!

!

Enhancing Pretrial Justice in Cuyahoga County:

Results From a Jail Population Analysis

and Judicial Feedback

John Clark

Rachel Sottile Logvin

Pretrial Justice Institute

September 2017

!

!

!

2!

Table of Contents

Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………..3

Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………….5

Methods used for data collection and analysis……………………………………..…5

Trends in Population, Crime and Criminal Case Filings………………………..…6

Jail population data trends…………………………………………………………………..9

Jail snapshot profile……………………………………………………………………………11

Summary of judicial questionnaire and recommendations for further

stakeholder education and engagement……………………………………………….17

Summary and Discussion…………………………………..……………………………….20

Recommendations……………………………………………………………………………..23

APPENDIX A: List of Data Elements Requested for

Jail Population Analysis……………………………………………………………....…….26

APPENDIX B: Misdemeanor and Felony Filings Tables…..……………………..27

APPENDIX C: Judicial Survey Results……….…………………………………………29

!

!

!

3!

Executive Summary

To assist in its ongoing examination of the bail system in Cuyahoga County, the Cuyahoga

County Court of Common Pleas, in coordination with the American Civil Liberties Union of

Ohio, asked the Pretrial Justice Institute (PJI) to review elements of the Cuyahoga County

pretrial justice system. PJI examined case filing trend data, analyzed data from a snapshot of

persons released on a particular date from four facilities—the Cuyahoga County Jail plus three

municipal jails—and solicited feedback from the Court of Common Pleas and municipal court

benches regarding needed enhancements to the bail system. This report presents the findings

from that effort.

Here is a summary of the major findings and recommendations.

Trend Data

• Despite significant declines in the number of reported violent and property crimes in

Cuyahoga County, and even larger declines in the number of criminal cases filed in both

the municipal courts and the Court of Common Pleas, there has not been a

commensurate reduction in the number of jail bookings or average daily populations.

• The Cuyahoga County Jail has been operating, on average, at over 100% capacity in four

out of the past five years.

Jail Population Analysis

• There were significant differences in the demographic characteristics, particularly

regarding race, of those released from the three municipal jails on the date of the

snapshot, June 1, 2017, compared to those released from the Cuyahoga County Jail.

• Twenty-five percent of the felony pretrial population in the Cuyahoga County Jail sample

remained detained throughout the pretrial period, with an average length of stay in

pretrial detention of 104 days. Of the 75% who were released, whether by financial or

non-financial means, the average length of stay was 17 days.

• Thirty-eight percent of the Cuyahoga County jail population that was released on

personal bond spent more than one week in pretrial detention before that release.

• Twenty-eight percent of those with a bond of $5,000 or less never posted it and

remained detained throughout the pretrial period.

• There was a correlation between seriousness of charge and bond type and bond amounts

in the Cuyahoga County Jail sample. Those charged with Felony 1 and 2 offenses were

much more likely to get a secured money bond than those charged with Felony 4 and 5

offenses, and, of those receiving a secured bond, much more likely to receive a higher

bond.

Judicial Feedback

PJI invited all Municipal and Common Pleas judges to participate in a voluntary questionnaire

consisting of nine questions to identify areas of potential judicial education, stakeholder

engagement, and process improvements. Here is a summary of the results:

• Thirty-three judges completed the questionnaire.

• Over 75% of the judges felt informed about the strengths and weaknesses of the bail

system in their jurisdiction, and about ways that it might be improved.

!

!

!

4!

• 82% of the judges felt there is value in the Criminal Justice Committee examining the

pretrial process in Cuyahoga County and its municipalities.

• 79% felt it is important to provide judicial-specific education to understand possible

ways to improve the bail system in the areas of actuarial risk assessment (87%) and

research-informed risk management strategies (87%).

• 13% felt uncertainty about the use of actuarial risk assessment tools with some

concern that they may cause additional issues.

• 84% of the respondents were “somewhat familiar with” to “not familiar with at all”

the use of supervision matrices, while only 15% of the judges were “very familiar

with” the uses of supervision matrices.

Recommendations

1. Conduct a training on the fundamentals of pretrial justice for the judges of the Court of

Common Pleas and of the municipal courts.

2. Conduct a one-to-two day summit of the judiciary in Cuyahoga County to identify a clear

vision statement pertaining to pretrial practices within the county.

3. Pilot test 2-4 projects in both the Municipal and Common Pleas Court introducing research

and evidenced-based practices in pretrial improvements.

4. Actively and consistently communicate the plans, progress, and outcomes of the pilot sites to

the entire judiciary, as well as other key stakeholders, such as prosecutors, defenders, law

enforcement, victim advocates, and the community at large.

5. Based on the results of the pilot sites, plan and implement an expansion of new practices

system-wide.

!

!

!

5!

Introduction

In 2016, the Cuyahoga County Court of Common Pleas began a thorough examination of bail

practices in the county, and formed several committees to look at various aspects of the issues

the jurisdiction was facing regarding bail, and to explore ways to address those issues. As part of

that process, the Court, working in concert with the American Civil Liberties Union of Ohio,

asked the Pretrial Justice Institute (PJI) to examine case filing trend data, analyze data from a

one day snapshot of persons released from four facilities—the Cuyahoga County Jail plus three

municipal jails—and solicit feedback from the Court of Common Pleas and Municipal Court

benches regarding needed enhancements to the bail system.

Cuyahoga County is not alone in seeking to enhance its bail practices. State and county

jurisdictions across the country are doing so, spurred by (1) research showing the clear benefits

of risk-based over money-based bail decision making, (2) recognition of the costs to both the

defendant and the tax-paying public of the money-based bail system; and (3) a wave of federal

court rulings finding the money-based bail system to violate the due process rights guaranteed

by the U.S. Constitution. Many states have amended their bail statutes or court rules to establish

a presumption for pretrial release on the least restrictive conditions, with clear limits on the use

of secured financial bonds. The State of New Jersey is the most prominent example, going from

a bail system that was almost entirely reliant on the use of money bonds to one that has

essentially eliminated the use of money in bail.

Methods used for data collection and analysis

PJI was asked to analyze data from four jail facilities within Cuyahoga County—Solon City

Detention Center, Parma Justice Center, North Royalton City Jail and Cuyahoga County

Correction Center. These four facilities are among nine in the county that are Full Service Jails.

There are also 42 other facilities in the county that can hold inmates, including numerous police

lock-ups.

