PREDECISIONAL

1

Missouri Department of Social Services

Rapid Response Review –

Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

FINAL REPORT

February 11, 2019

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

2

Contents

Executive Summary 3

Overview of Medicaid Program 7

The Current Program 7

Major Industry Trends Affecting the Program 11

Projected Spending Without Significant Course Corrections 13

Opportunities and Potential Initiatives 16

Acute Care Services 17

Long-Term Services and Supports 43

Pharmacy 57

Managed Care 62

Program Integrity 73

Federal Financing 79

Medicaid Management Information System (MMIS) 83

Operations 93

Implementation Considerations 110

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

3

Executive Summary

Missouri’s Medicaid program is an important safety net for Missouri’s most vulnerable

populations, providing health care and support for activities of daily living for nearly one million

Missourians. Children in low-income families comprise 63.5% of participants, while persons with

disabilities comprise the largest share (46%) of spending. In State Fiscal Year (SFY) 2018, total

spending for the program was approximately $10 billion, funded 53% by federal funds, 21% by

state general revenues, and the balance by provider taxes and other funds.

Analysis of historical trends indicates that the financial sustainability of Missouri’s Medicaid

program is currently under pressure: Medicaid spending has grown from 17% of state general

revenues in SFY2009 to 24% in SFY2018. Based on continuation of these trends, spending

could grow to 26% by SFY2023. This number could be even higher (30%) if Missouri were to

experience an economic downturn, given the potential for such a downturn to increase Medicaid

enrollment while also reducing growth in state general revenues.

Under any of the scenarios described in the pages that follow, significant changes in the

structure and performance of Missouri’s Medicaid program would be necessary to bring

Medicaid spending growth in line with projected economic growth of the state.

Opportunities for Improvement

Since October, a detailed assessment of the Missouri Medicaid program has uncovered a wide

range of opportunities for improvement, which may collectively deliver substantial reductions in

the rate of growth of Medicaid spending. These opportunities, detailed in the pages that follow,

are based on extensive interviews with state agency leaders and staff, detailed analysis of

claims- and non-claims data, review of agency operations, and benchmarking against other

states as well as Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) and other health insurers.

High-level summaries are provided below for each of eight programmatic and functional areas.

Further details follow in the report, including descriptions of opportunities (with supporting facts)

and potential initiatives that may be considered by the state in shaping its approach to Medicaid

transformation. Potential initiatives include possible changes to provider payment methods, care

management, and contracting with MCOs and other vendors, as well as improvements in

agency and vendor operations. A selection of potential initiatives outlined in the following pages

could collectively enable the Medicaid program to achieve significant cost savings while

maintaining or improving access to high-quality care, without broad-based cuts in provider rates,

or reductions in eligibility or covered services.

Were Missouri to effectively address the opportunities and potential initiatives outlined in this

report, total savings to the program (including federal and state share) could total up to $0.5-1.0

billion by SFY2023. This level of savings, while significant, does not represent an absolute

reduction in the size of the Medicaid program but rather a meaningful reduction in the rate of

growth of Medicaid spending, to bring it more closely in line with growth of the economy.

Implementing changes at this scale would make the program more financially sustainable under

all future financing scenarios, allowing for the state to continue to make investments to protect

the program’s essential role in serving the state’s most vulnerable populations.

Acute Care Services. Missouri spent ~$4.2 billion in SFY2018 on acute care services, including

hospital, clinic, physician, and diagnostics services, across both the managed care and non-

managed care populations. (Pharmaceutical services are discussed in a separate section).

Provider payment for acute care providers in Missouri is currently almost exclusively fee-for-

service. Fee schedules are based on historical costs; in some cases, these are adjusted each

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

4

year based on changes in operating costs. Accordingly, the payment methods used offer few

incentives for providers to contain costs. A significant proportion of Missouri Medicaid acute

care expenditures is associated with potentially avoidable exacerbations and complications

(PECs) and inefficiencies in the choice of provider, site, or treatment. In addition, Missouri

Medicaid is unique in making “add-on payments” to hospitals for services provided by Missouri

hospitals to non-Missouri residents. Potential initiatives to improve incentives and reduce costs

include adjusting rate setting methodologies, moving to value-based payment models, and

investing in the rural and safety net heath care infrastructure, including primary care and

behavioral health. In total, the gross impact of Acute Care initiatives could range anywhere from

$250 million to $500 million, depending on choices made by the state.

Long-Term Services and Supports. Missouri spent ~$2.9 billion in SFY2018 on long-term

services and supports (LTSS) for approximately 106,000 Medicaid participants accessing these

services. LTSS in Missouri consist of institutional services (e.g., nursing homes for frail elderly,

intermediate care facilities for individuals with intellectual disabilities), and home and

community-based services (both residential and non-residential) covered by the Medicaid State

Plan and nine waivers. Nursing facilities are reimbursed using a cost-based, facility-level per

diem methodology without adjustments for acuity, quality, or outcomes, and home and

community-based services (HCBS) are reimbursed on a fee-for-service basis. LTSS in Missouri

are administered by Missouri Medicaid in conjunction with the Department of Health and Senior

Services (DHSS) and the Department of Mental Health (DMH), each of which administers

HCBS waivers and conducts assessments to determine access to LTSS. The assessment

process currently in use by DHSS uses decades-old standards and, as such, may not

consistently determine institutional level of care accurately. Potential initiatives include

incorporating an acuity adjustment into the nursing home reimbursement methodology,

completing and expanding upon revisions currently underway for the state's assessment

algorithms, more directly applying assessment results in the care planning process, and

improving the consistency of the prior authorization approval process for personal care services.

In total, the gross potential impact across LTSS initiatives ranges from $90 million to $275

million, depending on choices made by the state.

Pharmacy. Missouri spent ~$1.5 billion in SFY2018 on pharmaceutical products. This spending

is inclusive of all participants as the state carves pharmacy benefits out of its MCO

arrangements. The state utilizes a preferred drug list and receives statutory and supplemental

rebates to help control costs. The basis for drug ingredient cost reimbursement was recently

updated, and Missouri is in the process of updating dispensing fees. Missouri rebate

performance is below the average for other states, potentially due to expansive grandfathering.

While the state uses a broad range of approaches to ensure appropriate utilization, there is an

opportunity to expand it to other high-cost drug classes such as oncology, hemophilia, and IVIG.

Potential initiatives include limiting grandfathering, implementing additional utilization

management, joining a purchasing consortium to increase supplemental rebate capture,

requiring NDC submission on claims for non-J-code HCPCS drugs, and applying for a value-

based contracting waiver from CMS. In total, the gross potential impact across Pharmacy

initiatives ranges from $35 million to $60 million, depending on choices made by the state.

Program Integrity. Program integrity functions within the state Medicaid agency center serve to:

prevent fraud, waste, and abuse; ensure proper participant enrollment and identify third-party

resources to pay for medical claims. Numerous divisions within the state help accomplish these

goals; however, the separation of divisions leads to siloed data and communication. Potential

initiatives include expanding adoption of best practices from the National Correct Coding

Initiative, updating certain medical and reimbursement policies to prevent improper payments,

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

5

implementing claims edits that would prevent improper billing based on Missouri’s current

policies, optimizing the state’s ability to identify and enroll participants who are eligible for

Medicare, and improving third-party liability identification. In total, Program Integrity initiatives

could deliver savings between $65 and $100 million, depending on choices made by the state.

Managed Care. Missouri's Medicaid managed care program covers primarily acute care and

professional services for non-disabled adults and children. Approximately 75% of Medicaid

participants are covered by managed care, whereas approximately 23% of Medicaid

expenditures (~$2.2 billion) flow through managed care contracts. Most pharmacy and

behavioral health services for the managed care population remain "carved out" of managed

care; the Medicaid aged, blind, and disabled (ABD) population is entirely excluded from the

current managed care program. Potential initiatives include incorporating additional adjustments

to managed care rates to remove inefficient utilization (e.g., inpatient stays that could have been

avoided with better outpatient care) from rate calculations, expanding day-one managed care

eligibility to streamline participant transitions and reduce residual fee-for-service payments,

strengthening key contract provisions and the compliance and performance management

relationship between MHD and the MCOs, and altering the scope of the managed care

program—for example, including additional services or Medicaid eligibility groups. In total, the

gross potential impact of all Managed Care-related initiatives ranges from $175 million to $300

million, depending on choices made by the state.

