1

An Updated User’s Guide to SOFR

The Alternative Reference Rates Committee

February 2021

2

Executive Summary

This note is intended to help explain how market participants can use SOFR in cash products. The

ARRC has stated that those who are able to use SOFR should not wait for forward-looking term rates

in order to transition, and the note lays out a number of considerations that market participants

interested in using SOFR will need to consider:

• Financial products either explicitly or implicitly use some kind of average of SOFR, not a single

day’s reading of the rate, in determining the floating-rate payments that are to be paid or

received. An average of SOFR will accurately reflect movements in interest rates over a given

period of time and smooth out any idiosyncratic, day-to-day fluctuations in market rates.

• Issuers and lenders will face a technical choice between using a simple or a compound average of

SOFR as they seek to use SOFR in cash products. In the short-term, using simple interest

conventions may be easier since many systems are already set up to accommodate it. However,

compounded interest would more accurately reflect the time value of money, which becomes

a more important consideration as interest rates rise, and it can allow for more accurate

hedging and better market functioning.

• Users need to determine the period of time over which the daily SOFRs are observed and

averaged. An in advance structure would reference an average of SOFR observed before the

current interest period begins, while an in arrears structure would reference an average of

SOFR over the current interest period.

• SOFR in advance is operationally easier to implement, but SOFR in arrears will reflect

movements in rates contemporaneously. An average of SOFR in arrears will reflect what

actually happens to interest rates over the period; however it provides very little notice before

payment is due. There have been a number of conventions designed to allow for a longer

notice of payment within the in arrears framework. These include payment delays, lookbacks,

and lockouts, and, as described in the note, different markets have successfully adopted each

of these. The note also discusses conventions for in advance payment structures and hybrid

models that can substantially reduce the basis relative to in arrears while still providing

borrowers the same length of notice that they have with LIBOR.

The note also explains the interaction between SOFR and the type of forward-looking term rates

that the ARRC has set a goal of seeing produced once SOFR derivative markets develop sufficient

depth. While these term rates can be a useful tool for some and an integral part of the new

ecosystem, hedging these rates will also tend to entail more costs than using SOFR directly and their

use must be consistent with the functioning of the overall financial system. For this reason, the

ARRC sees some specific productive uses for a forward-looking SOFR term rate, in particular as a

fallback for legacy cash products referencing LIBOR and in loans where the borrowers otherwise

have difficulty adapting to the new environment.

3

Background

In 2014, the Federal Reserve convened the Alternative Reference Rates Committee (ARRC) and

tasked the group with identifying an alternative to U.S. dollar LIBOR that was a robust, IOSCO-

compliant, transaction-based rate derived from a deep and liquid market. In 2017, the ARRC fulfilled

this mandate by selecting the Secured Overnight Financing Rate, or SOFR. SOFR is based on

overnight transactions in the U.S. dollar Treasury repo market, the largest rates market at a given

maturity in the world. National working groups in other jurisdictions have similarly identified

overnight nearly risk-free rates (RFRs) like SOFR as their preferred alternatives.

SOFR has a number of characteristics that LIBOR and other similar rates based on wholesale term

unsecured funding markets do not:

• It is a rate produced by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York for the public good;

• It is derived from an active and well-defined market with sufficient depth to make it

extraordinarily difficult to ever manipulate or influence;

• It is produced in a transparent, direct manner and is based on observable transactions, rather

than being dependent on estimates, like LIBOR, or derived through models; and

• It is derived from a market that was able to weather the global financial crisis and that the

ARRC credibly believes will remain active enough in order that it can reliably be produced in

a wide range of market conditions.

However, SOFR is also new, and many are unfamiliar with how to use it. SOFR is also an overnight

rate, and while the ARRC believes that most market participants can adapt to this by using compound

or simple averaging over the relevant term, the ARRC has at the same time set a goal of seeing an

administrator produce a forward-looking term rate based on SOFR derivatives (once these markets

develop to sufficient depth) in order to aid those cash market participants who may have greater

difficulty in adapting to an overnight rate.

The national working groups in the other currency jurisdictions each independently reached the same

conclusion that there were no viable robust term rate alternatives to LIBOR. Like the ARRC, each

has chosen either an unsecured or secured overnight rate, depending on the characteristics of their

national markets (see Table 1).

1

Table 1: Selected RFRs

U.S. Dollar

SOFR

Overnight secured repo rate

Sterling

SONIA

Overnight unsecured rate

Japanese Yen

TONA

Overnight unsecured rate

Euro

ESTER

Overnight unsecured rate

Swiss Franc

SARON

Overnight secured repo rate

1

Further information on the work of each of the national working groups in other currency jurisdictions can be found in

the FSB’s Progress Report on Reforming Major Interest Rate Benchmarks

, October 2017.

4

This note is intended to help explain how market participants can use SOFR in cash products and to

explain the forward-looking term rates the ARRC seeks to see published in the future and where the

ARRC believes those rates can be most productively used. The term rates can be a useful tool for

some and an integral part of the new ecosystem; but their use also needs to be consistent with the

functioning of the overall financial system. In particular, those who are able to use SOFR should not

wait for the term rates in order to transition.

2

The LIBOR transition will be challenging, and it is not

in the interest of market participants to put off taking action nor can the ARRC guarantee that an

administrator can produce a robust, IOSCO-compliant forward-looking term rate before LIBOR

stops publication. The ARRC sees some specific uses, in particular as a fallback for legacy cash

products referencing LIBOR and in loans where the borrowers otherwise have difficulty in adapting

to the new environment, where the term rates can be most productively used. For many other

purposes, the ARRC believes it should be possible to use compound or simple averages of SOFR and

that many users will come to find it more convenient to do so once they become more familiar with

the new environment.

A.

SOFR

SOFR is published on a daily basis by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY), in

cooperation with the Office of Financial Research, and reflects the cost of overnight borrowing and

lending in the U.S. Treasury repo market. Borrowing in this market reflects the best measure of the

private sector risk-free rate, because it is collateralized with U.S. Treasury securities, which the lender

returns once the borrower returns the cash borrowed. SOFR is a fully transactions-based rate and has

the widest coverage of any Treasury repo rate available, incorporating tri-party repo data, the Fixed

Income Clearing Corporation’s (FICC) GCF Repo data, and bilateral Treasury repo transactions

cleared through FICC.

3

Throughout 2020, the average daily volume of transactions underlying SOFR

was close to $1 trillion, representing the largest rates market at any given tenor in the United States.

Because of its range of coverage, SOFR is a good representation of general funding conditions in the

overnight Treasury repo market. As such, it reflects an economic cost of lending and borrowing

relevant to the wide array of market participants active in these markets, including not only broker-

dealers, but also money market funds, asset managers, insurance companies, securities lenders, and

pension funds. SOFR moves closely with other available repo rates and has tended to lie in the middle

of the range between other available repo rates. SOFR is generally a few basis points higher than rates

based only on tri-party transactions (such as the Bank of New York Mellon’s Treasury Tri-Party Repo

Index or the tri-party general collateral rate produced by FRBNY) but is generally lower and less

volatile than DTCC’s Treasury GCF Repo Index.

SOFR is calculated as a volume-weighted median of transaction-level data observed over the course

of a business day and is published on the FRBNY website at approximately 8:00 a.m. ET on the next

business day (see the accompanying figure). Looked at another way, SOFR is published on the day

that the overnight repo transaction is to be repaid rather than on the day that the transaction is entered

into. This publication schedule is due to the need to receive and fully vet the large amounts of data

2

The FSB has recognized that there may be a role for these types of forward-looking term rates, but the FSB has also

stated that it considers that the greater robustness of overnight rates like SOFR makes them a more suitable alternative

than these forward-looking term rates in the bulk of cases.

3

Further details on the structure of the U.S. Treasury repo market is available in the ARRC’s Second Report; see also

Bowman, Louria, McCormick and Styczynski (2017).

