OFFICE of the UNITED STATES TRADE REPRESENTATIVE

EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT

Section 301 Investigation

Report on the United Kingdom’s

Digital Services Tax

January 13, 2021

i

Contents

Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... iii

I. Background .............................................................................................................................. 1

A. Multilateral Negotiations and the United Kingdom’s Adoption of the Digital Services

Tax ....................................................................................................................................... 1

B. Background of the Investigation .......................................................................................... 3

1. Relevant Elements of Section 301 ...................................................................................... 3

2. Focus of the Investigation ................................................................................................... 4

3. Input from the Public .......................................................................................................... 4

II. The United Kingdom Digital Services Tax ............................................................................. 5

A. Features of the United Kingdom’s Digital Services Tax ..................................................... 5

B. Covered Companies ........................................................................................................... 11

III. USTR’s Findings Regarding the United Kingdom’s Digital Services Tax ....................... 13

A. The United Kingdom’s Digital Services Tax Discriminates Against U.S. Companies ..... 13

1. Statements by UK Officials Show that the Digital Services Tax Is Intended to

Unfairly Target U.S. Companies ...................................................................................... 13

2. The Selection of Covered Services Under the UK DST Discriminates Against

U.S. Companies ................................................................................................................ 15

3. The UK DST Revenue Thresholds Discriminate Against U.S. Companies ..................... 16

B. The United Kingdom’s Digital Service Tax Is Unreasonable Because It Is

Inconsistent with International Tax Principles .................................................................. 18

1. The DST’s Application to Revenue Rather than Income Is Inconsistent with

International Tax Principles .............................................................................................. 18

2. The UK DST Results in Double Taxation ........................................................................ 20

3. The UK DST’s Retroactivity Is Inconsistent with International Tax Principles ............. 22

4. The UK Digital Services Tax’s Extraterritoriality Is Inconsistent with International

Tax Principles ................................................................................................................... 23

C. The United Kingdom’s Digital Service Tax Burdens or Restricts U.S. Commerce .......... 26

1. DST Liability Is a Burden ................................................................................................. 26

2. The UK DST’s Results in a Burdensome Effective Tax Rate for Covered

U.S. Companies ................................................................................................................ 26

3. The UK DST Incurs High Compliance and Administrative Costs, Burdening

Leading U.S. Companies .................................................................................................. 27

ii

4. The UK DST’s Relationship to the UK Corporation Tax Burdens Covered

U.S. Companies ................................................................................................................ 31

5. The UK DST Burdens on Small- and Medium-Sized U.S. Companies ........................... 31

D. The United Kingdom’s Public Rationales for the Digital Services Tax Are

Unpersuasive ...................................................................................................................... 32

1. Covered Companies Do Not Have Lower Tax Rates than Non-Covered Companies ..... 32

2. UK Users Do Not Create Value for the Covered Companies in a Unique, Significant

Way ................................................................................................................................... 34

3. The UK DST Was Not Created as an “Interim Measure” or “Temporary Tax” and

Undermines Development of a Multilateral Approach ..................................................... 37

IV. Conclusions ........................................................................................................................ 39

iii

REPORT ON THE UNITED KINGDOM’S DIGITAL SERVICES TAX PREPARED IN THE

INVESTIGATION UNDER SECTION 301 OF THE TRADE ACT OF 1974

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and G20

countries began negotiations in 2013 to address tax matters related to the digitalization of the

economy as part of a broader review of international tax rules. Additional multilateral

negotiations in that area are ongoing at the OECD.

On July 22, 2020, despite ongoing negotiations at the OECD, the United Kingdom

adopted a Digital Services Tax (DST). The UK’s unilateral DST applies a two percent tax on the

revenues of certain search engines, social media platforms and online marketplaces. The UK

DST applies only to companies with “digital services revenues” exceeding £500 million and

“UK digital services revenues” exceeding £25 million. Companies became liable for the DST on

April 1, 2020.

On June 2, 2020, the U.S. Trade Representative initiated an investigation of the UK DST

under section 302(b)(1)(A) of the Trade Act of 1974, as amended (the Trade Act). Section 301

of the Trade Act sets out three types of acts, policies, or practices of a foreign country that are

actionable: (i) trade agreement violations; (ii) acts, policies or practices that are unjustifiable

(defined as those that are inconsistent with U.S. international legal rights) and burden or restrict

U.S. commerce; and (iii) acts, policies or practices that are unreasonable or discriminatory and

burden or restrict U.S. commerce. If the Trade Representative determines that an act, policy, or

practice of a foreign country falls within any of the categories of actionable conduct, the Trade

Representative must determine what action, if any, to take.

As discussed in this report, the investigation identified unreasonable, discriminatory, and

burdensome attributes of the UK DST.

The UK DST discriminates against U.S. companies. UK Chancellor of the Exchequer

Philip Hammond introduced the DST as “a narrowly-targeted tax” on revenues from “specific

digital platform business models” that would be “carefully designed to ensure it is established

tech giants – rather than our [UK] tech start-ups – that shoulder the burden of this new tax.”

1

Such references to “established tech giants” by the UK allude to successful U.S. companies and

indicate the intention to target U.S. companies while excluding similarly situated UK digital

service companies. The UK DST, as adopted, is structured to target leading U.S. companies.

Because the UK DST only pertains to three specific categories in which U.S. firms are

marketplace leaders—namely, certain search engines, social medial platforms and online

marketplaces—the UK DST unfairly targets U.S. companies. Additionally, companies which

meet the DST’s thresholds are expected to be exclusively, or predominately, U.S. companies.

The UK DST is unreasonable as it is inconsistent with prevailing principles of

international taxation. By applying to certain gross revenues instead of income, the UK DST is

inconsistent with prevailing principles of international corporate taxation. Application to certain

gross revenues also results in double taxation, which is inconsistent with the principle of

avoidance of double taxation. Because the UK DST incurs liability prior to its date of

1

Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond, Budget 2018: Philip Hammond’s speech (Oct. 29, 2018).

iv

enactment, even if for a period of months, the UK DST is inconsistent with the principle of

retroactivity. The UK DST is also structured to extend corporate taxation beyond the

international tax principle of a permanent establishment, making the DST unfairly

extraterritorial.

The UK DST is burdensome for affected U.S. companies. The DST is a burden on

covered U.S. companies. The UK DST also incurs administrative, compliance, and cost burdens.

Additionally, the UK DST adds to already high audit risk and uncertainty, which leads to

additional costs. Because the UK DST imposes burdens and costs on covered companies, the

UK DST burdens or restricts U.S. commerce.

Conclusions

As described in this report, the results of this investigation indicate that:

(1) The United Kingdom’s DST, by its structure and operation, discriminates against U.S. digital

companies, including due to the selection of covered services and the revenue thresholds.

(2) The United Kingdom’s DST is unreasonable because it is inconsistent with principles of

international taxation, including due to application to revenue rather than income,

extraterritoriality, and retroactivity.

(3) The United Kingdom’s DST burdens or restricts U.S. commerce.

1

I. BACKGROUND

A. MULTILATERAL NEGOTIATIONS AND THE UNITED KINGDOM’S ADOPTION OF THE

DIGITAL SERVICES TAX

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and G20

countries began negotiations in 2013 to address tax matters related to the digitalization of the

economy as part of a broader review of international tax rules.

2

Some outcomes were reached:

the OECD and G20 countries decided on actions countries should implement to improve the

operation of the international tax system.

3

Additional multilateral negotiations in that area are

ongoing at the OECD.

4

On October 29, 2018, while OECD negotiations continued, the UK Chancellor of the

Exchequer announced the creation of a new tax on digital services.

5

Public consultations within

the UK raised concerns regarding the proposed DST,

6

including that: “revenue-based taxes can

generate high effective rates of tax on profits, [and] risked being economically distortive[,]”

7

“the scope of the DST by reference to business activities was too complex or ambiguous, and

would make it difficult for businesses to know if they were in scope or not[,]”

8

and the “degree

to which this [the UK’s DST] would differ from DSTs being implemented in other countries,

which would increase administrative burdens and the risks of double taxation[.]”

9

Despite these concerns, the UK DST was introduced as part of the Finance Bill 2020.

10

Written evidence received during the bill’s consideration again reflected significant concerns,

including: “over some uncertainties in its application, but mostly that it risks contributing to a

tide of unilateral measures, which bring compliance cost, complexity and double taxation, and

ultimately also a less effective basis for combatting avoidance than full multinational

2

See OECD, Action Plan on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting, July 19, 2013.

