Feasibility of the Use of the ACT and SAT in Lieu

of Florida Statewide Assessments

Volume 1: Final Report

In partnership with:

Ed Roeber

John Olson

Barry Topol

Norman Webb

Sara Christopherson

Marianne Perie

Jesse Pace

Sheryl Lazarus

Martha Thurlow

January 1, 2018

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 2

CITATION

This report was written by the Assessment Solutions Group and its partners in this study with

support from the Florida Department of Education

Citation: Roeber, E., Olson, J., & Topol, B. with Webb, N., Christopherson, S., Perie, M., Pace, J.,

Lazarus, S., Thurlow, M. (2018). Feasibility of the Use of the ACT and SAT in Lieu of Florida

Statewide Assessments: Volume 1: Final Report. Assessment Solutions Group.

The information in this report reflects the views of the authors. Publication of this document

shall not be construed as endorsement of the views expressed in it by the Florida Department

of Education

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 3

Table of Contents

Volume I – Report

Executive Summary 4

Background and Purpose of the Project 9

ASG and Partners Plan of Study 10

Section 1 – Alignment (Criteria 1 and 2)

– Mathematics 15

– ELA 47

Section 2 – Comparability (Criterion 3) 74

Section 3 – Accommodations (Criterion 4) 94

Section 4 – Accountability (Criterion 5) 125

Section 5 – Peer Review (Criterion 6) 140

Section 6 – Summary and Conclusions 171

Change Log 175

Volume II: Appendices (provided separately)

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 4

Executive Summary

In the 2017 Florida legislative session, HB 7069 was passed and signed into law on June 15, 2017.

The legislation states, in part:

“The Commissioner of Education shall contract for an independent study to determine

whether the SAT and ACT may be administered in lieu of the grade 10 statewide,

standardized ELA assessment and the Algebra 1 end-of-course assessment for high school

students consistent with federal requirements under 20 U.S.C. s. 6311(b)(2)(H). The

commissioner shall submit a report containing the results of such review and any

recommendations to the Governor, the President of the Senate, the Speaker of the House of

Representatives, and the State Board of Education by January 1, 2018.”

The Florida Department of Education (FDOE) issued RFP 2018-48 to solicit vendors to

independently conduct studies, research, analyses, and Florida educator and expert meetings,

and produce a final report to this effect. Assessment Solutions Group (ASG) and its team of

subcontractors – Wisconsin Center for Education Products & Services (WCEPS), University of

Minnesota’s National Center on Educational Outcomes (NCEO), and University of Kansas’s

Center for Assessment and Accountability Research and Design (CAARD) – were selected to

carry out the following studies:

1. Alignment – Evaluate the degree to which the ACT and the SAT align with Florida content

standards and are, therefore, suitable for use in lieu of the grade 10 statewide, standardized

English Language Arts (ELA) assessment and the Algebra 1 End-of-Course (EOC)

assessment (Florida Standards Assessments, FSA).

2. Comparability – Conduct studies, research, and analyses required to determine the extent to

which ACT and SAT test results provide comparable, valid, and reliable data on student

achievement as compared to the Florida statewide assessments for all students and for each

subgroup of students.

3. Accommodations – Determine whether ACT and SAT provide testing accommodations that

permit students with disabilities and English learners the opportunity to participate in each

assessment and receive comparable benefits.

4. Accountability – Conduct analyses to determine whether ACT and SAT provide unbiased,

rational, and consistent differentiation among schools within the state’s accountability

system.

5. Peer Review – Conduct evaluations to determine whether the ACT and SAT meet the

criteria for technical quality that all statewide assessments must meet for federal assessment

peer review.

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 5

Results and Conclusions

1. Alignment (Criteria 1 and 2)

a. Algebra 1 EOC – The analysis focused on the degree to which the assessments were

aligned with the 45 Florida Algebra 1 content standards, which are a subset of the high

school Mathematics Florida Standards (MAFS). Based on the results of the test forms

analyzed, neither the SAT nor the ACT assessment is fully aligned to the Florida Algebra

1 standards. Both the ACT and SAT assessments would need to be augmented to assess

the full breadth and depth of the Algebra 1 standards as called for by federal

regulations. The analysis indicated that the ACT would need slight adjustment to attain

the minimum level of full alignment: seven or eight items would need to be added to

each ACT test form. The SAT test forms were found to have conditional alignment,

depending on the test form: One test form was found to be acceptably aligned, needing

four items added; and the other SAT test form was found to need slight adjustment,

needing seven items added to the form to attain the minimum level of full alignment

according to the criteria used in this study.

b. Grade 10 English Language Arts – The results show that the ACT would need major

adjustments—needing 10 or more items revised or replaced to be fully aligned with the

Florida Grade 10 LAFS. The SAT test forms were found to have conditional alignment,

depending on the test form: One SAT test form was found to need five items revised or

replaced for full alignment while the other SAT test form was found to need slight

adjustments—seven items revised or replaced—for full alignment.

While augmenting the ACT or SAT to gain an acceptable level of alignment is certainly

possible, augmentation adds cost and complexity to the administration of the tests, since

items used to augment a test need to be developed annually and administered

separately from the college entrance test. Without such augmentation, the ACT and

possibly SAT tests might not meet the United States Department of Education (USED)

peer review criteria for aligned tests, thus jeopardizing the federal approval of Florida’s

plan to offer choice of high school tests to its school districts.

2. Comparability (Criterion 3)

There were two significant concerns with the dataset available for analysis (students who took

both the FSA and either the ACT or SAT) in the comparability studies.

a. First, only about half of Florida’s tenth or eleventh grade students take either the ACT or the

SAT before they graduate from high school, meaning that the matched samples of students

who participated in the FSA assessments and took one or both of the college entrance tests

seriously underrepresent the full sample of FSA test-takers (presumably the lower-scoring

students that only took the FSAs).

b. Second, the data provided by the FDOE indicates that 83%of students took the Algebra 1

EOC in eighth or ninth grades, one to three years before they took the ACT or SAT (in

spring of tenth grade, fall of eleventh grade, and/or spring of eleventh grade). Large

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 6

distances between time of testing in the two tests increases measurement error as learning

likely occurred between those test administration times.

In short, the data provided for this study are neither representative of the full population of

students nor were the tests taken close enough in time to assume little to no learning occurred.

Several different statistical analyses were run to try to account for the data issues and determine

if the tests are comparable. An important analysis performed was how often students would be

placed at the same level of performance based on their scores on the three tests. The results of

this classification consistency analysis indicate that many students would be placed at different

performance levels on the three tests, some by as much as four out of the five performance

levels. Thus, districts using the FSA option may have very different results than districts using

either the ACT or SAT options. This casts serious doubt on the interchangeability of the three

tests, and the soundness of making accountability decisions based on them. At this point, it

appears the ACT and SAT do not produce results comparable to the FSA and should not be

considered alternatives to them. This also indicates that the ACT and SAT will, likely, not meet

USED peer review requirements.

3. Accommodations (Criterion 4)

This study concluded that in many ways, in terms of the provision of accommodations, the ACT

and SAT could provide comparable benefit to the FSA for purposes of school accountability and

graduation, although this was less evident on the SAT for English Learners (ELs). In general,

both the ACT and the College Board indicated that they would provide greater numbers of the

accommodations in the standard list of accommodations used in this study (previously

developed by NCEO) than were provided for the FSAs. Whether these differences were

appropriate for the Florida standards was not addressed in these studies.