5

underlying SOFR before the rate is published. SOFR is published for the business days that the

Treasury repo market is open on, which are generally U.S. government securities secondary-market

trading days as determined by SIFMA

4

Although SOFR is published at about 8:00 a.m. ET, if any errors are subsequently discovered in the

transaction data in the calculation process that underlies it, or if any missing data subsequently became

available, then SOFR may be republished on the same day. In such cases, the affected rate may be

republished at approximately 2:30 p.m. ET. Rate revisions will only be effected on the same day as

initial publication and will only be republished if the change in the rate exceeds one basis point. To

date, there have been no rate republications for SOFR, but if at any time a rate is revised, a footnote

would indicate the revision.

5

4

SIFMA’s calendar of government securities trading days can be found at

https://www.sifma.org/resources/general/holiday-schedule/#US

.

5

Although SOFR has not been republished, on May 31, 2019, it was published based on FRBNY’s contingency rate

calculation methodology. This methodology involves the use of a highly detailed survey of Primary Dealer’s repo

borrowing activity conducted by FRBNY every day. More information and this event and a summary of FRBNY’s data

contingency procedures can be found on FRBNY’s website.

4/16/2019

SOFR is published on every U.S.

business day at approximately

8:00am EST. Because the Fed has

the ability to correct and republish

this rate until 2:30pm New York

City Time each day, users may wish

to reference the rate after this

time (e.g. 3:00pm)

The SOFR rate published on any

day represents the rate on repo

transactions entered into on the

previous business day and the date

associated with each rate reflects

the date of the underlying

transactions rather than the date

of publication.

6

In addition to producing SOFR, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York also publishes 30-day, 90-

day, and 180-day averages of SOFR and a SOFR Index daily on its website.

SOFR averages can be used either in advance or in arrears (concepts discussed further below) depending

on whether the averages are applied at the start or end of an interest period, but they are more likely

to be used in advance. They are calculated based on ISDA’s compound SOFR formula (described in

the Appendix), although the calculations for the averages may start on a weekend or holiday in order

to ensure that they cover a fixed number of days, and in that respect they differ from the standard

convention in the SOFR OIS market which would always start and stop on a business day. To allow

users to calculate a compound SOFR based on ISDA’s definitions over any start and ending date, for

example a monthly compound average based on the modified following business day convention,

FRBNY also publishes the SOFR Index. The Index, and how it can be interpolated to calculate a

compound average over a period that starts or stops on a nonbusiness day, is covered further in the

Appendix.

SOFR and the SOFR averages and Index are available both on FRBNYs website and also through an

API or through various data providers. Documentation for these rates can be found on the FRBNY

website, including policies and procedures and detailed evidence of IOSCO compliance. In addition

to SOFR, FRBNY produces a number of daily statistics, including the volume of transactions

underlying SOFR and selected percentiles of the rates observed across transactions, to aid market

participants in judging the quality of the rate.

B.

How Can Financial Products Use Overnight Rates?

Although many market participants have become accustomed to using term IBORs, they are a

relatively new phenomenon, and financial markets were able to function perfectly well before these

rates were widely adopted. There is in fact a long history of use of overnight rates in financial

instruments. In the United States, futures referencing the effective federal funds rate (EFFR) have

traded for more than 30 years and overnight index swaps (OIS) referencing EFFR have traded for

almost 20 years. Banks in the United States also have a history of offering loans based on the Prime

Rate, which is essentially an overnight rate, or overnight LIBOR, and there have been floating rate

Historical SOFR Data

FRBNY, in cooperation with the Office of Financial Research, began publishing

SOFR on April 3, 2018, but there is a longer history of repo rate data based on

several sources that have been made available by FRBNY. Prior to the start of

official publication, FRBNY also released data from August 2014 to March 2018

representing modeled, pre-production estimates of SOFR that are based on the

same basic underlying transaction data and methodology that now underlie the

official publication. While the full set of data sources required to calculate SOFR

did not exist prior to August 2014, FRBNY has also separately released a much

longer historical data series based on primary dealers' overnight Treasury repo

borrowing activity. Bowman (2017) provides evidence that this historical data

should be a good proxy for how a rate like SOFR would have behaved over a

longer period of time.

7

notes (“FRN”) issued based on the EFFR or, more recently, SOFR. Other countries have similar

experiences; for example, in Canada, most floating-rate mortgages are based on overnight rates.

Averaged Overnight Rates

Many financial products have used overnight rates as benchmarks, but one key thing to keep in mind

is that these financial products either explicitly or implicitly use some kind of average of the overnight

rate, not a single day’s reading of the rate, in determining the floating-rate payments that are to be paid

or received.

There are two essential reasons why financial products use an average of the overnight rate:

• First, an average of daily overnight rates will accurately reflect movements in interest rates

over a given period of time. For example, SOFR futures and swaps contracts are constructed

to allow users to hedge future interest rate movements over a fixed period of time, and an

average of the daily overnight rates that occur over the period accomplishes this.

• Second, an average overnight rate smooths out idiosyncratic, day-to-day fluctuations in market

rates, making it more appropriate for use.

This second point can be seen in Figure 1. On a daily basis, SOFR can exhibit some amount of

idiosyncratic volatility, reflecting market conditions on any given day, and a number of news articles

pointed to the jump in SOFR and other overnight repo rates in the fall of 2019. However, although

people often focus on the type of day-to-day movements in overnight rates shown by the black line

in the figure, it is important to keep in mind that the type of averages of SOFR that are referenced in

financial contracts are much smoother than the movements in overnight SOFR.

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

Figure 1: Movements in SOFR versus SOFR Averages

SOFR

30-Day SOFR

90-Day SOFR

180-Day SOFR

Percent

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York; Federal Reserve Board staff calculations. Data from August 2014 to

March 2018 represent modeled, pre-production estimates of SOFR.

8

The amount of daily volatility in SOFR can change over time and depends on a number of factors,

including the monetary policy framework and day-to-day fluctuations in supply and demand, but

regardless of these factors, using an averaged overnight rate smooths out almost all of this type of

volatility. As was emphasized in the ARRC’s Second Report and is still the case today even over the

year end, a three-month average of SOFR is less volatile than 3-month LIBOR (Figure 2). This was

true even in 2019 over the period when overnight repo rates experienced their short spike in volatility.

Compound versus Simple Averaging

Although financial products will all tend to use an averaged overnight rate, they may exhibit some

technical differences in how these averages are calculated. The choice of a particular averaging

convention need not affect the overall rate paid by the borrower, because the differences between

them are generally small and other terms can be adjusted to equate the overall cost, but nonetheless

issuers and lenders will face a technical choice between using a simple or a compound average as they

seek to use SOFR in cash products. Since this is a source of confusion for some, we will explain both

here.

Simple and compound averages reflect a technical difference in how interest is accrued by using either

simple or compound interest. Financial markets participants have developed a number of conventions for

calculating the amount of interest owed on a loan or financial instrument.

6

One area where this is

the case is in the choice convention between simple versus compound interest:

• Simple interest is a long-standing convention, and in some respects is easier from an operational

perspective. Under this convention, the additional amount of interest owed each day is

calculated by applying the daily rate of interest to the principal borrowed, and the payment

due at the end of the period is the sum of those amounts.

6

Some of those conventions were developed before modern computing made such calculations routine, at a time when

interest had to be calculated manually or by looking up the answer in tables. As computing has become widespread, new

conventions have developed, but in many cases both older and newer conventions coexist in the market.

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

Figure 2: 90-Day Average SOFR Versus 3-Month LIBOR

3-Month Libor 90-Day Average SOFR

Percent

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, ICE Benchmarks Administration; Federal Reserve Board staff calculations.

Data from August 2014 to March 2018 represent modeled, pre-production estimates of SOFR.

