F.3d 1147 (10th Cir. 2000)

1990

1995 2000

2005

2010 2015

City of Richmond v. J.A.

Croson Co., 488 U.S. 469

(1989)

Adarand Constructors, Inc. v.

Pena, 515 U.S. 200 (1995)

Adarand Constructors, Inc. v.

Slater, 228 F.3d 1147 (10

th

Cir.

2000)

Dynalantic Corp. v. U.S.

Department of Defense, 885 F.

Supp. 2d 237 (D.D.C. 2012)

RotheDevelopment Corp. v. U.S.

Department of Defense, 545 F. 3d 1023

(Fed. Cir. 2008)

RotheDevelopment, Inc. v. U.S.

Department of Defense, Appeal

Ongoing (2016)

Concrete Works of Colorado,

Inc. v. City & County of Denver,

36 F.3d 1513 (10

th

Cir. 1994)

Concrete Works of Colorado, Inc. v. City

and County of Denver, 321 F. 3d 950 (10

th

Cir. 2003)

Memorandum Opinion, United States

District Court for the District of

Columbia, June 5, 2015, Rothe

Development, Inc. v. Department of

Defense, No. 12-CV-744 (filed D.D.C.

May 9, 2012)

Western States Paving Co. v.

Washington State DOT, 407 F.3d

983 (9th Cir. 2005)

Chapter 2: Legal Review

7

December 2016 | Minority Business Development Agency

FIGURE 2-2

KEY HOLDINGS IN CROSON AND ADARAND

Croson continues to impact considerations of race-conscious contracting programs. First,

Croson established that a local government could not rely on society-wide discrimination as

the basis for a race-based program but, instead, was required to identify discrimination within

the local jurisdiction. Second, the case highlighted the need to present evidence grounded in

statistical analysis to justify the presence of discriminatory behavior. This includes evaluation

of ready, willing and able contractors when determining disparities. This evaluation is the

backbone of determining “available” businesses to use in computing disparity ratios, such that

the focus of any contracting program is narrowly tailored to affected businesses.

In contrast, the City of Richmond examined population gures to determine its race-conscious

contracting goal, without considering whether the goal reected the demographic make-up

of contractors that could actually perform the contracted work. An important outcome was

the Court declaration regarding the utility of anecdotal evidence as supporting and causal

information related to the quantitative analyses. The U.S. Supreme Court noted that anecdotal

evidence of discriminatory acts, when used in conjunction with statistical evidence, lends

support to broader remedial relief.

Adarand extended the strict scrutiny standard to federal programs, including the federal

DBE program related to use of U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) funds by states and

municipalities. Adarand VII provided distinct areas for disparity consultants to investigate

and compile results that support the institution of race-conscious programs. Most of the

Key Holdings in Croson:

•Strict scrutiny is the appropriate standard of judicial review, such that a race conscious

program must be based on a compelling governmental interest in remedying past

discrimination or its present effects and be narrowly tailored to achieve its objectives

•Ruled in Croson’s favor : the evidence did not pass strict scrutiny because the program

was applied regardless of whether the individual MBE had suffered discrimination.

•Must be evidence of race-based discrimination for each individual group that is

granted racial, ethnic or gender preferences

• Programs must focus on ready, willing and able contractors in determining disparities

•Anecdotal evidence of discrimination, in conjunction with statistical evidence,

supports the local government’s use of broader remedial relief (e.g., race-based)

Key Holdings in Adarand and Adarand VII

• Adarand extended application of strict scrutiny standard to federal programs

• Adarand VII found that Congress had a compelling interest, key sources of evidence were:

•Analysis of disparities in earnings, commercial loan denial rates, and declining

participation of MBEs after removal of race-conscious programs

•Post-Adarand, Congress revised the federal disadvantaged business enterprise (DBE)

program to include key Adarand findings, including language on ready, willing and able

contractor data to determine disparities.

Contracting Barriers and Factors Affecting Minority Business Enterprises: A Review of Existing Disparity Studies

8

Minority Business Development Agency | December 2016

disparity studies reviewed in this research contained both quantitative and qualitative analyses

investigating the issues explicitly discussed in Adarand VII.

CONCRETE WORKS OF COLORADO

Concrete Works of Colorado, Inc. v. City & County of Denver is a notable case involving a

challenge to municipality-enforced minority contracting programs.

14

This case is important

for two reasons: rst, it set the state and local standard for how courts evaluate compelling

interest with respect to race-preference programs. An inference of discrimination, not proof,

was acceptable for a government entity to justify a compelling interest in remediating

discrimination. Also, it placed the ultimate burden of proving a program’s unconstitutionality

on the plaintiff. Second, this was the rst local minority business program upheld after the

merits of a full trial.