The first three of the facilities included in the analysis—Solon, Parma and North Royalton—are

municipal jails, holding those charged with or sentenced on misdemeanors, as well as those

newly charged with felonies. The Cuyahoga County Detention Center holds those charged with

or convicted of felonies, as well as some municipal cases.

PJI requested and received data from each of these four facilities. (See Appendix A for the list of

data elements requested.) The Cuyahoga County jail data had substantial missing data on

several key elements, such as bond amounts. With the assistance of Court of Common Pleas

staff, PJI was able to use the Court’s online case management system to fill in the gaps of

missing information.

PJI also conducted a voluntary questionnaire for all Municipal and Common Pleas judges.

Thirty-three judges completed the survey.

In addition, all judges were invited to participate in a brief telephone follow-up interview,

conducted by PJI. Six judges, three from municipal courts and three from the Court of Common

Pleas, volunteered to do so. These follow-up interviews were designed to actively engage and

include the judicial perspective, identify key areas of concern, and glean the overall readiness of

the judiciary for any recommended forthcoming pretrial improvements.

!

!

!

6!

Trends in Population, Crime and Criminal Case Filings

The general population of Cuyahoga County declined slightly between 2012 and 2013, and then

again between 2013 and 2014, before rising slightly in 2015. (See Chart 1)

Chart 1

As Chart 2 shows, the reported number of violent crimes in Cuyahoga County dropped slightly

between 2013 and 2015, the last year for which figures are available, while the reported number

of property crimes fell more steeply, from over 37,000 in 2012 to around 26,000 in 2015.

1,152,517

1,096,980

1,078,120

1,099,244

1,040,000

1,060,000

1,080,000

1,100,000

1,120,000

1,140,000

1,160,000

2012 2013 2014 2015

Population

Year

Population Cuyahoga County

!

!

!

7!

Chart 2

Many of the criminal cases in Cuyahoga County start in one of the 14 municipal courts located in

the county. Misdemeanor cases remain in the municipal courts, while felony cases are referred

to the Court of Common Pleas. As Chart 3 shows, felony filings in municipal courts dropped

slightly from 2014 to 2015, after rising slightly between 2012 and 2014. The number of

misdemeanor cases fell steadily over the four-year period between 2012 and 2015. (See

Appendix B for the list of these filings in each of the municipal courts.)

When combining felony and misdemeanor filings in municipal courts, total criminal case filings

fell from 70,337 in 2012 to 52,428 in 2015.

37,453

34,465

32,427

26,240

6,460

6,728

6,051

5,502

0

1,000

2,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

6,000

7,000

8,000

9,000

10,000

0

5,000

10,000

15,000

20,000

25,000

30,000

35,000

40,000

2012 2013 2014 2015

Violent

Property

Year

Crimes Reported in Cuyahoga County

!

!

!

8!

Chart 3

Felony filings in the Court of Common Pleas have also fallen, from about 12,500 in 2012 to

about 10,300 in 2015. (See Chart 4.)

63,391

58,889

55,542

44,656

6,946

7,443

8,449

7,772

0

1,000

2,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

6,000

7,000

8,000

9,000

10,000

0

10,000

20,000

30,000

40,000

50,000

60,000

70,000

80,000

90,000

100,000

2012 2013 2014 2015

Felony

Misdemeanor

Year

Filings in Municipal Courts

!

!

!

9!

Chart 4

Jail population data trends

The population of any jail is determined by two factors—the number of people who are booked

into the facility, and how long they stay. Table 1 shows how the inter-relationship between

bookings, length of stay and the population played out over the past five years in the four jails

included in this analysis—Solon, Parma, North Royalton, and Cuyahoga County.

The bookings into the Solon City Detention Center, a 26-bed facility, were consistent from 2012

through 2015, then rose by several hundred in 2016. The average length of stay fell a full day

between 2012 and 2015, resulting in a drop of the average daily population from 19 to 12. The

average daily population rose back up to 17 in 2016 with increases in both bookings and average

length of stay.

In the Parma Justice Center Jail, the number of bookings dropped steadily each year, but the

average length of stay fluctuated, resulting in a fluctuating average daily population. Despite

there being 1,000 less bookings in 2016 than 2012, the average daily population rose from 17 to

18. This was because the average length of stay increased from 1.7 to 2.4 days.

The North Royalton City Jail, which has a bed capacity of 14, saw fluctuations in the number of

bookings and length of stay over the five-year period, but experienced a relatively stable average

daily population. For example, the jail had an average daily population of 9 in both 2013 and

2016, despite the fact that the number of bookings went from 944 in 2013 to 1680 in 2016. The

12,505

11,601

11,701

10,333

0

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

12,000

14,000

2012 2013 2014 2015

Filings

Year

Felony Filings in Common Pleas Court

!

!

!

10!

reason that the average daily population remained stable was because the average length of stay

decreased from 3.5 days in 2013 to 2 days in 2016.

In the Cuyahoga County Jail, the number of bookings and the average length of stay have

remained fairly constant, resulting in average daily populations that show little variation. The

county jail has 2,100 beds, meaning that, on average, it has been operating at over 100%

capacity for at least four of the past five years.

