*050205130*

Rev 1

Differential Effects on Student Demographic

Groups of Using ACT

®

College Readiness

Assessment Composite Score, ACT

Benchmarks, and High School Grade Point

Average for Predicting Long-Term College

Success through Degree Completion

Justine Radunzel

Julie Noble

August 2013

ACT Research

Report Series

2013 (5)

For additional copies:

ACT Research Report Series

P.O. Box 168

Iowa City, IA 52243-0168

© 2013 by ACT, Inc. All rights reserved.

Differential Effects on Student Demographic Groups of

Using ACT

®

College Readiness Assessment Composite

Score, ACT Benchmarks, and High School Grade Point

Average for Predicting Long-Term College Success through

Degree Completion

Justine Radunzel

Julie Noble

ii

Abstract

In this study, we evaluated the differential effects on racial/ethnic, family income, and

gender groups of using ACT

®

College Readiness Assessment Composite score and high school

grade point average (HSGPA) for predicting long-term college success. Outcomes included

annual progress towards a degree (based on cumulative credit-bearing hours earned), degree

completion, and cumulative grade point average at 150% of normal time to degree completion

(year 6 and year 3 for four- and two-year institutions, respectively). We also evaluated the utility

of the individual ACT College Readiness Benchmarks for predicting college success for each

demographic group.

Data for this study included over 190,000 ACT-tested students who enrolled in college as

first-time entering students in fall, 2000 through 2006. Over 100 total two- and four-year

institutions were represented. We used hierarchical logistic models to estimate institution-

specific probabilities of college success for all students and each demographic group based on

their ACT test scores and HSGPA. Accuracy and success rates for each student group were

calculated at total-group optimal selection values using the distributions of ACT Composite

score and HSGPA for each institution’s approximate applicant pool; these rates were then

summarized across institutions. Results were disaggregated by institution type.

Total-group predictions based on ACT Composite score generally overestimated the

long-term college success of underrepresented minority students (by, at most, 0.11 across

outcomes), lower-income students (by, at most, 0.07), and male students (by, at most, 0.13) and,

to a lesser extent, underestimated the success of White students (by, at most, 0.04), higher-

income students (by, at most, 0.07), and female students (by, at most, 0.10). The degree of

differential prediction by gender was less pronounced for the progress to degree and degree

iii

completion outcomes than for achieving levels of year 6/year 3 cumulative grade point average

(GPA). There was minimal differential prediction by family income for achieving levels of year

6/year 3 cumulative GPA. For racial/ethnic and family income groups, there was greater over-

and underprediction associated with using HSGPA than with using ACT Composite score. The

opposite was true for gender. Differential prediction by student demographic groups was also

observed at the ACT College Readiness Benchmark scores with the direction of the differential

prediction being consistent with that observed when ACT Composite score and/or HSGPA was

used.

For each student demographic group, test scores increased prediction accuracy over that

for HSGPA. Typical percentages of correct classifications at total-group optimal selection values

were generally higher for underrepresented minority and lower-income students than for White

and higher-income students; these percentages were similar for female and male students.

Contrary to prior claims made, results from this study suggest that minority and lower-

income students are not disadvantaged by using ACT Composite score or the ACT Benchmark

scores to predict long-term college success. This finding held across multiple college outcomes

at both two- and four-year institutions.

iv

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Edgar Sanchez and Richard Sawyer for their helpful comments and

suggestions on an earlier draft of this report.

v

Differential Effects on Student Demographic Groups of Using ACT

®

College Readiness

Assessment Composite Score, ACT Benchmarks, and High School Grade Point Average for

Predicting Long-Term College Success through Degree Completion

Introduction

To meet their admission goals while at the same time fulfilling their educational mission

of maintaining equal opportunity and diversity in student enrollments, four-year postsecondary

institutions often use multiple measures, including both academic and non-academic ones, in

determining the likelihood that a student will be successful in college (Clinedinst, Hurley, &

Hawkins, 2011). Academic measures often include grades in college preparatory courses,

strength of high school curriculum, standardized test scores (ACT or SAT), and high school

grade point average (HSGPA), because these measures have been found to identify accurately

students who are ready for college and to predict students’ eventual success in college. One

outcome that is commonly used by institutions for helping them make admission decisions is

first-year academic performance, as measured by first-year college grade point average (GPA).

But, due to the increased pressure that institutions are currently under to improve graduation

rates, institutions are also considering outcomes beyond the first year of college, including

evaluating the likelihood that applicants will complete a degree within six years (Higher

Education Research Institute, 2011; Saupe & Curs, 2008).

Two-year institutions are also feeling the pressure to increase graduation rates. And, even

though most two-year institutions currently practice open admissions, about one-fifth of them

use standardized test scores or HSGPA as part of their admission process (Breland, Maxey,

Gernand, Cumming, & Trapani, 2002). Moreover, due to the reduced resources available to them

some two-year institutions are having to prioritize access; restrict enrollment; eliminate lower-

level, developmental courses; and identify students who are likely to graduate or transfer to a

four-year institution (González, 2012). In addition, two-year institutions are being encouraged to

2

evaluate intermediate outcomes that measure progress towards degree completion to help

determine the reasons why so many students are not completing degrees (Moore, Shulock, &

Offenstein, 2009). Two-year institutions also use students’ test scores and HSGPAs to counsel

their applicants, including those who appear to be at risk of not succeeding in college (Habley,

Valiga, McClanahan, & Burkum, 2010).

In light of the push for increased accountability in higher education and the growing

concerns for open access remaining the norm at two-year institutions (González, 2012), we

recently evaluated the use of ACT Composite (ACTC) score and HSGPA for identifying

students who are likely to be successful in college beyond the first year for both four- and two-

year institutions (Radunzel & Noble, 2012a). In this study, we found that the typical percentages

of correct classifications at optimal ACTC scores for progressing towards and completing a

degree were moderately high (64% to 71% at four-year institutions and 65% to 77% at two-year

institutions). Across the college outcomes considered in the study, using ACTC score and

HSGPA in combination resulted in greater prediction accuracy, and was more effective for

identifying successful students among those expected to be successful, relative to using either

pre-enrollment achievement measure separately. Other researchers (Schmitt, Keeney, Oswald,

Pleskac, Billington, Sinha, & Zorzie, 2009) have also reported relatively high percentages of

correct classifications when predicting bachelor’s degree completion using SAT/ACT scores and

HSGPA jointly (for 63% of the students). In addition, it has been shown that college success

rates (including six-year bachelor’s degree completion rates) are substantially greater for

students with higher ACTC scores and HSGPAs than for those with lower scores or HSGPAs

(Radunzel & Noble, 2012b).

3

In our earlier study (Radunzel & Noble, 2012a), we also investigated the usefulness of

the ACT College Readiness Benchmarks in each of the subject areas for predicting long-term

college success. The ACT Benchmarks are the minimum ACT test scores required for students to

have a high probability of success in first-year, credit-bearing college courses–English

Composition, College Algebra, social sciences courses, and Biology (Allen & Sconing, 2005),

and provide an empirical definition of college readiness. The ACT Benchmarks were identified

as the typical scores across both two- and four-year institutions that maximized the accuracy for

predicting success (defined as earning a grade of B or higher) in the corresponding courses.

Meeting the ACT Benchmarks has also been shown to be positively associated with early and

long-term college success, such as enrolling and persisting in college and completing a degree

(Radunzel & Noble, 2012b; ACT, 2010a). Results from Radunzel and Noble (2012a) are

consistent with these other findings, and suggest that the ACT Benchmarks are effective at

identifying students who are ready for college and likely to succeed beyond the first year of

college.

As a reasonable extension to our earlier study (Radunzel & Noble, 2012a), in this study

we examine the effects of using ACTC score, HSGPA, and the ACT Benchmarks for predicting

college success among student demographic groups. When the relationships between college

outcomes, test scores, and HSGPAs differ among various population student groups, using a

total-group prediction equation (as would be the case in the college admissions process) may

result in systematic over- or underprediction for different student groups (i.e., differential

prediction).

