Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation

Special Study 3

Historical Office

Office of the Secretary of Defense

SEPTEMBER 2012

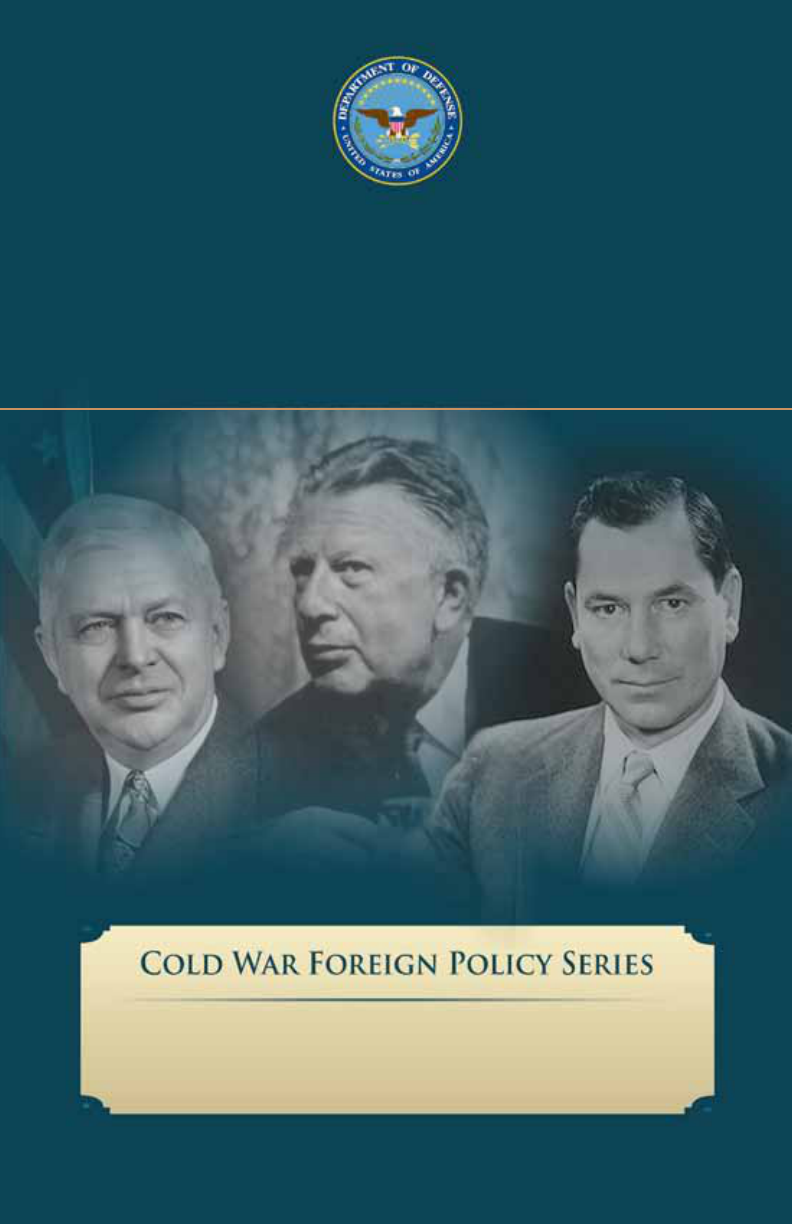

Charles Wilson, Neil McElroy, and Thomas Gates

1953-1961

Evolution of the Secretary OF Defense

IN THE ERA OF

Massive Retaliation

Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation

Cover Photos: Charles Wilson, Neil McElroy, omas Gates, Jr.

Source: Ofcial DoD Photo Library, used with permission.

Cover Design: OSD Graphics, Pentagon.

Evolution of the Secretary of Defense

in the Era of

Massive Retaliation

Charles Wilson, Neil McElroy,

and omas Gates

1953-1961

iiiii

Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation

Charles Wilson, Neil McElroy, and Thomas Gates

1953-1961

Historical Oce

Oce of the Secretary of Defense

September 2012

Series Editors

Erin R. Mahan, Ph.D.

Chief Historian, Oce of the Secretary of Defense

Jerey A. Larsen, Ph.D.

President, Larsen Consulting Group

Special Study 3

Evolution of the Secretary OF Defense

IN THE ERA OF

Massive Retaliation

Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation

viv

Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3

Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied

within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the

views of the Department of Defense, the Historical Oce of the Oce of

the Secretary of Defense, Larsen Consulting Group, or any other agency

of the Federal Government.

Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited.

Portions of this work may be quoted or reprinted without permission,

provided that a standard source credit line is included. e Historical

Oce of the Oce of the Secretary of Defense would appreciate a

courtesy copy of reprints or reviews.

Contents

Foreword..........................................vii

Executive Summary ...................................ix

Eisenhower, Wilson, and the Policy Process .................1

McElroy: Caretaker Secretary...........................18

Gates: Reasserting the Secretary’s Inuence ................23

Conclusion ........................................29

Notes.............................................31

About the Editors ...................................41

Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation

viivi

Foreword

is is the third special study in a series by the Oce of the

Secretary of Defense (OSD) Historical Oce that emphasizes the

Secretary’s role in the U.S. foreign policy making process and how

the position evolved between 1947 and the end of the Cold War.

e study presented here concentrates on the three Secretaries who

served President Dwight D. Eisenhower: Charles Wilson, Neil

McElroy, and omas Gates. e rst two of these Secretaries were

primarily caretakers and administrators, leaving much of the lead

role in American foreign policy making to Secretary of State John

Foster Dulles in this era of increasing foreign policy and national

security challenges. But omas Gates reinvigorated the role of the

oce in the last year of the Eisenhower Presidency, providing a

springboard for Robert McNamara, his successor in the John F.

Kennedy administration, to increase the power of the position to

unprecedented levels.

is study is not meant to be a comprehensive look at the Secretary’s

involvement in foreign aairs. But as a member of the President’s

cabinet and the National Security Council and as the person

charged with managing the largest and most complex department

in the government, the Secretary of Defense routinely participated

in a variety of actions that aected the substance and conduct of

U.S. aairs abroad.

is series of special studies by the Historical Oce is part of an

ongoing eort to highlight various aspects of the Secretary’s mission

and achievements. e series on the role of the Secretary of Defense

in U.S. foreign policy making during the Cold War began as a book

manuscript by Dr. Steve Rearden, author of e Formative Years,

1947–1950, in our Secretaries of Defense Historical Series. I wish

to thank Dr. Alfred Goldberg, former OSD Chief Historian, and

Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation

ixviii

Executive Summary

Despite the promising revival of the Secretary’s role in foreign

aairs during omas Gates’s tenure at the end of the Dwight

D. Eisenhower administration, the Eisenhower years were

predominantly a period in which administrative and managerial

matters took priority in Defense. is reected the personal

inclination of President Eisenhower, one of the nation’s best known

and most respected military leaders, who was superbly equipped

to give close attention to national security aairs. Concerning

themselves with the business side of the Defense Department—

the formulation and execution of budgets, the procurement of new

weapons and equipment, research and development—was perhaps

the soundest approach the rst two Secretaries of Defense under

Eisenhower, Charles Wilson and Neil McElroy, could have taken,

given their limited experience and the constraints under which

they operated. Yet in the long run, they did not serve as a model for

subsequent Secretaries.

e story of the three men—Charles Wilson, Neil McElroy, and

omas Gates—who bridged the gap between the early Secretaries

and the innovative and highly inuential Robert McNamara

shows an evolution in the role of the Secretary of Defense from

being principally administrative to having more involvement in

the making of foreign policy. Even in an administration with the

diplomatic prowess of President Dwight Eisenhower and Secretary

of State John Foster Dulles, two seasoned foreign aairs experts

and statesmen, the Defense Secretaries were able to make their

mark on policy as the Cold War continued to unfurl, tackling

the administrative hurdles of reorganization, austerity, and

Mr. Robert Shelala II of Larsen Consulting Group for their critique,

additional research, and helpful suggestions. anks also to Lisa M.

