This document is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International

Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United

States Government.

MONITORING AND EVALUATION SUPPORT ACTIVITY (MEASURE II)

DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY

ASSESSMENT (DECA)

January 2023

MONITORING AND EVALUATION SUPPORT

ACTIVITY (MEASURE II)

DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY

ASSESSMENT (DECA)

External Report

January 2023

Prepared under the USAID Bosnia and Herzegovina Monitoring and Evaluation Support Activity

(MEASURE II), Contract Number AID-167-I-17-00004, Task Order Number 72016819F00001

Submitted to:

USAID/Bosnia and Herzegovina, January 2023

Contractor:

American Institutes for Research® (AIR®)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The American Institutes for Research (AIR) was tasked by the United States Agency for International

Development in Bosnia and Herzegovina (USAID/BiH) under USAID/BiH’s Monitoring and Evaluation

Support Activity (MEASURE II) to conduct the Digital Ecosystem Country Assessment (DECA). The

DECA team included Anela Kadić Abaz, DECA Manager; Troy Etulain, Principal Investigator and

International Subject-Matter Expert; Sadik Crnovršanin, Local Subject-Matter Expert/Technical

Researcher; Amina Mahović, Research Assistant; Boris Badža, Geographic Information System (GIS)

Specialist/Research Assistant; Erol Barina, Research Assistant; and Haris Mešinović, Research Assistant.

The authors express deep gratitude to USAID/BiH DECA Team Lead, Anela Šemić, and Karl Wurster,

Director of USAID/BiH’s Economic Development Office, for providing critical insights and support

during all phases of conducting the DECA. The direction and input of Elma Bukvić Jusić, USAID/BiH

Contracting Officer’s Representative for MEASURE II, were indispensable to the successful completion

of this assessment. The authors wish to thank the USAID/Washington Development, Democracy, and

Innovation Department, notably Craig Jolley and Samantha Chen for their guidance, selfless sharing of

advice and experience, and a detailed review of the report. The authors also extend their sincere

appreciation to all stakeholders, including USAID staff members and implementing partners, government

institutions and agencies, donor and international financial organizations, civil society representatives,

academia, and media representatives who shared their knowledge, opinions, and ideas with the DECA

team and thereby made this assessment possible.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXHIBITS ..................................................................................................................................... I

ACRONYMS ..............................................................................................................................II

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..........................................................................................................1

Key Findings ...................................................................................................................................................... 1

INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................4

ABOUT THIS ASSESSMENT ..................................................................................................4

Road Map for the Report .............................................................................................................................. 5

PILLAR 1: DIGITAL INFRASTRUCTURE AND ADOPTION ........................................6

Connectivity Infrastructure, Security, Interoperability, and Competitiveness ................................. 6

Mobile Coverage ...................................................................................................................................... 9

Internet Use and Consumer Preferences ........................................................................................ 10

Prospects for Expanded Coverage .................................................................................................... 12

Affordability ............................................................................................................................................. 14

Digital Literacy ............................................................................................................................................... 15

The Digital Divide ......................................................................................................................................... 19

Critical Infrastructure, Geopolitics, and Cybersecurity Concerns ................................................... 21

PILLAR 2: DIGITAL SOCIETY, RIGHTS, AND GOVERNANCE ............................... 23

Media and Information Literacy ................................................................................................................. 24

Lack of Government Movement on Structured MIL Approach Despite Donor Interest .... 27

Hate Speech .................................................................................................................................................... 28

Civil Society .................................................................................................................................................... 30

Media ................................................................................................................................................................ 32

Digital Rights and Freedoms ....................................................................................................................... 36

Internet Freedom: Digital Repression .............................................................................................. 37

Digital Government: Delivery of Government Services ...................................................................... 38

E-services ................................................................................................................................................. 39

GSB and Data Exchange ....................................................................................................................... 41

Digital Signatures ........................................................................................................................................... 43

Digital Government: Management of Government Systems .............................................................. 45

Digital Government: Electronic Voting .................................................................................................... 47

Digital Government: Engaging Citizens and Organizations ................................................................. 48

Smart Cities .................................................................................................................................................... 48

Trafficking in Persons ................................................................................................................................... 49

PILLAR 3: DIGITAL ECONOMY ....................................................................................... 52

Digital Transformation Challenges for Businesses ................................................................................ 53

e-Commerce .................................................................................................................................................. 57

Digital Financial Literacy .............................................................................................................................. 59

Online Shopping and Consumer Behavior .............................................................................................. 60

Payment Systems ........................................................................................................................................... 61

Cryptocurrencies .......................................................................................................................................... 63

ICT Industry and Digital Talent Pool ........................................................................................................ 64

ANNEX A. METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................... 68

Methodology................................................................................................................................................... 68

Analysis ............................................................................................................................................................ 70

Limitations ....................................................................................................................................................... 70

ANNEX B. DEFINITIONS ................................................................................................... 72

ANNEX C: LITERATURE .................................................................................................... 75

ANNEX D. LIST OF RELEVANT LAWS/POLICIES/REGULATIONS/STRATEGIES88

ANNEX E. RELEVANT DONOR PROJECTS ................................................................. 92

USAID.GOV DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) | i

EXHIBITS

Exhibit 1. Mobile network coverage in BiH, overlaid with population footprint (analysis performed

and maps produced by the DECA team in July 2022) ............................................................................................ 10

Exhibit 2. BiH internet usage and preference statistics .......................................................................................... 11

Exhibit 3. Fiber-optic cables in BiH, taken from the 2008–2025 FBiH and 2020–2025 RS spatial plans .... 12

Exhibit 4. Comparison of prices for different types of internet services in the Western Balkans

(2021) ................................................................................................................................................................................. 15

Exhibit 5. Financial literacy versus digital literacy versus media and information literacy.............................. 16

Exhibit 6. Percentage of people who feel comfortable with specific technologies .......................................... 18

Exhibit 7. Percentage of males and females that use the internet in Western Balkan countries, 2020...... 20

Exhibit 8. Connections between groups of media which have published the same disinformation at

least three times .............................................................................................................................................................. 32

Exhibit 9. Overview of trust providers in BiH (qualified electronic signatures) ............................................... 44

Exhibit 10. Digital technologies used by BiH companies ........................................................................................ 55

Exhibit 11. Areas in which support with digitalization is needed ......................................................................... 56

Exhibit 12. Use of e-commerce in BiH ....................................................................................................................... 59

Exhibit 13. Notice of the BiH Ministry of Finance about digital payment slips posted on a government

building ............................................................................................................................................................................... 62

Exhibit 14. Potential savings from an increase in the use of electronic payments in CBBH payment

systems (in USD) ............................................................................................................................................................. 63

