An eye on reform:

Examining decisions, procedures, and outcomes of the

Oregon Board of Parole and Post-Prison Supervision release process

Christopher M. Campbell, Ph.D.

*

Associate Professor of Criminology and Criminal Justice

Portland State University

Mieke de Vrind, J.D.

Staff Attorney, Criminal Justice Reform Clinic

Lewis & Clark Law School

Aliza B. Kaplan, J.D.

†

Professor of Law

Lewis & Clark Law School

Caroline Taylor

Lewis & Clark Law School (Class of 2022)

Project Period: 11/30/2020 – 08/31/2022

This study was funded by Arnold Ventures. The findings and opinions reported here are those of

the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Arnold Ventures, Lewis & Clark Law

School, or Portland State University.

*

Christopher M. Campbell, Ph.D. Associate Professor in the Department of Criminology & Criminal Justice, College

of Urban and Public Affairs at Portland State University, Office: 503 725-9896, Email: cca[email protected]. All

questions regarding findings and analyses should be directed to Dr. Campbell.

†

Aliza B. Kaplan, J.D., Professor and Director, Criminal Justice Reform Clinic, Lewis & Clark Law School, 10101

S. Terwilliger Blvd. Portland, Oregon 97219, Phone: 503-768-6721, Email: akaplan@lclark.edu.

ii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project would not be possible without the support provided by multiple people and agencies.

Recognizing this, the authors would like to thank the current Oregon Board of Parole and Post-

Prison Supervision and the Oregon Department of Corrections and each of these agencies’ staff

members for their help with this project. We give special thanks to our staff contacts of Snake

River Correctional Institution (SRCI), Oregon State Penitentiary (OSP), Two Rivers Correctional

Institution (TRCI), Eastern Oregon Correctional Institution (EOCI), and Oregon State Correctional

Institution (OSCI). They ensured that the lockboxes used to collect the surveys were in a place

where participants could access them. At times this meant they needed to shuffle the 35lb and 96lb

boxes to multiple units. Without their help, the survey collection would not have been possible.

Over the course of this project, we met with officials from both of these agencies to discuss issues

of concern, data requests, and current practices and policy. We continue to appreciate their help,

and recognize that without their collaboration, much of this project would be an incomplete picture

of the system.

We would also like to thank Breanna Browning and Michelle Love for their help with

gathering data and interviews. A special thanks also goes to Molly Christmann for helping in the

survey administration and data input.

Finally, we give thanks to all of those who participated in our survey and interviews. The insight

gained from all of these conversations proved critical in capturing the scope of Oregon’s parole

process and areas ripe for reform.

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................ 1

I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 10

II. THE HISTORY OF PAROLE IN OREGON ............................................................................................ 10

1905-1939 ........................................................................................................................................... 10

1939-1969 ........................................................................................................................................... 12

1969-1989 ........................................................................................................................................... 13

1989-Present ....................................................................................................................................... 14

III. STAKEHOLDERS AND THE PAROLE PROCESS .................................................................................. 16

The Parole Board .................................................................................................................................... 16

Victims and Interested Parties................................................................................................................. 17

Attorneys ................................................................................................................................................. 18

Defense Attorneys ............................................................................................................................... 18

Prosecutors .......................................................................................................................................... 18

Victims’ Rights Attorneys .................................................................................................................. 19

Prisoners, Petitioners, Parolees ............................................................................................................... 19

Types of Hearings ................................................................................................................................... 20

Murder Review ................................................................................................................................... 21

Prison Term ......................................................................................................................................... 22

Exit Interview ...................................................................................................................................... 23

Parole Consideration ........................................................................................................................... 24

Personal Review and Personal Interview ............................................................................................ 24

Juvenile Parole Hearing ...................................................................................................................... 25

Medical Release .................................................................................................................................. 25

Process for Petitioner .............................................................................................................................. 26

The Hearing ............................................................................................................................................ 27

Decisions ................................................................................................................................................. 28

IV. WHERE PAROLE FITS IN THE MODERN LEGAL SYSTEM ................................................................ 29

Legal Issues in Parole ............................................................................................................................. 29

Due Process ......................................................................................................................................... 29

Evidentiary Issues ............................................................................................................................... 29

Exhibit O: administrative appeals and seeking judicial review .............................................................. 30

V. OVERVIEW: EMPIRICAL EXAMINATION OF PAROLE PROCESSES ................................................... 33

Quantitative Data .................................................................................................................................... 33

Table 1. Initial truncated sample release reason/status for Recidivism Dataset. ................................ 34

Figure 1. Survey lock-box at OSP ...................................................................................................... 35

Table 2. Sampling plan for the AIC survey. ....................................................................................... 36

Qualitative Data ...................................................................................................................................... 36

VI. GOAL 1 FINDINGS: IDENTIFYING PATTERNS IN RELEASE DECISIONS ............................................ 38

Patterns via Quantitative Analyses ......................................................................................................... 38

Figure 2. Count of eligible convictions, parolee releases, and deaths in custody over time ............... 39

Table 3. Descriptives of life with the possibility of parole CJRC data ............................................... 40

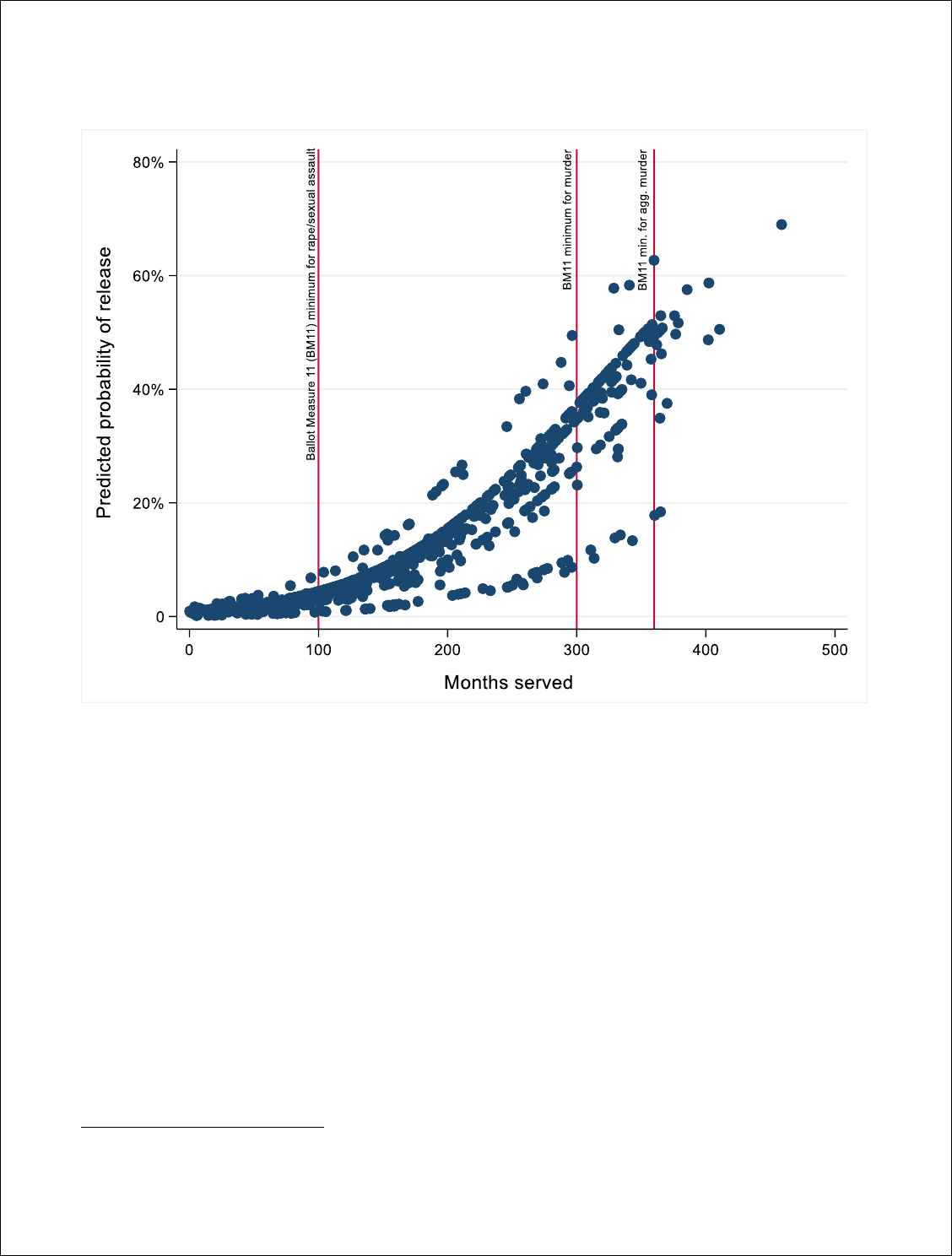

Figure 3. Baseline predicted probability of release by months served ................................................ 42

