X

Wages and working

conditions in the coffee

sector: the case of

Costa Rica, Ethiopia,

India, Indonesia and

Viet Nam

Background note

by Luis Pinedo Caro

Wages and working conditions in the

coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica,

Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

by Luis Pinedo Caro

Copyright © International Labour Organization 2020

First published year 2020

Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright

Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that

the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publishing

(Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: rights@ilo.org.

The International Labour Office welcomes such applications.

Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in

accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights

organization in your country.

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

Geneva: International Labour Office, December 2020

ISBN 978-92-2-033986-2 (web PDF)

The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the pre-

sentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International

Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the

delimitation of its frontiers.

The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rests solely with their

authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Office of the opinions

expressed in them.

Reference to names of firms and commercial products and processes does not imply their endorsement by the

International Labour Office, and any failure to mention a particular firm, commercial product or process is not a

sign of disapproval.

Information on ILO publications and digital products can be found at: www.ilo.org/publns.

Picture on cover © Panos Pictures (UK)

Printed in Switzerland

Contents

Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................................v

Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................ vii

1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................................1

2. Database description ..................................................................................................................................................2

3. Working conditions in the coffee sector ................................................................................................................4

3.1 Employment levels in the coffee sector ..............................................................................................................4

3.2 Socio-demographics of coffee workers .............................................................................................................. 7

3.3 Structure of the workforce in the coffee sector ................................................................................................ 9

3.4 Earnings and hours worked in the coffee sector ............................................................................................10

3.5 Company size: Does it matter? ............................................................................................................................15

4. Conclusions ..................................................................................................................................................................17

References ........................................................................................................................................................................18

Appendices .......................................................................................................................................................................19

Acknowledgements

This background note is one of three in a research series on wages and working conditions in different

sectors, including tea, coffee and banana. The reports seek to contribute to a better understanding

of the prevailing wages and working conditions in these selected sectors to feed into the knowledge

base for setting of adequate minimum wages, statutory or negotiated. These background notes are

undertaken as part of an ILO project on Indicators and methodologies for wage setting supported

by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands. The project seeks to develop indicators and

methodologies that will strengthen the capacity of governments and social partners to negotiate and

set adequate wage levels, which take into account the needs of workers and their families along with

economic factors. The project covers five pilot countries namely, Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia

and Vietnam. This report has been prepared by Luis Pinedo Caro under the supervision of Nicolas

Maitre.

Executive Summary

This study provides estimates on wages, employment levels and hours worked in the coffee sector in

five countries -all of them major coffee producers- namely, Costa Rica (15th largest producer), Ethiopia

(5th), India (7th), Indonesia (4th) and Viet Nam (2nd). This study is based on the analysis of 33 household

and labour force surveys from the 5 countries under review. Altogether, this report has used the

responses of 165,388 coffee workers over the last two decades representing

1

nearly 19 million workers.

1 After using the survey weights provided by the national statistical oces.

Some of the main estimates are the following:

X In the ve countries, there are more than 6

million workers employed in the coee sector,

although there is strong seasonality in the

sector. In Costa Rica and Viet Nam, the number

of workers decreases by 50 per cent or more,

depending on the period of the year.

X The share of women among coee workers

varies from an estimated 8 per cent in Costa Rica,

and 17 per cent in India, up to more than 40 per

cent in Ethiopia, Indonesia and Viet Nam.

X The age and education prole of workers in

the coee sector vary widely across the ve

countries, with workers being on average

younger and with lower educational attainments

in Ethiopia, and considerably older in Costa

Rica and with relatively higher educational

attainments in India, Indonesia and Viet Nam.

X While in Costa Rica and India a majority of

workers are paid employees, the coee sectors

of Indonesia, Viet Nam and Ethiopia obtain

most of their production from smallholder

farmers. In those latter countries, employees

are seldom hired and the use of unpaid labour is

commonplace.

X A remarkable characteristic of the employment

structure is the prevalence of women in unpaid

roles (unpaid family workers).

X In all countries average coee wages are far

below average country wages and lower than the

averages wages paid in the agricultural sector.

X Looking only at employees, estimated median

monthly earnings amount to approximately USD

20 in Ethiopia, USD 76 in Indonesia, USD 110 in

India, USD 116 in Viet Nam, up to USD 350 in

Costa Rica.

X Own-account workers earn USD 19 in Ethiopia,

USD 73 in Indonesia, USD 163 in India, USD 185 in

Viet Nam and USD 227 in Costa Rica.

X When using hourly earnings, own-account

workers earn more per hour than employees in

all of the countries, even though the earnings

ratio varies from country to country.

X Women in the coee sector earn substantially

less than men. Part of the gap arises because of

the relatively high number of women working as

unpaid family workers. Looking only at average

wages for employees, gender pay gaps in

monthly wages amount to 44.5 per cent in Costa

Rica, 12.4 per cent in Viet Nam, 34.9 in Indonesia

and 23.3 in India. With the exception of India and

Ethiopia, wage gaps are higher than the national

average gaps. Hourly gender wage gaps also

show that women earn less in all countries, the

gap ranging from 39.2 per cent in Costa Rica and

32.5 per cent in India to 8.3 per cent in Viet Nam.

X Time series data in Costa Rica and Viet Nam

shows that one of the most remarkable features

is the relatively constant purchasing power of

workers in the coee sector, with no observable

increase in earnings over the years.

X Estimated hours worked in the coee sector

range from 35.4 hours in Costa Rica, 39.4 hours

in Viet Nam, 40.5 hours in Indonesia, to 48.7

hours in India.

X In India and Viet Nam, a majority of coee

workers earn the minimum wage or more. Still, it

is estimated that in these two countries the share

of coee workers earning less than the minimum

wage amount to, respectively, 17.7 per cent and

25.9 per cent. Non-compliance is higher in Costa

Rica, with an estimated 45.4 per cent of workers

earning less than the minimum, and especially

in Indonesia, where only 9 per cent of the coee

employees earn the minimum wage or more. In

Ethiopia, there is no minimum wage.

X Data for Viet Nam and Costa Rica shows that

larger employers (with 10 employees or more)

pay higher wages, by respectively 14.5 per

cent and 8.4 per cent. Moreover, in Costa Rica

larger companies oer greater opportunities to

improve monthly wages by being able to oer

more work. On average, the workforce tends to

be better educated and larger companies make

more use of specialists, i.e. individuals in high-

skilled occupations.

1. Introduction

Coffee is one of the most traded products in the world, a truly global commodity that attracts

attention from several economic actors. As such, information on exported quantities, consumption

and price levels is commonplace and detailed studies can be found for several countries. Yet, not

as much is known about wages and working conditions in producing countries. The International

Labour Organization (ILO) has therefore embarked on a project aimed at improving the information

on wages, employment levels and hours worked in the coffee sector to fill the existing knowledge

gap, and to strengthen the ability of governments, social partners, and others to negotiate and set

adequate wage levels in the sector. This study covers the five pilot countries of the project -all of

them major coffee producers- namely, Costa Rica (15th largest producer),

2

Ethiopia (5th), India (7th),

Indonesia (4th) and Viet Nam (2nd).

Position, country Output (000’ Tons) Position, country Output (000’ Tons)

1. Brazil 3,744 6. Honduras 439

1,801 360

3. Colombia 831 8. Uganda 282

600 9. Mexico 261

452 86

This study is based on the analysis of 33 household and labour force surveys from the 5 countries

under review. These databases have provided useful time-series to explore and construct trends

and to compare the current conditions in the coffee sector across countries. Altogether, this report

has used the responses of 165,388 coffee workers over the last two decades representing

3

nearly

19 million workers.

