Cool Neighborhoods NYC1

The City of New York

Mayor Bill de Blasio

Mayor’s Ofce of Recovery and Resilency

Anthony Shorris, First Deputy Mayor

Mayor’s Ofce of Recovery and Resilency

Anthony Shorris, First Deputy Mayor

The City of New York

Mayor Bill de Blasio

Anthony Shorris

First Deputy Mayor

Cool

Neighborhoods

NYC

A Comprehensive Approach to Keep

Communities Safe in Extreme Heat

Cool

Neighborhoods

NYC

A Comprehensive Approach to Keep

Communities Safe in Extreme Heat

3Cool Neighborhoods NYC

Table of Contents

Letter from the Mayor

Introduction

Cool Neighborhoods NYC Heat Mitigation Strategies

• Conducting Targeted Street Tree Plantings for Cool Neighborhoods

• Strategically Implementing NYC °CoolRoofs

• Understanding the Role that Cool Pavements Play in Addressing the Urban Heat Island Effect

• Implementing Green Infrastructure and Understanding its Co-Benets

Cool Neighborhoods NYC Heat Adaptation Strategies

• Launching Climate Risk Training for Home Health Aides

• Encouraging New Yorkers to Check on At-Risk Neighbors through Be a Buddy NYC

• Building Partnerships with Health and Weather Reporters for Preventative Messaging

• Advocating for Reforms to the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP)

• Working to Improve Ventilation and Ensure Operable Windows in Residential Buildings

• Supporting Improvements to Signage and Programming at Cooling Centers

Cool Neighborhoods NYC Monitoring Strategies

• Collecting Innovative Data to Deliver Inclusive and Health-focused Climate Policy

Looking Forward

Acknowledgements

References

Glossary

5

7

10

11

13

16

18

20

21

23

25

27

29

31

32

33

36

38

40

43

Cool Neighborhoods NYC4

Letter from

the Mayor

5Cool Neighborhoods NYC

Friends,

Climate change is a growing threat to humanity and our city. New Yorkers understand

this. Rising temperatures continue to threaten the health of all New Yorkers, but

particularly older adults, those without access to air conditioning, and those with a

variety of health conditions. Cool Neighborhoods NYC is an innovative citywide effort to

tackle extreme heat, which contributes to more deaths than all other natural disasters

combined.

When it comes to climate change, it is crucial to have partners at all levels of

government and New Yorkers were shocked when the President pulled out of the Paris

Accord. But we are not discouraged. New York City will continue to do all it can to

preserve a livable planet and a resilient city. Nothing that happens in Washington will

change that.

In June, I signed an Executive Order committing New York City to the Paris Agreement

and we will continue to follow OneNYC, our comprehensive roadmap to a resilient,

sustainable and equitable New York. This report outlines an important part of this work.

Our research on New York’s neighborhoods shows that heat-related health risks are

greatest in certain communities, including those without adequate shade protection

from trees and foliage and those with higher rates of poverty. With Cool Neighborhoods

NYC we are addressing rising temperatures by planting trees, coating roofs with

reective paint, and working with residents to ensure they take proper steps to stay

cool and check on each other.

This approach also complements our efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 80

percent by 2050. Over the next several years, we will continue to do our part for our

people and our planet and serve as a model to other cities around the world. Anything

less would be unacceptable.

Mayor Bill de Blasio

Cool Neighborhoods NYC6

Introduction

7Cool Neighborhoods NYC

More Americans die from heat waves every year than from all other extreme weather events combined.

1

Further,

according to the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Aeronautics and Space

Administration’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, 2016 was the hottest year on record globally, making 2016 the

third consecutive year of record-high global average surface temperatures. These higher average temperatures, growing

urban areas—especially their increasing elderly populations—and projections of more intense, frequent, and longer heat

waves make heat an urgent environmental and health challenge.

2

The New York City Panel on Climate Change (NPCC)

projects up to a 5.7°F increase in New York City (NYC) average temperatures and a doubling of the number of days above

90°F by the 2050s.

3

Periods of extreme heat have a profound effect on human health, including dehydration, heat exhaustion, heat-stroke,

and mortality. In New York City, specically, extreme heat is the number one cause of mortality from extreme weather.

4

Every year, NYC experiences an average of 450 heat-related emergency department visits, 150 heat-related hospital

admissions, and 13 heat-stroke deaths. The City also averages about 115 excess deaths from natural causes exacerbated

by extreme heat annually.

5

Heat and rising temperatures threaten NYC’s livability -- a threat that will continue to

increase in the absence of strategies to make our city more heat resilient as our climate changes.

6

New York City, like other urban areas, is more vulnerable to heat than rural and suburban areas. Due to the relative

amount of dark, impervious surfaces, limited vegetation, and dense human activity, cities can be up to 22°F hotter than

rural and suburban areas as part of a phenomenon known as the Urban Heat Island Effect (UHIE). The UHI effect leads

to higher summertime peak energy demand, air conditioning costs, air pollution, and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

7

Aside from rising average temperatures and heat waves, the UHI effect also threatens NYC’s livability and quality of life.

Further, within NYC, some areas and communities

may be more at risk than others. Variation in

NYC’s densely built environment—including the

distribution of our sparse vegetation, building

typologies, and surface materials—results in

disparate neighborhood-level heat risks. These

physical risks overlap with social and health

risk factors, resulting in disproportionate effects

borne by the most vulnerable residents of high-

poverty neighborhoods: older adults, those in poor

health, and those who do not have access to air

conditioning. To help identify NYC’s most heat-

vulnerable neighborhoods, Columbia University

and the NYC Department of Health and Mental

Hygiene (DOHMH) developed a Heat Vulnerability

Index (HVI) that combines metrics proven to be

strong indicators of heat risk through validation

with health data and that describes both social and

physical characteristics.

8

(See Figure 3: DOHMH

HVI map).

The development of the HVI informed the mayoral

charge in the City’s OneNYC plan to mitigate heat

citywide, with a targeted response for the most at-

Figure 1: Some NYC communities experience higher temperatures than others.

Variation in NYC’s densely built environment results in disparate neighborhood-

level risks. Source: LANDSAT Thermal Data, 2009.

NYC Thermal Imagery

Cool Neighborhoods NYC8

risk neighborhoods. As a result, the NYC Mayor’s Ofce of Recovery and Resiliency (ORR)

developed Cool Neighborhoods NYC: a new $106 million program designed to help keep

New Yorkers safe during hot weather, mitigate UHI effect drivers and protect against

the worst impacts of rising temperatures from climate change. This comprehensive

approach expands the Administration’s aggressive climate resiliency agenda.

The rst set of strategies outlined in this report highlights the role that the physical

environment plays in driving local temperatures and describes the City’s investments to

increase shade, greenery, and canopy cover and increase high albedo surfaces in public

and private sites to help lower surface and indoor temperatures in NYC neighborhoods

with high vulnerability to heat-related illnesses and mortality. High temperatures also

threaten New Yorkers inside their homes today and will continue to do so in the future

due to climate change. For this reason the Cool Neighborhoods NYC comprehensive

approach also includes adaptation strategies to keep New Yorkers safe during periods of

extreme heat.

The second set of strategies outlined in this report underscores the critical role that

our most trusted messengers can play in helping us adapt to climate change. The nal

strategy outlined in this report describes key efforts to better understand the scope of

the challenge via data collection and monitoring.

The City is committed to delivering health-protective messages and encourage all New

Yorkers—but especially older adults, the homebound, and those with chronic health

conditions—to take action in caring for themselves and one another during extreme

heat days.

Figure 2: More Americans die from heat waves every year than from all other extreme weather events combined.

Source: NOAA National Weather Service, 2016.

U.S. Fatalities by Hazard, 2006-2015

9Cool Neighborhoods NYC

Through climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies, the City will reduce its

contributions to rising temperatures, combat the UHI effect, and protect its residents

from extreme heat events. Each program initiative is fully funded or budget neutral and

will launch in 2017, with implementation over the next three years through scal year

2021.