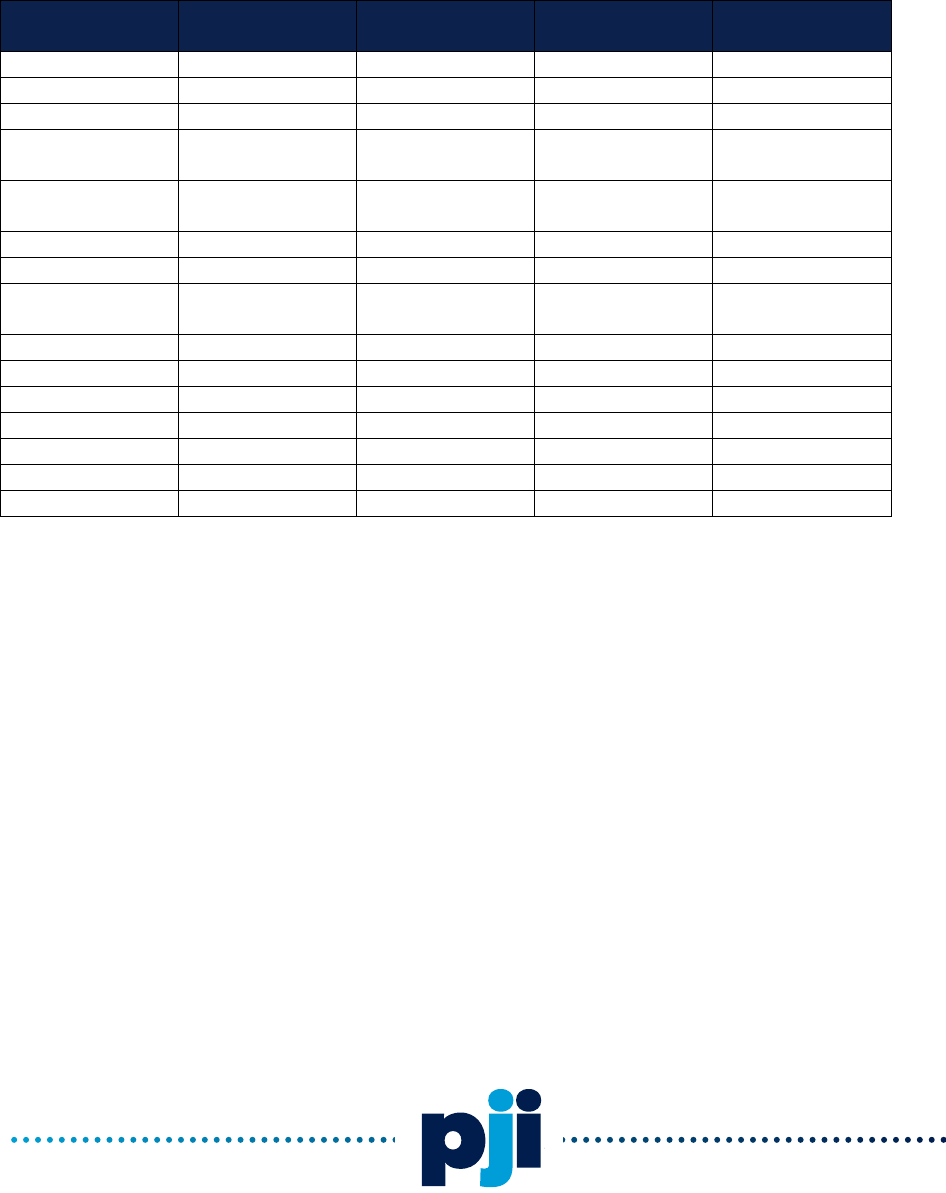

Table 1

Bookings, Average Length of Stay and Average Daily Population:

Solon, Parma, North Royalton and Cuyahoga County Jails

Solon City Detention Center

Year

Annual Bookings

ALOS

ADP

2012

1905

3.3 days

19

2013

1926

3 days

16

2014

1905

2.3 days

12

2015

1900

2.3 days

12

2016

2275

2.7 days

17

Parma Justice Center Jail

Year

Annual Bookings

ALOS

ADP

2012

3669

1.7 days

17

2013

3316

2.8 days

25

2014

3107

2.6 days

22

2015

2917

3.1 days

25

2016

2685

2.4 days

18

North Royalton City Jail

Year

Annual Bookings

ALOS

ADP

2012

1056

3.4 days

10

2013

944

3.5 days

9

2014

1377

2.9 days

11

2015

1694

2.2 days

10

2016

1680

2 days

9

Cuyahoga County Jail

Year

Annual Bookings

ALOS

ADP

2012

25,367

30 days

2104

2013

23,951

31 days

2023

2014

25,104

32 days

2180

2015

25,374

31 days

2156

2016

26,334

30 days

2152

Despite the declines in reported crimes and criminal case filings, the number of annual bookings

rose in three of the four facilities, and the average daily populations of the four jails have

remained, for the most part, constant.

!

!

!

11!

Jail snapshot profile

A jail population analysis was conducted on all persons released on June 1, 2017 from the four

individual jail facilities—Solon, Parma, North Royalton, and Cuyahoga County Jails. For the

purposes of this analysis, the data from the three municipal jails—Solon, Parma and North

Royalton—were combined.

As Table 2 shows, there were significant differences in the demographic characteristics of those

released from Solon, Parma and North Royalton compared to the Cuyahoga County Jail. For

example, 30% of those released from the smaller jails were female, compared to 17% from the

Cuyahoga facility. Additionally, looking at the racial breakdown, whites represented 75% of the

smaller jails sample but only 24% of the Cuyahoga. Finally, those released from the Cuyahoga

jail were younger–30% were 25 years old or younger, compared to 20% in the other three jails.

Table 2

Demographic Characteristics of Individuals Released on June 1, 2017

Solon, Parma, North

Royalton Jails

Cuyahoga County

Jail

Number

Percent

Number

Percent

Gender

Male

14

70%

94

83%

Female

6

30%

20

17%

Race

White

15

75%

27

24%

Black

5

25%

83

73%

Other

0

--

4

3%

Age

18-20

0

--

8

7%

21-25

4

20%

26

23%

26-30

3

15%

20

18%

31-40

8

40%

37

32%

41-50

3

15%

11

10%

Over 50

2

10%

12

11%

Solon, Parma and North Royalton Jails

The combined snapshot of the first three jails–Solon, Parma and North Royalton–show that

these jails have very small volume and move people out very quickly. A total of 20 individuals

were released from these facilities on June 1, 2017–four from Solon, nine from Parma and seven

from North Royalton.

Sixteen of these individuals (80%) were in pretrial status, three were serving sentences, and one

was turned over to another authority. Of the 16 who were in pretrial status, four were charged

with a felony as the most serious charge and 12 were charged with a misdemeanor. All 16 were

released from custody on a bond. Four were released on personal bond, eight posted a 10%

bond, and four posted a cash or surety bond. The table below shows the bond amounts for the

individuals who bonded out through cash, surety or 10%.

!

!

!

12!

Table 3

Bond Amounts Posted Solon, Parma and North Royalton Jails

Bond Amount

Frequency

Percent

Up to $500

2

17%

$501 to $1,000

1

8%

$1,001 to $3,000

2

17%

$3,001 to $5,000

7

58%

The average length of stay in detention for the 16 was 1.1 days. Six were released the same day

that they were detained, eight the day after, and one more on the third day. One was released

after seven days.

It may be that municipal jails within the county where the demographics of the population,

particularly regarding gender and race, more closely match the demographics of the Cuyahoga

County jail population would have results that are different than those reported here.

