PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS

A U.S. SECRET SERVICE ANALYSIS

OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE

U.S. Department of Homeland Security

UNITED STATES SECRET SERVICE

National Threat Assessment Center

2019

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/2019

National Threat Assessment Center

U.S. Secret Service

U.S. Department of Homeland Security

November 2019

This publication is in the public domain. Authorization to copy and distribute this publication in whole or in part is granted. However, the

U.S. Secret Service star insignia may not be otherwise reproduced or used in any other manner without advance written permission

from the agency. While permission to reprint this publication is not necessary, when quoting, paraphrasing, or otherwise referring to this

report, the citation should be: National Threat Assessment Center. (2019). Protecting America’s Schools: A U.S. Secret Service Analysis of

Targeted School Violence. U.S. Secret Service, Department of Homeland Security.

This report was authored by the staff of the

U.S. Secret Service National Threat Assessment Center (NTAC)

Lina Alathari, Ph.D.

Chief

Front Cover:

FEBRUARY 15-19, 2018

Flags flown at half-staff in honor of the victims of the shooting at

Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida

Diana Drysdale, M.A.

Supervisory Social Science Research Specialist

Ashley Blair, M.A.

Social Science Research Specialist

Arna Carlock, Ph.D.

Social Science Research Specialist

Aaron Cotkin, Ph.D.

Social Science Research Specialist

Brianna Johnston, M.A.

Social Science Research Specialist

Christina Foley, M.S.W.

Assistant to the Special Agent in Charge

Peter Langman, Ph.D.

Psychologist and Author

Eric B. Elbogen, Ph.D.

Professor of Psychiatry and

Behavioral Sciences, Duke

University School of Medicine

Wade Buckland

Senior Scientist,

Human Resources

Research Organization

Special thanks to the following for their contributions to the project:

Steven Driscoll, M.Ed.

Lead Social Science Research Specialist

David Mauldin, M.S.W.

Social Science Research Specialist

Jeffrey McGarry, M.A.

Social Science Research Specialist

Jessica Nemet, M.A.

Social Science Research Specialist

Natalie Vineyard, M.S.

Social Science Research Specialist

John Bullwinkel, M.A.

Assistant to the Special Agent in Charge

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/2019

The U.S. Secret Service has a longstanding tradition of conducting threat assessments as part of its mandate to ensure

the safety of this Nation’s highest elected ofcials. Our National Threat Assessment Center (NTAC) is dedicated to

expanding the eld of violence prevention by closely examining the targeted violence that affects communities across the

United States. As part of this mission, NTAC has maintained a particular focus on the prevention of targeted school

violence. For 20 years, the Center has studied these tragedies, and the following report, titled Protecting America’s

Schools: A U.S. Secret Service Analysis of Targeted School Violence, supports past Secret Service research ndings that

indicate targeted school violence is preventable.

While communities can advance many school safety measures on their own, our experience tells us that keeping schools

safe requires a team effort and the combined resources of the federal, state, and local governments; school boards; law

enforcement; and the public. With this study, the Secret Service provides an unprecedented base of facts about school

violence, as well as an updated methodology and practical guidelines for prevention. We encourage all of our public safety

partners and education partners to review the information within, and to use it to guide the best practices for maintaining

a safe learning environment for all children.

For 150 years, the men and women of the Secret Service have carried out our no-fail mission to protect the Nation’s

leaders and nancial infrastructure. Our relationships across the federal, state, and local levels have been instrumental

to our success. The agency is committed to carrying on this collaborative approach to better protect our children and our

schools. We are proud to release this report.

The U.S. Secret Service’s National Threat Assessment Center (NTAC) was created in 1998 to provide guidance on threat assessment both within the U.S.

Secret Service and to others with criminal justice and public safety responsibilities. Through the Presidential Threat Protection Act of 2000, Congress

formally authorized NTAC to conduct research on threat assessment and various types of targeted violence; provide training on threat assessment and

targeted violence; facilitate information-sharing among agencies with protective and/or public safety responsibilities; provide case consultation on

individual threat assessment investigations and for agencies building threat assessment units; and develop programs to promote the standardization of

federal, state, and local threat assessment processes and investigations.

James M. Murray

Director

MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/2019

Ensuring the safety of children at school is a responsibility that belongs to everyone, including law enforcement, school

staff, mental health practitioners, government ofcials, and members of the general public. To aid in these efforts, the U.S.

Secret Service National Threat Assessment Center (NTAC) studied 41 incidents of targeted school violence that occurred

at K-12 schools in the United States from 2008 to 2017. This report builds on 20 years of NTAC research and guidance

in the eld of threat assessment by offering an in-depth analysis of the motives, behaviors, and situational factors of the

attackers, as well as the tactics, resolutions, and other operationally-relevant details of the attacks.

The analysis suggests that many of these tragedies could have been prevented, and supports the importance of schools

establishing comprehensive targeted violence prevention programs as recommended by the Secret Service in Enhancing

School Safety Using a Threat Assessment Model: An Operational Guide for Preventing Targeted School Violence.

1

This

approach is intended to identify students of concern, assess their risk for engaging in violence or other harmful activities,

and implement intervention strategies to manage that risk. The threshold for intervention should be low, so that schools

can identify students in distress before their behavior escalates to the level of eliciting concerns about safety.

Because most of these attacks ended very quickly, law enforcement rarely had the opportunity to intervene before serious

harm was caused to students or staff. Additionally, many of the schools that experienced these tragedies had implemented

physical security measures (e.g., cameras, school resource ofcers, lockdown procedures). Prevention is key.

Some of the key ndings from this study, and their implications for informing school violence prevention efforts, include:

• There is no profile of a student attacker, nor is there a profile for the type of school that has been targeted:

Attackers varied in age, gender, race, grade level, academic performance, and social characteristics. Similarly,

there was no identied prole of the type of school impacted by targeted violence, as schools varied in size,

location, and student-teacher ratios. Rather than focusing on a set of traits or characteristics, a threat assessment

process should focus on gathering relevant information about a student’s behaviors, situational factors, and

circumstances to assess the risk of violence or other harmful outcomes.

• Attackers usually had multiple motives, the most common involving a grievance with classmates: In addition to

grievances with classmates, attackers were also motivated by grievances involving school staff, romantic

relationships, or other personal issues. Other motives included a desire to kill, suicide, and seeking fame or

notoriety. Discovering a student’s motive for engaging in concerning behavior is critical to assessing the

student’s risk of engaging in violence and identifying appropriate interventions to change behavior and

manage risk.

• Most attackers used firearms, and firearms were most often acquired from the home: Many of the attackers

were able to access rearms from the home of their parents or another close relative. While many of the rearms

were unsecured, in several cases the attackers were able to gain access to rearms that were secured in a locked

gun safe or case. It should be further noted, however, that some attackers used knives instead of rearms to

perpetrate their attacks. Therefore, a threat assessment should explore if a student has access to any weapons,

with a particular focus on weapons access at home. Schools, parents, and law enforcement must work together

rapidly to restrict access to weapons in those cases when students pose a risk of harm to themselves or others.

• Most attackers had experienced psychological, behavioral, or developmental symptoms: The observable mental

health symptoms displayed by attackers prior to their attacks were divided into three main categories:

psychological (e.g., depressive symptoms or suicidal ideation), behavioral (e.g., deance/misconduct or symptoms

of ADD/ADHD), and neurological/developmental (e.g., developmental delays or cognitive decits). The fact that half

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/2019

of the attackers had received one or more mental health services prior to their attack indicates that mental health

evaluations and treatments should be considered a component of a multidisciplinary threat assessment, but not

a replacement. Mental health professionals should be included in a collaborative threat assessment process that

also involves teachers, administrators, and law enforcement.