In addition to basic information on working conditions, the analysis of the post-harvest modules

of the Ethiopian household survey allows us to obtain output figures as well as quantifying labour

demand. More importantly, it provides a rather unique snapshot of the Ethiopian coffee sector,

including its structure. Thanks to this dataset we are able to compare output figures and find

that Ethiopia’s coffee production may be larger than expected due to a large number of farms

cultivating coffee for their own consumption.

The report is divided into three sections. Section 2 describes the dataset and offers details on how

coffee workers are identified in each country. Section 3 contains the core of the analysis and it is

divided into five subsections. These describe the employment structure, some characteristics of the

workers such as their age and education profile, their monthly and hourly wages and their hours

worked. In addition, section 3.5 looks at company size and assesses whether scaling up businesses

pays off for workers. At last, Section 4 concludes.

2 See ICO’s ocial gures at http://www.ico.org/prices/po-production.pdf. Costa is ranked 15th due to China’s expected

output being estimated at 132,000 Tons for the 2018/2019 year, from statista.com.

3 After using the survey weights provided by the national statistical oces.

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

1

2. Database description

This study uses 33 household and labour force surveys from five countries, Costa Rica, Ethiopia,

India, Indonesia, and Viet Nam. For more information regarding the data sources, Table A.1 in

Appendix A provide a visual description of the type of survey, the exact years for which data have

been collected and the periodicity (monthly, quarterly) of the data.

Given the numerous sources of data an effort is made to harmonize a number of variables in a way

they can be used in a cross-country report. This harmonization has followed a similar process to the

one found in the Labour Force Micro-dataset of the Global Employment Trends for Youth 2017 and

2020, both published by the ILO.

The complete list of harmonized variables can be retrieved from the database documentation

which is available in the form of a separate Excel file. As a summary, variables concerning

age, educational attainment, region, labour market status, status in employment, economic

activity, occupation, hours worked, and earnings are included in the dataset. Even though the

documentation provides an explanation for all the variables contained in the dataset we offer

some additional details on how certain critical variables have been harmonized and the limitations/

comparability issues that may exist across countries/datasets.

Seasonality. Coffee, as many other agricultural products, is highly seasonal. If we were to ask

people on a random week whether they were involved or not in any coffee-related activity for at

least an hour during the previous week, chances are we would either overestimate (during peak

periods) or underestimate (off-season periods) both the average number of people involved and

the average number of hours worked in such activity. This issue has been dealt with in this study

by the generalization of quarterly or even monthly household and labour force surveys; the higher

periodicity has allowed us to calculate more accurate yearly averages and to better understand the

effects of seasonality on workers’ working conditions.

The labour force surveys of Costa Rica (2010-2018), Viet Nam (2011-2018) and India (2000, 2005 and

2012) are all carried out either quarterly or monthly and, thus, estimates from these surveys should

not suffer from seasonality bias. However, estimates from the Costa Rican household survey (2001-

2009), the Ethiopian household survey (2016) and the Indonesian labour force survey (2007, 2010

and 2018) are all based on interviews that took place during the third quarter of the year (Costa

Rica, Indonesia) or during the first quarter (Ethiopia). Having a single quarter may not produce a

major distortion in Indonesia because the country has two harvesting seasons, July-September

in the island of Java and November-January in Sumatra,

4

i.e. they may compensate each other.

However, in Costa Rica and Ethiopia employment figures are expected to be underestimated.

Identifying coffee workers in Indonesia. Indonesia follows the KBLI

5

2005 (2007 and 2010 LFS)

and the KBLI 2015 (2018 LFS) to assign economic activities to workers. These two classifications

are adapted from, respectively, the International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic

Activities (ISIC) rev.3 and rev.4. In both cases coffee has been placed together with tea, mate, and

cocoa (code 1135 in the KBLI 2005 and 1270 in the KBLI 2015). In order to isolate coffee workers, we

follow a geographical identification strategy based on the provincial distribution of each product’s

area planted. As a result of comparing the areas planted, coffee was found to be the leading

product in 13 Indonesian provinces and all labour involved in the coffee, tea or cocoa activities of

those provinces was assigned to the coffee sector. We can expect a 73.5 per cent accuracy in the

matching, i.e. roughly 3 out of 4 identified workers are actual coffee workers.

Identifying coffee workers in Ethiopia. The harmonization of employment figures in the Ethiopian

household survey goes beyond finding an activity code and needs to be described in detail. The

main issue is brought by economic activities not being disaggregated beyond some broad groups.

For example, all agricultural activities are put together, thus, not allowing us to identify coffee

4 See Appendix C for information on the season duration in each of the 5 countries of the study.

5 Klasikasi Baku Lapangan Usaha Indonesia, Indonesian Standard Industrial Classication.

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

2

workers. In order to circumvent this problem we use the so-called “Post-Harvest” modules of the

survey; a set of questions directed at every smallholder farm about their agricultural production.

Thanks to these modules we can identify coffee farms and distinguish among employers, own-

account workers and unpaid family workers based on the characteristics of the farm and the

workers’ responsibilities within the farm.

Unfortunately, the above-described strategy does not solve the problem of identifying labourers

(i.e. employees) in the coffee sector. In order to have an estimate on the number of people

employed by the farms, their wages or the characteristics of those employed we use the Ethiopian

Household Survey as if it were an enterprise survey. Based on the information reported by each

farm with respect to how many people were hired during the last harvesting season we are able

to collect average wages as well as the number of (paid) labourers hired. In both instances the

information comes disaggregated by gender and by age group. There are two caveats with respect

to how to interpret this information; first, labourers may have been counted more than once since

some of them may be going from farm to farm during the harvesting period. In this sense, the

number of workers cannot be compared to figures from other countries. Second, the information

collected from the farms refers to the harvesting period, i.e. it is an overestimation of the average

number of people the sector may be actually providing a job.

Assigning status in employment in Ethiopia. A recurrent issue when assigning statuses in

employment to smallholder farmers is related to the own-account/unpaid family worker dichotomy.

Usually women and children tend to be labelled unpaid family workers while men tend to hold the

own-account worker title. In Ethiopia we used the households’ own responses with respect to who

in the household was responsible for coffee parcels when assigning these statuses. As a result,

every person named as responsible of at least 1 parcel was assigned own-account worker status

-usually the husband and the wife. The rest of the household members -if working in agricultural

activities- are given an unpaid family worker status. Even though the results (see Figure 5) shows

a much more balanced gender split of statuses in employment than in other countries we did not

make any attempt to re-balance it as the criteria used seems to do justice to family members’ self-

reported managerial roles.

Earnings. Data on earnings exist for all five countries -with some limitations.

6

The most challenging

dataset is, again, Ethiopia. Smallholder farms are not asked about their average monthly profit -as it

is done in other surveys. Instead, they report how much coffee is produced, how much coffee they

have already sold, the price at which they sell it and the percentage of coffee they plan to sell (out of

their total production). Farmers that do not sell and do not expect to sell coffee (own consumption

only) are not considered employed even if they carried out farm activities during the reference

week. For those that had already sold some coffee the earnings were calculated by multiplying the

price per kilo received by the amount of output that is for sale. In the event farmers expect to sell

some coffee but have not done so yet, an average price calculated at the region level and is applied

to calculate their expected yearly earnings. Then, the earnings are divided by 12 so that the figure

can be compared to the ones from other countries.

To facilitate the comparability across countries and years, earnings were deflated/inflated to 2011

using the World Bank’s inflation rates. Then, all local currencies were converted to $USD using the

exchange rate that prevailed in 2011 and inflated to 2020 using, again, World Bank inflation rates.

