IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF MISSOURI

CENTRAL DIVISION

MARY HOLMES, DENISE DAVIS,

ANDREW DALLAS, and EMPOWER

MISSOURI,

Plaintiffs,

-against-

ROBERT KNODELL, in his official capacity

as Acting Director of the Missouri Department

of Social Services,

Defendant.

No. 2:22-CV-04026

ORAL ARGUMENT

REQUESTED

PLAINTIFFS’ SUGGESTIONS IN SUPPORT OF

MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 1 of 113

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................................................................................... iii

STATEMENT OF MATERIAL FACTS ........................................................................................ a

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT .................................................................................................... 1

PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND................................................................................................. 2

STATUTORY AND REGULATORY BACKGROUND .............................................................. 3

I. SUPPLEMENTAL NUTRITION ASSISTANCE PROGRAM......................................... 3

II. AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT ...................................................................... 4

FACTUAL BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................... 6

I. PLAINTIFF MARY HOLMES .......................................................................................... 6

II. PLAINTIFF DENISE DAVIS ............................................................................................ 7

III. PLAINTIFF ANDREW DALLAS ..................................................................................... 8

IV. PLAINTIFF EMPOWER MISSOURI ............................................................................. 10

V. DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL SERVICES’ OPERATIONS ........................................... 10

LEGAL STANDARDS ................................................................................................................ 16

ARGUMENT ................................................................................................................................ 17

I. DEFENDANT VIOLATES THE SNAP ACT BY WRONGFULLY DENYING

APPLICATIONS FOR FAILURE TO INTERVIEW ...................................................... 17

A. The SNAP Act Requires Defendant to Provide Benefits to All Eligible Applicants

............................................................................................................................... 17

B. Defendant Wrongfully Denied Plaintiffs Holmes’ and Davis’ SNAP Applications

............................................................................................................................... 19

C. The Harm to Plaintiffs Caused by Defendant’s Unlawful Policies and Practices is

Recurring and Ongoing ......................................................................................... 20

II. DEFENDANT VIOLATES THE SNAP ACT BY FAILING TO PERMIT

APPLICATIONS ON THE FIRST DAY OF CONTACT ............................................... 20

A. The SNAP Act Requires Defendant to Allow Missouri Residents the Opportunity

to File a SNAP Application on the First Day They Contact DSS ........................ 20

B. Defendant Blocks Missourians from Filing a SNAP Application on the First Day

They Contact DSS................................................................................................. 21

III. DEFENDANT’S WRONGFUL DENIALS VIOLATE PLAINTIFFS’ DUE PROCESS

RIGHTS ............................................................................................................................ 21

A. Defendant’s Wrongful Denial of Plaintiffs’ SNAP Applications Violates Due

Process .................................................................................................................. 22

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 2 of 113

ii

1. Defendant’s Wrongful Denials of SNAP Applications Violate the

Mathews v. Eldridge Test ......................................................................... 23

2. Defendant’s Standardless Decision-Making Violates Plaintiffs’ Due

Process Rights ........................................................................................... 25

IV. DEFENDANT VIOLATES THE AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT BY

FAILING TO PROVIDE REASONABLE ACCOMMODATIONS ............................... 27

A. Plaintiffs Dallas and Holmes Are Qualified Individuals with Disabilities ........... 30

B. By Failing to Make Reasonable Accommodations, Defendant Prevented

Plaintiffs’ Meaningful Access to SNAP Benefits and Thus Violated the ADA ... 30

C. Defendant Systematically Prevents SNAP Access by Failing to Offer Reasonable

Accommodations .................................................................................................. 32

1. Defendant’s ADA Policy is Inadequate and Ensures DSS’s

Noncompliance with the ADA.................................................................. 32

2. Defendant Fails to Notify SNAP Applicants of Their Rights Under the

ADA .......................................................................................................... 33

3. Defendant’s ADA Policy is Contradicted and Undermined by Agency

Operations ................................................................................................. 34

4. Defendant Violates the ADA Methods-of-Administration Requirements 35

D. Plaintiffs are Entitled to Summary Judgment on Their Fourth Claim for Relief .. 36

V. PLAINTIFFS ARE ENTITLED TO INJUNCTIVE RELIEF .......................................... 37

A. Plaintiffs Will Suffer Continuing and Recurring Irreparable Harm Without an

Injunction, and the Remedies Available at Law are Inadequate Compensation ... 38

B. Balance of Harms Weighs in Favor of Granting the Relief Requested by Plaintiffs

............................................................................................................................... 41

C. Granting Injunctive Relief to Plaintiffs is in the Public Interest ........................... 41

CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................................. 43

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 3 of 113

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Ability Ctr. of Greater Toledo v. City of Sandusky,

385 F.3d 901 (6th Cir. 2004) .............................................................................................28, 29

Action NC v. Strach,

216 F.Supp.3d 597 (M.D.N.C. 2016) ......................................................................................40

Alexander v. Choate,

469 U.S. 287 (1985) .....................................................................................................27, 29, 32

Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc.,

477 U.S. 242 (1986) .................................................................................................................16

Atkins v. Parker,

472 U.S. 115 (1985) .................................................................................................................22

Baker-Chaput v. Cammett,

406 F. Supp. 1134 (D. N.H. 1976) ...........................................................................................25

Barry v. Lyon,

834 F.3d 706 (6th Cir. 2016) ...................................................................................................18

Bliek v. Palmer,

916 F.Supp. 1475 (N.D. Iowa 1996) ..................................................................................23, 25

Bliek v. Palmer,

102 F.3d 1472,1476 (8th Cir. 1997) ........................................................................................23

Booth v. McManaman,

830 F.Supp.2d 1037 (D.Haw. 2011) ................................................................18, 19, 39, 40, 43

Boston Univ. v. Guckenberger,

974 F. Supp. 106 (D. Mass. 1997) ...........................................................................................36

Cafeteria & Rest. Workers Union v. McElroy,

367 U.S. 886 (1961) .................................................................................................................22

Carey v. Quern,

588 F.2d 230 (7th Cir. 1978) ...................................................................................................25

Celotex Corp. v. Catrett,

477 U.S. 317 (1986) .................................................................................................................16

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 4 of 113

iv

Daniels v. Woodbury Cnty., Iowa,

742 F.2d 1128 (8th Cir. 1984) ...........................................................................................22, 23

Daniels v. Woodbury Cnty., Iowa,

625 F. Supp. 855 (N.D.Iowa 1986) ..........................................................................................24

Dataphase Sys. Inc. v. CL Sys., Inc.,

640 F.2d 109 (8th Cir.1981) ....................................................................................................38

District of Columbia v. U.S. Dep’t of Agric.,

444 F. Supp. 3d 1 (D.D.C. 2020) .............................................................................................39

D.M. by Bao Xiong v. Missesote St. High Sch. League,

917 F.3d 994 (8th Cir. 2019) ...................................................................................................43

Dunn v. Dunn,

318 F.R.D. 652 (M.D. Ala. 2016) ............................................................................................35

Gilliam v. United States Dep’t of Agric.,

486 F. Supp. 3d 856 (E.D. Pa. 2020) .......................................................................................43

Glenwood Bridge, Inc. v. City of Minneapolis,

940 F.2d 367 (8th Cir. 1991) ...................................................................................................42

Goldberg v. Kelly,

397 U.S. 254 (1970) ...........................................................................................1, 22, 25, 39, 40

Goyette v. City of Minneapolis,

2021 WL 5003065 (D. Minn. Oct. 28, 2021) ..........................................................................38

Griffeth v. Detrich,

603 F.2d 118 (9th Cir. 1979) ...................................................................................................22

Hall v. Higgins,

2023 WL 5211649 (8th Cir. Aug. 15, 2023)............................................................................27

Hamby v. Neel,

368 F.3d 549 (6th Cir. 2004) ...................................................................................................22

Hannon v. Sanner,

441 F.3d 635 (8th Cir.2006) ....................................................................................................17

Haskins v. Stanton,

621 F.Supp. 622 (N.D. Ind. 1985) .........................................................................18, 21, 39, 41

Haskins v. Stanton,

794 F.2d 1273 (7th Cir. 1986) .....................................................................................19, 41, 43

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 5 of 113

v

Havens Realty v. Coleman,

455 U.S. 363 (1982) .................................................................................................................40

Henrietta D. v. Bloomberg,

331 F.3d 261 (2d Cir. 2003).....................................................................................5, 27, 29, 35

Higgins v. Spellings,

663 F.Supp.2d 788 (W.D. Mo. 2009) ......................................................................................24