Yambrick, senior editor in the OSD Historical Oce, and to OSD

Graphics in the Pentagon for their eorts and continued support.

We anticipate that future study series will cover a variety of defense

topics. We invite you to peruse our other publications at <http://

history.defense.gov/>.

Erin R. Mahan

Chief Historian

Oce of the Secretary of Defense

Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation

xix

Secretary in December 1959. But his brief tenure (barely more

than 13 months) and his preoccupation with interservice matters

(particularly the strategic targeting dispute) did not permit him to

devote as much close thought and attention to foreign aairs as he

felt they deserved. Coming as it did at the end of the Eisenhower

administration, moreover, his period in oce saw a winding down,

not a launching, of new foreign policy initiatives.

What made the Secretary’s role in foreign aairs during this period

signicant, then, was less the direct inuence the Secretary himself

exercised and more the continuing growth of military power as a

key instrument of U.S. Cold War policy. Although Eisenhower’s

Defense Secretaries may not have been as signicantly involved in

decisions as Harry Truman’s had been, they and their subordinates

constituted an important part of a policy process that depended

heavily on the military’s contributions and assets. is became

evident in framing an overarching strategic policy under the

rubric “massive retaliation.” It was also clear in the management

of policy at the senior sta level, which Eisenhower entrusted to

an NSC refashioned to reect lines of command and authority

familiar to him from his military days. While Wilson, McElroy,

and Gates may not have enjoyed the prestige and inuence of

their immediate predecessors, their department had to respond to

increasing responsibilities for sustaining American foreign policy.

In the course of doing so, they set the stage for Robert McNamara’s

advent in 1961.

centralization while oering a more salient voice in discussions

of foreign aairs. As military matters became more important

throughout the 1950s, the views of the Secretary of Defense naturally

became more integrated into policymaking, especially through the

reworked policymaking structure of the National Security Council

(NSC). While Eisenhower’s rst two Defense Secretaries were

former businessmen without a background in foreign policy or

international relations, the defense background possessed by his

nal Secretary, coupled with Secretary of State Dulles’s departure,

allowed the Secretary of Defense to become more entrenched in

the making of foreign policy. In many respects acting as his own

Secretary of Defense, President Eisenhower reserved for himself

some of the key policy functions previously exercised by the

Secretary. Having served as Supreme Allied Commander in World

War II, Army Chief of Sta, and commander of North Atlantic

Treaty Organization (NATO) forces, he felt thoroughly qualied

to personally oversee national security aairs. As President, in

reaching decisions on strategy, force levels, weapons, and the like,

he either trusted his own instincts or consulted the Joint Chiefs of

Sta (JCS). For advice and guidance on foreign aairs, he generally

turned to his Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles.

Eisenhower’s executive style had the net eect of emphasizing

the role of Secretary of Defense as the manager of the Pentagon,

a role the President stressed upon entering the White House and

throughout his Presidency. ree Secretaries of Defense served

under Eisenhower: Charles Wilson, Neil McElroy, and omas

Gates, Jr. e rst two were highly successful former business

executives—Wilson as president of the automobile giant General

Motors, and McElroy as head of Procter and Gamble, a major

soap and household goods company. Both were able industrial

managers who knew a lot about running large organizations with

large budgets but comparatively little about foreign aairs or

national security. Gates, to be sure, fell into a somewhat dierent

category, having served as Under Secretary of the Navy, Secretary

of the Navy, and Deputy Secretary of Defense before being named

Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation

1xii

he 1952 Presidential election brought to the White House

Dwight D. Eisenhower, one of the nation’s best known and

most respected military leaders. His choice for Secretary of Defense,

Charles E. Wilson, had achieved notable success as a business

executive. Because Eisenhower was superbly equipped and inclined

to give close personal attention to national security aairs, the new

Secretary was expected to concentrate on defense management

rather than formulation of basic national security policy.

1

Wilson was still head of General Motors when Eisenhower

selected him to be Secretary of Defense in January 1953. Wilson’s

nomination sparked a major controversy during his conrmation

hearings before the Senate Armed Services Committee, specically

over his large stockholdings in General Motors. Although reluctant

to sell the stock, valued at more than $2.5 million, Wilson agreed to

do so under committee pressure. When asked during the hearings

whether, as Secretary of Defense, he could make a decision adverse

to the interests of General Motors, Wilson answered armatively

but added that he could not conceive of such a situation “because

for years I thought what was good for the country was good for

General Motors and vice versa.” Later, this statement was often

garbled when quoted, suggesting that Wilson had said simply,

“What’s good for General Motors is good for the country.”

Although nally approved by a Senate vote of 77–6, Wilson began

his duties in the Pentagon with his standing somewhat diminished

by the conrmation debate.

2

Eisenhower, Wilson, and the Policy Process

Wilson’s tenure proved crucial in setting precedents and establishing

procedures for those to follow. Aware from the outset that he would

have limited duties in making foreign policy, Wilson seemed

T

Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation

32

John Foster Dulles’s) major foreign policy positions, though he

was not so reticent as to avoid asking questions that would, as one

observer recalled, “sort of blow a proposition out of the water.”

6

Wilson’s views on foreign aairs, such as they were, understandably

lacked the mastery of detail and air of authority that characterized

Dulles’s thinking and certainly could not match the worldly

common sense that Eisenhower possessed. On those occasions

when Wilson ventured to oer an opinion in public, he sometimes

wound up causing Eisenhower considerable embarrassment—as

occurred in 1955, when Wilson suggested that the United States

had a weapon more horrible than the hydrogen bomb and that the

loss of the Chinese Nationalist–held islands of Quemoy and Matsu

to communist control would make little dierence to American

security.

7

e danger with Wilson, as one source close to the

President reportedly said, was twofold: whenever he “put his foot

in the mouth” and “what he did when he took it out again.”

8

ough often mocked and criticized, Wilson remained a steadfast

and reliable member of what amounted to Eisenhower’s board

of directors: the National Security Council. Given greater

prominence by Eisenhower, the NSC remained the heart of the

policy process throughout his Presidency. Outwardly, the changes

Eisenhower ordered—the redesignation of the Senior NSC Sta as

the NSC Planning Board, the appointment of a full-time Special

Assistant for National Security Aairs to oversee the NSC sta,

and the creation of an Operations Coordinating Board (OCB)

to assign responsibility for the execution of policy and to oversee

psychological warfare strategy—seemed relatively minor, aimed

ostensibly at improving the eciency and eectiveness of the

system.

9

But they also signaled Eisenhower’s clear intention to

infuse the policy process with a greater sense of order and purpose.

Consistent with a campaign pledge he had made, he resolved to

upgrade the NSC and make broader use of the body’s resources and

potential than Truman ever had.

10

genuinely glad to be spared the responsibility. He never pretended

to be knowledgeable about foreign aairs, nor did Eisenhower

expect him to be. e President wanted him instead to concentrate

on the managerial side of national security—in short, to be an

administrator. “Charlie,” he reportedly told Wilson at one point,

“You run defense. We both can’t do it, and I won’t do it. I was

elected to worry about a lot of other things than the day-to-day

operations of a department.”