15

Third, the case noted that anecdotal testimony revealed behavior that

was not merely “sophomoric or insensitive, but which resulted in real economic or physical

harm.”

16

The City and County of Denver provided credible witnesses who testied to witnessing

discriminatory treatment motivated by race or gender.

17

WESTERN STATES PAVING

Adarand challenged the implementation of the federal DBE program, as enacted by

Title 49 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 26. Since the initial constitutional challenge

led by Adarand, there have been a number of legal challenges with respect to State DOT

implementation of the federal DBE program. Although this report does not include

a comprehensive review of every challenge to DBE programs, it is important to recognize

that the legal history of these cases not only provides guidance to state DOTs implementing

programs to meet the concept of narrowly tailored, but also provides guidance with respect to

the types of evidence necessary to establish race-based programs and how to narrowly tailor

those programs.

14

Concrete Works of Colorado, Inc. v. City & County of Denver Colorado, 36 F. 3d 1513 (10

th

Cir. 1994) and Concrete Works of

Colorado, Inc. v. City and County of Denver, 321 F. 3d 950 (10

th

Cir. 2003) (Concrete Works IV).

15

Connecticut State Disparity Study, conducted by the Connecticut Academy of Science and Engineering, Phase I, 2013. After

a lengthy legal history, the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of Denver, noting that Denver did not hold the burden of

proving the existence of discrimination, rather it only had to demonstrate strong evidence of discrimination in the market to justify

the race- and gender-based remedial contracting programs (i.e., goals).

16

Concrete Works of Colorado, Inc. v. City and County of Denver, 321 F. 3d 950 (10

th

Cir. 2003).

17

The Court noted: “After considering Denver’s anecdotal evidence, the district court found that the evidence “shows that race,

ethnicity and gender affect the construction industry and those who work in it” and that the egregious mistreatment of minority and

women employees “had direct nancial consequences” on construction rms. Id. at 989, quoting Concrete Works III, 86 F. Supp.2d

at 1074, 1073. Based on the district court’s ndings regarding Denver’s anecdotal evidence and its review of the record, the court

concluded that the anecdotal evidence provided persuasive, unrebutted support for Denver’s initial burden. Id. at 989-90, citing Int’l

Bhd. of Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 339 (1977) (concluding that anecdotal evidence presented in a pattern or practice

discrimination case was persuasive because it “brought the cold [statistics] convincingly to life”).” (emphasis added)

Chapter 2: Legal Review

9

December 2016 | Minority Business Development Agency

While ongoing litigation pertaining to state DOT implementation of federal DBE programs

exists as of the date of this report, the constitutionality of the federal DBE program has been

upheld in past proceedings. However, in Western States Paving Co. v. Washington State DOT

(Western States Paving),

18

the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals found that although the State

of Washington DOT DBE program was constitutionally sound (i.e., it met the strict scrutiny on

its face), the program was not narrowly tailored. The main issue was the extent to which the

State of Washington considered the capacity of ready, willing and able DBE contractors, where

capacity represents a rm-level measure of whether a particular DBE contractor has the ability

to full the requirements of a particular contract (e.g., does it have the capacity to perform the

contracted work such that it can be considered ready, willing and able to bid on the project).

The Ninth Circuit found that the state had not adequately supported inclusion of capacity

considerations in determining the availability of DBE rms.

19

Further the Ninth Circuit determined that even where evidence of discrimination exists in a

recipient’s market, a narrowly tailored program can only apply to those minority groups who

have actually suffered discrimination. Thus, under a race- or ethnicity-conscious program, for

each of the minority groups to be included in any race- or ethnicity-conscious elements in

a recipient’s implementation of the federal DBE Program, there must be evidence that the

minority group suffered discrimination within the recipient’s marketplace.

20

ROTHE AND DYNALANTIC

Figure 2-1 highlighted a series of federal challenges to race-conscious contracting programs

separate from the Federal DBE DOT challenges. Figure 2-3 summarizes key ndings in legal

decisions related to Rothe Development Corporation and DynaLantic Corporation. The initial

Rothe case

21

involved a challenge to the Department of Defense’s implementation of the Small

Disadvantaged Businesses (SDB) program, while the DynaLantic

22

and second Rothe case

23

involved a challenge to the use of the 8(a) set-aside program.