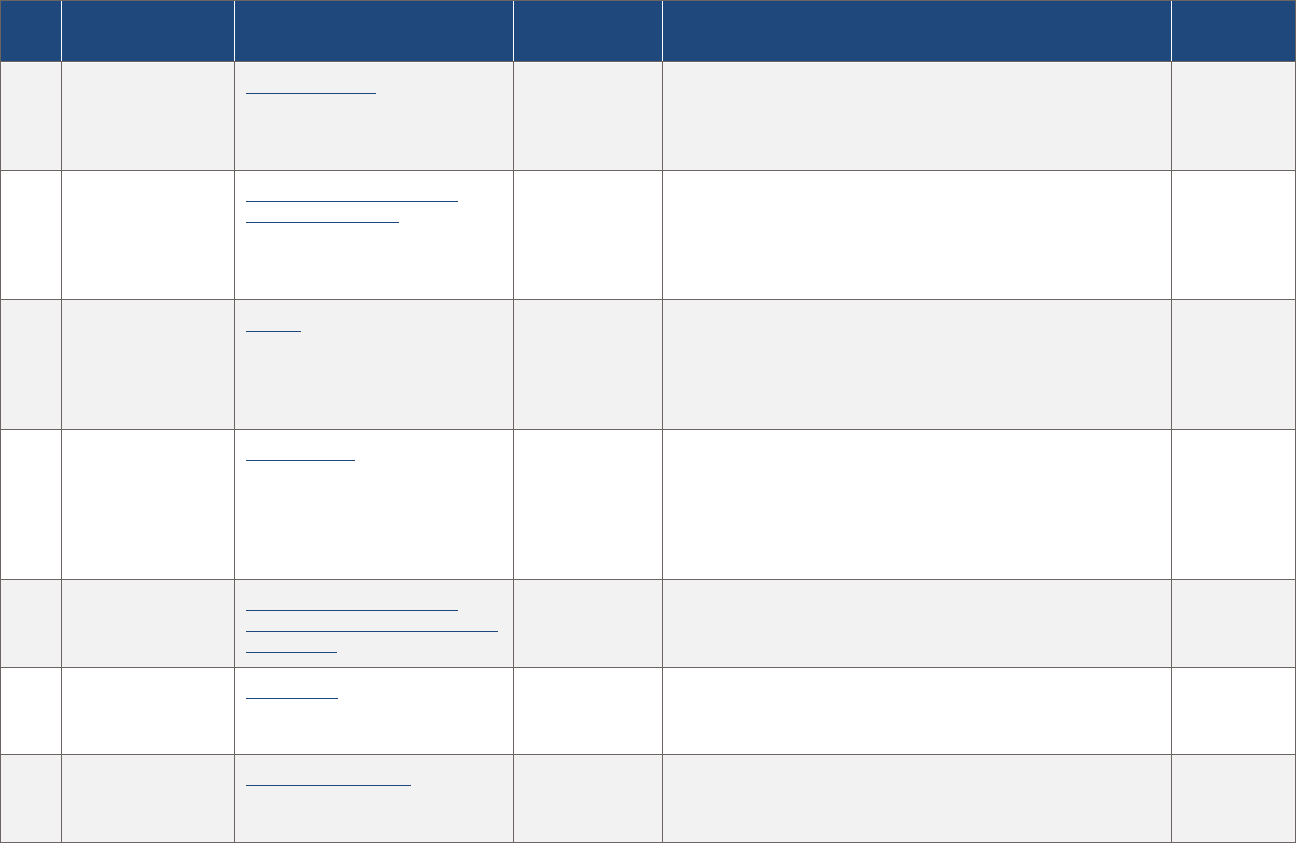

Exhibit A-1. Summary of key informant interviews ................................................................................................. 69

ii | DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) USAID.GOV

ACRONYMS

BAM Bosnia-Herzegovina Convertible Mark

BCX Balkan Crypto Exchange

BHRT Radio-Television of Bosnia and Herzegovina

BiH Bosnia and Herzegovina

BIRN Balkan Investigative Reporting Network

CA Certification Authority

CBBH Central Bank of Bosnia and Herzegovina

CDCS Country Development Cooperation Strategy

CERT Computer Emergency Response Team

CIDR Critical Infrastructure Digitalization and Resilience Project

CMDA Center for Media Development and Analysis

CRA Communications Regulatory Agency

CSIRT Computer Security Incident Response Team

CSO Civil Society Organization

DCX Digital Crypto Exchange

DECA Digital Ecosystem Country Assessment

DFC U.S. Government International Development Finance Corporation

DFS Digital Financial Services

DO Development Objective

EBRD European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

EC European Commission

Entso-E European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity

EU European Union

EUCOM United States European Command

FBiH Federation of BiH

FGDs Focus Group Discussions

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GDPR General Data Protection Regulation

GIS Geographic Information System

GIZ Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit

GSB Government Service Bus

GNP Gross National Product

GSMA Global System for Mobile Communications

ICT Information and Communication Technology

IDDEEA Agency for Identification Documents, Registers and Data Exchange

IFC-EMMAUS International Forum of Solidarity-Emmaus

IOM International Organization for Migration

IR Intermediate Result

ISOBiH Independent System Operator

ISP Internet Service Provider

IT Information Technology

USAID.GOV DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) | iii

ITA Indirect Tax Administration

ITU International Telecommunication Union

KIs Key Informants

KIIs Key Informant Interviews

LGU Local Government Unit

Mbps Megabits Per Second

MEASURE II Monitoring and Evaluation Support Activity

MIL Media and Information Literacy

MNO Mobile Network Operator

MOU Memorandum of Understanding

MVNO Mobile Virtual Network Operator

NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organization

NCMEC National Center for Missing and Exploited Children

NGO Non-governmental Organization

NIS Network and Information Security

NSCP-BiH National Survey of Citizens’ Perceptions in BiH

OPA Online Payment Platform

OSCE Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe

OTI Office of Transition Initiatives

PDPA Personal Data Protection Agency

PISA Program for International Student Assessment

POS Point of Sale

RCC Regional Cooperation Council

RS Republika Srpska

RTRS Radio-Television of the Republika Srpska

SEENPM Southeast Europe Network for the Professionalization of Media

SEPA Single Euro Payments Area

SERC State Electricity Regulatory Commission

SMS Short Message Service

UN United Nations

UNDP United Nations Development Program

UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund

USAID United States Agency for International Development

USD U.S. dollars

iv | DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) USAID.GOV

USAID.GOV DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) | 1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

A digital ecosystem includes the stakeholders, systems, and enabling environments that empower

people, companies, organizations, and governments to achieve their goals. To identify opportunities,

maximize benefits, and manage the risks associated with digital technology in the world’s rapidly evolving

digital landscape, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) designed the Digital

Ecosystem Country Assessment (DECA) as a reporting tool that will enhance the quality of inputs into

the planning and execution of USAID’s strategies and implementation of its activities. In late 2021,

USAID/Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) tasked its Monitoring and Evaluation Support Activity

(MEASURE II) to conduct a DECA for BiH. The assessment was guided by USAID’s strategic priorities in

BiH. USAID/BiH’s strategic priorities are defined in the 2020–2025 Country Development Cooperation

Strategy (CDCS) and include:

1. Improving the impact of inclusive citizen engagement by enhancing civil society

constituency connections, strengthening the information space, and increasing political and civic

leadership of BiH citizens, with specific focus on youth, women, and marginalized populations.

2. Strengthening governance effectiveness in targeted areas by addressing the problem of

high-level corruption in BiH, supporting reforms that are in line with European Union (EU)

regulations, and strengthening the protection of human rights.

3. Strengthening social cohesion by developing and empowering connections and building

solidarity among various groups in society, including civil society, the private sector, the

diaspora, and marginalized populations.

4. Boosting private-sector growth by supporting sectors that have the greatest growth

potential in BiH and increasing access to transparent financing.

Guided by these priorities, the DECA team assembled by MEASURE II collected and reviewed an

extensive list of relevant documents produced by USAID, its implementing partners, government

institutions and agencies, international organizations, academia, the non-governmental sector, and the

media. To extend the knowledge acquired through desk review, the DECA team organized, completed,

and analyzed data from 87 interviews and two focus groups with a total of 122 key informants. Finally,

the DECA team triangulated data obtained through desk review and interviews with data from the 2021

wave of the USAID/BiH’s National Survey of Citizens’ Perceptions in BiH (NSCP-BiH) to enrich the

understanding of BiH’s digital ecosystem and best inform assessment findings. Key DECA findings are

presented next.

KEY FINDINGS

Connectivity infrastructure in BiH is strong. Although all three primary mobile network operators

(MNOs) claim wide network coverage, enabling their consumer service throughout the country, BH

Telecom, HT Eronet, and M:Tel each predominantly serve a specific ethnic group in the area of the

country in which that group has a majority of residents. The internet service provider (ISP) market is

more diversified, especially with the growing presence of Telemach. However, the infrastructure that

the three dominant ISPs inherited from before the 1992–1995 war puts them in an advantageous

situation over new market competitors, especially since there is no infrastructure sharing among ISPs.

