7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 1 -

*This article,“FHA Insured Loans for Long Term Healthcare Facilities: Recent Developments

as a Popular Product Evolves to Meet Growing Needs”, Volume 23, Number 5, first appeared

in The Health Lawyer, an ABA publication, in June 2011.

*This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by

any means or downloaded or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the

express written consent of the American Bar Association.

FHA INSURED LOANS FOR LONG TERM HEALTHCARE FACILITIES: RECENT

DEVELOPMENTS AS A POPULAR PRODUCT EVOLVES TO MEET GROWING

NEEDS

Andrea C. Barach, Esq.

Wendy A. Chow, Esq.

1

Bradley Arant Boult Cummings LLP, Nashville, TN

I. Introduction

The “Great Recession” continues, and the commercial financial markets remain difficult

for many borrowers. In this environment, healthcare providers have continuing challenges as

they seek financing for their facilities. The financing market can be expected to continue

difficult into 2011 and perhaps beyond. For owners of long term care facilities, one bright spot

in the financing world has been mortgage financing insured by the Federal Housing

Administration (“FHA”) under Section 232 of the National Housing Act.

2

After all, what is not

to like - long terms (35-40 years), low fixed rates, no personal recourse and no required

guaranties by high-income individuals. Even better, these loans are assumable by qualified

purchasers. Of course, nothing in life is free, and in order to enjoy these benefits, borrowers

must comply with a host of specific substantive and procedural requirements.

Within the past year,

3

the volume of Section 232 mortgage loans has grown dramatically,

and new concerns have arisen, particularly from the novel “master lease” structure for portfolio

loans, and further refinements to the treatment of accounts receivable financing.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (“HUD”) developed and

adopted the Lean Processing program in 2008 and phased in its use during 2009. Initially, the

program began under the Office of Insured Health Care Facilities (“OIHCF”) and was processed

1

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Mr. Alex Fenner and Ms. Amanda Nichols who contributed

valuable research.

2

24 C.F.R. § 232 (2009). The National Housing Act of 1934 was adopted as part of President Roosevelt’s “New

Deal” in order to promote stability in the nation’s housing market by making mortgage credit more available to

homeowners by establishing a program of insuring mortgages made by private lenders.

3

Andrea C. Barach & Wendy A. Chow. Government Insured Financing Available for Healthcare Facilities—We’re

From the Government and We’re Here to Help—Really!, 13 Q

UINNIPIAC HEALTH L.J. 203 (2010).

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 2 -

out of the Seattle Multifamily Hub Office.

4

Since its adoption, and due to the increased volume

of applications, OIHCF, now known as Office of Healthcare Programs (“OHP”), has been

working to further centralize and standardize the program in order to focus more attention on the

creditworthiness of the borrower and the principals of the borrower. OHP is working toward

further standardization and modernization of the forms to be used, as well.

5

At the time of adoption, the HUD Health Systems Advisor, William Lammers, predicted

with great enthusiasm that it would become possible to close a Section 232 loan in just 30 days

from the date the application was submitted.

6

However, due to the unexpected and

unprecedented increase in application volume, despite the streamlining efforts, the processing

times have remained discouragingly long, and the average time a project application remains in

the queue has risen from four to five months to between eight to ten months.

7

With the current

economic downturn, borrowers have been turning away from the commercial financing market

and towards these insured loans in ever increasing numbers. Further increasing the volume of

applications has been the trend for larger for-profit providers to finance (or refinance) large

portfolios of projects in recent years.

8

The overwhelming success of the Lean program, and its vastly increased volume of

applications, has caused HUD to re-examine and revise some of its procedures and program

rules. This article will summarize the major provisions of these Section 232 loans and examine

some of the recent changes applicable to these popular programs for healthcare owners.

II. FHA Insured Loans For Long Term Healthcare Facilities – A Refresher on Section

232

A. Lenders and Loan Insurance Under Section 232

Section 232 of the National Housing Act

9

establishes the insured mortgage loan programs

available to owners of long term healthcare facilities, such as nursing homes, assisted living

4

U.S. Dep’t of Housing & Urban Dev., Off. of Housing, 232/223(f) LEAN Processing Training- for Lenders (2008).

5

Federal Housing Administration, HUD 2010 Annual Management Report (November 2010),

http://www.hud.gov/offices/hsg/fhafy10annualmanagementreport.pdf

(hereinafter “HUD 2010 Annual Management

Report).

6

William Lammers, Health Sys. Advisor, Office of Insured Health Care Facilities, ELA March 2007 Conference on

Financing American Hospitals Today, Section 242: Mortgage Insurance for Hospitals Overview (2007),

http://portal.hud.gov/fha/healthcare/materials/ela.pdf (hereinafter Lammers’ Presentation).

7

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, HUD LEAN 232 Program Update as of November 2, 2010,

(Nov. 02, 2010), http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/documents/huddoc?id=FHA_DOC_195.pdf.

8

In 2001 a 75 facility portfolio was approved by HUD, but there were relatively few large portfolios until fairly

recently. For example, an August 2010 closing of a 16 facility portfolio was the largest closed since 2005. Since

then, the authors are aware of several other large portfolios in the processing queue. HUD Approves Largest health-

Care Package for CFG, Inc. (Commercial), A

LLBUSINESS NEWSLETTER at 1 (June 1, 2002).; Press Release, Walker

& Dunlop, Walker & Dunlop Closes Larges HUD Healthcare Portfolio Since 2005 – Florida (August 24, 2010) on

file with author.

9

24 C.F.R. § 232 (2009).

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 3 -

facilities, board and care homes and certain other forms of intermediate care facilities. It does

not include acute care hospitals, as these facilities may be financed under programs authorized

under Section 242 of the National Housing Act

10

(which is beyond the scope of this article.)

All of the loans under Section 232 are made by one of the 92 private lenders currently

qualified as FHA lenders under the Multifamily Accelerated Processing Program.

11

After the

FHA lender underwrites and closes the loan in accordance with HUD procedures, the loan is

“endorsed” to HUD under the specific Section 232 program and the FHA insures the mortgage

loan. If the mortgage loan goes into default, the FHA lender can assign the loan documents to

HUD in return for HUD's payment of the insurance claim.

12

In general, FHA lenders may securitize the closed loans into pools of one or more

mortgage loans which are packaged and sold to investors as Government National Mortgage

Association (“GNMA”) Mortgage Backed Securities (or, more colloquially, “Ginnie Maes”).

Under the Ginnie Mae program, upon payment of a fee to GNMA and in reliance on and addition

to the FHA mortgage insurance, GNMA guaranties to the investors the timely payment of

principal and interest on the securities. Because investors will be purchasing the Ginnie Maes

and will want some assurance of the expected yields, the lender will provide for a period during

which prepayment is prohibited (so that the investor’s yield is guaranteed for a certain time

period) and thereafter prepayment is permitted but may carry a premium

13

. Using GNMA

multifamily mortgage backed securities allows an increased supply of mortgage credit because

funds from the capital markets are channeled into the mortgage market, and since GNMA

guaranties are backed by the full faith and credit guarantee of the U.S. Government,

14

the Ginnie

10

24 C.F.R. § 242 (2009).

11

HUD 2010 Annual Management Report, supra note 5, at pages 23-24. Lenders qualify as FHA lenders by

applying to HUD and demonstrating ability to meet HUD underwriting requirements, including successful

completion of required training programs offered by HUD.

12

It is interesting to note that § 232 loans were expressly excluded from the mortgages eligible for Partial Payment

of Claims (“PPC”). Although there is no explanation as to their exclusion, it is reasonable to assume that § 232

loans were not viewed as presenting the same risks as loans under other FHA programs. The PPC program allows

HUD to pay a portion of the unpaid principal balance to the lender and recast the remaining balance into a revised,

smaller loan that reflects a financially viable debt load for the property, with a new second priority mortgage in

favor of HUD securing the amount of the partial insurance payment. See, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban

Development, HUD Asset Management Handbook Chapter 14: Partial Payment of Claims (November 2010),

http://www.hud.gov/offices/adm/hudclips/handbooks/hsgh/4350.1/43501c14HSGH.pdf.