Figure 3: Source: DOHMH, 2015.

The HVI is adapted from a study by

researchers at the NYC Department

of Health and Mental Hygiene and

Columbia University who analyzed

mortality data from 2000 to 2011.

The analysis identied factors that

were associated with an increased

risk of deaths during a heat wave.

The map shows NYC Community

Districts ranked from least to most

vulnerable. Each Community District

HVI is the average of all census

tracts in the Community District.

Heat Vulnerability Index (HVI) for New York City Community Districts

Cool Neighborhoods NYC10

Cool

Neighborhoods

NYC

Heat Mitigation

Strategies

11Cool Neighborhoods NYC

Trees and forest vegetation cool directly through shading and indirectly through

evapotranspiration: a process through which water is moved from a plant’s roots to its

leaves where it then evaporates through the small pores on the underside of a leaf.

The liquid water turns to vapor, losing the water molecules’ heat and cooling the plant

and surrounding air.

9

Shaded surfaces may be 20°F to 45°F cooler than unshaded

surfaces; evapotranspiration, either alone or in conjunction with shading, can reduce

peak temperatures by 2°F to 9°F.

10

In addition to outdoor and indoor temperature

reduction via shading and evaporative cooling; street trees and vegetation provide a

number of social and environmental benets. These include reduced enewy use and

related greenhouse gas emissions, improved air quality, increased biodiversity, enhanced

stormwater management, as well as improved quality of life through aesthetics, improved

mental wellbeing, and noise reduction.

11,12,13

Improving NYC’s resiliency to climate-mediated increases in urban heat will require

signicant and ongoing investments in green and natural infrastructure strategies. In

2007, the City launched its Million TreesNYC program, which planted its millionth new tree

in 2015, two years ahead of schedule, and became a renowned greening model for cities

across the world. To harness the cooling and ancillary benets of urban vegetation, the

City has committed an additional $82 million dollars to fund street tree plantings that

will prioritize areas that are disproportionately vulnerable to heat risks, as shown in the

City’s Heat Vulnerability Index: neighborhoods in the South Bronx, Northern Manhattan,

and Central Brooklyn (see Figure 3). Tree plantings will also be targeted in other areas of

the city with low levels of tree canopy cover and open space; limited shade; and building

and landscape characteristics that contribute to heat stress. This targeted tree planting

is possible based on the City’s highly accurate street tree census completed in 2016

and also based on the work of our academic partners at The New School and the State

University of New York

(SUNY) at Buffalo.

In the coming years the City

will also invest $16 million

to support planting trees

in parks, where we need to

plan for the next generation

of specimen trees as our

largest trees, providing the

greatest environmental

benets, are reaching

maturity. An additional $7

million investment will

support forest restoration

across the ve boroughs--

Figure 4: In addition to temperature reduction via shading and

evaporative cooling; street trees and vegetation provide many social

and environmental benets. Source: OneNYC.

Targeted tree planting

strategy and implementation

conducted by:

NYC Department of Parks

and Recreation

NYC Mayor’s Ofce of

Recovery and Resiliency

NYC Department of

Health and Mental

Hygiene

Natural Areas

Conservancy

Urban Systems Lab at

The New School

The State University of

New York at Buffalo

Conducting Targeted Street Tree Plantings

for Cool Neighborhoods

Cool Neighborhoods NYC12

where the city’s densest stands exist and are tireless factories of clean air production.

Our tree planting efforts will begin in the fall of 2017 and take place through 2021.

This work would not be possible without the tireless efforts of the staff at the NYC

Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR), who manage and maintain our natural

resources. For this reason, additional staff has been funded to help the City and its

partners implement this vision of a resilient and diverse tree canopy and natural habitats

in New York City. This comprehensive and proactive approach is possible thanks to our

partnership with the Natural Areas Conservancy (NAC)--a champion of New York City’s

more than 20,000 acres of forests and wetlands for the benet and enjoyment of all.

Green space is not equitably distributed across the city and some of the most vulnerable

populations may not have adequate access to cool or green spaces where they can escape

high and extreme heat.

14

Linking vulnerable and high-risk populations to strategies for

green infrastructure and other nature-based solutions is critical for increasing equity

and addressing environmental justice in the city. Increasing the city’s street tree canopy

will reduce the UHIE, relieve heat stress in residential neighborhoods, help to improve

air quality, and support the city’s biodiversity by creating additional corridors of greenery

that help connect between larger patches of vegetation, giving local species access to a

greater amount of habitat.

15

Finally, moving forward, the City will continue to partner with

local organizations and communities to support and foster tree stewardship initiatives

and to engage and empower volunteers in our neighborhoods.

Planting trees will help us meet the City’s commitments in OneNYC to “mitigate the

impacts of the urban heat island effect” and green the city’s streets, parks, and open

spaces, while exemplifying how to incorporate a health-based and environmental justice

framework into environmental and natural resource planning and strategy development.

Figure 5: Street trees provide

shade, support biodiversity, and

enhance the quality of life of

New Yorkers. Corner of Post Ave.

and Academy St. in Manhattan.

Source: NYC DPR.

2008

2009

2016

13Cool Neighborhoods NYC

Impervious surfaces, such as asphalt roads and roofs, contribute to the UHI effect by

absorbing and reradiating heat, especially at night.

16

Green roofs or vegetation—covered

roof surfaces—benet property owners in numerous ways. They can improve quality of

life through noise reduction; increase property values; and beautify a property for owners

and neighbors. While their up-front installation costs are high, green roofs reduce energy

and maintenance costs by protecting rooftops and building equipment from excessive

sun exposure during warmer seasons and increase heat retention during cooler seasons.

Given these benets, the City sought to incentivize the implementation of green roofs

as replacements for dark roofs in the city. In 2008, the City of New York and New York

State passed legislation to provide a one-year tax abatement, or tax relief, of $4.50 per

square foot (up to $100,000 or the building’s tax liability, whichever is less). Amended

in 2013, the tax abatement is

now available through March

15, 2018.

17

In addition to action

on green roofs, the City has

also funded and implemented

“cool roofs,” which are lighter

in color and reect heat.

Cool roofs transfer less heat

into buildings and in turn

help reduce building energy

consumption and waste-heat

from air conditioning use.

18

Additionally, due to their

high reectivity, clusters of

light-colored surfaces reduce

ambient air temperatures,

thereby mitigating the UHI

effect.

19

Based on this evidence, in 2009, the City launched NYC °CoolRoofs, a program that set a

goal to coat one million square feet of rooftops each calendar year with white paint. The

City of New York has since invested over $4 million dollars in the NYC CoolRoofs program

and has coated more than 6.7 million square feet of rooftop space to-date, contributing

to lower cooling costs and reducing an estimated 2,680 metric tons of carbon dioxide

equivalent (tCO2e) emissions in the city (See Figure 7).

The program supports the City’s goal to reduce carbon emissions 80% before 2050

(80x50), as outlined in Mayor de Blasio’s One New York: The Plan for a Strong and Just

City. Through this program, the City also provides local job-seekers with ten weeks of

Figure 6: The NYC Cool Roofs program helps thousands of New

Yorkers reduce their energy use and will help address the city’s

urban heat island effect by coating millions of square feet of roof

area. By 2025, this is expected to reduce citywide GHG emissions by

3,500 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent, generate $1 million

in annual energy cost savings, and train 500 New Yorkers who will be

prepared for jobs promoting energy efciency in buildings. Source:

Dana Ullman for UNHP.

°Cool Roof targeted out-

reach, workforce training

and implementation

conducted by:

NYC Department of

Small Business Services

Sustainable South

Bronx (a division of the

HOPE Program).