Comparability in the process for accommodations requests was less clear and often relevant

more to the use of the tests for college entrance; comparability to the FSA cannot be judged here

because the FSA does not provide a score that can be used for college entrance. Still, if a district

based a decision to use one of these tests in lieu of the Florida assessments on the possibility of

having college entrance scores for all its students, this goal is unlikely to be realized for some

students with disabilities and ELs.

The lack of transparency in the decision-making process about which specific accommodations

would result in a college reportable score for which specific students is likely to result in non-

comparability for some student groups compared to other student groups, which could be a

concern when making the decision about whether to allow Florida districts to use either the

ACT or the SAT in lieu of the Florida assessments.

4. Accountability (Criterion 5)

Using the sample of students with two years of data from the FSAs and an ACT or SAT score,

simulated schools were created to examine the effects of calculating school-level indicators

using the different tests.

Overall, differences are shown across all three indicators. The results show that the numbers

going into the accountability determination would differ for many schools by the test selected.

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 7

Richer calculations can be done for ELA as there exists a state test for grades 8, 9, and 10. For

mathematics, the time at which the Algebra 1 EOC test is taken varies by students and for

many, there is no prior year score with which to base a growth calculation.

There are two important findings to consider from this accountability study: one data-based

and one more theoretical. First, the differences shown for ELA vary by type of school. Larger

schools with a greater number of lower performing students are advantaged by using the

alternate tests (ACT/SAT). This finding has implications for policy, as districts could use these

results to select a test, rather than making a more holistic determination about its students and

what test best fits the population.

Second, there will often be very different students being compared in the growth models. For

example, in mathematics, the learning gain using the FSA will be calculated based on grade 8

math and grade 9 Algebra 1. However, using the alternate test, a similar high school would be

evaluated based on the learning gain between Algebra 1 EOC in grade 10 and the ACT or SAT

in grade 11. Likewise, for the value added model, only schools using the FSAs will have a VAM

score for ELA and only some of those for mathematics. With the elimination of the FSA Grade

10 ELA and Algebra 1 EOC tests, two years of prior data will not exist for students taking the

ACT or SAT in grade 11.

Both of these findings indicate that the answer to the question on fairness is: “no – it is not fair

to compare schools that use the state tests in their accountability system to those that use the

alternate tests.”

5. Peer Review (Criterion 6)

To test the acceptability of Florida’s plan to offer its schools the option of using the ACT or SAT

in lieu of the FSAs, ASG conducted a mock peer review, using evidence provided by ACT, the

College Board, and the Florida Department of Education, as well as from ASG’s studies of

alignment, comparability, and accommodations. Experienced peer reviewers examined the

evidence and prepared written notes similar to an actual peer review. A summary of the peer

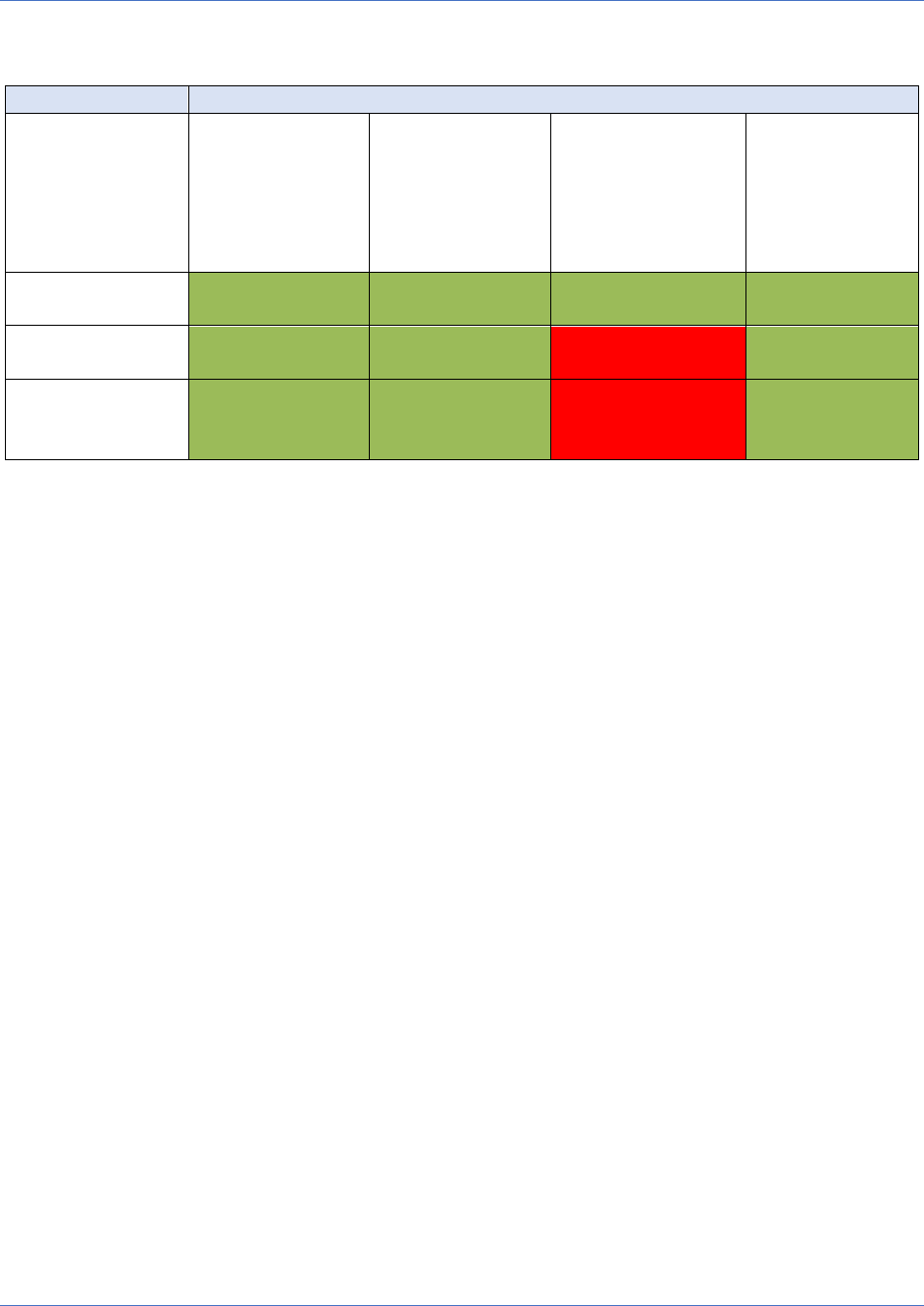

review results is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Peer Review Critical Element Determinations by College Entrance Test

Peer Review Determinations

ACT

College Board

Met Mock Peer Review Requirements

23

20

May Not Meet Mock Peer Review Requirements

1

6

Did Not Meet Mock Peer Review Requirements

6

3

TOTAL

30

29*

*One Critical Element – related to online assessment – is not applicable to the current College Board SAT.

As can be seen, the ACT was judged to not meet 6 of 30 Critical Elements, and possibly not meet

the peer review requirement for one additional element. The SAT was judged to not meet 3 of

29 peer review Critical Elements, and possibly not meet the peer review requirements for six

additional elements.

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 8

Overall Conclusion

It is the opinion of ASG and its partners that due to the alignment, comparability, and

accountability system issues associated with the ACT and SAT tests, allowing districts to pick

which of the three tests to administer to its students is not appropriate and likely will not meet

federal ESSA peer review requirements.