Several studies have examined the differential effects on race/ethnicity and/or gender of

using standardized test scores (including ACTC score) and HSGPA to predict first-year college

4

GPA, thereby helping to ensure equity in the admissions process (Sanchez, 2013; Mattern,

Patterson, Shaw, Kobrin, & Barbuti, 2008; Noble, 2003; Young, 2001). Sanchez (2013) also

examined the differential effects on family income groups of estimating students’ chances of

earning a 2.5 or higher or a 3.0 or higher first-year college GPA based on their ACTC scores

and/or HSGPAs. Results from this latter study suggested that students’ chances of success

estimated from total-group models (all students irrespective of their demographic characteristics)

were overestimated for African American, Hispanic, lower-income, and male students, and were

slightly underestimated for White, higher-income, and female students. These findings held for

both pre-college measures, although HSGPA models generally resulted in greater over- and

underprediction of first-year success by racial/ethnic and family income groups than ACTC score

models did.

In terms of prediction accuracy, ACTC score and HSGPA were somewhat more accurate

predictors of first-year success for African American and Hispanic students than for White

students using the 3.0 or higher first-year GPA criterion. For the 2.5 or higher GPA criterion, the

percentages of correct classifications at optimal total-group selection values (values that

maximized prediction accuracy for the total group of students) were more comparable across

racial/ethnic groups. This latter finding also held for the family income and gender group

comparisons at both GPA criterion levels. Results from the study by Sanchez (2013) are

consistent with earlier studies (Mattern et al., 2008; Noble, 2003; Young, 2001), and suggest that

African American, Hispanic, and lower-income students are not disadvantaged in the college

admission process when ACTC score is used to predict first-year GPA.

Therefore, in this study, we extend the research by Sanchez (2013) to include college

outcomes beyond the first year through degree completion. In particular, in this study we

5

investigate the differential effects on student demographic groups of using one of the following

sets of pre-enrollment achievement measures to predict college success through degree

completion:

ACTC score,

HSGPA,

ACTC score and HSGPA, or

the ACT College Readiness Benchmarks.

Using total-group and group-specific predictions based on ACTC score and/or HSGPA, as well

as total-group ACTC score or HSGPA selection values that maximized prediction accuracy, we

compare the probabilities of success and percentages of correct classifications across student

demographic groups and predictor variables. The percentages of successful students for those at

or above the ACT Benchmark scores are also compared among student groups.

Clearly, a student’s likelihood of being successful in college is based on multiple factors,

including both cognitive and noncognitive characteristics (Allen & Robbins, 2010). ACT does

not advocate making college success predictions solely on the basis of a single measure, such as

a test score, or a single selection value. The use here of one or two predictors is a mathematical

simplification that can be generalized to multiple measures.

Data

Data for this study included approximately 194,000 ACT-tested students who enrolled in

college as first-time entering students in fall, 2000 through 2006. Over 100 institutions were

represented, including all public institutions from two state systems. Four-year institutions were

required to have at least six years of follow-up data available on their students. Two-year

institutions were required to have at least three years of follow-up data available on their

6

students. Multiple freshman cohorts of students from an institution were combined together in

the analyses. Cohort years spanned from 2000 to 2003 for 61 four-year study institutions and

from 2000 to 2006 for 43 two-year institutions. However, some institutions provided data for

some but not all of the outcomes. As a result, the number of institutions and enrolled students

with available data differed by college outcome. For additional information, see Radunzel and

Noble (2012a).

To examine the differential effects on student demographic groups of using ACTC score,

HSGPA, and ACT Benchmark scores to inform college admission decisions, we also included

over 505,000 students who sent their ACT scores to the same 104 institutions during the same

time frame but did not enroll there.

1

Nonenrolled students were identified from the 2000 to 2006

ACT records of all ACT-tested high school graduates nationally. These students requested that

their ACT test scores be sent to at least one of the 104 institutions included in this study during

the same time period as that for enrolled students. Nonenrolled students who sent scores to an

institution, plus those who actually enrolled in an institution, comprised the “applicant pool” for

that institution. The applicant pools for the institutions in this study were intended to

approximate actual applicant pools.

2

College outcomes included annual progress to degree (based on cumulative hours

earned), degree completion, and cumulative GPA at 150% of normal time to degree completion

(at the end of year 6 for four-year institutions and the end of year 3 for two-year institutions).

1

Four-year institutions make admission decisions about applicants. And, although most two-year institutions have

open admission policies, they are still concerned about the level of academic preparedness of their future incoming

students and often work with potential applicants through activities like high school outreach and bridge programs

(Barnett, Corrin, Nakanishi, Bork, Mitchell, Sepanik, … Clabaugh, 2012; Kerrigan & Slater, 2010). An example of a

high school outreach program includes an early assessment/intervention program where two-year institutions offer

high school juniors and seniors the opportunity to take college placement tests to evaluate their level of college

readiness and then encourage them to strengthen and refresh their skills if needed.

2

Students may send their ACT scores to any number of institutions, but actually apply to only a subset of them.

Conversely, some students may apply to some institutions without submitting official ACT score reports.

7

Analyses were done separately by institution type, where type was determined at the time of

initial enrollment. Progress to degree outcomes over time approximated bachelor’s degree

completion in about five years for students who started at four-year institutions and associate’s

degree completion in slightly over three years for students who started at two-year institutions;

approximations were based on using thresholds for cumulative hours earned that increased by 24

and 18 hours, respectively, each year. For degree completion, we evaluated earning a bachelor’s

degree within six years of initial enrollment at a four-year institution and earning an associate’s

degree within three years of initial enrollment at a two-year institution. For two-year institutions

from two state systems, we also evaluated associate’s degree completion or transfer to an in-state

four-year institution within three years of initially enrolling in college. Cumulative GPA was

evaluated at the end of year 6 for four-year institutions and at the end of year 3 for two-year

institutions (referred to in this report as the year 6/year 3 cumulative GPA) for enrolled students

and at the time of degree completion for students who graduated with a bachelor’s/associate’s

degree before the end of year 6/year 3. Year 6/year 3 cumulative GPA was evaluated at the

following levels: 3.00 or higher and 3.50 or higher.

3

The pre-enrollment measures used in this study included ACTC score, HSGPA, and the

ACT College Readiness Benchmarks. The ACT Composite score is the rounded arithmetic

average of the four subject area scores (English, Mathematics, Reading, and Science). Test

scores are reported on a scale of 1 to 36. HSGPA was based on student’s self-reported

coursework taken in up to 23 specific courses in English, mathematics, social studies, and

science and the self-reported grades earned in these courses. The ACT College Readiness

Benchmarks correspond to scores of 18, 22, 21, and 24 on the ACT English, Mathematics,

3

We are using higher criterion levels for year 6/year 3 cumulative GPA than Sanchez used in his study (2013) for

first-year college GPA because the typical average value across institutions was higher for the later outcome than for

the earlier one (3.1 for year 6 GPA and 2.8 for year 3 GPA vs. 2.7 for first-year GPA).

8

Reading, and Science tests, respectively (Allen & Sconing, 2005). Students who meet the ACT

Benchmark score have approximately a 50% chance of earning a B or better and approximately a

75% chance of earning a C or better in the corresponding college course or courses (ACT,

2010b).

Differential prediction of college outcomes was evaluated by race/ethnicity, family

income range, and gender. These demographic characteristics were reported by the students at

the time that they registered for the ACT test. For race/ethnicity, underrepresented minority

students (African American, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaskan Native students combined)

were compared to White students.

4

In this report, underrepresented minority students are referred

to as minority students. Family income was categorized as less than $30,000 (Low), $30,000 to

$60,000 (Mid), and more than $60,000 (High).

5

Table 1 provides the typical student

demographic percentages across postsecondary institutions.

4

The racial/ethnic minority group includes students who are generally underrepresented in postsecondary education.

Results for these racial/ethnic groups were combined to have sufficient sample sizes of underrepresented minority

students included in each institution’s applicant pool (10 or more). At the time of data collection, Native

Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander students (another racial/ethnic group often underrepresented in postsecondary

education) was not a separate racial/ethnic category. Therefore, students of this race/ethnicity could not be included

in the underrepresented minority group in this study. Results for other racial/ethnic groups such as Asian American

students are not reported due to smaller sample sizes.

5

The US median household income in 2003 was approximately $43,000 (US Census Bureau, 2003).