9

• Compound interest recognizes that the borrower does not pay back interest owed on a daily basis

and it therefore keeps track of the accumulated interest owed but not yet paid. The additional

amount of interest owed each day is calculated by applying the daily rate of interest both to

the principal borrowed and the accumulated unpaid interest.

From an economic perspective, compound interest is the more correct convention. For example, if

someone holds a bank account or money market fund paying overnight interest, then they receive

compounded interest. OIS markets also use compound interest, and thus instruments that use

compound interest will be easier to hedge. On the other hand, simple interest is easier to calculate

and many systems are designed around its use, for example, in the United States loan and short-term

FRN systems using overnight LIBOR or EFFR were built around the use of simple interest, and those

systems would require investment to change in order to incorporate compound interest calculations.

Beyond the math, it is perhaps most important to understand that the difference between the two

concepts is typically quite small at lower interest rates and over short periods of time. Any differences

can also be accounted for by adjusting the rate or margin. Historically, the difference between simple

and compounded interest on SOFR would have ranged between 0 and 6 basis points over the last two

decades (Figure 3), with the difference being larger when rates moved higher or when the payment

frequency was longer.

In the short-term, using SOFR with simple interest conventions may be easier since many loan and

FRN systems are already set up to accommodate it. However, compounded interest would more

accurately reflect the time value of money, which becomes a more important consideration as interest

rates rise, and it can allow for more accurate hedging. Of course, the choice between compounded

and simple interest is a decision between counterparties and would entail investments to update

systems in order to accommodate a compounded rate. The ARRC has recognized that either

convention can be used and that the choice will depend on the specifics of the product, including

trading and other conventions that may interact with the choice of interest accrual.

Apart from the choice between simple and compound interest, there are a number of other

conventions that need to be set, though they generally should have less economic impact on the

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020

Figure 3: Difference between Compound and Simple SOFR

1-Month Simple/Compound SOFR Basis

3-Month Simple/Compound SOFR Basis

Basis Points

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York; Federal Reserve Board staff calculations. Data from August 2014 to

March 2018 represent modeled, pre-production estimates of SOFR.

10

amount of interest payments. Amongst others, these include the choice of day count convention

(which determines how annualized rates are quoted) and how the rate is to be applied over weekends

and holidays (whether to use the rate on transactions taking place before the weekend or holiday,

which mirrors how repo markets operate, or the rate after). The Appendix provides the formulation

ISDA uses in its conventions and provides an example of the calculations behind compounded

interest.

C.

Notice of Payment (In Arrears versus In Advance and In Advance Hybrids)

Most of the contracts that reference LIBOR set the floating rate based on a value of LIBOR

determined before the beginning of the interest period. This convention is termed in advance because the

floating-rate payment due is set in advance of the start of the interest period. But not all LIBOR

contracts take this form; some LIBOR swaps reference a value of LIBOR determined at the end of the

interest period. This convention is termed in arrears.

7

These conventions are used with overnight rates also. An in advance payment structure based on an

overnight rate would reference an average of the overnight rates observed before the current interest

period began, while an in arrears structure would reference an average of the rate over the current

interest period. As noted above, an average overnight rate in arrears will reflect what actually happens to

interest rates over the period and will therefore fully hedge interest rate risk in a way that LIBOR or a

SOFR-based forward-looking term rate will not.

The tension in choosing between in arrears and in advance is that many borrowers will reasonably prefer

to know their payments ahead of time – well ahead of time for some borrowers – and so prefer in

advance, while investors will reasonably prefer returns based on rates over the interest period (i.e., in

arrears) and will tend to view rates set in advance as “out of date.” Nonetheless, there is actually a tight

economic link between the two conventions – absent any changes in balance, the payments made on

a SOFR in advance loan or security are equal to the payments that would be made using SOFR in

arrears, but those payments are lagged by one interest period as shown in the next figure.

As a result, the two types of SOFR averages have moved closely together over time, as shown in

Figure 5. In terms of hedging general interest rate risk, both structures for using SOFR will reflect

7

Although this convention doesn’t necessarily have to imply that payment is made after the interest period has concluded,

payment will frequently be made 1-2 days after the period has ended and in that sense is in arrears relative to the end of

the interest period even though it is not legally in arrears relative to the terms of the contract.

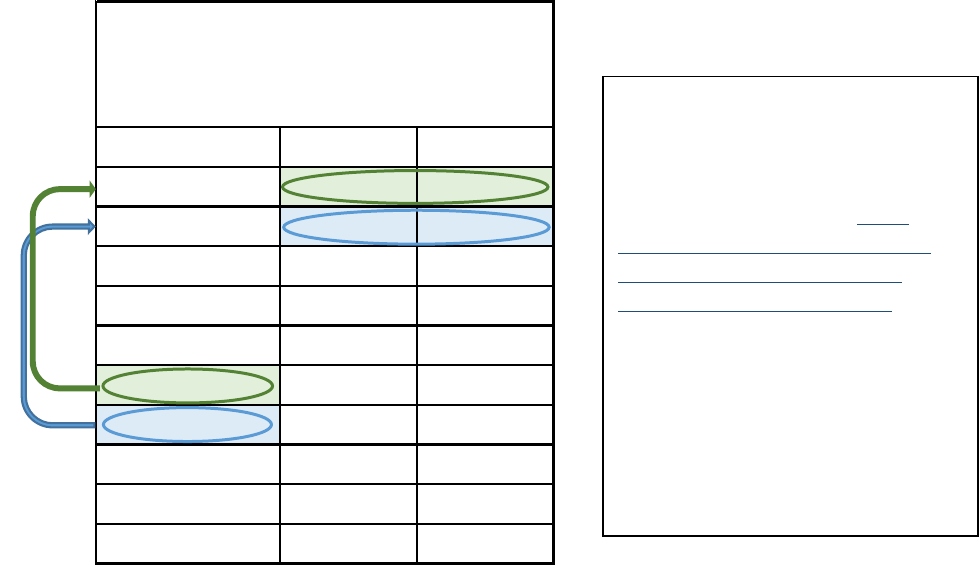

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

Month 1 Month 2 Month 3

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Month 11 Month 12

Figure 4: Comparing Payments on a 12-Month Floating-Rate Loan Using SOFR in Arrears versus in Advance

In Arrears

In Advance

Month 2 Avg SOFR

Month 12 Avg

Month 3 Avg SOFR

Month 10 Avg SOFR

Month 11 Avg SOFR

Month 1 Avg SOFR

Month 2 Avg SOFR Month 3 Avg SOFR

Month 10 Avg SOFR

Last Month's Avg

Month 1 Avg SOFR

Month 11 Avg

11

the moves in monetary policy that are the primary driver of money-market rates, although an in

advance structure will involve a one-period delay in the timing of when such moves are reflected.

Although lenders may view an in advance structure as less “up to date”, this isn’t an entirely new

problem: LIBOR itself can often quickly become out of date, by about the same magnitude that an

averaged overnight rate can. For example, in many loan contracts the borrower is able to draw on the

loan at any time during an interest period based on the LIBOR rate that was set at the start of interest

period. LIBOR rates are forward-looking, but even in a matter of weeks LIBOR can change radically

and can itself become outdated. The amount of basis this creates is shown in Figure 6, and historically

it has been quite large at times.

8

Figure 6 also shows the basis between a loan based on a compound

average rate set in advance and one set in arrears. While it may seem counterintuitive, the historical

magnitude of the basis that would have been caused by using a compound average overnight rate in

advance rather than in arrears is comparable to the potential basis involved in LIBOR.

8

Figure 6 shows the basis between the 1-month LIBOR rate set at the start of a monthly period and the 1-month

LIBOR rate prevailing 15 days later.

0%

1%

2%

3%

4%

5%

6%

7%

1998 2001 2004 2007 2010 2013 2016 2019

Figure 5: SOFR in Advance and in Arrears

Monthly SOFR in Arrears

Monthly SOFR in Advance

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York; Federal Reserve Board staff calculations. Data from

August 2014 to March 2018 represent modeled, pre-production estimates of SOFR.

