November 2021

The New Mexico Early Childhood

Education and Care Department

Four-Year Finance Plan 2023-2026

2

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

Acknowledgments

The Early Childhood Education and Care Department engaged Prenatal to Five Fiscal Strategies

to lead the nance plan process, including the development of scal models for revenue, service

planning and expenses, across all elements of the new Department, engagement with stakeholders

and the development of the four year plan. The authors, Jeanna Capito, Simon Workman, and

Jessica Rodriguez Duggan, would like to thank the commitment of the following individuals and

organizations to this work:

Children, Youth and Families Department

Children’s Cabinet (Mariana Padilla)

Department of Finance and Administration

(Secretary Romero, Meribeth Densmore)

Department of Health

Early Childhood Education

and Care Department

Early Learning Advisory Coalition

Growing Up New Mexico

Human Services Department

Legislative Finance Committee sta

(Jon Courtney, Kelly Klundt,

Charles Sallee)

NM Association for the Education

of Young Children

Pritzker Prenatal-to-Three Coalition

Public Education Department

The partnership of the Legislative Finance Committee sta over the course of regular meetings

from May through August was invaluable to the structure of the analysis, the stratication of data,

and the linkage to other state departments for critical data on population needs. In addition, the

understanding of services, costs and programs, along with the strengths and needs of families and

communities, could not have been achieved without the engagement of child care providers, home

visiting programs, preschool sta, early intervention providers, and public and private organizations

serving New Mexico’s families and children throughout the state.

Suggested Citation: Jeanna Capito, Jessica Rodriguez-Duggan, Simon Workman, “New Mexico Early

Childhood Education and Care Department: Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026” (Prenatal to Five

Fiscal Strategies, 2021).

3

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

Office of the Secretary

PO Drawer 5619

Santa Fe, New Mexico 87502-5619

(505) 827-7683

www.nmececd.org

MICHELLE LUJAN GRISHAM

GOVERNOR

HOWIE MORALES

LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR

STATE OF NEW MEXICO

EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION AND CARE DEPARTMENT

ELIZABETH GROGINSKY

CABINET SECRETARY

JOVANNA ARCHULETA

ASSISTANT SECRETARY for Native American Early

Childhood Education and Care

DR. KATHLEEN GIBBONS

DEPUTY SECRETARY

Dear Governor Lujan Grisham and New Mexico Legislators,

I want to thank you for your steadfast commitment and dedication to improving the lives

of New Mexico’s families and young children. This is evidenced through your substantial

and critical investments in our prenatal to five early childhood system, the creation of the

new department, and your visionary decision to establish the Early Childhood Trust Fund

to ensure the new department would have the resources needed to improve outcomes

for all families, children, and communities.

As the first cabinet secretary for New Mexico’s Early Childhood Education and Care

Department (ECECD), it is my honor and privilege to present to the New Mexico

legislature and Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham ECECD’s first Four-Year Finance Plan.

As required, this plan includes demographic information on at-risk children, data on the

efficacy of early childhood education and care programs and recommendations for

financing the prenatal to five early childhood system (NMSA 1978, §9-29-12 (2000)).

Into the pages of this report are woven the stories of every New Mexican family and

young child. In sharing these stories, we acknowledge the land upon which these stories

were and will continue to be created. This plan is a present, living document that

acknowledges our past, sheds light upon our current experience, and, above all,

embraces our envisioned future - a future in which all New Mexican families and young

children are thriving. Our intent with this plan is not to motivate us into action - we have

already begun this most imperative work.

ECECD will not allow this plan to collect dust - we will use it to hold ourselves and others

accountable and to ensure that our strategies and actions yield the results we intend - a

cohesive, equitable and effective prenatal to age five early childhood system that

supports families, cares for and educates our youngest residents, and builds strong

communities. We are grateful for and humbled by this monumental opportunity, which

we cannot and will not squander.

Sincerely,

ELIZABETH GROGINSKY

Cabinet Secretary

Table of Contents

Section I The Need for a Systemic Approach to Financing the Prenatal to Five System

Section II Towards a Comprehensive Early Childhood System in New Mexico

Section III New Mexico Early Childhood Education and Care Four-Year Finance Plan

Section IV Narrative Action Plan

Conclusion

The Fragmented Fiscal System

The Disproportionate Impact on the Prenatal to Five Workforce

Identifying Strategies to Address the Fragmented Market

New Mexico’s Vision for the Prenatal to Five System

Shared Leadership and Administration

Financing Strategies and Funding Mechanisms

Assessment and Planning

Quality Improvement, Implementation and Evaluation

Professional Development, Training and Technical Assistance

Monitoring and Accountability

Understanding the Need for Services

Understanding the Cost of Services

Understanding Current Revenue and the Total Funding Need

5

11

13

13

17

29

34

34

35

35

36

37

37

37

6

8

9

9

5

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

Section I The Need for a Systemic Approach to

Financing the Prenatal to Five System

N

ationally, the prenatal to age ve eld

of programs and services is facing

a critical juncture. All the discrete

sectors and programs for children and

families in this age group are confronted with

the realities of capacity failing to meet demand,

funding that lacks stability, and a historical

disconnect in understanding the real costs and

funding needs. Additionally, the current funding

structures force prenatal to age ve programs

and services to deal with multiple entities

who often have disconnected and conicting

approaches and administration requirements.

These funding structures drive siloed practices

in the development and delivery of programming

and often result in complex and onerous

management structures which discourage

the collaboration and business practices

necessary to create a cohesive, equitable and

eective prenatal to ve system in states and

communities.

The COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated

these issues across the country, destabilizing

child care programs and increasing the needs of

families and children. The federal relief dollars

to help programs rebound oer an exciting

opportunity to rebuild a better system, but it

is critical that the mistakes of the past are not

replicated and that this new funding is deployed

in a strategic way, that maximizes impact and

minimizes burden on providers and families.

Increasingly, states and communities are

acknowledging that programs for young children

too often work in isolation and face capacity and

resource limitations that hinder their

ability to meet the ever-growing and diverse

needs of families and young children. These

programs’ attempts to address complex social

problems – such as ensuring the best outcomes

for children and families, increasing positive

indicators of child health and well-being,

eliminating disparities related to socio-

economic status, providing culturally relevant

practices, and increasing indicators of school

readiness - are hampered by the lack of a

well-funded and robust system that aligns and

integrates investments from the prenatal

period to ve years old. As a result, the

sectors and organizations across the early

learning, family support, and health systems

have been forced into practices that lean

toward isolated impact – inventing independent

solutions to broadly sweeping social issues and

often competing for funding to sustain these

solutions.

1

1 Kania, J. and Kramer, M. (2011) Collective Impact. Stanford

Social Innovation Review, Winter 2011. www.ssireview.org

6

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

The Fragmented Fiscal System

One of the most complex challenges raised

in the National Academies of Sciences,

Engineering, and Medicine 2018 report

Transforming the Financing of Early Care

and Education is the patchwork of dierent

funding sources and nancing mechanisms,

which reinforces how issues of isolated

impact and siloed approaches stem in large

part from how programming and systems are

funded. The report underscores the issues that

result from an uncoordinated patchwork, or

non-functioning system, including inequities

in access, quality, aordability, cultural

responsiveness, and accountability, critical

issues that are most acutely felt by the

children and families early childhood programs

are designed to serve

2

. Funding sources and

mechanisms vary in their implementation

requirements and contract approach, based

on the funding entity, and have their own

standards, and reporting requirements.

These variances and the lack of common

understanding of them across the birth to ve

system puts stakeholders at a disadvantage

when attempting to develop policies, develop

funding mechanisms, and implement systemic

changes which will result in eciencies

and economies to benet family access and

program quality.