9

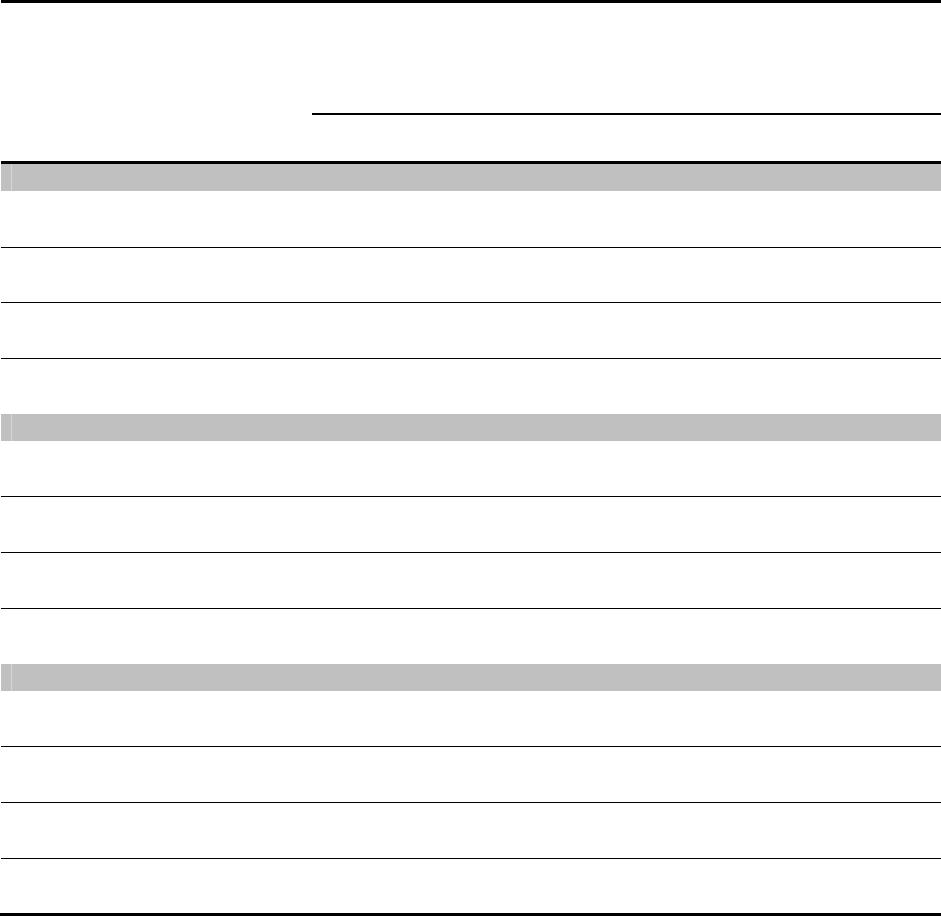

Table 1

Distributions of Student Demographic Percentages for Institutional Applicant Pools

by Type of Institution

Student demographic

characteristic

Two-year institutions Four-year institutions

Med Min Max Med Min Max

Race/ethnicity

Minority 21 3 51 17 3 93

White 73 46 95 78 4 95

Family income range

Low 39 18 54 25 14 62

Mid 43 34 55 43 28 53

High 17 11 39 29 10 50

Gender

Female 57 32 69 56 41 79

Male 42 33 64 43 21 56

Note. Median family income and gender percentages may not sum to 100 percent due to rounding. Median

racial/ethnic percentages do not sum to 100 percent due to other racial/ethnic student groups not included in

racial/ethnic comparisons, (e.g., Asian American students). Med = median; Min = minimum; Max = maximum.

Method

For each student demographic group and institution, we computed mean ACTC scores

and HSGPAs for enrolled students and the entire applicant pool. Mean cumulative GPAs and

college success rates were also calculated by institution and student demographic group for

enrolled students. Distributions of the means and rates associated with these variables were then

summarized across institutions and student demographic groups using minimum, median, and

maximum values.

We used hierarchical logistic models to estimate progress to degree, cumulative GPA,

and degree completion rates for enrolled students from the pre-enrollment measures and student

demographic characteristics (referred to in this report as group-specific regression models).

6

6

The hierarchical logistic regression models were estimated in HLM 6.08 (Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, & Congdon,

2004) using the Laplace approximation method. The pre-enrollment achievement measures were included in the

models in their original units (i.e., variables were not centered in the models).

10

Hierarchical models account for students clustered within institutions and allow the estimated

college success rates to vary across institutions. The pre-enrollment measures of ACTC score

and HSGPA were evaluated individually, as well as jointly, in the models. The individual ACT

subject area scores were each evaluated in separate models. The group-specific models not only

included the pre-enrollment measures and the individual student demographic characteristics but

also interactions between the pre-enrollment measures and student characteristics. We developed

separate models by year of enrollment for each relevant outcome and by institution type (two- vs.

four-year). The intercepts and the slopes of the main effects were included as random effects in

all models; interaction terms were included as fixed effects.

To examine the differential effects of ACTC score or HSGPA on long-term college

success by student demographic group, we used three different approaches. First, to evaluate

differential prediction by student demographic group across the entire ACTC score and HSGPA

scales, we compared typical probabilities of success estimated from the group-specific regression

models to those estimated from the total-group regression models. The total-group regression

models included the pre-enrollment achievement measures only, and did not include any of the

student demographic indicator(s) (described in detail in Radunzel and Noble (2012a)). For both

models, the probabilities of success were derived using the fixed effects parameter estimates

from the models. When the differences in the probability estimates between the total-group and

group-specific models at the same ACTC score or HSGPA are positive, then the total-group

model overpredicts the probabilities of success for the specific student group. When these

differences are negative, then the total-group model underpredicts success for the specific

student group.

11

Second, we also evaluated differential prediction by student demographic group at total-

group optimal selection values (values that were used to model the use of ACTC scores and

HSGPA for college admissions).

7

Optimal total-group selection values correspond to a 0.50

probability of success for a given model and maximize the estimated percentages of correct

selection decisions (Sawyer, 1996). Optimal selection values could be determined only for those

institutions whose total-group probability curves crossed 0.50 (that is, institutions with “viable”

models).

8

For the two-predictor models, multiple combinations of ACTC score and HSGPA

corresponding to a probability of success of 0.50 were identified. The total-group optimal

selection value(s) were used in this study for comparative purposes only (see Radunzel & Noble,

2012a).

9

In general, institutions rarely use strict selection values and often use multiple measures

in making their admission decisions (Clinedinst, Hurley, & Hawkins, 2011).

For each institution with a viable total-group model, we applied the institution-specific

total-group optimal selection value(s) to the corresponding group-specific probability

distributions for each institution, student demographic group, and predictor (or predictor

combination). We then summarized the distributions of these group-specific probabilities of

success across institutions using minimum, median, and maximum values. A typical (median)

7

Unlike the first approach, differential prediction is compared at ACTC score and/or HSGPA values that may differ

across institutions, since total-group optimal selection values for ACTC score and/or HSGPA (individually and

jointly) from the total-group regression models were identified for each institution (Radunzel & Noble, 2012a).

8

Outcomes that resulted in smaller numbers of institutions with viable total-group models included associate’s

degree completion and achieving higher levels of year 6/year 3 cumulative GPA when they were modeled as a

function of HSGPA. The reason for this is that for many institutions, students’ chances of success for these

outcomes were relatively low in general and never reached 50% across the entire HSGPA scale (see Appendix B

from Radunzel & Noble (2012a)).

9

The typical ACTC or HSGPA values that maximized prediction accuracy (that is, the values associated with at

least a 50% chance of being successful) were relatively high for degree completion from the same initial institution.

However, the optimal selection values also varied substantially across institutions (lower selection values were

generally seen for institutions with higher degree completion rates). In part, typical selection values were so high

because degree completion rates from the same institution were generally low, especially for two-year institutions.

Institutions are able to compensate for lower admissions standards with effective support programs and

interventions. For additional discussion on these matters, see pp. 45-47 from our earlier study (Radunzel & Noble,

2012a).

12

group-specific probability of success below 0.50 suggests that the total-group model tends to

overpredict success at the total-group optimal selection value(s) for the specific student group,

and a typical probability of success above 0.50 suggests underprediction for the student group.

We also used this approach to evaluate whether over- or underprediction for a particular student

group is consistently observed across all institutions. In the results section, we show that these

first two approaches lead to the same general differential prediction conclusions among the

student demographic groups.

