HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C – Management of Health Care Workers Potentially

Exposed

Summary

The purpose of this Policy Directive is to assist health services to appropriately assess and

manage a health care worker following an occupational exposure in order to prevent

disease transmission.

Document type

Policy Directive

Document number

PD2017_010

Publication date

04 May 2017

Author branch

Health Protection NSW

Branch contact

(02) 9391 9192

Replaces

PD2017_009

Review date

04 May 2022

Policy manual

Not applicable

File number

16/2631

Status

Active

Functional group

Clinical/Patient Services - Incident Management, Infectious Diseases

Personnel/Workforce - Occupational Health and Safety

Population Health - Communicable Diseases, Infection Control

Applies to

Affiliated Health Organisations, Board Governed Statutory Health Corporations, Chief

Executive Governed Statutory Health Corporations, Community Health Centres, Dental

Schools and Clinics, Environmental Health Officers of Local Councils, Government Medical

Officers, Local Health Districts, Ministry of Health, NSW Ambulance Service, NSW Health

Pathology, Private Hospitals and day Procedure Centres, Public Health System Support

Division, Public Health Units, Public Hospitals, Specialty Network Governed Statutory

Health Corporations

Distributed to

Divisions of General Practice, Environmental Health Officers of Local Councils,

Government Medical Officers, Ministry of Health, NSW Ambulance Service, Private

Hospitals and Day Procedure Centres, Public Health System, Tertiary Education Institutes

Audience

All clinical staff

Policy Directive

Secretary, NSW Health

This Policy Directive may be varied, withdrawn or replaced at any time. Compliance with this directive is mandatory

for NSW Health and is a condition of subsidy for public health organisations.

POLICY STATEMENT

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 1 of 2

HIV, HEPATITIS B AND HEPATITIS C – MANAGEMENT OF HEALTH

CARE WORKERS POTENTIALLY EXPOSED

PURPOSE

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B and hepatitis C may be transmitted

by significant percutaneous or mucosal exposure to infective blood or other infective

body substances. Occupational exposure is defined as an incident that occurs during

the course of a person’s employment and involves direct contact with blood or other

body substances. Such exposures may put the person at risk of acquiring a blood

borne virus infection. The purpose of this Policy Directive is to assist Health Services

to appropriately assess and manage a health care worker following an occupational

exposure in order to prevent disease transmission.

MANDATORY REQUIREMENTS

All health facilities within the NSW public health system are required to implement

this Policy Directive. It is also recommended that licensed private health care

facilities have regard to this Policy Directive.

Facilities must ensure that:

An efficient local system is established for reporting and managing potential

exposures of HCWs (including non-LHD, non-hospital based health staff or

volunteers) to blood borne viruses

HCWs (including non-LHD, non-hospital based health staff or volunteers) and

source patients have access to blood borne virus testing, as appropriate,

following an occupational exposure

Confidentiality is maintained for all testing and reporting relating to

occupational exposures

All staff are aware of whom to contact for advice regarding occupational

exposures

Expert advice is available to all HCWs (including non-LHD, non-hospital

based health staff or volunteers) 24 hours a day following a potential BBV

occupational exposure to enable rapid assessment and, if needed, timely

administration of prophylaxis

All occupational exposures are reported to SafeWork NSW as required under

the Work Health and Safety Act (s35 and 36) and Work Health and Safety

Regulation (cl699) (Refer to SafeWork NSW Factsheet

http://www.safework.nsw.gov.au/media/publications/health-and-safety/when-

to-notify-blood,-body-fluid-and-needlestick-exposure-incidents)

HCWs are able to obtain the support to which they are entitled, including

access to an Employee Assistance Program or workers compensation if

appropriate as documented in NSW Policy Directive Employee Assistance

Program (PD2016_045)

POLICY STATEMENT

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 2 of 2

The local Public Health Unit is notified in the rare event that hepatitis B or

hepatitis C is transmitted from a patient to a health care worker.

Health care workers must ensure that:

All exposures to blood and body substances are reported as per local

protocols.

IMPLEMENTATION

Sections 2 to 5 describe the procedures to be followed by health care workers and

health facilities in the event that a health care worker is potentially exposed to a

blood borne virus following an occupational exposure.