3

Wilson proved ideal for what Eisenhower had in mind. According

to Emmet John Hughes, a speechwriter in the Eisenhower White

House, Wilson was the quintessential corporate executive—

“basically apolitical and certainly unphilosophic, aggressive in

action and direct in speech.” His appointment, Hughes maintained,

reected Eisenhower’s long-standing admiration of the business

community and his belief that success in business could be translated

into a capacity for government administration.

4

As his experience

as Secretary would show, however, the results were mixed. Although

loyal, hard-working, and generally capable as an administrator, he

may have proved too businesslike for Eisenhower’s taste. Moreover,

he was prone to rambling, exploratory discourses that left

Eisenhower feeling “discombobulated.” e more uncomfortable

Eisenhower felt, the less tolerant he became, even to the point of

practically denying Wilson access to the Oval Oce during the

waning days of his tenure.

5

Under Wilson there occurred little of the overt rivalry and

competition that had marred State-Defense relations o and on

during Harry Truman’s Presidency, especially during the brief Dean

Acheson–Louis Johnson period. ese tensions were also largely

absent during the interlude between Johnson and Wilson, while the

Pentagon was under the leadership of George Marshall and Robert

Lovett, two men with experience as leaders in both departments.

State-Defense dierences during Wilson’s tenure were more likely

to occur over policy choices than personalities. Even then, Wilson

was generally reluctant to challenge State Department’s (that is,

Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation

54

e appointment of a full-time Special Assistant for National

Security Aairs (or National Security Advisor, as the post became

more generally known) would prove to be one of Eisenhower’s most

signicant, enduring, and controversial legacies. In sharp contrast

to later years, when incumbents (especially Henry Kissinger in the

1970s) amassed and exercised extraordinary power and inuence,

the rst Special Assistant, Robert Cutler, and his immediate

successors, Dillon Anderson, William H. Jackson, and Gordon

Gray, operated under a restricted mandate that consigned them to

a low-key role. With the exception of Gray, none had expertise in

foreign aairs or defense policy. As conceived by Eisenhower, the

Special Assistant’s job was to expedite the ow of business, supply

the council with its agenda, preside over the Planning Board,

represent the President on the OCB, and monitor the work of the

NSC sta. ough the Special Assistant could from time to time

bring substantive matters to the President’s attention, he rarely

acted as a policy advocate.

11

ere can be no doubt that Eisenhower made extensive use of the

NSC. During his eight years in oce, the NSC held 346 regular

meetings, as opposed to 128 meetings during the NSC’s ve

years under Truman, and processed 187 serially numbered policy

papers, 67 of which were still current when Eisenhower stepped

down. e President typically presided and took an active part in

discussions at NSC meetings that lasted two-and-a-half hours or

more.

12

While President Truman had attended only 12 meetings

of the NSC, Eisenhower presided over 339 and missed only 29,

reecting the high priority he put on the council’s work.

13

Besides

the ve statutory members (the President, the Vice President, the

Secretaries of State and Defense, and the Director of Civil and

Defense Mobilization), Eisenhower insisted that the Secretary of

the Treasury and the Budget Director attend meetings as well,

functioning as “regular participant” members.

14

All involved could

bring aides and advisors, so that anywhere from a dozen to a score

or more people might be present.

15

Discussions, which centered on

policy papers worked up under the direction of the Planning Board,

often fell into a line-by-line examination of the contents. Yet for

all their faults and drawbacks, Eisenhower believed these meetings

to be eminently useful, both for hashing out problems and for

providing a mechanism through which “the members of the NSC

became familiar, not only with each other, but with the basic factors

of problems that might on some future date, face the president.”

Eisenhower felt that this experience helped him and his advisors to

get to know one another better and promoted closer consultation

and coordination, and that he was more likely to receive honest,

objective advice rather than self-serving recommendations.

16

e President wanted NSC members to participate in deliberations

as individual advisors rather than as representatives of their

respective departments or agencies.

17

But Wilson’s most active

involvement and greatest contributions, as might be expected, came

in connection with defense matters entailed in the annual reviews

of basic national security policy. Instead of targeting U.S. security

programs on a “year of maximum danger” as Truman had done,

Eisenhower wanted to minimize the country’s defense burdens

by sizing programs to meet the Soviet threat over the long term.

Accordingly, in the autumn of 1953, this approach was embodied

in a paper, NSC 162/2, that essentially guided the course of defense

policy through the rest of the decade. Known as the “New Look,”

the policy gave priority to strategic airpower and tactical nuclear

weapons, with diminished emphasis on maintaining large and

ready conventional capabilities.

18

Eisenhower did not doubt the

continuing importance of land and naval forces in the nuclear age,

but he felt that the need to conserve resources took precedence and

that, in any case, the atomic bomb was “simply another weapon in

our arsenal.”

19

It fell to Secretary of State Dulles, not the Secretary of Defense, to

provide the most memorable public rationale for the administration’s

national security thinking. Addressing the Council on Foreign

Relations in January 1954, Dulles sketched a blueprint for security

with “more reliance on deterrent power and less dependence on

Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation

76

local defensive power,” a concept that came to be known as the

massive retaliation doctrine.

20

is encouraged some military

planners to assume that fewer constraints might be placed on use

of the nuclear option. However, as early tests of this assumption

revealed during the Indochina (1954) and Quemoy-Matsu (1955)

crises, Eisenhower backed away when confronted with crossing the

nuclear threshold.

21

Nonetheless, the New Look and its corollary,

massive retaliation, remained the basic guides used by Wilson

and his successors for resource planning and allocation until the

Eisenhower administration left oce in 1961.

22

Although the NSC functioned well in hammering out long-range

plans and basic policy, its rather cumbersome and slow machinery

proved less suited for coping with unexpected day-to-day problems

of crisis management or sensitive diplomatic and intelligence

matters. Accordingly, when such occasions arose, Eisenhower

tended to respond by convening small informal meetings with senior

advisors in the Oval Oce. In such crises as Indochina, the Taiwan

Straits, and the Suez Canal, Eisenhower routinely met privately

with selected advisors, often after lengthy deliberations in the NSC,

to nalize decisions. ough Wilson normally participated in these

private sessions, his role was more to apprise the President as to

the availability and use of military assets than to comment on the

pros and cons of foreign policy. Eisenhower perceived a distinction

between diplomacy and national security policy. With Wilson’s

responsibilities concentrated on the Department of Defense

(DoD), his role as a manager outweighed his contributions as a

policy advisor.

23

Advice and Sta Support

Although probably not at the top of Wilson’s day-to-day agenda,

foreign aairs remained a necessary part of the Pentagon’s ongoing

business.

24

Containing communism, the number-one priority, was

a multifaceted task that involved DoD in a variety of functions in

support of American foreign policy. ese functions generally fell

into two categories. e rst included the responsibilities arising

from the increased U.S. presence abroad. e threat of communist

aggression required prior defense arrangements with U.S. allies,

including formal alliances such as NATO and the Southeast Asia

Treaty Organization (SEATO), access to overseas bases, and the

buildup, equipping, and training of allied forces under U.S. aid

programs. Accordingly, provisions had to be made with the host

countries for what Philip E. Barringer, a longtime OSD ocial in

the Oce of International Security Aairs (ISA), aptly described as

“keeping the machinery oiled properly,” to handle the inux of U.S.

military personnel, the administration and allocation of assistance,

the duties of U.S. advisors, and the negotiation of agreements

governing the status of forces, usually with ISA providing the initial

liaison and coordination.

25

e second category embraced a wholly new set of defense

problems arising from advances in military technology and

corresponding decisions by the President and the NSC on how to

exploit these advances. e advent of thermonuclear and tactical

nuclear weapons and ballistic missile technology raised problems

of unprecedented political complexity and diplomatic sensitivity.