-200

-150

-100

-50

0

50

100

150

200

1988 1992 1996 2000 2004 2008 2012 2016 2020

Figure 6: 2-Week Change in Monthly LIBOR versus the Difference

between EFFR in Arrears and in Advance

EFFR 1m arrears - EFFR 1m advance

2-Week Change in 1M LIBOR

Basis Points

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, ICE Benchmarks Administration; Federal Reserve Board staff calculations.

12

LIBOR loans also have other sources of basis. Many LIBOR loan contracts allow the borrower to

move between 1-, 3-, and 6-month LIBOR borrowing options at their discretion, which creates one-

way risk of basis to the lender. Using an in advance rate, the lender will face a comparable sort of

basis relative to in arrears if rates rise during the interest period. But as shown in Figure 7, that basis

has typically been smaller than the basis that lenders routinely take on in LIBOR loans.

The amount of basis between in arrears and in advance conventions will depend on whether interest

rates happen to be trending up or down over a given period. These differences will also depend on

how frequently payments are made: the difference between an average of rates over the past month

and an average of rates over the next month will typically be small, but the difference between an

average of rates over this year and an average of rates over the next year may be larger because rates

can move by more over a year than they typically might over a month. However, although in any

given period there may be differences and investors may either gain or lose from one structure relative

to the other, any movement in rates that are not reflected in the current interest period using an in

advance rate will be paid in the following interest period (see Figure 4). On average, any differences

will therefore tend to net out over the life of a loan or financial instrument if it lasts more than a few

years. As shown in Figure 8, even on a loan that lasts only a year, the basis relative to in arrears is

considerably smaller than the spot 1-month basis, and on a four-year loan the basis is minimal and

comparable to the difference between compound and simple rates.

0

50

100

150

200

250

1988 1992 1996 2000 2004 2008 2012 2016 2020

Figure 7: Comparison of Potential Bases Faced by Lenders

Basis between 3 and 1 Month LIBOR Borrower

Selection

Lender Basis between 3-Month Fed Funds in

Advance vs Arrears in a Rising Rate

Environments

Basis Points

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, ICE Benchmarks Administration; Federal Reserve Board staff calculations.

-125

-100

-75

-50

-25

0

25

50

75

100

1988 1992 1996 2000 2004 2008 2012 2016 2020

Figure 8: Basis between In Arrears and in Advance Loan by Loan Length

1-Month Advance Loan Basis

1-Year Advance Loan Average Basis

Basis Points

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, ICE Benchmarks Administration; Federal Reserve Board staff calculations.

13

Any potential differences in return to the lender can be further minimized, however, through a

“hybrid” structure that combines an in advance payment setting with adjustments, which is added

either to the subsequent payment or to outstanding principal, in order to provide an overall return to

the lender that is close to in arrears.

In these hybrid alternatives, the timing and frequency of payments would match the current structure

of LIBOR loans and the timing and frequency of payments in a basic SOFR in advance loan. In order

to make them easier to implement, there would be no adjustment at the time of the final payment in

these structures.

9

These hybrid structures are thus a form of an in advance loan, but with an adjusted

effective rate of interest.

There are two potential ways to adjust for the in advance rate set at the start of an interest period:

o Interest Rollover: Payments are set in advance and any missed interest relative to in arrears is rolled

over into the payment for the next period.

In this model, the payment for the period is set using an average of SOFR calculated at the start

of the interest period; however the amount of interest due is calculated based on the average of

SOFR over the interest period (in arrears), and any difference between the amount of interest paid

and the interest accrued is simply rolled over into the payment for the next interest period. In this

model, the remaining principal on the loan would not change.

o Principal Adjustment: Payments are set in advance, but principal and interest accrue in arrears.

In this model, the payment for the period is set using an average of SOFR calculated at the start

of the interest period (in advance); however the amount of that set payment that is applied to interest

will be based on the average of SOFR over the interest period (in arrears). In this model, the

remaining principal on the loan would change over time based on the difference between the in

advance and in arrears calculations for each period – if rates moved up over the interest period, then

more of the payment would go to cover interest expenses and remaining principal would be higher,

while if interest rates moved down then remaining principal would be lower.

The hybrid models will be unfamiliar to some, although it is not unusual to roll over certain payments

into the next period as suggested with the Interest Rollover model, and amortizing loans adjust the

amount of outstanding principal each period as suggested with the Principal Adjustment model. Both

of these hybrids are designed to give borrowers ample advance notice of the payments they will need

to make, while also structuring principal and interest to match the kind of in arrears return that investors

may prefer. As shown in Figure 9, a hybrid model can potentially minimize the basis faced by investors

while at the same time structuring payments in a way that borrowers could feel comfortable with. As

shown, a hybrid approach can have a smaller basis return relative to in arrears than even a forward-

looking term rate might because a forward-looking term rate incorporates expected changes in

9

This introduces some basis relative to in arrears, but as shown in Figure 9, the basis is small, and it is operationally

easier not to adjust for the last period. As can be seen from Figure 4, the difference in the return between an in advance

and in arrears loan will be based on the difference between the average SOFR rate at the start of the loan (which is what

the first payment of an in advance loan will be based on but would not be part of the payment of an in arrears loan) and

the average at the end of the loan (which is what the last payment that an in arrears loan will be based on but would not

be part of the payment in an in advance loan). With a hybrid structure, because the difference between in arrears and in

advance is made up through the adjustment for every period except the very last, the difference in return is essentially

limited to the difference between the average of SOFR at the start and end of the last payment period of the loan.

14

monetary policy, but will miss any unexpected changes, while hybrid loans will make up for any

unexpected changes through the adjustments.

Table 2 demonstrates how an Interest Rollover loan would have worked over 2007-08, when interest

rates declined sharply, and Table 3 does the same for the Principal Adjustment approach. Although

there would have been a 26 basis point difference between an in advance and an in arrears loan, the

return differential of the hybrid loans would have only been 2-3 basis points relative to in arrears.

-20

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

1988 1992 1996 2000 2004 2008 2012 2016 2020

Figure 9: Basis Between 1-Year Term Rate Loan and Interest Rollover Loan

1-Year Monthly Term Rate Loan Basis to in Arrears

1-Year Interest Rollover Loan Basis to in Arrears

Basis Points

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Federal Reserve Board staff calculations.

Interest Rollover

Hybrid

Interest Determination

Date

SOFR in

Arrears

SOFR in

Advance

Rollover

Adjustment

(bp)

Monthly Rate

(SOFR in Advance +

True Up)

4/26/2007 5.12% 5.21% -9 5.21%

5/28/2007 5.10% 5.12% -2

5.03%

6/27/2007 5.04% 5.10% -6 5.08%

7/27/2007 4.67%

5.04%

-37 4.98%

8/28/2007 4.94% 4.67% 27 4.30%

9/27/2007 4.60% 4.94% -34 5.21%

10/29/2007 4.25% 4.60% -35 4.26%

11/28/2007 3.90% 4.25% -35 3.90%

12/28/2007 3.45% 3.90% -45 3.55%

1/29/2008 2.59% 3.45% -86 3.00%

2/28/2008 1.78% 2.59% -81

1.73%

3/31/2008 2.12%

1.78% 34 0.97%

Annualized Rate of Return 3.96% 4.22% 3.94%

Basis to in Arrears (bp) --- -26 2

Table 2: Example of Interest Rollover approach on a 1-year loan over the steep drop in

rates in 2007-08

15

Interest

Determination

Date

SOFR in

Arrears

SOFR in

Advance

Difference

(bp)

Monthly

Rate

(SOFR in

Advance)

Principal

(Diff. Applied to

Principal)