2 | DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) USAID.GOV

Despite this situation, internet infrastructure covers 82 percent of BiH territory, with 99.7 percent of

the population covered by at least a 2G mobile signal and 85.3 percent of residents covered by a 4G

signal. Implementation of 5G is still in the planning phase.

Despite strong connectivity infrastructure, BiH’s digitalization process continues to be stymied by

political paralysis. For example, BiH remains the only country in Europe without a state-level computer

emergency response team (CERT), the required central point of contact for collaboration with the

European Union on cybersecurity. Additionally, BiH lacks a common understanding and definition of

critical digital infrastructure. Whereas RS adopted a Law on Critical Infrastructure, political turmoil has

resulted in the absence of adequate legislation at the state and Federation of BiH (FBiH) levels.

Political paralysis also hinders the enabling environment for and uptake of digital signatures. The national

legislation on e-signatures is not aligned with the EU Acquis Communautaire. Although three certified

authorities are registered at the state level—Indirect Tax Authority; Agency for Identification

Documents, Registers and Data Exchange (IDDEAA); and a private company, Halcom D.D.—the use of

e-signatures remains modest. In RS, certificates for e-signature can also be obtained from the Ministry of

Scientific and Technological Development, Higher Education and Information Society. The Ministry plays

the role of certificate authority issuer, central coordinator of all certificates, and certificate inspector.

However, “trust services” (which include certification authorities) have not been regulated by EU

member states since 2016. In addition, according to the EU Regulation on electronic identification and

trust services for electronic transactions in the internal market (eIDAS Regulation), qualified certificate

providers should be recognized independently of the Member State where the Qualified Trust Service

Provider is established or where the specific qualified trust service is offered.

The lack of utilization and accessibilit

y of e-signatures has been identified as a key limitation to further

development and provision of e-services to citizens and the business community. Complex and slow

administration creates space for corrupt behavior, hinders the business enabling environment, and

contributes to citizens’ dissatisfaction with public services, all of which are identified to be among drivers

of high emigration from BiH. A highly skilled labor force continues to leave the country and information

technology (IT) professionals are not an exception. The IT sector is the most prosperous sector in BiH;

however, it faces an estimated labor force deficit of 6,000 workers that the current formal education

system cannot fill. Attraction and retention of digitally skilled workforce are the most challenging for

government institutions that cannot provide working conditions as good as the private IT sector does.

Furthermore, data on digital literacy among the general population are limited. Yet a perception that

youth are more digitally skilled compared to adults is common. Digital divides persist to the detriment

of older generations, women from rural areas, and Roma populations. Whereas access to and use of

digital technology by Roma stems mainly from poor economic conditions, women from rural areas face

a “triple divide” that includes digital, rural, and gender factors. This issue extends to the use of digital

financial services (DFS). Although use of DFS is low in general, women less often than men own a credit

card, use e-banking services, engage in e-commerce, and make payments online. The barriers to

expanding the uptake of DFS in BiH include its challenging topography, the prevalence of traditional

social and financial structures that depend on community- and cash-based networks, low trust in digital

platforms, low levels of financial inclusion, and low digital literacy in particular.

Another challenge to accelerating digital ecos

ystem development relates to digital media. The ability of

citizens to recognize misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation is limited and this state of

USAID.GOV DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) | 3

affairs is especially alarming given that media in BiH tend to be ethnically polarized and work of

investigative journalists is frequently obstructed. There is no systematic approach to addressing the

digital literacy deficit, and stakeholders including government agencies, MNOs, banks, media, and civil

society believe that it is not their responsibility to help consumers improve their critical thinking skills

and increase their awareness of how digital systems work. At the same time, violation of digital rights in

BiH is rising. Violations commonly include online intimidation, manipulation and propaganda in the digital

environment, and information security breaches. Media freedom and the safety of journalists are

hindered; however, both preventive and repressive institutional measures on political pressure,

intimidation, and harassment towards journalists are missing. There is a worrisome rise of threats and

violence against female journalists as well as online violence manifested through social networks and

internet portals.

4 | DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) USAID.GOV

INTRODUCTION

In 2020, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) adopted its first-ever Digital

Strategy

1

that aims to improve USAID development and humanitarian assistance outcomes through the

responsible use of digital technology and to strengthen the openness, inclusiveness, and security of

partner country digital ecosystems. A digital ecosystem includes the stakeholders, systems, and enabling

environments that empower people, companies, organizations, and governments to achieve their goals.

The Digital Strategy charts an agency-wide vision for development and humanitarian assistance in the

world’s rapidly evolving digital landscape.

The flagship initiative of the Digital Strategy is the Digital Ecosystem Country Assessment (DECA). The

DECAs will inform the development, design, and implementation of USAID’s strategies, projects, and

activities with regards to the digital landscape. It is a decision-making tool designed to help USAID

Missions identify opportunities, maximize benefits, and manage the risks associated with digital

technology.

In late 2021, USAID/Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) tasked its Monitoring and Evaluation Support Activity

(MEASURE II) to conduct a DECA for BiH.

ABOUT THIS ASSESSMENT

The DECA examines three broad areas to understand the opportunities and challenges in a country’s

digital ecosystem:

1. Digital Infrastructure and Adoption

2. Digital Society, Rights, and Governance

3. Digital Economy

The purpose of the DECA is to inform the development, design, and implementation of USAID’s

strategies, projects, and activities with regards to the digital landscape. It is a decision-making tool

designed to help USAID Missions identify opportunities, maximize benefits, and manage the risks

associated with digital technology.

In late 2021, USAID/BiH tasked its Monitoring and Evaluation Support Activity (MEASURE II) to conduct

a DECA for BiH. The BiH DECA was developed between December 2021 and September 2022. It

included desk research, consultations with USAID/BiH, and 87 key informant interviews (KIIs) and two

focus group discussions (FGDs) with a total of 122 participants from civil society, academia, the private

and public sectors, international development organizations, and USAID/BiH technical offices. Finally, the

DECA team triangulated data obtained through desk review and interviews with data from the 2021

wave of USAID/BiH’s National Survey of Citizens’ Perceptions in BiH (NSCP-BiH) to enrich the

understanding of BiH’s digital ecosystem and best inform assessment findings. Refer to Annex A for

more details on the applied methodological approach.

1

See https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/2022-05/USAID_Digital_Strategy.pdf.pdf.

USAID.GOV DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) | 5

Rather than act as an authoritative source on the country’s digital ecosystem, the DECA is intended to

be a rapid assessment of opportunities and challenges tailored to USAID’s programmatic priorities.

Thus, it may not cover all USAID/BiH program offices and activities in depth.

ROAD MAP FOR THE REPORT

This document provides extensive data and analysis on the status and trajectory of BiH’s digital

ecosystem.

Section 1 provides a summary of USAID/BiH’s priorities on which the DECA team focused while

researching the digital ecosystem in BiH.

Section 2 presents the key findings about BiH’s digital ecosystem. This section is organized into three

subsections by DECA pillar: (1) Digital infrastructure, access, and use; (2) Digital Society and

Governance; and (3) Digital Economy.

6 | DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) USAID.GOV

PILLAR 1: DIGITAL INFRASTRUCTURE AND ADOPTION

Digital infrastructure enables the flow of data and information between people and systems. Its key

aspects include network coverage, network performance, internet bandwidth, and spectrum allocation,

as well as security, interoperability, and telecommunications market dynamics. It is affected by

behavioral, economic, and social factors that influence the extent of digital literacy, affordability, and

adoption of digital solutions.

KEY FINDINGS

Three Mobile Network Operators (MNOs) with 5G are on the horizon: Overall,

connectivity infrastructure is strong, with 82 percent of the territory of BiH covered by mobile

networks. BiH has not yet introduced 5G, although BH Telecom started testing the technology in

2019. The lack of a national broadband strategy, as well as the lack of financial resources, have directly

affected the deployment of 5G and the overall growth in the information and communication

technology (ICT) sector.