NYC Mayor’s Ofce of

Recovery and Resiliency

Fordham University

Strategically Implementing NYC °CoolRoofs

Cool Neighborhoods NYC14

traini ng and work experience installing the energy-saving reective rooftops. The City

hires 70 workforce participants per year and connects them to permanent employment

opportunities upon completion of their training. This initiative is a partnership between

the NYC Department of Small Business Services (SBS), the NYC Mayor’s Ofce of

Sustainability (MOS), the NYC Mayor’s Ofce of Recovery and Resiliency, and Sustainable

South Bronx, a division of the HOPE Program.

20,21

Cool roof installations are provided at no-cost to non-prots, affordable and supportive

housing organizations, select cooperatively-owned housing, and select organizations

providing public, cultural, and/or community services. Technical assistance and low-cost

installation options are also available for other privately owned buildings. By installing

a cool roof, a building can lower air conditioning costs by 10% to 30%; achieve up to

30% reduction in internal building temperatures during the summer with negligible

impact to heating costs in the winter; increase the longevity of roof and building cooling

equipment; and improve the comfort of building residents and tenants.

While the program has had incredible success, we can better target roof coatings to

the neighborhoods that need it the most. In response, the City, together with Columbia

University, developed a two-year strategic plan to understand how this program could best

contribute to urban heat island mitigation in neighborhoods with high heat vulnerability.

Using the City’s Heat Vulnerability Index (HVI), the study determined geographic areas

of focus, assessed the potential to cluster the implementation of roofs, identied and

prioritized potential program participants, developed outreach and communication

strategies to secure the participation of target building owners, and developed tools to

assist owners in understanding the benets of the program for their own buildings. As a

result, the study identied a priority list of 2.7 million square feet of potential private and

public buildings to conduct strategic outreach to owners in the heat-vulnerable areas of

the Bronx, Central Brooklyn, and Northern Manhattan (See Figure 8). The NYC °CoolRoofs

Strategic Implementation Plan will launch in 2017 to improve the impact of this existing

City program by concentrating $2.6 million dollars’ worth of new projects to mitigating

the UHI effect in heat-vulnerable neighborhoods through scal year 2020.

However, we know we cannot achieve our goals without the help of partners from the

private sector. To put this plan into action, in 2017 Fordham University will partner

with the City on UHI effect mitigation by becoming a participant in the NYC °CoolRoofs

program. Fordham is located in Bronx neighborhoods with high heat vulnerability and

is also a participant in the NYC Carbon Challenge, pledging to voluntarily reduce their

building-based emissions by 30% or more over the course of ten years. Together, we

will coat 6 buildings, resulting in 81,000 square feet of new cool roofs in the Bronx. In

addition, the plan focuses on strategic partnerships and enhanced outreach to a mix

of buildings (publicly and privately owned, and those serving a non-prot, affordable

housing or social service function) to improve public awareness and increase the

program’s visibility—key tactics as the City seeks to deliver inclusive climate action.

Pavement choices can have a signicant impact on pedestrian thermal comfort in urban

areas. Dark-colored asphalt pavements in streets, which can encompass up to 40% of the

15Cool Neighborhoods NYC

Figure 7: The City has coated more than 6.7 million sq. ft. of rooftop space to-date. Source:

Columbia University Master of Science in Sustainability Management Capstone Project, 2016.

Figure 8: The Cool Roofs study identied a priority list of 2.7 million square feet of potential

private and public buildings to conduct strategic outreach to owners in the heat-vulnerable areas

of the Bronx, Central Brooklyn, and Northern Manhattan. Source: Columbia University Master of

Science in Sustainability Management Capstone Project, 2016.

Existing NYC °CoolRoofs

Recommended NYC °CoolRoofs

Cool Neighborhoods NYC16

surface area in cities, contribute to the UHI effect. Similar

to dark roofs, asphalt pavements re-radiate absorbed

heat into the atmosphere, especially at night. In contrast,

“cool pavements” are generally light-colored pavements

with a high albedo (over 0.29) that reect more of the

sun’s radiation than a dark-colored pavement with low

albedo.

22

Newly installed concrete pavement has an

albedo of around 0.35 while fresh asphalt is typically

closer to an albedo of 0.05-0.10.

City simulations, using weather data from several U.S.

cities, have found that reective pavements, when used

in conjunction with cool roofs and shade tree planting,

can lower ambient air temperatures, on average by 4°F

to 9°F.

23,24

Furthermore, it has been posited that cool

pavements with high albedo surfaces can have longer

durability because of their lowered temperatures, and can

decrease stress on street trees, increasing their vitality,

and thus increasing the benets they afford.

25

While many NYC streets are paved with asphalt due to

other environmental and engineering considerations,

fortunately, over 90% of the city’s sidewalks are light

colored. Some NYC sidewalks include permeable

interlocking concrete pavers (PICP) and precast porous

concrete panels which may reduce the UHI effect through

evaporative cooling.

26

Adding trees and ecological

features to sidewalks and streets also contribute to

improved health, as they provide safe and green corridors

where people want to be, walk and exercise.

Finally, vibrant sidewalks can encourage people to support

local businesses with active storefronts and streetscapes

and can promote opportunities for neighborhood

cohesion and interactions and community building.

NYC Greenstreets, green infrastructure projects, planted

public spaces, medians, and trafc islands help with these

environmental and social benets and also help reduce

the UHI effect by promoting evapotranspiration and

increasing reectivity.

Between 2007 and 2016, the NYC Department of

Transportation (DOT) Trafc and Planning team has

converted a substantial portion of the dark asphalt

Figure 9: Cool pavements reect more of the sun’s radiation than a

dark-colored pavement. Sand-colored concrete sidewalk on Prospect

Park West, Brooklyn. Source: NYC DOT.

Figure 10: Adding trees, lighter surfaces and ecological features to

sidewalks and streets also contribute to improved health, as they

provide safe and green corridors where people want to be, walk and

exercise. Prospect Park Bike Lane, Brooklyn. Source: NYC DOT.

Understanding the Role that Cool Pavements Play in

Addressing the Urban Heat Island Effect

17Cool Neighborhoods NYC

curb where street trees, signs, above-ground utilities, and

street furniture are typically located. Through the DOT

Vision Zero Great Streets projects, the City is also adding

close to 360,000 square feet of new planted space across

Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx.

This increases the permeable area within projects and

reduces the overall coverage of heat-absorbing asphalt

and/or concrete. As the DOT Capital program’s Pedestrian

Safety and School Safety projects, Vision Zero Great Streets

projects, greenway projects, and similar efforts grow, the

City will continue to convert more and more dark asphalt

roadway to lighter concrete and planted spaces.

Aside from light-colored concrete sidewalks and pilot

programs of other reective and permeable pavements,

real-world, empirically-backed studies specic to

UHI effect mitigation are lacking and the large-scale

application of cool pavements has no urban precedent.

Because of this, the safety, durability, longevity, and

upkeep maintenance costs for implementation are

relatively unknown and will be a challenge as the City

leads this innovative effort.

27

Increasing the reectivity, porosity, and planted

groundcover of the city’s pavement surfaces have the

potential to be important tools that the City can use

to mitigate the UHI effect. Going forward, the City will

assess the feasibility of increasing cool and permeable

surfaces in heat-vulnerable neighborhoods and will

continue to determine interventions that make sense for

certain typologies (plazas, playgrounds, parking lots, low-

trafc roads, etc.).

Figure 11: The City will continue to convert more and more dark asphalt

roadway to lighter concrete and planted spaces. Junior High School 185,

Flushing, Queens. Source: NYC DEP.

roadbed (over 3 million square feet) to lighter-colored

and/or planted spaces.

In addition, DOT works with the New York City Department

of Environmental Protection (DEP) on permeable or

porous pavements to facilitate stormwater management

where appropriate. Permeable, or porous pavements

cool via evapotranspiration from water and air passing

through the pavement. DOT is updating their Street

Design Manual that will encourage the continued use

of permeable pavements, where appropriate, by private

entities.

