PERFORMANCE

I

MPROVEMENT

G

UIDE

Sixth Edition

November 2014

U.S. Coast Guard .

Editors: Mr. Charlie Coiro

Christen M. Wehrenberg

CWO3 Craig Kerby

BMC William Donahue

LT Anna Hart-Wilkins

MSTC Anthony Matulonis

CWO2 Jaime Baldueza

Contributors:

CDR Robert Albright

Nancy Almeida

CWO Jaime Baldueza

CWO Michael J. Brzezicki

SCPO Robert R. Buxman

CPO John M. Callaghan

Kristy Camacho

Charles D. Coiro

Pam Dittrick

LT Alanna Dunn

CDR Frank Irr

CWO Craig Kerby

LT Jacqueline M. Leverich

Lori J. Maselli

MSTC Anthony Matulonis

Paul E. Redmond

Jason M. Siniscalchi, Ph.D

LCDR Richter L. Tipton

Christen M. Wehrenberg

Stephen B. Wehrenberg, Ph.D

Frank S. Wood

Jeff L. Wright

If this guide is used as a reference in preparing a research paper or other

publication, we suggest acknowledgement citation in the references. A

suggested bibliography entry in APA or “author (date)” style is as follows:

U.S. Coast Guard Leadership Development Center (2014).

Performance

improvement guide, 6

th

edition.

Boston, MA: U.S. Government Printing

Office.

2

Preface to Sixth Edition

The Performance Improvement Guide (PIG) is published by the

U.S. Coast Guard Leadership Development Center.

The Coast Guard strives to be the best-led and best-managed

organization in government. That’s a never-ending challenge for all

Coast Guard people. This guide is designed to help you respond to this

challenge; its contents were selected to involve employees, enhance

team effectiveness, focus problem-solving, facilitate better meeting

management, improve processes, increase customer satisfaction, and

improve overall performance to produce superior mission results.

The PIG is an ideal source of tools, processes, and models.

Organizational Performance Consultants (OPCs) and the latest

Commandant’s Performance Excellence Criteria (CPEC) Guidebook

are also valuable leadership and management resources.

The Leadership Development Center (LDC) appreciates the

improvement suggestions made by users of previous editions. Though

the PIG format remains largely the same, its contents and organization

have changed. Changes to this edition include:

• A reorganized and expanded Tools section

• Updates to examples

• Updates to wording choice and explanations to reflect the Coast

Guard’s evolution in its continuous improvement efforts

We hope you find this a useful, informative resource.

The Leadership Development Center Staff

3

CONTENTS

SIXTH EDITION .............................................................................. 1

U.S. COAST GUARD LEADERSHIP COMPETENCIES ......................... 7

LEADERSHIP RESPONSIBILITIES ..................................................... 9

SENIOR LEADERSHIP .................................................................... 10

Effective Management ............................................................ 11

Strategic Planning ................................................................... 13

DOES EVERY UNIT NEED ITS OWN STRATEGIC PLAN? ................. 14

WHY DOES A UNIT NEED ITS OWN VISION? ................................ 19

U.S. COAST GUARD CORE VALUES ............................................. 20

SWOT ANALYSIS ........................................................................ 24

GOAL WRITING PRIMER ............................................................... 25

THE BALANCED STRATEGIC PLAN ............................................... 28

TEAM LEADERSHIP ...................................................................... 31

Organizational Interface ......................................................... 33

Team Building ........................................................................ 35

Project Management ............................................................... 36

FACILITATIVE LEADERSHIP .......................................................... 39

Facilitator Behaviors ............................................................... 41

Facilitator Checklist ................................................................ 44

Facilitator Pitfalls .................................................................... 45

The Facilitative Leader ........................................................... 46

MEETING MANAGEMENT ............................................................. 47

Effective Meetings .................................................................. 47

Planning a Meeting ................................................................. 49

Agenda Checklist .................................................................... 49

Team Member Roles ............................................................... 50

Ground Rules .......................................................................... 51

Parking Lot ............................................................................. 52

Meeting Evaluation ................................................................. 54

Facilitating Using Technology ............................................... 57

GROUP LEADERSHIP .................................................................... 61

4

Stages of Group Development ................................................ 62

Managing Conflict .................................................................. 63

ORGANIZATIONAL PERFORMANCE ............................................... 64

Systems Thinking ................................................................... 65

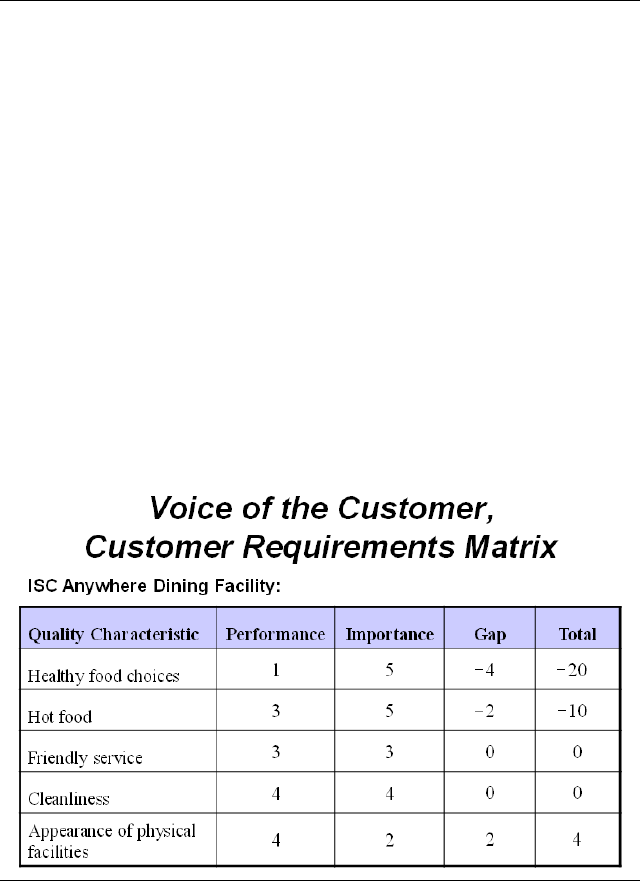

The Voice of the Customer ..................................................... 72

Work as a Process ................................................................... 74

Performance Elements ............................................................ 75

Performance Measures ............................................................ 77

Data Collection, Analysis, and Display .................................. 79

Activity-Based Costing (ABC) ............................................... 91

The Unified Performance Logic Model (UPLM) ................... 92

What to Work On .................................................................... 94

Process Improvement and Problem-Solving .......................... 95

CG Organizational Assessment Survey (CG-OAS) ............... 99

Coast Guard Business Intelligence (CGBI) .......................... 101

The Commandant’s Innovation Council ............................... 103

TOOLS ........................................................................................ 106

Action Planning .................................................................... 107

Affinity Diagram .................................................................. 109

Brainstorming ....................................................................... 113

Cause-and-Effect Diagram ................................................... 116

Charter .................................................................................. 118

Check Sheet .......................................................................... 121

Consensus Cards ................................................................... 123

Contingency Diagram ........................................................... 125

Control Charts ....................................................................... 127

Critical-to-Quality Tree (CTQ) ............................................. 129

Customer Alignment Questions ............................................ 131

Customer Requirements Matrix ............................................ 132

Decision Matrix .................................................................... 133

Flowchart .............................................................................. 135

Force Field Analysis ............................................................. 138

Gantt Chart ............................................................................ 139

Gap Analysis ......................................................................... 140

Histogram ............................................................................. 141

Kano Model .......................................................................... 144

5

Multi-Voting ......................................................................... 145

Nominal Group Technique ................................................... 147

Pareto Chart .......................................................................... 149

Project Requirements Table .................................................. 151

Project Responsibility Matrix ............................................... 152

Run Chart .............................................................................. 153

Scatter Diagram .................................................................... 158

SIPOC ................................................................................... 159

Stakeholder Analysis ............................................................ 161

SWOT Analysis .................................................................... 162

Why Technique ..................................................................... 164

Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) ...................................... 165

GLOSSARY ................................................................................. 167

REFERENCES .............................................................................. 170

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES .......................................................... 171

TABLE OF TOOL USAGE ............................................................. 173

QUICK TOOLS REFERENCE GUIDE ............................................. 175

6

U.S. COAST GUARD LEADERSHIP COMPETENCIES

The Coast Guard’s definition of Leadership is:

“You influencing (or inspiring) others to achieve a goal.”