18

Western States Paving Co. v. Washington State DOT, 407 F.3d 983 (9th Cir. 2005), cert. denied, 546 U.S. 1170 (2006)

19

Chapter 3 covers the concept of availability in greater detail. However, the methods of determining what constitutes an

“available” business for the purposes of analyzing disparities are often a signicant point of contention among practitioners. In

Croson, the City of Richmond failed to analyze specic MBEs, focusing only on the population of minorities in the surrounding

geographic area. As the Supreme Court noted, the appropriate standard is to look at the specic businesses that can compete for

and execute contracts within the particular industry and location. These are the available businesses that should be considered in

the disparity analysis.

20

As a result of the 2005 Western States Paving decision, numerous states implementing the federal DBE program using race-

conscious goals suspended existing programs to re-evaluate whether the programs were in compliance with the “narrowly tailored”

requirements.

21

Rothe Development Corp. v. U.S. Department of Defense, et al., 545 F.3d 1023 (Fed. Cir. 2008)

22

DynaLantic Corp. v. U.S. Department of Defense, 885 F.Supp. 2d 237 (D.D.C. 2012).

23

Memorandum Opinion, United States District Court for the District of Columbia, June 5, 2015, Rothe Development Corp.

v. Department of Defense, No. 12-CV-744 (led D.D.C. May 9, 2012).

Contracting Barriers and Factors Affecting Minority Business Enterprises: A Review of Existing Disparity Studies

10

Minority Business Development Agency | December 2016

FIGURE 2-3

KEY HOLDINGS IN THE ROTHE AND DYNALANTIC CASES

The rst Rothe case dealt specically with an issue regarding “relative capacity” which, similar

to Western States Paving, involves the computation of rms that are ready, willing and able to

bid and perform on particular contracts. Relative capacity arguments center around whether

a particular rm can effectively bid on and handle multiple projects, or if the rm happened to

win a project whether it could have the resources to bid on and perform the work required on

subsequent contracting opportunities (i.e., would winning one contract stretch rm resources

too thin to perform other contracts at the same time).

Key Holdings in Rothe (2008 Federal Circuit Court of Appeals):

•Despite disparity study results offered by the Department of Defense (DoD), there was no

record regarding the studies’ methodology before the federal circuit.

•Court rejected compelling interest argument because studies failed to account for relative

capacity of firms.

•Court found that Congress did not have a strong basis in evidence before it to conclude

that the Department of Defense (DoD) was a passive participant in racial discrimination in

relevant markets across the country.

Key Holdings in DynaLantic

•DynaLantic argued that the government did not provide sufficient evidence of prior race-

based discrimination in contracting in the relevant market.

•The Court agreed, holding that while the 8(a) program was constitutional on its face, it was

unconstitutional as implemented in DynaLantic’s situation, as the government did not

provide sufficient evidence that the discrimination in the relevant market negatively impacts

contractors in that market.

Key Holdings in Rothe (District Court of District of Columbia, 2015)

•Rothe brought a facial challenge to the constitutionality of the 8(a) program.

•In the June 2015 ruling, the Court upheld the constitutionality of the program on its face.

•Rothe appealed, with hearings in March 2016 and a decision due later in 2016.

Chapter 3: Disparity Study Basics

11

December 2016 | Minority Business Development Agency

CHAPTER 3

Disparity Study Basics

Conducting a disparity study is a comprehensive undertaking designed to analyze and inform

readers on the specic issues relevant to evaluating contracting behavior within a particular

geographic and industry area. In general, the primary purpose for conducting a disparity

study is to assess discrimination in public contracting when evaluating race- and gender-based

government actions designed to alleviate discriminatory behavior. As a result, the typical

disparity study covers multiple areas addressing the legal framework, applicable procurement

laws and regulations, denition of markets, identication of relevant businesses, measuring the

activity levels of the different businesses providing goods or services, utilizing independent

third-party data analysis to explore discriminatory behavior, incorporating anecdotal evidence,

and opining on the current state of existing race-neutral and race-conscious programs.

The central feature of a disparity study is a disparity analysis that determines the levels at which

minority, women, or disadvantaged business enterprises are utilized on public contracts. These

contracts can be at the federal, state, or local level and may encompass multiple industries.

Assuming a fair and equitable system of contracting, one would expect that the proportion

of contracts and contract dollar awards to minority, women or disadvantaged business

enterprises should be relatively close to the corresponding proportion of minority, women, or

disadvantaged business enterprises available to perform that work in the relevant market area.

24

In this respect, disparity studies seek to test whether observed differences are signicant, such

that inferences of discrimination support the observed disparities.

This section of the report focuses on explaining key components of the typical disparity study,

including denitions of key terms, calculations, and methodologies.

