FINAL REPORT:

Understanding Variations in International

Drug Prices

NORC PROJECT NO. 6319 JULY 27, 2006

TASK ORDER # HHSP233000007T / CONTRACT # 100-03-0020

SUBMITTED TO:

OFFICE OF THE ASSISTANT SECRETARY FOR PLANNING AND EVALUATION

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

200 INDEPENDENCE AVENUE, S.W.

WASHINGTON, D.C. 20201

PRESENTED BY:

NATIONAL OPINION RESEARCH CENTER (NORC)

AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

1350 CONNECTICUT AVENUE, N.W., SUITE 500

W

ASHINGTON, D.C. 20036

WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF:

GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY HEALTH POLICY INSTITUTE

AND

IMS

HEALTH

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

i

This report was prepared by NORC at the University of Chicago under contract to the Assistant Secretary

for Planning and Evaluation. The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the author(s) and do

not necessarily represent the views of ASPE or HHS.

This report was produced under the direction of Laina Bush,

Task Order Officer, Office of the Assistant Secretary for

Planning and Evaluation, Office of Science and Data Policy,

Jim Scanlon, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Planning and

Evaluation (Science and Data Policy), Don Young, Acting

Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. This report is

available online at: http://aspe.hhs.gov/sp/reports/2007/UVIDP/.

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

ii

Project Director:

Elizabeth Hargrave, NORC at the University of Chicago

Staff contributing to this report (in alphabetical order):

Ken Copeland, IMS Health

Jérôme Caron, IMS Health

Elizabeth Eaton, Georgetown University

Ed Evaldi, IMS Health

Jyoti Gupta, NORC at the University of Chicago

Jack Hoadley, Georgetown University

Grace Yang, NORC at the University of Chicago

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

iii

Understanding Variations in International Drug Prices

Table of Contents

Understanding Variations in International Drug Prices...............................................................................1

Background ....................................................................................................................................................1

Methodology ..................................................................................................................................................2

Results.............................................................................................................................................................5

Differences in U.S. and Canadian Prices for Individuals with Third-Party Coverage...........5

Differences in U.S. and Canadian Prices for Individuals without Third-Party Coverage.....5

Comparing U.S. Copayments to the Full Cost of Drugs in Canada ........................................8

Price Differences by Patent and Trademark Status....................................................................9

Testing the Impact of Substituting Drugs Without a Direct Equivalent in Canada............12

Conclusion....................................................................................................................................................13

Appendix A: Methodology............................................................................................................................14

Selecting Population Groups and Their Market Baskets.......................................................................14

Identifying Potential Market Baskets ...................................................................................................14

Selecting Population Groups ................................................................................................................15

Working with Price Data............................................................................................................................18

Matching Drug Names to Prices ..........................................................................................................18

Matching with Canadian Drugs ............................................................................................................18

Weighting .................................................................................................................................................22

Currency conversion ..............................................................................................................................22

Sensitivity to Drug Substitutions..........................................................................................................22

Changes in Drug Use Since 2003 .........................................................................................................24

Prescriptions vs. Spending.....................................................................................................................25

Payer Type and Retail vs. Total Price ..................................................................................................26

Market Baskets.............................................................................................................................................27

Appendix B: Literature Review.....................................................................................................................42

The Canadian Pricing System....................................................................................................................42

Methodology of Price Comparisons.........................................................................................................44

Price Comparisons ......................................................................................................................................46

Studies of Wholesale or Manufacturer Prices.....................................................................................49

Studies of Retail Prices...........................................................................................................................52

Discussion ....................................................................................................................................................55

Appendix C. Works Cited .............................................................................................................................56

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

iv

Table of Figures

Figure 1. Weighted Average Price Per Prescription, by Market Basket and Payment Type..................6

Figure 2. Average of Per-Prescription Prices for All 15 Market Baskets, by Type of Coverage ..........7

Figure 3. Copayments in the United States vs. Full Price of Drugs in Canada .......................................8

Figure 4. Average Total Price Per Prescription, by Product Type and Payment Type ..........................9

Figure 5. Variation in Relative Difference of Generic Prices...................................................................10

Figure 6. Relationship Between Makeup of Market Basket and Relative Prices ...................................11

Figure 7. Sensitivity of Average Difference Between U.S. and Canadian Price to Inclusion of Zyrtec

and Toprol XL ........................................................................................................................................12

Figure A-1. Rank Order Correlation of Drugs Used, by Age Group.....................................................15

Figure A-2. Rank Order Correlation of Drugs Used, by Race.................................................................16

Figure A-3. Rank Order Correlation of Drugs Used, by Income............................................................16

Figure A-4. Rank Order Correlation of Drugs Used, by Insurance Status ............................................17

Figure A-5. On-Patent Drugs with Same Manufacturers but Different Names ...................................19

Figure A-6. Generic Drugs with Different Names and Manufactures in the U.S. and Canada..........19

Figure A-7. Dosage Levels Substituted in U.S. and Canadian Market Baskets .....................................20

Figure A-8. Dosage Levels Substituted in Canadian Market Baskets Only ...........................................21

Figure A-9. Drugs Not Available in Canada...............................................................................................21

Figure A-13. Market Basket for Females Under 12...................................................................................27

Figure A-14. Market Basket for Females 12-24 .........................................................................................28

Figure A-15. Market Basket for Females 25-39 .........................................................................................29

Figure A-16. Market Basket for Females 40-64 .........................................................................................30

Figure A-17. Market Basket for Females 65+ ............................................................................................31

Figure A-18. Market Basket for Males Under 12.......................................................................................32

Figure A-19. Market Basket for Males 12-24..............................................................................................32

Figure A-20. Market Basket for Males 25-39..............................................................................................33

Figure A-21. Market Basket for Males 40-64..............................................................................................34

Figure A-22. Market Basket for Males 65+ ................................................................................................35

Figure A-23. Market Basket for Insured .....................................................................................................36

Figure A-24. Market Basket for Uninsured ................................................................................................37

Figure A-25. Market Basket for Non-Hispanic Whites ............................................................................38

Figure A-26. Market Basket for African Americans..................................................................................39

Figure A-27. Market Basket for Hispanics..................................................................................................40

Figure A-28. Summary of Drugs Included in Market Baskets.................................................................41

Figure B-1. Summary of U.S./Canada Prescription Drug Price Comparisons: Studies of

Manufacturer or Wholesale Prices .......................................................................................................47

Figure B-2. Summary of U.S./Canada Prescription Drug Price Comparisons: Studies of Retail

Prices.........................................................................................................................................................48

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

1

Understanding Variations in International Drug Prices

Rapidly rising prescription drug prices have caused many consumers, third-party payers, and

policymakers to look for ways to lower their drug costs. One strategy that many have seen as a

potential solution is to import drug products from countries where drug prices are lower than those

in the United States – commonly called reimportation. This report focuses on the differences

between prices in the United States and Canada, and seeks to create an “apples-to-apples”

comparison of the prices consumers might face for a specific market basket of drugs in each

country, taking into account any insurance coverage they might have. We make this comparison for

fifteen different market baskets of drugs, to test the sensitivity of results to the drugs selected.

Across the different market baskets, Canadian prices were about one-third lower on average than the

prices charged to insured Americans. Because those without coverage in the United States do not

have access to the discounts negotiated by third-party payers, these individuals would find that

typical prices in Canada are about half of those they face in the United States. Overall, differences

are larger for brand-name drugs, and much smaller for generic drugs. In fact, prices for generic

drugs are likely to be higher in Canada, at least compared to the prices charged to people in the

United States with insurance coverage.

