COLLEGE

READINESS

The Forgotten

Middle

Ensuring that All Students

Are on Target for College

and Career Readiness

before High School

ACT is an independent, not-for-profit organization that provides

assessment, research, information, and program management

services in the broad areas of education and workforce development.

Each year we serve millions of people in high schools, colleges,

professional associations, businesses, and government agencies,

nationally and internationally. Though designed to meet a wide array

of needs, all ACT programs and services have one guiding purpose—

helping people achieve education and workplace success.

© 2008 by ACT, Inc. All rights reserved.The ACT

®

is a registered trademark of ACT, Inc., in the U.S.A. and other countries. ACT National Curriculum

Survey

®

, EXPLORE

®

, PLAN

®

, and QualityCore

®

are registered trademarks of ACT, Inc. College Readiness Standards

™

is a trademark of ACT, Inc.

The Forgotten Middle

Ensuring that All Students Are

on Target for College and Career

Readiness before High School

Contents

Introduction: The Overwhelming Importance of Being

on Target for College and Career Readiness .......................... 1

1. A Strong Start ...................................................................... 5

2. The Benefits of Academic Behaviors in

Supporting College and Career Readiness .................. 25

3. The Nonnegotiable Knowledge and Skills

Needed by All Eighth-Grade Students .......................... 31

4. Recommendations ............................................................ 35

Appendix .................................................................................... 41

References .................................................................................. 65

i

1

Introduction:

The Overwhelming Importance

of Being on Target for College

and Career Readiness

ACT defines readiness for college as acquisition of the knowledge

and skills a student needs to enroll and succeed in credit-bearing,

first-year courses at a postsecondary institution, such as a two- or

four-year college, trade school, or technical school. Simply stated,

readiness for college means not needing to take remedial courses

in college.

Today, college readiness also means career readiness. While not

every high school graduate plans to attend college, the majority

of the fastest-growing jobs that require a high school diploma, pay

a salary above the poverty line for a family of four, and provide

opportunities for career advancement require knowledge and skills

comparable to those expected of the first-year college student

(ACT, 2006b). We must therefore educate all high school students

according to a common academic expectation, one that prepares

them for both postsecondary education and the workforce. Anything

less will not give high school graduates the foundation of academic

skills they will need to learn additional skills as their jobs change or

as they change jobs throughout their careers.

Improving the college and career readiness of all our students

will provide a better foundation of knowledge and skills to allow

future workers to adapt to the changing requirements of a more

technologically sophisticated and internationally competitive

working world.

However, the most recent results for the 2008 ACT-tested high school

graduating class are alarming: only one in five ACT-tested 2008

high school graduates are prepared for entry-level college courses

in English Composition, College Algebra, social science, and Biology,

while one in four are not prepared for college-level coursework in

any

of the four subject areas (ACT, 2008).

Current international comparisons of academic achievement show

students in the United States at a deficit compared to students in

many other nations. According to the most recent results of the

TIMSS (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study),

U.S. eighth graders rank fifteenth of forty-five countries in average

mathematics score and ninth in average science score (Gonzales

et al., 2004). The most recent results of the PISA (Programme for

International Student Assessment) rank U.S. 15-year-olds twenty-

eighth of forty countries in average mathematics performance,

eighteenth in average reading performance, and twenty-second

in average science performance (Organisation for Economic

Cooperation and Development, 2004).

Recent ACT research has investigated the multifaceted nature of

college and career readiness. We first analyzed the low level of

college and career readiness among U.S. high school graduates in

Crisis at the Core

(ACT, 2004). The critical role that high-level reading

skills play in college and career readiness in all subject areas was the

focus of

Reading Between the Lines

(ACT, 2006a). And when ACT

data showed that many high school students were still not ready for

college and career after taking a core curriculum, we examined the

need for increased rigor in the high school core curriculum as an

essential element of college and career readiness in

Rigor at Risk

(ACT, 2007b).

The Forgotten Middle

extends this research. This report examines the

specific factors that influence college and career readiness and how

these factors can have their greatest impact during a student’s

educational development. This report suggests that, in the current

educational environment, there is a critical defining point for students

in the college and career readiness process—one so important that,

if students are not on target for college and career readiness by the

time they reach this point, the impact may be nearly irreversible. We

must therefore also focus on getting more students on target for

college and career readiness by the end of eighth grade, so that they

are prepared to maximize the benefits of high school.

Our research shows that, under current conditions,

the level of

academic achievement that students attain by eighth grade has

a larger impact on their college and career readiness by the time

they graduate from high school than anything that happens

academically in high school

. This report also reveals that students’

academic readiness for college and career can be improved when

students develop behaviors in the upper elementary grades and

in middle school that are known to contribute to successful

academic performance.

The implication is clear: if we want not merely to improve but to

maximize the college and career readiness of U.S. students, we need

to intervene not only during high school but also

before

high school,

in the upper elementary grades and in middle school. This research

suggests that even improving high school course rigor may not

succeed unless we first increase the number of entering high school

students who are prepared to benefit from such rigorous courses.

2

3

This report continues to underscore that college and career readiness

is not something that suddenly “happens” when a student graduates

from high school but instead is the result of a process extending

through all the years of a student’s education. College and career

readiness is not a high school issue—it’s a K–12 issue.

Recent years have seen a heightened awareness of the importance

of early childhood education and high school as intervention points

in the educational lives of America’s

children. Less attention, it seems, has

been paid to the importance of the upper

elementary grades and middle school and

the role they must play in the preparation

of students for life after high school. The

results of our research show that the

amount of progress toward college and

career readiness that students have made

by eighth grade is crucial to their future

success. Despite the fact that students

may pass eighth-grade exit tests, too many are arriving at high school

so far behind academically that, under current conditions, they

cannot become ready for college and career regardless of the rigor

of the high school curriculum, the quality of high school instruction, or

the amount of effort they put into their coursework.

Students who leave eighth grade without the essential skills they

need to be on target for college and career readiness too often

leave high school not ready for any kind of meaningful future. If

students are to maximize the benefits of high school, a strong start

is essential. It is therefore imperative for us to turn our attention to

the students in the “Forgotten Middle” to help ensure that they are

prepared to benefit from the high school experience.

Students who fall off the college-preparatory

track early in high school tend to move ever

further from a complete college-preparatory

program as they progress through high

school.

—Finkelstein & Fong, 2008

5

1.

A Strong Start

Eighth-grade students’ academic achievement has

a larger impact on their readiness for college by

the end of high school than anything that happens

academically in today’s high schools.

Among the students in the research study discussed in this report,

fewer

than two in ten eighth graders were on target to be ready for college-level

work by the time they graduate from high school

. That is, too few eighth

graders met all four EXPLORE College Readiness Benchmarks

1

, the

minimum level of achievement that ACT has shown is necessary if

students are to be ready for college and career upon high school

graduation. This means that more than eight of ten eighth-grade students

do not have the knowledge and skills they need to enter high school and

succeed there. And not surprisingly, our research shows that students

who are not prepared for high school are less likely than other students to

be prepared for college and career by the time they graduate from high

school. So although the gates of high school are technically open to all

students, for more than 80 percent of them the door to their futures may

already be closed.

Nor is the lack of achievement by eighth grade limited to those students

traditionally considered at greatest risk of dropping out of high school.

Three out of five eighth-grade students in our study whose annual family

income was less than $30,000 and whose parents did not attend college

were not on target to be ready for college-level reading by the time they

graduated from high school. But among those eighth-graders whose

annual family income was greater than $100,000 and whose parents both

attended college, this figure was still nearly one in four.

The purpose of this study was to determine what influences college and

career readiness and what can be done to ensure that more middle

school students get off to a strong start in high school.