• Half of the attackers had interests in violent topics: Violent interests, without an appropriate explanation, are

concerning, which means schools should not hesitate to initiate further information-gathering, assessment, and

management of the student’s behavior. For example, a student who is preoccupied or xated on topics like the

Columbine shooting or Hitler, as was noted in the backgrounds of several of the attackers in this study, may be the

focus of a school threat assessment to determine how such an interest originated and if the interest negatively

impacts the student’s thinking and behavior.

• All attackers experienced social stressors involving their relationships with peers and/or romantic partners:

Attackers experienced stressors in various areas of their lives, with nearly all experiencing at least one in the six

months prior to their attack, and half within two days of the attack. In addition to social stressors, other stressors

experienced by many of the attackers were related to families and conicts in the home, academic or disciplinary

actions, or other personal issues. All school personnel should be trained to recognize signs of a student in crisis.

Additional training should focus on crisis intervention, teaching students skills to manage emotions and resolve

conicts, and suicide prevention.

• Nearly every attacker experienced negative home life factors: The negative home life factors experienced by

the attackers included parental separation or divorce, drug use or criminal charges among family members, and

domestic abuse. While none of the factors included here should be viewed as predictors that a student will be

violent, past research has identied an association between many of these types of factors and a range of negative

outcomes for children.

• Most attackers were victims of bullying, which was often observed by others: Most of the attackers were

bullied by their classmates, and for over half of the attackers the bullying appeared to be of a persistent pattern

which lasted for weeks, months, or years. It is critical that schools implement comprehensive programs designed to

promote safe and positive school climates, where students feel empowered to report bullying when they witness it

or are victims of it, and where school ofcials and other authorities act to intervene.

• Most attackers had a history of school disciplinary actions, and many had prior contact with law enforcement:

Most attackers had a history of receiving school disciplinary actions resulting from a broad range of inappropriate

behavior. The most serious of those actions included the attacker being suspended, expelled, or having law

enforcement interactions as a result of their behavior at school. An important point for school staff to consider is

that punitive measures are not preventative. If a student elicits concern or poses a risk of harm to self or others,

removing the student from the school may not always be the safest option. To help in making the determination

regarding appropriate discipline, schools should employ disciplinary practices that ensure fairness, transparency

with the student and family, and appropriate follow-up.

• All attackers exhibited concerning behaviors. Most elicited concern from others, and most communicated their

intent to attack: The behaviors that elicited concern ranged from a constellation of lower-level concerns to

objectively concerning or prohibited behaviors. Most of the attackers communicated a prior threat to their target or

communicated their intentions to carry out an attack. In many cases, someone observed a threatening

communication or behavior but did not act, either out of fear, not believing the attacker, misjudging the immediacy or

location, or believing they had dissuaded the attacker. Students, school personnel, and family members should be

encouraged to report troubling or concerning behaviors to ensure that those in positions of authority can intervene.

A multidisciplinary threat assessment team, in conjunction with the appropriate policies, tools, and training, is the best

practice for preventing future tragedies. A thorough review of the ndings contained in this report should make clear that

tangible steps can be taken to reduce the likelihood that any student would cause harm, or be harmed, at school.

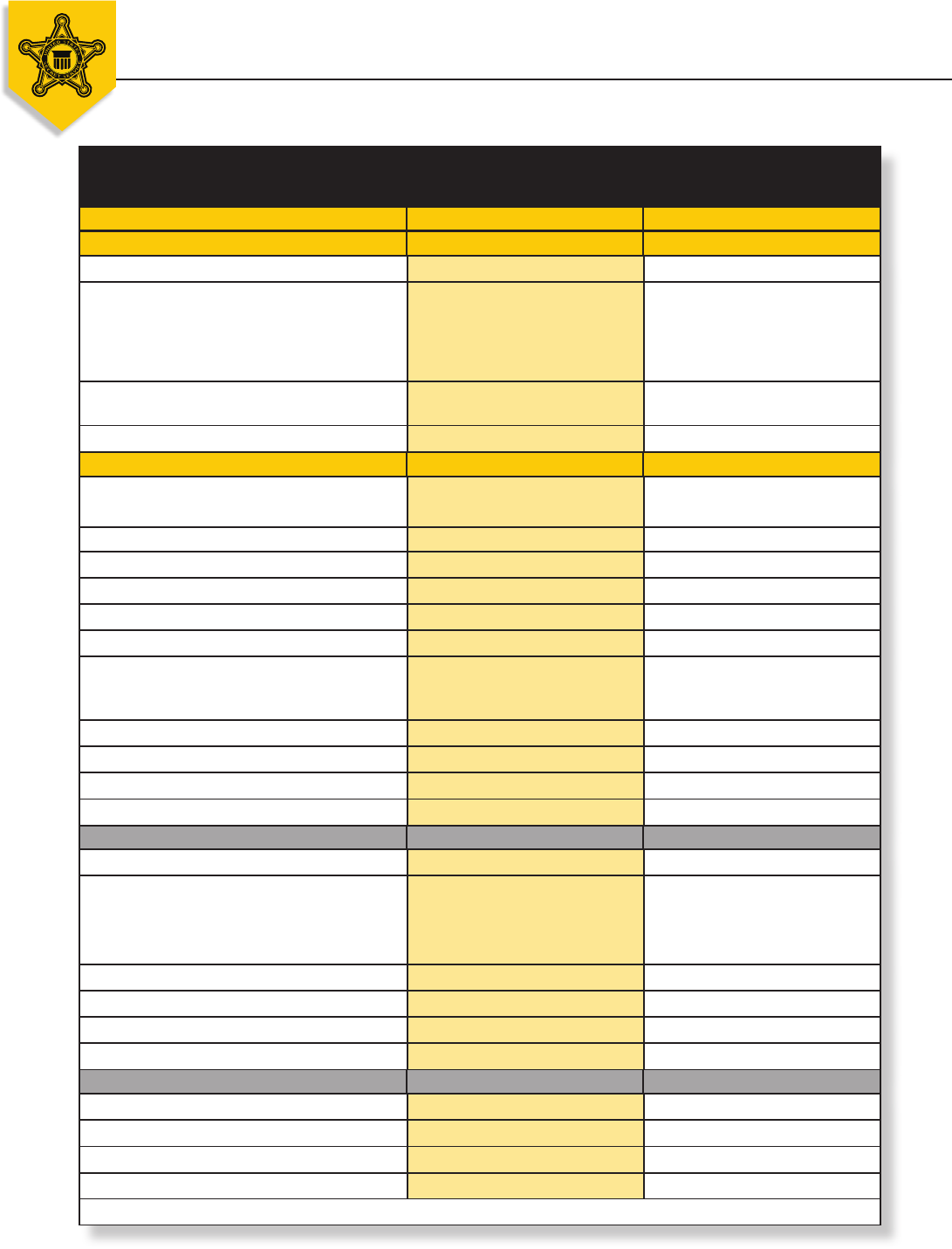

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................1

PART I: OVERVIEW OF THE ATTACKS ................................................................................................ 7

School & Community Information .......................................................................................................7

School Security & Prevention Measures .............................................................................................8

Weapons Used ................................................................................................................................. 9

Timing & Location ............................................................................................................................9

