Medication Safety in

Polypharmacy

Technical Report

Medication Safety in

Polypharmacy

Technical Report

WHO/UHC/SDS/2019.11

© World Health Organization 2019

Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO

licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo).

Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the

work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses

any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you

must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you

should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation:

“

This translation was not created by the World Health

Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall

be the binding and authentic edition”.

Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the

World Intellectual Property Organization (http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/mediation/rules).

Suggested citation. Medication Safety in Polypharmacy. Geneva: World Health Organization;

2019 (WHO/UHC/SDS/2019.11). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) data. CIP data are available at http://apps.who.int/iris.

Sales, rights and licensing. To purchase WHO publications, see http://apps.who.int/bookorders. To submit requests for

commercial use and queries on rights and licensing, see http://www.who.int/about/licensing.

Third-party materials. If you wish to reuse material from this work that is attributed to a third party, such as tables, figures

or images, it is your responsibility to determine whether permission is needed for that reuse and to obtain permission from

the copyright holder. The risk of claims resulting from infringement of any third-party-owned component in the work rests

solely with the user.

General disclaimers. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the

expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or

of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted and dashed lines on maps represent

approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement.

The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or

recommended by WHO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted,

the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters.

All reasonable precautions have been taken by WHO to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the

published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the

interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall WHO be liable for damages arising from its use.

Designed by CommonSense, Greece

Printed by the WHO Document Production Services, Geneva, Switzerland

3

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

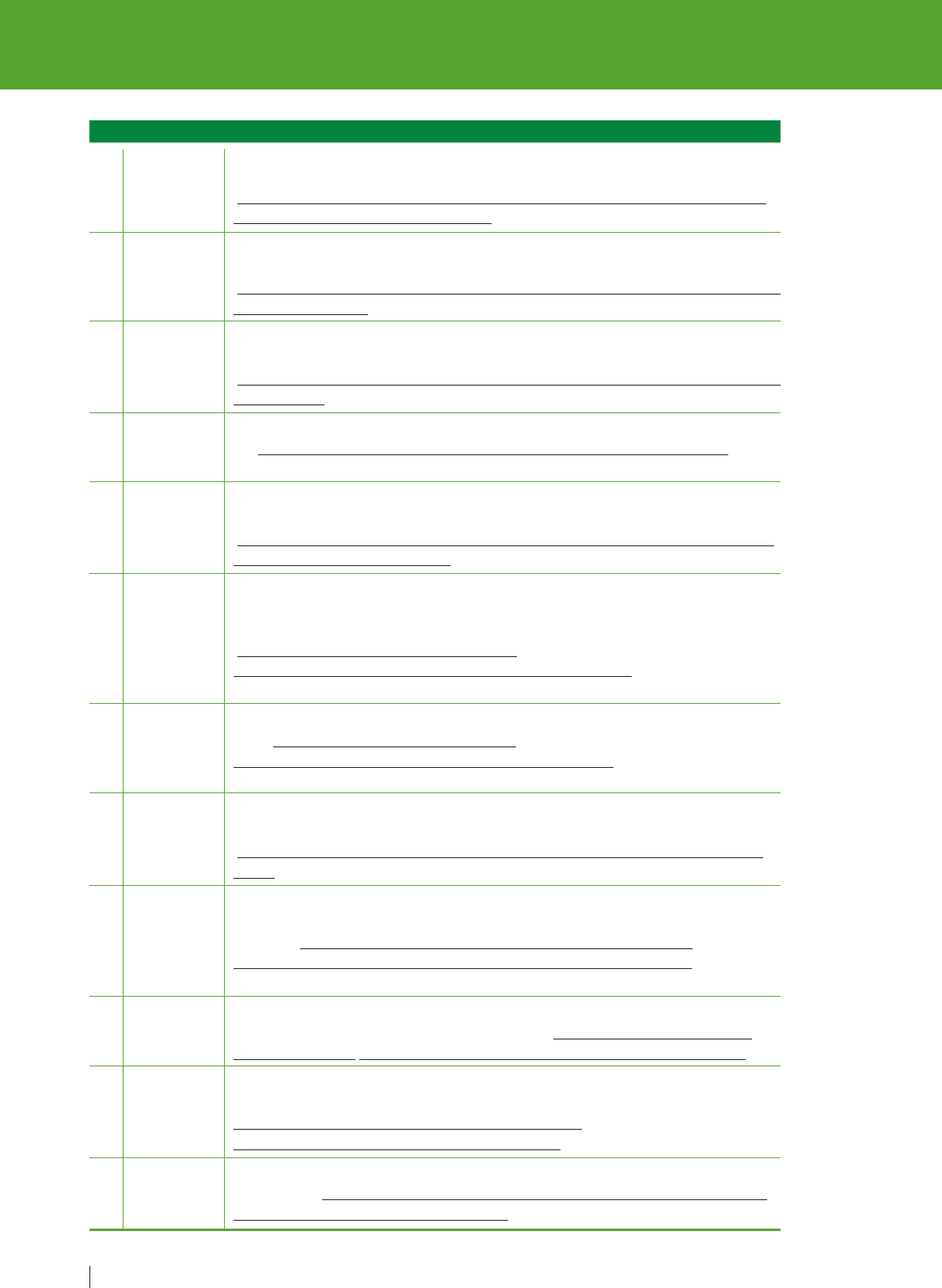

Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................... 4

Preface .............................................................................................................................................. 5

Executive summary: medication safety in polypharmacy ............................................................ 10

1. Introduction.................................................................................................................................. 11

1.1 Polypharmacy .......................................................................................................................... 11

1.2 Prevalence of polypharmacy ..................................................................................................12

1.3 Economic impact of polypharmacy ........................................................................................ 13

1.4 Other factors influencing appropriate polypharmacy.............................................................. 14

2. Medication safety in polypharmacy .......................................................................................... 15

2.1 Medication-related harm in polypharmacy.............................................................................. 15

2.2 Medication review in polypharmacy ...................................................................................... 16

3. Implementing polypharmacy initiatives .................................................................................... 20

3.1 Implementing sustainable programmes to address polypharmacy........................................ 20

3.2 Programmes on appropriate polypharmacy .......................................................................... 21

4. Health systems approach to polypharmacy.............................................................................. 23

4.1 Patients and the public............................................................................................................ 24

4.2 Health care professionals ...................................................................................................... 25

4.3 Medicines................................................................................................................................ 25

4.4 Systems and practices of medication .................................................................................... 26

4.5 Monitoring and evaluation ...................................................................................................... 27

5. Points of consideration for countries ........................................................................................ 29

References ...................................................................................................................................... 30

Annexes .......................................................................................................................................... 38

Annex 1. Glossary ............................................................................................................................ 38

Glossary references .......................................................................................................... 41

Annex 2. Global prevalence of polypharmacy ................................................................................ 43

Annex 3. Internationally available guidance on appropriate polypharmacy management .............. 47

Annex 4. Case studies .................................................................................................................... 49

Annex 5. List of contributors ............................................................................................................ 59

Contents

ACE angiotensin-converting enzyme

ADR adverse drug reaction

ARB angiotensin II receptor blocker

BP blood pressure

COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate

NNH number needed to harm

NNT number needed to treat

NSAID non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

OTC over-the-counter

PESTEL political, economic, social, technological, environmental and legal

PIM potentially inappropriate medication

RLS reporting and learning systems

SWOT strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats

UHC universal health coverage

WHO World Health Organization

4

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

Abbreviations

5

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

Health care interventions are intended to

benefit patients, but they can also cause

harm. The complex combination of processes,

technologies and human interactions that

constitutes the modern health care delivery

system can bring significant benefits.

However, it also involves an inevitable risk of

patient harm that can – and too often does –

result in actual harm. A weak safety and

quality culture, flawed processes of care

and disinterested leadership teams weaken

the ability of health care systems and

organizations to ensure the provision of safe

health care. Every year, a significant number

of patients are harmed or die because of

unsafe health care, resulting in a high public

health burden worldwide.

Most of this harm is preventable. Adverse

events are now estimated to be the 14th leading

cause of morbidity and mortality in the world,

putting patient harm in the same league as

tuberculosis and malaria

(1)

. The most important

challenge in the field of patient safety (see

Annex 1) is how to prevent harm, particularly

avoidable harm, to patients during their care.

Patient safety is one of the most important

components of health care delivery which is

essential to achieve universal health coverage

(UHC), and moving towards the UN Sustainable

Development Goals (SDGs). Extending health

care coverage must mean extending safe care,

as unsafe care increase costs, reduces

efficiency, and directly compromises health

outcomes and patient perceptions. It is

estimated that over half of all medicines are

Preface

prescribed, dispensed or sold inappropriately,

with many of these leading to preventable harm

(2)

. Given that medicines are the most common

therapeutic intervention, ensuring safe

medication use and having the processes in

place to improve medication safety (see Annex

1) should be considered of central importance

to countries working towards achieving UHC.

The Global Patient Safety Challenges of the

World Health Organization (WHO) shine a light

on a particular patient safety issue that poses a

significant risk to health. Front-line interventions

are then developed and, through partnership

with Member States, are disseminated and

implemented in countries. Each Challenge has

so far focused on an area that represents a

major and significant risk to patient health and

safety (see Annex 1). In 2005, the Organization,

working in partnership with the (then) World

Alliance for Patient Safety, launched the first

Global Patient Safety Challenge:

Clean Care Is

Safer Care (3)

, followed a few years later by the

second Challenge:

Safe Surgery Saves Lives

(4)

. Both Challenges aimed to gain worldwide

commitment and spark action to reduce health

care-associated infection and the risks

associated with surgery, respectively.

Recognizing the scale of avoidable harm

linked with unsafe medication practices and

medication errors, WHO launched its third

Global Patient Safety Challenge:

Medication

Without Harm

in March 2017, with the goal

of reducing severe, avoidable medication-

related harm by 50% over the next five years,

globally

(5)

.

6

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

This Challenge follows the same philosophy as

the previous Challenges, namely that errors are

not inevitable, but are very often provoked by

weak health systems, and so the challenge is to

reduce their frequency and impact by tackling

some of the inherent weaknesses in the system.

As part of the Challenge, WHO has asked

countries and key stakeholders to prioritize

three areas for strong commitment, early action

and effective management to protect patients

from harm while maximizing the benefit from

medication, namely:

•

medication safety in high-risk situations

•

medication safety in polypharmacy

•

medication safety in transitions of care.

Consider the following case scenario

describing a medication error (see Annex 1)

involving these three areas.

Medication error: case scenario

Mrs Poly, a 65-year-old woman, came to the outpatient clinic complaining of abdominal pain and

dark stools. She had a heart attack five years ago. At her previous visit three weeks ago she was

complaining of muscle pain, which she developed while working on her farm. She was given a

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), diclofenac. Her other medications included aspirin,

and three medicines for her heart condition (simvastatin, a medicine to reduce her serum

cholesterol; enalapril, an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor; and atenolol, a beta

blocker). She was admitted to hospital as she developed symptoms of blood loss (such as

fatigue and dark stools). She was provisionally diagnosed as having a bleeding peptic ulcer due

to her NSAID, and her doctor discontinued diclofenac and prescribed omeprazole, a proton

pump inhibitor. Following her discharge, her son collected her prescribed medicines from the

pharmacy. Among the medicines, he noticed that omeprazole had been started and that all her

previous medicines had been dispensed, including the NSAID. As his mother was slightly

confused and could not remember exactly what the doctor had said, the son advised his mother

that she should take all the medications that had been supplied. After a week, her abdominal

pain continued and her son took her to the hospital. The clinic confirmed that the NSAID, which

should have been discontinued (deprescribed), had been continued by mistake. This time Mrs

Poly was given a medication list when she left the hospital which included all the medications

she needed to take and was advised about which medications had been discontinued and why.

In this scenario the key steps that should have

been followed to ensure medication safety

in the inpatient setting include:

1. Appropriate prescribing and risk

assessment

Medication safety should start with appropriate

prescribing and a thorough risk–benefit

analysis of each medicine is often the first step.

In this case scenario, prophylactic aspirin

and NSAID without a gastroprotective agent

left Mrs Poly at an increased risk of

gastrointestinal bleeding. NSAIDs can also

increase the risk of cardiovascular events,

which is of particular concern, as she had had

a myocardial infarction (heart attack) five years

ago. This is a good example of a high-risk

situation requiring health care professionals

to prescribe responsibly after analysing

the risks and benefits.

2. Medication review

A comprehensive medication review (see

Annex 1) is a multidisciplinary activity whereby

the risks and benefits of each medicine are

considered with the patient and decisions

made about future therapy. It optimizes the use

of medicines for each individual patient.

Multiple morbidities usually require treatment

with multiple medications, a situation described

as polypharmacy (see Annex 1). Polypharmacy

can put the patient at risk of adverse drug

events (see Annex 1) and drug interactions

when not used appropriately. In this case,

there should have been a review of

medications, particularly as Mrs Poly was

prescribed aspirin and diclofenac together.

The haemodynamic changes following blood

loss should have also prompted temporary

stopping the ACE inhibitor before restarting once

the episode of blood loss has been resolved.

