U.S. Department of Justice

Office of Justice Programs

National Institute of Justice

research report

Extent, Nature, and

Consequences of Intimate

Partner Violence

Findings From the National

Violence Against Women Survey

U.S. Department of Justice

Office of Justice Programs

810 Seventh Street N.W.

Washington, DC 20531

Janet Reno

Attorney General

Daniel Marcus

Acting Associate Attorney General

Mary Lou Leary

Acting Assistant Attorney General

Julie E. Samuels

Acting Director, National Institute of Justice

Office of Justice Programs National Institute of Justice

World Wide Web Site World Wide Web Site

http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/nij

Extent, Nature, and

Consequences of Intimate

Partner Violence

Patricia Tjaden

Nancy Thoennes

July 2000

NCJ 181867

Findings From the National

Violence Against Women Survey

Julie E. Samuels

Acting Director, National Institute of Justice

Stephen B. Thacker

Acting Director, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control

This research was sponsored jointly by the National Institute of Justice and the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention under NIJ Grant # 93–IJ–CX–0012. The opinions and conclusions expressed in this document are solely

those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Justice or the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention.

The National Institute of Justice is a component of the Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the

Bureau of Justice Assistance, the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency

Prevention, and the Office for Victims of Crime.

CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL

AND PREVENTION

iii

Executive Summary

This report presents findings from the National

Violence Against Women (NVAW) Survey on

the extent, nature, and consequences of inti-

mate partner violence in the United States.

The National Institute of Justice and the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

cosponsored the survey through a grant to the

Center for Policy Research. The survey con-

sists of telephone interviews with a nationally

representative sample of 8,000 U.S. women

and 8,000 U.S. men about their experiences as

victims of various forms of violence, including

intimate partner violence.

The survey compares intimate partner victim-

ization rates among women and men, specific

racial groups, Hispanics and non-Hispanics,

and same-sex and opposite-sex cohabitants.

It also examines risk factors associated with

intimate partner violence, the rate of injury

among rape and physical assault victims,

injured victims’ use of medical services, and

victims’ involvement with the justice system.

Analysis of the survey data produced the

following results:

● Intimate partner violence is pervasive in

U.S. society. Nearly 25 percent of surveyed

women and 7.6 percent of surveyed men

said they were raped and/or physically

assaulted by a current or former spouse,

cohabiting partner, or date at some time

in their lifetime; 1.5 percent of surveyed

women and 0.9 percent of surveyed men

said they were raped and/or physically

assaulted by a partner in the previous 12

months. According to these estimates, ap-

proximately 1.5 million women and 834,732

men are raped and/or physically assaulted

by an intimate partner annually in the

United States. Because many victims are

victimized more than once, the number of

intimate partner victimizations exceeds the

number of intimate partner victims annually.

Thus, approximately 4.8 million intimate

partner rapes and physical assaults are per-

petrated against U.S. women annually, and

approximately 2.9 million intimate partner

physical assaults are committed against U.S.

men annually. These findings suggest that

intimate partner violence is a serious crimi-

nal justice and public health concern.

● Stalking by intimates is more prevalent than

previously thought. Almost 5 percent of sur-

veyed women and 0.6 percent of surveyed

men reported being stalked by a current or

former spouse, cohabiting partner, or date at

some time in their lifetime; 0.5 percent of

surveyed women and 0.2 percent of sur-

veyed men reported being stalked by such a

partner in the previous 12 months. Accord-

ing to these estimates, 503,485 women and

185,496 men are stalked by an intimate

partner annually in the United States. These

estimates exceed previous nonscientific

“guesstimates” of stalking prevalence in the

general population. These findings suggest

that intimate partner stalking is a serious

criminal justice problem, and States should

continue to develop constitutionally sound

and effective antistalking statutes and inter-

vention strategies.

● Women experience more intimate partner

violence than do men. The NVAW survey

found that women are significantly more

likely than men to report being victims of

intimate partner violence whether it is rape,

physical assault, or stalking and whether

the timeframe is the person’s lifetime or the

iv

previous 12 months. These findings support

data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics’

National Crime Victimization Survey,

which consistently show women are at sig-

nificantly greater risk of intimate partner

violence than are men. However, they con-

tradict data from the National Family Vio-

lence Survey, which consistently show men

and women are equally likely to be physi-

cally assaulted by an intimate partner. Stud-

ies are needed to determine how different

survey methodologies affect women’s and

men’s responses to questions about intimate

partner violence.

● Rates of intimate partner violence vary sig-

nificantly among women of diverse racial

backgrounds. The survey found that Asian/

Pacific Islander women and men tend to re-

port lower rates of intimate partner violence

than do women and men from other minor-

ity backgrounds, and African-American and

American Indian/Alaska Native women and

men report higher rates. However, differ-

ences among minority groups diminish

when other sociodemographic and relation-

ship variables are controlled. More research

is needed to determine how much of the dif-

ference in intimate partner prevalence rates

among women and men of different racial

and ethnic backgrounds can be explained

by the respondent’s willingness to disclose

intimate partner violence and how much by

social, demographic, and environmental

factors. Research is also needed to deter-

mine how prevalence rates vary among

women and men of diverse American

Indian/Alaska Native and Asian/Pacific

Islander groups.

● Violence perpetrated against women by inti-

mates is often accompanied by emotionally

abusive and controlling behavior. The sur-

vey found that women whose partners were

jealous, controlling, or verbally abusive

were significantly more likely to report

being raped, physically assaulted, and/or

stalked by their partners, even when other

sociodemographic and relationship character-

istics were controlled. Indeed, having a ver-

bally abusive partner was the variable most

likely to predict that a woman would be

victimized by an intimate partner. These

findings support the theory that violence

perpetrated against women by intimates is

often part of a systematic pattern of domi-

nance and control.

● Women experience more chronic and injuri-

ous physical assaults at the hands of intimate

partners than do men. The survey found that

women who were physically assaulted by an

intimate partner averaged 6.9 physical as-

saults by the same partner, but men averaged

4.4 assaults. The survey also found that 41.5

percent of the women who were physically

assaulted by an intimate partner were injured

during their most recent assault, compared

with 19.9 percent of the men. These findings

suggest that research aimed at understanding

and preventing intimate partner violence

against women should be stressed.

● Women living with female intimate partners

experience less intimate partner violence

than women living with male intimate part-

ners. Slightly more than 11 percent of the

women who had lived with a woman as part

of a couple reported being raped, physically

assaulted, and/or stalked by a female cohabi-

tant, but 30.4 percent of the women who

had married or lived with a man as part of a

couple reported such violence by a husband

or male cohabitant. These findings suggest

that lesbian couples experience less intimate

partner violence than do heterosexual

couples; however, more research is needed

to support or refute this conclusion.

● Men living with male intimate partners expe-

rience more intimate partner violence than do

men who live with female intimate partners.

Approximately 15 percent of the men who

had lived with a man as a couple reported

v

being raped, physically assaulted, and/or

stalked by a male cohabitant, while 7.7 per-

cent of the men who had married or lived

with a woman as a couple reported such vio-

lence by a wife or female cohabitant. These

findings, combined with those presented in

the previous bullet, provide further evidence

that intimate partner violence is perpetrated

primarily by men, whether against male or

female intimates. Thus, strategies for pre-

venting intimate partner violence should

focus on risks posed by men.

● The U.S. medical community treats millions

of intimate partner rapes and physical as-

saults annually. Of the estimated 4.8 million

intimate partner rapes and physical assaults

perpetrated against women annually, ap-

proximately 2 million will result in an injury

to the victim, and 552,192 will result in some

type of medical treatment to the victim. Of

the estimated 2.9 million intimate partner

physical assaults perpetrated against men an-

nually, 581,391 will result in an injury to the

victim, and 124,999 will result in some type

of medical treatment to the victim. Many

medically treated victims receive multiple

forms of care (e.g., ambulance services,

emergency room care, or physical therapy)

and multiple treatments (e.g., several days

in the hospital) for the same victimization.

Therefore, the number of medical personnel

treating injuries annually is in the millions.

To better meet the needs of intimate partner

violence victims, medical professionals

should receive training on the physical con-

sequences of intimate partner violence and

appropriate medical intervention strategies.

● Most intimate partner victimizations are not

reported to the police. Approximately one-

fifth of all rapes, one-quarter of all physical

assaults, and one-half of all stalkings perpe-

trated against female respondents by inti-

mates were reported to the police. Even

fewer rapes, physical assaults, and stalkings

perpetrated against male respondents by inti-

mates were reported. The majority of victims

who did not report their victimization to the

police thought the police would not or could

not do anything on their behalf. These find-

ings suggest that most victims of intimate

partner violence do not consider the justice

system an appropriate vehicle for resolving

conflicts with intimates.

vii

Acknowledgments

The authors thank staff at both the National

Institute of Justice (NIJ) and the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in

particular Lois Mock at NIJ and Linda

Saltzman at CDC, for their advice and

support in conducting the research.