Legacy of 4G licenses is a burden to MNOs: The 4G spectrum licenses granted to three MNOs

in 2017 included the requirement that they cover 90 percent of the country’s territory and

98 percent of its roads within five years, regardless of population density. These requirements were

unusual; it is more common for licenses to require a minimum percentage of population coverage.

The obligation has proved to be financially burdensome for MNOs and has slowed down the growth

trajectory of their businesses, while their counterparts in neighboring countries introduce 5G.

Pandemic-driven increase in demand: Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, citizens increasingly

turned to digital technologies, especially in areas such as education, shopping, and banking, among

others. This trend has implications for all levels of government. However, computer literacy data

show that 38.7 percent of the population ages 10 and above are computer illiterate, which indicates

that BiH still has significant room for improvement in enhancing the digital literacy of its citizens.

Although not documented, digital divides exist to the detriment of older generations, Roma, and

women from rural areas.

Cybersecurity concerns: There is no common understanding and definition of critical digital

infrastructure in BiH. Whereas Republika Srpska adopted a Law on Critical Infrastructure, political

turmoil has resulted in the absence of adequate legislation at the state and Federation of BiH levels.

Furthermore, BiH remains the only country in Europe without a state-level computer emergency

response team.

CONNECTIVITY INFRASTRUCTURE, SECURITY, INTEROPERABILITY, AND

COMPETITIVENESS

Since the 1992–1995 war, the telecommunications sector in BiH has been largely separated along ethnic

lines, as demonstrated by the market share of the country’s three largest MNOs. In FBiH, a majority of

consumers prefer either Sarajevo-based BH Telecom, which dominates in Bosniak majority areas, or

Mostar-based HT Eronet, which leads in Croat majority areas. In RS, Banja Luka-based M:Tel dominates

USAID.GOV DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) | 7

the market in the Serb-majority entity.

2

While no publicly available map of MNOs market share exists,

key informants (KIs) suggested it would follow the same boundaries as the regions with a majority of

one ethnic group. However, all three MNOs claim wide network coverage, thereby providing fair

service to their consumers throughout the BiH territory.

The ownership of the three MNOs varies. M:Tel was privatized in 2007, when it was sold to Telekom

Srbija,

3

the dominant fixed-line and mobile telephone provider in Serbia. The largest shareholder of both

BH Telecom and HT Eronet is the Government of FBiH, although it has different stakes in the two

companies. While the Government of FBiH holds 90 percent of BH Telecom shares,

4

it owns half of the

shares in HT Eronet, with the second largest company shareholder being Hrvatske Telekomunikacije

(39 percent),

5

the main telecom operator in Croatia. While it is possible to purchase a SIM card from

any of the three providers, the historical strength of the MNOs in the regions with a majority of one

ethnic group persists for various reasons, including the historical tendency for consumers of one

ethnicity to prefer the MNO controlled by members of their same ethnicity. Each group’s subsequent

loyalty to the MNO whose service to which they initially subscribed was prolonged by the long-standing

practice of offering lower prices for in-network calls. Until recently, MNOs that operated in multiple

countries offered cheaper calls between countries as part of their in-network service. For example, it

was cheaper to call a Telecom Serbia number from M:Tel than from other operators. However, on

July 1, 2019, an agreement was signed to reduce roaming fees affecting all MNOs operating across the

Western Balkans.

6

While there are only three MNOs, the internet service provider (ISP) market is more diversified. In

addition to BH Telecom, M:Tel, and HT Eronet, which provide mobile network services but are also the

primary means of internet access for a majority of BiH citizens, there are several ISPs that compete for

market share in the telecommunications sector, one of the most profitable sectors in BiH. The total

revenue generated by the sector in 2020 was more than 793 million USD, which equaled 3.54 percent of

BiH’s gross domestic product (GDP).

7

Although Telemach strengthened competition among ISPs—

especially in FBiH—BH Telecom, HT Eronet, and M:Tel continue to dominate the market.

The total number of mobile network subscriptions (3.8 million as of December 2021)

8

exceeds the total

population of BiH,

9

possibly indicating that people have more than one SIM card.

10

Although the number

2

International Trade Administration. (2021). BiH – Telecommunication Industry. https://www.trade.gov/country-

commercial-guides/bosnia-and-herzegovina-telecommunications-industry

3

M:Tel. Ownership Structure. https://mtel.ba/n363/Investors#tab-three

4

The Sarajevo Stock Exchange. Share issue profile: BH Telecom DD Sarajevo.

http://www.sase.ba/v1/Tr%C5%BEi%C5%A1te/Emitenti/Profil-emitenta/symbol/BHTSR

5

The Sarajevo Stock Exchange. Share issue profile: JP HT DD Mostar. http://www.sase.ba/v1/en-us/Market/Issuers-

Securities/Issuer-profile/symbol/HTKMR

6

Regional Cooperation Council. (2021). Agreement on the price reduction of the roaming services in public

mobile communication networks in the Western Balkans Region.

https://www.rcc.int/download/docs/FINAL%20RRA2%20SIGNED.pdf/25c8b674d235cf5bc19894a8a24fbd6b.pdf

7

BiH Communication Regulatory Agency. (2021). Annual report of the Communications Regulatory Agency for 2020.

https://docs.rak.ba//documents/f8910d22-e538-4b11-9b21-4f7cfd0e0b88.pdf

8

Mobile network subscriptions reflect the number of prepaid and postpaid SIM cards active during the past three

months.

9

BiH Communications Regulatory Agency. (2021). Annual Report. https://docs.rak.ba//documents/fb41882e-cbe4-

4e8f-8efa-fe45a9376971.pdf

10

Data on SIM cards owned by tourists or members of the BiH diaspora community are unavailable. Thereby, it is

impossible to assess the extent to which these (potential) users contribute to the total number of mobile network

8 | DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) USAID.GOV

of postpaid subscriptions has increased over the past ten years, the number of active, prepaid SIM cards

remains almost three times higher (1 million postpaid cards vs. 2.8 million prepaid cards).

11

In April 2019, the Communications Regulatory Agency of BiH (CRA) issued 4G licenses to the three

MNOs with a validity period of 15 years and a

requirement to commence 4G services within one

month of the award.

12

Both 3G and 4G were

introduced in BiH significantly later than in

neighboring countries, mainly because CRA took a

long time to issue licenses for MNOs.

While there is competition in the country, the

current makeup of players is not likely to change.

BH Telecom, HT Eronet, and M:Tel are the only

licensed MNOs. BH Telecom is the market leader

in mobile network subscribers (43 percent of

market share), followed by M:Tel (35 percent), and

HT Eronet (21 percent). Together, these companies also control 81 percent of fixed-line connections.

13

Based on commercial agreements with the three licensed MNOs, BiH citizens may also use mobile

network services provided by mobile virtual network operators (MVNOs) Dasto Semtel, Logosoft,

Novotel, and Haloo.

14,15

However, the combined market share of these four operators does not exceed

one percent.

While the Law on Communications of BiH

16

allows MNOs to share infrastructure, the companies mostly

choose not to, because they consider the location and extent of their towers to be a primary means by

which they can outperform their competitors. This is true, even though the MNOs could have saved

significant resources while fulfilling the land coverage requirements stipulated in their 4G spectrum

licenses. According to KIs, the cooperation between MNOs is limited mostly to humanitarian relief

activities, through which they enable consumers to make donations by text message. Although setting up

a unique number for collecting monetary donations can be done to support humanitarian causes, it

entails significant costs; however, these services are not tax deductible for the customer.

17,18,19

The

costs associated with making humanitarian donations over the phone have led citizens to organize an

initiative to abolish value-added tax (VAT) and fees associated with humanitarian calls. However, changes

in the legislative framework were never made.

subscriptions in BiH.