7

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

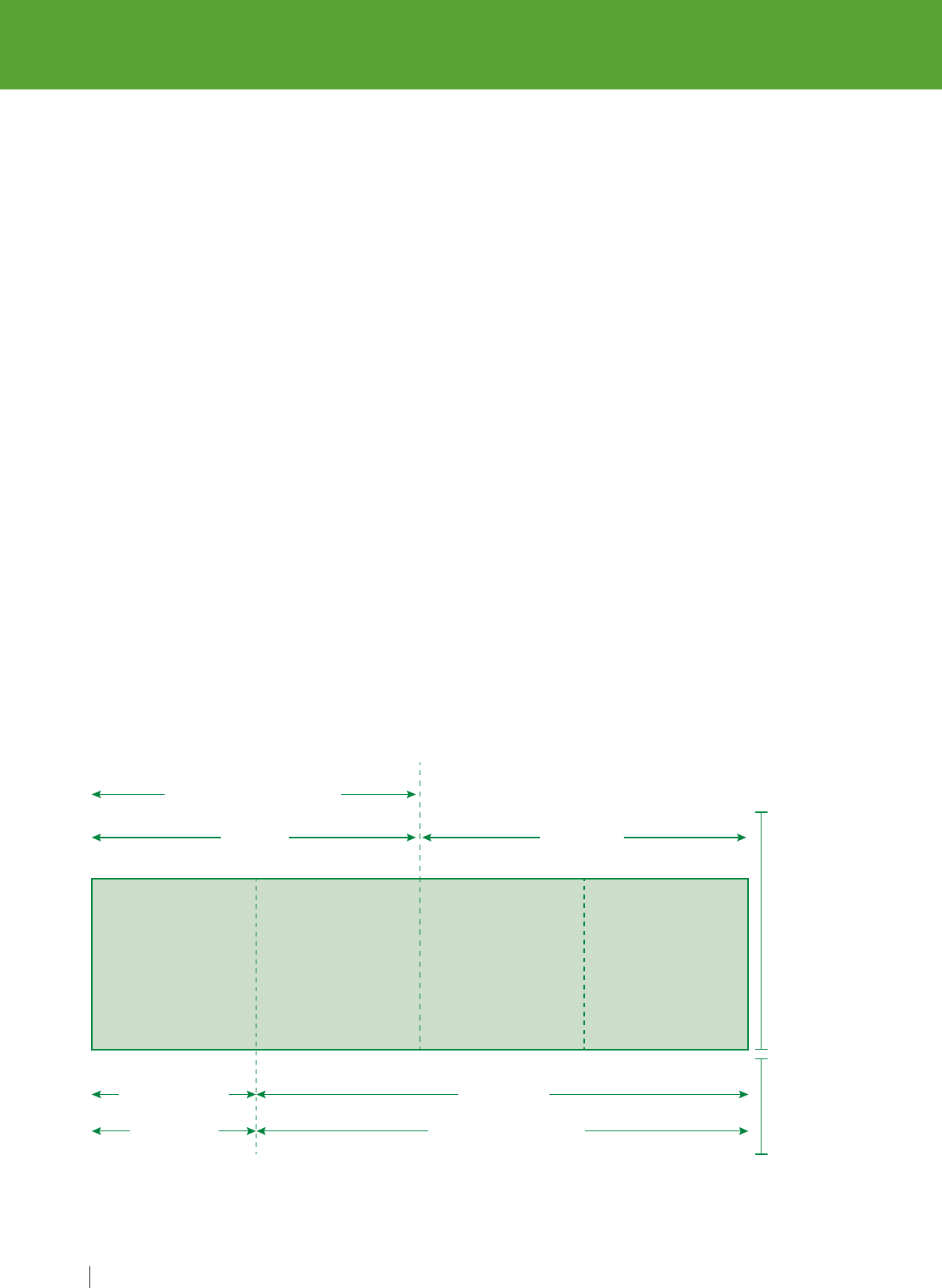

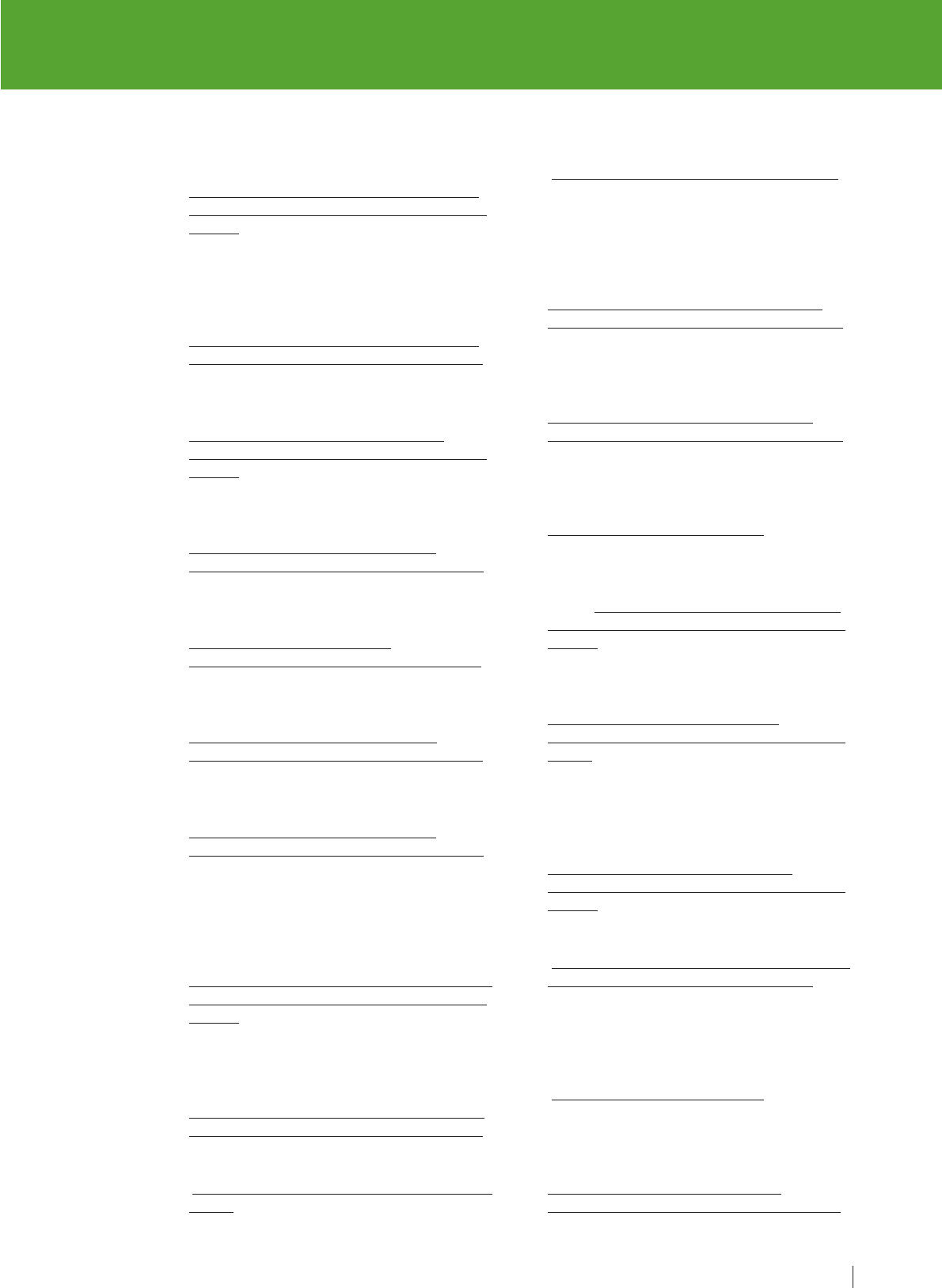

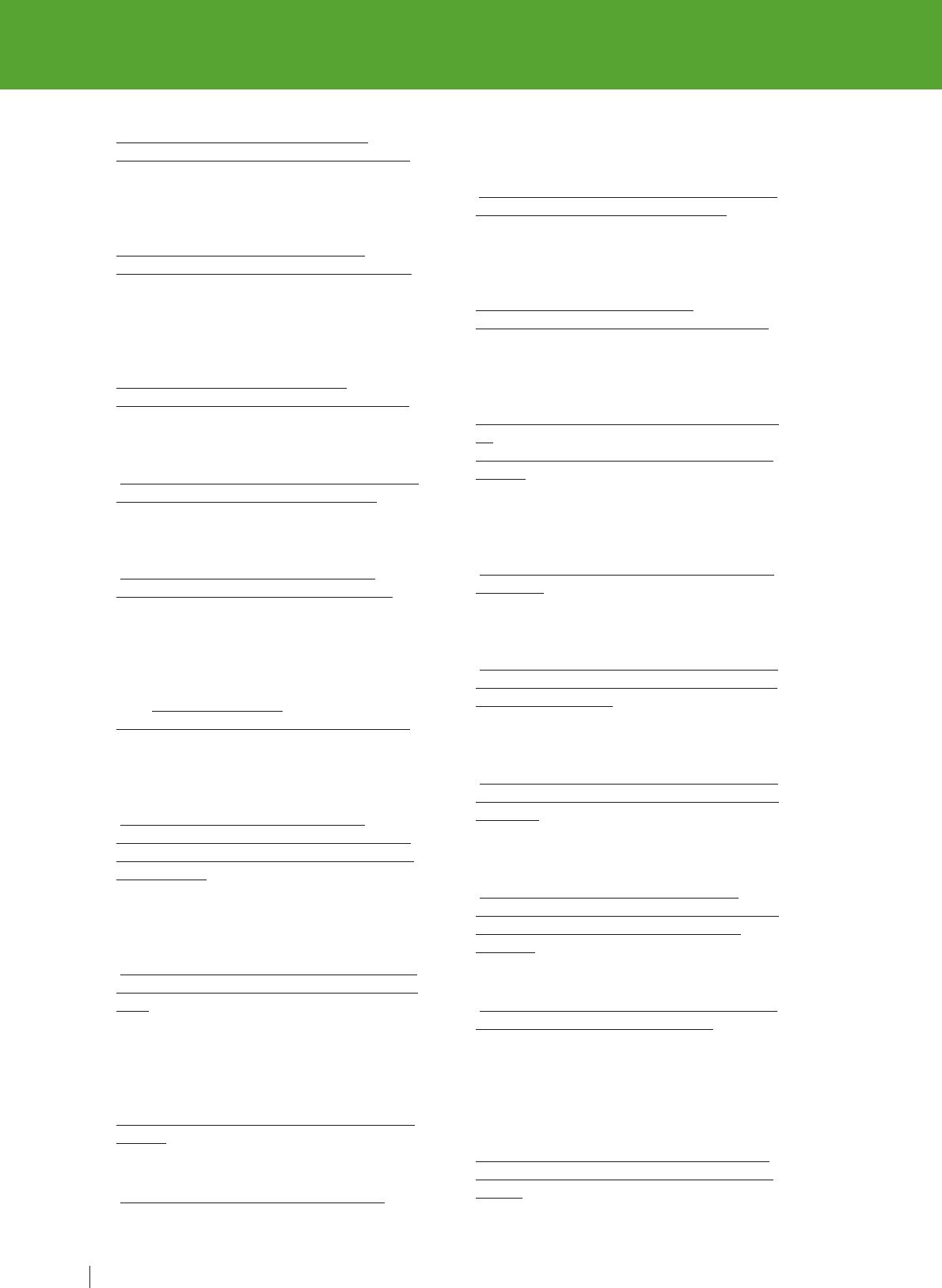

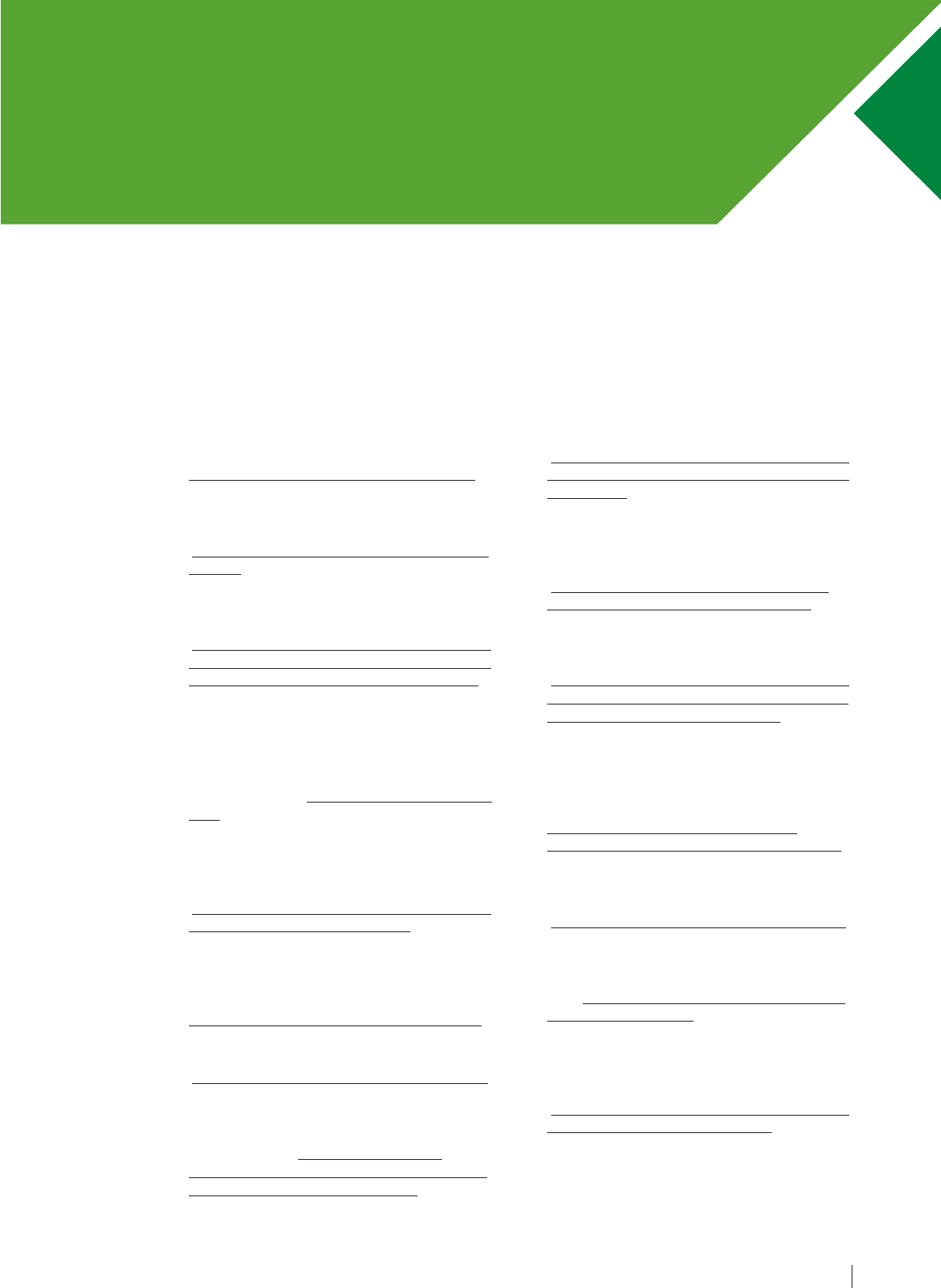

The events leading to the error in this scenario and how these could have been prevented are