The authors also thank Marcie-jo Kresnow,

mathematical statistician at CDC, and anony-

mous NIJ peer reviewers for their thorough

review and helpful comments on drafts of this

report. Finally, the authors thank Christine

Allison and Gay Dizinski at the Center for

Policy Research for their help in producing and

scrutinizing drafts of the report.

ix

Contents

Executive Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iii

Acknowledgments. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . vii

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Defining Intimate Partner Violence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Prevalence and Incidence of Intimate Partner Violence. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Intimate partner rape. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Intimate partner physical assault . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Intimate partner stalking. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Comparison With Previous Estimates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Intimate partner rape. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Intimate partner physical assault . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Intimate partner stalking. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Women Experience More Intimate Partner Violence Than Do Men . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Deciphering Disparities in Survey Findings. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence Among Racial Minorities and Hispanics . . . . . . 25

Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence Among Same-Sex Cohabitants. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Risk Factors Associated With Intimate Partner Violence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Point in Relationship When Violence Occurs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Frequency and Duration of Intimate Partner Rape and Physical Assault . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

Rate of Injury Among Victims of Intimate Partner Rape and Physical Assault . . . . . . . . . 41

Risk factors associated with injury. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

Victims’ Use of Medical Services . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Estimates of medical services utilization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

x

Victims’ Involvement With the Justice System . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

Reporting to the police . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

Police response to reports of intimate partner violence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

Reasons for not reporting victimization to the police. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

Criminal prosecution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

Temporary restraining orders . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

Estimates of justice system utilization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

Policy Implications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

xi

Exhibits

Exhibit 1. Persons Victimized by an Intimate Partner in Lifetime and in Previous 12 Months,

by Type of Victimization and Gender

Exhibit 2. Number of Rape, Physical Assault, and Stalking Victimizations Perpetrated by

Intimate Partners Annually, by Victim Gender

Exhibit 3. Persons Physically Assaulted by an Intimate Partner in Lifetime, by Type of Assault

and Victim Gender

Exhibit 4. Estimated Standard Errors Multiplied by the z-Score (1.96) for a 95-Percent

Confidence Level, by Sample or Subsample Size

Exhibit 5. Persons Victimized by an Intimate Partner in Lifetime, by Victim Gender, Type of

Victimization, and White/Nonwhite Status of Victim

Exhibit 6. Persons Victimized by an Intimate Partner in Lifetime, by Victim Gender, Type of

Victimization, and Victim Race

Exhibit 7. Persons Victimized by an Intimate Partner in Lifetime, by Victim Gender, Type of

Victimization, and Hispanic/Non-Hispanic Origin of Victim

Exhibit 8. Persons Victimized by an Intimate Partner in Lifetime, by Victim Gender, Type of

Victimization, and History of Same-Sex/Opposite-Sex Cohabitation

Exhibit 9. Rate of Intimate Partner Victimization, by Perpetrator Gender, Victim Gender, and

History of Same-Sex/Opposite-Sex Cohabitation

Exhibit 10. Distribution of Female Victims of Intimate Partner Rape, Physical Assault, and

Stalking, by Point in Relationship When the Violence Occurred

Exhibit 11. Distribution of Rape and Physical Assault Victims, by Frequency and Duration of

Victimization and Gender

Exhibit 12. Distribution of Intimate Partner Rape and Physical Assault Victims, by Injury,

Type of Medical Care Received, and Gender

Exhibit 13. Distribution of Injured Rape and Physical Assault Victims, by Type of Injury

Sustained: Women Only

Exhibit 14. Average Number of Medical Care Visits for Intimate Partner Rape and Physical

Assault Victims, by Type of Medical Care and Gender

xii

Exhibit 15. Average Annual Injury and Medical Utilization Estimates for Adult Victims of

Intimate Partner Rape and Physical Assault, by Gender

Exhibit 16. Distribution of Intimate Partner Rape, Physical Assault, and Stalking Victims,

by Law Enforcement Outcomes and Gender

Exhibit 17. Distribution of Rape, Physical Assault, and Stalking Victims Who Did Not Report

Their Victimization to the Police, by Reasons for Not Reporting and Gender

Exhibit 18. Distribution of Intimate Partner Rape, Physical Assault, and Stalking Victims,

by Prosecution Outcomes and Gender

Exhibit 19. Distribution of Intimate Partner Rape, Physical Assault, and Stalking Victims,

by Protective Order Outcomes and Gender

Exhibit 20. Average Annual Justice System Utilization Estimates for Adult Victims of Intimate

Partner Rape, Physical Assault, and Stalking, by Gender

1

Introduction

Research on intimate partner violence has in-

creased dramatically over the past 20 years.

While greatly enhancing public awareness and

understanding of this serious social problem,

this research has also created much controversy

and confusion. Findings of intimate partner vic-

timization vary widely from study to study.

1

Some studies conclude that women and men are

equally likely to be victimized by their partners,

2

but others conclude that women are more likely

to be victimized.

3

Some studies conclude that

minorities and whites suffer equal rates of inti-

mate partner violence,

4

and others conclude that

minorities suffer higher rates.

5

In addition, there are many gaps in the scientific

literature on intimate partner violence, such as

the level of violence committed against men and

women by same-sex intimates.

6

Little empirical

data exist on the relationship between different

forms of intimate partner violence, such as emo-

tional abuse and physical assault.

7

Finally, little

is known of the consequences of intimate partner

violence, including rate of injury and victims’

use of medical and justice system services.

8

This Research Report addresses these and other

issues related to intimate partner violence. The

information presented in this report is based on

findings from the National Violence Against

Women (NVAW) Survey, a national telephone

survey jointly sponsored by the National Insti-

tute of Justice (NIJ) and the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC). The survey,

which was conducted from November 1995 to

May 1996, consists of telephone interviews with

a representative sample of 8,000 U.S. women

and 8,000 U.S. men. Survey respondents were

queried about their experiences as victims of

various forms of violence, including rape,

physical assault, and stalking by intimate

partners. Victimized respondents were asked

detailed questions about the characteristics and

consequences of their victimization, including

the extent and nature of any injuries they sus-

tained, their use of medical services, and their

involvement with the justice system.

This Research Report also summarizes the

survey’s findings on victimization rates among

women and men, specific racial groups, Hispan-

ics and non-Hispanics, and opposite-sex and

same-sex cohabitants. It examines risk factors

associated with intimate partner violence, rates

of injury among rape and physical assault vic-

tims, injured victims’ use of medical services,

and victims’ involvement with the justice sys-

tem. Although this report focuses on women’s

and men’s experiences as victims of intimate

partner violence, complete details about men’s

and women’s experiences as victims of rape,

physical assault, and stalking by all types of

assailants are contained in earlier NIJ and CDC

reports (see sidebar, “Other Publications in the

Series”).

Because of the sensitive nature of the survey,

state-of-the-art techniques were used to protect

the confidentiality of the information being

sought and to minimize the potential for

retraumatizing victims of violence and

jeopardizing the safety of respondents.

● The sample was generated through random-

digit dialing, thereby ensuring that only a 10-

digit telephone number linked the respondent

to the survey. The area code and telephone

exchanges were included as part of the com-

pleted interview for each case in the dataset

for analysis purposes, but the last four digits

of the telephone number were eliminated.

2

● The survey introduction informed respondents

that their answers would be kept confidential

and that participation in the survey was

voluntary.

● Respondents were given a toll-free number to

call to verify the authenticity of the survey or

to respond to the survey at a later date. Re-

spondents also were told to use this number

should they need to hang up suddenly during

the interview.

● Only female interviewers interviewed female

respondents. (To measure the possible effects

of interviewer gender on male responses to

survey questions, half of the male respondents

were interviewed by male interviewers and

half by female interviewers.)

● Interviewers were instructed to schedule a

callback interview if they thought someone

was listening to the interview on another

line or was in the room with the respondent.

● Interviewers, out of concern that the interview

might cause some victims of violence to expe-

rience emotional trauma, were provided with

rape crisis and domestic violence hotline tele-

phone numbers from around the country. If a

respondent showed signs of distress, he or

she was provided with an appropriate hotline

referral.

In addition to lessening the possibility that re-

spondents might be harmed due to their partici-

pation in the survey, these techniques improved

the quality of the information gathered.

Other Publications in the Series

Other publications related to the National

Violence Against Women Survey include:

● Stalking in America: Findings From the

National Violence Against Women Survey,

Research in Brief, by Patricia Tjaden and

Nancy Thoennes, Washington, D.C.: U.S.

Department of Justice, National Institute

of Justice, 1998, NCJ 169592.

● Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences

of Violence Against Women: Findings From

the National Violence Against Women

Survey, Research in Brief, by Patricia

Tjaden and Nancy Thoennes, Washington,

D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, National

Institute of Justice, 1998, NCJ 172837.

● Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences

of Violence Against Women, Research

Report, by Patricia Tjaden and Nancy

Thoennes, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Depart-

ment of Justice, National Institute of Justice,

forthcoming.

To obtain copies of these documents, visit

NIJ’s Web site at http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/nij

or contact the National Criminal Justice

Service at P.O. Box 6000, Rockville, MD

20849–6000, 800–851–3420 or 301–519–

5500, or send an e-mail message to

askncjrs@ncjrs.org. Additional reports in

the series are forthcoming.

Also of interest:

● National Violence Against Women Method-

ology Report by Patricia Tjaden, Steven

Leadbetter, John Boyle, and Robert A.

Bardwell, Atlanta: Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention, National Center for

Injury Prevention and Control, forthcoming.

Learn about the availability of this report and

other CDC family and intimate violence pre-

vention activities by visiting the National Cen-

ter for Injury Prevention and Control’s Web

site at http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/dvp/fivpt.

3

Notes

1. For example, lifetime rates of victimization by an

intimate range from 9 to 30 percent for women and

from 13 to 16 percent for men. See Nisonoff, L.,

and I. Bittman, “Spouse Abuse: Incidence and

Relationship to Selected Demographic Variables,”

Victimology 4 (1979): 131–140; Peterson, R., “So-

cial Class, Social Learning, and Wife Abuse,” Social

Service Review 50 (1980): 390–406; Schulman, M.,

A Survey of Spousal Violence Against Women In

Kentucky, Study Number 792701, Washington, D.C.:

U.S. Department of Justice, Law Enforcement Assis-

tance Administration, 1979; Teske, R.H.C., and M.L.

Parker, Spouse Abuse in Texas: A Study of Women’s

Attitudes and Experiences, Newark, New Jersey:

Criminal Justice/National Center for Crime and

Delinquency, John Cotton Dana Library, 1983;

Scanzoni, J., Sex Roles, Women’s Work, and Marital

Conflict, Lexington, Massachusetts: Lexington

Books, 1978.

2. Schafer, J., R. Caetano, C.L. Clark, “Rates of Inti-

mate Partner Violence in the United States,” Ameri-

can Journal of Public Health 88 (11) (1998): 1702–

1704; Straus, M.A., “Trends in Cultural Norms and

Rates of Partner Violence: An Update to 1992,”

in Understanding Partner Violence: Prevalence,

Causes, Consequences, and Solutions, Families in

Focus Series, eds. M.A. Straus and S.M. Smith,

Minneapolis: National Council on Family Relations,

1995: 30–33; Straus, M., and R. Gelles, “Societal

Change and Change in Family Violence From 1975

to 1985 as Revealed by Two National Surveys,”

Journal of Marriage and the Family 48 (1987):

465–479.

3. Bachman, R., Violence Against Women: A

National Crime Victimization Survey Report, Wash-

ington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of

Justice Statistics, 1994, NCJ 145325; Bachman, R.,

and L.E. Saltzman, Violence Against Women: Esti-

mates From the Redesigned Survey, Special Report,

Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice,

Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1995, NCJ 154348;

Gaquin, D., “Spouse Abuse: Data from the National

Crime Survey,” Victimology 2 (1977–78): 634–643;

Greenfeld, L., M.R. Rand, D. Craven, P.A. Klaus,

C.A. Perkins, C. Ringel, G. Warchol, C. Matson,

and J.A. Fox, Violence by Intimates: Analysis of

Data on Crimes by Current or Former Spouses,

Boyfriends, and Girlfriends, Bureau of Justice

Statistics Factbook, Washington, D.C.: U.S.

Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics,

1998, NCJ 167237; Klaus, P., and M. Rand, Family

Violence, Special Report, Washington, D.C.: U.S.

Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics,

1984, NCJ 093449.

4. Bachman, Violence Against Women: A National

Crime Victimization Survey Report.

5. For example, see Bachman, R., Death and Vio-

lence on the Reservation: Homicide, Family Vio-

lence, and Suicide in American Indian Populations,

Westport, Connecticut: Auburn House, 1992;

Cazenave, N.A., and M.A. Straus, “Race, Class,

Network Embeddedness and Family Violence: A

Search for Potent Support Systems,” Journal of

Comparative Family Studies 10 (3) (1979): 281–

300; Gelles, R., “Violence in the Family: A Review

of Research in the Seventies,” Journal of Marriage

and the Family 42 (1980): 873–885; Hampton, R.L.,

“Family Violence and Homicides in the Black Com-

munity: Are They Linked?” in Violence in the Black

Family: Correlates and Consequences, ed. R.L.

Hampton, Lexington, Massachusetts, 1987: 135–

187; Neff, J.A., B. Holamon, and T.D. Schluter,

“Spousal Violence Among Anglos, Blacks, and

Mexican Americans: The Role of Demographic

Variables, Psychological Predictors, and Alcohol

Consumption,” Journal of Family Violence 10 (1)

(1995): 1–21; Shoemaker, D.J., and J.S. Williams,

“The Subculture of Violence and Ethnicity,” Journal

of Criminal Justice 15 (6) (1987): 461–472; and

Behind Closed Doors, ed. Straus, M.A., R.J. Gelles,

and S. Steinmetz, Newbury Park, California: Sage

Publications, 1980.

6. Renzetti, C.M., “Violence and Abuse Among

Same-Sex Couples,” in Violence Between Intimate

Partners: Patterns, Causes, and Effects, ed.

Cardarelli, A.P., Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1997:

70–89.

7. National Research Council, Understanding

Violence Against Women, Washington, D.C.:

National Academy Press, 1996: 4–5.

8. Ibid.

5

Defining Intimate Partner Violence

There is currently little consensus among re-

searchers on exactly how to define the term

“intimate partner violence.”

1

As a result, defini-

tions of the term vary widely from study to

study, making comparisons difficult. One source

of controversy revolves around whether to limit

the definition of the term to acts carried out with

the intention of, or perceived intention of, caus-

ing physical pain or injury to another person.

Although this approach presents a narrow defini-

tion of intimate partner violence that can be

readily operationalized, it ignores the myriad

behaviors that persons may use to control, in-

timidate, and otherwise dominate another person

in the context of an intimate relationship. These

behaviors may include acts such as verbal abuse,

imprisonment, humiliation, stalking, and denial

of access to financial resources, shelter, or

services.

Another source of controversy revolves around

whether to limit the definition of the term to

violence occurring between persons who are

married or living together as a couple or to in-

clude persons who are dating or who consider

themselves a couple but live in separate domi-

ciles. At present the research literature is bifur-

cated, with some studies focusing on violence

occurring in marital or heterosexual cohabiting

relationships and others focusing on violence

occurring in heterosexual dating relationships.

Only a handful of studies examine violence in

same-sex cohabiting or dating relationships.

The definition of intimate partner violence used

in the NVAW Survey includes rape, physical

assault, and stalking perpetrated by current and

former dates, spouses, and cohabiting partners,

with cohabiting meaning living together at least

some of the time as a couple. Both same-sex

and opposite-sex cohabitants are included in the

definition. The survey’s definition of intimate

partner violence resembles the one developed

by CDC

2

because it includes violence occurring

between persons who have a current or former

dating, marital, or cohabiting relationship and

same-sex and opposite-sex cohabitants. However,

it deviates from CDC’s definition because it in-

cludes stalking as well as rape and physical assault.

For purposes of the survey, “rape” is defined as

an event that occurs without the victim’s consent

and involves the use of threat or force to pen-

etrate the victim’s vagina or anus by penis,

tongue, fingers, or object or the victim’s mouth

by penis. The definition includes both attempted

and completed rape. “Physical assault” is defined

as behaviors that threaten, attempt, or actually

inflict physical harm. The definition includes

a wide range of behaviors, from slapping, push-

ing, and shoving to using a gun. “Stalking” is

defined as a course of conduct directed at a

specific person involving repeated visual or

physical proximity; nonconsensual communica-

tion; verbal, written, or implied threats; or a

combination thereof that would cause fear in a

reasonable person, with “repeated” meaning on

two or more occasions. The definition of stalk-

ing used in the survey does not require stalkers

to make a credible threat against victims, but it

does require victims to feel a high level of fear.

The specific questions used to screen respon-

dents for rape, physical assault, and stalking

victimization are behaviorally specific and are

designed to leave little doubt in the respondent’s

mind as to what is being measured (see sidebar,

“Survey Screening Questions”).

6

Survey Screening Questions

Rape: Five questions were used to screen

respondents for completed and attempted

rape victimization:

a

● [Female respondents only] Has a man or

boy ever made you have sex by using force

or threatening to harm you or someone

close to you? Just so there is no mistake,

by sex we mean putting his penis in your

vagina.