This guide provides ideas and resources to help achieve unit and

team improvement goals. The Coast Guard uses 28 Leadership

Competencies consistent with its missions, workforce, and core

values of Honor, Respect, and Devotion to Duty. These

competencies fall into four categories:

• LEADING SELF

o Accountability and Responsibility

o Followership

o Self Awareness and Learning

o Aligning Values

o Health and Well-Being

o Personal Conduct

o Technical Proficiency

• LEADING OTHERS

o Effective Communications

o Influencing Others

o Respect for Others and Diversity Management

o Team Building

o Taking Care of People

o Mentoring

7

• LEADING PERFORMANCE AND CHANGE

o Customer Focus

o Management and Process Improvement

o Decision Making and Problem Solving

o Conflict Management

o Creativity and Innovation

o Vision Development and Implementation

• LEADING THE COAST GUARD

o Stewardship

o Technology Management

o Financial Management

o Human Resource Management

o Partnering

o External Awareness

o Entrepreneurship

o Political Savvy

o Strategic Thinking

The discussions, strategies, models, and tools in this guide

strongly support the development of most of these competencies.

For more information on the Coast Guard’s Leadership

Competencies, see

http://www.uscg.mil/leadership/resources/competencies.asp

8

LEADERSHIP RESPONSIBILITIES

Senior leaders, team leaders, and facilitators play key and support

roles in managing and improving organizational performance.

These roles include identifying important opportunities, aligning

with stakeholders, selecting the appropriate tools, planning work,

training team members, cultivating teamwork, implementing

solutions, and leading long-term change.

The following matrix outlines some key and support roles:

SL = Senior Leaders ● Key Role

TL = Team Leader ○ Support Role

FAC = Facilitator

Team Role Matrix

Role SL TL FAC Team

Manages organization

● ○

Conducts planning

● ● ○

Interfaces with organization

● ● ○

Selects team

●

Builds team

○ ● ○ ○

Manages project

○ ● ○ ○

Coordinates pre- and post-meeting logistics

● ● ○

Focuses energy of group on common task

○ ● ● ●

Encourages participation

● ● ●

Contributes ideas

● ●

Protects individuals and their ideas from attack

● ● ●

Focuses on process

○ ● ●

Remains neutral

●

Helps find win-win solutions

○ ● ● ●

The roles, responsibilities, and checklists for senior leaders, team

leaders, and facilitators presented in this guide provide a brief

overview.

9

SENIOR LEADERSHIP

Senior leaders are responsible for effective leadership and

management. Excellent organizations:

• Use management systems, tools and models to gain

insight into, and make judgments about, the effectiveness

and efficiency of their programs, processes, and people

• Determine and use indicators to measure progress toward

meeting strategic goals and objectives, gather and analyze

performance data, and use the results to drive

improvements and successfully translate strategy into

action

10

Effective Management

The Commandant’s Performance Excellence Criteria (CPEC)

provides a systematic way to improve management practices

across the organization. The criteria are based on the Malcolm

Baldrige National Performance Excellence Criteria, which are

based on core principles and practices of the highest performing

organizations in the world.

Category 6

Operations

Focus

Category 4

Measurement, Analysis,

and

Knowledge Management

Category 3

Customer

Focus

Category 1

Leadership

Category 7

Results

Category 2

Strategic

Planning

Category 5

Workfor

ce

Focus

Org

aniz

at

ional Profile:

Environment, Relationships, and Strategic Situation

Figure

1. CPEC Framework: A System’s Perspective

11

Actively using the criteria fosters Systems Thinking with a focus

on factors such as missions, customers, innovation, people,

measurement, leadership, processes, readiness, and stewardship.

The way each leader manages assigned responsibilities has

implications for the entire Coast Guard.

In other words, management matters—excellent management

practices equate to performance results. The best way leaders

can learn how the CPEC can help them accomplish command

goals is to use the system.

The criteria are built upon eleven core principles and concepts.

These principles and concepts are the foundation for integrating

key performance requirements within a results-oriented

framework. These core principles and concepts are:

• Visionary Leadership

• Customer-Driven Excellence

• Organizational and Personal Learning

• Valuing Workforce Members and Partners

• Agility

• Focus on the Future

• Managing for Innovation

• Management by Fact

• Societal Responsibility

• Focus on Results and Creating Value

• Systems Perspective

For more CPEC information, see the Commandant’s Performance

Excellence Criteria Guidebook, COMDTPUB P5224.2 (series)

https://cgportal2.uscg.mil/library/SitePages/COMDTPUB.aspx

12

Strategic Planning

Strategic planning is the process by which leaders clarify their

organization’s mission, develop a vision, articulate the values,

and establish long-, medium-, and short-term goals and strategies.

Essentially, strategic planning is the way effective leaders

prioritize organizational efforts to create unity of effort.

The strategic planning process presented in this guide is based on

the Hierarchy of Strategic Intent shown below. At the top of the

hierarchy is the organization’s mission and vision, both of which

should be long-lasting and motivating. At the base of the

hierarchy are the shorter-term strategies and tactics that unit

members use to achieve the vision.

Hierarchy of Strategic Intent

Use the Hierarchy to answer “Why the organization does X” by

looking up one level, e.g., “this set of tactical plans exists to achieve

that outcome.” Answer “how” the organization will accomplish X by

looking down one level, e.g., “strategies are how to attain the critical

success factors.”

Strategic

(Organizational)

Operational

(Area/District)

Tactical

(Sector/Unit/Team)

13

Does Every Unit Need Its Own Strategic Plan?

The traditional view of planning is that leaders at field units and individual

HQ program offices leave strategic planning to the senior-most, agency-

level leaders, as depicted here:

However, every USCG command/staff has strategic value. To ensure each

is ready to perform its assigned responsibilities, able to sustain and

improve performance, and anticipate and prepare for future needs,

planning at all levels—strategic, operational, tactical—is necessary.

There are differences in the planning scope and horizons at the national,

regional, and unit levels—perhaps 18-24 months for Cutters, 5 years for

Sectors, 5-8 years for Areas, and 20 years for the Coast Guard.

Strategic Planning process steps are listed below:

Step

1.0

Develop Guiding Documents. This includes developing

mission, vision, and values statements. If these already exist,

review them to prepare for strategic planning.

Step

2.0

Define the Strategy. This step is the heart of strategy

development; it establishes outcomes, critical success factors,

and outlines the goals to accomplish both.

Step

3.0

Develop Action Plan and Execute. This includes developing

action plans, allocating resources, and deploying the plan.

Avoid an “execution gap” by conducting action planning in a

disciplined manner and execute action plans with

accountability.

Traditional

V

iew:

Strategic

Operational

Tactical

National

Regional

Sector/Unit

Strategic

Operational

Tactical

National

Regional

Sector/Unit

The Reality:

14

SITUATION ANALYSIS AND STRATEGIC ALIGNMENT

Senior leaders: prior to strategic planning, study all the factors

that may affect the organization during its target time frame.

Align the strategic plan with efforts up and down the chain of

command to maintain a “unity of effort” or common strategic

intent.