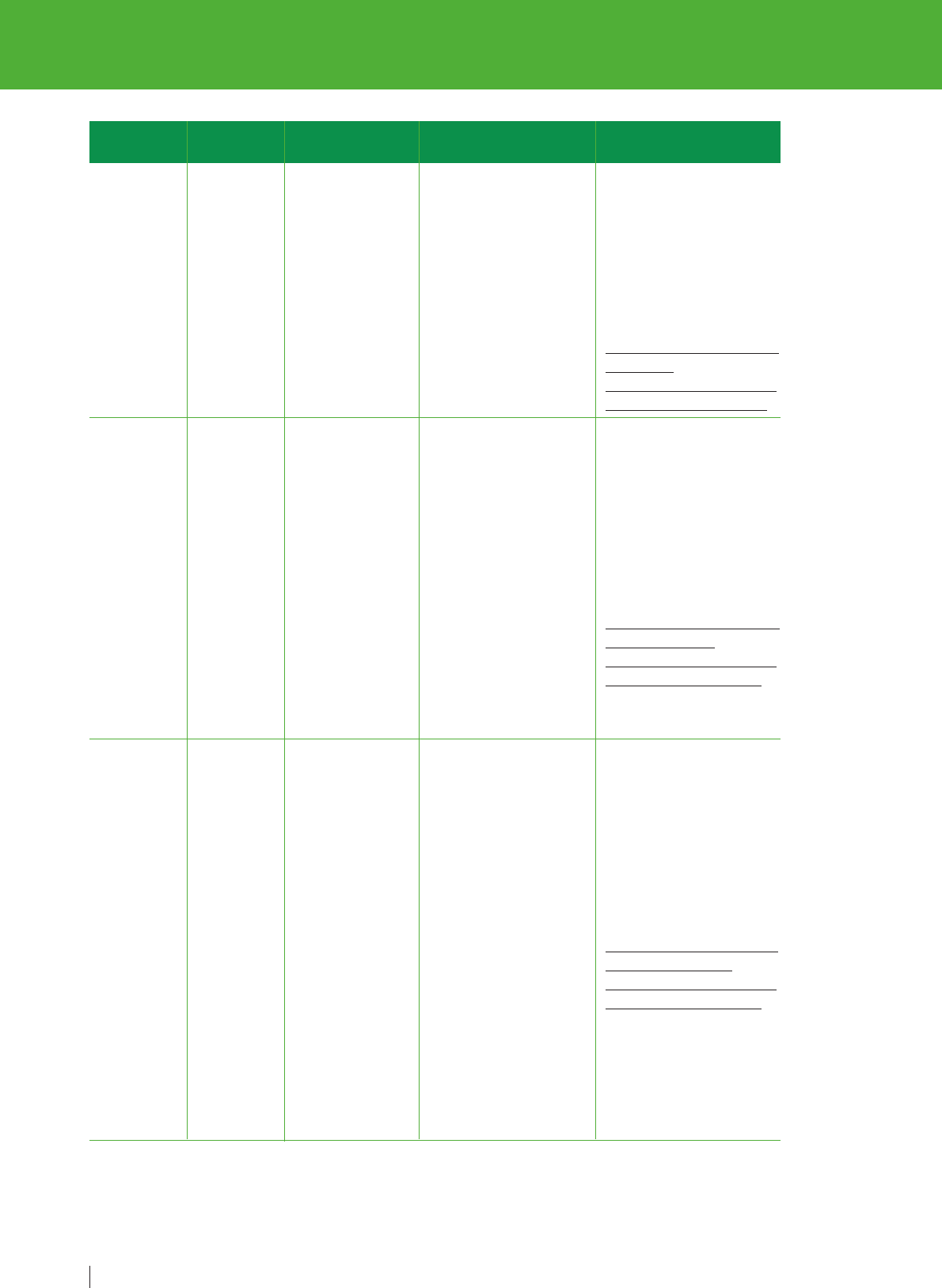

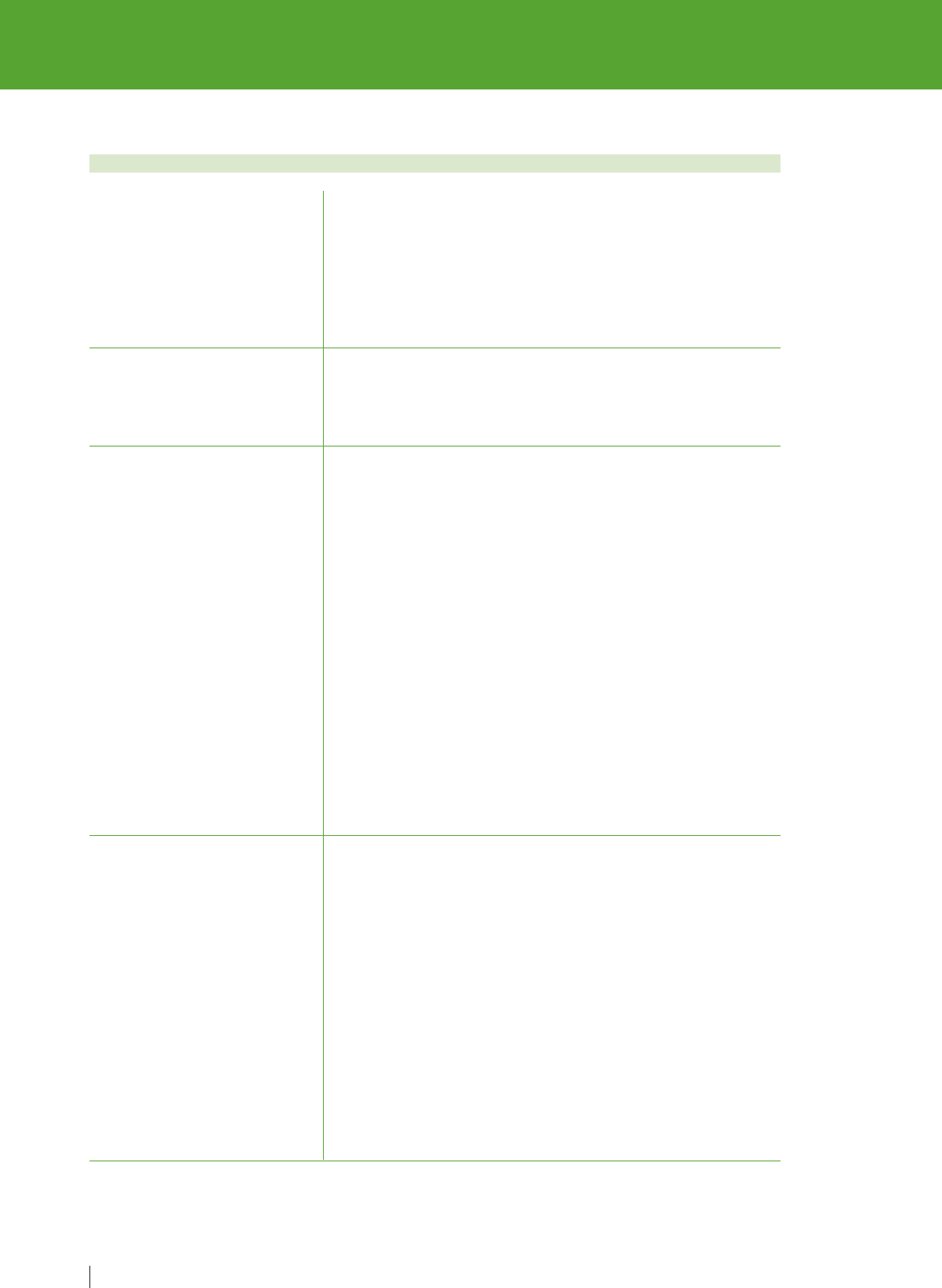

reflected in Figure 1, and the text below.

Figure 1. Key steps for ensuring medication safety

1.

Appropriate

prescribing

and risk

assessment

Benefit

Risks

5.

Medication

reconciliation

at care transitions

2.

Medication

review

3.

Dispensing,

preparation and

administration

4.

Communication

and patient engagement

3. Dispensing, preparation and

administration

This is a high-risk situation as the medication

(diclofenac) has the potential to cause harm.

However, this medication was continued after

discharge when the patient transitioned from

hospital to home. Dispensing this medicine and its

administration caused serious harm to Mrs Poly.

Dispensing this medicine and its administration

caused significant harm to Mrs Poly.

4. Communication and patient engagement

Proper communication between health care

providers and patients, and amongst health

care providers, is important in preventing

errors. When Mrs Poly was severely ill due to

gastric bleeding, the NSAID was discontinued.

However, the decision to discontinue the

medicine was not adequately communicated

either to the other health care professionals

(including the nurse or the pharmacist) or to

Mrs Poly. Initial presenting symptoms due to

adverse effects could have been identified

earlier if she had been warned about the risks.

5. Medication reconciliation at care

transitions

Medication reconciliation is the formal process

in which health care professionals partner

with patients to ensure accurate and complete

medication information transfer at interfaces

of care. Diclofenac, the NSAID that can cause

gastrointestinal bleeding and increase the risk

of cardiotoxicity and had led to this hospital

admission, was discontinued, and this

information should have been communicated

at the time of discharge (in the form of a

medication list or patient-held medication

record). This would have helped her and her

caregivers in determining what the newly added

and discontinued medications needed to be.