11

BiH Communications Regulatory Agency. (2021). Annual Report. https://docs.rak.ba//documents/fb41882e-cbe4-

4e8f-8efa-fe45a9376971.pdf

12

ITU Office for Europe. (2020). 5G Country Profile – Bosnia and Herzegovina

13

BiH Communications Regulatory Agency. (2021). Annual Report. https://docs.rak.ba//documents/fb41882e-cbe4-

4e8f-8efa-fe45a9376971.pdf

14

Ibid.

15

Two out of four MVNOs are owned by MNOs—specifically, M:Tel acquired Logosoft in 2017, and HT:Eronet

founded Haloo d.o.o. in 2020.

16

Official Gazette of BiH, No. 31/03, 98/12.

17

M:Tel. (2022). Price Overview: August 2022. https://mtel.ba/Binary/1772/cjenovnik.pdf

18

BH Telecom. (2021). Price List of Services in Domestic and International Traffic of BH Telecom.

https://www.bhtelecom.ba/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Cjenovnik-V014.pdf

19

HT Eronet. Humanitarian telephone numbers. https://www.hteronet.ba/upoznajte-nas/humanitarni-telefoni-s127

Lack of a Broadband Strategy

Although the draft version of a strategy for the

development of broadband access in BiH for the

period 2019-2023 exists, it has not yet been

adopted. KIs did not provide comprehensive

reasoning on what may be preventing the

adoption of the strategy. This makes BiH the only

country in the neighborhood that lacks a

broadband strategy.

USAID.GOV DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) | 9

MOBILE COVERAGE

A current map of mobile coverage in BiH is not available; however, data provided by CRA and

international agencies, including the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), show that mobile

penetration (the number of accounts per person) reached 106.7 percent in 2021. In the same year,

20

96 percent of the population was covered by a 3G mobile network (UMTS); 82 percent, by a 4G mobile

network (LTE).

21

According to KIs, CRA is in the process of mapping the country’s broadband infrastructure.

The result of this process will be a map with geolocated infrastructure that will serve, per an EU

request, as the primary source of telecommunications infrastructure information for the country.

Based on Global System for Mobile Communications (GSMA) network coverage maps

22

and geographic

information system (GIS) analysis performed by the DECA team, it is evident that 96.7 percent of the

territory of BiH is covered by 2G signals, whereas some smaller areas in the country are not covered by

any signal of any mobile network (Exhibit 1). Whereas 3G covers 80.5 percent of the territory of BiH,

only 48.9 percent of the territory is covered by a 4G signal. The data the DECA team obtained through

GIS analysis using the GSMA network coverage and Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX) 2020

population tallies

23

also indicate that 99.7 percent of the BiH population has access to a 2G signal. In the

case of 3G coverage, this percentage is slightly lower (97.7 percent), while 85.3 percent of the

population has 4G access. As the maps in Exhibit 1 illustrate, 4G is most commonly used in densely

populated areas, leaving rural areas without its benefits.

Although BiH has not yet introduced 5G, BH Telecom started testing 5G technology in 2020, with

testing continuing into 2022. However, according to the ITU, the lack of a national broadband strategy is

“one of the most pressing issues for the development of broadband in the country in terms of market

competitiveness and growth in the ICT sector.” It has slowed the introduction of 5G technology in

the country.

24

20

BiH Communication Regulatory Agency. (2021). 2021 Annual Report: Communications Regulatory Agency.

https://docs.rak.ba//documents/92647e3b-3b39-40e3-88b0-5324ccec753f.pdf

21

In accordance with International Telecommunication Union (ITU) data practices, the data were taken from the

operator that reported the highest percentage of GSM, UMTS, and LTE network coverage. However, GSMA data

show that 4G coverage in BiH is only at 23 percent.

22

GSM Association. (2021). Network Coverage Maps. https://www.gsma.com/coverage/.

23

The Humanitarian Data Exchange. Bosnia and Herzegovina – Population Counts.

https://data.humdata.org/dataset/worldpop-population-counts-for-bosnia-and-herzegovina

24

Halimić, E. (2021, October 9). The blockade of institutions is hampering the introduction of the 5G network in

BiH. Dnevni avaz. https://avaz.ba/vijesti/bih/687426/ponovo-kasnimo-za-regionom-i-evropom-blokada-institucija-

koci-i-uvodenje-5g-mreze-u-bih

10 | DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) USAID.GOV

Exhibit 1. Mobile network coverage in BiH, overlaid with population footprint (analysis performed and

maps produced by the DECA team in July 2022)

Note: The average population density in BiH (state level) is between 66 and 69 people per square kilometer. The highest

population density values are in the Sarajevo Canton (more than 6,500 people per sq. km), while the lowest values (less than 10

people per sq. km) are in the southwest areas in Canton 10.

INTERNET USE AND CONSUMER PREFERENCES

According to data from the ITU and the BiH Agency for Statistics, 73.2 percent of the population in BiH

use the internet,

25

and about the same percentage of households have internet access at home.

26

Households in urban areas are more likely to have internet access (75 percent) compared to households

in rural areas (71 percent).

27

The most common reasons for private internet use include online and

video calls, text messaging through online tools, and participation in social networks.

28

The most

common reason people choose not to pay for internet service is that they do not perceive the benefits

of doing so. Of those who chose not to pay for internet service because they did not perceive the

25

ITU. (2021). Connectivity in education: Status and recent developments in nine non-European Union countries.

https://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-d/opb/phcb/D-PHCB-CONN_EDUC-2021-PDF-E.pdf

26

Agency for Statistics of BiH. (2021). Use of information and communication technologies in Bosnia and

Herzegovina. https://bhas.gov.ba/data/Publikacije/Bilteni/2021/IKT_00_2020_TB_1_BS.pdf

27

Ibid.

28

Ibid.

USAID.GOV DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) | 11

benefit, 77 percent of respondents were adults and 33 percent were youth.

29

The next two most

common reasons for not having regular access to the internet are the lack of devices (33 percent of

adults and 31 percent of youth) and the cost of internet access (17 percent of adults and 33 percent of

youth). See Exhibit 2 for more details.

World Bank data reveal that fixed broadband subscriptions in BiH increased from 27 in 2000 to 770,624

in 2020.

30

Although the number of ISPs has declined over the past five years, the number of internet

subscribers has increased over the past ten years. In 2020, 60 ISPs operated in BiH.

31

Compared to the

previous year, the operators improved their offers by introducing new services and improving the ease

of using existing services. However, the operators face numerous problems in network expansions.

Exhibit 2. BiH internet usage and preference statistics

Source: National Survey of Citizens’ Perceptions in BiH (2021).

BiH still has a low rate (5.84 percent) of subscribers using fiber to the home (FTTH). The NSCP-BiH

found that digital subscriber line (DSL) is the most common means of connection for internet users in

rural areas (41.8 percent) and that cable is the most popular form of internet access for urban dwellers

(49.3 percent).

32

The deployment of fiber-optic technologies is still very slow, and it is characterized by

unequal conditions for the installation within the country, lack of coordination between operators, and

lack of a national broadband strategy. Complex construction permitting processes can also be linked to

slow fiber-optic implementation, especially in connecting the last segment of the last mile. In addition,

Speedtest Global Index ranks BiH 109th of 178 economies assessed in fixed broadband with a speed of

22.79 Megabits per second (Mbps). The global average is 59.75 Mbps.

33

29

USAID. (2022). 2021 National Survey of Citizens’ Perceptions in BiH (NSCP-BiH).

30

World Bank data. Fixed broadband subscriptions.

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.BBND?locations=BA

31

BiH Communication Regulatory Agency. (2021). Annual report of the Communications Regulatory Agency for

2020. https://docs.rak.ba//documents/f8910d22-e538-4b11-9b21-4f7cfd0e0b88.pdf

32

USAID. (2022). 2021 National Survey of Citizens’ Perceptions in BiH (NSCP-BiH).

