Human

Studies 8:279-303 (1985).

©1985

.Martinus

Ni/hoff

Publishers,

Dordrecht.

Printed in

the

Netherlands.

SOME GUIDELINES FOR THE FHENOMENOLOGICAL ANALYSIS

OF INTERVIEW DATA

RICHARD H. HYCNER

355 S. Nardo Ave, Solana Beach, CA 92075, USA

Summary

This article explicates, in a concrete, step-by-step manner, some pro-

cedures that can be followed in phenomenologically analyzing inter-

view data. It also addresses a number of issues that are raised in rela-

tion to phenomenological research.

Parti

Introduction

This article is an attempt to spell out in a step-by-step manner, a series

of procedures which can be utilized in phenomenologically "analyz-

ing"^ interview data. Despite the pioneering and extremely valuable

works of Colaizzi

(1973,

1978), Giorgi (1975), Keen (1975) and

Tesch (1980), I have found that for many students and even colleagues,

who have not had much background in philosophical psychology,

they still have many questions about specific steps in carrying out a

phenomenological analysis of interview data. This is an attempt to

respond to this need.

There is an appropriate reluctance on the part of phenomenologists

to focus too much on specific steps in research methods for fear that

they will become reified as they have in the natural sciences. This

concem is well expressed by Keen (1975, p. 41).

...unlike other methodologies, phenomenology cannot be reduced

to a 'cookbook' set of instructions It is niore an approach, an atti-

tude,

an investigative posture with a certain set of goals.

280

Keen is completely right. What is being presented here is but one pos-

sible manner of phenomenologically analyzing data. It is presented

more as an attempt to sensitize the researcher to a number of issues

that need to be addressed in analyzing interview data rather than as a

"cookbook" procedure. Giorgi (1971) strongly emphasizes that any

research method must arise out of trying to be responsive to the phe-

nomenon. No method (including this one) can be arbitrarily imposed

on a phenomenon since that would do a great injustice to the integrity

of that phenomenon. On the other hand, there are many researchers

who simply have not had enough philosophical background to begin

to even know what "being tme to the phenomenon" means in relation

to concrete research methods The following guidelines have arisen out

of a number of years of teaching phenomenological research classes to

graduate psychology students and trying to be true to the phenomenon

of interview data while also providing concrete guidelines.

1.

Transcription. An obvious but important step in phenomenologically

analyzing interview data is to have the interview tapes transcribed. This

includes the literal statements and as much as possible noting significant

non-verbal and para-linguistic communications. Usually it is helpful to

leave a large margin to the right of the transcription so that the re-

searcher will later be able to note what s/he believes are the units of

general meaning.

2.

Bracketing and the phenomenological reduction.'^ Now we come to

the procedure which to be followed in listening to the recording of

the interviews and in reading the transcripts The research data, that is,

the recordings and the transcriptions, are approached with an openness

to whatever meanings emerged. This is an essential step in following the

phenomenological reduction necessary to elicit the units of general

meaning. Keen (1975, p. 38) states that:

The phenomenological reduction is a conscious, effortful, opening

of ourselves to the phenomenon

as

a phenomenon. ...We want not

to see this event as an example of this or that theory that we have

we want to see it as a phenomenon in its own right, with its own

meaning and structure. Anybody can hear words that were spo-

ken; to listen for the meaning as they eventually emerged from the

event as a whole is to have adopted an attitude of openness to the

phenomenon in its inherent meaningfubiess. It is to have 'bracket-

ed' our response to separate parts of the convereation and to have

let the event emerge as a meaningful whole.

281

It means suspending (bracketing) as much as possible the researcher's

meanings and interpretations and entering into the world of the unique

individual who was interviewed. It means using the matrices of that

person's world-view in order to understand the meaning of what that

person is saying, rather than what the researcher expects that person

to say.

This in no way means that the phenomenologist is standing in some

absolute and totally presuppsitionless space. To say this would be to

fall into the fallacy of "pure objectivity" that natural science has often

been prone to. In fact, the phenomenological reduction teaches us the

impossibility of a complete and absolute phenomenological reduction.

In the words of Merleau-Ponty (1962, p. xiv):

The most important lesson which the reduction teaches us is the

impossibility of a complete reduction. ...that radical refiection

amounts to: a consciousness of its own dependence on an unre-

fiective life which is its initial situation, unchanging, given once

and for all.

A good check on whether the researcher has been able to bracket

his/her presuppositions is for the researcher to list these presupposi-

tions that s/he is consciously aware of as well as to dialogue with his/

her research (dissertation) committee about these presuppositions.

Such dialogue may very well bring out presuppositions that the re-

searcher was not consciously aware of.

3.

Listening to the interview for a sense of the whole. Once the re-

searcher has "bracketed" his/her interpretations and meanings as

much as is possible, s/he will want to get a sense of the whole inter-

view, a gestalt (Giorgi, 1975, p. 87). This will involve listening to the

entire tape several times as well as reading the transcription a number of

times.

This will provide a context for the emergence of specific units

of meaning and themes later on. When doing this the researcher espe-

cially wants to listen to the non-verbal and para-linguistic levels of com-

munication, that is, the intonations, the emphases, the pauses, etc.

It is also often important to have available a joumal so that the re-

searcher can note specific issues that might arise or to record general

impressions. In this manner, these perceptions do not interfere with

the attempt to bracket interpretations and biases while trying to stay

as true to the interviewee's meaning as much as possible.

282

4.

Delineating units of

general

meaning. At this point the interview has

been transcribed, the researcher has bracketed his/her presuppositions

as much as possible and has tried to stay as true to the data as possible,

as well as gotten a sense of the whole of the interview as a context. The

researcher is then ready to begin the very rigorous process of going

over every word, phrase, sentence, paragraph and noted significant non-

verbal communication in the transcript in order to elicit the partici-

pant's meanings. This is done with as much openness as possible and at

this point does not yet address the research question to the data. This

is a process of getting at the essence of the meaning expressed in a

word, phrase, sentence, paragraph or significant non-verbal communica-

tion. It is a crystallization and condensation of what the participant

has said, still using as much as possible the literal words of the par-

ticipant. This is a step whereby the researcher still tries to stay very

close to the literal data. The result is called a unit of general meaning.

I define a unit of general meaning as those words, phrases, non-verbal

or para-Unguistic communications which express a unique and coherent

meaning (irrespective of the research question) clearly differentiated

from that which precedes and follows. (These might most easily be

recorded in the special margin alongside the transcription). If there

is ambiguity or uncertainty as to whether a statement constitutes a

discrete unit of general meaning, it is best to include it. Also at this

point all general meanings are included, even redundant ones.