25

A typical disparity study

has the following components broken into ve general areas:

1. Foundation/Background (legal analysis, applicable laws, regulations, rules)

2. Procurement Data and Analysis (market denition and utilization analysis)

3. Availability/Disparity Computations (availability assessment and disparity

index computation)

4. Discrimination Assessment (statistical analyses, anecdotal evidence)

5. Evaluation & Recommendations (status of current programs, future goals and strategies)

24

Disparity Study: Metropolitan St. Louis Sewer District, Mason Tillman Associates, December 2012. See the Introduction and

p. 8-1 (as applied to subcontracts).

25

In addition, Appendix B contains a glossary of terms common to many disparity studies.

Contracting Barriers and Factors Affecting Minority Business Enterprises: A Review of Existing Disparity Studies

12

Minority Business Development Agency | December 2016

The information presented in this chapter is drawn from the review of disparity studies, reports,

and summaries, and represents the most frequently observed study components. As a result,

each disparity study, or each consultant conducting a disparity study, may vary in approach to

these general components as necessitated by the specics of each investigation. This chapter

begins with a brief overview of key study report sections, before discussing some of the more

difcult and contentious topics in greater detail.

GENERAL OVERVIEW OF DISPARITY STUDIES

Foundation/Background

Two elements generally comprise the foundation and background sections of disparity reports.

The rst is a synopsis of relevant case law and legal precedent that provides the standards by

which consultants conduct disparity studies. The second is an understanding and overview

of rules, regulations, and ordinances that cover existing procurement procedures or enforce

existing contracting programs designed to alleviate or remediate contracting disparities.

The most cited example is requirements associated with the federal disadvantaged business

enterprise (DBE) program for federally-funded projects. Figure 3-1 outlines key components

of the legal review and applicable laws, regulations, and rules included in disparity studies.

FIGURE 3-1

LEGAL REVIEW AND REQUIREMENTS FOR DISPARITY STUDIES

Disparity studies typically include a legal review, as discussed in Chapter 2, but with greater

detail and application to the relevant jurisdiction and program type. As shown on the right

hand side of Figure 3-1, disparity studies also typically incorporate an overview of the relevant

regulations, rules, and ordinances surrounding agency contracting. For state DOTs using

federal funds for projects, this entails understanding the legislation in the federal DBE program,

including the considerations of legislation such as the Transportation Equity Act for the

Legal Analysis and Summary

•Seminal cases ( Croson)

•Strict scrutiny

•Compelling interest

•Narrowly tailored

•Jurisdictional cases

•Circuit courts (appellate rulings)

•District court

•State/county courts

Applicable laws, regulations, rules

•Existing regulations (e.g., Local

ordinances governing minority

programs)

• Procurement rules for particularly

agency

•Details/rules about M/WBE or DBE

programs in place

•Federal DOT DBE rules

•Per 49 CFR 26

•TEA-21 considerations

Foundation/Background:

Chapter 3: Disparity Study Basics

13

December 2016 | Minority Business Development Agency

21

st

Century (TEA-21). In contrast, disparity studies involving local or municipal agencies focus

on the general procurement rules in place for the particular agency, municipality, or state in

which the agency resides.

Procurement Data and Analysis

The next element in most disparity studies is a review of the underlying procurement data used

in conducting a disparity study. By denition, adequate procurement data (i.e., who, when,

where, what, and how much of contracts) is a prerequisite to determining whether contracting

disparities exist for minority business enterprises. Figure 3-2 illustrates the key components of

procurement data analysis.

FIGURE 3-2

KEY COMPONENTS OF PROCUREMENT DATA ANALYSIS

The left hand side of Figure 3-2 presents the concept of market denition, where a market is

dened along both geographic and product dimensions. Market denition is an economic

concept that looks to substitutability and is intended to determine who is competing for public

contracts along geographic and product lines. Almost every study had an explicit denition of

both geographic and product markets, as these are required in order to determine the extent to

which disparities exist among competitive market participants.

With respect to the geographic market denition, some studies dene the market based on

vendor locations that account for a certain percentage (e.g., 75 percent) of dollar expenditures

Figure 3-2

Key Components of Procurement Data Analysis

Market Definition

• Product

•Geographic

•Usually driven by analysis of

procurement records

•Where are contractors located

receiving awards?

•In what industries (e.g., NAICS)

are these awards?