● Has anyone, male or female, ever made you

have oral sex by using force or threat of

force? Just so there is no mistake, by oral

sex we mean that a man or boy put his penis

in your mouth or someone, male or female,

penetrated your vagina or anus with their

mouth.

● Has anyone ever made you have anal sex by

using force or threat of force? Just so there

is no mistake, by anal sex we mean that a

man or boy put his penis in your anus.

● Has anyone, male or female, ever put

fingers or objects in your vagina or anus

against your will or by using force or

threats?

● Has anyone, male or female, ever attempted

to make you have vaginal, oral, or anal sex

against your will but intercourse or penetra-

tion did not occur?

Physical assault: A modified version of the

original Conflict Tactics Scale was used to

screen respondents for physical assault they

experienced as an adult at the hands of

another adult:

b

● Not counting any incidents you have already

mentioned, after you became an adult, did

any other adult, male or female, ever:

— Throw something at you that could hurt?

— Push, grab, or shove you?

— Pull your hair?

— Slap or hit you?

— Kick or bite you?

— Choke or attempt to drown you?

— Hit you with some object?

— Beat you up?

— Threaten you with a gun?

— Threaten you with a knife or other

weapon?

— Use a gun on you?

— Use a knife or other weapon on you?

Stalking: The following questions were

used to screen respondents for stalking

victimization:

● Not including bill collectors, telephone

solicitors, or other salespeople, has

anyone, male or female, ever:

— Followed or spied on you?

— Sent you unsolicited letters or written

correspondence?

— Made unsolicited phone calls to you?

— Stood outside your home, school, or

workplace?

— Showed up at places you were even

though he or she had no business being

there?

— Left unwanted items for you to find?

— Tried to communicate in other ways

against your will?

— Vandalized your property or destroyed

something you loved?

Respondents who answered yes to one or

more of these questions were asked whether

anyone had ever done any of these things on

7

Notes

1. National Research Council, Understanding

Violence Against Women, Washington, D.C.:

National Academy Press, 1996: 9–10.

2. Saltzman, L.E., J.L. Fanslow, P.M. McMahon,

and G.A. Shelley, Intimate Partner Violence Surveil-

lance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data

Elements, Atlanta: National Center for Injury Pre-

vention and Control, Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention, 1999.

more than one occasion and whether they felt

frightened or feared bodily harm as a result of

these behaviors. Only respondents who re-

ported being victimized on more than one oc-

casion and who were very frightened or feared

bodily harm were counted as stalking victims.

Victim-perpetrator relationship: Respon-

dents who answered affirmatively to the rape,

physical assault, and/or stalking screening

questions were asked whether their attacker

was a current or ex-spouse, a male live-in

partner, a female live-in partner, a relative,

someone else they knew, or a stranger. Re-

spondents disclosing victimization by an ex-

spouse or cohabiting partner were asked to

further identify which spouse/partner victim-

ized them (e.g., first ex-husband, current male

live-in partner). Respondents disclosing vic-

timization by a relative were asked to further

specify which relative victimized them (e.g.,

father, brother, uncle, cousin). Finally, respon-

dents disclosing victimization by someone

else they knew were asked to further specify

the relationship they had with this person

(e.g., date, boss, teacher, neighbor). Only

victimizations perpetrated by current and

former spouses, same-sex and opposite-sex

cohabiting partners, and dates are included

in the analyses discussed in this report.

a. Rape screening questions were adapted from

those used in The National Women’s Study, Rape in

America: A Report to the Nation, National Victim

Center and the Crime Victims Research and Treatment

Center, Arlington, Virginia, April 23, 1992: 15.

b. Straus, M., “Measuring Intrafamily Conflict and

Violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scale,” Journal of

Marriage and the Family 41 (1979): 75–88.

9

Prevalence and Incidence of Intimate

Partner Violence

The NVAW Survey generated information on

both the prevalence and incidence of intimate

partner violence. “Prevalence” refers to the per-

centage of persons within a demographic group

(e.g., female or male) who are victimized during

a specific period, such as the person’s lifetime or

the previous 12 months. “Incidence” refers to the

number of separate victimizations or incidents of

violence committed against persons within a demo-

graphic group during a specific period. Incidence

can also be expressed as a victimization rate,

which is obtained by dividing the number of vic-

timizations committed against persons in a de-

mographic group by the number of persons in

that demographic group and setting the rate to a

standard population base, such as 1,000 persons.