3

See OECD, OECD presents outputs of OECD/G20 BEPS Project for discussion at G20 Finance Ministers’

meeting, Oct. 5, 2015; OECD, BEPS 2015 Final Reports, Oct. 5, 2015, https://www.oecd.org/ctp/beps-2015-final-

reports htm.

4

See, e.g., OECD, Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Report on Pillar One Blueprint: Inclusive

Framework on BEPS, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, 9, OECD P

UBLISHING (Oct. 14, 2020).

5

Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond, Budget 2018: Philip Hammond’s speech (Oct. 29, 2018),

(transcript available at https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/budget-2018-philip-hammonds-speech).

6

HM Treasury, HM Revenue & Customs, Digital Service Tax: Consultation, Gov.UK (Nov. 2018),

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/754975/Digital_S

ervices_Tax_-_Consultation_Document_FINAL_PDF.pdf.

7

HM Treasury, Digital Services Tax: response to the consultation, ¶ 2.6, Gov.UK (Jul. 2019),

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/816389/DST_resp

onse_document_web.pdf (hereinafter “Digital Services Tax: Response to the Consultations”).

8

Digital Services Tax: Response to the Consultations, ¶ 3.3.

9

Id at ¶ 3.3.

10

Finance (Digital Services Tax) Bill 2020, HC Bill [114], https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/bills/cbill/58-

01/0114/20114.pdf (UK).

2

agreement.”

11

The bill received Royal Assent and was adopted as the Finance Act 2020 on

July 22, 2020.

12

In 2018, an OECD report stated that “[t]here is no consensus on either the merit or need

for interim measures[.]”

13

In 2020, an OECD report noted that “it is expected that any

consensus-based agreement must include a commitment by members . . . to withdraw relevant

unilateral actions, and not adopt such unilateral actions in the future.”

14

Despite the United

Kingdom’s approval of this OECD report,

15

the UK adopted a DST without a sunset clause.

16

The UK government asserts that “[t]he DST is intended to be an interim measure, pending a

long-term global solution to the tax challenges arising from digitalization” and that it “believes

this [review clause] achieves the same objectives as a sunset clause.”

17

However, the UK’s own

policy papers admit that in order to repeal the DST “Parliament would then need to take separate

action, through a Finance Bill, to give effect to any decisions on the DST arising from the

review[.]”

18

Unilateral laws, like the United Kingdom’s DST, undermine progress in the OECD by

making an agreement on a multilateral approach to digital taxation less likely.

19

If unilateral

measures proliferate while negotiations are ongoing, countries lose the incentive to engage

seriously in the negotiations.

20

For this reason, among others, the United States has discouraged

governments from adopting country-specific DSTs. Nonetheless, the United Kingdom has

chosen to create and implement its own unilateral tax on digital services.

11

Written evidence submitted by the Chartered Institute of Taxation (FB12), PARLIAMENT.UK (Jun. 15, 2020),

https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5801/cmpublic/Finance/memo/FB12.pdf (hereinafter “Chartered Institute of

Taxation DST Written Evidence”).

12

HL (22 Jul. 2020) (804), https://hansard.parliament.uk/lords/2020-07-22/debates/4819BE33-24A9-48F8-BE5A-

BB0FA4D69EB5/RoyalAssent.

13

Org. for Economic Co-operation and Development, Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Interim Report

2018: Inclusive Framework on BEPS, at 178 (OECD Publishing 2018), https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/taxation/tax-

challenges-arising-from-digitalisation-interim-report_9789264293083-en#page180.

14

Org. for Economic Co-operation and Development, Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Report on Pillar

One Blueprint, at 211 (OECD Publishing 2018), https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/taxation/tax-challenges-arising-from-

digitalisation-report-on-pillar-one-blueprint_beba0634-en#page213.

15

Id at 4.

16

See Finance Act (2020) § 71, c. 14 (Eng.), https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2020/14/part/2/enacted.

17

HM Treasury, Digital Service Tax: response to the consultation, § 7.7-7.8, Gov.UK (Jul. 2019),

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/816389/

DST_response_document_web.pdf.

18

HM Treasury, HM Revenue & Customs, Digital Service Tax: Consultation, § 9.9, Gov.UK (Nov. 2018).

19

See, e.g., Chartered Institute of Taxation DST Written Evidence at 1.

20

See, e.g., Silicon Valley Tax Directors Group, Comment Letter Re: Written Submission in Response to Initiation

of Section 301 Investigations of Digital Services Taxes (USTR-2020-0022), 75 (Jul. 15, 2020) (“In recent

Parliamentary debates, the [UK] Government was challenged to include a review of the UK DST in 12 months from

its effective date, but it declined to do so. In light of this, we are not confident the UK would withdraw its DST if a

global consensus is reached.”).

3

B. BACKGROUND OF THE INVESTIGATION

On June 2, 2020, the U.S. Trade Representative initiated an investigation of the UK DST

under section 302(b)(1)(A) of the Trade Act.

21

On the same date, the Trade Representative

requested consultations with the government of the United Kingdom.

22

The United Kingdom’s

Chancellor of the Exchequer accepted the request for consultations in a letter dated August 18,

2020.

23

Consultations were held on December 4, 2020.

As set out in the Notice of Initiation, the investigation involves determinations of whether

the act, policy, or practice at issue—i.e., the UK’s DST—is actionable under section 301 of the

Trade Act, and if so, what action, if any, to take under Section 301. This report provides analysis

relevant to a determination of actionability under Section 301.

1. Relevant Elements of Section 301

Section 301 sets out three types of acts, policies, or practices of a foreign country that are

actionable: (i) trade agreement violations; (ii) acts, policies or practices that are unjustifiable

(defined as those that are inconsistent with U.S. international legal rights) and burden or restrict

U.S. commerce; and (iii) acts, policies or practices that are unreasonable or discriminatory and

burden or restrict U.S. commerce.

24

Section 301 defines “discriminatory” to “include . . . any

act, policy, and practice which denies national or most-favored nation treatment to United States

goods, service, or investment.”

25

“[U]nreasonable” refers to an act, policy, or practice that

“while not necessarily in violation of, or inconsistent with, the international legal rights of the

United States is otherwise unfair and inequitable.”

26

The statute further provides that, in

determining if a foreign country’s practices are unreasonable, reciprocal opportunities to those

denied U.S. firms “shall be taken into account, to the extent appropriate.”

27

If the Trade Representative determines that the Section 301 investigation “involves a

trade agreement,” and if that trade agreement includes formal dispute settlement procedures,

USTR may pursue the investigation through consultations and dispute settlement under the trade

agreement.

28

Otherwise, USTR will conduct the investigation without recourse to formal dispute

settlement.

If the Trade Representative determines that the act, policy, or practice falls within any of

the three categories of actionable conduct under Section 301, the USTR must also determine

21

Initiation of Section 301 Investigations of Digital Services Taxes, 85 Fed. Reg. 34,709, 34,710 (Jun. 5, 2020).

22

See Letter from Ambassador Robert Lighthizer to Rt Hon Elizabeth Truss MP, June 2, 2020 (Annex 1).

23

See Letter from Sec’y of State for Int’l Trade Rt Hon Elizabeth Truss MP & Chancellor of the Exchequer Rt Hon

Rishi Sunak MP to Ambassador Robert Lighthizer, Aug. 18, 2020 (on file with USTR).

24

19 U.S.C. § 2411(a)-(b).

25

19 U.S.C. § 2411(d)(5).

26

19 U.S.C. § 2411(d)(3)(A).

27

19 U.S.C. § 2411(d)(3)(D).

28

19 U.S.C. § 2413(a).

4

what action, if any, to take. If the Trade Representative determines that an act, policy or practice

is unreasonable or discriminatory and that it burdens or restricts U.S. commerce:

The Trade Representative shall take all appropriate and feasible action authorized

under [section 301(c)], subject to the specific direction, if any, of the President

regarding any such action, and all other appropriate and feasible action within the

power of the President that the President may direct the Trade Representative to

take under this subsection, to obtain the elimination of that act, policy, or

practice.

29

Actions authorized under Section 301(c) include: (i) suspending, withdrawing, or preventing the

application of benefits of trade agreement concessions; (ii) imposing duties, fees, or other import

restrictions on the goods or services of the foreign country; (iii) entering into binding agreements

that commit the foreign country to eliminate or phase out the offending conduct or to provide

compensatory trade benefits; or (iv) restricting or denying the issuance of service sector

authorizations, which are federal permits or other authorizations needed to supply services in

some sectors in the United States.