Situation analysis focuses on the following:

• Planning Assumptions: Resource constraints, strategic

challenges, organization sustainability issues, and

emergency business continuity

• Environmental Factors: Coast Guard strategic,

operational, and tactical plans; and financial, societal,

ethical, regulatory, and technological risks

• Future Focus: Major shifts in technology, missions, or

the regulatory and competitive environments (particularly

those derived from higher echelon plans)

• Performance Metrics: Mission/operational performance

status and other key effectiveness measures

• Assessments: Organizational Assessment Survey (OAS);

Commandant’s Performance Challenge (CPC); unit

climate surveys; compliance inspection and audit

findings; strategic capability; and organizational

strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT)

15

Process Steps

DEVELOP GUIDING DOCUMENTS

Senior leaders: Begin the planning process by revisiting or

establishing organizational guiding documents, such as mission,

vision, and values statements. Since these statements are long-

lasting, they may require only slight adjustments to respond to

changes in the operational or competitive environments.

Reviewing the guiding documents reorients the planning team

toward an enhanced future state. If such documents do not exist,

they must be developed before any other planning can occur.

The essential steps in this process are:

1.1 1.2

Develop the

Vision

Review the

Values

Define the

Mission

S TEP 1 : Develop Guiding Documents

1.3

DEFINE THE MISSION

Mission refers to why an organization exists – its reason for

being or purpose. Generally, for most military organizations, the

mission is clear and unambiguous. Well-articulated mission

statements clarify:

• For members – what to expect and how they fit in

• For customers – what the products and services are

• For leaders – how to direct decision making

16

A Mission Statement must:

• Be clear and understandable

• Be brief enough for people to keep it in mind

• Be reflective of the organization’s distinctive competency

• Be broad enough to allow implementation flexibility

• Be narrow enough to maintain a sense of focus

• Be a template by which members can make decisions

• Reflect organization values, beliefs, and philosophy

DEVELOP THE MISSION STATEMENT

To develop a mission statement, leaders may facilitate the

following process with a team specifically selected for this

purpose:

1. Individually, develop a mission statement based upon the

criteria listed above

2. As a group, share individual mission statements

3. Identify common themes and must haves

4. If useful, choose and modify an individual statement

5. Devote 5-10 minutes to refine the chosen statement

6. Check the refined statement against the criteria

7. If necessary, select a sub-team to finalize the statement

offline

DEVELOP THE VISION

Vision refers to the category of intentions that are broad, all

inclusive, and forward thinking. A vision should:

• Provide aspirations for the future

• Provide a mental image of some desired future state

• Appeal to everyone’s emotions and aspirations

17

BRAINSTORM INDIVIDUAL AND COLLECTIVE LEGACY

Start by defining the organization for which the vision is being

developed. A vision can be developed for a subgroup of a larger

organization, which has a separate, broader, more inclusive

vision. Subgroup visions must be aligned with and mutually

supportive of the larger organizational vision. Ask the group to

individually list their responses to the five questions below. Tell

participants they will be asked to share their answers to Questions

4 and 5 with the group.

The Five Vision Questions

1. What do you like about being a part of this organization?

2. What do you like about the organization’s mission?

3. When it’s at its best, what do you like about the

organization?

4. What legacy would you like to leave behind?

5. What legacy should we collectively leave behind?

REPORT INDIVIDUAL RESPONSES TO THE GROUP

Once everyone has listed their responses, go around the room and

ask each participant to share his/her responses to Questions 4 and

5. The following ground rules apply:

• Speak from the heart

• Listen carefully

• Seek first to understand (ask clarifying questions only)

• Do not evaluate responses

IDENTIFY COMMON VISION THEMES

As a group, identify the common themes in the individual

responses to the questions. Has a vision or the elements of a

vision emerged? What’s missing? Facilitate discussion until all

key elements have been fully developed and are clear to all.

18

FINALIZE VISION STATEMENT OFFLINE

If necessary, select a smaller team to work offline to finalize the

vision statement. The team will use the responses and common

themes as input to develop several vision statements for the

group’s approval. The simple act of developing these concepts

within the group will provide enough direction to continue

developing the strategic plan.

Trick of the Trade: Never wordsmith in a group! That

will destroy momentum.

Why Does a Unit Need Its Own Vision?

Unit leaders often resist developing a vision statement. Many

feel that their command’s vision should match the

Commandant’s vision or the District Commander’s vision. They

are correct to the extent that a unit’s vision must be aligned with

and supportive of those higher in the chain of command;

however, many higher echelon visions are too broad or all

encompassing to be relevant to the members of a given unit.

More importantly, each unit has a specific or unique role in

successful mission execution and mission support. Leaders are

responsible for articulating that role and setting a vision to drive

improvement and higher levels of performance.

A unit vision should span a couple of CO tours or about five

years. A five-year vision is often a reach for a field unit and is

generally long enough to hold a crew’s focus. It is also a

reasonable time frame given the ever-changing nature of the

Coast Guard’s operating environment and initiatives responsive

to a given Commandant’s Intent.

19

REVIEW THE VALUES

Values are the essence of the organization. They describe who

we are and how we accomplish our work. Values affect:

• Decision making

• Risk taking

• Goal setting

• Problem solving

• Prioritization

Core Values form the foundation on which we perform work and

conduct ourselves. The values underlie how we interact with one

another and the strategies we use to fulfill our mission. Core

values are essential and enduring and cannot be compromised.

Any strategy session should review the Coast Guard’s core

values listed below. The organization’s mission and vision and

all aspects of the strategic intent should be aligned with these

values. Because the Coast Guard’s core values are so pervasive,

it is not necessary for units to develop their own; rather, assess

how/if the unit behaves consistent with and reinforces the values.

U.S. Coast Guard Core Values

H

ONOR

. Integrity is our standard. We demonstrate

uncompromising ethical conduct and moral behavior in all of our

personal actions. We are loyal and accountable to the public trust.

RESPECT. We value our diverse workforce. We treat one another

with fairness, dignity, and compassion. We encourage individual

opportunity and growth. We encourage creativity through

empowerment. We work as a team.

DEVOTION TO DUTY. We are professionals, military and civilian,

who seek responsibility, accept accountability, and are committed to

the successful achievement of our organizational goals. We exist to

serve. We serve with pride.

20

DEFINE THE STRATEGY

Defining the strategy is a leadership responsibility. While action

planning can be jointly accomplished by organizational leaders

and frontline teams, Coast Guard leaders cannot delegate strategy

development.

Developing strategy encompasses defining outcomes from the

stakeholders’ perspective, identifying critical success factors, and

developing goals for an 18- to 36-month time horizon. These

strategic plan elements lay the groundwork for all strategic

activities within the command. The following outlines essential

steps in this process.

2

.1

2.2 2.

3

Identify Critical

Success Factors

Develop Long-

Range Goals

Define

Outcomes

Step

2 :

Define the Strategy

DEFINE OUTCOMES

Outcomes are the organizational or public benefit(s) that the unit

seeks to achieve or influence:

• Outcomes identify the impact the organization has as

opposed to the activities in which it engages

• Outcomes should be derived from stakeholder

perspectives and expressed as expected results from the

organization

• Outcomes should encompass multiple stakeholder

perspectives to ensure they are “balanced”

Outcomes are not always under the full control of the

organization; many factors can influence outcomes. However, if

outcomes are well defined and continually focused upon, they

can be attained more often than not!

21

IDENTIFY STAKEHOLDERS

1. Begin by asking:

• Who has an interest in what the organization provides?

• Who cares whether the organization succeeds?

2. Ask participants to answer these questions using sticky notes

(put one stakeholder or group name on each). When finished,

randomly place the notes on chart paper or a whiteboard.

3. Ask participants to “affinitize” (see page 109-111) the

stakeholders by clustering similar notes into categories.

Attempt to create four to eight categories and name them.

4. Display these relationships in a diagram or chart.

DEFINE STAKEHOLDER EXPECTATIONS

1. Break the participants into groups and assign one previously

defined primary stakeholder to each group.

2. Ask each group to envision themselves riding an escalator on

which two members of their assigned stakeholder group are

just ahead of them. “The stakeholders do not realize you are

there and they are discussing their experience with your

organization as you’ve defined it in its enhanced future state

(vision).”