Hiltibran v. Levy,

No. 10-4185-CV-C-NKL, 2010 WL 6825306 (W.D. Mo. Dec. 27, 2010) .......................39, 43

Hinojosa v. Livingston,

994 F. Supp. 2d 840 (S.D. Tex. 2014) .....................................................................................29

Holmes v. NYCHA,

398 F.2d 262 (2d Cir. 1968).....................................................................................................26

Isaac v. Louisiana Department of Children and Family Servs,

2015 WL 4078263 (M.D. La. July 6, 2015) ......................................................................27, 28

Islam v. Cuomo,

475 F.Supp. 3d 144 (E.D.N.Y. 2020) ......................................................................................40

Kai v. Ross,

336 F.3d 650 (8th Cir. 2003) ...................................................................................................39

Kapps v. Wing,

404 F.3d 105 (2d Cir. 2005).....................................................................................................22

Kildare v. Saenz, 325 F.3d 1078 (9th Cir. 2003); ..........................................................................41

Kiman v. N.H. Dep’t of Corr.,

451 F.3d 274 (1st Cir. 2006) ....................................................................................................29

K.W. ex rel. D.W. v. Armstrong,

1:12-cv-00022-BLW-CWD, 2023 WL 5431801 (D. Idaho Aug. 23, 2023) ...........................25

Layton v. Elder,

143 F.3d 469 (8th Cir. 1998) .......................................................................................27, 38, 43

League of Women Voters of Missouri v. Ashcroft,

336 F.Supp.3d 998 (W.D. Mo. 2018) ................................................................................40, 41

Loye v. Cnty. of Dakota,

625 F.3d 494 (8th Cir. 2010) ...................................................................................................27

M.A. v. Norwood,

133 F. Supp. 3d 1093 (N.D. Ill. 2015) .....................................................................................25

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 6 of 113

vi

Mallette v. Arlington Cnty. Emps.’ Supp. Ret. Sys. II, 91 F.3d 630, 535 (4th Cir.

1996) ........................................................................................................................................22

Mathews v. Eldridge,

424 U.S. 319 (1976) .....................................................................................................23, 24, 42

Mayer v. Wing,

922 F. Supp. 902 (S.D.N.Y. 1996) ..........................................................................................25

McElwee v. County of Orange,

700 F.3d 635 (2d Cir. 2012).......................................................................................................5

M.K.B. v. Eggleston,

445 F.Supp.2d 400 (S.D.N.Y. 2006)........................................................................................18

Morrissey v. Brewer,

408 U.S. 471 (1972) .................................................................................................................22

NAACP v. USPS,

496 F.Supp.3d 1 (D.D.C. 2020) ...............................................................................................40

Oglala Sioux Tribe v. C&W Enterprises, Inc.,

542 F.3d 224 (8th Cir. 2008) ...................................................................................................37

Peebles v. Potter,

354 F.3d 761 (8th Cir. 2004) .....................................................................................................5

Phelps-Roper v. Nixon,

545 F.3d 685 (8th Cir. 2008) ...................................................................................................43

Phelps-Roper v. City of Manchester, 697 F.3d 678 (8th Cir. 2012) ..............................................43

Pickett v. Tex. Tech. Univ. Health Scis. Ctr.,

37 F.4th 1013 (5th Cir. 2022) ..................................................................................................29

Pierce v. Dist. of Columbia,

128 F. Supp. 3d 250 (D.D.C. 2015) .........................................................................................28

Randolph v. Rodgers,

170 F.3d 850 (8th Cir. 1999) ...................................................................................................27

Reynolds v. Giuliani,

35 F.Supp.2d 331 (SDNY 1999) .............................................................................................18

Ricci v. DeStefano,

557 U.S. 557 (2009) .................................................................................................................16

Richland/Wilkin Joint Powers Auth. v. U.S. Army Corps of Eng’rs,

826 F.3d 1030 (8th Cir. 2016) .................................................................................................38

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 7 of 113

vii

Robertson v. Jackson,

972 F.2d 529 (4th Cir. 1992) ...................................................................................................17

Robertson v. Jackson,

766 F.Supp. 470 (E.D.Va 1991) ..............................................................................................21

Robertson v. Las Animas Cnty. Sheriff’s Dep’t,

500 F.3d 1185 (10th Cir. 2007) ...............................................................................................29

Rogers Grp., Inc. v. City of Fayetteville,

629 F.3d 784 (8th Cir. 2010) ...................................................................................................38

Scott v. Harris,

550 U.S. 372 (2007) .................................................................................................................16

Segal v. Metro. Council,

29 F.4th 399 (8th Cir. 2022) ..............................................................................................27, 31

Smith v. Goguen,

415 U.S. 566 (1974) .................................................................................................................25

Southside Welfare Rights Org. v. Stangler,

156 F.R.D. 187 (W.D. Mo. 1993) ..........................................................................18, 19, 21, 39

Strouchler v. Shah,

891 F.Supp. 2d 504 (S.D.N.Y. 2012).......................................................................................25

Tellis v. LeBlanc,

No. 18-541, 2022 WL 67572 (W.D. La. Jan. 6, 2022) ............................................................35

Torres v. Butz,

397 F. Supp. 1015 (N.D. Ill. 1975) ..........................................................................................26

Vote Forward v. DeJoy,

490 F.Supp.3d 110 (D.D.C. 2020) ...........................................................................................40

White v. Roughton,

530 F.2d 750 (7th Cir. 1976) ...................................................................................................25

White v. Martin,

No. 02-4154-CV-C-NKL, 2002 WL 34560467 (W.D. Mo. July 26, 2002) ............................42

Winter v. NRDC, Inc.,

555 U.S. 7 (2008) .....................................................................................................................40

Withrow v. Concannon,

942 F2d 1385 (9th Cir. 1991) ..................................................................................................19

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 8 of 113

viii

STATUTES AND REGULATIONS

7 U.S.C. § 2011 ....................................................................................................................3, 36, 42

7 U.S.C. § 2014 ..............................................................................................................................26

7 U.S.C. § 2014(a) ...............................................................................................................3, 17, 18

7 USC 2014(b) ...............................................................................................................................18

7 USC § 2017 (c)(1) .........................................................................................................................7

7 U.S.C. § 2020(a), (d), (e) ............................................................................................................17

7 U.S.C. § 2020(e)(2)(B) ...........................................................................................................3, 17

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ............................................................................................................................17

42 U.S.C. § 12101(a)(3) ...................................................................................................................4

42 U.S.C. § 12101(b)(1) ................................................................................................................42

42 U.S.C. § 12101(b)(1), (2) ............................................................................................................4

42 U.S.C. § 12102(1) .................................................................................................................5, 30

42 U.S.C. § 12112(b)(5)(A) .....................................................................................................27, 32

42 U.S.C. § 12131(2) .....................................................................................................5, 29, 30, 32

42 U.S.C. § 12131(1)(A), (B) ..........................................................................................................5

42 U.S.C. §§ 12131–12134 ............................................................................................................17

7 C.F.R. § 271.1 .............................................................................................................................36

7 C.F.R. § 271.2 ...............................................................................................................................3

7 C.F.R. § 273.2(c)(1), (2)(i) ...........................................................................................................3

7 C.F.R. §§ 273.3–273.11 ..............................................................................................................26

7 CFR § 273.10 (a)(ii) ................................................................................................................7, 15

7 C.F.R. § 273.12 .............................................................................................................................4

7 C.F.R. § 273.14 .............................................................................................................................3

7 C.F.R. § 277.1(b) ..........................................................................................................................3

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 9 of 113

ix

7 C.F.R. § 277.4 ...............................................................................................................................3

20 C.F.R. §404.1505 ........................................................................................................................6

28 C.F.R. § 35.104 ...........................................................................................................................5

28 C.F.R. § 35.106 .........................................................................................................................28

28 C.F.R. § 35.107 .........................................................................................................................28

28 C.F.R. § 35.130(b)(3) ..........................................................................................................28, 35

28 C.F.R. § 35.130(b)(7)(i) ......................................................................................5, 27, 28, 31, 32

28 C.F.R. § 35.130(b)(8) ................................................................................................................36

MO. REV. STAT. § 205.960, et seq. .................................................................................................17

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Fed. R. Civ. P. 56(a) .....................................................................................................................16

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 10 of 113

a

STATEMENT OF MATERIAL FACTS

Department of Social Services

1. Missouri’s Department of Social Services (DSS) is the single state agency

responsible for administering the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) in

Missouri. ECF 93 ¶ 28.

2. Robert Knodell is the Department Director of the Missouri Department of Social

Services. ECF 93 ¶ 22.

3. The Family Support Division (FSD) of DSS assesses the eligibility of SNAP

applicants and disburses benefits to eligible households. ECF 19-1 ¶ 3.