30

2. Focus of the Investigation

The initial focus of the investigation was: “[d]iscrimination against U.S. companies;

retroactivity; and possibly unreasonable tax policy. With respect to tax policy, the DSTs may

diverge from norms reflected in the U.S. tax system and the international tax system in several

respects. These departures may include: [e]xtraterritoriality; taxing revenue not income; and a

purpose of penalizing particular technology companies for their commercial success.”

31

Additionally, USTR invited comments as to the extent to which the DST burdens or

restricts U.S. commerce as well as other aspects that may warrant a finding that the UK DST is

actionable under Section 301.

32

3. Input from the Public

USTR provided the public and other interested persons with opportunities to present their

views and perspectives on the United Kingdom’s DST. The Initiation Notice invited written

comments by July 15, 2020.

33

More than 380 public comments were filed in response to the

Initiation Notice.

34

USTR received comments from businesses, industry associations, and other

groups that supported the section 301 investigation and provided information and arguments in

support of the bases identified in the Initiation Notice.

35

29

19 U.S.C. § 2411(b).

30

In cases in which USTR determines that import restrictions are the appropriate action, preference must be given to

the imposition of duties over other forms of action. 19 U.S.C. § 2411(c).

31

Initiation of Section 301 Investigations of Digital Services Taxes, 85 Fed. Reg. 34,709, 34,710 (June 5, 2020).

32

Id.

33

Id. at 34,709.

34

See Initiation of Section 301 Investigations of Digital Services Taxes, Docket USTR-2020-0022,

R

EGULATIONS.GOV.

35

See, e.g., Silicon Valley Tax Directors Group, Comment Letter Re: Written Submission in Response to Initiation

of Section 301 Investigations of Digital Services Taxes (USTR-2020-0022), 14-25 (Jul. 15, 2020).

5

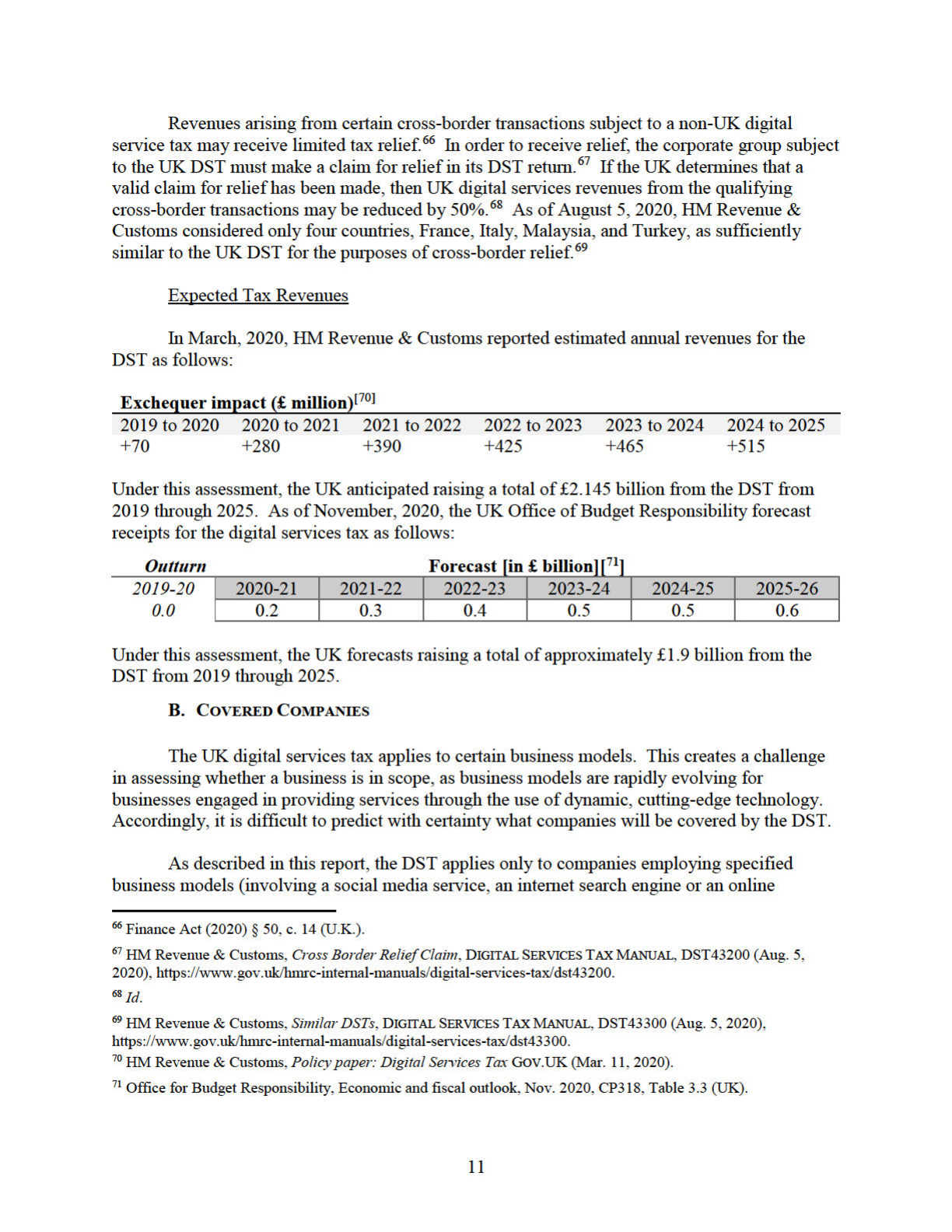

II. THE UNITED KINGDOM DIGITAL SERVICES TAX

This section describes the structure and expected operation of the United Kingdom’s

DST. Subsection A describes the content of the United Kingdom’s digital services tax, focusing

on several major elements: the definition of taxable services, the revenue thresholds for covered

companies, the scope of revenues covered, how the tax is paid, and its relationship to other taxes.

Subsection B discusses the companies that United Kingdom politicians and independent

commentators have suggested will be covered by the DST.

A. FEATURES OF THE UNITED KINGDOM’S DIGITAL SERVICES TAX

Taxable Services

The UK describes its DST as “a tax on the gross revenues that a group receives from

providing a digital services activity to UK users.”

36

The UK digital services tax applies to

certain business models. Specifically, the UK digital services tax applies to businesses that

provide a social media service, an internet search engine or an online marketplace.

37

The UK

law defines a “[s]ocial media service” as:

an online service that meets the following conditions—

(a) the main purpose, or one of the main purposes, of the service is to promote

interaction between users (including interaction between users and user-generated

content), and

(b) making content generated by users available to other users is a significant

feature of the service.[

38

]

Under the DST’s enacting law, an internet search engine “does not include a facility on a website

that merely enables a person to search—the material on that website, or the material on that

website and on closely related websites.”

39

The UK law defines an “[o]nline marketplace” as:

an online service that meets the following conditions—

(a) the main purpose, or one of the main purposes, of the service is to facilitate the

sale by users of particular things, and

36

HM Revenue & Customs, Overview of Revenues, DIGITAL SERVICES TAX MANUAL, DST21000 (Aug. 5, 2020),

https://www.gov.uk/hmrc-internal-manuals/digital-services-tax/dst21000.

37

Finance Act (2020) § 43(2), c. 14 (U.K.), https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2020/14/part/2/enacted.

38

Id. at § 43(3).

39

Id. at § 43(4).

6

(b)the service enables users to sell particular things to other users, or to advertise

or otherwise offer particular things for sale to other users.

40

Certain services, such as financial services, are excluded from the DST.

41

However,

HM Revenue & Customs guidance indicates that “[i]t is possible some non-financial

marketplaces may receive some revenues from financial or payment services. As these

marketplaces will not qualify for the exemption, these revenues will remain taxable where they

arise in connection with the marketplace.”

42

Revenue Thresholds

Under the UK law, companies are liable for the DST when the total amount of a business

group’s worldwide “digital services revenues” exceeds £500 million, and the total amount of

“UK digital services revenues” arising in that period to members of the group exceeds £25

million.

43

The UK “DST operates by reference to accounting periods[.]”

44

HM Revenue &

Customs guidance notes that “[t]he DST rules restrict the maximum length of the DST

accounting period to 12 months.”

45

Scope of Revenues

The first revenue threshold pertains to “digital services revenues.” These revenues are

defined as “the total amount of revenues arising to members of the group in that period in

connection with any digital services activity of any member of the group.”

46

As described by

HM Revenue & Customs:

40

Id. at § 43(5). HM Revenue & Customs guidance provides the following description:

There are two parts to the online marketplace definition which must both be satisfied for an online

service to fall in scope:

• the service enables users to sell particular things to other users, or to advertise or otherwise

offer to other users particular things for sale, and

• the main purpose, or one of the main purposes, of the service is to facilitate the sale by users

of particular things.