3. Ask the group, “What do you want to hear them say?”

4. Have each group report out the top two or three stakeholder

quotes that most represent a future desired outcome. Record

key items or common themes that cut across groups.

DEVELOP OUTCOMES

1. Identify five to seven common outcome themes. Assign

breakout groups to develop them into outcome statements.

Outcome statements should be measurable and directly reflect

the vision.

22

2. Ask each group to report their outcomes. Take comments,

but do not allow the group to wordsmith.

3. Assign an individual or small team to finalize the outcome

statements offline.

IDENTIFY CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS (CSFS)

CSFs are what the organization must absolutely do right, or

manage well, if it is to achieve its outcomes.

• Organizations may not control all factors leading to

outcomes; however, CSFs are wholly within their control.

CSFs generally relate to processes, people, or

technologies that enable outcome achievement.

• CSFs are leading indicators for outcomes. Successful

organizations know their CSFs and how they affect

outcomes. These causal relationships are monitored and

reinforced through a robust measurement system.

• Until cause-effect relationships are identified, CSFs are

no more than a management hypothesis based on

individual experience, theory, or background. Use

measurement to validate these hypotheses.

IDENTIFY CSFS

Develop a list of potential CSFs by asking the group:

• What must you absolutely do right or keep in control to

achieve your desired outcomes?

• What is within your ability to control?

REDUCE TO THE CRITICAL FEW CSFS

If break-out groups are used, have each group report their top

CSFs. Together, the larger group identifies common themes,

paring the list down to three to four CSFs.

23

DEVELOP LONG-RANGE GOALS

Goals are intentions that make the vision, mission, and outcomes

actionable. They typically encompass a shorter time frame than a

vision or an outcome. Goals address organization aspects,

including mission, operations, customers, processes, people, and

resources. They facilitate reasoned trade-offs and be must be

achievable. Goals usually cut across functions and can

counteract sub-optimization.

CREATING GOALS

1. Review the previously developed material.

• Outcomes – Ensure the goals are directly aligned with and

support the outcomes.

• Critical Success Factors (CSFs) – Ensure the goals

support achieving the CSFs.

• SWOT Analysis (see box and tools) – Ensure strengths

align to opportunities; establish goals to leverage

strengths to exploit opportunities; identify weaknesses

that line up with threats; establish goals that mitigate

weaknesses and consequently reduce threats.

2. Identify six to eight potential organizational goals; ensure

goals are concrete and attainable. If break-out groups are

used, have them report out goals and consolidate.

SWOT Analysis (See pg. 162)

STRENGTHS: Internal aspects of the organization that will help

achieve outcomes and CSFs.

WEAKNESSES: Internal aspects of the organization that will impede

the ability to achieve outcomes and CSFs.

OPPORTUNITIES: External events/happenings that may help achieve

outcomes and CSFs.

THREATS: External events/happenings that may impede achievement

of outcomes and CSFs.

24

AUDIT GOALS

• Ensure the goals align with higher echelon plans by

auditing them against outcomes, CSFs, and SWOT

• Ensure perspective balance among mission/operations,

customer/stakeholder, internal processes, people, and

finances/resources

• Ensure the goals meet the Goal Writing Primer criteria

Goal Writing Primer

C

REATING

G

REAT

G

OALS

!

• Avoid the tendency to create too many goals: “If

everything is important, then nothing is important.”

• Ensure goals support the mission, vision, outcomes, and

CSFs

• Ensure the why of each goal can be articulated

• Make sure the goal describes a desired state or outcome

CREATE SMART GOALS

Specific

Measurable

Action oriented

Realistic

Time based

25

DEVELOP THE ACTION PLAN AND EXECUTE

In their book Execution: The Discipline of Getting Things Done,

Larry Bossidy and Ram Charan highlight the major reason most

organizations fail in their attempts to implement strategy; they

call it the “execution gap.”

Therefore, action planning must be a component of execution.

This step in the strategic planning process is the key to

“operationalizing” the strategy that leadership has fashioned.

The best plans are worthless if they cannot be implemented. The

following outlines essential steps in this process.

3.

1

3.2

Allocate

Strategic

Resources

Monitor

Progress and

Execution

Develop

Strategies and

Tactics

S TEP 3 :

Develop the Action Plan and Execute

3.3

DEVELOP STRATEGIES AND TACTICS

Strategies and tactics are actions that can be accomplished within

a 12- to 18-month time frame. They are tied to resources,

specific milestones, and deliverables in order to be monitored for

progress/accomplishment. Strategies and tactics are not static

and may be modified as circumstances in the strategic

environment change. They must be tied closely to a goal or set of

goals in the plan and provide some strategic value to the

organization.

• Strategies are specific, quantifiable, assignable sets of

actions or projects that lead to accomplishing a goal over

a specific time period.

• Tactics are specific tasks within a strategy that can be

assigned to an individual or team to accomplish over a

short period of time.

26

DEVELOP STRATEGIES

Leadership group: involve mid-level and front-line organization

members in generating strategies that will effectively accomplish

the goals. Strategies can cover one or multiple goals. Once

identified, assign responsibility to a division or team for each

strategy to be undertaken.

DEFINE TACTICS

Strategies should be further broken down into tactics by the

responsible division or team. As the team identifies tactics, it

should consider:

W

HAT

the strategy is intended to achieve

W

HY

achievement is important

W

HO

will participate in accomplishing the strategy

H

OW

the strategy will achieve the goals

W

HEN

deliverables are needed to accomplish the strategy

ESTABLISH AN ACTION PLAN

As it formulates its list of tactics, the planning team will assign

each tactic to a work team or individual along with a milestone

date. After a few toll-gate checks and improvement cycles, the

action plan is approved by the leadership team.

27

The Balanced Strategic Plan

Comprehensive strategy and measurement balances:

• Past, present, and future performance

• Near- and long-term strategic challenges

• Strategic, operational, and tactical considerations

• Perspectives of product and service, customer

effectiveness, finances and budget, human resources, and

organizational effectiveness

A balanced strategic planning approach acknowledges that good

strategy development requires a holistic view of organizational

performance.

ALLOCATE STRATEGIC RESOURCES

To deploy the strategy, the leaders engage in a process to identify

and allocate resources for strategy execution. Recommended

methodology:

IDENTIFY NON-DISCRETIONARY FUNDING

1. The CO and the unit funds manager identify the non-

discretionary funds available for strategic projects.

2. The planning team creates the ground rules for using the

funds to execute strategic action plans.

PRESENT DIVISION ACTION PLAN

1. Division heads present their proposed actions for meeting the

goals and estimate the people and funding required to

complete the action.

2. The planning team questions the assumptions and the validity

of the proposed actions in a facilitated discussion, including

how each action may affect other divisions or planned

actions.

3. After all have spoken, the planning team breaks into sub-

teams to further refine proposals.

28

REFINE ACTION PLANS AND RESOURCES

1. When groups reconvene, the facilitator puts the plans and

resources into a strategic resource worksheet or spreadsheet

for all to see.

2. The process continues through the questioning, refining, and

reshaping cycle until consensus is reached (usually requires

three to four cycles).

3. The team leader documents the final resource allocation in

the strategic resource worksheet.

MONITORING PROGRESS AND EXECUTION

Monitoring and controlling progress involves collecting and

disseminating performance information as well as issues and

concerns that may negatively affect achieving a strategy or tactic.

Leaders and other stakeholders use this information to make

midcourse direction and resource corrections. It also provides a

fact-based method to hold individuals accountable to achieve

assigned strategies and tactics.

EXECUTING STRATEGIC PROJECTS

1. Some action may be more easily executed as a project. In

these cases, proper planning should precede any quantifiable

work. The assigned team or individual develops and

documents the plan using a project abstract, GANTT chart,

etc.