13

For example, a 35 year mortgage loan could be closed to prepayment for the first ten years, then starting in the

eleventh year prepayment would be permitted with a 3% premium, in the twelfth year with a 2% premium, in the

thirteenth year with a 1% premium and may be prepaid at par starting in the fourteenth year. Often the prepayment

prohibition may extend for a shorter period, with higher premiums once the loan is open to prepayment. A borrower

can negotiate these terms with its lender, but different prepayment terms will affect the interest rate charged by the

lender.

14

Mortgage Bankers Association, The Future of FHA and Ginnie Mae, (September 2010),

http://www.mbaa.org/files/ResourceCenter/FHA/TheFutureofFHAandGinnieMae.pdf

. See also Arthur Q. Frank &

James M. Manzi, GNMA Multifamily Research (May 1, 2003); Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Ginnie Mae

(footnote continued on following page …)

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 4 -

Mae securities are more attractive to investors, which in turn results in lower interest rates. As

an alternative to the Ginnie Mae, the lender may obtain an FHA-insured pass-through

participation certificate, which offers slightly less default protection (generally 99 percent of

principal and interest at the FHA debenture rate), but this has been less popular in recent years

since the GNMA fee was reduced.

15

B. Specific Programs within Section 232

The following is a summary of the different programs available to owners of healthcare

facilities under Section 232:

16

1. Section 232

: Financing for the acquisition or construction of an eligible

healthcare project, or substantial rehabilitation of an eligible healthcare project. Substantial

rehabilitation means either (i) the cost of repairs, replacements or improvements exceeds the

greater of 15 percent of the estimated replacement cost (after completion) or (for assisted living

facilities $6,500 per unit), or (ii) two or more major building components are being substantially

replaced.

17

2. Section 232/223(f): Financing to refinance an existing mortgage

(conventional or FHA) on an eligible healthcare project that the borrower has owned (generally

for a minimum of two years). Rehabilitation costs may be included, so long as they do not

constitute “substantial rehabilitation” as in that case it would be a Section 232 loan, not a Section

232/223(f) loan.

18

3. Section 232/223(a)(7): Refinancing of an existing mortgage that has been

insured by FHA. Like the 223(f) loans, the lenders are able to use GNMA Mortgage Backed

Securities.

C. Economics of the Loan Terms.

All of the Section 232 loans are fixed interest rate loans with terms ranging between 35-

40 years.

19

The term may be shortened if three-quarters of the remaining useful life of the

(… footnote continued from previous page)

Project Loans Maintain Affordability (August, 2003),

http://www.frbsf.org/publications/community/investments/0308/article2b.html.

15

GNMA Multifamily Research, supra note 14.

16

24 CFR §§ 200(A), 242 (2010); U.S. DEPARTMENT OF URBAN HOUSING, PROGRAMS OF HUD, available at

http://www.huduser.org/resources/hudprgs/ProgOfHUD06.pdf.

17

Guide to Multifamily Accelerated Processing (MAP), CH. 3: Eligible Multifamily Mortgage Insurance Programs

§§ 4(C)(1),(2) (2002), http://www.hud.gov/offices/hsg/mfh/map/mapguide/chap03.pdf (March 15, 2002)

(hereinafter MAP GUIDE). A “unit” in an assisted living facility is a separate residential living unit for not more

than four persons per unit or per bathroom. Nursing facilities have beds rather than units, so the cost per unit is not

used for those projects.

18

Id.

19

MAP GUIDE, supra note 17, ch.3 §§ 2 (D), (E).

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 5 -

facility is a shorter period.

20

In most cases, the loans may be nonrecourse to the borrower,

meaning that enforcement in the event of default is limited to enforcing on the collateral, which

will be a first priority mortgage on the facility and the assets associated with the facility. As

discussed later in this article, the structures used for these loans can be quite complicated, since

the facilities are commonly subject to an operating lease, and also often have obtained working

capital financing through a pledge of accounts receivable.

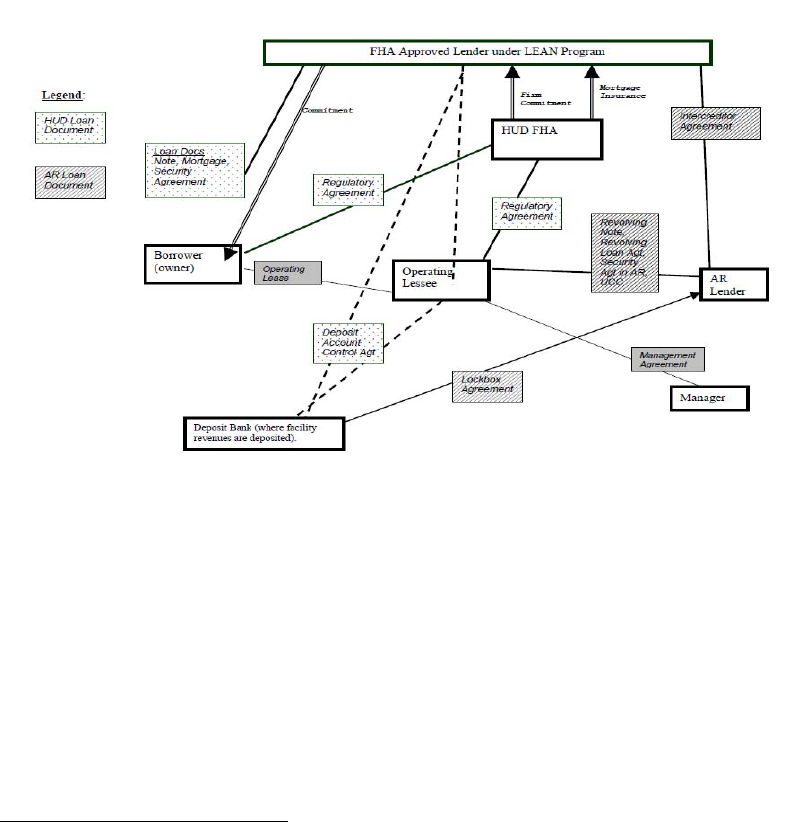

Figure 1 is a chart showing a typical structure for a Section 232 loan, including accounts

receivable financing, and shows that the structure can be quite complicated.

Figure 1.

D. Eligible Projects

Skilled nursing facilities, intermediate care facilities, board and care homes, and assisted

living facilities are “eligible projects” under Section 232.

21

In general, these facilities serve an

elderly and frail population who require some level of continuous healthcare or assistance

services, but the definition is broad enough to also include other intermediate care facilities such

as behavioral healthcare residential treatment facilities or psychiatric hospitals providing

residential care (as opposed to acute care) so long as the services are residential and are provided

under state license.

22

Eligible projects must be operated under a state license, except that in

certain states that do not license assisted living facilities, the requirement for a state license may

20

Id.

21

24 CFR § 200.3 (2010).

22

MAP GUIDE, supra note 17, ch.3 § 9 (A)(2).

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 6 -

be waived. In the underwriting process, if a certificate of need is required in the state in which

the facility is located, it must be submitted to the lender. If no certificate of need is required by

the state, then the underwriter will require some sort of market study in order to establish that

there is a demonstrated need for the services being provided by the facility. In addition, since

many facilities include both licensed and unlicensed (independent living) units, Section 232

loans may include facilities containing unlicensed independent living so long as the independent

living beds do not exceed 25 percent of the total beds in the facility.

23

E. Eligible Borrowers

To qualify for a Section 232 loan, a borrower must be a single asset, single purpose

entity.

24

It may be organized as a non-profit entity or a profit-motivated entity

25

, but in either

event, it may only own the single asset which is the subject matter of the Section 232 loan and its

organizational documents must limit its purposes to the ownership and operation of the single

asset.

1. Nonprofit vs. Profit-motivated Borrowers. Both nonprofit and profit

motivated entities may apply for FHA insured financing of eligible projects. Nonprofit

borrowers are entitled to higher maximum loan amounts than borrowers which are profit

motivated. This reflects the underlying assumption that a nonprofit borrower is not distributing

"profits" or surplus revenues from the facility to financially enrich its owners. If a loan is

underwritten on a nonprofit basis, the loan documents will restrict the borrower's ability to use

residual receipts remaining after payment of operating expenses and debt service for any

expenses other than repairs, improvements or enhancements to the project. For some nonprofit

borrowers which are part of larger organizations, this can prove problematic. The nonprofit

borrower may desire to use cash on hand in one facility to assist another facility within the same

nonprofit group of entities, but may not do so if the facility has been financed with a Section 232

loan as a nonprofit.

