Internet Society

Perspectives on Internet

Content Blocking:

An Overview

March 2017

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

2

internetsociety.org

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

3

internetsociety.org

Table of Contents

Foreword ....................................................................................................................................................................................4

Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................5

Sidebar: Filtering, Blocking, or Censorship? ................................................................................................................ 5

Motivations for Blocking Content ...................................................................................................................................... 7

Other Types of Motivations for Blocking Content ..............................................................................................7

Overview of Content Blocking Techniques ......................................................................................8

Where Does Content Blocking Occur? ...................................................................................................................... 10

Sidebar: Endpoint Content Blocking ....................................................................................................................................11

Content Blocking Types Evaluated .............................................................................................................11

IP and Protocol-Based Blocking ......................................................................................................................................... 12

Deep Packet Inspection-Based Blocking ................................................................................................................ 14

URL-Based Blocking ............................................................................................................................................................................ 15

Sidebar: Encryption, Proxies, and Blocking Challenges ..............................................................................15

Platform-Based Blocking (Especially Search Engines) ............................................................................. 17

Sidebar: Blocking On Other Platforms .............................................................................................................................18

DNS-Based Content Blocking ................................................................................................................................................. 19

Sidebar: DNS Overview ...................................................................................................................................................................... 19

Content Blocking Summarized .......................................................................................................................21

Conclusion ............................................................................................................................................................................22

Recommendations ............................................................................................................................................................................. 22

Sidebar: Circumventing Content Blocking ................................................................................................................22

Minimizing Negative Effects ................................................................................................................................................. 23

Glossary ......................................................................................................................................................................................24

For Further Reading .................................................................................................................................................... 26

Internet Engineering Task Force Technical Documents ....................................................................... 26

Policy, Survey, and Background Documents ..................................................................................................... 26

Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................................................ 27

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

4

internetsociety.org

Foreword

The use of Internet blocking by governments to prevent access to illegal content is a worldwide

and growing trend. There are many reasons why policy makers choose to block access to some

content, such as online gambling, intellectual property, child protection, and national security.

However, apart from issues relating to child pornography, there is little international consensus

on what constitutes appropriate content from a public policy perspective.

The goal of this paper is to provide a technical assessment of different methods of blocking

Internet content, including how well each method works and what are the pitfalls and problems

associated with each. We make no attempt to assess the legality or policy motivations of

blocking Internet content

1

.

Our conclusion, based on technical analyses, is that using Internet blocking to address illegal

content or activities is generally inefficient, often ineffective and generally causes unintended

damages to Internet users.

From a technical point of view, we recommend that policy makers think twice when considering

the use of Internet blocking tools to solve public policy issues. If they do and choose to pursue

alternative approaches, this will be an important win for a global, open, interoperable and

trusted Internet.

1 Readers interested in legal assessments of content blocking could visit the following resources:

• Article 19: https://www.article19.org/data/files/medialibrary/38657/Expression-and-Privacy-Principles-1.pdf

• Council of Europe:

http://www.coe.int/en/web/freedom-expression/study-filtering-blocking-and-take-down-of-illegal-content-on-the-internet

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/deed.en_US

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

5

internetsociety.org

Introduction

The Internet’s evolution into a worldwide societal phenomenon has much to credit to the

content and services that have taken advantage of the network’s unique architecture. Entire

economies depend on cross-border content flows. Daily innovations have the potential to

disrupt entire industries. The Internet is now a critical part of democratic processes and policy

discussions. Personal relationships are created and broken online.

The trend is not slowing down. According to estimates

2

, Global Internet traffic in 2020 will be

equivalent to 95 times the volume of the entire global Internet in 2005. The number of devices

connected to IP networks will be three times as high as the global population in 2020.

Yet, the Internet also contains content that policy makers, legislators, and regulators around the

world want to block. From blocking foreign gambling websites in Europe and North America to

blocking political speech in China, the use of Internet content blocking techniques to prevent

access to content considered illegal under certain national laws is a worldwide phenomenon.

Public policy motivations to block Internet content are diverse, ranging from combating

intellectual property infringement, child abuse material and illegal online activities, to protecting

national security.

The objective of this paper is neither to assess such motivations nor to qualify whether a

certain type of blocking is good or bad from an ethical, legal, economic, political or social

perspective. Instead, we will provide a technical assessment of the benefits and drawbacks of

the most common blocking techniques used to prevent access to content deemed illegal. The

aim is to help readers understand what each technique can, and cannot, block, along with the

side effects, pitfalls, trade-offs, and associated costs.

Our conclusion is that the use of Internet blocking to address illegal content is generally

inefficient, often ineffective, and prone to cause unintended collateral damages to Internet

users, summarized further in the table on page 6.

From a technical point of view, we call on policy makers to

think twice about the use of such measures and invite them

to prioritize their responses focusing primarily on alternative

measures that focus on addressing the issue at the source

(see more detailed recommendations at the end of this paper,

including guidance on how to minimize the negative effects of

such measures.).

It should further be noted that this paper is not focusing on

blocking measures when implemented for regular network

management or security reasons (e.g. addressing spam,

malware). In such cases, some of the same tools we describe in

this paper can often be effective to achieve the intended aims.

2 Cisco® Visual Networking Index: http://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/solutions/collateral/service-provider/visual-networking-index-vni/complete-

white-paper-c11-481360.html

Sidebar:

Filtering, Blocking, or Censorship?

When describing Internet filtering, terms such

as “filtering,” “blocking,” “shut down,” and

“censorship” all come up (along with several

others). From the point of view of the user, the

term chosen is less important than the effect:

some part of the Internet is inaccessible. For

policy makers and digital activists, choosing

a particular term is usually more driven by

semantic overtones than technical correctness.

The word “censorship” carries a strong negative

connotation, while “filtering” seems a more

gentle and harmless operation, like removing

unwanted seeds from a glass of orange juice.

We have chosen to use “blocking” as a simple

and straightforward term throughout this paper.

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

6

internetsociety.org

The table below summarizes the major drawbacks associated with Internet content blocking

based on public policy considerations:

Issue Details

Easily

circumvented

All of the techniques described in this paper can be evaded by sufficiently motivated users.

As users discover the many ways to work around content blocking, the effectiveness of the

blocking will be reduced.

Doesn’t solve

the problem

Content blocking does not remove the content considered illegal. In some cases, a national

ban may be incompatible with international norms, but where there is wide-ranging

agreement on illegal content, the best solution to the problem is removal of the content at

the source.

Causes collateral

damage

When both legal and illegal content share the same IP address, domain name, or other

characteristics, content blocking will block access to everything: illegal and legal. For example,

blocking access to a single Wikipedia article using DNS filtering would also block millions of

other Wikipedia articles.

Puts users

at-risk

When local Internet service is not considered reliable and open, Internet users may use

alternative and non-standard approaches, such as downloading software that redirects their

traffic to avoid filters. These makeshift solutions subject users to additional security risks.

Encourages lack

of transparency

A transparent and trusted environment is important to the successful operation of the

Internet. Content blocking eliminates this transparency, undermining the open nature of the

network and causing distrust of public information sources.