4. Kim Evans is the Division Director of the Family Support Division. Ex. 1,

Excerpts from Evans Dep. at 14:10–12.

5. Within FSD, there are three types of offices that assist with the administration of

SNAP benefits. These are Processing Centers, Resource Centers, and Customer Service Centers.

Ex. 2, Excerpts from 30b6 Wolf Dep. at 22:20–24:16.

6. Generally, workers in Processing Centers process SNAP applications to determine

eligibility. These workers process applications, process verifications, answer phone calls when

needed, and assist Resource Centers when needed. Ex. 2 at 23:21–24:1, 184:10–17.

7. There are approximately 1100 employees that work in the Processing Centers. Ex.

2 at 183:25–184:9.

8. Generally, workers in Resource Centers assist individuals who visit the Resource

Centers in person. These workers assist individuals with verifications, answering general

questions, providing additional resources, and registering applications. Ex. 2 at 22:20–23:7,

182:15–25.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 11 of 113

b

9. There are “just under 400 employees” that work in the Resource Centers. Ex. 2 at

182:8–14.

10. Generally, workers in Customer Service Centers (CSCs) answer calls for the DSS

call center. These workers answer general questions, complete interviews, process cases after the

interview is complete, and inform callers of possible resources. Ex. 2 at 23:8–13, 183:16–24.

11. Between 200 and 300 employees work in the Customer Service Centers. Ex. 2 at

183:1–4; Ex. 3, Excerpts from Conway Dep. at 59:10–18.

12. Across the Processing Centers, Resource Centers, and Customer Service Centers,

there are about 1800 employees. Ex. 2 at 183:25–184:9.

13. All three types of offices are staffed with Benefit Program Technicians (BPTs)

and Customer Information Specialists (CISs) who have the same training and are able to perform

the same tasks. Ex. 2 at 25:4–13; Ex. 4, Excerpts from Comer Dep. at 19:19–22:4, 24:15–22,

31:13–17.

14. Workers in any of the three offices are generally capable and qualified to do the

tasks of workers in the other offices. Ex. 2 at 25:4–26:3.

15. To receive SNAP benefits, an individual must submit an initial application. To

maintain eligibility, an individual must submit a recertification.

1

See 7 U.S.C. § 2014(a).

16. DSS policy stipulates that applicants to the SNAP program can access an

application online, by mail, in person at a Resource Center, or at some DSS community partner

locations. Ex. 2 at 214:1–8.

1

The term “applicant” is used throughout this Statement to refer to an individual who has submitted an initial

application or recertification. Initial applications and recertifications are referred to generally throughout this

statement as applications. “Recipient” is used to refer to an individual currently receiving benefits.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 12 of 113

c

17. Resource Centers are expected to make applications available in their lobby. Ex.

5, Excerpts from Smith Dep. at 91:10–92:14; Ex. 6, DEF 0146826.

18. The United States Department of Agriculture’s Food and Nutrition Service (FNS)

does not permit DSS to accept a SNAP application over the phone, (Ex. 2 at 214:9–11), but

individuals can request that call center staff mail them a SNAP application. Ex. 2 at 214:16–18.

19. However, there is no automated option in Defendant’s Interactive Voice Response

(IVR) system to request that an application be sent out. Ex. 7, DEF 0137450; Ex. 8, DEF

0137416.

20. Once an application is registered, DSS sends a notice to the applicant or recipient,

letting them know they have to complete an interview. See Ex. 9, DEF 28048

2

; see also facts in

“On-Demand Waiver” section, infra.

21. DSS’s eligibility system automatically denies applications where an interview has

not been completed within 30 days, regardless of whether applicants and recipients attempted to

secure an interview, or whether DSS meaningfully made an interview available. Ex. 2 at 239:7–

22.

On-Demand Waiver

22. DSS has a waiver from FNS that allows DSS to use an interview procedure that

deviates from the process laid out in FNS regulations. This is called the On-Demand Waiver. Ex.

9.

23. Pursuant to the waiver, DSS is not required to schedule the SNAP interview at a

specific date and time. Instead, DSS must provide applicant households with a notice, known as

2

Defendant has agreed to withdraw all previously made confidentiality designations for the documents utilized in

support of Plaintiffs’ Motion for Summary Judgment. Plaintiffs have redacted personal identifying information

where appropriate.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 13 of 113

d

an interview letter, instructing them to call the call center within five days of submitting their

application. Ex. 9.

24. Also pursuant to the waiver, applicants who do not complete their interview

within five days are sent a Notice of Missed Interview (NOMI), also known as a missed

interview letter, instructing them that they must complete their interview within 30 days of

submitting their application, or their application will be denied. Ex. 9.

25. Pursuant to Missouri’s waiver, “[a]pplicants are able to have a face-to-face

interview at the time of application or upon request for any reason.” Applicants who request a

face-to-face interview must have an appointment scheduled within five days. Ex. 9.

26. Also pursuant to Missouri’s waiver, “DSS has implemented predictive dialing for

the call centers, which attempts contact with clients on the first day for all applications” and

“attempts [to call] for 4 days.” Ex. 9.

27. When deciding whether to reapply for the waiver, DSS made no formal

evaluation of how the previous waiver term had gone. Ex. 1 at 133:20–22.

Plaintiff Mary Holmes

28. Ms. Holmes has throat cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

(COPD). ECF 6-1 ¶ 3.

29. Ms. Holmes’ COPD makes it difficult for her to leave her home. She often has to

be admitted to the hospital due to her COPD. ECF 6-1 ¶ 4.

30. The symptoms related to Ms. Holmes’ cancer make it difficult and uncomfortable

for her to speak. ECF 6-1 ¶ 5.

31. Because of her health conditions, Ms. Holmes is at a high risk for complications

from COVID-19. ECF 6-1 ¶ 9.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 14 of 113

e

32. In late 2021, Ms. Holmes was hospitalized for roughly three and a half weeks

with COVID-19 and pneumonia. ECF 6-1 ¶ 9.

33. Ms. Holmes’ receives monthly Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits.

ECF 18 ¶ 3, ECF 18-1.

34. Ms. Holmes does not have Internet access at home, nor does she have any reliable

means of transportation. ECF 6-1 ¶¶ 7, 8.

35. Because of her disabilities, Ms. Holmes must be able to complete required SNAP

tasks by phone without waiting on hold for an extended period of time, and if she must go to a

Resource Center, then she needs to be able to complete her SNAP interview that same day. Ex.

10, M. Holmes Interrogatory Response.

36. In December 2021, DSS mailed Ms. Holmes’ SNAP recertification paperwork to

an old address. She lost SNAP benefits because she did not receive this notice, and needed to

submit a new application. ECF 6-1 ¶ 12.

37. In January 2022, Ms. Holmes attempted to call DSS’s call center to request an

application for SNAP. She called three times during the first week of January, but she was never

given an opportunity to request an application form. ECF 6-1 ¶¶ 13–14; Ex. 11, DEF 0139752.

38. Because she was unable to request an application by phone, Ms. Holmes paid a

family member to take her to the Chouteau Resource Center on January 10, 2022. She waited in

line for 20 minutes before speaking to an employee. ECF 6-1 ¶¶ 15, 19.

39. She filled out an application at the Resource Center and submitted it. ECF 6-1 ¶¶

17, 20.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 15 of 113

f

40. After submitting the application, Ms. Holmes asked to be interviewed in person

and was told that the Resource Center staff were not doing interviews. A worker told Ms. Holmes

someone from DSS would call her within the next few days. ECF 6-1 ¶ 21.

41. DSS registered Ms. Holmes’ application on January 11, 2022. ECF 19-1 ¶ 15; Ex.

11.

42. On January 12, 2022, Ms. Holmes answered a call from DSS. ECF 19-1 ¶ 15;

ECF 88 ¶ 185; ECF 93 ¶ 185. She was never connected to a representative. ECF 6-1 ¶ 25.

43. The next day, January 13, 2022, Ms. Holmes called the call center at 8:08 AM.

She was asked a series of automated questions by the IVR prompts. After answering the

questions, she entered the queue and was told that there were 472 people in front of her. She

waited for two hours but was never connected to a representative. ECF 6-1 ¶¶ 26–27; Ex. 11.

44. She called again at 10:10 AM and stayed in the queue for 6 minutes and 12

seconds before disconnecting. Ex. 11.

45. She tried to call again at 2:04 PM, 3:42 PM, 3:44 PM, and 3:46 PM, and each

time was unable to even enter the queue because her call was deflected.

3

Ex. 11.