2. Leased Projects. Under Section 232, an eligible project may be leased to

an operating lessee so long as both the lease and the operating lessee are approved by HUD. The

operating lessee will hold the license from the state, be responsible for the day-to-day operation

of the facility, and receive payments for services to the patients or residents of the facility in due

course. The operating lessee may be affiliated with the mortgagor owner, or it may be an

unrelated third party, although it is quite common for the owner which obtains the Section 232

financing to lease the facility to an affiliated operating lessee for a rental amount equal to the

debt service plus real estate taxes as well as insurance and a small reserve. Operating leases

must comply with HUD requirements, including a requirement that the operating lease may not

23

MAP GUIDE, supra note 17, ch.3 § 9.

24

MAP GUIDE, supra note 17, ch.3 §2(B).

25

The term “profit-motivated” rather than “nonprofit” refers to the fact that a nonprofit facility owner may elect to

be considered as a “profit-motivated” borrower rather than being underwritten as a nonprofit borrower and being

subject to more restrictions on distribution.

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 7 -

be assigned without HUD prior approval, any change in bed authority requires HUD consent,

and nonprofits may only lease to other nonprofits.

26

Planning Point: Because operating lessees are not required to be single purpose, single

asset entities, sometimes several facilities may be leased to the same operating lessee. If a

facility owner owns more than one facility in the same entity and desires to refinance using

Section 232 mortgage loans, one way to meet the requirements under the Section 232 program is

to form new entities to hold each of the facilities and then have the new entities lease each

facility to the original owner, which will now be the operating lessee for all of the facilities that it

once owned outright. Depending on the state laws concerning healthcare licenses, this process

may not require full re-licensure of each of the facilities and thus may be very attractive for

certain borrowers.

3. Managed Projects. An eligible project may be managed by a management

agent (either affiliated or independent) under a separate management agreement. All agreements

must permit HUD to require the owner to terminate the management agreement (i) immediately

in the event of a default under the loan documents attributable to the management agent (ii) upon

30 days written notice for failure to comply with the provisions of the management certification;

or (iii) when HUD becomes mortgagee in possession after the loan has been endorsed to HUD by

the lender.

27

Upon any such termination, the management agent must turn over all the project’s

accounts, investments and records to the owner immediately (but in any event within 30 days),

and the owner must agree to make arrangements for acceptable alternative management of the

project. One requirement that can be troublesome in certain instances is the requirement that

there not be any “hold harmless” clause that excuses the manager from all liability for damages

and injuries.

28

4. Previous Participation Clearance – Who Must Be Disclosed? All entities

and principals of entities that expect to be a borrower, operating lessee, or manager of an eligible

project must be cleared in a process which verifies that each such entity (or its owners, directors

or officers) have not participated in other FHA insured financing which is in default.

29

In

general, the “principals” required to submit Previous Participation Certificates (also known as

HUD-2530 Forms) are, in addition to the entity itself, (i) the entity’s executive officers (defined

as the President, Vice President, Secretary, Treasurer and any other executive officers who are

directly responsible to the Board of Directors or equivalent governing board); (ii) any of its

general partners (with any ownership interest) for entities that are partnerships; (iii) for entities

that are limited partnerships, limited partners with 25 percent or more ownership interest; or (iv)

stockholders of any entity which is a corporation or LLC members for any entity which is a

limited liability company with, in either case, 10 percent or more ownership interest.

30

HUD

26

MAP GUIDE, supra note 17, ch.3 § 9(G).

27

MAP GUIDE, supra note 17, ch.10 § 6(A).

28

Id.

29

MAP GUIDE, supra note 17, ch.10 § 6.

30

MAP GUIDE, supra note 17, ch.10 § 8.3(D); See also 24 CFR § 200.215(e)(2) (2010).

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 8 -

strongly encourages the submission to be made using its APPS online electronic submission

format which requires obtaining enrollment credentials from HUD.

5. Regulatory Agreement. All FHA-insured loans require the borrower and

any operating lessee, and sometimes the management agent, to sign a Regulatory Agreement.

31

The Regulatory Agreement provides, in general, that the project may be used only for the

specific use stated, that the borrower must be a single asset entity, and that there may be no

discrimination in the services provided to the residents or patients. In addition, the Regulatory

Agreement provides that there must be reserves for replacement, establishes required record

keeping and accounting procedures, and provides that any transfer of the project requires the

prior consent of HUD. The Regulatory Agreement is executed by the project owner (or lessee,

as the case may be) and HUD. Any violation or event of default under the Regulatory

Agreement entitles HUD to take over the note and mortgage documents and, eventually,

foreclose on the project. The Regulatory Agreement is placed of record immediately after the

mortgage is recorded. The Regulatory Agreement will contain limitations on the use of residual

receipts (for nonprofit borrowers) or surplus funds (for profit-motivated borrowers). Nonprofit

borrowers, in particular, will be forbidden to use residual receipts for any purposes (even

purposes otherwise within the charitable purpose of the nonprofit) other than specific project

needs, without the prior consent of HUD.

F. Eligible Costs – No Equity Take-Out

The principal amount of any Section 232 loan will be limited to the total amount of

eligible costs. This is very important, because no return of equity is permitted from the proceeds

of a Section 232 loan.

32

Thus, if an owner of a facility has built up substantial equity in the

facility (which may occur if there has been substantial amortization over a number of years under

the facility's existing financing, or may occur as the result of increases in market value overall),

the Section 232 loan will be limited in amount to the proceeds necessary to repay the prior loan

and pay approved closing costs. Some lenders will make a "bridge" loan to a facility, which will

have a term of one to two years. In the initial bridge loan closing, if there is sufficient value to

support a larger loan the borrower can receive a return of equity, and then, when the bridge loan

is refinanced with a Section 232 loan, there would not be any return of equity. The period of

time between the closing of the bridge loan and its eligibility to be refinanced under Section 232

is sometimes referred to as the "seasoning period," and there are detailed requirements

concerning the length of time that a loan must be "seasoned" and the nature of debt which may

be refinanced with the proceeds of a Section 232 loan.

33

Affiliate debt, consisting of loans made

by an affiliate of the borrower to the borrower, may not be refinanced with the proceeds of a

Section 232 loan in any event. In addition, the debt that may be refinanced must be directly

31

MAP GUIDE, supra note 17, ch.3 § 2(A).

32

MAP GUIDE, supra note 17, ch.3 § 11(J).

33

U.S. Department of Housing & Urban Dev., Office of Housing, 232/223(f) LEAN Processing Training for

Lenders (2008).

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 9 -

related to the project, such as purchase, construction, capital improvements, working capital

associated with the project, and similar project-related expenses.

34

G. Maximum Loan Amount

The statutory maximum loan amounts range from 85 percent to 95 percent of the

appraised value of the project, subject to other limiting factors. Recently, the limits have been

reduced to reflect negative market experience in an effort to reduce future loan defaults. Under

the recent reductions, the loans will range from 75 percent to 90 percent of appraised value.

Even with the revised, lower limits, it is clear that Section 232 loans remain a very attractive

financing alternative for many long-term care facilities. The HUD underwriter will determine

the maximum loan amount in the application process. There are three criteria which will limit

the maximum amount of the loan. The test which results in the lowest amount will set the

maximum loan amount.