Drives service

underground

When content blocking becomes widespread, “underground” services and alternative

network overlay structures will be established, taking the content out of easy view of law

enforcement. For example, content may move to the Dark Web or users may tunnel traffic

through VPNs.

Intrudes on

privacy

Several types of content blocking require the examination of the user’s traffic, including

encrypted traffic. When third parties monitor what Internet users do, record transactions, or

break the basic encryption security of the Internet, users’ privacy is violated.

Raises human

rights and

due process

concerns

Implemented without due regards to notions such as necessity and proportionality, content

blocking has the potential to cause significant collateral damage, restriction of free and open

communications, and put limits on the rights of individuals.

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

7

internetsociety.org

Motivations for Blocking Content

In this paper, we focus on blocking based on public policy considerations and its effects on

the Internet and Internet users (see side-bar for other motivations for content blocking)

Blocking based on public policy considerations is used by national authorities to restrict access

to information (or related services) that is either illegal in a particular jurisdiction, is considered a

threat to public order, or is objectionable for a particular audience.

For example, there’s a common desire in most countries

to block access by children to obscene material, or access

by anyone to child abuse material. Depending on the local

legal environment, content may also be blocked if it violates

intellectual property laws, is considered a threat to national

security, or is prohibited for cultural or political reasons.

One of the challenges leading national authorities to use

Internet content blocking measures is that different actors

delivering the source’s content to consumers may be in

different countries, with different laws covering what is and

is not “illegal content”. Moreover, the global environment of

the Internet makes stopping the source of illegal content

more complicated than simply shutting down a local server.

For example, the person providing the content, the servers

hosting the content, and finally the domain name pointing

to the content may in three different countries, all beyond

the jurisdiction of an individual national authority. This

highlights the importance of cooperation across jurisdictions

and the need for close coordination with non-governmental

stakeholders.

Other Types of Motivations for Blocking Content

In this paper, we focus on blocking based on public

policy considerations, but there are two other common

reasons that network blocking is put into place. The

first is preventing or responding to network security

threats. This type of blocking is very common. For

example, most enterprises attempt to block malware

from entering their networks. Many Internet Service

Providers (ISPs) are putting in blocks for malicious

traffic exiting their networks, such as from hijacked

IoT devices (e.g. web cams). Email filtering is extremely

common, and includes blocking unwanted bulk email

as well as malicious email such as phishing messages.

These types of blocking are not discussed in this paper.

A second reason for blocking is managing network

usage. A growing area of Internet content blocking is

based on network, bandwidth, or time management

requirements, rather than particular types of content.

For example, employers may wish to restrict access to

social networking sites for their employees while still

offering Internet access at the desktop. ISPs may block

or permit, throttle or accelerate certain content based

on contracted services. Network usage management

is rarely a public policy issue, except when it steps

into the area of anti-competitive behavior. Readers

interested in Network Neutrality will find references in

For Further Reading, page 26.

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

8

internetsociety.org

Overview of Content Blocking

Techniques

Each technique has both technical and policy limitations and consequences that need to be

considered when any type of content blocking is being proposed. The goal of this paper is to

provide a common way to evaluate their efficacy and side effects. Readers interested in a more

technical discussion of content blocking will find references to IETF technical documents in

For Further Reading, page 26.

This paper will assess the following types of content blocking:

• IP and Protocol-based blocking

• Deep Packet Inspection-based blocking

• URL-based blocking

• Platform-based blocking (especially search engines)

• DNS-based blocking

We chose these five types of blocking because they target the elements of a typical end-user

cycle of finding and retrieving information, including the use of a search engine and viewing

information with a web browser or similar tool. This cycle is very familiar to policy makers,

themselves Internet users, and these are the operations that most blocking based on public

policy considerations tries to disrupt.

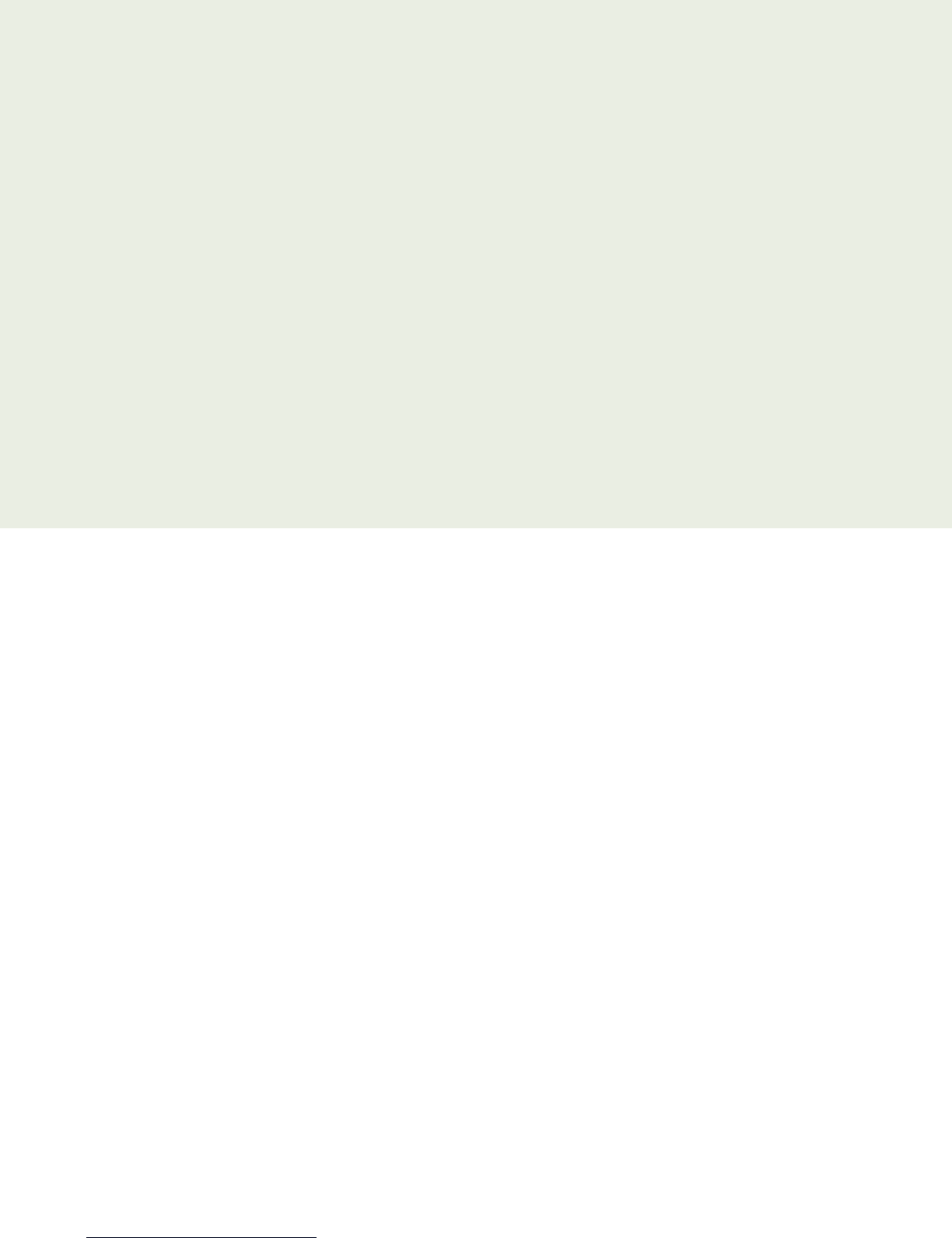

In the diagram to the right, we show the steps that a typical Internet user might take to find

information, as well as the kinds of blocks that have been used to disrupt this cycle when

blocking based on public policy considerations is implemented. In our diagram, an Internet user

searches for some type of content using a search engine (step 1), a common starting point. The

search engine returns a set of results (step 2), and the user selects one and clicks on the result

