COLLEGE

READINESS

Rigor at Risk:

Reaffirming Quality

in the High School

Core Curriculum

ACT is an independent, not-for-profit organization that provides

assessment, research, information, and program management

services in the broad areas of education and workforce development.

Each year we serve millions of people in high schools, colleges,

professional associations, businesses, and government agencies,

nationally and internationally. Though designed to meet a wide array

of needs, all ACT programs and services have one guiding purpose—

helping people achieve education and workplace success.

© 2007 by ACT, Inc. All rights reserved. IC 0508A2070 9437

Rigor at Risk:

Reaffirming Quality in the

High School Core Curriculum

Contents

A Message from the President and COO of

ACT’s Education Division ......................................................... iii

Introduction ................................................................................... 1

1. The Core Curriculum: An Unfulfilled Promise ............. 5

2. A Rigorous Core: Aligning the Essentials ..................... 15

3. The Impact of Rigor: Real Evidence of Progress ........ 26

4. It Can Be Done .................................................................. 30

Appendix ..................................................................................... 35

References ................................................................................... 47

i

iii

A Message from the President and COO

of ACT’s Education Division

For decades, ACT research has consistently shown that high school

students who take a minimum recommended core curriculum—four

years of English and three years each of mathematics, science, and

social studies—are likely to be more prepared for college when they

graduate than are students who do not take this curriculum.

But in recent years it has become increasingly apparent that, while

taking the right number of courses is certainly better than not, it is no

longer enough to guarantee that students will graduate ready for life

after high school. Only one-quarter of ACT-tested 2006 high school

graduates who took a core curriculum were prepared to take credit-

bearing entry-level college courses in all four subject areas with a

reasonable chance of succeeding in those courses. Even students

who take a number of additional higher-level courses beyond the

minimum core curriculum are not always likely to be ready for

college either.

We at ACT believe that these findings are evidence of a need for

greater rigor in the high school core curriculum—specifically, the

need for high school core courses to focus on the essential

knowledge and skills needed for success in postsecondary

education. This report identifies the large gap between secondary

and postsecondary education in the U.S. and focuses on successful

strategies for eliminating this gap. Our nation’s high schools must

offer every student a rigorous core curriculum that will prepare them

for college and work by the time they graduate.

It is time to reaffirm quality in the high school core curriculum.

We can meet the challenge.

Cynthia B. Schmeiser

President and Chief Operating Officer, ACT Education Division

March 2007

1

Introduction

Among the motivations behind the federal government’s publication of

A Nation at Risk

(National Commission on Excellence in Education, 1983) were the

desire to see more students graduate from high school prepared for college and

work and the need for more students to attend college. Another motivation was the

importance of enabling more first-year college students to succeed in college: that

is, to perform well in their courses, return to college for their second year (and

beyond), and persist to a degree. The authors of

A Nation at Risk

proposed, among

other recommendations, that every high school in

the United States require its graduates to take a

“core” curriculum: a minimum number of courses

designed to provide students with a “foundation of

success for the after-school years” (p. 24). This

foundation would consist of a set of universal

knowledge and skills that graduates would be able

to put to good use regardless of their specific

educational or work objectives.

Since then, almost every state has made

significant efforts to improve its education system.

Nearly a quarter-century later, in a climate in which

U.S. workers are dealing with new forms of

technology and facing the challenges of a global

economy, it is not only reasonable but increasingly

urgent to ask: Have we succeeded in fulfilling the

goals of

A Nation at Risk

?

ACT research has consistently shown that

high school students who take a minimum

recommended core curriculum—four years of

English and three years each of mathematics, science, and social studies—are

likely to be more prepared for college when they graduate than are students who

do not take this curriculum. Decades of research bear out this recommendation.

However, in recent years it has become increasingly apparent that, while taking

the right

number

of courses is certainly better than not, it is no longer enough to

guarantee that students will graduate ready for life after high school (Dougherty,

Mellor, & Jian, 2006). A powerful example of this is the fact that, as defined by

ACT’s national college readiness indicators, the ACT College Readiness

Benchmarks, three out of four ACT-tested 2006 high school graduates who take a

core curriculum are not prepared to take credit-bearing entry-level college courses

with a reasonable chance of succeeding in those courses (Figure 1).

We recommend

that state and local

high school graduation requirements be

strengthened and that, at a minimum, all

students seeking a diploma be required to

lay the foundations in the Five New Basics

by taking the following curriculum during their

4 years of high school: (a) 4 years of English;

(b) 3 years of mathematics; (c) 3 years of

science; (d) 3 years of social studies; and

(e) one-half year of computer science. For the

college-bound, 2 years of foreign language in

high school are strongly recommended in

addition to those taken earlier.

Whatever the student’s educational or work

objectives, knowledge of the New Basics is the

foundation of success for the after-school years

and, therefore, forms the core of the modern

curriculum.

—National Commission on Excellence

in Education, 1983

These statistics for the ACT-tested high school graduating class

of 2006 who took a core curriculum suggest that about one-fourth

of these students are ready for college-level work in English,

mathematics, social science, and natural science, while about

one-fifth are not ready in any of these subject areas and the

remaining students (more than half) are ready in one to three areas

but not in all. Altogether, approximately 74 percent

of ACT-tested 2006 high school graduates who

took a core curriculum lack at least some of the

skills needed for postsecondary success. Most of

these students may need only a small amount of

additional preparation to be ready for college, but

19 percent need substantial help in all four subject

areas in order to be ready for college-level work.

ACT research also suggests that students today

do not have a reasonable chance of becoming

ready for college unless they take a number of

additional higher-level courses beyond the

minimum core, and that even students who do

take these additional higher-level courses are not

always likely to be ready for college either. This

finding is in part a reflection on the quality and intensity—in other

words, the

rigor

—of the high school curriculum. Without improving the

quality and content of the core, it appears that most students need to

take additional higher-level courses to learn what they should have

learned from a rigorous core curriculum, with no guarantee even then

that they will be prepared for college-level work.

Is it no longer reasonable to expect, as did the authors of

A Nation

at Risk

, that students should be ready for college after satisfactory

completion of a core curriculum? While additional courses beyond

core appear to be necessary for college readiness for many students,

in the long run this is neither a reasonable expectation nor a viable

strategy.

Although academic achievement is just one aspect of college

readiness, it is arguably the most important one. What is now clear

is that taking the right

kind

of courses matters just as much as taking

the right number of courses. The academic quality and intensity of

the high school curriculum is a key determinant of success in

postsecondary education (ACT, 2004a; ACT, 2005; Adelman, 2006).

2

met no

Benchmarks

26%

55%

19%

met 1 to 3

Benchmarks

met all 4

Benchmarks

Figure 1: ACT College Readiness

Benchmark Attainment

1

of Students

Taking Core Curriculum, by Number

of Benchmarks Attained (2006 High

School Graduates)

2

1

The ACT College Readiness Benchmarks are scores on the ACT

®

test that represent the level of

achievement required for students to have a high probability of success in selected credit-bearing

first-year college courses.

2

Based on 647,298 high school students who took the ACT and indicated both that they had taken

or planned to take the ACT-recommended core curriculum (see sidebar, p. 6) and that they would

graduate from high school in 2006.

3

It is neither realistic nor justifiable to expect all high school students

to take more and more courses to learn what they need to learn for

college. The essential agenda is to improve the quality of core

courses that

really

matter in preparing students for college and work.

An unfortunate reality is that the essential foundations in our

educational system needed to support a rigorous core are lacking.

Most state standards do not define rigorous outcomes at the course

level, so teachers are not teaching to essential course outcomes and

students aren’t learning them (ACT & The Education Trust, 2004).

In addition, most states do not require specific courses as

prerequisites for high school graduation, thus providing insufficient

direction to schools, teachers, students, or parents about what

courses are important for graduation. Meanwhile, there is a persistent

gap between postsecondary expectations and what high schools are

teaching, and a perceptual gap in how college instructors and high

school teachers view the preparedness of entering college students

for college-level work. The lack of such crucial supports has a direct

and dramatic impact on our students, whose chances at future

success are hurt by the persistent gap between the high school

experience and the more challenging requirements of postsecondary

institutions.