Third, to evaluate the differences in prediction accuracy by student demographic group,

we estimated the following statistics for each predictor/predictor combination and outcome at

institution-specific total-group optimal selection value(s):

1. the percentage of correct classifications (accuracy rate (AR)),

2. the percentage of successful students among those expected to be successful (success

rate (SR)),

3. the increase in the percentage of correct classifications over expecting all applicants

to be successful (increase in accuracy rate (∆AR)), and

4. the percentage of students with values below the selection value(s) (100 minus this

percentage gives the percentage of students in the applicant pool at or above the

selection value(s)).

We calculated these statistics using the institution-specific parameter estimates from the

group-specific regression models and the corresponding group distributions of ACTC scores and

HSGPA for each institution’s applicant pool.

10

Correct classifications include students at or

above the total-group selection value(s) who would be successful and students below the value(s)

10

For each institution the estimated group-specific conditional probabilities of success for nonenrolled students were

assumed to be the same as those for enrolled students.

13

who would have not been successful. For a more complete description of the methodology used

(including the assumptions being made) to evaluate the usefulness of pre-enrollment measures in

the admissions process, see Sawyer (2010).

Distributions of these statistics were summarized across institutions and student groups

using minimum, median, and maximum values. In this paper, we present results across

institutions with viable models for each individual predictor/outcome combination. However,

results across institutions with viable models for both predictors were similar to those reported

here.

To study the differential effects on student demographic groups of using the ACT College

Readiness Benchmarks for predicting college success, we estimated group-specific probabilities of

success and SRs at the Benchmark scores for each institution. Increases in SRs (denoted as SRs)

were also estimated to evaluate the usefulness of the predictor variables for increasing SRs over

baseline success rates. For each student group, we summarized the distributions of probabilities of

success, SRs, and SRs across institutions using minimum, median, and maximum values. To

evaluate the differential prediction of using the ACT Benchmark scores by student group, we

compared typical total-group probabilities of success at the ACT Benchmark scores to

corresponding group-specific probabilities of success (positive differences suggest overprediction

and negative differences suggest underprediction).

11

In addition, we compared typical values of SRs

and SRs among student groups.

When students completed the ACT registration materials, some of them omitted

responses to high school coursework and grade items, as well as to the family income range item.

11

Since our focus was on evaluating the specific ACT Benchmark scores, we did not compare the typical

probabilities of success estimated from the total-group and group-specific models (using the fixed-effects parameter

estimates) across the entire scale of possible ACT subject area test scores. Such results at the ACT Benchmark

scores are expected to be comparable to those reported here based on the median value across institutions.

14

We used multiple imputation to estimate missing values; 12% and 17% of enrolled students and

11% and 15% of nonenrolled students had missing HSGPA and family income range,

respectively. Five data sets were imputed. We developed models for all five imputed data sets.

No practically significant differences in parameter estimates (including standard errors) were

found across the data sets. For all analyses involving HSGPA and family income range we report

the results based on the initial imputed data set.

Results

Differential Effects of ACTC Score and HSGPA for Predicting Long-Term College Success

In this section, we describe the differential effects on student demographic groups of

using ACTC score and HSGPA separately and jointly for predicting college success through

degree completion. We first present descriptive statistics for ACTC scores, HSGPAs, and college

outcomes over time disaggregated by race/ethnicity, family income, and gender. Next, we

present group-specific probability distributions for the various college outcomes as functions of

ACTC scores and HSGPAs, and compare these estimates to those derived from the total-group

models. Following this, we present for each student demographic group the median probabilities

of success, ARs, ∆ARs, and SRs at the total-group optimal ACTC and HSGPA selection values

to evaluate the accuracy of these pre-college measures for informing students’ chances of long-

term college success.

Descriptive statistics. Mean ACTC scores and HSGPAs were typically higher among

enrolled students than among students in the entire applicant pool at four-year institutions, but

means were comparable between enrolled students and the entire applicant pool at two-year

institutions. These findings held when examined by race/ethnicity, family income range, and

gender (Appendix A, Tables A-1 to A-6). For both the enrolled and applicant pool samples,

White students, higher-income students, and female students typically had higher mean ACTC

15

scores and HSGPA values than minority students, lower-income students, and male students,

respectively, at both two- and four-year institutions.

For most student demographic groups, the typical mean ACTC scores of enrolled

students in this study were lower than mean ACTC scores of first-year ACT-tested college

students nationally who enrolled in college in 2003 (Table A-7). This finding was observed at

both two- and four-year institutions, and is consistent with our previously reported results for the

total group of students (Radunzel & Noble, 2012a). For minority students and lower-income

students (the two exceptions to the general finding for most groups), typical ACTC means were

similar to or slightly higher than the corresponding national means. Differences in mean ACTC

scores between enrolled students nationally and the sample of enrolled students for this study

were larger for male students and higher-income students than for female students and middle-

income students, respectively.

12

College success rates, including degree completion rates, were typically higher for White

students than for minority students, and higher for female students than for male students (Tables

A-1 and A-2 for race/ethnicity and Tables A-5 and A-6 for gender). For example, the typical six-

year bachelor’s degree completion rate across four-year institutions was 14 percentage points

higher for White students than for minority students (44% vs. 30%) and nearly 10 percentage

points higher for female students than for male students (46% vs. 37%). As family income range

increased, typical college success rates also increased (Tables A-3 and A-4). For example, at

four-year institutions, we found that the typical six-year bachelor’s degree completion rate was

14 percentage points higher for higher-income students than for lower-income students (47% vs.

33%).

12

The result among income groups held for four-year institutions only.

16

The same general conclusions by student demographic group were seen at two-year

institutions, albeit with a few exceptions. First, the typical three-year degree completion or

transfer rate was the same for male and female students (23%; Table A-6). Second, the typical

three-year associate’s degree completion rate by income group was highest for middle-income

students, followed by higher-income students (Table A-4). Given that the three-year degree

completion or transfer rate was highest for higher-income students, a possible explanation for the

degree completion result (without transfer) is that higher-income students were more likely to

bypass earning an associate’s degree before transferring to a four-year institution.

Probabilities of success by student demographic group. In Appendix B we provide

figures of the estimated probabilities of completing a degree or achieving levels of year 6/year 3

cumulative GPA as a function of ACTC score or HSGPA by student demographic group

(Figures B-1 to B-18).

13

We estimated the probabilities in the figures using the fixed effects

parameter estimates from the group-specific hierarchical logistic models. Across college

outcomes and student demographic group, we found that as ACTC score or HSGPA increased,

the estimated probabilities of success at either a typical two- or four-year institution also

increased.

Race/ethnicity. For students with ACTC scores of 27 or below, probabilities of

completing a bachelor’s degree by year 6 for minority students were lower than those for White

students. In comparison, for students with ACTC scores of 28 or above, corresponding

probabilities for minority students were comparable to or higher than those for White students

(Figure B-1). We found a similar result for each of the other outcomes: however, the ACTC

score associated with the change in the direction of the racial/ethnic differences (from negative to

13

Probabilities of success are shown for degree completion and achieving levels of year 6/year 3 cumulative GPA;

they are not shown for the progress to degree outcomes. In addition, probabilities of college success are shown over

the range of observable ACTC scores and HSGPAs for each student demographic group.

17

positive) depended on the outcome (Figures B-1, B-3, and B-5). In contrast, probabilities of

college success predicted from HSGPA were consistently lower for minority students than for

White students (Figures B-2, B-4, and B-6). And, unlike the results for ACTC score, we found

that the racial/ethnic differences increased as HSGPA increased. These findings held for all

outcomes at both two- and four-year institutions.