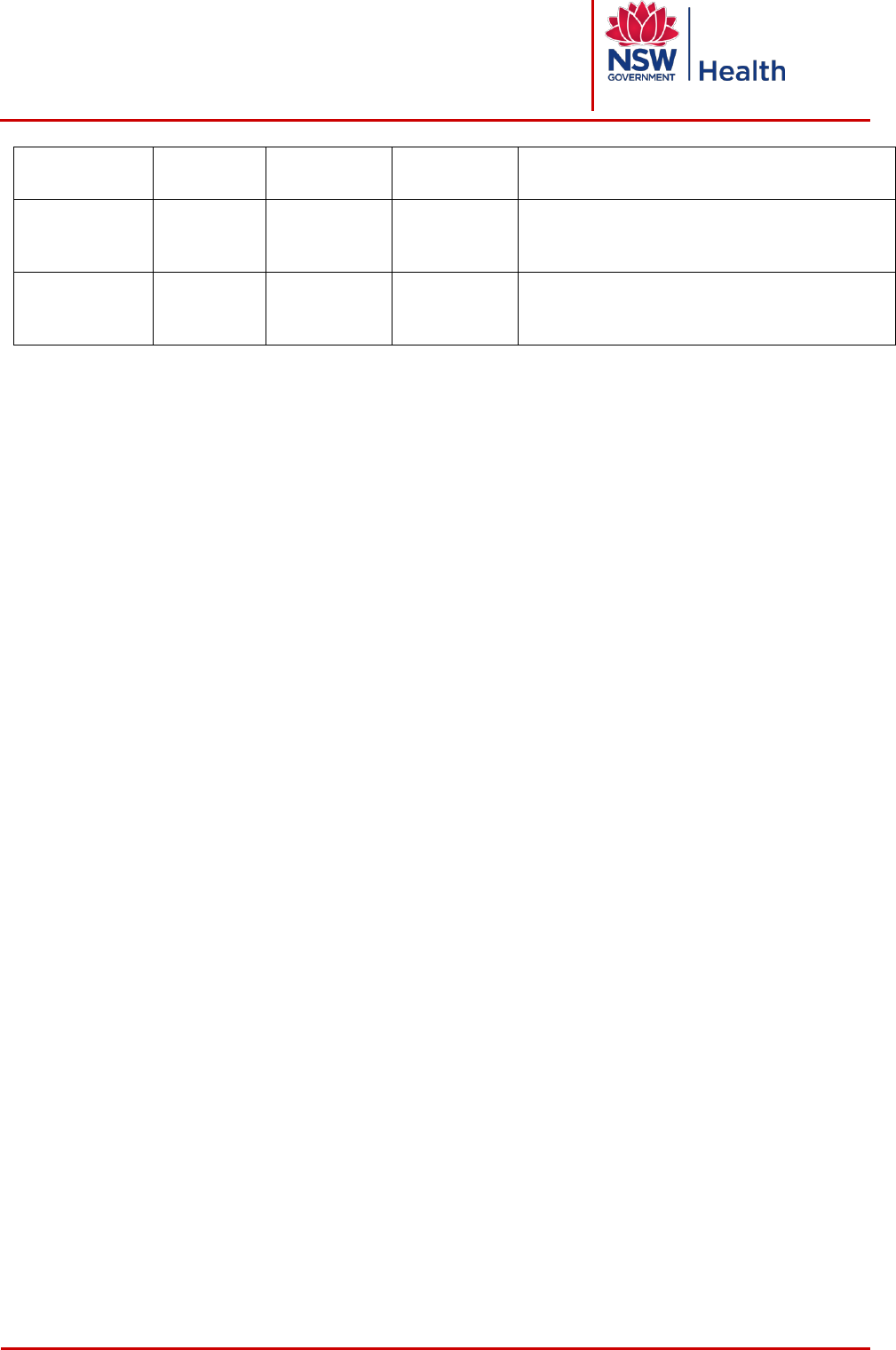

REVISION HISTORY

Version

Approved by

Amendment notes

May 2017

(PD2017_010)

Deputy Secretary,

Population and

Public Health

Formatting changes.

April 2017

(PD2017_009)

Deputy Secretary,

Population and

Public Health

HIV testing and post exposure prophylaxis

recommendations have been updated. A requirement

for health facilities to notify their local public health

unit in the rare event of blood borne virus

transmission to a health care worker has been

added. Evidence relating to occupational

transmission of BBV has been updated.

January 2005

(PD2005_311)

Director-General

Minor amendments.

June 2003

Circular 2003/839

Ministerial Advisory

Committee on

AIDS Strategy

Updates regarding to use of newer antiretroviral

therapies.

1998

Circular 1998/11

Ministerial Advisory

Committee on

AIDS Strategy

New circular.

ATTACHMENTS

1. HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C – Management of Health Care Workers

Potentially Exposed: Procedures.

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Contents page

HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C – Management of

Health Care Workers Potentially Exposed

PROCEDURES

Issue date: May-2017

PD2017_010

HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C – Management of

Health Care Workers Potentially Exposed

PROCEDURES

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Contents page

CONTENTS

1 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................ 1

1.1 About this document ......................................................................................................... 1

1.2 Key abbreviations and definitions ..................................................................................... 1

1.3 Legal and legislative framework ....................................................................................... 2

2 IMMEDIATE CARE OF THE EXPOSED HEALTH CARE WORKER .................................... 2

3 RISK ASSESSMENT OF THE EXPOSURE ............................................................................ 2

4 MANAGEMENT OF EXPOSURES WITH NO RISK OF BLOOD BORNE VIRUS

TRANSMISSION ...................................................................................................................... 4

5 MANAGEMENT OF EXPOSURES WITH POTENTIAL FOR BLOOD BORNE VIRUS

TRANSMISSION ...................................................................................................................... 4

5.1 Post exposure prophylaxis ............................................................................................... 4

5.2 Risk assessment of the source patient ............................................................................ 5

5.2.1 Source negative for HIV, HBV and HCV .............................................................. 6

5.2.2 Source with unknown infectious status and source unable to be tested ............. 6

5.2.3 Source positive or potentially positive for HIV ...................................................... 7

5.2.4 Source positive or potentially positive for HBV .................................................. 10

5.2.5 Source positive or potentially positive for HCV .................................................. 11

5.3 Testing of the exposed HCW .......................................................................................... 13

5.4 Special situation: when a patient is exposed to the blood or body fluids of a HCW ..... 13

6 REFERENCES ........................................................................................................................ 15

APPENDIX A: MANAGEMENT OF THE EXPOSED HCW FOLLOWING AN

OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURE .............................................................................................. 18

APPENDIX B: RECOMMENDED LABORATORY TESTING FOR THE EXPOSED HCW .. 19

APPENDIX C: HIV PEP RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................... 20

APPENDIX D HEPATITIS B PEP RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................... 21

HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C – Management of

Health Care Workers Potentially Exposed

PROCEDURES

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 1 of 21

1 BACKGROUND

1.1 About this document

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B and hepatitis C may be transmitted by

significant percutaneous or mucosal exposure to infective blood or other infective body

substances. Occupational exposure is defined as an incident that occurs during the

course of a person’s employment and involves direct contact with blood or other body

substances. Such exposures may put the person at risk of acquiring a blood borne virus

infection.

Adherence to infection prevention and control practices as outlined in the current version

of the NSW Infection Control Policy remains the first line of protection for health care

workers (HCWs) against occupational exposure to HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C. The

policy and guidelines for the NSW Health Service on prevention of sharps injuries are

documented in the NSW Policy Directive Sharps Injuries – Prevention in the NSW Public

Health System (PD2007_052). The current version of the NSW Policy Directive

Occupational Assessment, Screening and Vaccination Against Specified Infectious

Diseases mandates that health staff directly involved in patient care and/or the handling

of human tissue, blood or body fluids complete the full course of hepatitis B vaccination

and provide their post vaccination serology result.

This policy directive outlines the procedures that should be followed in the event of an

occupational exposure including:

The immediate care to be taken by the exposed HCW

An assessment of the risk of blood borne virus transmission

Management of the exposed HCW including blood borne virus testing and post

exposure prophylaxis.

1.2 Key abbreviations and definitions

Appropriately skilled officer – means a medical practitioner or nurse with expertise in

the assessment of the risk of blood borne virus transmission and the management of the

exposed HCW following an occupational exposure

anti-HBs – antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen

BBV – blood borne virus. Refers to HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses.

HBV – hepatitis B virus

HBIG – hepatitis B immunoglobulin

HBsAg – hepatitis B surface antigen

HCW – health care worker. Refers to all persons working in healthcare settings who have

the potential for exposure to infectious/potentially infectious body fluids. This also

includes non-LHD, non-hospital based health staff and volunteers.

HCV – hepatitis C virus

HIV – human immunodeficiency virus

HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C – Management of

Health Care Workers Potentially Exposed

PROCEDURES

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 2 of 21

PCR – polymerase chain reaction

PEP – post exposure prophylaxis

Source - person from whom blood or body fluids originated

Window period – refers to the time after a person has been exposed and is the

maximum time it takes for a test to give an accurate result

1.3 Legal and legislative framework

Health Services have obligations under the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (NSW) and

the Public Health Act 2010 (NSW) and their associated regulations.