The first condition is a factual test which considers whether the features of the online service

enable third party users to sell things to other users. The second then considers whether the

facilitation of such transactions is a main purpose of the service.

HM Revenue & Customs, Online Marketplace - Overview, DIGITAL SERVICES TAX MANUAL, DST18100 (Aug. 5,

2020), https://www.gov.uk/hmrc-internal-manuals/digital-services-tax/dst18100.

41

Finance Act (2020) § 45, c. 14 (U.K.).

42

HM Revenue & Customs, Financial Services, DIGITAL SERVICES TAX MANUAL, DST18700 (Aug. 5, 2020),

https://www.gov.uk/hmrc-internal-manuals/digital-services-tax/dst18700.

43

Finance Act (2020) § 46, c. 14 (U.K.); HM Revenue & Customs, Policy paper – Digital Services Tax (March 11,

2020), https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/introduction-of-the-digital-services-tax/digital-services-tax.

44

HM Revenue & Customs, DST Accounting Periods, DIGITAL SERVICES TAX MANUAL, DST42000 (Aug. 5, 2020),

https://www.gov.uk/hmrc-internal-manuals/digital-services-tax/dst42000.

45

Id.

46

Finance Act (2020) § 40, c. 14 (U.K.).

7

This is a very broad concept. There only has to be a connection or link between

the revenues received and the underlying activity for the revenues to be included.

It does not matter how the group generates these revenues or how they are

described. This means revenues from ancillary activities to the DST activity will

be included as Digital Services revenues. . . . The breadth of this definition means

that revenues may arise in connection with both a digital service activity and

another online service. In these circumstances, the revenues should be attributed

to the digital services activity on a just and reasonable basis.

47

The second revenue threshold pertains to “UK digital services revenues.” UK digital

services revenues are defined as “so much of its digital services revenues for that period as are

attributable to UK users.”

48

The Finance Act outlines five circumstances in which revenues are

considered to be attributable to UK users:

Case 1 is where—

(a) the revenues are online marketplace revenues,

(b) they arise in connection with a marketplace transaction, and

(c) a UK user is a party to the transaction.

Case 2 is where—

(a) the revenues are online marketplace revenues, and

(b) they arise in connection with particular accommodation or land in the United

Kingdom (see section 42).

Case 3 is where—

(a) the revenues are online marketplace revenues,

(b) they arise in connection with online advertising for particular services, goods

or other property, and

(c) the advertising is paid for by a UK user.

Case 4 is where—

(a) the revenues are online advertising revenues,

(b) they are not within any of Cases 1 to 3, and

(c) the advertising is viewed or otherwise consumed by UK users.

Case 5 is where—

(a) the revenues are not within any of Cases 1 to 4, and

(b) they arise in connection with UK users.

49

Alternatively stated, HM Revenue and Customs guidance identifies that:

Social media services will often receive revenues from:

47

HM Revenue & Customs, Digital Services Revenues, DIGITAL SERVICES TAX MANUAL, DST23000 (Aug. 5,

2020), https://www.gov.uk/hmrc-internal-manuals/digital-services-tax/dst23000.

48

Finance Act (2020) § 41, c. 14 (U.K.).

49

Finance Act (2020) § 41, c. 14 (U.K.).

8

• displaying advertising to users of the service

• subscription or other access fees from users of the service

• charging users to access specific content on the platform

• other direct fees from users of the service

• sale or licencing of user data . . . .

Internet search engines will typically receive revenues from:

• Search advertising on the group’s search engine results

• Search advertising shown by the search engine on third-party websites

• Other search advertising revenues

• sale/licencing of user data . . . . [and]

Online marketplaces will often receive revenues from:

• Commission fees received for facilitating transactions between users

• Delivery fees

• Fees to access or otherwise buy and sell products, services or other property

on the platform

• Fees from advertising products to users of the marketplace, either by

preferential search listings or display advertising

• General advertising on the marketplace

• Subscription fees to access marketplace services[.]

50

However, the law exempts certain online marketplace revenues from the scope of UK digital

services revenues when “they arise in connection with particular accommodation or land outside

the United Kingdom . . . and . . . the only UK user who is a party to the transaction is a provider

or seller of the thing to which the transaction relates;” or “they arise in connection with particular

accommodation or land outside the United Kingdom[.]”

51

Rate

The UK digital service tax applies a 2% tax on covered revenues when a business group’s

revenues exceed the DST thresholds.

52

The UK DST provides for an allowance of £25 million,

which means that companies will not be charged for the first £25 million of covered revenues.

53

50

HM Revenue & Customs, Common Sources of Revenue from Digital Services Activities, DIGITAL SERVICES TAX

MANUAL, DST24000 (Aug. 5, 2020), https://www.gov.uk/hmrc-internal-manuals/digital-services-tax/dst24000.

51

Finance Act (2020) § 41 c. 14 (U.K.) (emphasis added).

52

See, e.g., HM Revenue & Customs, Policy Paper: Introduction of the new Digital Services Tax, , GOV.UK (Jul. 11,

2019), https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/introduction-of-the-new-digital-services-tax/introduction-of-

the-new-digital-services-tax; Digital Technology: Taxation, PQ61662, UK PARLIAMENT (June 24, 2020)

https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-questions/detail/2020-09-29/96879.

53

Finance Act (2020) § 46, 47, c. 14 (U.K.); see also HM Revenue & Customs, Policy paper: Digital Services Tax,

G

OV.UK (Mar. 11, 2020), https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/introduction-of-the-digital-services-

tax/digital-services-tax.

9

The UK also provides for an alternative basis of charge for its DST.

54

A company may

voluntarily elect to calculate its DST liability under this method.

55

Pursuant to HM Revenue &

Customs guidance, a separate election may apply to each category of digital services activities,

i.e., one for social media services, another for internet search engines and a third for its online

marketplaces.

56

This alternative calculation method involves seven steps:

Steps 1 & 2

The first step is therefore to divide the group’s total UK digital services revenues

between each category of digital services activity.

Step 3

The next step involves apportioning the £25m annual allowance between the

group’s categories of digital services activities. The apportionment is done by

multiplying the £25m allowance by the ratio of each category’s UK digital

services revenues over the group’s total UK digital services revenues.

Step 4

Step 4 involves calculating the operating margin of each category of revenues the

group has made an election to calculate its liability under the alternative charge.

This step does not need to be followed for any other category.

The operating margin is calculated by deducting any relevant operating expenses

(E) from the UK digital services revenues of that category (R). The result is then

divided by the UK digital services revenues of the category (R).

The margin will be nil if E exceeds R.

Step 5

The total liability of the group for the specified category of revenues (‘taxable

amount’) is calculated as 0.8 x the operating margin x the net revenues.

The operating margin is the margin found in Step 4.

The net revenues are found by deducting the category’s share of the allowance

(Step 3) from the UK digital services revenue of that category.

For any category of revenues that is not being calculated under the alternative

charge calculation, the taxable amount is 2% of the net revenues.

Step 6

The taxable amounts are then added together to come to the ‘group amount’ (i.e.

the total DST liability of the members of the group).

54

Finance Act (2020) § 48, c. 14 (U.K.).

55

HM Revenue & Customs, Alternative Charge Election, DIGITAL SERVICES TAX MANUAL, DST43400 (Aug. 5,

2020), https://www.gov.uk/hmrc-internal-manuals/digital-services-tax/dst43400.

56

HM Revenue & Customs, Alternative Charge Calculation, DIGITAL SERVICES TAX MANUAL, DST43410 (Aug. 5,

2020), https://www.gov.uk/hmrc-internal-manuals/digital-services-tax/dst43410.

10

Step 7

The relevant person’s liability to digital services tax in respect of the accounting

period is the appropriate proportion of the group amount. There is further

guidance on this in DST44000.

57

The UK notes that such an “election is only of benefit in cases where there is a very low

operating margin on the digital services activity.”

58

Retroactive Liability & Payment of DST

The United Kingdom adopted the DST on July 22, 2020.

59

However, DST tax liability

obligates as of April 1, 2020.

60

Payment for the UK DST is due on the day following the end of

nine months from the end of the accounting period.

61

The first accounting period begins on

April 1, 2020 and ends on March 31, 2021, subject to certain conditions.

62

Relationship to Other Taxes

In a policy document, HM Revenue & Customs identified that “[t]he DST will be

deductible as a normal business expense but not creditable against UK Corporation Tax”.

63

HM Revenue & Customs guidance following the DST’s adoption confirmed that “[t]here are no

specific rules determining the deductibility or otherwise of DST against any other tax liability.