(step 3). One type of blocking, Platform-based Blocking, is used to disrupt this part of the cycle

by blocking some results coming back from the search engine.

The user’s computer tries to find the server hosting the data in the Internet’s DNS (steps 4 and

5). A second type of blocking, DNS-based Blocking, is used to disrupt this part of the cycle.

Then, the user’s web browser tries to connect to the server (step 6). This part of the cycle can

be blocked using three other types of blocking: IP and Protocol-based Blocking, URL-based

blocking, and Deep Packet Inspection-based blocking.

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

9

internetsociety.org

Overview: steps for how information

is retrieved and blocked online

User

searches for

“bomb”

using search

engine.

If blocking is

happening,

this is what

the user

might see

instead:

With Search Filtering

and other

platform-based

blocking, the results

are kept out of the

user’s hands, if they

use the specific

engine.

With DNS-based

blocking, the user’s

computer cannot find

the server, so it

cannot connect to

see the web page.

The user will see

“server not found”.

With IP and Proto-

col-based blocking,

the connection to

the server with

IP = 192.0.2.222 is

blocked. All content

on the server is

unavailable whether

intended or

unintended.

With URL-based

blocking, the trac

is blocked if the URL

is found on the

block list.

With Deep Packet

Inspection-based

blocking keywords in

the web page may

trigger an interrup-

tion in trac. There is

a high risk to block

unintended content.

No Results Found

For “bomb”

Server Not

Found

The Connection

Has Timed Out

This Site Has

Been Blocked

By The Network

Administrator

The Connection

Was Reset

Request from user’s

PC to example.com

server

To: 192.0.222

Get: http://

example.com/bomb

From:

192.0.222

Get:

Request from

example.com

server to user

RESOLVER

User clicks

on a result

(http:/

example.com/

bomb)

User’s

computer

looks up

“example.com”

in DNS so it

can connect

to the web

server.

User’s

web browser

connects to the

“example.com”

web server and

requests the

specific web

page the user

clicked on.

Without filtering,

user sees a result

example.com = 192.0.2.222

DNS

example.com?

1234567

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

10

internetsociety.org

Of course, the Internet is much more than search and web browsers, and many of the

techniques discussed below are effective at blocking more than web pages. For example, use

of VPN services to encrypt and hide traffic can often be blocked using a combination of Deep

Packet Inspection-based blocking and IP/Protocol-based blocking.

These types of blocks may be applied very specifically (such as a particular document on a

particular web site) or very generically (such as “material on an issue” or “Voice over IP services”).

Where Does Content Blocking Occur?

Many of the content blocking techniques discussed here can be used at different points, as

shown in the table below.

National level When mandated by government policy, all traffic entering or leaving a country may be subject

to content blocking. This requires tight control of all cross-border connections by means of a

national gateway or national firewall, or could be imposed on all carriers and ISPs in a country

in parallel.

Carrier and

ISP level

Individual telecommunications carriers, including mobile carriers and traditional ISPs, may install

blocking tools.

Local network

level

End-user laptop and desktop devices are typically connected to home, corporate, or school

networks rather than directly to a carrier. These local networks may have blocking installed,

usually based on network management or security policy rather than governmental policy.

Endpoint level Software may be installed directly on end-user computers that enforces the blocking policy.

This is very commonly used in both home and corporate networks, usually for security reasons

but also for network management or parental control reasons.

Note that in the case of blocking based on public policy considerations, the majority of

measures are being applied at the first two levels (national, carrier, and ISP levels).

The diagram below summarizes some of the main locations where blocking can occur, and

which types of blocking can occur at each point.

Internet Content blocking

can occur at many points

Endpoint security software,

such as malware or parental

controls, can also be used to

block content.

A network-based

security appliance

or proxy may see

trac and can

block according

to policy.

This may be on the

local network or

upstream at the

local ISP.

Company,

Home, or

School

Network

User’s

Internet

Service

Provider

Internet

Hosting

or Cloud

Provider

Search

Engine

Provider

DNS

RESOLVER

DNS

SERVER

ISPs often run DNS

resolvers which can

do DNS blocking.

DNS blocking can also be

accomplished by removing

the name entirely from all

DNS servers (such as by

court order).

This is where the

content aimed

for blocking is

actually located.

Search filtering may

be global of specific

to request from a

geographic region.

GOOGLE

YAHOO!

BAI

BING

2345

2345

5

4

3

2

2

1

1

2

Deep Packet Inspection

URL Blocking

DNS Blocking

Search Filtering

Internet Blocking Techniques

IP Blocking

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

11

internetsociety.org

The five common content blocking types are distinct in what they block and how they operate.

Below, the content blocking techniques are discussed in greater detail and are evaluated

against four specific criteria

3

:

Which sets of users and Internet services are affected by

this technique? What sets are unaffected?

How specific is the technique in preventing access to

particular content? How much collateral damage (unintended

blockage) is created by this blocking technique?

How effective is this technique in blocking content? What

types of users and content providers are able to circumvent

this technique?

What are common side-effects of this technique? What

technical issues are caused by this technique? What non-

technical issues, such as impact on trust and fundamental

rights, are raised in using this technique?

3 These criteria are taken from Internet RFC 7754, “Technical Considerations for Internet Service Blocking and Filtering.”

Sidebar:

Endpoint Content Blocking

This paper focuses on Internet content blocking based on public policy considerations.

Yet, it is important to note that one of the most effective ways to block undesired content is through the use of software

installed on the user’s device, commonly called the “endpoint” because it is the last point of the connection between the user

and the Internet. Most computer users make use of endpoint software to block malware (viruses, Trojan horses, and phishing),

whether installed personally or by an organizational IT group.

Endpoint content blocking software is also used by organizations to block content for other reasons. For example, libraries often

install this type of software on public computers to block the viewing of pornography by patrons, and parents may use it to

block unwanted content from their children.

Endpoint content blocking may use many of the techniques described in this paper, including content scanning, URL

categorization, IP address blocking, and DNS interception. Generally, the blocking and analysis occurs on the actual endpoint.