Federal Financing. Federal Financing focuses on identifying opportunities to optimize federal

funding for the state’s Medicaid program. Overall, Missouri has been able to capture a

significant share of the available federal funding opportunities, capturing funds across Medicaid

spending and non-Medicaid spending within DSS, DMH, and DHSS and capturing enhanced

match on select categories. However, there remain several opportunities that the state could

pursue to capture additional federal funding. These opportunities could include new waiver and

grant programs released in the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act, enhanced match

on substance use disorder (SUD) focused health homes, among others. In total, potential

impact from these improvements may be $10 million to $20 million, based on choices made by

the state.

Medicaid Management Information System. Missouri’s Medicaid Management Information

System (MMIS) is a set of ~70 components, partially developed within a mainframe-based

system dating from 1979. The system supports a wide range of vital activities within the

Medicaid program, but is not positioned to meet both current and future needs. Its limited

functionalities underlie several of the opportunities for improvement identified in other topical

areas. There is little alignment between program strategy and the MMIS replacement plan, and

the Information Systems (IS) group lacks the wide range of capabilities needed to ensure an

MMIS replacement trajectory that will deliver the future functionality Missouri needs. The

potential initiatives discussed in this section attempt to address these challenges.

Operations. This section analyzes the performance and operational efficiency of three

operational functions: participant managed care enrollment, claims processing, and contact

centers. These functions are currently executed through a mix of state staff and vendor

contracts. In comparison to other states, work processes often appear fragmented, process

steps seem poorly integrated and best-practice management principles are variably applied.

Potential initiatives include organizational process optimization, automation and digitization, and

improved contract management. Adoption of best practices across the different functional areas

could liberate up to 15-20% of operational resources, which could be redeployed to improve

service levels for participants and for other external and internal “customers” of the different

functions.

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

6

Implementation Considerations

The potential initiatives described in the following pages are wide-ranging, including operational

improvements to bring the program up to date with common practices among other state

Medicaid programs, as well as best practices and more transformational changes. Some of the

potential initiatives outlined represent alternative ways of achieving similar goals: in some

cases, the initiatives could reinforce one another; in other instances, they could be mutually

exclusive. Such interdependencies will be highlighted throughout.

Broadly, the state could balance two approaches to controlling spending. One approach

commonly adopted by both public programs and managed care would rely primarily on

controlling the unit prices paid for services and seeking to curb utilization through broad-based

utilization management. Such an approach could reduce costs in the short term. However, on its

own such an approach may not provide incentives to improve outcomes. As an alternative

approach, the state could seek to adopt value-based payment and care delivery models that

reward providers for quality and efficiency of the total care delivered to patients. This approach

may support more transformational changes in care delivery, with corresponding improvements

in patient outcomes and experience. However, such an approach is likely to require greater

commitment of resources and will take longer to generate impact given the need for providers to

adopt new capabilities and implement changes in clinical practices.

Aligning the growth of Medicaid expenditures with the state’s economic growth may involve a

combination of these approaches, with targeted use of utilization management and targeted

adjustments in provider rates in the near-term, combined with investments in care management

and value-based payment to support sustainable improvements in quality and efficiency. In

parallel, there may be a series of operational changes that the state could implement to bring

policies and operations up to speed with common practices, such as state-of-the-art program

integrity measures and improvements of internal administrative processes. Such changes could

generate near-term savings to offset investments in transformation changes.

Any substantial portfolio of initiatives would demand careful planning and execution, as well as

investments to support the transformation and build new capabilities. Key requirements for

effective design and implementation of Medicaid transformation include: strong and visible

executive leadership; effective stakeholder engagement; commitment to fact-based decision

making supported by robust data; upskilling of key agency staff; a well-resourced transformation

office; and modernization of the program’s technological infrastructure.

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

7

Overview of Medicaid Program

In State Fiscal Year 2018, Missouri Medicaid was a $10.3 billion program, funded by state

general revenue ($2.2 billion), federal funds ($5.5 billion), and other funds ($2.6 billion).

1

The

“other funds” consisted primarily of revenue from provider taxes ($1.4 billion).

2

Since 2009, Medicaid spending has grown in proportion to the total state budget, and in

proportion to state general revenues. In 2009, Medicaid spending comprised 17% of state

general revenues; in 2018, it was 24%.

3

Without significant changes in the Missouri Medicaid

program, spending growth may continue to outpace growth in state general revenues and

could comprise 26-30% of state general revenues by 2023.

4

The following pages provide a brief introduction of the Missouri Medicaid program and a

summary of key trends in the larger U.S. healthcare context that influence program spending,

as well as state fiscal scenarios that could lead Medicaid spending to represent a greater

share of state general revenues.

THE CURRENT PROGRAM

Enrollment and Spending

Missouri Medicaid is a $10.3 billion program that covers predominantly four types of

participants: low-income children; parents of low-income children; pregnant women; and aged,

blind, or disabled (ABD) individuals.

5

Children comprise the largest eligibility group in Missouri

Medicaid, representing 63.5% of enrollees; however, persons with disabilities account for the

greatest proportion (46%) of Medicaid spending (see Exhibit 1 and Exhibit 2).

1

Missouri DSS, “TSM Expenditures History FY05 to FY18,” 2018; Missouri DSS, “Final FY18 Total State Medicaid

Expenditures,” 2018.

2

Missouri DSS: see note 1.

3

Missouri DSS: see note 1.

4

Analysis based on projections from past trends. Missouri DSS: see note 1.

5

Missouri DSS, “MO HealthNet enrollees and expenditures,” 2018, see: dss.mo.gov/mhd/general/pdf/mhdollars.pdf.

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

8

EXHIBIT 1: MEDICAID ENROLLMENT & SPENDING BY ELIGIBILITY CATEGORY, SFY2018

6

EXHIBIT 2: MEDICAID ENROLLMENT & SPENDING BY TYPE OF COVERAGE, SFY2018

7

6

Missouri DSS: see note 5.

7

Missouri DSS: see note 5.

63.5%

12.3%

8.2%

16.0%

Persons with

disabilities

Seniors

46.0%

$4.3B

Enrollees by

eligibility category

27.5%

$2.6B

16.9%

$1.6B

9.6%

$0.9B

Expenditures by

eligibility category

100% = $9.4 billion

Children

Pregnant women,

custodial parents

100% = 976,779 enrollees

63.5%

22.9%

12.3%

14.2%

8.2%

62.9%

16.0%

Seniors

Persons with

disabilities

Enrollees by

eligibility category

Expenditures by

type of coverage

Children

Pregnant women,

custodial parents

Fee-for-service

population

FFS spend for

MC population

Managed care

100% = 976,779 enrollees 100% = $9.4 billion

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

9

Services for >155,000 persons with disabilities and >80,000 elderly participants (the aged, blind

and disabled [ABD] population) are provided through Medicaid fee-for-service, comprising

24.2% of enrollees but 62.9% of total program expenditures. The ABD population includes

distinctive subpopulations with different cost patterns: frail elderly, individuals with intellectual

and/or developmental disabilities, individuals with severe behavioral health issues, and others.

Non-disabled children, parents, and pregnant women comprise 75.8% of enrollees (about

650,000 in all) but 37.1% of total program costs, of which 22.9% is covered through managed

care and 14.2% (pharmacy and behavioral health) is paid through Medicaid fee-for-service.