The Research Study

This study had two primary goals. First, we wanted to examine in greater

depth the factors that influence college and career readiness. In doing

so, we wanted to identify those factors that are the most effective

predictors of college and career readiness from middle school to high

school. Second, we wanted to examine the effect that certain steps to

improve students’ level of academic preparation would have on their

1

See the sidebar on p. 14 for more information about ACT’s College Readiness Benchmarks.

6

degree of readiness for college and career.

2

That is, what steps, if

taken by students, would have the most impact on their college and

career readiness?

The study investigated the benefits that certain factors have on

college and career readiness, given students’ background

characteristics, prior academic achievement, and high school

attended. Specifically, the analyses were designed to answer the

following questions:

▼

How important is academic achievement in grade 8 for predicting

college and career readiness in grade 11 or 12?

▼

How important are coursework and grades in high school for

predicting college and career readiness in grade 11 or 12?

▼

How much improvement in students’ college and career

readiness could we expect from their taking additional rigorous

courses and earning higher grades in high school?

▼

How does the academic progress that students make in high

school differ given their achievement level in grade 8?

The analyses were based on data from approximately 216,000

members of the high school graduating classes of 2005 and 2006

who had taken all three programs that make up the longitudinal

assessment component of ACT’s College

Readiness System (EXPLORE

®

, PLAN

®

,

and the ACT

®

test). The final data set for

2005 contained records for 98,812 students

at 4,191 high schools, while the final data

set for 2006 contained records for 117,280

students at 4,638 high schools. The 2005

data set contained 17,671 students who are

members of racial/ethnic minority groups,

while the 2006 data set contained 25,173

such students. (Racial/ethnic minority

students were those who identified

themselves as one of the following: African

American, American Indian, Hispanic,

Multiracial, or Other.)

The 2006 data were used to confirm,

through cross-validation, the results of the

2005 analyses. Because these data mostly

pertain to students who were considering

attending college immediately after high

2

For detailed information about the study methodology, please see the Appendix.

Percentage of High School Classroom Time

Spent Re-teaching Prerequisite Entry-level

Skills in English, Mathematics, and Science*

Lack of readiness to benefit from high school affects

not just the academic development of students but

also how instructional time is spent in the classroom.

Teachers of entering high school students responding

to an ACT survey in spring 2006 said that they spend

from about one-fourth to about one-third of their time in

the classroom re-teaching skills that should have been

learned prior to high school (ACT, 2007b).

Percent of Time

High School Course Spent Re-teaching

English 9 32

Algebra I 24

Biology I 23

* Based on survey responses from 502 teachers of English 9,

613 teachers of Algebra I, and 657 teachers of Biology I.

7

school, they may not be representative of all high school students.

For example, our sample contained a larger percentage of female

students, and smaller percentages of African American and Hispanic

students, than did the U.S. high school graduating classes in the

years under study. See the Appendix for more details.

Eighth-Grade Academic Achievement Is the

Best Predictor of College and Career Readiness

by High School Graduation

We first constructed predictive models to examine the relative

strengths of six classes of predictor variables (hereafter referred to

as “factors”) in influencing students’ college and career readiness,

as defined by their performance on the ACT:

3

▼

Background characteristics—gender,

race/ethnicity, parent educational level, annual

family income, primary language spoken at home

▼

Eighth-grade achievement—EXPLORE test

scores in relevant subject areas

▼

Standard high school coursework—highest level

of non-advanced, non-honors courses taken in

relevant subject areas

▼

Advanced/honors high school coursework—

accelerated, honors, or Advanced Placement

courses in relevant subject areas

▼

High school grade point average—self-reported

grade average for courses taken in relevant

subject areas

▼

Student testing behaviors—students’ age and

grade level at time of taking the ACT, whether

students retook the ACT, whether students

provided updated coursework and grade

information if retesting. Because student testing

behaviors are the result of student decisions about

whether, when, and how often to take the ACT,

these behaviors reflect traits such as motivation

and students’ self-perceptions about their

academic abilities.

ACT’s College Readiness System

ACT’s College Readiness System is

intended to help states prepare every

student for college and career. The

system is a fully aligned, research-based

solution. (See the Appendix for more

information about the College

Readiness System.)

The longitudinal assessment component

of the system consists of three

aligned programs:

▼

EXPLORE, for students in grades 8

and 9, provides baseline information

on the academic preparation of

students that can be used to plan

high school coursework.

▼

PLAN, for students in grade 10,

provides a midpoint review of

students’ progress toward their

education and career goals while

there is still time to make necessary

interventions.

▼

The ACT, for students in grades 11

and 12, measures students’ academic

readiness to make successful

transitions to college and work after

high school.

3

Because we anticipated that the predictive relationships might differ among high schools, we constructed

hierarchical linear models in which regression weights relating predictor variables to outcome variables can

vary among high schools.

While the factors we examined are not exhaustive of all the factors

that could influence students’ college and career readiness, they are

intended to encompass the major influences on college and career

readiness.

As shown in Figures 1a through 1d, eighth-grade achievement

(measured by the four EXPLORE scores in English, Mathematics,

Reading, and Science) displays a stronger relationship with eleventh-

or twelfth-grade ACT scores, and therefore with college and career

readiness, than does any other factor—more than students’ family

background, high school coursework, or high school grade point

average. The predictive power of eighth-grade academic

achievement ranged from more than two-and-a-half times as strong

as the next strongest factor (in English) to three-and-a-half times the

strength of the next strongest factor (in Science).

Compared to eighth-grade academic achievement, the predictive

power of each of the other factors we examined was small and in

some cases negligible. The weakest factor in English and Reading

was standard coursework (highest level of non-advanced, non-honors

courses taken), while in Mathematics and Science the weakest factor

was advanced/honors coursework (whether students had taken

accelerated, honors, or Advanced Placement courses).

We found similar results for racial/ethnic minority students, presented

in Figures 2a through 2d (p. 10). The results for racial/ethnic minority

students were nearly identical to those for the total group of students

in each subject area: once again, eighth-grade academic

achievement had by far the strongest relationship with college and

career readiness. In fact, while the predictive power of the other

factors was again small or negligible, the predictive power of eighth-

grade achievement was somewhat greater for racial/ethnic minority

students than that seen for the total group.

Similar results to those for the total group were also obtained when

the data were analyzed by students’ annual family income level

(less than $30,000, between $30,000 and $100,000, and more

than $100,000).

8

Figure 1c: Reading

Eighth-grade

achievement

60%

Student testing

behaviors

18%

High school grade

point average

9%

Advanced/honors

coursework

8%

Background

characteristics

5%

(Standard

coursework

0%)

9

Figure 1b: Mathematics

Figure 1a: English

Figure 1d: Science

Eighth-grade

achievement

54%

Student testing

behaviors

21%

High school grade

point average

9%

Advanced/honors

coursework

8%

Background

characteristics

7%

Standard

coursework

1%

Eighth-grade

achievement

42%

Student testing

behaviors

10%

High school grade

point average

12%

Advanced/honors

coursework

9%

Background

characteristics

15%

Standard

coursework

12%

Eighth-grade

achievement

49%

Student testing

behaviors

14%

High school grade

point average

9%

Advanced/honors

coursework

6%

Background

characteristics

14%

Standard

coursework

8%

Figure 1: Relative Magnitude of Effect in Predicting Eleventh/Twelfth-Grade

College and Career Readiness (All Students)

10

Figure 2b: Mathematics

Figure 2a: English

4

Figure 2c: Reading

4

Figure 2d: Science

Eighth-grade

achievement

56%

Student testing

behaviors

22%

High school grade

point average

8%

Advanced/honors

coursework

6%

Background

characteristics

4%

Standard

coursework

1%

Eighth-grade

achievement

65%

Student testing

behaviors

17%

High school grade

point average

10%

Advanced/honors

coursework

6%

Background

characteristics

3%

(Standard

coursework

0%)