Table 4. Comparison of relative predictive accuracy of months to simulated parole date ................. 43

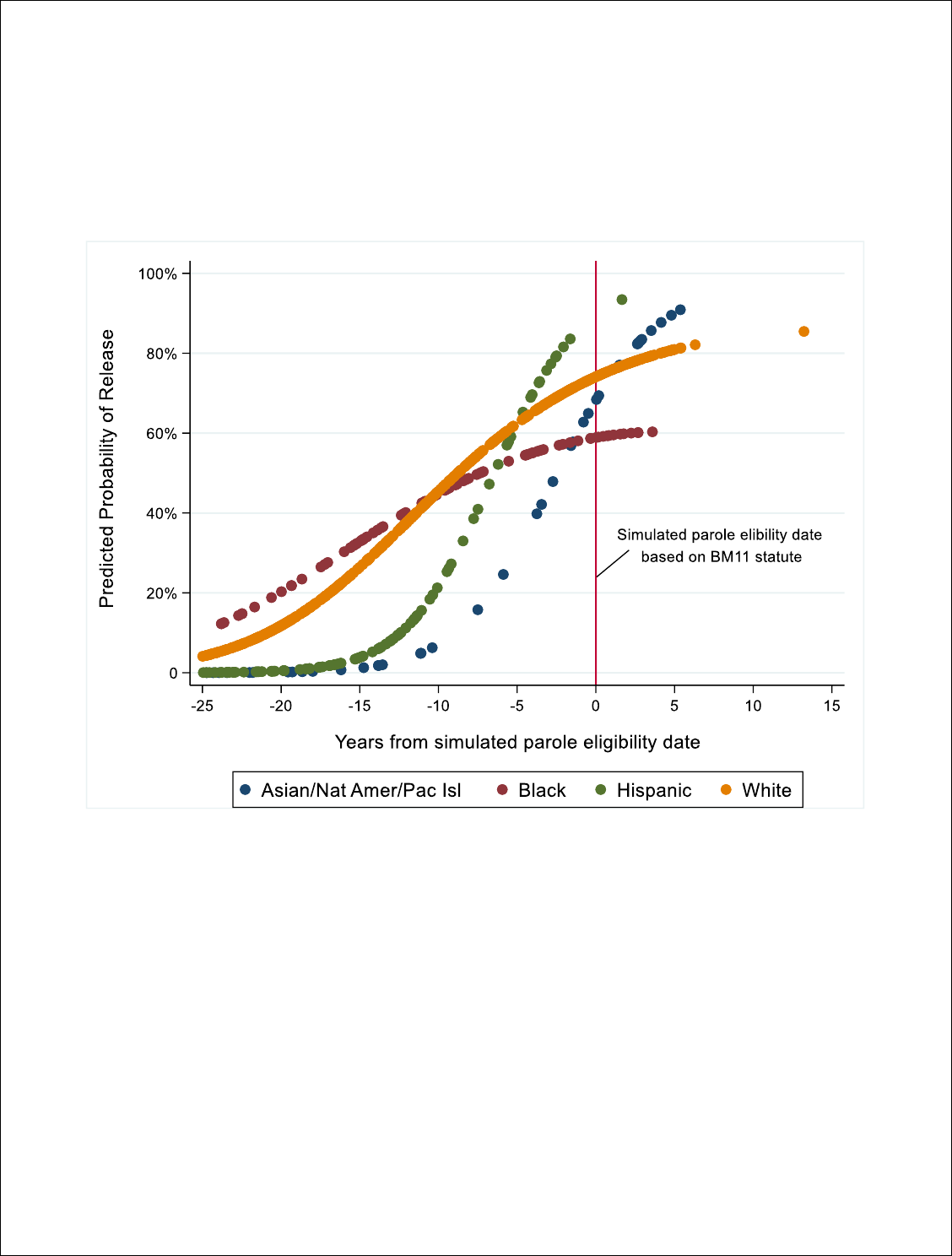

Figure 4. Baseline predicted probability of release by race/ethnicity ................................................. 44

Qualitative Analyses of the Board’s process, decision-making, and influences ..................................... 45

Goal 1 Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 56

ii

VII. GOAL 2 FINDINGS: DIFFERENCES ACROSS CASES BEFORE THE BOARD ........................................ 59

Figure 5. Perceptions of the Board among eligible AICs ................................................................... 60

Figure 6. Perceptions of the Board’s decision-making and process among eligible AICs ................. 61

Goal 2 Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 62

VIII. GOAL 3 FINDINGS: HOW THE BOARD’S HEARING PROCESS IMPACT ELIGIBLE PARTIES............ 64

Figure 7. Perceptions decision-making and process among those with hearing experience ............... 65

Goal 3 Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 69

IX. GOAL 4 FINDINGS: PAROLEE PERFORMANCE IN THE COMMUNITY ............................................... 69

Figure 8. Percent of release type (PPS or parole) that failed supervision by recidivism type ............ 73

Table 5. Model Balance Summary ...................................................................................................... 75

Figure 9. Marginal probability of recidivism of PPS versus paroled in matched sample ................... 77

Goal 4 Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 80

X. AREAS FOR REFORM AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS................................................................. 82

More resources for the Parole Board ...................................................................................................... 82

Improve data collection and rely on empirical evidence to help decision-making ................................. 84

Codify and reify abstract expectations of the Board ............................................................................... 85

Representation for hearings should be an opt-out procedure .................................................................. 87

Standardize the approach to parolee supervision across the counties ..................................................... 88

Provide more specific transparency for AICs and victims...................................................................... 88

1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In an effort to empirically explore and identify potential areas of reform that might exist in

the Oregon Board of Parole and Post-Prison Supervision (the Board) release process hearings and

decision-making process, the Criminal Justice Reform Clinic at Lewis & Clark Law School

(CJRC) launched a project funded by Arnold Ventures in November of 2020. This project aimed

to understand how incarcerated potential parolees (petitioners) and parolees in the community are

impacted by the Board’s process using a large-scale mixed method (qualitative and quantitative)

research study. Moreover, the purpose of the study is also to examine how the Board’s decisions

and processes may be related to certain outcomes (e.g., initial release and supervision failure).

Where possible, special attention is given to differences in race/ethnicity of the parolee and

subsequent outcomes of decisions and supervisions.

The key research goals of this study were to (1) determine if there are any patterns in Board

decisions to release an eligible person to parole supervision, (2) determine if there are any

differences across cases brought before the Board, (3) identify how the hearing and decision-

making process impact eligible parties/parolees, and (4) examine the degree to which release

decisions are accurate in determining a parolee’s likelihood to reoffend. Below are summaries of

each goal and a brief overview of the takeaway messages from each section.

Please note that the data and findings associated with each goal capture cases released over

the last several years. They encompass laws that have changed as well as many Board member

cohorts that have long since turned over during the analyzed timeframe. For this report, the Board

is examined and discussed as a living institution, the scope of which can be impacted depending

on who serves on it. Thus, none of the conclusions provided here are directed at any one cohort of

Board members, including the current Board. In fact, limited data were available on decisions

made by the current cohort for this report due to several reasons (e.g., COVID-19 disruptions and

lack of staffing resources). All findings and conclusions are drawn from data and reflections that

incorporate multiple Board cohorts and governor administrations. As a result, all recommendations

made here are focused on reforms to improve the fairness, transparency, and legitimacy of the

Board as an institution while maintaining the mission of public safety. Recommendations are

provided to emphasize the fact that the Board’s processes and policies transcend any single cohort

of Board members and culture, and the codification of data-driven policies is the best way to

safeguard fairness across Board cohorts.