2 IMMEDIATE CARE OF THE EXPOSED HEALTH CARE WORKER

After exposure to blood or other body substances the exposed HCW should as soon as

possible do the following:

Wash the exposure site with soap and water

Undertake appropriate care of any wound(s)

If eyes are contaminated then rinse them, while they are open, gently but

thoroughly with water or normal saline

If blood or other body substances get in the mouth, spit them out and rinse the

mouth with water several times

If clothing is contaminated remove clothing and shower if necessary

Inform their line manager so they can immediately be relieved from duty and notify

the appropriately skilled officer who is designated to conduct an urgent risk

assessment on potentially exposed staff (as per local reporting procedures) to

ensure that necessary further action is undertaken.

Sections 2 to 5 outline the procedures to be followed by health care workers and health

facilities following an occupational exposure. Refer to Appendix A for a summary of these

procedures and Appendix B for a summary of recommended laboratory testing.

3 RISK ASSESSMENT OF THE EXPOSURE

In the event of an occupational exposure, appropriately skilled officer/s should conduct a

risk assessment immediately. The first step in the risk assessment is to establish the type

of injury (see Table 1). Following this, consideration should be given to the body fluid

involved (see Table 2).

HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C – Management of

Health Care Workers Potentially Exposed

PROCEDURES

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 3 of 21

Table 1: Risk of transmission of blood borne viruses from an infectious bodily fluid, by

injury type (based on UK guidelines

1

)

Level of risk

Injury type

Higher risk injury

Deep percutaneous injury

Visible blood on sharps

Needle used on source’s blood vessels

Lower risk injury

Superficial injury, exposure through broken

skin, mucosal exposure (usually splashes

to eye or mouth)

Old discarded sharps

No visible blood on sharps

Needle not used on blood vessels e.g.

suturing, subcutaneous injection needles

Injury with no risk

Skin not breached

Contact of body fluid with intact skin

Needle (or other sharp object) not used on

a patient before injury

Table 2: Body fluids and risk for blood borne virus transmission (based on UK

guidelines

1

)

Level of risk

Body fluid

Infectious (good evidence of BBV

transmission following occupational

exposure)

Blood

Visibly bloody body fluids

Potentially infectious (risk of BBV

transmission following occupational

exposure unknown)

(In alphabetical order):

Amniotic fluid

Cerebrospinal fluid

Human breast milk

Pericardial fluid

Peritoneal fluid

Pleural fluid

Saliva in association with dentistry (likely to

be contaminated with blood even when not

visibly so)

Semen

Synovial fluid

Tissue fluid from burns or skin lesions

Vaginal secretions

Not infectious (unless visibly blood

stained)

Nasal secretions

Saliva (non-dentistry associated)

Sputum

Stool

Sweat

Tears

HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C – Management of

Health Care Workers Potentially Exposed

PROCEDURES

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 4 of 21

Urine

Vomit

Where the exposed HCW is uncertain about actions to be taken, the Blood and Body

Fluid Exposure Phoneline (formerly the NSW Needlestick Hotline) may assist. The Blood

and Body Fluid Exposure Phoneline is an information, support and referral service for

NSW based health care workers who sustain needlestick injuries and other blood/body

fluid exposures during the course of their work. The line is answered by an on-call nurse

7 days a week from 7am to 11pm and can be contacted on free call 1800 804 823 within

NSW. The Exposure Phoneline is not a reporting or surveillance service.

4 MANAGEMENT OF EXPOSURES WITH NO RISK OF BLOOD

BORNE VIRUS TRANSMISSION

Occupational exposures are not considered to have the potential for blood borne virus

transmission if either the injury is classified as no risk (Table 1) or the body fluid is not

infectious (Table 2). For such exposures, no further action with respect to the health

worker is required other than an opportunistic assessment of his/her protection against

hepatitis B in accordance with the current NSW Policy Directive Occupational

assessment, screening and vaccination against specified infectious diseases. Post

exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is not indicated and testing of the source patient is not

required. Such workers should be advised that the potential side effects and toxicity of

taking HIV PEP outweigh the negligible risk of transmission posed by this exposure

regardless of the HIV status of the source patient. No HCV or HIV testing of the exposed

HCW is required.

A risk assessment of the incident should be conducted and local documentation

procedures should be followed after each potential exposure.

5 MANAGEMENT OF EXPOSURES WITH POTENTIAL FOR BLOOD

BORNE VIRUS TRANSMISSION

An occupational exposure has the potential for blood borne virus (BBV) transmission if

the injury carries a risk (see table 1) and the body fluid is infectious/potentially infectious

(see table 2). Following all such exposures a risk assessment of the incident should be

conducted.

5.1 Post exposure prophylaxis

Post exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is available following exposure to HIV and hepatitis B. It

is recommended for all higher risk injuries involving an infectious/potentially infectious

body fluid. It should be considered for lower risk injuries involving an infectious/potentially

infectious body fluid (see Tables 1 and 2).

Greater efficacy is achieved the earlier prophylaxis is administered (ideally within 1-2

hours of exposure). The initiation of PEP should not be delayed while awaiting laboratory

testing of either the source patient or the health care worker. The continuation of PEP

should be reconsidered once laboratory results become available. Further information on

HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C – Management of

Health Care Workers Potentially Exposed

PROCEDURES

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 5 of 21

PEP is found in section 5.2.3 (for HIV) and 5.2.4 (for HBV). Prophylaxis can be

commenced up to 72 hours post exposure.

5.2 Risk assessment of the source patient

Following occupational exposures that carry a risk of BBV transmission, officer/s

conducting the risk assessment should seek information on the BBV status of the source

patient as soon as is practicable.

If the blood borne virus status of the source patient at the time of the incident is unknown,

the staff conducting the risk assessment should arrange for the source patient to be

tested as soon as practicable for HIV, HBV and HCV infection (refer to Table 3). Results

of source testing will better inform the exposed HCW about the risk of transmission and

where PEP has been initiated, inform the need for continuation. Informed consent for

testing must be obtained from the source patient. The exposed HCW should not

approach the source patient for consent. If the patient does not provide consent, testing

cannot occur. Consent should also be sought for the results of testing to be provided to

the exposed HCW.

Occupational exposures occurring during autopsies should be managed as set out in

section 5.2.2.

Note that testing of the source patient for HBV infection is not required if the exposed

HCW has previous documented evidence of immunity to hepatitis B (anti-HBs level ≥10

mIU/mL at any time or HBcAb positive). Viral load should be measured for source

patients who are known, or discovered, to be infected with HIV, HCV or HBV. The

source should be offered immediate referral to a specialist service if a previously

undiagnosed blood borne virus is detected.