Never before had any country possessed such enormous power

with so few guiding precedents on how to manage it. Some of

these new weapons would be deployed abroad and shared with

America’s allies. How much control, if any, the host country would

have in the storage, movement, and use of these weapons invariably

invited prolonged discussion, both within the U.S. Government

and between Washington and foreign capitals.

In trying to arrive at a Defense position on the many security

problems that arose, it soon became clear that Wilson depended

on his sta for advice and help more than any previous Secretary

of Defense. is dependence created numerous opportunities

for subordinates to make larger and more decisive inputs than

they had in the past. Accepting management and administration

as his primary tasks, Wilson heavily staed his oce with aides

Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation

98

and deputies from the business community, among them his rst

Deputy Secretary, Roger Kyes, like Wilson a former General Motors

executive and not inclined to show any great initiative in foreign

aairs. e burden of dealing with such matters fell, for the most

part, on ocials at the Assistant Secretary of Defense (ASD) level.

ough ISA ocials predominated, others participated as well,

including the OSD Comptroller’s organization, which became

routinely involved in NSC aairs because of a requirement that

each major policy paper include a nancial appendix.

26

Understanding the urgent importance of being able to deal with

problems abroad, in February 1953, Wilson encouraged President

Eisenhower to use the forthcoming Reorganization Plan No. 6 of

30 June 1953 to elevate the position of Assistant to the Secretary of

Defense (ISA) to the rank of Assistant Secretary (ISA). Later that

same year, also under Reorganization Plan No. 6, the Eisenhower

administration also abolished the Munitions Board and transferred

its international programs division to ISA, further consolidating

politico-military and economic aairs under one roof.

27

e

decision to elevate the ISA position to the Assistant Secretary level

(a move Lovett was on the verge of making when he left oce in

1952) was, to be sure, long overdue, but as a practical matter its real

signicance was to rearm the oce’s already well established place

among the Pentagon’s elite.

28

In 1956, Wilson went a step further

and tried to upgrade the oce to the rank of Under Secretary, but

legislation to eect the change died in the House Armed Services

Committee.

29

Besides requiring someone with a background and expertise in

foreign aairs, the ASD(ISA) position was also one of the most

politically sensitive in the Pentagon. e incumbent when Wilson

arrived, Frank Nash, wanted to step down for health reasons.

Wilson initially oered the job to Paul Nitze, director of the State

Department’s Policy Planning Sta since 1950 and a key gure in

the drafting of NSC 68. But because of his close association with

Acheson during the Truman years, he was persona non grata to

conservative Republicans in Congress.

30

Wilson hastily withdrew

Nitze’s name and persuaded Nash to stay on until February 1954

when he was replaced by Struve Hensel, a Forrestal protégé and

former Navy ocial. ree more Assistant Secretaries followed:

Gordon Gray (July 1955–February 1957), who left to become

President Eisenhower’s National Security Advisor, Manseld

Sprague (February 1957–September 1958), and John Irwin II

(September 1958–January 1961).

e high rate of turnover at ISA may be explained in part by the

demanding nature of the job. Although much of the ASD(ISA)’s

work still consisted of administrative matters arising from ongoing

programs (military assistance being by far the biggest and most

complex to administer), the ASD found himself increasingly

involved in substantive problems as well, particularly in connection

with NSC aairs. e key gure who oversaw most of the

necessary organizational adjustments, Gordon Gray, reorganized

ISA in 1956 on the basis of planning initiated by Struve Hensel.

He eectively divided the oce into two functional branches. In

one part Gray concentrated ISA’s military assistance and budget

responsibilities, organized around the Oce of Programming and

Control (which monitored the dispersal of grant assistance and

other aid) and the Oce of the ISA Comptroller (which reviewed

and prepared budget requests). Gray made policy matters the focus

of the other part of the organization. is contained the Oce

of Planning (including the ISA Policy Planning Sta), which

worked in conjunction with the military services, the Joint Sta,

and other agencies to anticipate their long-term security needs;

four regional directorates (for Europe, the Middle East and Africa,

the Far East, and the Western Hemisphere), which operated in

comparable fashion to the State Department’s country desks; and

the Oces of NSC Aairs and the OCB, which handled high-

level policy coordination. Problems that fell into neither of these

two general categories—such as economic matters, arms control

and disarmament, and international conference planning—were

assigned to the Oce of Special International Aairs, which

Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation

1110

was also charged with responsibility for security aairs relating

to the United Nations, NATO, SEATO, and other international

organizations.

31

Wilson made two major changes in ISA’s mission. One delegated

to the ASD(ISA) full authority and responsibility, as prescribed

under the Mutual Security Act of 1954, for the “development,

coordination, and establishment” of all policies, plans, and

procedures in the area of foreign military assistance, the aim

being to bring operational and administrative responsibility closer

together.

32

When the Military Assistance Program (MAP) started

in the late 1940s, the Secretary of Defense, through what was then

ISA, exercised little more than general policy supervision, leaving

operational control to the military services acting as “executive

agents.” e Secretary gave broad guidance to the services and

relied on spot checks by OISA to ensure compliance with overall

policy. With Wilson’s transfer of responsibility and authority to ISA

came greater involvement in the operational side of MAP, which in

turn increased ISA’s administrative duties and created new needs

for personnel with know-how in every phase of the operation.

33

e other important mission change related to the ASD(ISA)’s

involvement in high-level policy coordination and NSC aairs.

Although ISA had performed similar tasks in the preceding

administration, its coordinating function had been a relatively minor

part of its duties in view of Truman’s guarded use of the NSC and

regular direct contacts between Acheson and the Joint Chiefs after

the autumn of 1950. But with Eisenhower stressing primary reliance

on the NSC, with carefully laid-out procedures and channels,

more work needed to be done to coordinate Defense responses.

Accordingly, in April 1954, Wilson gave ISA “general supervision”

of all DoD activities relating to NSC aairs. At the same time he

appointed a Special Assistant for National Security Aairs who also

served as the Defense member of the NSC Planning Board. Initially,

the Special Assistant operated under the authority and supervision of

the ASD(ISA). But from Gray’s time on, the two jobs became one.

34

Increased authority for ISA was not without resistance. Its overall

control of politico-military aairs in relation to the military

services remained uid throughout the 1950s. Wilson never

imposed the strict discipline on outside contacts—particularly

with the State Department—that Secretary of Defense Louis

Johnson had demanded. In this eort Wilson received substantially

less cooperation from the military services than he expected.

Each service continued to maintain its own politico-military and

international aairs section that could be used for back-channel

contacts to circumvent the Secretary of Defense and his deputies.

e best organized for this purpose was within the Navy, which

regularly communicated directly with State through its Politico-

Military Policy Division. While ISA was responsible for policies

governing the programming of foreign military aid, it often

encountered resistance from the JCS and the military departments

when it attempted to probe the details of their recommendations

concerning program development and implementation practices.

35

Had Wilson taken a greater personal interest in foreign aairs,

some of these problems might have been avoided. But uncertain of

the Secretary of Defense’s involvement, the ASD(ISA) generally felt

constrained from pressing his authority too far.

36

JCS–OSD Relations

Even with the growing resources available to him through ISA,

the Secretary of Defense remained reliant on the Joint Chiefs

of Sta for all manner of help in dealing with politico-military

matters, especially the planning and analysis provided through

the Joint Sta (the JCS bureaucracy). Following the custom of

previous Secretaries of Defense, Wilson solicited advice from the

Joint Chiefs as a corporate body, but it also became increasingly

common for him to deal directly, if not exclusively, with the JCS

Chairman, Admiral Arthur Radford. As early as their rst meeting,

Radford impressed Wilson with his professional expertise and won

him over. From then on, Wilson looked to Radford not merely

for guidance in military matters but also for advice across a wide

Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation

1312

spectrum of policy problems having domestic and international

economic and political impact.