Background

While Canada offers universal access to health insurance, that insurance covers only acute hospital

and physician services, and does not provide coverage for outpatient prescription drugs. Most

Canadians receive prescription drug coverage through their employers. The federal government

offers drug coverage to some populations, including veterans and First Nations and Inuit people,

and there are publicly funded provincial programs that pay a substantial share of drug costs for

older, disabled, and low-income Canadians (Gross, 2003). These provincial programs cover 42

percent of all national drug expenditures (Morgan, 2003).

Prices for newly-patented drugs are controlled by federal regulation in Canada. Prices for new brand

drugs are limited to the median of prices for the new drug in France, Germany, Italy, Sweden,

Switzerland, England, and the United States. Limits for “me-too” drugs are based on the

breakthrough brand’s price; most new drugs cannot cost more than the other drugs in the same

therapeutic class. Annual increases in prices for existing on-patent drugs are limited by the

consumer price index (CPI): in a single year, prices cannot rise more than 1.5 times the CPI

(PMPRB, 2006). This limit is lower than recent increases in prices for many on-patent drugs in the

United States (Gross et al, 2006).

The provinces all use formularies to keep prices low for the drugs they cover, and new drugs that are

equivalent to already listed drugs are added only if they do not increase program costs. Some

provinces take further measures. Ontario has instituted price freezes; British Columbia uses

reference pricing; and Quebec requires manufacturers to give the province the best price given to

any other province (Morgan, 2003).

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

2

Legislative and regulatory price controls in the United States apply only to drugs purchased by the

Medicaid program, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Federal Supply Schedule, which is

used by the health programs run by the Department of Defense and other eligible entities (e.g.,

certain community health centers and public hospitals). However, insurers and pharmacy benefit

managers (PBMs) are also able to negotiate substantial discounts and rebates from retail prices.

These discounts take two forms. First, third-party payers are able to negotiate discounts with

pharmacies on the prices they charge at the pharmacy counter. These discounts are typically taken

off the pharmacy’s markup over their acquisition cost for the drug, and the effect of the discount is

seen at the time an insured customer purchases a drug.

The second type of discount is negotiated directly between third-party payers and manufacturers.

Typically, rebates are paid by the manufacturers of on-patent drugs in exchange for giving

preferential status to a drug and demonstrating a shift of market share away from competing

products. These rebates are separate from the pharmacy transaction. A 2000 ASPE study cited

evidence that average rebates tend to be about 5 to 7 percent of drug prices, but can be as high as 35

percent on selected drugs (HHS, 2000). Research by the Congressional Budget Office, in

connection with the Medicaid drug rebate, found that price discounts including rebates generally

range as high as about 20 percent (CBO, 1996).

Uninsured individuals typically do not have access to negotiated prices of either kind. These

individuals have been at the forefront of the push to import drugs from Canada. Some third-party

purchasers, including several municipal government employee plans, have also begun to explore the

possibility of savings for their insured employees from reimportation.

Previous studies have found that prices for prescription drugs are frequently lower in Canada than in

the United States, as detailed in Appendix B. The literature also includes critiques of some of these

studies (for example, Danzon and Kim). We have attempted to address several of the concerns

raised in these critiques with the approach taken in this report. In particular, we explore two factors

that could influence these observed differences between U.S. and Canadian prices: the market

basket of drugs selected for comparison, and whether the purchaser has third-party coverage for the

prescription at the time of purchase.

Methodology

The goal of this study is to determine the difference between U.S. and Canadian prices at the retail

point of sale for the prescription drugs that are purchased by U.S. customers. Our primary question

was, what would U.S. customers pay if they were able to purchase their drugs at Canadian prices?

Throughout the design of the project, we have used this research question to help shape our

methodology.

Price comparisons can be sensitive to the market basket of drugs included in the study. In

particular, generic drugs and brand-name drugs tend to have quite different pricing patterns, which

can affect the outcome of a price comparison. Our goal in this study was to test a variety of market

baskets, but to make each of them representative of the drugs used by a subpopulation in the United

States. We selected fifteen groups based on age, gender, race, and insurance status, which were

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

3

identified from a larger set of groups as those with distinctive patterns of drug use. For each group,

we selected the most commonly used drugs accounting for a third of that population’s prescriptions

in the 2003 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). We then identified the most commonly

used form and strength of each drug for each group, so that we could limit our data collection to a

precisely specified set of drugs. The resulting market baskets each had from 8 to 32 drugs, with a

total of 106 drugs across the 15 groups. These drug lists are included at the end of Appendix A.

Although some drugs are included in at least half of all the market baskets, the mix of drugs varies

considerably. The market baskets for those over age 65 are dominated by treatments for the chronic

conditions that accompany older ages, whereas market baskets for children include a mix of

antibiotics, behavioral medications, and asthma drugs. Those for young women include various

contraceptive drugs.

For these commonly used drugs, we then sought to find their counterparts in Canada. We tried to

assure that the match between our U.S. market baskets and Canadian market baskets is as close as

possible, while still representing the utilization of the population groups we identified. We first

looked for an exact match by drug name, form, and strength between the United States and Canada.

When an exact match was not available in Canada, we sought to match drugs by chemical entity, and

when possible, by patent and trademark status and/or manufacturer. There were several drugs on

our list at a dosage level not available in Canada. When possible, we used another dosage level that

is available in both countries as a substitute in both the U.S. and Canada market baskets; otherwise,

we used the dosage available in Canada closest to the most common U.S. dosage. More information

on this matching process is available in Appendix A.

Once we had specified our list of drugs for the United States and Canada, we then used data

collected by IMS Health to identify the average price per pill (or, for other forms such as liquids and

inhalers, the average price for a set amount) for each drug in both countries. The IMS prescription

databases represent very large, non-probability samples of prescriptions dispensed at retail

pharmacies in the United States and in Canada. The data are representative of prescription

transactions for both large retail pharmacy chain organizations and small independent pharmacies.

In the United States, the IMS sample is geographically representative of all 50 states plus the District

of Columbia and Puerto Rico. The databases include all prescriptions dispensed at over 35,000 retail

pharmacies in the United States, representing two-thirds of all U.S. retail pharmacies and an

estimated 70 percent or more of all prescription transactions in the retail pharmacy sector.

In Canada, the IMS sample includes over 4,300 retail pharmacies, representing 60 percent of all

Canadian retail pharmacies and an estimated 70 percent of all prescription transactions. However,

we used data only from Ontario and Quebec, which make up nearly three fourths of the overall IMS

sample (3,100 pharmacies). These two provinces are the only ones for which IMS collects data on

the type of payer, a critical part of our analysis. In addition, IMS has determined that in other

provinces, pharmacies frequently report list prices rather than actual prices. Prior IMS work with

Canadian prescription data, in conjunction with understanding of pharmaceutical price controls in

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

4

effect in Canada, suggest that there is little variation in prices between these two provinces and the

rest of Canada.

1

Using data from MEPS about the most common prescription size, we standardized the IMS per-pill

price to represent an average per-prescription price for each drug. This method allowed us to

eliminate any price disparities that might result from practice patterns or prescription-filling behavior

that would lead to price differences caused by prescriptions covering different periods of time (e.g.,

30 vs. 90 days) in the two countries. From these standardized per-prescription prices, we calculated

an index price for each market basket, weighting based on utilization of each drug within the market

basket for each population.

While in Canada there is little variation in the prices paid by different payers, in the United States the

cost of drugs can vary widely according to who is purchasing drugs. Individuals paying cash pay the

highest price, while insurers, managed care plans, and government programs can negotiate pharmacy

discounts and manufacturer rebates because they represent large numbers of customers. One goal of

this report is to explore the effect of these intra-country price differences on cross-country

comparisons. In this report, we separate the prices paid by individuals who had a third-party

payment from the prices paid by those who paid the entire cost of a prescription themselves.