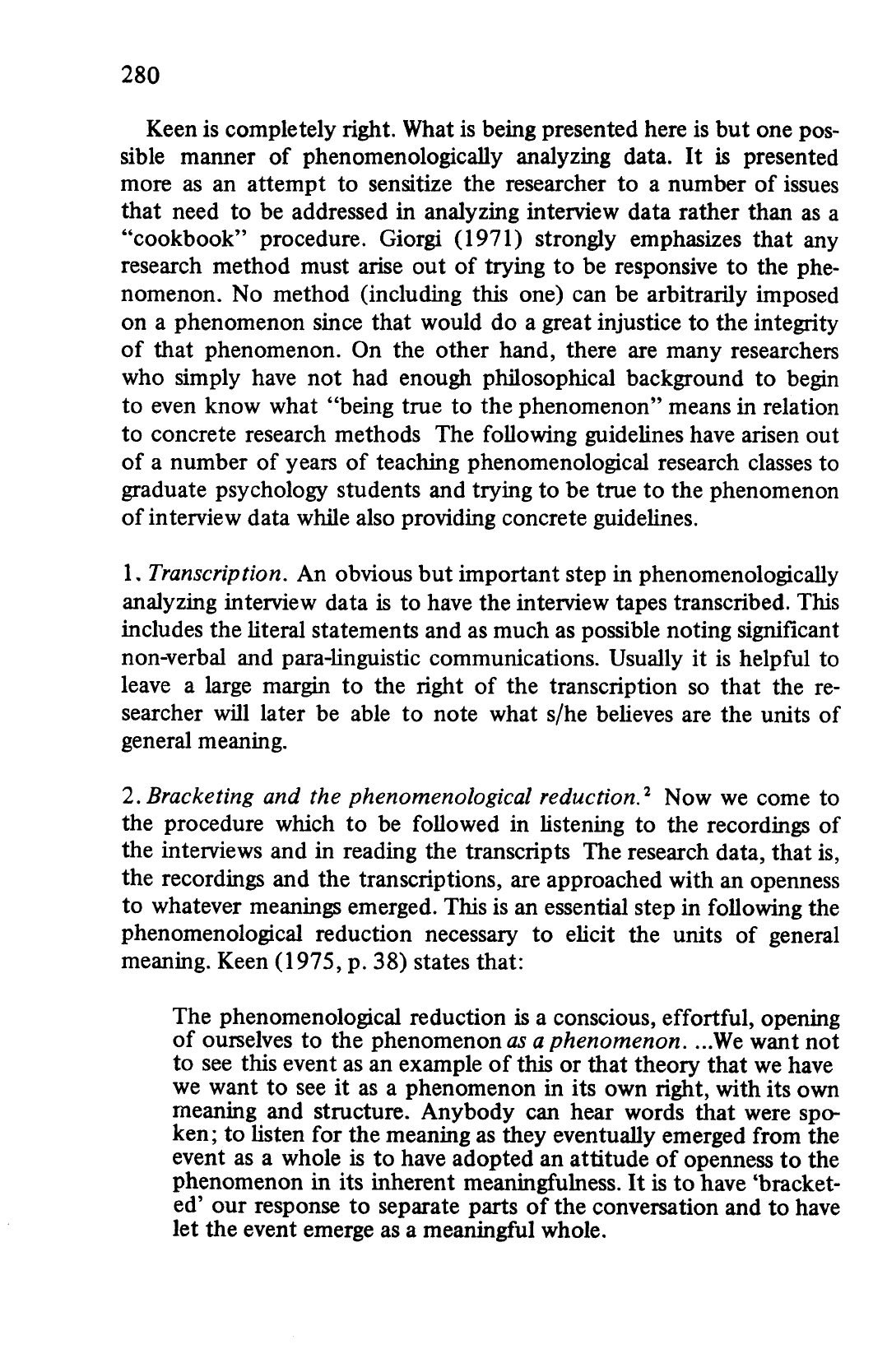

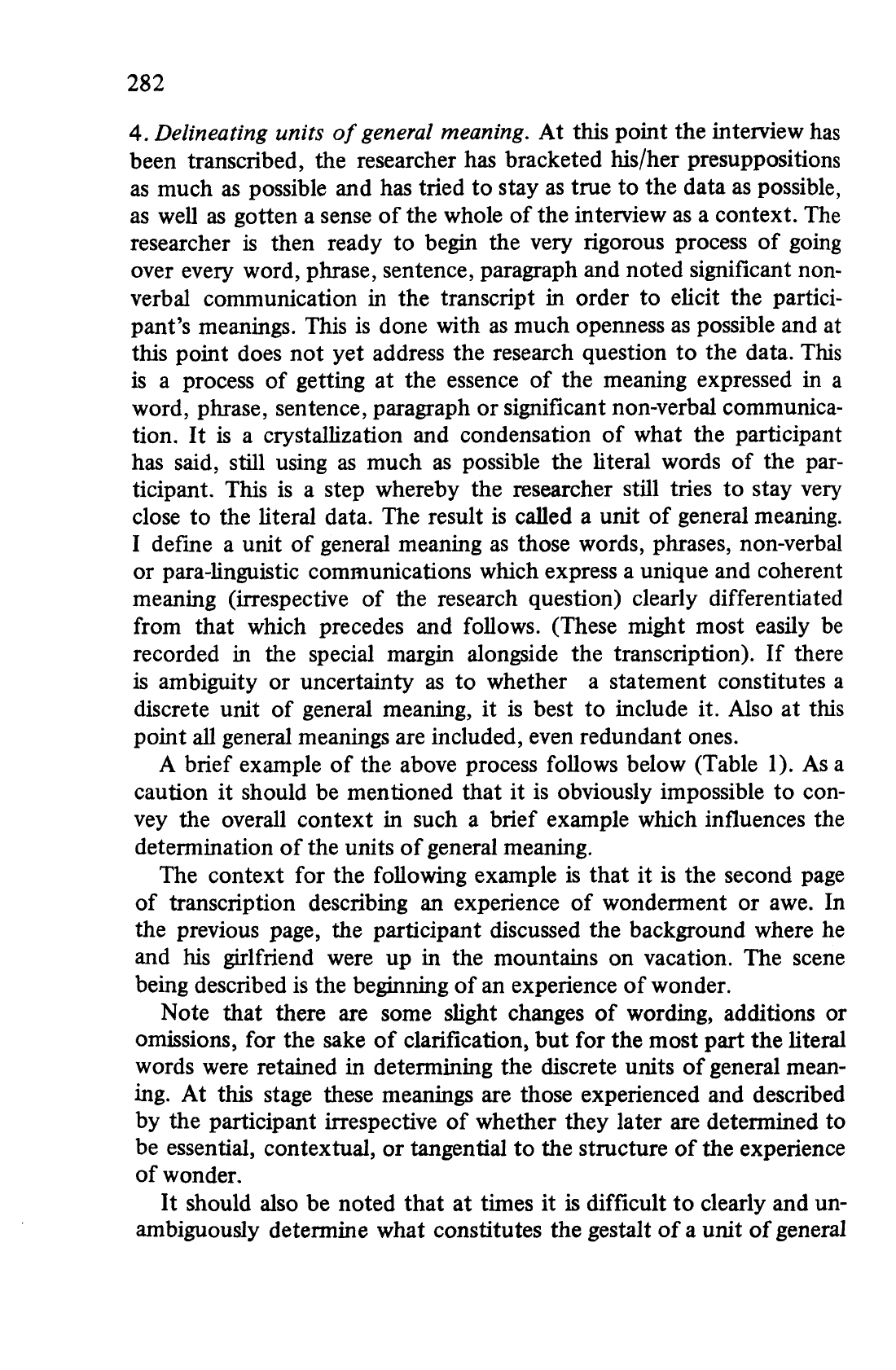

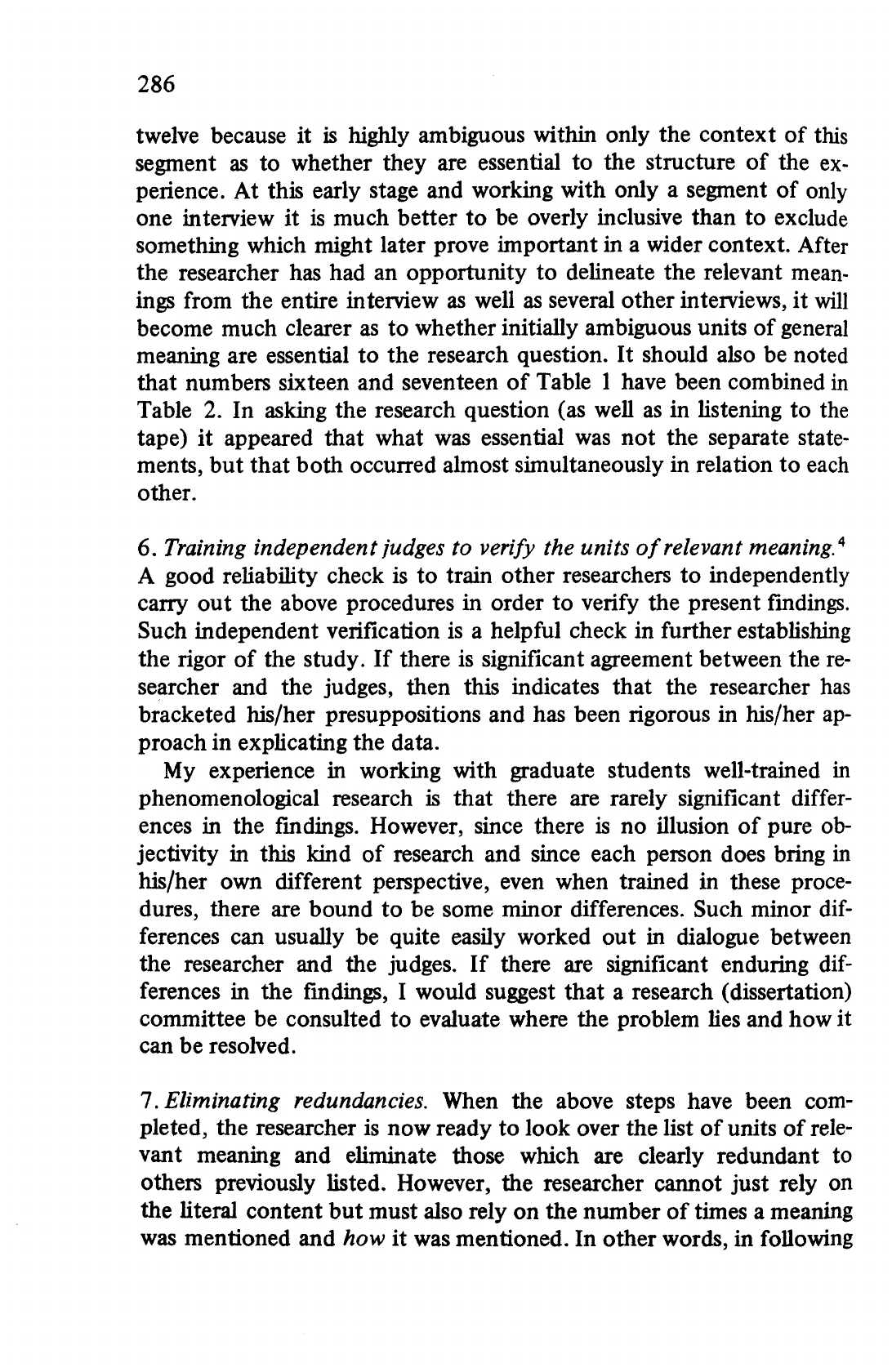

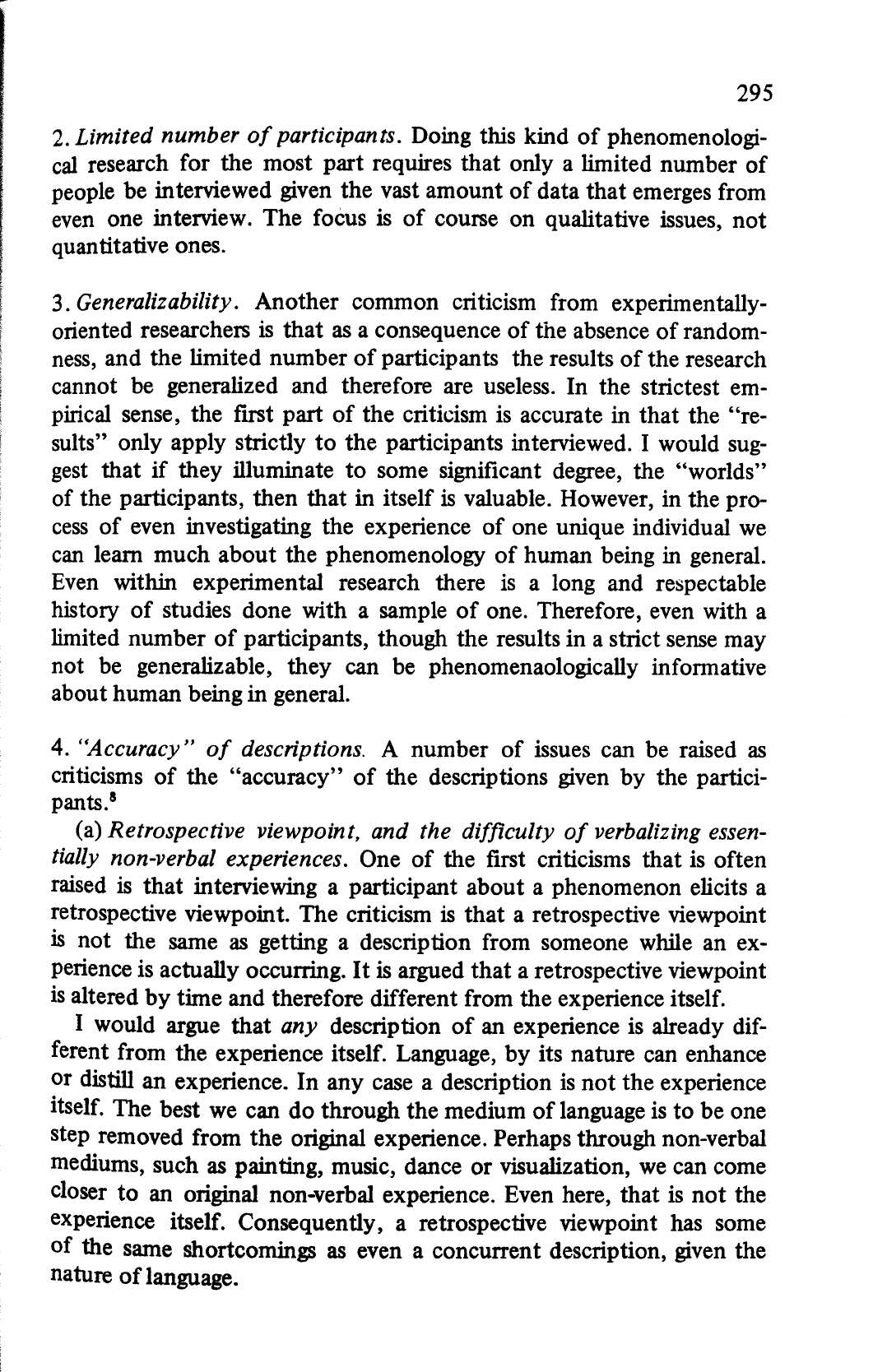

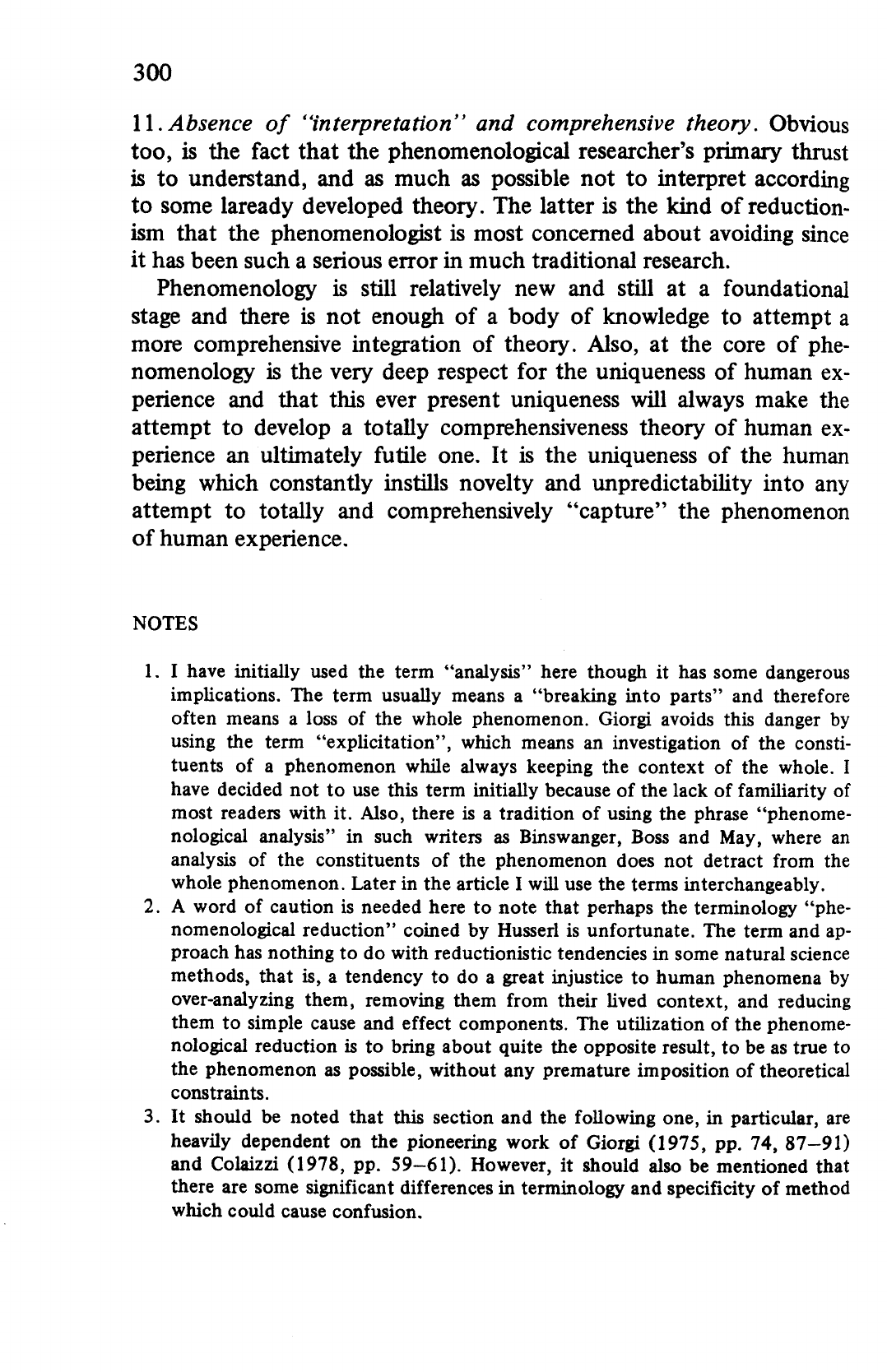

A brief example of the above process follows below (Table 1). As a

caution it should be mentioned that it is obviously impossible to con-

vey the overall context in such a brief example which influences the

determination of the units of general meaning.

The context for the following example is that it is the second page

of transcription describing an experience of wonderment or awe. In

the previous page, the participant discussed the background where he

and his girlfriend were up in the mountains on vacation. The scene

being described is the beginning of an experience of wonder.

Note that there are some slight changes of wording, additions or

omissions, for the sake of clarification, but for the most part the literal

words were retained in determining the discrete units of general mean-

ing. At this stage these meanings are those experienced and described

by the participant irrespective of whether they later are determined to

be essential, contextual, or tangential to the structure of the experience

of wonder.

It should also be noted that at times it is difficult to clearly and un-

ambiguously determine what constitutes the gestalt of

a

unit of general

283

Table

1. Units of general meaning.

'

I

was looking at Mary and

^ all

of a

sudden I knew ^I was looking at her

like I never looked at anybody in my

whole life

—

and *my eyes were sort

of just kind of staring at her and the

reason that ^I realized that it was

tremendous was that she said to me

—

what are you doing -

^

and I just said

I'm looking at you - ^and so we just

sat there and 'she sort of watched me

look at her - and 'she

was

getting kind

of uncomfortable *°and yet also kept

saying - what's going on "but not

really wanting to hear - ^^just letting

me

—

having enough sensitivity to let

me experience it -^ ^^a lot was going

on - *^I didn't realize what - what it

was -

^^ I

was just'sort of sitting

there - ^^I couldn't move - "i didn't

want to move -

^* I

just want to con-

tinue looking at her.

* Was looking at Mary

^ Suddenly he knew

^ He was looking at her like he never

looked at anybody in his whole life

His eyes were just staring at her

Realized it was tremendous when

she said "What are you doing?"

He just said, "I'm looking at you."

'' Both just sat there

She sort of watched him look at her

She was getting kind of uncomfort-

able

She kept saying "What's going on?"

She didn't seem to want a response

10

12

She had enough sensitivity to let

him experience it

13

14

IS

A lot was going on

He didn't realize what was going on

He continued to just sit there

^^ He couldn't move (emphasized)

Didn't want to move

Just wanted to continue looking

at her

18

284

meaning. For example, in looking at the statement "...all of a sudden

I knew I was looking at her like I never looked at anybody in my whole

life...',

it could be argued that actually this constitutes one whole unit

of general meaning rather than two as I have delineated it. Te context

is ambiguous and I would agree that this is a completely acceptable

altemative decision. Given different perspectives among phenome-

nological researchers there are bound to be minor differences even

when utilizing the same general method. The perspective I have used

in this case is to avoid the danger of potentially subsuming and there-

fore obscuring apparently separate meaning by deciding in all sig-

nificantly ambiguous instances to decide in the favor of separate

meanings. This can always be changed later on as the context becomes

clearer.

5.

Delineating units of meaning relevant to the

research

question. This

is the beginning of a very critical phase in the explication of data. Once

the units of general meaning have been noted, the researcher is ready

to address the research question to them. In other words, the researcher

addresses the research question to the units of general meaning to

determine whether what the participant has said responds to and il-

luminates the research question. If it appears to do so, then it is noted

as a unit of relevant meaning in a manner similar to the process in step

number four. It should also be noted that therefore statements which

are clearly irrelevant to the phenomenon being studied are not record-

ed. Again, if there is ambiguity or uncertainty at this time as to whether

a general unit of meaning is relevant to the research question, it is

always much better to "err" on the safe side and include it. Greater

clarity should emerge as more time is spent with the data and its

overall content as well as in dialogue with the impartial "judges" or

the research committee.

This obviously requires some kind of "judgment call" on the part

of the researcher, though if the researcher has done a good job of

bracketing presuppositions, is very open to the data, and yet utilizes

a rigorous approach, it would seem that the danger of inappropriate

subjective judgments creeping in would be minimal. However, to play

safe,

it will be recommended in the next step that the researcher train

an impartial panel of judges to carry out the above process and validate,

or modify, or invalidate, the units of relevant meaning elicited by the

researcher.