The process for funding the services and

programs in the prenatal to ve period

represent a fragmented and broken model,

funding that has never met the reality of the

cost of the services. Additionally, sta make

accommodations (e.g. use of personal funds

for materials, working nights and weekends,

management sta working in classrooms

to maintain coverage etc.) to maintain the

work and attempt to meet family needs that

2 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Med-

icine, “Transforming the Financing of Early Care and Education”

(Washington: National Academies Press, 2018) available at http://

www.nas.edu/Finance_ECE

are untenable, at best. Many of the dierent

programs across the prenatal to ve system,

including child care, home visiting, parent

support, and early intervention experience these

accommodations making it extremely dicult to

sustain the system, provide fair compensation

for the workforce and the quality programming

families and young children need. These

accommodations include:

• low wages, poverty level in most

communities and limited benets for

sta;

• reliance on women, particularly woman

of color, who are undervalued for their

role in child rearing and domestic

eorts; and

• funding mechanisms linked to available

funding, not actual cost of service;

silos across state sectors that are

all seeking to serve and impact the

prenatal to ve period.

Identifying the true cost of providing

programming for young children and families is

critical to addressing the underfunding of the

system. In the early care and education space,

public funding amounts have been determined

based on the market price of child care, which

in turn is constrained by what families can

aord to pay. The result is an inequitable

system, where providers who operate in higher-

income neighborhoods can set tuition rates

closer to the actual cost of programming,

which in turn generates a higher subsidy

reimbursement rate, while those in low-income

communities have to set tuition rates lower

in order to be accessible to their community,

resulting in a lower subsidy reimbursement

rate. This approach also acts as a disincentive

for programs to serve children where the gap

between what it costs to provide care and the

amount families can aord to pay is greatest.

7

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

Providers also face a disincentive to invest in

quality because the current funding approach

fails to compensate providers for the higher

costs of operating at higher quality levels. Not

only does this approach impact the availability

of quality early care and education opportunities

for young children but it also places a heavy

burden on the workforce. Despite increases in

public funding over the past decade, child care

wages have remained largely stagnant, with

educator compensation constrained by the lack

of funding to cover the true cost of education

and care. With the move to alternative

methodology for rate setting, New Mexico is

leading the country in using the actual cost of

care and quality to inform subsidy.

Much of this is also true for other prenatal

to ve programs where a contract or grant

approach dictates how much revenue is

available to a program, irrespective of the cost

of delivering the service. For example, early

intervention programming relies on rates paid

out by contracts - true costs of services are not

the driver in making these contract decisions.

In addition, costs increase year after year

often without an increase in the payment rate.

Therefore, the payment rate does not cover the

cost of the service. Early intervention programs

are faced with heavy caseloads and stang

shortages due to low compensation and high

workload.

Home visiting and parent education programs

often see the same challenges that exist in the

early intervention sector. Contracts to these

programs are often competitively oered,

which forces smaller, community-based

organizations - which may be more reective

of the community the services are designed for

- to compete with large entities, who typically

win the grant due to their infrastructure and

organizational capacity. These larger entities

may not serve communities that have the

greatest need for the services, or the ability to

truly engage the hardest to reach families, yet

they win in a competition for the funding due to

their organizational acumen. This demonstrates

that families with the greatest need are not

necessarily receiving the services they can

most benet from nor receive services from

the program and sta which best reects their

linguistic and cultural diversity. Home visitors

are professionals who take on an enormous

amount of stress as they work with many

families with varying needs. However, they are

not compensated anywhere near the level they

should be for the amount and type of work

they do for families of young children. At no

point was this more apparent than during the

pandemic as home visitors took on even more to

best support the families they work with.

Each program that is part of the prenatal to ve

system can benet from robust quality supports

that enhance professional development and

increase the quality of services oered. Many

of these supports are embedded in contracts,

and are a small piece of the overall budget.

Quality supports for child care, home visiting,

parent education, and early intervention are not

resourced at the level truly needed to provide

the professional training, capacity building and

access to sta mental health that is needed for

the type of emotionally and trauma-responsive

work this relationship-based service presents.

Providers are burnt out and frustrated; leading

to high turn-over which in turn aects families

and young children. The work providers

undertake is valuable and essential - yet they

are not compensated or supported in the way

they should be. While contracting for services

removes the market from the determination

of rates, if that contract is based on available

resources rather than an accurate accounting

of what it actually costs to provide all of the

services needed, programs still face signicant

gaps between these costs and revenue available

to cover that cost. Across the prenatal to ve

system, the impact of these gaps often falls

heaviest on the workforce.

8

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

The Disproportionate Impact

on the Prenatal to Five Workforce

The prenatal to ve workforce performs a

critical service, providing care and education

to young children and support to families at

a critical time in their lives. This support not

only includes child care and preschool, but

also family support services such as parent

education, home visiting, and early intervention

programs. Unfortunately, this work has long

been undervalued, with most providers and sta

in the eld barely making a livable wage. Child

care workers are paid an average of $12.34 an

hour nationally and only $10.26 per hour in New

Mexico, and PreK teachers make only marginally

more.

3

These poverty level wages across the

dierent sectors of the workforce lead to high-

turnover, which can harm child development

given research showing the benets of stable

caregiving arrangements during a critical time in

brain development.

4

In addition to low pay, child care providers are

often unable to provide health insurance and

other benets to educators and sta, leaving

the workforce relying on public assistance or

other family members to survive.

5

Many family

support programs report hiring sta at part

time in order to avoid the expense of having to

include health insurance in compensation, as

the revenue streams do not cover the full cost

to deliver the service. For the home-based child

care providers this reality is magnied, with

most providers realizing actual hourly wages far

below minimum wage when accounting for the

3 Bureau of Labor Statistics “Occupational Employment

Statistics, May 2020” available at https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/

oes_nm.htm

4 Daphna Bassok, Anna J. Markowitz, Laura Bellows, and

Katharine Sadowski, “New Evidence on Teacher Turnover in Early

Childhood” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, March 2021,

Vol. 43, Issue 1, pp 172-180. Available at: https://journals.sage-

pub.com/doi/10.3102/0162373720985340; https://www.nap.edu/

read/19401/chapter/11

5 Caitlin McLean, Lea J.E. Austin, Marcy Whitebook and

Krista Olson, “Early Childhood Workforce Index – 2020” (Berkeley,

CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of

California, Berkeley, 2021). Available at: https://cscce.berkeley.edu/

workforce-index-2020/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/02/Ear-

ly-Childhood-Workforce-Index-2020.pdf

long hours they work, and the minimal revenue

remaining at the end of the month once all

expenses are paid. Similar nancial challenges

are seen within the family support sector, as

sta are often times paid the bare minimum

and they too rely on public assistance and

additional income provided by family members.

Building a cohesive, equitable, and eective

prenatal to ve system that can meet the needs

of all families and young children will require a

stable professional workforce and a pipeline of

future talent. This in turn requires investments

in professional compensation for early childhood

professionals (e.g. early interventionists,

teachers, home visitors etc.), improvements

in the early childhood preparation programs,

and ongoing professional development. As

such, workforce compensation must be at the

heart of any initiatives intended to support the

prenatal to ve system. Without professional

compensation (i.e salary, paid time o, and

benets), the system will never meet the full

spectrum of needs faced by families and young

children.

New Mexico has taken steps to address this

need by moving to paying child care subsidy

rates based on a cost estimation model rather

than market price. This cost estimation model

includes a $12.10 minimum wage for low-skilled

sta working in facilities licensed at the basic

level, sets rates for family child care home

providers comparable to lead teachers in child

care settings, and includes the cost of health

insurance. While state leaders acknowledge that

salaries need to increase beyond this minimum

wage, the cost model reects that the high

proportion of total cost is compensation (60-70

percent), New Mexico has laid the groundwork

for sustained and future investments in

professional compensation by using the model

for rate setting.

9

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

Identifying Strategies to Address

the Fragmented Market

To meet the needs of families and young

children and address the inequities within the

prenatal to ve system will require a signicant

increase in public funding. However, it is also

necessary to alleviate the silos and barriers

that add excessive complexity and cost to

the system and ensure that increased public

funding is coupled with a more ecient system.