In today’s competitive global economy this gap can no longer

be tolerated (Ohio Business Roundtable, 2006; Peter D. Hart

Research Associates/Public Opinion Strategies, 2005). U.S. students

must possess the knowledge and skills to be able to compete with

workers in other countries, especially in high-growth fields (such

as engineering and computer technology) that require a solid

mathematics and science background. As we will see in the

chapters that follow, without immediate improvements in educational

standards, high school graduation requirements, teacher training,

the alignment of elementary and secondary education with

postsecondary expectations, and the vertical and horizontal

alignment of high school courses, the gap between high school and

postsecondary expectations may not only persist but grow larger.

So what can be done? The time has come to improve the quality of

core courses so that all students have equal opportunities to become

prepared for postsecondary education—whether in a two-year or

four-year institution—and for work. The purposes of this report are to

examine the gap between secondary and postsecondary education

in the U.S. and to focus on successful strategies for eliminating this

gap so that all high school graduates learn the essential skills they

need to be successful in college and work.

It is time to reaffirm quality in the high school core curriculum.

5

1.

The Core Curriculum:

An Unfulfilled Promise

Far too many students who take a core curriculum

today are underprepared for the challenges of

first-year college coursework.

Improving college readiness is crucial to the development of a

diverse and talented labor force that is able to maintain and increase

U.S. economic competitiveness throughout the world. But in addition

to providing a stronger workforce for our

nation, improved college readiness will

provide a better and more rewarding quality

of life for our citizens.

What do we mean by readiness for college?

ACT uses the phrase to refer to the level of

preparation a student needs to be ready to

enroll and succeed—without remediation—

in a credit-bearing course at a two-year or

four-year institution, trade school, or

technical school. The ACT College

Readiness Benchmarks represent the level

of achievement required for students to

have a high probability of success (a 75

percent chance of earning a course grade

of C or better, or a 50 percent chance of

earning a B or better) in such credit-bearing

first-year college courses as English

Composition, Algebra, introductory social

science, and Biology. The Benchmarks

correspond to scores on the ACT English,

Mathematics, Reading, and Science Tests, respectively.

Today we have empirical evidence that college readiness also means

workplace readiness. While not every student plans to attend college

after high school, many of the jobs now being created in a highly

technology-based economy require a level of knowledge and skills

comparable to that expected of the first-year college student (ACT,

2006c). College and work readiness should therefore be an

expectation not only for traditional college-bound high school

students, but for all students at the high school level.

EXPLORE and PLAN College Readiness

Benchmarks: Earlier Progress Checks

ACT has also established College Readiness

Benchmarks for EXPLORE

®

and PLAN

®

, the two

additional components of ACT’s Educational Planning

and Assessment System (EPAS

™

). (See the Appendix

for detailed information about EPAS.) These scores

indicate whether students, based on their performance

on EXPLORE (grade 8) or PLAN (grade 10), are on

target to be ready for first-year college-level work

when they graduate from high school.

Test EXPLORE PLAN The ACT

English 13 15 18

Mathematics 17 19 22

Reading 15 17 21

Science 20 21 24

6

To help our students become ready for college and the workplace, we

must ensure that they prepare. Typically, such preparation consists of

the courses students take in high school—which in turn assumes that

basic skills have been acquired in the years preceding high school.

For decades, ACT research has shown that students who take the

minimum recommended number of core courses in a high school

subject area (four years of English, three

years each of mathematics, science, and

social studies) attain higher ACT scores

than those students who take less than core.

Figure 2 shows the average ACT scores of

2006 high school graduates who reported

taking (or planning to take) the core

curriculum compared to those who did not.

Students who take a minimum core curriculum also meet the ACT

College Readiness Benchmarks in greater percentages than students

who take less than core. As we saw in Figure 1 (p. 2), 26 percent of

ACT-tested 2006 high school graduates who took core met all four

College Readiness Benchmarks, 55 percent met one to three

Benchmarks, and 19 percent met no Benchmarks. In comparison,

Ready for College and Ready for

Work: Same or Different?

Results of a recent ACT study (ACT, 2006c) provide

empirical evidence that, whether planning to enter

college or workforce training programs after

graduation, high school students need to be

educated to a comparable level of readiness in

reading and mathematics. Graduates need this

level of readiness if they are to succeed in college-

level courses without remediation and to enter

workforce training programs ready to learn

job-specific skills.

We reached this conclusion by:

▼

Identifying the level of reading and mathematics

skills students need to be ready for entry-level

jobs that require less than a bachelor’s degree,

pay a wage sufficient to support a family, and

offer the potential for career advancement

▼

Comparing student performance on ACT tests

that measure workforce readiness with those

that measure college readiness

▼

Determining if the levels of performance needed

for college and workforce readiness are the

same or different

The study results convey an important message

to U.S. high school educators and high school

students: We should be educating all high school

students according to a common academic

expectation, one that prepares them for both

postsecondary education and the workforce. Only

then—whether they are among the two-thirds who

enter college directly after graduation or those who

enter workforce training programs—will they be

ready for life after high school.

Although the contexts within which these

expectations are taught and assessed may differ,

the level of expectation for all students must be

the same. Anything less will not give high school

graduates the foundation of academic skills they

will need to learn additional skills as their jobs

change or as they change jobs throughout their

careers. Opportunities for rigorous coursework

should not be limited only to those students who

have traditionally been considered most able to

benefit from them. The results of this study provide

ample evidence that we must move the agenda

for high school redesign in a direction that will

prepare all students for success, no matter which

path they choose after graduation.

ACT’s Recommended Core Curriculum

▼

English: at least four years

▼

Mathematics: at least three years

▼

Social studies: at least three years

▼

Natural sciences: at least three years

7

3

Based on 1,061,186 high school students who took the ACT and indicated that they would

graduate from high school in 2006. ACT scores are reported on a scale from 1 to 36.

4

Two analyses were conducted, one using students with high school grade point averages of

0.00 to 2.99 (English: 247,365; Mathematics: 214,036; Social Studies: 212,775; Science: 185,910)

and the other using students with high school grade point averages of 3.00 to 4.00 (English:

592,714; Mathematics: 568,649; Social Studies: 527,248; Science: 542,545).

5

Based on 940,780 high school students who took the ACT and indicated that they would graduate

from high school in 2006.

just 14 percent of ACT-tested 2006 high school graduates who did

not take core met all four Benchmarks, 50 percent met one to three

Benchmarks, and 36 percent met no Benchmarks.

However, if we look at ACT-tested 2006 high school

graduates who took more than the recommended core (in

other words, graduates who took core plus additional higher-

level courses) we find both evidence of progress and signs of

a troubling pattern. The evidence of progress is seen in all

four subject areas (Figures 3 through 6), where the ACT

College Readiness Benchmark attainment of graduates who

took more than the minimum core is greater—sometimes

substantially greater—than that of graduates who took only

the core. In nearly all cases, Benchmark attainment increases

as the number of additional beyond-core courses increases.

These positive results are also seen for low-achieving

students who take these courses as well as for high-achieving

students.

4

Because students select the courses they take, student

achievement associated with taking different numbers of courses

reflects not only the contribution of course content but also the

achievement level of the students who elect to take a particular

number of courses. When student achievement level is controlled

Less than Core

Core

Mathematics

Reading Science Composite

English

21.6

19.0

21.8

19.4

22.3

20.1

21.7

19.7

22.0

19.7

36

30

24

18

12

6

0

Average ACT Composite Score

Figure 2: Average ACT Composite Scores for Students Taking and

Not Taking the Core Curriculum (2006 High School Graduates)

3

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

77

67

4.5 years

4 years (Core)

Percent Meeting Benchmark

Number of Years of English

Figure 3: ACT College

English Benchmark

Attainment by English

Course Sequence (2006

High School Graduates)

5

using students’ self-reported high school grade point average and

grade level to more clearly isolate the effect of taking each number of

courses, we found that, regardless of achievement level, students

who took more than core coursework are substantially more likely to

be ready for college than students who take only the core.