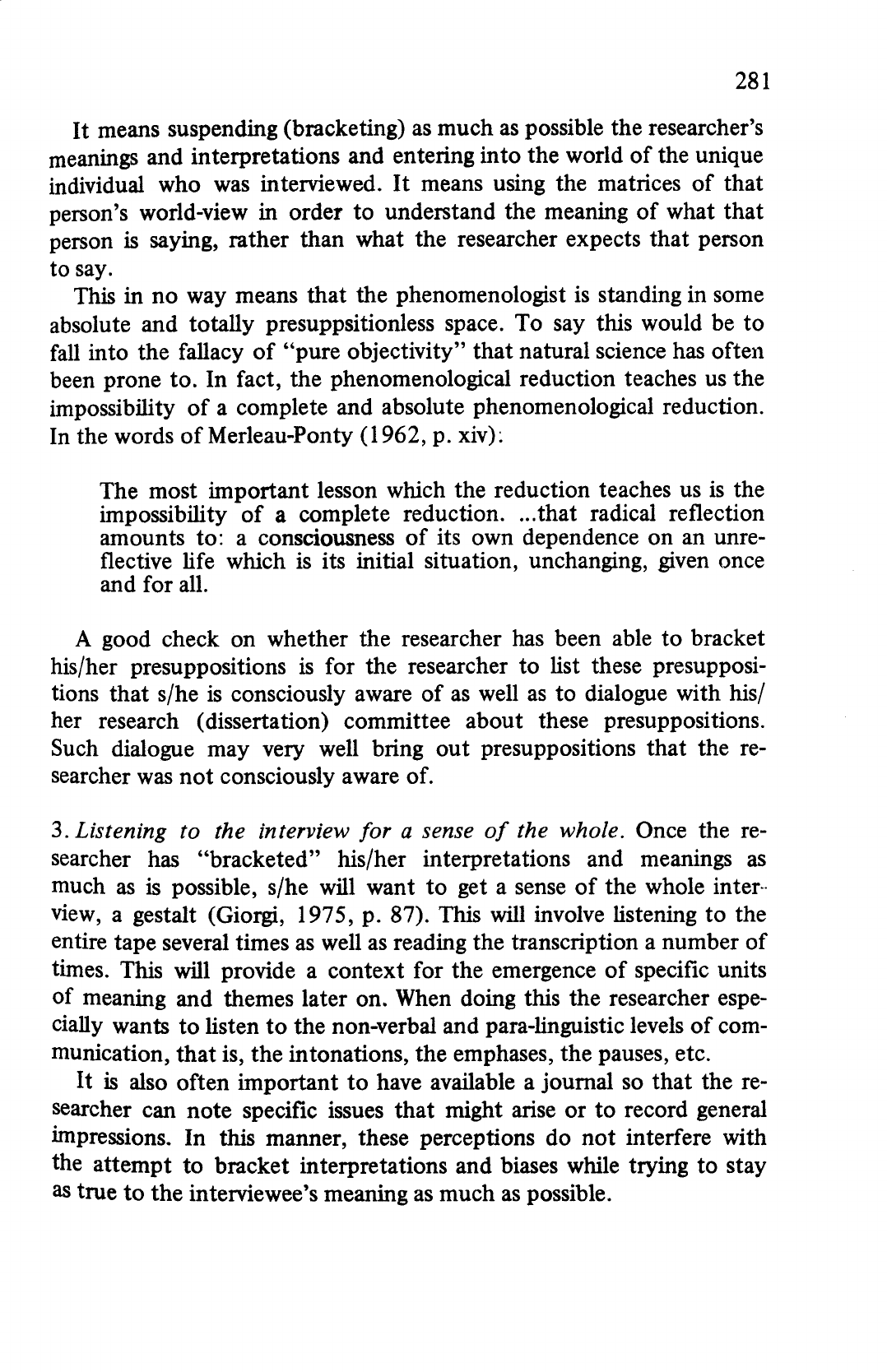

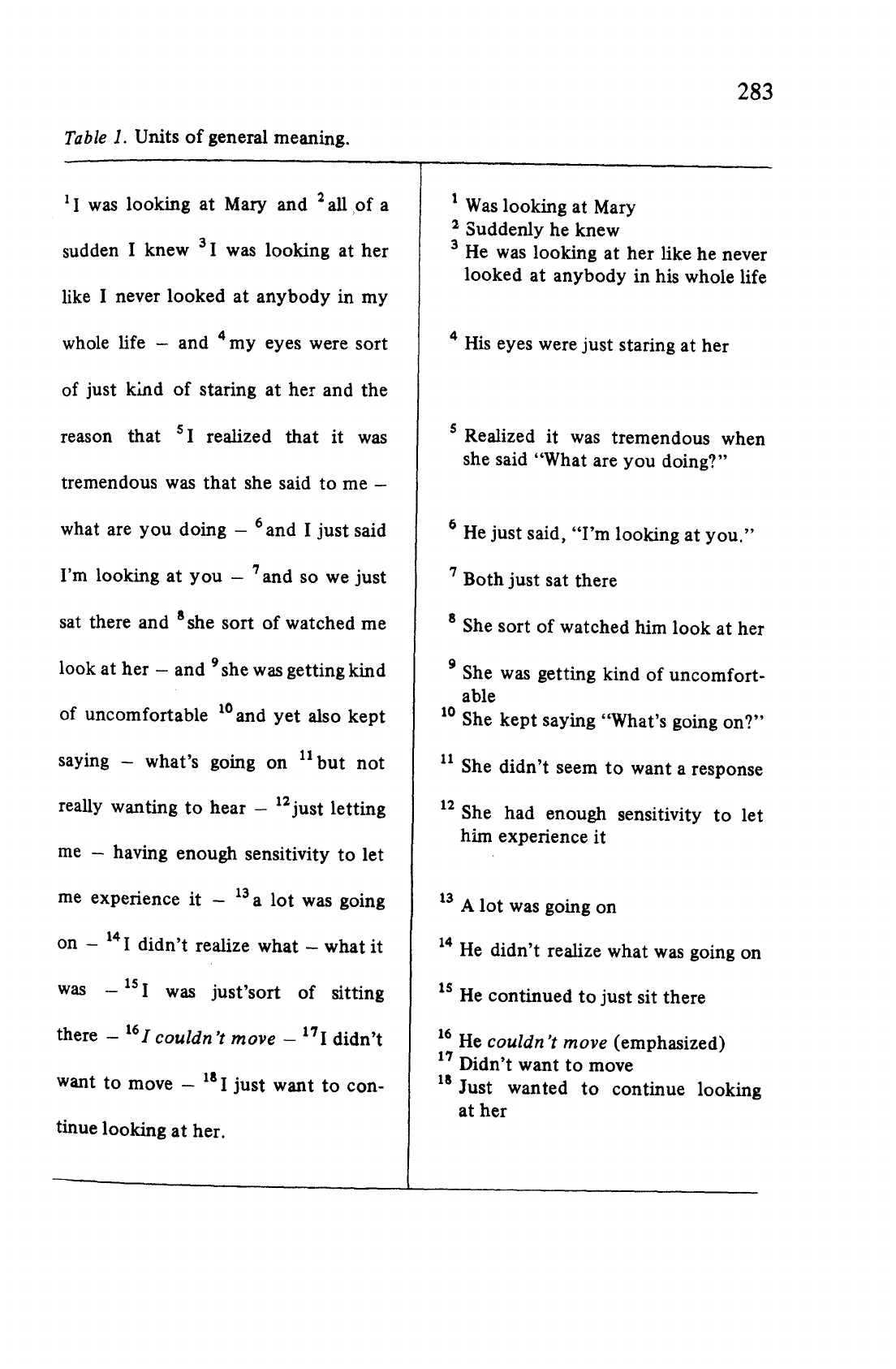

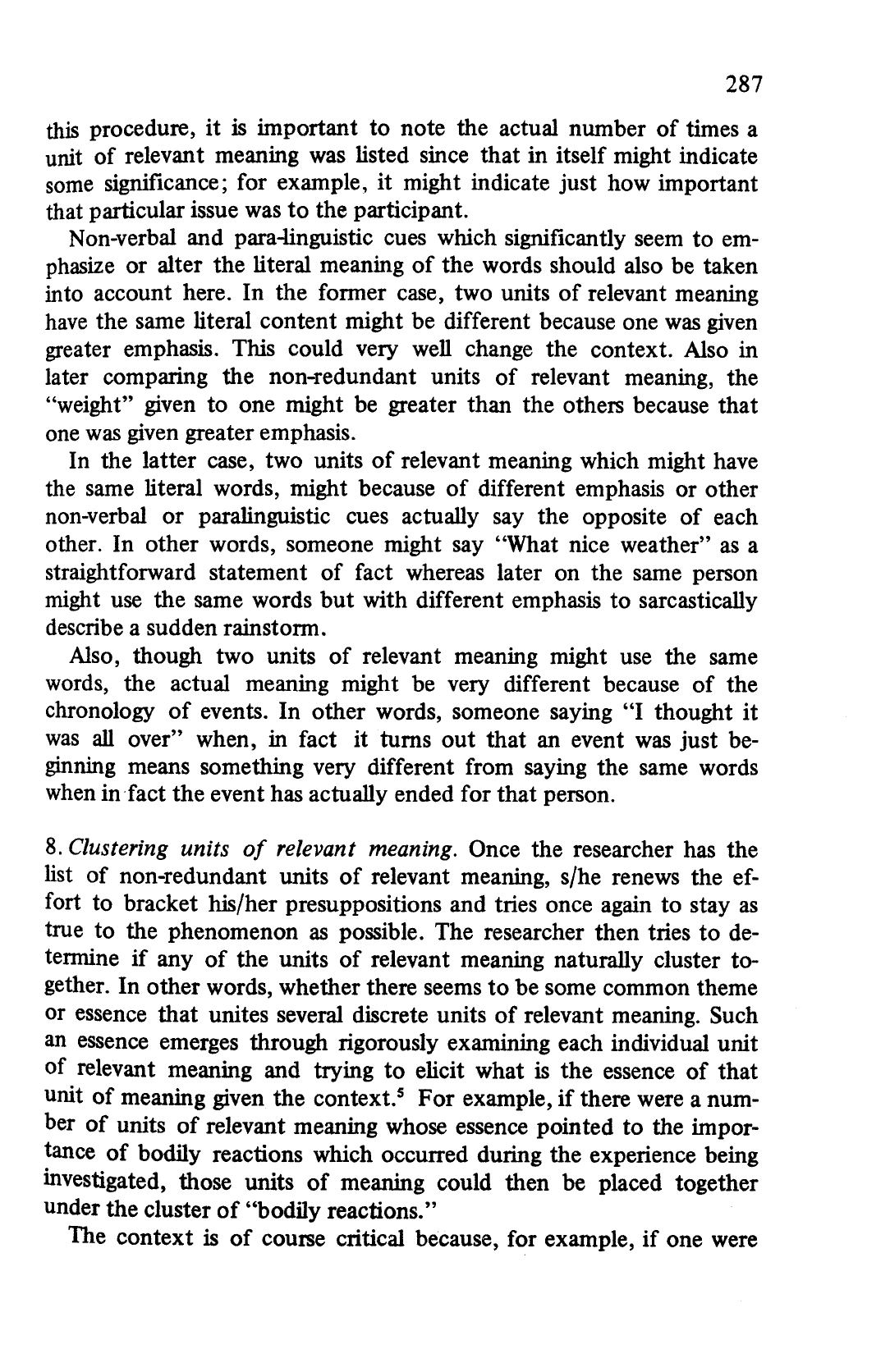

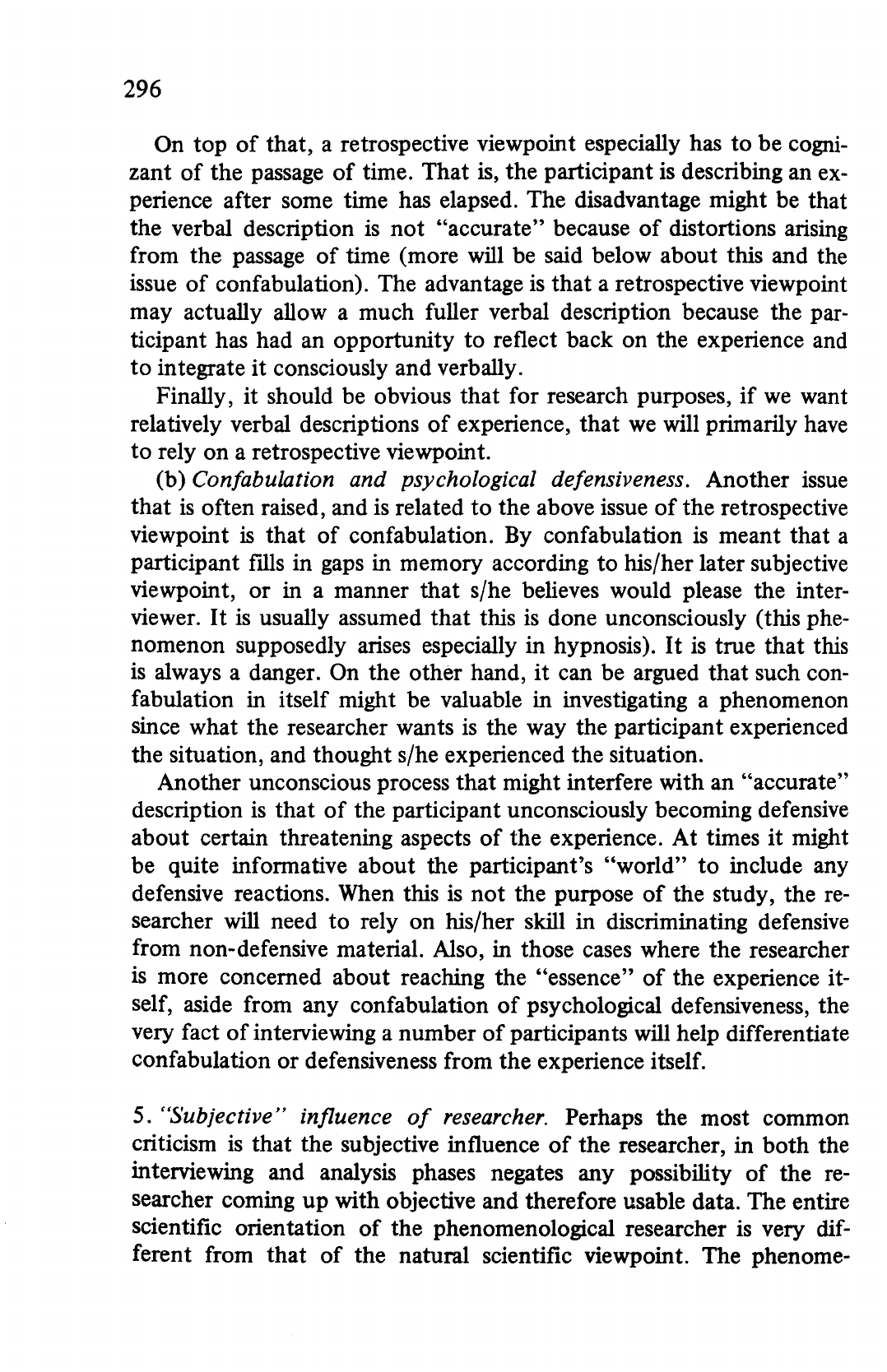

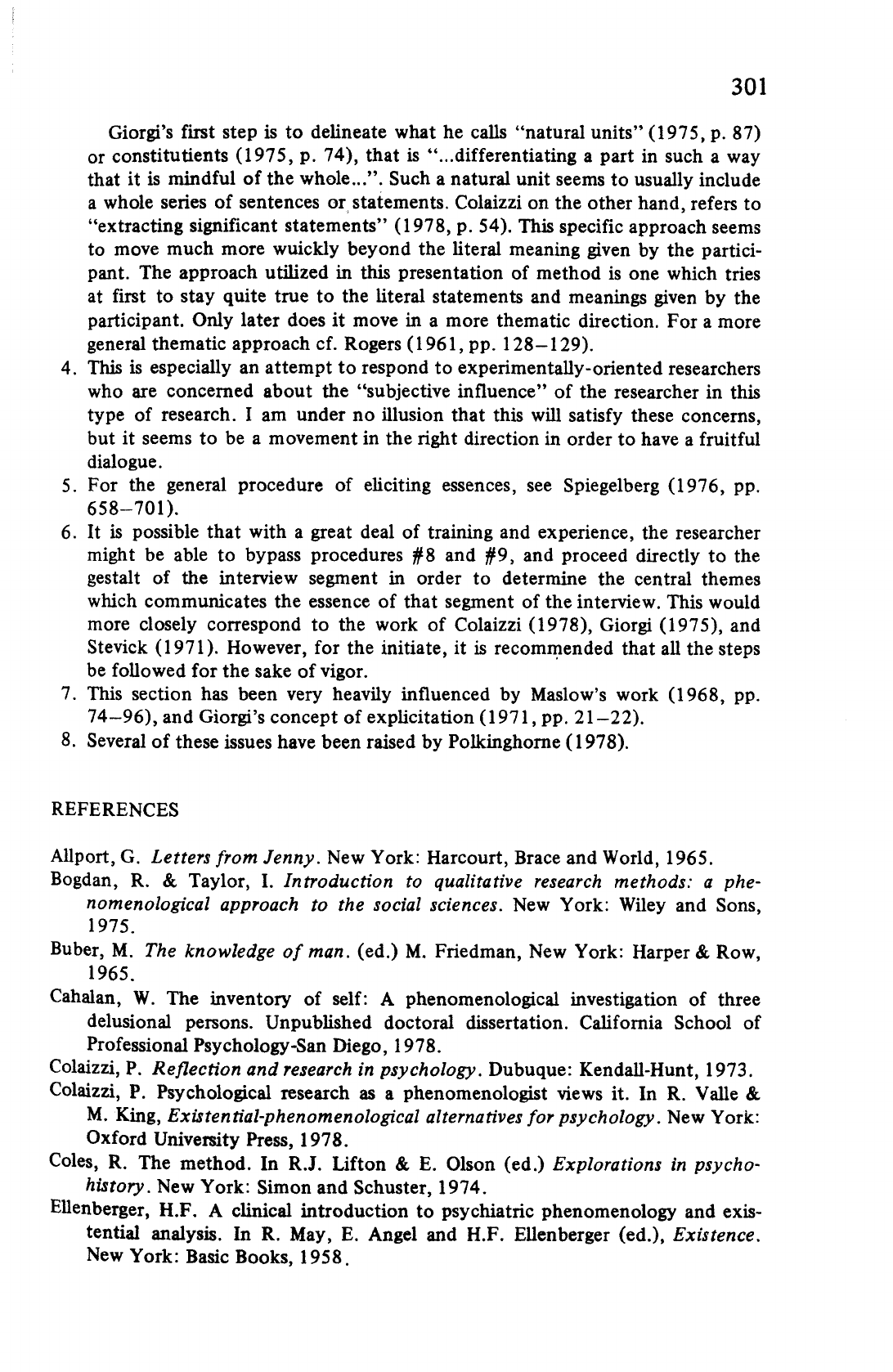

A brief example of delineating units of relevant meaning follows

(Table 2). The research question addressed to the units of general

285

Table

2. Units of relevant meaning.

^

Was looking at Mary.