1

Intimate partner rape

Using a definition of rape that includes com-

pleted or attempted forced vaginal, oral, and

anal sex, the survey found 7.7 percent of

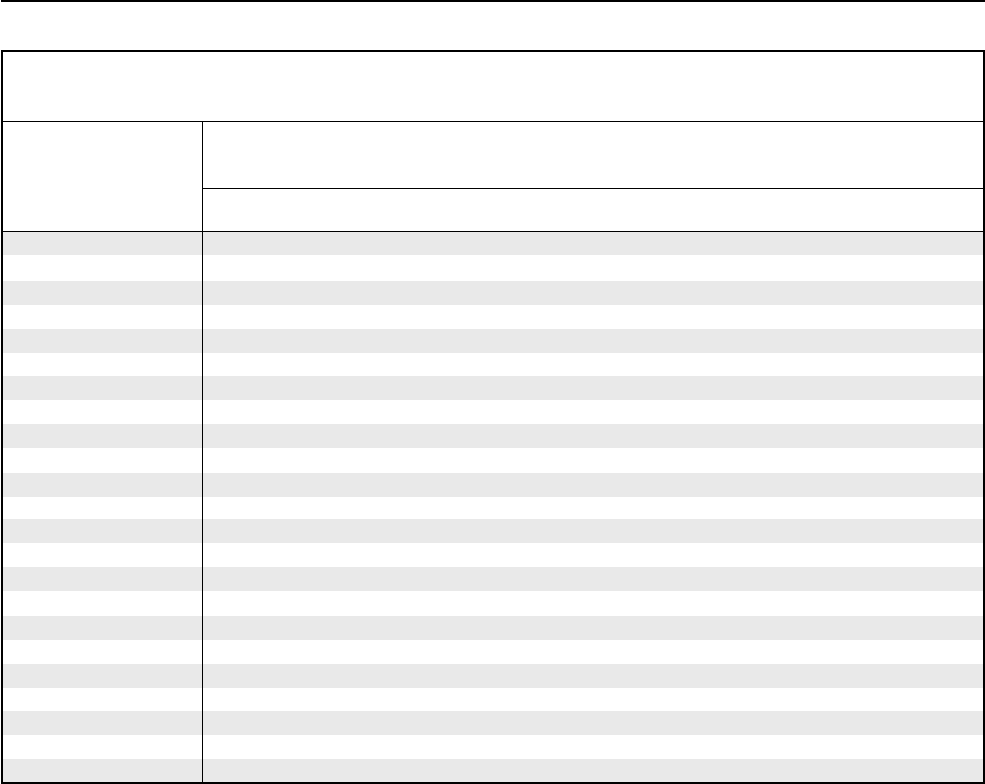

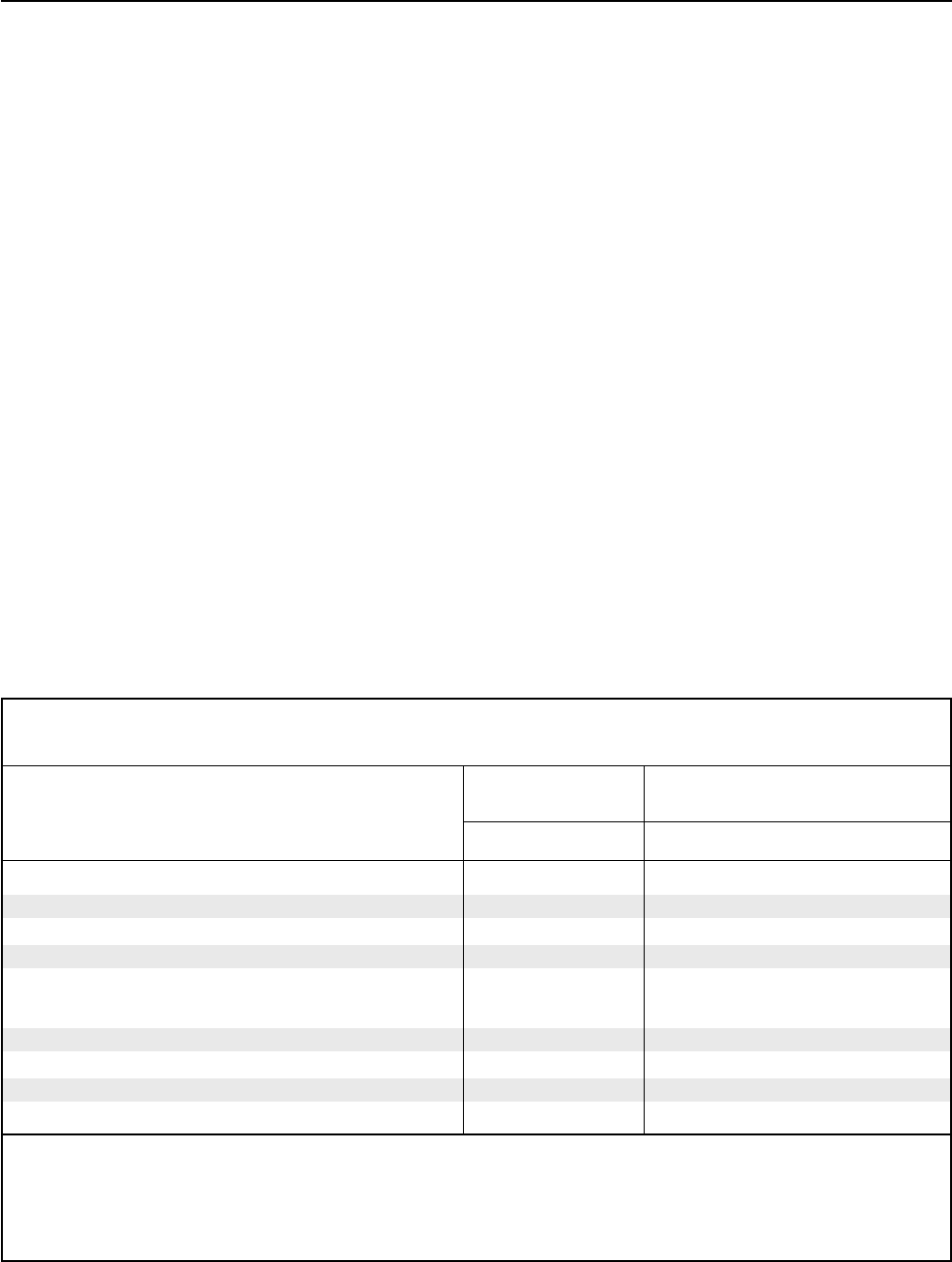

Exhibit 1. Persons Victimized by an Intimate Partner in Lifetime and in

Previous 12 Months, by Type of Victimization and Gender

In Lifetime

Percent Number

a

Women Men Women Men

Type of Victimization (

n

= 8,000) (

n

= 8,000) (100,697,000) (92,748,000)

Rape

b***

7.7 0.3 7,753,669 278,244

Physical assault

b***

22.1 7.4 22,254,037 6,863,352

Rape and/or physical assault

b***

24.8 7.6 24,972,856 7,048,848

Stalking

b***

4.8 0.6 4,833,456 556,488

Total victimized

b***

25.5 7.9 25,677,735 7,327,092

In Previous 12 Months

Percent Number

a

Women Men Women Men

Type of Violence (

n

= 8,000) (

n

= 8,000) (100,697,000) (92,748,000)

Rape 0.2 —

c

201,394 —

c

Physical assault

b*

1.3 0.9 1,309,061 834,732

Rape and/or physical assault

b*

1.5 0.9

d

1,510,455 834,732

Stalking

b**

0.5 0.2 503,485 185,496

Total victimized

b***

1.8 1.1 1,812,546 1,020,228

a

Based on estimates of women and men 18 years of age and older: Wetrogen, S.I.,

Projections of the Population of States by

Age, Sex, and Race: 1988 to 2010

, Current Population Reports, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1988: 25–1017.

b

Differences between women and men are statistically significant: χ

2

, *

p

≤ .05, **

p

≤ .01,

***p

≤ .001.

c

Estimates not calculated on fewer than five victims.

d

Because only three men reported being raped by an intimate partner in the previous 12 months, the percentage of men physically

assaulted and physically assaulted and/or raped is the same.

10

surveyed women and 0.3 percent of surveyed

men reported being raped by a current or former

intimate partner at some time in their lifetime,

and 0.2 percent (n = 16) of surveyed women re-

ported being raped by a partner in the 12 months

preceding the survey. Based on U.S. Census esti-

mates of the number of women aged 18 years

and older in the country, an estimated 201,394

women were forcibly raped by an intimate

partner in the 12 months preceding the survey

(exhibit 1). [The number of male rape victims

(n < 5) was insufficient to reliably calculate

annual prevalence estimates for men.]

Because women raped by an intimate partner in

the previous 12 months averaged 1.6 rapes, the

incidence of intimate partner rape (number of

separate victimizations) exceeded the prevalence

of intimate partner rape (number of victims).

Thus, there were an estimated 322,230 intimate

partner rapes committed against U.S. women dur-

ing the 12 months preceding the survey. (This na-

tional estimate is based on only 16 women who

reported being raped by an intimate partner in the

previous 12 months and should be viewed with

caution.) This figure equates to an annual victim-

ization rate of 3.2 intimate partner rapes per 1,000

U.S. women aged 18 years and older (322,230 ÷

100,697,000 = 0.0032 x 1,000 = 3.2) (exhibit 2).

Intimate partner physical assault

Using a definition of physical assault that in-

cludes a range of behaviors, from slapping and

hitting to using a gun, the survey found that 22.1

percent of surveyed women and 7.4 percent of

surveyed men reported being physically assaulted

by a current or former intimate partner at some

time in their lifetime, whereas 1.3 percent of all

surveyed women and 0.9 percent of all surveyed

men reported being physically assaulted by such a

partner in the previous 12 months. Thus, approxi-

mately 1.3 million women and 834,732 men were

physically assaulted by an intimate partner in the

12 months preceding the survey (exhibit 1).

Because women and men who were physically

assaulted by an intimate partner in the previous

12 months averaged 3.4 and 3.5 physical as-

saults, respectively, there were approximately

4.5 million intimate partner physical assaults

perpetrated against women and approximately

2.9 million intimate partner physical assaults

perpetrated against men in the 12 months pre-

ceding the survey. These figures equate to an

annual victimization rate of 44.2 intimate part-

ner physical assaults per 1,000 U.S. women aged

18 years and older (4,450,807 ÷ 100,697,000 =

0.0442 x 1,000 = 44.2) and 31.5 intimate partner

Exhibit 2. Number of Rape, Physical Assault, and Stalking Victimizations

Perpetrated by Intimate Partners Annually, by Victim Gender

Number Average Number Total Number Annual Rate of

Type of of of Victimizations of Victimization per

Victimization Victims per Victim

a

Victimizations 1,000 Persons

Women

Rape

c

201,394 1.6

b

322,230

b

3.2

Physical assault 1,309,061 3.4 4,450,807 44.2

Stalking 503,485 1.0 503,485 5.0

Men

Rape

c

— — — —

Physical assault 834,732 3.5 2,921,562 31.5

Stalking 185,496 1.0 185,496 1.8

a

The standard error of the mean is 0.5 for female rape victims, 0.6 for female physical assault victims, and 0.6 for male

physical assault victims. Because stalking by definition means repeated acts and because no victim was stalked by more than

one perpetrator in the 12 months preceding the survey, the number of stalking victimizations was imputed to be the same as the

number of stalking victims. Thus, the average number of stalking victimizations per victim is 1.0.

b

Relative standard error exceeds 30 percent.

c

Estimates not calculated on fewer than five victims.

11

physical assaults per 1,000 U.S. men aged 18

years and older (2,921,562 ÷ 92,748,000 =

0.0315 x 1,000 = 31.5) (exhibit 2).

Results from the survey show that most physical

assaults committed against women and men by

intimates are relatively minor and consist of

pushing, grabbing, shoving, slapping, and hit-

ting. Fewer women and men reported that an

intimate threw something that could hurt them,

pulled their hair, kicked or beat them, or threat-

ened them with a knife or gun. Only a negligible

number reported that an intimate actually used a

knife or gun on them (exhibit 3).

Intimate partner stalking

Using a definition of stalking that requires vic-

tims to feel a high level of fear, the survey found

that 4.8 percent of surveyed women and 0.6 per-

cent of surveyed men reported being stalked by

a current or former intimate partner at some time

in their lifetime; 0.5 percent of surveyed women

and 0.2 percent of surveyed men reported being

stalked by such a partner in the 12 months pre-

ceding the survey. These figures equate to an

estimated 503,485 women and 185,496 men

who were stalked by an intimate partner in the

12 months preceding the survey (exhibit 1).

Because stalking by definition involves repeated

acts of harassment and intimidation and because

no respondent reported being stalked by more

than one intimate in the 12 months preceding

the survey, the incidence of intimate partner

stalking is equivalent to the prevalence of

intimate partner stalking. Thus, there were an

estimated 503,485 stalking victimizations per-

petrated against women and 185,496 stalking

victimizations perpetrated against men by

intimates in the year preceding the survey

(exhibit 2). These figures equate to an annual

victimization rate of 5 intimate partner stalkings

per 1,000 U.S. women aged 18 years and older

(503,485 ÷ 100,697,000 = 0.005 x 1,000 = 5.0)

and 1.8 intimate partner stalkings per 1,000

U.S. men aged 18 years and older (185,496 ÷

97,748,000 = 0.0018 x 1,000 = 1.8) (exhibit 2).