2

In identifying the third-party prices, we have no access to proprietary rebate amounts and have not

attempted to estimate them.

3

The prices reported in this paper likely reflect the discounts that

insurers have negotiated with pharmacies, but not the additional discounts they have received from

manufacturers separate from the pharmacy transaction. The effect of including these rebates, if they

were available, would be to reduce the overall amount paid by third-party insurers for brand name

drugs and to reduce the difference between the United States and Canada for the prices of these

drugs.

There are several issues that are beyond the scope of this paper. We do not address here the safety

or legality of importing drugs to the United States from Canada. Likewise, we do not estimate the

shifts in manufacturer pricing behavior that would likely occur if reimportation became widespread,

or if policy changes in the United States attempted to force manufacturers to provide drugs to

customers at Canadian prices. HHS addressed many of these issues in its 2004 report to Congress

on prescription drug importation.

1

In particular, it is likely that customers without third-party coverage are paying prices close to the national limits set by

the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board. In this study, we find that in Canada, third-party prices are extremely close

to the prices paid by individuals without third-party coverage. Third-party payers in these provinces appear to be getting

little additional discount despite the extra limits set by the provincial governments for drugs purchased through

provincial programs.

2

We report prescriptions as “with third-party coverage” if a third party was involved at the time of the pharmacy

transaction, including prescriptions that were only discounted. (e.g., because the customer had a discount card). We

report prescriptions as “without third-party coverage” if a third party was not involved in the transaction at the

pharmacy counter. It is possible that some of these latter customers may be submitting receipts to an insurer for

reimbursement. However, without the involvement of an insurer at the time of the transaction, we assume the price

paid for these prescriptions is not discounted.

3

Other authors, including the HHS Task Force on Drug Importation (Report on Prescription Drug Importation, p. 115), have

attempted to estimate the rebates paid from manufacturers to pharmacies and wholesalers. We do not consider these

rebates here as we are studying prices paid by customers at the pharmacy counter, not pharmacy acquisition prices.

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

5

Results

For each of our fifteen market baskets of drugs, the total price paid for drugs in Canada is

consistently lower than the total price paid in the United States. This is true for individuals with and

without third-party coverage. However, the difference is greater for individuals without third-party

coverage.

Differences in U.S. and Canadian Prices for Individuals with Third-Party Coverage

For prescriptions filled by individuals with third-party coverage, the difference between Canadian

and U.S. prices ranges from about 30 percent lower for the market basket that represents the drugs

most commonly used by girls under 12, to as much as 47 percent lower for the market basket of

drugs that represents the drugs most commonly used by women ages 25 to 39 (Figure 1). Both the

average and the median of the differences for all fifteen market baskets are about 36 percent.

4

These observed price differences are in the general range of those found in the literature (see

Appendix B). Several of the studies described in the Appendix found differences in the range of 30

to 50 percent (with at least one considerably higher and one considerably lower). This consistency

of results provides some reassurance that the methodology used in this study is not creating

unexpected results. The consistency of results across market baskets is also significant. Although

there is variation, the price difference for most market baskets are remarkably consistent despite

differences in drug mix. As discussed below, the main difference results from the mix of brand and

generic drugs.

Differences in U.S. and Canadian Prices for Individuals without Third-Party

Coverage

For those without third party coverage, the prices reported are the total price paid by the individual

to the pharmacy. There is an even larger difference between U.S. and Canadian prices for these

customers (Figure 1). The market basket for drugs commonly taken by men aged 65 and over has

the smallest difference, with prices in Canada 38 percent lower than in the United States. The

market basket for the drugs commonly taken by women aged 25-39 again has the highest difference,

with Canadian prices 54 percent lower than U.S. prices. Both the average and the median of the

differences for all fifteen market baskets are about 45 percent.

4

For those with third-party coverage, the prices presented here include the total price paid at the pharmacy, including

both the insurance payment and any copayment made by the patient.

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

6

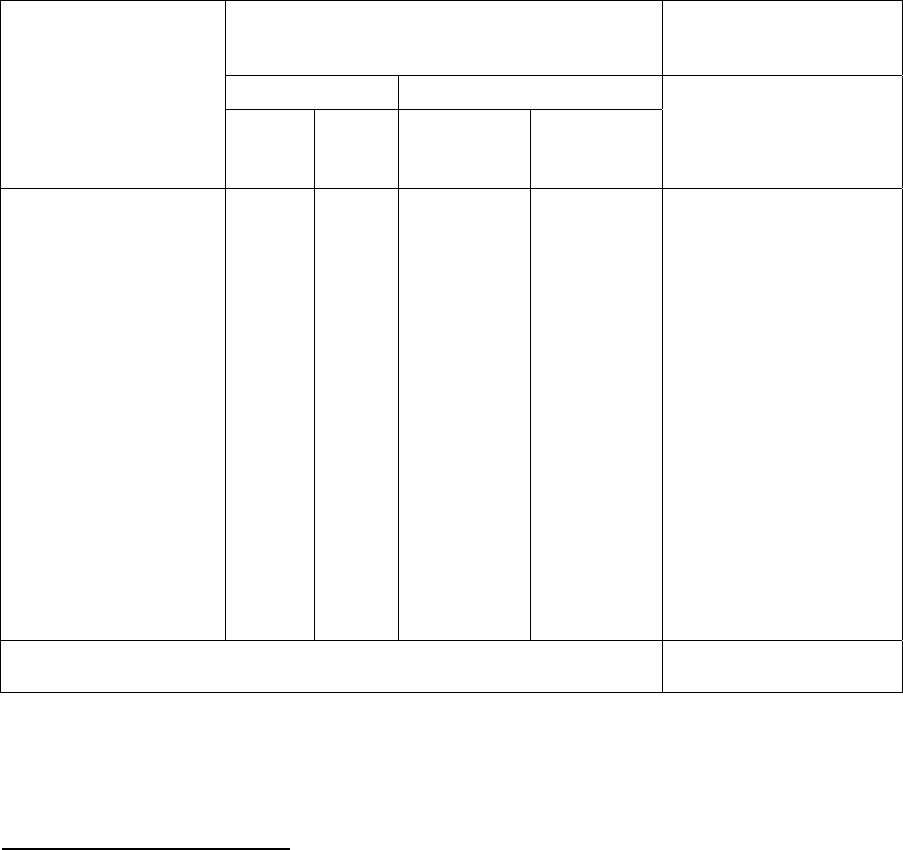

Figure 1. Weighted Average Price Per Prescription, by Market Basket and Payment Type

With Third-Party Coverage Without Third-Party Coverage

Market Basket:

Drugs Taken By...

U.S. Canada Difference U.S. Canada Difference

Females under 12 $31.44 $21.99 -30.1% $41.43 $22.70 -45.2%

Females 12-24 $45.93 $27.60 -39.9% $54.69 $28.56 -47.8%

Females 25-39 $48.47 $25.69 -47.0% $57.05 $26.44 -53.6%

Females 40-64 $51.78 $30.61 -40.9% $59.66 $31.00 -48.0%

Females 65+ $45.44 $28.48 -37.3% $50.82 $29.01 -42.9%

Males under 12 $39.07 $26.96 -31.0% $50.17 $27.64 -44.9%

Males 12-24 $70.48 $46.94 -33.4% $84.95 $47.85 -43.7%

Males 25-39 $68.04 $39.41 -42.1% $80.28 $40.06 -50.1%

Males 40-64 $57.24 $36.72 -35.9% $65.42 $37.50 -42.7%

Males 65+ $41.80 $28.99 -30.6% $47.46 $29.45 -37.9%

Insured $52.94 $31.60 -40.3% $61.24 $32.15 -47.5%

Uninsured $37.59 $25.80 -31.4% $43.47 $26.19 -39.8%

Whites $47.19 $28.80 -39.0% $54.49 $29.30 -46.2%

African Americans $47.16 $30.72 -34.9% $54.17 $31.19 -42.4%

Hispanics $36.84 $24.47 -33.6% $43.83 $24.75 -43.5%

Notes: Index price is a weighted average of the prices of the most common form and strength of the most commonly used drugs

for each population group.