46. Ms. Holmes called again on January 14, 2022, at 7:53 AM. She once again

answered the IVR prompts. She was told there were 692 people in front of her in the queue. She

waited for an hour and 37 minutes but was never connected to a representative. ECF 6-1 ¶ 28; Ex.

11.

47. Ms. Holmes called again on January 27, 2022, at 4:30 PM and was deflected. Ex.

11.

3

DSS calls this process of rejecting calls from the queue due to capacity issues “deflecting” calls. As discussed

infra, when a call is deflected, the caller hears an automated recording informing them that the call center is not

taking calls, their other options of contacting DSS, and the call is disconnected.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 16 of 113

g

48. She called again on January 28, 2022 at 9:36 AM and stayed in the queue for 14

minutes and 12 seconds before disconnecting. Ex. 11.

49. During the first week of February, Ms. Holmes received a notice from DSS titled

“Interview Required to Process Your Application.” The notice said she needed to complete her

SNAP interview, that DSS would attempt to reach her, that she should call DSS between 6:00

AM and 5:30 PM if she missed her call, and that her application would be denied if she did not

complete the interview. ECF 6-1 ¶¶ 29–30; Ex. 12, DEF 0140076 at 0140104.

50. Ms. Holmes did not receive any calls from DSS after receiving that notice. ECF

6-1 ¶ 31.

51. Ms. Holmes tried to call multiple times early in February 2022. ECF 6-1 ¶ 32.

During her attempt at 1:10 PM on February 4, the call was deflected. At 2:37 PM, her call was

again deflected. Ex. 11.

52. During the week of February 7, 2022, Ms. Holmes received a notice that her

SNAP application was denied for failure to complete her interview. ECF 6-1 ¶ 33; ECF 18-3.

53. On February 10, 2022, Ms. Holmes attempted to call DSS one more time. She

once again answered the IVR prompts, and was told there were 468 people ahead of her in the

queue. ECF 6-1 ¶¶ 34–35. She called at 7:32 AM and waited for 18 minutes and 40 seconds

before disconnecting. She called again at 8:48 AM and waited 32 minutes and 27 seconds before

disconnecting. Ex. 11.

54. After this litigation was filed, Ms. Holmes received an interview and was

approved for SNAP benefits from the date of that interview forward. Ex. 13, DEF 0142129 at

0142181–84, 0142195–201, 0142209.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 17 of 113

h

55. Ms. Holmes seeks but has not been approved for benefits from the date of her

application on January 10, 2022 through March 20, 2023. See ECF 47-1 – Ex. A at 5:7–13; Ex.

14, MO SNAP 0004279.

56. Ms. Holmes will continue to rely on SNAP for the foreseeable future. ECF 6-1 ¶¶

3–6.

57. Ms. Holmes will have to reapply for SNAP in February 2024 and every two years

thereafter. See Ex. 13 at 0142181.

58. Despite Ms. Holmes being a plaintiff in this litigation, she has continued to

struggle to maintain her SNAP eligibility due to agency dysfunction. Ex. 15, DEF 0142083; Ex.

16, DEF 0141934.

Plaintiff Andrew Dallas

59. Mr. Dallas has epilepsy which causes him to have frequent seizures. Ex. 17,

Dallas Decl. ¶ 2.

60. Many things in Mr. Dallas’ day-to-day life can cause seizures including stress, a

poor diet, skipping meals, and not getting enough sleep. Ex. 17 ¶ 3.

61. He has one seizure per week on average. When he is feeling stressed, he has

seizures more frequently, sometimes as many as three per week. Ex. 17 ¶ 2.

62. As a result of his seizures, Mr. Dallas often feels confused. His seizures cause

“brain fog” which causes him to lose track of what he is doing and forget what he is talking

about in the middle of a conversation. Ex. 17 ¶ 4.

63. Mr. Dallas’ brain fog has worsened over time and doctors have not been able to

effectively treat it. Ex. 17 ¶ 4.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 18 of 113

i

64. Medicaid approved Mr. Dallas for 21 hours per week of home health services.

These services include house cleaning, grocery shopping, meal preparation, and transportation.

Ex. 17 ¶ 5.

65. Mr. Dallas’ only income is Supplemental Security Income (SSI). Ex. 17 ¶ 6.

66. Mr. Dallas’ epilepsy makes it difficult for him to leave his house because he has

trouble walking and is a fall risk. Ex. 17 ¶ 13.

67. Mr. Dallas is not able to drive because of his epilepsy. Ex. 17 ¶ 7.

68. Because of his disabilities, Mr. Dallas struggles to complete required SNAP

paperwork. Ex. 17 ¶ 9.

69. Mr. Dallas finds SNAP recertification paperwork complicated and confusing. The

paperwork uses terms that he does not understand. Ex. 17 ¶ 9.

70. On December 23, 2021, DSS received a document from Mr. Dallas entitled “Food

Stamp Change Report.” Ex. 18, Excerpts from 30b6 Wise Dep. at 71:4–72:10; Ex. 19, Excerpt

from DEF 0137942 (presented as Ex. 4 in 30b6 Wise Dep.) at 0138026.

71. On the report, Mr. Dallas wrote: “I have epilepsi [sic] + cannot understand like

normal people do. Please help! I am not sure I understand all of the letter. I am disabled.” Ex. 19

at 0138027.

72. DSS understands this written note to be a reasonable accommodation request. Ex.

18 at 72:4–10.

73. DSS policy does not dictate that anyone follow up with Mr. Dallas on this request

for help if the submitted form was complete. Ex. 18 at 73:7–24.

74. On February 4, 2022, DSS received a document from Mr. Dallas entitled “Food

Stamp Mid Certification Review/Report Form.” Ex. 19 at 0138028–37.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 19 of 113

j

75. On the report, Mr. Dallas wrote: “I am an Epileptic. I hope I got everything right.

Thanks, Andrew Dallas.” Ex. 19 at 0138037.

76. DSS admitted it would be considered a best practice for DSS to follow up with

Mr. Dallas when he requested help, but DSS policy does not require it. Ex. 18 at 75:2–6.

77. In January 2023, DSS mailed Mr. Dallas SNAP recertification paperwork. The

notice stated that if he did not complete the paperwork by February 28, 2023, his SNAP benefits

would end. Mr. Dallas does not feel confident completing SNAP paperwork without assistance.

Ex. 17 ¶ 9.

78. Despite Mr. Dallas’ previous attempts to inform DSS of his disability and need

for a reasonable accommodation, he was not affirmatively offered assistance with his

recertification application.

79. On or about February 8th through February 10th, Mr. Dallas called DSS’s

information line about ten times. At least three times, he was not able to make it past the main

menu’s language prompts. He was told to press “1” for English, but after pressing “1” the

instructions would repeat. After pressing “1” again, the call disconnected. Ex. 20, DEF 0138504;

Ex. 17 ¶ 11.

80. Once, on or about February 8th through February 10th, Mr. Dallas called DSS’s

information line and made it past the main menu. He was put on hold and told there were 234

callers ahead of him. He decided to hang up after waiting for a few minutes. Ex. 20; Ex. 17 ¶ 11.

81. Mr. Dallas needed someone to help him complete his recertification form by

talking to him over the phone and explaining how he should answer the questions he finds

confusing. He was not able to get through the phone system to ask for this help. He does not

know any other way to ask DSS for help with his paperwork. Ex. 17 ¶ 13.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 20 of 113

k

82. In the past, Mr. Dallas has used Legal Services of Eastern Missouri to get

assistance with his paperwork. He called them in 2022 for help and was able to recertify. He

would not have been able to successfully recertify without his advocate’s help. Ex. 17 ¶ 14.

83. Under current DSS policies, Mr. Dallas will need to make another reasonable

accommodation request each and every time he needs assistance with SNAP paperwork. Ex. 18

at 92:11–24.

84. After joining as a plaintiff in this lawsuit, Mr. Dallas received an interview and

was approved for SNAP benefits. Ex. 21, DEF 0141293.

85. Mr. Dallas will continue to rely on SNAP for the foreseeable future. Ex. 17 ¶ 6.

86. To maintain SNAP eligibility, Mr. Dallas will have to continue to interact with

DSS including to respond to requests for mid-certification and to reapply. Ex. 21.

Plaintiff Denise Davis

87. Denise Davis first applied for SNAP on November 12, 2022. Ex. 22, DEF

0138108 at 0138108–15. She submitted her application online. She never received any follow-up

communication from DSS about her application. When she called the call center, she was

informed that there was no application registered under her Social Security Number (SSN), and

that she should reapply. Ex. 23, Davis Decl. ¶ 9.