Goal 1 Summary – Patterns in release

Data used for this goal captured 763 life-with-parole cases. The majority of releases were

relatively recent, with most occurring between 2004 and 2016. (see Figure 2). While time-served

and concurrent/consecutive violent convictions are the most important factors in predicting if a

parole-eligible person will be released, race/ethnicity is an added factor that yields some distinct

trends. Race/ethnicity and time-served/months to projected parole-eligibility date were the only

two measures able to predict release with 80% accuracy. It is possible that some of the differences

that arise between race/ethnic groups are products of the case-specifics and hearing information,

both of which still need to be analyzed. This does not mean specific Board cohorts or members

were expressing overt bias. Rather, the trends over time suggest the processes and expectations

which create the foundation of a Board’s decisions, appear to truncate the release probability for

certain racial/ethnic subgroups. More recent data that was descriptively analyzed highlights the

2

potential differences in the most recent Board cohort hearings. Specifically, this analysis shows

that recent efforts may have reduced racial/ethnic differences in the probability of release, but also

highlights how the Board’s process and decision-making is susceptible to member turnover. In

other words, without further codification, the positive steps made by one Board cohort could be

quickly undone by the next turnover.

Interviews highlighted three themes about how the Board decides between release or deny/

“flop” a petitioner: (1) clarity in criteria, (2) fairness and consistency, and (3) socio-political

pressures. Both victims and AICs need greater clarity and transparency about the Board’s decision-

making. This is not only critical for each party to understand a process of the justice system, but it

is also essential to ensure that the process is viewed as legitimate. Weaknesses in transparency can

lead to, and be exacerbated by, weaknesses in fairness and consistency. The fairness of decisions

must be relayed through transparent application of consistent criteria, especially in a prison setting.

Issues in fairness and consistency could be remedied via two efforts: Ensuring that AICs

and the victims

3

have some form of representation, and requiring key trainings for the Board. Legal

representation and/or support partners were highlighted as a critical factor to help people navigate

the process and communicate their thoughts and concerns. Trainings were discussed as a way to

increase fairness/interchangeability across cases and to increase consistency. Trainings should

include common philosophies and approaches used by Boards across the nation, how more

actuarial risk assessments (e.g., LS/CMI) could be integrated into decision-making, and how

rehabilitation (specifically cognitive behavioral therapy) works to change human behavior. Such

trainings are readily available through organizations like the National Institute of Corrections and

the Center for Effective Public Policy. The Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences also provides

updated information on the science behind rehabilitation and associated metrics.

It is important to note that the current Board cohort makes a concerted effort to have more

trainings and to make well-informed, evidence-based decisions. They frequently attend and present

at practitioner and academic conferences (Association of Paroling Agencies International [APAI])

to stay up-to-date with best practices, including on issues related to disparate outcomes among

racial subgroups by connecting with organizations that offer trainings and discussions of best

practices (e.g., Center for Effective Public Policy’s National Parole Resource Center). Another

example is “Trauma Informed Tuesdays” which is a webinar put on by APAI for all members,

where the Board and staff sign in to an informative discussion or presentation about trauma. These

steps are admirable and consistent with a Board focused on best practices. However, the focus of

the Board is dependent on the interests and scope of the Board’s sitting Chair and who is governor

at the time. Codifying this practice and expected trainings into a minimum expectation for all

Board cohorts would safeguard against turnover.

Finally, fairness and consistency were also noted to fluctuate with Board member turnover,

making issues inherently intertwined. Much of that is due to the lack of codified standards that a

potential Board member must meet, as well as the lack of on-boarding and ongoing training for

seated members. Oregon is one of 20 states that do not have statutory requirements for Board

member qualifications. Turnover and member selection, unaided by statutory standards and

training, leaves the Board susceptible to influence by socio-political pressures due to the (1)

3

Some may incorrectly believe that the presence of the district attorney is to be at the hearing on behalf of the victim.

The DA is instead at the hearing to represent the community from which the petitioner was convicted. Victims must

acquire their own representation, legal aid, or advocacy, although some advocacy is provided via the Board.

3

selection process for new members, (2) seated members’ concern over maintaining their position,

and (3) concern over next job opportunities when a member’s term on the Board ends. These could

be addressed by extending Board member terms by two years, installing a more robust selection

process for new members, and not allowing people to run for elected office while serving on the

Board.

Goal 1 Takeaway

Problem

Foundational processes and expectations have shown potential bias toward

release decisions.

Solution

Improve and solidify fairness by requiring transparent communication of decisions

and how criteria are applied for all parties who are subject to hearings.

Problem

Key areas susceptible to turnover include the clarity in criteria used, fairness

and consistency in decisions, and socio-political pressures.

Solution

Safeguard against dramatic change between Board cohorts by requiring a minimum

level of training for all new and seated members, as well as minimum qualification

standards for new members.

Problem

These areas can change dramatically with Board member turnover and

uncertainty among seated members.

Solution

Remove areas of concern that create potential bias in Board decisions by extending

Board member terms by two years, installing a more robust selection process for

new members, and not allowing people to run for elected office while serving on

the Board.

Goal 2 Summary – Differences across cases that come before the Board

This section examined differences between AICs who have and have not experienced

Board hearings. Such an analysis is important to identify policy areas to address and how to target

informational campaigns. A large proportion of AICs, regardless of hearing experience, reported

fearing the Board. Research has demonstrated for decades that fear often stems from a lack of

understanding, increased insecurity, and increased anxiety about a process, all of which are rather

common among AICs. Thus, with a high degree of fear, it is likely more information and resources

need to be available for those who are preparing for the Board. Moreover, fear can be an antithesis

to other factors such as respect and legitimacy, which are closely correlated. Legitimacy is

particularly important because the Board is a body that could greatly motivate AICs and released

parolees to change or seek more help in rehabilitation. A degradation in the legitimacy of the Board

could result in a similar degradation in willingness to follow rehabilitative suggestions and

recommendations made by the Board. To combat this, similar to Goal 1, greater clarity and

transparency may go a long way to bolstering the legitimacy of the Board.

It is important to recognize that those who have not experienced the Board often live

vicariously through those who have hearing experience. This means that if those who have gone

before the Board (especially those who are ultimately released) do not understand the process,

what the Board is looking for, and are unclear about how the Board reached its decision, then that

delegitimization will filter out to those who have not experienced the Board. To help alleviate such

issues among those who are hearing-experienced, policy makers and the Board should consider

4

including clear directional steps in documentation like the Board Action Forms (BAF). BAFs

currently include an explanation of the decision, similar to a court opinion, in the Discussion

section. While important to include, it does not provide much of a response to what the individual

explained in the hearing or what new information was incorporated. The Discussion section will

typically focus on the index crime and related behaviors in spite of the importance given to

“articulating the rehabilitative experience” or demonstrating remorse. This is not to say that the

goal is to ensure that the AIC is happy or particularly satisfied with the ruling. The important thing,

as noted by countless studies on procedural justice and legitimacy, is that the individual felt as

though they had a voice in a fair proceeding, and felt heard. Additionally, the BAF ends with a

finding/decision, with little guidance on what steps the AIC should explore to improve their

chances in the next hearing.

To lessen the influence hearing-experienced AICs have over those without hearing

experience, an effort could be made to help provide all petitioners with what they need, and answer

their questions in preparation for upcoming or past hearings. Several study participants provided

their written correspondence with a Board where members answered the individual’s questions

about how decisions are made or parts of the process. Such correspondence is a great example of

how the Board can bolster legitimacy and fairness in preparation for the hearing. AICs without

hearing experience could benefit from similar correspondence and preparation. Notices with

concise and clear information about the process, things that will be considered, and how best to

prepare could be sent to AICs on a recurring basis after the start of their parole eligibility.