1. Appraisal Criterion. In the underwriting, an appraisal of the facility will

establish an appraised value. Based upon the type of facility and the type of borrower, skilled

nursing, assisted living, for profit or not-for-profit, the maximum loan amount under this test will

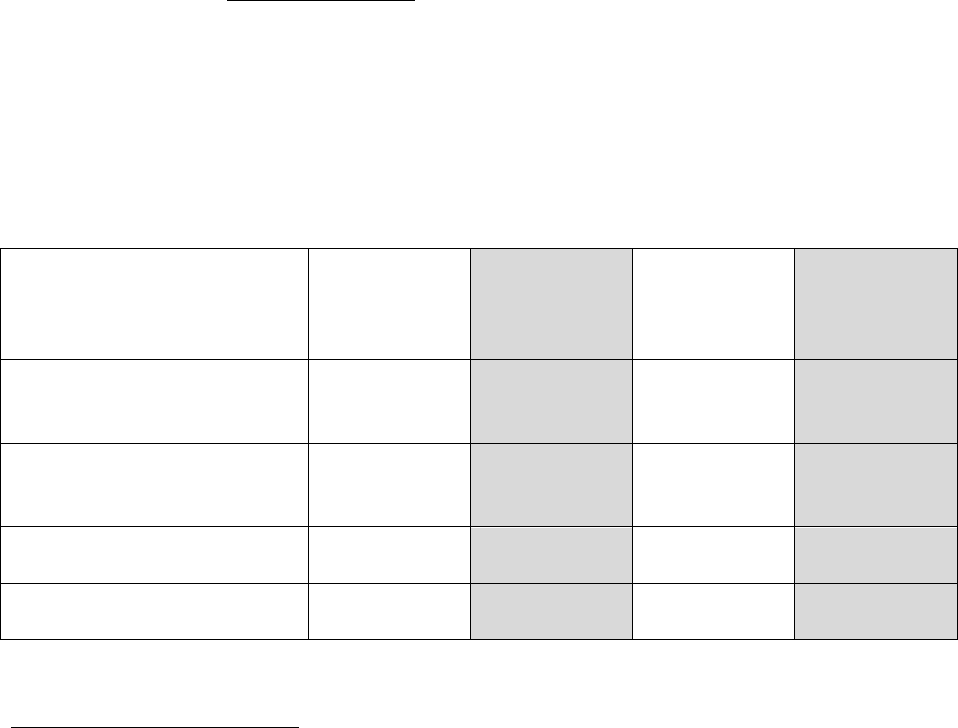

be between 75 percent and 90 percent of the appraised value. As seen in this table, HUD has

lowered the maximum amount of the loans across the board.

35

In addition, due to negative

experience in the assisted living segment of long-term care, HUD has further reduced the

maximum loan amounts for assisted living facilities. These reductions are not statutory, and in

certain cases it may be possible to apply for a loan in excess of these limits if there are suitable

mitigating factors.

Type of Entity Loan

Skilled

Nursing –

Revised

Guidelines

Skilled

Nursing

(statutory

limits)

Assisted

Living-

Revised

Guidelines

Assisted

Living

(statutory

limits)

New construction or

substantial rehab - for profit

borrowers

80 percent 90 percent 75 percent 90 percent

New construction or

substantial rehab – nonprofit

borrowers

85 percent 95 percent 80 percent 95 percent

Refinance or acquisition - for

profit borrowers

80 percent 85 percent 80 percent 85 percent

Refinance or acquisition –

nonprofit borrowers

85 percent 90 percent 85 percent 90 percent

34

Id.

35

U.S. Dep’t of Housing & Urban Dev., HUD’s LEAN 232 Program Office of Insured Health Care Facilities

(OIHCF): Update as of February 19, 2010.

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 10 -

This test is fairly easy to apply and in these authors' experience, is generally the limiting factor to

the size of the loan. For example, if the borrower owns a skilled nursing facility that appraises at

$10 million, and desires to refinance that facility with a Section 232 loan, if the borrower is

profit motivated, the maximum loan size, under the revised sizing rules, will be 80 percent of the

appraised value, or $8 million. If the borrower in question is non-profit, then the maximum loan

size would be 85 percent of the appraised value, or $8.5 million.

2. Eligible Costs Criterion. As discussed above, the proceeds of a Section

232 loan may be used only to pay eligible costs.

3. Debt Service Coverage Criterion

. For all projects financed under Section

232, the current guidelines require a minimum debt service coverage ratio of 1.45.

36

This

represents a tightening of requirements from the statutory requirements set forth in the MAP

Guide that requires debt service for Section 232 loan not to exceed 90 percent (for profit-

motivated mortgagors) or 95 percent (nonprofit mortgagors) of the project’s estimated net

earnings attributable to realty and nonrealty (excluding proprietary earnings) and for Section

232/223(f) loans not to exceed 85 percent of the project’s estimated net income for profit-

motivated borrowers, or 90 percent of estimated net income for nonprofit borrowers.

37

If the

project is exempt from real estate taxes, then the mortgage can exceed the debt service limit by

capitalizing the savings from any such tax abatement, so long as the tax abatement runs with the

land (not with the sponsor) and the additional mortgage amount supported by the abatement must

be amortized over the life of the abatement.

38

Since the statutory minimum debt coverage is less

strict, it is possible to submit an application with less coverage, but it would need strong

mitigating factors in order for it to be approved.

H. Secondary Financing

The Section 232 insured mortgage must be secured by a first priority mortgage or deed of

trust on the project. In addition, there are strict rules on the types of subordinate financing that is

allowed to be secured by liens subordinate to the insured mortgage. In general, the only types of

permitted secondary financing are the following:

1. Surplus Cash/Residual Receipts Note. Subordinate financing which is

payable only from residual receipts (for nonprofit borrowers) or surplus cash (for profit-

motivated borrowers) with a maturity date not earlier than the final maturity date of the Section

232 loan is permitted under certain circumstances. Any such note evidencing such a loan must

be on form FHA-2223 (“Surplus Cash Note”) or, for nonprofit borrowers, must be form FHA-

1710 (“Residual Receipts Note”).

39

These form notes are not negotiable and must be used

without any alterations. The term of the note must not be any shorter than the FHA insured

mortgage note, and repayment of principal and payment of interest is limited to surplus cash or

36

Id.

37

MAP GUIDE, supra note 17, ch. 8, § 8(A)(1)(c).

38

Id.

39

MAP GUIDE, supra note 17, ch.8 §10(A).

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 11 -

residual receipts (as those terms are used in the Regulatory Agreement). Unpaid interest may be

accrued, but failure to pay interest may not be an event of default.

40

The amount of the note,

must not exceed the amount that, when added to the FHA insured loan, does not exceed 92.5

percent of the fair market value of the project determined in the underwriting of the FHA insured

loan.

41

Any pledge of cash flow may not exceed 50 percent of the surplus cash or residual

receipts of the project. The note may be secured by a second priority mortgage, but only to the

extent that it is closed at the same time as the FHA insured first mortgage, and the second

mortgage may not be foreclosed at any time before the termination of the first mortgage, and

may not include any sort of cross-default provision with the first mortgage.

42

As a practical

matter, these terms are unlikely to be attractive to most commercial lenders or banks.

2. Governmental Secondary Financing

. If the secondary loan is provided by

a governmental agency or instrumentality the amount can be higher – up to 100 percent of the

difference between the FHA insured loan and the fair market value.

43

This would include

501(c)(3) tax exempt bonds issued by nonprofit organizations as well as other forms of tax

exempt financing. Even so, the other restrictions on the terms of the financing still apply. Also,

no additional subordinate financing is permitted (i.e., no third mortgages).

3. FHA Insured Supplemental Financing under Section 241. If a project

needs additional financing after the closing of the initial loan under Section 232, in certain

circumstances supplemental FHA financing secured by a second lien mortgage is available under

Section 241, which is the program under which FHA will insure supplemental loans for projects

which have already been financed with FHA insured first mortgages. The reasons for a Section

241 supplemental loan vary. Sometimes they are used to finance renovation or construction

costs (such as an expansion wing or major reconstruction) when such additional construction is

required and the original Section 232 loan remains closed to prepayment and thus cannot be

refinanced. For example, if conditions or regulatory requirements change after the original

insured loan has closed, the borrower may have an urgent need for renovation in order to

maintain regulatory compliance and it is rather difficult to obtain commercial secondary

financing due to the requirements under the Section 232 program discussed in section 1 above.

Section 241 loans are also processed under the Lean program, and in general have similar

requirements as the Section 232 requirements.

4. Accounts Receivable Financing

. In general, the FHA financing must be

secured by a first priority security interest in the accounts receivable of the project. However, as

discussed in more detail in part III(D) of this article, qualified accounts receivable financing may

be secured by priority liens in the project accounts receivable with the FHA financing to be

secured by subordinate liens in the project accounts receivable.

40

See Form FHA-2223 (2010), available at http://www.hud.gov/offices/adm/hudclips/forms/fhaforms.cfm.

41

MAP GUIDE, supra note 17, ch.8 §10(B).