Eighth-grade

achievement

43%

Student testing

behaviors 8%

High school grade

point average

14%

Advanced/honors

coursework

10%

Background

characteristics

13%

Standard

coursework

12%

Eighth-grade

achievement

52%

Student testing

behaviors

15%

High school grade

point average

11%

Advanced/honors

coursework

5%

Background

characteristics

10%

Standard

coursework

7%

4

The percentages in Figures 2a and 2c do not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Figure 2: Relative Magnitude of Effect in Predicting Eleventh/Twelfth-Grade

College and Career Readiness (Racial/Ethnic Minority Students)

Improvement in Eighth-Grade Academic Achievement

and Being on Target for College and Career Readiness

in Eighth Grade Are More Beneficial Than Any

High School-Level Academic Enhancement

Next, we examined the impact of a variety of steps students could take to

improve their college and career readiness during high school, including:

▼

Maintaining a B average in relevant standard high school courses

▼

Earning higher grades in relevant standard high school courses

▼

Taking a core curriculum in relevant subject areas in high school

(for Mathematics and Science only)

5

▼

Taking additional standard courses in relevant subject areas in

high school (for Mathematics and Science only)

▼

Taking advanced or honors courses in relevant subject areas in high

school (if not already taken)

▼

Meeting EXPLORE College Readiness Benchmarks in all four

subject areas in eighth grade (see sidebar, p. 14)

▼

Increasing EXPLORE scores 2 points in each subject area in

eighth grade

We did not study the impact of targeted high school interventions with

students identified as having academic difficulty (e.g., remedial

coursework); instead, we focused on voluntary steps that are currently

available to high school students to improve their college and career

readiness themselves.

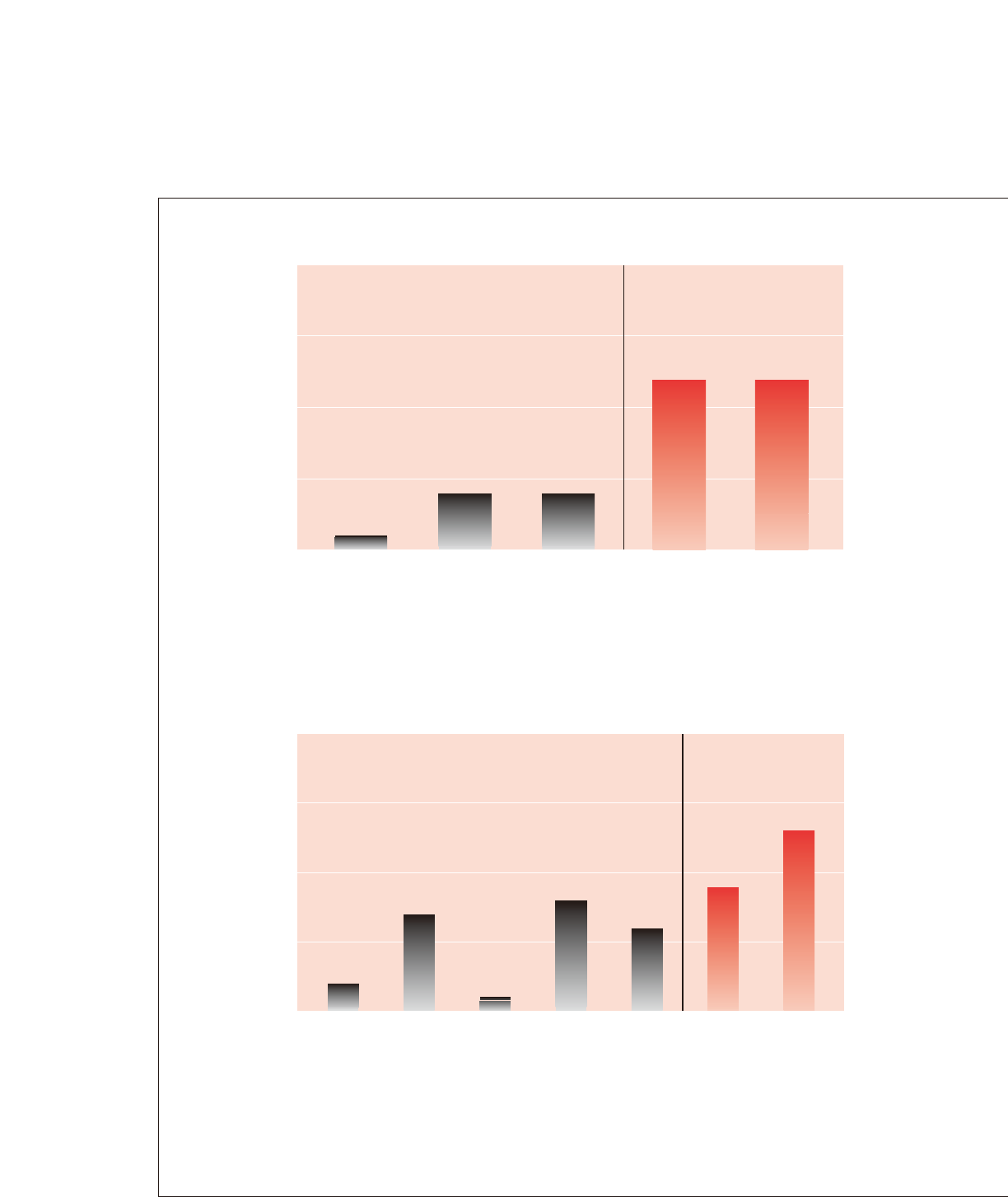

Figures 3a through 3d show the additional percentages of students who

would meet the ACT College Readiness Benchmarks in each subject area

if the students took each of the seven steps independently of the others.

As the figures show, being on target for college and career readiness in

the eighth grade and improving the college and career readiness skills

that students possess by grade 8 have the most dramatic impact on

high school graduates’ ultimate level of college and career readiness.

This impact is much larger than that associated with any single high

school-level enhancement. These results, however, should not be

interpreted to mean that high school-level enhancements have little or

no benefit for students. Rather, of the factors studied, modest increases in

11

5

The core curriculum in mathematics was defined as Algebra I, Geometry, and Algebra II; in science,

the core curriculum was defined as Biology and Chemistry. For English and Reading, there was not

enough variation in students’ coursework patterns to permit meaningful enhancements with regard to

taking either the core curriculum or additional standard courses (see next bullet). This is likely because

high schools typically require all students to take the same English courses and many of the same social

studies courses.

20

15

10

5

0

1

Increase

standard

English and

social studies

course grades

one letter

Maintain

B average in

standard English

and social studies

courses

Percentage-Point Increase in ACT English

Benchmark Attainment

Take

advanced/honors

English and

social studies

courses

Meet all four

EXPLORE

Benchmarks

Increase

all four

EXPLORE

scores 2 points

4 4

12 12

12

Figure 3: Increases in ACT College Readiness Benchmark

Attainment Associated with Various Academic Interventions

(All Students)

Figure 3b: Mathematics

20

15

10

5

0

1

Maintain

B average in

standard

mathematics

and science

courses

Percentage-Point Increase in ACT Mathematics

Benchmark Attainment

2

7

8

9

13

6

Increase

standard

mathematics

and science

course

grades

one letter

Take core

curriculum in

mathematics

and science

Take

additional

standard

mathematics

and science

courses

Take

advanced/

honors

mathematics

and science

courses

Meet all four

EXPLORE

Benchmarks

Increase

all four

EXPLORE

scores

2 points

Figure 3a: English

13

Figure 3c: Reading

Figure 3d: Science

20

15

10

5

0

0

Maintain

B average in

standard

mathematics

and science

courses

Percentage-Point Increase in ACT Science

Benchmark Attainment

0

3

3

7

13

2

Increase

standard

mathematics

and science

course

grades

one letter

Take core

curriculum in

mathematics

and science

Take

additional

standard

mathematics

and science

courses

Take

advanced/

honors

mathematics

and science

courses

Meet all four

EXPLORE

Benchmarks

Increase

all four

EXPLORE

scores

2 points

20

15

10

5

0

1

Increase

standard

English and

social studies

course grades

one letter

Maintain

B average in

standard English

and social studies

courses

Percentage-Point Increase in ACT Reading

Benchmark Attainment

Take

advanced/honors

English and

social studies

courses

Meet all four

EXPLORE

Benchmarks

Increase

all four

EXPLORE

scores 2 points

4

5

12

16

students’ level of academic achievement by the eighth grade and

being on target for college and career readiness in the eighth grade

had the greatest relative impact on college and career readiness in

grade 11 or 12.

