Office of the Inspector G eneral

U.S. Department of Justice

The Impact of an Aging Inmate

Population on the Federal Bureau of

Prisons

Revised February 2016

Evaluation and I nspections D

ivision 1

5-05 May 2 015

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Introduction

In September 2013, the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) incarcerated

164,566 federal inmates in 119 BOP-managed institutions.

1

According to

BOP data, inmates age 50 and older were the fastest growing segment of its

inmate population, increasing 25 percent from 24,857 in fiscal year

(FY) 2009 to 30,962 in FY 2013.

2

By contrast, during the same period, the

population of inmates 49 and younger decreased approximately 1 percent,

including an even larger decrease of 16 percent in the youngest inmates (age

29 and younger).

3

Based on BOP cost data, we estimate that the BOP spent

approximately $881 million, or 19 percent of its total budget, to incarcerate

aging inmates in FY 2013.

4

The Office of the Inspector General (OIG)

conducted this review to assess the aging inmate population’s impact on the

BOP’s inmate management, including costs, health services, staffing,

housing, and programming. We also assessed the recidivism of inmates who

were age 50 and older at the time of their release.

Results in Brief

The OIG found that aging inmates are more costly to incarcerate than

their younger counterparts due to increased medical needs. We further

found that limited institution staff and inadequate staff training affect the

BOP’s ability to address the needs of aging inmates. The physical

infrastructure of BOP institutions also limits the availability of appropriate

housing for aging inmates. Further, the BOP does not provide programming

opportunities designed specifically to meet the needs of aging inmates. We

also determined that aging inmates engage in fewer misconduct incidents

while incarcerated and have a lower rate of re-arrest once released;

however, BOP policies limit the number of aging inmates who can be

considered for early release and, as a result, few are actually released early.

Aging inmates are more costly to incarcerate, primarily due to their

medical needs. We found that the BOP’s aging inmate population contributes

to increases in incarceration costs. Aging inmates on average cost 8 percent

1

For this review, we examined sentenced inmates incarcerated in BOP-managed

institutions only. We excluded approximately 29,000 inmates who are incarcerated in contract

institutions, as well as approximately 14,000 pre-trial inmates.

2

For the purposes of this review, we define inmates age 50 and older as “aging.” For

more information, see page 2.

3

The percentage decrease in the youngest inmates (age 29 and younger) was listed

incorrectly as 29 percent when this report originally was issued in May 2015. We discovered

the error and have revised the report to correct it.

4

For more information, see Appendix 1.

i

more per inmate to incarcerate than inmates age 49 and younger (younger

inmates). In FY 2013, the average aging inmate cost $24,538 to incarcerate,

whereas the average younger inmate cost $22,676. We found that this cost

differential is driven by increased medical needs, including the cost of

medication, for aging inmates. BOP institutions with the highest percentages

of aging inmates in their population spent five times more per inmate on

medical care ($10,114) than institutions with the lowest percentage of aging

inmates ($1,916). BOP institutions with the highest percentages of aging

inmates also spent 14 times more per inmate on medication ($684) than

institutions with the lowest percentage ($49).

BOP institutions lack appropriate staffing levels to address the needs of

an aging inmate population and provide limited training for this purpose.

Aging inmates often require assistance with activities of daily living, such as

dressing and moving around within the institution. However, institution staff

is not responsible for ensuring inmates can accomplish these activities. At

many institutions, healthy inmates work as companions to aging inmates;

but training and oversight of these inmate companions vary among

institutions. We further found that the increasing population of aging

inmates has resulted in a need for increased trips outside of institutions to

address their medical needs but that institutions lack Correctional Officers to

staff these trips and have limited medical staff within institutions. As a

result, aging inmates experience delays receiving medical care. For example,

using BOP data from one institution, we found that the average wait time for

inmates, including aging inmates, to be seen by an outside medical specialist

for cardiology, neurosurgery, pulmonology, and urology to be 114 days. In

addition, we found that while Social Workers are uniquely qualified to

address the release preparation needs of aging inmates, such as aftercare

planning and ensuring continuity of medical care, the BOP, which employs

over 39,000 people, has only 36 Social Workers nationwide for all of its

institutions. Institution staff told us they themselves did not receive enough

training to identify the signs of aging.

The physical infrastructure of BOP institutions cannot adequately

house aging inmates. Aging inmates often require lower bunks or

handicapped-accessible cells, but overcrowding throughout the BOP system

limits these types of living spaces. Aging inmates with limited mobility also

encounter difficulties navigating institutions without elevators and with

narrow sidewalks or uneven terrain. The BOP has not conducted a

nationwide review of the accessibility of its institutions since 1996.

The BOP does not provide programming opportunities specifically

addressing the needs of aging inmates. BOP programs, which often focus on

education and job skills, do not address the needs of aging inmates, many of

whom have already obtained an education or do not plan to seek further

employment after release. Though BOP institutions can and do design

programs, including release preparation programs, to meet the needs of their

ii

individual populations, even institutions with high percentages of aging

inmates rarely have programs specifically for aging inmates.

Aging inmates commit less misconduct while incarcerated and have a

lower rate of re-arrest once released. Aging inmates, comprising 19 percent

of the BOP’s inmate population in FY 2013, represented 10 percent of all the

inmate misconduct incidents in that year. Also, studies have concluded that

post-release arrests decrease as an individual ages, although BOP does not

maintain such data. The OIG conducted a sampling of data and found that

15 percent of aging inmates were re-arrested for a new crime within 3 years

of release. Based on our analysis, the rate of recidivism of aging inmates is

significantly lower than the 41 percent re-arrest rate that the BOP’s research

has found for all federal inmates. We further found that most of the aging

inmates who were re-arrested already had a documented history of

recidivism.

Aging inmates could be viable candidates for early release, resulting in

significant cost savings; but BOP policy strictly limits those who can be

considered and, as a result, few have been released. Over a year ago, the

Department concluded that aging inmates are generally less of a public

safety threat and the BOP announced an expanded compassionate release

policy to include them as part of the Attorney General’s “Smart on Crime”

initiative. However, the Department significantly limited the number of

inmates eligible for this expanded release policy by imposing several

eligibility requirements, including that inmates be at least age 65, and we

found that only two inmates had been released under this new provision.

According to institution staff, it is difficult for aging inmates to meet all of the

eligibility requirements of the BOP’s new provisions. Our analysis shows that

if the BOP reexamined these eligibility requirements its compassionate

release program could result in significant cost savings for the BOP, as well

as assist in managing the inmate population.

Recommendations

In this report, we make eight recommendations to improve the BOP’s

management of its aging inmate population. These recommendations

include enhancing BOP oversight and training of inmate companions,

studying the impact of the aging inmate population on infrastructure,

developing programs to address the needs of aging inmates during their

incarceration and as they prepare for release, and revising the requirements

that limit the availability of compassionate release for these inmates.