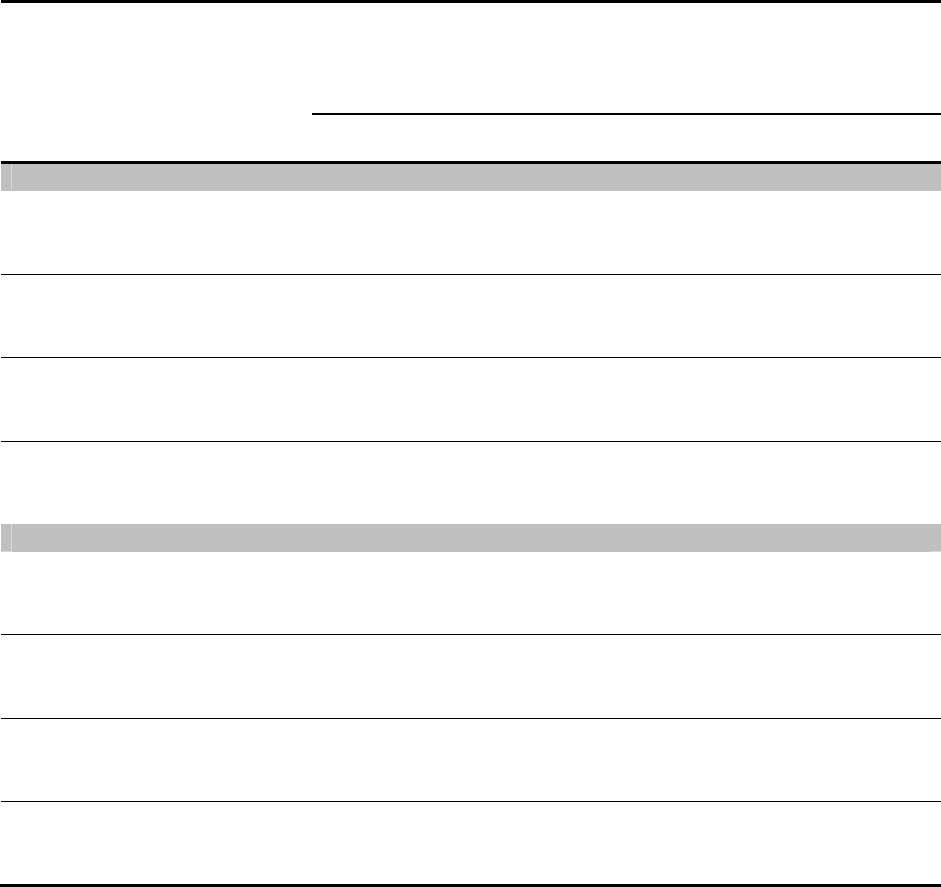

Total-group probabilities estimated from ACTC score or HSGPA individually were

generally similar to or slightly lower than the corresponding group-specific estimates for White

students: The total-group model slightly underpredicted probabilities of success for White

students relative to group-specific probabilities (by, at most, 0.04 across outcomes at both two-

and four-year institutions; Tables C-1 and C-2 in Appendix C). We illustrate this finding for

bachelor’s degree completion by year 6 by ACTC score in Figure 1 and by HSGPA in Figure 2.

14

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

10 15 20 25 30 35

ACTC score

Probability

White students Minority students Total group

Figure 1. Estimated probabilities of six-year bachelor’s degree completion by ACTC score and

race/ethnicity. ACTC = ACT Composite.

14

Probabilities estimated from the fixed effects parameter estimates from the total-group hierarchical logistic

models are provided for comparison.

18

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

2.0 2.5 3.0 3.5 4.0

HSGPA

Probability

White students Minority students Total group

Figure 2. Estimated probabilities of six-year bachelor’s degree completion by HSGPA and

race/ethnicity. HSGPA = high school grade point average.

In comparison, total-group models tended to overpredict probabilities of success for

minority students with ACTC scores at or below the 75th percentile for enrolled students (values

of 25 and 21 at four- and two-year institutions, respectively; Figure 1 and Tables C-1 and C-2).

At four-year institutions, as ACTC score increased beyond the 75

th

percentile, differences

between total-group probabilities and those for minority students tended to decrease, suggesting

little to no differential prediction of college success by race/ethnicity for students with higher

ACTC scores. This finding was also observed for achieving a year 3 cumulative GPA of 3.00 or

higher, or 3.50 or higher, at two-year institutions (Figure B-5). For the progress to degree and

degree completion outcomes at two-year institutions, results suggested slight underprediction for

the total-group model in estimating probabilities of success for minority students with higher

ACTC scores (at the 99th percentile of ACTC scores of 28 or above; by, at most, 0.06; Table C-

2).

19

Unlike the results for ACTC score, the amount of overprediction for minority students

increased as HSGPA increased (Figure 2, Tables C-1 and C-2). This finding held for most

outcomes at both two- and four-year institutions. We also found that for both predictors the

largest differences between the total-group and group-specific probabilities for minority students

generally occurred for the outcome of achieving levels of year 6/year 3 cumulative GPA.

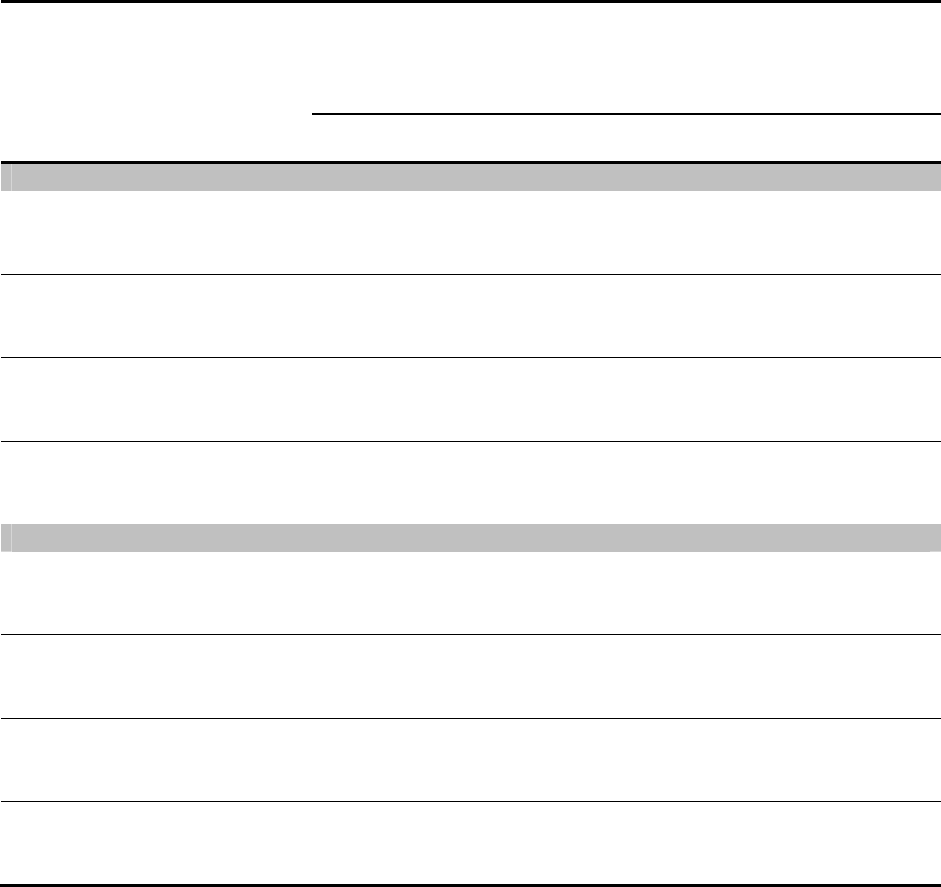

Family income. For most of the progress to degree and degree completion outcomes,

probabilities of success were greater for higher-income students than for lower-income

students.

15

This result held for both ACTC score and HSGPA (Figures B-7 and B-8 for degree

completion). Differences in probabilities of success between higher- and lower-income students

decreased as ACTC score increased (especially at two-year institutions), but the opposite was

true for HSGPA.

For both GPA levels at any given ACTC score, group-specific probabilities of achieving

levels of year 6/year 3 cumulative GPA were generally comparable across family income groups

(Figures B-9 and B-11). In contrast, income group differences in corresponding probabilities of

success associated with HSGPA tended to increase as HSGPA increased at both two- and four-

year institutions, especially for the 3.50 or higher criterion (Figures B-10 and B-12).

Total-group probabilities estimated from either ACTC score or HSGPA were generally

similar to or slightly lower than those for middle-income students. We illustrate this finding for

bachelor’s degree completion by year 6 across the ACTC score scale in Figure 3 and across the

HSGPA scale in Figure 4.

15

The exception to this finding was for associate’s degree completion by year 3 at two-year institutions. For students

with higher ACTC scores (at the 99th percentile of 28 or above), the chances of completing an associate’s degree by

year 3 were greater for lower-income students than for higher-income students.

20

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

10 15 20 25 30 35

ACTC score

Probability

High Mid Low Total group

Figure 3. Estimated probabilities of six-year bachelor’s degree completion by ACTC score and

family income. ACTC = ACT Composite.