For UK Corporation Tax the normal rules concerning whether expenditure is an allowable

deduction should be considered in respect of each DST liability.”

64

One comment noted that per

HM Revenue & Customs guidance, “the DST will be deductible against UK Corporation Tax

under existing principles, but it will not be creditable.”

65

This suggests that the UK DST is an

additive tax.

57

Id.

58

HM Revenue & Customs, Alternative Charge Election, DIGITAL SERVICES TAX MANUAL, DST43400 (Aug. 5,

2020), https://www.gov.uk/hmrc-internal-manuals/digital-services-tax/dst43400.

59

Royal Assent, House of Lords Hansard v. 804 (Jul. 22, 2020), https://hansard.parliament.uk/lords/2020-07-

22/debates/4819BE33-24A9-48F8-BE5A-BB0FA4D69EB5/RoyalAssent.

60

Finance Act (2020) § 61 c. 14 (U.K.); HM Revenue & Customs, Policy paper – Digital Services Tax (March 11,

2020) (“The Digital Services Tax will apply to revenue earned from 1 April 2020.”).

61

Finance Act (2020) § 51, c. 14 (U.K.).

62

Id. at § 61.

63

HM Treasury, Digital Service Tax: response to the consultation, Intended approach, Gov.UK (Jul. 2019),

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/816389/

DST_response_document_web.pdf.

64

HM Revenue & Customs, UK CT Deductibility of DST, DIGITAL SERVICES TAX MANUAL, DST47100 (Aug. 5,

2020), https://www.gov.uk/hmrc-internal-manuals/digital-services-tax/dst47100.

65

Silicon Valley Tax Directors Group, Comment Letter Re: Written Submission in Response to Initiation of Section

301 Investigations of Digital Services Taxes (USTR-2020-0022), 75 (Jul. 15, 2020).

12

marketplace) with, during the previous accounting period (of up to 12 months), digital services

revenues exceeding £500 million and UK digital services revenues exceeding £25 million.

72

Revenue thresholds are determined at the company group level.

73

Previously, companies have

not been required to publish (or even to collect) data on whether they meet these revenue

thresholds.

74

United Kingdom policy papers identify that the UK DST will be borne by “a small

number of large multinational groups.”

75

In a 2018 review of the DST, the UK Office for

Budget Responsibility reported that “[i]n total around 30 groups were identified[.]”

76

Those

groups were “identified using the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development World

Investment Report and the commercial ORBIS database.”

77

While that UK report did not identify which companies were among the 30 company

groups that may be subject to the DST, the report concluded that “[m]ost of the forecast revenue

is expected to come from a handful of large businesses. This mostly relates to advertising

revenue and the commissions charged by online marketplaces.”

78

The UK report’s conclusion is consistent with the few companies identified in this

investigation to have publicly addressed how they will handle the UK DST, which is an indicator

that those companies may incur UK DST liability. Notably, all of these companies were

U.S. companies. These include:

• Amazon, a U.S.-headquartered company, addressed how it would handle the UK DST

charge;

79

72

HM Revenue & Customs, DST Thresholds, Rates and Allowances, DIGITAL SERVICES TAX MANUAL, DST41000

(Aug. 5, 2020), https://www.gov.uk/hmrc-internal-manuals/digital-services-tax/dst41000.

73

Id.; Finance Act (2020) § 57, c. 14 (U.K.); HM Revenue & Customs, Definition of a Group for DST, DIGITAL

SERVICES TAX MANUAL, DST12600 (Aug. 5, 2020), https://www.gov.uk/hmrc-internal-manuals/digital-services-

tax/dst12600.

74

Finance Act (2020) § 54, c. 14 (U.K.) (addressing the “[d]uty to notify HMRC when threshold conditions are

met”).

75

HM Revenue & Customs, Policy paper – Digital Services Tax (March 11, 2020); HM Revenue & Customs,

Policy paper - Introduction of the new Digital Services Tax, Gov.UK (July 11, 2019),

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/introduction-of-the-new-digital-services-tax/introduction-of-the-new-

digital-services-tax.

76

Office for Budget Responsibility, Economic and fiscal outlook, 2018, Cm 9713, A.9-14 (UK).

77

Id.

78

Id.

79

Upcoming fee changes in the UK following introduction of Digital Services Tax, AMAZON SERVICES (Aug 4.

2020), https://sellercentral-europe.amazon.com/forums/t/upcoming-fee-changes-in-the-uk-following-introduction-

of-digital-services-tax/322163.

13

• Apple, a U.S.-headquartered company, addressed how it would handle the UK DST

charge;

80

• eBay, a U.S.-headquartered company, reported that “eBay is one of the marketplaces

which will have to pay the new tax[;]”

81

• Facebook, a U.S.-headquartered company, addressed how it would handle the UK

DST charge;

82

and,

• Google, a U.S.-headquartered company, addressed how it would handle the UK DST

charge.

83

Media reports corroborate the assessment that digital services companies impacted by the UK

DST are mainly U.S. companies.

84

III. USTR’S FINDINGS REGARDING THE UNITED KINGDOM’S DIGITAL SERVICES TAX

A. THE UNITED KINGDOM’S DIGITAL SERVICES TAX DISCRIMINATES AGAINST

U.S. COMPANIES

Analysis of “large multinational groups” subject to the UK DST identifies mainly

U.S. companies, indicating that the UK DST discriminates against and unfairly targets

U.S. companies.

1. Statements by UK Officials Show that the Digital Services Tax Is

Intended to Unfairly Target U.S. Companies

UK officials, including the UK Prime Minister, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and

members of Parliament have indicated that the DST is targeted towards U.S. companies. These

UK officials, who proposed and enacted the UK DST, have indicated the intention to target

80

Upcoming tax and price changes for apps and in-app purchases, DEVELOPER.APPLE.COM (Sept. 1, 2020),

https://developer.apple.com/news/?id=oyy56t2r.

81

UK News Team, Protecting your business from Digital Services Tax costs, COMMUNITY.EBAY.CO.UK (Oct. 8,

2020, 2:52 pm), https://community.ebay.co.uk/t5/Announcements/Protecting-your-business-from-Digital-Services-

Tax-costs/ba-p/6701162.

82

Facebook Won’t Hit UK Advertisers With Digital Tax Costs, LAW360 (Sept. 4, 2020, 4:09pm),

https://www.law360.com/articles/1307667/facebook-won-t-hit-uk-advertisers-with-digital-tax-costs.

83

See Alex Barker, Google to pass cost of digital services taxes on to advertisers, FIN. TIMES (Sept. 1, 2020),

https://www.ft.com/content/fda648aa-bb52-4ab2-aa18-46b5023cb893.

84

See, e.g., Alexander J. Martin, UK announces 2% digital services tax on Facebook, Google and Amazon, SKY

NEWS (Mar. 11, 2020), https://news.sky.com/story/uk-announces-2-digital-services-tax-on-facebook-google-and-

amazon-11955381 (“The department explained the tax was likely to affect ‘large multi-national enterprises with

revenue derived from the provision of a social media service, a search engine or an online marketplace to UK users’.

Key among these will be Facebook, Google and Amazon.”); Hadas Gold, U.S Tech companies will be hit with new

UK tax in just three weeks, CNN BUSINESS (Mar. 11, 2020), https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/11/tech/uk-digital-tech-

tax/index.html (“The measure is designed to ensure that large tech companies — many of them American — pay

more tax. . . .”).

14

U.S. companies by reference to “established tech giants[.]” This, and similar phrases, allude to

successful U.S. companies, which are frequently identified in conjunction with these statements

of intention. For example:

• On November 14, 2019, John McDonnell, a UK Member of Parliament, tweeted that

“[w]e will pay for this through . . . a new tax on multinationals – so the tech giants like

Facebook and Google will pay a bit more. . . .”

85

• On December 3, 2019, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson said that “[o]n the digital

services tax, I do think we need to look at the operation of the big digital companies and

the huge revenues they have in this country and the amount of tax that they pay. . . . We

need to sort that out. They need to make a fairer contribution.”

86

• On February 3, 2020, Margaret Hodge, a UK Member of Parliament, wrote that: “[l]ast

year we learnt once again how Google, Facebook, and Amazon all made billions of

pounds in the UK but only paid corporate tax bills worth tens of millions of pounds. This

is a fraction of what they should be paying! These US companies . . . are not paying their

fair share back.”