Response Times ............................................................................................................................11

Resolution & Harm .........................................................................................................................12

Judicial Outcomes ..........................................................................................................................13

PART II: THE ATTACKERS ...............................................................................................................14

Motives .........................................................................................................................................15

Targeting........................................................................................................................................18

Planning ........................................................................................................................................20

Firearm Acquisition .........................................................................................................................22

Law Enforcement Contact ...............................................................................................................23

Psychological, Behavioral, & Developmental Health ...........................................................................24

Substance Use & Abuse .................................................................................................................27

Weapons Use & Violence ................................................................................................................27

Home Life Factors ..........................................................................................................................29

Stressors ......................................................................................................................................31

Bullying .........................................................................................................................................33

School Interactions & Relationships ................................................................................................37

Academic Performance & Extracurricular Activities ............................................................................37

Disciplinary History.........................................................................................................................38

Threat Assessment ........................................................................................................................42

Concerning Behaviors .....................................................................................................................43

PART III: IMPLICATIONS.................................................................................................................49

APPENDIX A: STATISTICAL ANALYSES ...............................................................................................55

APPENDIX B: COMPARISON TO THE SAFE SCHOOL INITIATIVE ............................................................57

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS

A U.S. SECRET SERVICE ANALYSIS

OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

1

For the past 20 years, the U.S. Secret Service National Threat Assessment Center (NTAC) has been conducting a

unique blend of operationally relevant and behavior-based research on the prevention of targeted violence in various

contexts, including attacks targeting public ofcials and public gures, government facilities, workplaces, public

spaces, K-12 schools, and institutions of higher education. Targeted violence is a term coined by the Secret Service to

refer to any incident of violence where an attacker selects a particular target prior to an attack. The Presidential Threat

Protection Act of 2000 congressionally authorized NTAC to conduct research, training, consultation, and

information-sharing on the prevention of targeted violence, and to provide guidance to law enforcement, government

agencies, schools, and other public safety and security professionals.

Threat assessment is the best practice for preventing incidents of targeted violence. It is an investigative approach

pioneered by the Secret Service, originally developed as a means to prevent assassinations. A threat assessment,

when conducted by the Secret Service, involves identifying

individuals who have a concerning or threatening interest

in the president of the United States or another protected

person, conducting an investigation to assess whether

that individual poses a risk of violence or other unwanted

outcome, and then taking steps to manage that risk.

These cases receive the highest priority of all Secret

Service investigations, and the agency considers these

investigations to be as important as the physical security

measures it employs.

The Secret Service’s threat assessment model has since

been adapted to prevent other acts of targeted violence

impacting communities across the United States. These

attacks have a profound and devastating impact on those

directly affected and the Nation as a whole, none more so

than attacks at K-12 schools.

2

Following the tragedy at

Columbine High School in 1999, the Secret Service

partnered with the U.S. Department of Education on a

study that examined 37 incidents of targeted school

violence that occurred from 1974 to 2000. The Safe

School Initiative focused on gathering and analyzing

information about the thinking and behavior displayed by

the students who committed these violent acts.

3

The

publication of the nal report and accompanying guide

provided schools and law enforcement with a framework

for how to identify, assess, and manage students who

display such threatening or concerning behavior.

Key Findings from the Safe School Initiative

(2002)

• Incidents of targeted violence at school rarely were

sudden or impulsive acts.

• Prior to most incidents, other people knew about the

attacker’s idea and/or plan to attack.

• Most attackers did not threaten their targets directly

prior to advancing the attack.

• There is no accurate or useful “profile” of students

who engaged in targeted school violence.

• Most attackers engaged in some behavior prior to the

incident that caused others concern or indicated a

need for help.

• Most attackers had difficulty coping with significant

losses or personal failures. Moreover, many had

considered or attempted suicide.

• Many attackers felt bullied, persecuted, or injured by

others prior to the attack.

• Most attackers had access to and had used weapons

prior to the attack.

• Most attackers demonstrated some interest in

violence, through movies, video games, books, or

other media.

• Most attackers had no history of prior violent or

criminal behavior.

• In many cases, other students were involved in some

capacity.

• Despite prompt law enforcement responses, most

attacks were stopped by means other than law

enforcement intervention.

INTRODUCTION

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/ 2019

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

2

Since the release of the study in 2002, the ndings of the Safe School Initiative have informed the targeted violence

prevention efforts of schools and law enforcement across the country. To date, NTAC has delivered over 500 trainings

on K-12 school threat assessment to over 100,000 school personnel, law enforcement, mental health professionals,

and others with school safety responsibilities. NTAC has further consulted with individual schools and school districts,

as well as county and state governments, as they developed threat assessment protocols geared toward proactively

preventing these tragedies.

There is more work to be done.

In 2018, two incidents of targeted school violence alone resulted in the tragic loss of 27 students and staff, and

serious injuries to 30 more. The February 14, 2018 attack at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, FL

and the May 18, 2018 attack at Santa Fe High School in Santa Fe, TX prompted school personnel, law enforcement,

government agencies, and others to identify strategies for preventing future attacks. To support these efforts, NTAC

initiated programs to provide updated research and guidance on threat assessment and the prevention of targeted

school violence.

The rst phase involved the creation and distribution of an operational

guide titled Enhancing School Safety Using a Threat Assessment

Model: An Operational Guide for Preventing Targeted School

Violence. Released in July 2018, the guide outlines actionable steps

schools can take to create multidisciplinary threat assessment

teams, establish central reporting mechanisms, identify student

behaviors of concern, dene the threshold for law enforcement

intervention, promote safe school climates, and identify

intervention and management strategies for decreasing the risk

of a targeted attack. The guide is available on the Secret

Service public website and was distributed to 40,000 public

school districts and private schools across

the country.

The second phase was to conduct a new research study

expanding on the Secret Service’s previous work in

studying targeted school violence. The report that follows is

the culmination of these efforts and represents the most

in-depth analysis of targeted school violence conducted

in decades. Protecting America’s Schools: A U.S. Secret

Service Analysis of Targeted School Violence examines

41 attacks against K-12 schools in the United States

from 2008 to 2017. The report examines the backgrounds and

behaviors of the attackers, in order to inform the best practices of

multidisciplinary school threat assessment programs nationwide.

ENHANCING SCHOOL SAFETY

USING A THREAT ASSESSMENT MODEL

An Operational Guide for

Preventing Targeted School Violence

National Threat Assessment Center

July 2018

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/2019

Methodology

Incident Identication

NTAC researchers initiated a systematic review of relevant databases, publications, and public reports. The review

sought to identify incidents of targeted school violence that occurred in the United States from 2008 to 2017. For

this study, an incident of targeted school violence was dened as any incident in which (i) a current or recently former

4

K-12 school student (ii) purposefully used a weapon (iii) to cause physical injury to, or the death of, at least one other

student and/or school employee (iv) in or on the immediate property of the school (v) while targeting in advance one

or more specic and/or random student(s) and/or employee(s).

Certain exclusions were used in order to focus this project on incidents of targeted school violence. This study does

not include attacks where a perpetrator could not be identied, or incidents related to gang violence, drug violence, or

other incidents with a strong suggestion of a separate criminal nexus. Similarly, it does not include violence from the

surrounding community that spilled onto school property by happenstance. It also excludes spontaneous acts, such

as those that were the immediate result of an unplanned ght or other sudden confrontation.