Figures 3a through 3d show that the increases in Benchmark

attainment associated with higher EXPLORE scores and meeting

all four EXPLORE College Readiness Benchmarks were up to three

times the size of the largest increase associated with any single

high school-level academic enhancement. The level of academic

achievement that students reach in all four subject areas by the

eighth grade is a crucial element in determining whether they will

be ready for college and career by the end of high school.

In English and Reading, maintaining a B average in relevant standard

high school courses had the least impact on improving students’

college and career readiness. In Mathematics, taking a core

curriculum in relevant subject areas had the least impact. In Science,

maintaining a B average in relevant standard high school courses

and taking a core curriculum in relevant subject areas had no clear

impact. Consistent with previous ACT research (2004, 2007b), the

small impact of taking a core curriculum in mathematics and science

suggests that, as currently constituted, core courses at far too many

U.S. high schools are not sufficiently rigorous to prepare students for

college and career.

14

ACT’s College Readiness Benchmarks

The ACT College Readiness Benchmarks are scores on the ACT

test that represent the level of achievement required for students

to have a high probability of success in selected credit-bearing,

first-year college courses.

ACT has also established College Readiness Benchmarks for

EXPLORE and PLAN. These scores indicate whether students,

based on their performance on EXPLORE (grade 8) or PLAN

(grade 10), are on target to be ready for first-year college-level

work when they graduate from high school.

Test EXPLORE PLAN The ACT

English 13 15 18

Mathematics 17 19 22

Reading 15 17 21

Science 20 21 24

Table 1: Strongest and Weakest Impact of Various Academic

Interventions on ACT College Readiness Benchmark Attainment

Strongest Impact Weakest Impact

Subject Area

Increase all EXPLORE

scores 2 points

Meet all four EXPLORE

Benchmarks

Maintain B average in

standard English and social

studies courses

Increase all EXPLORE

scores 2 points

Meet all four EXPLORE

Benchmarks

Maintain B average in

standard mathematics and

science courses

Take core curriculum in

mathematics and science

English

Mathematics

Increase all EXPLORE

scores 2 points

Meet all four EXPLORE

Benchmarks

Maintain B average in

standard English and social

studies courses

Increase all EXPLORE

scores 2 points

Meet all four EXPLORE

Benchmarks

Maintain B average in

standard mathematics

and science courses

Take core curriculum in

mathematics and science

Reading

Science

15

Similar results were also seen for racial/ethnic minority students. These

results are presented in Figures 4a through 4d.

These results are summarized in Table 1.

16

20

15

10

5

0

2

Increase

standard

English and

social studies

course grades

one letter

Maintain

B average in

standard English

and social studies

courses

Percentage-Point Increase in ACT English

Benchmark Attainment

Take

advanced/honors

English and

social studies

courses

Meet all four

EXPLORE

Benchmarks

Increase

all four

EXPLORE

scores 2 points

4 4

20

17

25

Figure 4b: Mathematics

20

15

10

5

0

0

Maintain

B average in

standard

mathematics

and science

courses

Percentage-Point Increase in ACT Mathematics

Benchmark Attainment

2

5

5

8

10

3

Increase

standard

mathematics

and science

course

grades

one letter

Take core

curriculum in

mathematics

and science

Take

additional

standard

mathematics

and science

courses

Take

advanced/

honors

mathematics

and science

courses

Meet all four

EXPLORE

Benchmarks

Increase

all four

EXPLORE

scores

2 points

Figure 4a: English

Figure 4: Increases in ACT College Readiness Benchmark

Attainment Associated with Various Academic Interventions

(Racial/Ethnic Minority Students)

17

Figure 4d: Science

Figure 4c: Reading

20

15

10

5

0

1

Increase

standard

English and

social studies

course grades

one letter

Maintain

B average in

standard English

and social studies

courses

Percentage-Point Increase in ACT Reading

Benchmark Attainment

Take

advanced/honors

English and

social studies

courses

Meet all four

EXPLORE

Benchmarks

Increase

all four

EXPLORE

scores 2 points

3

2

16 16

20

15

10

5

0

0

Maintain

B average in

standard

mathematics

and science

courses

Percentage-Point Increase in ACT Science

Benchmark Attainment

0

2

2

6

8

1

Increase

standard

mathematics

and science

course

grades

one letter

Take core

curriculum in

mathematics

and science

Take

additional

standard

mathematics

and science

courses

Take

advanced/

honors

mathematics

and science

courses

Meet all four

EXPLORE

Benchmarks

Increase

all four

EXPLORE

scores

2 points

We also saw comparable results for students at all annual family income

levels.

Overall, the results suggest that getting more eighth-grade students on

target for college and career readiness and increasing their achievement

have the greatest impact across all four subject areas—especially in

English and Reading. This is particularly noteworthy given ACT research

showing that student readiness for college-level reading has a strong

association with their readiness for college in other subject areas (see

sidebar). Earning higher grades in standard courses and taking

advanced or honors courses provide modest benefits in English,

Reading, and Science, and slightly greater benefits in Mathematics.

It is clear from these results that major improvements in academic skills

need to occur

before

grade 8.

While our study examined the effect of each enhancement separately,

several of these enhancements

together

would likely result in a larger

increase. But the feasibility and practicality of students’ accomplishing

multiple enhancements simultaneously—particularly if they start with

below-average prior achievement—have yet to be determined.

Students who are on target in eighth and ninth

grade to be ready for college-level reading are

substantially more likely to be on target to be ready

for college in English, mathematics, and science.

Because reading is likely a strong intervening factor

in academic areas across the curriculum, we

examined the English, mathematics, and science

achievement of eighth-grade students in 2008 who

met and did not meet the EXPLORE College

Readiness Benchmark in Reading. The figure

below shows, for students who met and did not

meet the Reading Benchmark, the percentage of

students meeting the EXPLORE College Readiness

Benchmarks in English, Mathematics, and Science.

Of those students in 2008 who met the EXPLORE

Reading Benchmark:

▼

92 percent also met the EXPLORE

English Benchmark;

▼

65 percent also met the EXPLORE

Mathematics Benchmark; and

▼

31 percent also met the EXPLORE

Science Benchmark.

Of those students in 2008 who did NOT meet

the EXPLORE Reading Benchmark:

▼

only 38 percent also met the EXPLORE

English Benchmark;

▼

only 14 percent also met the EXPLORE

Mathematics Benchmark; and

▼

only 1 percent also met the EXPLORE

Science Benchmark.

Percent

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Met EXPLORE Reading Benchmark

Did Not Meet EXPLORE Reading Benchmark

92

38

65

14

English Mathematics Science

31

EXPLORE College Readiness Benchmark

1

18

Reading Achievement and Achievement in Other Academic Areas

19

The results show that when students’ skills are improved by the

end of middle school, the results by the end of high school can

be impressive. For example, the percentage of students in our

sample who met all four ACT College Readiness Benchmarks

after taking EXPLORE and PLAN was 17 percent. Our research

indicates that if these students had scored just 2 points higher on

each EXPLORE subject test, the percentage who would meet all

four ACT Benchmarks would rise 11 percentage points, to

28 percent—a 43-percent increase over their current level of

ACT Benchmark attainment.