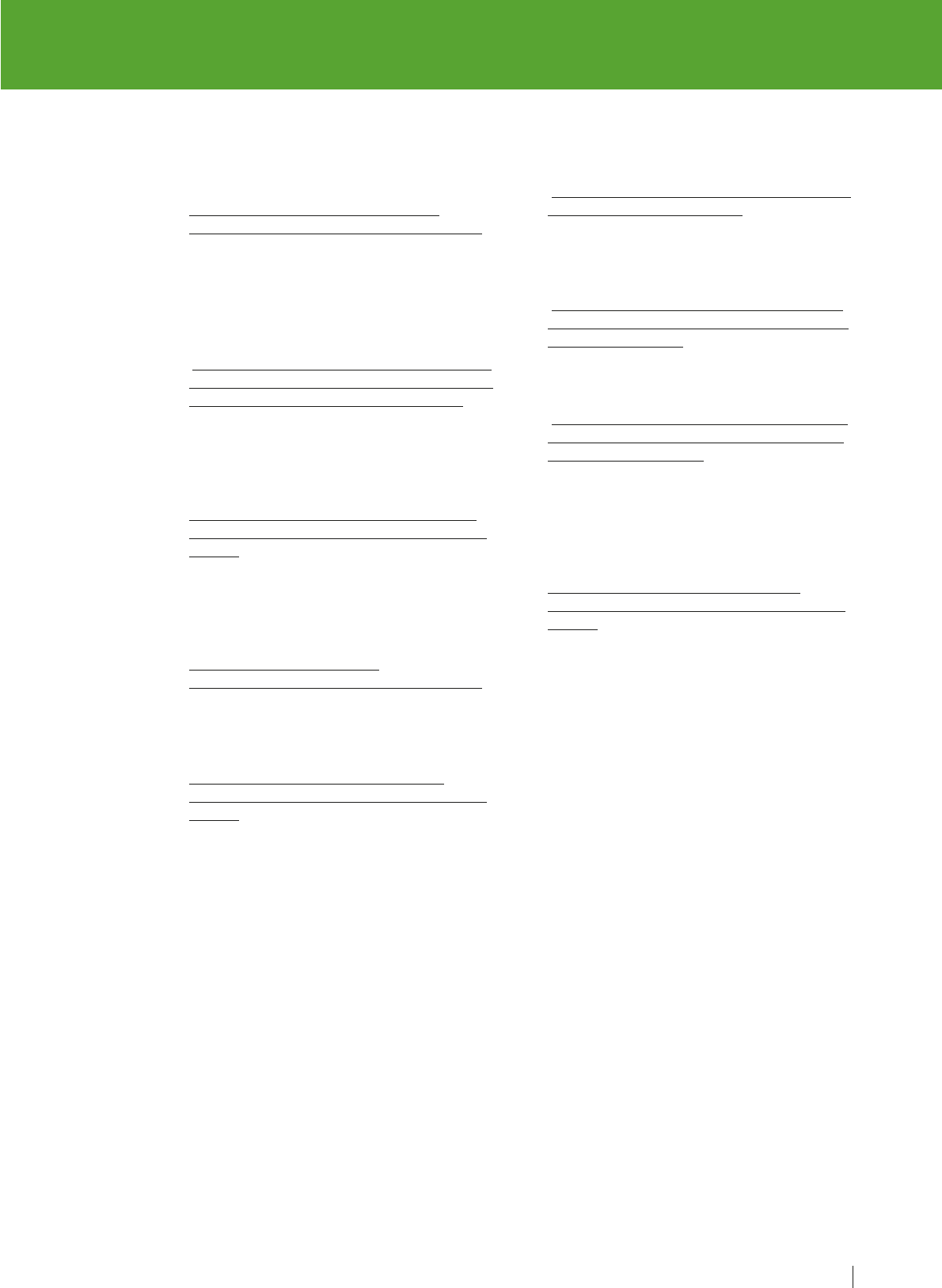

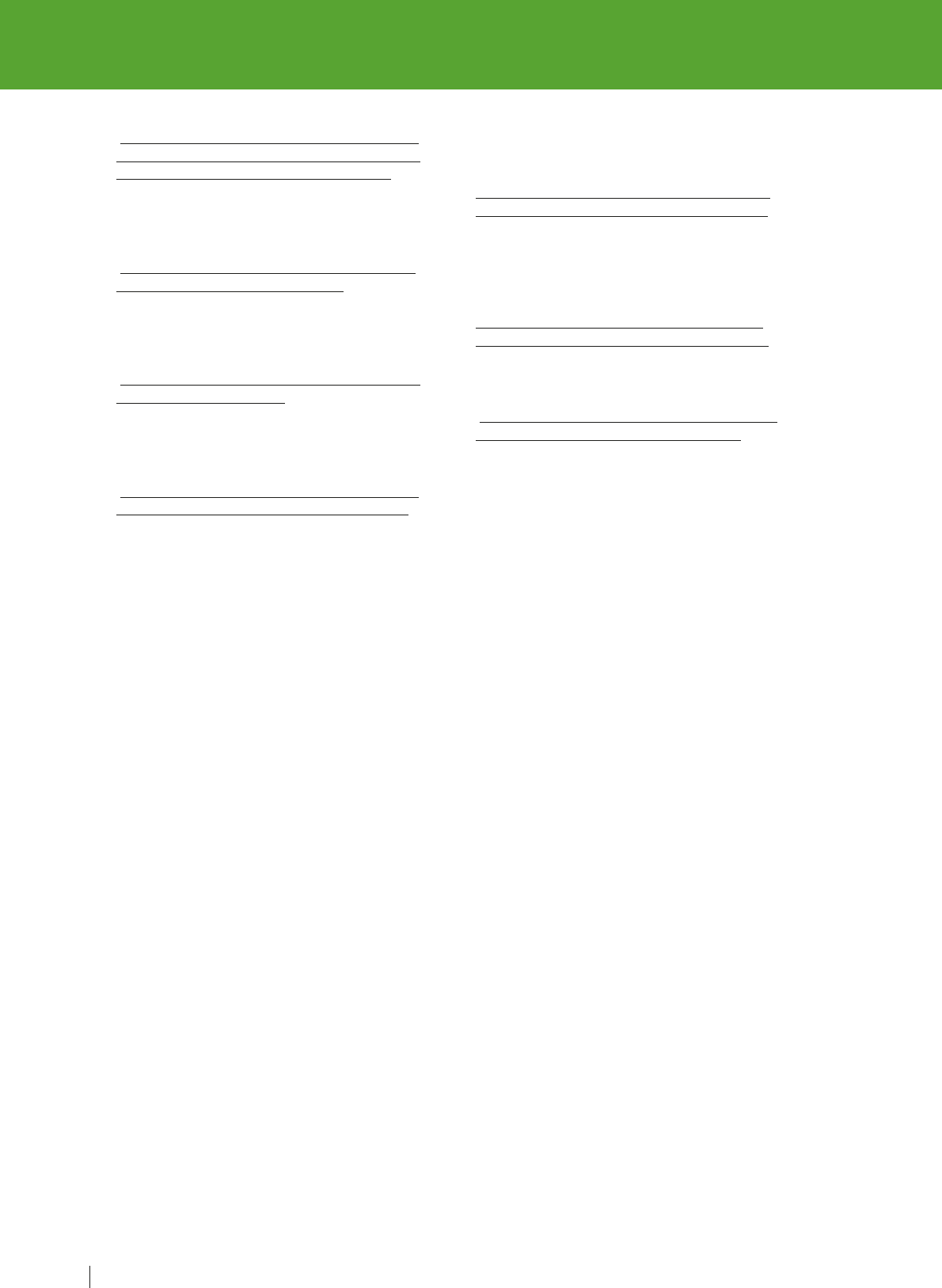

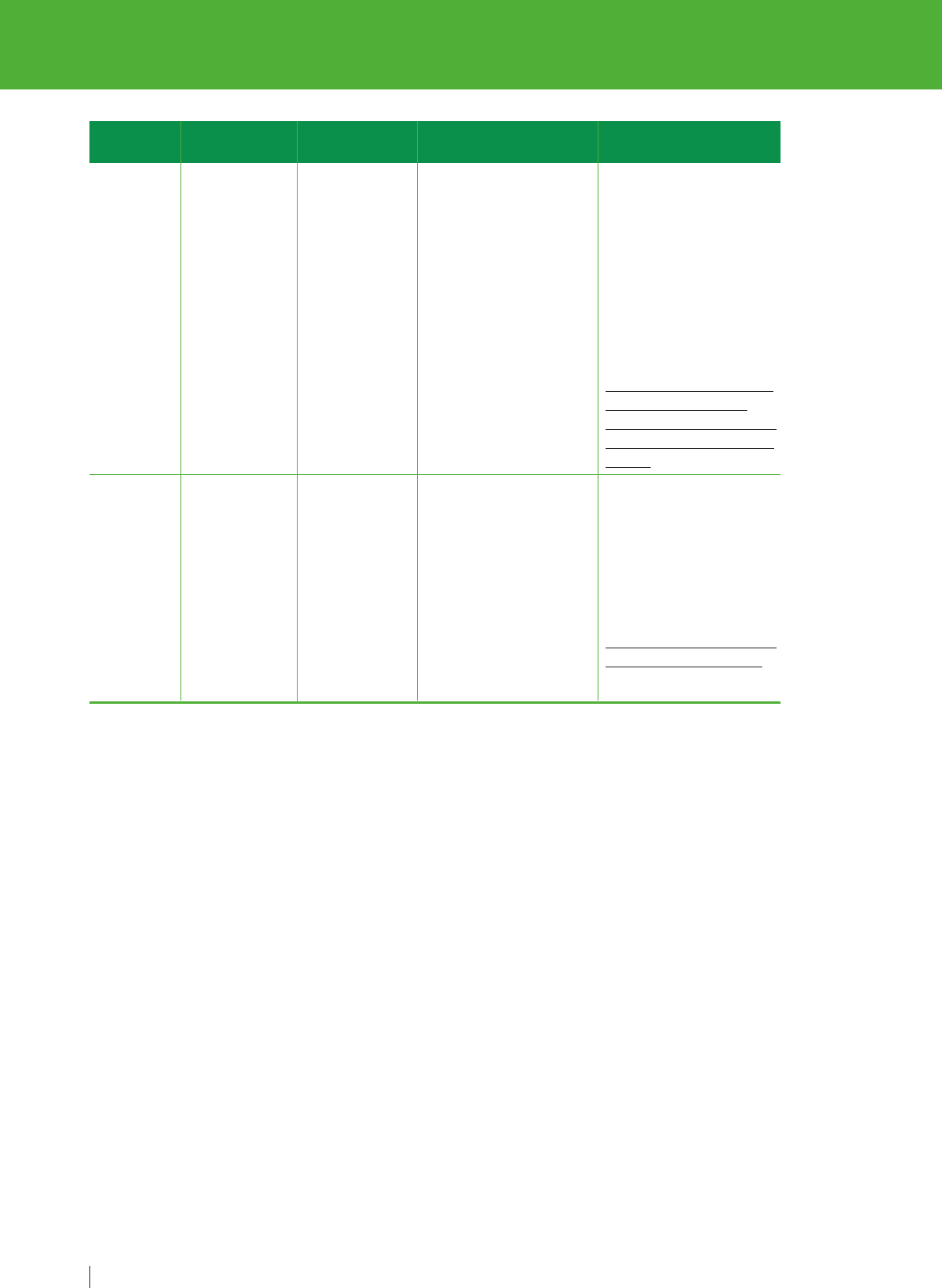

Medication-related harm is harm caused to

a patient due to failure in any of the various

steps of the medication use process or due

to adverse drug reactions (see Annex 1 for

glossary). The relationship and overlap between

medication errors and adverse drug events

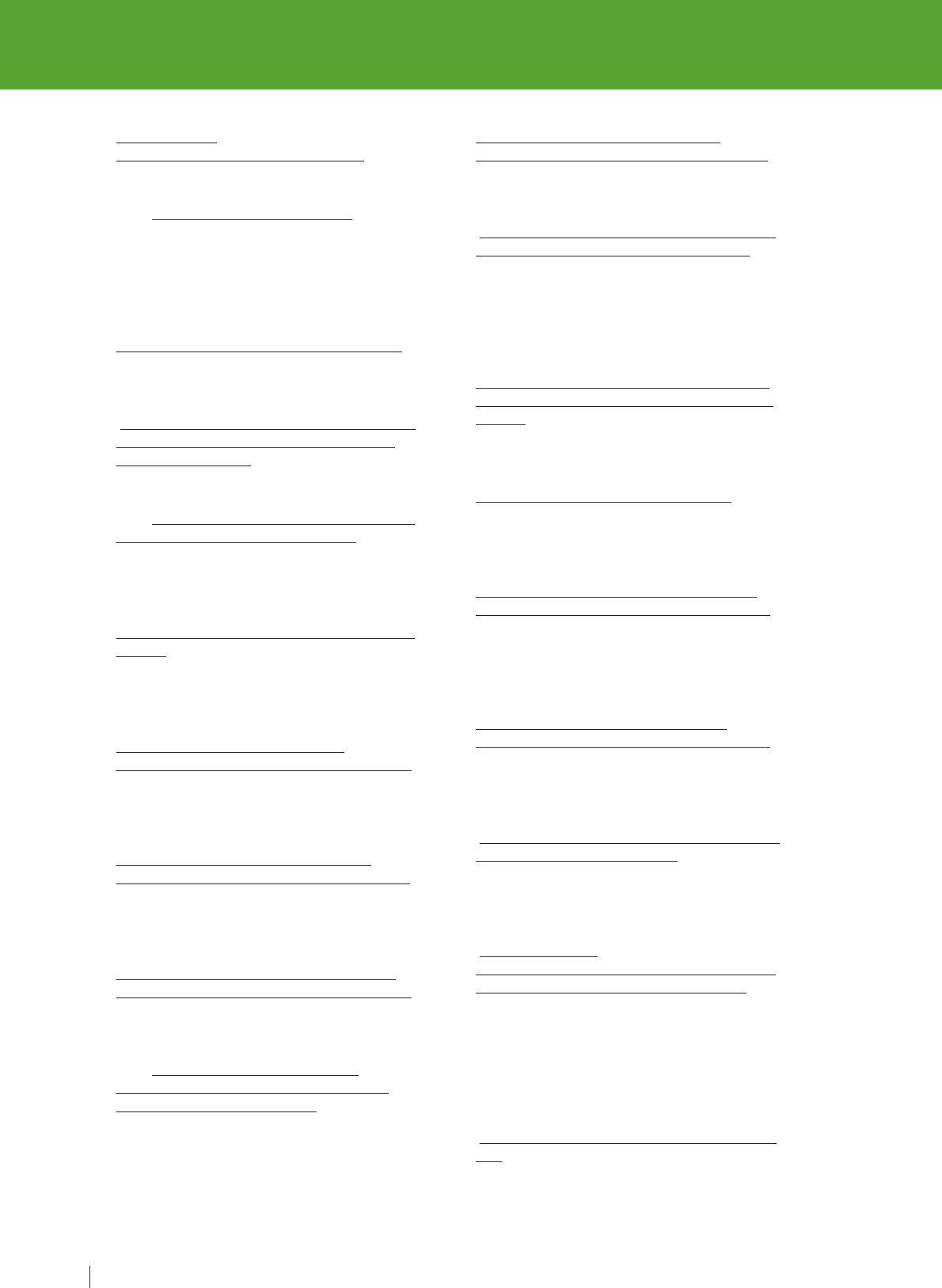

is shown in Figure 2.

8

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

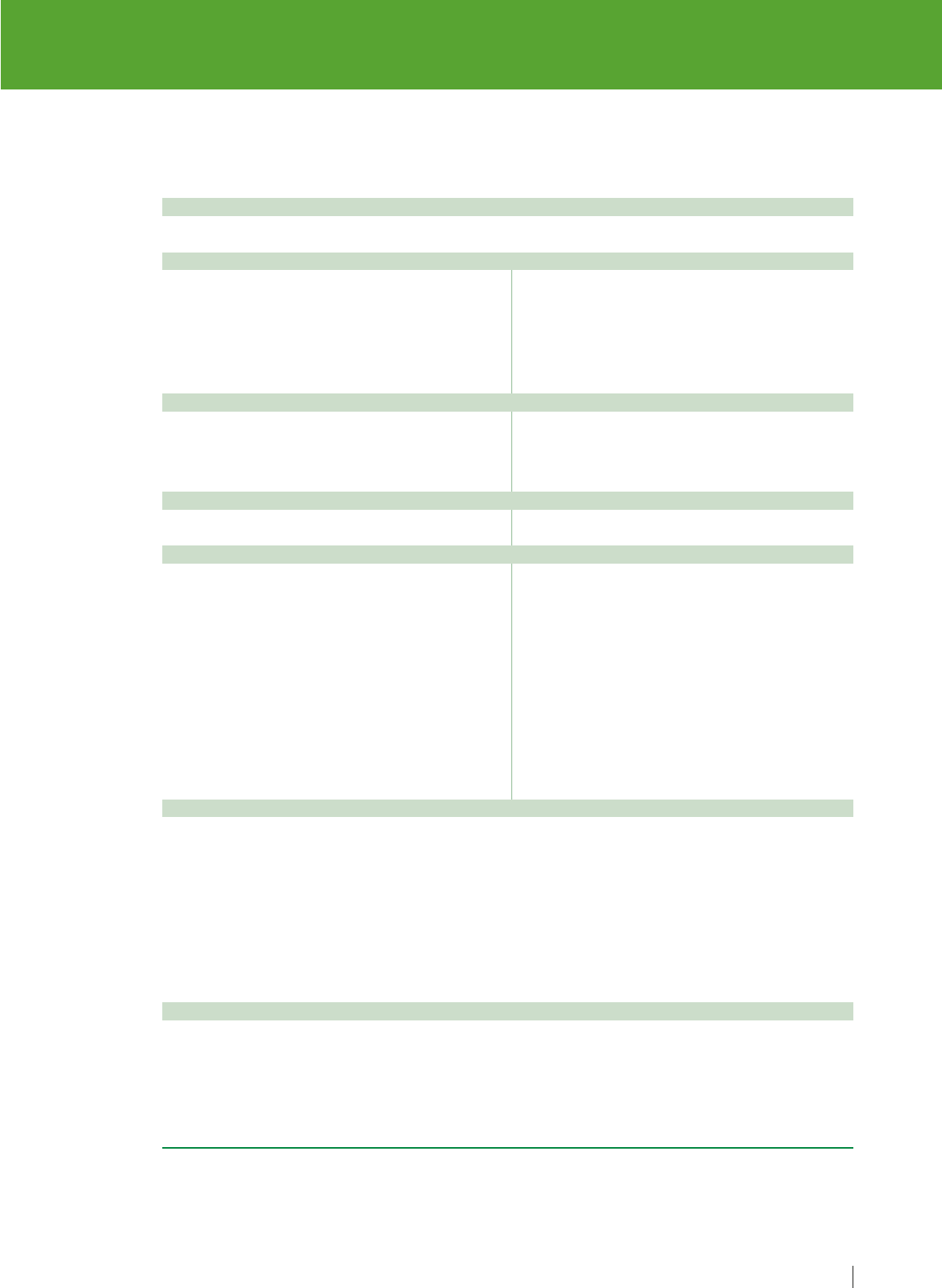

Figure 2. Relationship between medication errors and adverse drug events

Source:

Reproduced, with the permission of the publisher, from Otero and Schmitt

(6)

.

Adverse

drug

reactions

Injury No injury

OutcomesCauses

Not preventable Preventable

Inherent risk

of drugs

Medication errors

Adverse drug events

Preventable

adverse drug

events

Potential

adverse drug

events

Trivial

medication

errors

9

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

WHO is presenting a set of three technical

reports –

Medication safety in high-risk

situations

,

Medication safety in polypharmacy

,

and

Medication safety in transitions of care

–

to facilitate early priority actions and planning

by countries and key stakeholders to address

each of these areas. The technical reports are

intended for all interested parties, particularly

to inform national health policy-makers and

encourage appropriate action by ministries

of health, health care administrators and

regulators, organizations, professionals,

patients, families and caregivers, and all who

aim to improve health care and patient safety.