Additional guidance on how to correspond with a Board and find representation for their hearing

would be helpful for all people as they approach their hearing date.

The current Board began a new practice in 2019 to attempt to address this shortcoming.

The Board provides suggestions to the petitioners about how they can improve for their next

hearing, such as writing their thoughts on remorse or programs in which to participate. Prior to

2019 it was up to the AIC to file for “Administrative Review,” which is a process of appeal, to

learn about the ultimate decisions. The 2019 practice of providing reasons has reportedly cut down

on the number of Administrative Reviews. While this is an important and positive practice, it

should be enshrined in policy to ensure that future Board cohorts follow suit.

Goal 2 Takeaway

Problem

Many AIC survey participants reported fearing the Board, which has been

shown to stem from poor understanding, increased insecurity, and increased

anxiety about a process. This can degrade the legitimacy and power of the

Board over behavior and facilitating change.

Solution

Require greater clarity and transparency through information campaigns regarding

hearings and decisions, as well as improve correspondence with petitioners outside

of the hearings, all to bolster legitimacy of the Board.

Problem

Petitioners who perceive the Board and its process as unfair weaken the

Board’s legitimacy, which then spreads to AICs without hearing experience.

Solution

Require that all petitioners receive regular, recurring notices with concise and clear

information about the process, areas considered by the Board, and how best to

prepare basis after the start of their parole eligibility.

5

Goal 3 Summary – Process impact eligible parties/parolees

This section examined only the perceptions reported by AICs with hearing experience. One

of the major findings from this goal is the need for more resources for the AICs and victims. The

provision of more resources is often a difficult recommendation for justice agencies to absorb. No

criminal justice agency has ever indicated that it had too many resources. Thus, when AICs report

that they lack the resources to be successful at parole hearings, this information likely falls on

unsympathetic ears. However, resources available for AICs often, if not always, run in tandem

with the resources needed by justice agencies. A remedy for each of the responses is a strong

informational/education campaign to inform all AICs of the appropriate statutes, how to prepare

for hearings, how to contact the Board, and how to secure rehabilitative programming. Information

campaigns spearheaded by the Board will require more resources for the Board in terms of

personnel and greater digitization of records.

Greater resources are clearly needed for the DOC as well. A dearth of rehabilitative

opportunities sets AICs up to fail when brought before the Board and infringes on the ability of

AICs to rehabilitate. Assuming the mission of the Board, and the DOC as a whole, is to reform

offenders rather than warehouse them, there must be a legislative effort to give these entities the

necessary resources. Such efforts would be a substantial step towards ensuring public safety.

Within this push for more resources is the reiterated need to improve the resources available to

AICs and victims. Specifically, AICs and victims need better resources related to ensuring

representation, pre-hearing information about the process and criteria, and ultimately more clearly

justified decisions and next steps. All of these elements would help to improve the overall

perception that hearing outcomes are forgone conclusions, while still providing ample voice to all

parties involved.

Goal 3 Takeaway

Problem

AICs report that they lack the resources to be successful at parole hearings

Solution

A remedy for each of the responses is a strong informational/education campaign

to inform all AICs of the appropriate statutes, how to prepare for hearings, how to

contact the Board, and how to secure rehabilitative programming. Information

campaigns spearheaded by the Board will require more resources for the Board in

terms of personnel and greater digitization of records.

Problem

Rehabilitation programs often required by the Board are not readily available

for petitioners.

Solution

Greater resources are needed for the DOC to ensure that the appropriate programs

expected by the Board are actually attainable. At a minimum this includes

incorporating the most efficacious domestic violence programs and sex offender

programs.

Problem

AICs and victims lack needed resources related to ensuring representation,

pre-hearing information about the process and criteria, and ultimately more

clearly justified decisions.

Solution

In addition to making a codified information campaign standard protocol, there

ought to be an “opt out” procedure for representation, making it required unless

otherwise stated by the petitioner or victim.

6

Goal 4 Summary – Identifying parolee needs in their likelihood to reoffend

Goal 4 examines how well paroling processes can predict recidivism and identify other

factors that might impact parolee performance in the community. An appropriate comparison

group was identified using the available Recidivism Dataset (described in the Overview and Goal

4 section). Using a more compatible comparison group, the analysis demonstrates that traditional

comparisons to recidivism rates among the post-prison supervision (PPS) population are naïve

estimates. Naïve estimates of parole success suggest that parolees are more likely to succeed

compared to the general PPS population. However, when an appropriate comparison group is

applied, the analysis shows that parolees struggle more than the PPS population. Specifically,

parolees have significantly more violations than those on PPS. Matched-group analyses also

suggest that given an otherwise average case, parolees have a substantively higher probability of

failure for every recidivism event except for reconvictions. This essentially means that if we were

to take two similar cases, one paroled and one released via determinate sentencing, those on parole

have a higher probability of failure following release.

These differences highlight a low risk population that is of the highest need in terms of

services. Perhaps the most obvious difference that parolees experience is that of age and the

difficulties in adjusting to a dramatically changed society than when the individual went into

custody over 20 years ago. Reintegration into a new world of technology after the loss of social

ties over the years was a major concern for several AICs and parolees alike. This can manifest in

parolees having a difficult time following the conditions of their community supervision following

decades in prison, demonstrating that the parolee population likely needs greater resources to

improve their reintegration chances. Another reason for the differences could be that parole

officers apply an exceptionally high degree of supervision and monitoring on those released via

parole. Known in the discipline as “supervision effects,” such a practice demonstrates how

parolees might experience greater scrutiny in the community than those on PPS. The degree of

scrutiny, however, can depend on the county to which the individual is released. One major way

that the Board can integrate decisions and foster standardization across county supervision

providers is to incorporate a discussion of criminogenic needs when considering an individual’s

potential success upon release or in exit interviews. Similarly, the Board can help to foster great

standardization and improve connectivity to release/supervision plans by incorporating the

LS/CMI into their decision-making and condition-setting protocol.

Goal 4 Takeaway

Problem

Paroled populations have the highest need for services, but it is overlooked by

erroneous comparisons to the general population on post-prison supervision.

Solution

Reporting of parolee recidivism should be completed via a matched-comparison

study, where parolees are compared to like cases and not the general PPS

population.

Problem

Community corrections supervision is far too idiosyncratic when it comes to

supervising parolees.

Solution

The Board should incorporate criminogenic needs and the LS/CMI when

considering potential success upon release and condition-setting protocol.

7

Abbreviated Recommendations

A number of recommendations have been derived from the data and analyses gathered for

this project. Readers are referred to the section on recommendations to provide greater detail for

each of the recommendations provided here as well as for the supporting evidence for each. These

areas of improvement fall into six key areas:

4

(1) More resources for the Board, (2) Improve data

collection and rely on empirical evidence to help decision-making, (3) Codify and reify abstract

expectations of the Board, (4) Representation for hearings should be an opt-out procedure, (5)

Standardize the approach to parolee supervision across the counties, and (6) Provide more specific

transparency for AICs and victims.

More resources for the Parole Board

The following are specific areas of recommended investment by the state:

1. Implement a parole-specific data management system/protocol that is directly integrated

into the DOC-400. Given the inherent dependence that exists between the Board and the

DOC operations, particularly when it comes to release plans and disciplinary reports, there

should be a much clearer, transparent, and direct process by which the Board and DOC can

share data points.

2. Conduct a workload study for the Board. More data points ought to be collected on the

Board’s work and caseload (e.g., how much time is spent on which tasks?).

3. Track “what works” when knowing what to look for in rehabilitation and reentry. Such

data needs to be tracked to provide more consistent information for the Board on a given

AIC coming before the Board.

4. Expedited and sustained digitization of data and files for the Board. The Board is woefully

behind when it comes to data digitization, as was indicated the Board’s current staff and

by past and present members. Temporary workers and supportive infrastructure could be

hired to help scan and digitize all paper-based information which would immensely aid the

digitization process.