Yet the signs of a troubling pattern are also evident: even when

students take substantial numbers of additional courses, no more

than three-fourths of them are ready for first-year college coursework

in mathematics, social science, or natural science. Only in English

The Core Curriculum: A Brief History

With rare exceptions such as the National Defense

Education Act of 1958, a concerted attempt to

make U.S. students competitive in science with

students elsewhere in the world, the U.S.

government before 1983 generally did not involve

itself in educational matters beyond ensuring equal

access or providing for students with special needs.

But in 1983, the National Commission on

Excellence in Education published

A Nation at

Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform.

The commission, created in 1981 by Secretary

of Education Terrel Bell, was charged with

examining the quality of learning and teaching

in U.S. schools—especially high schools—and

recommending practical improvements. Among

its recommendations, the commission called for

strengthening state and local high school

graduation requirements, including establishing

a minimum number of basic courses for all

students as well as a slightly more ambitious

curriculum for college-bound ones. In addition,

they called for schools, colleges, and universities

to “adopt more rigorous and measurable

standards, and higher expectations, for

academic performance and student conduct,

and that four-year colleges and universities raise

their requirements for admission.” (Vinovskis

2003, p. 120)

The commission identified the minimum number

of basic courses as four years of English, three

years of mathematics, three years of science,

three years of social studies, and one-half year of

computer science. Two years of a foreign language

were also strongly recommended for the college

bound (National Commission on Excellence in

Education, 1983).

Before 1983, states had mandated that schools

must provide certain minimal levels of courses,

largely only to guarantee that the schools met state

constitutional requirements for educational

provision. But in the two decades since the

publication of

A Nation at Risk,

nearly every state

has made significant efforts to improve its education

system. According to Fuhrman (2003), these efforts

have come in roughly three stages: the excellence

movement (from 1983 to about 1987), which

emphasized increased core-course requirements

and student assessments; the restructuring

movement (from about 1987 to about 1990), which

focused on improving school management; and

the standards movement (from about 1990 to the

present), which has dealt with creating substantive

expectations for what students should know and

be able to do in each core subject area.

Although the first two stages produced few if any

improvements in student achievement (Finn, Jr.,

1991; Fuhrman, 2003; Toch, 1991; Vinovskis, 2003),

the standards movement has fared somewhat

better, particularly in mathematics (Fuhrman, 2003).

However, much of the work of this movement

remains incomplete. Fuhrman (2003) writes:

Curricular improvement was never as widespread

as hoped; policymakers left developing

curriculum tied to standards up to schools rather

than investing deliberately in it. Moreover, the

standards often were vague, too vague to guide

decisions about specific curricula . . . . (p. 11)

Weak standards and a lack of challenging curricula:

to a great extent, this is the world that U.S. high

school students still live in today.

8

9

(Figure 3) does the percentage of

students who are ready for college-

level work after taking additional

courses in high school exceed

75 percent.

Of those students who take a

core mathematics curriculum, only

16 percent are ready for a credit-

bearing first-year College Algebra

course (see Figure 4). It is not until

students take one full year of

additional mathematics courses beyond

the core that we see more

than half (62 percent) of ACT-tested

students ready for college-level

work in mathematics.

In social studies (Figure 5), 50

percent of students who take a core

curriculum are ready for an

introductory college social science

course. This percentage increases

to 60 percent for students taking

one-and-a-half years of additional

higher-level social studies courses

in high school.

In science (Figure 6), 26 percent of

students taking the science core are

ready for a credit-bearing college Biology course;

although this percentage rises to 38 for students taking

an additional year of science, that still leaves more than

6 students in 10 who are not ready for college-level

science after having taken four years of science in high

school. So even taking additional higher-level coursework

in high school does not lead to increased college

readiness for many students.

Why should so many students who take a core curriculum

in high school be unprepared for the challenges of first-

year college coursework? Why should it be necessary for

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

50

3.5 years3 years

(Core)

Percent Meeting Benchmark

Number of Years of Social Studies

55

60

53

4 years 4.5 years

Figure 5: ACT College Reading Benchmark

Attainment by Social Studies Course Sequence

(2006 High School Graduates)

7

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

16

3.5 years3 years

(Core)

Percent Meeting Benchmark

Number of Years of Mathematics

62

75

38

4 years 4.5 years

Figure 4: ACT College Mathematics Benchmark

Attainment by Mathematics Course Sequence

(2006 High School Graduates)

6

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

38

26

4 years3 years

(Core)

Percent Meeting Benchmark

Number of Years of Science

6

Based on 872,949 high school students who took the ACT and indicated that they would

graduate from high school in 2006.

7

Based on 822,620 high school students who took the ACT and indicated that they would

graduate from high school in 2006.

8

Based on 808,359 high school students who took the ACT and indicated that they would

graduate from high school in 2006.

Figure 6: ACT College

Science Benchmark

Attainment by Science

Course Sequence (2006

High School Graduates)

8

10

students to take additional courses beyond the core in order to prepare

for credit-bearing first-year college courses? And why should so many

of even these students still graduate unprepared? Perhaps the

underlying reason is that high school core courses lack rigor and are

simply not focused on the essential outcomes that postsecondary

institutions want their entering students to know and be able to do.

Should it not still be our expectation today—as it was for the authors of

A Nation at Risk

—that students who satisfactorily complete a core

curriculum be ready for college?

Rigor and Remediation

Insufficient course rigor increases burdens

on students, colleges, and taxpayers.

If the goal of high school is to prepare all students for some type

of postsecondary education (whether it be a four-year college or

university, a two-year community college, or a targeted workforce

training program), then it should be clear that the high school

curriculum must address the academic demands these forms of

postsecondary education make on high school graduates. A rigorous

high school core curriculum must above all teach students the essential

knowledge and skills needed for success in postsecondary education.

However, because too few graduates are learning these essentials,

many of them are taking remedial courses in college, resulting in

estimated nationwide expenditures of $1.4 billion for tuition and other

costs at community colleges alone (Alliance for Excellent Education,

2006). Figure 7 shows by mathematics course sequence the

percentages of ACT-tested high school graduates in three states from

1993 through 2004 who took remedial mathematics courses during

their first year of college. Note that while 26 percent of the graduates

who took or planned to take Algebra I, Algebra II, and Geometry in

high school took remedial mathematics courses in college, as many as

17 percent who had taken an additional higher-level mathematics

course beyond these three also needed remediation.

The need for such remedial coursework is a problem not just for

students and colleges but for society at large. According to the Alliance

for Excellent Education (2006), “Community colleges already bear the

greatest share of the remediation burden, and trends indicate that their

responsibilities in this arena are likely to grow” (p. 2). And because

state and local governments provide subsidies to many community

colleges on top of the tax monies already allocated to their high

schools, “taxpayers are essentially paying twice for the coursework and

skill development students are expected to receive in high school” (p. 3).

If postsecondary remediation rates continue to increase as predicted,

then it is even more incumbent upon high schools to provide students

with the rigorous education they deserve.

Preparing High School Students for

College: The Failure Rate Is Exceeding

the Success Rate

While some students make progress toward college

readiness in high school, a larger percentage of

students are actually failing to meet ACT’s College

Readiness Benchmarks.