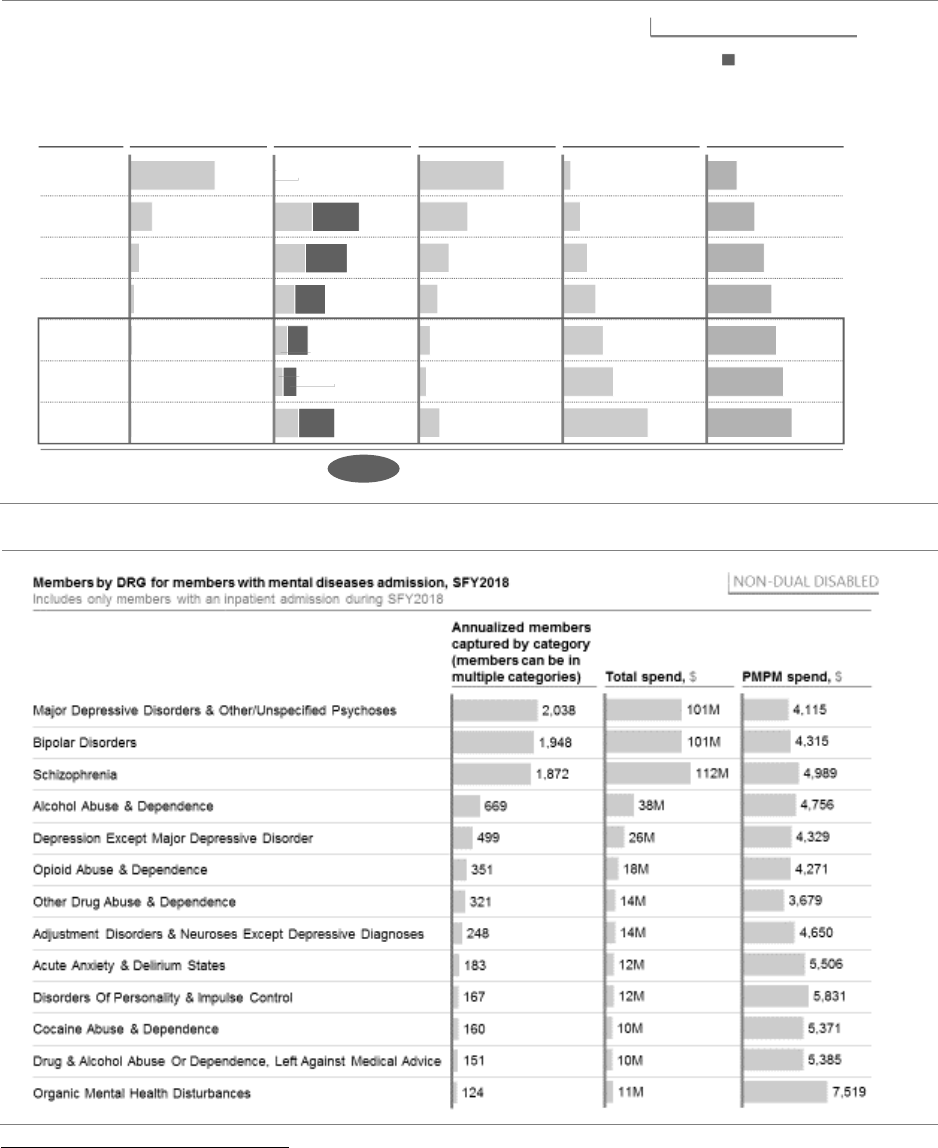

Exhibit 3 shows one possible categorization of diagnostic groups,

8

including numbers of

participants per group, and average per member per month (PMPM) spending per main

category (institutional long-term services and supports [LTSS], home and community-based

services [HCBS], acute services).

All elderly and 40% of individuals with disabilities are dually eligible for both Medicaid and

Medicare. For these participants, Medicare pays for the acute care costs (e.g., hospitals,

physicians, drugs); Medicaid pays for long-term services and supports (e.g., home care, nursing

homes).

EXHIBIT 3: SUBPOPULATIONS WITHIN THE ABD POPULATION, SFY2018

9

8

Medical diagnosis, procedure codes and demographic information from Missouri Medicaid claims for SFY2018

were used to develop sub-segmentations of ABD population by diagnosis category. Diagnosis categories are based

on claims data only, with the exception of the frail elderly category which is based on age and participant chronicity.

9

Analysis of Missouri Medicaid claims data, SFY2016-18; participants may overlap across categories.

6.8

36.4

38.6

73.4

28.3

20.7

22.2

6.6

39

32

44

45

48

45

60

35

Institution

HCBS

LTSS

Non-LTSS

Other

Physical

disability

Sensory Deficit

Conditions

High needs BH

ID/DD

ABI

Neurodegenera-

tive Conditions

SFY 2018 average

participants, K

Average spend, $K

PMPYABD population Description

Annualized

participants, %

total

Frail elderly

35%

70%

6%

27%

37%

20%

21%

6%

298

1,156

2,863

1,264

1,750

229

1,245

1,060

Total spend, $M

▪ Do not meet criteria of any of the above

▪ Traumatic brain injury

▪ Cerebral infarction

▪ Cerebral hemorrhage

▪ Genetic syndromes with intellectual disability

▪ Congenital brain injury

▪ Developmental disability (e.g., Autism)

▪ Presence of a behavioral health diagnosis, or

utilization, with at least one mental health

condition

▪ Dementia, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, ALS,

Multiple Sclerosis

▪ Blindness

▪ Hearing loss

▪ Spinal cord injury

▪ Paralysis

▪ Chronic pain / weakness

▪ Age 65+ with 2 or more chronic conditions

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

10

Financing and Budget

Missouri Medicaid is funded by state general revenue ($2.2 billion), federal funds ($5.5 billion),

and other funds ($2.6 billion).

10

The “other funds” are primarily provider taxes ($1.1 billion from

hospitals, and $0.3 billion from nursing homes and pharmacies).

11

As these taxes generate

federal matching funds (nearly two federal dollars for every dollar generated through provider

taxes

12

), they are significant to the financing of the Missouri Medicaid program. Exhibit 4 shows

the flow of funds, highlighting the hospital tax and its integration in the Medicaid funding flow.

EXHIBIT 4: MISSOURI MEDICAID FUNDS FLOW (SFY2018, USD BILLIONS)

13

Organization

Three departments jointly manage parts of the Medicaid program. The Department of Social

Services (DSS) operates MO HealthNet (MHD), which is primarily responsible for medical

expenses for eligible individuals. This includes both the fee-for-service and the managed care

populations. The Department of Mental Health (DMH) administers services for populations with

10

Missouri DSS: see note 1.

11

Missouri DSS, “Provider taxes overview,” 2018.

12

Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), “Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) for Medicaid and Multiplier,”

2018, see: www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/federal-matching-rate-and-multiplier.

13

Office of Administration, “The Missouri budget fiscal year 2018 summary,” 2018, see:

www.oa.mo.gov/sites/default/files/FY_2018_Budget_Summary.pdf; Missouri DSS: see note 1; Missouri DSS: see

note 11; Missouri DSS, “Annual_Table 23 and 24_FY18 by Large Group PMPM,” 2018; Missouri DSS, “Payments

Assessment for SFY 14-18,” 2018.

Federal funds

Other funds

General revenue

Medicaid spend

5.5

2.2

2.6

9.4

8.8

9.4

10.3

1.1

Federal match of provider tax

2.2

State gov’t collects ~5.5%

FRA tax on provider

revenue

3

Federal gov’t

matches revenue

collected from

provider tax

27.6

Overall MO budget Medicaid Hospitals

IP/OP reimbursement

(Medicaid FFS)

2.8

IP/OP reimbursement

(all other payors)

17.9

IP/OP reimbursement

(Medicaid MC)

1.5

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

11

developmental disabilities (both intellectual and physical disabilities, as well as certain learning

disabilities), community-based health centers, psychiatric rehabilitation services, comprehensive

substance treatment and rehabilitation (CSTAR) services, and health home programs, amongst

others. The Department of Health and Senior Services (DHSS) operates the Division of Senior

and Disability Services (DSDS), which administers the HCBS benefits for adults 18 and over,

and Special Health Care Needs (SHCN), which administers the Healthy Children and Youth

benefits for persons with special health care needs up to 21 years of age. DSS is responsible

for the largest share of Medicaid spending at approximately $7.9 billion, DMH’s share is $1.5

billion, and DHSS’ share of Medicaid spending is $0.9 billion.

14

MAJOR INDUSTRY TRENDS AFFECTING THE PROGRAM

Healthcare inflation rising faster than GDP

The United States faces increasing pressure to contain its rising healthcare costs. In 2017, total

U.S. healthcare spending reached $3.5 trillion, marking a 3.9% increase from the previous year,

amounting for almost 18% of gross domestic product (GDP)

15

. U.S. health spending per person

climbed to over $10,739 in 2017, the third year that the spending has exceeded $10,000.