Because this project was initiated in early 2018, incident identication and collection were limited to cases that

occurred through 2017, thereby allowing researchers to gather the most comprehensive case information for each

incident. For this reason, the tragedies that have occurred in 2018 and 2019 were not included in the analysis.

Based on the stated criteria, researchers identied 41 incidents of targeted school violence, perpetrated by 41 current

or recently former students, from January 2008 through December 2017.

Case Information

Researchers largely obtained information for the 41 identied incidents from primary source materials related to the

incident. Secret Service eld ofces across the United States worked with their local law enforcement partners to

acquire investigative case les for 36 of the 41 incidents. These les included police investigative records, publicly

available court records, and other publicly available information. These source materials may have also contained

school records and mental health records. Obtained records included interviews with the attackers, interviews with

witnesses and people who knew the attackers, school transcripts and disciplinary histories, social media screen

captures, data from the searches of phones and computers used by the attackers, the results of searches of the

attackers’ residences, personal journals and other writings, and court records containing the results of mental health

evaluations both before and after the attacks. All case examples used in the drafting of this report were vetted

through the agencies who provided the investigative les. Case analysis was further supplemented through a

rigorous, structured review of open source information, including news articles and reports from government and

private agencies. NTAC staff considered all available qualitative information to develop data relevant to threat

assessment and prevention factors for each case. Some data were analyzed and are reported here for all 41 cases,

including information on how the attacks were executed, school information, and demographic information about the

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

3

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/ 2019PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/ 2019

attackers. Information on the behavioral histories of the attackers, however, was only analyzed for 35 of the 41 cases

due to the limited information available on the backgrounds of 6 of the attackers.

Multiple layers of review were applied to every stage of the project to ensure accuracy and reliability of

reported ndings.

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/2019

4

5

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/ 2019

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/2019

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

6

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

PART I: OVERVIEW OF THE ATTACKS

School & Community Information

SCHOOL TYPES: All but two of the attacks occurred in public schools (n = 39, 95%). Nearly three-quarters of the

attacks were carried out at high schools (n = 30, 73%), which are dened in this report as any school that reaches

12th grade. Nine attacks took place at middle schools (22%), and one attack occurred at an elementary school (2%).

One additional attack occurred at a K-11

school (2%).

COMMUNITIES: Approximately one-third (n = 14,

34%) of the attacks occurred in schools located in

suburban communities, while 11 attacks occurred

in cities (27%). Ten incidents were carried out in

rural schools (24%), and the fewest attacks took

place in small towns (n = 6, 15%).

5

SCHOOL SIZE: Over half (n = 24, 59%) of the attacks took place at

schools with fewer than 1,000 students, and 17 (41%) occurred at

schools with 1,000 students or more. Over one-third of the attacks took

place at schools with between 500 and 999 students (n = 15, 37%).

CLASS SIZE: Teacher-to-pupil ratios also varied among the impacted

schools, with eight of the schools (20%) at the national average of 1:15

to 1:16. One-third (n = 13, 32%) had lower ratios than the average, and

20 schools (49%) had higher ratios. The highest ratio was 1 teacher for

every 26 students.

7

* National average

Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

Teacher-to-Pupil Ratios

1:9 to 1:14

1:15 to 1:16*

6

1:20 to 1:26

1:17 to 1:19

32%13

20%

27%

8

11

22%9

Elementary School 2%

Other School 2%

SCHOOL TYPE

Middle

School

22%

High

School

73%

7

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/ 2019

Student Enrollment

<500

1000 - 1499

500 - 999

1500+

22%

20%

9

8

37%

22%

15

9

Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

8

School Security & Prevention Measures

Most of the schools (n = 33, 80%) in this study implemented some type of physical security measure, and two-thirds

(n = 27, 66%) had full- or part-time school resource officers (SROs) on campus.

PHYSICAL SECURITY MEASURES: The most frequently used physical security measure was school lockdown

procedures, present in at least 28 (68%) of the schools where an attack took place. Fourteen (34%) schools had

security cameras, which were located either inside or outside of the

schools. Seven (17%) had alert systems, which were used to notify

members of the school community of emergencies via automated

text messages or phone calls. Three (7%) schools had

magnetometers, but they were not regularly used. Six (15%) schools

employed private security guards, who were usually unarmed.

SCHOOL RESOURCE OFFICERS: At the time of the attacks, nearly

half of the schools (n = 19, 46%) had one or more full-time SROs.

An additional eight schools (20%) had an SRO who operated at the

school part-time because they were assigned to multiple schools

within the district.

REPORTING TOOLS: Only seven (17%) schools had any type of

system in place to notify school staff or administrators of

threatening or concerning student behaviors before an attack.

These systems usually involved a phone number, email address, or

a paper referral through which the school could be contacted. At the

time of the incidents, few states had

implemented comprehensive statewide reporting

programs, like Safe2Tell™ Colorado.

ASSESSMENT AND INTERVENTION PROTOCOLS:

Nine (22%) schools had some type of program

involving employees who were assigned to

assess unwanted or potentially harmful student

behavior. Some of these schools had developed

basic protocols for assessing and responding

to reports of a student threat. In others, school

staff created more formal threat assessment

teams, but the participation, training, and

protocols of these teams varied. The Secret

Service recommends that schools implement

multidisciplinary school threat

Physical Security and

Threat Assessment

When the Safe School Initiative was published in 2002,

it stated that “the Secret Service considers threat

assessment to be as important to preventing targeted

violence as the physical measures it employs." The

Secret Service protects our Nation’s highest elected

ofcials using physical security measures in

conjunction with, and complemented by, a threat

assessment approach designed to proactively

intervene with those individuals who intend to cause

harm. This complementary approach to protection

recognizes that either of the approaches, alone, would

not constitute the most effective means of preventing

an attack.

Safe2Tell

TM

Colorado

Safe2Tell is a statewide, anonymous reporting tool, which accepts tips 24/7

regarding any concern of safety to self or others. Every tip is evaluated by

Safe2Tell analysts at the Colorado Information Analysis Center (CIAC), then

disseminated to schools and local law enforcement as appropriate. Built-in

accountability ensures that every tip is responded to before a case can

be closed.

During the 2018-2019 school year, 19,861 tips were received by Safe2Tell.

The most common tips received related to student suicide, drug use,

and bullying.

For states that would like to implement this type of reporting program,

Safe2Tell provides information and resources at:

www.safe2tell.org

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/2019

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/2019

9

assessment teams in accordance with Enhancing School Safety Using a Threat Assessment Model: An Operational

Guide for Preventing Targeted School Violence. This framework is intended to help schools develop the capacity to

identify, assess, and manage students who display concerning or threatening behaviors. This process should

complement the physical security measures that a school determines are appropriate for its community.

Weapons Used

Most of the attackers (n = 25, 61%) used rearms, which included handguns, ries, and

shotguns. In total, attackers used 18 handguns and 9 long guns during the attacks,

with two attackers using multiple rearms. The remainder (n = 16, 39%) used bladed

weapons, which most frequently included pocket or folding knives, followed by butcher

or kitchen knives, and hunting knives. In one instance, the attacker used a World War II

bayonet. Three of the attackers used a combination of weapons to cause harm or dam-

age, including one who used a knife and a claw hammer, another who used a knife and

a bo staff, and another who used a rearm and a Molotov cocktail.

Several of the attackers brought other weapons to the attack that they did not

ultimately use. Some brought knives in addition to the rearm or knife that was used,

while others brought items ranging from a wrench wrapped in a bandana to homemade explosives. For example, one

attacker who used a knife in his attack also brought ve other knives, a blowtorch, three containers of ammable

liquid, and recrackers.