37

Radford recalled that when he accepted the invitation to

become Chairman, Eisenhower assured him that he would have

clearer responsibilities and greater authority than his immediate

predecessor, General Omar Bradley.

38

e National Security Act

of 1947 had made no provision for a Chairman, bestowing any and

all advisory duties as the President or the Secretary might direct

on the Joint Chiefs of Sta as a corporate body. When Congress

authorized the appointment of a Chairman in 1949, it included

him as a member of the JCS but failed to stipulate whether the

advisory responsibilities conferred upon his colleagues extended

to him as well. Although someone else might have treated this

as a minor oversight, the rst Chairman, General Bradley, felt

suciently inhibited to adopt an exceedingly narrow interpretation

of his advisory powers, especially where non-military matters were

concerned. Whenever he met with Secretary of State Acheson to

discuss an issue with foreign policy implications, Bradley invariably

prefaced his remarks with the caveat that he was speaking “from

a military point of view,” the implication being that it was up to

Acheson or the President to supply “the political point of view.”

39

A naval aviator with a distinguished record as a commander

in the Pacic in World War II, Radford was rarely so reticent

or circumspect. He had been a leader of the 1949 “revolt of the

admirals” against Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson’s cancellation

of the ush-deck supercarrier, the United States. Afterward, he

found himself, in eect, exiled to a succession of commands in

the Far East and Pacic. In 1953, Eisenhower brought him

back to Washington to preside over the JCS, a shrewd ploy on

Eisenhower’s part that helped to counter Navy criticism of the Air

Force–oriented New Look defense posture. In addition, Radford

had long advocated a more active policy in the Far East, a position

that appealed to both Dulles and those Republicans who felt that

the previous administration had concentrated too much on Europe

and not enough on Asia.

40

Personable, articulate, and adaptable,

Radford was one of the most politically astute senior ocers in the

armed forces at the time. ough not overly enthusiastic about the

New Look at rst, he was a longtime advocate of defense through

the exploitation of science and technology, the same approach

Eisenhower preferred. Soon, Radford metamorphosed into one of

the New Look’s most ardent supporters.

41

During his two terms as Chairman, from August 1953 to August 1957,

which overlapped closely with Wilson’s tenure as Secretary, Radford

enjoyed direct access to Wilson, Secretary of State Dulles, and President

Eisenhower.

42

Accordingly, it was not uncommon to nd him operating

in the forefront for DoD in foreign aairs matters, representing and

speaking for the Department in a manner that one might expect the

Secretary to do. For someone like Forrestal or Lovett, who preferred

to handle important foreign aairs issues themselves, Radford would

have been redundant, his presence probably an unwelcome nuisance.

But for Wilson he was a useful adjunct of the Secretary’s oce. at

the two got along exceptionally well made the job of collaboration that

much easier. Radford’s importance and inuence received a further

boost when the 1953 defense reorganization gave the JCS Chairman

management of the Joint Sta.

Defense-State Relations

e growing reliance on ready strategic forces and threats of massive

retaliation during the Eisenhower years brought about changes in

the traditionally accepted notions about spheres of responsibility in

foreign aairs. e more the administration’s foreign policy came

to rely on the threat of military sanctions, the more interested and

involved Defense became in formulating policy. e NSC became

a chief forum where Defense voiced its position on various foreign

policy matters. ough Wilson was essentially deferential to

Dulles, Defense-State relations remained, for all practical purposes,

institution-minded and fraught with recurring conicts below the

Secretary level.

43

Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation

1514

Some of the most highly documented State-Defense disagreements

occurred in connection with the annual NSC reviews of basic

national security policy. During the rst such exercise, held in the

autumn of 1953 to fashion what became the New Look, Dulles

stayed in the background, apparently not yet fully condent

of where he stood in relation to the President and his military

advisors. ough he exercised a strong conceptual inuence on the

resulting policy paper (NSC 162/2), he limited his involvement in

the particulars, especially military matters, to a handful of inputs

from State’s Policy Planning Sta.

44

A year later, however, Dulles was most vocal in the debate over a

follow-on paper (NSC 5501). e central issue concerned whether

the new paper should reect a more hard-line attitude toward

the Soviets, as urged by the Joint Chiefs and ISA, or the soft

line advocated by Dulles, who wanted more stress on diplomacy

and negotiations. Within ISA, dissatisfaction with U.S. policy

coalesced around Brig. Gen. Charles Bonesteel III, director of ISA’s

policy planning sta and the ranking Defense representative on the

NSC Planning Board, who was the most outspoken, articulate, and

inuential spokesman for the tougher line. Like the JCS, Bonesteel

and his ISA colleagues believed that time was running out for the

United States to reap substantial political and diplomatic benets

from its strategic superiority. ey argued that the United States

should adopt more risk-prone policies to leverage concessions from

Moscow.

45

Wilson initially endorsed the JCS–ISA position, but

Dulles’s opposition prevailed, and President Eisenhower endorsed

Dulles’s position.

46

Dulles took advantage of divisions within the Pentagon to

strengthen his own position, often siding with the uniformed

services. He assiduously courted the Joint Chiefs, particularly

Chairman Radford, with whom he shared an interest in paying

more attention to the Far East.

47

During the Taiwan Straits crisis

in the spring of 1955, Dulles talked tough about applying military

sanctions, including use of tactical nuclear weapons, unless the

Communist Chinese lifted their bombardment of Quemoy and

Matsu, even though he had campaigned vigorously against a JCS–

ISA hard line only a few months earlier.

48

is astonishing shift

in Dulles’s thinking prompted fears from Wilson that U.S. policy

was “underwriting a war in that area” and doing more “to heat up

the situation rather than cool it o.” To mitigate further tension,

Wilson urged the Secretary of State to wait 60 days “in order to

see what might develop.” Dulles, however, concurred with Radford

that diplomatic eorts “to cool o the situation” had failed and

that it was imperative to proceed on the assumption that military

sanctions might have to be applied sooner rather than later, lest

the Communist Chinese complete their buildup of invasion forces.

Although Dulles declined to endorse a specic military course of

action, he mentioned several times the importance of bringing “our

actions in line with our words” and of getting away from the habit

of “talking one way and acting another.”

49

Whether actually prepared to go as far as his rhetoric suggested,

Dulles cultivated the image of a no-nonsense diplomat who

understood the military viewpoint and stood ready to use military

force. is came out most clearly in a 1956 interview published in

Life magazine in which he claimed that U.S. threats to use nuclear

weapons had brought an end to the Korean War in 1953 and had

repeatedly deterred Soviet and Chinese Communist aggression

since then. Basking in the presumed success of his “brinkmanship”

diplomacy, Dulles hinted broadly that he would not hesitate to

threaten the use of nuclear weapons again should the need and

occasion arise.

50

In reality, Dulles remained extremely cautious about the use of

military power. But it was the impression he gave that mattered,

both in his public pronouncements and in his private dealings with

Radford and other military ocers. DoD leaders found common

ground with Dulles, perhaps given the Secretary’s reputation as one

of the administration’s “strong men” and his expertise in security.

51

Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation

1716

NATO Aairs

NATO provided the Defense Department a potential primary

focus for much of its strategic planning and military assistance

obligations. Wilson, however, had diculties coming to grips with

NATO from the beginning of his tenure. A quasi-isolationist at

heart (like many Republicans of his generation), he was aware of the

dangers that a Soviet-dominated Europe could pose to American

security but was still uncomfortable with the sizable numbers of U.S.

troops stationed there to honor U.S. commitments. He deplored

“the great cost of keeping these American divisions in Europe

indenitely.”