The Public Design Commission has also approved the use

of permeable pavers in the furnishing zone of sidewalks

citywide by private entities. The furnishing zone is the

area of the sidewalk that is immediately adjacent to the

Assessment of UHI effect mitigation opportunities in

heat-vulnerable neighborhoods will be conducted by:

NYC Mayor’s Ofce of Recovery and Resiliency

NYC Department of Transportation

NYC Department of City Planning

NYC Department of Environmental Protection

Cool Neighborhoods NYC18

Since 2011, the NYC Department of Environmental

Protection (DEP) has been implementing green

infrastructure (GI) practices in combined sewer areas

citywide in an effort to manage stormwater. To-date,

NYC DEP has installed thousands of green infrastructure

practices in the public right-of-way (ROW), replacing

sections of sidewalk with rain gardens that include a mix

of trees, owers, shrubs and grasses. NYC DEP also works

with partner agencies and non-prot organizations to

retrot public properties with larger green infrastructure

practices. NYC DEP is also incentivizing green

infrastructure retrots on private property through the

Green Infrastructure Grant Program.

NYC DEP continues to progress in development of its

Green Infrastructure Program as part of a $1.5 billion by

2030 commitment. As of March 2017, the Program had

encumbered over $410 million with another $1 billion

budgeted over the next 10 years for thousands more GI

practices including rain gardens, permeable pavement,

and subsurface storage.

28,29

Many of the combined sewer areas that have received

or will receive green infrastructure are also in HVI

neighborhoods, including central Brooklyn, areas of

the south Bronx, and areas of northwest and southeast

Queens (See Figure 13). Although the primary goal of the

GI Program is to capture stormwater, GI has co-benets

beyond stormwater capture. These co-benets include

how rain gardens and green roofs mitigate the UHI effect

through added shade and evapotranspiration. NYC DEP

has been working on research and development efforts

to understand co-benets of green infrastructure. NYC

DEP will continue data collection efforts to investigate

the co-benets of widespread green infrastructure

implementation.

Figure 12: Green Infrastructure has

co-benets beyond stormwater

capture, including creating urban

habitat and mitigating the UHI

effect through added shade and

evapotranspiration. Bioswales,

Brooklyn. Source: NYC DEP.

Green Infrastructure

implementation led by

NYC DEP in partnership

with:

NYC Department of

Parks and Recreation

NYC Department of

Transportation

NYC Department of

Education

NYC Department

of Design and

Construction

NYC Economic

Development

Corporation

NYC Department

of Design and

Construction

NYC Housing Authority

School Construction

Authority

The Trust for Public

Land

Implementing Green Infrastructure and Understanding

its Co-Benets

19Cool Neighborhoods NYC

Figure 13: NYC DEP has installed thousands of green infrastructure practices in the public right-of-way replacing sections

of sidewalk with rain gardens. Many of the combined sewer areas that have received or will receive green infrastructure are

also in HVI neighborhoods. Source: NYC DEP, 2017.

Green Infrastructure Program Area-Wide Contracts

Cool Neighborhoods NYC20

Cool

Neighborhoods

NYC

Heat Adaptation

Strategies

21Cool Neighborhoods NYC

Launching Climate Risk Training for Home

Health Aides

Hot and humid summer weather can cause heat illness and even death. In New York

City, DOHMH examined death records from 2008-2011 and found that about 85% of NYC

heat-stroke deaths happened after exposure to heat inside the home. Many victims were

exposed to heat inside homes that lacked access to or did not use air conditioning.

30,31

Older adults, those who are obese, those with chronic medical conditions or mental

health conditions, those who abuse drugs or alcohol, and certain other groups are most

vulnerable. Those who are socially isolated or homebound are also at risk. There are place-

based risk factors such as poor access to public transportation or cooling centers.

32,33,34

Cooling centers are open across the city during serious heat waves. However, published

studies and City data suggest that many New Yorkers, including those most vulnerable

to heat illness, prefer to stay at home during hot weather even if they cannot stay cool

there, instead of visiting a cool place like a library, a friend’s home with air conditioning,

or a city cooling center.

35

Remaining in their homes is dangerous for their health.

Due to current and future risks in light of our changing climate, the City needs strategies

to reach heat-vulnerable populations inside their homes. Studies show that indoor

home temperatures can be 20°F higher than outdoor temperatures in the absence of air

conditioning, and that indoor exposures to heat exceed the comfort range among elderly

occupants.

36

As outlined in OneNYC, the City assessed the feasibility of establishing a citywide

maximum allowable indoor temperature in residential facilities and supportive housing

for vulnerable populations.

37

Interviews with providers, survey feedback from community

members, and brainstorming with sister cities facing similar climate risks revealed that the

establishment of a maximum indoor temperature would pose signicant challenges and

requires further examination.

Nevertheless, Home Health

Aides (HHAs) play a critical

role in protecting our city’s

most vulnerable residents

by providing critical health

services inside their homes

and are important partners in

the City’s efforts to protect at-

risk New Yorkers.

Figure 14: Home Health Aides can communicate climate-related health

risks and promote protective measures inside the home. Source: Stock

Photo.

Planning and

development of Home

Health Aide climate

and heat risk training

conducted by:

New York Alliance for

Careers in Healthcare

at NYC Department of

Small Business Services

NYC Department of

Health and Mental

Hygiene

NYC Mayor’s Ofce of

Recovery and Resiliency

NYC Emergency

Management

Sunnyside Community

Services

Allen Health Care

Services

Best Choice Home

Health Care, A Member

of the Centerlight

Health System

Cool Neighborhoods NYC22

Due to established relationships between aides and clients, HHAs can be trusted

messengers in communicating health risks and promoting protective measures inside

the home.

Starting in 2017, the City will partner with homecare agencies to promote heat-health

messages to New Yorkers and engage HHAs as key players in building climate resiliency.

To this end, the City developed a heat-health module for continuing education trainers

that will be offered as part of the standard curriculum by three key homecare employers.

Through these employers, our continuing education curriculum aims to reach nearly

8,000 HHAs, who will be trained to identify clients that are at highest risk, understand

that medicines can affect the body’s ability to respond to heat, and understand ways to

prevent heat-related illness and death. Most importantly, HHAs will learn to identify

barriers that prevent their clients from staying cool and can connect the most vulnerable

New Yorkers to the array of services offered by City government.

Offering this training on an ongoing basis will also build a much-needed knowledge

base in our communities as HHAs will have a better understanding of climate risks and

can act on that knowledge to protect their own families, friends and neighbors during

periods of very hot weather.

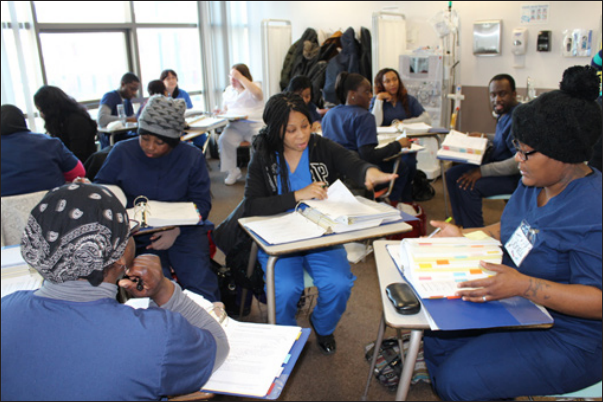

Figure 15: During the heat-health module, HHAs will learn to identify barriers that prevent

their clients from staying cool and can connect them to the array of services offered by

City government. Source: NYC SBS.

23Cool Neighborhoods NYC

A key challenge in preparing for extreme weather emergencies is their relative

unpredictability. To protect New Yorkers in the future, lessons can be learned from

strategies tested and evaluated from more common climate emergencies such as heat

waves. A heat emergency is not the time to identify vulnerable residents. Rather, it is

important to build social networks that can help share life-saving information prior

to such an emergency, and can reach out to at-risk neighbors during an extreme heat

event. Studies have shown that enhanced social cohesion better prepares communities

to withstand natural disasters and their health impacts.