At the systems level it is important to align

program requirements, eligibility, and reporting

as much as possible to remove the burden from

providers and families when accessing multiple

programs and funding streams. Payment

practices should also reect the reality of how

providers and families operate within the system

and start from a point of positive support rather

than compliance and accountability. New Mexico

already moved to paying child care assistance

based on enrollment rather than attendance,

which provides for some stability in providers’

nances. States also have the option to further

align child care assistance payment policies

with tuition payment policies by providing

payment in advance rather than after the service

has been delivered. This ensures that providers

with minimal reserves have funds available

to cover their expenses as they are incurred,

rather than carrying debt until the child care

assistance payment is received. States can also

move to purchasing child care slots through

contracts rather than the individual voucher-

system that currently exists. Not only can

these slot purchase contracts be set at the

cost of quality, rather than market rate, but

they can also promote stability by guaranteeing

a set amount of income over the course of

the contract. Strategies such as these are an

important part of rebuilding the prenatal to ve

system in a way that better aligns with the goals

of funding streams and promotes eciency.

Understanding the impact of such policies and

identifying additional strategies to support the

system and address inequities is a critical part

of the scal analysis that is necessary to achieve

system goals.

ECECD is also re-designing the state’s home

visiting system. An initial scal analysis and data

collection of the current New Mexico system,

suggests that the current system is not scally

ecient and does not meet the true needs

of the communities across the state. Limited

number of models are available; therefore,

providing expensive services to families that

may not need highly intensive services, but

then not providing intense-enough services

to families with higher needs. Since families

present with a continuum of needs, coordinating

and implementing dierent models with varying

service intensity has been identied as a

strategy that will improve service coordination

and outcomes for families and young children

and eciently maximize funds.

New Mexico’s Vision for the

Prenatal to Five System

To address the complexity of the needs of

children and families and the non-system in

which those needs exist, requires states to set

a vision for how to increase investments, better

align current investments, and develop funding

and governance structures that maximize

eciency and minimize burden. Through

this comprehensive approach to the Early

Childhood Education and Care Department’s

Four-Year Finance Plan, New Mexico is thinking

strategically about the best way to fund the

prenatal to ve system, how partners at all

dierent levels can best collaborate, and what

role communities, sovereign nations, the federal

government, business, and philanthropy should

play. New Mexico’s scal vision for the prenatal

to ve system is in service of the statewide

vision for young children:

10

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

A prenatal to ve system that meets the

needs of every child and family and is

supported by sucient and stable funding

streams that provide maximum exibility

for families, ecient administration and

infrastructure, and minimum burden for

program providers.

Operationalizing this scal vision is supported by

a set of guiding principles. These principles drive

the important work of a cohesive, equitable, and

eective prenatal to ve system to best support

families and young children. These principles

focus on a system that:

• works for all children and ensures that

programming reaches and positively

impacts those children farthest from

opportunity.

• is fair to providers and supports

their developing capacity for quality

implementation.

• compensates the workforce at a level

that allows for nancial stability and

acknowledges their signicant impact on

child development.

• uses public resources wisely and

eciently, augmenting private resources

from those families who can aord

services.

• acknowledges embedded societal

inequities and implements changes to

remediate inequity.

• supports the entirety of a child’s

experiences before entering kindergarten,

including prenatal supports for expectant

mothers.

This system brings together family support,

education, maternal health, and child health

sectors to coordinate funding eorts and goals

needed to create an equitable and accessible

system for families. Families of young children

benet most when investments are made in a

systemic manner to truly meet the unique needs

of their community, and are based on intentional

and meaningful funding practices across the

state and community levels.

11

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

Section II Towards a Comprehensive Early

Childhood System in New Mexico

Under the leadership of Governor Michelle

Lujan Grisham and her Children’s Cabinet, New

Mexico has taken signicant steps in recent

years demonstrating the state’s commitment

to a systemic approach to early childhood

education and care. In 2019, the Governor signed

the Early Childhood Education and Care Act

into law, which created the New Mexico Early

Childhood Education and Care Department

(ECECD). The Act also created the position of

Assistant Secretary for Native American Early

Education and Care and required ECECD to

prepare and update a four-year nance plan

with recommendations for nancing the early

childhood education and care (ECEC) system.

In 2020, the Governor enacted, with bipartisan

legislative support, the Early Childhood Trust

Fund (ECTF) that distributes funds annually

to ECECD, and in 2021, the NM Legislature

approved House Joint Resolution 1 allowing

voters to decide whether a portion of the state’s

Permanent Land Grant can fund ECEC. These

activities represent NM’s intentions to address

the fractured governance of and limited funding

for programming for families and young children.

The creation of ECECD brought together pro-

grams that previously resided within several

other agencies of state government. As of July

2020, the NM ECECD administers child care

licensing and assistance, Child and Adult Care

Food Program, Families FIRST, a perinatal case

management program, Part C of the Individuals

with Disabilities Education Act, Head Start State

Collaboration, federal and state home visiting,

NM PreK (public and private), quality initiatives,

and early childhood workforce development.

As New Mexico works to build a more cohesive,

equitable, and eective prenatal to ve early

childhood system, ECECD uses a rich tapestry

of recommendations, plans, and priorities

from key stakeholders and communities with

clear next steps for necessary governance and

scal strategies. These include the ECECD

Transition Committee’s strategic priorities

and action plans, the ECECD Advisory Council

12

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

recommendations, the New Mexico Early

Childhood Strategic Plan, and the Pritzker

Children’s Initiative Prenatal to Three Policy

Implementation Plan. The comprehensive nature

of ECECD’s approach is further solidied by not

only working across the various sectors, early

care and education, maternal and child health

and development, family support, but also

engaging in work across all system components.

The comprehensive system work embedded in

New Mexico’s approach includes the following

components:

• Governance and Shared Leadership

• Financing and Fiscal Strategies

• Assessment and Planning

• Continuous Quality Improvement and

Implementation

• Professional Development and

Technical Assistance

• Monitoring and Accountability

With this Finance Plan, ECECD is working deeply

on scal strategies and funding mechanisms.

Changes in response to the nance plan, along

with the new Department’s infrastructure,

will encompass analysis and improvements in

governance and accountability mechanisms. As

part of creating the ECECD Four Year Finance

Plan, the newly formed department has built

an action plan to support implementation; this

action plan underscores how necessary each

of these components of the system is to the

system wide change and the clear intersection

of scal strategies with all aspects of prenatal

to ve programming. For the scale of work

discussed, which is designed to encompass

meeting all children’s needs, a system-wide

lens to not just the nancing but also the full

functioning of all elements of the direct service,

quality support and infrastructure is needed to

achieve this work.

13

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

Section III New Mexico Early Childhood Education

and Care Four-Year Finance Plan

As evidenced above, New Mexico’s commitment

to improvement of the overall early childhood

system is steadfast. Part of the work in

executing New Mexico’s vision is a deep

understanding of both the need and the cost

of the services provided across child care,

PreK, home visiting, and Family, Infant, Toddler

(FIT) programming. The Four-Year Finance Plan

highlights important data for both identifying

needs and justifying costs across the four

dierent programs from FY23 through FY26.

Understanding the Need

for Services

The number of young children and families

that need access to child care, PreK, home

visiting, and FIT is estimated based on birth rate

projections, provided by the University of New

Mexico Geospatial and Population Studies unit.