Table 3: Recommended testing of source patient

#

Combined HIV antigen and antibody immunoassay (fourth generation HIV test)

Hepatitis B surface antigen (not required if HCW has hepatitis B immunity)

Hepatitis C antibody*

#

Viral load should be measured for source patients who are known, or discovered, to be infected with

HIV, HCV or HBV

*Consider qualitative hepatitis C RNA testing if individual is at risk of hepatitis C infection as may be

antibody negative in acute infection and remain negative for up to 12 months if immunocompromised.

Source potentially in the window period

If the source patient tests negative for BBV infection but reports a recent (within previous

three months for HIV or six months for HBV and HCV) risk behaviour that places them at

high risk for infection, he/she should be advised to seek medical attention if they develop

signs and/or symptoms of primary infection. For their own health benefit, they should also

be advised to undergo testing for that BBV six weeks and 12 weeks after the exposure. If

the source is at risk of a recent hepatitis B or C infection final tests should be done at 24

weeks after exposure.

Follow up and documentation of source testing is not required by staff managing the

occupational exposure as it will not influence the care of the exposed HCW (due to timing

HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C – Management of

Health Care Workers Potentially Exposed

PROCEDURES

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 6 of 21

of results). Until such time as infection can be excluded in the source, the exposed HCW

should be managed as for exposure to a positive source.

The risk assessment of the source patient is outlined in Table 4.

Table 4: Risk assessment of source patient (based on UK guidelines

1

)

Level of risk

Source

Higher risk source

Known to be infected with one or more blood borne viruses

(viral load and treatment status unknown)

Known to have a detectable viral load for one or more blood

viruses

Unknown viral load but known to have advanced or untreated

blood borne infection

Blood borne virus status unknown and known risk factors*

Lower risk source

Infected with a blood borne virus but known to have a fully

supressed viral load

Unknown viral load but receiving long term antiviral treatment

for blood borne virus with good adherence and known to be

stable

Blood tests at/near to the time of the incident were negative for

all three blood borne viruses but source reports ongoing risk

factors for blood borne viruses

Blood borne virus status unknown but had no known risk

factors for such viruses

Source with minimal or

no risk

Recent blood test that was negative for all three blood borne

viruses and no recent risk behaviours reported

* Example of risk factor may include intravenous drug use, men who have sex with men, origin or unprotected

sexual intercourse with a sexual partner from high prevalence area

1

for either HIV infection, or hepatitis B or

hepatitis C.

5.2.1 Source negative for HIV, HBV and HCV

In the event that the source undergoes testing and is found to be negative for HIV, HBV

and HCV and does not report recent behaviour that may place them at risk of a blood

borne virus then no further action is required. PEP, if commenced, should be

discontinued. If there is reason to suspect the self-reported risk history of the source may

unreliable or incomplete, the exposed HCW should be managed as per exposure to a

positive source (refer to sections 5.2.3 to 5.2.5).

5.2.2 Source with unknown infectious status and source unable to be tested

If the status of the source is not known then the risk of the source being positive for HIV,

HBV and HCV must be assessed from the available information relating to risk factors

1

Countries with population prevalence over 1% are considered to have a high prevalence of HIV. High

prevalence areas include the Caribbean, Sub-Saharan Africa, South East Asia and Papua New Guinea.

For the HIV seroprevalence for individual countries go to http://aidsinfo.unaids.org/. Areas reporting high

hepatitis C prevalence are sub-saharan Africa, North Africa and the Middle East, central, south and east

Asia and Eastern Europe. Areas of high hepatitis B endemicity include most of East and Southeast Asia

(except Japan), Pacific island groups, parts of central Asia and the Middle East, the Amazon Basin, and

sub-Saharan Africa. Refer to the Travelers’ Health section of the Centers of Disease Control and

Prevention website for further detail.

HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C – Management of

Health Care Workers Potentially Exposed

PROCEDURES

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 7 of 21

known to be associated with BBVs (e.g. intravenous drug use, male homosexual sex and

origin or sexual partner from a high prevalence area). If there is a risk of the source being

infected with HIV, HBV or HCV then the exposed HCW should be managed as per

exposure to a positive source (refer to sections 5.2.3 to 5.2.5).

5.2.3 Source positive or potentially positive for HIV

Risk of HIV transmission from positive source patient

The overall risk of acquiring HIV infection following occupational exposure to HIV is low.

The average risk of HIV transmission (without prophylaxis) after a percutaneous

exposure to HIV infected blood has been estimated to be 0.3% (95% confidence interval

(CI): 0.2-0.5%).

2

The risk of seroconversion following mucous membrane exposure is

estimated to be 0.09% (95 % CI: 0.006%-0.5%) and the risk following non-intact skin

exposure is estimated to be even lower.

2

A case control study conducted by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

showed that significant risk factors for HIV infection were deep injury (odds ratio (OR) =

15, 95% CI: 6.0-41), injury with a device that was visibly contaminated with the source

patient's blood (OR= 6.2, 95% CI: 2.2-21), a procedure involving a needle placed in the

source patient's artery or vein (OR =4.3, 95% CI 1.7-12), and exposure to a source

patient who died of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome within two months

afterward (OR=5.6; 95 %CI: 2.0-16)

3

.

There have been no confirmed cases of HIV infection in a HCW following an

occupational exposure in NSW since 1994 and nationally since 2002. Only one

confirmed case of occupational HIV acquisition (involving a laboratory technician working

with a live HIV culture) has been reported in the US since 1999

4

. There has only been

one other case report of occupational HIV transmission in the developed world published

since 2005. In this instance, a nurse acquired HIV following a needle stick injury from a

patient (not previously known to have HIV) with a high viral load

5

. Due to delayed

reporting of the incident, PEP was not given. Table 5 shows a summary of the

occupational exposure registry reviews published in the international literature since

2005.

Table 5: Evidence of HIV transmission following occupational exposure

Country

Time

period

No. of HCW

exposures

to HIV

No. HIV

sero-

conversions

(rate)

Notes

Australia

6

2000-2003

13

0 (0%)

Includes percutaneous and mucous

membrane exposures. All given PEP

Brazil

7

1997-2009

80

0 (0%)

Includes only percutaneous injuries. No

information provided on PEP

Denmark

8

1999–2012

276

0 (0%)

Includes percutaneous and mucous

membrane exposures. All given PEP

Germany

9

2010-2012

51

0 (0%)

Includes only percutaneous injuries. PEP (3

drugs, mean time to start 75 mins >

exposure) given to 35/51 and for other 16

cases the source patient was known to have

a viral load <20 copies/mL at time of incident.

HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C – Management of

Health Care Workers Potentially Exposed

PROCEDURES

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 8 of 21

Netherlands

10

2003-2010

60

0 (0%)

Includes only percutaneous injuries. No

information provided on PEP

Thailand

11

1996–2014

84

0 (0%)

Includes percutaneous, mucous membrane

and non-intact skin exposures. All offered

PEP, completed in 62/84 instances.

United

Kingdom

12

2004-2013

1478

0 (0%)

Includes percutaneous, mucous membrane

and non-intact skin exposures. 1135 (77%)

given PEP.

Post exposure prophylaxis (PEP)

Based on evidence from animal models and what is known about primary HIV infection,

there is a window of opportunity following exposure to HIV, during which antiviral

medication may prevent infection. However, the evidence for efficacy of PEP in

preventing HIV acquisition is limited

13,14

. A small US case-control study of HIV

seroconversion in HCWs after percutaneous exposure published in 1997 provided the

first evidence in humans that PEP seemed to be protective against infection

3

. This study

found that zidovudine PEP was associated with an 81% reduction in the odds of infection

after adjustment for relevant exposure risk factors. There have been 24 reports of PEP

failure following occupational needle stick exposures in the literature

15

. In over three

quarters of these instances, zidovudine only was used; only six instances of PEP failure

in the context of occupational needle stick injury have been reported with multi-drug

regimens with three of these occurring after 1999. Factors that may have contributed to

the failure of the combination drug PEP include drug resistance (in 3 cases the HCW was

found to be infected with a strain resistant to the PEP regimen), exposure to a high HIV

viral load and delayed initiation of PEP.

16,17,18,19

Multi-drug regimens are now prescribed to prevent HIV infection following exposure.

However, there is no definitive evidence to support a two versus a three-drug regimen.

Instead, the additional benefit of a third drug must be weighed against the cost and

potential harms.

While newer HIV antiretrovirals are less toxic and better tolerated than the older HIV

drugs, adverse effects still occur. In addition, serious drug interactions can occur when

antiretroviral agents are used with certain other drugs. More commonly reported side

effects include nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and fatigue. Rare, but important side effects

of tenofovir include acute renal failure and proximal renal tubolopathy (Fanconi’s

syndrome). There is a small risk of rhabdomyolysis with raltegravir.

The need for HIV PEP depends on an assessment of the risk of transmission and

consideration of the potential adverse effects. Where possible, information concerning

the source’s stage of HIV infection, viral load, resistance testing and history of therapy

and medication adherence should be ascertained so that the most appropriate therapy

and counselling can be offered. While the evidence supports a significantly lower risk of

HIV transmission following sexual exposure to a source with an undetectable viral load,

such evidence does not exist for occupational exposures. While it is assumed there is

also an extremely low risk of HIV transmission, it is still reasonable for a healthcare

worker who has had a higher risk exposure to a source who is HIV positive but with an

undetectable viral load to complete the course of PEP. The recommended PEP regimen

HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C – Management of

Health Care Workers Potentially Exposed

PROCEDURES

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 9 of 21

is outlined in Table 6. Refer to Appendix C for the antiretroviral drug regimens

recommend by the Australasian Society of HIV Medicine.

Table 6: PEP recommendations following occupational exposure to HIV positive source

Injury type

Source viral load known to

be undetectable

Source not on treatment or on

treatment with detectable or

unknown viral load

Needlestick injury or other sharps

exposure

Consider 2 drugs

3 drugs

Mucous membrane or non-intact

skin exposure

Consider 2 drugs

Consider 3 drugs

Any medical officer can prescribe a PEP starter pack (lasting 3 to 7 days). The

recommended course of PEP is 28 days. A prescription for the remainder of the PEP

course must be obtained from a clinician experienced in the administration of drugs for

the treatment of HIV.

Where there is a risk that a woman may be pregnant, undertake a serum beta HCG

urgently. If possible, contact an HIV experienced Infectious Disease or Sexual Health

Physician before starting HIV prophylaxis for a woman who is pregnant or at risk of

pregnancy. Where it is not immediately possible and the risk of contracting HIV appears

to outweigh any potential risk for the pregnancy commence prophylaxis and advise

making an appointment with an HIV experienced physician for the next working day.

Truvada

®

and Combivir

®

are category B3 drugs which means that there is limited data

relating to safety in pregnancy but no human evidence of harm.

Exposed HCW testing recommendations

It is recommended that 4

th

generation HIV antibody/antigen testing be conducted at 6

weeks. A negative test at 6 weeks is likely to exclude infection but the exposed HCW

should be retested at 12 weeks to definitively exclude infection. HIV viral load tests have

the capacity to detect early HIV infection before antibody development and should be

considered following higher risk exposures to a higher risk source. Longer follow up with

additional testing may also be indicated in complex cases (e.g. possibility of coinfection)

as directed by an expert clinician.

Advice for the exposed HCW during follow up period

During the follow up period the exposed HCW should be advised:

Not to donate plasma, blood, body tissue, breast milk or sperm

To protect sexual partners by adopting safe sexual practices (use of condoms)

To seek expert medical advice regarding pregnancy and/or breastfeeding

To seek medical attention about any acute illness (i.e. fever, rash, myalgia,

fatigue, malaise, lymphadenopathy, anorexia).

Modification to work practices (including avoidance of exposure prone procedures) is not

required on the basis of an occupational HIV exposure.

HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C – Management of

Health Care Workers Potentially Exposed

PROCEDURES

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 10 of 21

5.2.4 Source positive or potentially positive for HBV

Susceptibility of the exposed HCW to HBV infection

In accordance with the current NSW Policy Directive Occupational Assessment,

Screening and Vaccination Against Specified Infectious Diseases all staff who have

direct contact with patients, deceased persons, blood, body substances or infectious

material or surfaces/equipment that might contain these must complete a full course of

hepatitis B vaccination and/or provide serological evidence of protection.

If the exposed HCW has a documented protective response (anti-HBs level ≥10 mIU/mL)

at any time following completion of the vaccination course, then he/she is considered

immune to hepatitis B and no further action (i.e. testing of the source patient or post

exposure prophylaxis) is required regardless of the exposure. If the response to previous

vaccination is unknown, the anti-HBs level of the exposed HCW should be determined as

quickly as possible. If immunity status cannot be determined quickly then the HCW

should be managed as a susceptible person until such time that evidence of immunity is

available.

The following provisions relate only to those who are presumed susceptible to HBV

infection (those with anti-HBs level <10 mIU/mL and who are hepatitis core antibody

negative).