This report –

Medication safety in

polypharmacy

– outlines the problem, current

situation and key strategies to reduce

medication-related harm in polypharmacy.

It should be considered along with the

companion technical reports on

Medication

safety in high-risk situations

and

Medication

safety in transitions of care.

10

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

Ensuring medication safety in polypharmacy

is one of the key challenges for medication

safety today. Due to the traditional focus

of both medical research and health care

delivery models on single-disease

interventions, there has been a notable lack

of evidence-based solutions. Conventionally

polypharmacy has been perceived as an

overuse of medicines, whereas it may be more

useful to perceive in terms of appropriateness,

as there are many cases where the concurrent

use of multiple medicines may be deemed

necessary and beneficial. Globally the

prevalence of polypharmacy is set to rise as

the population ages and more people suffer

from multiple long-term conditions. Countries

should therefore prioritize raising awareness

of the problems associated with inappropriate

polypharmacy and the need to address this

issue.

All stakeholders have a vital role to play

in driving change for the management

of polypharmacy. Polypharmacy management

involves multifaceted decision-making and

necessitates the combined knowledge of

physicians, nurses, pharmacists and other

health care professionals, including the

systematic involvement, engagement and

empowerment of patients. Thus it is important

to implement interventions, such as medication

reviews, whenever possible in collaboration

with the patient and/or the caregiver. Good

communication and accurate sharing of

information is essential and can be facilitated

by the use of patient-held medication records.

Furthermore, a redesign of care processes

and/or services may be necessary to help

medical practitioners manage workload

related to polypharmacy in order to improve

medication safety.

In complex health care setting with many

competing priorities, it is useful to outline

the safety, clinical and economic implications

for appropriate polypharmacy management.

It can also be helpful to develop an

implementation plan which applies change

management and implementation theories

and tools. The four domains in the strategic

framework of the third WHO Global Patient

Safety Challenge:

Medication Without Harm

can assist in providing a guiding structure

to create a medication safety strategy

addressing polypharmacy.

Executive summary:

medication safety

in polypharmacy

11

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

Introduction

1

This technical report does not attempt

to cover the entire scope of polypharmacy,

but merely aims to introduce polypharmacy

as a concept, and examine some approaches

for the appropriate management of

polypharmacy, which are crucial for ensuring

greater medication safety.

1.1 Polypharmacy

Despite the increasing prevalence

of polypharmacy, the term continues to lack

a clear universal definition. A recent systematic

review of the definitions of polypharmacy

showed that the term was most commonly

applied to situations where patients took five

or more medications, and this numerical

definition was used by 46.4% of the studies

evaluated

(7)

. Furthermore, there are

inconsistencies with the use regarding

duration of therapy and whether to include

over-the-counter (OTC), and traditional and

complementary medicines in the definition

or not. However, with the aim of reducing

medication-related harm, it is important

to verify to the fullest extent possible all

the medications that the patient is taking,

including all OTC, and traditional and

complementary medicines.

While polypharmacy is often defined as

routinely taking a minimum of five medicines,

it is being more frequently suggested that

the emphasis should be on evidenced-based

practice (

7

). The goal should be to reduce

inappropriate polypharmacy (irrational

prescribing of too many medicines)

and to ensure appropriate polypharmacy

(rational prescribing of multiple medicines

based on best available evidence and

considering individual patient factors and

context) (

7–11

). Therefore, appropriate

polypharmacy should be considered at every

point of initiation of a new treatment for the

patient, and when the patient moves across

different health care settings.

Polypharmacy is the concurrent use

of multiple medications. Although there

is no standard definition, polypharmacy

is often defined as the routine use of five

or more medications. This includes

over-the-counter, prescription and/or

traditional and complementary medicines

used by a patient (see Annex 1).

12

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

Polypharmacy has been described as

a significant public health challenge

(13)

.

It increases the likelihood of adverse effects,

with a significant impact on health outcomes

and expenditure on health care resources

(14–16)

. Although co-prescribing multiple

medicines increases the risk of adverse events,

it is important to note that assigning a numeric

threshold to define polypharmacy is not always

useful. There are cases where polypharmacy

is necessary and beneficial, such as the

secondary prevention of myocardial infarction,

which requires the use of four different classes

of medications (a beta blocker, a statin, an

antiplatelet agent and an ACE inhibitor)

(8, 12)

.

Appropriate polypharmacy recognizes that

patients can benefit from multiple medications

if the patients’ clinical conditions,

comorbidities, allergy profiles, the potential

drug–drug and drug–disease interactions

are considered, and the medicines are

prescribed based on the best available

evidence

(17)

. Thus, it is critical to distinguish

appropriate polypharmacy from inappropriate

polypharmacy

(12)

.

The most vulnerable patient groups to the risks

of polypharmacy are susceptible to events

such as drug–drug interactions, higher risk

of falls, ADRs, cognitive impairment,

non-adherence and poor nutritional status

(18–20)

. Vulnerable patient groups often

include older patients above the age of

65 years and patients who are living in care

homes

(19–21)

.

1.2 Prevalence of polypharmacy

Polypharmacy is a major and growing public

health issue occurring within all health care

settings worldwide

(8, 13)

. The issue is well

described in literature from countries in North

America

(10, 18)

, Europe

(8, 22)

and the

Western Pacific

(23)

, with more data becoming

available from other countries in recent years.

Additional information from selected countries

is available in Annex 2, illustrating that

polypharmacy is a global problem. However,

variation in the structure of health care delivery

and data collection systems, compounded

by the different operational definitions of

polypharmacy, makes country comparison

difficult.

Multimorbidity is defined as the presence

of two or more long-term health conditions,

which can include (a) defined physical and

mental health conditions such as diabetes

or schizophrenia; (b) ongoing conditions

such as learning disability; (c) symptom

complexes such as frailty or chronic pain;

(d) sensory impairment such as sight or

hearing loss; and (e) alcohol and substance

misuse (see Annex 1).

While its true magnitude is not known,

the prevalence of polypharmacy is expected

to rise due to a multitude of factors

(8)

. First,

the global population faces a demographic

shift with the proportion of older population

Appropriate polypharmacy is present, when (a) all medicines are prescribed for the purpose of

achieving specific therapeutic objectives that have been agreed with the patient; (b) therapeutic

objectives are actually being achieved or there is a reasonable chance they will be achieved in

the future; (c) medication therapy has been optimized to minimize the risk of adverse drug

reactions (ADRs); and (d) the patient is motivated and able to take all medicines as intended

(12)

.

Inappropriate polypharmacy is present, when one or more medicines are prescribed that are

not or no longer needed, either because: (a) there is no evidence based indication, the indication

has expired or the dose is unnecessarily high; (b) one or more medicines fail to achieve the

therapeutic objectives they are intended to achieve; (c) one, or the combination of several

medicines cause ADRs, or put the patient at a high risk of ADRs or because (d) the patient is not

willing or able to take one or more medicines as intended

(12)

.

13

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

groups on the rise. It has been estimated

that the global population aged over 65 years

will double from 8% in 2010 to 16% in 2050

(24)

. In 2015, approximately 5% of the

population in OECD countries were aged

80 years and above, this percentage is

expected to rise more than double by 2050

(25)

. Second, epidemiological data indicates

that multimorbidity increases markedly

with age. In a Scottish study, multimorbidity

was prevalent in 81.5% of individuals aged

85 years and over, with a mean number of 3.62

morbidities

(26)

. Ornstein et al. found that the

most prevalent chronic conditions in primary

care were hypertension (33.5%), hyperlipidemia

(33.0%), and depression (18.7%)

(27)

. The

presence of multiple morbidities is associated

with multiple symptoms, impairments and

disabilities. Multimorbidity may result in

a combined negative effect on physical

and mental health, and can have a major

impact on a person’s quality of life, limiting

daily activities and reducing mobility

(28, 29)

.

The need to take multiple medications can be

just as problematic, resulting in frequent health

care contacts and an increase in the likelihood

of medication-related harm

(30)

. Furthermore,

it imposes a large economic burden due

to patients’ complexity of health care needs

and frequent interaction with health services,

which may be fragmented, ineffective and

incomplete

(31)

.

Despite extensive advances in

pharmacotherapy, the availability of clinical

guidelines for older adults with multiple

morbidities is limited

(28)

. Prescribing is largely

based on evidence-based guidance for single

diseases, which does not generally take into

account multimorbidity

(21, 28, 32)

.

Consequently, patients are often prescribed

several medicines recommended by a number

of specialists using disease-specific guidelines

which in combination makes the management

of any single disease challenging and may

even lead to patient harm

(21, 26)

.

1.3 Economic impact

of polypharmacy

Advancing the responsible use of medicines:

applying levers for change

identified several

opportunities to reduce health care spending

through more responsible use of medicines

worldwide. The authors estimated that

mismanaged polypharmacy contributed to 4%

of the world’s total avoidable costs due

to suboptimal medicine use. A total of US$ 18

billion, 0.3% of the global total health

expenditure could be avoided by appropriate

polypharmacy management. Some of the

specific recommendations outlined in the

report included

(33)

:

•

investment in medical audits targeting older

patients with multiple medications;

•

support for a greater role of pharmacists in

medication management and in collaboration

with health care professionals for review

of therapeutic plans;

•

identification of high-risk patients and

preparation of targeted medicine

management plans for this group; and

•

to establish a system for blame-free reporting

of medication errors.

The objectives of polypharmacy management

should be comprehensive, addressing such

issues as improved health outcomes for

the patient and population, greater patient

engagement in therapeutic decision-making

and cost-effectiveness of health care systems

and resources. This comprehensive approach –

embracing care, health and cost – has been

termed the “triple aim” strategy, and it is

designed to guide health system performance

optimization

(34)

. The term has been built

upon to become a “quadruple aim” upon

recognizing that staff wellbeing is essential

to ensure good care for the public

(35)

.

Improved safety and quality leading

to economic benefits

In a randomized control trial by Gillespie et al.

clinical pharmacists performed comprehensive

medication reviews (see Annex 1) of older

hospitalized patients. Patients that received

a medication review experienced 16%

fewer hospital visits and 47% fewer visits

to the emergency department within a 12-

month follow-up period, compared to those

with usual care. In addition, medication-related

readmissions were reduced by 80%. After

factoring in the intervention costs, the

comprehensive medication reviews were found

to lower the total hospital-based health care

cost per patient by US$ 230. The conclusion

presumed that the addition of clinical

pharmacists to health care teams on a wider

scale could result in even greater health care

cost reductions and reducing morbidity

(36)

.

1.4 Other factors influencing

appropriate polypharmacy

Social determinants of health and lifestyles

A proactive approach to sustainable and

appropriate medication regimens should target

lifestyles as part of the health management

process. It is recognized that an unhealthy

lifestyle can contribute to multimorbidity,

requiring treatment with multiple medications

(37)

. Unhealthy lifestyle factors should be

discussed with patients when considering

alternatives to medication. The WHO

Active

ageing: a policy framework

identified three

important economic factors for active ageing:

income, work and social protection

(38)

.

Individuals with low incomes may be restricted

in their choice of healthy ageing options as

healthy foods, health care and housing may be

less affordable and accessible, and are thus

at higher risk of ill health and disability

(39)

,

which can be exacerbated for patients with

polypharmacy.

Non-adherence

Non-adherence to prescribed medication is

a major challenge in polypharmacy, particularly

among older persons and/or in patients with

multimorbidity. Older patients who receive

treatment for several chronic health conditions

simultaneously present both pharmacological

and medication adherence (see Annex 1) risks

(40)

. A systematic review of older patients with

polypharmacy found a correlation between

medication non-adherence and the number

of medicines being taken

(41)

.

14

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

This section outlines the case for managing

polypharmacy at the point of initiation of

treatment, when prescribing, when adding

a new medication to a patient’s list of

medications, during a medication review, or

during a medication reconciliation (see Annex 1)

when a patient moves across care settings.

2.1 Medication-related harm

in polypharmacy

Studies conducted in many countries have

estimated the rate of medication errors both

in hospitals and in general practice

(42–45)

.

One study by Avery et al. found that over a

12-month period, patients receiving five or more

medications had a prescribing or monitoring

error rate of 30.1%, while in those receiving

10 or more medications the error rate was 47%,

demonstrating that the error rate increased

with the number of medicines prescribed

(42)

.

Another study conducted across eight

countries found that the incidence of patient-

reported errors increased with the number

of medications that were taken

(43)

.

Reporting of medication incidents such as

medication errors and ADRs associated with

polypharmacy could provide useful information

to improve patient safety

(46)

. Polypharmacy

may have harmful implications for patients

such as an increased risk of medication errors,

drug–drug interactions, suboptimal patient

adherence and reduced quality of life

(8, 47,

48)

. Health care professionals together with

patients and caregivers play a crucial role in

reporting medication-related events

(46, 49).

Learning from medication incidents is vital

for the implementation of preventive strategies

and interventions in order to reduce risk and

prevent harm from occurring again

(46)

.

Polypharmacy at transitions of care

When patients move across care settings,

medication reconciliation is an important issue

that needs to be addressed. A systematic

review of hospital based medication

reconciliation practices showed a consistent

reduction in medication discrepancies (see

Annex 1), potential adverse effects and adverse

drug events after medication reconciliation,

with the most success seen in high-risk patient

populations such as polypharmacy patients

(50)

. Discrepancies in medication orders are

common, and they increase with the number

of medications prescribed

(51)

. A study of

post-discharge patients found that almost one

fifth of currently used prescription medicines

had not been recorded during hospitalization

and that less than half of the medications used

had been registered in the patients’ discharge

letter. This illustrates the challenge that health

care professionals encounter at transitions

of care (see Annex 1), as polypharmacy in

combination with an insufficient knowledge of

the patients’ medication history is an important

contributor to prescribing errors, which can

potentially result in adverse drug events

(52)

.

Polypharmacy in care homes

Residents of care homes may be at higher

risk of complications from polypharmacy and

inappropriate prescribing

(21)

. Findings suggest

that up to 40% of prescriptions for nursing

Medication safety

in polypharmacy

2

15

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

home residents may be inappropriate or

suboptimal

(53)

. Barber et al. found that

the average care home resident in England

was taking eight medications a day and

over two thirds of these residents had one

or more medication errors

(54)

. Inappropriate

prescribing contributes toward the medication

burden and exacerbates the problem of

inappropriate polypharmacy. This is particularly

evident with regards to the widespread

prescribing of antipsychotic medications

in patients with dementia in nursing and

residential homes

(55)

.

