Policy Statement

PS23/6

Financial promotion rules

forcryptoassets

June 2023

Moving around this document

Use your browser’s bookmarks

and tools to navigate.

To search on a PC use Ctrl+F or

Command+F on MACs.

This relates to

Consultation Paper 22/2

which is available on our website at

www.fca.org.uk/publications

Sign up for our news

and publications alerts

See all our latest press

releases, consultations

and speeches.

Request an alternative format

Please complete this form if you require this

content in an alternative format.

Contents

1. Summary 3

2. Our categorisation of cryptoassets 12

3. The consumer journey for investing

incryptoassets 18

4. The role of authorised firms

communicating and approving

cryptoasset financialpromotions 40

5. Our approach to MLR registered

cryptoassetbusinesses communicating

financial promotions 46

6. Cost benefit analysis (CBA) 52

Annex 1

List of non-confidential respondents 66

Annex 2

Abbreviations used in this paper 68

Appendix 1

Near final rules – Legal instrument

3

Chapter 1

Summary

1.1 In January 2022, the Government published a consultation response setting out its

intention to legislate to bring certain promotions of ‘qualifying cryptoassets’ (referred

to as cryptoassets in the rest of this document for simplicity) within the FCA’s remit.

The proposed legislative approach was updated in a policy statement published on

1February 2023. The financial promotions regime will apply to all firms marketing

cryptoassets to UK consumers r,egardless of whether the firm is based overseas or what

technology is used to make the promotion.

1.2 In January 2022, we consulted on financial promotion rules for high-risk investments

including cryptoassets (CP22/2). In August 2022, we published our final rules for other

high-risk investments excluding cryptoassets (PS22/10). We noted that we would

make our rules for cryptoassets once the relevant legislation had been made and that

we intended to take a consistent approach to cryptoassets to that taken for other

high-riskinvestments.

1.3 Now that the relevant legislation has been made, we are publishing this Policy Statement

(PS). The PS summarises the feedback we received to CP22/2 on cryptoassets and

sets out our final policy position and near final Handbook rules. Having considered

the feedback we intend to proceed with categorising cryptoassets as ‘Restricted

Mass Market Investments’ and applying the associated restrictions on how they can

be marketed to UK consumers. We are making targeted changes to our consultation

proposals to align with the rules set out in PS22/10 for other high-risk investments. We

believe these changes are also appropriate for cryptoasset financial promotions. We

are also publishing a Guidance Consultation (GC) (Refer to GC23/1) on non-Handbook

guidance, so firms clearly understand our expectations around the requirement that

financial promotions are fair, clear and not misleading.

1.4 Since we published CP22/2, this work has become even more important. Events in

the cryptoasset sector have continued to highlight the riskiness of these assets.

Cryptoasset prices have fallen sharply, down ~75% between November 2021 and June

2022 (see data from CoinMarketCap). There have been several firm failures resulting in

significant losses for consumers. Many of these cases involved misleading promotions

such as offering high rates of return with no evidence of how these could be achieved

and promoting high-risk, complex products as ‘stable’ such as the algorithmic stablecoin

project Terra/Luna.

1.5 Even when the financial promotions regime comes into force, cryptoassets will remain

high risk and largely unregulated. Consumers should only invest in cryptoassets if they

understand the risks involved and are prepared to lose all their money. Consumers

should not expect protection from the Financial Service Compensation Scheme (FSCS)

or Financial Ombudsman Service (the ombudsman service) if something goes wrong.

4

1.6 The near final rules are in Appendix 1. We have published the rules as near final

immediately after the relevant legislation has been made to give firms as much time as

possible to prepare for this regime. The FCA Board has approved the rules as near final

and we expect to confirm final rules shortly. Subject to exceptional circumstances, no

further changes are expected to what has been published. We expect the rules will have

effect from 8October 2023.

1.7 We will take robust action against firms breaching these requirements. This may include,

but it is not limited to, requesting take downs of websites that are in breach, placing

firms on our warning list, placing restrictions on firms to prevent harmful promotions

and enforcement action. Firms illegally communicating financial promotions to UK

consumers will be committing a criminal offence punishable by an unlimited fine and/or

2years in jail.

Who this affects

1.8 This PS and near final rules will be directly relevant to:

• consumers investing, or who are considering investing, in cryptoassets

• cryptoasset businesses registered with the FCA

• cryptoasset businesses considering, or in the process of, registering with the FCA

• overseas cryptoasset firms marketing, or considering marketing, to UK consumers

• authorised firms considering communicating or approving cryptoasset financial

promotions

• trade bodies for the cryptoasset sector

• other persons involved in communicating cryptoasset financial promotions to

UKconsumers

1.9 The PS and near final rules will also be of interest to:

• any authorised firm or trade body in the consumer investments sector

The wider context of this policy statement

UK Government approach to regulation of cryptoasset promotions

1.10 A 2018 report by the Cryptoassets Taskforce (CATF) identified several risks

cryptoassets pose to consumers. This included the potential for harm where consumers

buy cryptoasset products without appropriate awareness of the risks involved. The

report also found that cryptoasset advertising is often targeted at retail investors and is

typically not fair or clear, and can be misleading.

1.11 The Government has now legislated to bring promotions of qualifying cryptoassets

within scope of the financial promotion regime. This has been implemented by the

Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Financial Promotion) (Amendment) Order

2023. This follows the Government’s Consultation Response and Policy Statement

5

setting out its approach to regulating cryptoasset financial promotions. The definition

of ‘qualifying cryptoasset’ that is in scope of this regime is set out in paragraph 26F

of Schedule 1 to the Financial Promotion Order (FPO). Very broadly, a ‘qualifying

cryptoasset’ is any cryptographically secured digital representation of value or

contractual rights that is transferable and fungible, but does not include cryptoassets

which meet the definition of electronic money or an existing controlled investment.

For simplicity we refer to ‘qualifying cryptoassets’ as ‘cryptoassets’ for the rest of

thisdocument.

1.12 The Government has amended the following controlled activities related to the buying

and selling of investments to include reference to qualifying cryptoassets. This means

that invitations or inducements to engage in these activities in relation to cryptoassets

will be within scope of the financial promotions regime:

• dealing in securities and contractually based investments

• arranging deals in investments

• managing investments

• advising on investments

• agreeing to carry on specified kinds of activity

1.13 The Government has introduced a bespoke exemption in the FPO for cryptoasset

businesses registered with the FCA under the Money Laundering, Terrorist Financing

and Transfer of Funds (Information on the Payer) Regulations 2017 (‘MLRs’). This

exemption, set out in Article 73ZA of the FPO, will enable cryptoasset businesses which

are registered with the FCA under the MLRs, but which are not otherwise authorised

persons (referred to as ‘registered persons’) to communicate their own cryptoasset

financial promotions to UK consumers.

1.14 This exemption is intended to address concerns that requiring financial promotions to

be made or approved by authorised persons would significantly restrict, or amount to an

effective ban on, cryptoasset financial promotions.

1.15 There will be 4 routes to legally promoting cryptoassets to consumers:

i. The promotion is communicated by an authorised person.

ii. The promotion is made by an unauthorised person but approved by an authorised

person. Legislation is currently making its way through the UK Parliament which, if

made, would introduce a regulatory gateway that authorised firms will need to pass

through to approve financial promotions for unauthorised persons.

iii. The promotion is communicated by (or on behalf of) a cryptoasset business

registered with the FCA under the MLRs in reliance on the exemption in Article

73ZA of the FPO.

iv. The promotion is otherwise communicated in compliance with the conditions of

an exemption in the Financial Promotion Order.

1.16 For these purposes, a firm only authorised under the Electronic Money Regulations, or

the Payment Services Regulations is not considered an ‘authorised person’ so cannot

communicate or approve financial promotions. This is set in legislation and cannot be

modified by FCA rules.