What’s more, improving middle school students’ achievement by

just 2 score points in each subject area would have a cascading

effect over the succeeding levels of education. The 13-point increase

in the percentage of high school graduates ready for college-level

mathematics (see Figure 5b) should later produce about 25,000

additional degree completers at two- and four-year colleges (and

about 25,000 fewer college dropouts) each year in the United States.

6

Extrapolating from U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates (U.S.

Department of Labor, 2007), these new degree completers would

enjoy an increase of close to $500 million per year in their combined

average salary (i.e., about $20,000 per person) and a drop in their

average unemployment rate of 2 percentage points.

Similarly, the 16-point increase in the percentage ready for college-

level reading (see Figure 5c) would result in about 20,000 additional

college-degree completers each year in the United States.

Our results clearly show that raising eighth-grade students’ level of

academic achievement and helping them get on target for college

and career readiness are the most powerful steps that can be taken

to improve these students’ college and career readiness by the time

they graduate from high school.

Being on Target for College and Career Readiness

in Eighth Grade Puts Students on a Trajectory

for Success

Because the data for the sample used in this study ranged from the

eighth to the twelfth grade for the same group of students, we were

able to examine the rate of growth in students’ achievement through

high school. We examined growth among three categories of

students in our sample: those who were on target for college and

6

Calculations based on estimates in Noble and Radunzel (2007), Table 7. This table compares

college-degree completion rates during the 1998–2003 period for students who met the ACT College

Readiness Benchmarks in Mathematics and Reading and those who did not. Increases in Benchmark

attainment yielded by the present study were multiplied by the Noble and Radunzel completion rates

to estimate the additional numbers of associate’s degree completers at two-year colleges and

bachelor’s degree completers at four-year colleges that would result from increasing EXPLORE scores

2 points.

career readiness in the eighth grade, those who just missed being

on target for college and career readiness (i.e., by 2 or fewer score

points), and those who were more substantially off target (i.e., by

more than 2 score points).

Figures 5a through 5e present, for each of the four subject tests and

the composite score (which is computed as the average of the four

subject-area scores), the average EXPLORE, PLAN, and ACT scores

for these three categories of students in our 2005 sample. Figures 5a

through 5d show that, on average,

only the group of students who

were on target for college and career readiness by the eighth grade

were ultimately ready for college and career by the eleventh or twelfth

grade

. Even the group of students who just missed being on target in

eighth grade fell short, on average, of becoming ready for college

and career by the time they reached grade 11 or 12. This was true in

each of the four subject areas.

English Test Score

EXPLORE

36

1

31

26

21

16

11

6

PLAN ACT

EXPLORE

English

Benchmark:

13

ACT English

Benchmark:

18

22

20

17

12

9

15

13

15

13

21

16

19

Met/exceeded EXPLORE Benchmark

More than 2 points from EXPLORE Benchmark

Entire sample

Within 2 points of EXPLORE Benchmark

Mathematics Test Score

EXPLORE

36

1

31

26

21

16

11

6

PLAN ACT

EXPLORE

Mathematics

Benchmark:

17

ACT

Mathematics

Benchmark:

22

24

21

19

15

12

17

15

19

16

19

20

16

Met/exceeded EXPLORE Benchmark

More than 2 points from EXPLORE Benchmark

Entire sample

Within 2 points of EXPLORE Benchmark

20

Figure 5a: English

Figure 5: Average Scores for 2005 Sample

(All Students)

Figure 5b: Mathematics

21

Reading Test Score

EXPLORE

36

1

31

26

21

16

11

6

PLAN ACT

EXPLORE

Reading

Benchmark:

15

ACT Reading

Benchmark:

21

24

20

18

14

11

16

14

18

16

21

18

16

Met/exceeded EXPLORE Benchmark

More than 2 points from EXPLORE Benchmark

Entire sample

Within 2 points of EXPLORE Benchmark

Figure 5d: Science

Science Test Score

EXPLORE

36

1

31

26

21

16

11

6

PLAN ACT

EXPLORE

Science

Benchmark:

20

ACT Science

Benchmark:

24

25

22

21

18

15

20

17

22

18

17

21

19

Met/exceeded EXPLORE Benchmark

More than 2 points from EXPLORE Benchmark

Entire sample

Within 2 points of EXPLORE Benchmark

Composite Score

EXPLORE

36

1

31

26

21

16

11

6

PLAN ACT

27

23

21

18

15

20

17

23

18

17

21

19

Met/exceeded all four EXPLORE Benchmarks

More than 2 points from each

EXPLORE Benchmark

Entire sample

Within 2 points of each EXPLORE Benchmark

Figure 5c: Reading

Figure 5e: Composite

Virtually identical results were obtained for a nationally representative

sample of students who had taken the tests across a number of

years, indicating that the results are not specific to the 2005 and 2006

samples.

Note also that in all subject areas the score increases for the group

of students who were on target in eighth grade were steeper than

those for the other two groups, especially from PLAN to the ACT.

This suggests that the rate of growth in high school is accelerated for

students who were on target in eighth grade compared to students

who were not on target, particularly during grades 11 and 12.

We conducted the same analysis for racial/ethnic minority students.

The results are shown in Figures 6a through 6e. Although in some

cases the average scores for these students were slightly lower than

those for the total group, the same trends held.

English Test Score

EXPLORE

36

1

31

26

21

16

11

6

PLAN ACT

EXPLORE

English

Benchmark:

13

ACT English

Benchmark:

18

20

18

16

11

9

14

12

15

12

14

16

18

Met/exceeded EXPLORE Benchmark

More than 2 points from EXPLORE Benchmark

Entire sample

Within 2 points of EXPLORE Benchmark

Mathematics Test Score

EXPLORE

36

1

31

26

21

16

11

6

PLAN ACT

EXPLORE

Mathematics

Benchmark:

17

ACT

Mathematics

Benchmark:

22

23

20

19

15

12

17

14

18

16

Met/exceeded EXPLORE Benchmark

More than 2 points from EXPLORE Benchmark

Entire sample

Within 2 points of EXPLORE Benchmark

Figure 6: Average Scores for 2005 Sample

(Racial/Ethnic Minority Students)

22

Figure 6a: English

Figure 6b: Mathematics

Reading Test Score

EXPLORE

36

1

31

26

21

16

11

6

PLAN

ACT

EXPLORE

Reading

Benchmark:

15

ACT Reading

Benchmark:

21

22

19

18

13

11

16

13

17

15

19

14

Met/exceeded EXPLORE Benchmark

More than 2 points from EXPLORE Benchmark

Entire sample

Within 2 points of EXPLORE Benchmark

16

Science Test Score

EXPLORE

36

1

31

26

21

16

11

6

PLAN ACT

EXPLORE

Science

Benchmark:

20

ACT Science

Benchmark:

24

24

22

21

18

15

19

17

21

17

16

19

Met/exceeded EXPLORE Benchmark

More than 2 points from EXPLORE Benchmark

Entire sample

Within 2 points of EXPLORE Benchmark

18

Composite Score

EXPLORE

36

1

31

26

21

16

11

6

PLAN ACT

26

23

20

18

14

19

16

22

17

15

18

17

Met/exceeded all four EXPLORE Benchmarks

More than 2 points from each

EXPLORE Benchmark

Entire sample

Within 2 points of each EXPLORE Benchmark

23

Figure 6e: Composite

Figure 6c: Reading

Figure 6d: Science

24

Once again, in each of the four subject areas, only the group that was

on target for college and career readiness by the eighth grade went

on to be ready for college and career by the eleventh or twelfth grade.

If students are on target to be ready for college and career in the

eighth grade, their chances of being ready for college and career by

high school graduation are substantially increased.

Again, similar results were seen by annual family income level.