88. On December 29, 2022, Ms. Davis submitted a second online SNAP application.

Ex. 22 at 0138116–23. She was subsequently hospitalized with acute kidney failure for two

weeks and did not have access to her phone. When she was released from the hospital, she called

the call center multiple times each week in order to complete her SNAP interview. Ex. 23 ¶ 10;

Ex. 24, DEF 0138512.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 21 of 113

l

89. Ms. Davis called the call center on January 4, 2023 at 1:12 PM and at 2:10 PM.

Both times her calls were deflected. Ex. 24; Ex. 25, Excerpts from Sneller Dep. at 140:25–

144:15.

90. On January 10, 2023, Ms. Davis called the SNAP interview line at 3:36 PM and

was deflected. At 3:39 PM she called the general information line and made it into the queue, but

subsequently the call was disconnected.

4

Ex. 24.

91. On January 12, 2023, Ms. Davis called the SNAP interview line at 10:08 AM. She

waited in the queue for one hour and 52 minutes before disconnecting. She called again at 12:11

PM, 12:13 PM, and 12:16 PM and was deflected each time. She also attempted to call the

general information line at 12:18 PM and was deflected there too. She called the SNAP interview

line again at 12:26 PM and was able to connect to the IVR flow, but was not able to speak

directly to anyone. Ex. 24; Ex. 25 at 140:25–144:15.

92. On January 13, 2023, Ms. Davis called the general information line at 4:03 PM,

and the SNAP interview line at 4:21 PM and was deflected both times. Ex. 24; Ex. 25 at 140:25–

144:15.

93. Each time that Ms. Davis called and was able to enter the queue, there were

hundreds of people ahead of her. On more than one occasion, there were more than 700 people in

the queue. Ex. 23 ¶¶ 10–11.

94. On more than one occasion, Ms. Davis waited between two and three hours until

fewer than 100 people were ahead of her in the queue, at which point she heard a recording that

4

The SNAP interview line and general information line are two different phone numbers. The SNAP interview line

is advertised as the number to call to complete a SNAP interview, and the general information line is advertised as

the line to call for all other inquiries. Ultimately, both lines can route a caller into the appropriate queue to complete

an interview. The mechanics of how these lines work is discussed infra in the “Call Center” section.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 22 of 113

m

DSS was receiving too many calls and she should call back later. At that point the call was

terminated by the call center system. Ex. 23 ¶¶ 10–11.

95. In early January 2023, Ms. Davis received a letter from DSS stating she needed to

complete an interview in order for her application to be processed. Ex. 23 ¶ 12; Ex. 26, MO

SNAP 0000035.

96. Shortly afterwards, she received another notice stating that if she did not complete

an interview by January 30, 2023, her application would be denied. Ex. 23 ¶ 13; Ex. 27, DEF

0138054 at 0138088.

97. Despite multiple attempts through the call center, Ms. Davis was not able to

complete her interview and her second application was denied. Ex. 23 ¶ 17; Ex. 27 at 0138076.

98. Ms. Davis submitted a third application for SNAP on January 30, 2023. Ex. 23 ¶

18; Ex. 22 at 0138126–33.

99. Ms. Davis slept with her phone next to her on full volume in order to ensure she

would hear any early morning calls from DSS. Ex. 23 ¶ 14.

100. On February 1, 2023, at 8:22 AM, Ms. Davis received a call from DSS. She

picked up the phone and was informed she was in a queue behind 17 other people. Ex. 23 ¶ 14;

Ex. 24.

101. When Ms. Davis was connected to a DSS worker, the worker requested her case

number. Ms. Davis did not know her case number and provided her SSN instead. The DSS

worker accepted this information, but then hung up on Ms. Davis. Ex. 23 ¶ 14.

102. The call records for this interaction show that Ms. Davis did connect to a worker

but that the total interaction time was 5 minutes and 52 seconds. Ex. 24.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 23 of 113

n

103. Ms. Davis called back immediately at 8:30 AM but heard a recording that 300

people were waiting ahead of her in line. She called again at 8:38 AM and waited for an hour and

58 minutes before disconnecting. She called again at 10:44 AM and waited for 6 minutes and 30

seconds before disconnecting. Ex. 23 ¶ 14; Ex. 24.

104. Ms. Davis received another call from DSS on February 2, 2023 at 7:04 AM, but it

went to voicemail. She called back at 8:16 AM and waited on the queue for an hour and 58

minutes before disconnecting. Ex. 24.

105. She received another call on February 3, 2023 at 7:00 AM, but it went to

voicemail. She called at 9:34 AM and 9:38 AM but disconnected shortly after getting into the

queue. Ex. 24.

106. Ms. Davis called her local DSS office in Rolla, Missouri to set up an appointment

for an in-person interview. She was automatically transferred to the call center and was put on

hold again. Ex. 23 ¶ 15.

107. Ms. Davis also attempted to use the DSSChat feature on Defendant’s website

twice to complete her interview.

5

Each time, the Chat directed her to the call center. Ex. 23 ¶ 16.

108. Despite multiple attempts through the call center and a visit to the Resource

Center, Ms. Davis was not able to complete her interview. Ex. 23 ¶ 21.

109. Ms. Davis attempted to be interviewed via the call center approximately 15 times

after submitting her third SNAP application. Ms. Davis was never able to connect to a DSS

worker. Ex. 23 ¶ 18.

5

DSSChat is a chat platform available on DSS’s website. DSSChat is discussed infra in the “Appointment

Scheduler” section.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 24 of 113

o

110. In early February, Ms. Davis received a letter from DSS dated February 1, 2023,

stating that she needed to complete an interview for her application to be processed. Ex. 23 ¶ 19;

Ex. 27 at 0138082.

111. A few days later, she received a notice dated February 7, 2023, stating that if she

did not complete an interview by March 1, 2023, her SNAP application would be denied. Ex. 23

¶ 20; Ex. 27 at 0138084.

112. After joining as a plaintiff in this lawsuit, Ms. Davis received an interview and

was approved for SNAP benefits. Ex. 28, MO SNAP 0004110.

113. Ms. Davis will continue to rely on SNAP for the foreseeable future. Ex. 23 ¶ 3.

114. Ms. Davis will have to reapply for SNAP in December 2023 and every year

thereafter. Ex. 28.

Plaintiff Empower Missouri

115. Empower Missouri devotes significant time, energy, and resources to issues

arising from DSS’s administration of SNAP in Missouri. See Ex. 29, Empower Interrogatory

Response ¶¶ 5, 15–16.

116. Empower Missouri is a founding member of the SNAP Advisory Group, which

formed in 2021 in response to DSS’s failure to properly administer SNAP. Starting in January

2022, the Advisory Group held monthly calls with the Family Support Division of DSS

regarding SNAP-specific issues. On these calls, Empower Missouri advocated for policies and

practices to improve access to SNAP and other benefits. DSS no longer attends these meetings.

Ex. 29 ¶ 4.