6

1.17 Existing exemptions in the FPO will generally apply to promotions of cryptoassets in line

with their existing scopes. However, the Article 48 (high net worth individual) and Article

50A (self-certified sophisticated investor) exemptions will not apply to promotions of

cryptoassets. This is because these exemptions only apply to promotions relating to

a specific set of controlled investments set out in the legislation, broadly investments

related to unlisted securities. The Government has expressly legislated to disapply the

Article 51 (Associations of high net worth or sophisticated investors) and Article 61 (Sale

of goods and supply of services) exemptions to cryptoassets.

1.18 Promotions that are not made using one of these 4 routes will be in breach of section

21 of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA), which is a criminal offence

punishable by up to 2 years imprisonment, the imposition of a fine, or both.

1.19 The Government had initially indicated that it would introduce a 6-month transition

period to ensure compliance with the regime. The final legislation, however, provides for

a 4-month transition, reflecting recent volatility in the cryptoasset sector and the risks

this presents to consumers. The legislation will enter into force on 8October 2023.

Our consultation

1.20 We issued CP22/2 to consult on rules for how cryptoassets can be promoted to UK

consumers. We want consumers to receive timely, high-quality information that

enables them to make effective investment decisions without being pressured, misled

or inappropriately incentivised to invest in products that do not meet their needs.

This means a rules framework that is robust and remains fit for purpose in a changing

investment environment, where promotions are distributed to a mass audience at

increasing speed via online platforms and through social media.

1.21 Our consumer research has shown that ownership of cryptoassets has grown since

the 2018 CATF report and that adverts play an important role in consumer purchasing

behaviour. One of the main ways consumers build their understanding of the risks of,

and regulatory protections relating to, investments is through the information they get

in financial promotions. For high-risk investments, our requirement that promotions

must be fair, clear and not misleading may not be enough to adequately protect

consumers. A promotion may meet these requirements, but a consumer may still not be

able to properly assess whether the underlying investment meets their needs. In these

cases, we can use our financial promotion rules to give consumers further protections,

as set out in our consultation proposals.

How it links to our objectives

1.22 Our rules will advance our consumer protection, market integrity and competition

objectives:

• Consumer protection: Our rules seek to reduce and prevent harm to consumers

from investing in cryptoassets that do not match their risk appetite. We want

consumers to only invest in cryptoassets where they understand the risks involved

and can absorb potential losses. We do not want consumers to be pressured,

misled or inappropriately incentivised to invest.

7

• Market integrity: Failures and unexpected losses for consumers undermine

confidence in UK financial markets. This may impact the soundness, stability and

resilience of the UK financial system. Facilitating consumer understanding and

good investment decisions increases trust in the overall financial system.

• Effective competition in the interests of consumers: Our rules will create a fairer

and more consumer-focused landscape in which firms can compete and innovate.

Competition can more effectively act in the interests of consumers where

consumers are given clear, accurate information that helps them make effective

investment decisions. Our rules will help achieve a level playing field and prevent

overseas firms, who may be currently subject to fewer regulatory standards, from

undercutting UK firms with misleading advertising.

What we are changing

1.23 In CP22/2 we proposed to classify cryptoassets as ‘Restricted Mass Market

Investments’. This would allow them to be mass marketed to UK consumers subject

to certain restrictions, in addition to the overarching requirement that financial

promotions must be fair, clear and not misleading. The restrictions proposed included:

clear risk warnings, banning incentives to invest, positive frictions, client categorisation

requirements and appropriateness assessments.

1.24 We are proceeding largely as consulted. We are making targeted changes to our

consultation proposals as summarised in Table 1 below.

Outcome we are seeking

1.25 Our near final rules are designed so that firms communicating and approving financial

promotions for cryptoassets do so to a high standard.

1.26 Our consumer research shows there is a growing mismatch between consumers’

investment decisions and their stated risk tolerance, including for cryptoassets. This has

the potential to cause significant harm to consumers, including unexpected financial

loss that cannot easily be absorbed. A significant unexpected loss from an investment

can have knock on effects of further financial difficulty and poorer wellbeing, especially

in the current economic climate. The harm is likely to be more acute among individuals

with characteristics of vulnerability.

1.27 Our rules will help alert consumers to the risks from cryptoassets by differentiating

the journey a consumer takes when looking to invest in these high-risk investments,

compared to the journey undertaken when investing in a mainstream investment.

8

Measuring success

1.28 Our ambition for the financial promotions regime is for consumers to only invest in

cryptoassets where they understand the risks involved and can afford to absorb potential

losses. A key success measure will be reducing the number of consumers investing in

cryptoassets who have a low-risk tolerance or who have characteristics of vulnerability.

This will be monitored through the Financial Lives survey and other consumer research.

This is aligned with the objectives of our Consumer Investment Strategy.

1.29 The implementation of this regime should mean that fewer firms who are not authorised

or registered with the FCA are promoting cryptoassets to UK consumers. One success

measure is to reduce the proportion of UK consumers accessing Cryptoassets through

a firm that is not authorised or registered with us.

1.30 In line with our Business Plan, these rules will also enable consumers to help themselves.

A success measure is helping to achieve our target metrics for this outcome, in particular:

i) increasing the number of interventions on non-compliant financial promotions

by regulated firms; ii) increasing the number of warnings on our website related to

unregulated entities, which often involve breaches of the financial promotions regime.

Summary of feedback and our response

1.31 We received 66 responses to CP22/2 from a diverse range of respondents. This included

authorised firms, MLR registered cryptoasset businesses, trade bodies, consultancies,

law firms and individual consumers. PS22/10 provides a summary of responses (see

paragraphs 1.26–1.27).

1.32 On our proposals for cryptoassets, respondents generally disagreed with our proposal

to categorise cryptoassets as Restricted Mass Market Investments (RMMI). The majority

of respondents agreed that some rules around financial promotion of cryptoassets were

necessary to protect consumers and improve the quality of cryptoassets promotions.

Many argued that the approach should be less restrictive and more bespoke, with

marketing restrictions and positive frictions applying only to some types of cryptoassets. In

particular, they argued that different cryptoassets have different risk profiles and called for

a greater differentiation in our approach. Several respondents thought that cryptoassets

should be treated the same as listed or exchange traded securities. Other respondents,

predominantly from mainstream financial services firms, believed our proposals did not go

far enough and called for further restrictions on the marketing of cryptoassets.

1.33 Having considered the feedback, we intend to proceed as consulted with categorising

cryptoassets as ‘Restricted Mass Market Investments’ and applying the associated

restrictions on how they can be marketed to UK consumers. We believe this strikes

the right balance between consumer protection and promoting potentially beneficial

innovation. We are making targeted changes to our consultation proposals. Table 1

summaries these changes and includes changes made as part of PS22/10 (see Table 1

of PS22/10) for completeness and to help firms understand their obligations. Changes

highlighted in bold are unique to this PS and were not previously covered in PS22/10.

9

Table 1: Summary of key changes from CP22/2 proposals

Topic Change

Risk warnings and

associated risk

summaries

We will shorten the main risk warning. We will also modify the risk

warning and risk summary wording relating to what protections

consumers have when investing in cryptoassets. This will set out

that consumers should not expect to be protected by the FSCS or

the ombudsman service if something goes wrong.

We will allow firms to vary the prescribed risk summary where

they have a good reason. For example, if the wording would

be misleading or irrelevant. Equally firms can include any key

investment risks that are not covered by the template. Firms

must make an adequate record of any divergence from the

template and the rationale behind any change. Firms must ensure

their risk summary is accurate and stays up to date with market

developments and business model changes.

Ban on incentives to

invest

We will not apply the ‘shareholder benefits’ exemption set out in

PS22/10.

We will provide greater clarity on what is covered by this ban.