5. Additional supporting personnel for the Board would aid in achieving additional

transparency and fairness. These positions could include the following:

a. An additional data management analyst to help provide more written context to the

Board’s reports, which are not immediately digestible by the public.

b. It is highly recommended that there is someone on the Board’s staff who can field and

respond to CorrLinks (email) and written correspondence from AICs to the Board.

c. Personnel related to the Board should be tasked with and specialized in aiding with

release plans – specifically working with release counselors and the county community

corrections staff.

d. A Board staff person should be tasked with briefing (prior to hearings) and de-briefing

(after hearings) AICs and victims involved in the hearings.

6. Consistent and ongoing training should be codified and required for all Board members.

Such training should include, but is not limited to, mandatory onboarding for all new

members and continuing education for seated members to take every three years.

4

These recommendations are provided numerically for the sake of ease in grouping and ease for reading. The list is

not provided in any particular order, and are not meant to be taken as a prioritized list.

8

7. All parties (Board members, AICs, and victims) should have adequate access to

trauma/grief counseling. The cases that come before the Board are inherently traumatic for

everyone involved.

Improve data collection and rely on empirical evidence to help decision-making

The following list of reform recommendations highlights how and why certain data and empirical

evidence should be better integrated into the Board's processes.

8. More targeted rehabilitative programming must be offered by the DOC, and it should be

offered in a capacity and frequency that will satisfy the needs of the petitioner population

and the Board’s decision-making. This is especially critical for those programs the Board

often expects to see participation in, such as more domestic violence and sex offender

programming.

9. Information needs to be collected on how the 10 factors are considered in each murder

review, and how the three core factors weighed into the decisions related to the Exit

Interviews specifically.

10. The DOC and the Board need to engage in clearer and more useful tracking of rehabilitation

information.

11. Use more actuarial risk information (e.g., LS/CMI and information about needs) and

sociological information about social network/situation to supplement psychological

evaluations. Currently, the Board relies on the Static-99 and one other dynamic tool for sex

offenses, and the HCR-20 primarily for psychological evaluations and Exit interviews, but

this should be expanded to include the LS/CMI (used in all counties to guide supervision

and rehabilitation planning). Specifically, the LS/CMI should be used to help guide the

process of setting conditions.

Codify and reify abstract expectations of the Board

The following recommendations are focused on ways to improve abstract definitions in order to

address interpretations and expectations that can change from Board to Board.

12. Define the purpose of punishment in Oregon. Regardless of the state, when it comes to

criminal prosecution and punishment, there will always be a constant need to balance the

goals of punishment – retribution, rehabilitation, incapacitation, and deterrence. However,

without a clear definition as to which goal is a priority in Oregon, the application of

punishment will forever be idiosyncratic. Doing this will help restore perceptions of

fairness, justice, legitimacy, and trust into the state, the corrections system, and the justice

system as a whole.

13. Clearly define the explicit relationship between rehabilitation, supervision success, and the

purpose of parole. Such definitions could minimize differences in interpretation between

members and cohorts. This is important because differences in such interpretations degrade

legitimacy and fairness in the system and thereby undermine decisions and power of the

Board.

14. Define what it means to have a “fair hearing.” This information can be included in a

briefing of AICs before they go to a hearing, as well as in a de-briefing after a hearing takes

place.

15. Define “demonstrating insight” and what it means to be “rehabilitated.” Defining these two

concepts can help to improve the rehabilitation of AICs as they seek to internalize what

rehabilitation means to them well in advance of the hearing.

9

16. Explicitly define the role and purpose of the DA in hearings. Without Board members who

are willing to interrupt or stop a DA from re-litigating the initial case, then at the very least,

the legitimacy, fairness, and interchangeability of hearing decisions are at risk of being

compromised.

Representation for hearings should be an opt-out procedure

Representation was identified in multiple findings as something that could be dramatically

important for AICs and victims. However, it is not currently set up as something that is easily

accessible. These two recommendations provide options to addressing this shortcoming.

17. Ensure that all parties involved in hearings are provided adequate representation if desired.

This should be in the form of an opt-out process. Parole-eligible AICs going before the

board should have automatic representation selected similar to how public defense counsel

is for indigent clients. Similarly, all victims should be assigned counsel to help them

navigate the parole process.

18. Greater investment should be made into representation. This may take the form of creating

an office of parole representation in the Oregon Office of Public Defense Services who can

help coordinate available counsel.

Standardize the approach to parolee supervision across the counties

19. Noted in multiple findings was the lack of consistency in supervision across county

jurisdictions. There are currently far too many idiosyncratic differences between counties

and their approach to supervision. Moving forward, it is recommended that the state

establish minimum requirements for how supervision should be completed, especially for

special populations. Funds from the Justice Reinvestment Act and gap analyses of services

available in each county can help structure additional protocols and support systems to help

counties achieve this.

Provide more specific transparency for AICs and victims

20. Relay expectations and justification information to AICs in a clear way. Generally, a larger

effort to provide more information can take the form of reform efforts completed by other

states. Similarly, improvements in transparency are important for victims. As noted by

victim advocates’ statements, there needs to be greater transparency in process and

decision-making before and after hearings.

10

I. INTRODUCTION

Following the 1970s “punitive turn” for the United States criminal justice system, many

states removed or restructured how parole boards were utilized. Several states opted to institute a

determinant sentencing system with semi-structured guidelines, removing most Board

discretionary power. Since the Board’s restructuring, states like Oregon added various

complexities to hearings and decision-making processes, creating a labyrinth of layered laws and

varying viewpoints of rotating members. Today, the Oregon Board of Parole and Post-Prison

Supervision (the Board) oversees the discretionary release of approximately 1,300 adults in

custody (AICs), none of whom have a guaranteed right to counsel to help navigate hearing

complexities.

In an effort to empirically explore and identify problem areas that might exist in the Board’s

hearings and decision-making process, the Criminal Justice Reform Clinic at Lewis & Clark Law

School (CJRC) launched a project funded by Arnold Ventures. This project aimed to understand

how incarcerated potential parolees and parolees in the community

5

are impacted by the process

using a large-scale mixed method (qualitative and quantitative) research study. Moreover, the

purpose of the study is also to examine how decisions and processes may be related to certain

outcomes (e.g., initial release and supervision failure). Special attention is given to differences in

race/ethnicity of the parolee and subsequent outcomes of decisions and supervisions.

The key research goals of this study are to (1) determine if there are any patterns in the

Board’s decision to release an eligible person to parole supervision, (2) determine if there are any

differences across cases brought before the Board, (3) identify how the hearing and decision-

making process impact eligible parties/parolees, and (4) examine the degree to which release

decisions are accurate in determining a parolee’s likelihood to reoffend.

II. THE HISTORY OF PAROLE IN OREGON

1905-1939

In 1905, the 23rd Oregon Legislative Assembly enacted two laws which created the

modern parole system. One of the bills signed into law, S.B. 233, provided for indeterminate

6

sentencing of people convicted of certain felonies and granted authority to the Governor

7

to parole

5

Broadly termed “parolees” to encompass all those eligible for a parole hearing at some point or have experienced a

hearing and have been released.

6

Understanding the difference between determinate and indeterminate sentencing is essential to understanding the

nature of parole. Determinate sentences have a defined period of time that the convicted person serves in custody, so

when that person receives their sentence, they know from the outset the amount of time they will remain incarcerated.

Determinate sentences cannot be altered by a parole board or other agency. Indeterminate sentences, however, provide

a range of time for a person to serve in prison (“5 to 10 years”). Indeterminate sentences set minimum terms of

incarceration for an individual to serve and allow that person’s release date to be determined by a body like a parole

board.

7

The indeterminate sentencing bill was a recommendation from the Governor at the time, George E. Chamberlain,

who said “there are in every prison many convicts suffering long sentences…who, if an opportunity were given them,

would endeavor to restore themselves to useful citizenship…The Governor should be permitted…to parole prisoners

for good conduct, and where in their opinion reformations appears to be complete.” Governor George E. Chamberlain,

Governor’s Message to the Twenty-third Legislative Assembly (1905).

11

the same people for good behavior after completing the statutory minimum period of confinement.

8

The other bill, S.B. 152, enabled the circuit courts to parole people convicted of violations of

Oregon law and supervise those same people during the parole period.