33

Ookla. (2021). Speedtest Global Index. https://www.speedtest.net/global-index

12 | DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) USAID.GOV

Exhibit 3, created by the DECA team based on the synthesis of data from the spatial plans of FBiH and

RS, shows that almost all cities and towns in both entities are connected by the existing or planned

fiber-optic cable routes, which indicates that BiH, in planning and technical terms, has an adequate basis

for the development and improvement of fiber-optic infrastructure. It is worth noting that while other

maps of telecommunication infrastructure in BiH, such as the ITU’s Interactive Transmission Map,

34

show microwave networks crisscrossing the country, the microwave network was established to

facilitate communication between critical government agencies, including the police, security organs, and

others. The network is used neither by companies for retail connectivity services nor by MNOs or ISPs

to provide internet access to consumers.

Exhibit 3. Fiber-optic cables in BiH, taken from the 2008–2025 FBiH and 2020–2025 RS spatial plans

PROSPECTS FOR EXPANDED COVERAGE

Ethnic politics, market regulations, anticompetitive behavior, and corruption all affect the prospects for

expanding telecommunication infrastructure in BiH. Regulations governing network expansion give

municipalities the authority over the administrative procedures governing the construction of

telecommunication cables, as well as the ability to set utility fees. This, however, may provide space for

corrupt behavior or may be used as a means for reaching political goals. For example,

34

ITU. Interactive Transmission Map. https://www.itu.int/itu-d/tnd-map-public/

USAID.GOV DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) | 13

telecommunication companies may encounter hurdles in obtaining construction permits for the

completion of their infrastructure projects, because political parties who have decision-making power in

the local government unit (LGU) may be connected with, or may support, their competitors.

Additionally, about 12 percent of firms in BiH are asked or expected to give gifts or informal payments

when requesting a construction permit.

35

Even without corrupt behavior, however, LGUs are

characterized by slow and inconsistent procedures, making it challenging for MNOs and ISPs to

efficiently pursue national expansion plans.

36

The challenge for network expansion is exacerbated by the lack of infrastructure-sharing possibilities,

meaning that new market entrants are forced to build their own networks and are not allowed to lease

existing infrastructure, even if that infrastructure is not used by other companies in the market. This

situation benefits the BiH’s three MNOs that inherited infrastructure built before the breakup of

Yugoslavia.

37

Either inherited or built, each telecommunications operator maintains detailed information

on its own infrastructure. This information is, however, not regularly shared with relevant stakeholders.

Lack of transparency and information sharing raises security concerns as a number of incidents happen

due to lack of familiarity with the exact location of the telecommunication infrastructure. For example,

underground cables are commonly damaged during excavation by construction companies that are not

informed of the location or even the vicinity of underground cables.

Bilateral donors are ready to support digitalization processes in BiH. Annex E provides a list of ongoing,

digital-related projects supported by donors and international financial institutions in BiH. Expanding

connectivity to rural areas is one of the issues that donors are willing to support; however, they have failed

to find interested and motivated partners within government institutions. Meanwhile, the interviewed

government officials are concerned that without government intervention and support for initiatives that

seek to expand affordable broadband access throughout the country, operators inevitably will choose to

invest in higher earning locations and leave behind BiH’s marginalized locations and populations.

Aside from the BiH government’s potential role, there are other internet access initiatives. One

example is the joint Giga initiative in BiH, as part of which the United Nations Children’s Fund

(UNICEF), together with the ITU, aims to connect the country’s schools to the internet.

38

As a first

step, UNICEF mapped all of BiH’s public schools and found that almost every third school in BiH does

not have access to the internet.

39

It found that, at that cantonal level, the percentage of schools without

internet access can be as high as 40 percent.

40

35

World Bank Group. (2019). Enterprise Surveys: Bosnia and Herzegovina 2019. Country Profile.

https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/content/dam/enterprisesurveys/documents/country/Bosnia-and-Herzegovina-

2019.pdf

36

According to the World Bank data, it takes 103 days to issue a construction permit in BiH. Source: World Bank

Group. (2019). Enterprise Surveys: Bosnia and

Herzegovina 2019. Country Profile:

https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/content/dam/enterprisesurveys/documents/country/Bosnia-and-Herzegovina-

2019.pdf

37

Hosman, L., & Howard, P. N. (2010). Information Policy and Technology Diffusion: Lessons from Bosnia, Croatia,

Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia.

https://www.academia.edu/2668555/Information_Policy_and_Technology_Diffusion_Lessons_from_Bosnia_Croatia

_Macedonia_Montenegro_Serbia_and_Slovenia

38

Giga: Global initiative to

connect every school to the internet by 2030.

https://giga.global/about-us/

39

UNICEF. (2022). Mapping ICT resources

in primary and secondary schools

in BiH: Results.

40

Ibid.

14 | DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) USAID.GOV

AFFORDABILITY

Approximately 17 percent of BiH citizens who do not have regular internet access say the main reason

is cost. The affordability variable from the GSMA Mobile Connectivity Index was 52.0 for BiH, which

means that compared to the neighboring countries, BiH, along with North Macedonia (49.4), has the

highest mobile data prices in the Western Balkans.

41

The affordability variable shows the availability of

mobile services and devices at price points that reflect the level of income across a national population.

Comparatively, the ITU uses five different price benchmarks, or “baskets,” to compare prices for

different types of internet services. These are (1) fixed broadband basket, (2) data-only mobile

broadband basket, (3) mobile data and voice low-consumption basket, (4) mobile data and voice high-

consumption basket, and (5) mobile cellular low-usage basket. The ITU data show that in 2021, BiH had

the second cheapest, data-only mobile broadband basket

42

and mobile data and voice high-consumption

basket

43

in the Western Balkans and was above the Western Balkan average cost of the fixed broadband

41

GSMA Mobile Connectivity Index (2019).

https://www.mobileconnectivityindex.com/?search=crp#year=2019&zoneIsocode=MKD

42

The cheapest plan provides at least 2GB of high-speed data (≥256Kbit/s) over a 30-day (or 4-week) period from

the operator with the largest market share.

43

The cheapest plan provides at least 140 minutes of voice, 70 SMS, and 2 GB of high-speed data (≥256Kbit/s) over

a 30-day (or 4-week) period from the operator with the largest market share.

USAID.GOV DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) | 15

basket,

44

mobile data and voice low-consumption basket,

45

and mobile cellular low-usage basket.

46,47

Exhibit 4 shows a more detailed comparison of prices for different types of internet services in the

Western Balkans.

Exhibit 4. Comparison of prices for different types of internet services in the Western Balkans (2021)

BIH CROATIA MONTENEGRO

NORTH

MACEDONIA SERBIA

WESTERN

BALKANS

(AVERAGE)

Fixed broadband basket

(5GB)

2.30 0.64 2.04 3.52 2.66 2.23

Data-only mobile

broadband basket (2GB)

1.35 0.71 2.26 1.95 1.48 1.55

Mobile data and voice

low-consumption basket

(70min+20sms+500MB)

2.03 0.57 2.26 2.35 0.78 1.60

Mobile data and voice

high-consumption basket

(140min+70sms+2GB)

2.54 0.71 2.79 3.31 2.58 2.39

Mobile cellular low-usage

basket (70min+20sms)

2.03 0.57 2.26 2.35 0.78 1.60

Note. All prices are shown as a percentage of GNI per capita

Source: ITU.

In April 2019 Albania, BiH, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia agreed to reduce

roaming charges for mobile subscribers traveling within the region. CRA published its decision on

May 12, 2021, that additional roaming charges for calls, SMS, and MMS would not be charged. Now

these countries are negotiating reduced data roaming tariffs with the EU because the roaming

agreements did not include data. This means that consumers still need to track their data usage while

using highly popular, over-the-top services such as WhatsApp and Viber while traveling abroad.

DIGITAL LITERACY

Digital literacy is “the ability to access, manage, understand, integrate, communicate, evaluate, and create

information safely and appropriately through digital devices and networked technologies for participation

in economic, social, and political life.”