^ Suddenly he knew.

^ He was looking at her like he never looked at anybody in his whole life.

* His eyes were just staring at her.

^ Realized it was tremendous when she said "What are you doing?"

^ He just said, "I.m looking at you."

•' Both just sat there.

^^ She had enough sensitivity to let him experience it.

*^

A

lot was going on.

^*

He didn't realize what was going on.

^^ He continued to just sit there.

**

He couldn't move

—

^^ Didn't want to move.

^*

Just wanted to continue looking at her.

meaning (Table 1) was: "Is this an essential constituent of the expe-

rience of wonder as experienced by this participant?" The control or

context used for determining the units of relevant meaning (for exam-

ple purposes) was only the segment cited in Table 1.

As was mentioned previously, whereas ordinarily each unit of general

meaning would be evaluated against the entire context of the interview

to determine the units of relevant meaning, a serious methodological

problem arises when looking at a segment (as done here only for

demonstration purposes) as if it were the entire context for each unit

of general meaning. The units of relevant meaning of a segment end up

being somewhat different than those which would emerge if the entire

context of the interview could be used as a control. Consequently, I

have erred on the side of inclusion in determining the units of relevant

meaning, using only this segment as the context and control.

At this point, the original eighteen units of general meaning have

been reduced to thirteen units of meaning relevant to the research

question (the original numeration of the units of general meaning

have been retained as much as possible so that the reader can follow

the sequence of decisions that is made throughout) Numbers eight

through eleven of Table 1 have been determined to be non-essential

to the stmcture of the experience of wonder. (This becomes even

clearer further in the interview). They have, therefore, been eliminated

from Table 2. There are question marks in front of numbers seven and

286

twelve because it is highly ambiguous within only the context of this

segment as to whether they are essential to the structure of the ex-

perience. At this early stage and working with only a segment of only

one interview it is much better to be overly inclusive than to exclude

something which might later prove important in a wider context. After

the researcher has had an opportunity to delineate the relevant mean-

ings from the entire interview as well as several other interviews, it will

become much clearer as to whether initially ambiguous units of general

meaning are essential to the research question. It should also be noted

that numbers sixteen and seventeen of Table 1 have been combined in

Table 2. In asking the research question (as well as in listening to the

tape) it appeared that what was essential was not the separate state-

ments, but that both occurred almost simultaneously in relation to each

other.

6. Training independent judges to verify the units of relevant

meaning.^

A good reliability check is to train other researchers to independently

carry out the above procedures in order to verify the present findings.

Such independent verification is a helpful check in further establishing

the rigor of the study. If there is significant agreement between the re-

searcher and the judges, then this indicates that the researcher has

bracketed his/her presuppositions and has been rigorous in his/her ap-

proach in explicating the data.

My experience in working with graduate students well-trained in

phenomenological research is that there are rarely significant differ-

ences in the findings. However, since there is no illusion of pure ob-

jectivity in this kind of research and since each person does bring in

his/her own different perspective, even when trained in these proce-

dures,

there are bound to be some minor differences. Such minor dif-

ferences can usually be quite easily worked out in dialogue between

the researcher and the judges. If there are significant enduring dif-

ferences in the findings, I would suggest that a research (dissertation)

committee be consulted to evaluate where the problem lies and how it

can be resolved.

7. Eliminating redundancies. When the above steps have been com-

pleted, the researcher is now ready to look over the list of units of rele-

vant meaning and eliminate those which are clearly redundant to

others previously listed. However, the researcher cannot just rely on

the literal content but must also rely on the number of times a meaning

was mentioned and how it was mentioned. In other words, in following

287

this procedure, it is important to note the actual number of times a

unit of relevant meaning was listed since that in itself might indicate

some significance; for example, it might indicate just how important

that particular issue was to the participant.

Non-verbal and para4inguistic cues which significantly seem to em-

phasize or alter the literal meaning of the words should also be taken

into account here. In the former case, two units of relevant meaning

have the same literal content might be different because one was given

greater emphasis. This could very well change the context. Also in

later comparing the non-redundant units of relevant meaning, the

"weight" given to one might be greater than the others because that

one was given greater emphasis.

In the latter case, two units of relevant meaning which might have

the same literal words, might because of different emphasis or other

non-verbal or paralinguistic cues actually say the opposite of each

other. In other words, someone might say "What nice weather" as a

straightforward statement of fact whereas later on the same person

might use the same words but with different emphasis to sarcastically

describe a sudden rainstorm.

Also,

though two units of relevant meaning might use the same

words, the actual meaning might be very different because of the

chronology of events. In other words, someone saying "I thought it

was all over" when, in fact it turns out that an event was just be-

ginning means something very different from saying the same words

when in fact the event has actually ended for that person.

8.

Clustering

units of relevant meaning. Once the researcher has the

list of non-redundant units of relevant meaning, s/he renews the ef-

fort to bracket his/her presuppositions and tries once again to stay as

true to the phenomenon as possible. The researcher then tries to de-

termine if any of the units of relevant meaning naturally cluster to-

gether. In other words, whether there seems to be some common theme

or essence that unites several discrete units of relevant meaning. Such

an essence emerges through rigorously examining each individual unit

of relevant meaning and trying to elicit what is the essence of that

unit of meaning given the context.^ For example, if there were a num-

ber of units of relevant meaning whose essence pointed to the impor-

tance of bodily reactions which occurred during the experience being

investigated, those units of meaning could then be placed together

under the cluster of "bodily reactions."

The context is of course critical because, for example, if one were

288

investigating bodily felt experiences during a sporting event, then there

actually might be several different clusters addressing bodily experi-

ences and giving further specificity. In fact, it is theoretically possible

that in any given interview, and given a certain context, that most

units of relevant meaning might actually be separate clusters. In prac-

tice though this rarely happens.

It should be pointed out that even more so than in any of the pre-

vious procedures that the judgment and skill of the researcher is in-

volved here. There is more room for "artistic" judgment here than

ever before. Colaizzi, in discussing a similar procedure states: Par-

ticularly in this step is the phenomenological researcher engaged in

something which cannot be precisely delineated, for here he is involved

in that ineffable thing known as creative insight." (1978, p. 59).

The major danger in this procedure is of course that since more of

the researcher's judgment comes into play here that the researcher's

presuppositions might interfere. The best check on this is to have

either the researcher's (dissertation) committee check on the process

or even better to train other independent judges to repeat the process

to see if they come up with the same clusters. In the latter case, as be-

fore,

any discrepancies should be resolved by the (dissertation) com-

mittee or an outside impartial panel.