9

Before the enactment of

these two laws, a person in prison could leave by two means: serving the entirety of their sentence,

or receiving executive clemency from the Governor.

10

In the eyes of Governor George E.

Chamberlain, the goal of this new legislation was twofold: first, to allow petitioners release on

good behavior after serving a minimum period of confinement, and second, to provide an executive

check on the uneven administration of justice.

11

To administer the new parole system, the State Parole Board was established in 1911.

12

The Board consisted of three members: two appointed by the Governor, and the third held by the

superintendent of the Oregon State Penitentiary.

13

The Board reviewed all cases resulting in

indeterminate sentences, provided parole recommendations

14

to the Governor, and maintained

contact with persons released on parole.

15

Briefly, the Board expanded to a five person

membership; in addition to the superintendent of the Oregon State Penitentiary and the two

members appointed by the Governor, additional members included the secretary to the Governor

and the parole officer from the brand new office of parole.

16

The parole officer enforced the

conditions of parole and returned those who violated the conditions.

17

After two years of the five-

person Board, its membership returned to three members in 1917, the same year the Oregon

Legislative Assembly abolished minimum sentences for felonies other than murder and treason.

18

From 1911 to 1931, the Board, in its various formations, conducted reviews and offered

recommendations on the disposition of various prisoners. The Board received letters from judges,

spouses, sheriffs, and district attorneys. The Board also frequently interviewed petitioners. The

Board created reports including the petitioner’s name, crime, county, sentence, when received into

custody, minimum sentence, age, and any other crimes and prior board actions.

19

If a petitioner’s

8

1905 Or. Laws 318.

9

1905 Or. Laws 306.

10

The Governor’s clemency power derives from art. V § 14 of the Oregon Constitution which provides the power to

“grant reprieves, commutations, and pardons, after conviction, for all offences (sic) except treason…” OR. CONST. art.

V, § 14.

11

In his 1907 address to the Legislative Assembly, Governor Chamberlain remarked on the variations in sentencing

across the judicial districts of Oregon by concluding that “the administration of justice is uneven…It seems to me that

it is part of the duty of the executive branch of the government to equalize, where conditions warrant, this apparent

inequality in the administration of justice.” Governor George E. Chamberlain, Governor’s Message to the Twenty-

fourth Legislative Assembly (1907). The theme of rectifying the “uneven administration of justice” through parole

policy reforms spans the entirety of the parole system in Oregon; through the implementation of prison term hearings,

this search for equity often leads to longer periods of incarceration and more punitive sentencing schemes.

12

ARCHIVES DIV., OFFICE OF THE SEC’Y OF STATE, STATE OF OREGON, BD. OF PAROLE AND POST-PRISON SUP. ADMIN.

OVERVIEW (2006) [hereinafter BOPPPS ADMIN. OVERVIEW].

13

Id.

14

This process of investigation and providing reports and recommendations to the governor is more akin to the work

of a task force compared to the Board’s work today: conducting hearings and acting as the decision-maker for whether

a petitioner may serve the remainder of their sentence in the community.

15

Id.

16

Id.

17

Id.

18

Id.

19

For example, Frank Kodat, no. 8391, was convicted of burglary and received into the Oregon State Penitentiary. He

was sentenced to 5 years with no minimum; he had one prior burglary conviction. After coming for review by the

Board on November 13, 1923, December 6, 1923, and January 3, 1924, and then at the request of the Governor, the

12

term of confinement was continued, it was often for a month or up to six- occasionally continued

to the statutory “maximum.” As time went on, Board recommendations became more expansive

in volume and scope, including: a statement from the Warden of the penitentiary as to whether the

petitioner had a history of good conduct, more details from the prosecuting district attorney,

sometimes a letter from the prison physician attesting to the petitioner’s good health. The

recommendation also included a statement from the petitioner (when offered).

For example, Wm. P. Brown stated

If I am granted a parole I will do my best to uphold and live

according to the rules of my parole at the same time helping my

mother financially for she is aging and needs my help. On board ship

at sea I am enabled to save money via allotment thereby I am not

spending all I make as I was while ashore.

20

1939-1969

The State Parole Board and State Probation Commission were together replaced in 1939

with the brand-new State Board of Parole and Probation.

21

Along with its new name, the Board

underwent important changes during the late 1930s and 1940s. Significantly, the Board prepared

case history records for petitioners as a backward glancing view of whether they should be granted

parole or not.

22

The 40th Legislative Assembly granted the Board the authority to establish rules

and regulations about the conditions of parole, and to maintain work camps for parolees.

23

Additional legislation enacted in 1941 extended the responsibility and power of the Board to all

petitioners confined to jail or a penitentiary for six months or more,

24

and in the 1950s the Board’s

responsibilities grew to include supervision of all persons on probation, parole, or conditional

pardon within Oregon.

25

The size of the Board increased in 1959 to five members who served for

a term of five years; no more than two members were allowed to belong to the same political party,

and all incumbent members were terminated from their positions on the Board.

26

From its creation in 1955 until its abolishment in 1965, both the Chairman of the Board

and the Director of the Board sat on the “Corrections Classification Board,” a body designed to

“classify inmates for reducing disciplinary and administrative problems, and supervise the transfer

of petitioners between prisons.”

27

Upon the Corrections Classification Board’s termination and

disbandment in 1965, the Corrections Division was established as part of the state Board of Control

before moving to the Governor’s office and eventually the Department of Human Resources.

28

The Corrections Division provided administrative support to the State Board of Parole and

Probation, a function that continues to this day.

Board recommended Mr. Kodat receive a conditional pardon to Tom Coliucais to gain employment. Frank Kodat, No.

8391, February 1924. Parole Bd. Actions. Dept. of Corr. Or. State Archives.

20

Wm. P. Brown, No. 11590, January 1932. Parole Bd. Actions. Dept. of Corr., Or. State Archives.

21

Id.

22

1939 Or. Laws 515.

23

Id.

24

BOPPPS ADMIN. OVERVIEW, supra note 7.

25

1955 Or. Laws 841.

26

BOPPPS ADMIN. OVERVIEW, supra note 7.

27

Or. Admin. Histories, Or. State Archives 61 (1988) [hereinafter ADMIN. HISTORIES].

28

ADMIN. HISTORIES at 60.

13

1969-1989

In 1969, as part of a major governmental restructuring, the Board became a full-time

endeavor, but was reduced to a three-person membership. The Governor terminated the terms of

all incumbent members and appointed new members to four-year terms each of which required

Senate confirmation.

29

Oregon reformed its criminal code in 1973 based on the Model Penal Code, and in so doing

the law favored a presumption to parole.

30

In 1973, likely due to the enactment of the aggravated

murder statute, the State Public Defender

31

took on the additional responsibility of processing

parole appeals.

32

The adoption of HB 2013 significantly impacted the administration of parole in 1977.

Concerns about prison overcrowding and a lack of uniform sentencing in the 1970s culminated in

HB 2013, which established the Advisory Commission on Prison Terms and Parole Standards.

33

The Commission proposed adopting guidelines to mitigate ad hominin variation in parole release

decisions.

34

The guidelines set forth two meanings of determining a prison term: a “severity rating”

of the commitment offense and a “history/risk assessment” based on an Adult in Custody’s

criminal history.

35

The severity rating and history/risk assessment would intersect on an X-Y axis

(“the matrix”), and the point of intersection set forth a range of time for a person to serve in

prison.

36

The implementation of the matrix reflected “a concern with disparity, lack of due process

protections, and a rejection of rehabilitation as the main criterion for parole release.”

37

While implementation of prison term guidelines was meant to increase uniformity in

sentencing, the result of that uniformity included a boom to Oregon’s prison population. By 1985,

a report authored by the Oregon Prison Overcrowding Project (OPOP) found that Oregon State

Penitentiary operated at 153% of its single-cell capacity and Oregon State Correctional Institute

operated at 206% of single-cell capacity.

38

OPOP understood the booming prison population as an

29

Or. Rev. Stat. 144.015.