Note

1. Koss, M.P., and M.R. Harvey, The Rape Victim:

Clinical and Community Interventions, 2d ed.

Newbury Park, California: Sage Publications,

1991: 8–9.

Exhibit 3. Persons Physically Assaulted by an Intimate

Partner in Lifetime, by Type of Assault and Victim Gender

Women (%) Men (%)

Type of assault

a

(

n

= 8,000) (

n

= 8,000)

Threw something that could hurt 8.1 4.4

Pushed, grabbed, shoved 18.1 5.4

Pulled hair 9.1 2.3

Slapped, hit 16.0 5.5

Kicked, bit 5.5 2.6

Choked, tried to drown 6.1 0.5

Hit with object 5.0 3.2

Beat up 8.5 0.6

Threatened with gun 3.5 0.4

Threatened with knife 2.8 1.6

Used gun 0.7 0.1

b

Used knife 0.9 0.8

Total reporting physical assault by intimate partner 22.1 7.4

a

With the exception of “used gun” and “used knife,” differences between women and men are statistically significant: χ

2

,

p

≤ .001.

b

Relative standard error exceeds 30 percent; statistical tests not performed.

13

Comparison With Previous Estimates

Intimate partner rape

No previous national survey has generated esti-

mates of the lifetime prevalence of intimate

partner rape.

1

However, a study of 930 women

in San Francisco found that 8 percent were sur-

vivors of marital rape,

2

and a study of 323 ever-

married/cohabited women in Boston found that

10 percent were survivors of wife or partner

rape.

3

Though not directly comparable, the

NVAW Survey finding that 7.7 percent of U.S.

women have been raped by an intimate partner

at some time in their lifetime is similar to these

earlier community-based estimates.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics’ National Crime

Victimization Survey (NCVS), which is admin-

istered yearly, generates annual rape and sexual

assault victimization estimates for women and

men. One study based on 1992–93 NCVS data

found that the average annual rate of rape and

sexual assault by an intimate was 1.0 per 1,000

women aged 12 years and older.

4

This estimate

is lower than the average annual rate of intimate

partner rape for women generated by the NVAW

Survey, which is 3.2 per 1,000 women aged 18

years and older (exhibit 2). However, direct

comparisons between the findings of the two

surveys are difficult to make because estimates

reported by the two surveys refer to somewhat

different populations and sexual victimizations,

and the two surveys differ substantially method-

ologically (see “Deciphering Disparities in Sur-

vey Findings”).

Intimate partner physical assault

Several community-based studies have gener-

ated estimates of the lifetime prevalence of

physical assault by an intimate. Estimates from

these surveys range from 9 to 30 percent for

women and from 13 to 16 percent for men (see

note 1 in “Introduction”). In addition, a 1997

Gallup poll, which surveyed a nationally repre-

sentative sample of 434 women and 438 men,

found that 22 percent of women and 8 percent of

men have been physically abused by a spouse or

companion.

5

NVAW Survey estimates that 22.1

percent of women and 7.4 percent of men have

been physically assaulted by an intimate at some

time in their lifetime are nearly identical to the

Gallup estimates.

National estimates of the annual rate of physical

assault by an intimate come from two primary

sources—the previously mentioned NCVS and

the National Family Violence Survey (NFVS),

which was first conducted in 1975 and then re-

peated in 1985. Portions of the NFVS were also

included in the 1992 National Alcohol and Fam-

ily Violence Survey and a special component of

the 1995 National Alcohol Survey.

Annual rates of physical assault by an intimate

generated from the NVAW Survey are substan-

tially higher than those generated by the NCVS.

One study based on 1992–93 NCVS data found

that the average annual rate of simple and aggra-

vated assault by an intimate was 7.6 per 1,000

women aged 12 years and older and 1.3 per 1,000

men aged 12 years and older.

6

A more recent

study that used 1996 NCVS data and Federal

Bureau of Investigation Uniform Crime Report

homicide data—and combined data on intimate

partner murder, rape, sexual assault, robbery,

aggravated assault, and simple assault—found the

annual rate of violent victimization by an intimate

was 7.5 per 1,000 women aged 12 years and older

and 1.4 per 1,000 men aged 12 years and older.

7

In comparison, the NVAW Survey annual rate of

physical assault by an intimate was 44.2 per 1,000

women aged 18 years and older and 31.5 per

1,000 men aged 18 years and older. Thus, the

14

NVAW Survey annual rate of physical assault by

an intimate far exceeds the NCVS annual rate of

violent victimization by an intimate.

On the other hand, annual rates of physical

assault generated from the NVAW Survey are

substantially lower than those generated by the

NFVS. The 1975 and 1985 NFVS found that

11 to 12 percent of married/cohabiting women

and 12 percent of married/cohabiting men were

physically assaulted by their intimate partner an-

nually.

8

The 1992 National Alcohol and Family

Violence Survey found that approximately 1.9

percent of married/cohabiting women were se-

verely assaulted by a male partner annually, and

approximately 4.5 percent of married/cohabiting

men were severely assaulted by a female partner

annually.

9

The 1995 National Alcohol Survey

found that 5.2 to 13.6 percent of married/cohab-

iting couples experienced male-to-female part-

ner violence, and 6.2 to 18.2 percent of married/

cohabiting couples experienced female-to-male

intimate partner violence.

10

In comparison,

the NVAW Survey found that only 1.3 percent

of surveyed women and 0.9 percent of surveyed

men were physically assaulted by a current or

former intimate partner annually. The disparity

in NFVS and NVAW findings is particularly

striking because both surveys used similar

behaviorally specific questions to screen

respondents for physical assault victimization.

As discussed in this report (see “Deciphering

Disparities in Survey Findings”), studies are

needed to determine why the NCVS, NFVS, and

NVAW Survey produced such disparate findings

on the prevalence and incidence of intimate part-

ner violence in the United States.

Intimate partner stalking

Prior to the NVAW Survey, information on stalk-

ing prevalence was limited to guesses provided

by mental health professionals based on their

work with known stalkers. The most frequently

cited “guesstimate” was made by forensic psy-

chiatrist Dr. Park Dietz, who reported in 1992

that 5 percent of U.S. women are stalked at

some time in their lifetime, and 500,000 are

stalked annually.

11

Because these figures pertain

to stalking by all types of perpetrators, not just

intimates, it is fair to say the NVAW Survey

estimates—that 4.8 percent of women have

been stalked by an intimate in their lifetime

and 503,485 women are stalked by an intimate

each year—are higher than previous stalking

estimates.

Notes

1. The National Women’s Study generated estimates

of the prevalence of rape by all types of assailants

but not by intimates; see Rape in America: A Report

to the Nation, Arlington, Virginia: National Victim

Center and the Crime Victims Research and Treat-

ment Center, April 23, 1992.

2. Russell, D.E.H., Rape in Marriage, Indianapolis:

Indiana University Press, 1990.

3. Finklehor, D., and K. Yllo, License To Rape:

Sexual Abuse of Wives, New York: Holt, Rinehart,

and Winston, 1985.

4. Bachman, R., and L.E. Saltzman, Violence

Against Women: Estimates From the Redesigned

Survey, Special Report, Washington, D.C.: U.S. De-

partment of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics,

1995, NCJ 154348.

5. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Bureau of Justice Sta-

tistics Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics—

1997, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice,

Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1998: 198, NCJ 171147,

table 3.39.

6. Bachman and Saltzman, Violence Against

Women: Estimates From the Redesigned Survey,

note 4.

7. Greenfeld, L., M.R. Rand, D. Craven, P.A. Klaus,

C.A. Perkins, C. Ringel, G. Warchol, C. Matson, and

J.A. Fox, Violence by Intimates: Analysis of Data on

Crimes by Current or Former Spouses, Boyfriends,

and Girlfriends, Bureau of Justice Statistics

Factbook, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of

Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1998, NCJ

167237.

15

8. Straus, M., and R. Gelles, “Societal Change and

Change in Family Violence From 1975 to 1985 as

Revealed by Two National Surveys,” Journal of

Marriage and the Family 48 (1987): 465–479.

9. Straus, M.A., “Trends in Cultural Norms and

Rates of Partner Violence: An Update to 1992,”

in Understanding Partner Violence: Prevalence,

Causes, Consequences, and Solutions, Families

in Focus Series, eds. M.A. Straus and S.M. Smith,

Minneapolis: National Council on Family Relations,

1995: 30–33.

10. Schafer, J., R. Caetano, and C.L. Clark, “Rates

of Intimate Partner Violence in the United States,”

American Journal of Public Health 88 (11) (1998):

1702–1704.