Timing & Location

TIMING OF THE ATTACKS: The 41 attacks occurred with

varying frequency from year to year and did not appear to

be steadily increasing or decreasing. While these

incidents comprise only some of the acts of violence

that occur in K-12 schools each year, data from the CDC

regarding all school-associated violent deaths similarly do

not show a steady increase or decrease.

8

Incidents in the current study took place in every month except July and

occurred on every day of the week except Sunday. The one incident that

occurred on a Saturday took place outside of a school prom.

Three-quarters of the attacks were carried out before the school day

began (n = 10, 24%) or during morning classroom hours (n = 21, 51%).

Firearm

61%

Knife

39%

WEAPON USED

*

*

Three attackers also used another

weapon including a hammer, a bo staff,

and a Molotov cocktail.

Timing of the Attacks

Before school .............................. 10 (24%)

Morning classroom hours .......... 20 (51%)

During lunch .....................................3 (7%)

Afternoon classroom hours ..........6 (15%)

Outside school hours ...................... 1 (2%)

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/2019

10

BREAKS IN ATTENDANCE: Incidents occurred most

frequently at the start of the school year (Sep) or

after students returned from winter break (Jan).

Seventeen attacks (41%) took place within the

first week back to school following a break in

attendance, such as a suspension, school

holiday, or an absence due to illness or truancy.

Nearly one quarter of the attacks (n = 10, 24%)

took place on the first day that the attacker

returned to school after an absence. In two of

these incidents, the attacker was actively

suspended from the school at the time of the

attack. These ndings suggest that schools should

make concerted efforts to facilitate positive student engagement following discipline, including suspensions and

expulsions, and especially within the rst week that the student returns to school.

A 14-year-old student fatally stabbed a classmate at the middle school they both attended. At the time of the incident, the

attacker was suspended for truancy. Despite the suspension, witnesses reported seeing him walking the school’s hallways in

search of the target shortly before the stabbing took place.

Four attacks (10%) occurred on the rst day back from a regularly scheduled school holiday. Of those, three took place

on the rst day following an extended break, including the summer, fall, and winter holidays.

A 15-year-old student shot and wounded a random classmate in the high school

cafeteria on the rst day of the school year. The attacker had planned the attack over

the last week of his summer break. On the morning of the incident, he shared a message

on social media stating, “First day of school, last day of my life.” The shooting took place

four hours later.

DURATION OF THE ATTACKS: Most of the attacks (n = 34, 83%) lasted ve minutes

or less. Two-thirds of the incidents (n = 28, 68%) lasted for two minutes or less,

and nearly half of the attacks (n = 18, 44%) ended within one minute. Only six of

the attacks (15%) lasted longer than ve minutes, and none of the attacks lasted

longer than 15 minutes.

9

LOCATION OF THE ATTACKS: The attacks usually started and ended

in the same location (n = 36, 88%). The most common locations of

attacks were in classrooms and immediately outside of the school.

Other locations included cafeterias, hallways, and administrative

ofces. Attacks in restrooms, locker rooms, a gymnasium, and a

vestibule were less common.

Locations of the Attacks

Classroom Outside Office

Cafeteria Hallway Restroom

Locker room Gym Vestibule

DURATION OF THE ATTACKS

1 min

or less

44%

1-2 min

24%

2-5 min

15%

5-15 min

15%

Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Response Times

SCHOOL OFFICERS: In 27 cases (66%), a security ofcer or SRO was assigned to the school on either a full- or part-

time basis. During 20 of the attacks (49%), the ofcer was on duty at the school. In over one-quarter of the cases

(n = 12, 29%), the ofcer or SRO was able to make it to the scene of the attack within one minute. In three of the

attacks (7%), it took between one and ve minutes for the ofcer to respond, and for two attacks (5%), it took between

ve and ten minutes. Of note, in two cases the ofcers themselves were the targets of the attacks, and in the

remaining, it was not possible to determine the response time based on available information.

OUTSIDE LAW ENFORCEMENT: In just over one-third of the attacks (n = 16, 39%), outside law enforcement were

notified within one minute of the start of the attack, and in just under one-third (n = 12, 29%), outside police were

notied between one and ve minutes after the start of the attack. In nine cases, it took longer than ve minutes for

someone to notify outside law enforcement, and in four cases the timing could not be determined from

information available.

In nearly one-third of the cases (n = 13, 32%), it took external rst responders between one and ve minutes to arrive

on scene after the attack was initiated, and in about a quarter of the cases (n = 11, 27%) rst responders arrived

between ve and ten minutes after the attack began. In only one case, outside law enforcement responded in one

minute or less, because ofcers were already at the school conducting K-9 drug sweeps at the time of the attack.

Outside LE

Response

Time

Outside LE

Notification

School Officer

Response

Time*

1 (2%)

11 (27%)

3 (7%)

9 (22%)

16 (39%)

4 (10%)

––

4 (10%)

12 (29%)

2 (5%)

––

3 (7%)

1 min or less

>5 to 10 min

>15 min

Not found

13 (32%)

4 (10%)

––

12 (29%)

5 (12%)

––

3 (7%)

––

21 (51%)**

>1 to 5 min

>10 to 15 min

Not applicable

*Percentages may not equal 100 due to rounding.

**Includes those schools without ofcers assigned, assigned ofcers off-duty

at the time, and cases in which the SROs were targeted.

11

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/ 2019

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

12

Resolution & Harm

ATTACK RESOLUTION: Half of the attackers (n = 21, 51%) ended the attack without any external intervention. Seven

attackers (17%) committed suicide, six (15%) left the scene, three (7%) surrendered to school ofcials, three (7%)

dropped their weapons and waited to be arrested, one (2%) stopped and called family, and one attacker (2%) left the

scene before calling family.

Non-law enforcement adult school staff brought nine attacks (22%) to an end. This included teachers, guidance

counselors, an assistant principal, a sports coach, a campus supervisor, and a janitor. Six of the attacks (15%) ended

with law enforcement intervention, either by SROs (n = 5, 12%) or by local police who were already on campus

(n = 1, 2%). Two of the attackers were killed by the law enforcement response. No attacks were ended by outside law

enforcement agencies responding to the scene from off-campus. Other attacks ended due to student bystander

intervention (n = 4, 10%) or a weapon malfunction (n = 1, 2%).

HARM: Ninety-eight victims were harmed in the 41 attacks, including 79 injured

and 19 killed. The victims included students, school staff, and law enforcement.

10

One stabbing incident accounted for 20 of the 98 victims, all of whom were injured

but survived. In just over half of the attacks (n = 22, 54%), only one individual was

harmed. In the remaining attacks, two persons were harmed (n = 9, 22%), or three

or more were harmed (n = 10, 24%).

TWENTY VICTIMS: A 16-year-old student randomly slashed and stabbed people at his high

school using two kitchen knives he had brought from home. Nineteen students and one

staff member were injured, but all survived. The attack ended after about ve minutes

when the assistant principal tackled the assailant.

Mass Attacks

The definition of a “mass attack,” as used by the U.S. Secret Service in its Mass Attacks in Public Spaces report series,

includes harm (i.e., injury or death) to three or more persons, not including the attacker. About one-quarter of attacks

(n = 10, 24%) in this study meet that definition of a mass attack.