48

The concept overlaps with financial literacy and with media and

44

The cheapest plan provides at least 5GB of high-speed data (≥256Kbit/s) over a 30-day (or 4-week) period from

the operator with the largest market share.

45

The cheapest plan provides at least 70 minutes of voice, 20 SMS, and 500MB of high-speed data (≥256Kbit/s)

over a 30-day (or 4-week) period from the operator with the largest market share.

46

The cheapest plan provides at least 70 minutes of voice and 20 SMS (in predetermined on-net/off-net/fixed

ratios) over a 30-day (or 4-week) period from the operator with the largest market share.

47

ITU. (2022). ICT Price Baskets (IPB). https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Dashboards/Pages/IPB.aspx

48

USAID. (2022). Digital Literacy Primer.

https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/2022-05/USAID_Digital_Literacy_Primer.pdf

16 | DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) USAID.GOV

information literacy (MIL). (See Exhibit 5.) MIL is discussed in detail under Pillar 2, and more information

on financial literacy is presented under Pillar 3.

Exhibit 5. Financial literacy versus digital literacy versus media and information literacy

Strengthening digital literacy in BiH is hindered by a number of factors. Comprehensive data on the state

of digital literacy of BiH citizens are not available as there has been no extensive or regular research on

the topic to date. Several different types of organizations in BiH have a stake in citizens’ access and

ability to use digital communications technology and have the capacity to influence or address digital

literacy in the country. These include MNOs and ISPs; education institutions; government agencies;

banks; traditional media; NGOs; advertisers; online retailers; and social media. However, the research

for this report found a consistent view by stakeholders that digital (as well as media and information)

literacy was someone else’s responsibility. Repeatedly, DECA KIs, including interviewed government

officials, civil society representatives, and informants from academic and media sectors, did not

acknowledge responsibility for contributing to improved digital literacy among BiH society and said it is

someone else’s responsibility to improve citizens’ digital literacy. Finally, there is a lack of a common

understanding of what digital literacy refers to, especially given that any definition of the concept

inevitably must adapt to emerging technologies and concepts, including the evolving challenges of online

misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation.

49

The last census, which included only basic concepts of computer literacy, was conducted in 2013.

50

Otherwise, proxy indicators (related to service availability and use) including affordability, consumer

readiness, and content and services are the only data available that can be used to indirectly assess

digital literacy.

51

49

The U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency published “Mis, Dis, Malinformation,” a guide for

these concepts. https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/publications/election-disinformation-toolkit_508_0.pdf

50

BiH Agency for Statistics. (2013). Census of population, households and dwellings in BiH: Final results.

https://www.popis.gov.ba/popis2013/doc/RezultatiPopisa_BS.pdf

51

GSMA Mobile Connectivity Index. (2019).

USAID.GOV DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) | 17

Given the lack of regular local research on the state of digital literacy in BiH society, data from

international organizations offer some insights. For example, according to the ITU, 37 percent of BiH

citizens have basic IT skills,

52

and only 2 percent of individuals have advanced skills.

53

Men more often

than women have basic digital skills (19 percent of men compared to 14 percent of women); however,

women more often than men have advanced digital skills

54

(10 percent of women compared to

6 percent of men).

55

Citizens are also active users of social media networks, with 55 percent of the total

population in January 2021 identified as active on social media, according to the Digital Global portal.

56

However, usage of social media platforms does not necessarily predict the ability to use functionalities

such as creating and sharing media, organizing contacts, etc. (analogous skills that the ITU metric may

use to categorize individuals levels of digital literacy). For example, for the majority of young people in

BiH (83.5 percent), using the internet is the most important activity during their free time; it is even

more important than going out with friends or playing sports.

57

Yet according to 2019 Eurostat data,

BiH is among worst performing countries in Europe when digital skills of youth are assessed: Only

57 percent of young people ages 16 to 24 have basic or above-basic digital skills.

58

This indicates that the

frequency of internet use among youth does not predict how digitally skilled they are, which conforms

with the concern expressed by interviewed NGOs related to citizens’ ability to recognize and

comprehend the implications of misuse of technology. They believe that BiH society is unprepared for

negative uses and the impacts they cause.

However, the majority of BiH citizens feel confident in using different digital devices, including desktop

computers, laptops, smartphones, and tablets. As found by the 2021 wave of the NSCP-BiH and

confirmed by the majority of KIs, youth tend to be more confident in using digital devices compared to

adults. At the same time, although the majority of KIs do not think there are notable differences

between the digital literacy of men and women in BiH, women self-reported lower levels of confidence

in using a desktop computer, laptop, or tablet compared to their male counterparts (Exhibit 6).

59

https://www.mobileconnectivityindex.com/#year=2019&zoneIsocode=BIH&analysisView=BIH

52

In the ITU research mentioned on this page, the ITU defines basic skills as “… the highest value among the

following four computer-based activities: copying or moving a file or folder; using copy and paste tools to duplicate

or move information within a document; sending emails with attached files; and transferring files between a

computer and other devices.”

53

ITU. (2019). Digital Development dashboard: Bosnia and Herzegovina.

https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/DDD/ddd_BIH.pdf

54

The ITU defines advanced (ICT) skills as “the value for writing a computer program using a specialized

programming language.”

55

Agency for statistics of BiH. (2021). Men and Women in BiH.

https://bhas.gov.ba/data/Publikacije/Bilteni/2022/FAM_00_2021_TB_1_BS.pdf

56

Kemp, S. (2020). Digital 2020: Bosnia and Herzegovina. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-bosnia-and-

herzegovina

57

Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. (2019). Youth Study Bosnia and Herzegovina 2018/2019. https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/id-

moe/15262.pdf

58

Eurostat. Individuals’ level of digital skills (until 2019). Last update: March 30, 2022.

https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do

59

USAID. (2022). 2021 National Survey of Citizens’ Perceptions in BiH.

18 | DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) USAID.GOV

Exhibit 6. Percentage of people who feel comfortable with specific technologies

Source: National Survey of Citizens’ Perceptions in BiH (2021).

Experts commonly lamented the lack of systematic digital literacy training in the country. While there is

some digital literacy training for schoolchildren, it is not built into the school curricula so that students

start young and proceed through increasingly advanced concepts during succeeding years of school. For

example, computer science is a school subject taught starting in first grade in Sarajevo Canton primary

schools. In other FBiH cantons, as well as in RS, computer science is not taught until the fifth or sixth

grade. In September 2021, however, RS launched a program called “Digital World” that provides basic

digital literacy training to all second graders.

60

In this course, students are taught how to recognize and

respond to malicious behavior on the internet.

61

However, there is no follow-on program for the

remaining grades. Even if they provide formal

education connected to digital literacy, schools in

BiH often lack the necessary equipment that

would ensure high-quality teaching. According to

the 2018 Program for International Student

Assessment (PISA), only one-third of schools in

BiH have a sufficient number of digital devices or

appropriate teaching software available in school.

Additionally, every second school in BiH lacks

sufficient internet speed to support online

learning.

62

60

Pedagogical Institute of RS. Digital World. https://www.rpz-rs.org/922/rpz-

rs/Nastavni/programi/za/nastavni/predmet/Digitalni/svijet/za/II/razreda/osnovne/skole

61

Srpska Café. (2021, July 29). Digitalni svijet: Učenici drugog razreda osnovne škole dobijaju novi predmet.

http://srpskacafe.com/2021/07/digitalni-svijet-ucenici-drugog-razreda-osnovne-skole-dobijaju-novi-predmet/

62

OECD. (2019). 2018 Program for International Student Assessment (PISA): Bosnia and Herzegovina. Student

Performance – Resources for education.

https://gpseducation.oecd.org/CountryProfile?primaryCountry=BIH&treshold=5&topic=PI#:~:text=In%20reading%2

0literacy%2C%20the%20main,30%20points%20higher%20for%20girls).