38

The City is investing $930,000 to launch Be a Buddy NYC to create a community-led

preparedness model that promotes social cohesion. This health-based initiative is a

two-year pilot that will promote community resiliency to extreme heat and other

weather emergencies in key heat-vulnerable communities (See Figure 16). South Bronx

neighborhoods, including Highbridge-Morrisania, Crotonia-Tremont, and Hunts Point-

Mott Haven, have among the highest rates of heat illness and death in NYC. Central

Brooklyn and Central and East Harlem are also highly vulnerable to heat impacts. The

City’s Neighborhood Health Action Centers will serve as incubators for community

preparedness.

Development and

implementation of

Be a Buddy NYC is a

partnership between:

NYC Department of

Health and Mental

Hygiene

NYC Mayor’s Ofce of

Recovery and Resiliency

NYC Emergency

Management

Figure 16: Be a Buddy NYC is a two-year pilot that will promote community resiliency to extreme heat and

other weather emergencies in key heat-vulnerable communities. Source: NYC DOHMH, 2015.

Encouraging New Yorkers to Check on At-Risk

Neighbors through Be a Buddy NYC

Cool Neighborhoods NYC24

Be a Buddy NYC is an interagency partnership to address heat-related health impacts

by enhancing the response capacity, climate preparedness and communication tools

of local community-based organizations, while increasing neighborhood volunteerism

through the creation of buddy systems. The City will work with each neighborhood to

foster buddy systems between social service and community organizations, volunteers,

and vulnerable New Yorkers, to be deployed during emergencies to conduct telephone

and, if necessary, door-to-door and building level checks on vulnerable individuals.

Over the next two years Be a Buddy NYC will implement protective measures against heat-

related illnesses by: (1) training community organizations and volunteers on emergency

protective measures and ways to assist vulnerable adults; and (2) engaging communities

to identify alternative neighborhood resources for staying cool and to communicate

protective health messages to hard-to-reach populations via trusted messengers. Be a

Buddy NYC leverages and models other citywide initiatives including Age-Friendly NYC,

Community Emergency Response Teams, NYC Service, and the Neighborhood Health

Action Centers.

Figure 17: Resident door

knocking at Queensbridge

Houses. The City will work with

neighborhoods to foster buddy

systems between community

organizations, and vulnerable

New Yorkers. Source: Edwin J.

Torres/Mayoral Photography

Ofce.

25Cool Neighborhoods NYC

Studies show that residents of the United States may not always perceive climate change

as a health threat, despite the fact that

several risks, including an increased

likelihood of heat stroke due to rising

temperatures and higher frequency

and intensity of heatwaves, are well

understood and documented.

39

For

this reason, articulating the health

impacts of extreme weather events

accurately and effectively to the

communities that are most affected

is crucial. In New York City, most heat-

related fatalities occur from exposure

to heat in homes without working

air conditioning, and the victims are

often older adults and people with

chronic health conditions or other health or place-based risk factors. A citywide survey

conducted in 2011 found that among older adults, and adults aged 18-64 who reported

being in poor or fair health and who did not own or rarely used air conditioning, almost

50% stayed home during hot weather and 30% were unaware of heat warnings. Focus

groups conducted in 2012 found that older adults who participated did not perceive

themselves to be at risk during very hot weather, and did not consider air conditioning

use as an important preventive measure.

After learning this key health message, they noted that the importance of air conditioning

use was missing from local news clips shown to the group about extreme heat. Rather

than portraying older adults and potentially dangerous indoor environments, T.V. images

and voiceovers broadcasted during extreme heat days tended to portray children and

younger adults in outdoor locations.

40

In short, current media coverage of extreme heat

may not effectively convey heat risk to the city’s most vulnerable residents or focus

on indoor exposure. Focus group participants also said that meteorologists and health

reporters are trusted sources of heat-health information. Hence, reporters are in a

powerful position to communicate accurate and life-saving heat-related information to

New Yorkers. Both traditional and social media can play a strong role in promoting health

and safety during heat emergencies. Collaboration between the City and broadcast

media can increase awareness, clarify populations most at risk, and amplify the reach of

public health messages.

Figure 18: Images of outdoor environments, such as beaches,

are typically used by the media during extreme heat events.

Most heat-related fatalities, however, occur indoors. Source:

Orchard Beach in the Bronx. Michael Appleton/Mayoral

Photography Ofce.

Planning and

implementation of

heat-health outreach

conducted by:

NYC Mayor’s Ofce of

Recovery and Resiliency

NYC Emergency

Management

NYC Department of

Health and Mental

Hygiene

Building Partnerships with Health and Weather

Reporters for Preventative Messaging

Cool Neighborhoods NYC26

To ensure that New Yorkers receive information about extreme heat and the protective actions

they need to take, the City will engage health and medical reporters and meteorologists

over the next year to provide information on the health impacts of heat and tips on what

individuals, particularly those most vulnerable and their caregivers and social contacts, need

to know to stay safe. DOHMH will also post information about heat disparities in NYC’s

neighborhoods, including a Heat Vulnerability Index and information about air conditioning

prevalence by neighborhood, on its website.

Figure 19: T.V. images and voiceovers broadcasted during extreme heat days tend to portray children and

younger adults in outdoor locations rather than portraying older adults and potentially dangerous indoor

environments. Source: NYC DEP.

27Cool Neighborhoods NYC

Air conditioning is the most effective and important way to protect at-risk individuals

on hot days and to keep them from experiencing heat-related illnesses. In NYC, a

critical climate adaptation strategy is to ensure that vulnerable populations have

access to air conditioning during extreme heat days. However, cost is a barrier for low-

income populations, making access to air conditioning a serious health-equity issue.

New Yorkers can obtain some nancial relief through the Low-Income Home Energy

Assistance Program (LIHEAP), which is administered by the U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services and provides subsidies to low-income households to assist in paying for

heating and cooling needs. In 2016 alone, the LIHEAP program distributed over 700,000

heating and cooling grants ($37.5 million) in NYC. LIHEAP’s cooling assistance, however,

is extremely limited in New York State because the majority of the funding is allocated in

the winter months to help meet the heating needs of low-income New Yorkers.

In New York State, 65% of LIHEAP funding is allocated to heating assistance, while only

1% is allocated for cooling assistance (with the remainder going to fund crisis assistance,

weatherization, and administration costs).

41

When LIHEAP is available for cooling, the

assistance applies solely for the purchase and installation of an air conditioning unit for

low-income residents with a documented medical need, but the assistance grant cannot

be used to offset prohibitive utility costs.

Low-income individuals, particularly those unable to purchase or pay to run air

conditioning during very hot weather, are at increased risk for heat illness. In 2014,

94% of NYC households in low-poverty neighborhoods had access to home air

conditioning, compared with only 82% in high-poverty neighborhoods. Only 70% of

households in Brownsville, one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods, had air conditioning

coverage compared to 99% of households in South Shore, one of the city’s wealthiest

neighborhoods.

42

Support of changes in

LIHEAP distribution and

increased funding will be

conducted by:

NYC Mayor’s Ofce of

Recovery and Resiliency

NYC Department of

Health and Mental

Hygiene

NYC Human Resources

Administration

Advocating for Reforms to the Low-Income Home

Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP)

Cool Neighborhoods NYC28

Two surveys of NYC residents found that the primary reason New Yorkers cite for not

owning an air conditioner is cost.

43,44

Even when people own air conditioning, they

may not run it during hot

weather because of utility

cost concerns.