Another symptom of the lack of rigor in high school is that students are

actually losing momentum in progress toward college readiness during

the high school years. We examined student progress from eighth to

tenth to twelfth grade by studying students in three consecutive

graduating classes who were tested using all three components of ACT’s

Educational Planning and Assessment System (EPAS): EXPLORE, PLAN,

and the ACT. In this way, the actual progress students make as they

take each program during their passage from junior high to high school

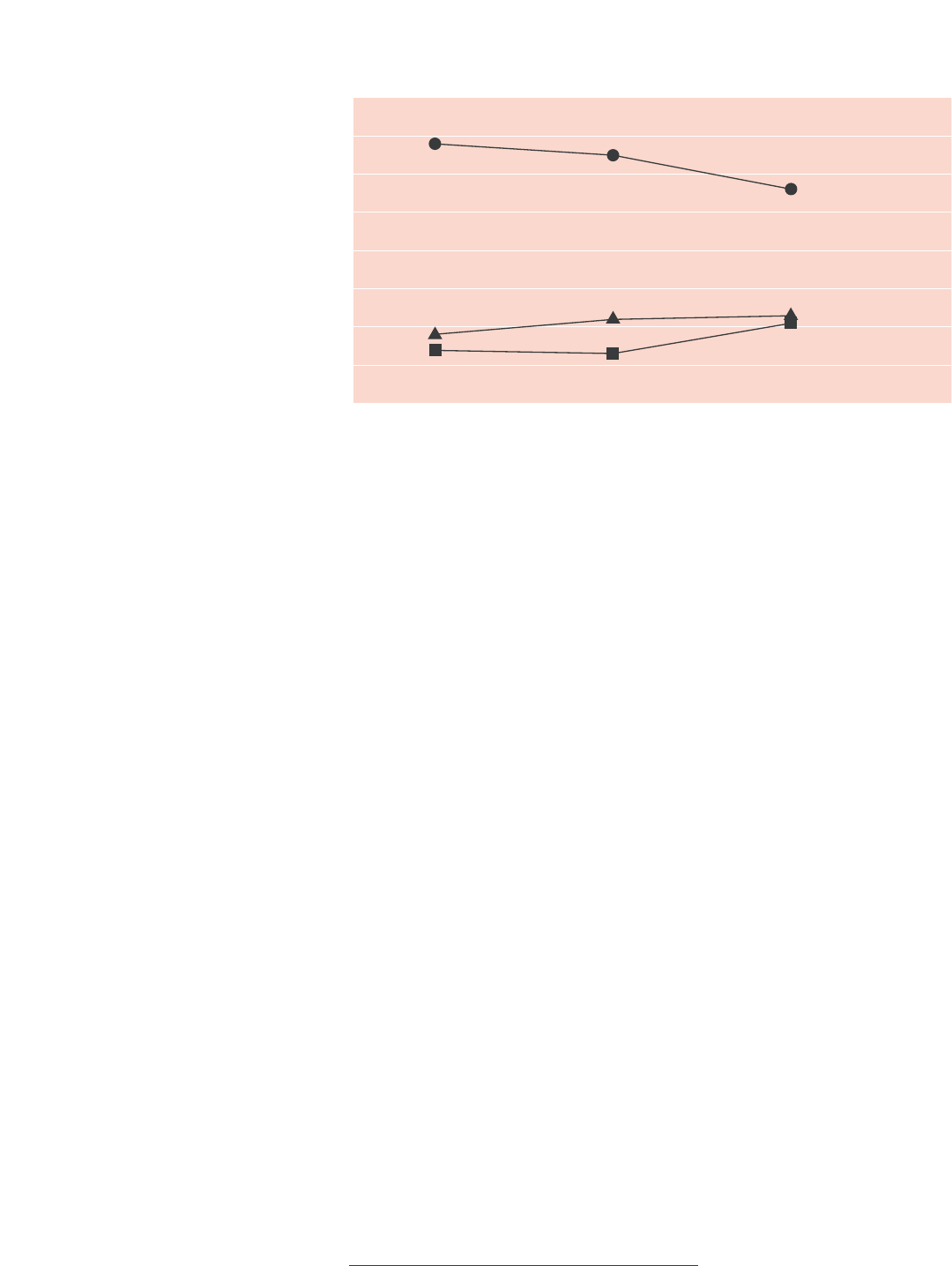

graduation can be evaluated. Figure 8 shows the change from one

11

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

26

Algebra I,

Algebra II,

Geometry, Other

Advanced Math

Algebra I, Algebra II,

Geometry

Percent Taking Remedial Mathematics Courses

Mathematics Course Sequence

Algebra I,

Algebra II,

Geometry,

Trigonometry

Algebra I,

Algebra II,

Geometry,

Trigonometry,

Other Advanced Math

Algebra I,

Algebra II,

Geometry,

Trigonometry,

Calculus

17

10

6

4

Figure 7: Percentages of ACT-tested High School Graduates

in Three States Taking Remedial Mathematics Coursework

during Their First Year of College, by Mathematics

Course Sequence (1993–2004)

9

9

Based on 81,574 high school students in three states who took the ACT between 1992–1993 and

2003–2004 and indicated that they would graduate from high school during the relevant year, and

who, according to data from institutions participating in ACT’s College Success Profile Service,

took remedial coursework during their first year of college.

12

program to the next in the distribution of students who met none, one

to three, or all four College Readiness Benchmarks associated with

each program.

While there is a slow but steady increase in the percentages of

students meeting all four Benchmarks (from 18 to 23 percent),

there is also a net increase in the percentages of students meeting

no

Benchmarks—with all of the increase occurring between tenth

and twelfth grades (from 13 to 21 percent). There is also a fairly

rapid decline in the percentage of students meeting one to three

Benchmarks (from 68 to 56 percent). The rate of decline of the

percentage of students meeting some of the Benchmarks

(12 percentage points from EXPLORE to the ACT) is more rapid than

the rate of increase in students who have become fully ready for

college (five percentage points from EXPLORE to the ACT). And there

is a seven percentage-point increase in students who are

no longer

on target

to be ready for college at all. These statistics reveal that the

rate of failure is exceeding the rate of success when it comes to

preparing high school students for college. And this does not

account for students who have dropped out of high school along

the way.

Percent Meeting No. of Benchmarks

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

EXPLORE

PLAN

The ACT

(No Benchmarks)

68

(All 4 Benchmarks)

(1 to 3 Benchmarks)

18

14

22

13

56

23

21

65

Figure 8: College Readiness Benchmark Attainment in

Grades 8, 10, and 12 for EPAS-tested Students, by Number

of Benchmarks Attained (High School Graduating Classes

of 2003 through 2005)

10

10

Based on 284,898 students who took all three EPAS programs and indicated that they would

graduate from high school in 2003, 2004, or 2005.

13

Students are Losing Momentum in

Grades 11 and 12

Much of the loss of momentum appears to be

occurring during the last two years of high school.

Figure 9 shows College Readiness Benchmark attainment by subject

area for students who took all three EPAS programs and graduated

from high school in 2003, 2004, or 2005.

In English, momentum toward college readiness remained stable

between grades 8 and 10, and then declined substantially between

grades 10 and 12. In Mathematics, momentum toward college

readiness declined steadily from grade 8 to grade 12. In Reading,

momentum toward college readiness increased slightly between

grades 8 and 10, and then declined substantially between grades 10

and 12. In Science, momentum toward college readiness increased

between grades 8 and 10, but leveled off between grades 10 and 12.

In three out of four high school subject areas, levels of potential

college readiness either achieved or sustained in tenth grade are

being more than offset by losses in momentum toward college

Percent Meeting Benchmark

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

English Mathematics Reading Science

EXPLORE

PLAN

The ACT

83

75

83

48

42

45

62

55

63

22

2929

Figure 9: College Readiness Benchmark Attainment in

Grades 8, 10, and 12 for EPAS-tested Students

(High School Graduating Classes of 2003–2005)

11

11

Based on 284,898 students who took all three EPAS programs and indicated that they would

graduate from high school in 2003, 2004, or 2005.

readiness between grades 10 and 12. Only in Science are proportionally

more students ready for college-level work than were on target to be

ready when they entered high school.

Summary

There appears to be substantial evidence that, in too many high schools,

taking the right number of core courses is failing to prepare students for

college and work. Of those ACT-tested 2006 high school graduates who

took a core curriculum, only 26 percent were ready for credit-bearing

entry-level college coursework in all four subject areas. Many of the

remaining students will likely need to take one or more remedial courses

in college.