4/26/2007 5.12% 5.21% -9 5.21% $1,000,000.00

5/28/2007 5.10% 5.12% -2 5.12% $999,925.00

6/27/2007 5.04% 5.10% -6 5.10% $999,908.33

7/27/2007 4.67% 5.04% -37 5.04% $999,858.34

8/28/2007 4.94% 4.67% 27 4.67% $999,550.05

9/27/2007 4.60% 4.94% -34 4.94% $999,774.95

10/29/2007 4.25% 4.60% -35 4.60% $999,491.68

11/28/2007 3.90% 4.25% -35 4.25% $999,200.16

12/28/2007 3.45% 3.90% -45 3.90% $998,908.73

1/29/2008 2.59% 3.45% -86 3.45% $998,534.14

2/28/2008 1.78% 2.59% -81 2.59% $997,818.52

3/31/2008 2.12% 1.78% 34 1.78% $997,144.99

Annualized

Rate of Return

3.96% 4.22% 3.93%

Basis to in

Arrears (bp)

--- -26 3

Table 3: Example of Hybrid Principal Adjustment approach on a 1-year loan over the

steep drop in rates in 2007-08

Principal Adjustment

Hybrid

16

D. In Arrears Conventions

Given the timing of when SOFR is published, the borrower would only have a few hours’ notice

before payment was due using a pure in arrears structure. Most borrowers would need more time than

this, and there typically is some convention when using an in arrears structure that gives borrowers

sufficient notice of the amount due before they are required to make a payment. There have been a

number of conventions developed in order to allow for this, which we illustrate in Table 4 and describe

in more detail below.

o Plain Arrears: As shown in Table 4, under a pure in arrears structure, the SOFR rate for each given

day in the interest period would be applied to calculate interest for that business day, and interest

would be paid on the first day of the next interest period.

Given the publication timing for SOFR and most other RFRs, this has the disadvantage of

requiring payment on the same day that the final payment amount is known, and as a result it is

often not operationally practical.

Day 1

(First Day of

Interest Period)

Day 2 …

Day T-2 Day T-1

Day T

(Last Day of

Interest Period)

Day T+1

(First Day of

Next Period)

Day T+2

SOFR for

Day 1

Published

SOFR for

Day T-3

Published

SOFR for

Day T-2

Published

SOFR for

Day T-1

Published

SOFR for

Date T

Published

Plain Arrears

Use SOFR for

Day 1

Use SOFR for

Day 2

…

Use SOFR for

Day T-2

Use SOFR for

Day T-1

Use SOFR for

Day T

Payment Due

Use SOFR for

Day 1

Use SOFR for

Day 2

…

Use SOFR for

Day T-2

Use SOFR for

Day T-1

Use SOFR for

Day T

Payment Due

Use SOFR for

Day 1

Use SOFR for

Day 2

…

Use SOFR for

Day T-2

Use SOFR for

Day T-1

Use SOFR for

Day T-1

Payment Due

Use SOFR for

Day 0

Use SOFR for

Day 1

…

Use SOFR for

Day T-3

Use SOFR for

Day T-2

Use SOFR for

Day T-1

Payment Due

Table 4: Models for Using SOFR in Arrears

Arrears with

Payment

Delay

Arrears with

1-Day

Lockout

Arrears with

1-Day

Lookback

OIS generally settle

at T+2

17

o Payment Delay: Interest is calculated in the same way as in a plain arrears framework, with the

SOFR rate for each given day in the interest period applied to calculate interest for that business

day, but interest is paid k days after the start of the next period.

The payment delay structure matches and is easily hedged with standard SOFR OIS swaps, which

generally use a payment delay to settle 2 days after the end of the interest period (often referred

to as “T+2”). The advantage of this structure is that it gives more time for payment while still

reflecting the movements in interest rates over the full interest period. The fact that payment is

delayed would be reflected in the rate charged on the instrument, but nonetheless some investors

may dislike any delay or find that the payment timing introduces mismatches with other payments.

o Lockout or Suspension Period: For most days during the interest period, interest is again calculated in

the same way as in a plain arrears framework, with the SOFR rate for each given day applied to

calculate interest for that business day; however, the SOFR rate applied for the last k days of the

interest period is frozen at the rate observed k days before the period ends.

A 2-5 day lockout has been used in some SOFR FRNs. A lockout allows the final interest amount

due to be known k days in advance of the payment date, but for most of the interest period the

daily interest rate applied will correspond to the most recent published value of the SOFR, which

brings the calculation of net asset value and discounting closer to par value and may be important

to some investors. A lockout does create some hedging basis relative to the market standard SOFR

OIS structure, because it effectively skips the last k days of rates each interest period. However,

dealers may be able to offer customized over-the-counter derivatives with lockouts to facilitate

client hedging, and the investors who have tended to prefer a lockout structure may be less likely

to hedge these investments. Because a lockout is designed to provide advance notice of payment

only at the end of an interest period, it also may not be the best convention for a loan contract,

where the loan could be repaid at any point in time and not only at the end of an interest period.

o Lookback: For each day in the interest period, the SOFR rate from k business days earlier is used

to accrue interest.

A 3-5 day lookback has been used in SONIA FRNs and is also used in many SOFR FRNs. Market

participants may find a lookback helpful when there is a need to calculate interest accruing during

an interest period, for example primary and secondary market trading or prepayments, and where

more time is needed for such calculations.

There are actually several forms of lookbacks, which we lay out below.

Lookback without observation shift

If the lookback is for k days, then the observation date is k business days prior to the interest date.

In a lookback without an observation shift, all other elements of the calculation are kept the same

and the reference to a previous SOFR rate is the only change made.

18

Using an example of a 5-day lookback without observation shift in calculating interest for Tuesday,

July 2, the SOFR rate for June 25 (5 business days prior to July 2) would be applied for 1 business

day until Wednesday, July 3, while in calculating interest for Wednesday, July 3, the SOFR rate for

June 26 (5 business days prior to July 3) would be applied for 2 business days until Friday, July 5.

10

If the interest date is t, then a 5-day lookback will use the SOFR rate from the observation date

t-5 (r

t-5

) and it will apply that rate for the number of calendar days until the next business day

following date t (n

t

). The effective rate (i

t

), which is the rate that is used in calculating daily accruals,

is the SOFR rate on the observation date (r

t-5

) multiplied by the number of days the rate applies

for (n

t

) and divided by the standard U.S. money market daycount convention of N =360.

Lookback with observation shift

A lookback with observation shift also applies the SOFR rate from some fixed number of business

days prior to the given interest date, but in contrast to a lookback without a shift, it applies that

rate for the number of calendar days until next business date following the observation date.

10

The ARRC has released a set of spreadsheets along with these technical Appendices in order to aid market participants

as they test their implmentation of various conventions. An example of a 5-business day lookback is included in the file

ARRC BWLG Example - Lookback without Observation Shift.xlsx, and a segment of the spreadsheet is shown below.

As in the example above, in order to implement a lookback without observation shift, the only change in calculations in

the spreadsheet relative to no lookback is that the observation date is 5-business days earlier than the interest date.

FRBNY SOFR DATA

Mon, Jun 24, 2019 1 2.39

Tue, Jun 25, 2019 1

2.41

Wed, Jun 26, 2019 1 2.43

Thu, Jun 27, 2019 1

2.42

Fri, Jun 28, 2019 3

2.5

Mon, Jul 1, 2019

1 2.42

Tue, Jul 2, 2019

1 2.51

Wed, Jul 3, 2019 2 2.56

Fri, Jul 5, 2019 3

2.59

Mon, Jul 8, 2019 1

2.48

Tue, Jul 9, 2019 1 2.45

DATE

RATE

(PERCENT)

Calendar Days

Until Next

Business Day

Lookback without observation shift:

The date that the SOFR rate is pulled

from (the observation date) is k

business days before the date that

interest is applied (the interest date)

and is applied for the number of

calendar days until the next business

day following the interest date.