45

Many

New Yorkers do not realize

that setting their air

conditioner at 78°F or “low

cool” on a hot summer day

is the best way to stay safe

and comfortable, while

saving money on their

energy bill. Fans alone

do not keep at-risk people

cool during extremely hot

days. In fact, improper use

of fans, such as using them

when all the windows are

closed, can be dangerous

to health.

By providing air conditioners and offsetting utility costs, LIHEAP has the potential to

reduce heat-related risks for a large number of vulnerable New Yorkers. In its current

state, the program is greatly underfunded when it comes to cooling funds and is

ineffective at meeting the needs of the most heat-vulnerable communities.

In response, the City will work with health departments and other stakeholders across

New York State to support an expansion of LIHEAP to assist qualied households in

paying utility bills related to the operation of air conditioners. The City will also continue

its advocacy for adequate LIHEAP funding at the federal level. As our climate continues

to warm, expansion of the LIHEAP cooling assistance component is vitally needed to

protect vulnerable New Yorkers from both current and future health risks.

Figure 20: Air conditioning is the most effective and important way to

protect at-risk individuals on hot days and prevent heat-related illnesses.

Source: NYCEM.

29Cool Neighborhoods NYC

Beyond individual vulnerability, the condition of urban microclimates, inuenced by

the built environment, affects health risk.

46, 47, 48

Multifamily buildings in urban areas

are particularly vulnerable due to their building age, construction materials, insulation,

roof and wall colors, window orientation, apartment conguration, and lack of operable

windows.

49

Studies have found that these and other building characteristics, including

a lack of central air conditioning systems, low building height, and those made with

exterior building construction consisting of asphalt and wood siding have high heat

sensitivity to outdoor temperatures and solar radiation.

50

The City continues to explore potential building-level interventions to alleviate hot

weather conditions in New Yorkers’ homes. While air conditioning is the optimal solution

for alleviating risks for vulnerable populations, particularly during a heat wave, some

city buildings may not be able to accommodate the electrical loads required to provide

cooling to all units that need it, depending on the age and condition of a building’s

wiring.

Operable windows that enable natural ventilation and passive cooling without electricity,

can provide relief when outdoor temperatures are moderate and are especially important

for ventilation during power outages.

51

Operable windows can be an efcient way to

provide fresh air and can substantially reduce energy use, especially during spring and

fall when local temperature and humidity are lower. In homes where air conditioning

is not used or not available, operable windows can be a New Yorker’s main source of

temperature control.

52

Historically, windows have provided passive ventilation around the world. NYC passed

crucial legislation in 1901 to ensure that all apartments had access to fresh air and

natural light. With this increased ventilation came risk of children falling from windows,

so the City created a

rule that has prevented

hundreds of child

deaths. Owners,

including landlords, are

required in apartments

with a child younger

than 11 years to either

properly install window

guards or place a stop

to prevent windows

from opening beyond

Strategy development

and outreach to

maximize safe natural

ventilation through

windows will be

conducted by:

NYC Mayor’s Ofce of

Recovery and Resiliency

NYC Department of

Health and Mental

Hygiene

NYC Department of

Buildings

Figure 21: Operable windows can be an efcient way to provide fresh air and

can substantially reduce energy use. Source: DTFA.

Working to Improve Ventilation and Ensure Operable

Windows in Residential Buildings

Cool Neighborhoods NYC30

4.5 inches.

53

Although tenants or owners of apartments without children younger than

11 may request the removal of guards or stops, some may not due to landlord concerns

about legal liability or lack of awareness about the law’s requirements.

In response, the City will engage relevant stakeholders to educate on the policy that

protects young children from falls, while pursuing strategies for better compliance with

the code to maximize safe window usage for passive ventilation in homes. Possible

approaches may include discussions with architects and contractors about new and

renovation window designs that meet requirements without being overly restrictive and

posting information that educates tenants and landlords on the rules to promote the

removal of window guards or stops when safe to do so.

31Cool Neighborhoods NYC

Supporting Improvements to Signage and Programming

at Cooling Centers

During heat emergencies, NYC Emergency Management (NYCEM) deploys a multi-

agency response to protect public health, including communication strategies around

staying safe during heat waves and publicizing the opening of hundreds of cooling

centers in order to provide respite from the summer heat. Cooling centers are air-

conditioned spaces that are open to the public for free and become activated during

heat emergencies in NYC. Typically, the facilities designated as cooling centers already

serve as community spaces and include senior centers, community rooms in public

housing buildings, and public libraries. Cooling centers serve New Yorkers that do

not have access to an air conditioner to help prevent heat-related illness or death.

Many of them operate with extended hours to protect at-risk individuals on very hot

days. However, the majority of these spaces are not owned, maintained, or operated by City government. While cooling

centers are publicized through media, public messaging and 311, the City is drastically limited in its ability to implement

any potential capital improvements of these spaces. The facilities volunteer to serve as cooling centers, and physical

inspections and upgrades to the buildings in which the facilities operate are outside of the City’s purview during each

heat emergency.

The City makes efforts to ensure that enough cooling centers are open citywide to meet demand. Nevertheless, published

research shows that many New Yorkers do not want to leave their homes to attend cooling centers even when it is

dangerously hot inside their own apartments. This is why we are using a multi-pronged strategy to tackle the issue,

using Home Health Aides training and Be a Buddy NYC to target New Yorkers that choose to stay in their homes, as well

as increasing the visibility of cooling centers so that they can continue to be a resource for New Yorkers who need them.

To this end, NYCEM will invest in improved signage so that the location of cooling centers will be more accessible to

vulnerable New Yorkers. Signage improvements will launch in summer of 2017. Each cooling center will display a 24”

x 36” vinyl sign at their main entrance to notify the community that the facility is being used as a cooling center during

heat emergencies. The cooling center nder on the NYCEM website will also be updated

to be responsive to screen size on mobile devices.

Through its Age-Friendly NYC initiative, the City is working to foster opportunities for

older New Yorkers to live healthier and more socially connected lives. In 2017, NYCEM

launched the Community Emergency Planning Toolkit, which included outreach to aging

service providers throughout New York City. Starting in summer 2017, the Department

for the Aging (DFTA) in partnership with NYCEM and DOHMH will launch an extreme

heat awareness campaign.

The campaign will center on local outreach and print ads that feature older adults and

will highlight heat safety tips. In addition, DFTA, in their 2017 Age Friendly NYC report,

included recommendations to ensure that senior center participants have information on

services available during extreme heat events, access to the Low Income Home Energy

Assistance Program, and ways to protect themselves during the summer season.

Implementing improved

signage and coordination

with cooling centers will

be conducted by:

NYC Emergency

Management

NYC Department for the

Aging

Figure 22: The Community

Emergency Planning Toolkit is

a New York City-specic guide

for emergency planning. Source:

NYCEM

Cool Neighborhoods NYC32

Cool

Neighborhoods

NYC Monitoring

Strategies

33Cool Neighborhoods NYC

The spatial variation within New York City’s densely built environment—including the

distribution of its vegetation, varied building and other land cover typologies, and

surface materials—results in differentiated heat risk at the local level. Studies have

shown that certain landscape classes are key drivers of surface temperature in cities.

54

When certain landscape classes are compared with geographic patterns of social

risk, they often overlap with disadvantaged neighborhoods. As a result, the effects of

extreme heat are disproportionately borne by many of the most vulnerable New Yorkers.

Temperature monitoring is a crucial component of effectively targeting heat mitigation

and adaptation strategies around the city.

To better understand the geography of NYC’s microclimates and differentiated

vulnerability, the City is investing $300,000 to collect baseline neighborhood-level

temperature information. This will be used to assess current risk, more effectively target

new initiatives in the most heat-vulnerable neighborhoods, and in the long-term, provide

baseline data to accurately measure the impact of interventions. Over the next two

years, this data collection and analysis will empower the City to inform and target future

capital investments in natural infrastructure; to identify operational and policy strategies

that address and adapt NYC to the increasing impacts of UHI effect and extreme heat.