Of those graduates who took more than a core curriculum, only

62 percent are ready for college-level mathematics coursework after

having taken an additional year of mathematics in high school, while just

38 percent are ready for college-level science coursework after taking

an additional year of science. In mathematics, at least one additional year

of coursework is required to meet the modest goal of preparing even half

of high school graduates for entry-level college courses; in science, not a

single course sequence tracked by ACT produced more than 45 percent

of students who are ready for college-level science (ACT, 2006a). Only

in English are we seeing the core curriculum alone preparing a majority

of graduates for their first year of college coursework.

We also see a strong trend that students are losing momentum in

progress toward college readiness during high school, and that this

loss of momentum appears to be occurring most dramatically in

grades 11 and 12.

In the next chapter, we examine the critical role that alignment plays

in helping students graduate from high school ready for college.

Specifically, we examine the need to align the essentials necessary for

college readiness—state standards, graduation requirements, core

course standards, teaching, and assessment—if we are to fulfill the

expectation, expressed in

A Nation at Risk,

that all high school graduates

who satisfactorily complete a core curriculum are ready for college.

14

15

2.

A Rigorous Core:

Aligning the Essentials

The rigor of core courses is at risk in today’s

high schools unless we align a number of the

essentials for college readiness: state standards,

diploma requirements, core course standards,

teaching, and assessment.

The U.S. has always counted on the public school system to educate

its children in a manner that will best prepare them for their future.

For the most part, public schools have a clear sense of their mission

and are actively committed to educating all of their students. But

today it appears that some of the essentials for college readiness

are victims of misalignments in the system that actually work against

the goal of ensuring rigor in the core curriculum. In this chapter, as a

first step toward reaffirming quality in the high school core curriculum,

we examine these misalignments.

MISALIGNMENT: Diploma Requirements

Often Do Not Specify Core Courses

More than half the states do not require students to take

specific core courses in mathematics or science in order

to graduate from high school.

One of the barriers to ensuring that all students take courses of

sufficient rigor is that not enough states require that certain rigorous

courses be taken as prerequisites to high school graduation. Weak

diploma requirements often result in students not taking the courses

they need in order to be ready for college or work when they

graduate from high school.

We examined state diploma requirements either currently in effect

or scheduled to be implemented within the next two years. Table 1

summarizes the results of this investigation.

Just over half the 50 states require students to take any mathematics

courses at all in order to graduate. Of these 26 states, 12 require

Algebra II, and only four states require any mathematics beyond

Algebra II. ACT research has shown that Algebra II has a substantial

impact on student readiness for college (ACT, 2004a).

In science, while 30 of the 50 states require at least one course for

graduation, only 17 explicitly require Biology, one explicitly requires

Chemistry, and two explicitly require Physics. Four additional states

offer students a group of required courses from which to select, but

in these states a student could still avoid taking two or even all three

of the aforementioned science courses. It is clear, therefore, that

even today more than half of the states do not specify particular core

courses in either mathematics or science, even though these courses

have been shown to have a dramatic impact on college readiness.

MISALIGNMENT: Lack of

Alignment between Secondary

and Postsecondary Educators’

Expectations

High school teachers and college faculty

disagree about how well state standards

are preparing students for college.

The most recent National Curriculum Survey

(ACT, 2007a) suggests that high school and

college faculty disagree about the role that state

standards are playing in preparing students for

college. We surveyed thousands of secondary and

postsecondary educators nationwide, asking them

various questions about the courses they teach,

the academic achievement of the students who

take their courses, and aspects of the educational

climate in their state.

One major finding of the survey is that secondary

and postsecondary educators differ greatly in how

well they believe their state’s standards prepare students for college-

level work in the content area in which they teach. Figure 10 shows

16

The ACT National Curriculum Survey

®

All three components of EPAS (EXPLORE,

PLAN, and the ACT) measure achievement

because each is firmly based in the curriculum

of the grade level for which it is intended.

Every three to four years, we conduct our

National Curriculum Survey (ACT, 2007a), in

which we ask more than 20,000 educators

nationwide across grades 7–14 to identify the

knowledge and skills that are important for

students to know to be ready for first-year

college-level work. We examine the objectives

for instruction in grades 7 through 12 for all

states that have published such objectives.

We then analyze the information to refine the

scope and sequence for each section of each

EPAS assessment. In this way, rather than

imposing a test construct without empirical

support, EPAS is able to represent a

consensus among educators and curriculum

experts about what is important for students

to know and be able to do.

Any

(includes

Algebra II and

beyond)

Algebra II

Beyond

Algebra II

Any

(includes

Biology,

Chemistry,

and Physics)

Biology Chemistry Physics

26

(52%)

12

(24%)

4

(8%)

30

(60%)

17 to 21

(34% to 42%)*

1 to 5

(2% to 10%)*

2 to 6

(10% to 12%)*

Mathematics Science

Table 1: Current or Planned State Diploma Requirements in

Mathematics and Science (As of August 2006)

* Includes four states in which students select from among a group of required courses.

No. (%) of States

Requiring Course

17

the percentages of secondary and postsecondary educators who

answered this question “Well” or “Very Well” in the four content areas

covered by the ACT.

Postsecondary educators were about half as likely as secondary

educators to assert that state standards prepared students for

college-level work. Similarly, almost two-thirds of the postsecondary

instructors we surveyed responded that state standards prepared

students “Poorly” or “Very Poorly” for college-level work (ACT, 2007a).

High school teachers and college faculty also disagree about

the depth and breadth of essential state standards needed to

prepare students for college.

A second major point of difference between secondary and

postsecondary instructors is that high school teachers rated a much

larger number of topics and skills as being “important” or “very

important” for college success than did college instructors. This

parallels the tendency of many state standards to be broad and

inclusive rather than specific and selective (Finn, Jr., Julian, & Petrilli,

2006). It may be that the extensive nature of state standards forces

Percent Answering “Well” or “Very Well”

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Secondary Educators

Postsecondary Educators

76

33

79

42

English/Writing

67

32

Mathematics Reading Science

72

36

Note: This figure is adapted from

ACT National Curriculum Survey 2005–2006

, by ACT, Inc., 2007,

Iowa City, IA: Author.

12

Based on responses from 2,054 secondary instructors (363 English/Writing, 282 Mathematics,

305 Reading, and 1,104 Science) and 2,880 postsecondary instructors (401 English/Writing,

455 Mathematics, 401 Reading, and 1,623 Science) who participated in ACT’s National Curriculum

Survey in 2005–2006.

Figure 10: Percentages of Secondary and Postsecondary

Instructors Answering “Well” or “Very Well” to the Question

“How well do you think your state’s standards prepare

students for college-level work in your content area?”

12

high school teachers to treat all topics as important, potentially sacrificing

depth for breadth. In contrast, the postsecondary educators we surveyed

indicated that a more rigorous treatment of

fundamental

content

knowledge and skills would better prepare students for college and work.

So while a majority of secondary educators look favorably upon the

impact of state standards on student preparation, a majority of

postsecondary educators look upon this impact unfavorably. And where

high school teachers give equal emphasis to numerous content topics

and skills, college instructors believe that a more

thorough study of fewer but essential content and

skills is a better foundation for postsecondary

success. These disagreements point to a

fundamental gap between the secondary and

postsecondary education systems in this country.

If high school teachers believe they are preparing

their students for college, but these students do

not in fact possess the essential skills deemed

necessary for success in postsecondary education, then our high school

graduates are not being well served by the very institutions whose

mission is to help them succeed.

MISALIGNMENT: State Standards Do Not Define

Essential Course-Level Outcomes

Too often, state standards do not prescribe specific essential

outcomes at the course level.

What role do state standards play in helping to define the rigorous

course outcomes that students should achieve upon successful

completion of a course?