Cuyahoga County Jail

The Cuyahoga County Jail has a much higher volume than the other three and a much longer

length of stay. A total of 114 persons were released from the jail on June 1, 2017. These

individuals had an average length of stay of 39 days.

Of the 114 persons released on that date, seven had been in custody solely to serve a sentence, 20

were there solely on probation or parole violations, 15 had municipal court cases, 63 were in

felony pretrial status, and nine had miscellaneous issues.

An individual was counted as being in felony pretrial status if he or she was in custody on at

least one felony, even if just to be booked and released, at any point while the case was pending.

This would include those who were released on personal or money bond before their first

appearance in Common Pleas Court, as well as those who remained in custody after that first

appearance. In other words, it includes those who were released at the first bail hearing in

municipal court, those who bonded out between the dates of the first municipal court bail

hearing and the first appearance in Common Pleas Court, and those unable to post a bond that

was set in municipal court. It does not include those in custody solely on probation or parole

violations, while serving a sentence (unless they started their custody while in pretrial status and

then remained in custody as part of their sentence), or because of other miscellaneous

circumstances (e.g., being brought in from a state institution to attend a hearing in court).

Table 4 summarizes the pretrial release outcomes of the 63 people who were in felony pretrial

status when released from the Cuyahoga County Jail on June 1, 2017. As the table shows, 33%

had been released on personal recognizance while their cases were pending, 27% had been

released on a 10% bond, 14% had been released on a surety bond, and 25% had remained in

custody throughout the pretrial period.

!

!

!

13!

Table 4

Pretrial Release Outcomes

Pretrial Release Status

Percent

Average

Length of Stay

Average Bond

Amount

Released on personal bond

33%

32 days

N/A

Released on 10% bond

27%

6 days

$3,600

Released on surety bond

14%

7 days

$31,235

Not released pretrial

25%

104 days

$23,900

Of those who were released on personal bonds, the average length of stay in custody, from the

date of arrest through release on the bond, was 32 days, although this figure was skewed by a

few individuals who spent several months in custody before being released on personal bond.

About half of those who were released on personal bond achieved that release within one day of

arrest. On the other hand, 38% of these individuals spent more than one week in custody before

their initial bond was changed to a personal bond.

For those who posted a 10% bond, the average bond amount was $3,600 and the average length

of stay in custody before posting the bonds was 6 days. Of those who posted a surety bond, the

average bond amount was $31,235, and the average length of stay in jail before posting was 7

days.

The total average length of stay in jail for those released by any of these means–personal bonds,

10% bonds, or surety bonds–was 17 days.

Of the 25% of those in pretrial status who were incarcerated throughout the pretrial period on

bonds they did not post, the average bond amount was $23,900. The average length of stay in

custody of that group was 104 days.

The next table takes a deeper look at the time spent in pretrial detention, comparing time in

detention for those who obtained their release at some point during the pretrial period to those

who did not. As the table shows, 41% of those who were released obtained that release within

two days of arrest, and another 28% within a week. But about 30% of those who were released

while their cases were pending spent more than one week in detention, including 6% who spent

more than 90 days in custody. Of those who were never released during the pretrial period, the

majority spent more than 60 days in custody.

!

!

!

14!

Table 5

Time Spent in Pretrial Detention*

Released Pretrial

Not Released Pretrial

Time spent in

custody

Number

Percent

Number

Percent

2 days or less

19

41%

0

--

3 to 7 days

13

28%

1

6%

8 to 14 days

5

11%

0

--

15 to 21 days

3

6%

0

--

22 to 28 days

1

2%

1

6%

29 to 35 days

1

2%

0

--

36 to 60 days

2

4%

4

25%

61 to 90 days

0

--

1

6%

91 to 120 days

1

2%

3

19%

121 to 150 days

1

2%

4

25%

151 to 180 days

0

--

0

--

Over 180 days

1

2%

2

13%

Total

47

100%

16

100%

*For those defendants who were released, this represents the number of days they spent in

pretrial detention between their arrest date and the date that they were bonded, were

sentenced, or their case was dismissed. For those not released, it represents the time between

their arrest and the point at which they were no longer in pretrial status, i.e., they were

sentenced or the case was dismissed.

Table 6 compares the characteristics of those released during the pretrial period, whether on

personal bond, 10% bond, or surety bond, to those not released. As the table shows, the pretrial

release rate rose steadily from a low of 43% for those charged with a Felony 1 to a high of 87%

for those charged with a Felony 4, before dropping to 79% for those charged with a Felony 5. The

number of charges was also correlated with whether the defendant was released pretrial, with

85% of those with just one count being released, compared to 25% of those with five or more

charges. Those with set bond amounts of $10,000 or less were much more likely to be released

than those with higher bond amounts.

!

!

!

15!

Table 6

Characteristics of Pretrial Defendants: Released vs. Not Released

Released Pretrial

Not Released Pretrial

Number

Percent

Number

Percent

Released Pretrial

47

75%

16

25%

Charge Classification

Felony 1

3

43%

4

57%

Felony 2

5

63%

3

37%

Felony 3

6

75%

2

25%

Felony 4

14

87%

2

13%

Felony 5

19

79%

5

21%

Number of Charge Counts

1

34

85%

6

15%

2

6

67%

3

33%

3

5

71%

2

29%

4

1

33%

2

67%

5 or more

1

25%

3

75%

Bond Amount*

Up to $5,000

13

72%

5

28%

$5,001 to $10,000

4

67%

2

33%

$10,001 to $20,000

2

40%

3

60%

$20,001 to $30,000

4

57%

3

43%

$30,001 to $50,000

2

50%

2

50%

$50,001 to $100,000

0

0

1

100%

Over $100,00

1

100%

0

0

*For defendants who were released, the bond amounts reflect those posting a surety or 10%

bond. Those released on personal bonds are not reflected here.

The data show that bail decisions are highly correlated with the charge type. As the chart below

shows, over 80% of those charged with a Felony 1 as the most serious offense had a secured

bond set, as did 100% of those charged with a Felony 2 and over 80% of those with a Felony 3.

By contrast, nearly 60% of those charged with a Felony 5 had a personal bond set.

!

!

!

16!

Chart 5

Additionally, as the next chart shows, when secured bonds were set, the average bond amounts

rose along with the seriousness of the charge. The average bond amount for those charged with a

Felony 1 was $75,416, compared to just over $5,000 for those charged with a Felony 5.