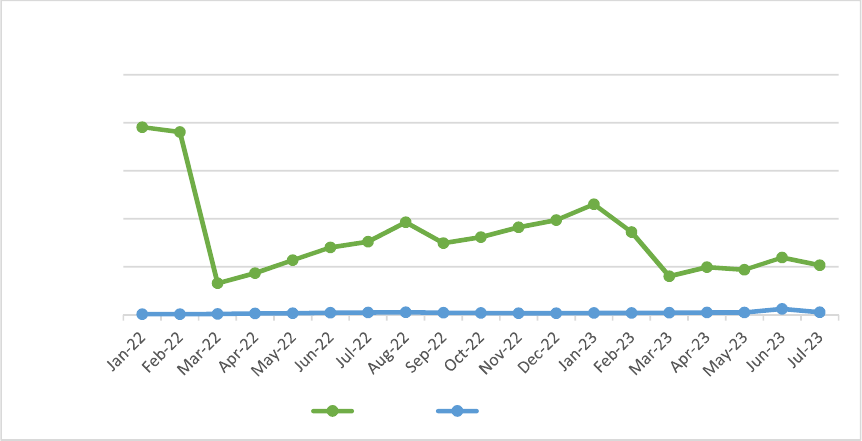

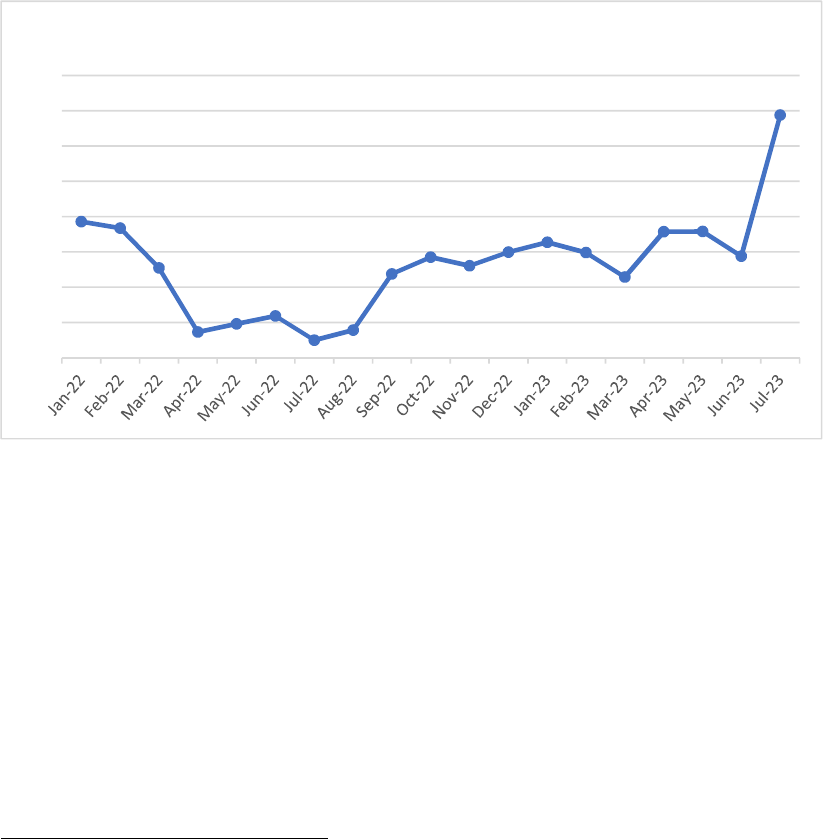

117. The SNAP Advisory Group dedicates a portion of its meetings to reviewing DSS

call center data regarding the extensive wait time and deflection issues. Ex. 29 ¶ 5.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 25 of 113

p

118. Empower Missouri also convenes the Food Security Coalition (FSC), a group of

anti-hunger advocates and providers in Missouri. Through the FSC, Empower Missouri provides

resources and information to anti-hunger advocates and providers, and communicates with DSS

regarding agency failures in Missouri’s administration of SNAP. Most members of the FSC are

direct service providers including food banks and anti-homelessness organizations. See, e.g., Ex.

30, MO SNAP 00004121; Ex. 31, MO SNAP 00004136; Ex. 32, MO SNAP 00004139; Ex. 33,

MO SNAP 00004154.

119. Empower Missouri uses such meetings to communicate concerns with DSS about

call center wait times. Ex. 29 ¶ 5.

120. Because of the numerous problems with DSS’s administration of SNAP in

Missouri, Empower Missouri staff divert considerable time and effort organizing and managing

the FSC. Ex. 29 ¶¶ 5, 16.

121. Empower Missouri’s Food Security Coalition budget for fiscal year 2023 was

$161,020.64. Ex. 34, MO SNAP 0000001.

122. Empower Missouri has spent $96,000 for fiscal years 2021, 2022, and 2023

relating to issues arising from DSS’s administration of SNAP. Ex. 29 ¶ 15.

123. Empower Missouri’s Food Security Policy Manager has diverted roughly twenty

percent of her time because of issues arising from DSS’s administration of SNAP. Ex. 29 ¶ 16.

124. Both Empower Missouri’s Executive Director and Policy Director have diverted

roughly ten percent of their time because of issues arising from DSS’s administration of SNAP.

Ex. 29 ¶ 16.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 26 of 113

q

125. Empower Missouri has diverted staff time from proactive policy reform efforts

regarding school meals, WIC, and seniors’ access to SNAP to respond to issues created by

DSS’s administration of SNAP. Ex. 29 ¶ 16.

Uncontroverted Facts Evidencing Systemic Dysfunction

126. Defendant’s failed call center has stopped other SNAP applicants from

completing their interview. Ex. 35, Matousek Decl. ¶¶ 13–14; Ex. 36, Dodd Decl. ¶¶ 9–11; Ex.

37, Wall Decl. ¶¶ 9, 12–14; Ex. 38, Dempsey Decl. ¶¶ 7–9; Ex. 39, Underwood Decl. ¶¶ 10–12.

127. Patricia Matousek attempted to complete her interview in the beginning of 2022.

Between the end of December 2021 and May 2022, Ms. Matousek called DSS at least once a

week, in total between 10-20 times. Ex. 35 ¶ 11.

128. Most of the times Ms. Matousek called, the call was deflected. Ex. 35 ¶ 13.

129. Every time she made it past the IVR prompts and into the interview queue, there

were hundreds of people in the queue ahead of her. Ex. 35 ¶ 14.

130. Ms. Matousek submitted three applications for SNAP and was denied each time

for failure to interview. Ex. 35 ¶¶ 7, 9, 10.

131. Elizabeth Dodd attempted to complete her interview in November and December

2021. She called numerous times and routinely was on hold for hours. Multiple times after

waiting on hold for hours, her call was disconnected. Ex. 36 ¶¶ 9–12.

132. In January 2022, Shelby Wall tried to call the call center over ten times and was

never able to connect to someone to do the interview. Ex. 37 ¶ 7–14.

133. Victoria Dempsey, the Program Director of the Youth and Family Advocacy

Program at Legal Services of Eastern Missouri, called the interview line on behalf of her client at

various times of day over the course of multiple days in April 2023. When she was able to get

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 27 of 113

r

into the queue, there were always at least 50 callers ahead of her. Otherwise, she was directed to

go to a Resource Center and the call was disconnected. Ex. 38 ¶¶ 2, 7–9.

134. Daniel Underwood, the Managing Attorney of the Youth and Family Advocacy

Program at Legal Services of Eastern Missouri, called the interview line on behalf of his clients

on August 17, 2023. He was told he was 150th in the queue and waited for 90 minutes before the

call center disconnected him. He called again that afternoon but was deflected. On August 18,

2023, he called again and was told he was 225th in the queue. He waited for about 30-40 minutes

before he disconnected. Ex. 39 ¶¶ 3, 10 – 12.

135. Other applicants have been turned away at their local Resource Centers when they

attempted to complete a SNAP interview there. Ex. 40, Spates Decl. ¶¶ 6–7; ECF 6-1 ¶ 21.

136. Patriona Spates, the Intrada Coordinator at Epworth Children & Family Services,

accompanied a client to the Resource Center to assist them in completing an interview. The staff

at the Resource Center told Ms. Spates and her client that they were unable to do an interview

because of staffing problems. The staff told Ms. Spates’ client to return the next day, but did not

offer an appointment. Ex. 40 ¶¶ 2, 6–7.

137. SNAP participants with disabilities request accommodations and do not reliably

receive them. Ex. 41, Shelton Decl. ¶¶ 15–22; ECF 6-2 ¶¶ 6–12, 31.

138. James Shelton was diagnosed with Type I diabetes in 1994. In 2011 was

diagnosed with diabetic retinopathy, and as a result, his vision is very limited. Ex. 41 ¶¶ 2–4.

139. In the past, Mr. Shelton has had trouble with SNAP paperwork due to his visual

impairment. He has taken documents to the Kirksville Family Support Division Resource Center

to have staff read the documents to him. Ex. 41 ¶ 14.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 28 of 113

s

140. Mr. Shelton uses a screen reader on his phone and has asked the Family Support

Division many times to send notices to him electronically. Ex. 41 ¶¶ 9, 15–16.

141. He has visited his local Resource Center many times over the past four years.

Every time, he has asked them to send SNAP notices in a digital format to accommodate his

vision disability. Ex. 41 ¶¶ 15–16.

142. On June 20, 2023, Mr. Shelton went to the Kirksville Resource Center because his

SNAP benefits had been terminated. He was told that he had not returned his SNAP mid-

certification review form. Ex. 41 ¶ 19.

143. Mr. Shelton told a Resource Center supervisor that DSS is required to send him

SNAP notices in format he can read. The supervisor responded that FSD does not have to do

this. The supervisor also said that FSD’s systems only print documents on paper, so that is the

only way they can send notices. Ex. 41 ¶ 21.

144. Mr. Shelton informed the supervisor that according to the Americans with

Disabilities Act, they have to send materials in a format that he can read. The supervisor reported

that FSD does not have to follow federal law because FSD operates in Missouri, which is not a

federal entity. Ex. 41 ¶ 21.

145. During Mr. Shelton’s conversation with the employee and supervisor at the

Kirksville Resource Center, no accommodations for his visual disability were suggested. Ex. 41

¶ 22.

146. L.V. had to submit a recertification for SNAP in January 2022. ECF 6-2 ¶¶ 14–

15.