16

The

growth in per-person spending, or medical cost inflation, outpaces the general inflation rate (see

Exhibit 5). CMS projects spending to grow 1% faster than GDP to reach $5.7 trillion by 2026.

17

EXHIBIT 5: MEDICAL INFLATION, GENERAL INFLATION, GDP GROWTH, SFY2001-17, %

18

14

Missouri DSS: see note 1.

15

CMS, “NHE Fact Sheet,” 2017, see: www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-

reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nhe-fact-sheet.html.

16

CMS, “The National Health Expenditure Summary including share of GDP, CY 1960-2017,” 2017,

www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-

Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.html.

17

The Balance, “U.S. Inflation Rate by Year from 1929 to 2020,” 2019, see: www.thebalance.com/u--inflation-rate-

history-by-year-and-forecast-3306093; The Balance, “U.S. GDP by Year Compared to Recessions and Events,”

2019, see: www.thebalance.com/us-gdp-by-year-3305543.

18

The Balance: see note 17.

9

8

6

6

6

5

4

3

3

3

3

4

5

4

3

2

2

3

4

3

2

3

2

1

1

2

2

2

3

4

4

3

2

3

2

2

3

3

2

03 09052001 1402 04 06 1007 11 20171208 13 15 16

1

2

2

2

3

7

3

0

0

-3

2

2

Medical inflation rate

General inflation rate

GDP growth rate

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

12

Costs are rising in Medicare and Medicaid, putting pressure on both federal and state budgets.

In addition, rising health care costs create challenges in the commercial market as well.

Employees’ contribution to health insurance grew almost three times faster than wages between

2010 and 2015,

19

and middle-class Americans’ healthcare spending increased 60% over the

past 30 years.

20

The growing financial burden of healthcare has been a significant factor in the

low growth in purchasing power of the middle class in the U.S. over the past two decades.

21

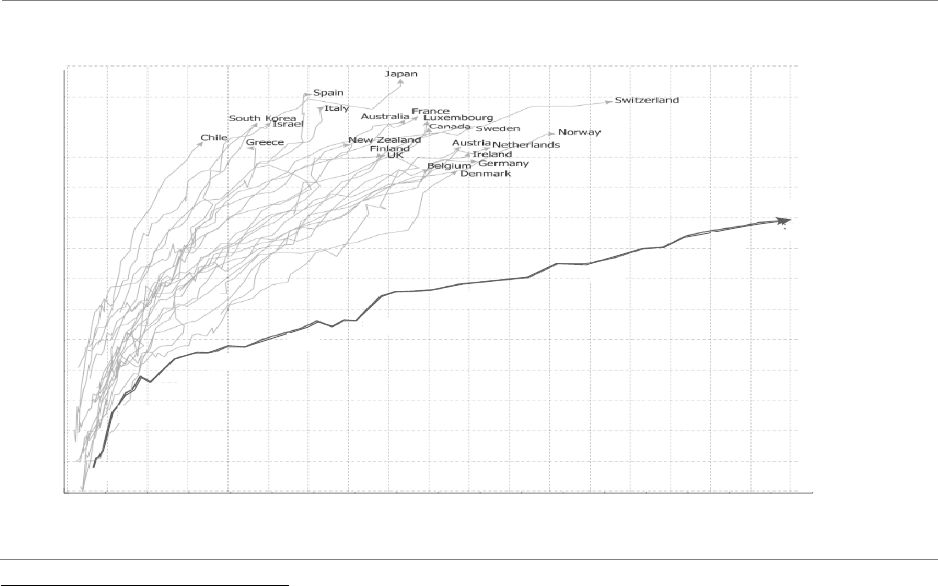

While rising health expenditures are not unique to the U.S., its spending exceeds that of other

countries even after adjusting for differences in average wealth. While outcomes of U.S.

healthcare exceed those of other countries for some catastrophic illnesses and other complex

conditions (e.g. breast and colorectal cancer), outcomes lag other countries for most chronic

conditions.

22

Chronic conditions, in particular, account for a significant portion of healthcare

spending growth, underscoring concerns that increased levels of investment in healthcare have

not translated to proportional improvements in life expectancy or quality of life (see Exhibit 6).

EXHIBIT 6: LIFE EXPECTANCY AND HEALTH EXPENDITURE ACROSS COUNTRIES

23

19

KFF, “2015 Employer Health Benefits Survey,” 2015, see: www.kff.org/health-costs/report/2015-employer-health-

benefits-survey.

20

Hamilton Project, “Where Does All the Money Go: Shifts in Household Spending Over the Past 30 Years,” 2016,

see:www.hamiltonproject.org/papers/where_does_all_the_money_go_shifts_in_household_spending_over_the_pa

st_30_y.

21

Pew Research, “For most U.S. workers, real wages have barely budged in decades,” 2018, see:

www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/08/07/for-most-us-workers-real-wages-have-barely-budged-for-decades/.

22

Peterson-Kaiser Health System Tracker, “How does health spending in the U.S. compare to other countries?”

2018, see: www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/health-spending-u-s-compare-countries;

www.kff.org/slideshow/how-does-the-quality-of-the-u-s-healthcare-system-compare-to-other-countries/.

23

Our World in Data, “Link between health spending and life expectancy: US is an outlier,” 2017, see:

ourworldindata.org/the-link-between-life-expectancy-and-health-spending-us-focus.

70

71

72

73

76

74

75

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

1,000$

Health expenditure

2,000$ 3,000$500$

Life expectancy

0 4,000$ 5,000$ 6,000$ 7,000$ 8,000$ 9,000$

2014

2010

2005

2000

1995

1990

1985

1980

1975

1970

USA

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

13

CMS taking steps to reduce federal spending on health care

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) have undertaken a series of initiatives to

reduce federal healthcare costs for Medicare, ranging from attempts to reduce what it pays for

drugs and outpatient visits in Medicare to limiting cost growth in Medicare Advantage plans.

24

As the federal government will pay for 50% to 78% of Medicaid costs through federal match in

2019 (65% in Missouri)

25

, federal spending on Medicaid is similarly assessed for cost reduction

opportunities: CMS has announced its intention to increase the level of scrutiny of Medicaid

waiver expenditures.

26

In addition, CMS has described its intention to increase audits of state

claims for federal matching funds and beneficiary eligibility determination, among others.

27

Public and private payors are migrating to value-based payment

There is a broad consensus that one of the key drivers of waste and inefficiency in U.S.

healthcare is the fee-for-service (FFS) payment model that characterizes most provider

payments. FFS stimulates volume rather than coordination of services, and there are no

inherent incentives to achieve optimal outcomes nor to deliver care in an efficient manner.

28

Both public and private payors are transitioning from FFS to value-based payment (VBP), using

Alternative Payment Models (APMs) to reward providers for delivering high-quality care at lower

cost. Research suggests that well-designed APMs improve the quality of care and can

meaningfully reduce the cost of care if implemented across the full spending base.

29

PROJECTED SPENDING WITHOUT SIGNIFICANT COURSE CORRECTIONS

Over the last 10 years, Medicaid spending growth has outpaced growth in state general

revenues. For example, in 2009, 17% of state general revenue funds were directed toward

Medicaid; however, in the wake of the Great Recession, Medicaid grew to 22% of state general

revenue by 2012 and, in 2018, reached 24% (see Exhibit 7). Although Medicaid enrolment has

fluctuated over this timeframe, total Medicaid spending growth has outpaced growth in state

general revenues when measured over any five-year timeframe, due to the increase in spending

per participant enrolled in the program. Notwithstanding reductions in Medicaid enrollment

observed since the beginning of SFY2019, program spending is likely to occupy a greater share

of state general revenue over the coming five years, absent changes in program performance.

In this section, we consider three scenarios as a method for gauging the level of fiscal pressure

that may arise from Medicaid spending growth. In Scenario 1, Medicaid spending as a share of

state general revenues continues to grow at a pace similar to the last five years; in Scenario 2,

24

CMS, “CMS-1695-P: Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment- Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM),” 2019,

see: www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/HospitalOutpatientPPS/Hospital-Outpatient-

Regulations-and-Notices-Items/CMS-1695-P.html; CMS, “Prior Authorization and Step Therapy for Part B Drugs in

Medicare Advantage,” 2018, see: www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-

Plans/HealthPlansGenInfo/Downloads/MA_Step_Therapy_HPMS_Memo_8_7_2018.pdf.