Detailed results from the five studies and a summary of the findings are provided in the

following sections of the report and in the Summary and Conclusions chapter at the end. Details

of the data and analyses used in the studies are provided in a separate document “Volume II –

Appendices.”

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 9

Background and

Purpose of the Project

In the 2017 Florida legislative session, HB 7069 was passed and signed into law on June 15, 2017.

The legislation states, in part:

“The Commissioner of Education shall contract for an independent study to determine

whether the SAT and ACT may be administered in lieu of the grade 10 statewide,

standardized ELA assessment and the Algebra 1 EOC assessment for high school students

consistent with federal requirements under 20 U.S.C. s. 6311(b)(2)(H). The Commissioner

shall submit a report containing the results of such review and any recommendations to the

Governor, the President of the Senate, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, and the

State Board of Education by January 1, 2018.”

The federal law referenced above is commonly known as the Every Student Succeeds Act

(ESSA). The law provides flexibility for a state to approve a school district to administer, in lieu

of the statewide high school assessment, a “locally selected,” “nationally recognized” high

school academic assessment that has been approved for use by the state, including submission

for the U.S. Department of Education’s (USED) assessment peer review process. At a minimum,

ESSA requires that the state must determine that an assessment used for this purpose meets the

following criteria:

1. Is aligned to and addresses the breadth and depth of the State’s content standards;

2. Is equivalent in its content coverage, difficulty, and quality to the statewide assessments;

3. Provides comparable, valid, and reliable data on student achievement as compared to the

Florida Standards Assessments (FSA), the statewide assessments used with all students and

each subgroup of students. Final ESSA assessment regulations of December 8, 2016, clarify

that comparability between a locally selected, nationally recognized high school academic

assessment and the statewide assessment is expected at each academic achievement level;

4. Provides accommodations that permit students with disabilities and English learners the

opportunity to participate in the assessment and receive comparable benefits;

5. Provides unbiased, rational, and consistent differentiation among schools within the state’s

accountability system; and

6. Meets the criteria for technical quality that all statewide assessments must meet (i.e., those

specified by USED’s assessment peer review).

The purpose of the project was to conduct a study to determine whether the state of Florida can

allow districts to choose to offer its students the FSAs, ACT, and SAT and still have an

assessment system that meets the above criteria.

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 10

ASG Partners and Plan of Study

In September 2017, Assessment Solutions Group (ASG) and its subcontractors were awarded

the contract under Florida RFP 2018-48: Feasibility of Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide

Assessments. The ASG Team consisted of some of the most recognized names in their respective

fields of statewide assessment and their expertise aligned perfectly with the six criteria that

Florida outlined in the RFP. The ASG team and their assigned areas of study were as follows.

The ASG individual assigned to coordinate the work is shown in parentheses for Criteria 1-5.

Criteria

Responsible Organization/(ASG Support Person)

1 and 2 – Alignment

WCEPS – Norman Webb/Sara Christopherson (Olson)

3 – Comparability

CAARD – Marianne Perie (Roeber, Olson)

4 – Accommodations

NCEO – Sheryl Lazarus/Martha Thurlow (Roeber)

5 – Accountability

CAARD – Marianne Perie (Olson)

6 – Peer Review

ASG – Ed Roeber/John Olson (Thurlow, Lazarus, Perie, Webb, and

Christopherson)

ASG Team Members

John Olson, Edward Roeber, Barry Topol

The overall work by ASG and its partners was performed collaboratively with multiple groups

working together to evaluate and respond to each of the criteria outlined in the RFP. There was

a lead group and ASG support for each criterion, thereby allowing for multiple points of review

and expertise to be brought to each area. The overall project direction and management was

provided by ASG’s Barry Topol, with technical support provided by ASG’s John Olson and Ed

Roeber.

The plan of study for each criterion is outlined below.

Criteria 1 and 2 – Alignment (Wisconsin Center for Education Products and Services)

The proposed methodology for the alignment analysis was based on processes developed and

refined by Norman Webb over the past 20 years. These processes have been used to analyze

curriculum standards and assessments in around 30 states to satisfy or to prepare to satisfy the

Title I compliance as required by the United States Department of Education (USED). Many

states that have met the USED requirements used this process to evaluate the alignment of their

standards and assessments. The alignment analysis conducted in this study was designed to

answer two key research questions:

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 11

1. How does content coverage in the ACT and SAT, for both mathematics and English

language arts (ELA), compare with the content coverage of the current Florida grade 10

statewide standardized ELA assessment and the Algebra 1 EOC assessment for students?

2. What is the degree of alignment of the ACT and the SAT with the high school Language

Arts Florida Standards (LAFS) and the mathematics Florida Standards (MAFS) with regards

to the satisfying the federal requirements within the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA)?

The proposed alignment analyses involved two stages:

• Stage I: An analysis of assessment framework documents

• Stage II: An in-person content alignment institute

The final deliverables for the work outlined were two alignment reports, one for mathematics

and one for ELA. The two reports provided findings from a reliable and replicable process

using an item-level analysis. Results described the overlap in content targeted by Florida’s FSAs

and the ACT and SAT, as well as any content unique to each assessment, considering refined

content topics and levels of content complexity. In addition, the results described the degree of

alignment of the ACT and the SAT with the Florida standards for both language arts and

mathematics.

The two final reports on alignment included a comparison of the blueprints and item

specifications, or equivalent documents, for each of the ACT, SAT, and Florida assessments to

provide more in-depth description of the content coverage by each assessment.

Criterion 3 – Comparability (Center for Assessment and Accountability Research and Design)

The main goal of the comparability analyses was to determine if the technical characteristics of

the different measures under consideration (ACT and SAT; FSAs in Grade 10 ELA and Algebra

1 EOC) would provide comparable, valid, and reliable data on student achievement, for all

students and each subgroup of students, to permit them to be used in lieu of the current FSAs in

Florida’s assessment system.

In carrying out this comparability work, the following research questions and associated

analyses were addressed:

1. How similar are item types across the three tests? Item types were evaluated to determine

whether the tests were comparable in terms of the types of items used.

2. How similar are the ranges of difficulty across the three tests at the item level? Average and

range of item difficulties of the tests were examined to see if they were significantly

different from one another.

3. How similar are the reliabilities across the three tests? Technical information for each

assessment (e.g., standard errors of measurement and internal consistency) and the overall

reliability of each measure were reviewed and compared.

4. When looking at matched samples, how similar are the distributions of performance across

the tests? Comparisons were made of the distribution of test takers by county school system

with comparable demographic information about student enrollments and, where

necessary, sub-samples of students to best represent the entire state were selected. Once

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 12

matched/representative samples were obtained (adjusted if necessary for student sub-

group underrepresentation), the performances of students on the different tests were

examined.

5. What percentage of students can be expected to be categorized into different achievement

levels with each test (and in which direction)? Comparisons were completed on whether the

same percentages of students perform in different achievement levels on each test.

6. What is the probability that a student would be placed in the same Florida category of

achievement when taking the FL test, the ACT, or the SAT? Analyses were completed to

evaluate the comparability of whether every student would be placed in the same category

of achievement on the ACT or the SAT as they are on the Florida tests.

To complete these studies, data were collected from recent ACT and College Board Technical

Reports, test files, matched datafiles from Florida, other state data (those using ACT or SAT),

and state reports of student performance and achievement level results. The intent was to build

a body of evidence to be used to evaluate the degree of comparability of the tests.