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

BACKGROUND ............................................................................................... 1

PURPOSE, SCOPE, AND METHODOLOGY............................................................ 9

RESULTS OF THE REVIEW ............................................................................. 10

Aging inmates are more costly to incarcerate, primarily due to their medical

needs..................................................................................................... 10

BOP institutions lack appropriate staffing levels to address the needs of an aging

inmate population and provide limited training for this purpose..................... 16

The physical infrastructure of BOP institutions cannot adequately house aging

inmates.................................................................................................. 23

The BOP does not provide programming opportunities specifically addressing the

needs of aging inmates ............................................................................ 30

Aging inmates commit less misconduct while incarcerated and have a lower rate

of re-arrest once released......................................................................... 37

Aging inmates could be viable candidates for early release, resulting in

significant cost savings; but new BOP policy strictly limits those who can be

considered and as a result, few have been released..................................... 41

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS......................................................... 51

APPENDIX 1: EXPANDED METHODOLOGY....................................................... 55

APPENDIX 2: THE BOP’S RESPONSE TO THE DRAFT REPORT ............................ 60

APPENDIX 3: OIG ANALYSIS OF THE BOP’S RESPONSE.................................... 63

BACKGROUND

Introduction

From fiscal year (FY) 2009 to FY 2013, the BOP experienced a shift in

the age demographic of its inmate population. During those 5 years, the

number of inmates age 50 and older in BOP-managed institutions was the

fastest growing segment of the BOP population, increasing by 25 percent,

from 24,857 to 30,962. During the same period, the population of inmates

49 and younger decreased approximately 1 percent, including an even larger

decrease of 16 percent in the youngest inmates age 29 and younger.

5

The OIG assessed the impact of an aging inmate population on the

BOP’s inmate management, including costs, health services, staffing,

housing, and programming, between FY 2009 and FY 2013. In this

background section, we define the BOP’s aging inmate population and discuss

the demographics and trends of this population. In addition, we outline the

new compassionate release provisions related to aging inmates. Finally, we

discuss the similar challenges faced by state correctional systems and the

different methods they use to address the growing aging inmate population.

Defining the BOP’s Aging Inmate Population

The BOP does not establish a specific age at which an inmate is

considered “aging.”

6

For the purposes of this report, we define inmates age

50 and older as aging.

7

Our definition is based on several factors including

studies, state programs and policies, as well as the opinions of BOP officials

and institution staff. In a 2004 report, the BOP’s National Institute of

Corrections (NIC) defined inmates age 50 and older as aging.

8

The NIC

further reported that seven state correctional agencies considered inmates

age 50 and older to be aging.

9

Several studies, including one published by

the American Journal of Public Health, state that an inmate’s physiological

5

The percentage decrease in the youngest inmates (age 29 and younger) was listed

incorrectly as 29 percent when this report originally was issued in May 2015. We discovered

the error and have revised the report to correct it.

6

When we asked BOP staff how they defined aging, their responses ranged from age

40 to age 78.

7

Throughout this report, we will use the term “aging inmates” to refer to inmates age

50 and older and the term “younger inmates” to refer to inmates age 49 and younger.

8

The NIC is an agency within the BOP. The NIC provides training, technical

assistance, information services, and policy and program development assistance to federal,

state, and local correctional agencies.

9

The NIC surveyed correctional systems in all 50 states, the District of Columbia,

U.S. territories, and Canada and found that seven states (Alaska, Florida, Idaho, New Mexico,

North Carolina, Ohio, and West Virginia) and Canada defined inmates as aging at age 50.

1

age averages 10–15 years older than his or her chronological age due to the

combination of stresses associated with incarceration and the conditions that

he or she may have been exposed to prior to incarceration.

10

During our

review, BOP officials and staff agreed that the combination of these factors

expedites the aging process. A Clinical Director told us that because most

aging inmates have preexisting conditions and are sicker than the general

population, they appear to be older than their actual age.

The BOP’s aging inmate population made up 19 percent of the BOP’s

overall population in FY 2013

Aging inmates made up 16 percent of the BOP’s total population in

FY 2009 and increased to 19 percent of the BOP’s total population in

FY 2013. Table 1 presents the total number of sentenced BOP inmates, the

number of younger inmates, and the number of aging inmates from FY 2009

through FY 2013.

11

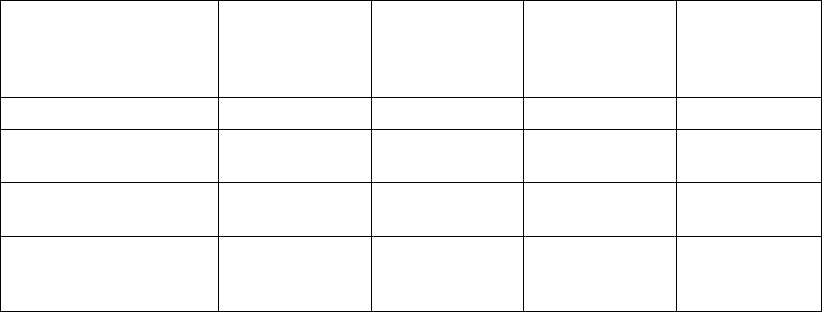

Table 1

Total Sentenced Inmate Population by Age

Fiscal Year

Sentenced

Inmates

Aging Inmates

(50 and older)

Younger Inmates

(49 and younger)

2009

159,189

24,857

134,332

2010 159,660 26,221 133,439

2011 165,797 28,239 137,558

2012 164,257 29,332 134,925

2013 164,566 30,962 133,604

Source: BOP population snapshots.

According to BOP data, not only are the numbers of aging inmates

increasing, they are generally increasing at a faster rate in older age groups.

Specifically, the number of inmates age 65 to 69 increased 41 percent;

inmates age 70 to 74 increased 51 percent; inmates age 75 to 79 increased

43 percent; and inmates age 80 and over increased 76 percent.

Nevertheless, inmates age 65 and older represented only 14 percent of the

aging inmate population in FY 2013, while inmates age 50 to 64 represented

86 percent of the 30,962 aging inmates. Figure 1 shows the increase in the

10

B. Williams, et al., “Aging in Correctional Custody: Setting a Policy Agenda for

Older Prisoner Health Care,” American Journal of Public Health 102, no. 8 (August 2012):

1475–1481, p. 3.

11

For this review, we examined sentenced inmates incarcerated in BOP-managed

institutions only. We excluded approximately 29,000 inmates who are incarcerated in contract

institutions, as well as approximately 14,000 pre-trial inmates.

2

number of aging inmates, distributed in 5-year increments, from FY 2009

through FY 2013.

Figure 1

Percent Change in Population of Aging Inmates from FY 2009 to

FY 2013

Percent Change

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

75-79 80+ 50-54 55-59 60-64 65-69 70-74

Age Cohorts

Source: BOP population snapshots.

Elimination of parole, use of mandatory minimum sentences, increases

in average sentence length over the past 3 decades, and an increase

in white collar offenders and sex offenders, among other things,

contribute to the aging inmate population

Research indicates that the growth in the aging inmate population can

be attributed to sentencing reforms beginning in the late 1980s, including the

elimination of federal parole and the introduction of mandatory minimums

and determinate sentences.

12

BOP staff and management officials agreed

that these sentencing reforms contributed to longer sentences, leading to an

increase in aging inmates. In addition to the increase in the aging inmate

population, there has also been a 9 percent increase in the number of

younger inmates who will be age 50 and older when they are ultimately

released.

13

(See Table 2 below.)

12

Nathan James, “The Federal Prison Population Buildup: Overview, Policy Changes,

Issues, and Options,” Congressional Research Service, April 15, 2014.

13

We based our analysis on each inmate’s release date as of the date we received

BOP data. We did not include younger inmates with life sentences, death sentences, or those

inmates who did not have release dates.