2. The responsible individual or team works closely with a

leadership champion or sponsor to ensure the project

requirements are being met and pays particular attention to

deliverables and timelines.

29

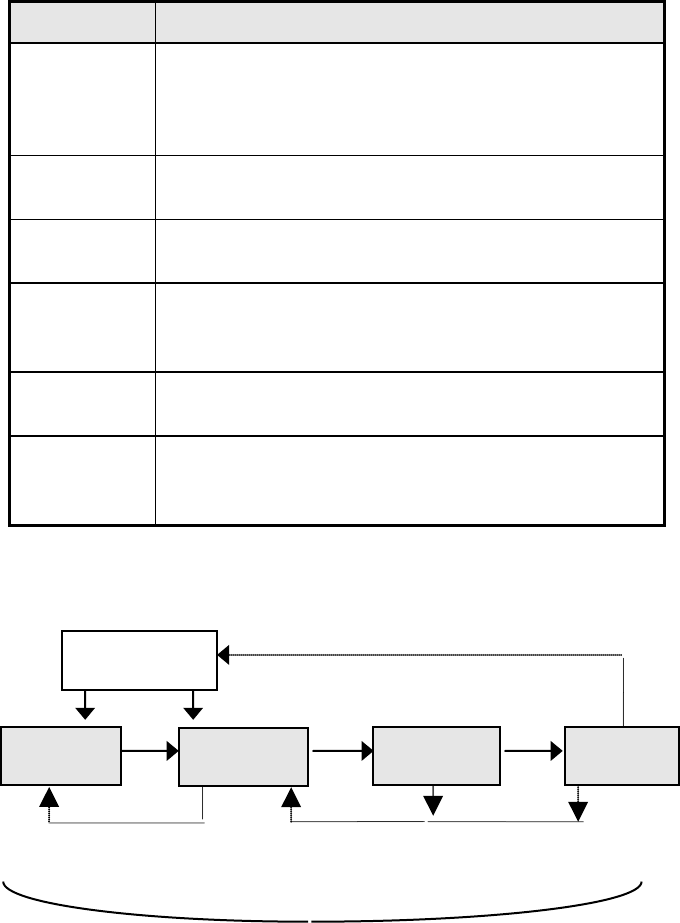

CONDUCT STRATEGY/PROGRESS REVIEW MEETINGS

1. Responsible entities are accountable for execution. They and

their leadership champions confer regularly and keep

stakeholders informed of progress.

2. Responsible entities brief leaders during regularly scheduled

strategic progress reviews. During these briefings, the

responsible person explains current status, presents any new

challenges and barriers to progress, and outlines next steps.

Midcourse corrections arising from the review session are

incorporated into the next update to the action or project plan.

Strategy drives action:

ALLOCATE

STRATEGIC

R

ESOURCES

DEVELOP

STRATEGIES &

TACTICS

DEFINE

OUTCOMES

DEVELOP LONG-

RANGE GOALS

IDENTIFY

CRITICAL

SUCCESS

F

ACTORS

DEFINE

MISSION

D

EVELOP

VISION

ESTABLISH

VALUES

RE-CYCLE QUARTERLY; ADJUST PLAN BASED ON PROGRESS

S TART

A

NNUAL

C

YCLE

QUARTERLY

C

YCLE

MONITOR

PROGRESS

3.0 DEVELOP THE ACTION PLAN*

A

ND EXECUTE

1.0 DEVELOP GUIDING DOCUMENTS

2.0 DEFINE THE STRATEGY

LONG-RANGE TO SHORT-RANGE

F INISH

OUTCOMES

CSFS

GOALS

STRATEGIES

TACTICS

RESOURCES

MISSION

VISION

VALUES

1.1 1.2

1.3

2.1 2.2 2.3

3.1 3.2

3.3

Refer to the table of tool usage for additional planning tools.

30

TEAM LEADERSHIP

Effective team leaders help inspire and focus small- to mid-size

groups (natural work groups, problem-solving teams, focus

groups, etc.) to achieve project goals. Team leaders are selected

based upon the team’s function and are typically designated in a

charter. For those on a natural work group, a team leader is

normally established by billet or position. Any team member may

be designated as team leader for a particular meeting or project

piece.

Regardless a group’s scope, effective team leaders:

• Ensure optimal team composition

• Develop stakeholder commitment

• Communicate vision

• Outline boundaries

• Give proper direction and support

• Use facilitative leadership

• Build teamwork

• Ensure accountability

While the position of being a team leader is only assigned to one

person, all team members should be ready to take on informal

leadership roles.

31

Key Roles & Tasks of Team Leader

Key Roles

of Team Leader

Tasks

Organizational

Interface

representing the project

to others

• Gain and maintain alignment with

chartering body/senior managers

• Make presentations

• Maintain written communications

• Initiate personal contact and request

feedback

• Champion performance improvement

initiatives

Team Building

using methods and

creating an environment

so each member

participates in

generating ideas,

interpreting findings,

and making decisions

• Use team-building methods. For example:

o Use warm-up activities

o Develop ground rules

o Use group idea-generation tools

o Use consensus for making decisions

o Help the team through the stages of

group development

• Cultivate full participation. For example:

o Enforce guidelines

o Negotiate and mediate

o Counsel individuals

o Adjust membership

•

Provide training in models and tools

Project Management

directing the team’s

attention to the

necessary work

• Select and manage important projects

• Align with stakeholders

• Establish scope

• Build and lead teams

• Identify work

• Create and update work plans

• Manage resources

• Monitor progress

• Review performance

32

Organizational Interface

Alignment and continuous communication with senior leadership

and other key stakeholders is crucial to running a successful

project. One essential tool is a charter (see page 118). A charter

outlines expectations from all parties, clarifies roles and

responsibilities, and aligns team efforts to organizational needs.

Some issues that the chartering body and team leader should

discuss prior to commencing the team’s activities are:

• Purpose of the charter

• Role(s) of the team leader and chartering body

• Parameters the team has to work within (time, funds,

equipment, people, and policy)

• Who has decision-making authority

• Concerns regarding accomplishing the charter objectives

• Strategies to accomplish the desired objective

In addition to the team leader, another person key to a successful

project is the champion or sponsor. For a chartered team, the

sponsor is the person who approves the charter. This person must

be high enough in the organization to address problems within

the scope of the project.

The team leader keeps the sponsor aware of progress and is

committed to team success by encouraging the sponsor to attend

meetings, discussing concerns, and informing the sponsor about:

• Team goals and project plans

• Interim findings and recommendations

• Roadblocks encountered

• Resources needed

• Milestones reached

33

Good alignment is often the difference between success and

failure. For more information on charters, see the Tools section.

Beyond the charter, team leaders ensure that the interests of

people not on the team are adequately represented. They get

commitment from people who may be affected by the team’s

actions.

Key questions to ask before putting the team together are: “Who

has a stake in the outcomes of the project? To what extent will

these stakeholders support the team’s efforts?” One effective

method of answering these questions is to conduct a stakeholder

analysis. For more information on stakeholder analysis, see the

Tools section.

34

Team Building

Team leaders select members based upon project requirements,

as well as each member’s knowledge, skills, and ability to work

as an effective team member. They continue to build the team’s

interpersonal and rational skills. Ignoring the interpersonal side

of the equation may hinder team effectiveness or, in more

extreme cases, lead to failure.

In this respect, an outside facilitator can help team leaders be

more effective. Inviting an outside facilitator allows a team leader

to focus on the content of a meeting while the facilitator helps the

group with process. Often, this split leadership approach pays

big dividends in terms of group development and success.

Some team leaders decide to facilitate their own meetings. If so,

then refer to the facilitator checklist for guidance. Be aware,

performing the roles of both team leader and facilitator can be

difficult, especially where there is passion for an issue.

