THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FAM ILY TYPE

AND FERTILITY

KANTI PAKRASI

AND

CHITTARANJAN MALAKER

The large increase in the total population of India between 1951

and 1961 has been correctly described as “phenomenal.” 1 The prob

ability of success of any developmental measure initiated in India

must be appraised against the immediate background of staggering

population growth. The Planning Commission is anxious for a sub

stantial reduction in the population so that the Five Year Plans of

the country will have a genuine chance for success. Great effort and

enormous amounts of money are being expended to strike at the

root of problem of population increase.

In keeping with this situation, researchers are striving to sift out

the factors responsible for the conspicuous fertility differentials

among the general population. The fertility of Indian couples of

different social and economic strata have been subjected to meticu

lous investigation. Several studies have been carried out in different

parts of India to pinpoint the role of several cultural, economic and

demographic variables assumed to induce the high birth rate.2

The results of these studies serve to point out differences in fer

tility according to socioeconomic status and geographic location, the

major cultural and demographic factors associated with high or low

reproduction and the effect of deliberate limitation of reproduction.

The evidence now available, however, does not offer any clue to

451

understanding the persistent 2.2 per cent annual population growth

in India. The stage at which controlled fertility affects fertility dif

ferentials is yet to begin in the under-developed societies in the

country.3

During the past two decades population experts have focused their

attention on the rapid and massive population growth in India.

Davis4 attempted an exposition of fertility on the basis of rural-

urban, class and religious differentials to evaluate the prospects for

an early decline. Chandrasekhar5 pointed out various sociological

factors that were presumed to influence the population increase. He

commented that “the very low level of living, the absence of a pro

longed period of education or training, the existing social attitudes

that encourage a large family, the joint family, the want of nation

wide contraceptive clinical service, and above all, the psychological

reason that encourages every man to look to his wife and sex inti

macy as the only relaxation and recreation in an otherwise dull and

unexciting life of a relentless struggle to make both ends meet—all

these are contributing factors.” Thus the sociological factors asso

ciated with high fertility in Indian families have already been

highlighted, and this may provide a proper perspective for future

demographic research. Because reproduction is one of the primary

functions of the family, the organizational pattern of the family itself

is of special significance in the study of fertility, particularly within

the traditional establishment of Asian society.

Kiser and Whelpton6 have so well established the value of study

ing fertility patterns in terms of the socioeconomic status of the

couples concerned that this variable has become an essential ingre

dient in later fertility studies. In defining socioeconomic status, how

ever, the attribute of family orientation of the couples under investi

gation was given hardly any consideration. Factors such as annual

earnings, occupation, education, monthly rental value, food habits,

place of work, attitude on birth control and children’s future edu

cation have frequently been employed to measure the behavior to

ward reproduction. The crucial factor in the relationship between

fertility and the kind of family in which the couple lives, acts and

452

procreates, with all familial prerogatives and obligations, has yet

to receive the attention and utilization merited by its importance.

That the role of the family is immediately related to the repro

duction functions of couples living in nonindustrial and agrarian

societies has already been stressed.7 Lorimer8 was one of the few

pioneers to indicate the significance of that social truth when he

dwelt upon the relation of cultural conditions to fertility. According

to him, large, cohesive families in an Asiatic society serve not only

to protect prestige and collective economic security, but also to

provide the constituent members with a “source of deep emotional

security.” The cultural context of this society is such that the families

representing “group family life” are commonly “idealized” and,

according to Lorimer, are “likely to be conducive to high fertility.”

His explanation for high reproduction rates in large, cohesive fam

ilies, including traditional joint (extended) units, remains to be

substantiated by empirical findings from the contemporary rural

or urban societies of India.

The academic and professional interest shown by experts con

tinues in their search for the probable interrelations between various

social and demographic factors, including the factor of family struc

ture and human fertility.9

Following Lorimer, demographers extended their efforts to point

out various “cultural barriers” against fertility reduction, particularly

in underdeveloped societies.10 As to the nature of such a barrier in

India, “The relation of the family pattern to birth rate is obvious.