3

Table 2

Number of Younger Inmates Who Will Be Age 50 and Older at

Release

Fiscal Year

Number of Younger

Inmates

2009

19,385

2010

19,790

2011

20,488

2012

20,761

2013

21,221

Percent Change

9%

Source: BOP population snapshots.

The growth of the aging inmate population can also be attributed to

the increase in the number of aging offenders who are first-time white collar

or sex offenders.

14

From FY 2009 to FY 2013, the BOP experienced a

28 percent increase (7,944 to 10,153) in the number of first-time, aging

offenders. Further, the number of aging inmates incarcerated for fraud,

bribery, or extortion offenses increased by 43 percent and the number of

aging inmates incarcerated for sex offenses increased by 77 percent. White

collar offenders and sex offenders made up approximately 24 percent of the

aging inmate population in FY 2013. Conversely, these offenders made up

less than 10 percent of the younger inmate population.

Aging inmates make up a disproportionate share of the inmate

population in institutions providing higher levels of medical care

In 2002, the BOP implemented a system that assigned care levels to

inmates based on the inmate’s medical needs and to institutions based on

the resources available to provide care. Under this system, the BOP assigns

each inmate a care level from 1 to 4 based on documented medical history,

with Care Level 1 being the healthiest inmates and Care Level 4 being

inmates with the most significant medical conditions. The BOP also assigns

each institution a care level from 1 to 4, based on the institution’s level of

medical staffing and resources. Inmates are designated to an institution with

a corresponding care level.

15

(See Table 3 below.)

14

BOP data also indicated that 17,995 of the 30,962 (58 percent) aging inmates in

FY 2013 were sentenced at age 50 and older and 7,351 (41 percent) of those sentenced at 50

and older were first-time offenders.

15

For more information about the BOP’s care level system, see DOJ, OIG, The Federal

Bureau of Prisons’ Efforts to Manage Inmate Health Care.

4

Table 3

Description of the BOP’s Care Levels

Care Level

Description

1

Inmates who are younger than 70, with limited

medical needs requiring clinical contact no more than

once every 6 months

2

Inmates who are stable outpatients, with chronic

illnesses requiring clinical contact every 3 months

3

Inmates who are fragile outpatients, with conditions

requiring daily to monthly clinical contact

4

Inmates requiring inpatient care: Care Level 4

institutions are BOP medical centers.

Source: U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), OIG, The Federal Bureau of

Prisons’ Efforts to Manage Inmate Health Care, Audit Report 08-08

(February 2008).

According to BOP data, in FY 2013 aging inmates made up a

disproportionate share of the inmates housed in Care Level 3 and 4

institutions. Specifically, aging inmates made up 21 percent of the

population of Care Level 3 institutions and 33 percent of the population of

Care Level 4 institutions, compared to only 19 percent of the overall inmate

population.

16

Figure 2 illustrates the proportion of aging inmates assigned to

each care level.

Figure 2

Percentage of Aging Inmates Assigned to Each Care Level, FY 2013

100%

20%

40%

60%

80%

Percentage

0%

1 2 3 4

Care Level

Younger Inmates Aging Inmates

Source: BOP population snapshots.

16

Care Level 4 institutions also house cadre inmates who have work assignments and

are primarily made up of healthier, non–Care Level 4 inmates.

5

BOP Program Statement 5050.49 (Compassionate Release)

The increase of the aging inmate population adversely affects crowding

levels, particularly in minimum security, low security, and medical

institutions. At the end of FY 2013, the BOP as a whole was 34 percent over

capacity, with minimum security institutions at 19 percent over capacity, low

security institutions at 32 percent over capacity, and medical centers at

16 percent over capacity.

17

According to BOP data, aging inmates made up

26 percent of the population of minimum-security institutions, 23 percent of

the population of low-security institutions, and 33 percent of the population

of medical centers.

In the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984, Congress authorized the BOP

Director to request that a federal judge reduce an inmate’s sentence based

on “extraordinary and compelling” circumstances. Under the statute, the

request can be based on either medical or nonmedical conditions that could

not reasonably have been foreseen by the judge at the time of sentencing.

The BOP has issued regulations and a Program Statement entitled

“Compassionate Release” to implement this authority. In April 2013, the OIG

released a report that found significant problems with the management of

the BOP’s compassionate release program and that an effectively managed

program would help the BOP better manage its inmate population and result

in cost savings. We also found, in considering the impact of the

compassionate release program on public safety, a recidivism rate of

3.5 percent for inmates released through the program. By comparison, the

general recidivism rate for federal inmates has been estimated as high as

41 percent.

In August 2013, following the release of our review, the BOP

implemented new provisions to its Compassionate Release Program

Statement making inmates at least age 65 eligible for consideration for both

medical and nonmedical reasons.

18

One provision applies to inmates

sentenced for an offense that occurred on or after November 1, 1987, who

are age 70 years or older at the time of consideration for release and who

have served 30 years or more of their sentence of imprisonment. A second

provision applies to inmates:

17

Over-capacity level is based on our analysis of the BOP’s FY 2013 population

snapshot, combined with information about each institution’s security level as reported on the

BOP’s website. Our analysis excluded detention centers and contract institutions. The BOP’s

Long Range Capacity Plan, which includes all institutions, reports that at the end of FY 2013

the BOP as a whole was 36 percent overcrowded. At the end of FY 2014, the BOP reported

that its inmate population had dropped slightly from the year before. However, for this report

we examined population data only through FY 2013.

18

See BOP, Compassionate Release/Reduction in Sentence: Procedures for

Implementation of 18 U.S.C. § 3582(c)(1)(A) and 4205(g), Program Statement 5050.49

(August 12, 2013).

6

1. age 65 and older,

2. suffering from chronic or serious medical conditions related to the

aging process,

3. experiencing deteriorating mental or physical health that substantially

diminishes their ability to function in a correctional facility,

4. for whom conventional treatment promises no substantial

improvement to their mental or physical condition, and

5. who have served at least 50 percent of their sentence.

A third provision applies to inmates who are age 65 and older and

have served the greater of 10 years or 75 percent of their sentence. An

inmate’s medical condition is not evaluated under the first or third provisions.

To determine whether inmates applying under any of the three provisions are

suitable for compassionate release, the BOP further evaluates each inmate in

light of several factors, including but not limited to the nature and

circumstance of the inmate’s offense, criminal history, input from victims,

age at the time of offense and sentencing, release plans, and whether

release would minimize the severity of the offense.

States have begun addressing the challenges the of the aging inmate

population

State correctional systems are also facing an increase in aging inmate

populations. Specifically, according to a 2014 report, the number of inmates

age 55 and older in state and federal institutions increased 204 percent

between 1999 and 2012.

19

State correctional systems have also experienced

a substantial increase in healthcare costs. According to the report,

correctional healthcare spending rose in 41 states by a median of 13 percent

during the 5-year period from FY 2007 to FY 2011. The report indicates that

states generally incurred higher inmate healthcare spending where aging

inmates represented a larger proportion of the inmate population. For

example, the median healthcare spending per inmate in the 10 states with

the highest percentage of inmates age 55 and older averaged $7,142, while

the 10 states with the lowest percentage of these inmates averaged $5,196

per inmate. Later in this report, we provide a similar analysis based on BOP

institutions with the highest and lowest percentage of aging inmates.