Prices are in U.S. dollars, using the average exchange rate for the period of data collection.

Difference between U.S. and Canada prices calculated as (Canada price-U.S. price)/U.S. price.

Market baskets include the drugs most commonly used by individuals in each population group. Prices reflect the prices

paid by all individuals, not restricted to the population group. For example, the insured market basket includes the drugs

most commonly used by people with insurance. The price indices for that market basket use data for all people who

bought the drugs in that market basket, so it is possible to have a price index for uninsured individuals who purchased the

drugs in the insured market basket.

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

7

The higher differential between U.S. and Canadian prices for customers without third-party

insurance appears to be due largely to the difference between the prices paid by customers with and

without insurance within the United States (Figure 2). For any given market basket, the index price

in Canada is only 1 percent to 4 percent higher for customers without third-party insurance

compared to customers with insurance – when the market basket index prices are averaged, the

difference is less than a dollar. In contrast, uninsured customers in the United States pay 12 percent

to 32 percent more for a market basket of drugs than the cost of the same drugs for customers with

insurance, a difference of about $8.50 across all market baskets. The latter result is consistent with

findings from earlier work by ASPE in 2000 (HHS, 2000).

Figure 2. Average of Per-Prescription Prices for All 15 Market Baskets, by Type of Coverage

$48.09

$56.61

$30.32

$30.92

$0

$10

$20

$30

$40

$50

$60

US, With Third Party

Coverage

US, Without Third

Party Coverage

Canada, With Third

Party Coverage

Canada, Without

Third Party Coverage

Average Price Per Prescription

(Average of All 15 Market Baskets

)

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

8

Comparing U.S. Copayments to the Full Cost of Drugs in Canada

The price comparisons for the full cost of drugs are the most relevant for many U.S. citizens without

insurance coverage for their drugs who seek savings by getting drugs in Canada. By contrast, most

individuals with coverage will not achieve savings unless their third-party agent is involved in the

transaction. Insured consumers considering drug purchases in Canada may find their insurance

coverage is not applicable for purchases from Canadian pharmacies. Thus, the relevant comparison

for these customers is between the copayment they are charged at their U.S. pharmacy and the full

cost of the drug in Canada.

In fact, individuals with insurance are unlikely to be able to find prices in Canada that are lower than

the copayments they pay for drugs that are covered by their insurance. On average across our

market baskets, the Canadian price is about 78 percent higher than the out-of-pocket cost to a

person in the United States with third party coverage (Figure 3), with a range from 31 percent to 141

percent higher. This result is not surprising given that insured consumers are paying only a share of

the total drug cost out of pocket.

There may be situations in which these individuals could achieve savings with Canadian drug prices.

For example, if their coverage includes a cap with an annual or quarterly spending limit (such as in

some Medicare Advantage plans prior to 2006), a gap in coverage (such as that faced in the new

Medicare drug benefit), or a limit on the number of monthly prescriptions, individuals may find that

it would be less expensive to buy drugs in Canada than to pay the full cost of a drug in the United

States. Those who want to take a particular drug that is not covered by their insurer’s formulary

might also benefit from the price differential by making purchases in Canada.

Figure 3. Copayments in the United States vs. Full Price of Drugs in Canada

$17.35

$48.09

$30.92

$0

$10

$20

$30

$40

$50

US, With Third Party Coverage Canada, Without Third Party

Coverage

Average Price Per Prescription

(Average of All 15 Market Baskets

)

average

customer share:

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

9

Price Differences by Patent and Trademark Status

There is a dramatic variation in the differential between U.S. prices and Canadian prices depending

on the patent and trademark status of drugs. When generics and brand name drugs are identified

separately, brand name drugs show even larger differences between U.S. and Canadian prices.

Generics show smaller differences, or the direction of the difference changes, depending on the type

of payer.

The on-patent brand name drugs in our market baskets cost 43 percent less for individuals with

insurance and 50 percent less for individuals without insurance in Canada compared to U.S. prices

(Figure 4). The absolute price differences are also largest for brand name drugs, particularly the on-

patent brands in our market baskets.

As with the results for the overall market baskets, the variation in differences based on insurance

coverage appears to be because in the United States, transactions with third-party involvement cost

about 14 percent less than transactions without third-party coverage. Again, this is likely because of

discounts that third-party payers have negotiated with pharmacies. However, even after this third-

party discount, the difference between prices in the United States and Canada is substantial. The

remaining difference likely results from a combination of regulatory measures in Canada and the

market decisions made by manufacturers.

The availability of manufacturer rebates could further mute some of the difference between the

United States and Canada for third-party payers. Typically, rebates are only available for brand-

name drugs, and mostly for those that remain on patent. Previous studies have found that rebates

can be as high as 20 percent (CBO, 1996) to 35 percent (HHS, 2000) on selected drugs. Even if

amounts toward the higher end of these estimates were appropriate for most of the drugs in our

market baskets, the differences would fall short of the 43 percent average differential observed for

on-patent brand drugs.

Figure 4. Average Total Price Per Prescription, by Product Type and Payment Type

With Third-Party Coverage Without Third-Party Coverage

Product Type

Number

of Drugs

U.S. Canada Difference U.S. Canada Difference

Generic

27 $10.75 $14.75 37% $15.49 $14.92 -4%

Branded Generic

10 $25.79 $22.83 -11% $30.81 $23.45 -24%

Off-Patent Brand

19 $37.01 $17.10 -54% $42.65 $17.32 -59%

On-Patent Brand

38 $125.36 $71.37 -43% $145.91 $73.08 -50%

Notes: Index price is a non-weighted average of the prices for each type of drug included in any market basket for this study.

Prices are in U.S. dollars, using the average exchange rate for the period of data collection.

Difference between U.S. and Canada prices calculated as (Canada price-U.S. price)/U.S. price.

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

10

Generic drugs follow a much different pattern. For customers with insurance coverage, the full cost

of the generic drugs in our market baskets is actually higher in Canada than in the United States

(Figure 4). For customers without insurance coverage, generics are only 4 percent less expensive in

Canada than in the United States.

ASPE’s 2000 study showed relatively little price difference for generic drugs between the prices paid

by customers with a third-party payer and prices paid by those without coverage (HHS, 2000). That

does not appear to be the case for the generic drugs selected for our market baskets. The average

price of these drugs is about a third lower for customers with third-party coverage in the United

States compared to those without coverage. This third-party discount appears to be what is causing

U.S. generic prices to be lower than Canadian generic prices, for the drugs selected.

Previous studies have found more variability in the prices of generic drugs than in the prices of

generics. Possibly related to this general variation, we found variation from market basket to market

basket in the difference between U.S. and Canadian prices for generic drugs (Figure 5). For

customers with third-party coverage, we consistently find that U.S. prices are lower than Canadian

prices, but the difference ranges from 23 to 63 percent. For customers without third-party coverage,

Canadian prices are nearly 20 percent lower for some market baskets and over 20 percent higher for

other market baskets. The range in variation in the prices of brand name drugs among our market

baskets is only half as large.

Figure 5. Variation in Relative Difference of Generic Prices

Relative Difference Between Canadian and

U.S. Price

Market Basket:

Drugs Taken By...