25

The percentage varies by state; for Missouri the match rate in FY2019 is 65.4%.

26

CMS, “Budget Neutrality Policies for Section 1115(a) Medicaid Demonstration Projects,” 2018, see:

www.medicaid.gov/Federal-Policy-Guidance/downloads/SMD18009.pdf.

27

CMS, “CMS announces initiatives to strengthen Medicaid program integrity,” 2018, see:

www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-announces-initiatives-strengthen-medicaid-program-integrity.

28

Health Care Learning and Action Network, "Alternative payment model (APM) framework. Updated version 2017,"

2017, see: hcp-lan.org/workproducts/apm-refresh-whitepaper-final.pdf.

29

McKinsey, “The seven characteristics of successful alternative payment models,” 2019, see:

www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/the-seven-characteristics-of-

successful-alternative-payment-models.

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

14

an economic downturn accelerates the growth of Missouri Medicaid spending while reducing the

growth of state general revenue; in Scenario 3, the trends from Scenario 1 are exacerbated by

potential changes in CMS policies that would reduce federal revenue for Missouri.

EXHIBIT 7: MEDICAID SPENDING AS PERCENT OF GENERAL REVENUE, SFY2009-23

30

Scenario 1—Continuation of Recent Trends: Spending on the program increased from 21%

of state general revenue in 2013 (36% of total state spending) to 24% (40% of total spending) in

2018.

31

In the first scenario illustrated in Exhibit 7, the assumption is that growth of both

Medicaid spending and total state spending continue at the pace observed over these past five

years. Under this scenario, total Medicaid spending would increase to $12.8 billion by 2023,

while the state’s total spending would grow to $29.2 billion (growing 2.5% annually) by 2023. In

2023, Medicaid spending would comprise 44% of the overall state spending and 26% of state

general revenues.

Scenario 2—Potential Impact of Economic Downturn: In the second scenario, a severe

economic downturn (comparable to the recession that began in 2008) affects both state general

revenues and Medicaid enrollment. Based on analyses by Moody’s, an economic downturn

occurring within the next four years could reduce total general revenue by approximately 12%

over a two-year period. This reduction in general revenue will likely coincide with an increase in

Medicaid enrollment, as individuals lose jobs and incomes fall, resulting in an estimated

increase in Medicaid spending by 1.9% in total over the course of two years.

32

These changes

could translate to Medicaid spending growing to comprise 51% of total state spending and 30%

of state general revenues in 2023.

30

Medicaid expenditures have continued to outpace economic growth. Missouri DSS: see note 1.

31

Missouri DSS: see note 1.

32

Moody’s, “Stress-Testing States,” 2017, see: www.economy.com/getlocal?q=91a42834-85af-4773-b408-

5da811028c00&app=eccafile.

24

31

27

19

25

28

26

29

18

30

0

20

21

22

23

21%

2009 22

23%

171411

20%

22%

13

28%

17%

1610

24%

12

21%

23%

15 2018 19

22%

30%

2023

Status quo

(Scenario 1)

Recession

(Scenario 2)

CMS policy changes

(Scenario 3)

19%

26%

21

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

15

Scenario 3—Potential Changes in CMS Policies: In the third scenario, no recession occurs,

but CMS policy changes could lead to reductions in federal funds for the state’s Medicaid

program and, consequently, to greater pressure on the state budget. A 3.5% drop in net federal

funds could reduce federal funding by approximately $200 million in SFY2023.

33

If the Medicaid

program’s total spending were to remain unchanged, the loss of federal funds may need to be

offset by a similar increase in funding from state general revenues. This could increase the

program’s share of state general revenues to 28% in SFY2023.

Savings needed to keep spending growth in line with State General Revenues

Under any of the scenarios described above, significant changes in the structure and

performance of Missouri’s Medicaid program would be necessary to bring Medicaid spending

growth in line with projected economic growth of the state. Following are estimates of the

reductions in Medicaid program spending that would be necessary to maintain spending at 24%

of state general revenues through SFY2023, under each of the three scenarios.

• In Scenario 1 (continuation of recent historical trends), Missouri would need to reduce the

growth rate of Medicaid spending by approximately 2 percentage points to bring it in line

with the growth of state general revenue, to maintain spending at 24% of state general

revenue. In SFY2023, this would equal approximately $735 million savings to total

Medicaid spending, or approximately $260 million savings to state general revenues.

• In Scenario 2 (occurrence of a recession similar in magnitude to that experienced 10 years

ago), it would be necessary to reduce Medicaid spending by nearly $1.7 billion, or $590

million in spending from state general revenues, to maintain spending at 24% of state

general revenues.

• In Scenario 3 (continuation of historical trends, exacerbated by CMS policy changes), it

would be necessary to reduce total program spending by approximately $1.3 billion, or

$460 million in spending from state general revenues to maintain spending at 24% of state

general revenue.

34

The funding gap implied by the above scenarios is meant to provide context for understanding

the estimated $0.5 billion to $1.0 billion in cost savings associated with the opportunities and

potential initiatives detailed in the pages that follow. Maintaining spending at 24% of state

general revenues may not necessarily represent the state’s policy objective and may not be

feasible in all future scenarios. In all scenarios, however, implementation of initiatives such as

those outlined in the pages that follow could help the Medicaid program to reduce fiscal

pressure on the state budget while maintaining or improving access to high-quality care, without

broad-based cuts in provider rates, or reductions in eligibility or covered services.

33

As outlined in the section on acute care services, existing risks to the state’s federal match revenue exist (e.g.

inpatient UPL calculations, planned federal reduction of DSH payments, DSH payments-related legal

developments, federal scrutiny of existing provider tax pooling arrangements, federal initiatives to reduce the

provider tax safe harbor, and so forth). $200 million is a low estimate of the impact of any combination of two to

three of these risks becoming reality.

34

Assumes a corresponding $120 million decrease in provider tax and $80 million decrease in other cuts to federal

funding (e.g., DSH payments). The savings would bring the percentage of Medicaid spending of state general

revenue to SFY2018 levels.

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

16

Opportunities and Potential Initiatives

Without significant changes, Medicaid spending may increase from 24% of state general

revenues in SFY2018 to comprise 26% to 30% of state general revenues by SFY2023.

Significant cost savings would be necessary to bring growth of Medicaid spending in line with

the level of economic growth of the state, while preserving access to care for participants.

The Missouri Department of Social Services, MO HealthNet Division (MHD) commissioned a

rapid, in-depth independent assessment of its programs and operations to identify potential

opportunities and strategies to transform the Missouri Medicaid program, including evaluation of

which functions the Department is performing well in, what activities or practices could be

improved, and what priorities could be considered for future investment.

Overall, the Missouri Medicaid program is currently outdated in most aspects compared to other

peer states, and significant opportunities exist relative to industry best practices:

• Dollars spent in the program are not well aligned with value received from delivery system;

• Specifically, methods to pay providers lack incentives to contain costs or enhance quality;

• Approaches to utilization management; eligibility management; fraud, waste, and abuse;

and third-party liability are limited, partially due to the limitations of the MMIS (see below);

• Programs for special needs populations are fragmented;

• There is no substantial measurement nor transparency of outcomes of care; and

• Service levels to consumers and providers could also be improved, including reductions in

average wait times for handling questions, as well as increased service channels.

Leaders and staff in DSS, DMH, and DHSS are aware of these challenges and highly motivated

to modernize the program. However, the foundational operational capabilities to do so are

equally outdated, hampering opportunities for improvement: the existing technology

infrastructure (MMIS) is antiquated; data quality needed for program management is

suboptimal; and access to key management information is absent.

Detailed findings from the assessment conducted over the past several months are outlined in

the pages that follow, organized into eight project areas which collectively address sixteen

performance opportunities prioritized by DSS at the outset of this assessment. For each topical

area, potential opportunities for improvement have been identified and evaluated through

interviews with functional leaders and subject matter experts within the relevant departments,

analysis of claims- and non-claims data, review of activities and operations, assessment of

supporting infrastructure and analytics, and benchmarking against other state Medicaid

programs, Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs), or other private health insurers.