14

13

31

58

86

100

87

69

42

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

F1 F2 F3 F4 F5

% of total bonds set

Charge Level

Type of Bonds Set By Charge Level

Personal Bond Set

Secured Bond Set

!

!

!

17!

Chart 6

Summary of judicial questionnaire and recommendations for

further stakeholder education and engagement

Of the 33 judges who completed the questionnaire, over 75% said that they felt informed (“very

well informed” to “well informed”) about the strengths and weaknesses of the bail system in

their jurisdiction, and about ways that it might be improved.

Eighty-two percent of the judges felt there is value (“very valuable” to “somewhat valuable”) in

the Criminal Justice Committee examining the pretrial process in Cuyahoga County and its

municipalities. None of the respondents felt there is “no value at all” in examining the pretrial

process.

As Chart 7 shows, 79% felt it is important to provide judicial-specific education to understand

possible ways to improve the bail system.

$75,416

$25,625

$17,285

$8,772

$5,050

$0

$10,000

$20,000

$30,000

$40,000

$50,000

$60,000

$70,000

$80,000

F1 F2 F3 F4 F5

Average Bond Amount

Charge Level

Average Secured Bond Amounts

By Charge Level

!

!

!

18!

Chart 7

When asked about meaningful and valuable areas of further education, judges noted the

following top five areas that they felt were most important:

• Actuarial risk assessment (84%)

• Research-informed risk management strategies (84%)

• Engaging stakeholders (77%)

• Addressing racial and economic disparities in the pretrial process (55%)

• The national landscape—what is happening to enhance the bail decision-making

nationally (52%).

The questionnaire explored further the familiarity and usefulness/value of actuarial risk

assessment tools. As Chart 8 highlights, 79% of the judges shared an overall lack of familiarity

with actuarial risk assessment tools (responses were “somewhat familiar with” to “not very

familiar with”). Upon further examination of the perceived value of actuarial risk assessment

tools, 78% of the respondents view them as either “very important” or “important to understand

more” as part of the judicial decision making process. Of the respondents, it is important to note

that 13% felt uncertainty about the use of actuarial risk assessment tools, with some concern

that they may cause additional issues. All of the judges felt actuarial risk assessment tools are of

some value, with none responding they are “Not useful in the bail decision.”

58%!

21%!

12%!

9%!

0%!

0%!

10%!

20%!

30%!

40%!

50%!

60%!

70%!

Very!valuable! Somewhat!valuable! Neutral! Not!very!valuable! No!value!at!all!

Do!you!see!value!in!judicial-specific!educaGon!to!understand!the!

possible!acGons!to!improve!the!bail!system!being!examined!by!the!

Criminal!JusGce!CommiLee?!

Value!in!Judicial-Specific!EducaGon!

!

!

!

19!

Chart 8

The judges identified supervision matrices as another area to include in judicial education; 84%

of the respondents were “somewhat familiar with” to “not familiar with at all,” while only 15% of

the judges were “very familiar with” the uses of supervision matrices.

Recognizing that each bail decision is different, judges were asked to rank in order of

importance what they generally consider when making a decision. Chart 9 highlights the

respondents’ rankings, on a scale of 1 to 8, with 1 being the most important (note: the score

represents a cumulative average where the higher score summarizes the highest ranking):

• Public Safety—reasonable assurances the person does not commit a new crime (7.32)

• Appearance—reasonable assurances the person appears in court (6.38)

• Identifying people who have specific mental health and/or substance use needs that

could safely be served outside of pretrial detainment (5.70)

• Reducing racial, ethnic, and economic disparities in our jail population and criminal

proceedings (4.79)

• Maximizing release—each person has a presumption of release with the least restrictive

conditions (4.59)

• Reducing our jail population in a responsible, and meaningful manner where the

population in our jail is reserved for the highest-risk individuals and those serving a

sentence (3.93)

• Case processing—improving the timeliness and effectiveness of the movement of the case

(2.97).

21%!

40%!

30%!

9%!

0%!

5%!

10%!

15%!

20%!

25%!

30%!

35%!

40%!

45%!

Very!familiar! Somewhat!familiar! Not!very!familiar! Not!familiar!at!all!

Familiarity!with!Actuarial!Pretrial!Risk!Assessment!tools!(N=33)!

Familiarity!with!Actuarial!Pretrial!Risk!Assessment!tools!(N=33)!

!

!

!

20!

Chart 9

PJI conducted separate follow-up telephone interviews with three Municipal Court judges and

three Common Pleas judges. Several issues were raised by the judges in these interviews. Judges

spoke of the need for more active engagement by defense. Attorneys are not always present at

the initial bond hearing, meaning judges do not have their input when making bail decisions.

Furthermore, in many instances defense attorneys are not filing bond review motions when such

efforts might be successful in getting secured bonds reduced or changed to personal bonds.

Judges also said that they sometimes feel compelled to set higher bonds because of procedural

reasons; for example, they are provided with incomplete information about the alleged offense

or the defendant when making their decisions. The judges also spoke of the inconsistency of

resources, with some courts having access to risk assessments and supervision services, and

others not. Several also spoke of their concerns that some secured bonds are being set as a way

to raise revenue in municipalities.

As for what they would like to see, several said that they would like to have access to risk

assessments and supervision, and would like training and education on how to best use these

tools. They would like to be able to use data to help inform their decisions. Some judges said

they would like to see plans for a central booking facility implemented. Several said that they

would be willing to pilot test these kinds of changes in their courtrooms before being expanded

system-wide. One judge expressed the opinion that the system works fine now, and that no bail

reform is needed.

Summary and Discussion

In June 2017, the Ohio Sentencing Commission approved a report that had been prepared by its

Ad Hoc Committee on Bail and Pretrial Services. The report included recommendations that the

State of Ohio, through statute or court rule changes, should implement to enhance pretrial

7.32!

6.38!

4.59!

3.93!

4.79!

5.7!

2.97!

1!

2!

3!

4!

5!

6!

7!

8!

Recognizing!that!every!bail!decision!is!different,!rank!in!order!of!

importance!what!you!generally!consider!when!making!a!

decision.!Rank!in!order!of!importance,!with!1!being!the!most!

important!and!8!being!the!least!important!

!

!

!