Number of

Generic

Products in

Market

Basket

With Third-

Party Coverage

Without Third-Party

Coverage

Females under 12 2 53.6% -18.6%

Females 12-24 3 47.0% -18.1%

Females 25-39 4 42.8% -19.6%

Females 40-64 8 78.5% 24.0%

Females 65+ 7 59.8% 21.2%

Males under 12 2 47.9% -19.8%

Males 12-24 3 23.0% -10.7%

Males 25-39 5 75.7% 6.8%

Males 40-64 9 60.7% 9.3%

Males 65+ 11 49.4% 8.0%

Insured 8 53.6% 2.7%

Uninsured 11 46.0% -1.0%

Whites 10 62.5% 8.6%

African Americans 8 53.6% 6.5%

Hispanics 14 49.5% -4.8%

Notes: Index price is a non-weighted average of the prices for each type of drug included in any market basket for this study.

Difference between U.S. and Canada prices calculated as (Canada price-U.S. price)/U.S. price.

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

11

Figure 6 shows the proportion of each market basket that is made up of brand and generic drugs.

The market baskets we have selected have non-trademark generic use ranging from a low of 15

percent for females 25-39 to a high of 54 percent for males aged 65 and over. Including branded

generics, the generic rate ranges from 21 percent to 57 percent. This variation in generic use is

consistent with the wide variation in the types of drugs taken by these groups. For example, the

drugs in our market basket for young women include many on-patent birth control pills, while the

market basket for older men includes more generic heart medications.

5

Figure 6. Relationship Between Makeup of Market Basket and Relative Prices

Proportion of Market Basket, Weighted by

Utilization

Difference in Price Per

Prescription,

Canada vs. U.S.

Brand Generic

Market Basket:

Drugs Taken By...

On

Patent

Off

Patent

Trademark

(Branded

Generic)

Non-

Trademark

With

Third-

Party

Coverage

Without

Third-

Party

Coverage

Females under 12 22% 28% 8% 41% -30% -45%

Females 12-24 60% 15% 4% 21% -40% -48%

Females 25-39 52% 23% 10% 15% -47% -54%

Females 40-64 45% 27% 3% 25% -41% -48%

Females 65+ 45% 18% 4% 33% -37% -43%

Males under 12 25% 18% 15% 42% -31% -45%

Males 12-24 50% 8% 20% 23% -33% -44%

Males 25-39 57% 22% 0% 21% -42% -50%

Males 40-64 52% 13% 0% 36% -36% -43%

Males 65+ 34% 12% 0% 54% -31% -38%

Insured 50% 18% 2% 29% -40% -48%

Uninsured 32% 16% 3% 50% -31% -40%

Whites 48% 18% 3% 31% -39% -46%

African Americans 40% 16% 0% 44% -35% -42%

Hispanics 32% 15% 2% 51% -34% -44%

Correlation with Proportion of Market Basket On Patent -0.79 -0.52

Correlation with Proportion of Market Basket Non-Trademark Generic 0.82 0.84

Note: Difference between U.S. and Canada prices calculated as (Canada price-U.S. price)/U.S. price.

5

Nationally, both Express Scripts and the Generic Pharmaceutical Association reported that generics accounted for just

over half of all prescriptions in 2003. It may be that the bottom two-thirds of drugs used by each population group are

slightly more likely to be generics than the drugs we selected for our market baskets. (see Express Scripts, “Geographic

Variation in Generic Fill Rate”, http://www.express-scripts.com/ourcompany/news/outcomesresearch/

onlinepublications/study/regionalgenericvariation.pdf, and GPhA “Statistics,” http://www.gphaonline.org/

Content/NavigationMenu/AboutGenerics/Statistics/Statistics.htm)

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

12

Consistent with the findings in Figure 4, market baskets with a higher proportion of generic drugs

tend to show lower differences between Canadian and U.S. prices (correlation is .82 for third-party

and .84 without third-party coverage). Likewise, market baskets with a higher proportion of on-

patent brand drugs tend to show higher differences between Canadian and U.S. prices (correlation is

-.79 for third-party and -.52 without third-party coverage). For example, the drugs taken by young

adults (women 25-39 and men 25-39) have the largest differential between U.S. and Canadian prices,

and both have market baskets with a high proportion of brand-name drugs.

The use of multiple market baskets allows us to see a range of possible effects while still basing

measurements on actual utilization instead of an arbitrarily selected set of drugs. It is notable that

despite this variation, the difference between Canadian and U.S. prices remains within a fairly small

range.

Testing the Impact of Substituting Drugs Without a Direct Equivalent in Canada

Two drugs included in our market baskets had unusual circumstances that resulted in higher-than-

average differences between the U.S. price and Canadian price. Zyrtec (cetirizine hydrochloride), an

on-patent brand name prescription drug in the United States, is available over-the-counter in Canada

as Reactine. We included this medication in our Canadian market baskets, utilizing data on

prescription transactions for Reactine. Toprol XL (metoprolol succinate), another on-patent brand

name drug, is not available in Canada. We included a close substitute, Lopressor SR (metoprolol

tartrate), in the relevant Canadian market baskets. In both cases, we were following the principle that

we were seeking to find the drugs that U.S. customers would find in Canada as the closest match for

the drugs they take.

In all market baskets, excluding these two brand-name drugs makes the difference between the two

countries’ prices smaller (Figure 7). In thirteen of the fifteen market baskets, the difference is 2.2

percentage points or less (regardless of payer). The exception is the market baskets for children

under 12. Zyrtec accounts for about a tenth of the prescriptions included in each of these market

baskets, and its exclusion gives generic drugs a larger share of each market basket. The result is a

more notable drop in the relative difference between U.S. and Canadian prices for these two groups.

The change is particularly notable for prescriptions purchased with third party coverage, where the

difference between United States and Canada for these two groups of drugs falls to 21.5 percent for

girls and 23.5 percent for boys. While these results show that the selection of individual drugs for a

market basket can affect the magnitude of the results, the change is not enough to affect the overall

result that prices in Canada are substantially lower than prices in the United States.

Figure 7. Sensitivity of Average Difference Between U.S. and Canadian Price to Inclusion of

Zyrtec and Toprol XL

With Third-Party

Coverage

Without Third-Party

Coverage

Including Zyrtec and Toprol XL -36.5% -46.2%

Excluding Zyrtec and Toprol XL -34.1% -44.2%

Note: Unweighted average of results for 15 market baskets.

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

13

Conclusion

This report finds differences between Canadian and U.S. drug prices that are generally consistent

with the existing literature on international drug pricing. Uninsured customers in the United States

would find Canadian prices to be about half the prices they pay in the United States. Insured

consumers seeking to buy the drugs they currently buy in Canada would find, on average, prices that

are about a third lower than the total cost of their drugs, but higher than the copays they currently

pay. These findings are somewhat sensitive to different market baskets. While the overall result that

prices are lower in Canada is fairly consistent, the inclusion of more generic drugs can decrease the

difference between Canadian prices and U.S. prices.

The differing spread in prices depending on patent and trademark status is a result worth

emphasizing. Generic drug prices are mostly equivalent or higher in Canada, whereas brand drugs

are substantially less expensive in Canada. Because on-patent brand name drugs have the highest

prices, they also are the products with the largest absolute difference between Canadian and U.S.

prices.

There are several issues related to these questions that are beyond the scope of this paper. We do

not address here the safety or legality of importing drugs to the United States from Canada.

Likewise, we do not estimate the shifts in manufacturer pricing behavior that would likely occur if

reimportation became widespread, or if policy changes in the United States attempted to force

manufacturers to provide drugs to customers at Canadian prices. HHS addressed many of these

issues in its 2004 report to Congress on prescription drug importation (HHS, 2004).