All figures shown in this report are, thus, provided in 2020 $USD. Last but not least, the reader may

notice that even in the countries where employer’s earnings are available, they are seldom reported

throughout the report. This has to do with the small sample size usually surrounding this group of

workers.

6 India 2000 and Viet Nam 2011-2014 only provide earnings for employees. Indonesia does not provide earnings for

employers.

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

3

3.1 Employment levels in the coffee sector

The coffee sector may employ significant proportions of a country’s labour force. This is particularly

the case in Viet Nam, Costa Rica, and Ethiopia. In Indonesia, the estimated number of workers

is in line with a report that TechnoServe (2014) prepared for IDH. However, it may seem like a

contradiction to observe Indonesia’s total employment figure being slightly higher than that of Viet

Nam. Especially so in light of Viet Nam’s coffee output being in 2016

7

up to 1,461,000 tonnes, more

than double the Indonesian one, at 639,000 tonnes. In this case, the efficiency of each country’s

production may help us conciliate these seemingly contradictory facts. Viet Nam’s yield per hectare

is

8

around 2,400 kilos while the one of active Indonesian farmers barely reaches 800 kilos.

Local impact. The share of coffee workers in relation to the country total does not do justice to the

importance coffee production may have at the regional/province level.

9

For example, in Costa Rica

84.2 per cent of the workers are from the Central region, where they constitute 16.2 per cent of the

total employment in its rural areas. Note that we bring the distinction between the rural and urban

areas of the Central region because the capital, San José, is in the same region. This could downplay

the local impact of the coffee sector.

In Ethiopia, the local impact of the coffee sector is probably stronger in certain areas. The share

of total employment (ILO definition) of the coffee sector in the country’s south-eastern regions of

Gambela and the Southern Nations, Nationalities and People (SNNP) is up to, respectively, 23.5 and

17.8 per cent. These figures, which are very high on their own, do not reflect the full impact of the

coffee sector in the Ethiopian society due to the existence of millions of small-scale producers that

either do not sell any coffee or for whom coffee is not the main product sold. We invite the reader

to look at the box “Coffee in Ethiopia: Interpreting statistics” for a better understanding of the

impact of the coffee sector in the country.

Country Number (%) of all workers Share of women

Costa Rica, 2018 46,140 2.19 8.65

Ethiopia, 2016 2,612,508 6.56 42.11

India, 2012 411,791 0.1 17. 21

Indonesia, 2018 1,500,670 1.2 40.2

Viet Nam, 2018 1,439,712 2.67 43.96

Source: Harmonized household and labour force surveys of the relevant countries and author's own calculations,

latest year available.

Notes: The table shows the country-specic number of workers employed in the coee sector, the country-specic

share of workers employed in the coee sector and the country and sector-specic share of women working in the

coee sector.

7 Figures from De Agostini Geograa.

8 Figures from a report by the Canada-Indonesia Trade and Private Sector Assistance Project, 2018.

9 The interested reader may nd maps with the distribution of employment by country in Appendix D.

3. Working conditions in the coffee sector

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

4

Even though India ranks 7

th

in terms of coee production with 348,000 tonnes in 2016, the size of

the country prevents almost any activities from becoming relevant even at the local level. The only

exception is Karnataka, where 82.3 per cent of the Indian coee workers are employed. But even

in this state coee only represents 1.5 per cent of the total employment, and 2.2 per cent of the

employment in rural areas.

In terms of local impact we may observe the exact opposite in Viet Nam; the Central Highlands

region not only employs 91.7 per cent of all the coee workers of the country and produces most

of Viet Nam’s coee, it also provides an employment opportunity to 37.3 per cent of all the workers

in the region. The local importance of coee in the Central Highlands’ provinces has made the

region earn the label of the “Kingdom of Coee” thanks to fertile earth and the optimal altitude

and climate.

Indonesia oers a dierent picture; the production of coee is scattered all over the country even

if the plantations located in the islands of Java, Sumatra and Nusa Tenggara claim a larger share

of the local employment.

10

The dispersion of smallholder farms around the country’s numerous

islands may have favoured the atomization of the farms and increased the diculty for setting

up sustainability initiatives given they would need to incur a much higher cost. In terms of local

impact, I nd the coee taking the largest shares with respect to the local workers in the provinces

of Aceh (5.2 per cent), South Sumatra (7.1 per cent), Bengkulu (13.9 per cent) and Lampung (8.0 per

cent).

Seasonality in the coee sector. Seasonality may be just another variable to keep in mind for a

coee buyer or something that can be used to trade nancial products for speculators. However,

for coee workers and their families seasonal activities may be a constant struggle. Even if a given

job in a plantation is temporary in the sense that it will only last for a few weeks, the job of a picker

is arguably a permanent one. Many coee workers are constantly moving so as to nd plantations

in peak season.

A question that immediately arises is related to the importance of this phenomenon. A visual

overview is provided in Figure 1 for Costa Rica with quarterly data and in Figure 2 for Viet Nam,

this time with monthly data and both of them covering the 2011-2018 period. In both graphs

we may observe the already known seasonal patterns of Costa Rica,

11

October to March or 4th

and 1st quarter, and the slightly shorter one in Viet Nam,

12

November to February. According

to the graphs, employees are more aected by seasonality than own-account workers, with

employment levels plummeting as soon as the harvesting season is over. One way to measure

the extent to which employees are aected is by calculating the highest potential loss of

employment; this can be dened as the percentage by which the highest employee count within

a year decreases with respect to the lowest one in the same year. For example, in Costa Rica

the highest number of employees in 2016 was 45,528 in the rst quarter and the lowest was

22,392 in the second quarter of 2016, the percentage decrease is 50.8 per cent. In other words,

there would be potential to lose 5 out of every 10 employee jobs after the end of the season. On

average (2011-2018), in Costa Rica the potential employee loss is 51.5 per cent.

Source: Harmonized labour force survey of Costa Rica and author's own calculations, quarterly data, 2011-2018.

Notes: The gure shows the number of own-account workers (OAW) and employees in the Costa Rican coee sector

between 2011 and 2018.

10 Sulawesi is also known to be a main area of coee production. Please, see the data section in relation to the identi-

cation of coee workers in Indonesia for an explanation of why I cannot mention it.

11 Dates obtained from Driftaway Coee at https://driftaway.coee/when-is-coee-harvested/.

12 Dates obtained from Strauss at https://www.strauss-group.com/cr_newsmention/the-coee-secrets-of-vietnam-the-

story-of-beans-in-distant-elds/

50.000

40.000

30.000

20.000

10.000

0

Workers

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4

Employee

OAW

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

5

Box. Coee in Ethiopia: Interpreting statistics.

The implementation of the ILO employment denition in Ethiopia yields a mere 2.6 million active farmers in

Ethiopia. Yet according to Minten (2014) around 4 million families and a quarter of the country’s population are

involved to a greater or lesser extent in coee production. Can we reconcile these two gures?

Yes, probably; it all depends on how workers are counted. In fact, our estimates from the Ethiopian Household

Survey show that 4.6 million families involving 26.2 million individuals and a maximum of 3.5 million labourers

were involved at some point during the 2015/2016 cycle in coee production. These gures are much closer

to the just cited sources’ estimates. In fact, we nd that in areas populated by tens of thousands of tiny coee

producers like the SNNP or Oromia the percentage of workers involved in coee production reaches, respectively,

55.6 per cent and 31.0 per cent. Obviously, there are not 4.6 million major coee plantations in Ethiopia lled with

labourers working every week over large areas of land. In fact, half of the Ethiopian coee producing households

cultivated less than 310 square metres with coee trees while only 25 per cent cultivated an area larger than 1,000

square metres (equivalent to 0.1 ha). Production-wise we are able to retrieve a similar picture; half of the farms

produced less than 43 kilos of coee while only 25 per cent of the farms yielded more than 131 kilos.