Direct Offer Financial

Promotion (DOFP)

rules

We will provide greater clarity on how firms can comply with the

DOFP and consumer journey rules.

We will clarify that the DOFP rules relate to promotions which include

a manner of response or include a form by which any response may

be made (ie, a mechanism by which consumers can respond in order

to invest their money). They should not limit the information firms

can otherwise provide about a cryptoasset.

Cooling-off period We will clarify that the 24-hour cooling-off period starts from when

the consumer requests to view the Direct Offer Financial Promotion.

Firms can proceed with other parts of the consumer journey while

the cooling-off period ‘applies’ such as Know Your Customer /Anti-

Money Laundering (KYC/AML) checks, client categorisation and the

appropriateness assessment.

If these other processes take more than 24 hours to complete,

firms will not need to introduce an additional pause in the consumer

journey. However, the consumer will still need to give their active

consent that they wish to proceed with the investment.

Client categorisation We will clarify that where consumers must state their income/net

assets to confirm they are high net worth they can provide these

figures to the nearest £10,000/£100,000 respectively. We will clarify

what level of checks we expect firms to conduct on the information

provided by the consumer in the investor declaration.

We will not apply the self-certified sophisticated investor

category.

Appropriateness

assessment

We will modify our rules so that consumers must wait at least 24

hours before undertaking the appropriateness test again from their

second assessment onward.

We will update the guidance on topics we expect firms to cover as

part of this assessment.

10

Topic Change

Record keeping

requirements

We will only introduce requirements to record the metrics proposed

in CP22/2 that relate to client categorisation and the appropriateness

assessment.

Approach to

implementation

We will align with the reduced implementation period of 4 months

set in legislation.

We will clarify how the regime applies to communications

with existing customers and that we generally expect the new

regime to impact communications which seek to encourage new

investments in cryptoassets.

Date and time stamp

for authorised firms

approving financial

promotions

We will allow an alternative format for the date and time stamp for

approved promotions where it is not possible to include these due

tothe space available in the financial promotion being limited by a

third-party provider.

In these circumstances firms must display the Firm Reference

Number (FRN) of the approver, instead of the full name and date of

approval. This text must link to a web page where the firm’s full name,

and the date of the approval, must be displayed.

Consumer Duty We will clarify that the Consumer Duty applies to authorised firms

communicating or approving cryptoasset financial promotions.

We will clarify which parts of the Duty apply given cryptoassets

are only within the financial promotion perimeter.

We will clarify that the Consumer Duty does not yet apply to

financial promotions made by MLR registered cryptoasset

businesses.

Equality and diversity considerations

1.34 We have considered the equality and diversity issues that may arise from the proposals

in this Policy Statement. In CP22/2 we said that overall, we do not consider that the

proposals will have a negative impact on any groups with protected characteristics

under the Equality Act 2010. Our latest cryptoassets consumer research shows

that cryptoassets owners are more likely to be male and younger – aged under 45.

Ownership is highest in London and Northern Ireland. Those who own cryptoassets

are more likely to have a higher-than-average household income. Respondents to

CP22/2 did not identify any equality or diversity issues with our proposals. Overall, we

consider that consumers across all groups will benefit from the protection afforded by

our requirement for financial promotions to be fair, clear and not misleading. We will

continue to consider the equality and diversity implications of the proposals during the

implementation period.

1.35 We have included guidance that we expect firms to take account of the latest

international Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) when designing digital

financial promotions and, in particular, how the risk warning will be displayed. We

would also expect firms to consider the intended recipients of the promotions

they communicate or approve. Where firms communicate financial promotions to

11

consumers that are unlikely to have a good understanding of the English language,

risk warnings and the risk summary should be provided in an appropriate language in

addition to English.

Next steps

1.36 All firms marketing cryptoassets to UK consumers, including those based overseas,

must get ready for this regime. Firms should review the statutory instrument giving

effect to this regime alongside this PS. If firms intend to continue marketing to UK

consumers once the regime comes into force they must consider which of the 4 routes

they will use to lawfully communicate their promotions and how they will meet the

relevant requirements of that route. We encourage firms to take all necessary advice as

part of their preparations.

1.37 We will take robust action against firms breaching these requirements. This may include,

but it is not limited to, requesting take downs of websites that are in breach, placing

restrictions on firms to prevent harmful promotions and enforcement action.

1.38 Firms intending to apply for registration with the FCA under the MLRs should consider

the information on our website about the anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist

financing (AML/CTF) regime and information for firms seeking registration under the

MLRs. Firms should also review information regarding good and poor quality applications

before submitting an application. More information on our approach to MLR registered

cryptoasset businesses communicating financial promotions is set out in Chapter 5.

1.39 We expect authorised firms considering approving cryptoasset financial promotions to

notify us of their intention to do so in line with Principle 11 (relations with regulators) and

SUP 15.

1.40 We encourage responses to our Guidance Consultation by 10August 2023. We will

consider all feedback and, depending on the responses, intend to publish our Final

Guidance in Autumn 2023.

12

Chapter 2

Our categorisation of cryptoassets

2.1 This chapter summarises the feedback on our proposed categorisation of cryptoassets

as ‘Restricted Mass Market Investments’ (question 25 of CP22/2).