21!

justice throughout the state. Among the recommendations were that the legislature mandate

and fund the use of a validated pretrial risk assessment tool and that the Supreme Court adopt a

rule requiring judges to consider the results of the risk assessment in their bail decisions.

1

The recommendations of Sentencing Commission Report, which addressed the state as a whole,

align well with the findings of this report, which focuses solely on Cuyahoga County. The data

presented here suggest that bail decisions—including type of bond and bond amount—are

heavily driven by the name of the charge. Yet risk assessment research has made clear that the

name of the charge has, at best, a limited influence on the nature of the risk posed by each

defendant to present a danger to the public or to fail to appear in court. The Sentencing

Commission report recognized this when it recommended the elimination of bond schedules,

which only consider the charge, and their replacement with pretrial risk assessment tools.

The survey results and follow up interviews with Common Pleas and Municipal Court judges in

Cuyahoga County show that, for the most part, the judges are open to the use of risk assessment

tools, and would like opportunities to learn more about them. Moreover, at least some of the

municipal courts—including the largest, the Cleveland Municipal Court—are planning to use the

Public Safety Assessment, the pretrial risk assessment tool developed by the Arnold Foundation.

Currently, most of the municipal courts do not have the resources needed to conduct a risk

assessment. There have been discussions within Cuyahoga County for years about establishing a

central booking center, which, once implemented, could allow for all persons arrested in the

county for either a felony or a misdemeanor to be assessed for risk using a pretrial risk

assessment tool, with the results being made available to the judge at the initial bail hearing.

Many jurisdictions around the country that are implementing pretrial risk assessment tools are

also establishing supervision matrices, which help to match identified risk levels with

appropriate risk management strategies. Research has shown that defendants who are found to

be low-risk have very high rates of success on pretrial release, and these high rates cannot be

improved by imposing restrictive conditions of release.

2

The only result to expect when

imposing restrictive conditions of release on low-risk individuals is an increase in technical

violations.

3

Instead, the most appropriate response is to release these individuals on personal

bonds with no specific conditions, and no supervision other than to receive a reminder notice of

their court dates.

4

Other studies have found that higher-risk defendants who are released with supervision have

higher rates of success on pretrial release than similarly-situated unsupervised defendants. In

one study, controlling for other factors, higher-risk defendants who were released with

supervision were 33% less likely to fail to appear in court than their unsupervised counterparts.

5

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

1

Ad Hoc Committee on Bail and Pretrial Justice: Final Report and Recommendations, Ohio Sentencing

Commission, June 2017.

2

Marie VanNostrand and Gina Keebler, Pretrial Risk Assessment in the Federal Court, 73 FED. PROB.,

(2009).

3

Id.

4

Id.

5

Christopher Lowenkamp and Marie VanNostrand, Exploring the Impact of Supervision on Pretrial

Outcomes. (New York: Laura and John Arnold Foundation, 2013.)!

!

!

!

22!

As noted earlier, judges ranked education on risk management strategies high on their list of

priorities.

The Sentencing Commission had also recommended that judges prioritize the use of non-

financial release options. This recommendation also has relevance to Cuyahoga County. As

noted earlier, the analysis of the Cuyahoga County data showed that 28% of those with bonds of

$5000 or less–meaning they could have been released by paying as little as $500–never posted

their bonds and remained in jail until disposition of their cases. The research shows that there

are major consequences for low- and moderate-risk defendants who remain incarcerated

throughout the pretrial period, unable to post secured bonds. A study by the Arnold Foundation

found that, controlling for other factors, low-risk defendants who were held in jail throughout

the pretrial period due to their inability to post their bonds were 28% more likely to recidivate

within 24 months after adjudication than low-risk defendants who were released pretrial.

Medium-risk defendants detained throughout the pretrial period were 30% more likely to

recidivate within the following two years.

6

Moreover, looking at those who were released—whether by financial or non-financial means—

their average length of stay in jail before procuring release was 17 days. Looking exclusively at

those who were released on personal bonds, whether at their initial bond hearing in municipal

court or later in the process, 38% spent at least one week in jail. Again, the research shows the

implications of such findings. The same study by the Arnold Foundation found that, when

controlling for other factors, those who had scored as low-risk on the empirically-derived

pretrial risk assessment tool and who were held in jail for just 2-3 days after arrest were 39%

more likely to be arrested on a new charge while the first case was pending than those who were

released on the first day, and 22% more likely to fail to appear. Low-risk individuals who were

held 4-7 days were 50% more likely to be arrested, and 22% more likely to fail to appear; those

held 8-14 days were 56% more likely to have a new charge and 41% more likely to have a failure

to appear. The same patterns held for medium-risk persons who were in jail for short periods.

7

Such results might be palatable if secured money bonds were found to be more effective than

non-financial bonds in terms of public safety and court appearance. Yet the one study that

controlled for risk levels in comparing outcomes of those released by secured versus unsecured

bonds found that that, across all risk levels, there were no statistically significant differences in

outcomes (i.e., court appearance and public safety rates) between defendants released without

having to post financial bonds and those released after posting such a bond. The study also

looked at the jail bed usage of defendants on the two types of bonds. Defendants who did not

have to post financial bonds before being released spent far less time in jail than defendants who

had to post. This is not surprising, since defendants with secured bonds must find the money to

satisfy the bond or make arrangements with a bail bonding company in order to obtain release.

Also, 39% of defendants with secured bonds were never able to raise the money and spent the

entire pretrial period in jail. In summary, the study found that unsecured bonds, which do not

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

6

Christopher Lowenkamp, Marie VanNostrand, and Alex Holsinger, The Hidden Costs of Pretrial

Detention, Laura and John Arnold Foundation (2013),

7

Christopher Lowenkamp, Marie VanNostrand, and Alex Holsinger, The Hidden Costs of Pretrial

Detention, Laura and John Arnold Foundation (2013), [hereinafter Hidden Costs].!

!

!

!

23!

require defendants to post money before being released, offer the same public safety and court

appearance benefits as secured bonds, but do so with substantially less use of jail bed space.

8

The legal issues raised by the use of secured bonds are now receiving attention in the courts. In

the past few years, a number of federal and state courts have imposed strict limitations on the

use of secured bonds. For example, in Harris County, Texas, a U.S. District Court ruled that local

judges must release most misdemeanor defendants on personal or unsecured bonds at first

appearance. (Odonnell v. Harris County, U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas,

No. H-16-1414, 4/28/17). In addition, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court has ruled that

judges can only impose secured financial bonds to address appearance concerns, not safety, and

that if setting a secured bond, the court must first assess the person’s ability to make the bond.