Finally, this work will allow us to identify the need for additional monitoring and research

initiatives that can improve our knowledge of temperature variation and model the

effectiveness of needed interventions.

The City is also engaged in the ve-year, ten-city, National Science Foundation funded

Urban Resilience to Weather-related Extreme Events Sustainability Research Network

(URExSRN). The UREx Project integrates social, ecological and technical systems

to support urban decision-making in the face of climate change.

55

This research

includes scenario modeling projections for spatial variability in heat and heat risk and

vulnerability as well as examining how green infrastructure and other interventions may

impact exposure to heat in NYC. Scenario modeling includes linking downscaled US

Census data with the City’s tax lot assessment, land cover, and other land use data to

examine heat and heat impacts at lot level resolution for NYC. The City’s new high

resolution temperature monitoring described above can serve to ground-truth these

model scenarios and suggest renements.

The City has also invested $1.72M to collect updated LiDAR data for NYC. LiDAR is

mapping technology that determines distance to an object or surface using laser pulses

to measure elevation, allowing the creation of three-dimensional topographic maps and

highly accurate surveys of surface terrain, vegetation and manmade structures. The City

is developing several data sets including land cover, tree canopy and other vegetation,

elevation data to map coastal ood hazards, and all types of impervious surfaces.

These data sets, which will be made publicly available in 2018, will help identify areas

Data collection, research

and monitoring

conducted or overseen

by:

NYC Mayor’s Ofce of

Recovery and Resiliency

NYC Department of

Health and Mental

Hygiene

NYC Department of

Parks and Recreation

City College of New York

Urban Systems Lab at

The New School

Collecting Innovative Data to Deliver Inclusive and

Health-focused Climate Policy

Cool Neighborhoods NYC34

of the city that can benet from prioritized tree plantings and additional greening and

impervious surface removal in order to protect from climate change threats such as the

UHI effect and extreme heat. LiDAR data will also help the City to assess ecosystem

conditions and opportunities for forest restoration and green infrastructure planning. In

all, the landscape of the city has changed since we last collected LiDAR data in 2010 due

to many natural events and human interventions, and the new data will help to inform

our understanding and investment in the city’s resiliency and sustainability.

The City is also collaborating with researchers at the City College of New York (CUNY) to

install a high-density hydro-meteorological weather network around the city. This one of

the kind network will monitor basic meteorological and hydrological variables to assess

the variability in NYC’s microclimates and their response to extreme events. The network

will deliver real time observations of temperature, humidity and rainfall, which can be

used to create an early warning system during heatwaves and ooding. The network will

also be used to improve city-scale climate modeling that can be used to study how future

climate scenarios will impact different neighborhoods within the city. The framework

will be an effective platform to assess the impact of various climate moderation and

extreme heat mitigation strategies.

The CUNY Center for Remote Sensing and Technology Institute is developing state-of-

the-art citywide high-resolution weather research and a forecasting tool. The tool will

use the high resolution LiDAR data that the City will make available to represent the

complex morphology of NYC and will ingest data from the weather networks around the

city to create neighborhood scale weather forecast. In contrast to the current forecast

Figure 23: The LiDAR data being captured will be among the most accurate ever collected for a municipality

since our 2010 capture, providing numerous government agencies with critical information. LiDAR point cloud

data of Central Park. Source: OneNYC

35Cool Neighborhoods NYC

produced by the National Weather Service, the improved tool will have representation for

various urban processes. For example, the tool can quantify the impact of heat released

from buildings’ air-conditioning systems. The forecasting platform will aid several

weather and climate-related critical operational activities. The tool is currently used

to dynamically downscale future climate scenarios projected by the Intergovernmental

Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) for New York City.

Innovative data collection is essential in climate adaptation planning. At its core, the

City’s research and modeling efforts with academic partners can be used to communicate

more effectively with affected communities so that the linkages between increased

vegetation, lighter surfaces and social adaptation strategies are understood by all New

Yorkers, leading to temperature reduction and positive social outcomes including:

community preparedness and stewardship, energy savings, increased economic activity,

increased productivity, improved health and safety and enhanced quality of life.

Cool Neighborhoods NYC36

Looking Forward

37Cool Neighborhoods NYC

For years, the City has confronted the issue of heat-vulnerability head-on by developing

and implementing multi-agency programs. These include heat emergency response

plans, conducting enhanced surveillance after the 2006 heat waves, working with the

National Weather Service to update heat product public warning language for NYC,

coordinating the opening of cooling centers, issuing safety alerts and advance warnings

for special needs populations and their service providers, and launching programs such

as the Fire Department’s spray cap program, which allows New Yorkers to safely use re

hydrants to stay cool during hot weather.

Still, there is work to be done and through OneNYC, the Mayor’s Ofce of Recovery and

Resiliency is leading this effort. Moving forward, the City will assess the feasibility

of incorporating a heat vulnerability assessment in the New York City Environmental

Quality Review (CEQR) Technical Manual, which is the city’s guidance document for

environmental review. In addition, it is crucial to continue to increase tree canopy cover

in the city and to that end we will continue to fulll our commitments for tree planting

and stewardship funding, and will explore the feasibility of lowering the minimum

distance required between trees along sidewalks in order to maximize shading. Finally,

we will assess opportunities to maximize vegetation within open parking and other

areas. Our central strategy has been to leverage key NYC assets: our robust public health,

emergency response and parks infrastructure, local climate risk projections, existing

cross-sector agency programs, and the research and support of our local academic

institutions and community-based organizations. We have worked with practitioners,

academics, and colleagues in other cities and states across the U.S. and abroad to identify

adaptation strategies and health-based interventions, to get up-to-date information on

the implementation status of their own climate initiatives and to solicit feedback on our

approaches.

As much as possible, our strategies to adapt to climate change have built upon existing

programs and have integrated our City staff and partners to advance program goals. We

have worked to strengthen collaboration with agencies and organizations that provide

and promote access to essential services; including those involved in the prevention of

environmental exposures, the planning and monitoring of community health, and the

planning of emergency preparedness and response plans. Cool Neighborhoods NYC moves

us towards a ner-grained neighborhoods-based analysis that will lead to improved

quality of life for all New Yorkers and deliver inclusive climate action that protects public

health and addresses environmental justice. By greening neighborhoods and increasing

access to air conditioning and cool spaces, we aim to reduce heat-related health impacts,

and reduce disparities in vulnerability to climate change.

Our Cool Neighborhoods NYC heat mitigation and adaptation program is a multi-pronged,

comprehensive strategy that will deliver sustainability and resiliency benets to all New

Yorkers, but especially to those who are most vulnerable to heat-related health risks.

Together, we are building community resiliency by continuously expanding interventions

known to prevent illness and death from climate-related hazards and by continuously

enhancing risk communication strategies for vulnerable New Yorkers.

Cool Neighborhoods NYC38

Acknowledgements

Cool Neighborhoods NYC was created with the shared vision of delivering inclusive climate action and sustainability and resiliency

benets to all New Yorkers, but especially to those who are most vulnerable to heat-related health risks. This multi-pronged,

comprehensive strategy will help to reduce heat-related health impacts and deaths, mitigate high temperatures in heat-vulnerable

neighborhoods, strengthen social networks, and improve quality of life for all New Yorkers. This program is a result of an incredibly

collaborative process that was made possible by the hard work and dedication of numerous individuals who believed in this vision

and shared their experience, analysis, ideas, insight, energy, time, and passion.

Program Development Team and Report Editors

New York City Mayor’s Ofce of Recovery and Resiliency

Kizzy Charles-Guzman, Deputy Director, Social and Economic Resiliency

Anna Colarusso, Urban Fellow

Daniella Henry, Policy Advisor

Hyunjin Kim, Program Manager

Erika Lindsey, Senior Policy Advisor

Thank you to each member of the Urban Heat Island Mitigation Working Group, with special thanks to

Bram Gunther, Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR); Sarah Johnson and Munerah Ahmed, Department of Health and Mental

Hygiene (DOHMH); Ahmed Chaudry, Department of Small Business Services (SBS); Kurt Shickman, Global Cool Cities Alliance;

Laurie Kerr, Urban Green Council; Timon McPhearson, Urban Systems Lab at The New School.