CP proposals

2.2 CP22/2 sought to rationalise our rules for high-risk investments and set out 3 clear

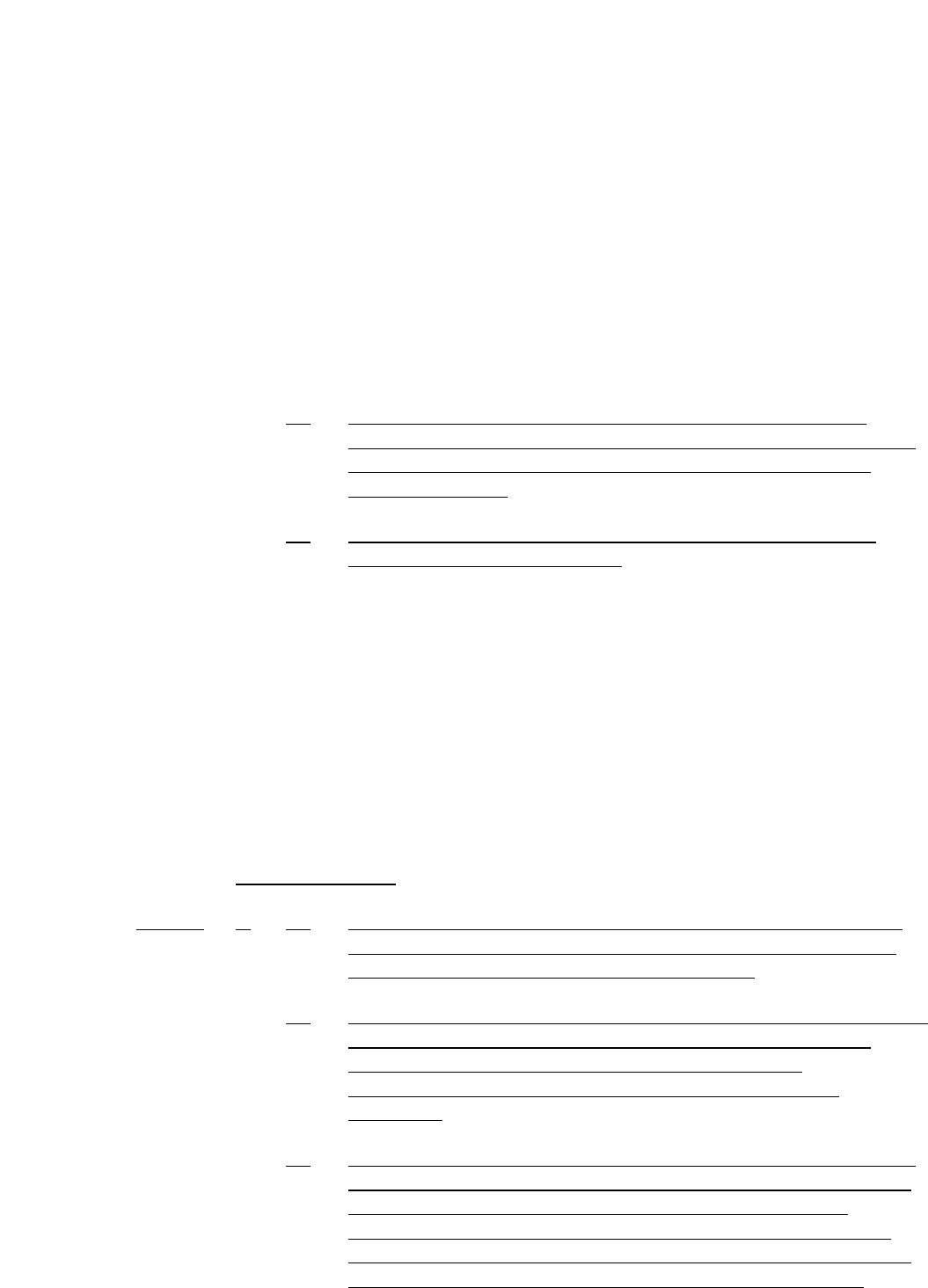

categories of marketing restrictions that apply to promotions of investments. Figure 1

summarises these categories.

Figure 1: Financial promotion marketing restrictions product categories

Readily Realisable

Securities (RRS)

Listed or exchange traded

securities. For example

shares or bonds traded on

the London Stock

Exchange.

No marketing restrictions

Restricted Mass

Market Investments

(RMMI)

Non-Readily Realisable

Securities (NRRS). For

example shares or bonds in

a company not listed on an

exchange.

Peer-to-Peer (P2P)

agreements

Qualifying cryptoassets

Mass marketing allowed to

retail investors subject to

certain restrictions

Non-Mass Market

Investments (NMMI)

Non-Mainstream Pooled

Investments (NMPI). For

example pooled

investments in an

unauthorised fund.

Speculative Illiquid

Securities (SIS). For example

speculative mini-bonds.

Mass marketing banned to

retail investors

More restrictions

2.3 We proposed to categorise cryptoassets as ‘Restricted Mass Market Investments’

and subject them to similar regulatory requirements as those that apply to other

investments within this category. This would allow cryptoassets to be mass marketed to

consumers, subject to certain restrictions. This categorisation reflects our judgement

of the risks cryptoassets pose to consumers. In particular, risks from sudden, large and

unexpected losses due to volatility, firm failure, comingling of funds, cyber-attacks and

financial crime. Poor quality and misleading promotions, combined with pressure selling

tactics, can exacerbate these risks and lead to consumers buying cryptoassets that are

not aligned to their risk tolerance and do not meet their needs.

13

2.4 Given the high-risk nature of cryptoassets, we do not believe it is appropriate to

categorise them as ‘Readily Realisable Securities’ and allow them to be mass marketed

to consumers without restriction. Equally we do not believe it would be proportionate to

classify cryptoassets as ‘Non-Mass Market Investments’ at this stage and subject them

to a ban on marketing to ordinary retail investors. The industry is still developing, and

we are looking to encourage, not stifle, innovation that may be beneficial to consumers

where there is appropriate consumer protection. This is aligned with the response from

the Treasury to their consultation on cryptoasset promotions.

Feedback received

2.5 We received 46 responses to this question. Respondents had a net negative view

on the proposed categorisation of cryptoassets (37% agreed 17% were neutral and

45%disagreed).

2.6 Where respondents agreed with our proposal their main argument was that our proposed

categorisation struck the right balance between promotion of innovation and protection

of consumers that choose to invest in a relatively nascent and developing asset class.

These respondents highlighted the risks of cryptoassets but believed that, if promoted in a

compliant manner, some cryptoassets may not be as opaque as other complex investments

subject to tighter marketing restrictions eg binary options or mini-bonds.

2.7 Respondents also argued that applying our financial promotion rules to cryptoassets

would help achieve fair and consistent marketing to consumers.

2.8 Where respondents disagreed with our proposals the most common argument

was that there should be greater differentiation in our treatment of cryptoassets

(11respondents). These respondents believed different cryptoassets had different

risk profiles and so should be subject to different levels of marketing restrictions. They

highlighted asset-backed cryptoassets (eg cryptoassets backed by gold), fan tokens and

stablecoins as examples of cryptoassets that they believe have lower risk profiles and so

should be subject to less stringent marketing restrictions.

2.9 Respondents from the cryptoasset sector argued that cryptoassets shared similar

characteristics with listed or exchange traded securities so should be categorised

as Readily Realisable Securities and not be subject to marketing restrictions

(7respondents). They argued that cryptoassets had higher levels of liquidity, high

degrees of market capitalisation and the availability of 24/7 continuous trading which

made them materially different to other investments categorised as RMMI.

2.10 Other respondents, predominantly from the mainstream finance sector, argued

our proposals did not go far enough and that cryptoassets should be classified as

Non-Mass Market Investments (NMMI) and subject to the highest level of marketing

restriction (5respondents). They argued that cryptoassets had greater risks than

other investments categorised as RMMI. For example, risks related to volatility

and technological risks associated with cryptoassets. They highlighted the largely

unregulated nature of the sector, even once subject to the financial promotions regime,

as reasons for applying more stringent marketing restrictions.

14

2.11 A few respondents noted that the proposals are likely to increase the cost of customer

acquisition. They believed our rules should only apply above a minimum level of

investment. Without this, they believed our rules would drive an increase in the minimum

investment amounts firms impose, resulting in financial exclusion.

2.12 A few respondents believed the proposals would limit the promotion of cryptoassets to

high net worth and sophisticated investors.

Our response

Having carefully considered the feedback, we intend to proceed as we

consulted and categorise cryptoassets as RMMI. We continue to believe

this approach strikes the right balance between consumer protection and

promoting responsible innovation andcompetition.

Events since we consulted have not altered our views of the riskiness of

cryptoassets. Indeed, cryptoassets have continued to demonstrate the

significant risks that we highlighted in CP22/2. This includes:

• Sudden, large and unexpected losses: Cryptoasset prices have fallen

sharply, down from a total market capitalisation of roughly $3trillion in

November 2021 to $800bn in June 2022. Individual cryptoassets have

seen spectacular collapses, such as Terra/Luna and FTT.

• Firm failure: 2022 saw several high-profile failures of firms operating

in the cryptoasset market. This included, among others, the collapse

of algorithmic ‘Stablecoin’ project Terra/Luna; borrow/lending

platforms such as Celsius, Voyager and Three Arrows Capital and the

exchangeFTX.

• Comingling of funds: These firm failures have highlighted severe

deficiencies in governance, risk management and operational resilience

frameworks of cryptoassets firms, including the co-mingling of client

and own funds. For example, FTX is alleged to have diverted customers’

assets to a related crypto hedge fund (Alameda Research LLC) and

then used those co-mingled customers’ funds at Alameda to make

undisclosed venture investments, lavish real estate purchases, and large

political donations.

• Financial crime: Cryptoasset markets continue to be characterised

by high degrees of fraud, money laundering and financial crime. For

example, research from Solidus Labs suggest that up to 8% of tokens on

the Ethereum blockchain and 12% of tokens on the BNB chains are ‘hard

rug pull’ scam tokens whereby a scam is programmed directly into the

token. For example, the way in which a token is programmed may mean

it is only possible to buy, but not sell, the token. Between September

2020 and December 2020, 200,000 scam tokens are estimated to have

been created on these networks. Similarly, research from Chainalysis

suggests that 24% of actively traded tokens on the Ethereum and BNB

blockchains display characteristics of ‘pump and dump’ fraud, losing

more than 90% of their value in the first week of trading after launch.