Example of a 5-business day

lookback: The rate for June 25 is

applied on July 2 for one day, while

the rate on June 26 is applied on July

19

Continuing the example, using a 5-day lookback with observation shift in calculating interest for

Tuesday, July 2, the SOFR rate for June 25 (5 business days prior to July 2) would be applied for

1 business day until Wednesday, July 3, while in calculating interest for Wednesday, July 3, the

SOFR rate for June 26 (5 business days prior to July 3) would be applied for 1 business day.

As discussed in the following box, the fallbacks in ISDA’s IBOR protocol incorporate a

lookback with observation shift, although a somewhat different variant than described here.

Interest-Period Weighted Observation Shift

As just described, with an observation shift, interest is accrued according to the number of days

in the observation period, which may differ from the number of days in the interest period. In

some instances, parties in the FRN market choose to calculate interest payments using the

annualized lookback rate with observation shift, but then to apply that annualized rate to the

number of days in the interest period. A version of this interest-period weighted observation shift

approach has also been noted as a potential convention by the Sterling Risk Free Rate Working

Group for the sterling loan market, though it is not the principle recommendation and is discussed

but not recommended in the ARRC’s conventions for business loans. One issue with this

approach, perhaps of particular importance to the loan market, is that it can at times result in a

negative daily accrual even if SOFR rates are positive. This approach, and potential methods of

accruing interest under it, are discussed further in Appendix 4.

FRBNY SOFR DATA

Mon, Jun 24, 2019

1

2.39

Tue, Jun 25, 2019 1 2.41

Wed, Jun 26, 2019 1

2.43

Thu, Jun 27, 2019 1

2.42

Fri, Jun 28, 2019 3 2.5

Mon, Jul 1, 2019

1 2.42

Tue, Jul 2, 2019

1

2.51

Wed, Jul 3, 2019 2 2.56

Fri, Jul 5, 2019

3 2.59

Mon, Jul 8, 2019 1

2.48

Tue, Jul 9, 2019 1 2.45

Calendar Days

Until Next

Business Day

DATE

RATE

(PERCENT)

Lookback with observation shift: The

date that the SOFR rate is pulled from

(the observation date) is k business

days before the date that interest is

applied (the interest date) and is

applied for the number of calendar

days until the next business day

following the observation date.

Example of a 5-business day lookback

with observation shift: The rate for

June 25 is applied on July 2 for one

day, and the rate on June 26 is applied

on July 3 for one day.

20

A lookback with observation shift is one of the conventions that has been recommended by the ARRC

for FRNs.

11

However, the ARRC has recommended a lookback without shift for syndicated loans,

which aligns with the approach recommended by the Sterling Risk Free Rates Working Group for

Sterling markets. As discussed in the ARRC’s conventions, syndicated loans have several complicating

11

This convention is described under Two-Day Backward Shifted Observation Period and No Lockouts in the ARRC’s

SOFR Floating Rate Notes Conventions Matrix. See

https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/Microsites/arrc/files/2019/ARRC_SOFR_FRN_Conventions_Matrix.pdf

.

ISDA’s Lookback Structure

The fallback to compound SOFR in arrears that will be implemented through the ISDA protocol

will have a lookback with observation shift, but it will differ in some respects from the lookback

structures that is being used in SOFR cash products. In the structures laid out above, the start

and end dates of interest accrual are fixed and for each business day in the period the SOFR rate

from k days earlier is applied. In the ISDA lookback implementation, the fallback accrual start

date is instead shifted back in order to allow the choice on an end date that is at least k business

days before the LIBOR payment date, and the SOFR rate for each business day is applied. When

the starting date is set, the end date then is chosen based on a modified following business day

convention, for example, in a 3-month LIBOR swap, the end date will be 3-months modified

following from the start date.

Most of the time, the new start date will be k days before the original LIBOR accrual starting date

and the accrual calculations would equal those of the lookback with observation shift laid out in

this Users Guide; however, there will be occasions in which the start date in the ISDA structure

will be more than k days before, and also occasions when the end date will be more than k days

before the payment date.

As an example, consider a 1-month LIBOR interest period that starts on January 29, 2021 and

ends on February 26, 2021, with payment due that end date. A SOFR start date either 2 or 3 days

earlier then the LIBOR start date, January 27 or January 26, would still have an end date of

February 26, and a start date of Jan 25 would have a corresponding end date of Feb 25, which is

only one day before the payment date. In order to provide at least 2 business days’ notice, the

start date would need to begin on January 22, with a corresponding end date of Feb 22, which is

4 business days before the payment date.

Original Accrual

Start Date

Original Accrual

End Date

Payment Date

b

-3

b

-2

b

-1

b

0

b

1

…

b

T-2

b

T-1

b

T

b

T+1

Fallback Accrual

Start Date

Fallback Accrual

End Date

Fallback Accrual

Start Date

Fallback Accrual

End Date

is end date at least 2 business days

before the payment date?

is end date at least 2 business days

before the payment date?

21

features that FRNs do not – principal can typically be repaid at any time, and syndicated loans are

frequently traded between lenders and they do not trade clean.

The fact that principal may be repaid or that a lender may trade out of a loan before the end of an

interest period makes implementing an observation shift more difficult in the loan market. For

instance, in the example above, on July 3 interest is only charged for one day even though it would be

two days until interest was paid. A lender who bought in to the loan on July 3 and sold out on July 5

may consider that they have been less than fully compensated given that they have provided some

amount of principal for two days but only receive interest for one day. Or consider what was meant

to be a monthly loan that began on July 8 but was repaid the next day. Under a 5-business day

lookback with observation shift, the borrower would be charged for three day’s interest based on the

SOFR rate for Friday, June 28, even though they had only borrowed money for one day and should

therefore only be charged for one day’s interest.

Without trading or without early repayment, these discrepancies would average out and would be

inconsequential. Because principal is constant in FRNs (and because they trade clean, meaning that

the purchaser receives the full coupon), an observation shift is more easily implemented. With trading

and the possibility of early repayment, these kinds of discrepancies may be more problematic, and the

ARRC Business Loans Working Group members felt that a lookback with observation shift would

not be the most appropriate convention for the syndicated loan market.

12

Although each of these conventions have some benefit, in general lookback structures (with or

without an observation shift) have been most widely used. FRNs have tended to have a shorter

lookback period of 2-3 business days, while the ARRC’s conventions for business loans contemplate

a 5-business day lookback and securitizations using in arrears with a lookback might employ a longer

lookback period.

12

An analogy would be the difference between renting an apartment and staying at a hotel. Under a rental agreement,

rent is the same each month even though some months have 28 days and others have 31 days, but the differences

average out and people feel free to ignore them. In contrast, someone staying at a hotel is much more likely to take

offense if they are charged for 3 days but only stayed 1 day or if they are charged a weekend rate when they stayed on a

weekday.

0%

25%

50%

75%

100%

125%

150%

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60

Figure 10: Root Mean Spot Basis Relative of in Arrears Rates to

Term Rates by Reset Frequency and Lookback

3-Month

Reset

6-Month

Reset

Number of Business Days in Lookback

1-Month

Reset

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Federal Reserve Board staff calculations.

22

Regardless, any of these lookback lengths will generally produce more accurate results than a forward

looking term rate. Based on historical EFFR and EFFR OIS data, Figure 10 plots the root mean basis

of different lookback lengths relative to the root mean basis of a forward-looking term rate. For a

contract with a one-month reset frequency, a lookback of 9-10 days or less will be at least as accurate

as any potential term rate. For a three-month reset frequency, a lookback as long as a month will be

more or as accurate as a term rate, and for a six-month reset, the lookback

frequency could be up to two months.

23

E. In Advance Conventions

Relative to in arrears, in advance structures are easier to implement, but there are still some choices

involved implementing these structures. The two most familiar methods of implementing an in

advance structure are the last reset and last recent methods:

o Last Reset: Use the averaged SOFR over the last interest reset period as rate for current interest

period

o Last Recent: Use the averaged SOFR from a shorter recent period as rate for current interest period

Comparing these two in advance conventions, the last reset model is similar to a lookback model and

will more closely match the structure of an OIS (although the payment structure will be lagged). For

parties wishing to match payments (albeit, receiving the payment on the OIS contract prior to the due

date for the loan payment) a last reset may be preferred. On the other hand, the last recent model is

likely to have less basis relative to the in arrears average interest rate over the current interest period.