Absent these widespread market shifts and other concerns, individuals without insurance coverage

can find substantial savings in Canada for the commonly used drugs included in this study. Third-

party insurers face a more complicated arithmetic. For generic drugs, third-party payers seem to be

able to achieve enough savings through pharmacy discounts so that they would not save by steering

their enrollees to Canada. For brand-name drugs, however, there is a large difference in prices

between the United States and Canada even after these discounts. Whether third party payers could

do better by purchasing drugs at Canadian prices largely depends on whether the additional

manufacturer rebates they receive on brand-name drugs are larger than the differences reported

here.

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

14

Appendix A: Methodology

This appendix describes our methodology for selecting market baskets of drugs and identifying

prices for those market baskets of drugs in the United States and Canada. To explore possible

market baskets, we selected the top third of drugs for several potential population groups and

compared them. Age had the most differentiating effect on which drugs a population group uses;

we used age, gender, race/ethnicity, and insurance status to create market baskets. The first section

of this appendix documents this process in more detail.

For each market basket, we identified prices for the most common form and strength of each drug.

We weighted prices in each market basket index according to overall use of each drug for that

population. The second section of this appendix documents our methodology for working with

drug price data.

Selecting Population Groups and Their Market Baskets

In selecting potential population groups, we started with a list of attributes available in the Medical

Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) that could be reasonably expected to lead to differences in drug

use. These included age, gender, race, income, obesity, smoking, and insurance status. We identified

the drugs most commonly used by each of these groups, then compared them to identify groups

that would lead to a set of diverse market baskets. The data on utilization by these groups became

the basis for the market baskets of drugs used in this analysis.

One issue we identified in our literature review was the idea that when comparing Canadians’ drug

costs to U.S. costs, it might be more appropriate to determine drugs that are most commonly used

by Canadians and compare their prices to prices of drugs most commonly used in the United States.

The research question for this project, however, concerns the prices that United States consumers

would pay for their drugs if they bought the same drugs in Canada. For this reason, we focused on

identifying the drugs, forms, and strengths that are most commonly used in the United States.

Identifying Potential Market Baskets

As potential market baskets, we selected a group of drugs that represent a third of the prescriptions

for each potential population group. Because this list of drugs is based on prescription volume, not

total costs, inexpensive drugs will count as heavily as higher-priced drugs. Selecting a consistent

percentage of utilization across all population groups will allow for the most consistent comparisons

across population groups. We selected the cutoff of one third of prescriptions because of sample

size considerations.

MEPS collects information on prescriptions at two different levels of detail. The most aggregated

information collected is the drug name. In addition, MEPS collects for many (but not all)

prescriptions the NDC code. NDC codes specify not only the drug but also the manufacturer, the

form and the strength of a drug. There can be many NDC codes for an individual drug name,

particularly for generic drugs with multiple manufacturers.

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

15

To select the top third of drugs for each population group, we chose to rank drugs by number of

prescriptions at the drug name level. Before doing this, we cleaned drug names in MEPS to make

them more consistent, and to remove any differentiation between forms and strengths that were

included in the reported drug name (e.g., amoxil and amoxil bubblegum).

We considered but rejected the option of using NDC codes to rank-order the drugs. Because

generic drugs have multiple manufacturers as well as multiple strengths, the use of any one generic

drug is diluted across many different NDCs. Ranking by NDCs would disproportionately place

brand-name drugs in the top third of utilization. In addition, the number of observations at the

NDC level is much smaller than the number of observations at the drug name level. This makes it

more likely that drugs could make it into the top third by random chance.

Selecting Population Groups

Using the top-ranked drug names that add up to one third of total prescriptions for that group, we

ran correlations among the drugs that were common to any two subpopulations. Where correlations

are not high, it suggests that two subpopulations are using a substantially different set of drugs.

Overall, we found that age groups provided the most diverse set of drugs. In other words, the drugs

used by children are different from those used by middle-aged individuals, which are in turn

different from those used by seniors. For the other variables we tested, the differences were

generally less striking.

Age

We divided the population into six age categories: under 12, 12 to 24, 25 to 39, 40 to 54, 55 to 64,

and 65 and up. In general, there was relatively high correlation between adjoining age categories –

and lower correlations as the age separation became greater.

Figure A-1. Rank Order Correlation of Drugs Used, by Age Group

Under 12 12-24 25-39 40-54 55-64 65 and up

Under 12

12-24 0.77

25-39 0.25 0.50

40-54 -0.23 -0.34 0.09

55-64 -0.31 -0.48 -0.17 0.83

65 and up -0.38 -0.53 -0.29 0.58 0.81

Based on these correlations, we used age as a primary basis for our market baskets. We combined

two age groups (40-54 and 55-64) since their correlation is quite high (0.83). The correlation

between the 55-64 and the over 65 group is also high, but because the latter group is mostly covered

by Medicare, we kept it as a separate group. We also considered combining the two youngest

groups. However, because further examination suggests that the under 12 group often uses

different forms of drugs (e.g., liquids instead of tablets or capsules), we kept this group as a separate

market basket.

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

16

Sex

The pattern of drug use between males and females was moderately correlated (0.61). There are

biologically driven differences between some of the drugs used by males versus those used by

females. For example, the market baskets for women of childbearing age include multiple birth

control pills. As a result, we divided all the age groups described above into separate market baskets

for males and females.

Race

We established four race categories: Non-Hispanic White, African American, Hispanic, and Other.

The correlations among the patterns of drug utilization for these groups were only modest.

Figure A-2. Rank Order Correlation of Drugs Used, by Race

White African American Hispanic Other

White

African

American

0.46

Hispanic 0.55 0.46

Other 0.64 0.43 0.81

Based on these results, we created three market baskets: one based on the utilization of the African

American population, one based on the Hispanic population, and one based on the non-Hispanic

white population. The “other” race group is too small to provide reliable estimates (and is relatively

highly correlated with the Hispanic group).

Income

We divided the population into five income groups. Generally, drug use for the four lowest groups

was fairly highly correlated. The one outlier group is the high-income population. We did not use

this group as a separate market basket.

Figure A-3. Rank Order Correlation of Drugs Used, by Income

Poor Near poor Low Medium High

Poor

Near poor 0.90

Low 0.83 0.78

Medium 0.74 0.81 0.86

High 0.44 0.59 0.58 0.85

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

17

Insurance Status

We created five categories of insurance status: (1) Uninsured (not covered by insurance during the

year); (2) Private insurance (covered by private insurance during the entire year); (3) Medicare

(covered by Medicare during the entire year); (4) Medicaid (covered by Medicaid during the entire

year); and (5) Medicaid/other (covered by Medicaid during the entire year and also covered by some

other insurance for at least part of the year). The patterns of drug use are only moderately correlated

across these categories. The most distinct pattern is for those who are uninsured, presumably

because they cannot afford some of the more expensive drugs and because their health needs are

different. We created two market baskets based on these groups: one for people who had drug

insurance all year, and one for people who did not have drug insurance for any part of the year.

Figure A-4. Rank Order Correlation of Drugs Used, by Insurance Status

Uninsured Private Medicare Medicaid Medicaid/other

Uninsured

Private 0.37

Medicare 0.21 0.67

Medicaid 0.43 0.46 0.48

Medicaid/other 0.12 0.60 0.79 0.65

Health Indicators

We chose two health indicators as possible influences on drug use: obesity and smoking. For each

indicator, the sets of drugs used are similar across the two categories. Drugs used by those who are

obese are highly correlated (0.87) with drugs utilization by the non-obese. The correlation of drug

use between smokers and non-smokers is nearly as high (0.79). As a result, we did not create any

market baskets based on these groupings.