Team leaders who develop good facilitation skills can foster an

environment where people remain open and engaged. Two

techniques may help:

• Listen first: Although leaders often ask for other

thoughts, subordinates or team members may simply nod

in agreement. To overcome this, ask team leaders to find

out what their co-workers think before sharing their

opinion. Set the tone by saying, “I’d like to first hear

what each of you thinks about this.”

• Acknowledge emotion: Confront emotion when it arises

and get to the facts behind it. Pretending someone isn’t

upset will close group communication. (See Managing

Conflict in the Group Leadership Section page 63.)

35

Project Management

Team leaders need a working knowledge of project management

skills. They must have expertise in teamwork, building teams,

guiding group development, and managing conflict. Knowing the

four project phases, collectively known as the project life cycle,

helps team leaders manage the overall process more effectively:

• Initiating

o Select a project

o Draft a charter

o Develop guiding statements

o Determine scope

• Planning

o Formally identify the work required

o Ensure adequate budget, personnel, and resources

o Schedule

o Assess risk

• Execution

o Manage resources

o Manage changes

o Monitor status

o Communicate

• Close-out

o Evaluate

o Develop an after action report

o Save records

o Celebrate

36

A Closer Look at Project Phases

Initiating

Before embarking on a project, ask questions such as: “Why is

this project important? What is the business case for this project?

Are there other projects with a higher priority? Will senior

leadership support this project? Will customers and other

stakeholders be happy that this project is being worked on?”

Once a project has a green light, formalize project details through

a charter. A charter can help ensure support and alignment, and

help avoid pitfalls. For more information on charters, see the

Tools section.

In order to ensure project success, senior leaders and project

managers must maintain control over project scope. Scope creep

happens when a project grows too large or becomes too difficult

to complete and can derail the best laid plans.

Project Control

• In order to maintain

control of the scope of the

project (S), you must

have control over at least

one key factor: Quality,

Cost, or Time

• Consider: What key factor

drives your project?

S

Cost

Time

Quality /

Performance

37

Planning

Planning includes identifying the work, resources, performance

requirements, and time required. Identify work by completing a

work breakdown structure (WBS) or other planning tool. Work

should be broken down to the appropriate level of detail,

typically into 80 hours or smaller segments. The 80-hour rule

helps project managers maintain control of the project by

promoting check-in after task completion. See the Tools section

for other planning tools.

Look at task dependencies in addition to the personnel, resources,

and time required. Task B is dependent upon Task A when Task

A must be completed before Task B can be started. Task

dependencies and project requirements impact the overall

timeline.

Execution

Execution means getting the work done. During execution, senior

leaders and project managers ensure communications between all

concerned parties and consider any proposed changes along the

way. Scheduling regular team briefs with key stakeholders helps

avoid problems.

Close-Out

Closing out a project properly helps teams determine how well

they met project outcomes and identifies opportunities for

improvement. By developing the ability to plan and implement

projects, managers enhance overall organizational performance.

For more project management principles beyond the scope of this

guide, see the Additional Resources Section page 171.

38

FACILITATIVE LEADERSHIP

Facilitators help teams achieve their goals through the use of

team tools, disciplined problem-solving techniques, and

continuous improvement methods. They apply good meeting

management principles, give and receive feedback, and make

adjustments.

A facilitator guides, teaches, and encourages the team. A

facilitator’s role is to help the group with process, not to

influence the content and the final product.

Facilitate:

• To make easy or easier

• To lighten the work of, assist, help

• To increase the ease of performance of

any action

Webster’s New World Dictionary

39

Key Roles & Tasks of Facilitator

Key Roles

of Facilitator

Tasks

Coach the Team

Leader

coaches the team

leader in the

process of

accomplishing the

meeting objectives

• Conduct one-on-one planning with team

leader

• Provide agenda guidance

• Provide feedback to the team leader

Facilitator

uses methods to

solicit ideas so

each member

participates in

generating ideas,

interpreting

findings,

developing

solutions, and

making decisions

• Clarify team members’ roles

• Facilitate agenda. For example:

o Warm-up exercises

o Ground rules

o Idea generation

o Decision making

o Data collection methods

o Data analysis

• Monitor sequence of model

• Focus team on task at hand

• Monitor stages of group development

• Manage group dynamics and individuals

• Cultivate cooperation. For example:

o Mediate

o Encourage

o Enforce ground rules

o Coach

Trainer

trains team

members

• Provide just in-time (JIT) training on:

o Models and tools

o Team roles and responsibilities

o Continuous improvement concepts

40

Facilitator Behaviors

The Facilitator . . .

• guides the group through a predetermined process/agenda

• encourages group members to participate

• focuses and refocuses the group on common goals and

tasks

• ensures an environment of mutual respect amongst group

members

• explains their role and how they can help the group

• assesses the group’s progress and commitment for a given

task and suggests alternative approaches as needed

• suggests agenda topics and approaches to most efficiently

and effectively help the group meet its goals

• records group ideas in a way that allows participants to

see and build on ideas

• trains group members on new tools and techniques just-

in-time

• enforces the group’s ground rules when they are violated

• energizes the group through a positive and enthusiastic

attitude

• manages conflict and helps the group find win-win

solutions

The facilitator is often a discussion moderator. In this role, the

facilitator is primarily an observer who ensures that group

members have an equal opportunity to contribute ideas and differ

with each other. When ideas are introduced in their simple form,

they often need time to take shape. While it may seem

contradictory, it is also important to allow for a healthy amount

of differing when ideas are moving along and the group seems

committed to them. This will help the group avoid the common

pitfall of “groupthink.” This term was coined to describe a state

when a group is moving along so efficiently that no one wants to

contradict or slow the momentum.

41

Another important reason to be a discussion moderator is that

there are usually equal numbers of introverts and extroverts in

any group. Extroverts often thrive in group settings because they

find it natural to think aloud and build on other people’s ideas.

Introverts are often at a disadvantage in most group settings

because they are usually more reflective and hesitant to shout out

ideas. They like to have extra time to process information.

Excellent facilitators realize this and make adjustments to

maximize the contributions of introverts while not slowing down

the contributions of the extroverts.

Several facilitator behaviors help to encourage participation and

protect ideas:

• Gate opening: Provide quiet individuals the opportunity to

participate. Some people will not cut another person off and

will wait for a quiet moment before speaking. In some

meetings, there are little to no quiet moments. Create an

opportunity by using techniques such as silent brainstorming

(writing down ideas individually before discussing them).

Note: Many introverts do not like to be called out or put on

the spot, so ask the question before calling on someone or

having a volunteer answer.

• Safe guarding: Ensure that individuals have a chance to

finish their thoughts. When ideas begin to flow quickly, some

members begin before others have finished. Not everyone has

the ability to present a complete and polished thought off the

top of their head. Safe-guarding might sound like: “Before we

move ahead, let’s give Petty Officer Gonzales a chance to

finish her thought.”

• Harmonizing: Make efforts to reconcile differences, look

for where ideas or opinions are similar, or downplay

disagreements and strong negative statements. Harmonizing

might sound like: “There seems to be a lot of passion here;

42

can we agree that we all want to achieve the same goal and

calmly discuss the different options for going about it?”

• Observing and Commenting: Provide verbal feedback to

the group/team concerning the interaction of the group/team

members, or the process/structure by which the group/team is

proceeding to accomplish its purpose. Feedback may sound

like, “There are a lot of different options being brought up.

I’d like to suggest we try capturing some of those ideas on

paper, and spend some time discussing each one so that we

can prioritize action items and next steps.”

43

Facilitator Checklist

Use the following checklist to align with senior leadership, plan

effectively, conduct productive meetings, and ensure action and

follow up.

Prior to Alignment Meeting

Research information on

group

Consider possible warm-ups

Gather reference material

(PIG, etc.)

Review tools

Prepare a contract

Arrange meeting with team

leader

Alignment Meeting

Review relevant meeting

documents and—modify as

appropriate

Establish purpose, goal,

and/or desired outcome

Determine scope

Get background information

on team

o Consider optimal size,

composition, and

representation

Develop an agenda (see

Agenda Checklist in the

Meeting Management

section)

Before Meeting

Gather supplies

Ensure room is set up in a

way that maximizes

collaboration opportunities.