For the purposes of this Finance Plan, ECECD

is using the ‘low birth rate projection’ provided

by UNM which assumes that fertility rates will

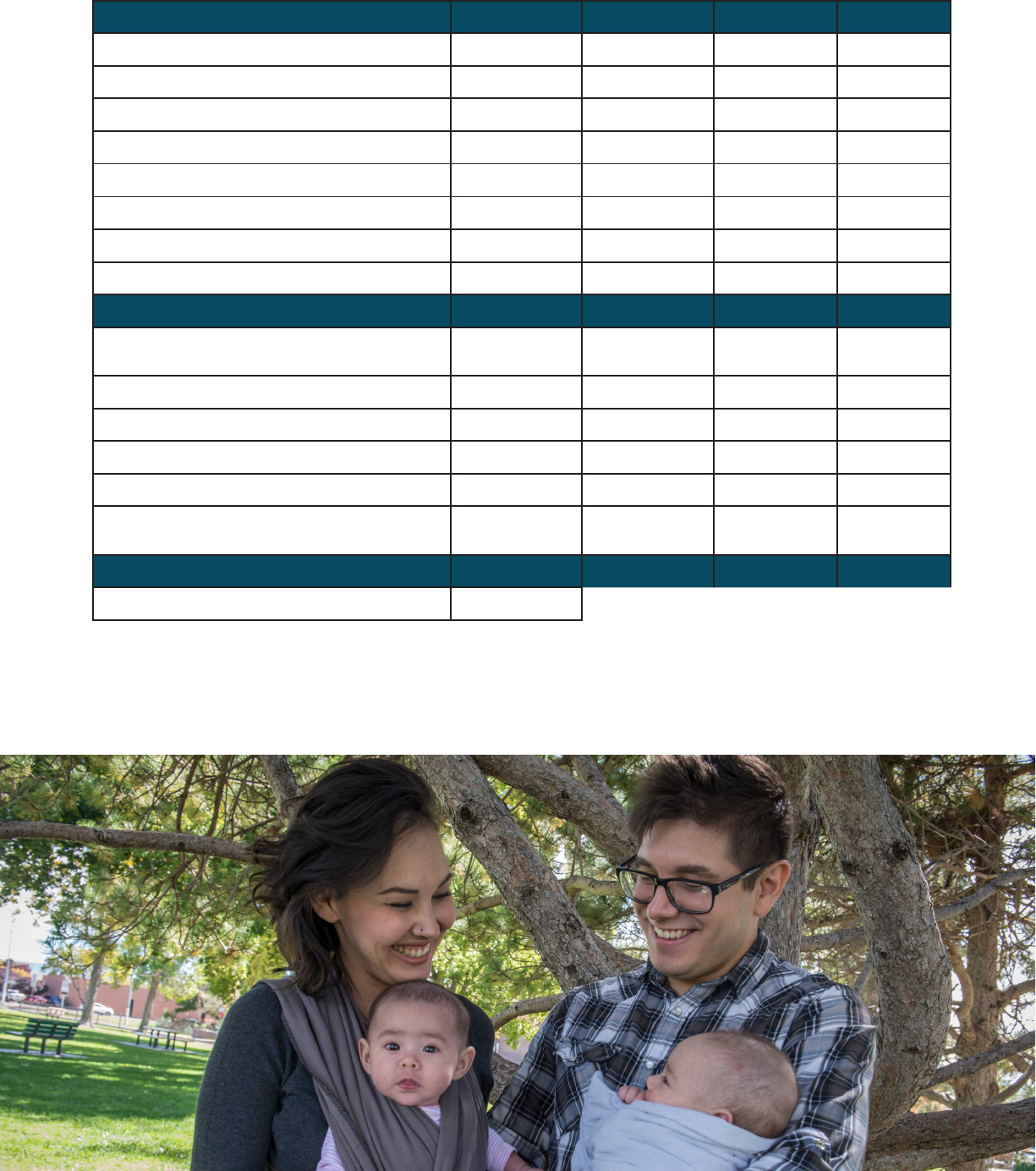

continue their current downward trend. Table

1 provides the estimated number of children in

each age cohort from 2022 to 2026. The number

in the 0–1-years row indicates the projected

births in that year. Numbers for older children

are drawn from prior year projections, or actual

births where available. As shown in the table,

births are estimated to decrease each year at a

rate of around two to three percent.

Each program funded and administered by

ECECD is intended to support a specic need

and as such each program applies its own

methodology to the data in Table 1 to estimate

the number of children and families to be

served.

14

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

Table 1: Birth cohort projections, by age, by year

Child Care Assistance

In 2021 New Mexico expanded access to

subsidized child care to families earning up

to 350 percent of the federal poverty level,

which is just over $92,750 per year for a family

of four.

6

To estimate how many families and

children qualify for subsidized child care at this

level, ECECD used the birth cohort projections

provided in Table 1 as a starting point. Based

on income eligibility thresholds, it is estimated

that 85 percent of New Mexico families would

meet the eligibility requirements for child care

assistance, so the total eligible population was

estimated at 85 percent of each age cohort.

From this, the numbers were further adjusted

to account for the fact that not all families need

care.

According to the American Community Survey

census data, approximately 63 percent of

young children in New Mexico have all available

parents in the workforce as of 2021.

7

Therefore,

6 New Mexico Early Childhood Education and Care Depart-

ment, “Child Care Assistance Income Guidelines, April 2021-March

2022” available at: https://www.nmececd.org/wp-content/up-

loads/2021/07/Poverty-Guidelines-2021-to-include-400-FPL.pdf

7 The Hunt Institute, “New Mexico Early Childhood Edu-

cation and Care Department Transition Committee, Final Report

and 18-Month Action Plan,” November 2020, available at: https://

hunt-institute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/New-Mexico-ECE-

CD-Transition-Committee-Final-Report-18-Month-Action-Plan.pdf

the projections were further reduced by this

percentage, to reect the population who will

need care. Research has shown that there is a

strong link between parental employment and

access to aordable child care; when families

have access to aordable child care and

preschool they are more likely to work, work

longer hours, or attend school.

8

As New Mexico

continues to invest in child care assistance over

the period of this Finance Plan, it is assumed

that parental employment will increase, which

in turn will increase the need for child care.

This increase is reected in the estimates for

how many children will need child care each

year, increasing from 63 percent in FY22 to 67

percent in FY26. Table 2 summarizes the total

potential need for child care assistance for FY23

through FY26.

8 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Oce of

the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “The Eects

of Child Care Subsidies on Maternal Labor Force Participation in

the United States” (Washington, 2016) available at: https://aspe.

hhs.gov/eects-child-care-subsidies-maternal-labor-force-par-

ticipation-united-states; Rasheed Malik, “The Eects of Universal

Preschool in Washington, D.C.” (Washington: Center for American

Progress, 2018) available at: https://www.americanprogress.org/

2022 2023 2024 2025 2026

0-1 years

21,110 20,535 19,961 19,385 18,793

1-2 years

21,550 21,110 20,535 19,961 19,386

2-3 years

21,820 21,550 21,110 20,535 19,961

3-4 years

22,966 21,820 21,550 21,110 20,535

4-5 years

23,038 22,966 21,820 21,550 21,110

5-6 years

23,708 23,038 22,966 21,820 21,550

TOTAL UNDER 6

134,192 131,019 124,362 124,362 121,335

6-13 years

184,498 180,411 176,198 172,172 167,750

TOTAL 0-13 318,690 311,430 304,140 296,534 289,085

15

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

Table 2: Child Care Assistance estimated need, FY23-26

Table 3: NM PreK estimated need, FY23-26

PreK

Estimating the projected need for PreK requires

accounting not only for the number of three-

and four-year olds residing in the state each

year, but also an understanding of the other

settings in which children might be served. For

this age group, children can also be served by

Head Start, including Tribal settings, so the

projected need is adjusted accordingly (Table

3). In this Plan, ECECD uses birth cohorts,

instead of public school kindergarten enrollment

cohorts, for two fundamental reasons. First, this

ensures a consistent methodological approach

across all early childhood programs. Second, by

using the birth cohort all children are counted.

The department’s previous methodology only

took into account those students that enrolled

in the K-12 public school system, which did not

represent an accurate measure of PreK need.