15

• Cyber-attacks: 2022 was the biggest year ever for crypto cyber-

attacks and hacking, with data from Chainalysis estimating that $3.8bn

was stolen from cryptoasset businesses.

Given these significant risks it would not be appropriate to categorise

cryptoassets as ‘Readily Realisable Securities’ and allow them to be

mass marketed to consumers without restriction. Our categorisation of

cryptoassets is based on a holistic judgement of the risks they pose to

consumers and is not solely based on liquidity risk.

We agree that not all investments subject to the RMMI rules have the

same risk profile. For example, some have greater levels of liquidity risk

while others have greater levels of complexity or information asymmetry.

The common feature of investments subject to our RMMI rules is that

they are only likely to be appropriate for consumers as a small part of

a diversified portfolio and they have characteristics which represent a

higher risk to retail investors. This means they should only be accessed

when consumers understand the risks involved. Inevitably this will apply

to a broad range of investments. However, we believe the specific

restrictions placed on the promotion of these investments, in particular

that ordinary retail investors confirm that they will limit their exposure to

such investments to no more than 10% of their net assets and that the

investment must be considered appropriate for them, remain relevant for

the risk posed by a wide range ofcryptoassets.

With respect to the specific types of cryptoassets which respondents

argued presented a lower risk profile and so should be subject to fewer

marketing restrictions:

• Stablecoins: Market events, including the collapse of so-called

algorithmic ‘stablecoins’ have highlighted the significant risks inherent

in these types of cryptoassets. Even where a cryptoasset claims to

maintain its stability by being backed by traditional assets there is often

little transparency around these backing assets and how stability is

maintained. This is important because the financial promotions regime

will only enable us to set rules for how these cryptoassets can be

marketed to consumers. It does not allow us to make rules to address

other risks to consumers and market integrity such as rules related to

backing assets, redemptions rights, prudential, operational resilience

or governance requirements. The Government has confirmed its

intention to legislate to bring fiat backed stablecoins with the propensity

to be used for payments into the regulatory perimeter. As part of the

development of this regime we will consider what the appropriate

financial promotion rules are for cryptoassets that are subject to

additional regulatory requirements.

• Asset backed tokens eg commodity tokens: The structure of

these assets and the ability to buy and sell them on cryptoasset

trading venues, among other features, means that they also share

characteristics with, and pose similar operational, market integrity and

consumer risks as, ‘unbacked’ crypto tokens. For example, susceptibility

to cyber-attacks and risk of consumer losses and fraud. For this reason,

16

the Treasury did not consider that a bespoke regulatory regime was

necessary for this type of cryptoasset in its recent consultation on a

future financial services regulatory regime for cryptoassets. We agree

with thisassessment.

• ‘Fan tokens’: In practice, most fan tokens are a hybrid utility-investment

type token and as a result, there are still significant risks attached to their

purchase. The ecosystem within which fan tokens are bought, sold and

used is unregulated. It is unclear how prices are determined. Consumers

are also often required to first purchase a different cryptoasset and

use this to purchase fan tokens. There is a secondary market for both

these cryptoassets and the fan tokens themselves, and many of these

markets can be illiquid and the prices volatile. Given the characteristics

we do not believe it would be appropriate to carve-out fan tokens as

described from the RMMI classification.

We understand concerns raised by respondents that cryptoassets

may pose higher risks than other investments characterised as RMMI.

However, we believe that it would not be appropriate to categorise all

cryptoassets as NMMI and subject them to a mass marketing ban at this

time. We recognise the potential positive impact that Distributed Ledger

Technology (DLT) and certain cryptoassets might have in the future on

financial services. In particular, we see potential benefits for regulated

firms in using DLT and similar technologies in relation to products and

services associated with their regulated activities. It may lower their

costs, increase efficiency, enable faster payments and settlements and

help better monitor transactions. We are looking to encourage, not stifle,

responsible innovation that may be beneficial for consumers, where there

is appropriate consumer protection.

We recognise that our proposals will increase costs to firms marketing

cryptoassets and may lead to an increase in minimum investment

amounts. However, that is an inevitable consequence of what we are trying

to achieve, namely ensuring consumers only invest in cryptoassets where

they understand the risks involved and can absorb potential losses. We

do not apply minimum investment thresholds in our financial promotion

rules for other investments and we do not see a compelling reason to treat

cryptoassets differently.

We published a robust CBA on our proposals in CP22/2 (see Annex 2 of

CP22/2). We have revised the CBA in light of feedback which can be found

in Chapter 6 of this PS.

We wish to clarify that our rules do not limit promotions of cryptoassets

to only high net worth or sophisticated investors. Firms can communicate

financial promotions for cryptoassets to all consumers, subject to

complying with the relevant requirements. Firms can only make DOFPs

to consumers who have been categorised as Restricted, High net

worth or certified sophisticated investors, in addition to complying

with other requirements. We expect that most consumers investing in

cryptoassets will be categorised as a Restricted Investor. More details on

17

our proposed rules on client categorisation can be found in Chapter 3,

paragraphs3.36- 3.46.

In addition to this PS we have issued a Guidance Consultation which

aims to clarify our expectations of financial promotions for cryptoassets,

particularly for cryptoasset models and arrangements that can pose

significant harm to consumers. As part of this Guidance Consultation,

we are also seeking views on the risks and benefits of certain types of

cryptoasset models, and whether further restrictions are needed on their

marketing to adequately protect consumers. We welcome views from

respondents on these proposals by 10August 2023.

18

Chapter 3

The consumer journey for investing

incryptoassets

3.1 This chapter summarises the feedback on our proposed rules for the consumer journey

when investing in cryptoassets (Chapter 3 of CP22/2, questions 2-8), our proposed

approach to exemptions for cryptoassets (question 26 of CP22/2) and our approach

to implementation (question 11 of CP22/2). The rules in this chapter are only relevant

where a firm communicates or approves a financial promotion to a retail client.

Risk warnings and risk summaries

CP22/2 proposals and PS22/10amendments

3.2 In CP22/2 we proposed a standard risk warning to be included on all financial promotions

for Restricted Mass Market Investments and Non-Mass Market Investments, and a set

of prescribed format requirements for how this should be displayed. We also proposed

that a standard summary of risk information for the particular investment type (a

‘risk summary’) would need to be linked to from the ‘Take 2 min to learn more’ text, or

be provided to the consumer in a durable medium where possible outside of digital

settings. The risk warning we consulted on was as follows:

Don’t invest unless you’re prepared to lose all your money invested. This is a

high-risk investment. You could lose all the money you invest and are unlikely

to be protected if something goes wrong. Take 2 min to learn more.

3.3 The risk warning wording, risk warning prominence and the format of linking to a risk

summary were all tested and found to be effective at improving consumers’ perception

and understanding of key investment risks in a behavioural science setting.

3.4 In PS22/10 we made several amendments to these proposals. First, we adjusted the

risk warning wording slightly to ensure it reads as smoothly as possible while retaining

the core behavioural features that were found to be effective in our testing. As in our

consultation proposals, we allowed firms to use a shorter version of the risk warnings

when there are character limits on the financial promotion imposed by a third-party

marketing provider. The new standard risk warning is:

Don’t invest unless you’re prepared to lose all the money you invest. This is a

high-risk investment and you are unlikely to be protected if something goes

wrong. Take 2 mins to learn more.

19

3.5 Second, we introduced different risk warnings for different products. For example,

requiring the ‘unlikely to be protected’ wording to be removed where the activity of

issuing or providing the investment involves an authorised person (or an appointed

representative) and could give rise to an FSCS claim.