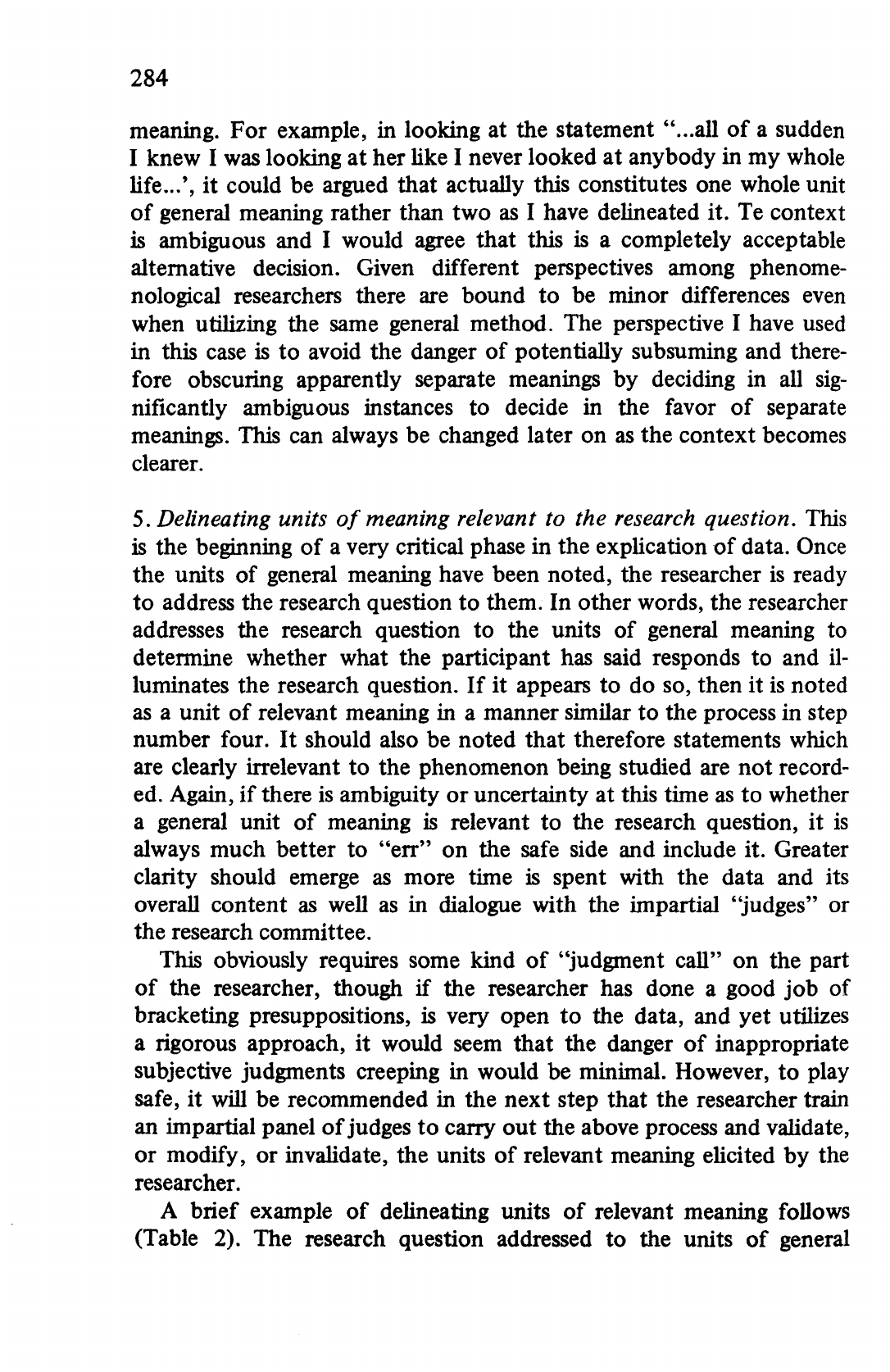

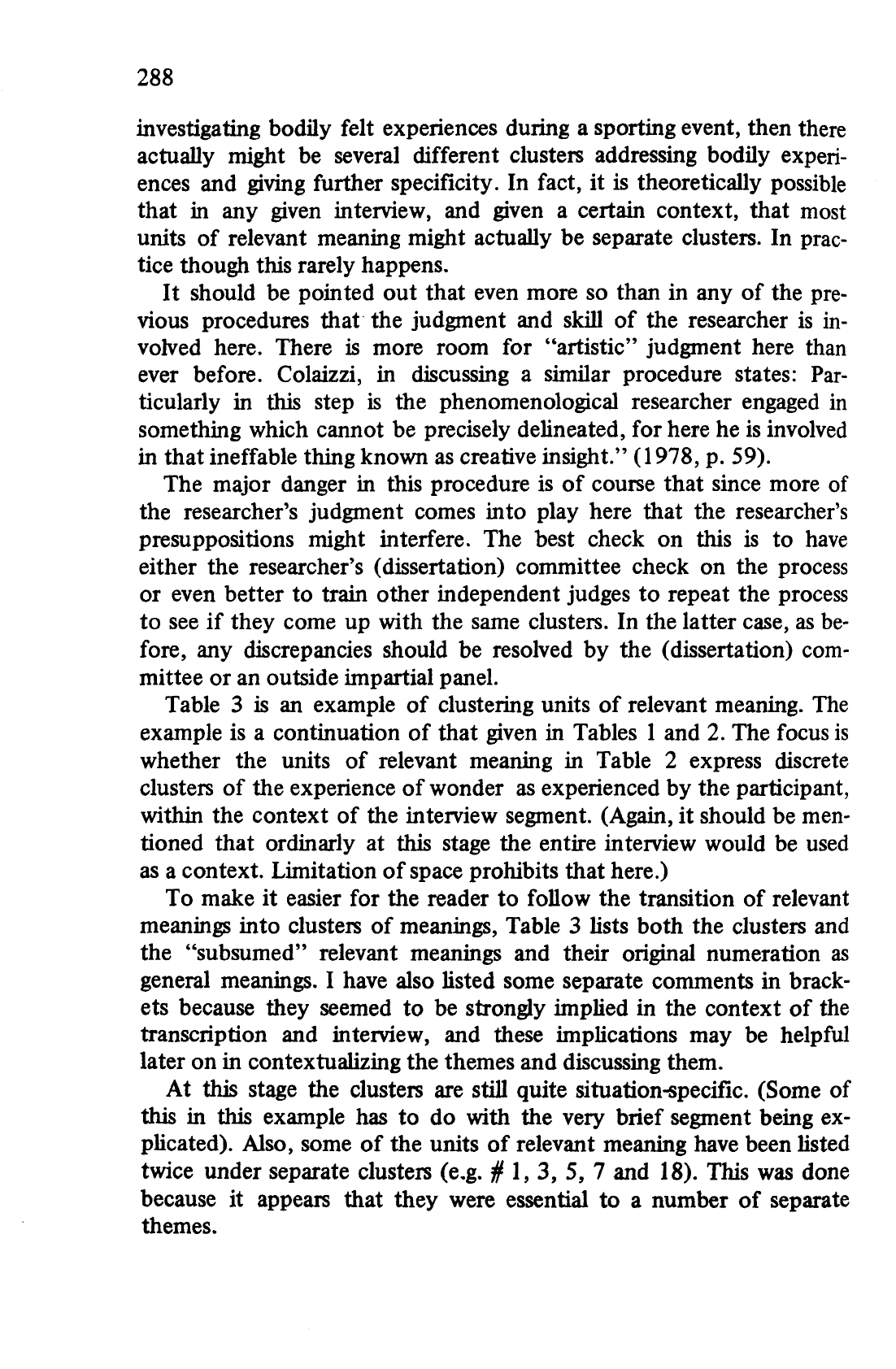

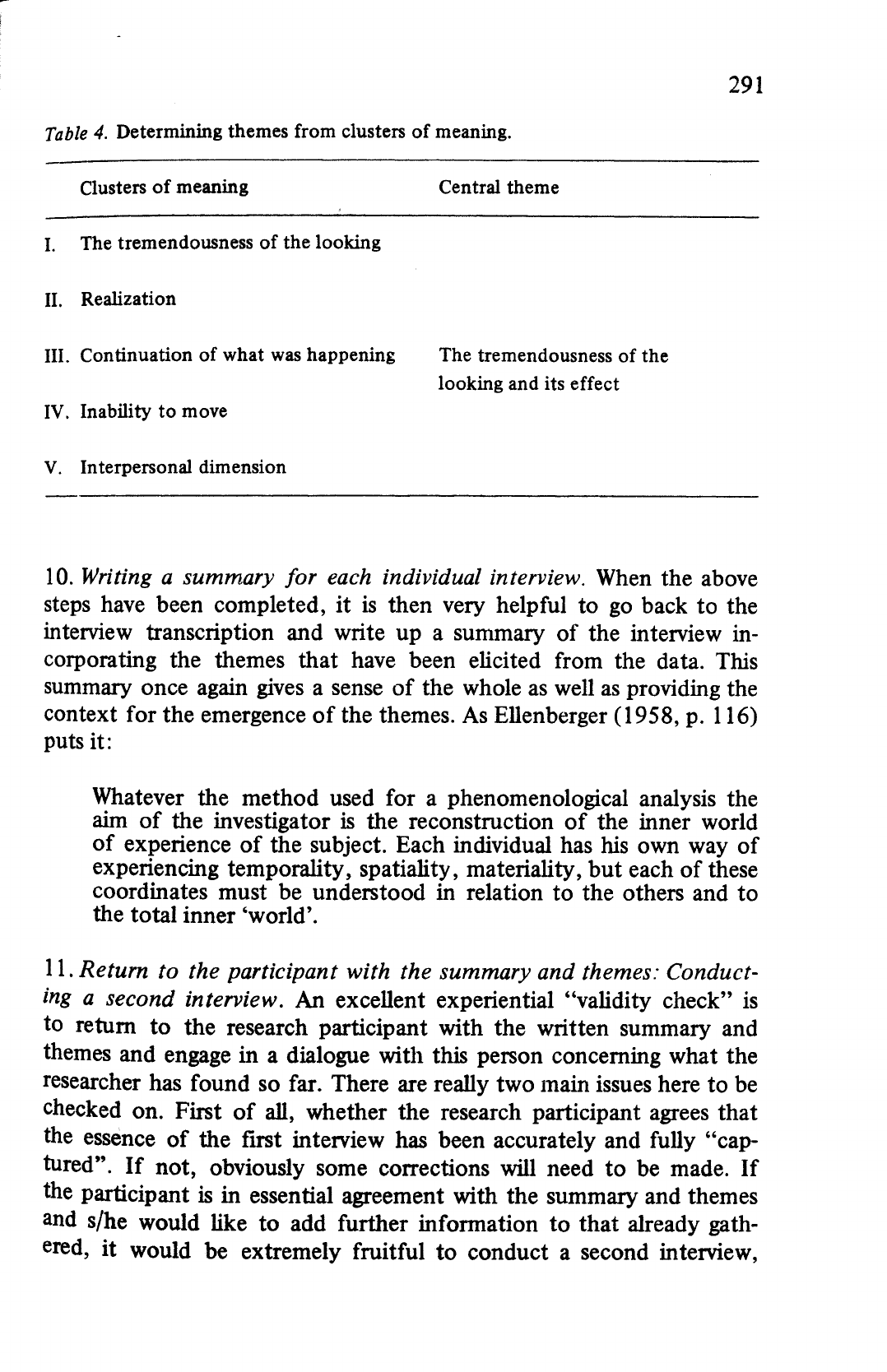

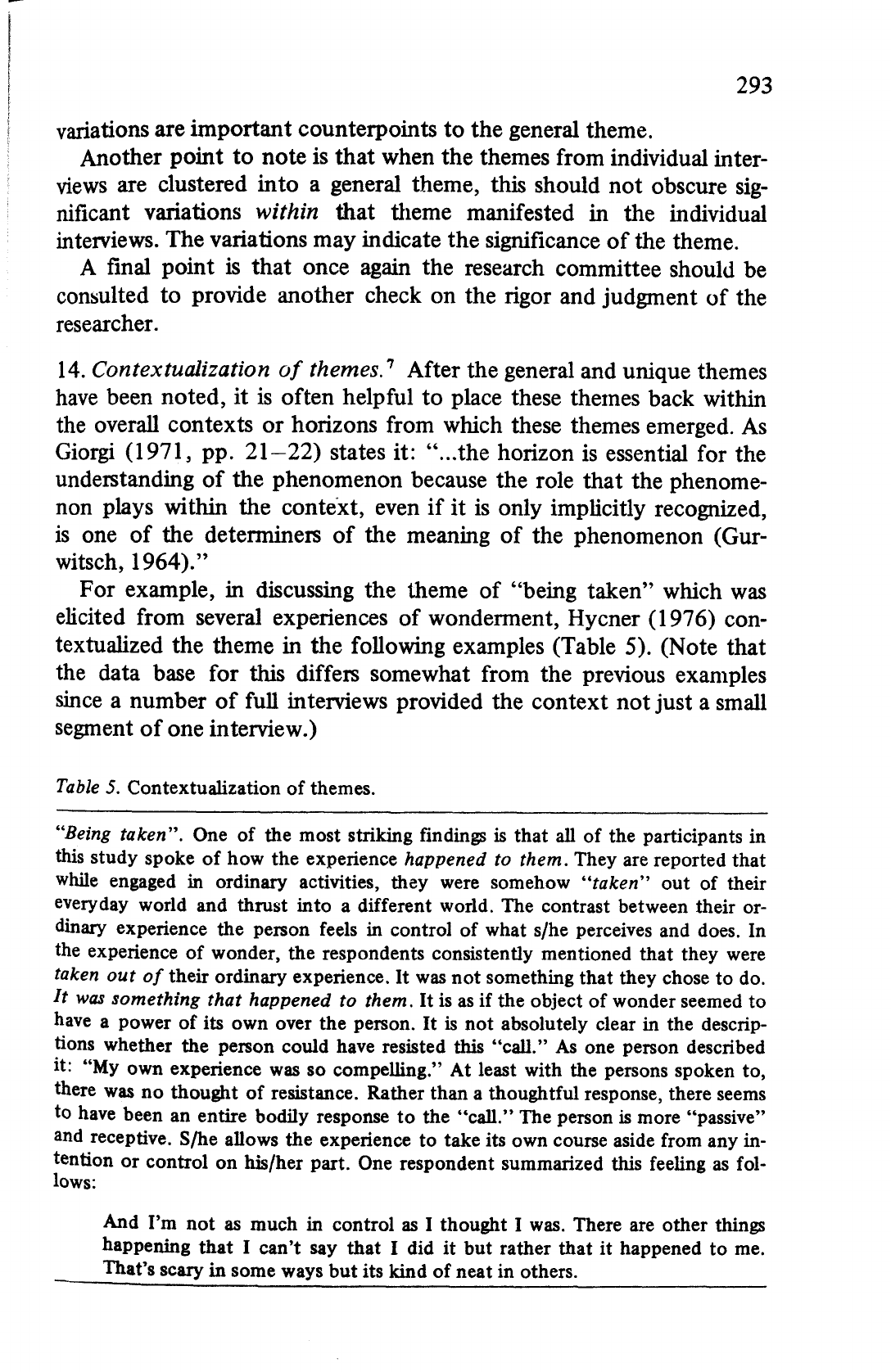

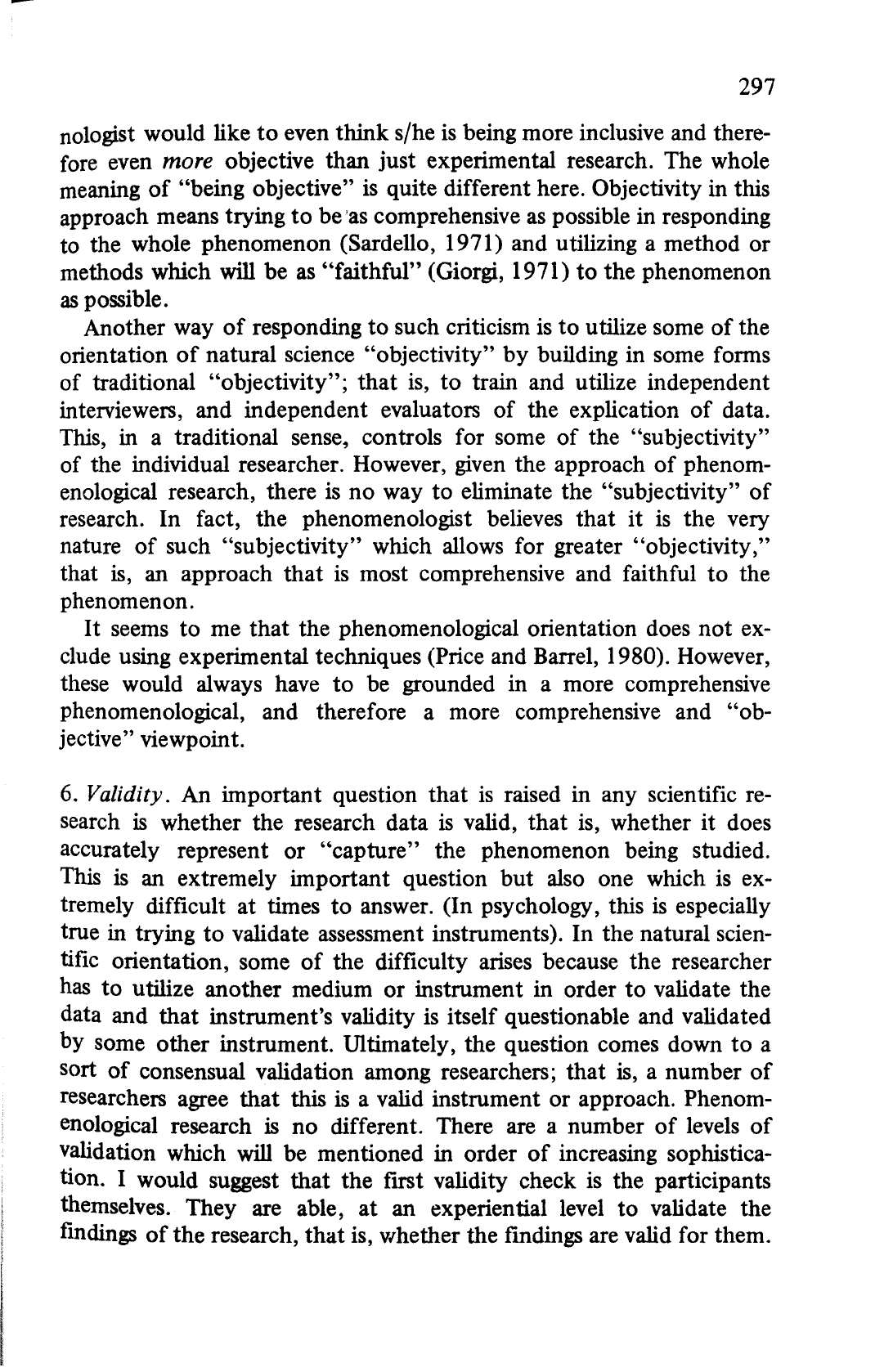

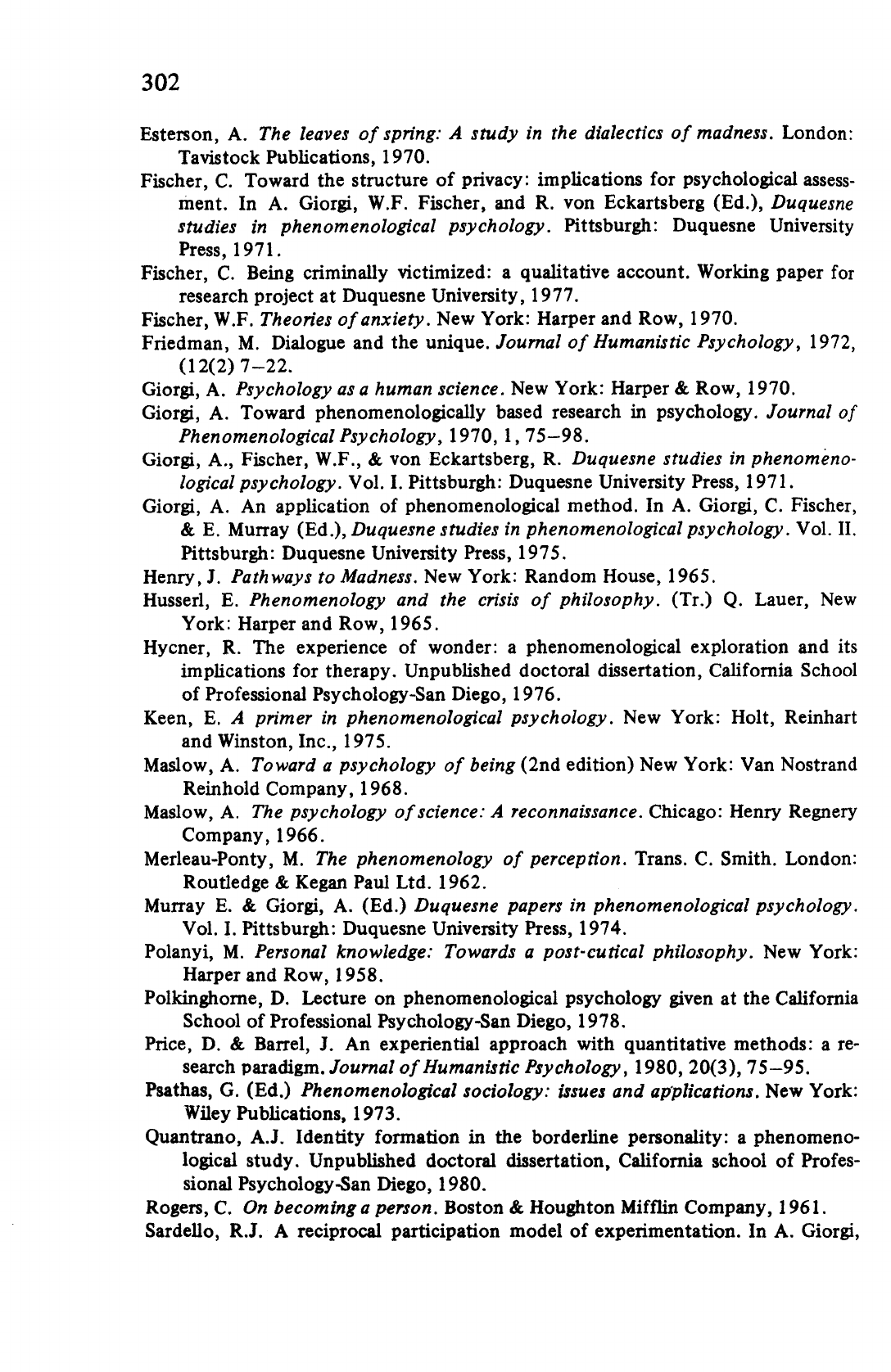

Table 3 is an example of clustering units of relevant meaning. The

example is a continuation of that given in Tables 1 and 2. The focus is

whether the units of relevant meaning in Table 2 express discrete

clusters of the experience of wonder as experienced by the participant,

within the context of the interview segment. (Again, it should be men-

tioned that ordinarly at this stage the entire interview would be used

as a context. Limitation of space prohibits that here.)

To make it easier for the reader to follow the transition of relevant

meanings into clusters of meaning. Table 3 lists both the clusters and

the "subsumed" relevant meanings and their original numeration as

general meanings. I have also listed some separate comments in brack-

ets because they ^emed to be strongly implied in the context of the

transcription and interview, and these implications may be helpful

later on in contextualizing the themes and discussing them.

At this stage the clusters are still quite situation-specific. (Some of

this in this example has to do with the very brief segment being ex-

plicated). Also, some of the units of relevant meaning have been listed

twice under separate clusters (e.g. # 1, 3, 5, 7 and 18). This was done

because it appears that they were essential to a number of separate

themes.

289

Table

3. Clusters of relevant meanings.

I. The tremendousness of the looking at

Mary

A. Looking at Mary in a way totally different than he had ever looked at any-

one in his life (#1, 3).

B.

His eyes were just staring (#4).

C. Realized it was tremendous when she said "Wat are you ding?" (f

5).

D.

Was Gust) looking at her (#6).

E. A lot was going on if 13).

F.

Just wanted to continue looking at her (#18).

II.

Realization

A. A sudden realization if 2) [Almost like it breaks in].

B.

Realized how tremendous it was (through her question), if 5)

C. A lot was going on and he didn't realize what was going on (# 13,14).

[rhythm of awareness].

III.

Continuation of what

was

happening

A.

Both just (continued) to sit there (#7).

B.

He continued to sit if 15).

IV. Inability to move

A.

Couldn 't

move (#16) [issue of volition].