PERSONS INJURED OR KILLED

Students

85%

Law Enforcement

2%

Staff

13%

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/ 2019

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Judicial Outcome

CRIMINAL CHARGES: Thirty-two attackers (78%) were criminally charged,

twenty-two of whom (54%) were charged as adults. Nearly all of those

charged as adults accepted plea agreements (17 pled guilty; 2 pled no

contest). Only two cases went to trial, where both attackers were found

guilty and sentenced as adults. A third attacker is still awaiting trial in

adult court.

Twelve attackers were processed through the juvenile justice system.

Of those charged as juveniles, the majority pled to their charges (9 pled

guilty; 1 pled no contest).

CURRENT DISPOSITIONS: Twenty-two of the attackers (54%) are

currently incarcerated and one attacker is a patient at a mental health

facility. Eight attackers (20%) have been released from juvenile or adult

correctional institutions.

11

Judicial Actions

Adult

Juvenile

No Charges Filed

Subject pled guilty

Subject pled guilty

Subject committed

suicide

Subject pled

no contest

Subject pled

no contest

Subject found guilty

Unknown

Subject fatally shot

Percentages exceed 100 as two attackers had both adult and

juvenile charges.

Charges led,

case pending

54%

29%

22%

22

12

9

41%

22%

17%

5%

2%

17

9

7

2

1

5%

5%

5%

2%

2

2

2

1

13

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/ 2019

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/2019

14

PART II: THE ATTACKERS

GENDER, RACE, & AGE: While the attackers were predominantly male (n = 34, 83%), seven of the attackers were

female (17%). Based on police report designations, approximately two-thirds of the attackers (n = 26, 63%) were

White, six were Black (15%), and two were Hispanic (5%). Their ages ranged from 12 to 18, with an average age of 15.

YOUNGEST: A 12-year-old student opened re at his middle school. He killed one teacher and injured

two classmates before fatally shooting himself. The attacker had a history of being bullied and felt

mistreated by students and teachers.

OLDEST: An 18-year-old former student, who had graduated the year prior, opened re outside of his

old high school toward a group of students exiting the prom. Two of the students were shot and

injured. Local police, already on scene conducting drug sweeps, instructed the attacker to drop his

weapon. When the attacker failed to comply with police instructions, he was fatally shot by one of the

ofcers. The attacker believed that his ex-girlfriend and her new boyfriend were attending the prom

together, but neither was actually in attendance

.

GRADE LEVEL: The grade levels of the attackers

ranged from 7th grade to 12th grade.

FORMER STUDENTS: Four of the attackers (10%)

targeted schools in which they were no longer

enrolled as students. They included a student who

attacked his former high school after transferring

to an alternative school; a student whose mother

withdrew him from school because he was about to be expelled; a student who had graduated the previous year, but

was working at the school as a teacher’s assistant and occasionally performed with the school marching band; and a

middle school student who attacked his former elementary school.

Male

83%

Female

17%

GENDER

Race/Ethnicity

White

American Indian or Alaska Native

Black/African American

Two or more races

Hispanic

Undetermined

63%

2%

26

1

15%

10%

6

4

Categories consistent with the U.S. Department of Education guidance on the

collection and reporting of racial and ethnic data. (72 Fed. Reg. 59267 Pub. 2007.)

5%

5%

2

2

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/2019

15

Motives

When determining motives, all available information about each attacker's thinking and behavior in the time leading

up to the attack was considered, including explicit explanations of motive that the attackers provided through verbal

statements made before the attack, in suicide notes or manifestos, and during post-incident interviews with

law enforcement.

Consistent with other forms of targeted violence, the motives behind these 41 school attacks varied widely and were

based on the personal perceptions and experiences of the attackers. Most attackers had multiple motivations for

carrying out their attacks. This analysis indicates that a student’s motive to carry out a violent act at school is

usually multifaceted and is the byproduct of the student’s individual circumstances, as well as their personal

perception of those circumstances.

All but two of the 41 attackers had an identiable primary motive, dened as the motive that appeared to most

strongly contribute to the attacker’s decision to act violently. Most of the attackers (n = 35, 85%), however, had at

least one additional secondary motive that contributed to the decision for carrying out the attack.

SINGLE MOTIVE: A recently suspended 14-year-old student fatally stabbed a classmate in the chest as he exited his middle

school. The students had been friends, but their relationship had deteriorated due to frequent conicts. The victim of the

stabbing had previously threatened, harassed, and bullied the attacker. The attacker grew to fear for his life and stopped

attending school in order to avoid the victim, which led to the attacker’s suspension for missing class. The attacker later

reported that he had been motivated by fear, stating that if he had not returned to school to stab his classmate, he believed

that he would have been killed himself.

Components to Motive Primary Secondary Total

Grievances

Psychotic symptoms

Peers

Related to bullying

Staff

Romantic

Other personal

Unknown

Suicidal

Desire to kill

Total

Fame/Notoriety

25 (61%) 9 (22%) 34 (83%)

2 (5%) 3 (7%) 5 (12%)

15 (37%)

--

4 (10%)

4 (10%)

2 (5%)

11 (27%)

--

6 (15%)

5 (12%)

4 (10%)

26 (63%)

19 (46%)

10 (24%)

9 (22%)

6 (15%)

2 (5%) n/a 2 (5%)

3 (7%) 14 (34%) 17 (41%)

7(17%) 8 (20%) 15 (37%)

41 (100%)

2 (5%) 2 (5%) 4 (10%)

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/2019

16

MULTIPLE MOTIVES: An 18-year-old student shot and killed a classmate he encountered immediately upon entering his school.

He then sought out the debate team coach, who escaped, before the attacker killed himself. The attacker appeared to have been

primarily motivated by a grievance with the debate team coach, who had removed him from a captain position on the debate

team. Additional motivations appeared to include grievances with other staff members and classmates, a sadistic desire to hurt

other people, and suicidal ideations.

GRIEVANCES: For most of the attackers (n = 34, 83%), retaliating for a grievance played a role in their motive. For

nearly two-thirds of the attackers (n = 25, 61%), it appeared to be their primary motive.

• Peers: Most frequently, grievances involved classmates (n = 26, 63%), and these peer grievances were usually

related to bullying in some way (n = 19, 46%). Other examples of peer grievances that did not involve bullying

included ongoing conicts and contentious relationships between students, and anger over a specic event or

situation among classmates.

A 14-year-old student fatally shot a classmate at his middle school. The victim had been the subject of harassment by the

attacker and other students, who would call the victim derogatory homophobic names. The attacker later reported that the

victim had made comments that made him uncomfortable, citing them as “the nal straw” in his decision to attack.

• Staff: In a quarter of the attacks, the attacker had a grievance that involved school staff (n = 10, 24%). For

four attackers (10%), this grievance with teachers or administrators was the primary motivation. In each of those

four incidents, the school staff members were specically targeted in the attack.

A 16-year-old student fatally stabbed his high school principal. According to his confession after the incident, the attacker

began planning his attack on the principal three months earlier, after he learned that he would be returning to the same high

school for 11th grade. He stated that the school principal made him the angriest, and he disliked the school and did not

want to attend anymore. He was also angry at having to follow school rules, for example, when the principal repeatedly

made him tuck in his shirt.

• Romantic: Nine cases (22%) involved a grievance related to a romantic relationship as a primary or secondary

motive. Two of these cases involved female attackers, while seven involved male attackers.

A 15-year-old student fatally shot a former romantic partner outside of their high school before committing suicide. The

students had dated for over two years, but the victim had recently informed the attacker that the relationship was ending.