147. L.V. could not go to a Resource Center to complete her interview because her

diabetes, trouble breathing, COVID-related heart trouble, extreme fatigue, and migraines, made

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 29 of 113

t

it too difficult to leave her home. ECF 6-2 ¶¶ 6–12. L.V. had no choice but to rely on DSS’s call

center. ECF 6-2 ¶ 31.

148. Despite multiple attempts to complete her interview through the call center in

early 2022, L.V. was not able to speak to an individual to complete her interview. Her

application was denied for failure to complete the interview. ECF 6-2 ¶¶ 20–27, Ex. G.

Call Center

149. There are 10 Customer Service Centers (CSCs). Ex. 4 at 23:24–24:2, Ex. 3 at

22:7–13.

150. CSC staff interact with applicants and recipients by phone, text, and internet chat.

Ex. 3 at 19:15–20:2.

151. The number of staff at each CSC ranges from around 12–15 to around 40–45. Ex.

4 at 24:3–6.

152. Staff at CSCs answer call center calls statewide. Ex. 4 at 64:12–20.

153. The phone system that DSS uses in the call center is called Genesys. Ex. 2 at

96:5–7.

154. The DSS call center switched to the Genesys phone system in June 2021. Ex. 42,

Def. Response to 2nd Rog ¶ 8; Ex. 43, DEF 45998; Ex. 2 at 118:15–18.

155. Prior to Genesys, the DSS call center utilized a phone system called Cisco. Ex. 2

at 118:21–23.

156. DSS switched from the Cisco system to Genesys because “Genesys provides a

cloud-based solution and better reporting.” Ex. 2 at 119:5–8.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 30 of 113

u

157. Genesys allows DSS to manage the call center system in-house, rather than

through an outside agency. If DSS wants to change something in the Genesys system, they can

“do it very quickly.” Ex. 3 at 98:5–20.

158. In Cisco, there were a limited number of lines available to callers. Ex. 3 at 48:24–

49:18; Ex. 43.

159. Under the Cisco system, if at a given time the number of callers exceeded the

number of lines available, any new call in to the queue would be deflected. Ex. 2 at 120:24–

121:15; Ex. 3 at 48:24–49:18.

160. Genesys, as a cloud-based system, has no limitations to the number of lines that

can be used. Ex. 3 at 48:24–49:18.

161. There are two Tiers within the call center: Tier 1 and Tier 3. Ex. 2 at 75:14–76:2.

162. Tier 1 calls are calls that are routed to staff regarding general DSS information.

Ex. 2 at 75:14–24.

163. Tier 3 calls are calls that are routed to staff to complete a SNAP interview. Ex. 2

at 75:14–76:2.

164. Tier 3 calls are further broken down into two components: “inbound” interview

calls and “outbound” interview calls. Ex. 2 at 84:2–10; Ex. 4 at 200:25–201:4.

165. At the start of this litigation, there were three tiers in the call center. This included

the two tiers that continue to exist (Tier 1 and Tier 3), along with a Tier 5. Tier 5 calls were used

to handle Temporary Assistance and Child Care case updates and interviews. Tier 5 was

discontinued on September 19, 2022. Ex. 44, DEF 46005.

166. The call center’s hours are from 6:00 AM – 6:00 PM, Monday through Friday.

Ex. 3 at 32:19–23.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 31 of 113

v

167. Callers access these tiers through two different phone numbers:

a. General information line

6

: 855-373-4636

b. SNAP interview line

7

: 855-823-4908

See Ex. 2 at 47:3–9; Ex. 45, DEF 0137415; Ex. 7.

168. When calling either the general information line or the SNAP interview line

numbers, the caller enters an IVR system. Ex. 2 at 46:22–47:9, 77:21–25.

169. When a caller dials the general information line, the IVR system presents various

menu options, and the caller can indicate they are calling for help with SNAP. Once in the SNAP

flow, a caller will enter their case number or SSN with their date of birth, and the system checks

to see if a case exists and where in the process it is. Ex. 7 at 0137452.

170. If the information yields a case with a pending interview, the IVR will offer the

option to transfer to Tier 3. Ex. 7 at 0137452–53.

171. For all other callers, the system will play an applicable message, and move the

caller to a menu where they will have the option to transfer to Tier 1. Ex. 7.

172. When a caller dials the SNAP interview line, they are asked to enter their case

number or SSN with their date of birth. The system will check whether an interview is needed on

their case, and if so, the caller will be transferred to Tier 3. If the system does not report that an

interview is needed, the caller will be transferred to Tier 1. Ex. 45 at 0137416.

173. Since June 22, 2021, the IVR flow for the general information line and SNAP

interview lines have changed multiple times. Ex. 42 ¶ 8.

174. On November 15, 2021, questions were added to the SNAP interview line and

general information line IVR for a total of twenty-two interview questions. Ex. 42 ¶ 8.

6

The general information line is also referred to by DSS as the FSD Information Line.

7

The SNAP information line is also referred to by DSS as the Application Interview Line.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 32 of 113

w

175. Callers to the general information line or the SNAP interview line were required

to answer the twenty-two yes/no questions before being transferred to the Tier 3 queue. Ex. 46,

DEF 0137592 at 1037606–08; Ex. 47, DEF 0137610 at 0137613–14.

176. By August 1, 2022, another question was added to the list of twenty-two yes/no

questions callers had to answer before being transferred to the Tier 3 queue. Ex. 48, DEF

0137525 at 0137528–29; Ex. 49, DEF 0137534 at 0137548–50.

177. Then, by January 27, 2023, the twenty-three yes/no questions were deleted from

the IVR menus. Ex. 50, DEF 0137399; Ex. 45.

178. Furthermore, before February 3, 2023, if a caller to the general information line

entered their case number or SSN and date of birth and the system found that the caller needed to

do an interview, the system would tell the caller to press 1, and subsequently transfer the caller to

the Tier 3 queue. Ex. 51, DEF 0137417 at 0137420.

179. As of February 3, 2023, if a caller failed to press 1, the line disconnected. Ex. 52,

DEF 0137433 at 0137436.

180. Now, before a caller is placed in a queue, the phone system checks the relevant

queue to determine whether it is “too full to handle the phone call[].” Ex. 3 at 46:22–47:7.

181. Shortly after the switch to Genesys was made, DSS added logic to the phone

system to limit the number of calls in each queue. Ex. 42 ¶ 8.

182. To determine whether the queue is too full, Genesys performs a calculation each

time a call comes in. Genesys first looks to see how many callers are in the queue. If there are

fewer than the predetermined number of callers programmed in by DSS, the system moves the

call into the requested queue. Ex. 3 at 49:24–50:23.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 33 of 113

x

183. If there are more than the predetermined number of callers already in the queue,

Genesys performs an additional calculation. Ex. 3 at 49:24–50:23.

184. Genesys evaluates the estimated wait time for a call and adds an additional

“padding” to that wait time. If the wait time plus padded time is later than when the call center

closes for the day, Genesys plays a recorded message and then terminates the call. Ex. 42 ¶ 8;

Ex. 43; Ex. 2 at 122:6–21; Ex. 3 at 49:24–50:23.

185. As of May 10, 2023, the calculation for a call to the Tier 3 queue was the

estimated wait time calculation plus two hours. Ex. 2 at 122:6–21.

186. The calculation to determine when calls should be deflected has changed multiple

times since the transition to Genesys in June 2021. Ex. 43.

187. When the deflection logic was added to Genesys in July 2021, the system did not

query the number of callers in the queue before moving to the wait time calculations. Instead, the

calculation would run for all callers. Ex. 43.

188. Initially, Genesys evaluated the estimated wait time and added two hours of

padding. Ex. 43.

189. Callers were able to hold their place in the queue by requesting a call back. Ex. 42

¶ 8.

190. In mid-July 2021, the padding time for both Tiers was changed from two hours to

four hours. Ex. 43.

191. In mid-August 2021, the padding time for Tier 3 was decreased from four hours

to two hours. The padding time for Tier 1 remained at four hours. Ex. 43.

192. On August 17, 2021, the call back feature caused a backlog, as call back requests

from the previous day were scheduled to the next morning. Ex. 42 ¶ 8; Ex. 25 at 131:4–19.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 34 of 113

y

193. On August 19, 2021, the option to request a call back was turned off. Ex. 42 ¶ 8.

194. At the end of August 2021, DSS implemented logic to first evaluate how many

callers were in the queue, as described in paragraph 182. This number was initially set at 100.

Ex. 43.

195. In April 2022, the padding time for Tier 1 was decreased from four hours to two

hours. The padding time for Tier 3 was increased from two hours to three hours. Ex. 43.