B.

Didn't want to move (#17) [didn't desire to move].

V. Interpersonal dimension

A. Was looking at Mary in a way he had never looked at anyone in his whole

life (#1,3).

B.

Her question elicited the realization of how tremendous it was

C.

He

just said "I'm looking at you." (#6).

D.

Both just sat there (#7).

In Table 3, all the units of relevant meaning have been clustered to-

gether. The procedure utilized was that the researcher went back to

Table 2 (as well as having a sense of the entire interview segment) and

interrogated each individual meaning to determine its "essence". For

example, the "essence" of the unit of relevant meaning #

1

(Table 2)

was the "looking at Mary." In interrogating unit #2, there was some

question as to whether it was an essential part of the "looking at Mary"

cluster. In reviewing the context, it appeared to be a separate cluster

discrete from the "looking." At this stage, the essence seemed to have

more to do with the "knowing" or realization that occurred. In exam-

ining unit #3, the essence seemed to be the unusualness of the looking.

This unit begins to connect with unit #

1

around the cluster of "looking

290

at Mary." With units #4 and #5, the "unusualness" or "tremendous-

ness"

of the looking is re-emphasized. The above process is carried out

till it is seen that units #

1,

3,4, 5, 6,13,18 all seem to cluster together

around the issue of the "tremendousness of the looking at Mary."

The same procedure is then followed with the other units of relevant

meaning till they all come together as clusters. Table 3 lists all the

clusters of meaning.

In this procedure, there is a constant process of going back and forth

from the transcript to the units of relevant meaning to the clusters of

meaning. It should also be mentioned that sometimes it is quite diffi-

cult to decide which relevant meanings cluster together; for example

with #18, there was some difficulty deciding whether it clustered with

the "tremendousness" of the looking, or whether it would be better

clustered with a separate interpersonal dimension. It was finally de-

cided to include it under both. There was even some questions as to

whether to make an interpersonal dimension as a separate cluster. It

was finally decided to do so to err on the cautious side at this stage.

After the entire procedure was followed, there was a total of five

clusters of meaning. It should be noted that there is some ambiguity

as to where certain relevant meanings cluster and that there is some

overlap to the clusters. This is to be expected given that it is impos-

sible with human phenomena to totally delineate them. By their

nature, they are already an integral part of a whole and naturally co-

penetrate each other.

It should also be mentioned that another researcher might come

up with slightly different clusters. Given that there is more room for

different perspectives here and differing levels of skill and experience,

there are bound to be some differences of opinion.

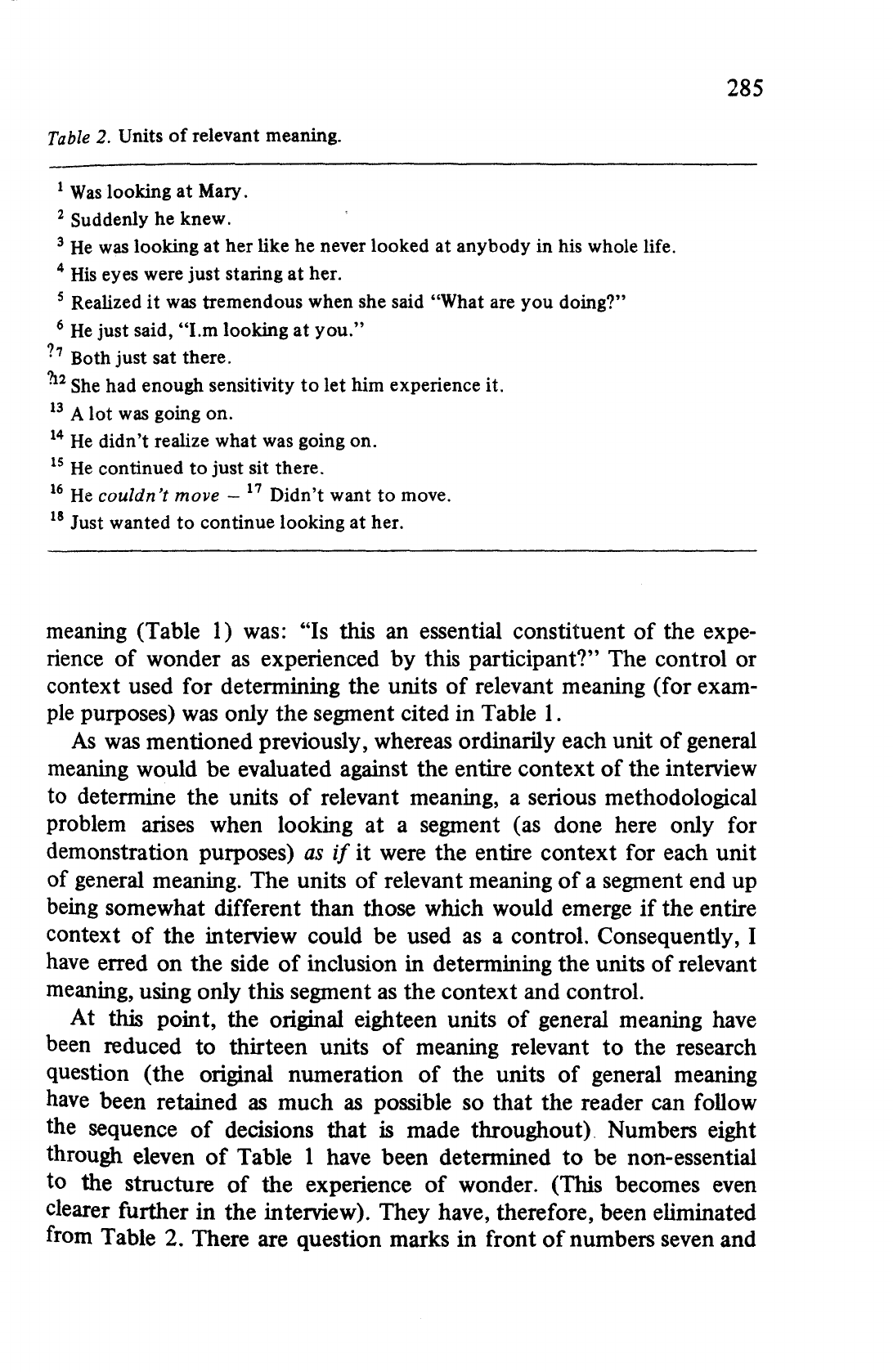

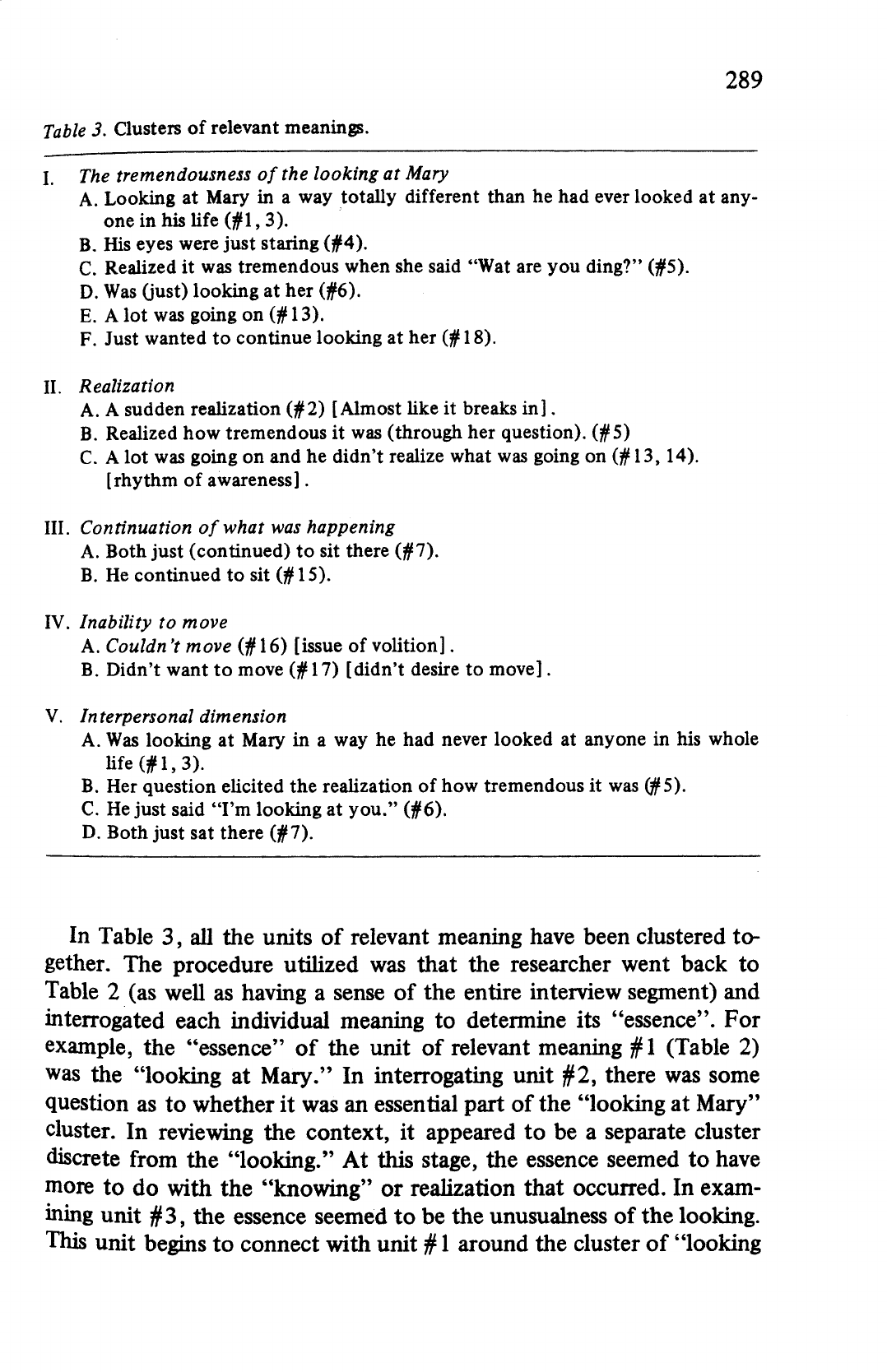

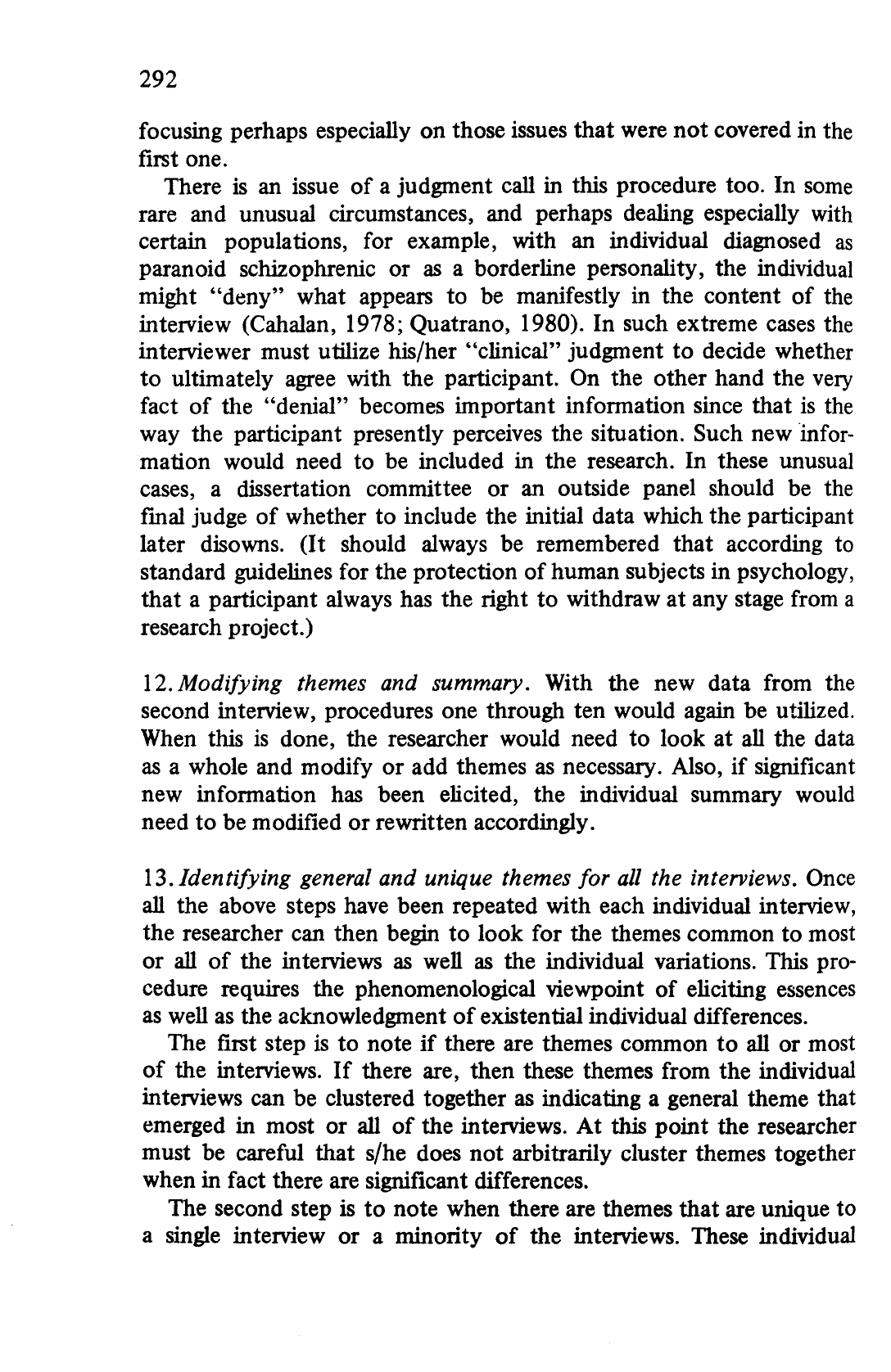

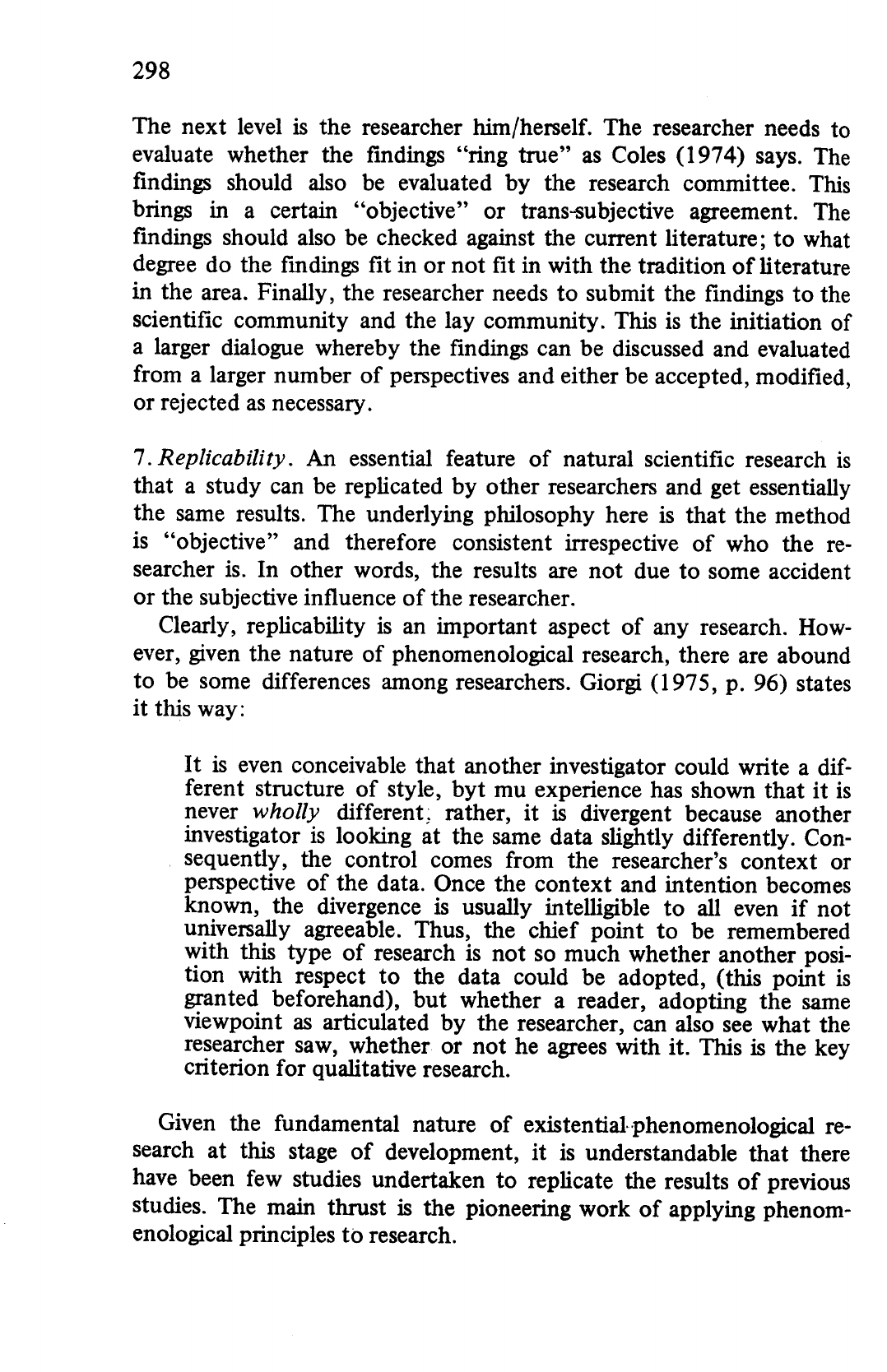

9. Determining themes from clusters of

meaning.