To address the growth of aging inmate populations, at least 15 states

have provisions that would allow for the consideration of early release for

19

Pew Charitable Trusts and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation,

“State Prison Health Care Spending,” July 8, 2014, http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-

and-analysis/reports/2014/07/08/state-prison-health-care-spending (accessed April 9, 2015).

The report did not break out the increase between state and federal institutions.

7

aging inmates, but with varying eligibility requirements.

20

Some states

restrict eligibility to aging inmates with physically or mentally debilitating

conditions, while other states open eligibility to all aging inmates who meet

age and time served requirements. Outside of early release considerations,

several states have developed separate housing units or institutions for aging

inmates, including housing units dedicated to older inmates with chronic

health problems. For example, the Florida Department of Corrections has

several institutions with units designed specifically for aging inmates,

including one dedicated for inmates age 50 and older. States have also

recognized the need for different programming for aging inmates, including

one program in Nevada designed for inmates age 55 and older to enhance

their overall health through daily activities.

20

Tina Chiu, “It’s About Time: Aging Prisoners, Increasing Costs, and Geriatric

Release,” VERA Institute of Justice, April 2010.

8

PURPOSE, SCOPE, AND METHODOLOGY

Purpose

Our review examined the BOP’s aging inmate population by assessing

the population’s impact on incarceration costs, health services, staffing,

housing, and programming. We also determined the recidivism rate of aging

inmates released from BOP custody.

Scope and Methodology

Our review analyzed BOP inmate population and cost data, as well as

BOP policies and programs from FY 2009 through FY 2013. Our review

focused on federal offenders incarcerated in the 119 institutions operated by

the BOP during our scope years. We excluded inmates housed in private

correctional institutions, contract community corrections centers, and

contract state and local institutions from our analysis. We also excluded

inmates who were in pre-trial detention.

Our fieldwork, conducted from February 2014 through

September 2014, included interviews, data collection and analyses, and

document reviews. We interviewed BOP officials, including the Assistant

Directors responsible for eight Central Office divisions.

21

We conducted

13 site visits to BOP institutions, including 5 institutions through video

teleconferences and 8 institutions in person. For each site visit, we

interviewed institution officials and staff. For those institutions that we

visited in person, we also interviewed inmates, toured housing units, and

observed the physical landscapes. Our site visits encompassed

BOP institutions representing all security levels, including minimum-, low-,

medium-, and high-security institutions, as well as administrative security

institutions such as federal medical centers and detention centers. A detailed

description of the methodology of our review is in Appendix 1.

21

The BOP’s Central Office is located in Washington, D.C. We interviewed the

Assistant Directors of the Administration; Human Resource Management; Health Services;

Information, Policy, and Public Affairs; Reentry Services; Correctional Programs; and

Industries, Education and Vocational Training Divisions. We also interviewed the General

Counsel.

9

RESULTS OF THE REVIEW

Aging inmates are more costly to incarcerate, primarily due to their

medical needs

According to BOP officials and staff, an aging inmate population’s most

significant impact is on medical costs. From fiscal year (FY) 2009 to

FY 2013, the BOP’s spending on inmate healthcare increased by 29 percent,

according to BOP data. In FY 2009, the BOP spent $854 million of its

$5.5 billion budget (16 percent) to provide medical care for its inmate

population. By FY 2013, medical costs increased to $1.1 billion, representing

17 percent of the BOP’s $6.5 billion budget that year. While the BOP states

that it cannot determine the specific medical costs associated with individual

inmates, we found that aging inmates, as a group, are more expensive to

incarcerate than younger inmates, primarily due to their medical needs. We

also found that medical costs are increasing at a rate higher than the BOP’s

total budget, especially at institutions housing more aging inmates, and are

driven by medications and medical trips outside of institutions. Finally, we

found aging inmates are receiving more medical services, both within BOP

institutions and from outside healthcare providers.

Using BOP inmate population and cost data, we estimated costs per

inmate based on security level and the number of days incarcerated within a

fiscal year.

22

We found that an aging inmate, on average, costs 8 percent

more to incarcerate than a younger inmate. For example, in FY 2013, the

average aging inmate cost $24,538 to incarcerate, whereas the average

younger inmate cost $22,676. We also found that average cost per inmate

rises with age, with the 8,831 inmates age 18 to 24 costing an average of

$18,505 each and the 157 inmates age 80 and older costing an average of

$30,609 each. While the aging inmate population represents only 19 percent

of the BOP’s total population, the costs to incarcerate them are increasing at

a faster rate than for younger inmates. For example, the cost of

incarcerating aging inmates grew 23 percent, from $715 million in FY 2010 to

$881 million in FY 2013, while the cost of incarcerating younger inmates

grew 3 percent, from $3.5 billion to $3.6 billion over the same period. (See

Figure 3 below for the average annual cost per inmate in FY 2013.)

22

The BOP determines the average cost to incarcerate inmates by the type of

institution where an inmate is housed, such as a low-security institution or a federal medical

center, not by the specific cost to incarcerate each inmate. Therefore, we calculated the

number of days served by each inmate in each fiscal year and applied the cost of the type of

institution where that inmate was housed. See Appendix 1 for more details on our analysis.

10

Figure 3

Av

erage Annual Cost per Inmate by Age, FY 2013

Average Cost

$35,000

$30,000

$25,000

$20,000

$15,000

$10,000

$5,000

$0

Age

Source: BOP population and daily cost data.

According to the BOP’s Assistant Director for Health Services and

Medical Director, inmates in their fifties and sixties place the greatest burden

on the BOP because their numbers are increasing and many of them have

significant health problems stemming from years of substance abuse.

Similarly, BOP officials and staff at each institution we visited said the most

significant impact of aging inmates on the BOP is the cost associated with

addressing their increased medical needs. For example, a Health Services

Administrator of an institution where aging inmates were 27 percent of the

population told us that her institution’s medical budget increased from

$3 million to $9 million in FY 2012 alone due to the aging inmate population.

Aging inmates we interviewed also acknowledged their impact on the BOP’s

medical costs. One aging inmate told us that he has had two heart attacks,

two strokes, open-heart surgery, cancer, and has diabetes. He told us that it

must cost the BOP “a fortune” to keep him incarcerated. We discuss the

impact aging inmates have on BOP institutions’ medical costs, as well as

factors that drive increased medical costs for aging inmates, below.

11

Healthcare spending per inmate is greater at institutions with the highest

percentage of aging inmates

Using BOP population and medical cost data, we calculated medical

spending per inmate within each institution and found that the BOP’s

healthcare spending coincides with the percentage of aging inmates at an

institution.

23

Specifically, we found that the five institutions with the highest

percentage of aging inmates spend significantly more per inmate on medical

costs than the five institutions with the lowest percentage of aging inmates

(see Table 4).

24

Table 4

Medical Spending per Inmate at Institutions with the Five Highest

and Lowest Percentages of Aging Inmates

FY 2009

Percentage

of Aging

Inmates

Cost Per

Inmate

FY 2013

Percentage

of Aging

Inmates

Cost Per

Inmate

Highest

27%

$6,528

Highest

31%

$10,114

Lowest

5%

$2,110

Lowest

7%

$1,916

Source: BOP medical spending data.