30

Or. Rev. Stat. 144.175 provided in 1975 that “unless the board is of the opinion that… release should be deferred

or denied because…” RICHARD KU, U.S. DEP’T OF JUST., NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF JUSTICE, AMERICAN PRISONS AND

JAILS VOLUME IV: SUPPLEMENTAL REPORT – CASE STUDIES OF NEW LEGISLATION GOVERNING SENTENCING AND

RELEASE. 122 (1980).

31

The State Public Defender is the former name of the Criminal Appellate Division of the Office of Public Defense

Services, which also now includes a Juvenile Appellate Division in addition to divisions which manage contracting

for trial-level public defense and administration.

32

ADMIN. HISTORIES at 307.

33

ADMIN. HISTORIES at 107.

34

Id.

35

Adult in Custody is the statutory term for someone incarcerated at a correctional institution in Oregon. Supra note

1 at 1.

36

Id.

37

Id. at 109.

38

OR. PRISON OVERCROWDING PROJECT, PUNISHMENT & RISK MGMT. AS AN OR. SANCTIONING MODEL, EXEC.

SUMMARY (1985) [hereinafter OPOP]. Oregon State Penitentiary (OSP) is Oregon’s oldest prison facility, operating

as “The Territory Jail” beginning in April 1842. The location moved several times before its current siting in Salem

in 1866. OSP is a maximum-security facility with 2,242 bed capacity. OSP houses all 37 AICs sentenced to death and

awaiting execution in the state. Santiam Correctional Institution (SCI) was built in 1946 as a part of the Oregon State

Hospital in Salem, before it was sold to the Fairview Home in 1960 and renamed the Frederic Prigg Cottage. The

Cottage was used in 1977 to alleviate some prison overcrowding, was converted into a release center in the 1980s,

and finally became SCI in 1990. Oregon State Correctional Institute (OSCI), also in Salem, became operational in

14

intersection of two variables: how many people were sentenced to serve time in prison, and for

how long did they stay before release.

39

At the time of OPOP’s report, Oregon’s population was

approximately 2.684 million people (United states Census bureau) and its prison population was

3562. Today Oregon’s population is estimated to be roughly 4.2 million, and its prison population

as of February 1, 2022 is 11,993 people.

40

Crime rates in the United States increased throughout the 1970s, with violent crime rates

rising from 36 victimizations per 1,000 persons age 12 and older in 1973 to 39 victimizations per

1000 persons age 12 and older in 1981.

41

According to a report by the Criminal Justice

Commission in Oregon, violent crime increased by 680% from 1960 to 1979.

42

Rising crime rates

in the 1970s and the continued public perception of increasing crime throughout the 1980s eroded

public confidence in rehabilitative justice models.

43

1989-Present

The loss of public faith in rehabilitation fortified punitive criminal justice reforms in the

1980s and 1990s. In 1989, the Oregon Legislature changed the sentencing structure for criminal

convictions and moved from the indeterminate sentencing scheme to a determinate sentencing

structure outlined in sentencing guidelines. The guidelines were a state-level implementation of

the (then new) federal Felony Sentencing Guidelines and apply to crimes committed on or after

November 1, 1989.

44

Since November 1, 1989, the only people whose sentences fall within the

paroling function of the Board’s jurisdiction are people convicted of murder or aggravated murder

and those sentenced as dangerous offenders.

1959 with capacity for 880 AICs. Eastern Oregon Correctional Facility (EOCI) welcomed its first AICs on June 24,

1985. Prior to that, the facility had been used as a state mental hospital. EOCI has a maximum capacity for 1,682

AICs, split between 596 dormitory-style beds, 897 cells, 99 Disciplinary Segregation Unit beds, and 8 infirmary beds.

Powder River Correctional Facility (PRCF) is a 336-bed transition and reentry facility in Baker City which opened on

November 9, 1989—one week after Oregon’s sentencing scheme switched from indeterminate to determinate.

Columbia River Correctional Institution (CRCI) opened in 1990 in Northeast Portland. CRCI includes a drug and

alcohol treatment program in a separate 50-bed dormitory away from the general population. CRCI has 595 total beds.

Now closed, Oregon acquired Shutter Creek Correctional Institution in 1990. It had capacity for 260 AICs. Snake

River Correctional Institution (SRCI) opened in 1991 with 648 beds. An additional 2,352 beds were constructed for

$175 million, the largest state general funded public works project to date at the time. Two Rivers Correctional

Institution (TRCI) in Umatilla had a phased opening from December 1999 to September 2001. It has capacity for

1,632 AICs. Coffee Creek Correctional Facility (CCCF) opened in October 2001 as a minimum-security facility; a

medium-security facility within the same complex opened in April of 2002. CCCF houses the state’s intake center for

adults in custody and contains 1,684 beds. Warner Creek Correctional Facility (WCCF) opened in September 2005

with 496 beds. Finally, Deer Ridge Correctional Institution (DRCI) is distinguished as Oregon’s newest prison,

opening its minimum-security facility in September 2007 and its medium-security facility in February 2008 in Madras.

The facility has capacity for 1,867 adults in custody. See Oregon Corrections Division website, accessed 2.8.2022

39

Id. at 7.

40

U.S. CENSUS BUREAU, INTERCENSAL ESTIMATES OF THE TOTAL RESIDENT POPULATION OF STATES: 1980 TO 1990

(1996).

41

MICHAEL R. RAND, U.S. DEPT. OF JUSTICE, BUREAU OF JUSTICE STATISTICS, VIOLENT CRIME TRENDS, NCJ-107217

(1987).

42

CRIMINAL JUSTICE COMM’N, LONGITUDINAL STUDY OF THE APPLICATION OF MEASURE 11 AND MANDATORY

MINIMUMS IN OREGON (2011).

43

See REPORT OF THE GOVERNOR’S TASK FORCE ON CORRECTIONS (1976).

44

1989 Or. Laws 1301.

15

During the same period of transition in sentencing schemes, a citizens’ initiative in 1994

(“Measure 11”) established mandatory-minimum sentences for certain felonies.

45

Because

mandatory-minimum sentences disallow judicial discretion for the imposition of criminal penalties

after conviction, the measure shifted sentencing discretion from judges who imposed sentences

upon conviction to prosecutors who could select charges that come with statutorily-mandated

sentences if a criminal defendant is convicted.

46

Proponents of Measure 11 argued that the

mandatory-minimums provided both “predictability of sentences” for crime victims and the

community at large, and “comparable sentences”

47

for convictions of the same offense regardless

of the sentencing judge. Even though the true “death” of parole occurred through the imposition

of the sentencing guidelines, Measure 11 further blunted parole as a release mechanism by 1)

instituting longer

48

minimum periods of confinement for people convicted of murder or aggravated

murder, and 2) excluding people convicted of Measure 11 offenses from using accrued “good

time” to discount the length of their sentences.

49

In 1996, Oregonians voted by a 2-1 margin to amend the State Constitution’s provision on

principles of criminal punishment to be “protection of society, personal responsibility,

accountability for one’s actions and reformation” and repeal the provision that criminal

punishment be based on “reformation, and not of vindictive justice.”

50

The same year, Oregonians

also voted to incorporate into the State Constitution a provision providing for crime victims’

rights.

51

What Measure 11 did for people convicted of certain felonies by requiring them to serve

mandatory-minimum sentences, the sentencing guidelines likewise prescribed presumptive

sentences based on a person’s criminal history and conviction at issue; both schemes replaced a

sentencing ceiling

52

with a sentencing floor.

53

As should be apparent from a comprehensive history of parole administration in Oregon,

the functionality of the criminal legal system, and a parole system specifically, is entirely

incumbent upon who sees themselves as its stakeholders. Today, the primary stakeholders in the

parole system include the Board, crime victims and interested parties, petitioners seeking relief or

release, and attorneys (defense attorneys, prosecutors, and victims’ rights attorneys).

45

OREGON STATE LIBRARY, 1994 Voters’ pamphlet, State of Oregon general election (2000).

46

Mandatory-minimum sentences operate differently than determinate sentences. Determinate sentences imposed

under the new sentencing guidelines assign crime severity ratings based on the class of offense, in addition to

consideration of a defendant’s criminal history; mandatory-minimum sentences are prescribed by statute based on the

specific offense, and do not take into consideration a defendant’s prior criminal history.