Non-prescribed medications

In addition to prescribed medications, many

patients self-medicate by purchasing OTC

medicines. OTC medicines, such as NSAIDs

for pain and some medications for allergies

and coughs, may interact with their prescribed

medications and have the potential to cause

harm. In some cases, patients may also be

sharing prescription medicine with other

individuals

(8, 56)

. Therefore it is important

to carefully ask patients about the use

of all types of medicines or remedies

(8)

.

Traditional and complementary medicines

The use of herbal medicines is widespread

and often taken in combination with

conventional medicines to treat diseases

(49, 57, 58)

. Health care providers should

ask their patients if they use traditional and

complementary medicines or remedies

and include these products in the medication

review, as these will contribute to the

polypharmacy burden

(8)

. Alongside drug–drug

interactions, herb–drug interactions should be

considered, as they can cause a considerable

patient safety risk

(49, 59, 60)

. Further

high-quality research is needed to identify

interactions of herbal medicines

(60)

.

2.2 Medication review

in polypharmacy

Medication review is a structured

evaluation of patient’s medicines with

the aim of optimizing medicines use and

improving health outcomes. This entails

detecting drug related problems and

recommending interventions (see Annex 1).

Medication reviews are widely used to address

inappropriate polypharmacy globally and are

also recommended by many polypharmacy

guidance documents, see Annex 3. It provides

a structured evaluation that can be used to

prevent harm, optimize treatments and improve

outcomes by optimizing the use of medicines

for each individual patient

(8, 61)

. Medication

reviews in polypharmacy should take into

account the effectiveness and the risk–benefit

ratio of the medication treatment options, and

examine these criteria for the specific patient

group in which the medication is being used.

Where possible medication reviews should be

performed in collaboration with the patient or

their caregiver

(8, 13)

.

The main purpose of medication reviews is to

improve the appropriateness of medications,

reduce harm and improve outcomes. Therefore,

it is essential to reassure that the review is not

viewed merely as a mechanism to reduce

or stop medications.

A systematic review and meta-analysis

indicated that pharmacist-led medication

reviews led to a reduction in hospital

admissions

(62)

. In addition, medication

reviews may have an effect on the reduction

of medication-related problems

(63, 64)

.

For example, a study by Schnipper et al.

found that medication reviews reduced

the number of preventable adverse drug

events 30 days after patient discharge

(64)

.

One Cochrane review found that medication

reviews may have a preventive effect on

reducing the number of emergency

department contacts, however it did not

reduce mortality or hospital readmissions.

16

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

The reducing effect on emergency department

visits was more significant in high-risk groups

(such as older persons or patients with multiple

medications)

(65)

. The general consensus

is that more evidence is necessary to

determine the effect of medication reviews

due to the heterogeneity of the studies and

limitations in follow-up time

(62, 66, 67)

.

Assessing risks and benefits

To facilitate the medication review, prescribers

need practical tools and information to help

with decision-making on the safety and

effectiveness of medicines and the

appropriateness of initiating or continuing long

term medications

(11)

. One useful measure

which helps prescribers to understand the

probable clinical efficacy of a medicine

is the number needed to treat (NNT). The NNT

can be defined as the average number of

patients who require to be treated over a time

period for one patient to benefit compared

with a control; it can also be expressed as the

reciprocal of the absolute risk reduction

(61)

.

The ideal NNT, being one, signifies that every

patient improves on the outcome with the

treatment. The higher the NNT, the less

effective the treatment is in terms of the trial

outcome and timescale. The NNT is only

a statistical estimate of the average benefit of

treatment, usually calculated based on clinical

trials. It is rarely possible to know precisely

the likely benefit for a particular patient.

However, NNT still remains a universal concept

to assess the efficacy of medicine. Several

tables and further information are available on

NNT, which can support prescribers in decision

making and aid discussions with patients

regarding the potential benefits of their

treatment

(61, 68–71)

.

Similarly to NNT, another measure used in

decision making is the Number Needed to

Harm (NNH). The NNH is the average number

of people taking a medication over a time

period in order for one adverse event to occur

(61)

. This concept is not as widely used as

the NNT. Combined with NNT, the overall

benefit to risk ratio (NNT/NNH) should be

considered for individual patients during the

decision making process. In polypharmacy

this ratio may vary considerably between

patients

(61)

. For several commonly used

medications, there are some NNT and NNH

estimates available

(61, 71)

.

Ideally, such information on risks and benefits

is made accessible and comprehensible

for the public, in order to include patients in

the decision-making process. For example,

a Scottish polypharmacy guidance tool helps

health care professionals work in partnership

with patients. This resource is available as

a combined mobile application and website

that outlines the process for initiation and

the review of treatments

(72)

.

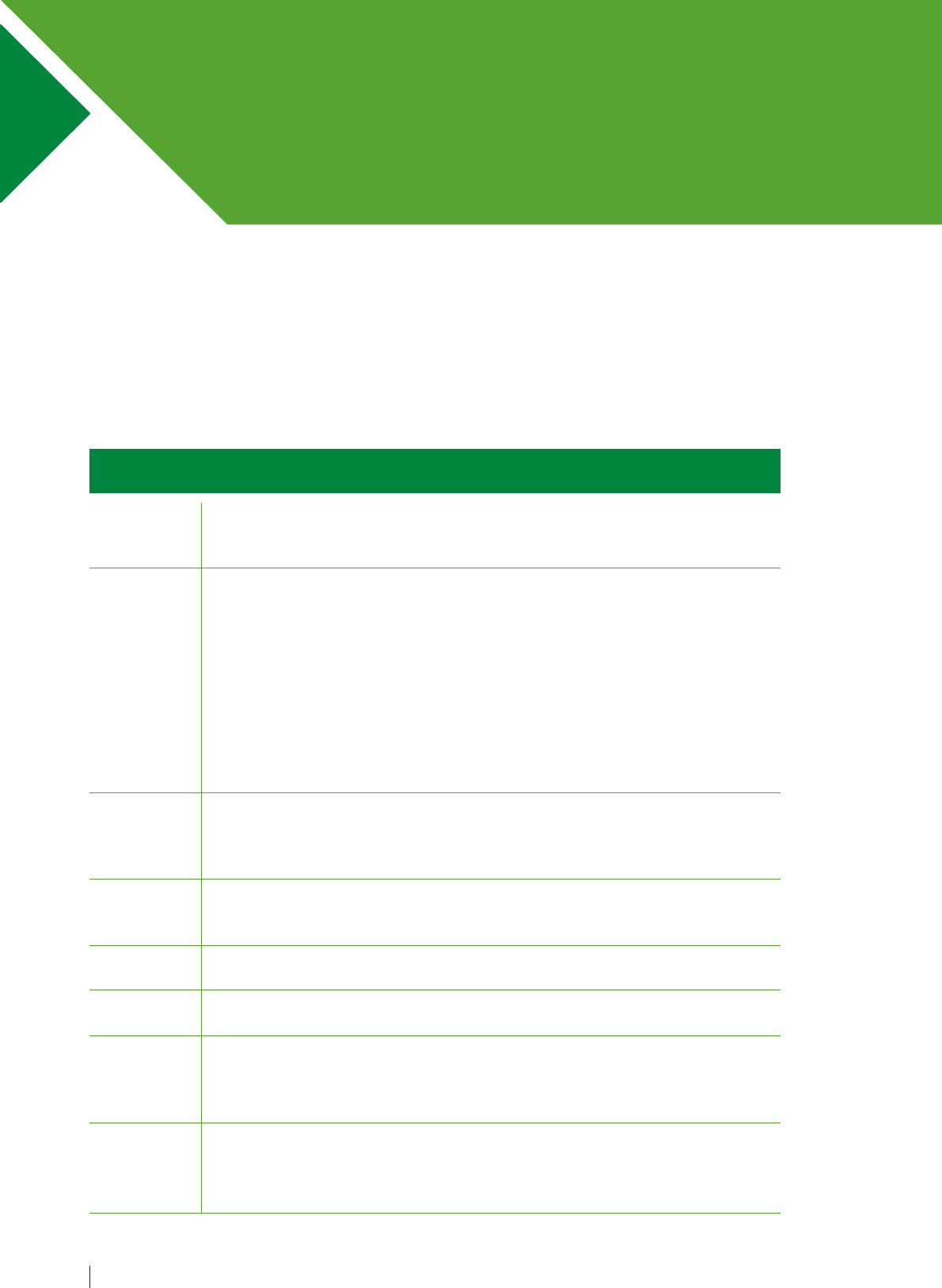

Medication review process in polypharmacy

The review process should include

engagement with the patient. The perspective

of the patient on managing and taking multiple

medications should be assessed, as well

as the patient’s goal of care. The intentions

of the patient would need to be aligned with

the prescribers’ view of improving outcomes

and treatment goals

(8)

. The information and

changes derived from the medication review

should be made available to other health care

professionals, especially as the patient

moves across different care settings, in order

to enable collaboration in appropriate

polypharmacy management. An example

of a step-by-step method to conduct

a medication review while using a patient-

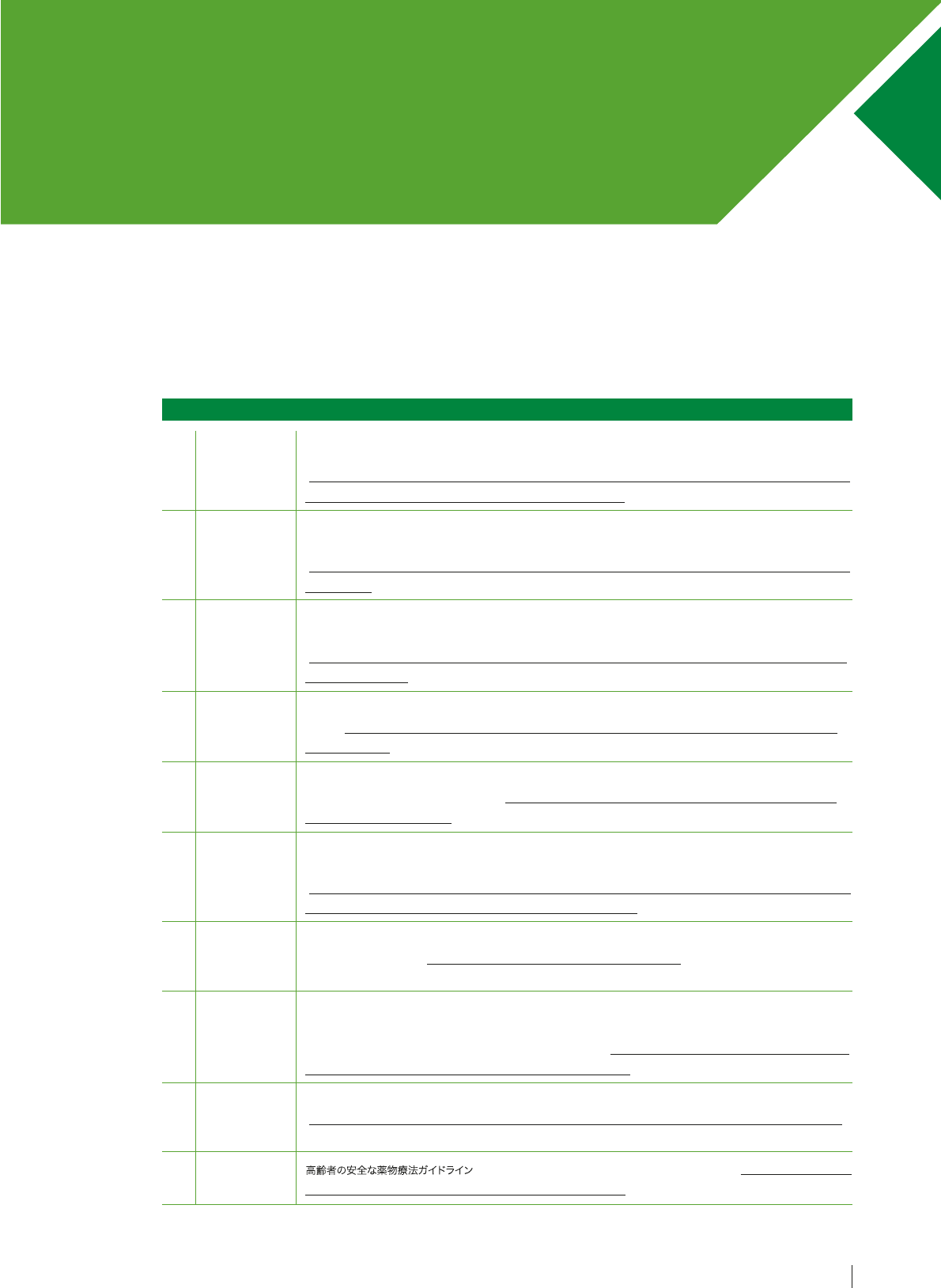

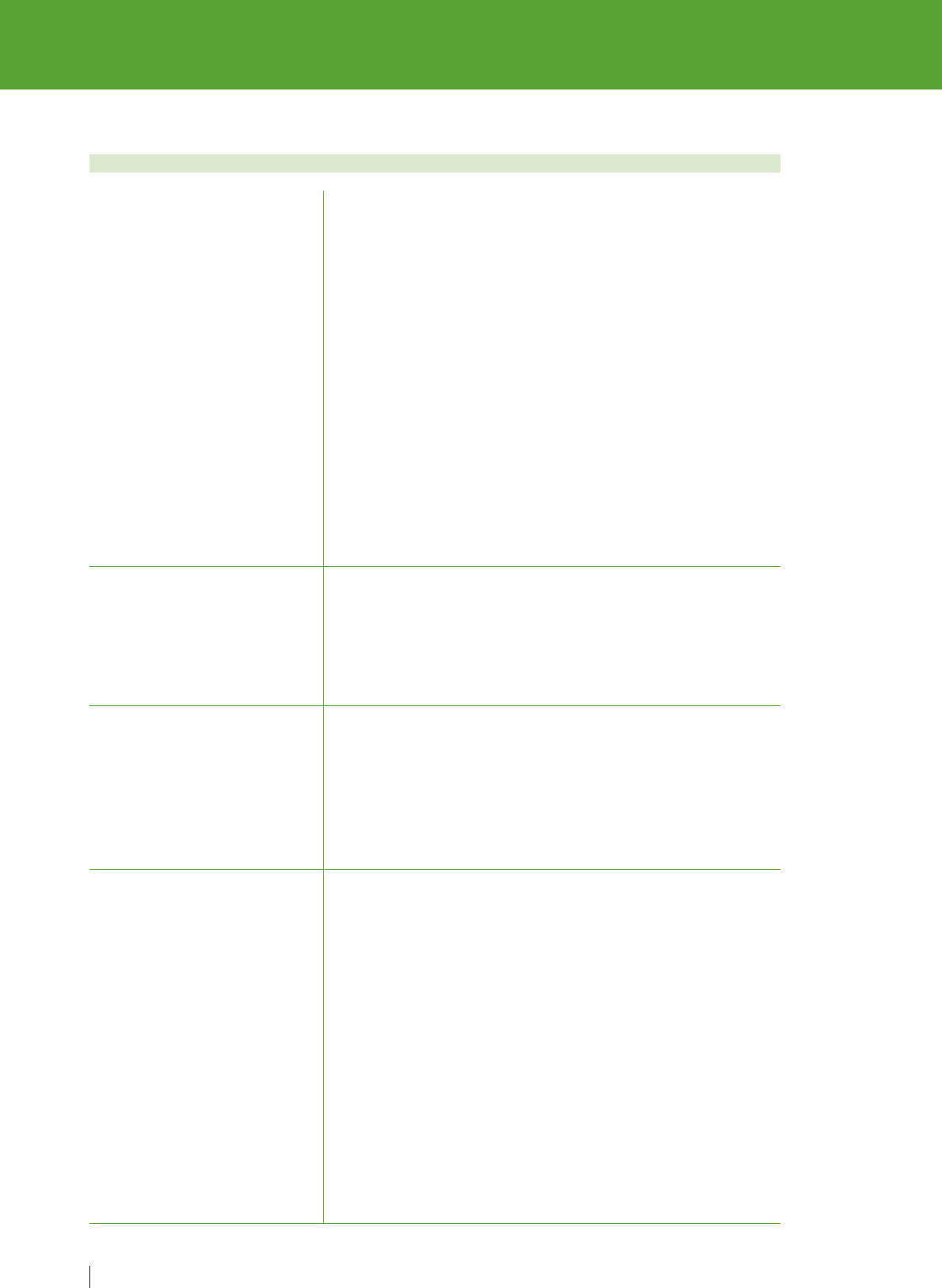

centered approach is elaborated in Table 1.