In large traditional families such as the joint family in India . . .

the normal economic deterrents against the arrival of that extra

baby do not operate.” 11 The primary contention of Chandrasekhar

appears to be that the large family units (extended or joint) in

India are culturally equipped to accommodate any “ extra baby”

of the young parents, and thus serve as “ an incentive to higher

birth rate.” In agreement with him are the views of Davis12 who

also had the occasion to correlate the pattern of joint family estab

lishment with the high rate of reproduction in the peasant-agricul

tural societies of the underdeveloped areas of the world.

453

Other recent studies13 have focused on the relationship between

the extended (joint) type of family pattern and high fertility. These

studies have been initiated in several different types of communities

in different states in India, and the data from the studies indicate

that the women living in joint families are less fertile than are those

in simple (nuclear) families. The connection between extended

(joint) families and high fertility is, thus, a controversial but exciting

issue.

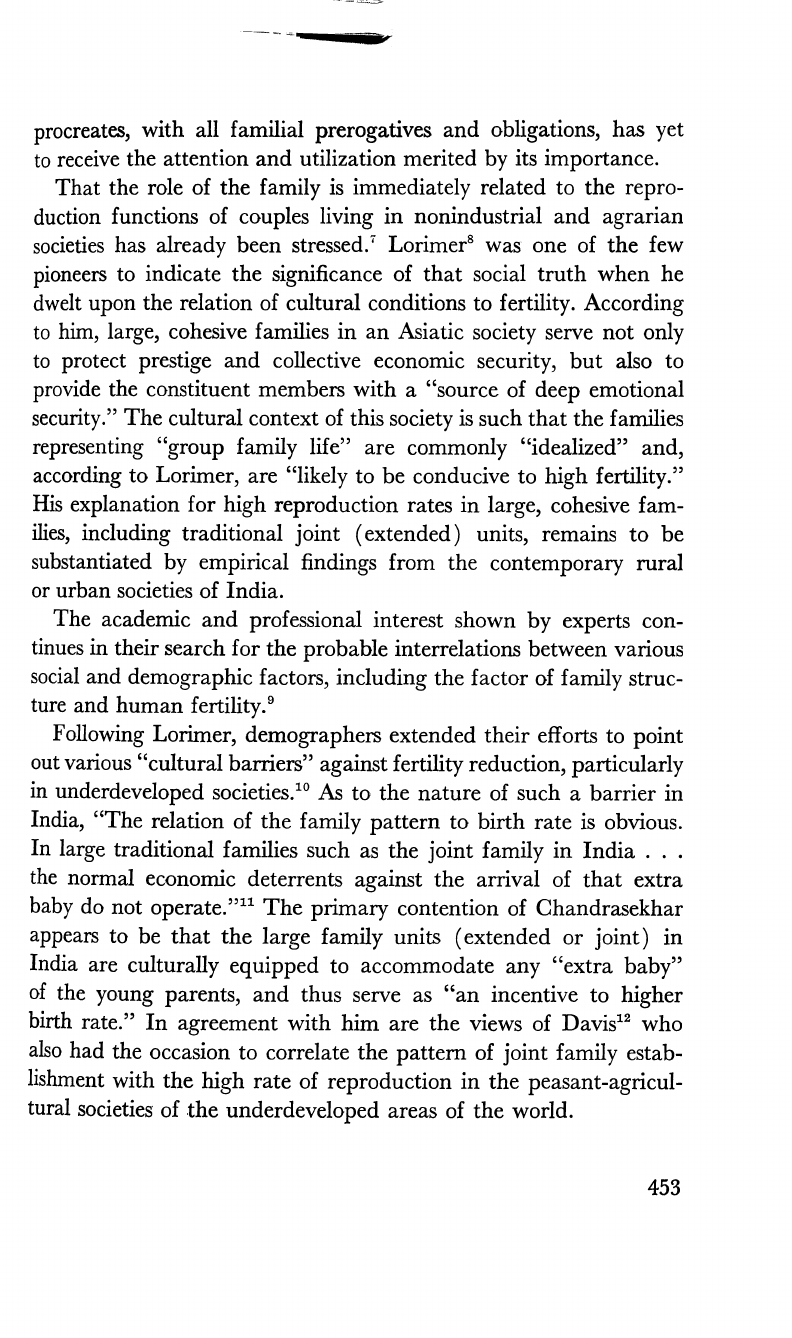

A study has been made to determine “whether the joint families in

contemporary Indian setting have actually higher fertility than the

single families.” 14 The conclusion reached is that for each one of

three Hindu and three Muslim groups of rural West Bengal, “the

average number of children in joint families is less than that in sim

ple families when women of all ages are considered. This is also

true for the majority of age categories of women.” The author ad

mitted that the observed differences on the average are “quite small

and are not likely to be statistically significant.” Nevertheless, the

study deserves commendation since it attempts to cope with the

problem by utilizing empirical data on Bengali women of seven

villages of the state. Data accumulated in this paper have their own

importance to interested researchers, even though the method em

ployed to analyze the data is not strong enough to establish a sta

tistically sound conclusion about the problem in question. Standard

ized averages should have been calculated to indicate the nature of

actual differences in fertility of the women belonging to joint or

simple families. As Table 1 shows, the results of such calculations

indicate that fertility differentials of the women belonging to joint