The above-mentioned farm size distribution should also be kept in mind when reading estimates on total output.

It may be surprising to see sources like Gro Intelligence reporting Ethiopia’s coee output to be around 390,000

tonnes in 2016 while the microdata estimates are up to 566,353 tonnes. These two gures may be reconciled too if

we disregard non-market oriented farms (farms that produce coee exclusively for their own consumption). Doing

so would bring the gure down to 523,314 tonnes. It can be brought closer to the ocial production estimates

if we were to disregard small farms (with less than 500 square metres of area cultivated) even if they sell some

of their output. This would bring the total output further down to 428,557 tonnes, almost matching the ocial

gures.

Is it reasonable to think that the ocial gures underestimate Ethiopia’s coee output? It is a possibility, es-

pecially once we weigh in the eort made by the Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia to nd a representative

sample of small coee producers and how dicult it would be to trace these farms without a face to face inter-

view. Indeed, only satellite imagery could one day, perhaps, be able to bring out the production of amounts of

coee ranging between 1 to 60 kilos that no one except the people that cultivated it know of their existence.

All in all, what the dierent gures on employment and production are telling us is the existence of a truly diverse

population of coee producers. On the one hand, there is a rather small number of relatively large plantations

while, on the other hand, the majority of coee producers remain away from the markets. As a consequence,

policies intended to help coee producers should be tailored to a specic type of producer. Some may be directed

at connecting tiny farms to the market so that they can sell some of their output locally. Some may be directed at

improving the competitiveness, including the yield per hectare and the product quality management system, of

those aiming at exporting their production.

In Vietnam, the potential loss of employment is even higher, at 54.5 per cent over the 2011-2018

period, i.e. more than 5 jobs out of every 10 would be destroyed after the end of the peak season.

The eects are milder for own-account workers but still signicant, 15.3 per cent of this type

of jobs in Viet Nam and 27.0 in Costa Rica can be expected to disappear at the end of the peak

season.

It should be noted that in spite of the existence of monthly data in Viet Nam, the potential loss

of employment at the end of the peak season have been calculated with quarterly data in both

countries. This is to facilitate the comparison of the gures across countries. In addition, the

comparisons between monthly employment levels are done yearly because in both cases the

number of workers have been increasing.

Indeed, a particularity of the coee industry is its continuous expansion in recent years in all

countries under the scope of this report but India. In India (mostly Karnataka) the number of

coee workers have had a negative evolution, with 440,671 in 2000 and 411,791 in 2012. This

contrasts with the evolution the sector have had in Viet Nam (Figure 2), where the number of

workers grew from 1,086,726 in 2011 to 1,439,712 in 2018, a 32.5 per cent increase. Likewise, in

Costa Rica (Figure 1) the number of workers increased by 26.3 since 2011 after touching rock

bottom in 2009. Costa Rica’s low in 2009 was due to a number of circumstances, like the ageing of

the plantations and a sharp and severe depreciation of the local currency, the Colon, against the

American Dollar, losing around 20 per cent of its value. Indonesia too, attested an increase in the

number of workers employed. It increased by 20.6 per cent between 2007 and 2018.

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

6

Source: Harmonized labour force survey of Viet Nam and author's own calculations, monthly data, 2011-2018.

Notes: The gure shows the number of own-account workers (OAW) and employees in the Vietnamese coee sector

between 2011 and 2018.

Please, note that even if coffee production generally fluctuates together with employment levels

(Indonesia, Viet Nam, India) this was not the case in Costa Rica, i.e. employment gains may also be

obtained via an enhanced product quality or a reduction in hours worked. To exemplify the focus

on quality, it may be noted that Costa Rica had a 30 year ban on lower quality Robusta variety until

2018.

13

3.2 Socio-demographics of coffee workers

The average age of coffee workers depends on several factors. First of all on the age distribution

of the respective country’s labour force. As such, we find much younger workers in Ethiopia than

in Costa Rica or Indonesia. So young that 21.6 per cent of its coffee workers are reported to be 14

years old or less.

The full age distribution of coffee workers is provided in Figure 3 for convenience. Thanks to this

figure it is possible to link the weak employment growth in the Indian coffee sector with the lack of

young people willing to enter the sector. Even though the distribution appears to be either well-

balanced (Costa Rica, Viet Nam) or in favour of young people (Ethiopia), in India more than 70 per

cent of the coffee workers are older than 35 years old. Something similar happens in Indonesia,

with a weaker supply of young labour in the coffee sector.

All Workers Coe sector

Country Average Median 10th percentile 90th percentile

Costa Rica 40.65 47.01 49 22

68

Ethiopia 29.14 30.09 26 11

55

India 37.83 41.13 45 23

55

Indonesia 40.49 43.32 43 23

64

Viet Nam 40.82 38.68 39 20

57

Source: Harmonized household and labour force surveys of the relevant countries and author's own calculations,

latest year available.

Notes: The table shows the average, median, 10th and 90th percentiles of the age distribution of coee workers. It

also shows the average age of all workers for comparison purposes.

13 The ban was lifted due to changes in climate as Robusta was argued to be more attractive. See La Nación announcing

the lift as of 16

th

May 2018 at: https://www.nacion.com/economia/agro/productores-podran-sembrar-cafe-robusta-en-zo-

nas/IT7G5AM7SZBXNCVISUVZVTFZLM/story/

0,8

0,6

0,4

0,2

0

Workers (millions)

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

Employee

OAW

Jan

Apr

Jul

Oct

Jan

Apr

Jul

Oct

Jan

Apr

Jul

Oct

Jan

Apr

Jul

Oct

Jan

Apr

Jul

Oct

Jan

Apr

Jul

Oct

Jan

Apr

Jul

Oct

Jan

Apr

Jul

Oct

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

7

Another element of interest is the high share of workers aged 66 or older in Costa Rica. Costa Rica

is one of the few countries with more employees than own-account workers (the other being India)

and we would expect Costa Rican workers would exit the labour force sooner. An explanation could

be the higher life expectancy Costa Ricans have in comparison with the other countries under

analysis (around 10 years difference on average). Moreover, most +65 year old Costa Rican coffee

workers are self-employed (75.6 per cent), a group that tends to remain longer in the workforce. In

contrast, among workers aged less than 66 years old we find a lower share (39.8 per cent) of self-

employed workers.

Source: Harmonized household and labour force surveys of the relevant countries and author's own calculations,

latest year available.

Notes: The gure shows the country-specic share of coee workers in a given age range for 7 age groups.

Generally coee workers do not stay in school past the early secondary years and rarely we

can observe university graduates being part of their workforce. At rst, it may look like there is

little benet in spending longer years in school so as to work in the coee sector. Figures tell us

otherwise, though.

For example, a comparison of the earnings of self-employed workers (excluding unpaid family

workers) by level of education showcases the critical importance of the time spent in school. This

comparison is done by means of a linear regression where the variables under analysis is the

logarithm of monthly earnings in 2020 $USD of own-account workers and employers. Among the

covariates I added binary variables for 3 education levels, primary, secondary and tertiary (no

education being the reference group) and country binary variables to control for the dierent

levels accruing in each country (meaning that Costa Rica, with much higher earnings levels, now it

is under control).

Source: Harmonized household and labour force surveys of the relevant countries and author's own calculations,

latest year available.

Notes: The gure shows the country-specic share of coee workers in a given level of education for 5 levels of edu-

cational attainment. Levels are completed unless otherwise stated.