(Brangan v. Commonwealth, Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, SJC-12232, 8/25/17.)

One issue that arose in interviews with judges relating to the use of secured financial bonds is

that the 10% and full cash bonds may be used as a way to assure the payment of fines and fees in

municipal court cases. If the person is ultimately convicted and makes all court appearances, the

money for fines and fees can be subtracted from the bond before it is returned. The purpose of

bail under the law is clear–to provide the opportunity for release of an individual pending trial

with reasonable assurance of public safety and court appearance. Any other purpose of bail

conditions–whether they be financial or non-financial–is unlawful. Given the litigation taking

place around the country regarding bail setting practices, judges should take great care to

articulate the reasons for their decisions, especially when setting secured financial bonds.

Recommendations

Based upon the findings of this report, the Pretrial Justice Institute makes the following

recommendations for the Cuyahoga County court systems:

1. Conduct a training on the fundamentals of pretrial justice for the judges of the

Court of Common Pleas and of the municipal courts.

The survey and follow-up interviews with the judges found that most of the judges felt the need

for training on the basics of bail. The training should cover the use of risk assessment tools,

including how they are developed, what they consist of, what they show, and how they can be

used to help inform judicial discretion in making bail decisions. The training should also include

effective pretrial supervision strategies.

The implementation phase of the judicial training can be approached in multiple ways. We

recommend the Task Force evaluate its resources and determine the best course of action to

provide the judicial education. State-based organizations such as the ACLU-OH could

potentially provide this training, with the assistance and guidance, if appropriate and needed,

from PJI. Pretrial Justice Institute is a fee-based provider who can design and implement

judicial training. There are other providers such as the National Center for State Courts, State

Justice Institute, and private consultant groups who often provide this training for a fee. We

encourage the Task Force to evaluate funding/grants that may exist and can offset the expenses

associated with this recommended action.

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

8

Michael R. Jones, Unsecured Bonds: The “As Effective” and “Most Efficient” Pretrial Release Option

(2013), [hereinafter Unsecured Bonds]. This study was conducted from data on 1,970 defendants from 10

The different counties in Colorado in 2011.

!

!

!

24!

2. Conduct a one-to-tw0-day summit of the judiciary in Cuyahoga County to

identify a clear vision statement pertaining to pretrial practices within the

county.

Following the training of all judges, the combined Court of Common Pleas and Municipal Court

benches should meet to establish a vision for what pretrial justice should look like in Cuyahoga

County and its municipalities, and the steps needed to implement that vision, beginning with

pilot test sites.

In February 2017, the American Judges Association passed a resolution that may provide a

useful framework for such a vision statement. In that resolution, the association called for court

systems to:

1. promote and support the adoption of evidence-based risk assessment and management

in making the bail determination;

2. eliminate practices that cause defendants to remain incarcerated solely because they

cannot afford to pay for their release;

3. call for the elimination of commercially secured bonds at any time during the pretrial

phase;

4. call for the shift from secured to unsecured money bond at any time during the pretrial

phase;

5. promote and support the practice of least restrictive graduated conditions of release

which can be adjusted per the compliance or non-compliance of the individual;

6. call for the ability of every judge to conduct a preventive detention hearing with full due

process protections so that detention-eligible defendants are detained under accepted

evidentiary standards;

7. promote judicial training and development that addresses how best practices and

identifying sources of implicit bias can reduce racial and gender disparities.

3. Pilot test 2-4 projects in both the Municipal and Common Pleas Court

introducing research- and evidenced-based practices in pretrial improvements.

The components of the pilot sites would include: the presence and active participation of

prosecution and defense at the initial bail hearing or any subsequent hearing in which bail is

considered; the use of an empirically derived pretrial risk assessment tool in every criminal case

appearing before a judge for an initial bail hearing, or the availability of the risk assessment

results from the initial bail hearing at any subsequent hearings where bail is considered; the use

of a supervision matrix that allows the court to match the most appropriate supervision level to

the identified risks of each individual; and the availability of supervision resources.

4. Actively and consistently communicate the plans, progress, and outcomes of

the pilot sites to the entire judiciary, as well as other key stakeholders, such as

prosecutors, defenders, law enforcement, victim advocates, and the community

at large.

While judges are key to any effective bail reform efforts, they cannot change the system by

themselves. All the key stakeholders need to be informed and involved in the efforts. The judicial

leadership has already recognized this, including representatives from the stakeholder groups

on the committees that are currently looking into bail reform. These committees should remain

in place, or a new one established, to hear and consider the results from the pilots.

!

!

!

25!

5. Based on the results of the pilot sites, plan and implement an expansion of new

practices system-wide.

The Cuyahoga County justice system has been considering for a number of years the

establishment of a central booking facility, but have yet to reach a final decision. Such a facility

could be very helpful in assuring that risk assessments are completed in every criminal case. The

pilot sites should shed light on the opportunities and challenges that exist in doing a risk

assessment in each case. And as long as the pilot sites are representative of all the courts in the

county, their experiences should inform discussions about costs and resources needed to

provide effective supervision services.

6. Conduct a thorough analysis of the impacts of pretrial release decision making

by race and ethnicity.

Evaluating the jail population through the lens of race and ethnicity requires additional data to

determine if release decisions have disparate impacts on release, release by type, length of time

to release, and any bail or bond revocation. There are preliminary indicators, based upon the

population demographics in the Cuyahoga County jail, as compared to the Municipal satellites,

that suggest a further rigorous evaluation is needed in this area.

!

!

!

26!

APPENDIX A:

List of Data Elements Requested for Jail Population Analysis

Jail population data trends

For the years 2012 through 2016:

• The annual number of bookings (admissions)

• The average daily population of inmates in the facility, over the course of the year

Jail snapshot profile

All persons released from the jail on (a recent day TBD):

• Person’s name or other unique identifying number

• Person’s booking number

• Person’s date of birth or age

• Person’s sex

• Person’s race (White, Black, Asian, Other)

• Person’s ethnicity (Hispanic or Non-Hispanic)

• Person’s employment status (No, Part-time, Full-time)

• Person’s city of residence

• Person’s state of residence

• Person’s ZIP Code

• Date booked in

• Time booked in

• Arresting agency

• English description of most serious charge

• Offense class (Felony, Misdemeanor, Traffic, Municipal, etc.) of most serious charge

• English description of second most serious charge

• Offense class (Felony, Misdemeanor, Traffic, Municipal, etc.) of second most serious

charge

• Total number of charges

• Court of jurisdiction for most serious charge

• Docket number for most serious charge

• Legal Status (Pretrial, Convicted, Sentenced, Contract, Hold, Probation violation, etc.)