As Table 4 shows, in FY 2009, institutions with the highest percentage

of aging inmates spent on average $6,528 per inmate on medical costs while

institutions with the lowest percentage of aging inmates averaged $2,110 per

inmate. The same pattern of spending emerged in FY 2013, when

institutions with the highest percentage of aging inmates spent on average

$10,114 per inmate while institutions with the lowest percentage of aging

inmates spent $1,916 per inmate.

23

According to the BOP, there is no direct way to associate medical care provided

with the costs incurred for each inmate because its electronic medical records system and

financial management system are not connected. The BOP’s Assistant Director for

Administration told us that the BOP does not track costs by inmate because its accounting

system tracks spending by program area only.

24

We excluded BOP medical centers, detention centers, and correctional complexes

from this analysis. We excluded correctional complexes because spending data is reported in

the aggregate instead of separately for each institution within the complex. For example, one

correctional complex spent $99 million on medical care in FY 2013 but we could not determine

how much was specifically spent by a medical center and each of three other institutions

within the complex. Because we excluded these institution types, our cost estimates of

spending per inmate are lower. See Appendix 1 for additional details.

12

Institutions with the highest percentage of aging inmates spend more per

inmate on medical care provided both inside and outside BOP institutions

All BOP institutions operate ambulatory clinics that incur medical

expenses for inmate care provided inside the institution. If an inmate has a

medical condition that becomes emergent, escalates, or requires further

examination or diagnosis from a specialist, the inmate may be transported

outside the institution for services. We found that medical costs incurred for

care provided both inside and outside institutions account for 86 percent of

the BOP’s medical costs each year.

25

According to the BOP, costs for medical

services provided inside all BOP institutions increased 19 percent, from

$413 million in FY 2009 to $493 million in FY 2013. Costs for medical

services provided outside BOP institutions (often in private or public

hospitals) increased even more sharply, rising 31 percent, from $320 million

in FY 2009 to $420 million in FY 2013.

We also found that costs for medical services provided both inside and

outside institutions increased at a higher rate at institutions with the highest

percentage of aging inmates when compared to institutions with the lowest

percentage of aging inmates. For example, in FY 2009, institutions with the

highest percentage of aging inmates spent about four times as much on

medical care provided outside of institutions than those with the lowest

percentage of aging inmates. By FY 2013, the gap widened even more

significantly, with institutions with the highest percentage of aging inmates

spending on average over 10 times more on outside medical care than

institutions with the lowest percentage of aging inmates. (See Table 5

below.)

Table 5

Average Cost Per Inmate for Medical Services Provided Inside and

Outside Institutions with the Highest and Lowest Percentages of

Aging Inmates

FY

2009

Percentage

of Aging

Inmates

Inside

Services

Outside

Services

FY

2013

Percentage

of Aging

Inmates

Inside

Services

Outside

Services

Highest 27% $2,551 $2,826 Highest 31% $3,436 $5,751

Lowest

5%

$1,244

$658

Lowest

7%

$1,224

$563

Source: BOP medical spending data.

25

Medical costs also include salaries for U.S. Public Health Service employees, who

staff many institution medical clinics; medical transport costs; and costs of handling

unforeseen medical events at institutions. These costs, when combined with inside and

outside medical services, total the BOP’s medical budget. See Appendix 1 for additional

details.

13

Institution staff also

told us that aging inmates

incur more medical costs

due to increased visits to

medical clinics inside the

institution and medical trips

outside the institution. For

example, a Warden told us

that aging inmates are more

likely to be chronic care

patients seen more

frequently by healthcare

services.

26

Aging inmates

also told us they are

receiving more medical

services. For example, a

different aging inmate from

the one referenced above

told us he gets two shots

per day, requires dialysis,

and has a number of ailments including congestive heart failure, diabetes,

sleep apnea, cataracts, and Hepatitis C. In addition to medical care provided

inside the institution to treat his medical conditions, every 6 months he

receives outside medical care for his heart. Below, we discuss two specific

factors that we found drive increased medical costs associated with an aging

inmate population: medication costs and staff overtime to meet inmate

medical needs.

Budgetary Impact of Hepatitis C Treatment

According to the BOP, as medication costs continue

to increase, they will place even greater pressure on

the BOP’s budget in the future. For example,

institution staff told us about treatments recently

approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

regarding Hepatitis C, a condition that is particularly

prevalent among aging inmates. Approximately

12,000 inmates have Hepatitis C, and 47 percent of

those are aging inmates. Medical staff at a BOP

medical center told us that while they did not yet

know the cost of the new Hepatitis C medication at

the time of our interview, they anticipated costs to be

“astronomical” because Hepatitis C is one of the most

common infectious diseases in the inmate population.

The BOP reports that former treatments cost $6,600

per patient, while the treatment recently approved by

the FDA will cost an additional $20,000 to $40,000

per patient.

Source: BOP FY 2015 congressional budget

justification.

14

Me

dications and staff overtime to meet inmate medical needs are significant

drivers of increasing medical costs

Due to their medical needs and chronic health problems, aging

inmates require more medications and are substantially driving up the BOP’s

medical costs. We found that the BOP’s spending on medications increased

32 percent, from $62 million in FY 2009 to $82 million in FY 2013. We also

found that the BOP’s spending on medications was higher, and increased

faster, at institutions with the highest percentage of aging inmates. The

BOP’s Assistant Director for Health Services and Medical Director told us that

medication for inmates requiring chronic care is one of the BOP’s major

healthcare cost drivers. A Warden also said that a high percentage of aging

inmates are being treated for chronic medical conditions and that

medications drive the costs to care for these inmates. By contrast,

medication costs were lower and increased more slowly at institutions with

26

The BOP schedules inmates with ongoing medical problems for frequent

appointments with BOP medical staff to reassess their status and renew their prescriptions.

the lowest percentage of aging inmates. For example, in FY 2013 institutions

with the highest percentage of aging inmates spent an average of $684 per

inmate on medications, or about 14 times more than those with the lowest

percentage of aging inmates, which spent an average of $49 per inmate on

medications in FY 2013.

Institution staff also told us that aging inmates with chronic conditions

require treatment from specialists outside the institution and that overtime

paid to Correctional Officers who escort inmates to such appointments is a

significant budget item. According to BOP data, in FY 2013, in addition to

paying for outside medical care, the BOP spent $53 million in overtime to

transport inmates to outside medical care, a 17 percent increase from the

$46 million spent in FY 2009. As one example, an Associate Warden said

overtime costs associated with transporting aging inmates to outside medical

appointments and hospitalizations were “phenomenal” and that his institution

was over its allotted overtime budget less than half way through the fiscal

year for this reason.

Aging inmates disproportionately require catastrophic medical care

In May 2012, the BOP Assistant Director for Health Services and

Medical Director issued to all institutions a memorandum on “Catastrophic

Case Management”; it defined catastrophic medical cases as those where the

estimated or actual cost of outside medical care for an inmate housed in a

nonmedical BOP institution exceeds $35,000 for a single medical event and

provided guidance on how to track and monitor these cases.

27

We analyzed

catastrophic care data from one BOP region between FY 2009 and FY 2013

and found that while only 18 percent of the inmates in this region were aging

inmates during this period, 59 percent of the catastrophic medical cases

involved aging inmates (see Table 6). Moreover, because the aging inmate

population in this region was about four times smaller than the younger

inmate population, the probability of an aging inmate having a catastrophic

medical issue was about eight times higher than for a younger inmate.