The results of this regression show that primary education, secondary education, and tertiary

education increase an entrepreneur’s prot by, respectively, 30.9 per cent, 44.9 per cent and 63.9

per cent. These percentages could, in many cases boost prot levels beyond poverty lines and

local minimum wages (see section 3.4 of the report). In addition, all the increases are statistically

signicant, with a sample of 48,758 self-employed representing 6.5 million individuals from ve

countries and a R2 coecient of 0.2202.

Percentage (%)

6-15

16-25

26-35

36-45 46-55

56-65

66+

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Costa Rica Ethiopia India

Indonesia Viet Nam

Percentage (%)

Primary

Secondary

Tertiary

Some primary

No formal education

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Costa Rica Ethiopia India

Indonesia Viet Nam

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

8

3.3 Structure of the workforce in the coffee sector

The ve countries under study show more dierences with one another than similarities; this is

the case in, for instance, productivity or geographical distribution of the production. The type of

workers

14

employed is no exception. From Costa Rica and India, who has a majority of its workers

employed in relatively big (>10 employees) plantations, to Indonesia, Viet Nam and Ethiopia where

employees are seldom hired and where the use of unpaid labour is commonplace.

15

In fact, even

two countries like Viet Nam and Indonesia that show similar structures of employment diverge in

the trend. On the one hand, Viet Nam has been showcasing a moderate growth in the number of

employees over the last decade. The share of employees increased from 7.9 per cent in 2020 to 11.1

in 2018. On the other hand, the same share in Indonesia has remained almost stagnant, changing

from 8.4 in 2007 to 8.9 in 2018. The notable change in Viet Nam is one of the few structural

changes attested in the coee sector of these 5 countries. In addition, it may also be one of

the likely outcomes of the 10-year plan that the Vietnamese government adopted to improve

agricultural productivity in the country.

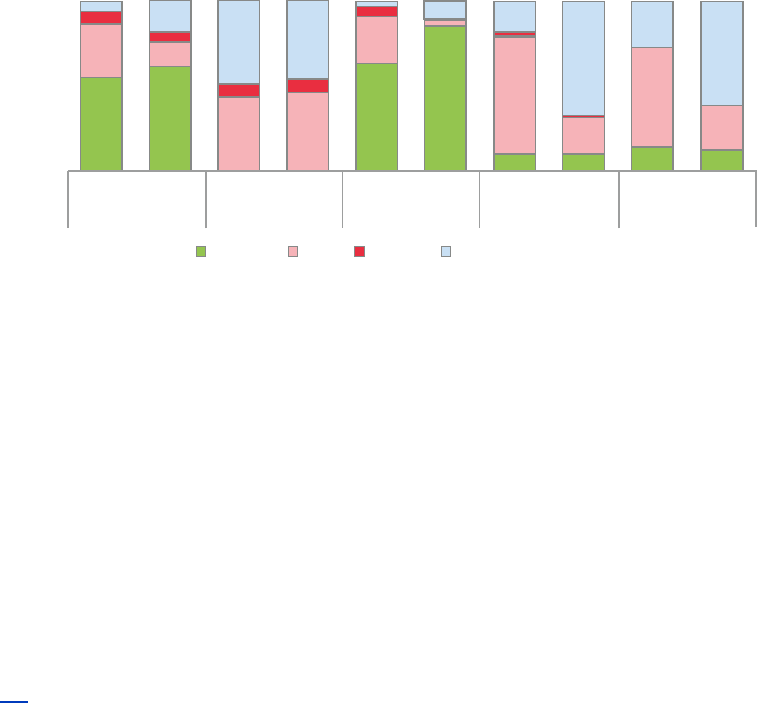

A noticeable characteristic of the employment structure (Figure 5) is the prevalence of women

in unpaid roles (unpaid family workers). This is the case in all countries but Ethiopia, where the

assignment from the raw data based on self-reported control over parcels was made. It might be

that Ethiopia is an exception and in countries like Indonesia or Viet Nam women take on minor

roles in the family business. However, if this were not the case, the assignment of statuses should,

perhaps, be revised. It may just be a statistical matter (in practice, coee producing families do not

follow international classications when managing a farm) but it still distorts the gender picture

and may help supporting damaging gender stereotypes.

Percentage (%)

Employee

Unpaid family worker

OAW

Employer

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Costa Rica Ethiopia India Indonesia Viet Nam

Men Women Men Women Men Women Men Women Men Women

Source: Harmonized household and labour force surveys of the relevant countries and author's own calculations,

latest year available.

Notes: The gure shows country, sector and sex-specic percentages of coee workers in four employment sta-

tuses, employee, own-account worker (OAW), employer and unpaid family worker.

In some countries the coee sector employs mostly employees and in others self-employed

workers. This has a likely inuence in the occupations held by workers. It can be seen in Table 4

that Costa Rica and India (employee-intensive countries) appear to be the only ones employing

non-eld workers. This suggests that the plantations tend to be bigger, more vertically integrated

and more capable of taking on coee processing activities. The vertical integration of a supply

chain should, in principle, allow companies to increase prot levels by increasing the value added

to the product.

Still, even though India and Costa Rica seem to host some big plantations, most of the people

employed are eld workers. The share of this type of worker ranges from 94.7 per cent in India

(lowest) to 99.9 per cent in Ethiopia (lowest). As a result, the earnings/prots (for self-employed)

and wages (for employees) oered in this report are averaged across the coee sector, without

distinguishing among occupations.

14 By type of worker is meant the categories of the International Classication of Status in Employment, ICSE-93. Even

though a new classication has been brought up recently, the ICSE-18, the older version is still widely utilized by national

statistical systems and it is the one used in the micro-datasets analysed in this report.

15 See section 2 of this report, it explains very few farms rely on paid labour for the harvest of coee.

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

9

Viet Nam

Professionals and technicians 0.9 0.0 1.1 0.0

0.1

Salesmen, clerks 0.9 0.0 0.0 0.1

0.0

Factory workers 2.1 0.0 4.2 0.2

0.2

Field workers 96.1 100.0 94.7 99.7

99.8

Source: Harmonized household and labour force surveys of the relevant countries and author's own calculations,

latest year available.

Notes: The table shows country and sector-specic shares of coee workers in four occupations. Occupations are

dened using ISCO-08 codes, "Professionals and technicians" refer to major groups 1, 2 and 3; "Salesmen, clerks" to

groups 4 and 5; "Factory workers" to groups 7, 8 and subgroups 91, 93, 94, 95 and 96; at last, "Field workers" refer to

the group 6 and the subgroup 92.

3.4 Earnings and hours worked in the coffee sector

Information regarding wages and own-account workers’ earnings exists for all ve countries.

Unfortunately, we are not able to report detailed information on employers’ earnings levels for all

of them. In India, for example, the sample size is too small and the method of calculating earnings

(based on thresholds) too unreliable to estimate distributions with an expected long right tail. In

Indonesia, even though the LFS provides own-account workers’ earnings, it excludes employers

from that same set of questions. Something similar happens in Viet Nam, whose labour force

survey was not providing information on earnings for any self-employed worker until 2015. This

shortage of information is felt in Figure 6, where the time-series on monthly labour earnings for

Vietnamese own-account workers only covers the 2015-2018 period.

Labour earnings in the coee sector vary widely. From 382.1 $USD earned monthly by Costa

Rican plantation employees to the 37.5 $USD earned by Ethiopian eld workers during the

harvesting season. How come there is a 10-fold dierence in wages for an export-oriented

good like the coee? First of all, not all coees are regarded equally; marketing, quality control

processes (including the quality and the amount of pesticides) and the type of coee variety

all aect the price received by the producer and, as a result, aect wages as well. In addition,

wages are adjusted to the income level of the country where workers live. That said, it should also

be noted that the process whereby wages adjust to local rates is not a natural one. It happens

because workers have little bargaining power, or because they do not have much better outside

opportunities.