87

• On November 16, 2019, Jeremy Corbyn, a UK Member of Parliament and then-Leader of

the Labour Party, tweeted that “[w]hen companies like Google paid just £28 million in

tax - despite making £1.6 billion in UK sales - that suggests they can afford to contribute

a bit more.”

88

These statements address how much U.S. companies pay in taxes to the UK but do not address

whether similarly situated UK digital services companies should pay a greater share of taxes.

Such statements strongly point to an intention to target U.S. companies with special, unfavorable

tax treatment.

89

85

John McDonnell (@johnmcdonnellMP), TWITTER (Nov. 14, 2019, 5:12 PM), https://twitter.com/

johnmcdonnellMP/status/1195102227620384769 (emphasis added).

86

Johnson backs tech tax despite Trump’s threats, BBC (Dec. 4, 2019), https://www.bbc.com/news/business-

50656106.

87

Margaret Hodge, MP, Netflix must pay its fair share of tax, Politicshome.com (Feb. 3, 2020),

https://www.politicshome.com/thehouse/article/netflix-must-pay-its-fair-share-of-tax (emphasis added).

88

Jeremy Corbyn (@jeremycorbyn), TWITTER (Nov. 16, 2019, 8:19 AM), https://twitter.com/jeremycorbyn/

status/1195692857400725504 (emphasis added).

89

See also Information Technology Industry Council, Comment Letter on Docket No. USTR-2020-0022: Initiation

of Section 301 Investigations of Digital Services Taxes, 10-12 (July 15, 2020), https://beta regulations.gov/

comment/USTR-2020-0022-0345.

15

2. The Selection of Covered Services Under the UK DST Discriminates

Against U.S. Companies

In 2018, the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond introduced the Digital

Service Tax by announcing that:

This will be a narrowly-targeted tax on the UK-generated revenues of specific

digital platform business models.

It will be carefully designed to ensure it is established tech giants – rather than

our tech start-ups - that shoulder the burden of this new tax.

90

Carefully designed is an apt description—the UK DST targets three categories of services where

U.S. companies are market leaders: internet search engines, social media services and online

marketplaces. It appears unlikely that the DST will cover certain digital services where similar

UK or European firms are successful.

91

Internet Search Engines

Two analyses of the UK DST conclude that the only two search engines likely to qualify

for the UK DST are Google and Microsoft’s Bing.

92

The market share held by U.S. companies

corroborates such a conclusion. According to one data analytics firm, four U.S. companies:

Google, Bing, Yahoo!, and DuckDuckGo, account for over 99% of the search engine market.

93

Thus, inclusion of internet search engines as one of the three covered digital services provides

support for the conclusion that the UK DST is narrowly defined so as to unfairly target

U.S. companies.

Social Media Services

UK guidance identifies certain social media services that are within scope of the DST,

which include: “social or professional networks[,] blogging or discussion platforms[,] video or

90

Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond, Budget 2018: Philip Hammond’s speech (Oct. 29, 2018)

(emphasis added).

91

See, e.g., Alex Hern, UK to impose digital sales tax despite risk of souring US trade talks, THE GUARDIAN (Mar.

11, 2020), https://www.theguardian.com/media/2020/mar/11/uk-to-impose-digital-sales-tax-despite-risk-of-souring-

us-trade-talks (“European digital successes such as Spotify and Monzo are excluded because they do not operate

“search engines, social media services and online marketplaces”).

92

Rory Cellan-Jones, Budget 2018: Who will pay the Digital Services Tax?, BBC NEWS (Oct. 30, 2018),

https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-46028715; Joe Kennedy, Digital Services Taxes: A Bad Idea Whose Time

Should Never Come, I

NFORMATION TECHNOLOGY & INNOVATION FOUNDATION (May 13, 2019),

https://itif.org/publications/2019/05/13/digital-services-taxes-bad-idea-whose-time-should-never-come.

93

Joseph Johnson, Search engines ranked by market share in the United Kingdom (UK) as of June 2020, Statista

(Jul. 28, 2020), https://www.statista.com/statistics/280269/market-share-held-by-search-engines-in-the-united-

kingdom/.

16

image sharing platforms[,] dating platforms[,] [and] review platforms.”

94

This investigation

identified at least one U.S. headquartered company, which operates a social media service,

subject to the UK DST.

95

However, this investigation has not positively identified any UK

company that will be subject to the UK DST.

Online Marketplaces

This investigation identified at least two U.S. headquartered companies that operate

online marketplaces and are likely to be subject to the UK DST.

96

However, this investigation

has not positively identified any UK companies that will be subject to the UK DST.

UK guidance suggests that the UK DST will be interpreted in a manner so as to shield

UK companies from DST liability. Specifically, the UK government has stated that it “will

continue to give consideration to how the legislation applies to marketplace delivery fees and

whether that application is consistent with the policy rationale of the DST.”

97

If the UK applies

the DST in a manner excluding “marketplace delivery fees”, this would result in the exclusion of

companies such as Just Eat or Deliveroo, which are the few—if any—UK companies that might

otherwise be subject to the UK DST.

98

Because the UK DST targets select digital service activities where U.S. companies are

market leaders, the UK DST is structured to discriminate against U.S. companies and target

U.S. companies with special, unfavorable tax treatment.

3. The UK DST Revenue Thresholds Discriminate Against U.S. Companies

As described in Section II, the UK DST applies only to companies with annual digital

services revenues over £500 million and “UK digital services revenues” over £25 million.

99

Statements by UK officials responsible for creation of the DST and UK policy documents

indicate that the DST revenue thresholds were designed to target U.S. companies.

In 2018, the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond stated that the DST “will

be a narrowly-targeted tax on the UK-generated revenues of specific digital platform business

94

HM Revenue & Customs, Guidance: Check if you need to register for Digital Services Tax, GOV.UK (Apr. 1,

2020), https://www.gov.uk/guidance/check-if-you-need-to-register-for-digital-services-tax.

95

Facebook Won’t Hit UK Advertisers With Digital Tax Costs, LAW360 (Sept. 4, 2020, 4:09pm),

https://www.law360.com/articles/1307667/facebook-won-t-hit-uk-advertisers-with-digital-tax-costs (Facebook, a

U.S.-headquartered company, addressed how it would handle the UK DST charge.).

96

UK News Team, Protecting your business from Digital Services Tax costs, COMMUNITY.EBAY.CO.UK (Oct. 8,

2020, 2:52 pm), https://community.ebay.co.uk/t5/Announcements/Protecting-your-business-from-Digital-Services-

Tax-costs/ba-p/6701162 (eBay, a U.S.-headquartered company, reported that “eBay is one of the marketplaces

which will have to pay the new tax[.]”).

97

Budget 2020, HC 121, March 2020, ¶ 2.205.

98

Tim Bradshaw, UK aims to raise ₤500m a year through digital services tax, FIN. TIMES (Mar. 11, 2020),

https://www.ft.com/content/a2ccbba8-5f0e-11ea-b0ab-339c2307bcd4.

99

Finance Act (2020) § 46, c. 14 (UK); HM Revenue & Customs, Policy paper – Digital Services Tax

(March 11, 2020).

17

models. It will be carefully designed to ensure it is established tech giants – rather than our tech

start-ups - that shoulder the burden of this new tax.”

100

As previously described in this report,

such a reference to “established tech giants” is an allusion to leading U.S. digital service

companies. A key aspect of this design is the selected revenue thresholds, which as addressed in

Section II, largely include U.S. companies but exclude UK companies.

Comments submitted in this investigation reinforce the assessment that the UK DST

thresholds are discriminatory against U.S. companies. As noted by one comment, “[a] host of

successful U.S. technology companies meet these thresholds, while very few (if any) domestic

companies meet both thresholds.”

101

Another comment in this investigation noted that the UK

DST’s “high gross revenue thresholds . . . effectively discriminate against large digital services

[companies] . . . of which many are headquartered in the [U.S.].”

102

A third comment added that

“[t]he practical effect of the tax will be that a handful of U.S. companies will contribute the

majority of the tax revenue.”

103

This is not an abstract issue, as described by a comment which noted that such thresholds

place “U.S. travel technology companies at a disadvantage relative to [online travel agents] in

local markets, who may command a large local market share . . . but which fall just under the

current DST revenue thresholds and therefore will not pay any DST.”

104

Another comment

noted that with respect to advertising services, “DSTs have the effect of shifting advertising

spending away from larger U.S. companies with revenues that exceed the thresholds, to domestic

companies with digital advertising revenues that do not meet the thresholds”

105

—thus, unfairly

advantaging domestic companies against leading U.S. companies.

Furthermore, aside from separating large U.S. companies from others, there is no

particular significance to the DST threshold levels chosen by the UK.