Criterion 4 – Accommodations (National Center on Education Outcomes)

The National Center on Educational Outcomes (NCEO) organized and conducted in-person

studies with Florida educators to evaluate the degree to which the ACT and SAT provide

testing accommodations that permit students with disabilities and English learners (ELs) the

opportunity to participate in each assessment and receive comparable benefits to participation

in the FSA.

NCEO staff worked with the FDOE to identify 8 panelists who had familiarity with the Florida

mathematics standards and the ways in which the FSA Algebra 1 EOC assessment is

administered to students with disabilities and ELs. Similarly, NCEO also worked with the

FDOE to identify 8 panelists who had familiarity with the Florida language arts standards and

the ways in which the FSA grade 10 ELA assessment is administered to students with

disabilities and ELs.

Each panel included a special educator (Exceptional Student Education); English language

learner educator (English for Speakers of Other Languages); blind/low-vision educator;

deaf/hard of hearing educator; and content educator. Each group of panelists went through a

systematic study process during the in-person meetings and reviewed accommodations for the

ACT, SAT, and FSAs with respect to:

1. The process and ease of signing up for accommodations

2. The availability of the accommodations themselves

3. The testing context for the accommodations provided to reach its conclusion about the

suitability of the ACT or SAT to replace the current Florida assessments of grade 10 ELA

and Algebra 1.

Criterion 5 – Accountability (Center for Assessment and Accountability Research and Design)

The accountability simulations called for in Criterion 5 were in many ways the “bottom line” of

establishing the comparability of the college entrance tests with the FSAs in ELA and Algebra 1

EOC because of the consequences for schools and districts for the performance of their

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 13

secondary students. Florida includes ELA, math, science, and social studies scores in its school

accountability system. In this study, the ACT or SAT scores substituted for the Grade 10 FSA

ELA scores or the FSA Algebra 1 EOC scores. Other achievement scores and all other variables

included in the Florida accountability system remained the same. In Florida’s A-F

accountability rating system, the ACT or SAT scores were included in the two indicators for

high schools – Achievement and Learning Gains.

Using an adjusted matched sample, CAARD replicated the procedures used by Florida to hold

schools accountable for the performance of their students in Florida’s school accountability

system. This included the substitution of the ACT- or the SAT-derived student scores for the

FSA in ELA or the Algebra 1 EOC scores.

A series of simulations were conducted using adjusted matched samples of FSA and ACT or

SAT student files. Results from the simulations were then carefully evaluated and the findings

from using ACT and SAT were compared to those for FSA ELA and Algebra 1 EOC tests that

are currently used in the accountability system reports for Florida schools. These simulations

determined whether ACT and SAT provide unbiased, rational, and consistent differentiation

among schools in Florida’s accountability system.

Criterion 6 – Peer Review (Assessment Solutions Group)

The ASG team’s approach under Criterion 6 included the following steps:

1. Summarizing current information and evidence from states that have used the ACT and the

SAT as their high school assessments on how they have addressed the requirements in the

USED peer review, in particular those Critical Elements related to alignment, test

development, accommodations, technical quality, and validity. When this research had

concluded, a determination was made that information for the College Board SAT was not

yet available, while information for the ACT preceded ESSA and its peer review elements.

2. Creating a hybrid peer review template for use by the FDOE, ACT, and the College Board to

submit their evidence of adequately addressing each peer review critical element.

3. Reviewing and commenting on each of the pieces of evidence submitted by ACT and the

College Board in support of the use of these assessments in lieu of the FSAs.

4. Providing a professional judgment on the likelihood of ACT and/or SAT, when used as an

optional high school test in place of the state’s test, being approved by USED following peer

review. This included providing comments on the strengths and weaknesses of the evidence

that was provided and recommendations on the areas where improvements or additional

evidence may be needed. Note: Not all evidence for peer review will be provided by ACT or

the College Board. There are peer review critical elements for which evidence in support of

the use of the ACT or the SAT will come from school districts after the initial administration

of these assessments in Florida’s districts. Collecting this “local-use” data will add to the

complexity of FDOE’s ultimate peer review submission to the USED.

5. Preparing the relevant parts of the actual peer review document for submission for the

Department.

ASG and its partners used a “peer review-like” process to accomplish the purposes outlined

above. The ASG team gathered evidence from the FDOE, ACT, and the College Board,

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 14

including the draft of the pertinent sections of the actual State Assessment Peer Review Submission

Cover Sheet and Index Template, the document that each state uses to submit its evidence of the

technical qualities of its proposed assessments. The peer review evidence compilation was split

into two tracks: 1) the technical criteria for the Critical Elements responded to by ACT or the

College Board, and 2) evidence related to supporting these Critical Elements from the work that

ASG and its partners carried out in Criteria 1-5.

Sections outlining the analyses conducted and conclusions reached for each of the six criteria

appear in the following sections of the report. Appendices providing detailed data and other

information appear in a separate volume of the report.

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 15

Section 1

Alignment Studies (Criteria 1 and 2)

Norman Webb and Sara Christopherson, Wisconsin Center for Education Products and Services

1A – Math Alignment Studies

Executive Summary

An alignment analysis was conducted as part of a comprehensive study to determine if Florida

school districts might be able to use a college entrance test (the ACT or the SAT) in place of the

Florida Standards Assessments (FSA): Florida’s Grade 10 Statewide Standardized ELA

Assessment and Algebra 1 end-of-course (EOC) exam. The larger study encompasses the

alignment of the three tests with Florida’s academic content standards, as well as an

examination of the accommodations offered to students with disabilities and English learners,

the statistical comparability of the measures, and potential impacts of using all three tests

interchangeably on school accountability in Florida. Together this study is designed to reveal

the degree to which the ACT or SAT could be used in lieu of the Florida Grade 10 Statewide

Standardized ELA assessment and Algebra 1 EOC assessment in fulfilling requirements as

stated in Federal statute. A separate report has been prepared to describe the alignment of the

ELA assessments of each of the three tests.

A two-part alignment study was conducted as one of a concert of investigations to answer this

question. The first stage of the alignment study compared the differences and similarities in the

frameworks used to develop or interpret the findings from the three assessments. The

framework analysis was conducted by a mathematics content expert, Professor Kristen Bieda, of

Michigan State University. The second stage of the study was a two-day alignment institute,

October 18-19, 2017, that was conducted in Orlando, Florida. Seven reviewers conducted the

analysis, five of whom were from Florida, and invited to participate from a list provided by the

Florida Department of Education, and two of whom were external reviewers from other states.

All of these reviewers had backgrounds in teaching high school mathematics or serving as a

mathematics coordinator. The project director and an additional reviewer, both with

mathematics education backgrounds, coded some of the forms. This was done to have at least a

total of five reviewers that coded each assessment form.

The analysis focused on the degree to which the assessments were aligned with the 45 Florida

Algebra 1 standards, a subset of the high school Mathematics Florida Standards (MAFS). For

use in the alignment institute, these standards were supplemented by additional ones, informed

by the framework analysis, in order to be able to describe in more detail the content targeted by

the ACT and SAT. The seven mathematics reviewers were trained in the alignment process at

the institute. The reviewers entered their data into the Web Alignment Tool version 2 (WATv2).