Average Median

Country Employee OAW Employer Employee OAW Employer

Costa Rica 382.1 331.7 594.9 349.7 226.9 393.9

Ethiopia 37.5 43.1 220.2 20.5 18.9 138.3

India 104.4 167.7 na 109.6 162.5 na

Indonesia 86.2 100.1 na 76.2 73.3 na

Viet Nam 125.2 222.3 446.6 115.6 184.9 308.2

Source: Harmonized household and labour force surveys of the relevant countries and author's own calculations,

latest year available.

Notes: The table shows summary statistics on monthly labour earnings by status in employment. Earnings measured

in 2020 $USD.

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

10

Women in the coffee sector earn substantially less than men, this can be seen in Table 6, left hand

side columns referring to all workers in the sector. The exception to this trend is Ethiopia although

as it happens with other statistics shown in the report, this is due to the way status in employment

is allocated to household members. Therefore, figures cannot be compared.

Leaving Ethiopia aside for the above-mentioned considerations, the relatively high number of

women working as unpaid family workers may be artificially increasing the gender pay gap. In an

attempt to cancel this effect, the four right-hand side columns of Table 6 show average wages for

employees. Gender pay gaps using this methodology are 44.5 per cent in Costa Rica, 12.4 per cent

in Viet Nam, 34.9 in Indonesia and 23.3 in India. With the exception of India and Ethiopia, these

wage gaps are higher than the national average gaps (same methodology, using only employees).

All workers Employees

Average Median Average Median

Country Men Women Men Women Men Women Men Women

Costa Rica 362.9 256.1 311.9 151.9 399.3 221.5 368.6 189.1

Ethiopia 36.7 35.6 0.5 3.1 37.4 25.0 34.4 23.0

India 129.7 79.0 124.3 78.3 110.1 84.4 109.6 78.3

Indonesia 85.9 23.3 6 4.1 0.0 101.2 65.9 88.0 59.6

Viet Nam 163.7 61.1 134.8 0.0 131.5 115.2 119.4 104.0

Source: Harmonized household and labour force surveys of the relevant countries and author's own calculations,

latest year available.

Notes: The table shows summary statistics on monthly labour earnings by sex. Earnings measured in 2020 $USD.

Employees not included in Ethiopia’s gures.

The availability of reliable and comparable time series data in Costa Rica and Viet Nam allows us

to look into how purchasing power has been evolving for coffee workers. Figure 6 shows monthly

earnings measured in 2020 $USD from 2011 to 2018 using monthly (Viet Nam) and quarterly data

(Costa Rica). Note that data on own-account workers’ earnings is not available in Viet Nam between

2011 and 2014. One of the main features is the relatively constant purchasing power of workers

in the coffee sector. Still, even if workers seem to maintain the same level of real earnings, the

presence of sharp fluctuations in average earnings are a source of concern and a probable cause of

financial distress.

From the point of view of an international comparison, it may be surprising to observe how

different the earnings’ levels are between Viet Nam and Costa Rica. Even more surprising is to

observe that the differences are not homogenous across statuses in employment. Costa Rican

employees earn 3 times more than the Vietnamese ones (2011-2018) but among own-account

workers the difference is reduced to 1.5 times (2015-2018). That hints that even though productivity

related reasons may reduce earnings by 50 per cent, local employers may be using their bargaining

power to set employees’ wages based on local labour market conditions.

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

11

Source: Harmonized labour force survey of Viet Nam and Costa Rica and author's own calculations.

Notes: The gure shows average monthly labour earnings by status in employment in Viet Nam and Costa Rica,

2011-2018, 2020 $USD. Data not available for own-account workers for the 2011-2014 period in Viet Nam.

Similar conclusions in terms of bargaining power can be reached by looking at hourly earnings

($USD 2020) in Table 5. The OAW-employee earnings ratio varies from country to country, yet

own-account workers earn more per hour than employees in all of them. I find the OAW-employee

ratio to be smaller in Indonesia. The Indian coffee plantations do not have yields as low as the

Indonesian ones although the ones accruing to own-account workers are probably not far from

them based on their profit levels. Even though the comparison between employees’ wages and

own-account workers’ earnings is revealing, the lack of information on employer earnings in India

and in Indonesia does not allow us to reach more detailed conclusions.

Hourly wages (employees) Hourly earnings (OAW)

Country Coffee Agriculture Country Minimum

Wage

Coffee Agriculture Country

Costa Rica 2.53 2.87 4.51 2.38 2.16 2.34 3.23

Ethiopia 0.18 na 0.90 na 0.21 0.30 0.32

India 0.49 0.37 0.74 0.31-0.51 0.80 0.70 0.72

Indonesia 0.51 0.77 1.29 0.77-1.44 0.67 1.07 1.17

Viet Nam 0.77 0.75 1.10 0.51 1.28 0.87 1.09

Source: Harmonized household and labour force surveys of the relevant countries, ocial minimum wages and

author's own calculations, latest year available.

Notes: The table shows average hourly labour earnings in 2020 $USD for employees and own-account workers. In ad-

dition, it shows hourly minimum wages wherever applicable; ranges are shown for countries where minimum wages

vary by region, only the regions with coee workers are considered.

Hourly gender wage gaps show that women earn less in all countries although the gap is not

uniform. It goes from 39.2 per cent in Costa Rica and 32.5 per cent in India to 8.3 per cent in Viet

Nam. The 30 percentage points difference attested between the gaps of Costa Rica and Viet Nam

might suggests the existence of varying degrees of discrimination.

500

400

300

200

100

0

$ USD 2020

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

Employee

OAW

Jan

Jul

Jan

Jul

Jan

Jul

Jan

Jul

Jan

Jul

Jan

Jul

Jan

Jul

Jan

Jul

(a) Viet Nam

500

400

300

200

100

0

$ USD 2020

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

Employee

OAW

(b) Costa Rica

Q1Q3 Q1Q3 Q1Q3 Q1Q3 Q1Q3Q1Q3 Q1Q3 Q1Q3

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

12

In all countries average coffee wages are far from average country wages. The difference is

particularly dramatic in Ethiopia, with the average employee earning five times more than the

average field worker. To better understand the Ethiopian case we should keep in mind that only

1 in 10 workers are employees -and half of those are civil servants-, in other words, precarious

employee jobs are relatively scarce.

The average number of weekly hours worked is shown in Table 8. The averages

are provided separately for employees and own-account workers. In addition, we provide -right

column- the number of hours that constitute a normal workweek. Generally speaking hours

worked do not seem to be excessive. India stands out of the group with 48.7 hours for employees

and 47.8 for own-account workers. Ethiopia, in turn, showcases very small figures. In the case of

Ethiopia it is necessary to remember the hours worked were recorded in March -low season- and

by no means they can be taken as the yearly average. Still, Ethiopia also shows a country average

at 24.6 hours a week. This may be explained by a high rate of underemployment among the

self-employed as well as multitasking between farm, and non-farm work, which may reduce the

number of hours spent in the primary job. Ethiopian figures are recorded in low season and they

may pick up if we were to measure them in Autumn or early Winter.

Employees Own-account workers

Country Coffee Agriculture Country Coffee Agriculture Country Workweek

Costa Rica 35.4 46.3 44.4 37. 3 37.5 36.0 48

Ethiopia 39.9 18.3 22.6 24.6 48

India 48.7 47.6 51.0 47.8 50.6 51.3 48

Indonesia 40.5 39.9 44.4 38.1 33.0 40.9 40

Viet Nam 39.4 44.2 47.4 40.9 33.3 39.0 48

Source: Harmonized household and labour force surveys of the relevant countries and author's own calculations,

latest year available.