and simple families within a social group do not appear to be widely

fluctuating.

The intrinsic fertility performance of women varies from age to

age. For that reason, simple averages, as are given in the Nag pa

per,14 do not indicate the true fertility performance of the group or

the fertility differentials between groups because of the difference in

the proportion of women in the different age groups. Comparison of

the standardized averages in Table 1 shows that the differentials

diminish to an appreciable extent. Fertility differentials should be

454

TABLE I. AVERAGE NUM BER OP CHILDREN BORN TO RU RAL BENGALI

WOMEN IN SIMPLE AND JOINT FAM ILIES, ALL AGES, STANDARDIZED AND

UNSTANDARDIZED FIGURES.

Social Groups

Hindu Satchasi

Hindu Brahmin and Ghose Other Hindus

Standard- Unstand- Standard- Unstand- Standard- Unstand-

Family

ized

ardized ized ardized ized ardized

Type

Figure Figure

Figure

Figure Figure Figure

Simple

4.32 4.66

4.04

4.17

3.32

3.75

Average age

of women

32

29 29

Joint

3.93

3.82 3.97 3.89 3.31

3.02

Average age

of women

32 28 29

Sheik Muslim

Non-Sheik Muslim

Muslim Fishermen

Simple

4.74

5.00

3.04

3.33

2.26

2.33

Average age

of women

32

28 28

Joint

4.54

4.29 2.76

2.46

2.40 1.98

Average age

of women

30 26

24

Source: United Nations World Population Conference, Family Type and Fertility, 1965, Table 1.

interpreted by taking into consideration the differences in the average

ages of the women for different groups.

Because of the variation in the age at marriage for different castes

and religious subgroups, marriage duration15 appears to be a more

satisfactory norm for measuring fertility performances and their dif

ferentials. The factor of marriage duration helps to negate the vari

able of age difference between husband and wife.

To study the relationship between family type and fertility, an

other set of data was utilized that was collected from urban families

of West Bengal. Families were selected from different areas of Cal

cutta. Composition of each family was carefully noted along with

other characteristics— marital status, age, residential status, occupa

tion and education— of the constituent members. For the fertility

investigation, 1,018 couples from three major socioeconomic groups

were studied in detail to gather a complete fertility history of each

couple.16 Results are shown in Table 2.