However, vendors of this software are increasing also using cloud-based tools including content scanning and DNS-based

blocking, in cooperation with a small amount of endpoint software. In these newer solutions, some or all of the Internet content

may pass through a cloud-based service. The advantage of moving the decision-making to the cloud is that endpoints do not

have to be constantly updated, and the performance impact of evaluating content is moved from the user’s computer or smart

phone to an easily scaled cloud of computers. When traffic is routed through a third party, though, this also creates privacy

issues by making the content available to the third party and, if poorly implemented, security issues arise well.

Content Blocking Types Evaluated

1

3

4

2

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

12

internetsociety.org

IP and Protocol-Based Blocking

IP-based blocking places barriers in the network, such as firewalls, that block all traffic to a set

of IP addresses. Protocol-based blocking uses other low-level network identifiers, such as a TCP/

IP port number that can identify a particular application on a server or a type of application

protocol. These simplest approaches to blocking content don’t actually directly block content-

they block traffic to known IP addresses or TCP/IP ports or protocols associated with some

content or an application. IP and protocol-based blocking may also be done by software on

user’s computers, typically for network security purposes.

For example, if the goal was to block all content hosted in the mythical country of Elbonia, IP

blocking could be used if the set of all IP addresses hosting content in Elbonia were known.

Similarly, if the goal was to block all VPN services (which are used to encrypt traffic and hide

both the destination and the content), protocol-based blocking could be used to stop VPN

services using well-known protocols or TCP/IP port numbers.

Internet

IP1

IP2

IP-based

content

block

List of IP

addresses to

be blocked

IP1 on the list

IP2 NOT on the list

IP-based blocking

can usually occur at the

enterprise or the ISP level.

IP and Protocol-Based Blocking

= “Access denied to user. Content blocked”

= “User was able to view the content”

In IP and Protocol-based blocking, the blocking device has a list of IP

addresses to block called the "block list". Any attempt to connect to a

server with an IP address on the block list will be interrupted.

With IP and Protocol-based blocking, a server that has both "bad" (bomb)

and "good'' (kitten) content will be unavailable, no matter what content is

requested, when the IP address of that server is on the block list.

Similarly, a server that is NOT on the block list will be accessible, without

regard to the type of content on the server.

IP1

IP2

WWW

Server

WWW

Server

No content from this

server is blocked since

this IP is not on the list.

Even content we might

want blocked.

ALL content is blocked

since this IP is on the list,

including unintentional

content.

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

13

internetsociety.org

A variation on IP blocking is throttling of traffic. In this scenario, not all traffic is blocked, only

a certain percentage. Users may perceive the service as very slow, or as simply going “up and

down.” This can be used to discourage users from using a service by making it seem unreliable,

or encourage the use of alternative services, without revealing that blocking is occurring.

(This can also be done for network and bandwidth management reasons at both the ISP or

enterprise level.)

Both IP and Protocol-based blocking use devices that sit between the end-user and the

content, and thus requires the blocking party (such as the user’s ISP) to have complete control

over the connection between the end-user and the Internet. A user who is not “behind” the

blocking device, or who uses technology such as a VPN that conceals the true destination of

their traffic, will not be affected by this type of blocking.

Generally, IP blocking is a poor filtering technique that is not very effective, is difficult to

maintain effectively, has a high level of unintended additional blockage, and is easily evaded by

publishers who move content to new servers (with new IP addresses).

IP blocking also does not work when information providers use content delivery networks

(CDNs), since the IP addresses of the information are highly dynamic and constantly changing.

4

CDNs also use the same IP address for many different customers and types of content, causing

a high level of unintended service interruption.

IP and protocol blocking work better when used to block specific applications, rather than

specific content. For example, VPN traffic may be blocked by TCP/IP port and protocol blocks,

combined with IP address blocks of known public VPN services. This is a common and highly

effective technique.

IP blocking is also most effective when the content is hosted in a particular server in a

specific data center, or a very specific set of files are of concern. IP-based blocking is not very

effective for larger hosting services distributed across many data centers or which use content

distribution networks (CDNs) to speed access.

4 A content distribution network is a large, geographically distributed network of servers that speed the delivery of web content to Internet

users. Large CDNs have hundreds of thousands of servers in many countries to give faster access to their customers’ content. CDNs store copies

of their customers’ text, image, audio, and video content in their own servers around the “edges” of the Internet, so that user requests can be

served by a nearby CDN edge server rather than the customer’s centralized servers.

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

14

internetsociety.org

Deep Packet Inspection-Based Blocking

Deep Packet Inspection (DPI)-based blocking uses devices between the end user and the rest

of the Internet that filter based on specific content, patterns, or application types. This type

of network blocking is computationally very intensive and thus costly, because all content

must be evaluated against blocking rules. DPI blocking may also be done by software on user’s

computers, typically for network security purposes.

DPI blocking requires some type of signature or information about the content to be effective.

This may be keywords, traffic characteristics (such as packet sizes or transmission rates),

filenames, or other content-specific information. DPI blocking is used very effectively to block or

throttle certain applications (such as peer-to-peer file sharing or Voice over IP [VoIP] traffic) and

data file types (such as multimedia files).

Deep Packet Inspection

can usually occur at the

enterprise or the ISP level.

Internet

Deep Packet Inspection-Based Blocking

Deep Packet

Inspection

block

WWW

Server

Because

this content

is on the block

list, access

is denied

Since neither

of these are

on the list they

are not blocked.

However, the

operator might

have wanted

to block the

dynamite

anyway.

In Deep Packet Inspection (DPI)-based blocking, the blocking device has a list of content to block,

which it can identify through keywords or other techniques (including image matching). Any

attempt to download unencrypted content that matches the list will be interrupted.

With DPI, both false positives (blocking content incorrectly) and false negatives (failing to block

content as intended) are common. DPI is also dicult to do properly when the trac is encrypted.

In the diagram here, the bomb has been blocked because it matches the content. However, the

dynamite was not blocked, even if the operator of the DPI device wanted to block it, because the

dynamite did not match the content block list.

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

15

internetsociety.org

DPI blocking is very commonly used in enterprises

for data leakage protection systems, anti-spam

and anti-malware (anti-virus) products, and traffic

prioritization (such as boosting the priority of enterprise

videoconferencing) network management. However, it

can also be used for more policy-based blocking purposes.

For example, use of VoIP services not provided by the

national telecommunications carrier are often regulated

or restricted, and DPI blocking is effective at enforcing

those restrictions.

DPI blocking uses devices that can see and control

all traffic between the end-user and the content, so

the blocking party (such as the user’s ISP) must have

complete control over an end-user’s connection to the

Internet. When the traffic is encrypted, as it often is, DPI

blocking systems may no longer be effective. These are

discussed in greater detail in the sidebar “Encryption,

Proxies, and Blocking Challenges” to the right.

DPI blocking is generally an effective technique at

blocking certain types of content that can be identified

using signatures or other rules (such as “block all Voice

over IP traffic”). DPI blocking has been much less

successful with other types of content, such as particular

multimedia files or documents with particular keywords

in them. Because DPI blocking examines all traffic to end

users, it is also quite invasive of end user privacy.