In projecting PreK need, kindergarten enrollment

data is sometimes used in the eld, despite

its aforementioned limitations. In Section III,

the Plan does note the percentage of children

served using kindergarten enrollment cohorts

to compare the dierence in the percentage

of need when using the two dierent

methodological approaches. The birth cohort

projections from Table 1 were used as a starting

point, and then the number of children served

by Head Start was deducted from this total

to calculate an estimate of the number of

three- and four-year-olds potentially in need of

services through NM PreK.

FY23 FY24 FY25 FY26

0-1 years 11,346 11,198 11,040 10,702

1-2 years 11,663 11,520 11,368 11,040

2-3 years 11,906 11,843 11,695 11,368

3-4 years 12,056 12,090 12,022 11,695

4-5 years 12,689 12,241 12,273 12,022

TOTAL UNDER 5

59,660 58,892 58,398 56,827

5-6 years 12,728 12,884 12,426 12,273

6-13 years 99,677 98,847 98,052 95,534

TOTAL 0-13 72,388 71,776 70,824 69,100

FY23 FY24 FY25 FY26

3-4 years 18,170 19,325 17,888 17,904

4-5 years 19,316 18,170 20,785 20,808

TOTAL

37,486 37,495 38,673 38,712

16

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

Home Visiting

Research demonstrates that all families of

young children may benet from home visiting

services, yet not all types of home visiting will

meet the need of every family.

9

In this service

area, there is a continuum of types of programs

and intensity in services, which have dierent

costs per child served.

To understand need for home visiting, the

population of families of young children needs

to be broken down according to strata driven by

high need or at-risk characteristics, reective

of the populations in the state. As a rule,

population-wide stratication of need seeks to

sort the population in to high, moderate and low

risk, according to characteristics present in the

population. As part of this process for

New Mexico, several characteristics that put

families of young children farther from equal

opportunities, and their associated incidence

data for New Mexico, were reviewed, including:

9 Geary, C., Capito, J., and Duggan, J. (2020) Home Visiting

Provides Essential Services: Home Visiting Programs Require

Additional Funding to Support More Families. Georgetown Center

on Poverty and Inequality, Washington DC.

New Mexico has a high proportion of the

population who are covered by Medicaid during

pregnancy and through the birth of the baby; 74

percent of all pregnant women in New Mexico

are covered by Medicaid. Access to Medicaid

is an income driven eligibility, therefore nearly

three-quarters of all pregnant women in New

Mexico fall at or below 250 percent of the

federal poverty line. Many of the other at-

risk factors considered as part of the home

visiting need stratication process overlap

with the population of Medicaid eligible and

served families. Medicaid covered births was

established as the population of the high need

category with the acknowledgement of the need

to further stratify this high need population in

to tier 1, greatest need, those families in deep

poverty (50 percent or less of poverty and child

protective services involved) and tier 2, high

need families falling between 50 percent of the

poverty level and 250 percent of poverty.

The next stratication of need is the families

at moderate need, which make up 21 percent

of the birth cohort. The population in this

category include families eligible for TANF and

WIC benets, families with well managed or

moderate chronic health conditions, mother

or children, and maternal mental health risk

factors. For New Mexico, the low-risk category

is established at approximately 5 percent of

the birth cohort and represents the general

population with no known factors related to

high or moderate risk. Table 4 summarizes the

stratication of need by these three levels, with

tier 1 and 2 in high need, for the birth cohort

projections from FY23-FY26.

• Births covered by Medicaid

• Poverty level/deep poverty

• Child Welfare involvement

• Pregnant women in, leaving or within one

year of prison or jail release or detention

• Women aected by substance use

disorder

• Women aected by social emotional

disorders or mental health conditions

• Birth disparities/health disparities by

race/ethnicity that are prevalent in NM

• Women with high-risk chronic conditions

(physical or cognitive)

• Preterm birth (0-1) or major child chronic

condition (1-5)

• Women in abusive relationships

• Women experiencing homelessness

• Children with mild or moderate or well-

managed chronic conditions (physical,

cognitive, social/emotional)

• Families receiving TANF benets

17

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

Table 4: Home Visiting estimated need, FY23-26

Family Infant and Toddler

The determination of eligibility for the

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

Part C program is administered through ECECD’s

Family Infant and Toddler (FIT) program. FIT

diers from other services, as it is dictated by a

developmental delay or disability. IDEA is a state

and federally funded entitlement program for

children and adults with delays or disabilities.

Part C of this act is specic to services to

children and families from birth to three years of

age. Eligibility criteria for FIT services relates to

a percentage delay in the child’s development,

or one of several diagnoses or risk criteria within

the family unit. ECECD works in partnership with

local vendors in required Child Find

activities to ensure that children and families

who may qualify for services under FIT are

identied, screened, and assessed and enrolled

in the appropriate therapeutic services. As such,

New Mexico has a strong history of nding and

serving FIT eligible children and families. Using

year over year data from the last ve years of

services, the population eligible for FIT was

projected forward to FY26. In the case of FIT, it

is a requirement that those eligible are served

therefore projections on eligibility match with

the service projections for the FIT program

(Table 5).

Understanding the

FY23 FY24 FY25 FY26

Highest Need Strata (74% of

births, Medicaid eligible)

15,093 14,671 14,249 13,813

Tier 1: Births under 50% FPL

(59%) and CPS involvement (5%)

9,660 9,390 9,119 8,840

Tier 2: 50% FPL to all Medicaid

eligible births

6,188 6,015 5,842 5,663

Moderate Need Strata (21%

of births)

4,312 4,192 4,071 3,946

Low Need Strata (5% of

births)

1,027 998 969 940

18

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

Table 5: Family Infant Toddler estimated need, FY23-26

Cost of Services

ECECD has developed projections estimating the

cost to provide the services detailed above to

New Mexico children and families. These costs

fall into two categories: 1) the cost of the direct

service, and 2) the cost of infrastructure and

quality supports.

Direct Service

Child Care Assistance

To estimate the cost of providing child care

assistance to all families who need it, ECECD

used the cost estimation model developed in

2021 to inform child care assistance rate setting.

This model was informed by a cost study that

identied what it costs to meet state licensing

standards, with age, region and program level

variations, and the additional costs related to

increasing quality and workforce compensation.

FY23 projections use the child care assistance

rates established as of July 1, 2021, informed by

the cost estimation model. These rates provide

for a $12.10 minimum wage in both child care

centers and family child care homes, which was

the highest minimum wage in the state at the

time the model was developed. This minimum

wage oor applies to the lowest paid members

of the workforce for a program at the licensed

level, with other salaries adjusted proportionally;

Lead teachers and family child care providers

are compensated at $13.19 per hour under this

model. As providers increase their rating in the

state’s Tiered Quality Rating and Improvement

System (TQRIS), wages increase; for the FY23

estimates, lead teachers are compensated at

$16.73 per hour in a 3 Star program, $18.40 in

a 4 Star program, and $20.07 in a 5 Star rated

program.

For FY24 and FY25, the rates are increased

to ensure they are sucient to provide a $15

minimum wage to the child care workforce

in a program meeting minimum licensing

standards, which increases lead teacher wages

to $20.74 per hour. In FY26 the rates increase to

cover an $18 minimum wage, which increases

lead teacher wages to $24.89 per hour. In

addition, rates were increased to account for

ination. The estimates use data from the

Social Security Administration which uses a

2.4% annual increase as its benchmark. The

estimated baseline child care assistance rates

under these scenarios are detailed in Tables

6-9 below. These rates are used for programs

meeting minimum health and safety licensing

regulations; quality dierentials are paid on top

of these rates based on a program’s level in the

state’s TQRIS.