52

Yet each time he saw what might be an opportunity

to cut U.S. strength he encountered objections—typically from the

State Department, which claimed either that the moment was not

propitious or that the eects on European opinion would involve

“unacceptable political risks.”

53

Matters came to a head over the so-

called Radford Plan, leaked to the press in 1956, which projected

large-scale troop withdrawals from NATO Europe in conjunction

with an 800,000-man reduction in U.S. forces. When queried by

the press, State summarily denied that the United States had any

such intention, whereupon Wilson beat a hasty retreat, rst refusing

to conrm that the Radford plan existed, and then characterizing

the whole controversy as a misunderstanding growing out of a

hypothetical budget exercise.

54

As the level of U.S. troop strength in Europe typied, Dulles left

no doubt that the path of foreign policy power and inuence in

Washington ran through his oce in the State Department. ose

who thought to do business otherwise were invariably reminded

in no uncertain terms, as happened during negotiations with the

British in 1956–1957 to deploy U.S. intermediate-range ballistic

missiles (IRBMs) in the United Kingdom. Finding their own Blue

Streak IRBM encountering unexpected delays, the British Air

Ministry entered into preliminary talks in the summer of 1956

with U.S. Air Force representatives, who had previously asked to

base the new American or IRBM in the United Kingdom. e

United Kingdom was viewed by the Air Force and the JCS as an

ideal location to base the missiles, prompting the 1956 oer.

55

In October of that year, however, as the negotiations seemed

about to bear fruit, the Suez Canal crisis erupted, followed by the

Anglo-French-Israeli invasion of Egypt. e British and French

governments largely blamed lack of U.S. support for their eventual

withdrawal. Dulles chose to halt the IRBM issue pending a more

complete examination of other basing options and the restoration

of more harmonious Anglo-American relations.

56

A delay may have made sense to Dulles for diplomatic reasons, but

to Wilson it meant setting back the timetable for the entire IRBM

program at the risk of cost overruns and other complications.

57

Intent

on keeping the IRBM program on track, he used the opportunity

of a visit to Washington in late January 1957 by British Defence

Minister Duncan Sandys to try to patch up dierences between

Dulles and the British and to expedite the missile deployment.

Sandys and Wilson had worked together earlier on a 1954 scientic

exchange agreement that had been successful in establishing a U.S.-

U.K. joint scientic committee on ballistic missiles.

58

is time,

however, they faced a tougher set of problems. Resorting to an “end

run,” the British had Deputy Secretary Reuben Robertson put a

draft agreement before Eisenhower for his signature, but he found

the President averse to any immediate action.

59

By making the

British and the U.S. Air Force bide their time, Dulles eectively

demonstrated both his strong inuence in high-level defense

matters and his power to discipline wayward allies. is episode, a

setback for the IRBM program, was also a personal embarrassment

for Wilson. Ironically, when a deal nally was struck in March

1957 at the Bermuda summit between Eisenhower and Prime

Minister Harold Macmillan, it was Dulles rather than Wilson who

accompanied the President and was involved with the negotiating,

even though the agreement, subject to the resolution of numerous

details, encompassed the basic terms that Wilson and Sandys had

earlier discussed.

60

Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation

1918

Wilson did make one nal, important contribution to the IRBM

negotiations. is took the form of participating in an exchange

of letters with Sandys conrming the Bermuda agreement and

establishing broad terms for cooperative custody and control of

the missiles, the model for the dual-key approach that became the

standard throughout NATO in the 1960s.

61

Rarely was Wilson

enthusiastic about sharing U.S. nuclear technology with other

countries, even NATO allies. Nor, for that matter, was he a great

admirer of the British, whom he regarded along with the French as

great powers in eclipse.

62

As Secretary of Defense, however, he had

no choice on occasion but to put his prejudices aside. In one such

instance, the negotiations over the or missiles, Dulles rather than

the British gave him the most trouble.

McElroy: Caretaker Secretary

Wilson never intended to stay in oce more than four years. In

March 1957, he informed President Eisenhower that he would

resign as soon as the President could nd a successor. Finding a

replacement took longer than expected, causing Wilson to postpone

his departure until early autumn. On 4 October 1957, ve days

before Wilson’s successor, Neil McElroy, took oce, the Soviets

used rocket technology from their intercontinental ballistic missile

(ICBM) program to launch the rst Earth orbiting satellite, Sputnik

I. at stunning and ominous achievement overshadowed everything

else the Eisenhower administration did in foreign and defense policy

until its last day in oce.

63

Like Wilson, McElroy was a former business executive, highly

capable of managing a large, modern corporation but with no

prior experience in national security aairs. He informed President

Eisenhower from the outset that he did not intend to serve longer

than two years.

64

Considering McElroy’s unfamiliarity with the

problems of his new job and his lack of experience, it was hardly

surprising that he stuck closely to the policies, practices, and

personnel of his predecessor. He launched few initiatives, instead

describing himself as “captain of President Eisenhower’s defense

team,”

65

eagerly welcoming White House guidance and direction.

66

e launching of Sputnik I and a second Soviet satellite a month

later prevented McElroy from easing into his new duties as Secretary

of Defense. A favorite quip at the Pentagon, widely attributed to

General Nathan Twining, Radford’s successor as JCS chairman,

held that McElroy soared into oce with Sputnik and remained

in orbit thereafter.

67

To meet the concern generated by the satellite

launches, McElroy attempted both to clarify the relative positions

of the United States and the Soviet Union in missile development

and to speed up the U.S. eort. Placing considerable emphasis

on the IRBMs the United States then had under development,

McElroy argued that with proper deployment in overseas locations

they would serve as eectively as Soviet ICBMs. Without waiting

for completion of nal tests and evaluations, McElroy ordered

the Air Force or and Army Jupiter IRBMs into production and

planned to begin their deployment in the United Kingdom before

the end of 1958 and in Western Europe shortly thereafter. McElroy

also ordered accelerated development of the Navy solid-fuel Polaris

IRBM and the Air Force liquid-fuel Atlas and Titan ICBMs. In

February 1958, he authorized the Air Force to begin development

of the Minuteman, a solid-fuel ICBM to be deployed in hardened

underground silos, with operational status expected in the early

1960s.

68

e Soviet Sputnik launch in October 1957 also ignited a restorm

of criticism and argument about U.S. technology, budgets, and

DoD, thrusting the question of Defense reorganization into public

scrutiny. Sputnik developments oered President Eisenhower an

opportunity to make changes to the Department of Defense, and

he asked his new Secretary on 11 October 1957 to examine the

Defense structure with a view toward reorganization. e Defense

Reorganization Act of 1958 that emerged from a long process of

executive and legislative deliberation gave President Eisenhower

most of what he proposed. e act moved DoD further in the

Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation

2120

direction of centralization and unication through the following

provisions: strengthening the authority of the Secretary of Defense,

including greater control over the military departments; elevating

the status of JCS Chairman and eliminating the prohibition on

his having a vote in JCS decisions; almost doubling the size of the

Joint Sta; prescribing the establishment of unied and specied

commands by the President; stipulating the number of Assistant

Secretaries; and creating the position of Director of Research and

Engineering.

69

Although the 1958 Defense Reorganization Act did not address

the role of the Secretary of Defense in foreign aairs per se,

the legislation and DoD directives that owed from it greatly

increased Secretarial authorities that McElroy’s successors would

use creatively to expand their reach in national security aairs

writ large. e new legislation increased the responsibilities of the

Secretary of Defense, particularly in the operational direction of the

armed forces and in research and development. During McElroy’s

tenure, one immediate change was in the authority of the Assistant

Secretaries, including the ASD(ISA), to issue orders to the military

departments if authorized in writing by the Secretary of Defense.

is provision drew criticism from the service Secretaries who, seeing

their authority steadily erode, preferred a more limited assignment

of functions. Further bargaining produced a compromise under

which ISA would “establish” positions, plans, and procedures for

military assistance but merely “monitor” Defense participation in

NSC business and “develop and coordinate” all other aspects of

DoD involvement in politico-military aairs.