455

TABLE 2. DISTRIBUTION OP SIMPLE AND JOINT FAMILIES BY DURATION

OP MARRIAGE AND SOCIAL STRATA AMONG THE POPULATION OF CAL

CUTTA, WEST BENGAL, 1956- 57.

Social Class

and Family

0-4

Duration of Marriage

5-9 10-14

15 years

All

Type

years

years

years and above

Durations

Class I

Simple

29.4%

43.9%

47.2% 50.6%

42.8 %

Joint

70.6%

56.1% 52.8%

49.4%

57.2%

Number of

family units

34

66 53 85

238

Class II

Simple

17.4%

33.6% 35.1%

55.7%

35.5%

Joint

82.6%

66.4%

64.9% 44.3%

64.5%

Number of

family units

69

116

134 140

459

Class III

Simple 50.0% 47.5%

55.4% 58.1%

52.8%

Joint

50.0% 52.5%

44.6% 41.9%

47.2%

Number of

family units 20

82 128

91

321

The three socioeconomic groups, which were identified jointly on

the basis of the husband’s occupation and educational status, were:

I. Higher professions and services: physicians, engineers, office

executives, wholesale businessmen.

II. Clerks, supervisors, retail traders.

III. Manual laborers, skilled and unskilled.

Composition of the family unit of each couple under study was

first carefully examined to place the unit under one of two broad

types: 1. simple (nuclear) type composed of only the parents and

their unmarried children, and 2. extended or joint (non-nuclear)

type consisting of simple families plus one or more consanguineous

relatives or other genealogically determinable relatives. To avoid a

detailed discussion of typological classification17 these two broad

types of family organization have been adhered to primarily in con

sideration of the current controversy over the question of joint (ex

tended) family’s relationship to higher fertility.

The couples belonging to each of the three socioeconomic groups

456

were further classified by duration of marriage, and the average

number of children ever-born per couple in each marriage duration

class was analyzed. Family affiliation of each couple was also noted.

The proportional concentrations of simple and joint families under

each marriage-duration class are shown in Table 2.

Regarding the nature of variation in fertility rates within the

three occupationally oriented social classes, it has already been

pointed out that “fertility rates of couples belonging to higher

professions, higher services, etc. (social class I) are lower than those

pertaining to the social classes II and III, particularly in the higher

marriage duration classes.” 18

Variations in the average number of children ever-born per couple

in the different social classes have been further examined on the

TABLE 3. AVERAGE NUM BER OF CHILDREN BORN PE R COUPLE BY

SOCIAL CLASS, D URATION OF MARRIAGE AND FAM ILY TYPE AMONG THE

POPULATION OF CALCUTTA, W EST BENGAL, 1956- 57.

Average Number of

Children Ever Born

Duration of Number of Couples in per Couple in

Social Marriage

Simple

Joint

Simple

Joint

Class (years)

Family Family

Family*

Family'-

Class I 0-4

10

24

0.9 0.6

5-9 29

37

2.1

2.1

10-14

25

28

3.4

2.6

154- 43

42

3.8

3.4

all 107 131

2.9

2.3

All-standardized rate 2.9

2.5

Class II 0-4

12

57

1.2

1.0

5-9 39 77

2.6 2.1

10-14

47 87

3.8

3.4

154-

78

62

4.9

4.6

all 176 283 3.8 2.8

All standardized rate

3.4

3.1

Class III 0-4

10

10 1.0 0.7

5-9 39 43 2.0 2.6

10-14

71 57 3.5

4.1

15+

53

38

5.3 5.1

all 173 148 3.5 3.7

All standardized rate

3.5 3.8

* Averages are based on the number of couples falling under each family type and each marriage

duration—class.

457

basis of the structural characteristics of the family in which the

couples were components. Table 3 shows that for social classes I

and II the average number of children ever-born per couple in

extended or joint families is definitely less than that in simple (non-

extended) families, when women of all marriage duration classes

are considered. This is also true for nearly all women of any mar

riage-duration class, except the initial one (0-4 years). Standardized

rates have been computed and the trend in classes I and II indicates

that this development cannot be explained simply by chance.