Risk of HBV transmission from positive source patient

The probability of infection following exposure to a susceptible person depends on a

number of factors including the volume and infectiousness of the body fluids and the

route of the exposure. Occupational HBV transmission primarily occurs via percutaneous

and mucosal exposure to blood. Of viral parameters, the risk of infection best correlates

with viral load (HBV DNA) rather than hepatitis B serology. The presence of hepatitis B e

antigen (HBeAg) is a surrogate marker for high viral load.

In studies of hepatitis B susceptible HCWs who sustained injuries from needles

contaminated with blood containing HBV, the risk for developing clinical hepatitis if the

blood was both HBsAg-positive and HBeAg-positive was 22%–31%, and the risk for

developing serologic evidence of HBV infection was 37%–62%. By comparison, the risk

for developing clinical hepatitis from a needle contaminated with HBsAg-positive, HBeAg-

negative blood was 1%–6%, and the risk for developing serologic evidence of HBV

infection was 23%-37%.

17

Post exposure prophylaxis (PEP)

Where indicated (see Section 5.1) HBV post exposure prophylaxis with hepatitis B

immunoglobulin and vaccine should be offered to non-immune and non-infected

individuals in accordance with the recommendations in the current edition of the

Australian Immunisation Handbook (refer to Appendix D). Requests for hepatitis B

immunoglobulin should be directed to the local hospital blood bank.

Source testing recommendations

If a source is known or found to be HBsAg positive, then HBeAg and quantitative HBV

DNA testing of the source patient should be performed, with the consent of the source,

so that the exposed HCW can be counselled appropriately about the risk of transmission.

Exposed HCW testing recommendations

HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C – Management of

Health Care Workers Potentially Exposed

PROCEDURES

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 11 of 21

The exposed susceptible HCW should undergo HBsAg testing at 6 weeks, 12 weeks and

24 weeks. In the rare event that an exposed HCW is newly diagnosed with HBV infection,

the local Public Health Unit should be notified. Post-vaccination serological testing is

recommended 4 to 8 weeks after completion of the vaccination course.

Advice for the exposed HCW during follow up period

During the follow up period the exposed HCW should be advised:

Not to donate plasma, blood, body tissue, breast milk or sperm

To seek medical attention if they develop signs and/or symptoms of acute hepatitis

(i.e. anorexia, vague abdominal discomfort, nausea and vomiting, fatigue and/or

jaundice)

The exposed HCW is not required to modify sexual practices provided that HBV PEP has

been administered on time. Ideally the HCW should refrain from becoming pregnant until

completion of the vaccination course. There are no restrictions regarding breastfeeding.

Modifications to work practices (including avoidance of exposure prone procedures) are

not required on the basis of an occupational HBV exposure.

5.2.5 Source positive or potentially positive for HCV

Risk of HCV transmission from positive source patient

Overall, the risk of HCV transmission following an occupational exposure is low. The

probability of infection following exposure depends on a number of factors including the

volume and infectiousness of the body fluids and the route of the exposure. The average

incidence of anti-HCV seroconversion after accidental percutaneous exposure from a

HCV-positive source is estimated at 1.8% (range 0-7%)

20

.

The risk of transmission

increases significantly if the source has a high viral load. A review of the recent published

evidence of HCV transmission following occupational exposures is summarised in Table

7.

A case control study on the risk factors for HCV transmission in HCW based on UK data

collected from 1997 to 2007, found that all HCV seroconversions followed percutaneous

injuries

21

.

As had been previously shown

22

, the depth of injury was significantly

associated with seroconversion and the majority of exposures involved hollow bore

needles from a vein or artery contaminated with blood or blood stained fluid.

Transmission rarely occurs from mucous membrane exposures to infective blood and

there are only two published reports to date of HCV transmission to a HCW via non-intact

skin exposure

23,24

.

Post exposure prophylaxis (PEP)

Currently, there is no vaccination or post exposure prophylaxis that is effective in the

prevention of hepatitis C transmission. However, treatment of acute hepatitis C infection

is now highly effective. Early identification of infection is necessary to enable prompt

referral and treatment.

HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C – Management of

Health Care Workers Potentially Exposed

PROCEDURES

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 12 of 21

Table 7: Evidence of HCV transmission following occupational exposures

Country

Time period

Number of exposures

involving HCW and HCV

positive source

Number of HCV

seroconversions

Rate

Australia

6

2000-2003

64

#

0

0%

Austria

21

1995-2009

150*

0

0%

Brazil

7

1997-2009

38

#

2

5%

Denmark

22

2003-2012

62

0

0%

Germany

9

2010-2012

44*

1

2.3%

Italy

23

2004-2006

26

0

0%

Korea

24

2004 -2008

327

3

0.9%

Netherlands

10

2003-2010

53

1

1.9%

United Kingdom

12

2004-2013

2566

9

0.4%

*All percutaneous injuries with source known to be HCV PCR positive

#

All percutaneous injuries involving large bore catheter needles

Source testing recommendations

If the source is known or found to be HCV antibody positive, then quantitative hepatitis C

RNA testing of the source patient should be performed with the consent of the source, so

that the exposed HCW can be counselled appropriately about the risk of transmission.

Exposed HCW testing recommendations

The exposed HCW should undergo qualitative HCV PCR testing at 6 weeks and HCV

antibody testing at 6 weeks and 12 weeks. If results are negative at that time the HCW

can be advised that the risk of transmission is negligible but an antibody test at 24 weeks

post exposure should still be undertaken to confirm that transmission has not occurred.

Given its low specificity, liver function testing is not recommended. In the rare event that

an exposed HCW is newly diagnosed with HCV infection, the local PHU should be

notified.

Advice for the exposed HCW during follow up period

During the follow up period the exposed HCW should be advised:

not to donate plasma, blood, body tissue or sperm

to seek medical attention if they develop signs and/or symptoms of acute hepatitis

(i.e. anorexia, vague abdominal discomfort, nausea and vomiting, fatigue and/or

jaundice)

The exposed HCW is not required to modify sexual practices. In most circumstances the

HCW should refrain from becoming pregnant until HCV infection is excluded. There are

no restrictions regarding breastfeeding. Modifications to work practices (including

avoidance of exposure prone procedures) are not required on the basis of an

occupational HCV exposure.

HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C – Management of

Health Care Workers Potentially Exposed

PROCEDURES

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 13 of 21

5.3 Testing of the exposed HCW

The exposed HCW should have baseline testing for HIV, HBV and HCV infections as

detailed in Table 8. If the exposed HCW is known to be infected with one or more of

these BBVs, then baseline testing for those BBVs is not required. Note that a HCW with

previous HCV infection who has been successfully treated or who has cleared the virus

spontaneously remains susceptible to HCV re-infection.