70

More signicant were changes that McElroy directed in ISA

administration of the military assistance program. e impetus

came from the ndings of the Draper Committee, a blue-ribbon

panel named by President Eisenhower in 1958 in response to

congressional complaints about the handling and policy objectives

of foreign military aid.

71

In its second interim report the following

year, the committee concurred with critics that there should be

closer collaboration between State and Defense and tighter

administrative control of MAP within the Pentagon. e committee

further recommended the appointment of a full-time director of

military assistance (DMA), who would be fully responsible for

the operation of the program under the ISA, and creation of an

independent evaluation sta.

72

Although the ASD(ISA) already

had a deputy for military assistance, the new position would

have broader authority and responsibilities, extending to policy

and operational aspects of the program and not merely nancial

recordkeeping. e Assistant Secretary for ISA, John Irwin II,

saw no immediate need for a change, but McElroy, deeming the

matter “urgent,” moved ahead with implementation of practically

the entire package of the Draper Committee’s recommendations,

though it was not until after he left oce that most of the reforms,

including the appointment of a DMA, took eect.

73

Although often preoccupied with administrative and budgetary

matters, McElroy was far from oblivious to the importance of foreign

aairs. A quick learner with a facile mind, he seemed genuinely

eager to overcome his limitations by nding out more about foreign

problems and foreign leaders. Yet he managed only four trips

abroad during his two years as Secretary and never acquired superb

diplomatic skills. When faced with dicult situations, he tended

to rely on the prestige of his position. us, while meeting in Paris

in December 1957 with French Defense Minister Jacques Chaban-

Delmas to discuss the possible deployment of U.S. IRBMs in France,

McElroy brushed aside French reservations and all but demanded

an early favorable French decision.

74

Assuming that eventually the

French would acquiesce, McElroy found his condence misplaced

as the French government rejected the presence of any U.S. missiles

on its territory.

75

As with his predecessor, McElroy found that the foreign aairs

problems most often engaging his attention were the annual NSC

policy reviews. Here, for McElroy, the problems of foreign policy

Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation

2322

and resource management came together in a way that he could

readily grasp. Interservice rivalry continued to bedevil the budget

process, as did dierences of concepts between State and Defense

over how and where to mete out resources to cope with emerging

threats. Although hardly new, the problem took on a somewhat

dierent appearance in the aftermath of Sputnik and what Dulles

saw as an approaching East-West stalemate in strategic nuclear

power. Henceforth, Dulles believed that eective foreign policy—

meaning the ability of the United States to retain its allies’ loyalty

and prevent defections to the Soviet bloc—would depend on the

capacity to wage “defensive wars” that would neither trigger an

all-out nuclear war nor “involve the total defeat of the enemy.”

is, he thought, pointed to the need for larger and more mobile

conventional forces, the kind of support provided by aircraft

carriers. Although JCS Chairman General Twining disagreed that

U.S. conventional capabilities for limited war were as decient as

the Secretary of State implied, he and McElroy both feared the

practical consequences of what Dulles was suggesting: namely, that

any expansion of conventional forces earmarked for limited war

would require either increased expenditures or a reallocation of

resources that would inevitably weaken the strategic deterrent.

76

Defense-State relations on the whole, however, remained

remarkably free from serious rifts during McElroy’s tenure. Because

of Dulles’s deteriorating health, his Deputy and eventual successor,

Under Secretary Christian Herter, with whom McElroy developed

a positive and productive working relationship, was playing an

increasingly key role at State. Open-minded about sta-level

contacts, McElroy raised no objection when Herter asked in May

1959 that State be kept “closely informed” on the status of military

planning during the Berlin crisis.

77

He later approved a State

Department request to participate in direct consultations with the

JCS on overseas base planning.

78

Keeping true to his intent for a two-year term, McElroy focused

almost exclusively on budgetary matters during his nal months in

oce and increasingly relied on aides and assistants for other issues.

He turned over to his Deputy, omas Gates, Jr., many of the

routine daily matters of running the Department, as well as heavy

foreign aairs responsibilities, including State-JCS discussions of

overseas base requirements, IRBM deployment, the simmering

Berlin crisis, readiness measures in relation to Communist China,

and contingency planning for limited war situations. Gates’s

intimate and visible involvement in foreign aairs marked a

signicant departure from the customary role of the Deputy.

79

Gates: Reasserting the Secretary’s Inuence

It was a foregone conclusion when Gates became McElroy’s Deputy

in June 1959 that he would succeed him. Gates’s credentials as one

of the emerging new generation of “defense professionals” were

unimpeachable—a background of active military experience and

more than six years in the Department of Defense. A Philadelphia

investment banker in private life, Gates had come to Washington

at the outset of the Eisenhower administration to serve as Under

Secretary of the Navy and since then had risen steadily in the

Pentagon hierarchy. Gates had interests and ambitions that went

beyond those of Wilson and McElroy, who typically concentrated

on management and administration. An increase in the Secretary’s

participation in foreign aairs matters would occur under Gates.

80

For President Eisenhower, as much as anything, choosing Gates

may have been a tacit admission that the job of Secretary of Defense

had become too big and complex for foreign policy amateurs.

Whatever Wilson and McElroy may have achieved, their lack of

background in foreign and defense aairs circumscribed their role.

After Dulles stepped down in April 1959 (he died the following

month), Eisenhower had to make new arrangements for help and

advice. Gates’s appointment thus served a dual purpose: it helped

to ll the void left by Dulles’s death, and it restored the Pentagon

to the care and supervision of a professional familiar with the inner

workings of defense and foreign policy.

81

Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation

2524

For Gates, as for his immediate predecessors, NSC aairs were a

top priority, but he believed that the council existed to serve the

President, not the Secretary of Defense. erefore, in his view, the

Secretary of Defense had an obligation to establish and sustain his

own network of interdepartmental contacts, most notably with

State.

82

Looking back, Gates estimated that he spent as much as

75 percent of his time on State Department–related business, and

he made a point of meeting privately every Sunday with Secretary

of State Herter.

83

“We have long realized,” he told the Jackson

Committee in 1960, “that the defense program cannot be prepared

in isolation.”

84

Although Wilson and McElroy would have had no

quarrel with this statement, their habit of deferring to State’s lead

while Dulles was alive had limited DoD inuence in the national

security policy process. Gates was more assertive. He insisted on

the following conception:

e relationship of State and Defense must be a partnership.

In years past, apparently, we had a system in the Defense

Department of reaction to State Department papers. State

Department wrote the policy; then we scurried around with

some very energetic, hard-working people and found a way

to react—usually 10 minutes before a meeting of the NSC. I

feel the Defense Department must also take the initiative in

providing counsel in politico-military matters. e Defense

Department must be a full partner of the State Department

in developing policy. e military point of view must be

expressed—and it can be expressed well by the dedicated

people who work at these things. We must participate in

creating policy rather than just reacting to papers written by

the State Department.

85

While Gates disavowed any desire to supplant the Secretary of

State as the President’s senior foreign policy advisor, his assertion

of coequal status struck some members of a Senate committee

as an unsettling departure from tradition and established

protocol.

86

In fact, Gates hoped to achieve not an assumption of

additional functions but rather a closer collaboration at all levels

of State-Defense relations that would yield more truly integrated

policies with less interdepartmental friction and parochialism.