Estimating the overall cost of child care

assistance in each year required developing

a system-wide model that accounts for the

distribution of children across settings and

quality levels. ECECD used data on the current

distribution of children across settings, and

the distribution of program quality level across

these settings to inform these estimates. Table

10 illustrates the distribution of total capacity

across settings and quality levels. Further,

given the signicant dierence in the cost of

child care for children at dierent ages, it is

FY23 FY24 FY25 FY26

FIT Eligibility

24% 25% 26% 28%

0-3 years

15,167 15,402 15,569 16,279

TOTAL UNDER 3

15,167 15,402 15,569 16,279

19

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

Table 6: Monthly cost per child estimates, child care center, FY23-26

Table 7: Monthly cost per child estimates, small family child care, FY23-26

Table 8: Monthly cost per child estimates, group home, FY23-26

Table 9: Monthly cost per child estimates, registered home, FY23-26

important to also estimate the distribution of

children across settings by age. Based on the

number of children in each age cohort needing

care, ECECD estimates that 40 percent of the

total capacity needed is for children under two,

21 percent for children two to three, 13 percent

for three- to ve-year-olds and 26 percent by

Infant Toddler Preschooler School-age

FY23

$880 $635 $575 $441

FY24

$1,090 $774 $697 $510

FY25

$1,113 $791 $712 $521

FY26

$1,264 $890 $799 $577

Infant Toddler Preschooler School-age

FY23

$875 $850 $700 $412

FY24

$1,112 $1,080 $889 $560

FY25

$1,122 $1,090 $898 $565

FY26

$1,377 $1,377 $1,101 $648

Infant Toddler Preschooler School-age

FY23

$855 $830 $680 $428

FY24

$1,092 $1,060 $869 $546

FY25

$1,102 $1,070 $877 $551

FY26

$1,263 $1,226 $1,005 $632

Infant Toddler Preschooler School-age

FY23

$375 $375 $325 $300

FY24

$464 $464 $403 $373

FY25

$464 $464 $403 $373

FY26

$556 $556 $484 $447

school age children. This distribution was used

to inform estimates of the cost of providing

sucient capacity to meet the need. Combining

data on the cost per child - with variations by

setting, program quality level, and child age

– with the distribution of capacity by setting,

program quality level, and child age, allowed for

20

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

Table 10: Distribution of Capacity across Program setting, TQRIS level

an estimate of the total cost of providing child

care assistance to all who need it. Currently,

New Mexico serves approximately 45 percent of

all eligible children under six, and 6 percent of

eligible school-age children.

The Four-Year Finance Plan builds towards a

goal of serving 100 percent of eligible children

under age six by FY26. The saturation of eligible

children served increases each year to reach

this goal. The number of three- and four-year-

old children who need to be served by child

care assistance is adjusted to account for the

parallel increase in the number of children in

these age groups receiving access to NM PreK.

While a portion of these children will still

require care beyond the 6-hour PreK day, this

is anticipated to be aligned with the estimated

need of school age children rather than the

need of infants and toddlers. Table 11 details the

increase in eligible children served each year,

broken out by age. The total cost to provide

service at these saturation levels is detailed in

table 12.

Center Family Child

Care

Group Home Registered

Homes

% of total capacity

85% 6.5% 2% 6.5%

Licensed

5% 29% 26%

2 Star

6% 30% 26%

2+ Star

11% 26% 8%

3 Star

17% 3% 9%

4 Star

11% 5% 8%

5 Star

50% 7% 23%

21

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

NM PreK

New Mexico PreK supports access to high-

quality prekindergarten programming for

three- and four-year-olds in public school or

community-based sites. ECECD sets half-day

and full-day rates for NM PreK, with dierent

rates for 4-year-olds, 3-year-olds, and mixed

age classrooms.

Table 11: Estimated number of children to be served by Child Care Assistance FY23-FY26

Table 12: Estimated cost of child care assistance program FY23-26

Table 13: NM PreK Rates

FY23 FY24 FY25 FY26

Service Saturation – 0-5 years

47% 75% 85% 100%

0-1

5,332 8,399 9,384 10,702

1-2 years

5,482 8,640 9,663 11,040

2-3 years

5,596 8,882 9,940 11,368

3-4 years

1,700 1,700 1,700 1,700

4-5 years

1,500 1,500 1,500 1,500

TOTAL UNDER 5 19,610 29,121 32,187 36,310

Service Saturation – School age

7% 8% 9% 10%

5-6 years 891 1,031 1,118 1,227

6-13 years 6,977 7,908 8,825 9,553

TOTAL 0-12 27,478 38,060 42,130 47,090

FY23 FY24 FY25 FY26

Child Care Assistance

$213,092,489 $373,951,403 $416,304,137 $533,509,927

FY23 FY24 FY25 FY26

3-4 years

Part day

$4,375 $4,480 $4,585 $4,690

Full day

$8,750 $8,960 $9,170 $9,380

4-5 years

Part day

$3,500 $3,584 $3,668 $3,752

Full day

$7,000 $7,168 $7.336 $7,504

To estimate the cost of expanding access to

PreK through FY26, the current rates are used,

but adjusted for ination/cost of living from

FY24 through FY26 at a rate of 2.4% per year, in

line with Social Security Trustee estimates.

10

The rates used in the modeling are shown in

Table 13.

10 Social Security Administration, “COLA Estimates Under

the 2021 Trustees Report”, available at https://www.ssa.gov/oact/

TR/TRassum.html

22

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

New Mexico pays the same rate regardless of

setting, so adjustments are not made in the

cost estimates based on setting. However, the

estimates do make assumptions about how

many children participate in half-day PreK

compared to full day PreK.

In the nance plan projections, the number

of children served by full day programming is

increased each year.

New Mexico has a goal of providing universal

PreK to all families who want it. This four-year-

plan builds on the states progress to reach

this goal in FY26. To accurately estimate the

potential need for PreK, the data in Table 3

was adjusted to account for the experience

from states that have implemented universal

preschool who have found that around 75-85

percent of preschool-age children enroll in PreK.

The estimates are further adjusted to account

for children served through Title I. Table 14

illustrates the results of this analysis, identifying

the number of 3- and 4-year-olds estimated to

be served by NM PreK from FY23-26.

Table 14: Number and percentage of 3 and 4-year olds served by NM PreK

Table 15: Estimated cost of NM PreK FY23-FY26

Currently in FY22, 50 percent of 4-year-olds are

estimated to be served by NM PreK. A further 17

percent are served by Head Start, and 5 percent

by Title I. As a result, across Head Start, Title I

and NM PreK, 72 percent of the birth cohort will

be served. This is the equivalent of 80 percent

of the estimated kindergarten cohort.

11

In FY26, 61 percent of 4-year-olds are estimated

to be served by NM PreK. A further 11 percent

are served by Head Start, and 4 percent by Title

I. As a result, by FY26, across Head Start, Title I

and NM PreK, 76 percent of the birth cohort will

be served. This is the equivalent of 85 percent

of the estimated kindergarten cohort.

12

By FY26, 17 percent of 3-year-olds are estimated

to be served by NM Early PreK. A further 25

percent are served by Head Start and 3 percent

by Title I. As a result, by FY26, across Head

Start, Title I and NM Early PreK, 45 percent of

the 3-year-old birth cohort will be served. This

is the equivalent of 50 percent of the estimated

kindergarten cohort.

13

The total cost to provide

service at these saturation levels is detailed in

table 15.

11 Based on authors analysis of data from LFC estimating

kindergarten cohort, based on 90% of 2018 birth cohort.

12 Based on authors analysis of data from LFC estimating

kindergarten cohort, based on 90% of 2022 birth cohort.

13 Based on authors analysis of data from LFC estimating

kindergarten cohort, based on 90% of 2023 birth cohort.

FY23 FY24 FY25 FY26

3-year-olds

2,896 3,462 3,334 3,515

Percent of birth cohort

13% 16% 16% 17%

4-year-olds

11,737 12,060 12,895 12,904

Percent of birth cohort

51% 55% 60% 61%

FY23 FY24 FY25 FY26

NM PreK

$107,500,540 $112,419,370 $120,667,566 $125,622,136

23

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

Home Visiting

New Mexico has home visiting programming for

families from the prenatal period to ve years

of age. In the delivery of home visiting, the

most positive impacts on child development

and family well-being are achieved when the

program model is matched up with the needs

or risk factors of the children and families

served. A continuum of home visiting programs

is necessary to meet the various needs of the

children, families and communities served.