Finally at this stage,

the researcher interrogates all the clusters of meaning to determine if

there is one or more central themes which expresses the essence of

these clusters (and that portion of the transcript). In the example being

used, the researcher listed all the five clusters and tried to determine if

there was a central theme which expressed the essence of the clusters.

In going back and forth among the various clusters, it was determined

that the central theme was "The Tremendousness of the Looking and

its Effect" (Table 4). Obviously, more so than the previous ones, this

procedure addresses more of the gestalt of the relevant segment and

the clusters of meaning.*

291

Table

4.

Determining themes from clusters of meaning.

Clusters of meaning Central theme

I. The tremendousness of the looking

II.

Realization

in. Continuation of what was happening The tremendousness of the

looking and its effect

IV. Inability to move

V. Interpersonal dimension

10.

Writing a summary for each individual interview. When the above

steps have been completed, it is then very helpful to go back to the

interview transcription and write up a summary of the interview in-

corporating the themes that have been elicited from the data. This

summary once again gives a sense of the whole as well as providing the

context for the emergence of the themes. As Ellenberger (1958, p. 116)

puts it:

Whatever the method used for a phenomenological analysis the

aim of the investigator is the reconstruction of the inner world

of experience of the subject. Each individual has his own way of

experiencing temporality, spatiality, materiality, but each of tkese

coordinates must be understood in relation to the others and to

the total inner 'world'.

\\.Retum to the participant with the summary and themes: Conduct-

ing a second interview. An excellent experiential "validity check" is

to retum to the research participant with the written summary and

themes and engage in a dialogue with this person conceming what the

researcher has found so far. There are really two main issues here to be

checked on. First of all, whether the research participant agrees that

the essence of the first interview has been accurately and fully "cap-

tured". If not, obviously some corrections will need to be made. If

the participant is in essential agreement with the summary and themes

and s/he would like to add further information to that already gath-

ered, it would be extremely fruitful to conduct a second interview.

292

focusing perhaps especially on those issues that were not covered in the

first

one.

There is an issue of a judgment call in this procedure too. In some

rare and unusual circumstances, and perhaps dealing especially with

certain populations, for example, with an individual diagnosed as

paranoid schizophrenic or as a borderline personality, the individual

might "deny" what appears to be manifestly in the content of the

interview (Cahalan, 1978; Quatrano, 1980). In such extreme cases the

interviewer must utilize his/her "clinical" judgment to decide whether

to ultimately agree with the participant. On the other hand the very

fact of the "denial" becomes important information since that is the

way the participant presently perceives the situation. Such new infor-

mation would need to be included in the research. In these unusual

cases,

a dissertation committee or an outside panel should be the

final judge of whether to include the initial data which the participant

later disowns. (It should always be remembered that according to

standard guidelines for the protection of human subjects in psychology,

that a participant always has the right to withdraw at any stage from a

research project.)

\2.Modifying themes and summary. With the new data from the

second interview, procedures one through ten would again be utilized.

When this is done, the researcher would need to look at all the data

as a whole and modify or add themes as necessary. Also, if significant

new information has been elicited, the individual summary would

need to be modified or rewritten accordingly.

13.

Identifying general and unique themes for all the interviews. Once

all the above steps have been repeated with each individual interview,

the researcher can then begin to look for the themes common to most

or all of the interviews as well as the individual variations. This pro-

cedure requires the phenomenological viewpoint of eliciting essences

as well as the acknowledgment of existential individual differences.

The first step is to note if there are themes common to all or most

of the interviews. If there are, then these themes from the individual

interviews can be clustered together as indicating a general theme that

emerged in most or all of the interviews. At this point the researcher

must be careful that s/he does not arbitrarily cluster themes together

when in fact there are significant differences.

The second step is to note when there are themes that are unique to

a angle interview or a minority of the interviews. These individual

293

variations are important counterpoints to the general theme.

Another point to note is that when the themes from individual inter-

views are clustered into a general theme, this should not obscure sig-

nificant variations within that tlieme manifested in the individual

interviews. The variations may indicate the significance of the theme.

A final point is that once again the research committee should be

consulted to provide another check on the rigor and judgment of the

researcher.

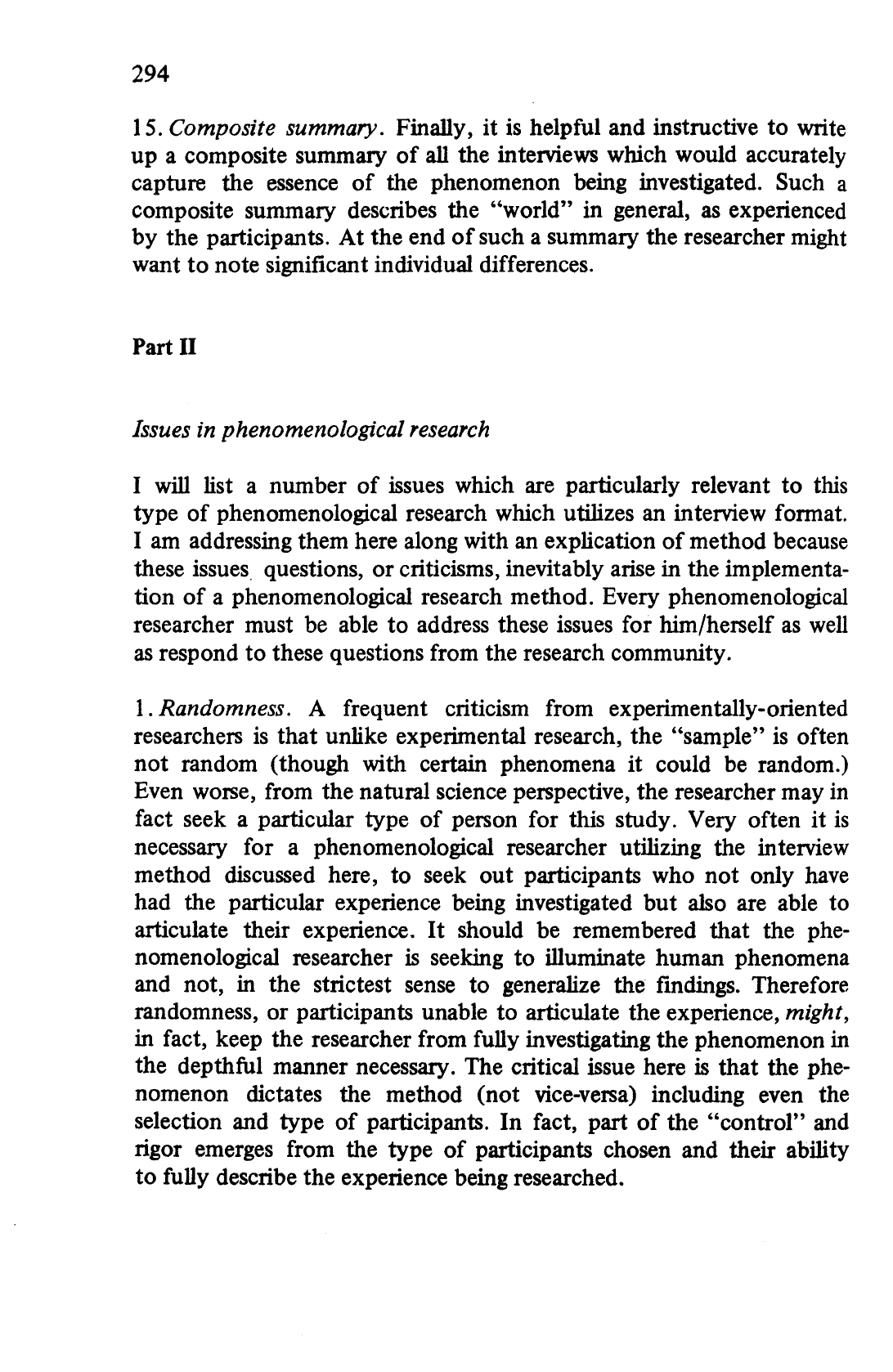

14.

Contextualization of

themes."^

After the general and unique themes

have been noted, it is often helpful to place these themes back within

the overall contexts or horizons from which these themes emerged. As

Giorgi

(1971,

pp. 21-22) states it: "...the horizon is essential for the

understanding of the phenomenon because the role that the phenome-

non plays within the context, even if it is only implicitly recognized,

is one of the determiners of the meaning of the phenomenon (Gur-

witsch, 1964)."

For example, in discussing the theme of "being taken" which was

elicited from several experiences of wonderment, Hycner (1976) con-

textualized the theme in the following examples (Table 5). (Note that

the data base for this differs somewhat from the previous examples

since a number of full interviews provided the context not just a small

segment of one interview.)

Table

5. Contextualization of themes.

"Being taken". One of the most striking findings is that all of the participants in

this study spoke of how the experience happened to them. They are reported that

while engaged in ordinary activities, they were somehow "taken" out of their

everyday world and thrust into a different world. The contrast between their or-

dinary experience the person feels in control of what s/he perceives and does. In

the experience of wonder, the respondents consistently mentioned that they were

taken out of their ordinary experience. It was not something that they chose to do.

It

was

something that happened to them. It is as if the object of wonder seemed to

have a power of its own over the person. It is not absolutely clear in the descrip-

tions whether the person could have resisted this "call." As one person described

it: "My own experience was so compelling." At least with the persons spoken to,

there was no thought of resistance. Rather than a thoughtful response, there seems

to have been an entire bodily response to the "call." The person is more "passive"

and receptive. S/he allows the experience to take its own course aside from any in-

tention or control on his/her part. One respondent summarized this feeling as fol-

lows:

And I'm not as much in control as I thought I was. There are other things

happening that I can't say that I did it but rather that it happened to me.

That's scary in some ways but its kind of neat in others.

294

15.

Composite summary. Finally, it is helpful and instructive to write

up a composite summary of all the interviews which would accurately

capture the essence of tiie phenomenon being investigated. Such a

composite summary describes the "world" in general, as experienced

by the participants. At the end of such a summary the researcher might

want to note significant individual differences.

Part II

Issues in phenomenological

research

I wiU list a number of issues which are particularly relevant to this

type of phenomenological research which utilizes an interview format.

I am addressing them here along with an explication of method because

these issues questions, or criticisms, inevitably arise in the implementa-

tion of a phenomenological research method. Every phenomenological

researcher must be able to address these issues for him/herself as well

as respond to these questions from the research community.

I. Randomness. A frequent criticism from experimentally-oriented

researchers is that unlike experimental research, the "sample" is often

not random (though with certain phenomena it could be random.)

Even worse, from the natural science perspective, the researcher may in

fact seek a particular type of person for this study. Very often it is

necessary for a phenomenological researcher utilizing the interview

method discussed here, to seek out participants who not only have

had the particular experience being investigated but also are able to

articulate their experience. It should be remembered that the phe-

nomenological researcher is seeking to illuminate human phenomena

and not, in the strictest sense to generalize the findings. Therefore

randomness, or participants unable to articulate the experience, might,

in fact, keep the researcher from fully investigating the phenomenon in

the depthful manner necessary. The critical issue here is that the phe-

nomenon dictates the method (not vice-versa) including even the

selection and type of participants. In fact, part of the "control" and

rigor emerges from the type of participants chosen and their ability

to fully describe the experience being researched.

295

2.

Limited number of participants. Doing this kind of phenomenologi-

cal research for the most part requires that only a limited number of

people be interviewed given the vast amount of data that emerges from

even one interview. The focus is of course on qualitative issues, not

quantitative ones.

3.

Generalizability. Another common criticism from experimentally-

oriented researchers is that as a consequence of the absence of random-

ness,

and the limited number of participants the results of the research

cannot be generalized and therefore are useless. In the strictest em-

pirical sense, the first part of the criticism is accurate in that the "re-

sults"

only apply strictly to the participants interviewed. I would sug-

gest that if they illuminate to some significant degree, the "worlds"

of the participants, then that in itself is valuable. However, in the pro-

cess of even investigating the experience of one unique individual we

can learn much about the phenomenology of human being in general.

Even within experimental research there is a long and respectable

history of studies done with a sample of one. Therefore, even with a

limited number of participants, though the results in a strict sense may

not be generalizable, they can be phenomenaologically informative

about human being in general.

4.

"Accuracy" of descriptions. A number of issues can be raised as

criticisms of the "accuracy" of the descriptions given by the partici-

pants.'

(a) Retrospective viewpoint, and the difficulty of

verbalizing

essen-

tially non-verbal experiences. One of the first criticisms that is often

raised is that interviewing a participant about a phenomenon elicits a

retrospective viewpoint. The criticism is that a retrospective viewpoint

is not the same as getting a description from someone while an ex-

perience is actually occurring. It is argued that a retrospective viewpoint

is altered by time and therefore different from the experience

itself.

I would argue that any description of an experience is already dif-

ferent from the experience

itself.

Language, by its nature can enhance

or distill an experience. In any case a description is not the experience

itself.

The best we can do through the medium of language is to be one

step removed from the original experience. Perhaps through non-verbal

mediums, such as painting, music, dance or visualization, we can come

closer to an original non-verbal experience. Even here, that is not the

experience

itself.

Consequently, a retrospective viewpoint has some

of the same shortcomings as even a concurrent description, given the

nature of language.

296

On

top of

that,

a

retrospective viewpoint especially

has to be

cogni-

zant

of the

passage

of

time. That

is, the

participant

is

describing

an ex-

perience after some time

has

elapsed.

The

disadvantage might

be

that

the verbal description

is not

"accurate" because

of

distortions arising

from

the

passage

of

time (more will

be

said below about this

and the

issue

of

confabulation).

The

advantage

is

that

a

retrospective viewpoint

may actually allow

a

much fuller verbal description because

the par-

ticipant

has had an

opportunity

to

reflect back

on the

experience

and

to integrate

it

consciously

and

verbally.

Finally,

it

should

be

obvious that

for

research purposes,

if we

want

relatively verbal descriptions

of

experience, that

we

will primarily have

to rely

on a

retrospective viewpoint.

(b) Confabulation

and

psychological defensiveness. Another issue

that

is

often raised,

and is

related

to the

above issue

of the

retrospective

viewpoint

is

that

of

confabulation.

By

confabulation

is

meant that

a

participant fills

in

gaps

in

memory according

to

his/her later subjective

viewpoint,

or in a

manner that

s/he

believes would please

the

inter-

viewer.