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

2.0 2.5 3.0 3.5 4.0

HSGPA

Probability

High Mid Low Total group

Figure 4. Estimated probabilities of six-year bachelor’s degree completion by HSGPA and

family income. HSGPA = high school grade point average.

21

For the progress to degree and degree completion outcomes, total-group models tended to

slightly overpredict probabilities of success for lower-income students and underpredict those

for higher-income students (Figures 3 and 4; Tables C-3 and C-4).

16

We saw these results at both

types of institutions and for both predictors (by, at most, 0.07 for ACTC score and 0.08 for

HSGPA). For ACTC scores beyond the 75th percentiles, the amount of overprediction and

underprediction for lower- and higher-income students decreased as ACTC score increased, and

approached 0 for higher-income students. In comparison, differences in probabilities resulting

from the total-group and group-specific HSGPA models generally did not decrease for students

with higher HSGPAs. In some cases, the opposite occurred, especially at two-year institutions

(Tables C-3 and C-4).

For year 6/year 3 cumulative GPAs of 3.50 or higher, there was evidence of differential

prediction for lower- and higher-income students using the total-group HSGPA model, but only

for HSGPAs above 3.50 (over- and underprediction by, at most, 0.08 and 0.04, respectively;

Tables C-3 and C-4). A similar result held for the 3.00 or higher criterion at four-year institutions

(by, at most, 0.05 and 0.04, respectively). In contrast, there was minimal differential prediction

by family income group for the 3.00 or higher criterion at two-year institutions using HSGPA.

For both success levels and types of institutions, there was minimal differential prediction by

family income group using the total-group ACTC score model.

Gender. For all outcomes at two- and four-year institutions, probabilities of success

estimated from the ACTC group-specific models were higher for female students than for male

students (Figures B-13, B-15, and B-17). This finding also held for the HSGPA group-specific

models for achieving a 3.00 or higher or 3.50 or higher year 6/year 3 cumulative GPA (Figures

16

The exception to this result was for the total-group ACTC score model that estimated probabilities for completing

an associate’s degree by year 3. For this outcome, there was slight overprediction for higher-income students with

ACTC scores of 28 or above, and no evidence of overprediction for lower-income students.

22

B-16 and B-18). Gender differences in probabilities of achieving levels of year 6/year 3

cumulative GPA were generally greater when they were based on ACTC score than when they

were based on HSGPA. For the progress to degree and degree completion outcomes, male and

female students’ chances of success based on HSGPA were comparable (generally within 4

percentage points; Figure B-14 for degree completion).

For all outcomes at both types of institutions, total-group models based on ACTC score

generally overpredicted probabilities of success for male students and, to a lesser extent,

underpredicted those for female students (Figure 5; Tables C-5 and C-6). Across the ACTC score

scale, the maximum amount of over- and underprediction for male and female students was

greater for year 6/year 3 cumulative GPA than for the progress to degree and degree completion

outcomes (0.13 and 0.10 compared to 0.06 and 0.05, respectively).

17

For all outcomes at four-

year institutions and for year 3 cumulative GPA at two-year institutions, the absolute differences

in probabilities based on the total-group and group-specific models usually decreased as ACTC

score increased for ACTC scores at or above the 75th percentile (Tables C-5 and C-6).

17

The exception to the progress to degree and degree completion range was for associate’s degree completion by

year 3 where the maximum overprediction for male students was 0.10 and the maximum underprediction for female

students was 0.07.

23

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.0

10 15 20 25 30 35

ACTC score

Probability

Female Male Total group

Figure 5. Estimated probabilities of six-year bachelor’s degree completion by ACTC score and

gender. ACTC = ACT Composite.

For the progress to degree and degree completion outcomes, total-group probabilities

based on HSGPA were generally within 0.03 of the corresponding group-specific probabilities

for both male and female students (Figure 6 and Tables C-5 and C-6). For cumulative GPA there

was evidence of differential prediction by gender for the total-group HSGPA model

(overprediction for male students by, at most, 0.09 and underprediction for female students by, at

most, 0.06).

18

Moreover, as HSGPA increased the amount of overprediction for male students

also increased.

18

For cumulative GPA at two-year institutions, there was minimal underprediction of success for female students

(by, at most, 0.03).

24

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.0

2.0 2.5 3.0 3.5 4.0

HSGPA

Probability

Female Male Total group

Figure 6. Estimated probabilities of six-year bachelor’s degree completion by HSGPA and

gender. HSGPA = high school grade point average.

Accuracy and success rates for ACTC score and HSGPA by student demographic

group. In this section, we summarize median probabilities of success, ARs, ∆ARs, and SRs by

student demographic group across institutions with viable models based on ACTC score and/or

HSGPA. These results are evaluated using the institution-specific total-group optimal selection

values (where the total-group probability of success was closest to 0.50) and the group-specific

probabilities of success (Appendix D, Tables D-1 to D-4 for race/ethnicity, Tables D-5 to D-8 for

family income, and Tables D-9 to D-12 for gender).

In our earlier study (Radunzel & Noble, 2012a) for the total group of students, we found

that median ARs, ∆ARs, and SRs for the joint ACTC score and HSGPA models were generally

higher than those based on the single-predictor models. A common finding in this study was that

this result was seen for each student group, regardless of the outcome.

25

Race/ethnicity. For all three ACTC score and HSGPA model combinations, the typical

probabilities of success at total-group optimal selection values generally exceeded 0.50 for White

students and were less than 0.50 for minority students.

19

This finding held for most outcomes,

20

and was in general agreement with our previously reported differential prediction results by

race/ethnicity.

21

In particular, we found that there was a general tendency for minority students to

have lower probabilities of success than White students with the same ACTC scores/HSGPAs.

22

However, the direction and magnitude of the differences in the probabilities of success from 0.50

varied across institutions (Tables D-1 to D-4). For example, probabilities of bachelor’s degree

completion by year 6 at the institution-specific total-group ACTC score selection values ranged

from 0.44 to 0.62 for White students and from 0.31 to 0.58 for minority students across

institutions (Table D-1). In general, probabilities of success for minority students were generally

lower than those for White students with the same HSGPA.

23

These differences were smaller

when based on ACTC score. The total-group model that included both ACTC score and HSGPA

as predictors generally resulted in the smallest amount of underprediction for White students

(probabilities were closer to 0.50). For minority students, the joint model also resulted in less

overprediction than the HSGPA model did.

19

The total-group selection values were those ACTC scores and HSGPAs that corresponded to a probability of

success of 0.50 (the point where the ARs were maximized for the total group of students).

20

For outcomes with higher total-group optimal ACTC selection values, we found that there was a tendency for

slight underprediction for minority students (see results for associate’s degree completion with or without transfer by

year 3, Appendix D, Table D-2).

21

Those that were based on comparing total-group and group-specific probabilities estimated using fixed-effects

parameter estimates from the hierarchical logistic models.

22

The typical amount of overprediction for minority students and underprediction for White students at total-group

selection values were comparable to those estimated from the fixed-effects models at the same ACTC score or

HSGPA; these estimates were not exactly the same due to differences in the approaches used to combine

information across institutions.

23

For the later progress to degree outcomes and year 6/year 3 college GPA, we found underprediction for minority

students at the total-group optimal HSGPA selection values for all four-year institutions and for most two-year

institutions included in this study (see minimum and maximum values in Tables D-1 to D-4).

26

For all three predictor models, median ARs across institutions for most of the long-term

outcomes were higher for minority students than for White students.

24

Typical increases in

correct classifications (∆ARs) were also substantially higher for minority students than for White

students (e.g., 46% vs. 20%, respectively, for bachelor’s degree completion by year 6 based on

ACTC score). In contrast, typical SRs evaluated at or above the total-group optimal selection

values were generally higher for White students than for minority students (e.g., 56% and 52%

for bachelor’s degree completion based on ACTC score). However, for all outcomes at both two-

and four-year institutions, racial/ethnic differences in median SRs were smaller for the ACTC

score or joint models than for the HSGPA models (e.g., 4, 5, and 10 percentage points,

respectively, for bachelor’s degree completion by year 6). In general, higher percentages of

minority students than White students had ACTC scores and HSGPAs below the institution-

specific total-group optimal selection values. Thus, substantially fewer minority students than

White students had ACTC scores or HSGPAs at or above the total-group optimal values.