3.6 Third, we amended our rules to allow firms to tailor the risk summary to their investment

offering. Firms can diverge from the prescribed risk summary if they have a valid reason

for doing so. For example, if a certain bit of text would be irrelevant or misleading, or

if there is another risk that firms think should be included. Firms must record their

rationale for each change, and we will draw on this if we have concerns with a firm’s

changes to a risk summary. The firm’s amended risk summary must still summarise

the key risks of the investment in a consumer-friendly way and take around 2 minutes

toread.

3.7 This change was introduced to allow firms to ensure their risk summary is relevant to

their offering, and remains relevant as their business changes over time. Firms must

be able to explain to us what changes they’re making to their risk summary and why

ifchallenged.

3.8 Fourth, we introduced additional prominence requirements for how the risk warning and

risk summaries must be displayed to provide greater clarity on how our rules apply for

promotions made in different mediums. For example, where a promotion is made in a

digital medium firms should not require the consumer to take any further action to see

the full risk summary after they have clicked the hyperlink from the risk warning. Where

the promotion is made in a durable medium (ie in a non-digital setting) the risk summary

should be prominently displayed alongside other information in the promotion. The

text should be legible, and not hidden within other forms of disclosure. This is intended

to ensure that risk warnings and risk summaries are given sufficient prominence,

regardless of the medium used to make the promotion. Table 2 summarises these

prominencerequirements.

Table 2: Provisions for the risk warning and associated risk summary, for digital and

non-digital mediums of communication

Digital medium

(eg website, mobile application)

Non-digital medium

(eg TV/radio, phone call,

postal communication)

Provisions for the risk warning text

Shorter risk

warning

Can be used if the full risk warning

would exceed the character

limits permitted by a third-party

marketing provider.

Can be used if the full risk warning

would exceed the character

limits permitted by a third-party

marketing provider.

‘Take 2 mins to

learn more’ text

at the end of the

risk warning

Must be included, unless:

• inclusion would exceed the

character limits permitted by a

third-party marketing provider

• the digital medium doesn’t allow

text to be linked

Does not need to be included.

20

Digital medium

(eg website, mobile application)

Non-digital medium

(eg TV/radio, phone call,

postal communication)

Provisions for the presentation of the risk warning

How it must

beprovided

Must always feature within the

financial promotion in line with the

relevant prominence requirements,

no matter what medium is used.

Must always feature within the

financial promotion in line with the

relevant prominence requirements,

no matter what medium is used.

Prominence

requirements

Risk warning prominence

requirements apply for all mediums.

It must be:

• prominent

• legible and contained in its own

border, with the right bold/

underlined text

• without a design feature that

reduces visibility/prominence

Additional requirements apply

forwebsites/mobile applications.

Must be:

• visible and statically fixed at the

top of the screen, below anything

else that also stays static, even

when the client scrolls up/down

the page

• on every linked page from the

promotion that relates to the

investment

Risk warning prominence

requirements apply for all mediums.

It must be:

• prominent

• if in writing, legible and contained

in its own border, with the right

bold/underlined text

• without a design feature that

reduces visibility/prominence

For television broadcasts, it must

be prominently fixed on the screen

for the duration of broadcast.

Provisions for the accompanying risk summary

How it must

beprovided

Must be hyperlinked from ‘Take 2

mins to learn more’ in the warning

unless:

• ‘Take 2 mins…’ is excluded as

it would exceed the character

limits permitted by a third-party

marketing provider. In this case,

the risk summary must be linked

to from the risk warning text

instead.

• ‘Take 2 mins…’ is excluded as the

digital medium doesn’t allow text

to be linked. The risk summary

does not need to be provided in

this case.

Must be provided in a durable

medium, unless the medium means

this is not possible (eg television or

radio broadcast), in which case the

risk summary does not need to be

provided.

If it is a real time financial

promotion, the summary should

still be provided in a durable

medium on or around the

time of the promotion being

communicated.

21

Digital medium

(eg website, mobile application)

Non-digital medium

(eg TV/radio, phone call,

postal communication)

Prominence

requirements

Pop-up (or equivalent) prominence

requirements apply. It must be:

• prominently brought to the

consumers attention

• legible and contained in its own

border, with the right bold/

underlined text

• statically fixed in the middle of the

screen

• the focus of the screen

• without a design feature that

reduces visibility/prominence

Risk warning prominence

requirements apply to the

summary. It must be:

• prominent

• legible and contained in its own

border, with the right bold/

underlined text

• without a design feature that

reduces visibility/prominence

Feedback received

3.9 PS22/10 summarises the feedback to the risk warning proposals in CP22/2. This includes

feedback from respondents representing the cryptoasset sector (see paragraphs 3.4–3.13).

3.10 In terms of cryptoasset specific responses, several respondents recognised the

importance of stronger risk warnings but argued against the prescribed format. Instead,

they argued the FCA should leave some flexibility for firms to tailor and adapt the text

of the risk warnings and risk summary to reflect specific characteristics of services and

cryptoassets they offer.

3.11 Several respondents highlighted that the wording of the risk warning should be kept

under regular review, and potentially subject to further consumer testing to ensure they

remain relevant and do not become so-called ‘white noise’, which consumers ignore

once they become used to it.

3.12 A few respondents argued that we should remove the word ‘invest’ from the risk warning

to avoid giving what they considered to be a false legitimacy to cryptoassets and making

them seem equivalent to mainstream investments.

3.13 One respondent asked that we strengthen the risk warning wording related to what

protection is available to consumers. This respondent highlighted that as cryptoassets

are only being brought within the financial promotions regime, but not the regulated

activity regime, there are very few, if any, circumstances in which a consumer could

make a protected claim to the FSCS in relation to cryptoassets.

Our response

PS22/10 sets out our response to the feedback on the CP22/2

risk warning proposals. This includes feedback from respondents

representing the cryptoasset sector.

22

We intend to apply the amendments made in PS22/10 to our risk warning

and risk summary for cryptoassets. In particular the amendments

related to allowing firms to tailor the risk summary to the specifics

of the investment and additional prominence requirements for

differentmediums.

We recognise the diverse range of cryptoassets that will be within scope of

our rules. We appreciate that there may be instances where some of the

risk summary wording in our template may not be relevant to, or right for, a

particular cryptoasset. Equally our template risk summary may not capture

the key risks relevant to a particular type of cryptoasset. Given the diverse

range of cryptoassets, we expect firms will need to frequently amend the

risk summary to the specifics of the cryptoasset they are promoting. We will

monitor and challenge firms where we believe their risk summary does not

accurately reflect the key risks relevant to the particular cryptoasset they are

promoting. Firms must keep a record of any changes to risk summaries that

they make and ensure they have a valid reason for each change. We expect

any amended risk summaries to still be in the spirit of the template in our

handbook, in particular using FAQ style consumer friendly language and not

taking more than 2 minutes to read.

We have further considered the risk warning wording for cryptoassets.

Even when cryptoassets come within the financial promotions regime

they will still be largely unregulated. The type of cryptoassets that are

being brought within the financial promotions regime are not within the

scope of the regulated activities regime. Given this, consumers should

not expect to be able to make a claim to the FSCS if the cryptoasset

they are invested in, or the firm providing services to them in relation

to cryptoassets, fails. Similarly, consumers investing through an

unauthorised firm, including firms who are only MLR registered with the

FCA, will not be able to make an eligible complaint to the ombudsman

service. So we will amend our risk warning for cryptoassets to help

consumers better understand this lack of protection. We will also amend

our risk summary template. The new risk warning for cryptoassets will be:

Don’t invest unless you’re prepared to lose all the money you invest.

This is a high-risk investment and you should not expect to be

protected if something goes wrong. Take 2 mins to learn more.

We will keep this wording under review and consider if changes are

needed as the wider regulatory regime for cryptoassets is developed.