During Meeting

Review agenda—modify as

appropriate

Establish or review:

o Roles

o Secondary facilitation

o Ground rules

o Parking lot

o Group expectations

Conduct warm-up activity or

icebreaker as appropriate

Conduct meeting

o Follow agenda

o Use timekeeper

o Monitor group dynamics

o Demonstrate facilitative

leadership

o Record group memory

o Use tools appropriately

o Check parking lot

Close meeting

o Develop action plan

o Review accomplishments

o Review agenda

o Clear parking lot

o Develop future meeting plans

o Conduct meeting evaluation

After Meeting

Discuss meeting evaluation with

team leader

Follow up on contract

Ensure action plans and minutes

are developed

Develop plan for next meeting

44

Facilitator Pitfalls

Avoid some of the common mistakes many novice facilitators

make:

• Taking sides or displaying bias on an issue the group is

discussing

• Having favorites in the group

• Passing judgment on ideas that are generated by group

members

• Contributing ideas without prior group approval

• Being inflexible to the changing needs of the group

• Being the center of attention

• Talking too much

• Taking on responsibility rather than allowing the

group/team to be responsible for doing the work needed

to accomplish the objective

45

The Facilitative Leader

Often a group has no formal facilitator assigned. This is common

in the Coast Guard because people are busy and can rarely

dedicate themselves full time to a group outside their usual job

functions. Realizing the benefits of the facilitator role, team

leaders are encouraged to take on some or all of the facilitative

behaviors mentioned previously. While this can be a challenge,

the best team leaders do this naturally. They already know where

they stand on an issue and are committed to getting ideas from

their team, for often these are the ideas from the workers who are

most likely to implement them.

Note: It’s important that those who have dual roles as team leader

and facilitator let the team know when they are stepping out of

one role and into the other.

46

MEETING MANAGEMENT

Good meetings are key to good management; they allow effective

processing and sharing of information. However, meetings are

often ineffective and inefficient. They waste time and resources

and cause frustration, low morale, and poor performance. To

create an environment that promotes effective meetings, team

leaders and facilitators must manage many different dynamics.

Effective Meetings

Regardless of the purpose of a meeting, effective meetings have

many of the same ingredients:

• A focus on what needs to be done

• A focus on how it can best be accomplished

• A focused goal/clear outcomes

• A focused agenda with specific time allotments

• Clear roles, responsibilities, and standards of behavior

• Balanced communications and participation

• Evaluation of meeting effectiveness

47

In order to manage meetings successfully, apply the PACER

technique, which stands for Purpose, Agenda, Code of Conduct,

Expectations, and Roles.

• Purpose

o What is the desired outcome

• Agenda

o Date and location

o Start and end times

o Time allotted for each item

o Time allotted for meeting evaluation

• Code of Conduct

o Ground rules

o Parking Lot

• Expectations

o Preparation and work required

• Roles

o Assigned roles (team leader, facilitator, recorder,

timekeeper, etc.)

o Others responsible for meeting content, setup, etc.

48

Planning a Meeting

Successful meetings require proper planning. A good rule of

thumb is to spend one hour planning for each hour of meeting

time. Sometimes more time may be spent planning a meeting

than actually conducting it.

There are numerous formats for an agenda. The following

checklist contains some of the most typically found items:

Agenda Checklist

Answer these questions before developing the agenda:

• What is the purpose and desired outcome(s)?

• Is a meeting necessary to achieve the desired outcomes?

• Who should attend? Invite the minimum number of

people required to achieve the desired outcome.

Develop agenda. An agenda should include:

Date, starting, and ending times

Location

Purpose of the meeting

Desired outcomes

Ground rules (develop or review)

Agenda items. For example:

• Warm-up exercises

• Review previous meeting’s minutes

• Mission review

• Model and/or tool selection

• Assignments & scheduling

• Progress report/status

• Report of findings

• Interpretation of findings

• Next steps

• Organizational communications

• Presentations

• Just-in-time training

Person responsible for each item

Time allotted for each item

Assigned roles (team leader, facilitator, recorder, timekeeper)

Time for meeting evaluation

49

Team Member Roles

Many facilitators and team leaders find success in sharing

responsibility for the group’s success using the following roles:

• Timekeeper

o Keeps track of time

o Notifies group when designated times have been

reached

• Scribe

o Stays out of content

o Records group ideas and decisions

o Does not edit

• Recorder

o Records and routes meeting minutes

o Captures info so that non-attendees can follow the

group’s train of thought

• Co-Facilitator

o Assists the Facilitator in the meeting process

• Participant

o Gives input, ideas, opinions

o Listens to others

o Clarifies

o Uses good team process skills

• Subject Matter Expert (SME)

50

Ground Rules

Ground rules reflect team values and create an environment for

achieving common goals. They clarify responsibilities, describe

how meetings will be run, and express how decisions will be

made.

Ground rules allow facilitators, team leaders, and groups to hold

their own feet to their own fire. For ground rules to be effective,

follow these simple rules:

1. Develop ground rules during the first meeting and get

consensus.

2. Remind the group that everyone is responsible for group

behavior.

3. Revisit them regularly -- they are living documents that

may be changed or added to as groups mature.

4. Ask the group to periodically gauge their own

effectiveness and make corrections as needed.

Sample Ground Rules

We’re here for the same purpose; we respect each other

It’s okay to disagree

Share all relevant information

Solicit others’ ideas

Listen as an ally

Everyone participates, no one person dominates

Share responsibility

Honor time limits; start on time

Base decisions upon data whenever possible

Choose right decisions over quick decisions

Strive for consensus

51

Parking Lot

One of the most effective tools a group can use to keep a meeting

on track is a parking lot. A parking lot is a place where issues

that are important but not relevant to the topic at hand can be

parked out of the congestion of discussion. Issues can be brought

back in to the discussion, when appropriate, or reviewed at a later

time. A parking lot serves as a visual reminder that each idea is

important and will not be lost or ignored.

At the beginning of a session:

Post a blank piece of chart paper on the wall and write “Parking

Lot” across the top. Place the parking lot near a room exit. This

will serve as a reminder and allow people to post any off-topic

thoughts they might have as they go on break. During the session

warm-up, possibly during or just after a discussion of ground

rules, discuss the concept of a parking lot and how to use it.

During a session:

If the group strays from the agenda, ask the group if they would

like to spend more time discussing the issue or place in the

parking lot. Ask the person who initiated the issue to write it up

using one “sticky note” per thought. Ensure that the parking lot

is cleared at regular, agreed upon intervals.

At the end of a session:

Meeting discussions are typically not held simply for discussions

sake, so follow up is key. Review parking lot items at the end of

each session. Like other parking lots, a meeting parking lot can

be the last place to focus on before departing and leaving the

discussion behind. In this way, the group can ensure that

important thoughts are not lost. To review, simply read each

item and ask, “Has this issue been addressed or is further

discussion and/or follow-up needed?” If the group desires further

discussion, coordinate an appropriate time. Get confirmation

from the group on the disposition of each item.

52

IDA Boards

A related concept is to break the parking lot into different parking

boards. One tactic is to use three boards labeled “Issues,

Decisions, and Actions” often referred to as “IDA.” The IDA

method can help groups to effectively convert discussion into

action and document meeting outcomes.

• The Issues board is like a standard parking lot. It consists

of those slightly off topic or extraneous issues that come

up during the meeting discussion. The issues list could

also contain those issues that are “out of reach” but need

attention (these items may be later documented under

Decisions or Actions).

• The Decisions board simply documents decisions made

by the group during the course of the meeting.

• The Actions board is for next steps related to each issue

and/or decision.

As with other parking lots, end-of-meeting review is important.