Family income. For the progress to degree and degree completion outcomes, the typical

probabilities of success by family income group at the total-group optimal selection values were

generally less than 0.50 for lower-income students (overprediction), near 0.50 for middle-income

students, and above 0.50 for higher-income students (underprediction).

25

This finding generally

held for all three predictor models for most, if not all institutions (Tables D-5 and D-6), but the

magnitude of over- and underprediction for lower- and higher-income students varied across

institutions. For example, probabilities of bachelor’s degree completion by year 6 estimated from

24

These outcomes included outcomes beyond year 2 for four-year institutions and beyond year 1 at two-year

institutions.

25

The exception to this finding was for associate’s degree completion by year 3 at two-year institutions, where

median probabilities of success were comparable across the three income groups.

27

the ACTC score and HSGPA joint model ranged from 0.40 to 0.49 across institutions for lower-

income students and from 0.53 to 0.58 for higher-income students.

For two-year institutions, typical probabilities of a 3.00 or higher, or 3.50 or higher, year

3 cumulative GPA by income group at total-group optimal selection values were comparable,

irrespective of the predictor used (Table D-8). For the ACTC score and joint models, this result

also held at both GPA criterion levels for year 6 cumulative GPA at four-year institutions (Table

D-7).

26

Across outcomes using the total-group optimal selection values, we found that HSGPA

tended to overpredict success for lower-income students more than ACTC score, while the extent

of underprediction for higher-income students was more similar for the two predictors.

For the later progress to degree and degree completion outcomes, median ARs across

institutions were typically higher for lower-income students than for middle- and higher-income

students irrespective of predictor (Tables D-5 and D-6). Correspondingly, for most of these

comparisons, median ARs generally decreased as income level increased. We found a similar

result for achieving a year 6/year 3 cumulative GPA of 3.50 or higher (84%, 79%, and 77% for

lower-, middle-, and higher-income students at four-year institutions, Table D-7). For the earlier

progress to degree outcomes and achieving a year 6/year 3 cumulative GPA of 3.00 or higher,

median ARs were more comparable among the income groups. Across outcomes for all three

predictor models, median ∆ARs were substantially greater for lower-income students than for

higher-income students, and generally greater for middle-income students than for higher-

income students (Tables D-5 through D-8).

On the other hand, typical SRs for students at or above the total-group optimal selection

values generally increased as income level increased (e.g., from 49% to 60% for bachelor’s

26

There was evidence of overprediction for lower-income students and underprediction for higher-income students

at the total-group optimal HSGPA selection values for this outcome at four-year institutions.

28

degree completion and from 50% to 58% for associate’s degree completion or transfer to a four-

year institution based on ACTC score model).

27

For most outcomes at two-year institutions,

income group differences in median SRs were generally smaller when ACTC score was used

alone or jointly with HSGPA than when HSGPA was used alone (e.g., 8, 11, and 15 percentage

points, respectively, for associate’s degree completion or transfer to a four-year institution by

year 3; Table D-6). We saw this result for both of the year 6 cumulative GPA outcomes at four-

year institutions (Table D-7). For the progress to degree and degree completion outcomes at

four-year institutions, income group differences in typical SRs were more comparable for all

three predictor models (Table D-5). For each outcome, it was generally the case that higher

percentages of lower-income students than of higher-income students had ACTC scores or

HSGPAs below the institution-specific total-group optimal selection values (e.g., typical

percentages of students below ACTC score selection values for bachelor’s degree completion

decreased from 90% to 78% as income level increased; Table D-5).

Gender. For most of the predictor models and outcomes, the typical probabilities of

success at the total-group optimal selection values were generally above 0.50 for female students

(underprediction) and below 0.50 for male students (overprediction).

28

Probabilities of success at

the total-group optimal selection values varied across institutions (e.g., from 0.50 to 0.59 for

female students and from 0.41 to 0.52 for male students using ACTC score to predict bachelor’s

degree completion by year 6; Table D-9). In general, using ACTC score alone tended to result in

27

Exceptions to this finding were for completing an associate’s degree by year 3 and achieving levels of year 3

cumulative GPA. The result for associate’s degree completion by year 3 based on ACTC score model might be

explained by higher-income students with higher ACTC scores being more likely to transfer to a four-year

institution before earning an associate’s degree (as evidenced by larger differences in the probabilities between the

two associate’s degree outcomes for higher-income students than corresponding differences for lower-income

students; Figure B-7).

28

For the progress to degree and degree completion outcomes at both types of institutions, typical probabilities of

success at the total-group optimal selection values based on the HSGPA or joint models were near 0.50 for both

female and male students. This result suggested minimal differential prediction by gender at the total-group optimal

selection values for these outcomes and predictors.

29

slightly greater differential prediction by gender at the total-group optimal selection values than

when HSGPA was used alone or in combination with ACTC score (Tables D-9 to D-12).

29

For all three predictor models and most of the outcomes considered in this study, typical

ARs at total-group optimal selection values were similar for female and male students.

30

Gender

differences in median increases in correct classifications (∆ARs) were larger at four-year

institutions than at two-year institutions, with median ∆ARs consistently higher for male students

than for female students. Conversely, typical SRs associated with total-group optimal selection

values were consistently higher for female students than for male students (e.g., 61% and 51%

for bachelor’s degree completion using ACTC score). Gender differences in median SRs were

smaller when HSGPA was used alone or jointly with ACTC score than when ACTC score was

used alone (e.g., 5, 5, and 10 percentage points, respectively, for bachelor’s degree completion

by year 6). For each outcome, typical percentages of students scoring below the institution-

specific total-group optimal ACTC score selection values were similar for female and male

students. In contrast, for HSGPA, corresponding median percentages were higher for male

students than for female students.

Differential Effects on Student Demographic Groups of Using ACT College Readiness

Benchmarks for Predicting Long-Term College Success

In this section, we evaluate the differential effects of the ACT College Readiness

Benchmarks for predicting college success through degree completion among student

demographic groups. We first present descriptive statistics on ACT Benchmark attainment for

enrolled students, as well as for the entire applicant pool disaggregated by race/ethnicity, family

29

For year 6/year 3 cumulative GPA, there was evidence of overprediction for male students and underprediction

for female students at the total-group optimal selection values for HSGPA (by, at most, 0.09 for the typical

probabilities of success; Tables D-11 and D-12).

30

The exception was for achieving a year 6/year 3 cumulative GPA of 3.50 or higher (Tables D-11 and D-12);

median ARs were slightly higher for male students than for female students.

30

income, and gender. We then evaluate the typical probabilities of success, SRs, and ∆SRs

associated with the ACT College Readiness Benchmark scores among student demographic

groups.

Descriptive statistics. At four-year institutions, the typical percentages of students

meeting the ACT Benchmarks were higher among enrolled students than among students in the

applicant pool. In contrast, the typical Benchmark attainment percentages for students at two-

year institutions were comparable for the enrolled and applicant pool samples, and were lower

than those for students at four-year institutions. These findings were consistently seen when

disaggregated by race/ethnicity, family income range, and gender (Appendix E, Tables E-1 to E-

3).

At both two- and four-year institutions, median percentages of students meeting the ACT

Benchmarks were substantially higher for White students than for minority students and for

higher-income students than for lower-income students (Tables E-1 and E-2). Typical

Benchmark attainment percentages were slightly higher for female students than for male

students in English and reading, but were slightly lower in mathematics and science (Table E-3).

Probabilities of success and success rates for ACT College Readiness Benchmarks

by student demographic group. For each student demographic group, we calculated median

probabilities of success, SRs, and ∆SRs associated with ACT Benchmark scores across all

institutions with available outcome data. For these analyses, we evaluated year 6/year 3

cumulative GPA for the 3.00 or higher criterion level only.

31

A common finding that we observed across student demographic groups was that the

typical probabilities of success, SRs, and ∆SRs were generally higher for the ACT Mathematics

31

For this criterion level, the ACT Benchmark scores are more similar to the typical total-group optimal ACTC

score selection values.

31

and Science Benchmarks than for the ACT English and Reading Benchmarks. This finding is

consistent with our previously reported result for the total group of students (Radunzel & Noble,

2012a).