This can be seen in Figure 11, which compares the basis between different models of Last Reset/Last

Recent for different payment frequencies on a hybrid adjustable rate mortgage to a hypothetical in

arrears structure.

13

The ARRC’s Whitepaper on Using SOFR in Adjustable Rate Mortgages proposes

a last recent structure, with a 6-month reset based on either 30- or 90-day Average SOFR. As can be

seen in the figure, using a 30-day average with a 6-month reset comes close in terms of basis to an

even shorter 3-month last reset structure.

13

In these mortgage simulations, a hypothetical 5/1 Adjustable Rate Mortgage that refinances in year 8 of the mortgage

is considered, with floating rate payments based on historical values of EFFR. As described earlier, in these and

following simulations, the basis is calculated as the spread (expressed as an annual rate) that would need to be added to

the in advance instrument in order to equate the ex post net present value of payments received with the in arrears

instrument. Net present values are calculated using the internal rate of return on the in arrears instrument. A positive

basis implies that investors would have required added compensation to have broken even on the in advance instrument,

while a negative basis implies that investors would have gained from the in advance instrument and would have had to

rebate some of the interest received to have broken even relative to in arrears.

-30

-20

-10

0

10

20

30

1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009

Figure 11: Comparing Bases to In Arrears for Different Models of In

Advance Mortgages

Six Month Reset Based on 180-Day Average EFFR Six Month Reset Based on 90-Day Average EFFR

Six Month Reset Based on 30-Day Average EFFR

Basis Points

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Federal Reserve Board staff calculations.

24

F. The ARRC’s Conventions Recommendations Documents

The ARRC has produced several sets of convention and term sheet documents for specific cash

products, both in arrears (for FRNs, and syndicated and bilateral business loans) and in advance (for

intercompany loans and consumer products). The table below provides links to these documents. In

addition, Appendices 4-6 include draft term sheets for business loans based on simple interest in

arrears, SOFR in advance, and an Interest Rollover SOFR loan.

Table 5: ARRC Conventions and Term Sheet Documentation

Product

Conventions/Term Sheet Document

Floating Rate

Notes

Compound SOFR in Arrears with Lookback (No Observation Shift)

Compound SOFR in Arrears with Lookback and Observation Shift

Compound SOFR in Arrears with Payment Delay

Compound SOFR with Index Calculation

Syndicated

Business Loans

Compound SOFR in Arrears with Lookback

Simple SOFR in Arrears with Lookback

Bilateral Business

Loans

Compound SOFR in Arrears with Lookback

Simple SOFR in Arrears with Lookback

Intercompany

Loans

30- or 90-Day SOFR in Advance

Adjustable-Rate

Mortgages

30- or 90-Day SOFR in Advance

Student Loans

30- or 90-Day SOFR in Advance

25

G. The Interaction between SOFR and the Forward-Looking Term Rate

As noted above, the FSB has been clear in its assessment that financial stability will be enhanced if use

of forward-looking term rates is narrow and most market participants move toward use of RFRs,

while also recognizing the potential usefulness of forward-looking RFR-based term rates as a fallback

rate for legacy contracts and in cash markets in certain circumstances.

While the ARRC has set a goal of seeing a forward-looking term SOFR rate, production of a term rate

can only be guaranteed if most new products use SOFR directly, as otherwise SOFR derivatives

markets are unlikely to achieve or maintain the depth needed to produce a robust term rate. It is also

important that market participants are also clear on what the forward-looking term SOFR rate is

expected to be, and its relationship to the overnight SOFR, in order to understand where use of such

rates could be best made.

While the overnight Treasury repo market underlying SOFR is extraordinarily deep, term repo markets

are much thinner, and it would not be possible to build a robust, IOSCO-compliant rate directly off

the term Treasury repo market. As discussed in the ARRC’s Second Report, there is really no term

cash market in the United States with enough depth to build a reliable, robust, transactions-based rate

produced on a daily basis that would be able to meet the criteria that the ARRC set in choosing SOFR.

Therefore, the ARRC has proposed that a private administrator could construct a forward-looking

term rate based on SOFR derivatives markets once those markets develop enough liquidity. Because

SOFR derivative markets have developed quickly and are expected to achieve a very high degree of

liquidity, it is reasonable to expect that these markets will eventually be sufficiently liquid and robust

to construct a forward-looking term rate, but the timing cannot be guaranteed.

Under the ARRC’s proposal, the forward-looking term rate would be based on some combination of

SOFR futures and SOFR OIS transactions.

14

The ARRC has not endorsed a specific methodology

for producing these rates, but a recent working paper has laid out one potential methodology and the

authors have released a series of “indicative” term rates that may help to promote better understanding

as to how rates of this type might behave over time.

15

As liquidity in SOFR derivatives markets

continues to develop, the ARRC anticipates that private vendors will seek to produce one or more

forward-looking term rates for commercial use, which the ARRC has committed to evaluate with the

aim of recommending one such rate provided that it satisfies the ARRC’s criteria.

Any forward-looking term rates are expected to be equal or close to the underlying SOFR OIS curve.

An OIS contract involves exchanging a set of fixed-rate payments for a set of floating-rate payments

between two parties. The floating rate is a compound average of the overnight rate calculated over

the interest period, while the fixed rate is set at the start of the period. If we call

(

)

the fixed

rate on a 3-month OIS contract entered into at date t, then the 3-month forward-looking term rate

would be either equal to

() or close to it. The same would be true for the potential 1-month

14

These two markets are very tightly linked together. SOFR futures pay an average of SOFR over a given month or quarter,

for example, the average of SOFR realized over the month of June or the average over the first quarter of the year. SOFR

OIS pay the compounded average of SOFR over a fixed period of time, for example, a one-month OIS contract beginning

on March 15 would pay the compound average of SOFR realized over the period from March 15 to April 14.

15

See Heitfield and Park (2019), Inferring Term Rates from SOFR Futures Prices, FEDS discussion paper 2019-014.

Further description of the methodology as well as a data file that presents indicative forward-looking term rates derived

from end-of-day SOFR futures prices and compound averages of daily SOFR rates can be found in Heitfield and Park

(2019),

Indicative Forward-Looking SOFR Term Rates, a staff FEDS Note published April 14, 2019. These rates are

presented for informational purposes only and are not appropriate for use as reference rates in financial contracts.

26

or 6-month counterparts,

() and

(

)

. Figure 12 compares the indicative SOFR term

rate to an OIS rate referencing EFFR, and one can see that they move quite closely together.

In general, there will be a tight economic link between the forward-looking term rate and the

compound average of SOFR in arrears used as the floating rate in OIS contracts. The fixed rate is

set so that the OIS contract has zero value at the time it is entered into; that is, the value of receiving

the fixed rate is exactly equal to the value of receiving the floating rate. In this sense, the fixed rate

(the forward-looking term rate) will be economically equivalent to the corresponding expected

compound average of SOFR. We don’t have a long history of SOFR OIS yet, but Figure 13 shows

this type of link between EFFR OIS and compound averages of the EFFR, as a proxy.

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

Jun-18 Oct-18 Feb-19 Jun-19 Oct-19 Feb-20 Jun-20 Oct-20

Figure 12: Comparing an Indicative SOFR Term Rate to EFFR OIS

3-Month Indicative SOFR Forward-Looking Term Rate

3-Month Fed Funds OIS

Percent

Source: Refinitiv, Federal Reserve Board staff calculations.