Ideally, state standards should delineate what students ought to know

and be able to do in their high school courses in each subject area so

that students have a solid foundation on which to begin the next course

in the sequence. However, only a minority of states—21 in language arts,

19 in mathematics, and 17 in science—have course-level standards

in grades 9 through 12. And even in states whose standards are

considered the best in the nation (Finn, Jr., Julian, & Petrilli, 2006),

the knowledge and skills needed for college readiness are commonly

absent from course-level standards. Table 2 provides a partial list of

these missing standards. The table was compiled by comparing course

outcomes that postsecondary educators identified as essential with the

course-level standards in three states that have been rated highly on the

quality of their state education standards.

18

In almost no state is there consensus across

the two systems on the courses students

should take in high school. . . . [I]n most

states, even students who follow all the rules

have no guarantee of meeting postsecondary

education’s course requirements.

—Somerville & Yi, 2002

19

Even a cursory examination of the highest-rated state standards that

exist today reveals that not all of the course outcomes identified as

essential by postsecondary instructors are covered in state standards

documents. More work is needed on the part of states to specify and

to disseminate to classroom teachers in

instructional terms the course outcomes that are

essential for college readiness.

MISALIGNMENT: Lack of Readiness

for High School

Many eighth-graders begin high school

without the knowledge and skills they need

to succeed there.

Preparation and readiness affect not only the transition between high

school and college but also the transition between junior high and

high school. One reason that improving college readiness is such a

challenge for high schools is because many eighth-graders enter

high school without having learned the skills needed to perform well

Table 2: Rigorous Outcomes Commonly Missing from Course-level

State Standards in English, Mathematics, and Science

Course Course Outcome

English 10 Recognize that several correct punctuation choices create

different effects (e.g., joining two independent clauses in a

variety of ways)

Use close-reading strategies (e.g., visualizing, annotating,

questioning) in order to interpret increasingly challenging texts

Read literary criticism, with assistance, to increase

comprehension of increasingly challenging literary texts

Algebra II Solve compound inequalities containing “and” and “or” and

graph the solution set

Rationalize denominators containing radicals and find the

simplest common denominator

Solve problems involving conditional probability

Biology I Explain the functions of unique plant structures, including

the cell wall, chloroplasts, and critical parts of the flower

and the seed

Describe the mode of inheritance in commonly inherited

disorders (e.g., sickle cell anemia, Down syndrome, Turner’s

syndrome, PKU)

Describe the function of enzymes, including how enzyme-

substrate specificity works, in biochemical reactions

Granting that the academic quality and

intensity of one’s high school curriculum is a

key determinant of postsecondary success,

there is no assurance that either the standards

of secondary school performance, content

coverage, or challenge of the material will

come close to the threshold demands of either

four-year or community colleges.

—Adelman, 2006

Course Course Outcome

20

in high school. In a recent ACT survey (ACT, 2007c), teachers of

entering high school students reported spending from about one-

fourth to about one-third of their time in the classroom re-teaching

skills that should have been learned prior to high school (Table 3).

When we examine the percentages of EXPLORE-

tested eighth-graders who did not meet the

EXPLORE College Readiness Benchmarks, we

also see evidence of a lack of readiness for high

school. Figure 11 gives these percentages for a

cohort of eighth-grade students who took all three

EPAS programs and graduated from high school

between 2002 and 2005.

Depending on the subject area, anywhere from

one in six to nearly eight in ten of these EXPLORE-

tested students were not on target to be ready for

college by the time they graduated from high

school. (The percentages were even lower for

African American students, Hispanic students, and

students whose annual family income is less than $30,000.) And with

the exception of Science, the percentages of these EXPLORE-tested

students who later did not meet the College Readiness Benchmarks

for the ACT are even higher (26 percent in English, 58 percent in

Mathematics, 45 percent in Reading, and 71 percent in Science).

Not surprisingly, students who are not prepared for high school are

even less likely to be prepared for college by the time they graduate

from high school. It is important that high school readiness

expectations be vertically aligned with college readiness expectations

so that students who lack foundational skills for high school work

can be identified earlier and their weaknesses remediated.

13

Based on survey responses from 502 teachers of English 9, 613 teachers of Algebra I, and

657 teachers of Biology I.

Course requirements have limitations. Just

because a course is labeled Algebra I doesn’t

always mean that it teaches the right content.

Often times, the algebra students learn in

courses with the same name doesn’t

necessar[il]y match with what colleges and

businesses expect.

—Somerville & Yi, 2002

[I]n some high schools, ‘precalculus’ on a

transcript could mean any mathematics prior to

calculus, including Algebra I.

—Adelman, 2006

Table 3: Percentage of High School Classroom Time Spent

Re-teaching Prerequisite Entry-level Skills in English,

Mathematics, and Science

13

English 9 32

Algebra I 24

Biology I 23

High School Course Percent of Time Spent Re-teaching

21

MISALIGNMENT: High School Course Grades

Are Sending Mixed Messages

Students who earn good grades in their high school courses

are led to believe they are ready for college; unfortunately,

many are not.

Many high school graduates who earn good grades in high school

courses—taken either as part of or in addition to a core curriculum—

are not necessarily ready for college either. As we saw in Figures 3

through 6, in which the highest level of ACT College Readiness

Benchmark attainment in each subject area ranges from 38 percent to

77 percent, about one-fourth to nearly two-thirds of ACT-tested

graduates who take higher-level courses beyond core have not

demonstrated a capacity to handle first-year college-level work in at

least one subject area. Ironically, however, many students are receiving

high grades in their high school courses, leading them to believe they

are ready for college. Are course grades giving students and their

parents mixed messages about college readiness?

Percent Not Meeting Benchmark

68

94

84

40

English Mathematics Reading Science

90

80

60

50

40

20

0

100

70

30

10

African

American

Hispanic White < $30,000 $30,000 to

$100,000

> $100,000 All Students

52

85

65

30

34

76

50

14

53

88

70

28

36

77

52

15

25

67

35

9

38

78

54

17

Figure 11: Percentages of EXPLORE-tested Students Not Meeting EXPLORE College

Readiness Benchmarks, by Selected Racial/Ethnic Group and Annual Family Income

(High School Graduating Classes of 2002–2005)

14

14

Based on 353,868 students who took EXPLORE between 1998 and 2001, PLAN between

2000 and 2003, and the ACT between 2002 and 2005.

22

Figure 12 compares the course grades that ACT-tested 2005 high

school graduates earned in Algebra II and Physics to their success at

meeting the ACT College Readiness Benchmarks in Mathematics

and Science, respectively.

Nearly half of ACT-tested 2005 high school graduates who earned a

grade of A or B in high school Algebra II did not meet the ACT

College Readiness Benchmark for Mathematics, and more than half

of the graduates who earned a grade of A or B in high school

Physics did not meet the ACT College Readiness Benchmark for

Science. How can 43 percent of the students who received an A or B

in Algebra II not be ready for college Algebra? Whether as a result of

grade inflation or a lack of challenging course content, it is clear that

course grades are not accurately reflecting what is needed to meet

the challenges of a college education. It is time for state standards to

define essential course outcomes so that teachers can teach to these

outcomes and student grades can more accurately reflect how well

students are learning the knowledge and skills that are necessary for

college readiness.

Percent

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

A or B C, D, or F A or B C, D, or F

53

Not Meeting Science Benchmark

Meeting Mathematics Benchmark

Meeting Science Benchmark

Not Meeting Mathematics Benchmark

47

43

57

17

82

18

83

Algebra II Physics

Figure 12: ACT College Readiness Benchmark Attainment

by Course Grade (2005 High School Graduates)

15

15

Based on 764,348 (Algebra II) and 204,139 (Physics) high school students who took the ACT

and indicated that they would graduate from high school in 2005.

23

MISALIGNMENT: Highly Qualified Teachers Are Not

Being Assigned to the Students Who Need Them Most

Teacher quality has a huge impact on high school students’

readiness for college.

Another important contributor to the rigor of the high school core

curriculum is teacher quality. According to recent research (ACT, 2007c),

one way in which teacher quality can affect student learning is that, on

average, teachers of lower-level courses are less experienced than

teachers of upper-level courses.