Population Groups

Based on the above analysis, we created 15 market baskets:

• Females under 12

• Females 12-24

• Females 25-39

• Females 40-64

• Females 65+

• Males under 12

• Males 12-24

• Males 25-39

• Males 40-64

• Males 65+

• Insured

• Uninsured

• Whites

• African Americans

• Hispanics

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

18

The resulting market baskets each included from 8 to 32 drugs. We have included the list of drugs

that make up the market basket for each of these groups at the end of this appendix. In addition,

we have included a consolidated list of all 106 drugs included in any market basket, with a count of

the market baskets in which each drug is included.

Working with Price Data

For each market basket, we identified prices for the most common form and strength of each drug.

Identifying prices in Canada required a matching process to ensure that we found prices for the drug

a U.S. consumer would find as the closest match for his or her drug. We then calculated a per-

prescription weighted average price for each market basket. This section provides more detail on

this process.

Matching Drug Names to Prices

Although utilization can be summarized at the drug name level, price varies by form, strength, and

manufacturer. Even when two population groups have the same drug name in their market baskets,

they will often have different usage patterns for that drug. For example, many drugs have different

dosage recommendations for children and the elderly. In addition, children are more likely than

other populations to use drugs in a liquid form.

We identified the form and strength most commonly used by each population group for each drug

in a market basket. IMS then extracted all retail prescription transactions occurring in Oct-Dec 2005

for all NDC codes associated with that form and strength of the drug for which valid price and

quantity information was reported. We used these data to calculate an average price per pill (or, for

drugs that are not in pill form, the price per unit), defined as summed price across all dispensed

prescription transactions divided by summed quantity.

We then converted these per-unit prices into per-prescription prices, in order to standardize across

different drugs that have different numbers of pills or other units per prescription. To do this, we

used MEPS to determine the median number of pills (or other units) in a prescription for the

selected form and strength of each drug for each population group. We then multiplied the price

per unit by the median units per prescription to arrive at a standardized per-prescription price.

In the case of drugs sold in inhalers, we did not use this standardization process. Instead, we

defined the per-prescription price as summed price across all dispensed prescription transactions

divided by total number of dispensed prescriptions.

Matching with Canadian Drugs

We have tried to assure that the match between our U.S. market baskets and Canadian market

baskets is as close as possible, while still representing the utilization of the population groups we

identified. In the majority of cases, we were able to find an exact match by drug name, form, and

strength between the United States and Canada. There are four general categories of cases for

which that was not possible: 1) Drugs sold under a different name in Canada; 2) Drugs with

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

19

different brand/generic status; 3) Drugs sold in different dosages or release forms; and 4) drugs not

marketed in Canada.

Drugs sold under a different name

We first looked for an exact match by drug name, form, and strength between the United States and

Canada. When an exact match by drug name was not available in Canada, we looked to match drugs

by chemical entity, brand-name status, and in the case of brand name drugs, by manufacturer.

Figure A-5 shows the seven brand name drugs that match by all factors except trade name.

Figure A-5. On-Patent Drugs with Same Manufacturers but Different Names

Chemical ingredient U.S. Product

(from MEPS)

Canadian Product

Amoxicillin and clavulanate potassium Augmentin Clavulin

Desloratadine Clarinex Aerius

Divalproex sodium Depakote Epival

Ethinyl estradiol and norelgestromin Ortho-Evra Evra

Ethinyl estradiol and norethindrone Ortho-Novum Ortho 1/35

Escitalopram Lexapro Cipralex

Certirizine Zyrtec Reactine

6

For six generic drugs and branded generics, we were able to find a Canadian match with the same

active ingredient but with different names and manufacturers. Figure A-6 shows the Canadian

products we used as matches for these drugs.

Figure A-6. Generic Drugs with Different Names and Manufactures in the U.S. and Canada

Chemical ingredient U.S. Product

(from MEPS)

Canadian Product

Albuterol Albuterol Salbutamol

7

Spironolactone Spironolactone Novo-Spiraton

Ethinyl estradiol and desogestrel Apri Ortho-cept

Ethinyl estradiol and norethindrone Necon Brevicon, Loestrin, Minestrin

8

Amoxicillin Trimox Amoxicillin

Levothyroxine Levoxyl Eltroxin

9

6

Reactine is available over-the-counter in Canada.

7

Salbutamol sulfate is the name recommended by the World Health Organization for the drug known as Albuterol

sulfate in the U.S.

8

These three drugs all have the same ingredients as Necon and all have very similar prices in Canada. We propose to

use a simple average of their prices.

9

In the United States, branded generic versions of levothyroxine include Levoxyl, Unithroid, Levo-T, Levolet, and

Novothyrox. In the United States, Levoxyl is the only one common enough to appear in our market baskets. In

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

20

We consider all of these matches to be extremely close matches that are equivalent across the two

countries’ market baskets.

Drugs with different generic status

We found one drug that is available as a generic in the United States and not in Canada: Enalapril.

For this drug, we kept the generic version in the U.S. market baskets, but substituted the brand-

name equivalent (Vasotec) in the Canadian market baskets. This is a less equivalent match than the

cases describe above, because generics and brand drugs tend to have different pricing strategies

within each country, and price comparisons between the two countries behave differently for brands

and generics. Specifically, the ratio between the Canadian price and the U.S. price tends to be higher

for generics than for brands. However, because Vasotec is the closest possible match that a U.S.

consumer would find if they looked for Enalapril in Canada, we believe using it is the best strategy

in this case. This drug is included in one market basket.

In MEPS, all insulin appears to be labeled as insulin, regardless of manufacturer. We have used

Humulin to represent insulin in both the U.S. and Canadian market baskets.

Drugs sold in different dosages or release forms

There were several drugs on our list at a dosage level not available in Canada. When possible, we

used another dosage level that is available in both countries as a substitute in both the U.S. and

Canada market baskets.

For the five cases shown in Figure A-7, we were able to substitute the same dosage levels for both

U.S. and Canadian market baskets.

Figure A-7. Dosage Levels Substituted in U.S. and Canadian Market Baskets

Drug Original Strength as

determined by MEPS

(not available in Canada;

not used in either market

basket)

Substitution

Strength

(both U.S. and

Canada)

Market Baskets

Affected

Allegra 180 mg 60 mg 10

Ibuprofen 800 mg 600 mg 2

Levoxyl/Eltroxin 0.125 mg 0.15 mg 1

Prednisone 10 mg 5 mg 5

Prednisone 20 mg 50 mg 1

Canada, versions of levothyroxine include Euthyrox, Eltroxin, and Levo-T. Eltroxin is the most commonly used of these

three Canadian drugs.

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

21

For four drugs, there is no dosage that is available in both countries. For these drugs, we used the

original strength in the U.S. market baskets and substituted the closest strength available in Canada

in the Canadian market baskets, as shown in Figure A-8.

Figure A-8. Dosage Levels Substituted in Canadian Market Baskets Only

Drug Original Strength as determined by

MEPS

(not available in Canada;

used in U.S. market basket)

Substitution

Strength (only in

Canada)

Market Baskets

Affected

Amoxil 400 mg/5ml 250mg/5ml 1

Flonase .05% 50 mcg 5

Flovent 44 mcg 50 mcg 1

Albuterol 90 mcg 100 mcg 14

In general, the relationship between dosage and price is not linear. That is, the price of a single 100

mg pill is rarely equal to the price of two 50 mg pills of the same drug. The differences in dosage for

these drugs should not substantially affect the price comparisons between the two countries. Again,

if a U.S. consumer were looking for these drugs, these dosages are the options they would have in

Canada.