These results show the critical importance of being on target for

college and career readiness in eighth grade: regardless of

race/ethnicity or income, those who are on target are on a trajectory

of success that enables them to be ready for college and career by

high school graduation, while those who are not on target are much

less likely to eventually be ready for college and career.

Summary

In all four subject areas, eighth-grade academic achievement (as

measured by EXPLORE) and meeting all four EXPLORE College

Readiness Benchmarks have a stronger relationship with college

and career readiness (as measured by performance on the ACT

in grade 11 or 12) than factors such as students’ background

characteristics, the courses they take in high school, or the grades

they earn in those courses.

Under current conditions, increasing eighth-grade students’ academic

achievement (as represented by increasing their EXPLORE scores just

2 points on each subject test) and helping them get on target for

college and career readiness would have a substantially larger impact

on students’ readiness for college than any single academic

enhancement undertaken

during

high school, whether it be taking a

minimum core curriculum, increasing course grades or maintaining a

B average, or taking additional standard or advanced/honors courses.

Such increases in students’ academic skills by grade 8 would

continue to pay benefits beyond high school, by increasing the number

of students graduating from college and decreasing the number of

college dropouts. And just imagine the impact if student achievement

could be increased by an even larger amount than the modest

increases examined in this study.

Nevertheless, academic achievement is only part of what students

need in order to be successful in high school. High school students

also need to demonstrate behaviors that contribute to their ability to

perform well academically. The next chapter will show that if students

are able to develop these behaviors by the end of middle school, they

will increase their likelihood of being ready for college and career by

the end of high school.

25

2.

The Benefits of

Academic Behaviors

in Supporting College

and Career Readiness

Improving certain behaviors of middle-school

students—particularly academic discipline—

can help improve students’ readiness for college

and career.

Academic achievement is typically defined as the cognitive

knowledge, skills, and abilities that are measured by achievement

tests such as EXPLORE and the ACT. Our data show that academic

achievement—especially the level of achievement students have

attained by the eighth grade—plays a substantial role in student

readiness for college and career.

Research (e.g., Schweinhart, Barnes,

& Weikart, 1993; Reynolds et al., 2007) has

shown that academic achievement can be

influenced by children’s health needs and

by their psychosocial (that is, psychological

and social) development. Academically

related psychosocial behaviors such as

motivation, social connectedness, school

attendance, obedience of rules, and

avoidance of drugs are important

predictors of academic success in

middle school and high school (Kaufman

& Bradbury, 1992; Rumberger, 1995; Worrell & Hale, 2001; Jones

& Byrnes, 2006). Other beneficial academic behaviors include

academic discipline (i.e., good work and study habits, such as

consistently completing homework), orderly conduct, and positive

relationships with school personnel (Casillas, Robbins,

& Schmeiser, 2007).

The decision to drop out is rarely the result

of a single life event; in fact, many students

exhibit academic warning signs years before

they leave high school. ...Students who

dropped out usually had received a failing

grade in core courses (especially in math or

English), earned a low grade point average

(GPA), or scored low on achievement tests.

—Pinkus, 2008

Recognizing that college and career readiness encompasses a variety

of factors, we studied the impact that academic behaviors might have

on improving student academic achievement. If educators could

intervene effectively with students whose academic behaviors signal a

high risk of academic failure, could these students be set on a course

by which they could eventually benefit from a rigorous curriculum in

high school?

In this phase of our research, ACT collected data from students

at twenty-four U.S. middle schools to examine the role that ten

academically related psychosocial factors play in predicting two

important indicators of students’ future academic success: course

failure in grade 8 and high school grade point average in grade 9.

The ten factors were: academic discipline, commitment, family

attitude, family involvement, optimism, orderly conduct, relationships

with school personnel, safety of the school environment, steadiness,

and thinking before acting. We studied

2,928 students in the course-failure analysis

and 2,146 students in the grade point

average analysis.

Academic Discipline Accounts

for the Majority of the Predictive

Strength of Academic Behaviors

Failing a course is a strong predictor of

dropping out of high school (Allensworth

& Easton, 2005), and our findings suggest that

two of the ten academic behaviors we studied

had a substantial impact on whether a course

was failed in grade 8: academic discipline and

orderly conduct.

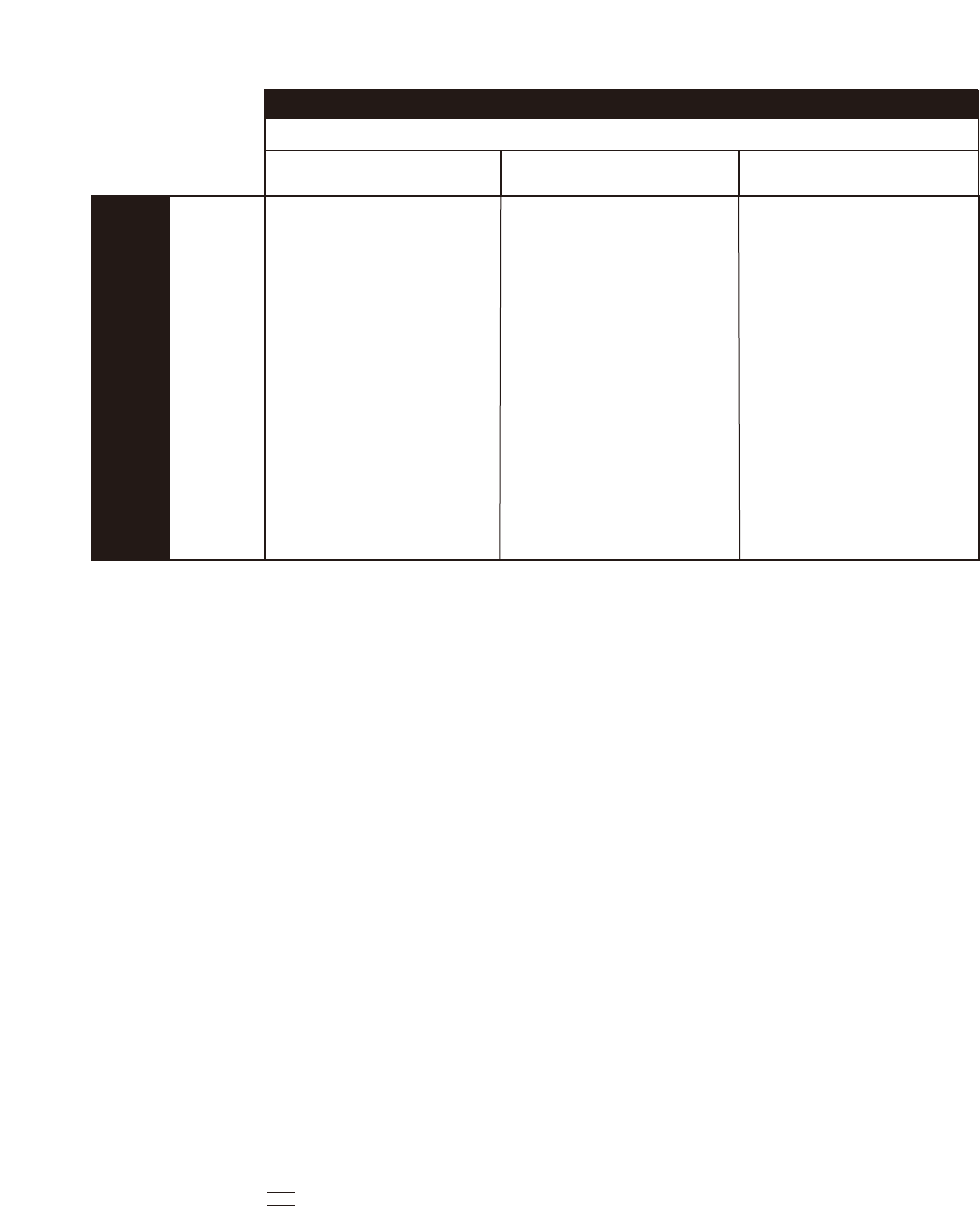

As shown in Figure 7a, eighth-grade academic

achievement (as measured by EXPLORE

Composite score) had the greatest influence on

eighth-grade course failure, accounting for

65 percent of the explained variance, vs.