27

As of FY 2012, all BOP regions adopted a catastrophic case management system

designed to track and monitor cases and to measure the fiscal and clinical outcomes of care.

While beyond the scope of this review, we learned that the BOP’s six regions do not

consistently track catastrophic medical cases and that the BOP’s Central Office does not

process or analyze that data to better understand the impact of catastrophic healthcare events

on budget and decision-making. Due to the inconsistency of regional tracking, we were able

to analyze catastrophic case spending in only one region. See Appendix 1 for details.

15

Table 6

Catastrophic Cases in One BOP Region, FY 2009 to FY 2013

Age

FY

2009

FY

2010

FY

2011

FY

2012

FY

2013

Total

Cases Involving Younger

Inmates

53 58 70 60 79 320

Cases Involving Aging

Inmates

58 76 104 104 126 468

Total 111 134 174 164 205 788

Percent of Aging Inmates

in this Region

16% 17% 18% 18% 19% 18%

Percent of Catastrophic

Cases Involving Aging

Inmates

51% 57% 60% 63% 61% 59%

Source: BOP catastrophic case data.

We also found that during this time, this region spent $71 million on

catastrophic medical care, 60 percent ($45 million) of which was spent on

aging inmates. Based on our review of available data, we found that aging

inmates received catastrophic medical services for a variety of medical

conditions, particularly heart and lung conditions. Services from this region

included treatment of clogged arteries, heart failure, cardiovascular issues,

respiratory failure, lung disease, and cellulitis. Finally, while the costs

associated with catastrophic care cases must all exceed at least $35,000, we

found cases with significantly more costs. For example, the most expensive

case from this region involved over $850,000 spent for an aging inmate who

was treated for complicated coronary artery disease.

In addition, we found that the increase in catastrophic medical cases in

this region was not limited to Care Level 3 institutions, which, as described

above, are specifically intended to care for outpatient inmates with medical

conditions that require daily to monthly outpatient clinical contact. For

example, a Care Level 2 institution, which incarcerates inmates who are

stable outpatients and typically require clinical contact only every 3 months,

accounted for 30 percent of the region’s catastrophic medical cases in

FY 2013. Aging inmates comprised 62 percent of this institution’s

catastrophic medical cases, even though they represented only 27 percent of

its population.

BOP institutions lack appropriate staffing levels to address the needs

of an aging inmate population and provide limited training for this

purpose

As described above, the increasing aging inmate population has

resulted in an increase in trips outside of institutions to address their medical

needs. We found that institutions lack Correctional Officers to staff these

trips and have limited medical staff within institutions to address aging

16

inmates’ medical needs. As a result, aging inmates experience delays in

receiving medical care. In addition, the needs of aging inmates differ from

their younger counterparts, including the need for increased assistance with

activities of daily living. According to BOP staff, however, staff is not

responsible for ensuring inmates can accomplish these activities. We found

that, instead, institutions rely on local inmate companion programs in which

healthy inmates provide assistance for aging or disabled inmates. Further,

aging inmates, specifically those with unique medical needs, also require

advanced release preparation. We found that Social Workers are uniquely

qualified and trained to address these needs, yet few institutions have them.

Finally, we found that institution staff has limited training to identify signs of

aging in inmate conduct, which can be mistakenly viewed as reflecting

disciplinary issues rather than signs that the inmate needs medical or mental

health care.

Understaffed health services units limit access to medical care and contribute

to delays for aging inmates

Aging inmates have an increased need for health services; but,

according to BOP officials, staff, and inmates, institutions lack adequate

health services staff to address these needs.

28

For example, the Clinical

Director of a medical center told us that only 80 percent of that institution’s

health services positions are staffed and that the vacancies limit the number

of inmates, including aging inmates, the institution can treat.

29

A Case

Manager at a nonmedical institution told us that the institution was “over a

thousand inmates behind” in servicing those enrolled in chronic care clinics.

An aging inmate told us that the health services staff at his institution is

“inundated” with requests for care and that, while they work hard, they can

only do so much. Aging inmates at numerous institutions also told us that

limited health services staff sometimes resulted in long waiting periods for

care.

30

For example, an aging inmate told us that he requested dentures in

28

BOP officials told us that hiring health service staff is difficult. According to the

Assistant Director for Human Resources, it is difficult to hire medical staff in urban areas

because the BOP cannot offer doctors and nurses salaries and benefits that are comparable to

those offered by private employers. Although the salaries and benefits are more competitive

in rural areas, the BOP is challenged with finding medical staff willing to live in remote areas.

The BOP uses some incentives such as periodically increasing employee pay, paying relocation

expenses, and offering to a pay a portion of student loans. Nevertheless, as of August 2014,

only 84 percent of the BOP’s medical doctor positions were filled, which is below the BOP’s

goal of 90 percent.

29

This medical center had two physician vacancies, two mid-level practitioner

vacancies, and several nurse vacancies open at the time of our fieldwork.

30

The BOP’s Assistant Director for Health Services and Medical Director told us that in

November 2014 the BOP launched a survey of inmates in all BOP institutions to assess

inmates’ access to healthcare. He told us that once the survey is complete, the Health

Services Division will analyze the results by institution. For institutions where inmates report

delays in receiving care, the BOP will try to determine the underlying causes of delay at each

institution in order to develop potential responses.

17

2010 and had yet to receive them.

31

He said this makes it extremely hard to

eat because he cannot chew food.

Additionally, the lack of an adequate number of health services staff

increases the need for outside care. A Case Manager told us that the lack of

health services staff at his institution has led to more emergency trips to

hospitals outside the institution because the institution does not have a

Physician Assistant to address medical needs. We also found that trips to

outside medical providers are often limited by the availability of Correctional

Officers to escort inmates. According to BOP policy, correctional staff is

required to escort inmates to outside medical appointments.

32

The limited

availability of Correctional Officers restricts aging inmates’ access to medical

care outside the institutions, and institution staff told us that, as a result,

there are waitlists to send inmates to outside medical specialists.

Using BOP data from one institution, we found that the average wait

time for inmates, including aging inmates, to be seen by an outside medical

specialist for cardiology, neurosurgery, pulmonology, and urology to be

114 days. The wait time at this institution increased to 256 days for those

inmates waiting to see outside specialists for additional or routine

appointments.

33

The Assistant Health Services Administrator at this

institution told us that there was no doctor at the institution and, while staff

used to be able to send inmates on 10 medical trips per day, the institution

now has the staff to provide only 6 planned trips and 2 emergency trips per

day. We found similar difficulties staffing outside medical trips at other

institutions. The Associate Warden at one institution told us his staff can

accommodate 6 trips to outside medical specialists per day, even though the

inmate population requires 8 to 10 trips per day. We also noted that outside

medical trips depend on appointment availability and that, while an

institution may be able to provide the necessary number of medical trips per

week, specialists in the community must also be available and willing to see

an inmate.

We additionally found that the management of outside medical care

waitlists affects the medical care provided to aging inmates. Specifically, we

were provided examples of inmate appointments not being rescheduled when

canceled, being rescheduled when the appointment had already taken place,

31

Inmates with dental problems, such as abscesses, that could cause harm if left

untreated, receive priority for dental appointments. The BOP’s Assistant Director for Health

Services and Medical Director told us that the BOP has also initiated a National Dental Waiting

List so that inmates awaiting dental care do not fall back to the end of the list if they are

transferred to a different institution.