Drugs not available in Canada

There were five drugs on our list from the United States that are not available in Canada: Toprol

XL, Glucotrol, hydrocodone with acetaminophen, Lotrel, and Vicodin. We propose dropping all of

these drugs except Toprol XL from the U.S. market baskets because no close match is available. In

addition, we propose dropping Softclix, a testing device that was listed in the MEPS drug data that is

not available in Canada. An alternative would be to include the U.S. price in the Canadian market

basket, because consumers seeking these drugs would have to buy them in the United States. This

strategy would decrease any potential differences between the two market baskets. In the case of

Toprol XL (metoprolol succinate), we have substituted Lopressor SR (metoprolol tartrate) in the

Canadian market baskets.

Figure A-9. Drugs Not Available in Canada

Drug or Device Market Baskets

Affected

Toprol XL 9

Glucotrol 1

Hydrocodone and Acetaminophen 3

Lotrel 2

Vicodin 1

Softclix 10

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

22

Weighting

The process outlined above provides a representative price per prescription for each drug name in a

population group’s market basket. We then combined these prices into a single index value for each

market basket. We calculated each population group’s index as the average price per prescription,

weighted by the volume of prescriptions for that group, as determined by MEPS data.

Because the research question for this project concerns the prices that U.S. customers would pay if

they bought their drugs in Canada, we used these U.S.-based volume weights for both U.S. prices

and Canadian prices.

Currency conversion

To convert Canadian prices into U.S. dollars, we used the average exchange rate for the fourth

quarter of 2005, which was $1.1732 Canadian for $1.00 U.S..

10

Because the focus of this project is

on the prices that U.S. customers would face in Canada, we did not consider using purchasing power

parity or other measures that would better represent the cost of Canadian drugs to Canadian

consumers.

Sensitivity to Drug Substitutions

To explore the sensitivity of our results to the substitution we made in the market baskets, we

calculated what the differences between U.S. and Canada prices would have been if we had excluded

two drugs: Zyrtec and Toprol XL. Zyrtec is a on on-patent prescription drug in the United States

that is available over-the-counter in Canada as Reactine, and Toprol XL is a drug for which we used

a close substitute, Lopressor SR, as the Canadian match.

In all market baskets, excluding these two drugs makes the difference between the two countries’

prices smaller. In thirteen of the fifteen market baskets, the difference is 2.2 percentage points or

less (regardless of payer). The exception is the market baskets for children under 12. Because

children take fewer drugs, these market baskets are smaller than the other market baskets – the lists

of the top third of drugs include just ten drugs for girls and eight drugs for boys. Zyrtec accounts

for about a tenth of the prescriptions included in each of these market baskets, and its exclusion

gives generic drugs a larger share of each market basket. The exclusion of Zyrtec causes the average

U.S. price per prescription for these market baskets to fall by about three dollars (6 to 10 percent),

while the average Canadian price per prescription rises slightly (1 to 4 percent). The result is a larger

drop in the relative difference between U.S. and Canadian prices for these two market baskets. This

is particularly notable for prescriptions purchased with third party coverage, where the difference

between the United States and Canada falls to 21.5 percent for girls and 23.5 percent for boys.

10

http://www.bankofcanada.ca/en/rates/exchange.html

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

23

Figure A-10. Sensitivity of Difference Between U.S. and Canadian Price to Inclusion of

Zyrtec and Toprol XL

With Third-Party Coverage Without Third-Party Coverage

Including

Toprol, Zyrtec

Excluding

Toprol, Zyrtec

Including

Toprol, Zyrtec

Excluding

Toprol, Zyrtec

Females under 12

-30.1% -21.5% -46.9% -41.5%

Females 12-24

-39.9% -38.6% -49.5% -48.4%

Females 25-39

-47.0% -46.0% -55.0% -54.1%

Females 40-64

-40.9% -39.5% -48.7% -47.4%

Females 65+

-37.3% -36.0% -44.0% -42.7%

Males under 12

-31.0% -23.5% -46.3% -41.1%

Males 12-24

-33.4% -31.5% -44.7% -43.1%

Males 25-39

-42.1% -40.8% -50.9% -49.7%

Males 40-64

-35.9% -34.8% -43.9% -42.9%

Males 65+

-30.6% -29.0% -38.9% -37.4%

Insured

-40.3% -38.7% -48.4% -46.9%

Uninsured

-31.4% -29.9% -40.6% -39.3%

White

-39.0% -37.1% -47.2% -45.4%

African Americans

-34.9% -32.9% -43.3% -41.5%

Hispanics

-33.6% -31.3% -44.2% -42.3%

mean

-36.5% -34.1% -46.2% -44.2%

median

-35.9% -34.8% -46.3% -42.9%

Figure A-11. Zyrtec And Toprol XL as Share of Utilitzation Included in Market Baskets

Zyrtec Toprol XL

F 12U 9.4% -

F 12-24 3.2% -

F 25-39 3.6% -

F 40-64 2.3% 2.8%

F 65+ - 4.9%

M 12U 10.7% -

M 12-24 6.0% -

M 25-39 5.3% -

M 40-64 - 4.8%

M 65+ - 4.6%

Insured 2.9% 3.1%

Uninsured - 3.9%

White 2.5% 3.7%

African Americans 2.6% 2.6%

Hispanics 2.2% 2.1%

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

24

Changes in Drug Use Since 2003

The MEPS data we used are from 2003. Because there are so many ongoing changes in the market,

and because more recent data are not available for all the specific subpopulations, it is impossible to

thoroughly update our sample to reflect current drug utilization. Rather than tinkering with some

drugs and leaving others untouched, we kept utilization as-is in the MEPS data. The exception is

drugs that are no longer on the market. We removed one off-market drug, Vioxx, from our market

baskets and adjusted weights accordingly.

Figure A-12 gives a snapshot of how rankings changed in IMS data for the most popular drugs from

2003 to 2005. Our market baskets include most of these top drugs -- 18 of the 20 top drugs in 2005,

and 19 of the top 20 drugs in 2003. Levothyroxine is one top 20 drug in 2005 that is not in any of

our market baskets. It was not on the top 20 in 2003, and in fact saw nearly 200 percent growth in

utilization between 2004 and 2005 alone. Because of this recent rapid growth, it seems reasonable

that levothyroxine was not in the top third of prescriptions for any of our groups in 2003.

Ambien is the one drug on both years’ top 20 lists that is not in any of our market baskets.

Utilization for Ambien was not high enough to be included in the top third of drugs for any single

population group in the 2003 MEPS data.

Figure A-12. Top 20 Drugs in 2003 and 2005

2005

Rank

2003

Rank Product

Market Baskets

Including this Drug

1 1 Lipitor 10

2 3 Hydrocodone and Acetaminophen (Mallinckrodt) 3

3 4 Norvasc 9

4 6 Toprol-XL 9

5 2 Synthroid 11

6 5 Zoloft 7

7 7 Hydrocodone and Acetaminophen (Watson) 3

8 10 Amoxicillin 9

9 >20 Lexapro 2

10 11 Albuterol 14

11 8 Zocor 9

12 >20 Nexium 6

13 >20 Levothyroxine 0

14 18 Ambien 0

15 >20 Singulair 7

16 9 Prevacid 8

17 >20 Plavix 2

18 12 Zithromax Z-Pak 11

19 19 Fosamax 4

20 14 Zyrtec 11

>20 13 Premarin 7

>20 15 Atenolol 10

>20 16 Levoxyl 8

>20 17 Celebrex 9

>20 20 Allegra 10

Source: IMS 2003a and IMS 2005.

NORC at the University of Chicago Task Order HHSP233000007T

25

Prescriptions vs. Spending

We used the number of prescriptions for each drug in each population group to determine the most

popular drugs and to weight the results. We selected this measure because we wanted our market

baskets to include both inexpensive and expensive drugs, as long as they were widely used.

Another option would have been to use total spending for each drug. Our concern was that this

would skew our sample to include more costly drugs, with disproportionately large price differences.