Annex 4 outlines how this process can be

further applied to selected clinical scenarios.

17

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

18

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

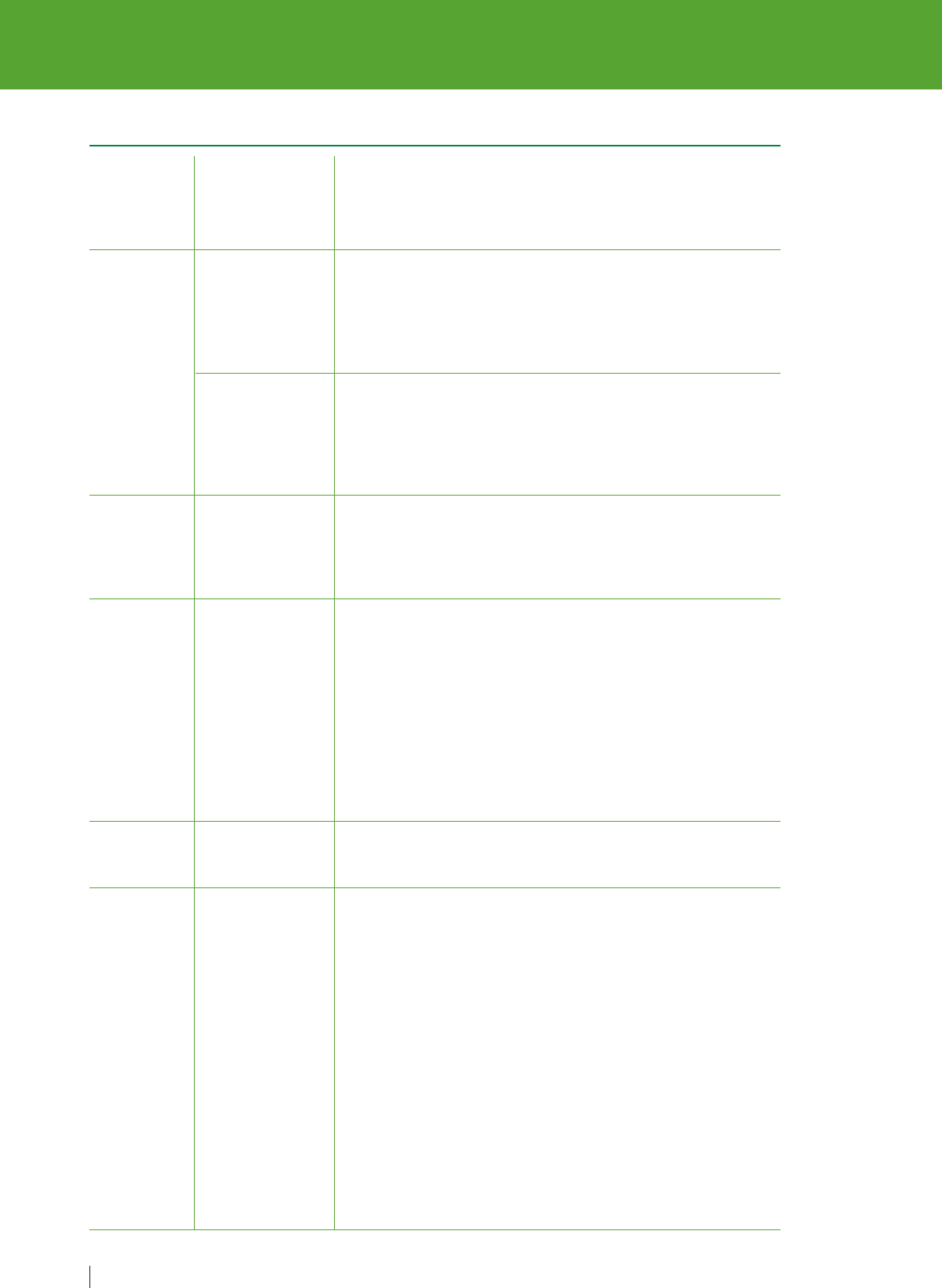

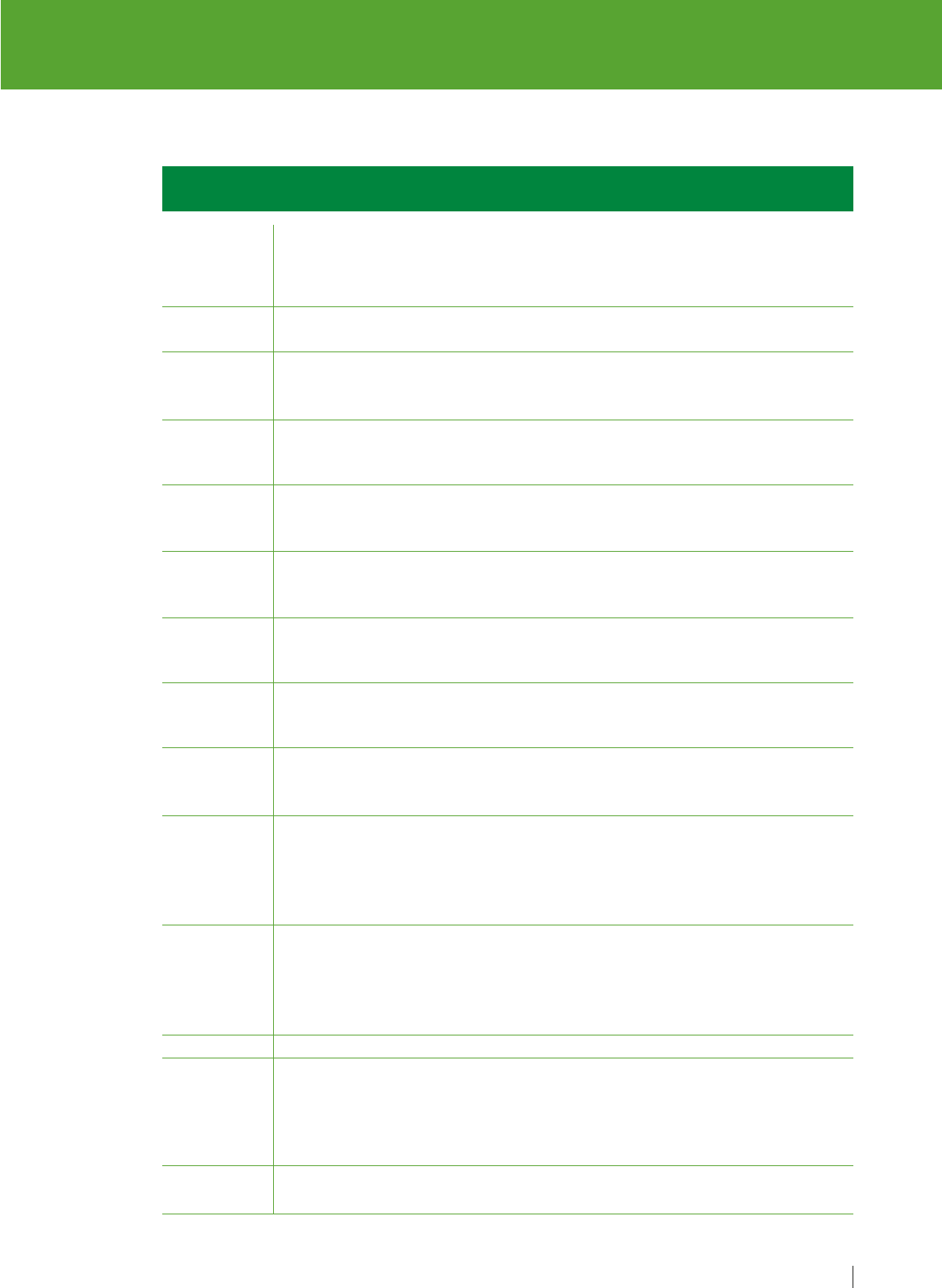

Table 1. Step-by-step approach to conducting a patient-centred medication review

Aims

Need

Effectiveness

Safety

Costs

Patient-

centeredness

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

What matters

to the patient

Identify

essential

medications

Does the

patient take

unnecessary

medications?

Are

therapeutic

objectives

being

achieved?

Does the

patient have/

is at risk of

adverse drug

reactions?

Does the

patient know

what to do if

they are ill?

Is therapy

cost-effective?

Is the patient

willing and

able to take

medication

as intended?

Review diagnoses and identify therapeutic objectives with

respect to:

• Understanding of goals of medication therapy

• Management of existing health problems

• Prevention of future health problems

Identify essential medications (not to be stopped without

specialist advice) such as:

• Medications that have essential replacement functions

(e.g. thyroxine)

• Medications to prevent rapid symptomatic decline

(e.g. medications for Parkinson’s disease)

Identify and review the (continued) need for medications:

• With temporary indications

• With higher-than-usual maintenance doses

• With limited benefit in general for the indication they are used

for

• With limited benefit for the particular patient under review

Identify the need for adding/intensifying medication therapy

in order to achieve therapeutic objectives:

• To achieve symptom control

• To achieve biochemical/clinical targets

• To prevent disease progression/exacerbation

Identify patient safety risks by checking for:

• Drug–disease interactions

• Drug–drug interactions

• Robustness of monitoring mechanisms for high-risk

medications

• Risk of accidental overdosing

Identify adverse drug effects by checking for:

• Specific symptoms/laboratory markers (e.g. hypokalaemia)

• Cumulative adverse drug effects

• Medications that may be used to treat adverse drug

reactions caused by other medications

Identify unnecessarily costly medication by:

• Considering more cost-effective alternatives (but balance

against effectiveness, safety, convenience)

Does the patient understand the outcomes of the review?

• Does the patient understand why they need to take their

medication?

• Consider teach-back technique

a

to ensure full understanding

Ensure medication changes are tailored to patient preferences:

• Is the medication in a form the patient can take?

• Is the dosing schedule convenient?

• Consider what assistance the patient might have and when

this is available

• Is the patient able to take medicines as intended?

Agree and communicate plan:

• Discuss with the patient therapeutic objectives and

treatment priorities

• Decide with the patient what medicines have an effect of

sufficient magnitude to consider continuation or discontinuation

• Inform relevant health care and social care change

in treatments across care transitions

Deprescribing is the process of tapering,

stopping, discontinuing, or withdrawing

drugs, with the goal of managing

polypharmacy and improving outcomes

(see Annex 1).

Considerations for cessation of medication

should be a part of all medication reviews,

and the process of “deprescribing” should be

as robust as that of prescribing. The process

encompasses minimization of the medication

load in terms of dosage, number of tablets

taken and frequency of administration times

(23, 74)

. Supporting tools such as

STOPP/START

criteria can be useful in deprescribing and

improving appropriate prescribing

(72, 75)

.

Examples of prescribing indicator sets

which can be used to identify inappropriate

polypharmacy and appropriateness of

prescribing are available

(8, 76)

. There are

also algorithms available that could improve

medication therapy by deprescribing, which

have been shown to be feasible

(77)

. Hence

it is important to undertake medication reviews

with a holistic approach, as medications may

need to be started or stopped, both to prevent

harm from some medications and to prevent

health deterioration

(8)

.

19

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

a

Method to confirm that the information provided is being understood by getting people to ‘teach-back’

what has been discussed and what instruction has been given

(73)

.

Source:

Adapted, with permission of the publisher, from Scottish Government Polypharmacy Model

of Care Group

(61).

In order to address inappropriate polypharmacy

multiple programmes have been implemented,

particularly in high-income countries

(78, 79)

.

To illustrate the international initiatives,

several polypharmacy guidance documents

from different countries are listed in Annex 3.

3.1 Implementing sustainable

programmes to address

polypharmacy

In the context of the third WHO Global Patient

Safety Challenge:

Medication Without Harm

,

countries are urged to take early priority action

to protect patients from harm arising from

polypharmacy by implementing programmes

which help to reduce inappropriate

polypharmacy that are sustainable and can

be delivered across the country. For the

implementation of national, subnational

or local polypharmacy guidance and new

polypharmacy practices, it may be relevant

to apply change management principles

and theory-based implementation strategies.