Citing what he estimated to be several hundred separate daily

contacts—telephone calls, meetings, correspondence, and other

communications between State and Defense ocials—he saw a

growing trend toward “a common recognition on both sides of

the Potomac that most foreign policy issues have major defense

connotations, and conversely that even routine military activity

may have major foreign policy implications.”

87

Besides broadening State-Defense contacts, Gates tried to make

foreign aairs a more integral part of policy planning within the

Pentagon—for one, by including ISA in the budget process at a

point where ISA’s contributions would “put the foreign policy

implications into the budget earlier in the Pentagon planning than

it has been heretofore.”

88

is proved easier said than done. ISA’s

initial input, tendered in May 1960—a summary of politico-military

considerations bearing on the scal year 1962 Defense budget—

did little more than restate the obvious about American obligations

to NATO, the importance of a strong strategic retaliatory force,

and the value of eective capabilities for limited war. It did not,

as one might have thought, make any eort to correlate American

commitments abroad with the dollar costs of American defense;

nor did it venture to speculate on what new burdens to expect or

how existing obligations might be rendered more manageable. But

it provided a start for others to build on later, and that in itself was

an accomplishment.

89

As a pragmatist, Secretary Gates knew not to expect too much

too soon. Despite his advocacy of coequal status in foreign aairs,

there is little to suggest any substantial change in State-Defense

relations during his tenure. Whatever added inuence DoD may

have exercised, apart from its involvement in NSC aairs, tended

to be the result of the close personal and working relationship

Gates established with Herter, who was likewise eager to improve

Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation

2726

State-Defense contacts. Yet even with Dulles no longer around, the

initiative in foreign aairs remained as a rule with the NSC for

broad, long-range policy or with State in day-to-day operational

matters.

90

Although Herter saw the two departments making

progress on closer collaboration in planning, he also felt that much

remained to be done on State’s part to keep Defense better apprised

with political guidance, and for Defense to provide State with more

timely military advice.

91

Gates was fated to serve during the most troubled year of

Eisenhower’s presidency. e Cold War grew increasingly hot.

e bitter end of the Geneva test ban conference in December

1959 was followed by the disastrous breakup of the Paris summit

in May 1960 caused by the Soviet downing over its territory of

a U.S. U–2 reconnaissance aircraft. en came the unrest in the

Congo, signifying obvious Soviet readiness to sh in troubled

African waters; the rise of a pro-communist regime in Cuba in

the Caribbean backyard of the United States; and the steadily

worsening situation in Laos that raised the specter of U.S. military

intervention. With foreign policy problems emerging daily, Gates

selected carefully those to which he gave his personal attention, ever

mindful of the competing demands on his time.

92

His brief tenure

was absorbed by unusually dicult strategic policy problems,

including allegations that the Eisenhower administration was not

doing enough to close a purported “missile gap” with the Soviets,

and a strategic targeting controversy between the Air Force and the

Navy that led Gates in August 1960 to establish a Joint Strategic

Target Planning Sta (JSTPS).

93

e impetus in Gates’s mind for the creation of the JSTPS was the

inadequate coordination of targeting plans between the Strategic

Air Command (SAC) and the Navy, which he believed led to

redundancy and disputed priorities. ose dierences became

especially signicant with the advent of the Navy’s sea-based Polaris

ballistic missiles. Acting on a proposal by SAC Commander-in-

Chief General omas Power that SAC control strategic weapons

targeting, Gates set up JSTPS. e SAC commander, supported

by an integrated joint sta, assumed separate duties as director

of strategic target planning. When Chief of Naval Operations

Admiral Arleigh Burke objected to the new arrangement, Gates

encouraged him to argue his case before President Eisenhower, who

ultimately upheld Gates’s decision. By December 1960, the JSTPS

had prepared the rst Single Integrated Operational Plan, which

specied for various attack options the timing, weapons, delivery

systems, and targets to be used by U.S. strategic forces.

94

In foreign aairs, Gates proved especially adept in managing the

ow of business and in keeping small problems from getting bigger.

Having previously served in a variety of high-level positions, he was

generally acquainted with foreign leaders and their key advisors.

In particular, Gates enjoyed close relations with British Defence

Minister Harold Watkinson, with whom he directly negotiated

many of the details of the proposed Skybolt missile transfer and

access to base facilities for U.S. missile submarines at Holy Loch,

Scotland. Although the Skybolt missile system sharing issue, which

is beyond the scope of this study, would cause considerable trouble

for his successor, Robert McNamara, Gates was adept at keeping it

from becoming a source of Anglo-American contention during his

short tenure.

95

Gates had a strong hand in shaping Defense responses in

another crucial area of foreign policy area—arms control and

disarmament—where previously the Pentagon’s support and

endorsement had been barely lukewarm. Although Wilson and

McElroy had spent considerable time and energy studying arms

control proposals passing across their desks, they were forever

confronted by the unremitting skepticism and apprehension of the

Joint Chiefs, whose opinions on such matters carried considerable

weight both inside the Pentagon and on Capitol Hill. Since the

Chiefs knew that it was impossible for political reasons to keep

arms control o the national agenda, they focused their objections

instead on technical matters—the lack of adequate and eective

Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation

2928

verication measures, for example, or the harmful consequences

for current research and development. As delaying actions, these

arguments worked well against such popular proposals as a ban on

atmospheric testing and a cuto of nuclear production. But such

arguments wore thin after a while, giving DoD a reputation for

contentiousness.

96

Decidedly more inclined than his two immediate predecessors to

bring arms control and disarmament into the mainstream of American

defense policy, Gates readily acknowledged the “negative attitude” in

the Pentagon toward arms control. Prepared to entertain any and all

suggestions, he told Eisenhower that he had in mind appointing a

special assistant on disarmament matters.

97

Personally, Gates favored

a cuto of nuclear weapons production, preferably sooner rather than

later, not so much for disarmament purposes but to preserve what

he estimated as a two-to-one American advantage over the Soviets in

nuclear bombs and warheads. Moreover, he fully agreed with the Joint

Chiefs that arms control for its own sake was inherently dangerous

and that the administration should not allow itself to be stampeded

into reaching agreements merely because of public opinion.

98

Whether Gates could—and should—have been tougher with

the military on accepting the need for arms control is a matter of

conjecture. Gates himself, although more open-minded toward such

matters than Wilson and McElroy had been, remained very much

committed to the concept of foreign and defense policies resting in the

rst instance on ready military power rather than the negotiation of

agreements with one’s potential adversaries. Like Forrestal and Lovett,

he came from a generation whose view of international politics derived

from memories and experiences of the 1930s, when military weakness

and appeasement had seemed to invite aggression and oppression.

International communism, to Gates’s way of thinking, did not dier

from the Axis alliance of Nazi Germany, fascist Italy, and imperial

Japan in World War II. Despite rumors and diplomatic reports of

a growing Sino-Soviet rift, Gates remained convinced that there

existed no fundamental ideological dierences between Beijing and

Moscow and that U.S. foreign policy should treat such commentaries

with utmost caution. Such a hard-line Cold War viewpoint was not

uncommon or out of place for the time.

99

Conclusion

Despite the promising revival of the Secretary’s role in foreign aairs

during Gates’s tenure, the Eisenhower years were predominantly

a period in which administrative and managerial matters took

priority in Defense. is reected the personal inclination of

President Eisenhower, one of the nation’s best known and most

respected military leaders, who was superbly equipped to give close

attention to national security aairs. Concerning themselves with

the business side of the Defense Department—the formulation

and execution of budgets, the procurement of new weapons and

equipment, research and development—was perhaps the soundest

approach Wilson and McElroy could have taken, given their