In class III, the average number of children ever-born per couple

is more in extended or joint families. Couples in this group differ

from the couples in classes I and II in having less of a children load

within simple (non-joint) family units. In this group, however, any

trend in the averages cannot be proved.

The couples in class I not only had the lowest fertility rate of the

three classes, but also maintained the same trend with respect to

their family orientation toward simple or joint family types. The

lowest standardized rate of fertility for couples belonging to simple

or joint families is obtained in the highest socioeconomic group. The

highest standardized rates, of course, are obtained from couples in

the lowest socioeconomic class, with the couples in class II scoring

between the two extremes.

Some interesting conclusions may be based upon these findings:

1. Joint (extended) families are not an essential prerequisite for

abundant reproduction.

2. Urban population closely resembled the rural population of West

Bengal in the fertility differentials between women of joint and sim

ple families. The urban, class I population averaged the fewest num

ber of children per mother, especially in joint families.

3. Irrespective of their location, whether urban or rural, the women

of West Bengal averaged a greater number of children in simple

families than in joint families. This trend is evident in Nag’s study14

and in the present one. Under the circumstances, can this trend be

explained by chance factors alone?

4 5 3

4. A possible relationship between family type and fertility appears

to be a pertinent issue that cannot be ruled out of current social-

demographic research. A greater number of field investigations cover

ing wider areas to include more Indian communities are needed to

accumulate empirical data. What has been attempted so far has only

served to highlight the problem. The underlying basis of the rela

tionship between family type and fertility has yet to be established.

To this end, it is hoped that the findings in this paper, together with

those of Nag and others, may be the base of future investigations.

REFERENCES

1 Final Population Totals, in C e n su s of I ndia (1961), Government of

India, pp. x-xi.

2 Das Gupta, Ajit, et al., Couple Fertility, National Sample Survey Report

no. 7, Ministry of Finance, Government of India; Rele, J. R., Fertility Differ

entials in India: Evidence from a Rural Background, Milbank Memorial Fund

Quarterly, 41, 183-199, April, 1963; Chandrasekaran, G. and George, M. V.,

Mechanism Underlying the Differences in Fertility Patterns of Bengalee

Women from Three Socio-Economic Groups, Milbank Memorial Fund Quar

terly, 40, 59-89, January, 1962; Jain, S. P., R elatio n sh ip Between Fertility

and Economic and Social Statu s in th e Pu n jab, Lahore, Punjab Board of

Economic Inquiry, 1939; Sovani, N. V. and Dandekar, Kumudini, Fertility

Survey of Na sik, K olaba and Satara (N or t h ) D istricts, Poona Gokhale

Institute of Politics and Economics, 1955; Sinha, J. N., Differential Fertility and

Family Limitation in an Urban Community of Uttar Pradesh, Population Stud

ies, 11, 157-169, November, 1957.

3 Chandrasekaran, C., Fertility Trends in India, Proceedings of the World

Population Conference, 1, 827, August—September, 1954; Jain, S. P., Indian

Fertility: Trends and Patterns, Proceedings of the World Population Conference,

1, 901, August-September, 1954; Rele, J. R., loc. cit.

4 Davis, Kingsley, Human Fertility in India, The American Journal of

Sociology, 52, 243-254, November, 1946.

5 Chandrasekhar, Sripathi, I ndians Population : Fact and Policy, New

York, The John Day Company, Inc., 1946.

6 Kiser, Clyde V. and Whelpton, P. K., Number of Children in Relation to

Fertility in Planning and Socio-Economic Status, Eugenical News, 34, 33-43,

1949.

7 The Family Planning Association of India, Report of the Proceedings of

the Third International Conference on Planned Parenthood, Bombay, 1952, pp.

14-25 and 68-79.