It is

usually assumed that this

is

done unconsciously (this

phe-

nomenon supposedly arises especially

in

hypnosis).

It is

true that this

is always

a

danger.

On the

other hand,

it can be

argued that such

con-

fabulation

in

itself might

be

valuable

in

investigating

a

phenomenon

since what

the

researcher wants

is the way the

participant experienced

the situation,

and

thought

s/he

experienced

the

situation.

Another unconscious process that might interfere with

an

"accurate"

description

is

that

of the

participant unconsciously becoming defensive

about certain threatening aspects

of the

experience.

At

times

it

might

be quite informative about

the

participant's "world"

to

include

any

defensive reactions. When this

is not the

purpose

of the

study,

the re-

searcher will need

to

rely

on

his/her skill

in

discriminating defensive

from non-defensive material. Also,

in

those cases where

the

researcher

is more concemed about reaching

the

"essence"

of the

experience

it-

self,

aside from

any

confabulation

of

psychological defensiveness,

the

very fact

of

interviewing

a

number

of

participants will help differentiate

confabulation

or

defensiveness from

the

experience

itself.

5.

"Subjective" influence

of

researcher.

Perhaps

the

most common

criticism

is

that

the

subjective influence

of the

researcher,

in

both

the

interviewing

and

analysis phases negates

any

possibility

of the re-

searcher coming

up

with objective

and

therefore usable data.

The

entire

scientific orientation

of the

phenomenological researcher

is

very

dif-

ferent from that

of the

natural scientific viewpoint.

The

phenome-

297

nologist would like to even think s/he is being more inclusive and there-

fore even more objective than just experimental research. The whole

meaning of "being objective" is quite different here. Objectivity in this

approach means trying to be as comprehensive as possible in responding

to the whole phenomenon (Sardello, 1971) and utilizing a method or

methods which will be as "faithful" (Giorgi, 1971) to the phenomenon

as possible.

Another way of responding to such criticism is to utilize some of the

orientation of natural science "objectivity" by building in some forms

of traditional "objectivity"; that is, to train and utilize independent

interviewers, and independent evaluators of the explication of data.

This,

in a traditional sense, controls for some of the "subjectivity"

of the individual researcher. However, given the approach of phenom-

enological research, there is no way to eliminate the "subjectivity" of

research. In fact, the phenomenologist believes that it is the very

nature of such "subjectivity" which allows for greater "objectivity,"

that is, an approach that is most comprehensive and faithful to the

phenomenon.

It seems to me that the phenomenological orientation does not ex-

clude using experimental techniques (Price and Barrel, 1980). However,

these would always have to be grounded in a more comprehensive

phenomenological, and therefore a more comprehensive and "ob-

jective" viewpoint.

6. Validity. An important question that is raised in any scientific re-

search is whether the research data is valid, that is, whether it does

accurately represent or "capture" the phenomenon being studied.

This is an extremely important question but also one which is ex-

tremely difficult at times to answer. (In psychology, this is especially

true in trying to validate assessment instruments). In the natural scien-

tific orientation, some of the difficulty arises because the researcher

has to utilize another medium or instrument in order to validate the

data and that instrument's validity is itself questionable and validated

by some other instrument. Ultimately, the question comes down to a

sort of consensual validation among researchers; that is, a number of

researchers agree that this is a valid instrument or approach. Phenom-

enological research is no different. There are a number of levels of

validation which will be mentioned in order of increasing sophistica-

tion. I would suggest that the first validity check is the participants

themselves. They are able, at an experiential level to validate the

findings of the research, that is, v/hether the findings are valid for them.

298

The next level is the researcher him/herself. The researcher needs to

evaluate whether the findings "ring true" as Coles (1974) says. The

findings should also be evaluated by the research committee. This

brings in a certain "objective" or trans-subjective agreement. The

findings should also be checked against the current literature; to what

degree do the findings fit in or not fit in with the tradition of literature

in the area. Finally, the researcher needs to submit the findings to the

scientific community and the lay community. This is the initiation of

a larger dialogue whereby the findings can be discussed and evaluated

from a larger number of perspectives and either be accepted, modified,

or rejected as necessary.

1.

Replicability. An essential feature of natural scientific research is

that a study can be replicated by other researchers and get essentially

the same results. The underlying philosophy here is that the method

is "objective" and therefore consistent irrespective of who the re-

searcher is. In other words, the results are not due to some accident

or the subjective influence of the researcher.

Clearly, replicability is an important aspect of any research. How-

ever, given the nature of phenomenological research, there are abound

to be some differences among researchers. Giorgi (1975, p. 96) states

it this way:

It is even conceivable that another investigator could write a dif-

ferent structure of style, byt mu experience has shown that it is

never wholly different, rather, it is divergent because another

investigator is looking at the same data sli^tly differently. Con-

sequently, the control comes from the researcher's context or

perspective of the data. Once the context and intention becomes

known, the divergence is usually intelligible to all even if not

universally agreeable. Thus, the chief point to be remembered

with this type of research is not so much whether another posi-

tion with respect to the data could be adopted, (this point is

granted beforehand), but whether a reader, adopting the same

viewpoint as articulated by the researcher, can also see what the

researcher saw, whetiher or not he agrees with it. This is the key

criterion for qualitative research.

Given the fundamental nature of existential phenomenological re-

search at this stage of development, it is understandable that there

have been few studies undertaken to replicate the results of previous

studies. The main thrust is the pioneering work of applying phenom-

enological principles to research.

299

Clearly much needs to be done in terms of "replicating" studies.

However, the phenomenological researcher is not willing to fall into

the natural scientific error of trying to have such a meticulously "ob-

jective" and therefore replicable method that there ends up an inverse

relationship between the replicability of results and the meaningfulness

of the findings. A balance must be stmck between the two.

8.

Absence of control

groups.

Some natural scientific researchers have

suggested that if there are no control groups then a study can't be

scientific. The very narrow understanding of science is obvious here

and has been addressed elsewhere. Also, it seems patently absurd to

suggest that there could be some way of controlling for a person's

experience when what the phenomenological researcher is primarily

concemed about is the investigation of the very uniqueness of human

experience.

9.

Absence of hypotheses. Another stalwart feature of experimental

research is the testing of hypotheses. What experimental researchers

fail to make explicit enough is where these hypotheses come from.

For the most part they come from such "unscientific" experiences

as hunches, intuitions, insights, suspicions, etc. (Maslow, 1969). There

is a certain "dishonesty" built into the whole "face objectivity" of

stating hypotheses. Also, the phenomenological researcher has the op-

posite orientation. That is, s/he wants to be as open to the phenomenon

as possible without constricting his/her perspective by placing the phe-

nomenon on the promethian bed of hypothesis testing. In a sense, the

phenomenologist is working with a "null-null hypothesis". Maslow

(1969) suggests that often such foundational work is done, it might

be appropriate to later test certain aspects of the findings bu generating

hypotheses which can later be experimentally verified.

10.

Absence of prediction. It should be obvious that the phenom-

enologist does not believe that the most meaningful aspects of human

beings can be predicted. That which can be "predicted" is often very

trival or in such a broad range as to be meaningless. The phenomenolo-

gist is more concemed with a comprehensive and d(pthful under-

standing of a phenomenon. S/he believes that this will advance science

and human good will to a far greater extent than will the dimension of

"predictability" per se.

300

ll.Absence of "interpretation" and comprehensive theory. Obvious

too,

is the fact that the phenomenological researcher's primary thrust

is to understand, and as much as possible not to interpret according

to some laready developed theory. The latter is the kind of reduction-

ism that the phenomenologist is most concemed about avoiding since

it has been such a serious error in much traditional research.

Phenomenology is still relatively new and still at a foundational

stage and there is not enough of a body of knowledge to attempt a

more comprehensive integration of theory. Also, at the core of phe-

nomenology is the very deep respect for the uniqueness of human ex-

perience and that this ever present uniqueness will always make the

attempt to develop a totally comprehensiveness theory of human ex-

perience an ultimately futile one. It is the uniqueness of the human

being which constantly instills novelty and unpredictability into any

attempt to totally and comprehensively "capture" the phenomenon

of human experience.

NOTES

1.

I have initially used the term "analysis" here though it has some dangerous

implications. The term usually means a "breaking into parts" and therefore

often means a loss of the whole phenomenon. Giorgi avoids this danger by

using the term "explidtation", which means an investigation of the consti-

tuents of a phenomenon while always keeping the context of the whole. I

have decided not to use this term initially because of the lack of familiarity of

most readers with it. Also, there is a tradition of using the phrase "phenome-

nological analysis" in such writers as Binswanger, Boss and May, where an

analysis of the constituents of the phenomenon does not detract from the

whole phenomenon. Later in the article I will use the terms interchangeably.

2.

A word of caution is needed here to note that perhaps the terminology "phe-

nomenological reduction" coined by Husserl is unfortunate. The term and ap-

proach has nothing to do with reductionistic tendencies in some natural science

methods, that is, a tendency to do a great injustice to human phenomena by

over-analyzing them, removing them from their lived context, and reducing

them to simple cause and effect components. The utilization of the phenome-

nological reduction is to bring about quite the opposite result, to be as true to

the phenomenon as possible, without any premature imposition of theoretical

constraints.

3.

It should be noted that this section and the following one, in particular, are

heavily dependent on the pioneering work of Giorgi (1975, pp. 74, 87—91)

and Colaizzi (1978, pp. 59-61). However, it should also be mentioned that

there are some significant differences in terminology and specificity of method

which could cause confusion.

301

Giorgi's first step is to delineate what he calls "natural units" (1975, p. 87)

or constitutients (1975, p. 74), that is "...differentiating a part in such a way

that it is mindful of the whole...". Such a natural unit seems to usually include

a whole series of sentences or statements. Colaizzi on the other hand, refers to

"extracting significant statements" (1978, p. 54). This specific approach seems

to move much more wuickly beyond the literal meaning given by the partici-

pant. The approach utilized in this presentation of method is one which tries

at first to stay quite true to the literal statements and meanings given by the

participant. Only later does it move in a more thematic direction. For a more

general thematic approach cf. Rogers

(1961,

pp. 128-129).

4.

This is especially an attempt to respond to experimentally-oriented researchers

who are concemed about the "subjective influence" of the researcher in this

type of research. I am under no illusion that this will satisfy these concerns,

but it seems to be a movement in the right direction in order to have a fruitful

dialogue.

5.

For the general procedure of eliciting essences, see Spiegelberg (1976, pp.

658-701).

6. It is possible that with a great deal of training and experience, the researcher

might be able to bypass procedures #8 and #9, and proceed directly to the

gestalt of the interview segment in order to determine the central themes

which communicates the essence of that segment of the interview. This would

more closely correspond to the work of Colaizzi (1978), Giorgi (1975), and

Stevick (1971). However, for the initiate, it is recomrnended that all the steps

be followed for the sake of vigor.

7.

This section has been very heavily influenced by Maslow's work (1968, pp.

74-96),

and Giorgi's concept of explicitation

(1971,

pp. 21-22).

8. Several of these issues have been raised by Polkinghome (1978).

REFERENCES

Allport, G. Letters from Jenny. New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1965.

Bogdan, R. & Taylor, I. Introduction to qualitative research methods: a phe-

nomenological approach to the social sciences. New York: Wiley and Sons,

1975.

Buber, M. The knowledge of man. (ed.) M. Friedman, New York: Harper

&

Row,

1965.

Cahalan, W. The inventory of

self:

A phenomenological investigation of three

delusional persons. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. California School of

Professional Psychology-San Diego, 1978.

Colaizzi, P. Reflection and

research

in psychology. Dubuque: Kendall-Hunt, 1973.

Colaizzi, P. Psychological research as a phenomenologist views it. In R. Valle &

M. King, Existential-phenomenological

alternatives

for psychology. New York:

Oxford University Press, 1978.

Coles,

R. The method. In R.J. Lifton & E. Olson (ed.) Explorations in psycho-

history. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1974.

Ellenberger, H.F. A clinical introduction to psychiatric phenomenology and exis-

tential analysis. In R. May, E. Angel and H.F. Ellenberger (ed.), Existence.

New York: Basic Books, 1958.

302

Esterson, A. The leaves of

spring:

A study in the dialectics of

madness.

London:

Tavistock Publications, 1970.

Fischer, C. Toward the structure of privacy: implications for psychological assess-

ment. In A. Giorgi, W.F. Fischer, and R. von Eckartsberg (Ed.), Duquesne

studies in phenomenological psychology. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University

Press,

1971.

Fischer, C. Being criminally victimized: a qualitative account. Working paper for

research project at Duquesne University, 1977.

Fischer, W.F. Theories of anxiety. New York: Harper and Row, 1970.

Friedman, M. Dialogue and the unique. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 1972,

(12(2)7-22.

Giorgi, A. Psychology

as a

human science. New York: Harper & Row, 1970.

Giorgi, A. Toward phenomenologically based research in psychology. Journal of

Phenomenological

Psychology, 1970, 1, 75-98.

Giorgi, A., Fischer, W.F., & von Eckartsberg, R. Duquesne studies in phenomeno-

logical

psychology. Vol. I. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1971.

Giorgi, A. An application of phenomenological method. In A. Giorgi, C. Fischer,

& E. Murray

(Ed.),

Duquesne studies in phenomenological psychology. Vol. II.

Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1975.

Henry, J. Pathways to

Madness.

New York: Random House, 1965.

Husserl, E. Phenomenology and the crisis of philosophy. (Tr.) Q. Lauer, New

York: Harper and Row, 1965.

Hycner, R. The experience of wonder: a phenomenological exploration and its

implications for therapy. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, California School

of Professional Psychology-San Diego, 1976.

Keen, E. A primer in phenomenological psychology. New York: Holt, Reinhart

and Winston, Inc., 1975.

Maslow, A. Toward a psychology of being (2nd edition) New York: Van Nostrand

Reinhold Company, 1968.

Maslow, A. The psychology of science: A

reconnaissance.

Chicago: Henry Regnery

Company, 1966.

Merleau-Ponty, M. The phenomenology of perception. Trans. C. Smith. London:

Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. 1962.

Murray E. & Giorgi, A. (Ed.) Duquesne papers in phenomenological psychology.

Vol. I. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1974.

Polanyi, M. Personal knowledge: Towards a post-cutical philosophy. New York:

Harper and Row, 1958.

Polkinghome, D. Lecture on phenomenological psychology given at the Califomia

School of Professional Psychology-San Diego, 1978.

Price, D. & Barrel, J. An experiential approach with quantitative methods: a re-

search paradigm. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 1980, 20(3), 75-95.

Psathas, G. (Ed.) Phenomenological sociology: issues and applications. New York:

Wiley PubUcations, 1973.

Quantrano, A.J. Identity formation in the borderline personality: a phenomeno-

logical study. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Califomia school of Profes-

sional Psychology-San Diego, 1980.

Rogei^, C. On becoming

a

person. Boston & Houghton Mifflin Company, 1961.

Sardello, R.J. A reciprocal participation model of experimentation. In A. Giorgi,

303

W.F.

Fischer, & R. von

Eckantsbexg

(Ed.) Duquesne studies in phenomenologi-

cal

psychology. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University.

Smith, D. & Murray, E. (Ed.) Duquesne papers in phenomenological psychology.

Vol. II, Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1977.

Spiegelberg, H. The phenomenological movement. Vol. II. 2nd ed. Hague: Martinus

Nijhoff,

1971.

Stevick, E. An empirical investigation of the experience of anger. In A. Goirgi,

W. Fischer, & R. von Eckartsberg (Ed.) Duquesne studies in phenomenology

psychology Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1971.

Tesch, R. Phenomenological and transformative

research:

What they are and how

to do them. Santa Barbara: Fielding occasional papers, 1980.

Valle, R. & King, M. (Ed.) Existential-phenomenological

alternatives

for psycholo-

gy. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

Van den Berg, J.H. A different existence. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press,

1972.

Van Kaam, A. Existential foundations of psychology. Pittsburgh, Duquesne Uni-

versity Press, 1966.

Van Kaam, A. Phenomenal analysis: Exemplified by a study of the experience of

really feeling understood./owma/ of Individual Psychology, 1959, 15, 66—72.