Informed consent must be obtained before testing can proceed. The exposed HCW

needs to be informed that baseline testing:

Determines whether they were infected before the exposure and can be done up

to a few days after the exposure (there is no need for after-hours testing)

Does not have to be done at the workplace. The HCW can seek testing at their GP

or other offsite service but the reason for the test (i.e. following occupational

exposure) should be documented.

Although not urgent, is important in case of a worker’s compensation claim in the

rare event of seroconversion

If the HCW is not immune and not previously vaccinated against HBV, or not currently

infected with HBV, then he/she should be vaccinated as outlined in The Australian

Immunisation Handbook and in accordance with the current NSW Policy Directive

Occupational assessment, screening and vaccination against specified infectious

diseases.

The HCW should be offered immediate referral to a specialist service if a previously

undiagnosed blood borne virus is detected. Refer to current version of the NSW Policy

Directive HIV, Hepatitis B or Hepatitis C – Health Care Workers Infected. Immediate

consultation with a HIV specialist is required in the event that the exposed HCW who had

commenced HIV PEP is found to be HIV positive on baseline testing.

All occupational exposure incidents should be documented according to local

procedures.

Table 8: Baseline testing of the HCW

HCW hepatitis B status unknown

HCW previously shown to be hepatitis B

immune

Hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B

surface antibody, hepatitis B core

antibody

Combined HIV antigen and antibody

immunoassay (fourth generation HIV test)

Hepatitis C antibody

Combined HIV antigen and antibody

immunoassay (fourth generation HIV test)

Hepatitis C antibody

5.4 Special situation: when a patient is exposed to the blood or body fluids

of a HCW

In some instances, when a HCW is exposed to potentially infectious fluids from a patient,

there is also exposure of the patient to the HCW’s blood. For example, this might occur if

the HCW experiences a used sharps injury and blood from the sharps injury comes into

contact with the patient’s open wound or mucous membrane. In this situation, in addition

HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C – Management of

Health Care Workers Potentially Exposed

PROCEDURES

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 14 of 21

to the risk of BBV transmission to the HCW, there is also a potential risk of BBV

transmission from the HCW to the patient. In such circumstances, the HCW should be

managed as per Sections 2 to 5 as a potential source for the patient. The patient and

their treating medical team must be informed of the incident as soon as possible after the

exposure. Injuries to patients must be reported in the Incident Information Management

System.

The Australian National Guidelines for the Management of Health Care Workers Known

to be infected with Blood Borne Viruses minimize the risk that a patient will be exposed to

the blood of an infected health care worker. In the event of an occupational exposure

incident involving a HCW known to be infected with a BBV, refer to the NSW Policy

Directive, HIV, Hepatitis B or Hepatitis C – Health Care Workers Infected.

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 15 of 21

6 REFERENCES

1 Riddell A, Kennedy I, Tong CY. Management of sharps injuries in the health care

setting. BMJ. 2015 Jul 29;351:h3733.

2 Kuhar DT, Henderson DK, Struble KA, Heneine W, Thomas V, Cheever LW,

Gomaa A, Panlilio AL; US Public Health Service Working Group.Updated US Public

Health Service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to human

immunodeficiency virus and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis.Infect

Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013 Sep;34(9):875-92.

3 Cardo DM, Culver DH, Ciesielski CA, Srivastava PU, Marcus R, Abiteboul D,

Heptonstall J, Ippolito G, Lot F, McKibben PS, Bell DM; Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention Needlestick Surveillance Group. A case-control study of HIV

seroconversion in health care workers after percutaneous exposure. N Engl J Med.

1997 Nov 20;337(21):1485-90.

4 Joyce M, Kuhar D, Brooks J. Notes from the Field: Occupationally Acquired HIV

Infection among Health Care Workers — United States, 1985–2013 Morbidity and

Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). January 9, 2015 / 63(53): 1245-1246.

5 Gibellini D, Borderi M, Bon I, Biagetti C, De Crignis E, Re MC. HIV-1 infection of a

nurse from a newborn with an unknown HIV infection: a case report. J Clin Virol.

2009 Dec;46(4):374-7.

6 Peng Bi, Tully PJ, Boss K, Hiller JE. Sharps injury and body fluid exposure among

health care workers in an Australian tertiary hospital. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public

Health. 20(2):139-47, 2008.

7 Medeiros WP, Setúbal S, Pinheiro PY, Dalston MO, Bazin AR, de Oliveira SA.

Occupational hepatitis C seroconversions in a Brazilian hospital. Occup Med

(Lond). 2012 Dec;62(8):655-7.

8 Lunding S, Katzenstein TL, Kronborg G, Storgaard M, Pedersen C, Mørn B,

Lindberg JÅ, Kronborg TM, Jensen. The Danish PEP Registry: Experience with the

use of post-exposure prophylaxis following blood exposure to HIV from 1999-2012.

J.Infect Dis (Lond). 2016;48(3):195-200.

9 Himmelreich H, Rabenau HF, Rindermann M, Stephan C, Bickel M, Marzi I, Wicker

S.

The management of needlestick injuries. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013 Feb;110(5):61-7.

10 Frijstein G, Hortensius J, Zaaijer HL. Needlestick injuries and infectious patients in a

major academic medical centre from 2003 to 2010. Neth J Med. 2011

Oct;69(10):465-8.

11 Wiboonchutikul S, Thientong V, Suttha P, Kowadisaiburana B, Manosuthi W.

Significant intolerability of efavirenz in HIV occupational postexposure prophylaxis. J

Hosp Infect. 2016 Apr;92(4):372-7.

12 Woode Owusu M, Wellington E, Rice B, Gill ON, Ncube F & contributors. Eye of the

Needle United Kingdom Surveillance of Significant Occupational Exposures to

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 16 of 21

Bloodborne Viruses in Healthcare Workers: data to end 2013. December 2014.

Public Health England, London.

13 Black RJ. Animal studies of prophylaxis. Am J Med 1997;102:39–44. 14 Tsai CC,

Emau P, Follis KE, et al. Effectiveness of postinoculation (R)-9-(2-phos-

phonylmethoxypropyl) adenine treatment for prevention of persistent simian

immunodeficiency virus SIVmne infection depends critically on timing of initiation

and duration of treatment. J Virol 1998;72:4265–73.

14 Otten RA, Smith DK, Adams DR, et al. Efficacy of postexposure prophylaxis after

intravaginal exposure of pig-tailed macaques to a human-derived retrovirus (human

immunodeficiency virus type 2). J Virol 2000;74:9771–5.

15 Beekmann SE, Henderson DK. Prevention of human immunodeficiency virus and

AIDS: postexposure prophylaxis (including health care workers). Infect Dis Clin

North Am. 2014 Dec;28(4):601-13.