42

MAP GUIDE, supra note 17, ch.8 §10(D.

43

MAP GUIDE, supra note 17, ch.8 §10(B).

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 12 -

I. Sale of Project, Change of Ownership, Assumption of Loan

1. TPA Process – Sale of Project. Most conventional loans include a “due-

on-sale” clause which provides that if the collateral for the loan is sold (or for any reason no

longer owned by the borrower) the entire loan is immediately due and payable. This means that

for conventionally financed projects, when the project is sold, the buyer must obtain its own new

loan, and the proceeds of the new loan will be used to pay the purchase price and allow the seller

to pay its prior loan in full. FHA insured financing may be assumed by a purchaser of the

financed facility in certain cases. The procedure for approving the transfer is called “TPA”

which stands for “Transfer of Physical Assets.” In overview, the TPA process allows HUD to

underwrite the credit of the proposed new owner of the facility, but it is substantially simpler

than obtaining the original FHA insured loan in the first place. This is because the TPA process

contains a lesser amount of facility underwriting, as the facility itself will have already been

approved when the initial loan was made. The checklist for TPA submissions includes the same

data about the new purchaser assuming the loan as would be submitted with a new application in

order to establish that the purchaser is an eligible borrower, but there are fewer requirements

concerning the facility itself, as the facility has already been determined to be an eligible

project.

44

2. Modified TPA - Changes Short of a Sale. The Regulatory Agreement and

other loan documents executed at the initial closing of a Section 232 loan will require that any

change of ownership, change of identity or change in control of the borrower, the operating

lessee or the manager requires HUD's prior written consent. The process of obtaining consent to

a change in control is called the modified TPA process. In most cases, the facility is not

changing ownership, and thus there will be no deed or other transfer document recorded. Rather,

there may be a new lessee, or a new manager. HUD processes these requests using the same

checklist of submission items that is uses for a full TPA request, except that not all of the

checklist items are applicable.

III. Recent Developments – A Magical Mystery Tour of Outstanding Hot Issues

A. Popularity of 223(a)(7) Refinancing Loans

The FHA Section 223(a)(7) program is a streamlined refinancing program that is limited

to the refinancing of multifamily properties (including healthcare facilities, under Section

232/223(a)(7)) already subject to mortgage finance insured by FHA. This is not a new program,

and is not limited to healthcare facilities. Because it allows borrowers to “reset” their interest

rates to take advantage of current low rates, it has become more popular recently for owners of

healthcare projects. This recent popularity may be a factor driving the increased volume of HUD

insured loans that has been causing processing delays.

45

The borrower can refinance at current

44

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Loan Modification (Interest Only) Checklist (2010),

http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/documents/huddoc?id=LoanModi_Checklist.doc.

45

HUD’s LEAN 232 Program Office of Healthcare Programs Update, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban

Development (January 25, 2011). OHP acknowledges the “rapidly increasing volume” of these loans and

establishes revised processing queues.

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 13 -

market rates with a loan up to the original principal amount of the prior mortgage which will be

for a term co-terminus with the prior mortgage, or, based on an acceptable property inspection,

for a term equal to the original term of the prior mortgage. Naturally, this is only possible if the

prior loan has been in existence for long enough that it is past any period for which prepayment

is forbidden.

In the past, there has been less incentive for a borrower incurring the transaction costs

required to refinance under Section 223(a)(7), particularly when a refinance under Section 223(f)

allows an increased loan amount to cover repairs and renovations. However, interest rates are at

historic lows, and a Section 223(a)(7) loan may be offered at rates in the 4 percent-4.5 percent

range. If the prior Section 232 loan was at 7 percent, for example, the debt service savings

would be substantial. Also, if the prior loan has been in place for a number of years, the

amortization is sufficiently large enough that the difference between the original principal

amount and the current payoff amount will cover the closing and transactional costs. For these

reasons, the volume of (a)(7) financings has been growing.

B. LEAN Processing Revisions and Queues

The Lean processing program began in 2008, and during the 2008 fiscal year (ended

September 30, 2008) FHA insured mortgages (under Section 232) for 189 projects containing

21,679 beds for a total of $1.2 billion.

46

The volume has increased each year thereafter. During

the 2009 fiscal year (October 1, 2008 through September 30, 2009) HUD processed 271 loan

applications for healthcare facilities under Section 232 and insured mortgages for 255 projects

containing 30,155 beds for a total of $2 billion.

47

During the 2010 fiscal year, the volume of

applications rose 283 percent over the prior year, with the result that in fiscal year 2010, HUD

processed 768 applications under Section 232 and endorsed 309 loans totaling $2.6 billion

covering 35,789 beds.

48

As of October 1, 2010 there were 255 applications in the processing

queue. It may be said that the program has been a victim of its own success, as increasing

numbers of borrowers file applications to take advantage of the attractive loan terms.

The initial response to the volume increase was to establish two separate channels for

processing.

49

Initially, the so-called “Green Lane” queue was established for Section 223(a)(7)

refinancing loans so that these simpler deals could speed through the HUD process, and then the

“Green Lane” was expanded to include other Section 232 loans that presented lower risks, which

46

Mortgage Insurance for Nursing Homes, Intermediate Care, Board & Care and Assisted-Living Facilities;

Section 232 and Section 223(f), U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (December 30, 2009),

http://www.hud.gov/offices/hsg/mfh/progdesc/nursingalcp232.cfm.

47

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Description of HUD Programs, (February 17, 2011)

http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD?src=/federal_housing_administration/healthcare_facilities/mortgage_insurance

/about_the_office_of_healthcare_programs.

48

HUD 2010 Annual Management Report, supra note 5 at pages 23-24.

49

HUD Update as of November 2, 2010, supra note 7; Cambridge Provides $6.03 Million HUD Lean Mortgage

Loan to Refinance Crystal Pines Nursing Home in Crystal Lake, Illinois, Cambridge Realty Capital Companies

ePulse Newsletter (December 2010).

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 14 -

were defined to be projects which met each of the following criteria: (i) risk assessment criteria,

(ii) no regulatory waivers requested, (iii) no outstanding or unresolved underwriting issues, and

(iv) (beginning in August, 2010) all forms 2530 being filed electronically through APPS. The

remaining applications were assigned to the regular lane (perhaps the “Red Lane” is an

appropriate, though not official, moniker). The goal was to speed the simple projects through the

Green Lane, and the intent was to keep processing queues, at least in the Green Lane, down to an

acceptable wait time. However, during 2010, the great popularity of these loans meant that even

Green Lane waiting times were increasingly long.

Beginning in November 2010, and in response to the rapidly growing waiting times in

processing (from approximately four months to up to ten months in October 2010), the HUD

Office of Healthcare Programs has established five separate processing queues, and a given

application will be assigned to one of these five queues depending upon the kind of application.

These queues are:

223(f) Regular Queue – Section 232/223(f) projects (refinancings) that do not meet Green

Lane criteria

223(f) Green Lane Queue – Section 232/223(f) projects that meet Green Lane criteria and

are not part of a Large or Midsize Portfolio

223(f) Portfolio Queue – Projects that are part of a Large or Midsize Portfolio which has

been previously approved under HUD Notice H 01-03, as discussed below

Other Program Queue – Projects under Section 232 New Construction or Substantial

Rehabilitation, Section 241(a) Supplemental Loans and Section 232 Blended Rate applications.

These projects are not as common and can be more difficult to underwrite; creating a separate

queue for them was intended to speed the other queues.

223(a)(7) Queue – Projects that were financed under Section 232 in the past, and are now

being refinanced with no new proceeds or increased loan amount. As of January 2011, the

Section 223(a)(7) queue has been divided between an (a)(7) “Green Lane” for all (a)(7) loan

applications that do not propose any extension of the loan term, do not include accounts

receivable financing, and do not involve any change of entity, and with the remaining (a)(7) loan

applications to remain in the “standard” (a)(7) queue.

50

Based on the analysis performed by the OHP in October 2010, OHP believes that the

processing queues should level off at an eight to nine month level for most queues.

51

In order to

prevent large portfolios from creating “bottlenecks”, OHP has also changed the rules to require

all members of the portfolio to have complete applications before being assigned a place in the

50

U.S. Dep’t of Housing & Urban Dev., HUD’s LEAN 232 Program Office of Insured Health Care Facilities

(OIHCF): Update as .January 25, 2011.