47

Id.

48

OREGON STATE LIBRARY, 1994 Voters’ pamphlet, State of Oregon general election (2000).

49

Id.

50

OREGON STATE LIBRARY, 1996 Voters’ pamphlet, State of Oregon general election.

51

See OREGON STATE LIBRARY, 1996 Voters’ pamphlet, State of Oregon general election. The Oregon Supreme Court

later held the amendment invalid, Armatta v. Kitzhaber, 327 Or 250 (1998), because the measure included two or more

amendments which each required votes independent of one another. Art. I, § 42 of the Oregon Constitution provides

the state constitutional foundation for crime victims’ rights. OR. CONST. art. I § 42.

52

Language such as “up to” or “no more than.”

53

Language such as “at least” or “defendant shall serve…”

16

III. STAKEHOLDERS AND THE PAROLE PROCESS

The Parole Board

At least three and no more than five members, one of whom must be a woman, compose

the Parole Board.

54

The Governor appoints members of the Board to serve four-year terms.

55

Membership to the Board is subject to confirmation by the Senate,

56

unless membership falls below

three people at which time the Governor may appoint a member to serve the remainder of the

unexpired term with immediate effect.

57

The Director of the Oregon Department of Corrections

(DOC) is an ex officio nonvoting member of the Board and does not count towards the “at least

three, no more than five, at least one woman” requirement of board membership composition.

58

The Governor selects a board member to serve as chairperson and another as vice chairperson;

each has specific duties and powers to aid in the administration of the Board’s work.

59

The Board

counts amongst its current membership former a former prosecutor, a former banker, and former

parole and probation officer.

Like other state agencies, the Board’s budget is set by the Oregon Legislature on a biennial

basis. The Board’s proposed budget for the 2021-2023 biennium was $10,769,785. The budget

represents a 24% increase from the 2019-2021 budget.

60

The Board publishes three main types of

documents relating to statistics and reports on its website. The Board publishes budgetary

information going back to 2015.

61

The Board also provides its Annual Performance Report going

back to 2014, and its Affirmative Action Plan going back to 2017.

62

54

ORS 144.005(1).

55

ORS 144.005(2)(a).

56

ORS 144.015.

57

ORS 144.005(2)(b).

58

ORS 144.005(5).

59

ORS 144.025.

60

OR. BD. OF PAROLE & POST-PRISON SUP., 2021-23 LEGISLATIVELY ADOPTED BUDGET.

61

This information includes the agency’s requested budget, the Governor’s budget, and the legislatively adopted

budget, in addition to any reduction plans.

62

OR. BD. OF PAROLE & POST-PRISON SUP., STATISTICS AND REPORTS,

https://www.oregon.gov/boppps/Pages/Statistics.aspx (last visited Apr. 30, 2022).

17

Victims and Interested Parties

Victims

63

have a constitutional

64

and statutory

65

right to receive notice in advance of and

be present at parole hearings. Other individuals with a “substantial interest in the case”

66

may also

be entitled to participate. Because most judgments imposing criminal sentences contain boilerplate

language prohibiting contact between a petitioner and victim, parole hearings are often the first-

time petitioners face the victims of their crime(s) since sentencing. Parole hearings are also often

the first opportunity a victim will have to learn about how the petitioner has used their time in

prison. Victims receive copies of documents submitted for the Board’s consideration prior to

hearings.

67

The Board considers victims important stakeholders in the process and employs a victim’s

advocate to assist victims navigate the parole process. On its website, the Board states explicitly

that it does not “want to contribute to [victim’s] pain”

68

The Board states: “we encourage you to

participate only to the extent appropriate for you and to seek information as needed.

69

Options to participate include: attending the hearing and speaking at the hearing, attending

a hearing and choosing to not participate, submitting a written statement in advance of the hearing,

and asking a written statement to be read into the record at the hearing. Victims services staff are

available to discuss the appropriate option depending on the needs of the victim.

70

63

Chapter 255 of the Oregon Administrative Rules contains administrative rules relevant to the Board of Parole and

Post-Prison Supervision. Or. Admin. R. 255-005-0005(59) defines victims broadly as

(a) Any person determined by the prosecuting attorney, the court or the Board to have suffered direct financial,

psychological, or physical harm as a result of a crime that is the subject of a proceeding conducted by the State

Board of Parole and Post-Prison Supervision.

(b) Any person determined by the Board to have suffered direct financial, social, psychological, or physical harm

as a result of some other crime connected to the crime that is the subject of a proceeding conducted by the State

Board of Parole and Post-Prison Supervision. The term “some other crime connected to the crime that is the

subject of the proceeding” includes: other crimes connected through plea negotiations, or admitted at trial to

prove an element of the offense. The Board may request information from the District Attorney of the

committing jurisdiction to provide substantiation for such a determination.

(c) Any person determined by the Board to have suffered direct financial, social, psychological, or physical harm

as a result of some other crime connected to the sentence for which the offender seeks release that is the subject

of a proceeding conducted by the State Board of Parole and Post-Prison Supervision. The term “connected to

the sentence for which the offender seeks release” includes other crimes that were used as a basis for: a departure

sentence, a merged conviction, a concurrent or a consecutive sentence, an upper end grid block sentence, a

dangerous offender sentence, or a sentence following conviction for murder or aggravated murder. The Board

may request information from the District Attorney of the committing jurisdiction to provide substantiation for

such a determination.

64

OR. CONST. art. I, § 42.

65

Or. Rev. Stat. 114.750.

66

Or. Admin Rule 255-030-0026 (f).

67

See generally Or. Admin. R. 255-030-0035(3) (providing that “[t]he Board must receive any information pursuant

to this section [relating to hearing procedures] at least fourteen days prior to the hearing. The Board may waive the

fourteen-day requirement.”).

68

https://www.oregon.gov/boppps/Pages/Victim-Services.aspx

69

Id.

70

Id.

18

Attorneys

Three main types of attorneys that operate within the context of parole: defense attorneys

who represent petitioners (typically they are only provided to the petitioner in one type of hearing),

prosecutors from the committing jurisdiction, and victims’ rights attorneys.

Defense Attorneys

A petitioner only has a right to counsel at a parole hearing in limited circumstances. In the

majority of hearing types, including Parole Consideration, Exit Interview, Parole Hearing and

Personal Interviews, the petitioner is not entitled to counsel. The petitioner may hire a private

attorney, bring a support person, or can represent themselves. In most instances, the petitioner

appears on their own, pro se.

If the petitioner is appearing for a Murder Review hearing, they are entitled to counsel.

71

Attorneys appointed to represent petitioners in Murder Review hearings receive a flat fee payment

of $1,900.

72

There are very few attorneys that represent petitioners regularly before the Board. In

most cases, the work requires 50-70 hours to do well. As a result, parole defense attorneys are

compensated far less than even their public defense counterparts. The complexity of the case is

not a consideration for the compensation provided. And there is no funding available for experts,

investigators, administration, mental health evaluations, or travel which is available in all public

defense cases.

The work of a parole defense attorney is complex. Attorneys representing petitioners must

walk a delicate tightrope when advocating for their clients’ best interests; attorneys must make a

record of objectionable evidence submitted to the Board, direct the Board to relevant case law for

each hearing and legal issue, and must do so while understanding that the Board sits both as

factfinder and decisionmaker.

To be effective, attorneys representing petitioners must understand their clients’ crime

narrative, motivations behind the crime of commitment, and life in Oregon DOC custody for the

decades preceding the hearing. The attorney has to build a relationship of trust and candor with

their client to learn about the client’s life, probe for more information where appropriate, and work

with the client to tell their story in a way that is both digestible for the Board and consistent with

the client’s personal sense of truth.

Prosecutors

Prosecutors from the jurisdiction where the petitioner was sentenced may appear at parole

hearings.

73

The Board’s rules allow prosecutors to submit written and oral statements for the

Board’s consideration. The same rules specifically allow prosecutors to comment on their views

regarding the petitioner before the Board and the crime at issue.

Prosecutors may submit information related to the underlying crime, including police