8Lorimer, F., C ultu re and H um an Fertility, Paris, UNESCO, 1954.

459

9 Davis, Kingsley, T he Population of I ndia and Pa k istan, Princeton,

New Jersey, Princeton University Press, 1951; Driver, Edwin D., Fertility Dif

ferentials Among Economic Strata in Central India, Eugenics Quarterly, 7,

77-85, 1960; T he M ysore Population Study, New York, The United Na

tions, 1961; Samuel, T. J., Culture and Human Fertility in India, Journal of

Family Welfare, 9, 48, June, 1963; Stycos, J. M., Problems of Fertility Control

in Underdeveloped Areas, in Mudd, S. (Editor), T he Population Crisis

and th e U se of W orld R esources, Bloomington, Indiana, Indiana Univer

sity Press, 1964, p. 95; Bebarta, Prafulla C., Family Structure and Fertility, in

Proceedings (A b s t r act s) of t h e I ndian Science Congress, Part 3, 1965,

p. 503, Pakrasi, Kanti, On Some Aspects of Fertility and Family in India, Indian

Journal of Social Work, 17, 153-162, July, 1966.

10 International Planned Parenthood Federation, Report of the Proceedings

of the Fifth International Conference on Planned Parenthood, London, 1955.

11 Chandrasekhar, Sripathi, Cultural Barriers to Family Planning in Under

developed Countries, Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on

Planned Parenthood, London, 1955, pp. 64-70.

12 Davis, Kingsley, Institutional Patterns Favoring High Fertility in Under

developed Areas, Eugenics Quarterly, 2, 33-39, March, 1955; and in Shanon,

L. W. (Editor), U nderdeveloped A reas, New York, Harper & Brothers, Pub

lishers, 1957.

13 Poti, Sankar J. and Dutta, Subodh, Pilot Study on Social Mobility and Its

Association with Fertility in West Bengal in 1956, Artha Vijnana, 2, 85-96,

June, 1960; Bebarta, Prafulla C., loc. cit., Mukherjee, Ramkrishna, T he Soci

ologist and Social C hanges in India T oday, New Delhi, Prentice-Hall of

India, Ltd., 1965, pp. 10-11; Mathen, K. K., Preliminary Lessons Learned from

the Rural Population Control Study of Singur,

in Kiser, Clyde V. (Editor),

R esearch in Fam ily Planning, Princeton, New Jersey, Princeton University

Press, 1962, pp. 33-50.

14 Nag, Moni, Family Type and Fertility, Paper submitted to the United

Nations World Population Conference, Belgrade, 1965.

15 Das Gupta, Ajit, et al., op. cit., pp. 7-8.

16 Poti, Sankar J., Malaker, Chittaranjan and Chakraborti, Bimal, An En

quiry into the Prevalence of Contraceptive Practices in Calcutta (1956-57), in

Studies in Fam ily Plannin g, Ministry of Health, Government of India, 1960,

pp. 63-89; Poti, Sankar J., Chakraborti, Bimal and Malaker, Chittaranjan,

Reliability of Data Relating to Contraceptive Practices, in Kiser, R esearch

in Fam ily Plannin g, op. cit., pp. 51-65.

17 Pakrasi, Kanti, A Study of Some Aspects of Household Types and Family

Organization in Rural Bengal, 1946—47, The Eastern Anthropologist, 15, 55—63,

September-December, 1962; and A Study of Some Aspects of Structural Varia

tions among Immigrants in Durgapur, West Bengal, Man In India, 42, 114-125,

April-June, 1962.

18 Poti, Malaker and Chakraborti, An Enquiry into the Prevalence of Con

traceptive Practices in Calcutta, op. cit., p. 3.

460

REVIEW ARTICLE

STUDIES IN EPIDEMIOLOGY

Selected Papers of Morris Greenberg, M.D.