Another way in which students’ academic momentum can be stymied

is by assigning teachers to courses that they are not professionally

qualified to teach or not yet experienced enough to teach well. In fact,

there is evidence that these teachers are most often assigned to those

students who are furthest behind and who consequently need the most

help. A recent study demonstrates the extent of the situation (Peske

& Haycock, 2006):

▼

Despite clear evidence that student achievement is closely linked to

the degree of teaching experience their teachers possess, students

in high-poverty and high-minority schools are disproportionately

assigned to teachers who are new to the profession.

▼

Despite research showing that teachers with a major in the subject

they teach routinely elicit higher student performance than teachers

without such a major, teachers in high-poverty and high-minority

secondary schools are more likely to be lacking a major—or even

a minor—in the subject they teach.

▼

The effect of these two conditions is an increase in the disparity

between the academic achievement of students who attend high-

poverty and high-minority schools and that of students who attend

other schools.

Presley and Gong (2005) studied the relationship at Illinois high schools

between average teacher quality (a measure including both academic

qualification and degree of experience, and which is highly correlated

with other school characteristics such as percentage of students at or

below the poverty level and percentage of students who are members

of racial/ethnic minority groups) and student course-taking patterns in

mathematics in those schools. This research revealed a direct

relationship between teacher quality and students’ degree of college

readiness as determined by an index based on their ACT scores and

high school grade point averages (Figure 13).

The figure shows, for example, that students whose highest level of

mathematics course completed was Algebra II and who attended

schools with an average teacher quality index in the second quartile

(26 to 50 percent) were more ready for college than students whose

highest level of mathematics course completed was Calculus but

who attended schools with a teacher quality index of only zero to 10

percent (Peske & Haycock, 2006). Overall, lower-level mathematics

courses at schools with higher teacher quality benefit students more

than do the same courses at schools with lower teacher quality.

Teachers make a big difference in students’ chances of becoming

ready for college. Schools need to determine whether they are

assigning the right teachers to the right core courses—and to the

students who need them most.

24

Percent “More or Most” Ready for College

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Algebra II Trigonometry or

Other Advanced Math

Calculus

18

20

21

11

6

25

6

42

52

57

48

16

67

76

81

0–10% TQ

11–25% TQ

26–50% TQ

51–75% TQ

76–100% TQ

Highest Mathematics Course Completed

Figure 13: Student College Readiness by School Teacher Quality

(TQ) and Highest Mathematics Course Taken (Illinois 2001

Public High School Juniors)

Note: This figure is adapted from

The Demographics and Academics of College Readiness in Illinois

(Policy Research Report No. IERC 2005-3), by J. P. Presley and Y. Gong, 2005, Edwardsville, IL:

Illinois Education Research Council.

25

Summary

Realigning and clarifying the essential elements of our K–16

education system will help to reaffirm the rigor of the core curriculum.

In comparing secondary and postsecondary educators’ expectations,

we see radically different views about the impact of state standards

on the level of preparation of today’s students. We see postsecondary

instructors expecting more depth in student knowledge and

understanding of fewer (but essential) state standards rather than the

broad coverage of numerous state standards that high school

teachers currently believe they are obligated to teach. These

expectations should be realigned.

We also see more than half the states silent on the specific courses

that high school students should be required to take in order to

graduate. Until state graduation requirements define the right set of

courses needed for success in higher education, students will

continue taking courses that may or may not contribute to readiness.

And issues regarding teacher quality and course grades also

illustrate additional needs for realignment, not only in the assignment

of high-quality teachers to teach rigorous high school core courses,

but in grading practices that are more in line with postsecondary

expectations.

Although the focus of this report is on college readiness, there is an

equally critical parallel issue: the lack of readiness for high school.

There is no question that we will not solve the college readiness issue

without also addressing the high school readiness issue. Every day

we see evidence of the lack of readiness for high school, such as the

high proportion (as much as one-third) of ninth-grade class time that

teachers report spending on re-teaching skills that students should

have learned prior to entering high school. Aligning the expectations

for high school readiness with college readiness is a necessary

prerequisite for long-term success.

However, as is currently being demonstrated in numerous high-

performing high schools across the nation, these alignment

challenges can be overcome. Let’s examine the differences high-

performing schools have made in the college readiness of their

graduates.

26

3.

The Impact of Rigor:

Real Evidence of Progress

A study of nearly 400 U.S. high schools shows

that core courses can be made rigorous and

that rigorous content can be effectively taught

and learned.

Despite obstacles to preparing high school students for

postsecondary education and workforce training programs, there

are schools that are succeeding. These schools are currently offering

elements of a rigorous core curriculum that are resulting in improved

student achievement and improved readiness for college. If we

believe that more students will be ready for

college if they are prepared for and have the

opportunity to take a rigorous core curriculum

in high school, it may be beneficial to take a

look at those schools whose students are

doing so already.

ACT analyzed nearly 400 schools across

the United States that have recently shown

greater-than-average increases in ACT

Mathematics or Science Test scores. These

increases are all associated with substantial

numbers of students taking course sequences

that include rigorous courses in mathematics

and science (Algebra II and Chemistry,

respectively).