We will monitor the effectiveness of the risk warning over time using our

Financial Lives Survey and conduct further behavioural testing when

appropriate. We also encourage firms to monitor this themselves.

We understand the concerns around the use of the word ‘invest’ in relation

to cryptoassets. However, both the Treasury, the FCA and international

regulators have routinely referred to cryptoassets as ‘investments’ in

past publications. Our consumer research shows that consumers treat

23

cryptoassets as an investment so we believe it is appropriate to describe

them as such. The consumer journey rules set out in this chapter will help

differentiate cryptoassets from mainstreaminvestments.

We would like to remind firms that the risk summary should relate to the

investment type or types featured in the financial promotion. There is no

requirement for the risk summary to be the same for a particular firm the

whole way through the journey.

Banning incentives to invest

CP22/2 proposals and PS22/10amendments

3.14 In CP22/2 we proposed to ban financial promotions for high-risk investments from

offering any monetary or non-monetary benefits that incentivise investment

activity, such as ‘refer a friend’ or new joiner bonuses. This is modelled on a similar

ban that applies to the marketing and distribution of Contracts for Difference

(seeCOBS22.5.20).

3.15 In PS22/10 we amended this proposal to exclude ‘shareholder benefits’ from the ban,

namely products and services produced or provided by the issuer of, or borrower under,

the relevant investment. For example, to allow a brewing company raising funds on a

crowdfunding platform to provide discounts to investors on the beer it produces.

Feedback received

3.16 PS22/10 summarises the feedback to the proposed ban on incentives to invest in

CP22/2. This includes feedback from respondents representing the cryptoasset sector

(see paragraphs 3.15 – 3.23).

3.17 In terms of cryptoasset specific responses, respondents from the cryptoassets sector

disagreed with the proposals to ban incentives to invest. These respondents argued

that ‘refer a friend’ is a valid marketing tool used by many legitimate firms to grow

their clientele and expand their business. They argued that a complete prohibition

of inducement to invest will create barriers for firms while having a limited impact on

reducing consumer harm.

3.18 On the other hand, respondents from consumer organisations, strongly supported

the proposal to ban incentives to invest as they may encourage investments that

are not aligned to the investor’s risk tolerance. There is a risk that a recommendation

from a friend is received with inappropriate confidence about the suitability of an

investment. These respondents argued that incentives such as ‘early bird offers’ create

time pressure to invest and increase the risk that investors do not review relevant

information, risk warnings and so make inappropriate decisions to invest.

One respondent, asked for further clarification as to what constitutes an incentive

toinvest.

24

Our response

PS22/10 sets out our response to the feedback on the CP22/2 proposals

to ban incentives to invest. This includes feedback from respondents

representing the cryptoasset sector.

We intend to proceed with applying the ban on incentives to

cryptoasset promotions. We do not intend to apply the ‘shareholder

benefit’ exemption to cryptoasset promotions. Due to the inherently

programmable nature of cryptoassets compared with securities, applying

this exemption would create an unacceptably high risk of firms arbitraging

this rule and using the exemption to promote benefits that distort

consumers investment decisions.

We continue to believe that incentives to invest can unduly influence

consumers’ investment decisions and cause them to invest without fully

considering the risks involved. Given the evidence from our consumer

research which shows how social and emotional factors can have a

powerful impact on investment decisions we will be proceeding with

applying this ban to cryptoasset financial promotions.

We wish to clarify that we would not consider benefits that are intrinsic

to the cryptoasset or exclusively bound up with its function and/or

business model to be considered an ‘incentive’. This might include

features or benefits that are part of the terms and conditions associated

with a particular cryptoasset. For example, cryptoassets that serve to

provide the owner with voting rights, and which are used for the purpose

of establishing governance arrangements for a particular platform or

project would not be considered an incentive.

However, a benefit that is not intrinsic to the cryptoasset, or exclusively

bound up with its function or business model, and which is used to

motivate a consumer to buy that cryptoasset is likely to be considered an

incentive. For example, offering additional ‘free’ cryptoassets is likely to be

considered an incentive. Furthermore, a feature or benefit is likely to be

considered an incentive where it is only available for a limited time period.

On 2June 2023, we published a consultation on additional guidance

and targeted amendments to the scope of this ban for all promotions of

RMMIs and NMMIs. These proposals will also be relevant to promotions

for cryptoassets. We welcome responses from firms operating in the

cryptoasset sector to these proposals by 10 July 2023.

25

Cooling-off period

CP22/2 proposals and PS22/10 clarifications

3.19 In CP22/2 we proposed a minimum 24-hour cooling-off period for first-time investors

with a firm. This would mean that the consumer could not receive a Direct Offer

Financial Promotion (DOFP) unless they reconfirmed their request to proceed after

waiting at least 24 hours.

3.20 In PS22/10 we provided greater clarity as to how we expect this rule to work in practice

and on how our DOFP rules work more generally.

3.21 As set out in our Handbook Glossary a DOFP is defined as:

a financial promotion that contains:

a. an offer by the firm or another person to enter into a controlled agreement with any

person who responds to the communication; or

b. an invitation to any person who responds to the communication to make an offer to

the firm or another person to enter into a controlled agreement

and which specifies the manner of response or includes a form by which any

response may be made.

3.22 So a DOFP arises where the financial promotion specifies the manner of response or

includes a form by which any response may be made. This is intended to ensure that

extra protections kick in before consumers are in a position (as a result of the DOFP)

to take the crucial step towards placing their money in the investment. A manner of

response can take many forms. Examples might include a promotion containing a ‘buy

now’ button which enables the consumer to invest or a form asking the consumer to

provide their bank account details. An assessment of whether a particular financial

promotion constitutes a DOFP will depend on the specific circumstances. However,

anything that promotes an investment and contains a mechanism which enables

consumers to place their money in that investment is likely to constitute a DOFP.

3.23 Firms must apply the additional consumer journey protections outlined in this PS before

they can make a DOFP. We expect most firms will implement these proposals as part of

a consumer ‘on-boarding’ journey alongside any other checks the firms may complete

such as AML/KYC checks. Once the consumer has been on-boarded, and the relevant

conditions for communicating DOFPs have been satisfied, the firm can show the

consumer the DOFP. Figure 2 provides a stylised example of how our DOFP rules could

be applied.

26

Figure 2: Stylised example of how rms could apply the DOFP rules

Firm shows the consumer the financial promotion which:

i) Contains the appropriate risk warning;

ii) Does not contain incentives to invest

Firm begins ‘on-boarding’ the consumer and

conducts relevant checks eg KYC/AML checks

Firm obtains the consumers name

Consumer requests to view the Direct Offer Financial Promotion

eg requests to be able to invest

Firm shows the consumer the personalised

risk warning

Consumer categorises themselves as:

• Restricted investor

• High net worth investor

• Self-certified sophisticated investor*

• Certified sophisticated investor

Firm assesses the investment as appropriate

for the consumer

Firm shows the Direct Offer Financial Promotion and the

consumer is able to place their money in the investment

At least 24

hours must

elapse

* the self-certified sophisticated investor category is not applicable to cryptoassets.

3.24 The DOFP rules are not intended to limit the information firms can otherwise provide

to consumers about the investment. For example, a financial promotion can contain

information about the investment opportunity such as potential rates of return and the

business model of the cryptoasset being promoted. This information alone, without a

‘manner of response’ or ‘form by which any response may be made’ would not trigger

the additional protections. This is aligned with guidance we have previously provided in

PS19/14 to P2P firms on how to apply the DOFP rules. In particular that to avoid being a

DOFP the communication should not contain details of how to apply or to make an offer,

or an application form (see paragraph 2.28 of PS19/14).

3.25 For RMMIs the 24-hour cooling-off period starts from when the consumer requests

to view the DOFP. Firms must not show the DOFP until at least 24 hours have elapsed

since the consumer requested to view the DOFP. However, firms may proceed with

other parts of the client on-boarding process while the cooling-off period is in effect.