106

Amplifying statements

by the UK contend that “[t]he thresholds are also based on an expectation that the value derived

from users will be more material for large digital businesses, which have established a large UK

100

Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond, Budget 2018: Philip Hammond’s speech (Oct. 29, 2018).

101

Jeff Paine, Asia Internet Coalition (AIC) Comments and Recommendations to USTR’s Initiation of Section 301

Investigations of Digital Services Taxes (DST), 3 (Jul. 15, 2020), https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=USTR-

2020-0022-0337; see also Interactive Advertising Bureau, Re: Docket No. USTR-2020-0022 (Jul. 15, 2020),

https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=USTR-2020-0022-0374 (“As a result of their success in the U.S. and

globally, many U.S. companies meet or exceed the revenue thresholds established by DSTs.”).

102

Dr. Matthias Bauer, European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE) Comment Letter: Initiation of

Section 301 Investigations of Digital Services Taxes (Jul. 14, 2020), https://beta.regulations.gov/comment/USTR-

2020-0022-0318.

103

Rachel Stelly, Comments of the Computer & Communications Industry Association (CCIA), 13 (Jul. 14, 2020),

https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=USTR-2020-0022-0329.

104

Travel Technology Association, Comment Letter Re: Initiation of Section 301 Investigations of Digital Services

Tax, 2 (Jul. 14, 2020), https://www regulations.gov/document?D=USTR-2020-0022-0323.

105

Alex Propes, Re: Docket No. USTR-2020-0022 (Jul. 15, 2020), https://www regulations.gov/document?D

=USTR-2020-0022-0374.

106

Joe Kennedy, Digital Services Taxes: A Bad Idea Whose Time Should Never Come, INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

& INNOVATION FOUNDATION (May 13, 2019).

18

user-base, and generate substantial revenues from that user base[,]”

107

and that “the revenue

thresholds provide an implicit measure of user created value. Marketplaces which generate less

than £500m of annual turnover are unlikely to benefit from large scale network effects from

having users on both sides of the platform.”

108

Such justifications are baseless. Not only has the

theory of “user created value” been thoroughly refuted, but as described by one analysis, “[i]t is

not clear why users suddenly create more value when a company gets beyond this size.”

109

Guidance pertaining to the revenue thresholds further clarifies that the thresholds are

intended to unfairly target leading U.S. companies. For example, in policy papers, the UK

government noted that “[t]he thresholds and allowance will apply on a group-wide basis, not on a

per business activity or per company basis[,]”

110

and that “[r]evenues will consequently be

counted towards the Digital Services Tax thresholds even if they are recognised in entities which

do not have a UK taxable presence for corporation tax purposes.”

111

The aim of these rules is to

ensure that leading U.S. firms’ revenues are captured by the UK DST. Thus, the revenue

thresholds chosen by the UK discriminate against and unfairly target U.S. companies.

B. THE UNITED KINGDOM’S DIGITAL SERVICE TAX IS UNREASONABLE BECAUSE IT IS

INCONSISTENT WITH INTERNATIONAL TAX PRINCIPLES

This investigation assesses that the UK DST is inconsistent with principles of

international taxation, including application to revenue rather than income, corporate income

taxation unconnected to a permanent establishment, retroactivity, and prevention of double

taxation.

1. The DST’s Application to Revenue Rather than Income Is Inconsistent

with International Tax Principles

The architecture of the international tax system reflects that corporate income (as defined

by domestic law), and not corporate gross revenue, is an appropriate basis for taxation. There

are over 3,000 bilateral tax treaties in effect, the majority of which are based on the OECD

Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital and on the UN Model Double Taxation

Convention between Developed and Developing Countries.

112

The OECD model treaty provides

disciplines on the taxation of “business profits” and other types of income streams, such as

dividends, interest, royalties, and capital gains. However, the OECD model treaty makes no

provision for taxes on gross revenues.

113

The UN model treaty likewise has disciplines on

107

HM Treasury, HM Revenue & Customs, Digital Service Tax: Consultation, § 6.7, Gov.UK (Nov. 2018).

108

HM Revenue & Customs, Online Marketplace - Overview, DIGITAL SERVICES TAX MANUAL, DST18100 (Aug.

5, 2020), https://www.gov.uk/hmrc-internal-manuals/digital-services-tax/dst18100.

109

Joe Kennedy, Digital Services Taxes: A Bad Idea Whose Time Should Never Come, INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

& INNOVATION FOUNDATION (May 13, 2019).

110

HM Treasury, HM Revenue & Customs, Digital Service Tax: Consultation, § 6.8, Gov.UK (Nov. 2018).

111

HM Revenue & Customs, Policy paper – Digital Services Tax (March 11, 2020).

112

BRIAN J. ARNOLD, AN INTRODUCTION TO TAX TREATIES 1 (2015).

113

OECD, Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital: Condensed Version 2017, OECD PUBLISHING, art. 7,

Dec. 18, 2017 (on business profits); see id. arts. 6, 8-21.

19

business profits and numerous other types of income but has no provision for taxes on gross

revenues.

114

The U.S. model tax treaty, as well as scores of bilateral tax treaties to which the

United States is a party, including the U.S.-U.K. Tax Treaty, have the same scope in this

regard.

115

Other sources confirm that prevailing tax policy principles support the taxation of

corporate income but not of gross revenue, for example, one analysis noted that most European

countries rejected revenue-based taxation in the 1960s.

116

Chapter 2 of the OECD publication Addressing the Tax Challenges of the Digital

Economy, entitled “Fundamental Principles of Taxation,” recognizes two bases for corporate

taxation—income and consumption.

117

The UK DST is neither. As described by the OECD,

income taxes are “imposed on net profits, that is receipts minus expenses.”

118

The UK DST,

however, is a tax on gross revenue.

119

The OECD notes that “[i]ncome taxes are levied at the

place of source of income.

120

UK policy papers make clear that revenues are not distinguished

by the place of source of income, rather, solely based on the revenues relationship to a covered

business model: “taxable revenues will include any revenue earned by the group which is

connected to the social media service, search engine or online marketplace, irrespective of how

the business monetises the service.”

121

Nor is the DST a consumption tax. Consumption taxes “find their taxable event in a

transaction, the exchange of goods and services for consideration either at the last point of sale to

the final end user (retail sales tax and VAT), or on intermediate transactions between businesses

(VAT)[,]”

122

and “are levied at the place of destination (i.e.[,] the importing country).”

123

The distinction between the UK DST and a consumption tax is most apparent in the case

of online advertising. Under the UK DST, revenues are taxable when “the revenues are online

advertising revenues” and “the advertising is viewed or otherwise consumed by UK users.”

124

114

See United Nations, Model Double Taxation Convention Between Developed and Developing Countries, art. 7,

2017 (setting out disciplines on taxes of business profits); id. arts. 6, 8-21 (covering other types of income).

115

See Dep’t Treasury, United States Model Income Tax Convention, art. 2, 2016 (setting out disciplines on “total

income, or on elements of income”); id. art. 7 (establishing disciplines on taxes of “business profits”); Convention

for the avoidance of double taxation and the prevention of fiscal evasion with respect to taxes on income and on

capital gains, with exchange of notes, U.K.-U.S., Jul. 24, 2001, 2224 U.N.T.S. 247 (amended Jul. 19, 2002)

(hereinafter “U.S.-U.K. Tax Treaty”).

116

Daniel Bunn, A Summary of Criticism of the EU Digital Tax, Tax Foundation (Oct. 22 2018),

https://taxfoundation.org/eu-digital-tax-criticisms/.

117

OECD, Addressing the Tax Challenges of the Digital Economy, ch. 2: “Fundamental Principles of Taxation,” at

32-47 (2014).

118

Id. at 33.

119

Id. at 32.

120

Id. at 32.

121

HM Revenue & Customs, Policy paper: Digital Services Tax (Mar. 11, 2020),

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/introduction-of-the-digital-services-tax/digital-services-tax.

122

OECD, Addressing the Tax Challenges of the Digital Economy, ch. 2: “Fundamental Principles of Taxation,” at

32 (2014).

123

Id.

124

Finance Act (2020) § 41, c. 14 (U.K.).

20

However, such viewers are not a party to the transaction between advertisement purchaser and

advertiser that constitutes the transaction which generates revenue. In order to attempt to include

the user or viewer in the analysis of the place of destination, the location of the advertisement

purchaser and advertiser become irrelevant under the UK DST’s analysis. Simply explained:

“[s]ince viewers don’t pay anything to tech firms, the attribution of advertising and other

revenues (perhaps paid by firms in New York or Paris) to the UK will be arbitrary.”