Special Collaborators

Jennifer Greenfeld and Kristen King (DPR); Kelly Dougherty, Abby Marquand, and Amy Furman (SBS); Kathryn Lane, Kazuhiko Ito,

Kristin Woods (DOHMH); Erin Cuddihy and Wendy Feuer (DOT); Esther Bruner (OEC); Zachary Youngerman and Miki Urisaka (DEP);

Christopher Pagnotta (NYCEM); Zoe Hamstead (SUNY at Buffalo); Prathap Ramamurthy (CCNY); Alex Schneider (Sustainable South

Bronx); Sarah Charlop-Powers (Natural Areas Conservancy); Daniel Aldrich (Northeastern University); Fall 2016 Capstone Project,

Master of Science in Sustainability Management Program, Columbia University.

Ofce of the Mayor

Anthony Shorris, First Deputy Mayor

Benjamin Furnas, Special Advisor for Policy and Planning, Ofce of the First Deputy Mayor

Dan Zarrilli, Senior Director; Climate Policy and Programs

Jainey Bavishi, Director, Ofce of Recovery and Resiliency

Michael Shaikh, Deputy Director, External Affairs, Ofce of Recovery and Resiliency

Susanne DesRoches, Deputy Director, Infrastructure, Ofce of Recovery and Resiliency

The incredibly hardworking staffs at the following City agencies:

Department of Buildings, Department of City Planning,

Department of Design and Construction, Department of

Environmental Protection, NYC Emergency Management,

Department of Small Business Services, Department of

Transportation, New York City Housing Authority, Ofce of

Management and Budget, Mayor’s Ofce of Operations, NYC

Service, Mayor’s Ofce of Stainability, and the Mayor’s Ofce of

Recovery and Resiliency.

Volunteers on the roof of Noll Street Apartments. The Ridgewood

Bushwick Senior Citizen’s Council, Brooklyn. September 2016. Source:

Alex Schneider, SSBx a division of the HOPE Program.

39Cool Neighborhoods NYC

Endnotes

1. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

(2016). Climate Change and Extreme Heat What You Can Do To Prepare. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/

climateandhealth/pubs/extreme-heat-guidebook.pdf.

2. Berko, J., Ingram, D.D., Saha, S., Parker, J.D. (2014). Deaths attributed to heat, cold, and other weather events in the

United States, 2006-2010. National Health Stat Report (76): 1-15.

3. Rosenzweig, C., Solecki, W. NYC Panel on Climate Change. (NPCC). (2015). Building the Knowledge Base for Climate

Resiliency: NYC Panel on Climate Change 2015 Report. New York Academy of Science 1336: 1–149. Available at:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/nyas.12653/full.

4. NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH). (2014). Epi Data Brief, No. 47. Available at: https://

www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/epi/databrief47.pdf.

5. Matte, T.D., Lane, K., Ito, K. Excess Mortality Attributable to Extreme Heat in New York City, 1997-2013. (2016).

Health Security. 14(2): 64-70. https://doi.org/10.1089/hs.2015.0059.

6. Rosenzweig, C., Solecki, W. NYC Panel on Climate Change. (NPCC). (2015). Building the Knowledge Base for Climate

Resiliency: NYC Panel on Climate Change 2015 Report. New York Academy of Science 1336: 1–149. Available at:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/nyas.12653/full.

7. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2008). Reducing Urban Heat Islands: Compendium of Strategies, Trees and

Vegetation. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/heat-islands/using-trees-and-vegetation-reduce-heat-islands.

8. Madrigano, J., Ito, K., Johnson, S., Kinney, P. L., & Matte, T. (2015). A Case-Only Study of Vulnerability to Heat Wave–

Related Mortality in New York City (2000–2011). Environmental Health Perspectives. 123(7): 672–678. Available

at: http://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1408178.

9. Stabler, L. B., Martin, C. A., & Brazel, A. J. (2005). Microclimates in a Desert City were Related to Land Use and

Vegetation Index. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 3(3): 137-147.

10. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2008). Reducing Urban Heat Islands: Compendium of Strategies, Trees and

Vegetation. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/heat-islands/using-trees-and-vegetation-reduce-heat-islands.

11. Akbari, H., Kurn, D.M., Bretz, S.E., and Hanford, J.W. (1997). Peak Power and Cooling Energy Savings of Shade Trees.

Energy and Buildings 25: 139-148.

12. Larondelle, N., Hamstead, Z.A., Kremer, P., Haase, D., and McPhearson, T. (2014). Applying a novel urban structure

classication to compare the relationships of urban structure and surface temperature in Berlin and New York City.

Applied Geography 53: 427-437. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2014.07.004.

13. Maas, J., Verheij, R.A, Groenewegen, P.P, De Vries, S., Spreeuwenberg, P. (2006). Green space, urbanity, and

health: how strong is the relation? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 60(7): 587-592. http://doi.

org/10.1136/jech.2005.043125

14. McPhearson, T., Maddox, D., Gunther, B.m and Bragdon, D. (2013). Local Assessment of New York City: Biodiversity,

Green Space, and Ecosystem Services. Urbanization, Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Challenges and

Opportunities: 35-383. Available at: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-007-7088-1_19/fulltext.

html.

Cool Neighborhoods NYC40

15. Dunnett, N., & Kingsbury, N. (2008). Planting green roofs and living walls. Portland, OR: Timber Press.

16. Qin, Y. (2015). A review on the development of cool pavements to mitigate urban heat island effect. Renewable

and Sustainable Energy Reviews 52: 445-459. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.07.177.

17. NYC Department of Buildings (DOB). (2016). Green Roofs. http://www1.nyc.gov/site/buildings/business/green-

roofs.page.

18. Akbari, H., Levinson, R., Rosenfeld, A., and Elliot, M. (2009). Global Cooling: Policies to Cool the World and Offset

Global Warming from CO2 Using Reective Roofs and Pavements. Heat Island. Available at: http://heatisland2009.

lbl.gov/docs/231200-akbari-doc.pdf.

19. U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). (2017). Energy Saver: Cool Roofs. Available at: https://energy.gov/energysaver/

cool-roofs.

20. NYC Small Business Services (SBS). (2017). Industrial & Construction Training. Available at: http://www1.nyc.gov/

site/sbs/careers/industrial-training.page.

21. NYC Small Business Services. (2017). NYC CoolRoofs. Available at: https://www1.nyc.gov/nycbusiness/article/nyc-

coolroofs.

22. Hoverter, S. (2012). Adapting to urban heat: A Tool Kit for Local Governments. Georgetown Climate Center: 1-92.

Available at: http://kresge.org/sites/default/les/climate-adaptation-urban-heat.pdf.

23. Cool Roof Toolkit. (2012). A Practical Guide to Cool Roofs and Cool Pavements. Available at: http://www.

coolrooftoolkit.org/wp-content/pdfs/CoolRoofToolkit_Full.pdf.

24. Akbari, H., Pomerantz, M. and Taha, H. (2001). Cool Surfaces and Shade Trees to Reduce Energy Use and Improve Air

Quality in Urban Areas. Solar Energy. 70(3): 295-310.

25. Hewitt, V., Mackres, E., and Shickman, K. (2014). Cool Policies for Cool Cities: Best Practices for Mitigating Urban

Heat Islands in North American Cities. American Council for an Energy-Efcient Economy and Global Cool Cities

Alliance: 1-53. Available at: http://www.coolrooftoolkit.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/ACEEE_GCCA-UHI-

Policy-Survey-FINAL.pdf.