The degree of alignment of a test form with the corresponding standards can be considered in

terms of the degree to which specific alignment criteria are met as well as in terms of the total

number of items, if any, that would need revision or replacement for full alignment. In terms of

meeting the specific alignment criteria, both of the Florida test forms analyzed met all of the

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 16

alignment criteria for all three reporting categories with one exception: both test forms only

weakly met the criterion of Range of Knowledge (breadth) for one of the three reporting

categories (RC3 Statistics & the Number System). The ACT test forms did not have items that

corresponded to a sufficient number of standards for any of the three of the reporting categories

to be considered to have an acceptable breadth in coverage of the Algebra 1 standards. Breadth,

as measured by the Range-of-Knowledge alignment criterion, was unmet for both ACT test

forms for two reporting categories (RC1: Algebra & Modeling and RC3: Statistics and the

Number System) and was only weakly met for the third reporting category (RC2: Functions and

Modeling). The SAT test forms were found to not have items that corresponded to a sufficient

number of standards to address the breadth of expectations within RC2 or RC3.

In terms of the number of items that would need revision or replacement for full alignment,

both Florida test forms were found to be acceptably aligned—defined as needing 5 or fewer

items revised or replaced. One Florida test form was found to need only one item revised or

replaced and the other test form was found to need two items revised or replaced to meet the

minimum cutoffs for full alignment. One SAT test form was also found to be acceptably aligned,

needing four items added to meet the minimum cutoffs for full alignment. The second SAT test

form was found to need slight adjustments—defined as needing six to 10 items revised or

replaced to meet the minimum cutoffs for full alignment. That second SAT test form needed

seven items revised or replaced to meet the minimum cutoffs for full alignment with the Florida

Algebra 1 standards. Thus, alignment of the SAT was found to depend on the test form. The

analysis indicated that about seven or eight items would need to be added to the ACT to meet

the minimum cutoffs for full alignment according to the criteria used in this study.

About one-third of the ACT items and two-thirds of the SAT items corresponded to the 45

Florida Algebra 1 standards. The ACT had items that corresponded to a greater number of

standards overall, including geometry and grades 4-8 standards. The SAT had items that

corresponded to these topics as well, but in fewer numbers. The measures of agreement in

assigning depth-of-knowledge levels to assessment items and items to curriculum standards

were all in an acceptable range.

Whereas both Florida assessment forms were found to be acceptably aligned with the Algebra 1

standards, both ACT test forms were found to need some adjustments. One of the SAT test

forms was found to be acceptably aligned while the other test form was found to need slight

adjustments. Both the ACT and SAT would need to be augmented with additional items to meet

the minimum cutoffs for full alignment with the Florida Algebra 1 standards. While

augmenting the ACT or SAT to gain an acceptable level of alignment is certainly possible, it

should be noted that augmentation tends to be a rather expensive process and adds complexity

to the administration of the tests, since items used to augment a test need to be administered

separately from the college entrance test. Without such augmentation, however, these tests

might not be viewed as meeting the United States Education Department (USED) criteria for

aligned tests, thus jeopardizing the college entrance tests’ approval in the federal standards and

assessment peer review process.

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 17

Introduction and Methodology

The alignment of expectations for student learning with assessments for measuring students’

attainment of these expectations is an essential attribute for an effective standards-based

education system. Alignment is defined as the degree to which expectations and assessments

are in agreement and serve in conjunction with one another to guide an education system

toward students learning what they are expected to know and do. As such, alignment is a

quality of the relationship between expectations and assessments and not an attribute solely of

either of these two system components. Alignment describes the match between expectations

and an assessment that can be legitimately improved by changing either student expectations or

the assessments. As a relationship between two or more system components, alignment is

determined by using the multiple criteria described in detail in a National Institute for Science

Education (NISE) research monograph, Criteria for Alignment of Expectations and Assessments in

Mathematics and Science Education (Webb, 1997). The corresponding methodology used to

evaluate alignment has been refined and improved over the last 20 years, yielding a flexible,

effective, and efficient analytical approach.

This is a report of a two-stage alignment analysis in the area of mathematics that was conducted

during the month of October, 2017, to provide information that could be used to judge the

degree that the ACT or SAT meet the Criteria 1 and 2 (related to alignment, from Florida RFP

2018-48) for their suitability to be administered in lieu of Florida’s Algebra 1 end-of-course

assessment, consistent with federal requirements under 20 U.S.C.s. 6311(b)(2)(H). More

specifically, this study addressed the question of alignment between the ACT or SAT with the

Mathematics Florida Standards (MAFS) used to develop the Algebra 1 EOC assessments

administered in the spring of 2016 and 2017. As such, the study focused on the degree that the

assessments, including the current Florida Algebra 1 EOC, addressed the full depth and breadth

of the standards used to develop the Florida Algebra 1 EOC assessment. This alignment

analysis is one of a concert of studies conducted in response to the Florida RFP 2018-48

requesting proposals by August 15, 2017. A parallel alignment study was done for the ELA

assessments (described in a separate report).

The alignment analysis consisted of two stages:

• Stage I: An analysis of assessment framework documents; and

• Stage II: An in-person content alignment institute.

The Stage I framework analysis was done by mathematics education Professor Kristen Bieda, of

Michigan State University. Dr. Bieda analyzed the specification of mathematics content in

supporting documents for each of the three assessments including blueprints, item

specifications, item type, calculator policy, and other relevant materials that were used in

developing tests or interpreting scores. Her report is included as an attachment to this report

(see Appendix 1a.E). Information from her report was used to increase the number of the MAFS

included in Stage II. Although the charge for the alignment analysis was restricted to the

Mathematics Florida Algebra 1 standards, these standards were supplemented with additional

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 18

MAFS, including those in grades 4 through high school, in order to describe in more detail the

content assessed by the ACT and the SAT.

The Florida Standards are a modified version of the Common Core State Standards (CCSS). The

Common Core State Standards were developed in 2010 through the coordination of the

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices (NGA Center) and the Council of

Chief State School Officers (CCSSO). The standards were designed to provide a clear and

consistent framework to prepare pre-K through grade 12 students for college and the

workforce. The standards were written to describe the knowledge and skills students should

have within their K-12 education careers so that high school graduates will be able to succeed in

entry-level, credit-bearing academic college courses and in workforce training programs. The

CCSS have been widely used by over half of the states in the country to prepare students for

college and careers. The MAFS are nearly identical to the CCSS for mathematics and can be

considered as meeting the requirement of high quality standards related to college and career

readiness.

This study included the 45 standards identified by Florida that defined the expectations for the

Algebra 1 course. In addition, another 124 standards were added to the 45 Algebra 1 standards

to be able to have standards that would correspond to items that may be on the ACT or SAT

assessments. In particular, standards related to the topics of geometry, trigonometry, statistics,

data, and proportions were included. The eight mathematical practices standards were not used

by Florida for the Algebra 1 course and were not included in this study.

The 45 Algebra 1 standards were grouped under three reporting categories—Algebra and

Modeling (N=17); Functions and Modeling (N=15); and Statistics and the Number System

(N=13). Under the reporting categories, the standards were grouped by domain. For this

analysis, 65 additional standards from the MAFS were added to the three Algebra 1 reporting

categories along with standards grouped under two reporting categories—Geometry (N=43)

and Grades 4-8 Mathematics Standards (N=16). These additional standards were included in

the study to be able to better reflect the content included in the SAT and ACT assessments. The

framework analysis provided information that suggested that content from pre-high school

courses could appear on the assessments. These topics from grades 4-8 could be possible

predictors for college and career performance.

Stage II of the study, an in-person content alignment institute for English Language Arts (ELA)

and Algebra 1, was held over three days, October 18-20, in Orlando, Florida, at the Hyatt Place

Orlando/Buena Vista. Both ELA and Mathematics assessments were reviewed at the institute.