51

U.S. Dep’t of Housing & Urban Dev., HUD’s LEAN 232 Program Office of Insured Health Care Facilities

(OIHCF): Update as of November 2, 2010.

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 15 -

queue.

52

Before this change, a portfolio could submit one complete application as a placeholder,

and then work on the remaining applications while the placeholder application was in the queue,

moving up the line. Delays arose because if there were application problems, or incomplete

items in the applications that were then submitted once the placeholder was at the front of the

line, processing would slow or stop while these application deficiencies were remedied.

C. Portfolios and the Master Lease Structure – New Ways to Manage Risk

1. Market Risk Issues. In the past, the FHA insured loan programs were of

most interest to the smaller companies which often own a single facility, or at most two or three

facilities. In part, this was because these smaller companies, many of which are nonprofit, have

always had more difficulty accessing the commercial financing markets due to lower

capitalization and less solid credit. However, in the past few years, the larger healthcare

companies which own and operate chains of facilities have increasingly turned to FHA insured

financing. Instead of loans for one facility at a time, or two or three, the applications have

included an entire portfolio of facilities. This trend has led HUD to review its procedures for

processing portfolio loans. Unlike commercial lenders, it is a statutory requirement that each

insured mortgage loan is made to a borrower which only owns the single project being financed.

Thus, a portfolio of projects would be financed with a group of individual mortgages to each

individual affiliate which would be closed together on parallel terms but would not otherwise

share any security or payment obligations. In recent years, HUD has realized that its mortgages

will be more secure if it develops a structure to allow the stronger facilities within a portfolio to

support the weaker ones.

There are two elements of risk that can cause a loan to go into default: (i) risk associated

with the particular borrower’s credit, and that borrower’s particular project and its operations;

and (ii) general market risk caused by the overall economy in which the project operates. The

first category of risk is the reason for detailed underwriting of any loan, with consideration to the

specific operating environment of each facility and the borrower’s credit status. To the extent

that a loan is secured by a portfolio of projects in different areas, with different operational risks,

the overall loan risk can be reduced. The second category, general market risk, is very hard to

avoid, as all operators will be facing the same global concerns of Medicare and Medicaid

regulations and rates, for example. However, two facilities in two different geographic areas

may face quite different challenges for certain matters, such as the availability of employees

willing to work at a long term care facility. For these reasons, commercial lenders often require

that a loan be secured by liens on a group of facilities rather than a single facility.

Perhaps in counterpoint, however, when a portfolio of facilities is owned by the same

organization (albeit in different affiliated entities) there is an enhanced credit risk because the

entire portfolio will be subject to an adverse credit effect on the parent entity. Thus, although in

some respects a portfolio improves the overall credit, there is also the increased risk of

concentrating the financing into a related portfolio. If HUD were to approve FHA insurance for

three separate facilities, owned by three separate borrowers, it would expect that the credit risk

52

Id.

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 16 -

inherent to one of these borrowers would be independent from each of the other borrowers.

However, if all three borrowers were in fact indirectly owned by the same parent company, an

adverse financial event that affected the parent company could adversely affect all three

borrowers, and thus the level of risk insured by the FHA insurance would be higher than

anticipated.

2. Traditional Portfolio Processing. Packages of loan applications for

multiple facilities owned by affiliated companies have created issues for HUD for a number of

years. HUD’s rules for underwriting portfolios of loans for facilities under affiliated ownership

were summarized in Notice H 01-03 which was issued in 2001.

53

Part of the application package

for any Section 232 loan includes a HUD Form H 01-03 which requires the borrower to set forth

all projects owned by affiliates seeking FHA insurance within an 18 month period before and

after the submission date. Use of this form allowed HUD to determine if, in fact, there was going

to be a portfolio of projects ultimately submitted, and if so, HUD could use its portfolio

processing rules for underwriting instead. It is interesting to note that even as early as 2002,

industry insiders were aware that HUD personnel were becoming concerned with the risks of

portfolio loans and realized that FHA lenders needed to pay very careful attention to ensure that

borrowers accurately disclosed their intentions for multiple facility portfolios.

54

A medium size portfolio is 11 or more properties with a total insured financing in excess

of $75 million. For medium size portfolios, in addition to the underwriting of each facility, HUD

requires a rating agency review of corporate credit to be approved by the headquarters office of

HUD. Large size portfolios are portfolios (of any number of properties) in which the total

insured financing is in excess of $250 million. For large size portfolios, in addition to the rating

agency review of corporate credit, the rating agency must perform a standardized three-part

analysis including corporate credit, site visits, and status and performance review of properties

and lines of business on all other assets held by the principals of the borrower's ownership group

which must be approved by HUD headquarters

55

.

3. New Master Lease Structure. As HUD officials realized that the existing

portfolio underwriting procedures might be insufficient to reflect the risk of a very large insured

loss if a single adverse event applied to an entire portfolio of insured loans, they sought

additional ways to mitigate risk. Although credit exposure of a portfolio of loans which were

cross-collateralized and cross-defaulted would be stronger than the traditional loan structure of

single loans to single purpose borrowers, the structure of FHA insured financing prohibits the

53

HUD Notice H 01-03, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, (2001)

http://www.hud.gov/offices/adm/hudclips/notices/hsg/03hsgnotices.cfm

. HUD Notice H 01-03 requires the

submission of a Form 01-03 which discloses to HUD all projects that are expected to be submitted to HUD within a

36 month window (18 months before the application through 18 months after application) so that HUD can evaluate

the portfolio risk rather than simply looking at each project separately.

54

An Update of Legislative and Miscellaneous Federal Healthcare Matters, MORTGAGE BANKERS ASSOCIATION

BULLETIN 02/9 (Healthcare Financing Study Group Committee on Government Programs) September 24, 2002, at 2.

55

HUD Notice H 01-03 supra note 53, Section V describes the credit analysis process for medium and large size

portfolios.

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 17 -

sort of pooled collateral that is commonly used by commercial lenders. Therefore, HUD

officials worked with certain experienced healthcare FHA lenders to develop a new structure to

allow members of a portfolio of facilities to offer credit support to one another, while still

maintaining the statutory requirements that Section 232 loans be made only to single purpose

single asset entities. Projects proposed for financing that are affiliated by common ownership

among the owners or the operating lessee must now receive written approval from HUD, and

HUD has the right to require that they be processed under the newly created master lease

structure.

56

Under the master lease structure, each of the facilities in the portfolio is owned by a

separate single purpose, single asset entity. Each facility owner leases its facility to a single

master tenant. The master tenant then enters into separate subleases to a separate operating

company for each of the facilities. The operating company holds the license to the facility, is

responsible for day-to-day operation of the facility, and, as license holder, receives the payments

for services at the facility. Each of the operating lessees enters into a cross-guaranty agreement

guaranteeing to the master tenant the performance under the subleases. In general, each of the

facility owners, the master tenant, and each of the operating lessees are all affiliates under

indirect common ownership. The rents paid by the master tenant to each of the facility owners is

calculated to equal the debt service, real estate taxes and insurance allocable to that facility, plus

a small reserve. Likewise, the sub-rent paid by each operating lessee to the master tenant is a

similar amount. Since the performance by the subtenants has been guaranteed by all of the other

subtenants, however, the master tenant has the operations of all the facilities securing its receipts

of sub-rent. Therefore, as a practical matter, the operations of all of the facilities are supporting

the loans made to each facility, and this structure accomplishes the goal of improving the credit

of each facility loan. Figure 2 illustrates the structure, as applied to a three facility portfolio.

56

HUD Addendum to Operating Lease, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (June 15, 2010),

portal.hud.gov/hudportal/documents/huddoc?id=FHA_DOC_85.doc.

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 18 -

Figure 2

4. Legal Risks of Master Lease Structure.

The master lease loan structure is

relatively new and has received mixed reviews. On the one hand, some borrowers welcome the

opportunity to create a pool of facilities to spread the risk of adverse financial consequences.