FRED B. ROGERS, EDITOR

New York, G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1965. 418 + xxviii pp. $8.50

This book, a collection of more than a score of previously pub

lished papers and documents, was conceived and published by the

friends and colleagues of Morris Greenberg as a tribute to the

late Director of the Bureau of Preventable Diseases for the New

York City Department of Health, who was also the Adjunct Pro

fessor of Epidemiology at Columbia University. The affection and

esteem in which Greenberg was held is apparent in the tributes by

Leona Baumgartner, Harry Mustard and Gurney Clark, which

preface the book.

The general purpose of this collection, as stated by Gurney Clark,

is to add a new volume to the growing “bookshelf of collected public

health papers by leading modem American workers.” The editor,

Fred B. Rogers, comments that the papers “ illustrate technical

competence in gathering and evaluating data, arriving at conclu

sions, and finally taking action.” It is by editorial action that papers

on diverse subjects have been integrated, and it is therefore this

editorial contribution which must be examined to see if the man and

his mind emerge from behind the memorial facade. In short, does

editor Rogers do justice to his subject?

To begin with, Greenberg and his department have already been

introduced to a generation of medical students and public by the

461

Boswellian accounts of Berton Roueche, which cover the same time

period and many of the same epidemiological adventures as in the

Rogers collection. But Roueche is better able to communicate the

drama, triumphs and hardships of field epidemiology than the crisp,

terse case reports included in this book.

Greenberg himself defined epidemiology from the vantage point

of one accustomed to dealing with the community: “a science con

cerned with the relationships of disease in the aggregate—what has

been called ‘crowd diseases.’ ” Perhaps because he was a practicing

pediatrician during the early period of his professional life, the sub

ject matter of his papers tends to retain a clinical orientation and to

specialize in the area of maternal and child health. Statistical and

research sophistications appear in his publications, but are not em

phasized in this collection; the viewpoint is eminently practical and

even the most theoretical considerations are translated into public

health action. Two examples illustrate both his style and the concern

arising out of his investigations:

Blanket advocacy of therapeutic abortion in pregnant women

who develop rubella during the early months of pregnancy is

medically unjustified. Exposure of susceptible young girls to cases

of rubella is medically justified and is a sound public-health

procedure.

What difference does it make if you give the patient a shot of

penicillin? Well, it does make a difference! It is time to call a

halt to the march back to Lister’s era and to remember that

cleanliness is still nearest to Godliness.

It is, however, becoming the practice to define epidemiology as

that which epidemiologists do. Therefore, any collection of the

life’s work of a great epidemiologist could be a formative document

which helps to delineate the methods of epidemiological enquiry. If

this is the aim of this memorial, the editorial work is not always

successful. Rogers has organized the reports into five groups—scope,

content and method of epidemiology; studies in community and in

stitutional settings; bacterial and viral diseases; immunoprophylaxis

and therapy; and congenital anomalies and defects. Rogers precedes

each paper with an introduction intended to put Greenberg’s con

462

tribution into the global scope of medical progress. The introduc

tions, however, tend to focus upon the disease state in question,

rather than upon Greenberg’s contribution to the growing list of

epidemiological skills and practices.

Sometimes the reason for the selection of a specific paper is un

certain. In fact, the editor is not always kind to his author: he in

cludes three early reports on the clinical use of gamma globulin for

“historical record” but omits the historical first four reports of

Rickettsialpox, substituting a summary prepared for a textbook. A

lengthy series of clinical and pathological case reports of congenital

cardiac anomalies in infants is included, though their focus is not

epidemiological. Two papers originally published in Nursing World

display Greenberg’s skills in communication about such topics as

Salk vaccine and viral diseases, though these treat epidemiological

considerations too superficially. Another technical paper on po

liomyelitis prepared for Hospitals is more successful, only because

it includes matters of organization and mobilization of medical ser

vices which were based upon sound epidemiological principles. In

the case of poliomyelitis and the embryopathic effects of rubella in

pregnancy, however, the order of scientific reports and the editorial

comment blend and successfully communicate the steps of epi

demiological investigation; in the case of others, even when the

original research protocol is included, the brevity of details will make

them less suitable as models for teaching methods of enquiry.