Notes: The table shows the country-specic number of weekly hours worked in the coee sector, in the agricultural

sector and in the country as a whole.

A reduction in hours worked is not the only possibility to reduce activity levels in the low season. As

an alternative, farmers and employees could stop working altogether while the remaining workers

continue working a similar number of hours all year long. I use the Vietnamese and Costa Rican

time series to exemplify the two mentioned possibilities, see Figure 7.

Source: Harmonized labour force survey of Costa Rica and Viet Nam and author's own calculations, 2011-2018.

Notes: The gure shows average weekly hours worked in the Costa Rican and Vietnamese coee sector by status in

employment for employees and own-account workers.

55

50

45

40

35

30

Weekly hours

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

Employee

OAW

(a) Viet Nam

Q1 Q4 Q3 Q2 Q1 Q4 Q3 Q2 Q1 Q4 Q3

55

50

45

40

35

30

Weekly hours

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

Employee

OAW

(b) Costa Rica

Q1 Q4 Q3 Q2 Q1 Q4 Q3 Q2 Q1 Q4 Q3

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

13

On the left hand-side of Figure 7 we show weekly hours of work in the Vietnamese coffee sector

from 2011 to 2018 by quarter and by status in employment for employees and own-account

workers. According to the data, Viet Nam is a case of adjustments via employment levels (see

Figure 2) while keeping the hours worked by both, employees, and own-account workers, relatively

constant across months. The right-hand side of Figure 7 shows the same statistic for Costa Rica.

In this country the type of adjustments in off-season periods vary by status in employment. For

employees we find that both, employment levels and hours worked are adjusted downwards.

On the other hand, Costa Rican own-account workers do not see their number reduced in the

low season, in contrast with their Vietnamese counterparts see their working hours significantly

reduced.

In addition to seasonality, Figure 7 (a) allows us to attest a significant reduction in the weekly hours

worked of Vietnamese employees. This reduction paired with constant real monthly wages during

the same period translate in higher earnings per hour.

. Compliance with prevailing minimum wages is desirable and -if

minimum wages are calculated by taking into account not only economic factors but also the need

of workers and their families - it is a measure that may tell us something about the living conditions

of the workers. With this in mind we estimated the compliance level for four of the five countries of

the study, having to exclude Ethiopia because it does not have a minimum wage. These calculations

are shown in Table 9, where the share of employees whose earnings fall below 95 per cent,

between 95 and 105 per cent, and above 105 per cent are reported.

In addition to higher occupational rates, Costa Rica has a national minimum wage (the minimum

minimorum) that applies to all regions, but Viet Nam, India and Indonesia use regional minimum

wages, sometimes combined with occupational minimum wages. In these countries compliance is

calculated at the state (India), province (Indonesia) and regional (Viet Nam) level. In particular, for

Viet Nam we use the minimum wage that applies in Region IV for 2018, which is the one applying to

the location of coffee plantations. In India, there are five provinces where coffee was produced in

2012, Mizoram, Tripura, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu; we use the respective states’ minimum

wages. At last, we use the 2018 minimum wages for the 12 provinces of Indonesia where coffee

producers were identified.

16

Costa Rica India Indonesia Viet Nam

Minimum

wage

Employees OAW Employees OAW Employees OAW Employees OAW

<95% 45.4 74.3 17.7 9.1 91.0 84.9 25.9 11.6

95%-105% 14.3 5.2 0.0 0.0 2.8 2.9 4.8 2.7

>105% 40.3 20.6 82.2 90.9 6.2 12.2 69.4 85.7

Source: Harmonized household and labour force surveys of the relevant countries, ocial minimum wages and

author's own calculations, latest year available.

Notes: The table shows the country, sector and status in employment-specic share of workers earnings less than

95%, between 95% and 105% and above 105% of the applicable hourly minimum wage. Minimum wages do not apply

to self-employed workers, their potential compliance levels are shown for informative purposes.

In addition to compliance levels for employees we also report them for own-account workers.

OAW’s are not subject to minimum wage legislation and the figures does not have any legal

meaning. They are shown for information purposes only.

We distinguish different cases from the data of Table 9. In India and Viet Nam, a majority of coffee

workers earn the minimum wage or more. It is estimated that in these two countries the share

of workers earning less than the minimum wage amount to, respectively, 17.7 per cent and 25.9

per cent. Non-compliance is higher in Costa Rica, with an estimated 45.4 per cent of workers

16 These provinces are Aceh, North Sumatra, Jambi, South Sumatra, Bengkulu, Lampung, Central Java, East Java, Bali,

West Nusa Tenggara, East Nusa Tenggara, and West Kalimantan. See Section 2, data description, for an explanation of

why coee was not found in other provinces.

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

14

earning less than the minimum, and especially in Indonesia, where only 6.2 per cent of the coffee

employees earn more than the minimum wage.

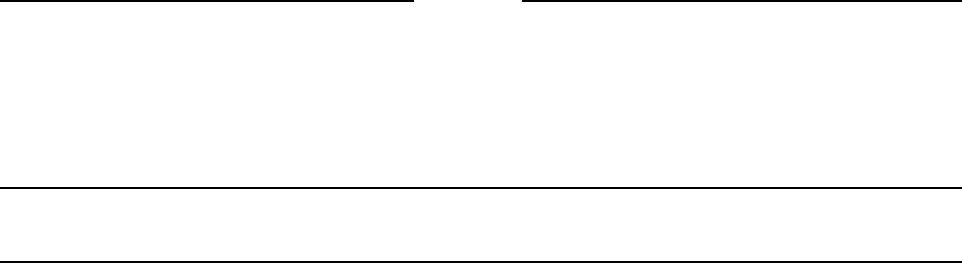

Sections 3.1 to 3.4 distinguish between employees and own-account workers. The distinction

is useful for several reasons but still the efficiency of companies with only a handful employees

may not differ much from the one achieved by a smallholder farm. We take advantage of the

information on company size in certain labour force surveys (Costa Rica and Viet Nam) to further

split employees between those working in micro businesses (less than 10 workers) and in bigger

companies.

Self-employed 45.2 92.1

<10 employees 41.1 5.3

10+ employees 13.7 2.6

Source: Harmonized household and labour force surveys of the relevant countries and author's own calculations,

latest year available.

Notes: The table shows the country and sector-specic share of self-employed in the coee sector. In addition,

it shows the percentage of employees working in coee companies with less than 10 and 10 or more employees.

Figures represent the yearly average, not a particular quarter.

The purpose is to identify whether size matters for workers’ working conditions. Also to see

whether there are efficiency gains and, more importantly, whether they reach coffee labourers.

Unfortunately, company size is elusive; Indonesia does not ask that type of information to

respondents and India avoids asking that information to certain agricultural workers. In Ethiopia,

even though we do have information on company size the structure of the data does not allow us

to investigate further coffee employees. In Viet Nam data on company size stopped being collected

in 2012 while only Costa Rica continues asking regularly this question all workers. This section is,

thus, filled with information from Costa Rica (2018) and Viet Nam (2011). The former is a country

that relies extensively on employees (54.8 per cent) for coffee production and the latter a country

that historically has not used many employees but has started to increasingly rely on them over the

last decade.

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

15

Source: Harmonized household and labour force survey of Costa Rica and author's own calculations, 2001-2018.

Notes: The gure shows the country and sector-specic share of workers in three categories, self-employed (own-ac-

count workers, employers, and unpaid family workers), employees in companies that have less than 10 employees

and employees in companies with 10 or more employees.

Even if they provide jobs to a small share of the coffee workers, we were able to find companies

with 10 or more employees in both countries. These companies take on 13.7 per cent and 2.6

per cent of total coffee employment in, respectively, Costa Rica and Viet Nam. On top of this, it is

possible to look at the employment shares in the coffee sector of Costa Rica since 2001 (Figure 8).