The overall efficacy of DPI blocking varies widely

depending both on the goals and the specific DPI tools

being used. Generally, DPI tools are most effective in

network management and security enforcement, and are

not well-suited for policy-based blocking.

URL-Based Blocking

URL-based blocking is a very popular blocking method,

and may occur both on the individual computer, or in

a network device between the computer and the rest

of the Internet. URL blocking works with web-based

applications, and is not used for blocking non-web

applications (such as VoIP). With URL blocking, a filter

intercepts the flow of web (HTTP) traffic and checks the

URL, which appears in the HTTP request, against a local

database or on-line service. Based on the response, the

URL filter will allow or block the connection to the web server requested.

Generally, URLs are managed by category (such as “sports sites”) and an entire category is blocked, throttled, or

allowed

5

. In the case of a national policy requiring URL blocking, the on-line service and blocking policy would likely

be managed by the government. The URL filter can simply stop the traffic, or it can redirect the user to another

web page, showing a policy statement or noting that the traffic was blocked. URL blocking in the network can be

enforced by proxies, as well as firewalls and routers.

5 URL filtering categories are established by security service providers and are often based on a combination of human analysis of web pages combined with some automated

scanning of web page content. Most security service providers offer URL filtering databases for the purposes of managing corporate network traffic, but they can be used in

other contexts, such as those discussed in this paper.

Sidebar:

Encryption, Proxies, and Blocking Challenges

Several of the techniques discussed in this paper,

including Deep Packet Inspection (DPI)-based blocking and

URL-based blocking, have a very real limitation: they must

be able to see the traffic being evaluated. Web servers

that offer encryption or users who add encryption to their

communications (typically through application-specific

encryption technology, such as TLS/SSL) cannot be reliably

blocked by in-the-network devices. Many of the other

techniques are also easily evaded when user have access

to VPN technology that encrypts communications and

hides the true destination and type of traffic. Although

researchers and vendors have developed some ways of

identifying some types of traffic through inference and

analysis, these techniques often are simply guessing at what

type of traffic they are seeing.

In recent research, 49% of US web traffic (by volume) was

encrypted in February, 2016. (See: http://www.iisp.gatech.

edu/sites/default/files/images/online_privacy_and_isps.

pdf) This traffic would be effectively invisible to URL-based

blocking and DPI tools that look at content, because the

only visible information would be the domain name of the

server hosting the information. To compensate for this

“going dark,” some network blocking uses active devices

(called proxies) that intercept and decrypt the traffic

between the user and the web server, breaking the end-to-

end encryption model of TLS/SSL.

When proxies are used, these cause significant security

and privacy concerns. By breaking the TLS/SSL model,

the blocking party gains access to all encrypted data and

can inadvertently enable third-parties to do the same.

The proxy could also change the content. If the blocking

party has control over the user’s system (for example, a

corporate-managed device would be highly controlled),

the proxy may be very transparent. Generally, however, the

presence of a proxy would be obvious to the end user, at

least for encrypted (TLS/SSL) traffic (e.g. the user may get

an alert that the certificate is not from a trusted authority).

In addition, new industry and IETF standards (such as HTTP

Strict Transport Security [RFC6797], HTTP Public Key Pinning

[RFC 7469], and DANE [RFC 6698]) and new security features

in modern Internet browsers make it more difficult to proxy

(and decrypt) TLS/SSL traffic without the knowledge and

cooperation of the end user.

Proxies installed for content blocking reasons may also

introduce performance bottlenecks into the flow of

network traffic, making services slow or unreliable.

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

16

internetsociety.org

URL blocking requires the blocking party (such as the user’s ISP) to have the ability to intercept and control

traffic between the end-user and the Internet. URL blocking is usually expensive, because the filtering device

generally has to be in-line between the user and the Internet, and thus requires a high level of resources to give

acceptable performance.

URL blocking is generally considered to be very effective at identifying content that may be on different servers

or services because the URL doesn’t change even if the server changes IP addresses. In a few cases, URL blocking

may fail to fully block the traffic when the URLs are very complicated or change frequently. This can happen

because an information publisher has deliberately decided to actively evade URL filter blocking, or it can be a

side effect of some advanced publishing systems such as those used for large on-line publications.

URL blocking usually is effective at high-level URLs, such as a particular web page, but is not as effective when

deep links (such as individual bits of content within a web page) are considered. Depending on how the user

navigated to the particular content, URL blocking may or may not be able to block all access—if the user has a

“deep link” not covered by the URL filter, the content will be allowed. For example, the Playboy web site includes

both playboy.com URLs, but also embedded content using the “playboy.tv” domain name. A URL filter that didn’t

also include “playboy.tv” URLs would not block the video content.

URL filtering can usually occur

at the enterprise or the ISP level.

URL Filter

In URL-based blocking, the blocking device

has a list of web URLs to block. Trying to view

any of the URLs on the list will cause an

interruption.

URL-based blocking can have both false

positives and false negatives. When a

publisher is actively trying to avoid the filter,

simply changing the name of the file or the

server is often enough to avoid the block.

In the diagram here, the bomb on the OLD

server was blocked because the URL is on the

list. The same graphic on a dierent server is

not blocked because the NEW server URL is

not on the list.

URL-Based Blocking

Internet

List of URLs

to be blocked

http://old.example.com/bomb

OLD.example.com

http://old.example.com/bomb http://old.example.com/kitten

NEW.example.com

http://new.example.com/bomb http://new.example.com/kitten

This content

is blocked because

the URL is on the list.

No content is blocked

since none of the URLs

from the new.example.com

are on the block list.

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

17

internetsociety.org

All types of URL blocking are highly dependent on the quality of the filter, and a poorly designed or overly broad

filter may block unintended traffic or have other negative effects on the user experience, such as affecting the

loading or formatting of web pages when some component is being blocked.

As with Deep Packet Inspection types of blocking, URL blocking requires some type of proxy to see the full URL

when traffic is encrypted with HTTPS (TLS/SSL). See sidebar “Encryption, Proxies, and Blocking Challenges”, page

15, for more information on the effects on end-user privacy. For encrypted traffic, URL blocking can only see the IP

address of the server, and not the full URL, resulting in a much higher level of unintended blocking. Because

proxies are expensive and intrusive to the user experience, URL blocking does not work well as a tool for policy-

based blocking.

Platform-Based Blocking (Especially Search Engines)

In some cases, national authorities will work with major information service providers to block information within

their geographic region without blocking the entire platform. The most common examples of platform filtering

are through the major search engine providers and social media platforms. Recently, it has also been reported that

mobile application stores (such as the Apple Store and Google Play) are working with national authorities to block

downloads of specific applications in their country.

In Platform-based blocking the party wishing to block content

has to work with each search engine individually.

Each search engine must maintain a separate list of content to

be blocked and who to block it for. If the search engines have

dierent lists, the user will get dierent results depending on

which search engine they ask. This can also vary between

countries with the same search engine (for example, Google

Germany may return dierent results than Google France).