• Bond condition type (Cash only, Cash or surety, Recognizance)

• Total bond amount set (measured in dollars, if any)

• Flag for bondable on a charge (Yes/No)

• Person’s pretrial risk category (Higher, Medium, Lower Risk)

• Reason for release (i.e., bond posted, case dismissed, sentence completed)

• Released to where (i.e., the community, state prison system, another jail)

• Flag for Sentenced status (Yes/No)

• Sentence start date

• Flag for domestic violence (Yes/No)

• Flag for mental health concern (Yes/No)

• Flag for medical (physical health) concern (Yes/No)

• Flag for noncompliance (e.g., probation, parole) holds (Yes/No)

• Flag for homeless (Yes/No)

!

!

!

27!

APPENDIX B:

Misdemeanor and Felony Filings Tables

Table B-1

Misdemeanor Filings in Municipal Courts – 2012 to 2015

Municipal

Court

2012

2013

2014

2015

Bedford

2469

2354

2379

2132

Berea

1900

1799

2012

2087

Cleveland

30841

28,790

25,464

17,977

Cleveland

Heights

2581

2365

2070

1855

Cleveland

Housing

5369

4810

5479

4795

East Cleveland

1544

1634

1103

1010

Euclid

1454

1361

1301

1076

Garfield

Heights

3045

2886

2875

2318

Lakewood

2246

2111

2260

1920

Lyndhurst

941

1000

1091

987

Parma

6268

5646

5385

4575

Rocky River

2906

2392

2197

2149

Shaker Heights

1290

1202

1143

989

South Euclid

537

539

783

786

Total

63,391

58,889

55,542

44,656

!

!

!

28!

Table B-2

Felony Filings in Municipal Court - 2012 to 2015

Municipal

Court

2012

2013

2014

2015

Bedford

3

197

339

335

Berea

4

166

305

277

Cleveland

5,604

4864

4661

4078

Cleveland

Heights

104

205

333

239

Cleveland

Housing

0

0

0

0

East Cleveland

0

139

163

160

Euclid

187

269

358

381

Garfield

Heights

416

358

332

320

Lakewood

91

192

288

272

Lyndhurst

0

110

238

198

Parma

309

575

839

853

Rocky River

167

244

359

430

Shaker Heights

27

82

163

169

South Euclid

34

42

71

60

Total

6946

7443

8449

7772

!

!

!

29!

APPENDIX C:

Judicial Survey Results

Very!well!

informed!

Well!informed! Somewhat!well!

informed!

Not!well!

informed!

N/A!

0.00%!

10.00%!

20.00%!

30.00%!

40.00%!

50.00%!

How informed do you feel about the

strengths and weaknesses of the bail

system in your jurisdiction, and about

ways that it might be improved?

Very!valuable! Somewhat!

valuable!

Neutral! Not!very!valuable! No!value!at!all!

0.00%!

10.00%!

20.00%!

30.00%!

40.00%!

50.00%!

60.00%!

Do you see value in the Criminal Justice

Committee examining the pretrial process

in Cuyahoga County and its

municipalities?

!

!

!

30!

1. Legal and historical foundations of pretrial justice

2. The national landscape–what is happening nationally to enhance pretrial justice

3. Actuarial risk assessment tools

4. Research informed pretrial risk assessment strategies

5. Addressing racial and ethnic disparities in the pretrial process

6. The latest pretrial research on the impacts of detention

7. Engaging stakeholders

Very!valuable! Somewhat!

valuable!

Neutral! Not!very!valuable! No!value!at!all!

0.00%!

10.00%!

20.00%!

30.00%!

40.00%!

50.00%!

60.00%!

70.00%!

Do you see value in judicial-specific

education to understand the possible

actions to improve the bail system being

examined by the Criminal Justice

Committee?

1! 2! 3! 4! 5! 6! 7! 8! 9!

0.00%!

10.00%!

20.00%!

30.00%!

40.00%!

50.00%!

60.00%!

70.00%!

80.00%!

90.00%!

What topics for judicial education and

training would be helpful and meaningful

to you? Check ALL that apply.

!

!

!

31!

8. None

9. Other

Very!familiar! Somewhat!

familiar!

Not!very!familiar! Not!familiar!at!all! N/A!

0.00%!

5.00%!

10.00%!

15.00%!

20.00%!

25.00%!

30.00%!

35.00%!

40.00%!

45.00%!

How familiar are you with Actuarial

Pretrial Risk Assessment tools?

An!important!

addiGonal!tool!for!

the!judicial!officer!

in!the!bail!

decision!

They!sound!good,!

but!I!need!to!

know!more!

I'm!not!sure!they!

work!and!they!

might!create!

more!problems!

They!are!not!

useful!to!the!

judicial!officer!in!

the!bail!decision!

N/A!

0.00%!

5.00%!

10.00%!

15.00%!

20.00%!

25.00%!

30.00%!

35.00%!

40.00%!

45.00%!

50.00%!

How do you view Actuarial Risk

Assessments tools? Select most

appropriate.

!

!

!

32!

1. Public safety

2. Court appearance

3. Maximizing release on least restrictive conditions

4. Reducing the jail population in a responsible manner

5. Reducing racial, ethnic and economic disparities

Very!familiar! Somewhat!

familiar!

Not!very!familiar! Not!familiar!at!all! N/A!

0.00%!

5.00%!

10.00%!

15.00%!

20.00%!

25.00%!

30.00%!

35.00%!

40.00%!

45.00%!

50.00%!

How familiar are you with supervision

matrices that match a charge/risk profile

with the appropriate supervision level?

1! 2! 3! 4! 5! 6! 7!

0!

1!

2!

3!

4!

5!

6!

7!

8!

Recognizing that every bail decision is different, rank

in order of importance what you generally consider

when making a decision.

!

!

!

33!

6. Identifying people who have specific mental health or substance abuse needs who ban be

diverted

7. Case processing–improving the timeliness and effectiveness of the movement of cases