For example, performing KYC/AML checks, showing the personalised risk warning, client

27

categorisation and the appropriateness assessment (including any lock-out period

from the investment being assessed as being inappropriate for the investor). If these

processes take more than 24 hours then firms will not need to wait an additional period

before showing the DOFP, though consumers must still give their active consent that

they wish to proceed with the consumer journey.

Feedback received

3.26 PS22/10 summarises the feedback to the proposed cooling-off period in CP22/2.

This includes feedback from respondents representing the cryptoasset sector (see

paragraphs 3.25-3.34).

3.27 In terms of cryptoasset specific responses, respondents from the cryptoasset sector

thought the proposal will make the investment process unnecessarily burdensome and

may drive customers offshore.

3.28 One respondent noted that the 24-hour cooling-off period is not practical in the context

of a web or mobile-based trading platform due to the liquid nature of cryptoasset

investments. They noted that the price of the investment is likely to move during the

cooling-off period, so we should provide further clarity as to when in the consumer journey

it will apply, and whether consumers would be prevented from seeing the cryptoassets

and prices available, or basic functionalities of the platform during the cooling-off period.

Two respondents noted that the cooling-off period should be implemented before the

customer is able to trade and should not be used to reverse the trade.

Our response

PS22/10 sets out our response to the feedback on the CP22/2

cooling-off period proposals. This includes feedback from respondents

representing the cryptoasset sector.

We intend to proceed with applying the cooling-off period to DOFPs of

cryptoassets. We continue to believe this measure is important to help

consumers have sufficient time to consider whether the investment is

appropriate for them. We expect most firms will implement this proposal

as part of their wider consumer onboarding process. This includes

conducting AML/KYC checks on customers. The guidance provided in

PS22/10 and repeated above should provide sufficient clarity for firms on

how to apply this rule and the DOFP rules more broadly.

We wish to clarify that the cooling-off period does not apply to each

individual transaction in a cryptoasset. We recognise that applying this

rule on a transaction-by-transaction basis could itself result in consumer

harm. This rule only applies to first-time investors with a specific firm ie

where a consumer has not previously received a DOFP from the firm.

It also does not otherwise restrict the information firms can provide to

consumers during the cooling-off period, such as information on prices.

28

Personalised risk warning pop-up

CP22/2 proposals and PS22/10amendments

3.29 In CP22/2 we proposed introducing a personalised risk warning pop-up (or equivalent)

for first-time investors with a firm. For ‘Restricted Mass Market Investments’, this would

appear before a Direct Offer Financial Promotion could be communicated.

[Client name], this is a high-risk investment. How would you feel if you lost the

money you’re about to invest? Take 2 min to learn more.

3.30 The ‘Take 2 min to learn more’ would link to the same product specific risk summary as

in the main risk warning. Where the financial promotion does not appear on a website,

mobile application or other digital medium, firms would need to provide the personalised

risk warning to the consumer, accompanied by the risk summary in a durable medium.

3.31 This intervention was informed by the findings of our behavioural research. We did not

test the intervention in this exact format, but the testing did show that personalised

messages and prominent directions to further information were the most effective

intervention in getting consumers to click on the risk summary. So, we believe this

intervention would be effective in getting consumers to read the risk summary and

that the risk summary would be effective in influencing consumers’ understanding of

theinvestment.

3.32 In PS22/10 we made a few amendments to this proposal. First, we aligned with the

changes to our main risk warning and allowed firms to tailor the risk summary linked to in

the personalised risk warning to the specifics of the investment being promoted. Firms

would be required to record their rationale for any changes.

3.33 Second, we introduced additional prominence requirements on how the personalised

risk warning and risk summary must be displayed in different mediums. This is intended

to ensure that personalised risk warnings are given sufficient prominence, regardless

of the medium used make the promotion. Table 3 summarises these prominence

requirements.

29

Table 3: Provisions for the personalised risk warning and the associated risk

summary, for digital and non-digital mediums of communication

Digital medium

(eg website, mobile application)

Non-digital medium

(eg phone call)

Provisions for the personalised risk warning

How it must

be provided

Must be clearly brought to the retail

client’s attention by means of a pop-

up box (or equivalent).

Must be communicated.

Prominence

requirements

Pop-up (or equivalent) prominence

requirements apply. It must be:

• prominently brought to the client’s

attention

• legible and contained in its own

border, with the right bold/

underlined text

• statically fixed in the middle of the

screen

• the focus of the screen

• without a design feature that

reduces visibility/prominence

No specific requirements.

‘Take 2 mins

to learn more’

text at the end

of the warning

Must be included. Does not need to be included.

Next step Personalised risk warning must be

accompanied by an invitation to the

retail client to specify whether they

wish to leave, or continue with, the

investment journey.

Following the communication of

the personalised risk warning and

the provision of the risk summary in

a durable medium, the retail client

must be invited to specify whether

they wish to leave, or continue with,

the investment journey.

Provisions for the accompanying risk summary

How it must

be provided

Must be linked to from ‘Take 2 mins

to learn more’ in the personalised risk

warning.

Must be provided in a durable

medium.

Prominence

requirements

Pop-up (or equivalent) prominence

requirements apply. It must be:

• prominently brought to the client’s

attention

• legible and contained in its own

border, with the right bold/

underlined text

• statically fixed in the middle of the

screen

• the focus of the screen

• without a design feature that

reduces visibility/prominence

Risk warning prominence

requirements apply to the summary.

It must be:

• prominent

• legible and contained in its own

border, with the right bold/

underlined text

• without a design feature that

reduces visibility/prominence

30

Feedback received

3.34 PS22/10 summarises the feedback to the proposed personalised risk warning in CP22/2.

This includes feedback from respondents representing the cryptoasset sector (see

paragraphs 3.38–3.43).

3.35 In terms of cryptoasset specific response, respondents from the cryptoasset sector

did not raise major concerns regarding personalised risk warnings. However, several

respondents generally thought that standard risk warnings in combination with existing

marketing restrictions provided enough frictions in the journey.

Our response

PS22/10 sets out our response to the feedback on the CP22/2 proposals

for personalised risk warnings. This includes feedback from respondents

representing the cryptoasset sector.

We intend to proceed with applying the personalised risk warning to

DOFPs of cryptoassets. We also intend to apply the amendments made

in PS22/10. We continue to believe that this intervention is important

to help consumers understand the risks of an investment. Given the

evidence from behavioural testing which supported this as a key element

in helping consumers understand the risks of an investment, we continue

to believe that this intervention is needed to protect consumers.

Client categorisation

CP22/2 proposals and PS22/10amendments

3.36 Before a DOFP can be made in relation to an RMMI the consumer must be categorised

as a Restricted, High Net Worth, Self-certified Sophisticated or Certified Sophisticated

investor. This requires the investor to sign a declaration stating that they meet the

relevant criteria to be categorised as such.

3.37 In CP22/2 we proposed to implement an evidence component to the investor

declaration forms whereby consumers would be required to state why they met the

relevant criteria to be categorised. For example, stating their income to show they are

high net worth. This was informed by our behavioural testing which found that adding

this evidence component reduced rates of self-certification by 36%. We also proposed

to simplify the declaration using ‘plain English’ and to add a ‘none of the above’ option to

the declarations.

3.38 We proposed to apply the Restricted, High Net Worth and Certified Sophisticated

investor categories to promotions of cryptoassets. We did not propose to apply the

self-certified sophisticated investor category. The current criteria for self-certification

of sophistication are based on the investment relating to an unlisted security and include

31

criteria, such as being a member of a syndicate or business angel network, that are not

relevant for the purpose of demonstrating sophistication in relation to cryptoassets.

3.39 In PS22/10 we amended this proposal by changing the high net worth investor