Based on these opportunities, a wide range of potential initiatives have been outlined for further

consideration by the Department. Depending on the selection of initiatives the state chooses to

pursue, total gross savings to the program (including federal and state share) could total up to

$0.5 billion to $1.0 billion by SFY2023. These estimated savings would be net of reinvestments

in the delivery system (e.g., in primary care, rural health, and the safety net; as well as rewards

for providers that generate savings under value-based payment models) and in the Medicaid

program’s operations to improve service levels to participants and providers.

35

35

One-time investments as well as MMIS replacement investments are not included.

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

17

Many of the opportunities for improvement could require changes in policies and contracts

requiring cooperation of local providers, support from the state legislature, and in some cases

federal approval. Potential initiatives outlined in this report are not meant to represent advocacy

for specific policies, nor conclusions yet reached by DSS. The state retains sole responsibility

for decision making over which of these potential improvement initiatives (or others) to pursue,

and in what form, in compliance with applicable laws, rules and regulations.

ACUTE CARE SERVICES

Missouri spent ~$4.2 billion in SFY2018 on acute care services, including hospital, clinic,

physician, and diagnostics services, across both the managed care and non-managed care

populations. Including pharmaceutical services, the total is ~$5.7 billion.

36

Hospitals are paid

through a combination of base rates and “add-on payments”, updated periodically based on

changes in hospital operating expenses. This approach offers minimal incentives for providers

to contain costs, making it an outlier among states. Uniquely, Missouri Medicaid makes add-on

payments to hospitals for services provided to non-Missouri, non-eligible residents.

Physicians and behavioral health providers are also paid per service (fee-for-service [FFS]).

Compared to other states, physicians’ reimbursement is low. Also, total spending on non-

hospital acute care services (physicians, Federally Qualified Health Centers [FQHCs], clinics,

and rural health services) is lower than other, comparable states.

The overall value of care delivered (dollars spending vs outcomes for participants) varies

significantly across counties. In general, >15% of Missouri Medicaid acute care expenditures

may be associated with potentially avoidable exacerbations and complications (PECs), which

includes costs of PECs associated with the prevention and treatment of opioid use disorder

(OUD). In addition, 5% to 10% of expenditures may be associated with inefficiencies, such as a

site of service or choice of therapy that might be more expensive without adding quality.

37

Potential initiatives to improve incentives and reduce costs range from adjusting rate setting

methodologies, moving to value-based payment models and investing in the rural and safety net

heath care infrastructure, including primary care and behavioral health. In total, the impact of the

acute care initiatives could range from $250 million to $500 million, net of potential

reinvestments in the delivery system, depending on the state’s choices.

38

To achieve the higher

end of this range, the state may need to pursue a combination of initiatives, striking the balance

between initiatives primarily focused on rates with initiatives focused on value-based payment

(VBP) and investments.

The state could build on its providers’ broad experience with Medicaid, Medicare, and

Commercial Alternative Payment Models (APMs). Missouri has significant experience with

Patient Centered Medical Homes (PCMH) and Health Homes in Medicaid, which aim to

integrate physical, behavioral, and substance use disorder (SUD) care for patients with, or at

risk of, multiple chronic conditions.

36

Pharmaceutical services are discussed in a separate section. The projected savings are not likely to overlap

between these sections.

37

Analysis of Missouri Medicaid claims data, SFY2016-18.

38

Analysis of Missouri Medicaid claims data, SFY2018; Interviews with Medicaid program staff and analysis of state

data, 2018.

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

18

This section will first describe the current reimbursement methodologies and the experience

with and impact (where quantifiable) of VBP models in Missouri. Subsequently, it will highlight

the opportunities to bend the cost curve and improve the value of care for Missourians and

present an associated range of initiatives.

Current situation

This section gives an overview of Missouri’s current methodology of hospital outpatient

reimbursement, inpatient reimbursement, utilization management, out-of-state payments,

hospital tax, physician reimbursement, behavioral health reimbursement, and acute care value-

based payment initiatives.

Population served, and services provided

For Medicaid, the providers discussed in this section serve both the managed care population

(children, parents, and pregnant women) as well as those participants in the disabled population

that are not dually eligible.

39

Exhibit 8 shows the breakdown of the total Medicaid costs by

service for these populations.

EXHIBIT 8: BREAKDOWN OF ACUTE CARE COSTS BY SERVICE CATEGORY, SFY2018

40

In the managed care population, costs are driven by mental illness diagnoses (including

substance use disorders) and by perinatal care (pregnancy care, delivery, post-delivery care,

39

Dually eligible participants receive their acute care services through Medicare.

40

Analysis of Missouri Medicaid claims data, SFY2016-18; does not include beneficiaries who have no eligibility

during any given month, as well as beneficiaries who are dually eligible or have third party liability; beneficiaries

may overlap across categories.

240

Radiology

Hospital inpatient care

Office and clinic care

12

ED care

Hospital outpatient care

Specialty pharma

Ambulance and transportation

Lab and pathology

Prescription drugs

550

Ancillary services

DME and supplies

PT/OT/ST

19

55

Other locations

Other types of care

1,166

1,488

517

709

484

65

66

273

130

Hospital

and ED

Total spend = $ 5,683M

SFY2018, $M

Diagnostics

Other

Total acute care spend,

$M

Share of total

acute care

spend

Average beneficiaries,

000

Share of total

acute care

beneficiaries

Total pop = 1,173K beneficiaries

383

370

139

45

408

762

419

753

103

262

24

21

172

130

Acute care service category

2%

11%

10%

15%

4%

32%

20% 12%

12%

36%

8%

66%

26%

65%

1%

9%

1%

33%

1%

23%

0%

2%

5%

4%

9%

35%

0%

2%

Office

Pharma-

ceuticals

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

19

and newborn care) (see Exhibit 9). In the non-dual disabled population, mental illness

diagnoses drive more than one-third of the total costs, followed by cardiovascular diagnoses

(see Exhibit 10). In these exhibits, substance use disorders (including opioid use) are included

in the mental illness diagnostic category.

EXHIBIT 9: MEDICAL COSTS BY DIAGNOSIS GROUP FOR MANAGED CARE

POPULATION, SFY2018

41

41

Analysis of Missouri Medicaid claims data, SFY2016-18.

Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue

Injury and poisoning

Diseases of the nervous system and sense organs

Diseases of the digestive system

Mental Illness

Certain conditions originating in the perinatal period

3%

Complications of pregnancy; childbirth; and the puerperium

Diseases of the respiratory system

Congenital anomalies

8%

Diseases of the circulatory system

Endocrine; nutritional; and metabolic diseases and immunity disorders

Neoplasms

Other

18%

10%

11%

6%

6%

24%

3%

4%

3%

2%

2%

MANAGED CARE POPULATION

Medical spend by diagnosis groups for adult and child claimants, SFY2018

Percent of medical spend

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

20

EXHIBIT 10: MEDICAL COSTS BY DIAGNOSIS GROUP FOR NON-DUAL DISABLED

POPULATION, SFY2018

42

Inpatient reimbursement

For inpatient (IP) care, Missouri uses a hospital-specific per diem, based on historical cost

reports up to two decades old. The base per diem is not differentiated by type of services

provided nor patient characteristics. In SFY2018, $540 million of inpatient payments were paid

to hospitals. In addition, add-on payments are made. $817 million “direct Medicaid” add-ons

compensate providers for differences between the base per diem and trended costs as

determined by more recent cost reports. In addition, direct Medicaid payments help offset

provider tax payments.

43

Other add-ons include disproportionate share hospital (DSH)

payments ($759 million) and graduate medical education (GME) payments ($139 million) (see

Exhibit 11).

The state uses a vendor to manage utilization of inpatient services. The vendor conducts six

types of reviews: prospective (pre-admission), admission (initial), continued stay review,

retrospective (post-discharge), and ongoing validation reviews. All review determinations are

made using Milliman Care Guidelines

®

and pertinent medical information received from the

attending physician or hospital regarding the patient's condition and planned services.

42

Analysis of Missouri Medicaid claims data, SFY2016-18.