35 percent for the academic behaviors.

Figure 7b gives the relative strengths of the

two specific academic behaviors for predicting

eighth-grade course failure. Academic

discipline alone accounted for 61 percent of the

predictive strength of the academic behaviors

and therefore proved to be the strongest

predictor among all the behaviors studied.

Academic Discipline

Academic discipline is defined as the skill

component of motivation, such as the degree to

which a student is hardworking and conscientious.

It is evidenced by the amount of effort invested into

completing schoolwork and engaging in learning

new material.

Academic discipline features three primary

components, all of which support the various

learning processes and goals that ultimately lead

to academic success:

▼

Planning and Organization—thinking about

necessary steps and devising plans for

achieving objectives. Students skilled in this

area have a strong sense of time, organization,

and prioritization and use strategic skills to aid

in learning new information.

▼

Follow-through and Action—engaging in

behaviors according to previously set plans

and remaining engaged in a task until the

objective is accomplished in a timely fashion.

Students skilled in this area are able to assess

their own progress throughout a task and act

accordingly based on this assessment.

▼

Sustained Effort—maintaining focus on longer-

term goals and working to achieve individual

elements of these goals. Students skilled in this

area persist despite challenges, exhibit on-task

behavior, and are able to manage distractions

in order to achieve a goal.

26

27

In addition to the effect of academic behaviors on eighth-grade course

failure, we looked at their effect on grade point average in ninth grade,

an accepted predictor of future academic performance. We found that

three of the ten academic behaviors we studied had impact on grade

point average in ninth grade: academic discipline, orderly conduct, and

having positive relationships with school personnel.

As shown in Figure 8a, eighth-grade academic achievement (as

measured by EXPLORE Composite score) had the greatest influence

on predicting grade point average in ninth grade, accounting for

53 percent of the explained variance, vs. 47 percent for the

academic behaviors.

Figure 7a: Relative Strength of Academic

Achievement and Academic Behaviors

Figure 7b: Relative Strength of

Different Academic Behaviors

EXPLORE

Composite

65%

Academic

Behaviors

35%

Academic

Discipline

61%

Orderly

Conduct

39%

7

Seventeen percent of the variation in eighth-grade course failure was explained by the predictor

variables. The percentages in figures 7a and 7b sum to 100 because they are reported in terms of

explained variance only. (This is also true of figures 8a and 8b, where 42 percent of the variation in

grade point average in ninth grade was explained by the predictor variables.)

EXPLORE

Composite

53%

Academic

Behaviors

47%

Academic

Discipline

53%

Orderly

Conduct

32%

Relationships

with School

Personnel

15%

Figure 8a: Relative Strength of Academic

Achievement and Academic Behaviors

Figure 8b: Relative Strength of

Different Academic Behaviors

Figure 7: Predicting Failed Course in Eighth Grade

7

Figure 8: Predicting Grade Point Average in Ninth Grade

Figure 8b gives the relative strengths of the three specific academic

behaviors for predicting grade point average in ninth grade. Once

again, academic discipline alone accounted for the majority of the

predictive strength of the academic behaviors (53 percent).

Academic Achievement and Academic

Behaviors Combined are the Best Predictor

of Academic Difficulty

Previous studies have suggested that early remediation of

deficiencies in academic behaviors can be an effective strategy for

improving later academic achievement (Dadds & Fraser, 2003; Dunn

& Mezzich, 2007; Jones & Byrnes, 2006; Kaufman & Bradbury, 1992;

Patterson, Reid, & Eddy, 2002; Rumberger, 1995; Worrell & Hale,

2001). What’s more, the behaviors associated with academic success

serve as useful indicators pointing educators toward needed

interventions and guiding the nature of those interventions. The

combination of academic achievement and academic behaviors is

the best predictor for identifying students at high risk for failing a

course or earning a low grade point average (Figure 9).

28

100

80

60

40

20

0

10

6

Ninth-Grade

Grade Point Average

Eighth-Grade

Course Failure

Percentage of Identified Students

68

51

Total: 57

Total: 78

Academic behaviors

Academic achievement

Figure 9: Rates of Correct Identification of

Students Most Likely to Fail at Least One Course in

Eighth Grade and Students Most Likely to Earn a

Grade Point Average Less than 2.0 in Ninth Grade

The figure shows that if EXPLORE Composite score alone were used

to identify the 5 percent of students in the course-failure sample who

were at the greatest risk of failing a course, 51 percent of them would

have been identified correctly. If the academic behaviors were used

in conjunction with EXPLORE Composite score, 57 percent would

have been identified correctly. Therefore, including academic

behaviors increases the accuracy of identifying students at high risk

for failing a course by 6 percentage points.

Similarly, if EXPLORE Composite score alone were used to identify

the 5 percent of students in the grade point average sample who

were at the greatest risk of earning a grade point average below 2.0,

68 percent of them would have been identified correctly. If the

academic behaviors were used along with EXPLORE Composite

score for identifying these students, 78 percent would have been

identified correctly. So including academic behaviors increases the

accuracy of identifying students at high risk for academic difficulty

by 10 percentage points.

Summary

Middle-school students who demonstrate those behaviors that

enhance academic achievement are more likely to perform well

academically in high school, and be ready for college and career

by the end of high school, than middle-school students who do not

demonstrate these behaviors. By considering these behaviors along

with academic achievement, educators can more accurately identify

students who are in greatest need of interventions to prevent them

from failing courses and dropping out of school, thus increasing the

likelihood that these students will graduate from high school ready

for college and career.

Teaching students to improve their academic behaviors can aid

them in developing their academic skills and thus put them on a

path toward improved readiness for college and career. In the next

chapter, we return to the subject of academic achievement and

focus on identifying the essential knowledge and skills that eighth-

grade students need to know to be on target for college and

career readiness.

29

31

3.

The Nonnegotiable

Knowledge and

Skills Needed by All

Eighth-Grade Students

ACT research shows that eighth-grade students who

are on target to be ready for college and career

by the end of high school have a high likelihood

of attaining that goal. The knowledge and skills

needed for high school should therefore be viewed

as essential, nonnegotiable standards that all

students should attain by the end of eighth grade.

Throughout this report, we have emphasized that all eighth-grade

students need to be on target for college and career readiness. But

in practical terms, what knowledge and skills do students need to

possess to have reached this level of achievement by the time they

begin high school?

ACT’s empirically based College Readiness Standards™ can be

used to define these skills, because the College Readiness

Standards represent what students need to know and be able to do

by the end of high school.

8

ACT’s College Readiness Standards are

vertically aligned with what postsecondary educators expect their

entering students to know and be able to do. EXPLORE and PLAN

are directly connected to the ACT in both content and score scale

and measure whether students are on target for college and career

readiness by eighth and tenth grade, respectively. The lists of

statements associated with the EXPLORE College Readiness

Benchmarks in each subject area—which are also empirically based,

having been derived from course-grade data on a large sample of

first-year students at postsecondary institutions nationwide—therefore

represent the essential knowledge and skills that eighth graders need

to possess in order to be on target for college and career readiness.

8

For more information about ACT’s College Readiness Standards, please see the Appendix.

32

Table 2 presents the essential standards that students need to attain by

the end of eighth grade in English, mathematics, reading, and science.

These standards are not intended to represent everything that should

and will be taught and learned by the end of eighth grade, nor how it

should be taught. Rather, the standards define the skills that our research

tells us are

essential

for entering high school students if they are to be on

target for college and career readiness by high school graduation. These

standards should be nonnegotiable for all students.