Other borrowers, however, fear that the rather complicated contractual structure in the master

lease financing may create liability risks. Borrowers fear that the contractual relationships

established by the master lease, the subleases, and the cross-guaranty could allow a plaintiff

against one facility to claim assets of the other facilities to satisfy its claim. For example, using

the structure shown on Figure 2, suppose that a tort plaintiff were to have a claim against

Subtenant 1 arising from an injury that occurred at Facility 1. Could a plaintiff somehow reach

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 19 -

the assets of Subtenants 2 and 3, or even Owners 2 and 3, as a result of the master lease contracts

in place?

(a) To Pierce or Not to Pierce – the Corporate Veil? The legal

argument for liability is a doctrine known as “piercing the corporate veil.” The doctrine rebuts

the general proposition that corporations are separate legal persons and holds a parent

corporation liable for the obligations of its corporate subsidiary, and holds its shareholders liable

for the subsidiary’s corporate obligations.

57

Could an enterprising plaintiff claim that because

the Master Tenant is a common parent of all three Subtenants, and because all three Subtenants

have guaranteed all three Subleases, that the separate corporate existences of all three

Subtenants, and perhaps even all three Owners, can be disregarded (thus their corporate veils

against liability are “pierced”), thus allowing the plaintiff access to the assets of all these other

entities to satisfy its claim?

Courts usually pierce the corporate veil in situations in which the corporate parent and its

subsidiaries have failed to conduct their operations as actual separate entities. Often there are

assertions of wrongful intent, with the result that a successful plaintiff may have its claims

payable both from the subsidiary and its parent, as if they were not distinct, separate legal

entities. The master lease structure, however, is rather more complicated. Referring again to

Figure 2, liability against Subtenant 1 must first reach upstream to the parent (Master Tenant)

and then back downstream to the other subsidiary entities (Subtenant 2 and Subtenant 3). While

traditional veil-piercing doctrine allows recovery against an upstream entity like a shareholder or

corporate parent, there are two derivative doctrines which allow veil-piercing in other situations.

The first doctrine, “reverse piercing” holds a corporation or subsidiary liable for the obligations

of its stockholders or parent. The second doctrine, “single business enterprise” theory,

disregards the corporate identities of an entire group of entities, treating the whole group as one

enterprise liable for the debts of all of its members.

58

Returning to the master lease structure on Figure 2, consider the application of these

doctrines. Using only the traditional veil-piercing doctrine, a plaintiff against Subtenant 1 could

recover only against two entities: Subtenant 1 and (only if successful in its piercing argument),

its parent entity (“Parent Corp”). However, by using the derivative doctrines described above,

the enterprising plaintiff could pursue other affiliated entities in one of two ways. He might

pierce to reach Parent Corp and then reverse pierce to reach a different affiliated subsidiary, such

as Subtenant 2. Or, he could ask the court to disregard all of the separate forms within a group of

subsidiaries under the single business enterprise theory. It is important to note that there is

currently no case authority that considers structures such as the master lease structure on Figure

2, and thus it is very difficult to determine if such approaches have any realistic chance of

success, or if they remain merely interesting law school hypotheticals. In practice, the

determination whether a subsidiary could fit into a “single business enterprise” group or be

accessed by reverse piercing may well depend on veil-piercing rules that differ across

jurisdictions.

57

See 18 AM. JUR. 2d Corporations §47 (2010).

58

See Green v. Champion Ins. Co., 577 So. 2d 249, 259 (La. Ct. App. 1991).

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 20 -

Some jurisdictions require fraud or similar abuse of the corporate form on the part of an

entity before its corporate veil can be pierced. In other jurisdictions, a sufficiently close

relationship between two entities will allow veil-piercing even absent evidence of misconduct.

Under the former rule, typical negligence actions are less likely to trigger veil-piercing.

59

A

2009 bankruptcy court discussed this distinction in detail, contrasting Colorado’s “control-and-

wrongdoing requirement” with New York’s more permissive “control-or-wrongdoing rule.”

60

(b) Specific State Law Provisions. The outcome of a claim to pierce

the corporate veil will depend on the applicable state law. While it is not practical in this article

to conduct a 50 state survey, it may be helpful to examine specific state case law precedent for

four states to illustrate the way that the doctrine is applied in different jurisdictions.

(i) Tennessee. Since 1979, the Tennessee Supreme Court has

recognized an “instrumentality rule” to determine whether a parent corporation may be held

liable for the debts of its subsidiary. In Continental Bankers Life Insurance Co. of the South v.

Bank of Alamo,

61

the Court listed a three-factor test: (1) the parent corporation, at the time of the

transaction I question, exercises complete dominion over its subsidiary, via financial control and

authority over policy and business practice to the extent that the corporate entity, as to that

transaction, had no separate mind, will or existence of its own; (2) such control must have been

used to commit fraud or wrong, to perpetuate the violation of a statutory or other positive legal

duty, or a dishonest and unjust act in contravention of third parties' rights; and (3) the aforesaid

control and breach of duty must proximately cause the injury or unjust loss complained of.

62

The Tennessee Supreme Court has recently affirmed this test.

63

Tennessee courts have never

embraced a single business enterprise theory, so plaintiffs attempting to recover against sibling

entities will rely on a two-step reverse piercing process. Even the first step—reaching the

corporate parent—will prove difficult as the Continental Bankers test requires both control and

wrongdoing. To satisfy the first prong, a plaintiff would have to trace the subsidiary’s alleged

negligence to some business decision of the parent. To satisfy the second prong, a plaintiff

would further have to show that the parent isolated its subsidiary in an attempt to avoid

responsibility for negligence to which it contributed. Even if a plaintiff succeeded against the

59

See, Town Hall Estates Whitney, Inc. v. Winters, 220 S.W.3d 71 (Tex. Ct. App. 2007) (in a suit against a nursing

home, holding that piercing the corporate veil required “something more than mere unity of financial interest,

ownership and control.”).

60

See In re Saba Enterprises, 421 B.R. 626, 648-52 (Bankr. S.D.N.Y. 2009).

61

Continental Bankers Life Ins. Co. of the South v. Bank of Alamo, 578 S.W.2d 625 (Tenn. 1979). In this case, a

borrower’s corporate subsidiary deposited $50,000 at the defendant bank, which claimed that this deposit was

intended as security for a $100,000 loan to the borrower. When the borrower defaulted on the loan, the bank refused

to allow the subsidiary to recover its deposit, and sought to pierce the corporate veil that separated the subsidiary’s

separate legal existence from that of its borrower. The court declined to pierce the corporate veil, and instead

honored the separate legal existence of the subsidiary corporation because it evinced a “mind of its own” in the

transaction and the parent company’s control was not exercised to “commit fraud, misrepresentation, or a dishonest

or unjust act on the bank.”

62

Id. at 632.

63

Gordon v. Greenview Hospital, 300 S.W.3d 635, 653 (Tenn. 2009).

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 21 -

veil of a corporate parent, it would still have to prevail on a reverse-piercing argument to recover

against other related entities.

Thus, while Tennessee law probably permits reverse piercing in the parent/subsidiary

context,

64

the plaintiff would still have to satisfy the Continental Bankers second prong. A

plaintiff might try to show that a parent corporation maliciously isolated a healthcare facility

operator to avoid liability, but this would be difficult to prove when the structure had been

created for an entirely different reason – namely, to qualify for FHA insured financing.

(ii) Illinois

. Illinois courts considering piercing the corporate

veil often cite Ted Harrison Oil Co. v. Dokka,

65

which lists two mandatory conditions: “for a

court to pierce the corporate veil (1) there must be such unity of interest and ownership that the

separate personalities of the corporation and the individual no longer exist; and (2) circumstances

must exist such that adherence to the fiction of a separate corporate existence would sanction a

fraud, promote injustice, or promote inequitable consequences.”

66

While the second Illinois

prong leaves room for veil-piercing based on mere control, precedent generally involves fraud or

similar wrongdoing, and Illinois has not adopted a single business enterprise theory. Courts

typically require evidence that the corporation is acting only as a “mere façade” for the

shareholders.

67

While the Tennessee rule focuses on how a corporation uses an entity under its

control, the Illinois test focuses instead on the effect of judicially recognizing “separate corporate

existence.” This distinction bears significance in theory—it might allow veil-piercing without a

finding of purposeful fraud or abuse, but successful veil-piercing attempts in Illinois still involve

purposeful wrongdoing.