11. Puente, M., “Legislators Tackling the Terror

of Stalking: But Some Experts Say Measures Are

Vague,” USA Today, July 21, 1992.

17

Women Experience More Intimate Partner

Violence Than Do Men

As shown in exhibit 1, the NVAW Survey found

that women were significantly more likely than

men to report being victimized by an intimate

partner, whether the period was the individual’s

lifetime or the 12 months preceding the survey

and whether the type of violence was rape,

physical assault, or stalking. Moreover, the sur-

vey found that differences between women’s and

men’s rates of physical assault by an intimate

partner become greater as the seriousness of the

assault increases. For example, women were two

or three times more likely than men to report that

an intimate partner threw something that could

hurt them or pushed, grabbed, or shoved them.

However, they were 7 to 14 times more likely to

report that an intimate partner beat them up,

choked or tried to drown them, or threatened

them with a gun or knife (exhibit 3).

The NVAW Survey finding that women are sig-

nificantly more likely than men to report being

victimized by an intimate partner supports re-

sults from the NCVS, which have consistently

shown that women are at significantly greater

risk of intimate partner violence (see note 3 in

“Introduction”). However, it contradicts results

from the NFVS, which have consistently shown

that men and women are nearly equally likely to

be physically assaulted by marital or cohabiting

partners (see note 2 in “Introduction”).

19

It is difficult to explain why the NCVS, NFVS,

and NVAW Survey generated such disparate

estimates of intimate partner violence or why

the NCVS and NVAW Survey produced evi-

dence of asymmetry in women’s and men’s risk

of intimate partner violence while the NFVS

produced evidence of symmetry. For years, re-

searchers have attributed the low rate of intimate

partner violence uncovered by the NCVS to the

fact that it is administered in the context of a

crime survey. Because they reflect only violence

perpetrated by intimates that victims are willing

to label as criminal and report to interviewers,

estimates of intimate partner violence generated

from the NCVS are thought to underestimate

the true amount of intimate partner violence.

1

At first glance, results from the NVAW Survey ap-

pear to support this theory. The NVAW Survey—

which was administered in the context of a survey

on personal safety rather than crime—generated

substantially higher intimate partner victimization

rates than those generated by the NCVS. It is

likely, however, that methodological factors other

than the overall context in which the two surveys

were administered account for some of the differ-

ences in the findings.

For example, the two surveys differ substantially

with respect to sample design and survey admin-

istration. The NVAW Survey sample was drawn

by random-digit dialing from a database of

households with a telephone (see sidebar, “Sur-

vey Methodology”). Moreover, NVAW Survey

interviewers used state-of-the-art techniques

to protect the confidentiality of the respondents

and minimize the potential for retraumatizing

victims of violence. In comparison, the NCVS

sample consists of housing units (e.g., ad-

dresses) selected from a stratified multistage

cluster sample. When a sample unit is

selected for inclusion in the NCVS, U.S. Census

workers interview all individuals in the house-

hold 12 years of age and older every 6 months

for 3 years. Thus, after the first interview, re-

spondents know the contents of the survey. This

may pose a problem for victims of domestic vio-

lence who may be afraid that disclosing abuse

by a family member may put them in danger

of further abuse. Although census interviewers

document whether others were present during

the interview, time and budget constraints prevent

them from ensuring privacy during an interview.

In addition, screening questions used by the

NVAW Survey and the NCVS differ substantially.

For example, the NVAW Survey uses 5 ques-

tions to screen respondents for rapes they may

have sustained over their lifetime and 12 ques-

tions to screen respondents for physical assaults

they may have sustained as adults (see sidebar,

“Survey Screening Questions”). Respondents

disclosing victimization are asked additional

questions about the victim-perpetrator relation-

ship and the frequency, duration, and consequences

of their victimization. In comparison, the NCVS

uses four questions—each with multiple compo-

nents—to screen respondents for threats, physi-

cal and sexual attacks, and property crimes they

may have experienced in different locations and

by different offenders.

2

Although empirical data

on this issue are lacking, researchers assume that

both the number of screening questions used

and the manner in which they are asked affect

disclosure rates.

3

Another possible reason for the difference in the

NVAW Survey and NCVS findings is that published

NCVS estimates count series victimization—reports

of six or more crimes within a 6-month period for

which the respondent cannot recall details of each

crime—as a single victimization. Thus, published

Deciphering Disparities in Survey Findings

20

Survey Methodology

The National Violence Against Women

(NVAW) Survey was conducted from No-

vember 1995 to May 1996 by interviewers

at Schulman, Ronca, Bucuvalas, Inc. (SRBI)

under the direction of John Boyle.

a

The au-

thors of this report designed the survey and

conducted the analysis.

The sample was drawn by random-digit

dialing from a database of households with

a telephone in the 50 States and the District

of Columbia. The sample was administered

by U.S. Census region. Within each region, a

simple random sample of working residential

“hundreds banks” of phone numbers was

drawn. (A hundreds bank is the first 8 digits

of any 10-digit telephone number.) A ran-

domly generated 2-digit number was ap-

pended to each randomly sampled hundreds

bank to produce the full 10-digit, random-

digit number. Separate banks of numbers

were generated for male and female respon-

dents. These random-digit numbers were

called by SRBI interviewers from their cen-

tral telephone facility, where nonworking

and nonresidential numbers were screened

out. Once a residential household was

reached, eligible adults were identified. In

households with more than one eligible adult,

the adult with the most recent birthday was

selected as the designated respondent.

A total of 8,000 women and 8,005 men 18

years of age and older were interviewed

using a computer-assisted telephone inter-

viewing (CATI) system. (Five completed in-

terviews with men were subsequently elimi-

nated from the sample during data editing

due to an excessive amount of inconsistent

and missing data.) Only female interviewers

surveyed female respondents. To test for pos-

sible bias introduced by the gender of the in-

terviewer, a split-sample approach was used

in the male sample whereby half of the inter-

views were conducted by female interviewers

and half by male interviewers. A Spanish-

language translation was administered by

bilingual interviewers to Spanish-speaking

respondents.

To determine how representative the sample

was, select demographic characteristics of the

NVAW Survey sample were compared with

demographic characteristics of the general

population as measured by the U.S. Census

Bureau’s 1995 Current Population Survey of

adult men and women. Sample weighting

was considered to correct for possible biases

introduced by the fact that some households

had multiple phone lines and multiple eli-

gibles and for over- and underrepresentation

of selected subgroups. Although there were

some instances of over- and underrepresenta-

tion, the overall unweighted prevalence rates

for rape, physical assault, and stalking were

not significantly different from their respec-

tive weighted rates. As a result, sample

weighting was not used in the analysis of

the survey data.

b

Data were analyzed using SPSS Base 7.0 for

Windows software. Measures of association

were calculated between nominal-level

independent and dependent variables. The

chi-square statistic was used to test for statis-

tically significant differences between two

groups (e.g., men and women), and the

Tukey’s B statistic was used to test for statis-

tically significant differences among two or

more groups (e.g., whites, African-Americans,

Asian/Pacific Islanders, American Indian/

Alaska Natives, and mixed-race persons). Any

estimates based on fewer than five responses

were deemed unreliable and, therefore, were

not tested for statistically significant differ-

ences between or among groups and were not

presented in the tables. Because estimates pre-

21

sented in this report generally exclude “don’t

know,” “refused,” and other invalid responses,

sample and subsample sizes (n’s) vary from

table to table.

Because the actual number of victims that is

insufficient to reliably calculate estimates

varies depending on the rarity of the exposure

and the denominator of the subgroup being

analyzed, the relative standard error (RSE)

was calculated for each estimate presented.

(RSE is the ratio of the standard error divided

by the actual point estimate.) Estimates with

RSEs that exceed 30 percent were deemed un-

stable and were not tested for statistically sig-

nificant differences between or among groups.

These estimates have been identified in the

tables and should be viewed with caution.

The estimates from this survey, as from any

sample survey, are subject to random sam-

pling error. Exhibit 4 presents the estimated

standard errors multiplied by the z-score

(1.96) for specified sample and subsample

sizes of 16,000 or less at different response

distributions of dichotomous variables (e.g.,

raped/not raped, injured/not injured). These

estimated standard errors can be used to

determine the extent to which sample esti-

mates will be distributed (bounded) around

the population parameter (i.e., the true pop-

ulation distribution). As exhibit 4 shows,

larger sample and subsample sizes produce

smaller estimated bounds. Thus, the esti-

mated bound at the 95-percent confidence

level for a sample or subsample of 8,000 is

1.1 percentage points if the response distri-

bution is a 50/50 split, whereas the estimated

bound at the 95-percent confidence level for

a sample or subsample of 50 is 14 percentage

points if the response distribution is a 50/50

split.

a. John Boyle, Ph.D., is senior vice president and

director of the Government and Social Research

Division at SRBI. Dr. Boyle, who specializes in pub-

lic policy research in the area of health and violence,

also manages the firm’s Washington, D.C., office.

b. A technical report describing the survey methods in

more detail and recording sample characteristics and

prevalence rates using weighted and unweighted data

will be available from the Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention (see sidebar, “Other Publications in

the Series”).