Even if it looks like the share of employment taken by the relatively large companies has decreased

over the last 20 years, it has more likely remained constant. The reason is likely due to the change in

the data sources from 2010 onwards, going from the household survey to the labour force survey.

It may be guessed that there was a change in methodology when assigning employer status,

arguably stricter in the labour force survey (2010-2018).

Hourly wage Hours worked Secondary+ High skilled

Less than 10 2.48 32.3 15.1 0.00

10 or more 2.70 44.9 45.2 0.80

Less than 10 0.64 44.6 12.8 0.00

10 or more 0.74 45.2 28.2 0.37

Source: Harmonized household and labour force surveys of the relevant countries and author's own calculations,

latest year available, surveys represent the yearly average, not a particular quarter.

Notes: The table shows country, sector and size-specic average hourly wages ($USD 2020), weekly hours worked,

share of workers with secondary or tertiary education and share of high skilled workers in the coee industry of Viet

Nam and Costa Rica. High skilled refers to employees classied within groups 1, 2 or 3 of the ISCO-08 classication.

In what follows we analyze four indicators by company size; hourly wages measured in 2020

$USD, weekly hours worked, the educational attainment distribution of the workforce and the

skill required in the occupations held by the employees. In all of them we find that company size

matters and scaling up coffee production may be positive for workers. In terms of wages we find

increases of 14.5 per cent and 8.4 per cent in, respectively, Viet Nam and Costa Rica. Moreover, in

Costa Rica larger companies offer greater opportunities to improve monthly wages by being able

to offer more work (12.6 hours per week). On average, the workforce tends to be better educated

and, more importantly, bigger companies make use of specialists, i.e. individuals in high-skilled

occupations, which probably has a positive effect on companies’ profit level.

Self-employed

10+ employees

<10 employees

100%

80%

60%

40%

20%

0

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

16

This report analyzes the employment structure and the working conditions of the coffee sector

in five of the world’s major producers, Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, and Viet Nam. This

report benefits from the harmonization of 33 household and labour force surveys. Thanks to this

unique database we are able to look at the coffee sector from a cross-country perspective as well

as using historical data.

The study shows the diverse employment structures. While Costa Rica and India tend to rely on

employees, the coffee sectors of Indonesia, Viet Nam and Ethiopia obtain most of their production

from smallholder farmers.

The employment structure seems to have a direct influence on several aspects of working

conditions. One of them is the regularity of employment and the average number of hours worked.

Due to seasonality, both fluctuate much more for employees than they do for own-account

workers. For example, in Viet Nam 51.5 per cent and in Costa Rica 54.5 per cent of the sector wage

employment is destroyed after every peak season. The employment structure also affects gender

roles due to the classic dichotomy between unpaid family labour and own-account worker statuses.

As it is common in agricultural activities women tend to be assigned the former status, boosting, as

a result, gender pay gaps.

From a gender perspective we find that female employees earn less (per hour) than men in all

countries under study. Still, gender pay gaps differ widely from country to country. Costa Rica leads

the way with a 39.2 per cent wage gap while Viet Nam showcases the smallest gap at 8.3 per cent.

This hints that pay differentials may be influenced by the countries’ respective gender roles and

employers’ attitudes and beliefs.

At the country level we find wages are much lower than the country averages and even lower than

the averages wages paid in the agricultural sector. There is also substantial non-compliance with

minimum wages. Questions thus arise on what could be done in the future to further improve

wages and productivity with a view to ensuring a sustainable coffee sector in which workers’ wages

and earnings are sufficient to meet the basic needs of their families.

4. Conclusions

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

17

References

Minten B. (2014). Structure and performance of Ethiopia’s coffee export sector. ESSP Working papers

No. 66 from International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

______. (2017). IFPRI blog. Available at https://www.ifpri.org/blog/ethiopias-coffee-farmers-

struggle-realize-benefits-international-markets

Petit, N. (2007). Ethiopia’s coffee sector: A bitter or better future? Journal of Agrarian Change, No. 7, Vol.

2, pp. 225-262, 2007.

TPSA (2018). An analysis of the global value chain for Indonesian coffee exports. Report, January

2018, by the Canada-Indonesia Trade and Private Sector Assistance Project.

TechnoServe (2014). Indonesia: A business case for sustainable coffee production. An industry study by

TechnoServe for the Sustainable Coffee Program, powered by IDH, 2014.

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

18

Appendices

Appendix A. Data availability and periodicity

TABLE A.1 SOURCES, TYPE OF DATA AND YEARS AVAILABLE, BY COUNTRY

Country

Year Costa Rica Ethiopia India Indonesia Vietnam

2000 E-U NSSO

2001 HS

2002 HS

2003 HS

2004 HS

2005 HS E-U NSSO

2006 HS

2007 HS LFS

2008 HS

2009 HS

2010 LFS LFS

2011 LFS LFS

2012 LFS E-U NSSO LFS

2013 LFS LFS

2014 LFS LFS

2015 LFS LFS

2016 LFS HS LFS

2017 LFS LFS

2018 LFS LFS LFS

Monthly Quarterly 3rd quarter 1st quarter

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

19

Appendix B. Regression results, returns to schooling

TABLE B.1 RETURN TO SCHOOLING (% CHANGE) FOR SELF-EMPLOYED IN THE COFFEE SECTOR

Costa Rica (default=0) No education (default=0)

Ethiopia -619.1*** Primary/lower secondary 36.2***

India -90.5*** Upper secondary 56.7***

Indonesia -242.3*** Tertiar y 89.6***

Viet Nam -45.0***

Observations 48,760

Adjusted R2 0.3451

Source: Harmonized household and labour force surveys of the relevant countries and author's own calculations, all years avail-

able.

Notes: Earnings are measured in $USD 2020. The logarithm of monthly earnings is the dependent variable. The population

includes employers and own-account workers. Signicance, *** at 1%, ** at 5%, * at 10%.

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

20

Appendix C. Coffee seasonality

TABLE C.1 HARVEST SEASON BY COUNTRY, COFFEE SECTOR

17

Costa Rica October - December

Ethiopia October - December

India January - March

Viet Nam January - March

Indonesia, Sumatra November - January

Indonesia, Java July-September

17 See https://www.ptscoee.com/blogs/news/coee-seasonality and https://www.expat.or.id/info/coeeinindonesia.html

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

21

Appendix D. Employment and output (only Ethiopia) distribution,

by country

FIGURE D.1 INDIA, COFFEE WORKERS DISTRIBUTION IN 2012

Source: Harmonized labour force survey of India and author's own calculations.

Notes: The map shows the geographical distribution of 411,791 workers in 2012. The borders may not show the latest

administrative changes occurred in India.

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

22

FIGURE D.2 VIET NAM, COFFEE WORKERS DISTRIBUTION IN 2018

Source: Harmonized labour force survey of Viet Nam and author's own calculations.

Notes: The map shows the geographical distribution of 1,439,712 workers in 2018.

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

23

FIGURE D.3 COSTA RICA, COFFEE WORKERS DISTRIBUTION IN 2018

Source: Harmonized labour force survey of Costa Rica and author's own calculations.

Notes: The map shows the geographical distribution of 46,140 workers in 2018. Data is at the socio-economic region

level. The source data for the map is at the canton level and some socio-economic regions cannot be perfectly built

since some cantons are present in two regions (split is at the district level).

Wages and working conditions in the coffee sector: the case of Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam

Background note

24

FIGURE D.4 ETHIOPIA, COFFEE WORKERS DISTRIBUTION IN 2016