196. In May 2022, the number of callers who must be in the queue to trigger the

padding time calculation decreased from 100 to 50. Ex. 43.

197. If there are fewer than 50 callers in the queue, the caller is placed in the Tier 3

queue. Ex. 43; Ex. 3 at 49:24–50:23.

198. If the deflection logic runs and the estimated wait time plus three hours will be

before the call center closes, the caller is placed in the Tier 3 queue. Ex. 3 at 49:24–50:23.

199. In early 2023, the call center changed the messaging a caller would hear when the

queue was full. Before this change, the caller would be told that the call center was “unable to

take your call, please try your call back again later.” Now the message gives the caller a list of

options. Ex. 25 at 171:17–172:16; 231:6–232:5.

200. These options include live chat, visiting the website, going to the local Resource

Center, or reporting changes and looking at benefits online. Ex. 25 at 171:17–172:16.

201. As a result of this change in messaging, the call center no longer labels calls that

are turned away as “deflected” calls, but rather as “redirected” calls. Ex. 25 at 231:6–232:5.

202. This is merely a change in terminology. Like deflected calls, redirected calls are

not able to reach a call center worker to complete an interview. Ex. 25 at 231:6–232:5.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 35 of 113

z

203. Once in the queue, the caller is informed of the number of people ahead of them

in the queue. See Ex. 2 at 144:19–145:1; Ex. 3 at 151:19–152:6, 218:4–16; ECF 6-1 ¶¶ 27, 28,

32; Ex. 23 ¶¶ 10, 11, 14.

204. The caller is not informed how long the expected wait time in the queue is. See

Ex. 2 at 144:19–145:1; Ex. 3 at 151:19–152:6, 218:4–16; ECF 6-1 ¶¶ 27, 28, 32; Ex. 23 ¶¶ 10,

11, 14.

Predictive dialer

205. DSS utilizes a predictive dialer to call SNAP applicants and attempt to complete

their interviews. Ex. 2 at 83:14–22.

206. Applications are registered in DSS’s case management system, FAMIS.

Applications that require an interview are flagged in FAMIS. Ex. 2 at 231:21–232:5.

207. Once FAMIS has flagged that an interview is needed, the application is added to

the predictive dialer list. The following day, the predictive dialer makes a call out to the phone

number associated with the application. Ex. 2 at 83:14–22, 85:18–86:1, 233:3–11.

208. Applicants with especially low income and no resources are eligible for expedited

processing of their applications. 7 U.S.C. § 2020(e)(9); 7 C.F.R. § 273.2(i)(1).

209. Applications that are identified as eligible for expedited processing receive one

call a day for two days (or until the interview is completed) from the predictive dialer. Ex. 53,

DEF 0137397; Ex. 2 at 146:21–147:6.

210. All other applications receive only one call. Ex. 53; Ex. 2 at 148:6–13.

211. DSS has not amended the waiver to reflect actual agency practice. Ex. 2 at 150:6–

14; Ex. 54, DEF 0140761; Ex. 55, DEF 0140775; Ex. 56, DEF 0144576; Ex. 57, Excerpts from

Mitchem Dep. at 38:5–40:2.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 36 of 113

aa

212. The predictive dialer begins making calls at 7:00 AM each day that the call center

is open. Ex. 2 at 253:13–17; Ex. 3 at 179:14–180:18; Ex. 25 at 50:17–51:1.

213. The number of calls the dialer makes at one time depends on the number of staff

who are logged in to handle Tier 3 outbound calls. Ex. 3 at 179:14–180:18, 197:6–198:7.

214. When Genesys went live in June 2021, the predictive dialer was programmed to

make five calls per staff member logged in to handle Tier 3 outbound calls. Ex. 3 at 197:6–24.

215. Because the call center was not able to handle this volume of calls, DSS changed

this (later in the month) by programming the predictive dialer to make one call per staff member

logged in to handle Tier 3 outbound calls. Ex. 3 at 197:6–198:7.

216. Staff who are logged in to the predictive dialer line are also logged in to the Tier 3

inbound line. Ex. 3 at 188:12–21; Ex. 25 at 92:13–25.

217. All Tier 3 workers are doing outbound and inbound calls. Ex. 25 at 94:25–95:14.

218. The Tier 3 outbound line has priority over the Tier 3 inbound line. Ex. 3 at

181:23–182:8; 189:23–190:1; Ex. 2 at 85:18–86:15.

219. Because Tier 3 outbound calls are prioritized over Tier 3 inbound calls, the Tier 3

outbound calls are directed to a worker ahead of Tier 3 inbound calls. Ex. 25 at 95:8 – 97:21.

220. The predictive dialer runs until it dials the entire list of phone numbers from

applications that were registered the previous business day. Ex. 2 at 253:18–22.

221. If the list of applications cannot be completed before the close of business for the

day, the list carries over to the following day. Ex. 2 at 253:23–254:3.

222. The daily load of predictive dialer calls generally ranges from 1,300 to 2,500. Ex.

25 at 93:9–16.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 37 of 113

bb

223. In late May and early June 2023, the predictive dialer load was consistently “well

above 2,500,” and reached 4,500 on June 14, 2023. Ex. 25 at 94:4–10.

224. If a caller picks up the predictive dialer call, the caller is placed in the predictive

dialer IVR menu. Ex. 53; Ex. 3 at 38:9–39:4.

225. The IVR provides the option to: Press 1 if the person who answered is the

applicant and has 20-30 minutes to complete the call; Press 2 if the person who answered does not

have time to complete the call; Press 3 if the applicant has already completed an interview; Press

4 if the person who answered is not the person who applied and cannot get the applicant on the

phone in the next three minutes; or, Press 5 if the person who answered is not the person who

applied, but can get the applicant in the next three minutes. Ex. 53.

226. If the person who answers presses 5 but is unable to get the customer in the three

minutes given, the call disconnects. Ex. 3 at 39:6–12.

227. If the person who answers presses 2, the application is never placed in the

predictive dialer list again. Ex. 3 at 184:17–22.

228. If the person who answers presses 1, they are routed into the Tier 3 outbound

queue. Ex. 3 at 181:23–182:8.

229. If all workers are on other calls when the caller enters the Tier 3 outbound queue,

the caller is put on hold. Ex. 3 at 195:12–16.

Appointment scheduler

230. SNAP applicants have the option to schedule an appointment to be seen in person

at a Resource Center or to receive a phone call from a DSS staffer at a specific date and time. Ex.

2 at 104:23–105:21.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 38 of 113

cc

231. Applicants can schedule appointments by using DSS’s appointment scheduler or

by walking into a Resource Center and scheduling an appointment with a representative. Ex. 2 at

105:14–18.

232. However, same day appointments are not reliably available for Resource Centers.

Ex. 2 at 163:15–164:5.

233. DSS implemented a new appointment scheduler in March 2023. Ex. 2 at 113:17–

21.

234. The appointment scheduler is available through the call center, (Ex. 3 at 151:13–

18), but there is no menu option in the IVR in either the general information line or the SNAP

interview line for a caller to schedule an appointment. Ex. 2 at 261:4–262:24; Ex. 7; Ex. 58, DEF

0139744.

235. The option to schedule an appointment is only offered once the caller makes it

into a queue. Ex. 2 at 144:19–145:1; Ex. 3 at 151:19–152:6, 159:13–25; Ex. 7; Ex. 58.

236. Because a caller is not offered the option to schedule an appointment until they

are placed in the queue, the appointment scheduler is not offered to deflected callers. Ex. 2 at

144:19–145:1; Ex. 3 at 151:19–152:6, 159:13–25; Ex. 7; Ex. 58.

237. Applicants can also access the automated appointment scheduler through

DSSChat. Ex. 3 at 147:3–5; Ex. 4 at 236:22–25.

238. DSSChat is a chat platform available on DSS’s website. It features a chatbot,

which is “like an IVR but on chat.” Ex. 3 at 140:1–14, 144:19–145:4.

239. When applicants begin a chat, they are offered the option to “Make appointment,”

and can choose to schedule an in-person appointment or a phone appointment. Ex. 3 at 142:1–21.

Case 2:22-cv-04026-MDH Document 138 Filed 09/22/23 Page 39 of 113

dd

240. Applicants can indicate to DSSChat when they want their appointment. If that

time is not available, DSSChat returns the next three possible options for appointments. Ex. 3 at

147:3–15.

241. There are 15 phone appointment slots available per hour for the entire state. Ex. 3

at 177:14–178:13.

242. The number of appointments at a Resource Center depends on the hours and

staffing of the Resource Center. Ex. 5 at 127:21–128:9.