USAID/BiH supports e-learning and blended

learning in BiH

USAID/BiH, as part of its Strengthening Social

and Health Protection in Response to the

COVID-19 Pandemic in BiH Activity (2021 –

2023), implemented by UNICEF, works on

enhancing the capacities of schools to provide quality

e-learning and blended learning. The Activity focuses

on helping children acquire knowledge, skills, and

values, and access and operate in digital environment

safely and effectively. This includes ability to critically

evaluate information and communicate safely,

responsibly, and effectively using digital technology

and content.

USAID.GOV DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) | 19

While leadership over the trajectory and fate of digital literacy in BiH remains unclear, a majority of KIs

said digital transformation in BiH has advanced as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic

not only required families in BiH to quickly transition to remote work and learning but also encouraged

them to turn to online shopping and banking. KIs reported that the need to use digital tools in the

absence of other alternatives strengthened the digital literacy of the BiH population, although no

research has been conducted to confirm this.

THE DIGITAL DIVIDE

Despite the generally strong connectivity infrastructure, digital

technology is not equally accessible or used by all members of

BiH society. A digital divide is evident among urban and rural

locations. Households from urban areas are more likely to

have a computer compared to households in rural areas

(65.6 percent versus 60.6 percent, respectively).

63

The same

applies to having internet access: 77.8 percent of households

in urban areas have internet access compared to 73.8 percent

of households in non-urban areas.

64

A digital divide is especially

visible among households with different monthly net incomes.

Whereas 93.4 percent of households earning more than 480

USD (900 BAM) a month own a computer and 97.1 percent

have access to the internet, only 47.1 percent of households with earnings less than 480 USD have a

computer, and only 63.8 percent of these households have internet access.

Socio-economic barriers limiting access to technological change and development are most evident

among Roma households. Roma are the largest minority group in BiH; the total population is 12,896,

according to the 2013 Census data.

65

However, estimates of the size of the Romani population range

between 40,000 and 75,000,

66

although these data are not officially confirmed. Roma in BiH face

cumulative and systematic discrimination and social exclusion,

67

with the digital environment being only

part of a more comprehensive issue to which this national minority group is subjected. For example,

there are ten Roma settlements around the country that lack access to electricity, let alone the

internet.

68

The main reason for the lack of access to electricity in these settlements is the inability of

households to cover electricity costs. Aside from these ten settlements, a large number of Roma

households struggle or cannot afford to pay for high electricity costs. Furthermore, strengthening the

63

Agency for Statistics of BiH. (2022). Use of Information and Communication Technology in BiH: 2021.

https://bhas.gov.ba/data/Publikacije/Bilteni/2022/IKT_00_2021_TB_1_HR.pdf

64

Ibid.

65

Agency for Statistics of BiH. (2013). Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in BiH - Final Results.

https://www.popis.gov.ba/popis2013/doc/RezultatiPopisa_BS.pdf

66

Romani Early Years Network (REYN). REYN Bosnia and Herzegovina. Access on: August 26, 2022.

https://reyn.eu/reynnationalnetworks/reyn-bosnia-and-herzegovina/

67

Civil Right Defenders. (2017). Roma in Bosnia and Herzegovina. https://crd.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/The-

Wall-of-Anti-Gypsyism-Roma-in-Bosnia-and-Herzegovina.pdf

68

According to DECA KI, the following Roma settlements do not have access to electricity: (i) Rakovica

(Municipality of Ilidza), (ii) Moscanica (Municipality of Stari Grad Sarajevo), (iii) Podhranj (Municipality of Gorazde),

(iv) Radimlja (Municipality of Stolac), (v) Prutace (District Brcko), (vi) Dolovi (Municipality of Zavidovici),

(vii) Hrastovi (Municipality of Kiseljak), (viii) Poljice (Municipality of Lukavac), (ix) Kupresani (Municipality of Jajce),

(x) Zivinice (Municipality of Zivinice).

The digital divide explained

The digital divide is the distinction

between those who have access and

can use digital products and services

and those Who are excluded. There

are often overlapping digital divides

that stem from inequities in literacy,

cost, social norms, or availability of

relevant content. Digital divides may

be associated with gender, economic

status, geography, and age among

other factors.

20 | DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) USAID.GOV

digital skills of Roma children is hindered by the lack of attainment of formal education. Although about

70 percent of Roma children enroll in the primary and secondary schools, less than half of them

complete the compulsory education.

69

As the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the digital

transformation process across BiH, it broadened the digital

divide between Roma and other children. Roma children

could not afford devices and internet access, and they

lacked spaces where they could learn; therefore, they were

not able to attend online classes.

70

The situation is somewhat better when the digital divide is

assessed from a gender perspective. Approximately

79 percent of men and 73 percent of women between the

ages of 16 and 74 years old used the internet in 2021.

71

However good this may seem, when compared to the

neighboring countries, BiH has the lowest percentage of

women using the internet and is the second-worst

performer (together with Montenegro) when the percent

of men using the internet is assessed (Exhibit 7).

Although both men and women use the internet mostly to

make phone and video calls, send messages, and use social

networks, men, more often than women, engage in online

sale of goods and services (61.2 percent of men versus

38.8 percent of women), use internet banking (57.6 percent

of men versus 42.4 percent women), and play or download

games (56.5 percent of men versus 43.5 percent of

women).

72

These disparities conform with the gender

equality issues in BiH, including that men, more often than

women, have bank accounts

73

and spend less time than

women doing childcare and household work.

74

Although

there are no official data, experts believe that women from

rural areas are more marginalized than women from non-

rural areas when the use of ICT is assessed. According to

the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United

Nations, women in rural areas face a “triple divide” that

69

UNDP. The World Bank. EU. (2018). Roma at a Glance: Bosnia and Herzegovina. Fact Sheet.

https://www.undp.org/eurasia/publications/regional-roma-survey-2017-country-fact-sheets

70

UNICEF. (2021). Social Impacts of COVID-19 in BiH: Second Household Survey.

https://www.unicef.org/bih/media/6251/file/Social%20Impacts%20of%20COVID-19%20in%20Bosnia%20and%20Herz

egovina.pdf

71

Agency for Statistics of BiH. (2022). Use of Information and Communication Technology in BiH: 2021.

https://bhas.gov.ba/data/Publikacije/Bilteni/2022/IKT_00_2021_TB_1_HR.pdf

72

USAID/BiH. (2022). 2021 National Survey of Citizens’ Perceptions in BiH.

73

The World Bank. (2018). The Global Financial Inclusion Data/Global Findex - Bosnia and Herzegovina.

http://datatopics.worldbank.org/financialinclusion/country/bosnia-and-herzegovina

74

USAID/BiH. (2019). Gender Analysis for BiH: 2019 Follow-Up.

https://measurebih.com/uimages/Gender20Analysis20201920Follow-Up20Final20Report.pdf

Source: World Bank Data.

*Data for Kosovo from 2018.

Exhibit 7. Percentage of males and

females that use the internet in Western

Balkan countries, 2020

USAID.GOV DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM COUNTRY ASSESSMENT (DECA) | 21

includes digital, rural, and gender factors. Coupled with the age factor, it puts women from rural areas in

an extremely vulnerable position.

75

Data on BiH reveal that older generations use digital technology less often. For example, 98.1 percent of

youth own a smartphone, compared to 79.6 percent of adults.

76

Youth in BiH are also more

comfortable using digital technologies than adults. The largest difference is related to laptop use, where

96.1 percent of youth and 82.6 percent of adults feel somewhat or very confident in using a laptop.

77

According to the Agency for Statistics of BiH, all students enrolled in higher level education use the

internet, compared to approximately 58 percent of retired citizens.

78

When only citizens using the

internet are observed, 100 percent of those ages 16 to 24 use the internet every or almost every day

compared to 97 percent of internet users ages 25 to 54 and 88 percent of internet users ages 55 to 74

who use the internet on (almost) a daily basis.

79