32

BOP, Escorted Trips, Program Statement 5538.06 (August 29, 2014).

33

Only one institution tracked waitlist times, and we requested this data from the

BOP. Based on the data available to us, we could not determine how much of the delay in

receiving outside medical care is due to limited staffing and how much is due to limited

availability of appointments with specialists.

18

or not being scheduled at all. A Health Services Administrator told us that

inmates who are on waitlists for outside medical care can “fall through the

cracks” if their appointments are canceled and not rescheduled. An aging

inmate told us that he was sent outside the institution for a medical

appointment and 2 months later was rescheduled for the same medical need.

When he brought the issue to the Clinical Director, he was told that it was

just an appointment reminder. However, the inmate told us that he believes

staff did not realize he had already been seen. Another aging inmate told us

that at the time of our interview he had been waiting 2 years to be taken

outside his institution for an examination to receive eyeglasses and had

resorted to using a magnifying glass in the meantime.

The availability and purpose of inmate companion programs used to help

aging inmates accomplish their activities of daily living vary by institution

All inmates are expected to perform activities of daily living, including

dressing, cleaning their cells, and moving around within the institution.

However, staff told us that aging inmates often cannot perform these

activities on their own because of their medical conditions and staff is not

responsible for ensuring inmates can accomplish these activities. Some

institutions we visited have established local inmate companion programs to

address the increasing number of aging inmates who need assistance with

these activities. These programs utilize healthier inmates to provide support

to inmates, including aging inmates, who experience difficulty functioning in

a correctional environment.

Institution staff we interviewed found their local inmate companion

programs beneficial to both aging inmates and staff. For example, a Health

Services Administrator described to us an aging inmate with dementia and

Alzheimer’s disease who needed increased resources and attention. In this

case, an inmate companion served as staff’s “eyes and ears,” alerting them

to changes in the inmate’s behavior. A Counselor told us he does not know

how he would manage the unit without the assistance of inmate companions.

However, not all institutions have inmate companion programs. At one

institution without an inmate companion program, an Assistant Health

Services Administrator told us that aging inmates typically pair with a friend

or cellmate for assistance. A Health Services Administrator at another

institution said that inmates who cannot perform their activities of daily living

and require daily or weekly assistance beyond what the inmate companions

there are trained to provide are referred for transfer to an institution that can

meet their needs.

34

34

Inmates needing a medical transfer had been waiting for an average of 1–2 months

in October 2014. We further discuss issues regarding transfers for medical reasons below.

19

Also, the implementation of inmate companion programs varies by

institution, particularly between nonmedical institutions and medical centers.

For example, medical centers had local policies and position descriptions

establishing expectations for inmate companions. Inmate companions at one

medical center are expected to work in contact with bodily fluids and to help

care for inmates suffering from chronic and acute diseases. They also

provide assistance with moving inmates within an institution, feeding,

answering patient call lights, and changing diapers. However, at nonmedical

institutions, including those with high percentages of aging inmates, inmate

companion programs have no policies or job descriptions. Instead, inmate

companions are often referred to as “wheelchair pushers” because their

primary responsibility is to help inmates confined to a wheelchair travel

within an institution. Staff at two institutions we visited said they use inmate

companions only as part of their institution’s suicide prevention programs.

An Associate Warden told us that each of the eight institutions where he has

worked implemented its local inmate companion program differently. We

found other differences between how institutions implement inmate

companion programs, including:

• Training: At some institutions we visited, inmate companions are

provided training on medical safety standards, confidentiality, listening

skills, and job expectations. However, training at other institutions is

less extensive. For example, at one institution where inmate

companions are utilized as wheelchair pushers, inmate companions

complete 1 day of training on wheelchair ergonomics and safety

precautions. At another institution, there is no formal training for

wheelchair pushers.

• Selection: Each institution we visited that had an inmate companion

program selected inmates who were considered responsible and had

few misconduct incidents. Institutions with more robust programs also

require inmate companions to meet specific selection criteria, such as

having passed a General Education Development (GED) test.

• Compensation: At institutions we visited, inmate companion pay

varied based on companions’ levels of responsibility. For example, a

Counselor at an institution where inmate companions have more

responsibility told us that most companions are paid $40 a month. A

Case Manager at an institution where inmates have less responsibility

told us that companions are paid $5 to $7 a month.

• Oversight: One institution with a local inmate companion policy

developed a committee of nursing staff and selected inmate

companion representatives to oversee the program. The committee

reviews inmate companion assignments, develops plans of care, and

identifies training needs. At another institution, where the program

20

does not operate out of the health services or nursing departments,

unit teams informally manage the inmate companions.

35

According to institution staff and inmates, despite the benefits of and

need for inmate companion programs, aging inmates face risks when these

programs are inconsistently implemented. An aging inmate told us that most

inmate companions really try to help, but sometimes companions take

advantage of aging inmates. For example, a Supervisor of Education told us

about an inmate who had an inmate companion who was threatening the

inmate’s wife and forcing her to send money in return for the inmate’s

protection. The inmate told the Supervisor that it had been going on for a

long time but that he had been unable to tell institution staff because the

companion accompanied him everywhere, including to personal meetings

with staff. Institution officials and staff said that the inmate companion

program should be a standardized national program, with a program

statement establishing policies that hold inmate companions accountable for

their responsibilities. At one institution with program guidelines, inmate

companions are expected to sign the guidelines, acknowledging they will

abide by program rules. If a companion violates any of the guidelines, the

inmate companion committee conducts a misconduct review. Without the

protections or oversight of national guidelines, however, each institution can

run the program inconsistently.

Social Workers are uniquely qualified and trained to address the needs of

aging inmates, particularly with release planning, but few institutions have

Social Workers

We found that Social Workers are a great benefit for aging inmates.

While Case Managers, Counselors, Social Workers, and other institution staff

work in concert to prepare inmates for release, only Social Workers have

extensive training in addressing the unique needs of aging inmates. Licensed

Social Workers can proficiently help with aftercare planning, resource

brokering, and medical continuity of care during reentry. A Social Worker

told us that they help aging inmates with accessing medical services and

equipment in the community upon release.

However, relatively few institutions have Social Workers. Specifically,

as of November 2014, there were only 36 Social Workers throughout all of

the BOP’s institutions. A Social Worker told us that at her institution there

are approximately 1,000 inmates for every Social Worker. Another Social

Worker told us that because there are so few Social Workers, he has to

prioritize the inmates he helps based on their more difficult problems and

35

The unit teams consist of a Unit Manager, Case Managers, Correctional Counselors,

Unit Secretaries, Correctional Officers, an Education Advisor, and a Psychologist who work with

all inmates assigned to live in a particular housing unit. The unit team directly observes an

inmate’s behavior and can make recommendations in programming areas.

21

greater reentry needs, limiting his ability to assist all inmates, including

aging inmates.

36

Although the BOP employs six Regional Social Workers to

assist institutions that do not have a Social Worker, they are limited in

availability because each of them is responsible for between 15 and

17 institutions. We reviewed the BOP’s Community Release Planning

Guidelines for Social Work and found that it did not define any duties for

regional Social Workers that were distinct from the duties for institution

Social Workers. BOP institution staff told us that regional Social Workers

provide resources so that institution staff can work with individual inmates.