Platform-based blocking

(especially search engines)

search for

Bomb

Bomb?

Bomb?

Bomb?

Internet

BLOCK LIST

http://example.com/bomb

NO

RESULTS

NO

RESULTS

BLOCK LIST

http://example.com/cute-kittens

BLOCK LIST

http://example.com/bomb

BING

Google

France

Google

Germany

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

18

internetsociety.org

Platform-based blocking is a technique that requires the assistance of the

platform owner, such as a search engine operator like Google or Microsoft.

In this technique, queries from a particular set of Internet users to a search

engine will receive a different set of results from the rest of the Internet—

filtering out pointers to content that are, in some way, objectionable.

In some cases the definition of what is to be blocked is based on local

regulation and government requirements, but it may also be due to concerns

by the search engine operator. For example, a search engine may block

pointers to malware or content considered inappropriate according to its

own terms of service.

Because search engine blocking requires the cooperation of the

search engine provider, this limits its use to two very specific scenarios:

country-level rules (blocking content based on country-specific or region-

specific rules) and age-based rules (blocking material inappropriate for

young people).

Search engine blocking only affects users who choose a particular search

engine, and only when the users are identified as being from a particular set

with filter rules. In age-based blocking, such as SafeSearch

6

(offered by major

search engines and content providers), an explicit opt-in is required.

Since search engine blocking only filters out pointers to content, and not

actual content, it is an extremely ineffective technique, and can have the

unintended consequence of drawing increased attention to the blocked

content. The presence of multiple search engines, as well as alternative

methods of finding content, make this type of blocking very difficult

to enforce.

Although search engine blocking seems like it does very little towards

blocking content, the technique is extremely popular at the national level,

and governments around the world are known to demand that major

search engines implement filters according to their regulations, such as

infringement of copyright or particular types of speech prohibited by

national law. For example, Google reported in 2015 that it had received 8,398 requests from 74

national courts to remove 36,834 results from its search results

7

. Copyright infringement requests

made by individuals are also very popular: in June 2016, Google reported that 6,937 copyright

owners had requested over 86 million search results to be removed from Google results during

that month

8

.

Search engine blocking is also used by individuals as part of the so-called “right to be forgotten,”

with over a million URLs globally requested to be blocked in the last two years (May 2014 to

June 2016).

6 SafeSearch is a feature of major search engines, including Google Search, Microsoft Bing, and Yahoo!, that blocks results containing

“inappropriate or explicit images” from search results.

7 https://www.google.com/transparencyreport/removals/government/?hl=en

8 https://www.google.com/transparencyreport/removals/copyright/?hl=en

Sidebar:

Blocking On Other Platforms

While search engine blocking is the

most common type of platform

blocking, other platforms with

enormous users communities are often

considered for this technique. Common

examples of these types of platforms

include Facebook (which has over 1.5

billion active users each month) and

YouTube (with over a billion unique

users). Attempts to use network-based

or URL-based techniques to block

individual content elements, such

as a particular news article, are very

difficult. Because they don’t want to

be seen as blocking all of Facebook

(for example), national authorities have

proposed working with major platform

providers to filter out specific types of

content they deem illegal.

Very little is known about the

effectiveness, scope, or side effects

of other kinds of platform blocking,

as this technique has not been widely

and reliably observed on platforms

other than search engines. While the

major platforms, such as Facebook,

YouTube, and Twitter, will universally

block certain types of content (such as

malware and pornographic material)

and provide customized content feeds

to their users, information on national-

specific blockages is not available.

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

19

internetsociety.org

DNS-Based Content Blocking

DNS-based content blocking avoids one of the problems with other techniques: the cost and

performance impact of filtering all network traffic. Instead, DNS-based content blocking focuses

on examining and controlling DNS queries.

With DNS-based content blocking, a specialized DNS resolver (see Sidebar: DNS Overview)

has two functions: in addition to performing DNS lookups, the resolver checks names against

a block list. When a user’s computer tries to use a blocked name, the special server returns

incorrect information, such as the IP address of a server displaying a notice that the content has

been blocked. Or, the server may claim that the name does not exist. The effect is that the user

is impeded from easy access to content using certain domain names.

As with all network-based blocking, DNS-based content blocking is only effective when the

organization doing the blocking has complete control over the network connection of the end

user. If the user can select a different connection, or use a different set of DNS servers, the

technique does not affect them. For example, when Turkey blocked some DNS queries in 2012,

users changed their systems to use Google’s popular public DNS servers and avoid the blockage.

Turkish authorities responded by hijacking all traffic to the Google DNS service, which caused

significant collateral damage. DNS-based content blocking requires firewalls or other devices

that can intercept and redirect all DNS queries to the specialized blocking-aware DNS servers or

it will not be very effective.

The effectiveness of DNS-based content blocking is similar to IP-based blocking. It is slightly

more effective because the list of domain names is easier to keep updated

and is more accurate than a list of IP addresses for most types of content

blocking. However, it is slightly less effective because changing domain names

is simpler than changing IP addresses, which makes it easier for both end users

and information publishers to evade this type of block.

An alternative form of DNS-based content blocking is when domain names

are taken down, or removed from the DNS altogether. This method is more

difficult to circumvent and the collateral damage is somewhat limited. In many

cases it depends on the efficacy of cross-border cooperation, when a request

or a court order comes from a jurisdiction different from where the registry or

registrar operates.

DNS-based content blocking has similar drawbacks to blocking based on IP

address: both prohibited and non-prohibited content may be on the same

server using the same name (such as “facebook.com”), yet all would be

blocked. In addition, the modification of DNS responses may cause other

technical problems that interrupt other valid services

9

.

DNS-based content blocking also depends on the user playing by the normal

rules of the Internet and using the standard DNS service to translate names

to IP addresses. Users who have complete control over their own computers

and some technical expertise can reconfigure them to evade the standard

DNS service and use alternatives, or simply have a list of name-to-address

translations stored locally.

9 Readers interested in more details may wish to refer to Internet Society’s “Perspectives on DNS Filtering” report at https://www.

internetsociety.org/internet-society-perspectives-domain-name-system-dns-filtering-0

Sidebar:

DNS Overview

The DNS is a conceptually simple

system that allows a string of labels

(such as “www,” “isoc,” and “org”)

separated by dots (the domain

name) to be looked up in a database

distributed across multiple DNS

servers. The domain name lookup

results in an answer (for example,

an IP address or a website), or the

answer that the name does not exist.

The most common type of DNS

lookup is for IP (Internet Protocol)

addresses. This is the type of lookup

that occurs each time a user types a

URL into a web browser, for example.

Normally, the individual application

(such as the web browser) does

not perform the full lookup, which

involves several steps. Instead, the

application uses an intermediate

system called a “resolver” (because

it resolves DNS name lookups),

which navigates the DNS distributed

database to retrieve the information

requested.

In DNS-based content blocking, the

normal operation of the resolver is

changed.