The reader may also find a number of minor editorial decisions

troublesome: publication citations are not given immediately in as

sociation with each paper; individual articles are not listed in the

table of contents or on the page headings, so that one has difficulty

in finding a paper quickly; photographs included with several of

the papers are not of sufficient quality to warrant reproduction.

Whether Rogers’ collection and editorial comments do justice

to the mind of his subject can best be answered by Morris Green

berg’s friends. This reviewer cannot help but feel that the unique

contribution which Greenberg made to epidemiological progress has

not, however, been given sufficient prominence by the editorial work.

In his prefatory tribute Harry Mustard points out that Morris Green

463

berg, the epidemiologist, was a product of both his native ability

and New York City: “The city’s own vast and mixed population,

its packed millions, its steady flood of visitors, its incoming mari

time commerce .. . made inevitable the endemic existence of a wide

gamut of communicable diseases and the threat of epidemics a

continuing menace.” Greenberg rose to the challenge which this

megapolis afforded. The epidemiological method is usually con

fined to the study of diseases of relatively high prevalence. But in a

population base the size of New York City, it is possible to study, by

both prospective and retrospective means, diseases of low incidence

rate. Possible, yes— but only with a superb epidemiological intelli

gence system that permeates the entire health care system. This or

ganization Morris Greenberg had, and developed so that he could

conceive and perform research studies impossible elsewhere. New

York City gave scope for Greenberg’s scientific curiosity.

In some cases, his studies were conducted specifically because of

the existence of this reporting system, as, for example, an evaluation

of different methods of prophylaxis for ophthalmia neonatorum and

the study of congenital defects of children bom to mothers who had

rubella in their first trimester of pregnancy. In another situation, this

large population produced enough persons for anti-rabies treatment,

so that it was possible for Greenberg to compare duck embryo and

Semple vaccines. The massive vaccination programs during the

1947 epidemic of smallpox in New York City permitted him to

undertake a definitive analysis of the complications, and report

on the effects of vaccination during pregnancy. It required this large

population to produce 13 infants whose acute diarrhea was identified

as being caused by Salmonella montevideo in canned egg yolk

powder, and 194 cases of pica from which 28 cases of proven and

20 of probable lead poisoning were found. An outbreak of 84 cases

of trichinosis led Greenberg to make a comparison of the intradermal

and precipitin tests for this disease. The periodic epidemics of

poliomyelitis provided him with sufficient numbers of cases to com

plete a most thorough examination of the relationship between

tonsillectomy and poliomyelitis. Yet, this combination of natural

and planned experiments was always carefully handled, and Green

464

berg assiduously avoided generalizing beyond his data or drawing

false conclusions. The limitations of natural experiments were

clearly always before this investigator.

The real value of this book, then, lies in the fact that the ma

jority of its papers comprise the first collection in the growing prac

tice of mass epidemiology, or to coin a term, epimegademiology—

the study of disease distribution and determinants in massive popu

lation groups. That this work was done by a man who had significant

administrative responsibilities is a tribute not only to his scientific

curiosity, but also to his organizational expertise. If this is not wholly

apparent in this book, the fault must be regarded as an editorial one.

Rogers has focused upon disease; the book would have been a more

useful and a greater tribute to its subject had it focused on the

epidemiological intelligence service Greenberg used so effectively.

In one sense, the collection portrays Greenberg in the same sense

as the novelist Ian Fleming portrayed James Bond— in a series of

spectacular confrontations with the criminal world. What was

needed was the viewpoint of Bond’s superior, M, and a description

of how he selected priorities and used his agents effectively. That,

I think, was the way Morris Greenberg advanced the discipline of

epidemiology.

DONALD O. ANDERSON

465