16 Hawkins DA1, Asboe D, Barlow K, Evans B. Seroconversion to HIV-1 following a

needlestick injury despite combination post-exposure prophylaxis. J Infect. 2001

Jul;43(1):12-5.

17 Panlilio AL, Cardo DM, Grohskopf LA, Heneine W, Ross CS. Updated U.S. Public

Health Service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to HIV

and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;

54:1–17.

18 Camacho-Ortiz A. Failure of HIV postexposure prophylaxis after a work-related

needlestick injury. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012; 33:646–7.

19 Borba Brum MC, Dantas Filho FF, Yates ZB, Vercoza Viana MC, Martin Chaves

EB, Trindade DM. HIV seroconversion in a health care worker who underwent

postexposure prophylaxis following needlestick injury. Am J Infect Control. 2013;

41:471–2.

20 Updated U.S. Public Health Service Guidelines for the Management of

Occupational Exposures to HBV, HCV, and HIV and Recommendations for

Postexposure Prophylaxis MMWR June 29, 2001/50(RR11);1-42

21 Tomkins SE, Elford J, Nichols T, Aston J, Cliffe SJ, Roy K, Grime P, Ncube FM.

Occupational transmission of hepatitis C in healthcare workers and factors

associated with seroconversion: UK surveillance data.J Viral Hepat. 2012

Mar;19(3):199-204.

22 Yazdanpanah Y, De Carli G, Migueres B, Lot F, Campins M, Colombo C, Thomas

T, Deuffic-Burban S, Prevot MH, Domart M, Tarantola A, Abiteboul D, Deny P, Pol

S, Desenclos JC, Puro V, Bouvet E.

Risk factors for hepatitis C virus transmission to health care workers after

occupational exposure: a European case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Nov

15;41(10):1423-30.

23 Beltrami EM, Kozak A, Williams IT, Saekhou AM, Kalish ML, Nainan OV, Stramer

SL, Fucci MC, Frederickson D, Cardo DM. Transmission of HIV and hepatitis C

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 17 of 21

virus from a nursing home patient to a health care worker. Am J Infect Control. 2003

May;31(3):168-75.

24 Toda T, Mitsui T, Tsukamoto Y, Ebara T, Hirose A, Masuko K, Nagashima S,

Takahashi M, Okamoto H. Molecular analysis of transmission of hepatitis C virus in

a nurse who acquired acute hepatitis C after caring for a viremic patient with

epistaxis. J Med Virol. 2009 Aug;81(8):1363-70.

25 Michael Strasser, Elmar Aigner, Ilse Schmid, Andreas Stadlmayr, David Niederseer,

Wolfgang Patsch and Christian Datz (2013). Risk of Hepatitis C Virus Transmission

from Patients to Healthcare Workers: A Prospective Observational Study. Infection

Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 34, pp 759-761

26 Eskandarani HA, Kehrer M, Christensen PB.No transmission of blood-borne viruses

among hospital staff despite frequent blood exposure. Dan Med J. 2014

Sep;61(9):A4907.

27 Davanzo E, Frasson C, Morandin M, Trevisan A. Occupational blood and body fluid

exposure of university health care workers. Am J Infect Control. 2008

Dec;36(10):753-6.

28 Ryoo SM, Kim WY, Kim W, Lim KS, Lee CC, Woo JH. Transmission of hepatitis C

virus by occupational percutaneous injuries in South Korea.J Formos Med Assoc.

2012 Feb;111(2):113-7.

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 18 of 21

APPENDIX A: MANAGEMENT OF THE EXPOSED HCW FOLLOWING

AN OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURE

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 19 of 21

APPENDIX B: RECOMMENDED LABORATORY TESTING FOR THE

EXPOSED HCW

BBV status of the

source patient

#

Time (in weeks) following BBV exposure

6 weeks

12 weeks

24 weeks

HIV positive

Combined HIV

antigen and antibody

(fourth generation HIV

immunoassay)

Combined HIV

antigen and antibody

(fourth generation HIV

immunoassay)

HBV positive*

Hepatitis B surface

antigen

Hepatitis B surface

antigen

Hepatitis B surface

antigen

HCV positive

Hepatitis C antibody,

qualitative HCV PCR

Hepatitis C antibody

Hepatitis C antibody

#

If BBV testing of the source patient at the time of the incident is negative but there is the

possibility of being in the window period or BBV status of the source is unknown and there is a

risk of being infected then follow up as per positive source.

* If the HCW is immune (i.e. anti-HBs level ≥10 mIU/mL or HBcAb positive) no further HBV

testing is required regardless of the exposure or status of the source patient.

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 20 of 21

APPENDIX C: HIV PEP RECOMMENDATIONS

HIV PEP starter packs may very between facilities. The Australasian Society for HIV

Medicine (ASHM) recommendations are provided here.

Recommendations for PEP following occupational exposure to HIV

2

2-drug regimens*

Tenofovir 300mg with lamivudine 300mg (daily) *(TGA approved generic lamivudine may be used

to reduce cost)

OR

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine 300mg/200mg (daily)

*

Zidovudine, in combination with lamivudine, can be used in two-drug PEP combinations. The benefits of

cheaper zidovudine cost are offset by the need for a twice-daily treatment regimen, higher incidences of

gastrointestinal side effects, myalgia and headaches in comparison to the recommended regimens.

3-drug regimens

The preferred 2 drug-regimen PLUS

dolutegravir 50mg (daily)

OR

raltegravir 400mg (bd)

OR

rilpivirine 25mg (daily with food)

Note: Refer to Post Exposure Prophylaxis after Non-Occupational and Occupational Exposures: Australian

National Guidelines 2nd Edition for cautions in relation to specific antiretroviral medications

2

Taken from the Post Exposure Prophylaxis after Non-Occupational and Occupational Exposures:

Australian National Guidelines 2

nd

Edition

PD2017_010

Issue date: May-2017

Page 21 of 21

APPENDIX D HEPATITIS B PEP RECOMMENDATIONS

Management of non-immune HCWs following occupational exposure to a positive/likely

positive HBsAg source

3

Type of exposure

Hepatitis B Immunoglobulin

Vaccine

Percutaneous, ocular or

mucous membrane

Single dose of 400IU by IM

injection within 72 hours of

exposure

1ml recombinant antigen by IM

injection within 7 days* of

exposure, repeated at 1 month

and again 6 months post first

dose

*The 1st dose can be given at the same time as HBIG, but should be administered at a separate site.

Administration as soon as possible after exposure is preferred.

3

Taken from the Australian Immunisation Handbook, 10

th

Edition