The content groups worked separately. The mathematics panel worked for two days, October

18 and 19. Seven reviewers served on the mathematics panel. The group leader, a retired

mathematics curriculum coordinator from Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, had served as a leader and

reviewer in numerous other alignment studies. A second external reviewer was a state

mathematics assessment coordinator who had participated in one other alignment study. Five

Florida Algebra 1 or mathematics coordinators participated as reviewers, invited from a list of

highly qualified educators provided by the Florida Department of Education. In addition,

Norman Webb (study director), whose background is in mathematics education and has

participated in a multitude of alignment studies as far back as 1996, coded four of the six

assessments. Webb also served as study director for this project. After the institute, a ninth

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 19

reviewer, a retired district mathematics coordinator who has participated in numerous

alignment studies, coded two assessments in order to have at least five reviewers analyze each

of the six assessments. A total of five to eight reviewers coded each assessment.

Study director Norman Webb is the researcher who developed the alignment study procedures

and criteria (through the National Institute for Science Education in 1997, funded by the

National Science Foundation, and in cooperation with the Council of Chief State School

Officers) that influenced the specification of alignment criteria by the U.S. Department of

Education. The Webb alignment process has been used to analyze curriculum standards and

assessments in at least 30 states to satisfy or to prepare to satisfy the Title I compliance as

required by the United States Department of Education (USED). Study Technical Director Sara

Christopherson has participated in and led Webb alignment studies since 2005, for over 20

states as well as for other entities.

The Version 2 of the Web Alignment Tool (WATv2) was used to enter all of the content analysis

codes during the institute. The WATv2 is a web-based tool connected to the server at the

Wisconsin Center for Education Research (WCER) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. It

was designed to be used with the Webb process for analyzing the alignment between

assessments and standards. Prior to the Institute, a group number was set up on the WATv2 for

each of the two panels. Each panel was assigned one or more group identification numbers and

the group leader was designated. Then the reporting categories and standards were entered

into the WATv2 along with the information for each assessment, including the number of items,

the weight (point value) given to each item, and additional comments such as the identification

number for the item to help panelists find the correct item.

Training and Coding

In the morning of the first day of the alignment institute, reviewers in both the English

Language Arts (ELA) group and the mathematics group received an overview of the purpose of

their work, the coding process, and general training on the Depth-of-Knowledge (DOK)

definitions used to describe content complexity. All reviewers had some understanding of the

DOK levels prior to the institute. The general training at the alignment institute was crafted to

contextualize the origins of DOK (to inform alignment studies of standards and assessments)

and purpose (to differentiate between and among degrees of complexity), and to highlight

common misinterpretations and misconceptions in order to help reviewers better understand

and, therefore, consistently apply the depth of knowledge (DOK) language system. Panelists

also practiced assigning DOK to sample assessment items that were selected to foster important

discussions that promote improved conceptual understanding of DOK. Appropriate training of

the panelists at the alignment institute is critical to the success of the project. A necessary

outcome of training is for panelists to have a common, calibrated understanding of the DOK

language system for describing categories of complexity.

Following the general training, the two groups went to separate rooms to receive more detailed

training on the DOK levels for each content area. For mathematics, the group discussed the

definitions for the four DOK levels for each content area. After the mathematics reviewers

attained a common understanding of the DOK definitions, they reviewed the DOK levels

assigned to the MAFS given to them. They were asked to identify any of the assigned DOK

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 20

levels they thought did not accurately depict the appropriate level of content complexity. The

group then discussed any standard identified by one or more of the reviewers. The group

decided to change the DOK level of two standards (G-SRT 4.9 from DOK 3 to 2 and G-SRT 4.10

from DOK 2 to 3). The mathematics group then coded the first five assessment items from the

Florida Algebra 1 EOC Spring 2016 assessment form. This was done to monitor that all the

reviewers understood the process and to check on their coding of items to standards. Then the

reviewers coded the remainder of the items on the Florida Algebra 1 EOC Spring 2016 form

independently.

In coding an assessment, reviewers were instructed to read the assessment item and to respond

to the question. Then they were told to determine and enter the DOK level of the item into the

WATv2 before deciding the matching standard. Next reviewers were to find the curriculum

standard from the 169 standards they were given that best represented the content knowledge

that was necessary for someone to know in order to answer the item correctly. If the reviewer

felt that the knowledge required to answer an item correctly corresponded to two distinct

standards, then they were to identify one or two additional standards. However, they were

cautioned to use additional standards only when an item truly targeted multiple standards

because doing so increased the weighting for that item.

Reviewers were instructed to consider the full statement of expectations to consider if an

assessment item should be mapped to a standard. For a reviewer to code an item to a standard,

all or nearly all, of the expected outcome as expressed in the standard had to be necessary for a

student to perform to answer the item correctly. In some cases, reviewers could make

reasonable arguments for a coding an item to different standards. If reviewers map an item to a

variety of standards it may also indicate that the assessment task may be inferred to relate to

more than one standard but that the item is not a close match.

Reviewers may have difficulty finding where an item best fits when an assessment is coded to a

set of standards that were not used in developing the assessment. If an item did not closely fit

any standard, then the reviewers were instructed to code the item to a standard where there

was a partial fit or to a generic standard (domain or reporting category level). If the item did not

match any of these, then the reviewer was instructed to indicate that the item was uncodeable.

No items were considered uncodable on any of the test forms in this review.

If reviewers did not find a standard that explicitly matched an assessment item, they were

instructed to code the item to a generic standard. A generic standard is the next level, either the

domain or the reporting category. The supplementary standards to the Algebra 1 standards

were added to reduce the number of items that would be assigned to a generic standard.

Reviewers were instructed to enter a note into the WATv2 for an assessment item to provide

additional and helpful information about the item and the corresponding standards. For

example, if the item only corresponded to a part of a standard and not the full standard,

reviewers were requested to enter the letter indicating what part of a standard was targeted.

Thus, the reviewers’ notes reveal if assessment items only targeted a part of the individual

standards (see Appendix 1a.C). Reviewers also could indicate whether there was a Source-of-

Challenge issue with an item—i.e., a problem with the item that might cause the student who

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 21

knows the material to give a wrong answer or enable someone who does not have the

knowledge being tested to answer the item correctly. After finishing coding of all of the items

on an assessment, reviewers were asked to respond to four debriefing questions. These

questions sought additional information from the reviewers about their holistic view of the

assessment, including qualitative feedback that was not captured in their standards codings,

DOK codings, or earlier notes.

Reviewers’ codings entered into the WATv2 were monitored by the project director as

reviewers were entering the data. This was done to identify any potential problems in data

entry. Once all the reviewers had completed entering data for an assessment—a DOK and

standard for each assessment item and a response to debriefing questions—the director then

identified what items should be adjudicated. The study director and group leader noted the

assessment items that did not have a majority of reviewers in agreement on standard

assignment or where the reviewers differed significantly on the DOK assigned to an item (e.g.,

three different DOK values were assigned). When these extreme disagreements occur, it

suggests that reviewers are either interpreting the DOK definitions in very different ways or are

interpreting the particular assessment item in very different ways. The WATv2 produces tables

that show the standards assigned to an item by all of the reviewers along with a table of the

DOK levels to help identify variation in coding among reviewers.