125

For comparison, the UK already employs a value added tax (VAT) scheme, which is

charged on “most goods and services,”

126

such as: “business sales - for example when you sell

goods and services[,] hiring or loaning goods to someone[,] selling business assets[,]

commission. . . [and] ‘non-sales’ like bartering, part-exchange and gifts[.]”

127

However, the UK

VAT is separate and distinct from the UK DST. Thus, while the UK attempts to make the DST

sound like a consumption tax

128

—the UK DST is not—it is a gross revenue tax inconsistent with

the principles of corporate income taxation.

In conclusion, analysis of the UK DST reveals that the DST’s application to revenue

rather than income is inconsistent with principles of international corporate taxation.

Additionally, the UK DST conflates key elements of international corporate taxation, which is

unreasonably inconsistent with principles of international corporate taxation.

2. The UK DST Results in Double Taxation

The UK DST is inconsistent with the tax principle of avoiding double taxation. Avoiding

double taxation, i.e., preventing the same income being taxed twice, is a foundational principle

of the international tax system.

129

According to the OECD, the “harmful effects on the exchange

of goods and services and movements of capital, technology and persons” of double taxation

“are so well known that it is scarcely necessary to stress the importance of removing the

obstacles that double taxation presents[.]”

130

Both tax treaties and model tax treaties alike make

125

Gary Clyde Hufbauer & Zhiyao (Lucy) Lu, UK Money Grab: Proposed Digital Tax, Peterson Institute for

International Economics (Nov. 1, 2018), https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/uk-money-

grab-proposed-digital-tax.

126

Tax on shopping and services, GOV.UK, https://www.gov.uk/tax-on-shopping.

127

Businesses and charging VAT, GOV.UK, https://www.gov.uk/vat-businesses.

128

See, e.g., Finance Act (2020) § 41, c. 14 (U.K.); HM Revenue & Customs, Policy paper: Digital Services Tax

(Mar. 11, 2020) (describing the UK DST as a “2% tax on the revenues of search engines, social media services and

online marketplaces which derive value from UK users.”) (emphasis added); HM Revenue & Customs, Common

Sources of Revenue from Digital Services Activities, DIGITAL SERVICES TAX MANUAL, DST24000 (Aug. 5, 2020),

(annotating “Commission fees received for facilitating transactions between users”) (emphasis added).

129

See, e.g., OECD, Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital: Condensed Version 2017, OECD

PUBLISHING, introduction (Dec. 18, 2017) (“International juridical double taxation can be generally defined as the

imposition of comparable taxes in two (or more). States on the same taxpayer in respect of the same subject matter

and for identical periods.”).

130

OECD, Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital: Condensed Version 2017, OECD PUBLISHING,

introduction (Dec. 18, 2017).

21

clear that one of their primary objectives is the elimination of double taxation between

countries.

131

First, because of the gross-revenue design of the UK DST, leading U.S. companies may

be subject to both national taxes, such as the UK Corporation Tax, as well as the DST.

132

The

structure of the UK DST also makes it more likely that the UK DST will not be within scope of

the over 3,000 bilateral tax treaties in effect, the majority of which are based on the OECD

Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital and on the UN Model Double Taxation

Convention between Developed and Developing Countries.

133

Accordingly, it is highly likely

that the UK DST will result in double taxation.

Second, the UK DST’s broad definition of revenues makes it likely that revenues subject

to the UK DST will also be subject to digital service taxes or other taxes adopted by other taxing

jurisdictions. Digital services taxes adopted or under consideration by dozens of countries and

other jurisdictions take many forms, and as noted by HM Revenue & Customs: each

jurisdiction’s DST, or similar tax, employs a mechanism of taxation.

134

These divergent taxes

and methods of taxation not only increase compliance burdens, but also make it more likely that

multiple jurisdictions will partially, if not completely, overlap.

Advocates for the UK DST note that the UK DST contains a provision which authorizes

tax relief when the revenues are subject to a foreign tax similar to the UK DST.

135

In practice,

however, this provision provides minimal, if any, relief. As of August 5, 2020, HM Revenue &

Customs believed that only four digital services taxes were sufficiently similar in order to qualify

for any relief.

136

As one comment explained:

[T]he UK’s attempted solution is insufficient; it actually highlights the extent of

the problem. The proposed UK measure reduces the tax obligation by 50% in

certain circumstances where the same revenue is subject to a DST in another

jurisdiction. However, a 50% discount is arbitrary and is unlikely to eliminate the

risk of multiple taxation where the two DSTs have basic differences, such as

inconsistent tax rates, scope, and calculation methods. Also, the UK fix does not

address multiple taxation as a result of home country corporate income taxes or

131

See, e.g., OECD, Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital: Condensed Version 2017, OECD

PUBLISHING, preamble (Dec. 18, 2017); United Nations, Model Double Taxation Convention Between Developed

and Developing Countries, preamble, 2017; United States Model Income Tax Convention, preamble, 2016.

132

See Dr. Matthias Bauer, European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE) Comment Letter:

Initiation of Section 301 Investigations of Digital Services Taxes (Jul. 14, 2020),

https://beta.regulations.gov/comment/USTR-2020-0022-0318.

133

BRIAN J. ARNOLD, AN INTRODUCTION TO TAX TREATIES 1 (2015).

134

HM Revenue & Customs, Similar DSTs, DIGITAL SERVICES TAX MANUAL, DST43300 (Aug. 5, 2020).

135

Id.

136

Cf. KPMG, Taxation of the digitalized economy: developments summary, KPMG.COM (Oct. 27, 2020),

https://tax kpmg.us/content/dam/tax/en/pdfs/2020/digitalized-economy-taxation-developments-summary.pdf.

22

other taxes.

137

Thus, the UK DST is likely to result in double taxation, which is unreasonable.

3. The UK DST’s Retroactivity Is Inconsistent with International

Tax Principles

Tax certainty is an important principle of international taxation. In 2003, the OECD

Ottawa Taxation Framework identified “[c]ertainty and simplicity” as a key principle of

taxation.

138

In 2014, the OECD again identified “certainty and simplicity” as one of the

“fundamental principles of taxation” in its publication Addressing the Tax Challenges of the

Digital Economy.

139

In that publication, the OECD stated that “[t]ax rules should be clear and

simple to understand, so that taxpayers know where they stand.”

140

Additionally, the G20, of

which the UK is a participant, reaffirmed their commitment to “enhanced tax certainty” in the

G20 Osaka Leaders’ Declaration.

141

The UN has also endorsed providing “legal and fiscal

certainty as a framework within which international operations can confidently be carried on.”

142

Other sources confirm that tax certainty is an important principle of international taxation.

143

137

Information Technology Industry Council, Comment Letter on Docket No. USTR-2020-0022: Initiation of

Section 301 Investigations of Digital Services Taxes, 17 (July 15, 2020).

138

ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT, IMPLEMENTATION OF THE OTTAWA

TAXATION FRAMEWORK CONDITIONS: THE 2003 REPORT (2003).

139

OECD, Addressing the Tax Challenges of the Digital Economy, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting

Project, 30, OECD P

UBLISHING (2014).

140

Id. at 30.

141

G20 Osaka Leaders’ Declaration, 4, G20 (Jun. 29, 2019), https://g20.org/en/g20/Documents/2019-Japan-

G20%20Osaka%20Leaders%20Declaration.pdf (“We reaffirm the importance of . . . enhanced tax certainty.”).

142

United Nations, Model Double Taxation Convention Between Developed and Developing Countries, at iv, 2017;

see also B

RIAN J. ARNOLD, AN INTRODUCTION TO TAX TREATIES, at 11 (2015) (“One of the most important effects

of tax treaties is to provide certainty for taxpayers.”).

143

See, e.g., Implementation of the Ottawa Taxation Framework Conditions: The 2003 Report, ORGANISATION FOR

ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT (2003); Daniel Bunn, Elke Asen, Cristina Enache, Digital Taxation

Around the World, 2, T

AX FOUNDATION (May 27, 2020), https://files.taxfoundation.org/20200610094652/Digital-

Taxation-Around-the-World1.pdf (“Taxpayers deserve consistency and predictability in the tax code. Governments

should avoid enacting temporary tax laws, including tax holidays, amnesties, and retroactive changes. Many digital

tax policies are designed to be temporary, with some timelines tied to international agreements on changes.

Temporary tax policy creates uncertainty and challenges for both administration and compliance.”); OECD,

Mechanisms for the Effective Collection of VAT/GST When the Supplier is not Located in the Jurisdiction of

Taxation, 51, OECD P