Table 2: Nonnegotiable Knowledge and Skills for Eighth-Grade Students to Be on Target

for College and Career Readiness

ENGLISH

Organization, Unity,

and Coherence

Word Choice in Terms

of Style, Tone, Clarity,

and Economy

Sentence Structure

and Formation

Conventions

of Usage

Conventions

of Punctuation

Use conjunctive adverbs

or phrases to show time

relationships in simple

narrative essays (e.g.,

then, this time

)

Revise sentences to

correct awkward and

confusing arrangements

of sentence elements

Revise vague nouns and

pronouns that create

obvious logic problems

Use conjunctions or

punctuation to join

simple clauses

Revise shifts in verb

tense between simple

clauses in a sentence or

between simple

adjoining sentences

Solve such basic

grammatical problems

as how to form the past

and past participle of

irregular but commonly

used verbs and how to

form comparative and

superlative adjectives

Delete commas that

create basic sense

problems (e.g., between

verb and direct object)

MATHEMATICS

Basic Operations

and Applications

Probability,

Statistics, and

Data Analysis

Numbers:

Concepts and

Properties

Expressions,

Equations, and

Inequalities

Graphical

Representations

Properties of

Plane Figures Measurement

Perform one-

operation

computation with

whole numbers

and decimals

Solve problems in

one or two steps

using whole

numbers

Perform common

conversions (e.g.,

inches to feet or

hours to minutes)

Solve routine one-

step arithmetic

problems (using

whole numbers,

fractions, and

decimals) such as

single-step

percent

Solve some

routine two-step

arithmetic

problems

Calculate the

average of a list

of positive whole

numbers

Perform a single

computation

using information

from a table or

chart

Calculate the

average of a list

of numbers

Calculate the

average, given

the number of

data values and

the sum of the

data values

Read tables and

graphs

Perform

computations on

data from tables

and graphs

Use the

relationship

between the

probability of an

event and the

probability of its

complement

Recognize

equivalent

fractions and

fractions in lowest

terms

Recognize one-

digit factors of a

number

Identify a digit’s

place value

Exhibit knowledge

of basic

expressions

(e.g., identify an

expression for a

total as

b

+

g

)

Solve equations

in the form

x

+

a

=

b

, where

a

and

b

are whole

numbers or

decimals

Substitute whole

numbers for

unknown

quantities to

evaluate

expressions

Solve one-step

equations having

integer or decimal

answers

Combine like

terms (e.g.,

2

x

+ 5

x

)

Identify the

location of a point

with a positive

coordinate on the

number line

Locate points on

the number line

and in the first

quadrant

Exhibit some

knowledge of the

angles associated

with parallel lines

Estimate or

calculate the

length of a line

segment based

on other lengths

given on a

geometric figure

Compute the

perimeter of

polygons when

all side lengths

are given

Compute the area

of rectangles

when whole

number

dimensions

are given

33

Note that, as opposed to the sometimes bewildering array of standards

that educators are often expected to teach their students, the standards

in Table 2 are neither numerous nor overwhelming in scope: just 7 in

English, 26 in mathematics, 6 in reading, and 16 in science (55 in all).

But empirical data have shown that they represent the skills needed for

high school and, ultimately, for college and career readiness.

In addition, these standards serve as the instructional links among

elementary school, middle school, and high school. These standards can

and should be used to articulate skills and courses between elementary

school and middle school and between middle school and high school.

And because these standards were originally based on the expectations

of postsecondary educators, the alignment between K–12 and

postsecondary education is inherent in their development.

READING

Main Ideas and

Author's Approach Supporting Details

Sequential,

Comparative, and

Cause-Effect

Relationships Meanings of Words

Generalizations and

Conclusions

Recognize a clear intent

of an author or narrator

in uncomplicated literary

narratives

Locate basic facts (e.g.,

names, dates, events)

clearly stated in a

passage

Determine when (e.g.,

first, last, before, after) or

if an event occurred in

uncomplicated

passages

Recognize clear cause-

effect relationships

described within a

single sentence in a

passage

Understand the

implication of a familiar

word or phrase and of

simple descriptive

language

Draw simple

generalizations and

conclusions about the

main characters in

uncomplicated literary

narratives

SCIENCE

Interpretation of Data Scientific Investigation

Evaluation of Models, Inferences, and

Experimental Results

Select a single piece of data (numerical or

nonnumerical) from a simple data

presentation (e.g., a table or graph with two

or three variables; a food web diagram)

Identify basic features of a table, graph, or

diagram (e.g., headings, units of

measurement, axis labels)

Select two or more pieces of data from a

simple data presentation

Understand basic scientific terminology

Find basic information in a brief body of text

Determine how the value of one variable

changes as the value of another variable

changes in a simple data presentation

Select data from a complex data

presentation (e.g., a table or graph with

more than three variables; a phase

diagram)

Compare or combine data from a simple

data presentation (e.g., order or sum data

from a table)

Translate information into a table, graph, or

diagram

Understand the methods and tools used in

a simple experiment

Understand the methods and tools used in

a moderately complex experiment

Understand a simple experimental design

Identify a control in an experiment

Identify similarities and differences between

experiments

Select a simple hypothesis, prediction, or

conclusion that is supported by a data

presentation or a model

Identify key issues or assumptions in a

model

Table 2 (continued)

Now that we have seen what level of achievement entering high

school students need to be on target for college and career

readiness, let’s consider what steps we need to take to help our

students get there. The next chapter presents detailed

recommendations for ensuring that all students who complete eighth

grade enter high school ready to succeed and leave high school

ready for the challenges of college and career.

35

4.

Recommendations

To maximize students’ readiness for college

and career by the time they graduate from high

school, we must address the needs of the students

in the Forgotten Middle and the role that upper-

elementary and middle school must play in

college and career readiness.

This research study addressed the following questions:

▼

How important is academic achievement in grade 8 for

predicting academic achievement in grade 11 or 12?

Of the academic factors we analyzed, eighth-grade academic

achievement and being on target for college and career

readiness in eighth grade have the greatest impact on college

and career readiness by the end of high school.

▼

How important are coursework and grades in high school for

predicting college and career readiness in grade 11 or 12?

Although high school coursework and high school grades have

a positive relationship with college and career readiness by the

end of high school, their impact is far outweighed by that of

eighth-grade academic achievement and being on target for

college and career readiness in eighth grade. Without sufficient

preparation before high school, students cannot maximize

the benefits of high school–level academic enhancements.

All students must be prepared to profit from high school.

▼

How much improvement in students’ college and career

readiness could we expect from their taking additional

rigorous courses and earning higher grades in high school?

Taken individually, these enhancements provide modest benefits

compared to raising student achievement and helping students

get on target for college and career readiness. However, when

eighth-grade students are ready for high school coursework, the

impact of taking rigorous high school courses and earning higher

grades is optimized.

▼

How does the academic progress that students make in

high school differ given their level of achievement in grade 8?

Compared to students who are not on target for college and career

readiness in eighth grade, students who are on target make greater

academic progress in high school—particularly between

36

grades 10 and 12—and are more likely to be ready for college and

career when they graduate from high school.

High school coursework and grades are important predictors of

students’ academic readiness for college-level courses, but the level

of academic achievement by eighth grade and being on target for

college and career readiness in eighth grade have the most

significant impact on college and career readiness. As this report has

shown, increasing eighth-grade students’ academic achievement by

grade 8 and helping them get on target for college and career

readiness would result in greater improvement in college and career

readiness than their simply taking additional standard courses or

advanced/honors courses in high school or earning higher grades in

high school.

Thus, making sure that all eighth-grade students have

attained the knowledge and skills that put them on target to

becoming ready for college and career is the single most important

step that can be taken to improve their college and career readiness.

Requiring high school students to take and pass more challenging

courses and to earn higher grades, and working with teachers and

administrators to improve the rigor of high school curricula, are

important strategies for achieving the broad goal of improving the