Race/ethnicity. The probabilities of success at the Benchmark scores for both White and

minority students varied substantially across institutions. For example, probabilities of bachelor’s

degree completion by year 6 estimated at the ACT English Benchmark score ranged from 0.12 to

0.77 for White students and from 0.10 to 0.64 for minority students. Median probabilities of

success associated with the ACT College Readiness Benchmarks were higher for White students

than for minority students (Appendix F, Tables F-1 and F-2). However, racial/ethnic differences

in the median probabilities of success at the Benchmark scores were smaller than those in the

observed median proportions of success, where prior achievement was not considered (see

Tables A-1 and A-2). For example, for bachelor’s degree completion by year 6, racial/ethnic

differences in probabilities ranged from 0.05 to 0.09 across Benchmark subject areas (e.g., 0.34

vs. 0.28 for the English Benchmark), compared to an observed difference in proportions

(irrespective of Benchmark attainment) between White and minority students of 0.14 (0.44 vs.

0.30). This result generally held across outcomes at both two- and four-year institutions.

For White students, median probabilities of success at the Benchmark scores were similar

to those for the total group of students (generally differed by only 0.01 to 0.02).

32

For minority

students, probabilities of college success at the Benchmarks were typically lower than those for

32

For achieving a year 6 cumulative GPA of 3.00 or higher, the typical group-specific probabilities of success at the

ACT English and Reading Benchmark for White students were greater than those estimated from the total-group

model by 0.04 (that is, the total-group model slightly underpredicted the success of White students for this outcome;

Table F-1).

32

the total group of students.

33

Thus, the total-group models tended to overpredict college success

for minority students scoring at the Benchmarks. It was generally the case that there was less

overprediction associated with the ACT Mathematics Benchmark than for the other

Benchmarks.

34

For example, for bachelor’s degree completion by year 6, differences between the

typical probability estimates for the total group and those for minority students were 0.07, 0.04,

0.07, and 0.05 at the ACT English, Mathematics, Reading, and Science Benchmarks,

respectively.

Typical SRs associated with the ACT Benchmark scores were slightly higher for White

students than for minority students. This finding held for all outcomes at both two- and four-year

institutions and for each of the four Benchmarks (Tables F-1 and F-2). For example, for

bachelor’s degree completion by year 6, the median SR associated with the ACT Mathematics

Benchmark was 53% for White students, compared to 48% for minority students. Racial/ethnic

differences in median SRs were generally smaller for the ACT Mathematics Benchmark than for

the other Benchmarks (e.g., 10, 5, 9, and 7 percentage points for the English, Mathematics,

Reading, and Science Benchmarks, respectively, for bachelor’s degree completion by year 6).

35

In contrast, ∆SRs associated with the Benchmark scores were typically higher for minority

students than for White students.

Family income. Median probabilities of success associated with the ACT Benchmarks

were greater for higher-income students than for middle- and lower-income students; lower-

income students tended to have the lowest estimated probabilities of success (Appendix F,

33

Group-specific probabilities of success for minority students were typically lower than total-group probabilities at

the Benchmark scores by 0.02 to 0.09 for four-year institutions and by 0.02 to 0.07 for two-year institutions. The

one exception to this result was for achieving a year 6 cumulative GPA of 3.00 or higher at four-year institutions,

where the total-group model typically overpredicted success for minority students by 0.11 to 0.16.

34

Differences in the amount of overprediction for minority students between Benchmarks were relatively small

(ranged from 0.02 to 0.07 for four-year institutions and from 0.01 to 0.04 for two-year institutions).

35

Exceptions to this finding were for the two degree completion outcomes at two-year institutions where

racial/ethnic differences in median SRs were more comparable across the Benchmarks (Table F-2).

33

Tables F-3 and F-4).

36

However, differences in median probabilities of success across income

groups at the Benchmark scores were somewhat smaller than differences in the observed median

proportions of success reported previously (Tables A-3 and A-4), when prior achievement was

not taken into accounted (by, at most, 0.08). This finding held for most outcomes at both types of

institutions.

Median probabilities of success for middle-income students at the Benchmark scores

were similar to corresponding median total-group probabilities (higher by, at most, 0.03).

Probabilities at the Benchmarks for lower-income students were typically lower than the

corresponding total-group probabilities (by 0.02 to 0.09 at four-year institutions and by 0.01 to

0.06 at two-year institutions).

37

Conversely, typical probabilities for higher-income students were

greater than the corresponding median total-group probabilities (by 0.01 to 0.06 at four-year

institutions and by 0.03 to 0.07 at two-year institutions).

38

These results taken together suggest

that across the outcomes, total-group models for predicting students’ chances of college success

at the ACT Benchmark scores tended to slightly overpredict probabilities of success for lower-

income students and underpredict success for higher-income students.

Typical SRs associated with the ACT Benchmark scores generally increased as family

income range increased (e.g., from 38% to 50% for bachelor’s degree completion by year 6 using

the ACT English Benchmark). This finding held for most outcomes at two- and four-year

36

Exceptions to this finding were for completing an associate’s degree by year 3 and achieving a year 3 cumulative

GPA of 3.00 or higher. For these outcomes, median probabilities of success were comparable across the family

income groups (Table F-4).

37

The one exception to this finding was for achieving a year 3 cumulative GPA of 3.00 or higher at two-year

institutions. For this outcome, group-specific probabilities for lower-income students were similar to the total-group

probabilities (Table F-4).

38

Exceptions to this finding were for completing an associate’s degree by year 3 and achieving a year 3 cumulative

GPA of 3.00 or higher. For these outcomes, group-specific probabilities at the Benchmark scores for higher-income

students were more similar to the corresponding total-group probabilities (Table F-4).

34

institutions and across all four Benchmarks (Tables F-3 and F-4).

39

Income differences in median

SRs were generally smaller for the ACT Mathematics Benchmark than for the other Benchmarks

(e.g., 12, 9, 13, and 11 percentage points for the English, Mathematics, Reading, and Science

Benchmarks, respectively, for bachelor’s degree completion by year 6). Typical ∆SRs associated

with the Benchmark scores were higher for lower-income students than for higher-income

students.

40

Gender. Median probabilities of success associated with the ACT Benchmarks were

generally higher for female students than for male students (Appendix F, Tables F-5 and F-6).

Gender differences in median probabilities of success were slightly larger for the ACT

Mathematics and Science Benchmarks than for the English and Reading Benchmarks.

For the progress to degree and degree completion outcomes, median probabilities of

success at the Benchmark scores were slightly higher than those for the total group of students

for female students (underprediction), and lower for male students (overprediction) (generally

only by 0.01 to 0.08). For each of the outcome and Benchmark combinations, the

underprediction for female students generally corresponded to a somewhat similar degree of

overprediction for male students. For achieving a year 6/year 3 cumulative GPA of 3.00 or

higher, there tended to be more differential prediction by gender associated with the Benchmark

scores than was seen for the other outcomes (absolute differences in median probabilities ranged

from 0.04 to 0.14 for this outcome). In addition, the degree of overprediction for male students

was larger than the degree of underprediction for female students. These findings were in general

39

Exceptions to this finding included completing an associate’s degree by year 3 and achieving a year 3 cumulative

GPA of 3.00 or higher. For these outcomes, median SRs were more comparable across the three family income

groups (Table F-4).

40

Differences in typical ∆SRs between lower- and higher-income students were generally larger for the ACT

Mathematics and Science Benchmarks than for the English and Reading Benchmarks.

35

agreement with the ones noted earlier for the probabilities of success evaluated at the total-group

optimal ACTC score selection values.

Typical SRs associated with the ACT Benchmark scores were higher for female students

than for male students. This finding held for all outcomes at two- and four-year institutions and

across all four Benchmarks (Tables F-5 and F-6). Gender differences in median SRs were

slightly larger for the ACT Mathematics and Science Benchmarks than for the English and

Reading Benchmarks (e.g., 12 vs. 7 to 8 percentage points, respectively, for bachelor’s degree

completion by year 6). In addition, typical ∆SRs associated with the ACT Benchmarks were

slightly higher for female students than for male students in mathematics and science,

41

and were

similar for female and male students in English and reading.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the differential effects on racial/ethnic, family income, and

gender groups of using ACTC scores and HSGPAs for identifying possible applicants who are

likely to progress towards and complete a degree. This study is unique in that it is the first study

to evaluate differential prediction and differences in prediction accuracy by student groups for

multiple measures of college success beyond the first year at both two- and four-year institutions.

For the most part, results from this study are in general agreement with those from prior studies