•Typically some threshold measure

applied to dollars to define product

and geographic markets

•Typically state, MSA, county, city are

standard starting points

Utilization Analysis

•Identify all relevant procurement

records to:

•Determine award amounts

•Identify and classify recipients

•Typically look at both prime and

subcontracts

•Often quality issues with data,

particularly on subcontracts

•Goal is to compute the percentage of

contracts and/or dollars going to each

group in a specific geographic and

product market

•Example, African American

firms received 3.8% of total

construction prime dollars

awarded in 2009 within a

particular jurisdiction

Procurement Data -Based Analysis:

Contracting Barriers and Factors Affecting Minority Business Enterprises: A Review of Existing Disparity Studies

14

Minority Business Development Agency | December 2016

in the study period. Other studies employed a less rigid threshold, but still examined vendor

locations where the “majority” or “most” contract dollars were awarded. The most common

units of geographic boundaries employed were state, county, city, or metropolitan statistical

area (MSA),

26

where study authors examined locations of vendors competing for and winning

procurement awards for the particular agency.

Existing disparity studies dene product markets in a similar fashion, with a focus on assessing

the economic parameters that indicate which rms compete for procurement actions given

particular contract requirements. For example, a construction rm and a janitorial supplies

rm may not compete on similar contract proposals given the difference in the industry in

which each company operates. In determining contract disparities, it is erroneous to assume

that these two rms are both “ready, willing and able” to compete and execute a large scale

construction project. In fact, only the rst rm is available within the dened product market

of construction. Study authors are especially focused on identifying competing rms within

particular product or industry categories such that any observed contracting disparities are

narrowed to the scope of potentially affected rms within the dened product market. In

most instances, the studies dened product markets at a very high level of aggregation, e.g.,

“Construction” or “Goods and Services.” In other instances, studies dened markets more

narrowly, grouping rms by North American Industry Classication System (NAICS) codes.

The right hand side of Figure 3-2 focuses on the extent to which minority-owned rms are

utilized in contracting by a particular government agency or agencies. Utilization is a core

disparity study concept and represents the share of prime and/or subcontract dollars that an

agency awarded to a particular type of business enterprise during a particular time period. It

is typically expressed as a percentage relative to the total amount awarded to all contractors

in the same time period. Calculating utilization follows dening applicable geographic and

product markets. Figure 3-3 illustrates a simple utilization calculation for hypothetical minority

business enterprises (MBEs) operating in a particular market.

26

MSAs are dened by the Ofce of Management and Budget (OMB) and are used by multiple agencies to delineate geographic

areas based on groupings of population data.

Chapter 3: Disparity Study Basics

15

December 2016 | Minority Business Development Agency

FIGURE 3-3

UTILIZATION EXAMPLE USING CONTRACT AWARDS

Underlying the utilization computation are several key inputs. First, the process requires

identifying all relevant procurement records to determine award amounts and identify and

classify recipients by ownership type. Almost always, disparity study consultants are limited by

the quality of the procurement data collected and maintained by the government agency. In

some cases, data are incomplete, missing or simply not captured. A common example is that

a number of municipalities fail to capture subcontractor data in their procurement records.

Nevertheless, disparity studies typically attempt to examine both prime and subcontractor

data. Second, the process leverages the denition of the geographic and product markets to

determine the utilization within these markets.

Availability and Disparity Calculations

The market denition and utilization calculations discussed above only tell part of the

contracting disparity story. In order to measure actual contracting disparities, studies compute

the total number of businesses able to perform (or “available”) contract work within the dened

market areas. The denition of an “available” business is a critical element of disparity studies,

and as discussed in more detail below, one of the most contentious areas among consultants

and practitioners. Figure 3-4 highlights some of the different methods that have been used

over time to compute “available” businesses, while also outlining the disparity

index computation.

MBE

$100

Non-MBE

$500

Contracts within a Relevant:

•Geographic Market

•Product Market

Contracting Barriers and Factors Affecting Minority Business Enterprises: A Review of Existing Disparity Studies

16

Minority Business Development Agency | December 2016

FIGURE 3-4

METHODOLOGIES FOR CALCULATING AVAILABILITY AND

DISPARITY INDICES

After determining the number of available businesses, disparity studies typically include

disparity indices for each business type (e.g., MBE, WBE or DBE) within each product and

geographic market. In most cases, existing disparity studies also compute these disparity

indices over multiple time periods and for individual racial and ethnic groups (e.g., African

American, Hispanic-American, etc.). Formulaically, the disparity index represents the utilization

divided by the availability. Some consultants multiply the resulting index by 100 as opposed

to expressing the result as a fraction. Figure 3-5 illustrates a simple hypothetical calculation of

a disparity index for African American construction rms operating in a particular geographic

market in one year.

Availability Assessment

•Measuring the number of ready,

willing and able firms by group within

market areas

•Numerous sources/methods over the

years

•City of Richmond’s erroneous

“population measure”

•Use of Census data on number

of businesses

•Use of bidder lists

•Use of vendor, government or

trade association lists

•Use of third-party data (e.g.,

D&B)

•Custom census approaches