One home visiting model will not meet the

needs of all families or have the same impact

on all families. Home visiting programs are

developed with research on their service model

used with populations of families; from there

an evidence base for the impact of a given

home visiting model is developed. In order to

maximize investment in home visiting, states

use an understanding of need, such as the need

stratication completed for New Mexico (see

Table 4), to support selecting and implementing

home visiting models that are designed and

proven to have the desired positive impact on

child and family outcomes.

Home visiting models are not the same in their

delivery elements or intensity, and therefore

have dierent program costs. Models with

proven impact on the highest risk populations

are typically the most intense service models

and this intensity has a higher cost per child

family served annually. These are the models

designed to serve families in the highest need

strata. Services for families in the moderate

risk category are less intense, with fewer

touchpoints between the family and home

visitor and thus a lower cost per child/family

annually, and services for the low risk strata are

the lightest touch, least intense and typically

cost the least annually per child/family served.

With this need stratication process, combined

with analysis of current program model

implementation, ECECD is actively engaged

in a process to ensure the home visiting

services delivered to families are matched to

the family need and that program funding is

commensurate with the cost of the service.

For the purpose of planning, the cost per

family needs to be increased for the services

to families in the highest need strata and

more discernment of the cost per family

for the models used to serve families in the

moderate and low risk strata. Currently all home

visiting programs are paid between $4,500 and

$6,000 annually per family served, Table 16

demonstrates the approach to funding rates

through to FY26, which distinguishes among

need strata, increasing that rate and adds

services for the low risk category in future years.

Table 16: Annual Cost Per Family, by scal year

FY23 FY24 FY25 FY26

High Need, Tier 1

$6,000 $8,000 $8,000 $8,000

High Need, Tier 2

$6,000 $6,500 $6,500 $6,500

Moderate Need

$4,500 $4,500 $4,500 $4,500

Low Need

N/A $1,000 $1,000 $1,000

24

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

Table 17: Percentage and number of families served, by need stratication and scal year

Table 18: Universal touch model service numbers by scal year

Table 19: Total home visiting service numbers and estimated cost by scal year

Additionally, in scal year 2022, ECECD, in

partnership with the Department of Health,

launched a universal touch home visiting

model in Bernalillo County; through Family

Connects every family receives a connection

with a home visitor at the birth of their baby.

Families may receive one to three more visits

after this newborn connection, based on need

and families are linked to additional resources

through this process, including an intensive,

ongoing home visiting program, as appropriate.

This universal touch model is estimated to

have an annual cost per family of $500 and is

included in the nance plan modeling.

In order to project the costs of expanding

access to home visiting year over year, across

the dierent need levels, saturation amounts

were established, linked to each level of need. It

is a goal of ECECD to envision that the highest

need families are served with home visiting

aligned to their needs and funded at the actual

cost per child/family. In Table 17, the percentage

of the birth cohort aligned to each need level

that is projected to be served is delineated,

along with the number of children.

Table 18 outlines the service projections for the universal touch model, which has launched in FY22

and will increase in services each year.

The total numbers of children/families to be served by home visiting, across all the need levels and

service types, and the associated costs through FY26 is covered in Table 19.

Service Saturation by Strata

FY23 FY24 FY25 FY26

High Tier 1 served

2,898 (30%) 3,756 (40%) 4,104 (45%) 4,420 (50%)

High Tier 2 served

1,547 (25%) 2,406 (40%) 2,629 (45%) 2,832 (50%)

# Moderate Need served

647 (15%) 1,866 (45%) 1,832 (45%) 1,973 (50%)

# Low Need served

0 599 (60%) 775 (80%) 940 (100%)

FY23 FY24 FY25 FY26

Percentage of birth cohort

7% 30% 40% 50%

Annual Universal Service Numbers

1,437 5,988 7,754 9,396

FY23 FY24 FY25 FY26

Total Served

9,839 20,256 23,165 26,168

Estimated HV cost

$49,526,657 $92,585,705 $100,276,042 $108,713,168

25

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

Family Infant and Toddler

New Mexico Family Infant and Toddler program

has demonstrated high levels of accessing and

engaging the eligible population into Part C

funded services. While the state performs better

than many other states in this area, there is

some room for growth; however, estimates of

cost increases year over year are not driven by a

goal to saturate increasing amounts of the birth

cohort but instead to ensure eligible children

and families are served.

The payment rate for FIT providers was

increased in FY20 and FY21 to meet the rates

established in the 2017 rate study. A rate study

is planned for this year. An estimate of what

the increase would be, using the percentage

of previous rate increases as a basis, was

completed in order to project cost for the FIT

program through to FY26 (Table 21).

Table 20: Service projections in FIT program, by scal year

Table 21: Annual cost per child for FIT services and total annual costs based on service projections

Quality Supports And ECECD Infrastructure

Quality supports for programs and providers/

professionals are necessary to the delivery of

quality direct services to children and families.

These quality supports exist within an overall

system or infrastructure which must be

adequately funded to meet the size and capacity

of the system, ensuring coordination across the

system, access to services and resources, and

continually implementing improvements and

evaluation in order to ensure the high-quality

services are available. New Mexico has pieces of

these quality supports and overall infrastructure

in place for each of the program areas analyzed

and projected out in the four years of the

nance plan. While some of the areas of growth

in quality supports and infrastructure are clear,

there is a great need to focus on the concepts

of what quality supports are invested in,

whether these meet the program, professional

and system needs, and adjust the activities and

investments accordingly. This work is further

described in the Narrative Action Plan section

of this report and detailed in ECECD’s System

Action Plan, created in July 2021.

Growth in both quality supports and ECECD

infrastructure is projected, (see tables 22-

26) as the numbers of children and families

served year over year will increase. Additional

renement of the scale and types of

investments will occur as ECECD focuses on

these components of their system growth.

FY23 FY24 FY25 FY26

FIT Eligibility

24% 25% 26% 28%

0-3 years

13,903 15,402 15,569 16,279

FY23 FY24 FY25 FY26

Cost per child

$4,535 $4,762 $5,000 $5,250

Estimated FIT cost

$63,049,652 $73,338,093 $77,844,070 $85,463,022

26

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

Table 22: Child Care Quality Support and Infrastructure Expenses, FY23-26

Table 23: NM PreK Quality Support and Infrastructure Expenses, FY23-26

FY23 FY24 FY25 FY26

Child care slots

27,479 38,059 42,130 47,091

Licensed child care providers

850 900 950 1000

Families Served

16,164 22,388 24,783 27,701

Professional Development/ Training

$399,607 $510,654 $654,529 $810,563

QRIS Counsultation, Child Care Resource

and Referral and Statewide Training Registry

$4,670,000 $4,926,176 $5,182,353 $5,438,529

Child Care Data Management and Payment

System

$2,800,100 $3,000,000 $3,200,000 $3,400,000

Higher Education Grants

$3,500,000 $3,500,000 $3,500,000 $3,500,000

Call Center

$2,121,218 $2,121,218 $2,121,218 $2,121,218

Supply Building

$0 $2,500,000 $2,500,000 $2,500,000

Other

$56,702 $56,702 $56,702 $56,702

Child Care Regulatory Sta (Salaries

and Benets)

$2,600,500 $2,819,554 $3,047,624 $3,285,018

Child Care Assistance Sta (Salaries

and Benets)

$4,698,112 $4,810,864 $4,926,327 $5,044,559

TOTAL

$20,846,239 $24,245,168 $25,188,753 $26,156,589

Child care grants, capacity, and

business (CRRSA)

$7,000,000

Accelerated AA cohort (CRRSA)

$840,000

CC information sytstem (CRSSA)