43

Missouri Foundation for Health, “Briefing Book for Missouri Medicaid,” 2016, see: mffh.org/wordpress/wp-

content/uploads/2016/04/Medicaid-Financing.pdf.

Medical spend by diagnosis groups for non-dual disabled claimants, SFY2018

Percent of medical spend

4%

Diseases of the circulatory system

Diseases of the respiratory system

Diseases of the nervous system and sense organs

1%

34%

13%

Mental Illness

Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue

Injury and poisoning

Neoplasms

Endocrine; nutritional; and metabolic diseases and immunity disorders

Diseases of the digestive system

7%

Congenital anomalies

Complications of pregnancy; childbirth; and the puerperium

Certain conditions originating in the perinatal period

Other

13%

6%

6%

7%

5%

5%

<1%

<1%

NON-DUAL DISABLED

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

21

MHD covers up to 24 hours of observation services, ordered for patients who require

significant periods of treatment or monitoring before a decision on admission is made. Only

one observation code per stay can be billed, capping the reimbursable portion to 24 hours.

Outpatient reimbursement

For outpatient (OP) FFS reimbursement, Missouri pays a percentage of charges for individual

services. The percentage is based on analysis of historical cost reports trended to the current

state fiscal year. Currently, the state is transitioning towards a Medicare-based outpatient fee

schedule model. In SFY2019, hospitals received $319 million in outpatient base rate payments.

In addition, add-on payments are made to further help offset provider taxes (these are included

in the “direct Medicaid” add-ons, see Exhibit 11).

44

The state uses a vendor to conduct prior authorizations for advanced imaging (CT/CTA,

MRI/MRA, and PET) and select cardiac procedures (cardiac nuclear medicine and cardiac

catheterization).

EXHIBIT 11: HOSPITAL REIMBURSEMENT BREAKDOWN, MEDICAID FFS, SFY2019

45

Provider tax

Like other states, Missouri taxes hospitals and uses these revenues to fund Medicaid and draw

down federal funds at the Missouri federal match rate of 65.4% (see Exhibit 4). Missouri’s

hospital tax rate is higher than most other states (greater than 5.5%).

46

Missouri compensates

44

Missouri DSS, “FRA 19-3 – 10 24 18 – FINAL,” 2019; UPL analysis, Missouri DSS, 2018-19.

45

Missouri DSS, see note 44; uses FY18 data for outpatient base rate payments.

46

KFF: see note 12.

Description and methodology

Add-on payment stream

Base reimbursement stream

540

319

817

759

OP base

IP base

139

Total FFS Medicaid hospital spend

(SFY 19), USD, millions

Graduate

Medical

Education

(GME)

payments

Direct

Medicaid

payments

Direct

Medicaid

payments

Inpatient

base rate

payments

Outpatient

base rate

payments

Dispropor-

tionate

Share

Hospital

payments

Graduate

Medical

Education

payments

▪ Per diem payments for inpatient services

▪ For a given hospital, per diems are the same regardless of diagnosis or type of care

(“single per diem”)

▪ Per diems built off cost reports from the time the hospital enrolled. They are not trended

over time, regardless of changes to patient or service mix

▪ Payments for outpatient services

▪ Rates for each hospital are calculated as a percentage of billed charges

▪ The payment percentage is based off historical cost-to-charge ratios, trended forward to

current year

▪ Outpatient rates are trended over time based on updated cost reports

▪ Payments to compensate for costs not covered by per diem (see below), including

– Compensation for FRA payments (i.e., provider tax payments)

– Payment for difference between per diem and trended costs (based on cost-reports)

▪ Decreases in inpatient base rates will increase Direct Medicaid payments to compensate

for the increased difference between per diem and trended costs

▪ Payments to compensate for costs of care to uninsured individuals, distributed proportionally

to hospitals based on total uncompensated care

▪ Payments to compensate for costs associated with offering medical education through

residency programs

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

22

hospitals for these Federal Reimbursement Allowance (FRA) payments through the FFS add-on

payments. To attempt to make the tax closer to budget neutral for hospitals, the Missouri

Hospital Association (MHA) operates a pooling mechanism (see Exhibit 12).

47

Since 2017, when managed care was implemented statewide, the state includes a portion of

add-ons (primarily to offset provider taxes) in the managed care capitation rate. Through a

Memorandum of Understanding, the MCOs and the MHA have agreed to uphold efforts to

compensate hospitals for their costs attributable to the FRA assessment.

48

EXHIBIT 12: MISSOURI HOSPITAL ASSOCIATION FRA FUNDING POOL

49

Physician reimbursement

Physicians are reimbursed through a fee schedule based on a percentage of what Medicare

pays for the same services. Once fees are set (e.g., when fees are initially calculated as a

percentage of Medicare’s rates for a certain procedure code), they are static until the state

legislature changes them. Physicians who are organized in clinics can bill the services provided

47

Missouri Hospital Association, “How the FRA funds are used,” 2014, see: web.mhanet.com/FRA%20Tutorial.pdf.

48

MHA Management Services Corporation, “MSC Health Plan MOU and Amendment,” 2017.

49

Missouri Hospital Association, “Missouri’s Hospital Provider Tax Pooling Arrangement,” 2016, see:

web.mhanet.com/article/4387/Missouri8217sHospital-Provider-Tax-Pooling-Arrangement.aspx?articlegroup=2663.

Missouri DSS: see note 1. KFF: see note 12.

FRA assessed at

~5.50% of each

provider’s adjusted

net revenue (both

IP and OP, Medicaid

and non-Medicaid)

Tax collection

and matching

Reimbursement to

hospitals

Hospitals are

compensated for FRA

payments primarily

through Direct

Medicaid add-on

payments

State paid federal

matching funds

at 65.40%

Provider

participates

in a MHA

pool?

Provider

keeps full

add-on

payment

Provider

receives more in

payments from FRA than

it pays in FRA (pool

contributor)?

Provider

transfers FRA-

funded

payments to

pool operated

by MHA

To net out the FRA paid with the payments received,

MHA reimburses providers that receive less in FRA-

funded payments than they pay (pool recipients)

After payment to pool recipients, MHA returns remaining

funds in central account to pool contributors

Pooling of FRA funds

Yes

Provider waits

for pooling

and

redistribution

of payments

Yes

No

No

MOU b/t MHA and MCOs: agreed to

uphold attempt to compensate individual

hospitals FRA-related gains and losses

for payments within Managed Care

Intention of

voluntary MHA

pooling arrangement

is participation of all

FRA paying

hospitals

FRA funds approximately 33% of the Missouri Medicaid program:

$1.2B collected from providers with additional $2.2B in federal match

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

23

through their clinics, for which reimbursement rates are generally higher than they are for

physicians.

Behavioral health reimbursement

Behavioral health services are covered by both DMH and MO HealthNet. DMH covers

Community Psychiatric Rehabilitation services, which include intake and annual evaluations,

behavioral health assessment, psychosocial rehabilitation, and day treatment for youth.

50

DMH

also covers Comprehensive Substance Treatment and Rehabilitation (CSTAR) services. MO

HealthNet covers other behavioral health services, such as various psychotherapy services

(e.g., family and group therapy, individual psychotherapy), services in a school setting, applied

behavioral analysis, and selected telehealth services, among other covered services.

51

Behavioral health services not covered by Medicaid include housing supports, drug screens,

transportation, and occupational therapy for adults. Behavioral health services are reimbursed

on a fee-for-service basis, determined by relevant information (e.g., charge information from

providers across the state, recommendations from the State Medical Consultant) and current

appropriated funds.

Value-based payment (VBP)

There is significant experience with VBP in the state, both within Medicaid and across other

payors, although many of these models are not yet fully mature or at scale. The initiatives in

Medicaid are primarily focused on PCMHs and health homes (both within the FFS and through

the managed care local community care coordination program [LCCCP]), through which

providers may receive additional payments to improve the value of the care delivered. The

impact of some initiatives can be quantified.

• Local community care coordination program (LCCCP). Missouri contracts require MCOs to

develop a LCCCP to be approved by the state in which MCOs are to develop VBP

contracts (such as ACOs, PCMHs, primary care case management programs [PCCM])

with providers. Provider participation should have reached 10% in June 2018, with 20% of

participants enrolled in the LCCCP by the end of the contract period. The program has

recently started; no results are yet available.