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

20

internetsociety.org

DNS Server

for isoc.org

DNS Server

for example.org

What is the IP address

for example.com?

isoc.org = X.Y.2.9

isoc.org?

isoc.org = X.Y.2.9

What is the IP address

for isoc.org?

No such name

In DNS-based blocking, the blocking device has a list of DNS names to block.

Because most Internet connections require a translation from a DNS name to an IP address,

blocking the query and returning a false answer can discourage users from trying to retrieve

blocked content or connect to blocked services by other means (e.g. directly typing the IP address).

DNS-Based Blocking

The DNS query for

isoc.org operates

normally with the

correct answer

returned because

the name is not

on the block list.

The DNS query for

example.com is

intercepted by the

blocking device which

returns an answer of

“No Such Name”

because example.com

is on the block list.

Internet

DNS

RESOLVER

example.com

List of domain

names to be

blocked or

redirected

1122

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

21

internetsociety.org

Content Blocking Summarized

Internet Content Blocking Techniques

IP and Protocol-Based

Blocking

Deep Packet Inspection-

Based Blocking

URL-Based Blocking Platform-Based Blocking

(especially search

engines)

DNS-Based Blocking

Overview

A device is inserted in the

network that blocks based

on IP address and/or

application (e.g., VPN)

A device is inserted in the

network that blocks based

on keywords and/or other

content (filename, for

example)

A device is inserted in the

network that intercepts web

requests and looks up URLs

against a block list

Working with application

providers (such as search

engines), content is

modified according to

local requirements

At the network or ISP level,

DNS traffic is funneled to a

modified DNS server that can

block lookups of certain domain

names

Is it effective?

Because IP addresses

are easily changed and

content easily moved, this

technique works poorly.

This only works well when

the information publisher

is not actively working to

evade the block.

Where the blocked

information is easily

characterized, this is very

effective. For general

blocking (e.g., “block adult

content”) or in the face of

encryption, the technique

is very ineffective

This is a common technique

that works well when

blocking access to entire

categories of information.

New pages and smaller sites

slip through easily, as do

encrypted web servers.

Because there is no

monopoly in search

engines (for example) and

consumer preferences are

constantly changing, this

type of blocking is largely

cosmetic and works

poorly.

DNS blocking is easily evaded

both by content publishers

and end users. DNS blocking

is only effective when each

name has a very small amount

of content, and all that content

should be blocked. Technical

challenges, over-blocking, and

ease of evasion make this an

ineffective technique.

Who is

affected?

Anyone who is “behind”

the device is affected.

Anyone who is “behind” the

device is affected.

Users “behind” the device,

and for whom the device

can intercept and evaluate

web traffic.

Users of the search engine

which has installed the

block

Users of the modified DNS

server. This can be enforced at

the network or service provider

level.

How specific

is it?

Affects all content on a

server, whether illegal or

not. This works even when

the data are encrypted.

Affects only content which

matches blocking rules.

Requires proxies to work

with encrypted web pages.

Affects individual web

pages and web elements.

Requires proxies to work

with encrypted web pages.

Affects individual web

pages and elements.

Usually done at the

individual URL level.

Affects all content served by

a domain name, whether

illegal or not. Cannot be

effectively used to distribute

content.

What type of

technique is this?

Blocks content Blocks content Blocks content Discourages and frustrates

access

Discourages and frustrates

access

How much collateral

damage is caused?

Any targeting of larger

servers has a huge false

positive rate, blocking

both illegal and legal

content.

Depending on the quality

of the blocking rules, the

false positive rate can range

from very low to quite

high. Writing good rules is

difficult.

Most URL filtering is based

on commercial services

that categorize traffic. For

mainstream blocks, this can

be quite specific, but for

special purpose blocks, the

error rate is quite high.

The false positive rate

is considered to be low,

because each page block

is requested individually.

The problem of non-

legitimate requests causes

some inappropriate

information to be

blockage.

Any targeting of domain

names used by larger servers

has a huge false positive rate,

blocking both illegal and legal

content. Ineffective when

CDNs are used (or causes an

extremely high level of false

positives).

What are common

ways to evade it?

Publishers can change

IP addresses, migrate

content, or use Content

Delivery Networks (CDNs)

to evade. VPN users evade

by hiding IP addresses.

Multiple layers of encryption

effectively evade this type

of blocking. When the

filtering rules are poorly

written, small changes

in text can easily bypass

blocks.

Multiple layers of encryption

effectively evade this type

of blocking. Use of non-

standard application layer

is often an effective evasion

technique.

Users can choose

alternative platforms,

such as a different search

engine, very easily.

Users can avoid using DNS

lookups using local facilities,

or can send their queries to

an un-modified public server

(typically though a VPN).

Are there side-effects

or technical issues?

Maintaining long IP

address lists is difficult

and error-prone, and

requires significant

resources. Network

devices doing this type

of blocking are typically

speedy, so performance

issues are not common.

Content-aware filtering has

significant performance

costs and is not practical

in many environments

(without enormous

resources). When proxies

are used, security can be

severely compromised.

URL filtering can cause

performance problems,

decreasing overall speed

and reliability. When proxies

are used, security can be

severely compromised.

Many search engines

report on “suppressed”

information, which itself

creates a trail to the

content.

DNS security is compromised

when a modified server is

deployed.

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

22

internetsociety.org

Conclusion

Understanding the different blocking techniques, their

effects and side effects, is important both for policy

makers considering the use of such measures and for

Internet advocates and others wishing to influence

content blocking practices.

All blocking techniques are prone to two main drawbacks:

1. They do not solve the problem

Blocking techniques do not remove content from

the Internet, nor do they stop the illegal activity or

prosecute culprits; they simply put a curtain in front of

the content. The underlying content remains in place.

2. They inflict collateral damage

Every blocking technique suffers from over-blocking and under-blocking: blocking

more than is intended and, at the same time, less than intended. They also

cause other damage to the Internet by putting users at risk (as they attempt to

evade blocks), reducing transparency and trust in the Internet, driving services

underground, and intruding on user privacy. These are costs that must be

considered at the same time that blocking is discussed.

Recommendations

The Internet Society believes the most appropriate way to counteract illegal content

and activities on the Internet is to attack them at their source. Using filters to block

access to online content is inefficient, likely to be ineffective, and is prone to generate

collateral damage affecting innocent Internet users.

We suggest two main strategies for policy makers concerned about illegal content on

the Internet:

1. Attack the issue at the source: The least damaging approach for the Internet is

to “attack” illegal content and activities at their source. Removing illegal content

from its source, and undertaking enforcement against the perpetrators avoids the

negative effects of blocking, and is more effective at removing illegal content

10

.

Cooperation across jurisdictions and stakeholders is a prerequisite for success, as

illegal content online extends beyond national borders and national law.

10 When the national authority is in the same jurisdiction as the consumer of content, removing illegal content at the source seems

an easy way around the complexities and overhead of cross- border actions. We acknowledge that removing the content at

the source is challenging in the context of a cross-border Internet, where providers and consumers of content may be located

in different jurisdictions, subject to different laws. Yet, we consider this should not be a reason not to identify more efficient

solutions that do not harm the Internet.