According to media reports, the attacker had a history of suicidal ideations and depressive symptoms. In redacted

versions of the notes released publicly, the attacker expressed anger at the victim for wasting the attacker’s money, time,

affection, and “so much more.” The attacker also wrote, "We planned our future together," adding, "This week has been the

worst in my life," and, "All of this has destabilized me."

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/2019

17

• Other Personal Issues: Six students (15%) were motivated by other personal grievances, and for two (5%), it was

their primary motive. These personal issues involved things like anger over a failed drug test at school and

retaliating for abuse or neglect occurring at home.

A 14-year-old student opened re toward random classmates in his high school cafeteria. Two students were shot

and injured, and two other students received minor injuries, possibly when struck by shrapnel. The attacker later

stated his motive was attributed to his troubled home life, including a distant relationship with his mother, conicts

with his father, and an addiction to Adderall.

DESIRE TO KILL: The second most prevalent motive among student attackers (n = 15, 37%) was a desire to kill,

evidenced by a sadistic interest in violence or violent topics, a desire for power over their victims, or the expectation

of joy or pleasure in causing physical harm to others. For seven attackers (17%), this appeared to be their primary

motive, and eight additional students (20%) experienced these types of thoughts as a secondary motive. Nearly all

attackers who were primarily motivated by a desire to kill targeted random victims (see Appendix A: Statistical

Analyses). While it is possible that a desire to kill could be associated with psychological symptoms, it often appeared

to develop as a response to the student’s personal circumstances and life experiences.

A 15-year-old student fatally shot a classmate at his high school. The attacker had been in previous conicts with the victim,

but he also displayed a fascination with causing physical harm to others. A few days before the incident, the attacker showed

a handgun and ammunition to classmates, highlighting that “these bullets bounce around inside of your body.” He was also

overheard saying that he was interested in seeing what it felt like to kill someone. During his subsequent trial, a clinical

psychologist said that the attacker had been “born to violent addicts, shoved into abusive foster homes, and largely ignored

by courts and caseworkers.”

SUICIDAL: Seventeen attackers (41%) were motivated by suicide to carry out their attacks. For three attackers (7%),

this appeared to be their primary motive; only one appeared to be motivated by suicide alone. An additional 14

attackers (34%) had suicidality as a secondary motive. These ndings reveal that suicidal ideations were rarely the

sole or primary factor in an attacker’s motivation for violence. Suicidal ideations were more typically found in

combination with, and secondary to, other motives.

A 16-year-old student intended to commit suicide-by-cop when he stabbed

his SRO seven times with a bayonet. The ofcer struggled with the

attacker before fatally shooting him in self-defense. The attacker’s nal

words to the ofcer were, “Thank you sir, thank you.” In a suicide note, the

attacker described human civilization as an “unnatural system,” and

included additional language like, “If you’re reading this, I’m either dead or

on my way to dying. If I fail at suicide, something else will end me. I have

had enough of this tainted and corrupted world we live in,” and, “I hope for

a better existence after my passing.”

Youth Suicide

In 2017, the CDC reported suicide as the second-

leading cause of death among those between the

ages of 10-24 years old.

12

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline provides

free and condential 24/7 support to people in

crisis. If you or someone you know needs help, call

1-800-273-TALK (8255).

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/2019

18

FAME/NOTORIETY: Four students (10%) were motivated by a desire for fame or notoriety as a primary or secondary

motive. Each of these four students expressed a desire to emulate previous mass attackers, including those who

perpetrated the attacks at Columbine High School, Virginia Tech, and Sandy Hook Elementary School.

A 14-year-old student opened re at his SRO in an effort to steal the ofcer’s weapon. He intended to use the ofcer’s rearm

to perpetrate a mass shooting at his high school. The ofcer was burned by the discharging rearm, but detained the student

before further harm occurred. Three months prior, the attacker began keeping an extensive journal about his plans, in which

he described his research into the attacks at Columbine High School and Virginia Tech. He wrote about his desire to be

“worshipped” like previous attackers, adding, “I hope to out-do my idols and leave my mark on the world.” He wrote about how

he hoped that security camera footage of his attack would be on YouTube for his “followers” to study. After the attack, while in

juvenile detention, the student continued to express interest in the media coverage of his attack, asking staff at the detention

center if he could read the comments posted by readers of the online news articles.

PSYCHOTIC SYMPTOMS: Five students (12%) appeared to be motivated by psychotic symptoms, either as a primary

or secondary motive. These cases involved such symptoms as auditory hallucinations instructing the student to hurt

people, compulsive homicidal thoughts and visions, and a delusional belief that the student was in a romantic

relationship with a classmate.

A 15-year-old student randomly stabbed two classmates in a high school restroom. Both victims survived the attack. The

attacker had a history of homicidal and suicidal thoughts, thoughts of violence toward her family and girls at school, and had

previously threatened to stab a friend’s boyfriend. According to court records, six months prior to the attack, she was admitted

to an outpatient hospitalization program for her mental health. One counselor asked the attacker if she had suicidal or

homicidal ideations, and she responded, “Sometimes I get really sick thoughts. Sick ways of killing them, stabbing them,

slitting their throats, sexually abusing people at school.”

Targeting

In all forms of targeted violence, the targeted person or persons are usually selected by the attacker in relation to his

or her motive. For example, if an attacker has a grievance with a specic person or group, they may target that person

or group during the attack. In many of those cases, however, additional bystanders may be injured or killed, either as

unintended collateral victims or as victims of opportunity. In other instances, the attacker may indiscriminately target a

population of people, like the entire student body at a school, depending on the attacker’s goals and motives.

SPECIFIC PERSON TARGETED: In nearly three-quarters of the attacks (n = 30, 73%), the attacker targeted a specic

person or persons. In 22 attacks (54%), a specically targeted person was injured or killed.

A 12-year-old student stabbed her middle school classmate in the neck and stomach, injuring him. Other students had

previously observed the victim teasing the attacker and calling her names. A few days before the incident, the attacker told

another student that she hated the target. Just minutes before the stabbing, the attacker told a group of classmates that she

hated the target and that she wanted to kill him because he was annoying and was a bad person. Nobody else was targeted

or harmed in the attack.

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

SPECIFIC GROUP TARGETED: In six attacks (15%), a specic group of students was targeted (e.g., bullies, “jocks,”

“emos,” “preps,” “sinners”). In only one of those attacks was a member of the targeted group actually harmed.

RANDOM VICTIMS: Seventeen attacks (41%) involved random victims who were attacked indiscriminately or

opportunistically by the attacker (e.g., the attacker red into a crowd or red upon the rst student he saw).

A 16-year-old student randomly attacked a female classmate with a serrated knife and a claw hammer when the victim

walked into the high school restroom. The victim was stabbed and hit several times but survived the attack. The attacker’s goal

was to kill as many people as she could before eeing the school. She then planned to purchase a gun and commit suicide.

COLLATERAL VICTIMS: Five attacks (12%) involved random victims who were injured as collateral bystanders (e.g., the

attacker aimed at a specic target, but an unintended student was shot).

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

19

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/ 2019

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

20

Planning

Over half of the attackers (n = 21, 51%) engaged in observable planning behaviors prior to carrying out their attack

that went beyond making statements of intent. Twelve attackers (29%) exhibited three or more different types of

planning activities that were observable to others. Of note, the attackers in this study who perpetrated mass attacks

averaged more than twice as many planning behaviors as attackers with fewer victims (see Appendix A: Statistical

Analyses). For 10 of the attackers (24%), the rst act of planning occurred within one month of the incident. Seven

attackers (17%) began planning between one and six months before the attack, and rarely did planning begin more

than six months prior (n = 3, 7%).