• Accountable care organizations (ACOs). In addition to the LCCCP initiatives, there are at

least 13 ACOs in Missouri, concentrated in St. Louis, Kansas City and Springfield, of which

11 are Medicare ACOs, and two are commercial ACOs. The six Medicare ACOs for which

the number of participants has been published jointly serve >184,000 Missourians. At least

three of these ACOs have risk-based contracts; one reported $8.9 million in earned

savings in 2017.

52

• Patient-centered medical home (PCMH). There are currently 419 NCQA accredited

PCMHs in Missouri,

53

contracting with MCOs through the LCCCP program and with

commercial plans. Fifty-three practices participate in CMS’ Medicare Comprehensive

Primary Care Plus Initiative (CPC+), in which Blue Cross Blue Shield of Kansas City and

50

MO HealthNet Community Psych Rehab Program Manual.

http://manuals.momed.com/collections/collection_cpr/print.pdf.

51

MO HealthNet Behavioral Health Services Manual. http://manuals.momed.com/collections/collection_psy/print.pdf.

52

CMS, “Shared Savings Program Accountable Care Organizations (ACO) Public-Use Files,” 2017, see:

www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Downloadable-Public-Use-Files/SSPACO/index.html.

53

National Committee for Quality Assurance, “Practices,” see: reportcards.ncqa.org/#/practices/list?state=Missouri.

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

24

UnitedHealth also participate; these practices receive care management fees and quality-

and efficiency bonus payments. No Missouri-specific results have been published.

• Health homes. Missouri was one of the first states to create health homes. Health homes

must meet specific quality criteria and receive a per member per month (PMPM) payment

for care management and other dedicated health home services. Primary care health

homes (PCHH) focus on patients with at least two physical chronic conditions, such as

diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or substance use disorder. As of 2017, PCHHs received

$63.72 PMPM for health home services; of the 38 PCHHs, 25 are federally qualified health

centers (FQHCs), 11 are hospital affiliated providers, and two are clinics. In 2018, 24,580

Medicaid participants were receiving care from PCHHs. According to evaluations published

by the state, PCHHs saved $98.35 PMPM, compared to baseline in 2016 (see Exhibit

13).

54

Lower actual and risk-adjusted PMPM costs for the PCHH population are partially

driven by lower inpatient costs (see Exhibit 14).

55

EXHIBIT 13: IMPACT OF PRIMARY CARE HEALTH HOMES: HOSPITAL USE, SFY2012-18

56

54

Missouri DSS, “Paving the way,” 2017, see: dss.mo.gov/mhd/cs/health-homes/pdf/pchh-paving-the-way.pptx;

Missouri DSS, “MO HealthNet PCHH Progress Report 2014-2017 FINAL 07192018,” 2018, analysis of Missouri

Medicaid claims data, SFY2016-18.

55

Analysis of Missouri Medicaid claims data, SFY2016-18.

56

Missouri DSS: see note 54.

Percentage of PCHH enrolees who had a hospitalization, %Percentage of PCHH enrollees who had an ED visit, %

87

63

41

39

23

17

12

Yr 5Yr 2 Yr 3BL Yr 6Yr 4Yr 1

58

35

24

17

14

11

8

Yr 3Yr 1 Yr 4BL Yr 2 Yr 5 Yr 6

4.7

0.5

BL Yr 1 Yr 2 Yr 6Yr 3 Yr 4 Yr 5

1.5

0.8

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.3

0.2

Yr 3BL Yr 1 Yr 2 Yr 5Yr 4 Yr 6

In total, the percentage

of high utilizers who are

admitted to the hospital

has been reduced by

86%.

The average number of

hospitalizations has

decreased by 87 % from

baseline to year six.

The impact of PCHH on ED and hospital use has been especially effective among high utilizers

There has been an 86%

decrease in ED visits for

individuals who are

considered to have high ED

or hospital utilization.

The average number of ED

visits decreased from 4.7

visits per person to less than

one visit/person by year six,

an 89% decrease.

% of high utilizers with ED visits % of high utilizers with hospital admissions

Average # of ED visits for high utilizers Average # of hospitalizations for high utilizers

43

37

32

31

31

30

28

Yr 4Yr 1BL Yr 3Yr 2 Yr 5 Yr 6

25

21

20

17

22

23

20

Yr 4Yr 3BL Yr 6Yr 1 Yr 2 Yr 5

There has been a 35%

decrease in ED use for all

PCHH enrollees from

baseline, through year 6 of

the PCHH program

There has been a 20%

decrease in hospital use

from the baseline,

through year six of the

program.

Utilization results across all PCHH enrollees

Utilization results across high utilizers

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

25

EXHIBIT 14: COMPARISON OF EXPENDITURES IN PCHH PROGRAM WITH NON-PCHH

PARTICIPANTS WITH COMPARABLE RISK-PROFILE (MANAGED CARE), SFY2018

57

Community mental health center health homes (CMHC HH) focus on patients with (serious)

mental illness and/or substance use disorder. CMHCs receive $85.23 PMPM to support the

infrastructure needed to deliver CMHC HH services; of the 28 CMHCs, 22 are clinics and six

are hospital affiliated providers (15 of these CMHCs have become certified community

behavioral health clinics [CCBHCs; see below]). As of January 2017, 24,844 participants

were enrolled in CMHC HH. An evaluation by the state concluded that in 2016, CMHC HHs

saved $284.94 PMPM compared to baseline (see Exhibit 15 for additional results).

58

To

compare participants served by CMHC HHs with participants with comparable conditions

and co-morbidities, individuals with high behavioral health needs were identified within the

CMHC HH population as well as in the non-HH population.

59

In this comparison, participants

in the non-dual disabled population show similar nominal PMPM costs but lower risk-

adjusted PMPM costs for the CMHC population. As in the PCHH analyses, these results

were driven partially by higher pharmacy costs and lower inpatient costs in the CMHC

57

Analysis of Missouri Medicaid claims data, SFY2016-18.

58

Missouri DMH, “DMH CMHC Healthcare Homes progress report,” 2016, see:

dmh.mo.gov/mentalillness/provider/docs/cmhchchprogreport16.pdf.

59

In these analyses, participants were flagged as having high behavioral health needs if they either (1) have

diagnoses of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder with psychosis, major depression w/ psychosis, attempted suicide or

self-injury, homicidal ideation, or substance use with pregnancy or one year postpartum OR (2) have one or more

behavioral health-related utilization of inpatient hospital visit, crisis unit visit, residential facility visit, rehab facility

visit, medication-assisted treatment, ED visit, or injection antipsychotics AND presence of bipolar disorder without

psychosis, major depression without psychosis, other depression, PTSD, substance use, conduct disorder,

personality disorder, psychosis, ODD, or eating disorders.

SFY2018

9%

8%

9%

10%

13%

20%

16%

13%

8%

7%

13%

34%

23%

5% 75M

1,447M

In PCHH

program

Not in PCHH

program

880

1,194

452

618

100,951

7,065

Ambulance and transportation Home and community-based

Other types of care

Ancillary services

DME and supplies

ED care

Hospital inpatient care

Hospital outpatient care

Specialty pharmaInstitutional care Treatment and evaluation at other sites

Lab and pathology

Office and clinic care

Physical, occupational, speech therapy

Radiology

Retail prescriptions

MANAGED CARE POPULATION

Spend by service category by HH enrollees, vs. comparable population

Total

members

included Breakdown of total spend

Risk-

adjusted

PMPM, $

Program

type

Actual

PMPM, $

Missouri Department of Social Services PREDECISIONAL

Rapid Response Review – Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program

26

population. This comparison could indicate that the CMHC is cost-effective, improving the

care for these patients (including utilization of needed drugs) and reducing potentially

avoidable hospital admissions (see Exhibit 16). (The results for the managed care

population, mostly children, did not show a comparable difference.)

EXHIBIT 15: IMPACT OF COMMUNITY MENTAL HEALTH CENTER HEALTH HOMES ON

HOSPITAL USE, SFY2011-2015

60

60

Missouri DMH: see note 58.

34%

28%

26%

22%

25%

45%

40%

34%

31%

31%

20

24

10

18

12

14

16

22

26