$200,000

TOTAL Relief Funding

$8,040,000

FY23 FY24 FY25 FY26

PreK slots

14,633 15,522 16,229 16,418

Private PreK (community)

6,965 7,388 7,725 7,815

Public PreK

7,668 8,134 8,504 8,603

PreK Classrooms

813 862 902 912

PreK Parity Wage Supplement

$4,000,000 $4,242,921 $4,436,207 $4,487,966

Quality coaching and supports

$6,296,265 $6,678,639 $6,982,885 $7,064,357

Early childhood observation tool

$150,000 $150,000 $150,000 $150,000

LETR-S, Literacy coaching

$750,000 $750,000 $750,000 $750,000

NM PreK PSEB Stang

$965,210 $1,023,828 $1,070,468 $1,082,958

Total

$12,161,475 $12,845,388 $13,389,560 $13,535,281

27

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

Table 24: Home Visiting Quality Support and Infrastructure Expenses, FY23-26

Table 25: FIT Quality Support and Infrastructure Expenses, FY23-26

FY23 FY24 FY25 FY26

Families Served

9,839 20,256 23,165 26,168

Home Visitors

430 753 822 901

FY23 FY24 FY25 FY26

Children Served

13,903 15,402 15,569 16,279

Administrative Services (Falling Colors)

$1,386,746 $2,592,400 $2,807,729 $3,043,969

Centralized Intake and Referral

$0 $500,000 $500,000 $500,000

Reective Supervision, Continuous Quality

Improvement, Data Management, Parent

Education

$2,459,132 $2,435,749 $2,435,749 $2,435,749

Infant Mental Health Endorsement

$105,000 $105,000 $105,000 $105,000

Curriculim Support

$9,990 $9,990 $9,990 $9,990

Home Visiting Sta (Salaries and Benets)

$551,671 $967,233 $1,055,740 $1,157,146

Total

$4,512,539 $6,610,372 $6,914,208 $7,251,854

Data System

$199,053 $220,509 $222,912 $233,076

Third Party Medicaid Biller

$153,766 $170,341 $172,197 $180,048

Family Resource Centers

$302,800 $280,461 $283,517 $296,444

Continuous Quality Improvement

$491,946 $571,396 $577,622 $603,958

Interagency Coordinating Council

$64,475 $64,475 $64,475 $64,475

FIT Sta (Salaries and Benets)

$815,280 $957,267 $957,267 $1,000,913

Total

$2,027,320 $2,264,449 $2,277,990 $2,378,914

System Infrastrucutre (ARPA funded)

$624,252

28

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

FY23 FY24 FY25 FY26

Research and Evaluation

$1,000,000 $1,000,000 $1,000,000 $1,000,000

Annual Outcomes Reports

$195,646 $202,920 $202,920 $202,920

Higher Education Scholarships

$2,978,403 $2,978,403 $2,978,403 $2,978,403

Wage Supplement Program

$1,000,000 $1,000,000 $1,000,000 $1,000,000

Mentor Network

$732,913 $200,000 $200,000 $200,000

Dolly Parton Imagination Library

$275,000 $275,000 $275,000 $275,000

ECECD Sta (Salaries and Benets)

$10,071,659 $10,071,659 $10,071,659 $10,071,659

Other

$569,400 $277,000 $277,000 $277,000

New Initiatives:

Infant Early Childhood Mental Health

Consultation (IECHMHC)

$1,000,000 $2,000,000 $6,000,000

$8,000,000

Child Care Health Consultation

$0 $2,000,000 $3,000,000

$4,000,000

Food, Farm, and Hunger Initiative

$70,000 $1,000,000 $1,500,000

$2,000,000

Tribal Investments

$1,575,000 $3,100,000 $4,100,000

$6,100,000

Local Early Childhood System Building

$2,700,000 $3,000,000 $3,000,000 $3,000,000

Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery

Act (CARA)

$690,980 $690,980 $690,980 $690,980

TOTAL

$22,859,001 $28,295,962 $35,007,395

$40,723,057

Total Relief Funding

$2,268,007

Table 26: ECECD Quality Support and Infrastructure Expenses, FY23-26

29

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

Table 27: Child Care Assistance Funding Sources and Revenue projections for direct services by scal year

Understanding Current

Revenue and the Total

Funding Need

The next step in nance planning is to

compare current revenues to funding needed

to underscore gaps and places where needed

expenses are covered by funding. For New

Mexico and ECECD, this work builds on the need

and cost data gathered and analyzed across all

direct services and the current quality support

and infrastructure elements.

Sources

FY23 Operating

Budget Request

(9/1/21)

FY24

Projection

FY25

Projection

FY26

Projection

General Fund

$49,498,300 $49,498,300 $49,498,300 $49,498,300

TANF (Federal)

$31,527,500 $32,000,000 $32,000,000 $32,000,000

Other State Funds

$1,100,000 $1,100,000 $1,100,000 $1,100,000

CCDF (Federal)

$70,688,700 $73,512,000 $73,512,000 $73,512,000

CRRSA (ends 9/30/23)

$7,000,000 $0 $0 $0

ARPA Discretionary (ends 9/30/24)

$61,970,798 $0 $0 $0

Total Revenue

$221,785,298 $156,110,300 $156,110,300 $156,110,300

Projections, Children served

27,47 9 38,059 42,130 47,091

Projected Expenses amounts

$213,092,489 $373,951,403 $416,304,137 $533,509,927

Direct Service

For each area of programming the current

revenues were mapped, projecting out on

potential revenues through FY26. Tables 27

through 35 detail the projected revenues for

each service area. The revenue needed was

compared to these revenue projections, based

on the need and cost information specic to

each type of programming.

30

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

Sources

FY23 Operating

Budget Request

(9/1/21)

FY24

Projection

FY25

Projection

FY26

Projection

General Fund $15,276,694 $14,970,900 $14,970,900 $14,970,900

Title IV-E (Federal) $0 $0 $0 $0

TANF (TRANSFERS) $5,000,000 $5,000,000 $5,000,000 $5,000,000

Federal MIECHV $5,145,700 $5,146,000 $5,146,000 $5,146,000

Medicaid Centennial $20,000,000 $20,000,000 $20,000,000 $20,000,000

Medicaid Match $0 $0 $0 $0

Early Childhood Education Trust

Fund

$5,000,000 $0 $0 $0

Total Revenue

$50,422,394 $45,116,900 $45,116,900 $45,116,900

Projections, Children served

9,839 20,256 23,165 26,168

Projected Expenses amounts

$49,526,657 $92,585,705 $100,276,042 $108,713,168

Table 29: Home Visiting Funding Sources and Revenue projections for direct services by scal year

Table 28: NM PreK Funding Sources and Revenue projections for direct services by scal year

Sources

FY23 Operating

Budget Request

(9/1/21)

FY24

Projection

FY25

Projection

FY26

Projection

General Fund - public preK $43,145,100 $43,145,100 $43,145,100 $43,145,100

General Fund - private preK $32,712,300 $32,712,300 $32,712,300 $32,712,300

TANF - public preK $3,500,000 $3,500,000 $3,500,000 $3,500,000

TANF - private preK $14,100,000 $14,100,000 $14,100,000 $14,100,000

Early Childhood Education Trust

Fund- public

$4,834,600 $2,834,600 $2,834,600 $2,834,600

Early Childhood Education Trust

Fund- private

$10,869,500 $7,765,400 $7,765,400 $7,765,400

Total Revenue

$109,161,500 $104,057,400 $104,057,400 $104,057,400

Projections, Children served

14,633 15,522 16,229 16,418

Projected Expenses amounts

$107,500,540 $112,419,370 $120,667,566 $125,622,136

31

Early Childhood Education and Care Department Four-Year Finance Plan, 2023-2026

Sources

FY23 Operating

Budget Request

(9/1/21)

FY24

Projection

FY25

Projection

FY26

Projection

General Fund $8,758,000 $8,758,000 $8,758,000 $8,758,000