13

While some attackers discussed their plans with others, no attackers appeared to

receive direct assistance in planning their specic school attack.

WEAPONS RESEARCH AND SELECTION: One-third of the attackers

(n = 13, 32%) researched weapons prior to the attack. This

included conducting online searches, reading books and

pamphlets, and asking others about weapons experience and

other related topics. The research focused on how to make

explosives, weapon functionality and utility, how to inict maximum

damage, and types of protective equipment.

DECEPTIVE PRACTICES: Nine attackers (22%) engaged in deceptive

practices in order to hide their activities and avoid detection. This

included lying about weapons and other materials (e.g., telling

parents that purchased materials were for chemistry class),

concealing weapons for transport, claiming needing a weapon for

protection, and waiting until after dark to manufacture weapons. For example, on the night prior to one attack, the

student waited until his mother went to sleep before building homemade explosives. He then pretended to be asleep

so that his mother could wake him up to start the day, thus maintaining their normal routine and not arousing

any suspicion.

WEAPONS-RELATED: Seven attackers (17%) engaged in weapons-related planning behaviors, in addition to weapons

research (see Weapons Research and Selection) and the acquisition of the weapons used in the attack (see Firearm

Acquisition section). These other activities included manufacturing explosives, modifying guns or knives, stockpiling

additional weapons, and failed attempts to acquire other weapons. Some who failed to acquire certain weapons or

materials adjusted their plans to use other weapons already acquired or more readily accessible.

A 12-year-old student shot and wounded several classmates and a school security ofcer in his middle school gymnasium

before surrendering to a teacher. Two days prior to the incident, the attacker had attempted to acquire his father’s handgun

but was unsuccessful. The night before the attack, he took a shotgun from his home and sawed off the barrel so that it

could t into his duffel bag.

Planning for the Attack

Weapons research Planning the

and selection execution of the

attack

Deceptive practices

Practicing with a

Weapons-related weapon

Documentation of Recruiting others

plans

Packing an attack

Approaching, bag

surveilling, or

researching the Researching prior

target attacks

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/2019

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/2019

21

DOCUMENTATION OF PLANS: Seven attackers (17%) documented their plans and intentions for the attack in journal

entries or other writings. These writings included hit lists, safe lists (i.e., lists of those individuals who would not be

targeted), supply lists, lessons learned from past attackers, and diagrams of school hallways.

A 15-year-old student fatally shot a classmate and injured three others at his high school before surrendering to the school

janitor. In his journal and other scattered writings, police found diagrams mapping his high school, along with written

homicidal statements and lists of chemicals, weapons, and ammunition. The attacker had also written “X Kill” on the photo

page in his yearbook and had crossed out the photographs of 26 classmates.

APPROACHING, SURVEILLING, OR RESEARCHING THE TARGET: Five of the attackers (12%) researched their targets

prior to the attack. This included surveilling the SRO in order to learn his routine, noting security camera locations,

and trying to arrange meetings with a targeted teacher.

A 14-year-old student shot and killed his father before driving to his former elementary school, where he opened re near the

playground. One elementary student was fatally shot, and at least one other student and one teacher were injured. The

attacker had researched the schedules of schools he had attended and inquired about security and the presence of SROs. He

chose to target his former elementary school due to the more robust security at his middle school, his understanding of police

response times to different schools, and the proximity of the elementary school to his home.

PLANNING THE EXECUTION OF THE ATTACK: Five of the attackers (12%) spent time carefully considering how they

would execute their attacks. They considered the “best” location to kill their intended target(s), the class period to

initiate the attack, and the route they would take through the school. One of the attackers shared his plan with

friends via social media.

RESEARCHING PRIOR ATTACKS: Five of the attackers (12%) conducted research on prior incidents of targeted

violence, including past school attacks. This research was usually conducted through online searches, or by

watching videos or documentaries of prior attacks.

A 16-year-old student used two kitchen knives to injure 19 classmates and a school security guard. The attacker selected the

birthday of one of the Columbine attackers as the date of his attack. Prior to the incident, the attacker had watched a

documentary about the Columbine shooting in an effort to “numb himself” in preparation for his planned attack.

PRACTICING WITH A WEAPON: Four attackers (10%) practiced with a weapon prior to the attack. This included one

attacker who tested his homemade pipe bombs, one who practiced loading and unloading a shotgun, and one who

practiced wearing tactical gear.

RECRUITING OTHERS: Four attackers (10%) contemplated or attempted recruiting others to help execute the acts of

violence. Two of these attackers attempted unsuccessfully to recruit a specic individual to assist with the attack.

Two others considered recruiting help but did not. One of those attackers realized that attempts for recruitment

could make him vulnerable to detection and therefore refrained from asking.

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS/ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE/2019

22

PACKING AN ATTACK BAG: Two attackers (5%) packed a supply bag prior to the incident. One of them packed

clothes, cash, and other items needed to run away from home after the attack, and the other packed additional

weapons, an energy drink, and a lollipop.

OTHER TYPES OF PLANNING: Nine attackers (22%) took steps to plan the attack in ways that were unique and

could not be categorized among the other behaviors. This included stealing money to buy weapons, deleting an

email account, and specically wearing baggy pants the day of the attack in order to conceal a weapon.

Firearm Acquisition

The primary weapons used in the 41 attacks were rearms (n = 25, 61%) and knives (n = 16, 39%). In most of the

incidents involving knives, the weapons were taken by the attackers from their kitchens or other areas of their homes.

Because knives are commonly available with little restriction, this section focuses on how the attackers acquired the

firearms used in the attacks. All percentages provided in this section are based on the 25 attackers who

used firearms.

FROM THE HOME: Nineteen attackers (76%) acquired a rearm from the home of a parent or another close relative. In

half of the firearms cases (n = 12, 48%), evidence indicates the firearm was either readily accessible, or it was not

secured in a meaningful way. For example, some rearms had been kept locked in accessible wooden or glass

cabinets, locked in vehicles, or hidden in closets. In four cases (16%), the firearms were kept in more secured

locations, but the attacker was still able to gain access to them. In these instances, the rearms were secured in

a locked gun safe or case, but the attackers were able to gain access to them because they knew the combination or

where the keys were kept, or they were able to guess the password or

combination. In three cases, it is unknown if the rearm had been secured.

A 15-year-old student fatally shot one classmate and injured three others at

his high school. The attacker knew the combination to his father’s gun safe,

from which he was able to obtain a .32 caliber semiautomatic pistol and a

semiautomatic .223 caliber AR-15 rie with a 30-round magazine. The attacker

transported the weapons on the school bus by concealing the rie and seven

extra boxes of ammunition in a golf bag. He kept the handgun in his pocket.

TIMING OF THE ACQUISITION: Eight of the attackers (32%) acquired a rearm

on the day of the attack. Five additional attackers (20%) acquired a rearm

the day before the attack, and four attackers (16%) acquired a rearm

between two and seven days prior. This nding reinforces the importance

of a swift response to situations involving students who may pose a risk of

harm to themselves or others, especially those who have access to

weapons in the home.

Juvenile Access to Weapons

Under federal law, individuals under the age

of 18 may not legally possess a handgun,

except in limited circumstances.

Federal law does not restrict the age of

individuals who may possess long guns

(e.g., shotguns and ries). Some states

have implemented additional restrictions on