After discussing an item, the reviewers were given the option to make changes to their codings,

but were not required to make any if they thought their coding was appropriate. If an item did

not closely fit any standard, then the reviewers were instructed to code the item to a standard

where there was a partial fit or to a generic standard (domain level or reporting category). For

some items, reviewers could make reasonable arguments for coding an item to different

standards. This was particularly the case when an assessment was coded to a set of standards

that were not used to develop that assessment. In these situations, an item may measure a

general part of more than one standard, but not the more specific details that distinguish the

two standards. For example, two Florida standards both address quadratic equations: F.IF.2.4

expects students to interpret key features of graphs and tables of a quadratic equation such as

the x-intercept while A.REI.2.4 expects students to solve a quadratic equation by a number of

methods including factoring or identifying the x-intercepts. An item that requires students to

identify the x solutions from a graph of a quadratic equation could be coded to either of these

standards. It is likely such an item would not appear on an assessment that was explicitly

written to target F.IF.2.4 and A.REI.2.4.

Reviewers completed the coding of one form of the Florida Algebra 1 assessment late in the

afternoon on the first day. All of the reviewers then began coding the ACT Form 74H. The

coding of this form and the adjudication process were completed by midmorning of the second

day. At this time, reviewers were divided into smaller groups. This was done to allocate the

coding of the remaining four assessments so that at least some reviewers will have coded each

assessment. Three reviewers coded the second form of the Florida assessment (Spring 2017),

two coded the first SAT test (April 2017), and two coded the second ACT form (74C). All but

one reviewer then coded a fourth assessment. By the end of the two days allotted for coding,

eight reviewers had coded the Florida Algebra 1 EOC (Spring 2016), three reviewers had coded

the Florida Algebra 1 EOC (Spring 2017), seven reviewers had coded the ACT Form 74H, four

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 22

reviewers had coded the ACT Form 74C, four reviewers had coded the SAT April 2017 form,

and three had coded the SAT May 2017 form.

The two Florida Algebra 1 EOC assessment forms were viewed via a secure online browser on a

separate computer than the one that reviewers used to enter data into the WATv2. The online

interface required reviewers to move sequentially through the items and did not allow

reviewers to jump back and forth to check or compare items and codings. Many reviewers

found they needed to record their codings on a piece of paper, and then transfer these codings

into the WATv2. Consequently, the mathematics assessment review process took nearly double

the usual time to analyze an assessment of around 60 items (six hours rather than the planned

three hours). Reviewer coding speed varied, with the group leader coding all six forms, six of

the reviewers coding four of the forms, one reviewer coding three forms, and the extra reviewer

coding two forms. The additional reviewer was engaged after the institute in order to have at

least five reviewers for each of the six assessment forms. Eight reviewers coded at least one

form of each of the three assessments. From previous experience, reasonably high agreement

statistics are attained with five reviewers.

Data Analysis

To derive the results from the analysis, the reviewers’ responses were averaged. First, the value

for each of the four alignment criteria is computed for each individual reviewer. Then the final

reported value for each criterion is found by averaging the values across all reviewers. Any

variance among reviewers was considered legitimate; for example, the reported DOK level for

an item could fall somewhere between the two or more assigned values. Such variation could

signify a lack of clarity in how the standards were written, the robustness of an item that could

legitimately correspond to more than one standard and/or a DOK that falls in between two of

the four defined levels. After the adjudication, reviewers were not required to change their

results based on the discussion. Any large variations among reviewers in the final results

represented true differences in opinion among the reviewers and were not because of coding

error. These differences could be due to different standards targeting the same content

knowledge or may be because an item did not explicitly correspond to any standard, but could

be inferred to relate to more than one standard. Reviewers were allowed to identify one

assessment item as corresponding up to three content expectations—one primary match (the

expectation was for a single content match) and up to two secondary matches.

The results produced from the institute pertain only to the issue of alignment between the

Mathematics Florida Standards and the six assessments that were analyzed. Note that an

alignment analysis of this nature does not serve as external verification of the general quality of

the standards or assessments. Rather, only the degree of alignment is discussed in the results.

For these results, the means of the reviewers’ coding were used to determine whether the

alignment criteria were met.

Alignment Criteria Used for This Analysis

This report describes the results of an alignment study of six assessments with the MAFS for

Algebra 1 EOC supplemented by additional standards. Results are reported for the alignment of

each assessment with the MAFS for Algebra 1 EOC as well as for the alignment of each

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 23

assessment with the MAFS for Algebra 1 EOC supplemented by additional standards. Two

forms of each of the three assessments were analyzed. The study addressed specific criteria

related to the content agreement between the standards and assessments. Four criteria received

major attention:

• Categorical Concurrence,

• Depth-of-Knowledge Consistency,

• Range-of-Knowledge Correspondence, and

• Balance of Representation.

Details on the criteria and indices used for determining the degree of alignment between

standards and assessments are provided below. For each alignment criterion, an acceptable

level was defined by what would be required to assure that a student had reasonably met the

expectations within each reporting category. In the mathematics study, the Algebra 1 standards

has three reporting categories: Algebra and Modeling (RC1); Functions and Modeling (RC2);

and Statistics and the Number System (RC3). The analyses included considering the degree of

alignment of each assessment form with the 45 Algebra 1 standards under these three reporting

categories. In addition, this report describes the content coverage including standards other

than the Algebra 1 standards. In the descriptions below, the term “standards” may be used as

an umbrella term to refer to expectations in general. In addition to judging alignment between

reporting categories and assessments on the basis of the four key alignment criteria, information

is also reported on the quality of items by identifying items with Source-of-Challenge and other

issues.

Categorical Concurrence

An important aspect of alignment between standards and assessments is whether both address

the same content categories. The categorical-concurrence criterion provides a very general

indication of alignment if both documents incorporate the same content. The criterion of

categorical concurrence between standards and assessments is met if the same or consistent categories of

content appear in both documents. This criterion was judged by determining whether the

assessment included items measuring content from each conceptual category. The analysis

assumed that the assessment had to have at least six items for measuring content from a

conceptual category for an acceptable level of categorical concurrence to exist between the

conceptual category and the assessment. The number of items, six, is based on estimating the

number of items that could produce a reasonably reliable scale for estimating students’ mastery

of content for a conceptual category. Of course, many factors must be considered in determining

what a reasonable number is, including the reliability of the scale, the mean score, and cutoff

score for determining mastery. Using a procedure developed by Subkoviak (1988) and

assuming that the cutoff score is the mean and that the reliability of a single item is 0.1, it was

estimated that six items would produce an agreement coefficient of at least 0.63. This indicates

that about 63% of the group would be consistently classified as masters or non-masters if two

equivalent test administrations were employed. The agreement coefficient would increase to

0.77 if the cutoff score were increased to one standard deviation from the mean and, with a

cutoff score of 1.5 standard deviations from the mean, to 0.88.

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 24

Usually states do not report student results by standards or require students to achieve a

specified cutoff score on expectations related to a conceptual category. If a state did do this, then

the state would seek a higher agreement coefficient than 0.63. Six items were assumed as a

minimum for an assessment measuring content knowledge related to a conceptual category,

and as a basis for making some decisions about students’ knowledge of that standard. If the

mean for six items is 3 and one standard deviation is one item, then a cutoff score set at 4 would

produce an agreement coefficient of 0.77. Any fewer items with a mean of one-half of the items

would require a cutoff that would only allow a student to miss one item. This would be a very

stringent requirement, considering a reasonable standard error of measurement on the subscale.