NCVS estimates of the number of intimate partner

rapes, sexual assaults, and physical assaults are

lower than would be obtained by including all inci-

dents reported to its survey interviewers. To produce

NCVS estimates more directly comparable to those

generated by the NVAW Survey, each crime in a se-

ries of victimizations reported to NCVS interviewers

would have to be counted.

Finally, the sampling errors associated with

the estimates from the NVAW Survey and the

NCVS would have to be compared to determine

whether estimates generated by the two surveys

actually differ or whether apparent differences

are not statistically significant.

Differences between the NVAW Survey and the

NFVS estimates are somewhat harder to explain

because the two surveys used similar sampling

strategies and the Conflict Tactics Scale to

screen respondents for physical assaults by

intimates (see sidebar, “Survey Screening Ques-

tions”). Straus argues the NVAW Survey gener-

ated annual rates of physical assault by an

intimate partner that were substantially lower

than those generated by the NFVS because it

was presented to respondents as a survey on

personal safety.

4

According to Straus, the term

“personal safety” led many respondents to

perceive the NVAW Survey as a crime study

and, therefore, to restrict their reports to “real

crimes.”

22

Aside from being inherently unconvincing—

the terms “crime” and “personal safety” conjure

very different images—this explanation fails to

explain why the NVAW Survey generated high

lifetime intimate partner victimization rates that

are generally consistent with findings from other

surveys or why the NVAW Survey uncovered

high rates of other forms of family violence, such

as incest and physical abuse of children by adult

caretakers.

5

It is unlikely that using the term “per-

sonal safety” in the NVAW Survey introduction

would have set up a perceptual screen for intimate

partner violence experienced in the previous 12

months but not for intimate partner violence expe-

rienced over the course of the respondent’s life-

time. Similarly, it is unlikely that using the term

“personal safety” in the NVAW Survey introduc-

tion would have set up a perceptual screen for one

type of family violence (e.g., physical assaults

by marital/cohabiting partners) but not for other

types of family violence (e.g., incest and physical

assault by caretakers in childhood).

A more plausible explanation for the disparity in

the NFVS and NVAW Survey findings is the dif-

ferent ways the two surveys frame and introduce

screening questions about intimate partner vio-

lence. In the NFVS, respondents are queried

about specific acts of intimate partner violence

they may have committed or sustained against

their current partner. Published NFVS estimates

of the number of women and men who experi-

ence intimate partner violence annually count

reports of both perpetration and victimization.

In other words, if a woman reports that she as-

saulted her husband, her report is counted as a

male victimization. Similarly, if a man reports

that he assaulted his wife, his report is counted

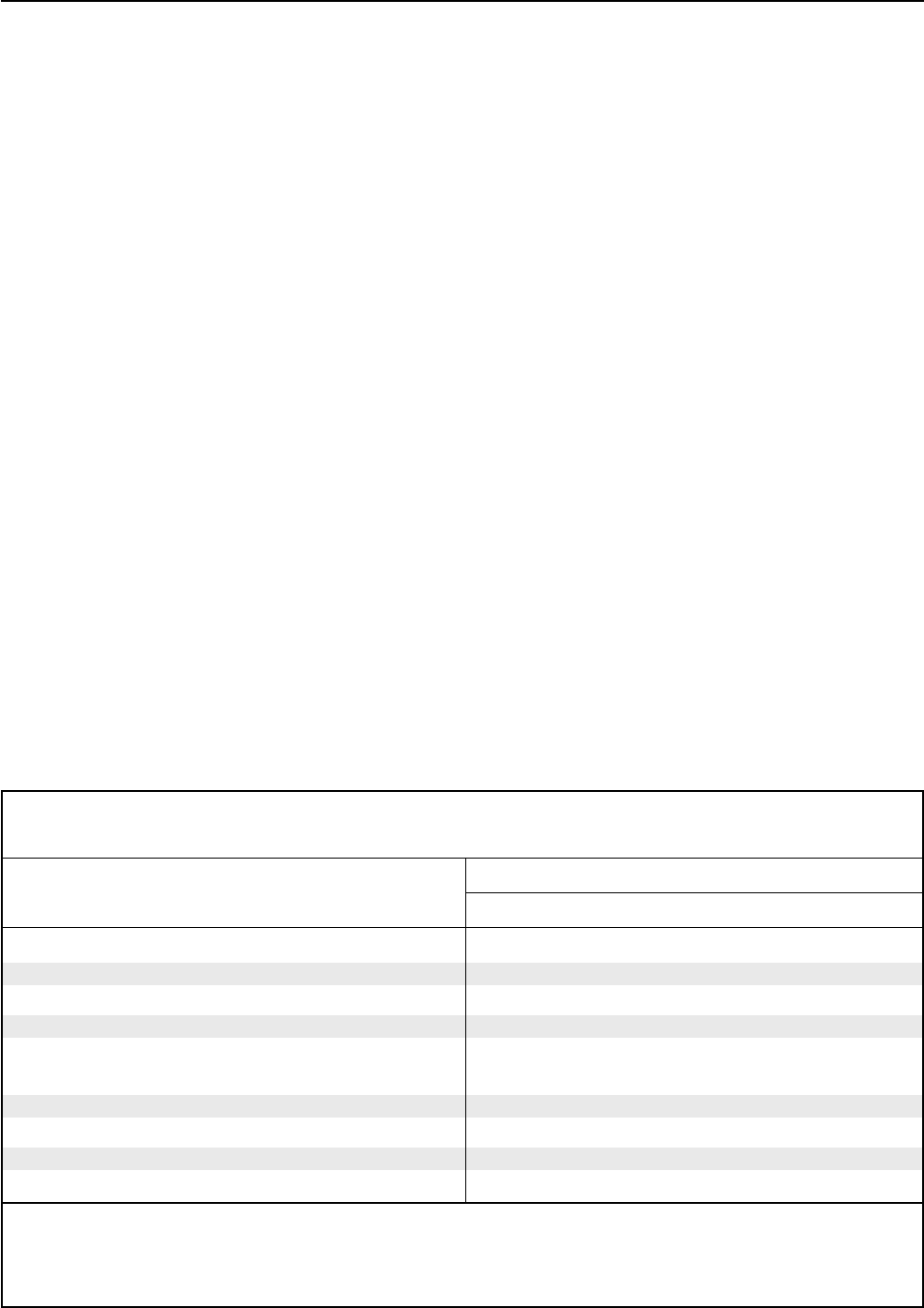

Exhibit 4. Estimated Standard Errors Multiplied by the

z

-Score

(1.96) for a 95-Percent Confidence Level, by Sample or Subsample Size

Percentage of Sample or Subsample Giving Certain Response or Displaying

Certain Characteristics for Percentages Exactly or Approximately Equal to:

Size of Sample

or Subsample 10 or 90 20 or 80 30 or 70 40 or 60 50

16,000 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.8

12,000 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 0.9

8,000 0.7 0.9 1.0 1.1 1.1

4,000 0.9 1.2 1.4 1.5 1.5

3,000 1.1 1.4 1.6 1.8 1.8

2,000 1.3 1.8 2.0 2.1 2.2

1,500 1.5 2.0 2.3 2.5 2.5

1,300 1.6 2.2 2.5 2.7 2.7

1,200 1.7 2.3 2.6 2.8 2.8

1,100 1.8 2.4 2.7 2.9 3.0

1,000 1.9 2.5 2.8 3.0 3.1

900 2.0 2.6 3.0 3.2 3.3

800 2.1 2.8 3.2 3.4 3.5

700 2.2 3.0 3.4 3.6 3.7

600 2.4 3.2 3.7 3.9 4.0

500 2.6 3.5 4.0 4.3 4.4

400 2.9 3.9 4.5 4.8 4.9

300 3.4 4.5 5.2 5.6 5.7

200 4.2 5.6 6.4 6.8 6.9

150 4.8 6.4 7.4 7.9 8.0

100 5.9 7.9 9.0 9.7 9.8

75 6.8 9.1 10.4 11.2 11.4

50 8.4 11.2 12.8 13.7 14.0

23

as a female victimization. To produce NFVS

estimates directly comparable with NVAW Sur-

vey estimates, perpetrations reported to NFVS

interviewers would have to be excluded.

In addition, the NFVS introduces screening

questions about intimate partner violence perpe-

tration and victimization with an exculpatory

statement that acknowledges the pervasiveness

of marital/partner conflict. Although this ap-

proach may seem more accepting of intimate

partner violence and, therefore, more likely to

result in disclosure of intimate partner violence,

it may also be considered more leading.