Tools and theories to support the

implementation process include Kotter’s

eight step process for leading change

;

political, economic, social, technological,

environmental and legal (PESTEL); and

strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and

threats (SWOT)

(11)

. A recent case study

applied Kotter’s

Eight step process for leading

change

and normalization process theory to

assess successful polypharmacy management

activities in Europe, and provided advice

that can be applied across the entire health

system to address the management of

polypharmacy

(22)

. PESTEL and SWOT

exercises enable organizations to evaluate

issues that need to be addressed to ensure

that barriers to implementation are removed

and enablers are optimized

(11)

. To support

wider implementation of medication reviews

in selected populations, an economic analysis

tool has been developed to help countries

assess the potential economic benefits

of introducing and undertaking medication

reviews in polypharmacy

(80)

.

In addition to change management tools,

some key factors that need to be considered

are described in the following. Existing health

care delivery models for polypharmacy should

be reassessed to ensure the pharmacist

plays a key role within a multidisciplinary

team alongside physicians and nurses

(33)

.

Medication reviews performed by health care

professionals would need to be incorporated

in the design of clinical pathways in the

management of patients with multimorbidity

to facilitate workflow

(81)

. Transfer of

information across transitions of care is

important to the management of appropriate

polypharmacy, because it ensures medications

that were reviewed and stopped are not

restarted without proper justification.

Addressing organizational culture

and multidisciplinary working

The organizational dynamics within health

care systems can be complex and include

20

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

Implementing polypharmacy

initiatives

3

the values, beliefs and assumptions held

by those within an organization

(33)

. Cultural

factors can facilitate or hinder the

implementation of innovative practices in

managing polypharmacy. Failure to account

for organizational culture is one of the main

reasons mentioned when evaluating why

planned initiatives fail to overcome barriers

(82)

.

Not only should the culture of the health system

as a whole be considered, but also the cultural

norms within given professions

(83, 84)

. The

results from a European Delphi study support

that “prior to implementation of polypharmacy

management, the culture of an organization

should be assessed for both strengths

and potential barriers to implementation”

(11)

.

As with change management and systems

thinking, there are multiple tools and

frameworks available to help decision-makers

identify the characteristics of the organizational

culture and to make appropriate modifications,

in parallel with a safety culture assessment

(85)

.

Various studies have identified the necessity

and benefits of multidisciplinary collaboration

when addressing polypharmacy

(10, 22)

.

Policy-makers would need to consider

addressing the legislative and contractual

barriers that are in place if appropriate

polypharmacy is to be applied across

the health care system. Political commitment

is required to ensure that dedicated resources

are allocated to the development of new

systems to address polypharmacy, but more

importantly to strengthen the existing health

care system. Political support is important

to promote multidisciplinary team work

(11)

.

For example,

Medicines Optimisation Quality

Framework of Northern Ireland

recommends

medicines optimization (see Annex 1) activities

to be delivered by multidisciplinary teams

(86)

.

3.2 Programmes on appropriate

polypharmacy

To assist countries in understanding the

hurdles and benefits of investing in

programmes addressing polypharmacy, this

report presents some programmes below.

OPtimising thERapy to prevent Avoidable

hospital admissions in the Multimorbid elderly

(OPERAM), aims to optimize existing

pharmacological and non-pharmacological

therapies to reduce avoidable hospital

admissions, particularly among older patients

with multimorbidity in Europe. The goal of the

study is to assess the impact of a structured

medication review with a software intervention,

obtain and compare intervention studies

to find what is most effective and safe in order

to determine the best and most cost–effective

measures for preventing avoidable hospital

admissions. Initiated in 2015, this study

is ongoing until year 2020

(87, 88)

.

Polypharmacy in chronic diseases: Reduction

of Inappropriate Medication and Adverse drug

events in older populations by electronic

Decision Support

(PRIMA-eDS), aims to provide

physicians with the best evidence regarding

medication therapy for older patients with

multimorbidity through an electronic decision

support tool. The electronic decision support

tool comprises of an indication check,

recommendations based on guidelines,

systematic reviews, drug interaction database,

renal dosing database, adverse effect

database and the European list of inappropriate

medications for older people

(89)

. The

practicability and relevance of the tool

was evaluated through a randomized clinical

trial to test if discontinuing inappropriate

medications could improve patient outcomes,

such as reduction of hospitalization or death;

and the patient data entry was found to be too

time-consuming. Recent findings provide

more insight in the future development of

the tool and the potential risk groups

(90, 91)

.

Stimulating Innovation Management of

Polypharmacy and Adherence in The Elderly

(SIMPATHY) project intends to stimulate,

promote and support innovation across

the European Union in the management

of appropriate polypharmacy and medication

adherence in older patients

(78)

. This project

aims to contribute to developing efficient and

sustainable health care systems. Through

21

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

stakeholder engagement, studies were

undertaken in a range of different health care

environments, including European Innovation

Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing

reference sites. The studies provide a

framework and politico-economic basis for

a European Union-wide benchmarking survey

of strategies being employed for polypharmacy

and non-adherence management. Innovative

multidisciplinary models were developed to

support patients with long-term conditions

using the professional expertise of pharmacists

and physicians to reduce inappropriate

polypharmacy and promote innovation in

health care workforce development

(11)

.

A set of contextualized change management

approaches and tools was developed to help

politicians, regulators, health service providers,

and other stakeholders to advance current

practice by implementing organizational

change, thereby improving the management

of patients on polypharmacy

(11, 80)

.

In addition to creating a European knowledge-

sharing network on polypharmacy and

adherence management, the targeted

dissemination of these validated findings may

support policy development, implementation

of strategic organizational development

and the exchange of best practices

(11)

.

There is still room for improvement,

as polypharmacy management is currently

not widely addressed within most EU

countries

(22)

. This programme has generated

information on which benchmarks can be

applied for regional and national progress

measurements, a definitive guidance on

the role of key stakeholders and guidelines

on how to initiate and manage the change

process

(11)

.

22

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

Initiatives to address polypharmacy can be

complex and require strong leadership and

management. Identifying a lead organization

and allocating responsibility could facilitate

the implementation of polypharmacy

management initiatives at the regional or

national level. Organizational leadership

is vital in driving change to achieve effective

polypharmacy management

(11)

. The need

to address polypharmacy is universal, but

the challenge of leading change goes

to the heart of the policies and culture of

organizations, requiring the active involvement

of policy-makers, health care professionals

and managers, as well as patients, families

and caregivers

(61)

. Often the window

of opportunity to ensure that change is

implemented is small, with three components

being crucial: problem recognition, generation

of policy proposals, and a supportive political

environment, to create a momentum for

a change in public policy

(92)

. Countries may

wish to consider using existing infrastructure

such as pharmacovigilance centres

(see Annex 1) and patient safety incident

reporting and learning systems (RLS) to collect

reports as well as to disseminate learning

from harm occurring from polypharmacy

and drug interactions

(46, 49)

.

The irrational use of medicines is a global

issue. A WHO report,

The World Medicines

Situation

, estimated in 2004 that half of all

medicines are inappropriately prescribed,

dispensed or sold. Furthermore, half of all

patients fail to take their medicine as

prescribed. This can be harmful to patients,

leads to ineffective therapies and waste of

resources, generating an unnecessary burden

for the patient as well as the whole society.

Inappropriate polypharmacy is a common

example of irrational use of medicines.

To address the challenge at the system level,

effective policies such as supportive incentive

structures, education and management,

clear clinical guidance and appropriate

training are considered far-reaching

(93)

.

When deciding how to address polypharmacy,

any solution needs to achieve the

aforementioned “quadruple aim”, so that

quality of prescribing and outcomes from

medication are improved whilst delivering

an economically sustainable solution that

will promote patient engagement across

the health care system without compromising

the work life of health care professionals

(35)

.

In many countries polypharmacy management

may not be widely addressed, which makes

it important to establish change management

strategies to support implementation

at a national scale

(22)

. An initial step would be

to undertake a benchmarking survey so that

countries can assess their current status

with regard to polypharmacy. Business

operation tools such as PESTEL and SWOT

analysis have been used for polypharmacy

programmes, and are helpful in identifying

barriers and issues that countries would need

to address in order to improve polypharmacy

management

(11)

.

Health systems

approach to polypharmacy

4

23

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

In order to attain medication safety in

polypharmacy management, a strategy could

be developed using the strategic framework of

the third WHO Global Patient Safety Challenge:

Medication Without Harm

. The key domains

to be addressed as part of this framework

include patients and the public, medicines,

health care professionals, and systems and

practices of medication. The four domains

and the cross-cutting theme of monitoring

and evaluation are elaborated in the following

sections, addressing a health system

approach for implementing polypharmacy

programmes under the umbrella of

the Challenge.

4.1 Patients and the public

The role of patients in delivering

appropriate polypharmacy

Raising patient awareness about the problems

of polypharmacy and non-adherence is

important, as patients can play a key role in the

prevention and early detection of inappropriate

polypharmacy (

11

,

21

). Patients should be

seen as shared decision-makers on the use of

medication, and health care professionals need

to support patients, families and caregivers in

order to enable them to undertake this role (

8

).

Patients should be encouraged and supported

to disclose all the medications they are taking,

including OTC and traditional and

complementary medicines, especially if they

are suffering from multiple conditions and are

being treated with polypharmacy (

94

). Health

literacy, social norms and cultural factors

would need to be taken into account when

considering the role of patients, and designing

materials for patient education (

95

,

96

).

Patient tools and materials can support the

engagement and empowerment of patients,

families and caregivers in playing an active

role in health care. Such resource materials

may include:

• Patient-held medication list or patient-held

medication record, sometimes called

medication passport (either paper or

electronic), can help to optimize patients’

medicines. The use of these tools has

received positive feedback from patients (

97

).

Such lists, provided that they are up-to-date,

can also be helpful at care transitions (

98

).

• Patient resource materials that enable

patients to understand how to make

decisions regarding management of their

health conditions and their medications

are available (

99

,

100

). An example of

a tailormade tool is the

Medicine Sick Day

Rules card

, which explains to patients which

medicines should be temporarily stopped

during dehydration due to an illness (

101

).

Different organizations, including WHO,

have developed materials that include

simple questions to encourage patients

to be active participants in their therapeutic

decision-making (

102–104

). For example,

the

5 Moments for Medication Safety

focuses

on five key moments in the medication use

process, where action by the patient, family

member or caregiver can greatly reduce

the risk of harm associated with the use

of medications. The tool aims to engage

and empower patients to be involved in their

own care in a more proactive way and feel

responsible for it, encourage their curiosity

about the medications they are taking,

empower them to communicate openly

with their health professionals and be

involved in shared decision-making (

104

).

Technology could improve both patient

experience and medication adherence.

Furthermore, it has potential to enable patients

to be active participants in medication reviews.

However, more research is required to evaluate

strategies for integrating such tools into clinical

practice and to ensure they meet their potential

in improving patient outcomes and creating

value for all users (

105

,

106

).

Prioritizing patients for medication reviews

in polypharmacy

Due to limited resources in most health care

systems, patients who may benefit from

medication reviews need to be prioritized.

There are many factors that could increase

the likelihood of predisposing a patient to harm

24

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

25

MEDICATION SAFETY IN POLYPHARMACY

from medication. Research has shown that

patients on multiple medications have

a higher risk of medication-related harm, due

to harm from occurrences such as drug–drug

interactions, falls and adverse events (

8

,

48

).

Any methods for identifying patients at risk due

to polypharmacy need to be considered in the

clinical context. Even in resource-limited

settings with inadequate health information

databases, the following criteria can be applied

to identify situations where a medication review

may prove beneficial:

• residents in a care home setting (

12

,

21

)

• patients on high-risk (high-alert) medications

(see Annex 1) (

12

)

• patients taking 10 or more medicines

(

12

,

21

,

107

)

• patients with two or more co-morbidities (

12

)

• patients with frailty (

12

,

77

,

20

)

• patients with dementia (

12

,

108

)

• palliative care situations (

8

,

12

)

4.2 Health care professionals

Health care professionals and policy-makers

can take a leadership role in raising awareness

among peers regarding the role of medication

review in reducing the harm associated

with inappropriate polypharmacy (

11

).

Development of multidisciplinary workforce

through changes in undergraduate,

postgraduate, and continuing professional

development has been identified as a key area

to address polypharmacy (

22

). Educational

curricula for health care professionals, including

physicians, pharmacists and nurses, should

include safe medication management to

develop necessary competencies and skills

for addressing risks associated with

polypharmacy (

109

). To help support education

of health care professionals, a set of clinical

case studies are presented in Annex 4.

Existing guidelines that incorporate key steps

for patient-centered medication review should

be shared to ensure the dissemination of best

practices, including the importance of sharing

the information about the outcomes of

the medication review in polypharmacy

with relevant health care professionals.

Establishing support networks to enable

health care professionals in sharing scientific

and practical information on polypharmacy

may assist in that regard. There are several

special interest groups focusing on appropriate

polypharmacy available internationally

(

110–112

).

Health care professionals working in

multidisciplinary teams deliver optimum

outcomes for patients. They need to be

aware of human factors that may affect their

performance and the performance of others

(

113

). Knowledge of human factors can be

further useful in communication with

patients and in shared decision-making

in polypharmacy (

109

).

A study from Hawaii revealed that many older

persons were uncertain about the information

about their medications and did not exhibit

confidence on understanding the ADRs

associated with use of multiple medications

(

114

). This emphasizes the need for

interventions that are aimed at enhancing

the provider–patient interaction about

polypharmacy and medication reviews.

Safety culture should be addressed to enable

health care professionals and patients

to discuss issues of polypharmacy, so that

patients feel that it is safe and acceptable

to ask questions (

95

). For example,

Choosing

Wisely

campaign focuses on promoting

dialogue between health care professionals

and patients; with the aim to reduce utilization

of inappropriate tests and medical treatment,

empower patients to ask questions, and help

patients to choose evidence-based care (

115

).

4.3 Medicines

Polypharmacy and drug interactions

Patients with polypharmacy might be subject

to drug–drug, drug–food, drug–disease

or herb–drug interactions (

116

). Detection

of drug interactions should be included

in the monitoring process of long-term

and latent effects of medications as part

of post-marketing surveillance (

49

). Such

information is pivotal for health care professionals

prescribing or reviewing medication lists to

ensure safe use of medicines. Drug interaction

and contraindication databases and various

computer systems are increasingly available

in hospitals and general practice. However,

technology systems may not flag all relevant

potential harm (

8

,

117

), or they may conversely

lead to numerous reminders, creating

an information overload for health care

professionals and over-riding of reminders

inappropriately (

118

). While there is a huge

potential in computer-based systems to prevent

medication-related harm (for example, by

helping to detect contraindications, interactions

or potentially inappropriate choice of medicine),

they should not replace health care

professionals’ own clinical judgement (

117

).

Medication management and adherence

In polypharmacy it is important to find