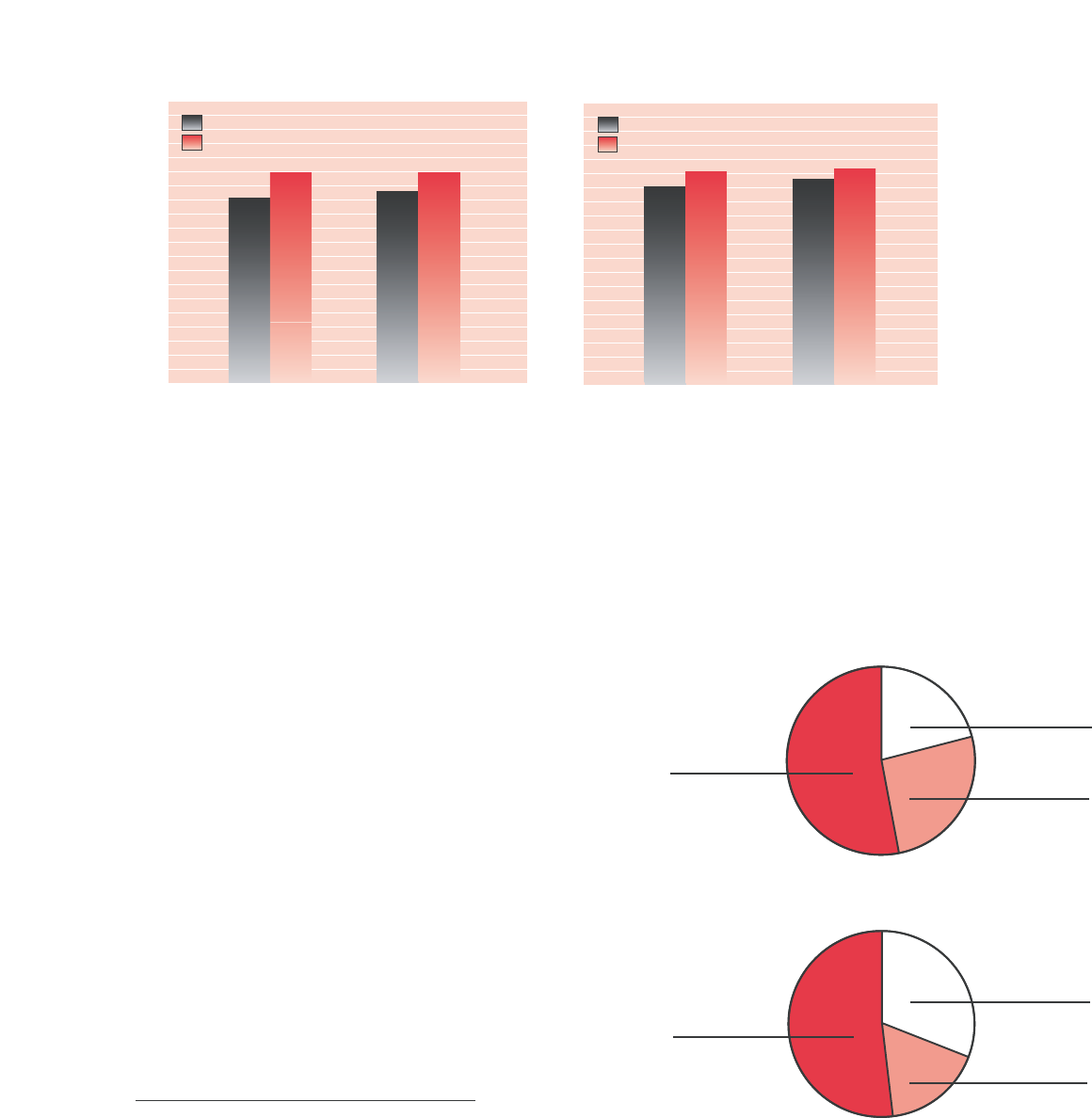

Figures 14 and 15 report the benefits to

students when they have the opportunity to

take rigorous key core courses. On average,

students from rigorous schools who took Algebra II improved their

ACT Mathematics Test scores 4.2 points (21.6 vs. 17.4), while all

ACT-tested students who took Algebra II improved their scores

2.1 points (19.1 vs. 17.0). In Science, students from rigorous schools

who took Chemistry improved their ACT Science Test scores

4.0 points (22.3 vs. 18.3), while all ACT-tested students who took

Chemistry improved their scores 2.4 points (21.0 vs. 18.6).

Beating the Odds

Do improvements in the high school core

curriculum make a difference? Evidence shows that

the answer is a definite yes. Many schools across

the U.S. are beating the odds by preparing

substantial numbers of students for college, even

in high-poverty, high-minority districts (ACT & The

Education Trust, 2004). We recently studied two

high-poverty, high-minority schools whose core

curricula strongly emphasize the importance of

college readiness. At both schools, increases were

seen in the percentage of students taking the core

curriculum and in the percentages of students

meeting the ACT College Readiness Benchmarks

(ACT, 2007b). Another high school we studied

showed substantial improvements in student

achievement after implementing a more rigorous

core curriculum (ACT, 2004b).

27

36

30

24

18

12

6

0

Average ACT Mathematics Score

Algebra I, Geometry Algebra I, Geometry,

Algebra II

All ACT-tested

Rigorous Mathematics Schools

19.1

21.6

17.0

17.4

Figure 14: Average ACT Mathematics Test Scores for Students

Taking Algebra I, Geometry, and Algebra II vs. Students Taking

Algebra I and Geometry Only (ACT-tested 2004 High School

Graduates, ACT-tested 2004 Graduates of Rigorous

Mathematics High Schools)

16

36

30

24

18

12

6

0

Average ACT Science Score

Biology Biology, Chemistry

All ACT-tested

Rigorous Science Schools

21.0

22.3

18.6

18.3

Figure 15: Average ACT Science Test Scores for Students

Taking Biology and Chemistry vs. Students Taking Biology Only

(ACT-tested 2004 High School Graduates, ACT-tested 2004

Graduates of Rigorous Science High Schools)

17

16

Based on 518,221 (All ACT-tested) and 34,193 (Rigorous Mathematics Schools) high school

students who took the ACT and indicated that they would graduate from high school in 2004.

17

Based on 715,809 (All ACT-tested) and 40,210 (Rigorous Science Schools) high school students

who took the ACT and indicated that they would graduate from high school in 2004.

28

Percent Meeting ACT Mathematics Benchmark

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

9

26

All ACT-tested

Rigorous Mathematics Schools

11

50

Less than

Algebra I,

Algebra II,

Geometry

56

84

Algebra I,

Algebra II,

Geometry

Algebra I,

Algebra II,

Geometry,

Trigonometry

Figure 16: ACT Mathematics Benchmark

Attainment, by Mathematics Course Sequence

(ACT-tested 2004 High School Graduates,

ACT-tested 2004 Graduates of Rigorous

Mathematics High Schools)

18

Biology, Chemistry

Percent Meeting ACT Science Benchmark

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

10

26

All ACT-tested

Rigorous Science Schools

8

36

Biology only Biology, Chemistry,

Physics

42

64

Figure 17: ACT Science Benchmark

Attainment, by Science Course Sequence

(ACT-tested 2004 High School Graduates,

ACT-tested 2004 Graduates of Rigorous

Science High Schools)

19

18

Based on 675,458 (All ACT-tested) and 41,445 (Rigorous Mathematics Schools) high school

students who took the ACT and indicated that they would graduate from high school in 2004.

19

Based on 967,156 (All ACT-tested) and 52,758 (Rigorous Science Schools) high school students

who took the ACT and indicated that they would graduate from high school in 2004.

Students who took Algebra II or Chemistry at rigorous high schools

also made greater gains in ACT College Readiness Benchmark

attainment than all-ACT tested students who took these courses,

improving 39 percentage points vs. 17 percentage points in

Mathematics and 28 percentage points vs. 16 percentage points in

Science (Figures 16 and 17).

Note also that students at rigorous schools who took Algebra II or

Chemistry met the associated College Readiness Benchmark in

percentages approaching those of all ACT-tested students who took

Algebra II or Chemistry plus an additional higher-level course (50

percent vs. 56 percent in mathematics; 36 percent vs. 42 percent in

science).

These figures also show the increased value added by another

mathematics course, Trigonometry, over and above Algebra II.

However, the benefits of a rigorous Algebra II course compared to the

typical Algebra II course taken by ACT-tested students are substantial.

Similarly, the benefits of a rigorous Chemistry course compared to the

typical Chemistry course taken by ACT-tested students are also

substantial, but students benefit even more when they also take a

rigorous Physics course.

29

Retention

Percent

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

66

68

All ACT-tested

Rigorous Mathematics Schools

75

75

Enrollment

Retention

Percent

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

71

73

All ACT-tested

Rigorous Science Schools

76

77

Enrollment

Figure 19: College Enrollment and

Retention for High School Graduates

Taking Chemistry (ACT-tested 2004

High School Graduates, ACT-tested

2004 Graduates of Rigorous

Science High Schools)

21

Figure 18: College Enrollment and

Retention for High School Graduates

Taking Algebra II (ACT-tested 2004

High School Graduates, ACT-tested

2004 Graduates of Rigorous

Mathematics High Schools)

20

Furthermore, students who took such critical courses as Algebra II

or Chemistry at these schools were more likely than all ACT-tested

students who took Algebra II or Chemistry to enroll in college the

fall following graduation and to return to the same institution for their

second year (Figures 18 and 19).

And when we compare the percentages of students at

rigorous high schools who met none, one to three, or all four

College Readiness Benchmarks with those of students nationally

(Figure 20), we also see that a smaller percentage of students from

these schools meet no Benchmarks, and a greater percentage

meet all four Benchmarks—evidence that these schools are

making progress at helping the majority of their students prepare

for postsecondary education.

These high schools are proving every day that core

courses can be made rigorous and that rigorous content

can be effectively taught to and learned by students.

met no

Benchmarks

31%

52%

17%

met 1 to 3

Benchmarks

met all 4

Benchmarks

Figure 20: ACT College

Readiness Benchmark

Attainment by Number

of Benchmarks Attained

(2006 High School Graduates,

2006 Students from Rigorous

High Schools)

22

met no

Benchmarks

21%

53%

26%

met 1 to 3

Benchmarks

met all 4

Benchmarks

ALL ACT-TESTED

RIGOROUS SCHOOLS

20

Based on 362,237 students nationwide and 24,052 students from rigorous mathematics

schools (Enrollment) and 239,518 students nationwide and 17,940 students from rigorous

mathematics schools (Retention) who took the ACT and indicated that they would graduate

from high school in 2004, and who, according to National Student Clearinghouse data, both