• When reviewing each issue on the list, ask: “Have we

covered it?” “Do we need to cover it?” and “When should

time be spent covering it?”

• When reviewing the decisions list, the opportunity exists

to dig deeper, look at each decision, and ask, “What is the

change or benefit of this decision?” Groups might also

take time to review and discuss each decision to gauge

and set the expectation for follow-through.

• The actions list contains the overall impact of the

meeting. In reviewing the actions list, assign specific

steps, names, dates, and reporting/follow-up for each

item. (See Action Planning page 107.)

53

Meeting Evaluation

To improve team and meeting effectiveness, there must be a

continuous cycle of evaluation and action planning. Evaluation

methods include round robin and consensus discussions, a

plus/delta, and meeting surveys. While participative discussion

following a facilitated meeting can be the best source of

actionable feedback for the facilitator, not every group is eager to

discuss their own improvement opportunities. Effective methods

to obtain feedback are a plus/delta and meeting surveys.

Plus/Delta

A plus/delta can help a team identify what went well along with

opportunities for improvement. It typically takes place after a

meeting review and any closing remarks.

To perform a plus/delta, first ensure that each participant has

access to sticky notes and a pen (a fine-tip permanent marker

works well in this case). Draw two columns on chart paper as

illustrated below. Label one column “+” and the other “Δ” (the

Greek symbol for delta – meaning change).

+

∆

Good discussion

Detailed agenda

Facilitator kept meeting on track

Meeting ended on time

Time keeper needs to provide more

frequent updates

Send out pre-reads earlier

Stay focused; use our parking lot

more

Ask each participant to take two sticky notes and a “+” on one

and a “Δ” on the other. On the plus, have them provide a

comment on something they thought went well and should be

continued. On the delta, have them provide a comment on

54

something that perhaps did not go well and could be improved

for the next meeting. Emphasize that the delta symbol indicates

change; in this case what is being asked for is a specific way to

improve. A meeting delta could include a request for an

additional resource like new instructional material or more

explanation of a decision-making tool or an overall process

improvement suggestion. A delta is constructive criticism that is

95% constructive and only 5% criticism. The goal behind

writing a delta statement should highlight an opportunity for

improvement and propose a solution or a corrective course of

action.

Typically, participants are most comfortable when the plus/delta

chart is placed near the door so they can post their notes (without

names) in the appropriate column as they leave the room while

going on break or following the meeting. At some point,

however, the group should review the feedback and create an

action plan for improvement.

Feedback is of little worth if it is not seriously considered and

followed up on. Work to ensure that strengths listed in the plus

column will continue in future meetings. Address legitimate

concerns and work on deltas so they can become pluses in future

meetings.

55

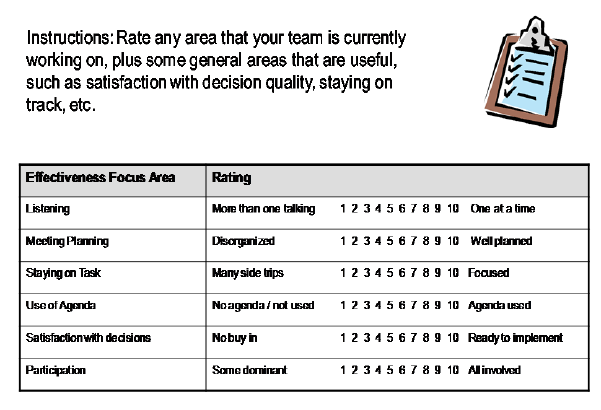

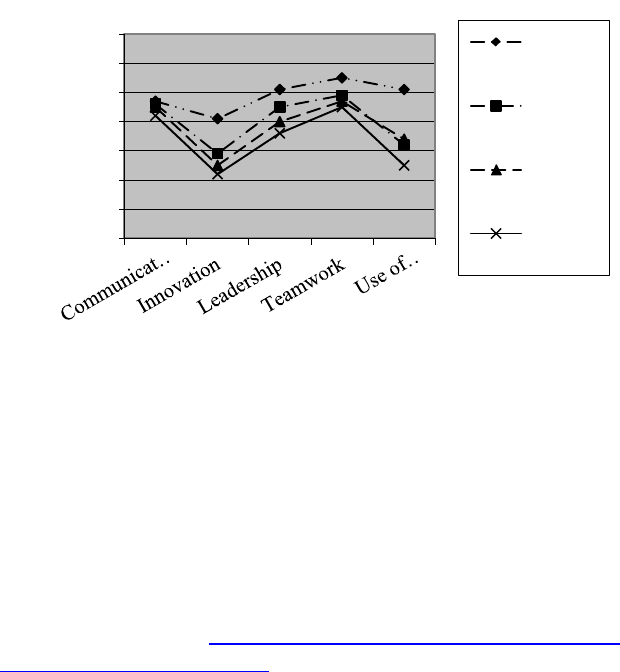

Meeting Surveys

Meeting surveys provide the benefit of quantitative measurement

of meeting performance, as well as specific focus areas that

groups sometimes avoid discussing, such as interpersonal skills.

Using meeting surveys can help groups track their progress over

time and diagnose specific factors that hinder group performance.

Surveys such as the one below tend to be more effective if

completed anonymously and compiled by a trusted party, perhaps

an outside facilitator. Asking participants to provide written

comments regarding their ratings can help group’s link specific

behaviors to ratings. Once results have been compiled, they

should be shared with the group. The group can then analyze the

data and formulate specific action plans for improvement.

56

Facilitating Using Technology

Facilitate CG teams with technology to:

• Help groups at different sites work together at the same

time (e.g., Live Meeting)

• Change the dynamics of a group in crisis or conflict (after

trying traditional conflict resolution strategies)

• Help a “stuck” group regain creativity

• Increase group productivity and speed

• Make up-to-the-minute edits and documentation

• Quantify qualitative information

• Facilitate anonymous feedback (e.g., Vovici surveys)

Match the Need and the Technology

Key Questions to Answer

• What is the group trying to accomplish?

• How simple or complex is the group’s task?

• How unified is the group?

CG Group Technology Categories

• Videoconferencing

• On-line groupware

• Audio teleconferencing

• Audience-response systems

Pre-Session Work

Make sure you get answers to the following:

• Does everyone realize that using technology may increase

the preparation time for the session?

• Do you have group buy-in for using technology

(especially audience response systems) from

management?

• Has the group (or a majority of the members) used this

technology before? Was it a good experience? If the

experience was bad, what went wrong?

57

• Does the technology present too much of a challenge for

the group members’ sensory capabilities such as

language, hearing, sight, etc.

• Can you set up and test the technology? Can you test it

with an invited group?

• Will you have help with co-facilitators or technology

operators? Can you coordinate the roles and

responsibilities?

Keys to Success with Videoconferencing

• Keep remote-site participants plugged in and in tune since

they will not be able to pick up on all of the nonverbal

cues of the main group. Openly stating the main group’s

thinking and feeling will help.

• Video is the best technology for facilitating “town hall”

meetings where groups at different sites are linked but

only a few individuals need to be speaking rather than

instances when multiple individuals from multiple

locations will need to talk with each other.

• Combine facilitating groups from various locations that

need to see not only each other but also drawings, product

samples, and other items. This can be done with large

chart paper angled toward video cameras, or with

electronic white boards that document group output in

real-time and display at multiple sites.

Keys to Success with Online Groupware

• Participants need to be keyboard-literate and comfortable

using the technology.

• Stay involved at your keyboard. Jump in with comments

to let the group know they’re on the right track.

• Keep the discussion focused and break the task down into

manageable parts. Remember: with distance technology,

simple is better.

58

Keys to Success with Audio Teleconferencing

• Call roll to identify who is present at the conference.

• Review the purpose of the conference call and the agenda.

Before the call, email agendas to everyone on the call.

• Set ground rules like in a regular facilitated meeting

(respect others, only one person speaking at a time, etc).

Ask participants to identify themselves before speaking