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

1988 1992 1996 2000 2004 2008 2012 2016 2020

Figure 13: Comparing EFFR Term Rate and Compound Arrears

3-Month Compound in Arrears

3-Month Term Rate

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York; Refinitiv; Federal Reserve Board staff calculations

27

The key difference between the two rates is that the term rate reflects market expectations as to what

will happen to interest rates, while the compound average used in OIS contracts will reflect what

actually happens to interest rates over the period. Although market expectations have generally been

close to the actual movement in rates, they have not always matched. As shown below, the basis

between the term rate and compound overnight rates has been material at times, in particular during

times when rates have fallen rapidly.

The amount of this basis will depend on the tenor of the term rate. As discussed above, the basis

between an in advance and in arrears rate will increase with the length of the interest period. As rates

are less predictable over longer periods of time, a longer-tenor term rate will be less able to match the

actual movement in rates over the period. As shown below, a 6-month EFFR OIS rate has historically

had close to the same basis to in arrears as a 30-day average of the EFFR set in advance.

-150

-100

-50

0

50

100

1988 1992 1996 2000 2004 2008 2012 2016 2020

Figure 14: Basis between 3-Month Compound EFFR in Arrears

and a 3-Month EFFR OIS Term Rate

EFFR 3m arrears - EFFR 3m term rate

Basis Points

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York; Refinitiv; Federal Reserve Board staff calculations

-200

-150

-100

-50

0

50

100

150

200

1988 1992 1996 2000 2004 2008 2012 2016 2020

Figure 15: Bases between a 6-Month Term Rate and an in Advance Rate

Relative to 6-Month Arrears

EFFR 6m arrears - EFFR 6m term rate

EFFR 6m arrears - EFFR 1m advance

Basis Points

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York; Refinitiv; Federal Reserve Board staff calculations

28

The basis involved imply that a forward-looking term rate would not generally be effectively hedged

by a standard OIS contract. As discussed above, for in arrears and also in advance structures, which

can be viewed as in arrears with a payment delay, hedging would be easier to achieve.

Of course, potential users of a forward-looking term rate may not wish to hedge their exposures,

especially if they understand that hedging is easier with structures based directly on SOFR, but for

those who might seek to hedge a term-rate exposure, it may be helpful to understand how forward-

looking-term rate exposures can (and in an economic sense, will) be dynamically hedged by using

SOFR OIS. To see this, consider an example of an end user that wants to hedge a set of quarterly

term SOFR payments they are required to make over the next year by converting their floating term

rate payments into fixed rate. Although they are paying the quarterly term rate, they could still hedge

this directly in the SOFR OIS market with the following steps:

16

• Step 1: Enter into a 12-month SOFR OIS contract at the start of the year to pay the fixed-leg

rate

(

)

and receive quarterly compound SOFR payments.

• Step 2: At the start of each quarter, enter into a 3-month SOFR OIS contract to receive the

fixed-leg term rate,

and pay compound SOFR over that quarter. Use the quarterly

floating-rate SOFR payment from the 12-month OIS in Step 1 to pay the floating-rate leg of

Step 2 and use the fixed rate payment of this swap to pay the quarterly term-rate owed.

In practice, many firms would engage a bank or a dealer to do these steps for them rather than taking

it on themselves, and there would be some transaction cost to doing this. If they entered into a

bespoke term rate swap with their dealer instead, then the dealer would need to enter the SOFR OIS

market to hedge the swap and that would involve the same basic steps and costs. In addition, there

may be some charges for any basis risk (the term rate benchmark may not precisely match the OIS

rate that the dealer may be able to obtain on any given day), and there may be associated costs if the

bespoke swap cannot be cleared or if the dealer needs to warehouse the swap and must charge for the

associated risk. There may also be additional costs associated with hedging based on a SOFR term

rate derivative given that, in contrast to SOFR itself, any potential SOFR term-rate benchmark is not

included in the Financial Accounting Standards Board’s (FASB’s) hedge accounting list. Each of these

factors would result in additional transactions costs to the parties to the transaction.

Dealers are equipped to provide these kinds of services to their clients, and presumably they will, but

they will also need to pass on the associated costs. On the other hand, many of these costs could be

avoided from the start if the borrower used SOFR rather than a forward-looking term-rate. An

instrument that required payments of compounded SOFR could be directly hedged in the SOFR OIS

market, with far fewer steps and costs. Which leads to the final important point of this Guide – use of

the forward-looking term rate will tend to involve more transactions costs than using SOFR, and if end users know that

they want to hedge their floating rate payments then it would involve fewer transaction costs if they can modify their

systems to be able to pay or receive the compound average SOFR rather than paying or receiving the forward-looking

term rate.

None of this is meant to contradict the idea that the forward-looking term rate can be a useful tool

for some market participants, but it is also important that they understand the likely costs as well. A

16

This example uses an OIS convention in which floating and fixed rate payments are paid quarterly.

29

number of firms will likely wish to avoid these costs and use SOFR from the start. Many other firms

will likely come to the same conclusion over time as they gain experience with the new market structure

and are able to update their systems to accommodate using SOFR.

30

Appendix 1: Calculating Compound Interest

For some, it may be useful to note the mathematical formulas behind compound and simple interest

conventions. The table below demonstrates the basic distinction between the two concepts: with

simple interest, interest is charged based only on the principal outstanding, while with compound

interest, interest is charged based both on outstanding principal and accumulated unpaid interest.

Secured Overnight

Financing Rate

(Percent, Annualized)

Number of

Days Rate is

Applied

Effective Rate

(Not Annualized)

Principle

Principal +

Accumulated

Interest

Interest Charge for Next Business

Day

(Effective Rate*

Principal

)

Monday, Jan 7, 2019

2.41

1

0.0241/360 = 0.006694%

$1,000,000.00

$1,000,000.00 $66.94

Tuesday, Jan 8, 2019

2.42

1 0.0242/360 = 0.006722%

$1,000,000.00 $1,000,066.94

$67.22

Wednesday, Jan 9, 2019

2.45

1

0.0245/360 = 0.006806%

$1,000,000.00

$1,000,134.16

$68.06

Thursday, Jan 10, 2019 2.43

1

0.0243/360 = 0.006750% $1,000,000.00

$1,000,202.22

$67.50

Friday, Jan 11, 2019

2.41

3

3*0.0241/360 = 0.020083%

$1,000,000.00

$1,000,269.72

$200.83

Monday, Jan 14, 2019 ---

---

---

$1,000,000.00

$1,000,470.55

Payment Due

Monday, Jan 14, 2019

$1,000,470.56

Annualized Simple Rate of Interest:

= (360/7)*(.047056%) = 2.4200%

Secured Overnight

Financing Rate

(Percent, Annualized)

Number of

Days Rate is

Applied

Effective Rate

(Not Annualized)

Principle

Principal +

Accumulated

Interest

Interest Charge for Next Business

Day

(Effective Rate*(Principal+Accumulated

Interest))

Monday, Jan 7, 2019 2.41

1 0.0241/360 = 0.006694%

$1,000,000.00 $1,000,000.00

$66.94

Tuesday, Jan 8, 2019 2.42

1

0.0242/360 = 0.006722% $1,000,000.00

$1,000,066.94 $67.23

Wednesday, Jan 9, 2019 2.45 1

0.0245/360 = 0.006806% $1,000,000.00 $1,000,134.17

$68.06

Thursday, Jan 10, 2019

2.43 1 0.0243/360 = 0.006750%

$1,000,000.00 $1,000,202.23

$67.51

Friday, Jan 11, 2019 2.41

3 3*0.0241/360 = 0.020083% $1,000,000.00

$1,000,269.74 $200.89

Monday, Jan 14, 2019 ---

--- --- $1,000,000.00

$1,000,470.63

Payment Due

Monday, Jan 14, 2019

$1,000,470.63

Annualized Compound Rate of Interest:

= (360/7)*(.047064%) = 2.4204%

Compound Interest on a One-Week SOFR Loan of $1 Million Drawn on Jan 7, 2019