We also found that the lack of availability of Social Workers within BOP

institutions hinders the BOP’s ability to effectively prepare aging inmates to

reenter society because other BOP staff do not have the training unique to

Social Workers. A Case Manager at an institution with Social Workers told us

that she relies on Social Workers because they know things she does not,

such as the “ins and outs” of applying for Social Security benefits. A Case

Management Coordinator at an institution without Social Workers said that

he has to try to find resources on the internet to assist aging inmates in

applying for Social Security. Staff at institutions without a Social Worker also

told us about the benefits a Social Worker would bring to their institution,

including addressing issues related to halfway house placement, explaining

eligibility for benefits to many uninformed or confused aging inmates before

they are released, and removing some of the burdens placed on Case

Managers.

Recognizing the benefit that Social Workers play in helping inmates

prepare for release, the BOP recently approved and budgeted for the hiring

of seven additional Social Workers to be assigned to 5 correctional

complexes, 1 medical center, and 1 female institution.

Institution staff is not adequately trained to identify the signs of aging, which

mistakenly can be viewed as reflecting disciplinary issues rather than a need

for medical or mental healthcare

The BOP provides brief, limited training for institution staff on

recognizing the signs of aging in its Annual Refresher Training, which states

that the significant increase in aging inmates requires staff to contend with

increased mobility issues, terminal illness, and cognitive impairments. The

training includes ways staff can be aware of changes in aging inmates and

provide increased monitoring to help with inmates’ cognitive and physical

deterioration. The training further elaborates on aging inmates’

36

In October 2014, the BOP released Community Release Planning Guidelines for

Social Work (Guidelines) to assist inmates in identifying necessary community resources for

release planning. While these Guidelines identify Social Workers as a resource for inmate

release planning, Social Workers are currently available only at Care level 3 and 4 institutions,

making their availability to Care level 1 and 2 inmates limited.

22

vulnerabilities, such as being forgetful, losing track of time, taking longer to

complete tasks, not being able to follow directives, and having increased

physical stress. The training also informs participants that aging inmates will

require time and understanding to acclimate to an institutional environment.

However, the Annual Refresher Training Instructor Guide states that training

on signs of aging as well as medical emergencies can be completed in

30 minutes.

The Assistant Director for Human Resources told us that the BOP

currently trains all staff to meet the local needs of its population and that, as

a result, staff at Care Level 3 and 4 institutions should be able to recognize

mobility issues and make necessary accommodations. However, we found

that inmates in Care Level 2 institutions also have mobility issues that would

require staff to recognize and accommodate those and other health issues in

aging inmates. For example, an anemic, wheelchair-bound aging inmate at a

Care Level 2 institution told us that he was disciplined several times for

pushing himself inside a building to wait for his medication rather than

waiting outside, including in cold weather, to receive it.

In March 2010, the BOP’s National Institute of Corrections (NIC)

released a training video on aging inmates, aimed at officials running state

and local institutions, which said that the most critical step institutions could

take to address an aging inmate population is staff training. According to the

video, training is important to help staff understand that aging inmates may

have a medical reason that explains behavior that would otherwise be

subject to discipline, such as an aging inmate who is in the wrong place

because he has dementia. Institution staff with whom we spoke agreed that

this type of training at the BOP would be helpful and provided us examples.

A Case Manager described to us how she once asked an inmate several

questions and received strange responses. She said she thought the inmate

was trying to “fool her,” but she later learned that the inmate had medical

conditions that prevented him from responding. She said training on how to

recognize behaviors resulting from dementia or other debilitating conditions

would be helpful. A Social Worker also said staff should be trained to

understand the behaviors associated with dementia. The Assistant Director

for the Health Services Division and Medical Director said that the BOP has

started to put more into annual training regarding officer sensitivity but that

the BOP should permanently incorporate training specifically for the care of

aging inmates across the institutions.

The physical infrastructure of BOP institutions cannot adequately

house aging inmates

The BOP’s mission includes confining federal offenders in controlled

environments that are safe, humane, cost-efficient, and appropriately secure.

However, the BOP’s ability to confine its aging inmate population is

insufficient due to overcrowding in its institutions, as well as problems with

23

their internal and external infrastructures. Lower bunks, essential for

accommodating aging inmates with mobility limitations or medical conditions,

is limited by the overcrowding of BOP institutions. As a result, institutions do

not always have enough lower bunks as well as handicapped-accessible cells

and bathrooms, and others cannot accommodate the number of inmates with

mobility devices that require elevators. Further, aging inmates cannot

consistently navigate the narrow sidewalks and uneven terrain at some

institutions. Staff and inmates told us that separate housing units, or entire

institutions, would be more appropriate to house aging inmates.

Lower bunks are limited due to the overcrowding of BOP institutions

According to BOP staff and officials, aging inmates generally require

lower bunks because of their physical limitations and risk of falling.

However, BOP institutions are consistently overcrowded, limiting the number

of available lower bunks.

37

Several officials and staff told us that their

institution has run out of lower bunks for aging inmates. We found that the

lack of sufficient lower bunks affects aging inmates in several ways.

First, the lack of lower bunks may prevent or delay aging inmates from

receiving lower bunks. Consequently, aging inmates may be housed in upper

bunks until a lower bunk becomes available. For example, a Warden told us

that aging inmates are sometimes assigned to an upper bunk out of

necessity, which could be a problem for aging inmates because climbing into

an upper bunk is not always easy. During our visits to BOP institutions, we

observed upper bunks that did not have ladders or steps, which required

inmates to climb on desks, chairs, or makeshift pedestals to access the upper

bunks.

Second, the lack of lower bunks has forced institutions to retrofit other

space to create additional lower bunks. A Supervisor of Education told us

that her institution was unable to accommodate all of the inmates who

needed lower bunks. As a result, the institution had to add beds to a room

not originally intended for housing. We also found that institutions modified

or added lower bunks within existing housing cells to accommodate aging

inmates and inmates with mobility limitations, including retrofitting two-man

cells or “cubes” to hold three inmates. A Case Manager told us that while

many three-man cells are composed of one double bunk and one single

bunk, her institution created some triple-level bunk beds in which both the

middle and bottom bunks are considered “lower bunks.” She also told us she

observed inmates with histories of seizures and high blood pressure receiving

middle bunks, which she said could create a liability for the BOP if the

inmates were to fall.

37

In FY 2013, the BOP as a whole operated at 36 percent over capacity and aging

inmates represented the fastest growing segment of the BOP’s population.

24

Finally, the lack of lower bunks requires staff to regularly reassign

lower bunks by prioritizing and reorganizing bed assignments, which

sometimes creates tension among the inmates being moved. Specifically,

institution staff told us that managing lower bunks can be a very difficult,

time-consuming endeavor and that it often takes a collaborative effort

between inmates and staff from other units to accommodate aging inmates.

A Counselor told us that trying to find a lower bunk is comparable to “finding

a needle in a haystack.” Moreover, accommodating aging inmates with lower

bunks has repercussions. Staff from institutions across all security levels

described to us situations in which moving a younger inmate to an upper

bunk to accommodate an aging inmate created tension or animosity within

the housing unit. In one case, a Counselor told us that the tension from

assigning a younger inmate from a lower to an upper bunk led to an assault.

To help manage lower bunks, institution medical staff issues lower

bunk passes to those inmates who meet criteria in a memorandum issued in