Sidebar:

Circumventing Content Blocking

Policy makers should keep in mind an important point when

considering blocking Internet content: all of the technical

blocking techniques can be bypassed by a sufficiently

motivated user. In many cases, only minimal work is needed

to evade the block.

If traffic to a host or domain name is blocked, tools such as

VPNs can be used to hide the traffic. If the traffic content is

being inspected, then it can be encrypted so that it does not

trigger the block. If the content is taken down, other users

may reload it on other servers. If the domain name used is

removed, end users can still access the host if they know

the IP address, or a new domain name can be selected as a

replacement. If a search engine removes results, there are

always other search engines.

End users are not the only ones who can and do evade blocks.

Information publishers also have many approaches to duck

various blocking techniques. If a publisher works hard enough

to distribute and disseminate content, no block technique

can stop them.

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

23

internetsociety.org

2. Prioritize and use alternative approaches: Depending on circumstances, different approaches can be

quite effective. For example

• Effective cooperation among service providers, law enforcement

and national authorities may provide additional means to help the

victims of illegal content, and to take enforcement action against the

perpetrators

11

.

• Creating an environment of trust where users receive information on

what is legal and what is not can improve self-policing.

• In some cases (e.g. parental control), empowering user to use filters

on their own devices, with their consent, can be effective and least

damaging to the Internet.

• On a voluntary or legal basis, some websites (e.g. gambling websites)

could use geolocation to prevent access from countries where their

services are not allowed.

Minimizing Negative Effects

All content blocking techniques have serious deficiencies, especially in the context of blocking based on

public policy considerations. All techniques behave poorly and can be evaded. For this reason, and the

reasons stated before, we advise against content blocking.

Nonetheless, these techniques are still used. Recognizing this reality, we offer the following specific

guidelines to lessen the negative impact:

a. Rule out all non-blocking options: First, and foremost, exhaust all practical options to have content

addressed at the source, or any other alternative means to blocking. Blocking content should not be

pursued simply because it is easier.

b. Be transparent: There should be transparency about the blocking as well as the underlying objective

and policies. National authorities should make sure that affected users have the opportunity to raise

concerns about negative impacts on their rights, interests and opportunities.

c. Consider your responsibility towards the Internet: The blocking party should be aware that they

share a responsibility towards the system as a whole to not harm the stability, security and resilience

of the Internet. Blocking techniques adversely impact the way the Internet is collectively managed and

functions. Sometimes the damage is direct, and sometimes, it is indirect. For instance, users working

around the block may cause problems or threaten their personal security.

e. Think globally, act locally: Local blocking and filtering can have global effects. But generally, blocking

content as locally as possible will minimize the global impact. Ideally, blocking at the user’s end-point is

most efficacious and minimizes collateral damage.

f. Involve stakeholders: Policy development and implementation should involve a broad set of

stakeholders including technological, economic, consumer rights and other specialists to ensure the

appropriate steps are taken to minimize negative side-effects.

g. Keep it temporary: Any blocking measures should be temporary. They should be removed as soon as

the reason for blocking ceases to exist. It is quite common for illegal content to be moved to evade

blocking measures, yet the measures often remain in place long after the content has moved.

h. Follow due legal process: Any blocking order of unlawful content must be supported by law,

independently reviewed, and narrowly targeted to achieve a legitimate aim. The least restrictive means

available to deal with illegal activity should be prioritized. Internet Service Providers or other Internet

intermediaries should not become de-facto law enforcement agents: they should not be required to

determine when conduct or content is illegal.

11 For example, partnerships with the finance industry can be used to identify and limit illegal transactions.

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

24

internetsociety.org

Glossary

CDN A content delivery network or content distribution network (CDN) is a globally

distributed network of proxy servers deployed in multiple data centers. The

goal of a CDN is to serve content to end-users with high availability and

high performance. CDNs serve a large fraction of the Internet content today,

including web objects (text, graphics and scripts), downloadable objects

(media files, software, documents), applications (e-commerce, portals), live

streaming media, on-demand streaming media, and social networks.

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Content_delivery_network)

Content In the context of this paper, we use “content” generally to describe information

found on the Internet. This content might be a full document or just a

paragraph of some text, an image, a video, or even just audio (such as a

podcast). Content could be on web pages viewed in a browser, or it could be

accessible through more specialized tools such as a custom application.

DNS The Domain Name System (DNS) is a hierarchical decentralized naming system

for computers, services, or other resources connected to the Internet or a

private network. It associates various information with domain names assigned

to each of the participating entities. Most prominently, it translates more

readily memorized domain names to the numerical IP addresses needed for

locating and identifying computer services and devices with the underlying

network protocols. By providing a worldwide, distributed directory service, the

Domain Name System is an essential component of the functionality of the

Internet, that has been in use since 1985.

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domain_Name_System)

DPI Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) is a form of computer network packet filtering

that examines the data part (and possibly also the header) of a packet as it

passes an inspection point, searching for protocol non-compliance, viruses,

spam, intrusions, or defined criteria to decide whether the packet may pass or

if it needs to be treated in another way, including discarding the packet.

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deep_packet_inspection)

Illegal In the context of this paper, we use “illegal” to describe content that is

prohibited in a national context no matter what the reason. This could be

content that is illegal because it is a copyright violation (or some other type

of intellectual property), such as a pirated movie. It could be content that

is illegal because it is objectionable for moral reasons, such as obscenity

or child pornography. It could be content that it is illegal because national

authorities wish to suppress it or find it offensive, such as a cartoon depicting

the president of the country in an unfavorable way. Content that is illegal in

one jurisdiction may be completely legal in another. Content that is illegal in

one context (such as indecent comedy, when viewed by children) may be

completely legal in another (such as when viewed by adults), even within the

same jurisdiction.

IP address An IP address (abbreviation of Internet Protocol address) is an identifier

assigned to each computer and other devices (e.g., printer, router, mobile

device, etc.) connected to the Internet. It is used to locate and identify the

node in communications with other nodes on the network.

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IP_address)

Internet Society — Perspectives on Internet Content Blocking: An Overview

25

internetsociety.org

False Negative A false negative occurs when content is not blocked, but it should have

been. For example, if illegal pharmacies are being blocked, a brand new illegal

pharmacy might not be blocked if the server had not been added to the

block list yet. This would be called a false negative.

False Positive A false positive occurs when some content is blocked which was not

intended to be blocked. For example, if pornography is being blocked,

information about cooking of chicken breasts might be blocked if the block

used a poorly constructed keyword search. This would be considered a false

positive.

TLS/SSL Transport Layer Security (TLS) and its predecessor, Secure Sockets Layer

(SSL), both frequently referred to as “SSL”, are cryptographic protocols

that provide communications security over a computer network. Several

versions of the protocols find widespread use in applications such as web

browsing, email, Internet faxing, instant messaging, and voice-over-IP (VoIP).

Websites use TLS to secure all communications between their servers and

web browsers. The Transport Layer Security protocol aims primarily to