Depth-of-Knowledge Consistency

Standards and assessments can be aligned not only on the category of content covered by each,

but also on the basis of the complexity of knowledge required by each. Depth-of-knowledge

consistency between standards and assessment indicates alignment if what is elicited from students on

the assessment is as demanding cognitively as what students are expected to know and do as stated in the

standards. For consistency to exist between the assessment and the standards, as judged in this

analysis, at least 50% of the items corresponding to a conceptual category had to be at or above

the depth-of-knowledge level of the corresponding standard; 50%, a conservative cutoff point,

is based on the assumption that a minimal passing score for any one conceptual category of 50%

or higher would require the student to successfully answer at least some items at or above the

depth-of-knowledge level of the corresponding standards. For example, assume an assessment

included six items related to one conceptual category and students were required to answer

correctly four of those items to be judged proficient—i.e., 67% of the items. If three (50%) of the

six items were at or above the depth-of-knowledge level of the corresponding expectations, then

for a student to achieve a proficient score would require the student to answer correctly at least

one item at or above the depth-of-knowledge level of one expectation. Some leeway was used in

this analysis on this criterion. If a conceptual category had between 40% and 50% of items at or

above the depth-of-knowledge levels of the expectations, then it was reported that the criterion

was “weakly” met.

DOK Levels for Mathematics

Interpreting and assigning depth-of-knowledge levels to both standards and assessment items

is an essential requirement of alignment analysis. These descriptions help to clarify what the

different levels represent in mathematics.

Level 1 (Recall)

DOK 1 is defined by the rote recall of information or performance of a simple, routine

procedure. For example, repeating a memorized fact, definition, or term; performing a simple

algorithm, rounding a number, or applying a formula are DOK 1 performances.

Performing a one-step computation or operation, executing a well-defined multi-step procedure

or a direct computational algorithm are also included in this category. Examples of well-defined

multi-step procedures include finding the mean or median or performing long division.

Reading information directly from a graph, entering data into an electronic device to derive an

answer, or simple paraphrasing are all tasks that are considered a level of complexity

comparable to recall. A student answering a DOK 1 item either knows the answer or does not:

that is, the item does not need to be “figured out” or “solved.”

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 25

At a DOK 1, problems in context are straightforward and the solution path is obvious. For

example, the problem may contain a keyword that indicates the operation needed. Other DOK 1

examples include plotting points on a coordinate system, using coordinates with the distance

formula, or drawing lines of symmetry of geometric figures.

At more advanced levels of mathematics, symbol manipulation and solving a quadratic

equation or a system of two linear equations with two unknowns are considered comparable to

recall, assuming students are expected or likely to use well-known procedures (e.g. factoring,

completing the square, substitution, or elimination) to derive a solution. Operating on

polynomials or radicals, using the laws of exponents, or simplifying rational expressions are

considered rote procedures.

Verbs should not be classified as any level without considering what the verb is acting upon or

the verb’s direct object. “Identify attributes of a polygon” is recall, but “identify the rate of change

for an exponential function” requires a more complex analysis. To describe by listing the steps

used to solve a problem is recall (i.e., Show your work) whereas to describe by providing a

mathematical argument or rationale for a solution is more complex.

Level 2 (Skills and Concepts)

DOK 2 involves engaging in some mental processing beyond a habitual response as well as

decision-making about how to approach the problem or activity. This category can require

conceptual understanding and/or demonstrating conceptual knowledge by explaining thinking

in terms of concepts.

DOK 2 tasks includes distinguishing among mathematical ideas, processing information about

the underlying structure, drawing relationships among ideas, deciding among and performing

appropriate skills, applying properties or conventions within a relevant and necessary context,

transforming among different representations, and interpreting and solving problems and/or

graphs. When given a problem statement, formulating an equation or inequality, deriving a

solution, and reporting the solution in the context of the problem fit within DOK 2. Processes

such as classifying, organizing, and estimating that involve attending to multiple attributes,

features, or properties also fall into this level.

Verifying that the number of objects in one set is larger or fewer than the number of objects in a

second set by matching pairs or forming equivalent groups is a DOK 2 activity for a

kindergartener. A first grader modeling a joining or separating situation pictorially or

physically also is at this level.

Skills and concepts include constructing a graph and interpreting the meaning of critical

features of a function, beyond just identifying or finding such features as well as describing the

effects of parameter changes. Note, however, that using a well-defined procedure to find

features of a standard function, such as the slope of a linear function with one variable or a

quadratic, is a DOK 1. Graphing higher order or irregular functions is a DOK 2. Basic

computation, as well as converting between different units of measurement, are generally a

DOK 1, but illustrating a computation by different representations (e.g., equations and a base-

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 26

ten model) to explain the results is a DOK 2. Computing measures of central tendency (applying

set procedures) is a DOK 1, but interpreting such measures for a data set within its context or

using measures to compare multiple data sets is a DOK 2. Performing original formal proofs is

beyond DOK 2, but explaining in one’s own words the reasons for an action or application of a

property is comparable to a DOK 2.

Activities at a DOK 2 are not limited only to number skills, but may involve visualization skills

(e.g., mentally rotating a 3D figure or transforming a figure) and probability skills requiring

more than simple counting (e.g., determining a sample space or probability of a compound

event). Other activities at this category include detecting or describing non-trivial patterns,

explaining the purpose and use of experimental procedures, and carrying out experimental

procedures.

Level 3 (Strategic Thinking)

DOK 3 requires reasoning and analyzing using mathematical principles, ideas, structure, and

practices. DOK 3 includes solving involved problems; conjecturing; creating novel solutions and

forms of representation; devising original proofs, mathematical arguments, and critiques of

arguments; constructing mathematical models; and forming robust inferences and predictions.

Although DOK 2 also involves some problem solving, DOK 3 includes situations that are non-

routine, more demanding, more abstract, and more complex than DOK 2. Such activities are

characterized by producing sound and valid mathematical arguments when solving problems,

verifying answers, developing a proof, or drawing inferences. Note that the sophistication of a

mathematical argument that would be considered DOK 3 depends on the prior knowledge and

experiences of the person. For example, primary school student arguments for number

problems can be a DOK 3 activity (e.g., counting number of combinations, finding shortest

route from home to school, computing with large numbers) as can abstract reasoning in

developing a logical argument by students in higher grades.

DOK 3 problems are those for which it is not evident from the first reading what is needed to

derive a solution and so require demanding reasoning to work through. Such problems usually

can be solved in different ways and may even have more than one correct solution based on

different stated assumptions. Paraphrasing in one’s own words or reproducing a proof that was

previously demonstrated is a DOK 2. Applying properties and producing arguments in proving

a theorem or identity not previously seen is a DOK 3. Also in the DOK 3 category is making

sense of the mathematics in a situation, creating a mathematical model of a situation

considering contextual constraints, deriving a new formula, designing and conducting an

experiment, and interpreting findings.

Level 4 (Extended Thinking)

DOK 4 demands are at least as complex as those of DOK 3, but a main factor that distinguishes

the two categories is the need to perform activities over days and weeks (DOK 4) rather than in

one sitting (DOK 3). The extended time that accompanies this type of activity allows for creation

of original work and requires metacognitive awareness that typically increases the complexity

of a DOK 4 task overall, in comparison with DOK 3 activities. Category 4 activities require

complex reasoning, planning, research, and verification of work. Conducting a research project,

Florida RFP 2018-48: Use of ACT and SAT in Lieu of Statewide Assessments

ASG and Partners Final Report – Florida RFP 2018-48 27

performance activity, an experiment, and a design project as well as creating a new theorem

and proof fit under Category 4.