68

A legitimate business purpose defense would contravene the factors

of either test that turn on a determination that the corporation is a “mere façade” for the

shareholders.

69

Thus, like Tennessee, it would appear unlikely that a plaintiff could successfully

pierce the corporate veil in the master lease situation.

(iii) Indiana. Indiana maintains a traditional veil-piercing test,

and several of its appellate courts have also endorsed a more distinctive single business

enterprise theory. The traditional test held by the Indiana Supreme Court in Aronson

70

states that

“the burden is on the party seeking to pierce the corporate veil to prove that the corporate form

was so ignored, controlled or manipulated that it was the mere instrumentality of another and that

the misuse of the corporate form would constitute a fraud or promote injustice.”

71

The court

64

Nadler v. Mountain Valley Chapel Business Trust, 2004 WL 1488544 (Tenn. Ct. App., 2004).

65

Ted Harrison Oil Co., Inc. v. Dokka, 617 N.E.2d 898 (Ill. Ct. App. 1993)

66

Id. at 901 (citing People ex rel. Scott v. Pintozzi, 277 N.E.2d 844, 851-52 (Ill. 1971).

67

Ted Harrison, 617 N.E.2d at 902; Fontana v. TLD Builders, Inc., 840 N.E.2d 767, 778.

68

See, Fontana, 840 N.E.2d at 781-82 (finding that the second mandatory prong was satisfied when defendant

corporation rapidly sold off assets to frustrate creditors).

69

Ted Harrison, 617 N.E.2d at 902; Fontana, 840 N.E.2d at 767, 778.

70

Aronson v. Price, 644 N.E.2d 864 (Ind. 1994).

71

Id. at 867.

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 22 -

provided a set of factors (sometimes known as the Aronson factors) relevant to both the

instrumentality and fraud prongs: (1) undercapitalization; (2) absence of corporate records; (3)

fraudulent misrepresentation by corporation shareholders or directors; (4) use of the corporation

to promote fraud, injustice or illegal activities; (5) payment by the corporation of individual

obligations; (6) commingling of assets and affairs; (7) failure to observe required corporate

formalities; or (8) other shareholder acts or conduct ignoring, controlling or manipulating the

corporate form.

72

Indiana courts have applied this test strictly against parties attempting to pierce the

corporate veil. In one case

73

the court reaffirmed the traditional test with a sharp analytical

distinction. The corporate veil could not be pierced merely to “promote substantial justice,” the

court clarified: instead, courts could only disregard the corporate form when it had been

“misuse[d] . . . to promote injustice.”

74

Thus Indiana’s traditional veil-piercing test tends to

mirror Tennessee’s standard: abuse of the corporate form will allow veil-piercing, but incidental

injustice will not. However, in some situations, plaintiffs can circumvent Indiana’s burdensome

traditional rule under a single business enterprise doctrine. In one such case,

75

the court allowed

veil-piercing even though the original plaintiff “failed to present much evidence relevant to the

Aronson factors.” When the veil-piercing inquiry concerns two “affiliated corporations” rather

than a corporation and its stockholders, the court held that one entity can be liable for the

obligations of the other if the two are “effectively one and the same corporation.”

76

Four

different factors were used: (1) whether similar corporate names were used, (2) whether there

were common officers and employees, (3) whether the corporations were operated for similar

business purposes, and (4) whether the corporations shared offices, telephone numbers and

business cards.

77

Alternatively, the court could disregard the corporate form when one

corporation conducted an operation “for the benefit of the whole enterprise.”

78

In applying this theory to the master lease structure, there tends to be more risk under

Indiana’s single business enterprise theory than from the traditional rule. The theory focuses on

three elements: (1) the actual identity of corporations, as indicated by common ownership,

directors and employees; (2) the existence of a joint enterprise, indicated by similar business

purposes and by coordinated, rather than purely self-interested, action by different entities; and

(3) presentation to the public, indicated by similar names and shared offices, telephone numbers

or business cards.

79

Cross-collateralization could increase the probability that courts perceive a

joint enterprise; the operators and owners under the master lease structure already share a

72

Id.

73

Escobedo v. BHM Health Associates, Inc., 818 N.E.2d 930 (Ind. 2004).

74

Id. at 935.

75

Smith v. McLeod Distributing, 744 N.E.2d 459, 463 (Ind. Ct. App. 2000).

76

Id. at 463-64.

77

Id. at 463.

78

Id.

79

See Oliver v. Pinnacle Homes, Inc., 769 N.E.2d 1188, 1192-93 (Ind. Ct. App. 2002).

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 23 -

business purpose; and Indiana courts have found single enterprises where “one corporation paid

for the obligations of the other.”

80

No court has recognized a legitimate business purposes

defense to single business enterprise piercing, although how courts would apply these doctrines

to a master lease situation is yet to be determined.

(iv) Delaware. Finally, since so many corporations are

domiciled in the State of Delaware, it would be remiss to not examine the laws of that state.

Delaware’s more established test requires fraud or wrongdoing in order to allow piercing, but a

more recent line of cases disregards this requirement. The Delaware Supreme Court issued its

seminal veil-piercing decision in 1968

81

and held that veil-piercing “may be done only in the

interest of justice, when such matters as fraud, contravention of law or contract, public wrong, or

where equitable consideration among members of the corporation require it, are involved [sic].”

Thus, even if the court assumed that a parent “wholly dominated and controlled” its subsidiary, it

could only disregard the corporate form with an additional element of fraud or injustice.

82

Cases

following this newer test require that the “corporate form cause fraud or similar injustice” before

authorizing piercing of the corporate veil.

83

A second line of cases more amenable to veil-piercing has also emerged. For example

the chancery court has indicated it would allow veil-piercing if a parent and subsidiary were

“operated as a single economic entity such that it would be inequitable . . . to uphold a legal

distinction between them.”

84

That court found that the plaintiff had raised genuine issues of

material fact on its veil-piercing claim and highlighted three relevant factors: (1) that the

defendant subsidiary had loaned its parent company money without apparent consideration; (2)

that the parent company and subsidiary maintained substantially identical boards of directors;

and (3) that officers of the parent were paid from the subsidiary’s payroll account.

85

A later

decision similarly states that “a court can pierce the corporate veil of an entity where there is

fraud or where a subsidiary is in fact a mere instrumentality or alter ego of its owner.”

86

Even when Delaware courts require no fraud or wrongdoing, they will likely accept a

legitimate business purpose defense. In Mabon, the court suggested that corporations could

avoid veil-piercing if they presented “sound business reasons” for activities that appeared to

manipulate the corporate form

87

and in Pauley, the Delaware Supreme Court refused to pierce

80

Id. at 1193.

81

Pauley Petroleum, Inc. v. Continental Oil Co., 239 A.2d 629, 633 (Del. 1968).

82

Id. at 632.

83

Wallace ex rel. Cencom Cable Income Partners II, Inc., L.P. v. Wood, 752 A.2d 1175, 1183-84 (Del. Ch. 1999);

see also Mobil Oil Corp. v. Linear Films, 718 F. Supp. 260, 268 (D. Del. 1989) (stating that to pierce the corporate

veil, “[f]raud or something like it is required.”).

84

Mabon, Nugent & Co. v. Texas American Energy Corp., 1990 WL 44267 (Del. Ct., 1990).

85

Id.

86

Geyer v. Ingersoll Publications Co., 621 A.2d 784, 793 (Del. Ch. 1992).

87

Mabon, 1990 WL 44267 at 5.

7/2392190.7

990007-000001

- 24 -

the corporate veil and found that the “separate existence” of parent and subsidiary “serve[d] a

most legitimate business purpose.”

88

Because groups of facilities should be able to demonstrate

that their structures are fragmented, at least to some extent, in order to become eligible for HUD-

backed mortgages, they should have a very convincing and viable defense under either line of

Delaware cases.

(c) Conclusions. As this discussion demonstrates, any potential

defense to veil-piercing claims should be considered under the laws of the applicable

jurisdiction. The purpose behind the master lease structure is a legitimate business purpose,

created to address particular requirements for access to financing. To the extent that HUD

requires borrowers to adopt fragmented corporate structures as a condition to being eligible for

mortgage insurance, this fragmentation clearly serves a legitimate business purpose. Companies

that qualify for FHA-insured loans benefit from lower interest rates, and can dedicate their